Abstract

Valorization of environmental waste into sustainable energy and value-added products offers a strategic pathway for advancing circular economic development and resource sustainability. In this study, waste cooking oil was converted into biodiesel using biogenically generated CaO, prepared thermally at 900 °C. The reaction process was modeled and optimized with a Taguchi orthogonal array L9(34), considering four factors at three levels to yield nine experimental conditions. The model reliability was statistically validated through analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 95% confidence level (p < 0.05), achieving a high determination coefficient (R2) of 0.9965. The maximum biodiesel yield of 91.08% was obtained under the optimal conditions of the methanol to oil ratio of 15:1, a catalyst loading of 4.5 wt%, a reaction time of 90 min, a temperature of 65 °C, and a constant stirring speed of 650 rpm. The fuel property analysis confirmed compliance with international biodiesel and diesel standards). Economic evaluation of the process showed that integrating waste cooking oil with reusable seashell-derived catalysts enabled the production of high-quality biodiesel at R23.20 (~USD 1.39)/L, highlighting a sustainable and cost-competitive alternative to conventional feedstock. The study contributes to advancing waste-to-energy technologies and supports the transition towards a circular and sustainable energy future.

1. Introduction

The escalating impacts of climate change, manifesting as rising global temperatures, prolonged droughts, melting polar ice, and increasing sea levels, are closely linked to the continued dependence on fossil fuels. The combustion of these fuels remains the principal source of greenhouse gas emissions, yet they still account for more than 80% of global energy consumption [1]. This imbalance highlights a critical environmental and energy challenge and the urgent need to transition toward cleaner, renewable, and more sustainable fuel alternatives. Biodiesel presents a viable solution to this challenge. As a renewable, biodegradable, and environmentally benign fuel, biodiesel significantly reduces emissions of carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and particulate matter compared to petroleum diesel [2]. Moreover, its production from organic feedstocks (including waste-derived oils) promotes waste valorization, improves resource circularity, and contributes to energy diversification. Together, these attributes position biodiesel as a promising pathway for mitigating environmental degradation while supporting a more sustainable energy future. The sustainable feedstock for biodiesel includes the utilization of waste and non-edible oil resources. The extensive use of edible oil resources (such as palm, soybean, rapeseed, sunflower, etc.) presents serious economic and sustainability challenges, such as competition between food and fuel applications. Waste cooking oil (WCO) has appeared as an attractive alternative feedstock to edible oils due to its availability and lower economic value. Approximately 15 million tons of waste vegetable oil are generated globally every year [3], and improper disposal of it presents considerable environmental risks owing to its chemical properties and high organic content. WCO, when released into drainage systems, can cause obstructions, leading to sewer overflows and expensive maintenance [4,5]. Valorization of WCO as sustainable biodiesel feedstock is, therefore, reducing environmental pollution and promoting sustainable waste management practices and the circular economy.

Biodiesel is produced by reacting oils with alcohol using either esterification or transesterification, depending on the feedstock’s free fatty acid (FFA) content. Esterification is an acid-catalyzed reaction in which FFAs react with alcohol to form esters and water. It is mainly applied to high-FFA oils to avoid soap formation, which can reduce biodiesel yield. In this pathway, the acid catalyst protonates the FFA carbonyl, enabling nucleophilic attack by alcohol and subsequent water elimination [6]. Transesterification, in contrast, involves the reaction of triglycerides with alcohol in the presence of a base catalyst. The base forms methoxide, which attacks the triglyceride carbonyl, producing fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) and intermediates. These intermediates, including diglycerides and monoglycerides, undergo sequential conversion to additional FAME and finally glycerol. Esterification, therefore, converts FFAs to biodiesel, whereas transesterification converts triglycerides. The former produces water as a by-product, while the latter generates glycerol. Each pathway has distinct catalytic requirements and operational sensitivities based on feedstock composition. However, recent studies have demonstrated that bifunctional catalysts can simultaneously catalyze esterification and transesterification, enabling the direct one-step conversion of high-FFA oils and eliminating the need for separate pre-treatment stages [7]. Industrially, basic catalysts (e.g., KOH, NaOH, NaOCH3) are frequently used in the transesterification process due to their fast reaction rate. However, the attendant challenges attached to their usage, such as extensive recovery and purification steps of the reaction products, are the major concerns. It is reported that over 120 L of contaminated and alkaline wastewater is generated per 100 L of biodiesel produced [8]. Thus, this incurs an additional cost of treatment before discharge, which significantly contributes to the economic and environmental costs of biodiesel production.

Heterogeneous basic catalysts are mostly preferred in recent research, most especially the green-based heterogeneous catalysts (GHCs) based on their simplified catalyst separation and purification steps [9]. Additionally, GHCs have several advantages, including renewability, higher surface area, thermal stability, eco-friendliness, and a simple process of synthesis. Biogenically derived calcium oxide (CaO) is one of the potential GHCs reported for biodiesel production [10,11]. Its high activity in transesterification is attributed to its high basicity and porous structure. CaO can easily be obtained from waste bio-resources, such as animal bones and shells [12,13]. Waste seashells are another potential source of CaO. They are primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and are substantial waste streams from the seafood processing sector, with millions of tons discarded globally every year [14,15]. Conventional disposal strategies, such as landfilling and ocean dumping, cause odor aggravation, pathogen proliferation, and area contamination, leading to environmental and economic issues [16]. According to Venugopal [17], landfills’ contribution to climate change is about 10 times larger than that of other waste disposal options. Converting waste seashells into calcium oxide (CaO)-based heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel generation is an environmentally friendly valorization approach that adheres to circular economy concepts [8]. Seashell-derived catalysts offer a feasible and sustainable alternative for biodiesel generation, with apparent advantages in waste valorization, resource conservation, and possible CO2 emission reduction.

To improve the effectiveness of the transesterification method, the process factors that affect the yield should be modeled and optimized to determine the ideal conditions for high yield(s). Although modeling is beneficial in establishing mathematical equations that deal appropriately with the dependent variables for a chemical process, the optimization process, on the other hand, assists in making an effective blend of the process input variables, leading to maximization or minimization of the objective function by resolving the mathematical model equation using regression analysis [18]. The response surface methodology-Taguchi design (RSM-TD) package has been reported as an efficient and adaptive statistical modeling tool for this purpose. It is flexible with the smallest number of experiments and has effectively been used in designing and analyzing the transesterification experiments. The Taguchi design method was applied to models and statistically analyzed the transesterification experiment of palm oil methyl ester using a CaO catalyst under optimal experimental conditions of C: 10 wt%, M: 9:1, T: 65 °C, and t: 180 min to achieve a 95.44% yield [19]. It was also applied in optimizing the transesterification of rubber seed oil methyl ester using iron-doped carbon in a study conducted by Dhawane et al. [20], in which 97.5% biodiesel yield was achieved at the peak condition of C: 4.5 wt%, M: 9:1, T: 60 °C, and t: 60 min. A Taguchi L9 design was applied to the optimized esterification process of Hura crepitans seed oil using an acid catalyst, and 94.81% ester conversion was achieved under a condition of C: 10 wt%, M: 9:1, T: 90 °C, and t: 60 min [21]. Again, it was used in our previous study to achieve 96.06% yield in biodiesel production from Mafura kernel oil utilizing a green catalyst derived from fruit peels under the best conditions of C: 4.5 wt%, M: 15:1, T: 65 °C, and t: 90 min [22].

Thus, this study seeks to establish a sustainable biodiesel synthesis method by employing waste resources, notably waste cooking oil and a heterogeneous CaO catalyst derived from waste seashells. The biogenic CaO catalyst synthesized was characterized to assess its suitability for biodiesel production. The influence of the key reaction parameters, including catalyst loading, the methanol to oil molar ratio, reaction duration, and temperature, was optimized and statistically analyzed using response surface methodology-Taguchi design (RSM-TD) to generate conditions conducive for effective biodiesel conversion. Furthermore, the fuel characteristics of the generated biodiesel were evaluated according to international standards, and an economic analysis was performed to ascertain the cost-effectiveness of the proposed process. Overall, by integrating catalyst development, process optimization, product quality assessment, and economic analysis, this work intends to advance a scalable and environmentally liable waste-to-energy strategy that aligns with circular economic principles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Waste cooking oil (WCO) was collected from the tuck shops at the Mangosuthu University of Technology (MUT) campus. The seashells used comprised oyster, mussel, clam, scallop, and cockle shells, and they were collected from South Beach in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. All the analytical-grade chemicals and reagents, such as MeOH (98%), ethanol (99%), KOH (99%), KI (99%), cyclo-hexane, phenolphthalein (99%), HCl (99%), and wijs solution, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and supplied by United Scientific SA cc, Congella, Durban, South Africa.

2.2. Catalyst Preparation and Calcination

Calcium oxide catalysts derived from biogenic shells, including seashells, and their characterization have been previously reported in the literature [8,11,19,23]. In this study, a simplified preparation method was adapted following a previous study [22]. The seashells were thoroughly cleaned by double washing with tap water and subsequently dried in an oven at 115 °C for 48 h. The dried shells were pulverized using a Junke and Kunkel hammer and ground into fine powder using a ball milling machine. The seashell powder was sieved to pass through 150 mesh screens and then subjected to calcination in a muffle furnace at 900 °C for 3 h. This thermal treatment facilitated the decomposition of CaCO3, abundantly present in seashells, into CaO with the release of CO2 gas. The CaO Np catalyst obtained was further characterized using SEM, EDX, and XRD analyses to determine surface morphology, elemental composition, and crystalline phase structure.

2.3. WCO Preparation and Characterization

The obtained WCO was filtered to remove the remaining food particles left in the oil after frying. The filtered oil was then subjected to physicochemical property characterization following the AOCS method and is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The physicochemical properties of WCO used.

2.4. Experimental Design by Taguchi

The Taguchi design approach was employed in this study with an orthogonal array to analyze the effect of the process parameters on the yield. The four reaction parameters, considering their range and levels, are presented in Table 2. Thus, they were used to generate experimental conditions and to achieve the desired results. The triplication of each condition helps to validate and minimize errors. The outstanding characteristics of the TD method are the ability to compute the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on the experimental results obtained. The signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio is a critical statistical measure used to assess a system’s stability and performance under varying conditions. It combines the response mean and variability, allowing for the selection of ideal factor levels that improve resilience and reduce susceptibility to external disturbance [24]. It can be defined as the ratio of the mean performance characteristics (WCOME yield) to its standard deviation. This can be expressed using the larger-the-better formula given in (Equation (1)), since the yield maximization is the major focus. Thus, this can also be clarified by assessing parameters used for statistical analysis using analysis of variance (ANOVA) [24]. The influence of parameters can be evaluated via the calculation of each contribution factor. The calculation is based on the sum of squares of the individual parameters and the overall sum of squares of the model. The contribution factor for each parameter can be determined using Equation (3). The optimization process was performed by selecting all parameters in the range of investigations and setting the methyl ester yield for maximization. The optimal condition established was a catalyst loading of 4.5 wt%, a reaction time of 90 min, a methanol-to-oil ratio of 15:1, and a temperature of 65 °C. The predicted yield was 91.85 wt %. This condition was validated in triplicate and compared with the predicted responses.

where n is the number of replicates and yi is the individual measurement (yield). Thus, this can be reduced to Equation (2) if the measurement is based on each run.

where SSf is the sum of squares of the individual factor, and SST is the total sum of squares.

Table 2.

Selected parameters and their levels for L9 design.

2.5. Transesterification Process with CaO Np

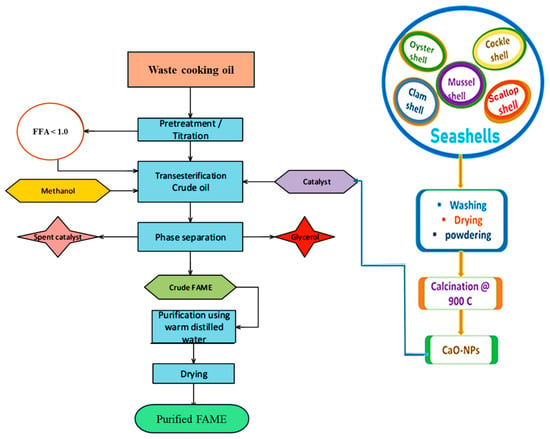

Waste cooking oils usually require simultaneous esterification and transesterification (TES) due to their high free fatty acid levels. However, the FFA content of the feedstock used in this study was measured at 0.95%. This value is below the generally accepted threshold of 2% FFA [6,7]. Consequently, the reaction proceeded via transesterification using a base catalyst, without the need for an acid-catalyzed esterification pre-treatment step. The experiment was conducted in a 500 mL round-bottom flask reactor. The waste cooking oil was first heated to 100 °C to remove traces of moisture and then cooled to 60 °C. The required quantity of methanol and CaO-Nps catalyst was added based on the amount of oil and stirred vigorously at 650 rpm. The reaction proceeded at a desired time allotted to each experiment in the TD matrix generated using Table 2. The mixture was cooled to room temperature at the end of the experiment and was separated into three phases made up of the biodiesel, glycerol, and catalyst. The biodiesel fraction was decanted and further washed with warm distilled water at 50 °C to get rid of the residuals, and then the drying process was completed using anhydrous sodium sulphate to obtain clean biodiesel [25]. The process of biodiesel production is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic flow diagram of the biodiesel synthesis from the WCO using the CS-CaO Nps catalyst.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the CaO Nps Catalyst

3.1.1. SEM Analysis

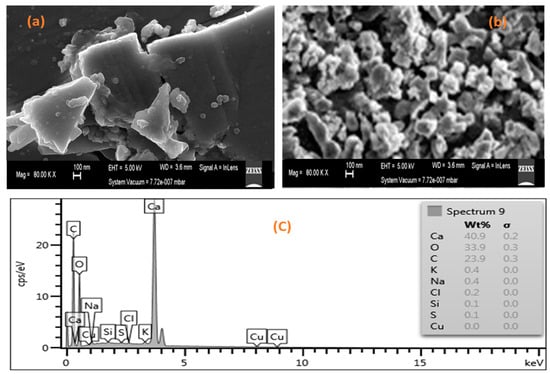

The surface morphology and elemental composition of the seashell-derived catalysts were characterized using SEM (Auriga, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with an EDX detector. As illustrated in Figure 2a,b, the raw seashells displayed dense, irregular structures, while the calcined samples showed agglomerated particles with reduced size and enhanced porosity due to thermal decomposition during calcination [8]. These morphological changes are consistent with earlier reports and are crucial as they allow the increased of surface area and porosity, therefore providing more active sites for transesterification reactions [26,27].

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a) raw seashells, (b) calcined seashells, and (c) EDX of the calcined seashells.

3.1.2. EDX

The EDX analysis of the synthesized seashell-derived catalyst depicted in Figure 2c indicated a high peak and composition of Ca (40.9), confirming the presence of CaO. However, relatively high carbon content (23.9 wt%) was also detected alongside traces of other elements, such as K (0.4), Na (0.4), Cl (0.2), Si (0.1), and S (0.1), which synergistically enhanced catalytic activity and stability of the catalyst. This high carbon is attributed to the natural biogenic composition of seashells. Seashells typically contain organic residues and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) of about 95–99% [28,29]. During calcination, complete decomposition of CaCO3 to CaO may not occur, particularly in materials with dense microstructures. As a result, traces of carbon-containing species remain in the final material. This interpretation is consistent with the XRD results (Figure 3), where CaO is confirmed as the predominant crystalline phase, accompanied by minor peaks corresponding to CaCO3. These findings support the fact that the catalyst is primarily composed of CaO with small residual carbonate phases. Despite this, the catalyst demonstrated high efficiency in converting waste cooking oil to biodiesel under optimized reaction conditions. During the transesterification reaction, methanol interacts with CaO to generate a methoxide nucleophile, which subsequently attacks the carbonyl carbon of triglycerides, facilitating their conversion to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) [29]. As the reaction progresses, glycerol is produced as a by-product, which can interact with CaO to form calcium glyceroxide. This layer may gradually accumulate on the catalyst surface, potentially affecting its reusability. Furthermore, hydroxyl groups present on CaO can react with methanol to form structural methoxide anions (CH3O−), which provide additional basic active sites, thereby enhancing the transesterification process [29].

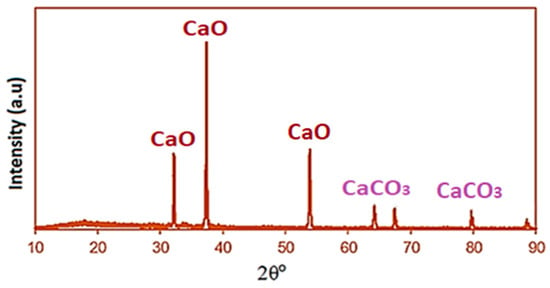

Figure 3.

The XRD pattern of calcined seashells at 900 °C.

3.1.3. XRD Analysis

The crystalline phase composition of the catalyst was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a D-8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany), employing Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 30 mA, equipped with a PSD detector. Measurements were conducted at ambient temperature. XRD analysis was used to identify the crystalline phases and mineral compositions of the calcined seashells. The diffraction patterns (Figure 3), revealed that the major peaks at approximately 2θ = 32.2°, 37.4°, and 53.8° are assigned to CaO (JCPDS No. 37-1497). Minor peaks at 2θ = 64.1°, 67.4°, and 80.1° correspond to CaCO3 (calcite) (JCPDS No. 05-0586), confirming the presence of residual carbonate species. These observations verify that CaO is the dominant phase in the calcined seashell catalyst, with traces of undecomposed CaCO3 remaining due to the biogenic origin and partial decarbonation during calcination. The crystallite size (D) of the CaO nanoparticles was estimated using the Scherrer equation as follows:

where κ is the shape factor (0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.5406 Å), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peak (in radians), and θ is the Bragg angle. Based on the most intense peak at 2θ ≈ 37.4°, the average crystallite size of the calcined seashell-derived CaO was calculated to be approximately 35 nm, indicating the nanoscale nature of the catalyst. The duration of the calcination process has less impact on the catalyst structure compared to the temperature. According to Singh and Verma [30], the high temperature of calcination induces a fast drop of Ca2+ and succeeding homogeneous nucleation of calcium nuclei, resulting in CaO formation in the form of nanoparticles.

3.2. Reusability

Calcium oxide (CaO) is a highly basic and relatively non-toxic catalyst; however, its strong hygroscopic nature poses significant challenges. Upon exposure to air or liquid, CaO readily absorbs moisture and carbon dioxide, leading to the formation of calcium hydroxide (Ca (OH)2) and calcium carbonates. These transformations poison the active sites of the catalyst and result in rapid deactivation [29]. Several studies have also reported the leaching of calcium ions during the transesterification process due to the partial solubility of CaO in methanol, which necessitates additional purification steps for biodiesel and glycerol produced, thereby increasing production costs [8,23]. In this study, the reusability of CaO was evaluated over four cycles under optimized reaction conditions. After each transesterification cycle, the catalyst was recovered, washed with methanol, dried, and reused. The biodiesel yields obtained were 91.08, 86.42, 73.23, and 55.87% for the first, second, third, and fourth cycles, respectively. The decline in yield may be attributed to the progressive surface fouling, pore blockage by organic residues, and partial re-carbonation of CaO to CaCO3 during reaction exposure [2,29]. Although catalyst regeneration was not performed in this study, previous studies have shown that recalcination at 700–900 °C can restore CaO activity, primarily by decomposing CaCO3 and removing surface contaminants [30,31]. However, repeated high-temperature regeneration may lead to sintering, reduced surface area, and gradual loss of catalytic efficiency over multiple cycles, which are the limitations of CaO-based catalysts. Additionally, the reactivation process incurs additional energy costs, limiting the overall economic feasibility of CaO as a catalyst. To address these limitations, modified CaO catalysts have been reported, which exhibit improved structural stability, reduced leaching, and consistent catalytic activity across multiple cycles. Such modifications have demonstrated enhanced yields and constant reaction rates, making them more suitable for practical biodiesel production [32,33].

3.3. Transesterification Process Modeling by the Taguchi Approach

The nine experimental conditions generated by the Taguchi design orthogonal array for WCOME synthesis were carried out in the laboratory, and the obtained results are presented in Table 3. The results were analyzed with appropriate statistical measures. The predicted WCOME yield(s) together with the calculated S/N ratio for each experiment are also presented in Table 3. To generate the main input parameters having an influence on the WCOME yield, the regression analysis was performed at a 95% confidence level. The coefficient in terms of the coded factors to predict the yield is given in Equation (4). The influence of the MeOH/oil ratio was observed to be insignificant on the yield; therefore, it was excluded from the model equation.

where Y is the WCOME yield (wt%), Q, Z, and L are the process input parameters of CaO loading, reaction temperature, and time, respectively, and [1] and [2] represent the first and second levels for WCOME prediction.

Y= 84.51 − 2.96Q [1] + 0.98Q [2] − 3.83Z [1] + 2.37Z [2] − 1.52L [1] + 2.98L [2]

Table 3.

Factor levels with the actual and predicted yields.

3.4. Evaluation of the Developed Model Quality

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) from the statistical point of view is useful in determining the significant process parameters. While the Fischer test (F-value) determines the significance of the selected model and individual parameter affecting the response, the p-value gives an idea about the probability of obtaining an F-value of this extent [24].

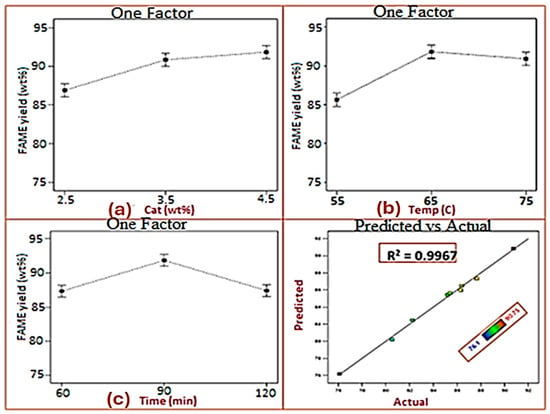

The sum of squares of the model and individual parameters was used to assess the influence of each parameter on the biodiesel yield by evaluating their contributing factors. Table 4 shows the ANOVA results, including the F- and p-values for the model. The high F-value of 101.64 suggests strong statistical significance, with a 0.98% chance that the result could be attributable to random variation or noise. Three of the four input parameters studied had a substantial impact on the WCOME yield. Reaction temperature (Z) had the strongest impact, with an F-value of 138.58 and a p-value of 0.0072, followed by CaO loading (Q) with an F-value of 84.28 and a p-value of 0.0117, and reaction time (L) with an F-value of 82.06 and a p-value of 0.0120. Thus, Z (reaction temperature), Q (CaO loading), and L (reaction time) are highlighted as significant model terms. This is further supported by the individual parameter contribution analysis in Table 3, which revealed that reaction temperature (Z: 45.30%) has the strongest influence, followed by CaO loading (Q: 27.55%) and reaction time (L: 26.83%).

Table 4.

Significance level of the model and process input factors.

The methanol-to-waste cooking oil (MeOH/WCO) ratio showed a negligible impact on WCOME yield within the examined range. The proposed model was subsequently investigated using various statistical parameters, as indicated in Table 5. The coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9967) indicates that the independent variables can explain 99.67% of the variability in WCOME yield, and only 0.33% could not be explained by the model. This demonstrates an outstanding fit between the model and the experimental data [34,35]. To prevent overestimation of R2, the adjusted R2 was calculated and found to be 0.9869, which validates the model’s reliability. An R2 value above 80% generally indicates a good fit of the model [18]. Furthermore, the predicted R2 of 0.9338, with the difference between the predicted and adjusted R2 of less than 0.2, indicates the model’s reliability for prediction. The closeness of R2, adjusted R2, and predicted R2 values confirm the model’s accuracy in predicting the response. The lower standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV) in the experimental results further support the model’s significance (Table 4). The coefficient of variance of less than 10% implies that there is accuracy and consistency in the way the experiments were conducted [18].

Table 5.

Fit statistics.

3.5. Effect of Input Parameters on WCOME Yield

The effect of catalyst loading on WCOME yield was investigated at three different concentrations: 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5 wt% relative to oil weight. As seen in Figure 4a, the FAME yield increased steadily with increasing catalyst dosage. At 2.5 wt%, the yield was 86%, increasing to 90% at 3.5 wt%. A further increase in catalyst loading to 4.5 wt% resulted in a slight but significant improvement of 1.8%, reaching the maximum yield of >90 wt%. This trend indicates that higher catalyst loading enhances the availability of active basic sites, thereby accelerating the transesterification reaction. However, the marginal improvement observed beyond 3.5 wt% suggests that an optimum loading threshold is approached, beyond which an additional catalyst contributes little to overall conversion efficiency. A similar observation was reported in research using CaO/KBr catalysts with an optimal biodiesel yield (~82%) at around 4 wt% loading, while higher amounts led to reduced yield. This may likely be due to soap formation and increased mixture viscosity impeding reactant interaction [36]. The effect of reaction temperature on WCOME yield was investigated at three different temperatures: 55, 65, and 75 °C. The highest yield of 91.08% was achieved at 65 °C. As shown in Figure 4b, the increasing temperature from 55 to 65 °C increased the yield by 5.8%. This improvement is mostly due to the acceleration of chemical reaction kinetics as temperature increases, resulting in more frequent and effective collisions between reactant molecules. At 65 °C, adequate heat is provided to improve miscibility and mass transfer between methanol and oil, increasing transesterification efficiency while minimizing methanol evaporative losses. However, above 65 °C, the yield decreased by roughly 1%. This reduction can be attributed to the close vicinity of methanol’s boiling point (64.7 °C), where evaporative losses diminish the effective methanol-to-oil ratio in the reaction mixture, decreasing the conversion efficiency. Furthermore, higher temperatures above the optimum can stimulate side reactions, like triglyceride saponification, which competes with transesterification and reduces biodiesel output. Previous investigations have shown similar tendencies. Salim et al. [37] reported that higher reaction temperatures reduce oil viscosity, resulting in faster reaction rates and shorter overall reaction times. Nonetheless, excessive heating over the ideal threshold increases methanol evaporation and enables soap production, both of which contribute to yield reduction. Thus, maintaining the reaction temperature at an appropriate range of around 65 °C is critical for increasing biodiesel yield, ensuring efficient reaction kinetics, and avoiding methanol losses and unwanted side reactions. The effect of reaction time on WCOME yield is shown in Figure 4c. Three reaction durations of 60, 90, and 120 min were investigated. The FAME yield increased from 87.4% at 60 min to a maximum of 91.08% at 90 min. However, extending the reaction to 120 min resulted in a decline in yield. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 4c and is consistent with patterns reported in similar biodiesel studies [23,26]. Adequate reaction time is essential for ensuring proper mixing of reactants and complete conversion. However, excessively long reaction periods can lead to adverse effects, such as methanol evaporation, oil drying, increased viscosity, and possible equilibrium reversal, all of which reduce the effective transesterification rate [37].

Figure 4.

(a–c): Effect of process variables on WCOME yield: (a) A plot of WCOME yield vs. CaO catalyst, (b) A plot of WCOME yield vs. Temperature, (c) a plot of WCOME yield vs. Time.

3.6. Process Optimization and Model Validation

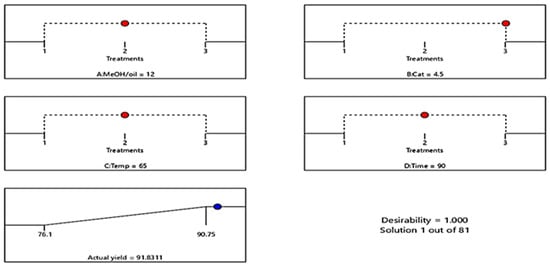

The optimization process was performed by solving the regression equation presented in Equation (4). The estimated ideal values obtained are a MeOH/WCO ratio of 12:1, a CaO amount of 4.5 wt%, a reaction temperature of 65 °C, and a time of 90 min, with a predicted yield of 90 wt% (Figure 5). This condition was further validated with three sets of confirmatory experiments to obtain an actual value of 91.08 wt%. Table 6 shows a brief literature survey of the transesterification optimum conditions of biodiesel obtained from various oils using a biogenic CaO-based heterogeneous catalyst. Thus, the conditions in this study are relatively mild while still yielding a high biodiesel conversion of 91.08%. Several prior experiments necessitated either elevated catalyst concentrations (5–10 wt%) [19,23], prolonged reaction durations (120–180 min), or temperatures beyond the boiling point of methanol to attain equivalent or marginally higher yields. Although some reported yields exceeding 95%, these often relied on severe operational conditions or more intensive preparation steps, which potentially reduce their overall sustainability and scalability. In contrast, the current technique achieves an effective balance between catalytic activity and operational efficiency, demonstrating better catalytic performance of seashell-derived CaO under moderate conditions. A potential limitation is the observed gradual decline in catalyst reusability, implying that further optimization of regeneration techniques may be required to meet the long-term stability reported in some other studies. Nonetheless, the present findings demonstrate the competitiveness and practical advantages of the developed process relative to existing biogenic CaO-based biodiesel production routes.

Figure 5.

A plot of process parameter optimization and yield prediction.

Table 6.

A review of the activity of biogenic-based CaO in transesterification experiments.

3.7. Fuel Qualities of WCOME

The fuel characteristics of the produced WCOME were analyzed with all measurements performed using the ASTM standard method and compared to those of conventional diesel and previous studies (Table 7). Kinematic viscosity is a significant fuel property that affects atomization and combustion performance. The viscosity of biodiesel is higher than that of conventional diesel due to its higher molecular and chemical structure [35]. The ASTM standard specification for biodiesel viscosity ranges from 1.9 mm2/s to 6 mm2/s. The viscosity of WCOME (3.82 mm2/s) was found within the acceptable limit and is consistent with the previous studies. This suggests that the produced WCOME can offer sufficient fuel atomization during injection. Density is another important fuel characteristic that directly influences the engine function, fuel atomization, and the thermal efficiency of the engine [35]. The produced biodiesel density was 0.88 g/cm3, which was within the ASTM recommended range of 0.82–0.90 g/cm3 and higher than the conventional diesel limit of 0.85 g/cm3. The calorific value (CV) indicates the energy output of the fuel combustion. A higher CV is advantageous for CI engines. Due to the high oxygen content of biodiesel (10%), its CV is lower than that of conventional diesel. The CV of diesel is 45.5 MJ/kg, while the produced biodiesel was 38.20 MJ/kg, and the previous study reported a value of 36.30 MJ/kg. The cetane number (CN) indicates the ignition delay of the fuel. A higher CN value shows the capacity of the fuel to quickly self-ignite, while a lower CN value indicates higher exhaust emissions from the engine, increased deposits, and incomplete combustion [44]. Biodiesel has a higher CN and better combustion efficiency than conventional diesel due to its high oxygen content [45]. The CN of the produced biodiesel was 55, which is higher than the ASTM minimum recommended standard of 47 and the conventional diesel of 48. The flash point, which is an important criterion for determining fuel safety during storage and transportation, was much greater in WCOME than in diesel. This increased flash point improves handling safety by minimizing fire dangers, making WCOME better suited for storage and transportation. The cold flow qualities validated WCOME’s applicability in colder climates, showing its potential for year-round use. Furthermore, the acid value of the produced biodiesel was determined to be less than 0.5 mg KOH/g, which is well within the ASTM standards. A low acid value (0.38 mg KOH/g) below the maximum recommended limit of 0.50 reduces the risk of corrosion in engine metallic components, resulting in longer engine life and less maintenance [44]. Overall, the fuel properties of WCOME show that it meets worldwide biodiesel quality criteria and may be used as a reliable and secure replacement for conventional diesel in compression ignition engines.

Table 7.

WCOME properties in comparison with ASTM, diesel standards, and previous studies.

3.8. Cost Evaluation of the Catalyst and Produced Biodiesel

The cost of feedstock and catalysts substantially influences the economic viability of biodiesel production, accounting for more than 70–80% of the total production costs. In this assessment, waste cooking oil (WCO) and seashells were considered to have zero procurement cost because they are commonly classified as waste resources with no direct market value. Waste cooking oil (WCO) was utilized as the primary feedstock, with seashells serving as the precursor for the calcium oxide (CaO) catalyst. The principal costs associated with seashell-derived catalysts were cleaning, drying, and calcination. However, in real-world applications, additional costs may arise from collection, transportation, storage, and preliminary handling. These logistical expenses can vary, depending on the scale of operation and the efficiency of the supply chain, and, in some cases, may contribute 10–30% of the overall operating cost of biodiesel production [46]. Although these factors may moderately increase the total production cost, WCO and seashell-derived CaO remain economically favorable alternatives compared to edible oils and commercially sourced catalysts. Recognizing these potential costs offers a more pragmatic view of the economic viability of biodiesel synthesis from waste-derived feedstocks and highlights the necessity of developing effective collection networks for sustainable large-scale adoption. The detailed breakdown of the associated processing costs of catalysts and biodiesel production of the current study is presented in Table 8. The cost of catalyst production in this study was R19.60/kg (~USD 1.17/kg), which is much lower compared to the USD 46.34/kg and USD 5.7/kg costs of catalysts prepared from waste flamboyant pods and waste banana material reported by [47] and [48], respectively. The overall cost of biodiesel per liter in this study was calculated as R23.20/L (~USD 1.39/L).

Table 8.

Cost assessment of the biodiesel production from the WCO and seashell CaO catalyst.

Economic assessment of the biodiesel production of this study demonstrates strong feasibility within a circular economic framework. Waste cooking oil (WCO) represents the most cost-effective and sustainable feedstock, contributing significantly to the reduction in overall production costs compared to edible oils. Seashell-derived calcium oxide (CaO) catalysts, when calcined at high temperature ranges of 900–1100 °C, consistently achieve biodiesel yields above 90% (Table 6). Their preparation from abundantly available waste shells ensures negligible catalyst costs while reducing environmental burdens associated with waste disposal. Modified versions of seashell catalysts (e.g., CaO doped with ZnO, TiO2, or KOH) further enhance catalytic activity, though they slightly increase material costs [22,29]. According to [46], feedstock is the primary driver of biodiesel production costs, with waste-derived catalysts playing a minor role. In this investigation, seashell-based catalysts lowered overall output to R23.20/L (1.39 USD/L). The reusability of seashell-based catalysts further increases their economic viability, making waste cooking oil and seashell-derived catalysts a long-term, cost-effective solution for large-scale biodiesel synthesis. Collectively, these findings highlight that combining waste cooking oil with seashell-derived catalysts not only ensures high biodiesel yield and fuel quality but also offers a sustainable and economically competitive pathway for large-scale biodiesel production.

4. Scaling up Production and Commercial Viability

Scaling up the biodiesel production process from laboratory to industrial levels is both promising and challenging. The promising aspect lies in the abundance of raw materials, waste cooking oil, and seashell waste, which are low-cost, readily available, and environmentally beneficial to valorize, thus enhancing economic feasibility. However, several challenges must be addressed to ensure successful commercialization. These include establishing reliable supply chains for raw materials, designing energy-efficient calcination methods to produce seashell-derived CaO catalysts at scale, and developing reactors capable of maintaining optimal reaction conditions across large volumes. Additionally, maintaining consistent product quality to meet stringent international standards requires advanced purification and quality control systems. The high energy demand for calcination and other process operations poses economic and environmental considerations, emphasizing the necessity for integrating renewable energy solutions. Furthermore, long-term catalyst durability, process automation, and waste management are critical technological requirements. Economically, while low-cost feedstocks and high yields favor competitiveness, substantial capital investment, energy costs, and market dynamics must be managed effectively. Overall, with strategic planning, technological innovation, and supportive policies, scaling this process holds significant potential to produce sustainable biodiesel cost-effectively, contributing to circular economy goals and reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

5. Overview of Future Studies for Life Cycle Assessment

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the biodiesel production process highlights its environmental sustainability and overall environmental impact. The study demonstrates that using waste cooking oil and seashell-derived CaO catalysts significantly reduces environmental burdens, such as greenhouse gas emissions and resource depletion, compared to conventional biodiesel production methods. It is possible that a detailed LCA study could lead to the indication that the process might significantly benefit from the valorization of waste materials, which minimizes waste disposal issues and promotes resource conservation within a circular economy framework. Moreover, energy consumption during catalyst preparation and transesterification was found to be manageable, especially when integrated with renewable energy sources. The assessment underscores that, despite some energy inputs necessary for calcination and processing, the environmental benefits of reduced emissions, low raw material costs, and waste valorization outweigh the drawbacks, making this biodiesel production pathway a sustainable alternative to conventional fuels. As this study focuses mainly on optimization, an LCA study using the results from this study can be undertaken in detail in future studies to generate more knowledge about the possibility of producing biodiesel in a sustainable way using waste cooking oil and seashells as a synthesized catalyst. It will bring more understanding regarding sustainability and will contribute more to scalability. Consequently, more knowledge related to economic considerations, environmental sustainability, and technological improvements will be gained.

6. Overview Analysis of Environmental and Social Impacts

The environmental and social impacts of using waste cooking oil and seashell-derived CaO catalysts for biodiesel production extend beyond environmental benefits, fostering broader sustainability. This approach offers significant social advantages by promoting local community engagement and supporting waste management initiatives. Using locally sourced waste materials reduces environmental pollution caused by improper disposal, such as landfilling and ocean dumping, which can adversely affect community health and ecosystems. Additionally, incorporating waste valorization strategies creates employment opportunities in collection, processing, and catalyst preparation, thereby stimulating local economies and encouraging community participation in sustainable practices. Aligning this process with circular economic principles emphasizes resource efficiency, waste minimization, and the regeneration of materials, which collectively enhance community resilience and foster a sustainable energy transition. Overall, this approach promotes social equity by turning waste into valuable energy sources while supporting environmentally responsible development within local contexts.

7. Conclusions

Biodiesel was produced from two waste streams consisting of waste cooking and seashells, generating a CaO catalyst, and it was investigated through the transesterification process using methanol. The waste shells containing CaCO3 were converted to CaO after calcination at 900 °C. The XRD and EDS characterization of the catalyst confirmed the presence of CaO as the dominant compound, and some traces of K (0.4%), Na (0.4%), Cl (0.2%), Si (0.1%), and S (0.1%) were also detected, which are suggested to contribute to the catalytic activity enhancement during the conversion process. The optimum conditions established by L9 (34) in achieving a high biodiesel yield of 91.08% were a molar oil to MeOH ratio of 1:12, a CaO loading of 4.5 wt%, a reaction duration of 90 min, and a temperature of 65 °C. The contribution of each parameter determined by ANOVA revealed the impact of MeOH/oil as negligible, while that of temperature was the strongest. From experimental data, it is observed that the CaO catalyst possesses excellent activity, and it presents good stability during the transesterification process. The catalyst was used for up to four cycles, and an apparent loss of activity was observed with the biodiesel of above 70% after the last cycle. The cost analysis of the catalyst was USD 1.17/kg, and the biodiesel cost was USD 1.39/L. Overall, the economic analysis highlights the feasibility of combining waste cooking oil with seashell-derived CaO catalysts as a sustainable biodiesel production pathway. The method dramatically lowers production costs using low-value, locally available waste resources while retaining excellent yields and fuel quality. Compared to traditional edible oil-based biodiesel, this waste-to-energy technique provides a competitive minimum selling price (MSP) and improved scalability, especially in areas with limited resources. Beyond cost savings, valorizing waste oils and seashells helps to achieve circular economy goals by reducing environmental constraints connected with waste disposal and promoting renewable fuel alternatives. These findings confirm that producing biodiesel using waste oil and seashell catalysts is not only technically feasible but also economically viable for large-scale applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.E.; methodology, A.O.E.; software, A.O.E.; validation, A.O.E. and J.K.B.; formal analysis, A.O.E.; investigation, A.O.E. and J.K.B.; resources, A.O.E. and J.K.B.; data curation, A.O.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.E. and J.K.B.; writing—review and editing, J.K.B. and A.O.E.; visualization, A.O.E. and J.K.B.; project administration, J.K.B. and A.O.E.; funding acquisition, J.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate financial support from the Mangosuthu University of Technology, South Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Masera, K.; Hossain, A.K. Advancement of biodiesel fuel quality and NOx emission control techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buasri, A.; Kamsuwan, J.; Dokput, J.; Buakaeo, P.; Horthong, P.; Loryuenyong, V. Green synthesis of metal oxides (CaO-K2O) catalyst using golden apple snail shell and cultivated banana peel for production of biofuel from non-edible Jatropha curcas oil (JCO) via a central composite design (CCD). J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2024, 28, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César, S.; Werderits, D.E.; Leal, G.; Saraiva, D.O.; Guabiroba, S. The potential of waste cooking oil as supply for the Brazilian biodiesel chain. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, S.; Sadaf, S.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, I.; Bhatti, H.N.; Nouren, S.; Rehman, H.-u.; Nisar, J.; Iqbal, M. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: An efficient technique to convert waste into biodiesel. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.R.; Nogueira, R.; Nunes, L.M. Quantitative assessment of the valorisation of used cooking oils in 23 countries. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Tao, Y.; Fei, H.; Deng, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, X.; Nie, Y. Green production of biodiesel from high acid value oil via glycerol esterification and transesterification catalyzed by nano-hydrated eggshell-derived CaO. Energies 2023, 16, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, L.; Rabiu, A.; Ojumu, T.; Oyekola, O. An Investigation of the Potential of a Bifunctional Catalyst in Biodiesel Production from Low-Cost Feedstocks. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023, 14, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiyen, S.; Naree, T.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Comparative study of natural dolomitic rock and waste mixed seashells as heterogeneous catalysts for the methanolysis of palm oil to biodiesel. Renew. Energy 2014, 74, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Rashid, U.; Patuzzi, F.; Baratieri, M.; Hin, Y. Synthesis of char-based acidic catalyst for methanolysis of waste cooking oil: An insight into a possible valorization pathway for the solid by-product of gasification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 158, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, N.S.; Nwobodo, I.; Strait, M.; Cook, D.; Abdulramoni, S.; Beng, G.; Ooi, B.G. Preparation and Characterization of Shell-Based CaO Catalysts for Ultrasonication-Assisted Production of Biodiesel to Reduce Toxicants in Diesel Generator Emissions. Energies 2023, 16, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyamoorthi, E.; Lee, J.; Ramesh, M.D.; Rithika, M.; Sandhanasamy, D.; Nguyen, N.D.; Shanmuganathan, R. Biodiesel production from eggshells derived bio-nano CaO catalyst–Microemulsion fuel blends for up-gradation of biodiesel. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, J.; Razaq, R.; Farooq, M.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, R.A.; Sayed, M.; Shah, A.; Rahman, I.u. Enhanced biodiesel production from Jatropha oil using calcined waste animal bones as catalyst. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Rathod, V.K. Waste cooking oil as an economic source for biodiesel: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaghat, B.; Abolfazl, S.; Souri, O.; Yahyavi, M. Evaluating strength properties of eco-friendly seashell-containing concrete: Comparative analysis of hybrid and ensemble boosting methods based on environmental effects of seashell usage. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.H.; Abdullah, M.O.; Kansedo, J.; Mubarak, N.M.; Chan, Y.S.; Nolasco-Hipolito, C. Biodiesel production from used cooking oil using green solid catalyst derived from calcined fusion waste chicken and fish bones. Renew. Energy 2019, 139, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summa, D.; Lanzoni, M.; Castaldelli, G.; Fano, E.A.; Tamburini, E. Trends and opportunities of bivalve shells’ waste valorization in prospect of circular blue bioeconomy. Resources 2022, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V. Valorization of Seafood Processing Discards: Bioconversion and Bio-Refinery Approaches. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 611835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odude, V.O.; Adesina, A.J.; Oyetunde, O.O.; Adeyemi, O.O.; Ishola, N.B.; Etim, A.O.; Betiku, E. Application of agricultural waste-based catalysts to transes-terification of esterified palm kernel oil into biodiesel: A case of banana fruit peel versus cocoa pod husk. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buasri, A.; Worawanitchaphong, P.; Trongyong, S.; Loryuenyong, V. Utilization of scallop waste shell for biodiesel production from palm oil—Optimization using Taguchi method. APCBEE Procedia 2014, 8, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawane, S.H.; Bora, A.P.; Kumar, T.; Halder, G. Parametric optimization of biodiesel synthesis from rubber seed oil using iron doped carbon catalyst by Taguchi approach. Renew. Energy 2017, 105, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, I.M.; Ajiwe, V.I.E.; Okoli, C.P. Performance evaluation of carbon-based heterogeneous acid catalyst derived from Hura crepitans seed pod for esterification of high FFA vegetable oil. Bioenergy Res. 2018, 11, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, A.O.; Musonge, P. The potential of waste avocado–banana fruit peels catalyst in the transesterification of non-edible Mafura kernel oil: Process optimization by Taguchi. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niju, S.; Begum, K.M.M.S.; Anantharaman, N. Enhancement of biodiesel synthesis over highly active CaO derived from natural white bivalve clam shell. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, B.; Dhawane, S.H.; Halder, G. Optimization of biodiesel production from castor oil by Taguchi design. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2684–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohain, M.; Devi, A.; Deka, D. Musa balbisiana Colla peel as highly effective renewable heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, H.; Ong, H.C.; Masjuki, H.H.; Amini, Z.; Harrison, M.D.; Wang, C.T.; Kusumo, F.; Alwi, A. Rice bran oil-based biodiesel production using calcium oxide catalyst derived from Chicoreus brunneus shell. Energy 2018, 144, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhu, K.; Proses, D.; Kulit, P. Effect of temperature in calcination process of seashells. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2015, 19, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Marinković, D.M.; Stanković, M.V.; Veli, A.V.; Avramović, J.M.; Miladinović, M.R.; Stamenković, O.O.; Veljković, V.B.; Jovanović, M. Calcium oxide as a promising heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production: Current state and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozor, P.A.; Aigbodion, V.S.; Sukdeo, N.I. Modified calcium oxide nanoparticles derived from oyster shells for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil. Fuel Commun. 2023, 14, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.S.; Verma, T.N. Taguchi design approach for extraction of methyl ester from waste cooking oil using synthesized CaO as heterogeneous catalyst: Response surface methodology optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, H.K.; Koh, X.N.; Ong, C.H.; Lee, H.V.; Mastuli, M.S.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alharthi, F.A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Mijan, N.A. Progress on Modified Calcium Oxide Derived Waste-Shell Catalysts for Biodiesel Production. Catalysts 2021, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesserwan, F.; Ahmad, M.N.; Khalil, M.; El-Rassy, H. Hybrid CaO/Al2O3 aerogel as heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seffati, K.; Honarvar, B.; Esmaeili, H.; Esfandiari, N. Enhanced biodiesel production from chicken fat using CaO/CuFe2O4 nanocatalyst and its combination with diesel to improve fuel properties. Fuel 2019, 235, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawane, S.H.; Karmakar, B.; Ghosh, S.; Halder, G. Parametric optimisation of biodiesel synthesis from waste cooking oil via Taguchi approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Sharma, D.; Soni, S.L.; Sharma, S.; Kumari, D. Chemical compositions, properties, and standards for different generation biodiesels: A review. Fuel 2019, 253, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, S.E.; Ramanathan, A.; Begum, K.M.M.S.; Narayanan, A. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using KBr impregnated CaO as catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 91, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.M.; Izriq, R.; Almaky, M.M.; Al-Abbassi, A.A. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles for the production of biodiesel by transesterification: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Fuel 2022, 321, 124135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryaputra, W.; Winata, I.; Indraswati, N.; Ismadji, S. Waste Capiz (Amusium cristatum) shell as a new heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamberi, M.M.; Ani, F.N.; Fadzli, M.; Abdollah, B. Heterogeneous transesterification of rubber seed oil biodiesel production. J. Teknol. 2016, 78, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, S.F.; Brahma, S.; Hoque, M.; Das, B.K.; Selvaraj, M.; Brahma, S.; Basumatary, S. Advances in CaO-based catalysts for sustainable biodiesel synthesis. Green Energy Resour. 2023, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaretha, Y.Y.; Prastyo, H.S.; Ayucitra, A.; Ismadji, S. Calcium oxide from Pomacea sp. shell as a catalyst for biodiesel production. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2012, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, C.; Usman, Z.; Agada, F. Biodiesel production from Ceiba pentandra seed oil using CaO derived from snail shell as catalyst. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L.; Wong, Y.C.; Tan, Y.P.; Yew, S.Y. Transesterification of palm oil to biodiesel by using waste obtuse horn shell-derived CaO catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 93, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, F. Biodiesel production via waste eggshell as a low-cost heterogeneous catalyst: Its effects on some critical fuel properties and comparison with CaO. Fuel 2019, 255, 115–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esonye, C.; Donminic, O.; Okolie, O.; Ubaka, C.; Anietie, O.; Sunday, C.; Chinedu, U.; Agu, M. Recursive neural network—Particle swarm versus nonlinear multivariate rational function algorithms for optimization of biodiesel derived from Hevea brasiliensis. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 15979–15998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, S.N.; Marchetti, J.M. Economics of biodiesel production: Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 168, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawane, S.H.; Kumar, T.; Halder, G. Parametric effects and optimization on synthesis of iron (II) doped carbonaceous catalyst for the production of biodiesel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 122, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruatpuia, J.V.L.; Halder, G.; Shi, D.; Halder, S.; Rokhum, S.L. Comparative life cycle cost analysis of bio-valorized magnetite nanocatalyst for biodiesel production: Modeling, optimization, kinetics and thermodynamic study. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.