Harnessing Energy and Engineering: A Review of Design Transition of Bio-Inspired and Conventional Blade Concepts for Wind and Marine Energy Harvesting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- What are the fundamental biological strategies that have been translated into engineering designs to improve aerodynamic and hydrodynamic performance?

- 2.

- How does interdisciplinary integration contribute to the advancement and practical realization of biomimetic energy systems?

- 3.

- What are the key challenges in scaling up biomimetic designs for real-world deployment?

- 4.

- What trends, gaps, and underexplored opportunities exist in the current literature on biomimetic strategies and conventional airfoils in aerodynamic and hydrodynamic systems?

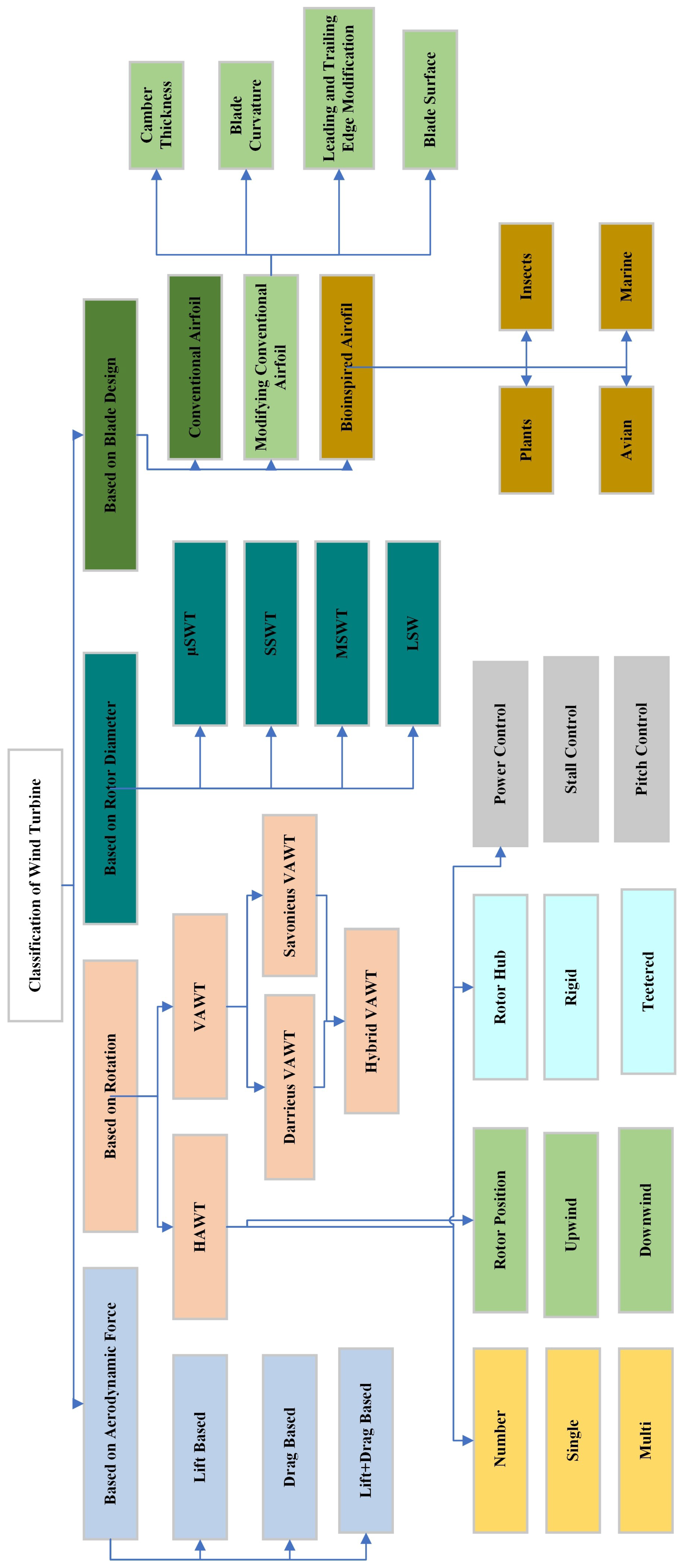

2. Design Principles and Typologies of Wind and Water Turbine

2.1. Comparison Between HAWTs and VAWTs

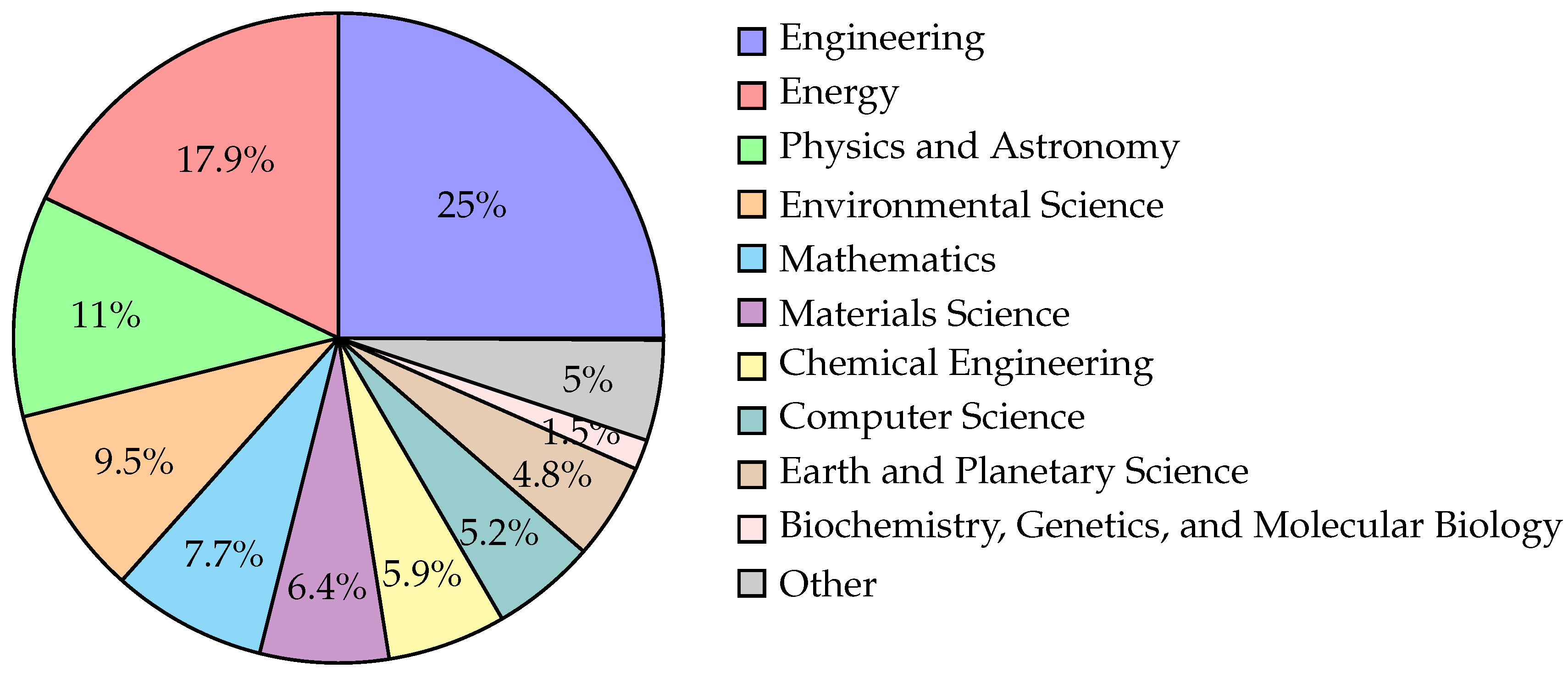

2.2. Research Methods

2.3. Conventional Airfoils and Their Modifications

2.3.1. Conventional Airfoil

2.3.2. Modified Conventional Airfoil

2.4. Bio-Inspired Airfoil

2.4.1. Harnessing Aquatic Inspiration

- (a)

- Inspiration from Fish’s Fins and Tubercles

- (b)

- Inspiration from Fish Scales to Forest Canopies

2.4.2. Inspiration from Plant Kingdom

- (a)

- Inspiration from flowers and leaves

- (b)

- Textured Surface Inspiration from Plants

2.4.3. Inspiration from Tree Seeds

- (a)

- Inspiration from Maple Seed

- (b)

- Inspiration from Borneo Camphor, Bauhinia variegata, and Mimosa Seeds

2.4.4. Inspiration from Aerial

2.4.5. Insects

3. Research Findings and Conclusions

- 1.

- Most research predominantly centers on steady-state 2D aerodynamics, neglecting unsteady effects, 3D flow, and rotational augmentation, ultimately leading to overestimated performance.

- 2.

- Despite substantial progress in biomimicry, most research on marine turbines remains hindered by methodological and conceptual limitations.

- 3.

- Most hydrokinetic studies are based on design principles derived from wind turbines; however, the large density difference between air and water introduces challenges such as scaling inconsistencies, cavitation, and increased structural load. These differences limit the direct applicability of wind-derived models and highlight the need for water-specific design and performance investigations.

- 4.

- Existing studies often restrict operating ranges by focusing on a limited set of aerodynamic parameters (e.g., lift, drag, angle of attack, velocity) while neglecting structural and environmental effects. This raises concerns about their reliability under real-world operating conditions.

- 5.

- A comprehensive understanding of the combined effects of geometric modifications, structural dynamics, and environmental influences remains limited. Current studies largely investigate these factors in isolation, yielding fragmented insights rather than holistic solutions.

- 6.

- Continued reliance on biologically augmented conventional airfoils, rather than employing high-fidelity geometries scanned directly from natural models, constrains both the realism and achievable performance of bionic designs.

- 7.

- Although the biomimetic design exhibited notable performance efficiency, its commercial deployment remains constrained because of its complex and intrinsic designs, raising concerns about its structural durability and manufacturing costs.

- 8.

- The advancement of adaptive wind and marine blades capable of dynamically adapting to environmental conditions remains limited. Bridging this gap, particularly through the integration of artificial intelligence, presents a pathway toward renewable energy systems that are not only more efficient and sustainable but also inherently adaptive, resilient, and capable of intelligent performance optimization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roy, S.; Das, B.; Biswas, A. A comprehensive review of the application of bio-inspired tubercles on the horizontal axis wind turbine blade. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 4695–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siram, O.; Saha, U.K.; Sahoo, N. Blade design considerations of small wind turbines: From classical to emerging bio-inspired profiles/shapes. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2022, 14, 042701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Feng, F.; Tagawa, K. A review on numerical simulation based on CFD technology of aerodynamic characteristics of straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbines. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4360–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass energy and biofuels: Perspective, potentials, and challenges in the energy transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, S.; Slaoui, F. Case study of hybrid wind-solar power systems for street lighting. In Proceedings of the 2011 21st International Conference on Systems Engineering, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 16–18 August 2011; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falope, T.; Lao, L.; Hanak, D.; Huo, D. Hybrid energy system integration and management for solar energy: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 21, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, S.H.; Ölçer, A.I.; Vakili, S. The application of hybrid energy system (hydrogen fuel cell, wind, and solar) in shipping. Renew. Energy Focus 2023, 46, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.J.P.; Rosa, L. Dams for hydropower and irrigation: Trends, challenges, and alternatives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, M.A.; Radi, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.; Sayed, T.S.; Salameh, T.; Alqadi, R.; Kais, E.C.A.; Olabi, A.G. Recent progress in wind energy-powered desalination. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 47, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioro, I.P.; Makarem, M.A.; Zvorykin, C.O. Wind energy utilization and sustainability. In Encyclopedia of Renewable Energy, Sustainability and the Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

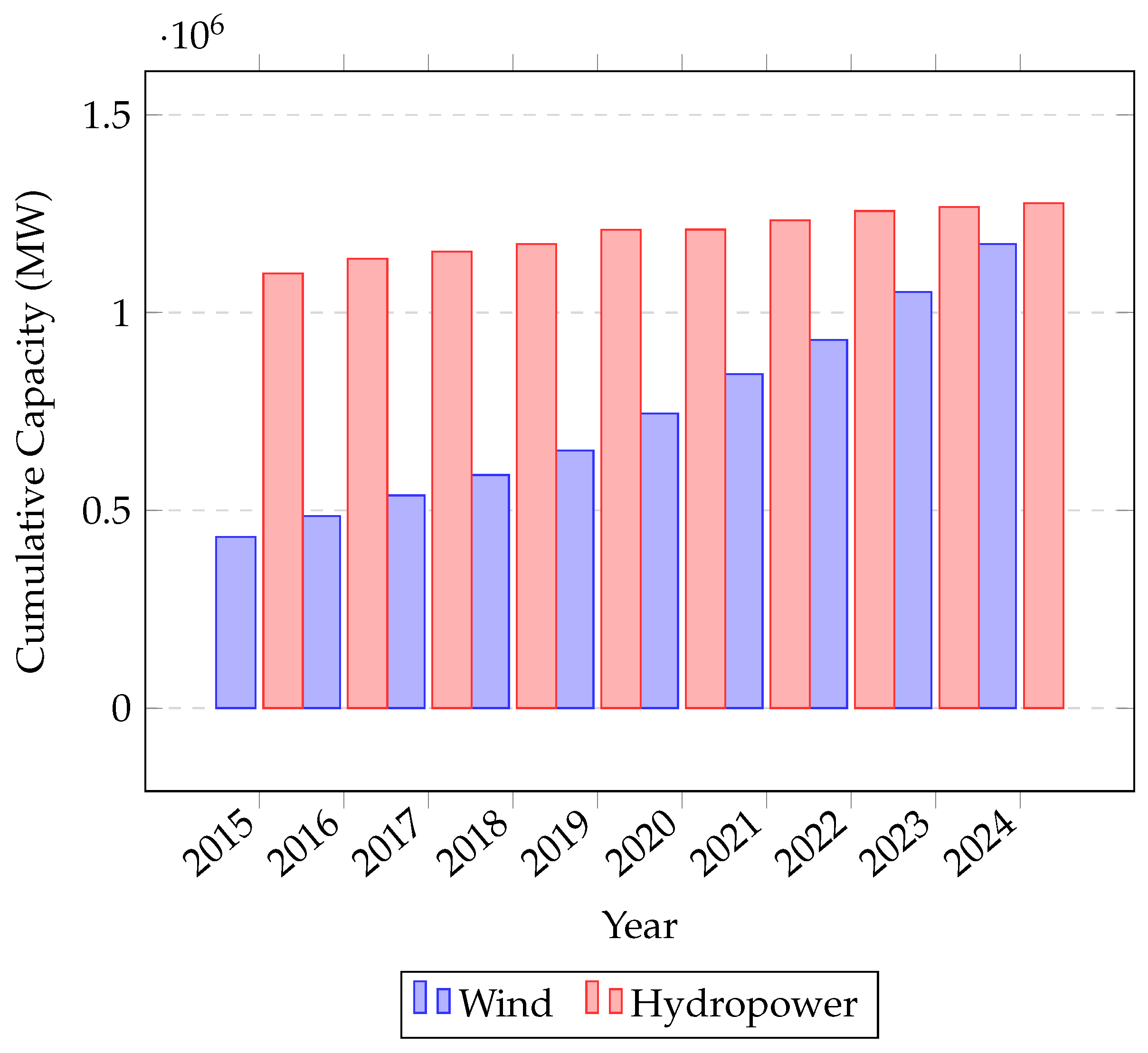

- World Wind Energy Association (WWEA). WWEA Annual Report 2024: A Challenging Year for Windpower; Technical Report; World Wind Energy Association: Bonn, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://wwindea.org/AnnualReport2024 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bahambary, K.R.; Kavian-Nezhad, M.R.; Komrakova, A.; Fleck, B.A. A numerical study of bio-inspired wingtip modifications of modern wind turbines. Energy 2024, 292, 130561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Hydropower Association. 2025 World Hydropower Outlook; Technical Report; International Hydropower Association: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.hydropower.org/publications/2025-world-hydropower-outlook (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Kinzel, M.; Mulligan, Q.; Dabiri, J.O. Energy exchange in an array of vertical-axis wind turbines. J. Turbul. 2012, 13, N38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvarnia, F.; Sarhadi, A. Nature-Inspired Designs in Wind Energy: A Review. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roga, S.; Bardhan, S.; Kumar, Y.; Dubey, S.K. Recent technology and challenges of wind energy generation: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2022, 52, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqash, T.M.; Alam, M.M. A State-of-the-Art Review of Wind Turbine Blades: Principles, Flow-Induced Vibrations, Failure, Maintenance, and Vibration Suppression Techniques. Energies 2025, 18, 3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Hung, P.A.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, M.C. Effect of the wavy leading edge on hydrodynamic characteristics for flow around low aspect ratio wing. Comput. Fluids 2011, 49, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, H.G.; Ceron, H.D.; Gomez, W.; Gaona, E.E. Experimental Analysis of Oscillatory Vortex Generators in Wind Turbine Blade. Energies 2023, 16, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.; Correa, M.; Villada, V.; Vanegas, J.D.; Garcia, J.G.; Londono, C.N.; Perez, J.S. Structural design and manufacturing process of a low scale bio-inspired wind turbine blades. Composite Structures 2019, 208, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalkarem, A.M.; Ansaf, R.; Muzammil, W.K.; Ibrahim, A.; Harun, Z.; Fazlizan, A. Preliminary assessment of the naca0021 trailing edge wedge for wind turbine application. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.D.; Rahman, S.M.; Chattopadhyay, H. Performance analysis of vertical axis wind turbine using naca0017 airfoil section. In Fluid Mechanics and Fluid Power (Vol. 3); Bhattacharyya, S., Verma, S., Harikrishnan, A.R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, A.; Singh, R.K.; Barnwal, R.; Rana, S.C. Aerodynamic characteristics of NACA 0012 vs. NACA 4418 airfoil for wind turbine applications through CFD simulation. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsakka, M.M.; Ingham, D.B.; Ma, L.; Pourkashanian, M. Comparison of the computational fluid dynamics predictions of vertical axis wind turbine performance against detailed pressure measurements. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2021, 11, 276–293. Available online: https://www.ijrer.org/ijrer/index.php/ijrer/article/view/11755 (accessed on 2 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H. Performance investigation of H-rotor Darrieus turbine with new airfoil shapes. Energy 2012, 47, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.X.; Zargar, O.A.; Lin, T.; Juan, Y.H.; Shih, Y.C.; Hu, S.C.; Leggett, G. Can bird, cetacean, and insect inspired techniques improve the aerodynamic performance of DU 06 W 200 airfoil applied in vertical axis wind turbines? Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 23, 588–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazarbhuiya, H.M.S.M.; Biswas, A.; Sharma, K.K. Blade thickness effect on the aerodynamic performance of an asymmetric NACA six series blade vertical axis wind turbine in low wind speed. Int. J. Green Energy 2020, 17, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Askary, W.A.; Burlando, M.; Mohamed, M.H.; Eltayesh, A. Improving performance of H-type NACA 0021 Darrieus rotor using leading-edge stationary/rotating microcylinders: Numerical studies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 292, 117398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demırcı, V.; Kan, F.E.; Seyhan, M.; Sarıoğlu, M. The effects of the location of the leading-edge tubercles on the performance of horizontal axis wind turbine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 324, 119178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossri, W.; Ben Ayed, S.; Abdelkefi, A. Evaluation of the efficiency of bioinspired blade designs for low-speed small-scale wind turbines with the presence of inflow turbulence effects. Energy 2023, 273, 127210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, E.; Ward, T.A.; Montazer, E.; Ghazali, N.N.N. A review of aerodynamic studies on dragonfly flight. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2019, 233, 6519–6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, C.; Jayaram, S.; Kunkel, L.; Mackowski, A. Structural Analysis of Biologically Inspired Small Wind Turbine Blades. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2017, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S. Drag and reconfiguration of broad leaves in high winds. J. Exp. Bot. 1989, 40, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regassa, Y.; Dabasa, T.; Amare, G.; Lemu, H.G. Bio-inspired design trends for sustainable energy structures. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 1294, p. 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Fan, Z.; Lei, M.; Lv, B.; Yu, L.; Cui, H. A combined airfoil with secondary feather inspired by the golden eagle and its influences on the aerodynamics. Chin. Phys. B 2019, 28, 034702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Lu, B.; Luo, D.; Rong, R.; Yang, X. CFD analysis of different leading edge tubercles on the aerodynamic performance of NREL phase VI wind turbine blades. Energy 2025, 334, 137721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Kansal, S.; Talwalkar, A.; Harish, R. CFD analysis on the influence of angle of attack on vertical axis wind turbine aerodynamics. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 850, p. 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Cruden, A.; Ng, J.H.; Wong, K.H. Variable designs of vertical axis wind turbines—A review. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1437800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Al-Obaidi, S.M.; Hao, L.C. A comprehensive review of innovative wind turbine airfoil and blade designs: Toward enhanced efficiency and sustainability. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2023, 60, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.-J.; Wang, W.-C. Review of computational and experimental approaches to analysis of aerodynamic performance in horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 63, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadhyar, A.; Sridhar, S.; Reshma, T.; Radhakrishnan, J. A critical assessment of the factors associated with the implementation of rooftop VAWTs: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, F.; Paraschivoiu, M. Computational study of the effect of building height on the performance of roof-mounted VAWT. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 241, 105540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Gherissi, A.; Altaharwah, Y. Experimental and simulation study on a rooftop vertical-axis wind turbine. Open Eng. 2023, 13, 20220465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.A.; Tasneem, Z.; Sahed, M.F.; Muyeen, S.M.; Das, S.K.; Alam, F. Towards next generation Savonius wind turbine: Artificial intelligence in blade design trends and framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budea, S.; Simionescu, Ş.M. Performances of a Savonius-Darrieus Hybrid Wind Turbine. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Energy and Environment (CIEM), Bucharest, Romania, 26–27 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, M.K.; Jalil, M.A.A.; Shariff, M.F.M. Comparison of horizontal axis wind turbine (HAWT) and vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT). Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 74–80. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328448645_Comparison_of_horizontal_axis_wind_turbine_HAWT_and_vertical_axis_wind_turbine_VAWT (accessed on 2 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nebiewa, A.M.; Abdelsalam, A.M.; Sakr, I.M.; El-Askary, W.A.; Abdalla, H.A.; Ibrahim, K.A. Static load and structural analysis of a small horizontal axis wind turbine blade: Experimental and theoretical studies using the fluid-structure interaction method. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlizan, A.; Muzammil, W.K.; Al-Khawlani, N.A. A Review of Computational Fluid Dynamics Techniques and Methodologies in Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Development. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 1371–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, G.; Gao, K.; Ju, W. Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine: Basic research methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, I.A.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Abdelfattah, M.M.; Metwaly, Z.H.; AbdelGawad, A.F. Computational and Experimental Investigation of Lotus-inspired Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine Blade. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2021, 87, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Medeiros, I.; de Lima, D.M. Structural performance of direct foundations of onshore wind turbine towers considering SSI: A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 217, 115742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognet, V.; Courrech du Pont, S.; Dobrev, J.; Massouh, F.; Thiria, B. Bioinspired Turbine Blades Offer New Perspectives for Wind Energy. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 473, 20160726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karre, R.K.; Srinivas, K.; Mannan, K.; Prashanth, B.; Prasad, C.R. A Review on Hydro Power Plants and Turbines. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2418, p. 030048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, W.; Rehman, F.; Malik, M.Z. A Review of Darrieus Water Turbines. In Proceedings of the ASME 2018 Power Conference collocated with the ASME 2018 12th International Conference on Energy Sustainability and the ASME 2018 Nuclear Forum, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 24–28 June 2018. V002TI2A015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, G.; Tan, L.; Fan, H. A Review: Design and Optimization Approaches of the Darrieus Water Turbine. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.O.L. Aerodynamics of Wind Turbines, 2nd ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, K.; Hansen, M.O.L.; Banga, G. Performance Analysis of a H-Darrieus Wind Turbine for a Series of 4-Digit NACA Airfoils. Energies 2020, 13, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokul, A.; Kurt, Ü. Comparative performance analysis of NACA 2414 and NACA 6409 airfoils for horizontal axis small wind turbine. Int. J. Energy Stud. 2023, 8, 879–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Williams, M.A.; Zidane, I.F. Elevating Wind Energy Harvesting with J-shaped Blades: A CFD-driven Analysis of H-Darrieus Vertical Axis Wind Turbines. PRoceedings Int. Marit. Logist. Conf. Marlog 13 Towards Smart Green Blue Infrastruct. Arab. Acad. Sci. Technol. Marit. Transp. 2024, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

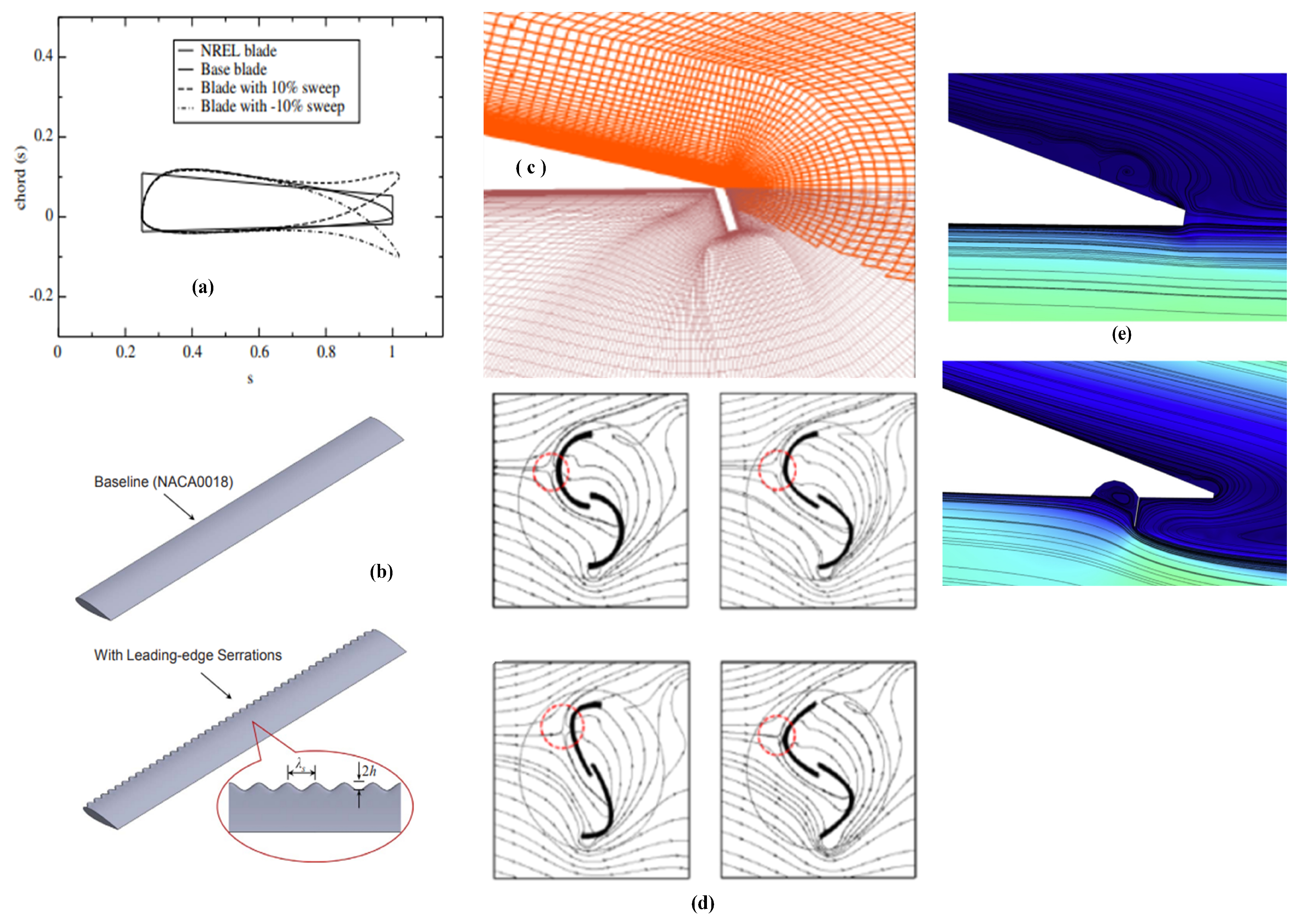

- Wang, Z.; Zhuang, M. Leading-edge serrations for performance improvement on a vertical-axis wind turbine at low tip-speed-ratios. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattot, J.J. Effects of blade tip modifications on wind turbine performance using vortex model. Comput. Fluids 2009, 38, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakroun, Y.; Bangga, G. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Airfoil and Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Employed with Gurney Flaps. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, P.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. Aerodynamic Enhancement of Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines Using Plain and Serrated Gurney Flaps. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.F.; Vijayaraghavan, K. The effects of aerofoil profile modification on a vertical axis wind turbine performance. Energy 2015, 80, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarajan, J.; Jayavel, S. Performance Improvement in Savonius Wind Turbine by Modification of Blade Shape. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2022, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayari, S.; Bouabidi, A.; Louhichi, B.; Ennetta, R. Experimental Investigation of the effects of the Phase-Shift Angle on the Performance of a Savonius Wind Turbine. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Salehi, F. Analyzing overlap ratio effect on performance of a modified Savonius wind turbine. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 125131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanegowda, T.G.; Shashikumar, C.M.; Veershetty, G.; Vasudeva, M. Numerical analysis of Savonius hydrokinetic turbine performance in straight and curved channel configurations. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M.B.; Kamaruddin, N.M.; Mohamed-Kassim, Z. Savonius hydrokinetic turbines for a sustainable river-based energy extraction: A review of the technology and potential applications in Malaysia. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2019, 36, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M.B.; Kamaruddin, N.M.; Mohamed-Kassim, Z. The effects of a deflector on the self-starting speed and power performance of 2-bladed and 3-bladed Savonius rotors for hydrokinetic application. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 61, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Guo, M.; Kang, C.; Kim, H.B. Effect of tip speed ratio on dynamic structural characteristics of Savonius hydrokinetic rotor. Ocean. Eng. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kerikous, E.; Thévenin, D. Optimal shape and position of a thick deflector plate in front of a hydraulic Savonius turbine. Energy 2019, 189, 116157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikumar, C.M.; Kadam, A.R.; Parida, R.K. Numerical studies on the performance of Savonius turbines for hydropower application by varying the frontal cross-sectional area. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 117922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbahi, M.; Ayadi, A.; Chouaibi, Y.; Driss, Z.; Tucciarelli, T. Performance study of a Helical Savonius hydrokinetic turbine with a new deflector system design. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 194, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanegowda, T.G.; Shashikumar, C.M.; Gumptapure, V.; Madav, V. Numerical studies on the performance of Savonius hydrokinetic turbines with varying blade configurations for hydropower utilization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 312, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, S.; Emam, M.; Ookawara, S.; Ahmed, M. Enhancing the performance of vertical axis hydrokinetic Savonius turbines using a novel cambered hydrofoil profile for rotor blades. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanegowda, T.G.; Shashikumar, C.M.; Gumptapure, V.; Vasudeva, M. Comprehensive analysis of blade geometry effects on Savonius hydrokinetic turbine efficiency: Pathways to clean energy. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisinger, M.; Vesenjak, M.; Hriberšek, M. Flow Driven Analysis of a Darrieus Water Turbine. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 60, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, R.; Alipour, R.; Kolloor, S.S.R.; Petrů, M.; Ghazanfari, S.A. On the Performance of Small-Scale Horizontal Axis Tidal Current Turbines. Part 1: One Single Turbine. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A. Bio-mimicry in the aerodynamics of small horizontal axis wind turbines. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2025, 76, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Hashem, I.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, B. Influence of leading-edge tubercles on the aerodynamic performance of a horizontal-axis wind turbine: A numerical study. Energy 2022, 239, 122186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklosovic, D.S.; Murray, M.M.; Howle, L.E.; Fish, F.E. Leading-edge tubercles delay stall on humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)flippers. Phys. Fluids 2004, 16, L39–L42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.S.; Abousabae, M.; Hamad, S.A.; Amano, R.S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Tubercles and Winglets Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine Blade Design. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2023, 145, 011302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Y.; Shiah, Y.; Bai, C.J.; Chong, W. Experimental study of the protuberance effect on the blade performance of a small horizontal axis wind turbine. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 147, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzon, M.D.P.; Kelso, R.M.; Arjomandi, M. Formation of vortices on a tubercled wing, and their effects on drag. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 46–55. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1270963816302383 (accessed on 2 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Bedoya, L.F.; Lebrun-Llano, D.; Espitia-Mesa, G.; Tamayo-Avendaño, J.M.; Osorio-Gómez, G. Aerodynamic Comparison of Conventional and Bioinspired Turbines for Enhanced Wind Energy Applications in Low Wind Conditions. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 612, p. 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Laws, P.; Mitra, S.; Mishra, N. Bioinspired swept-curved blade design for performance enhancement of Darrieus wind turbine. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 085189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.H. Enhancing vertical axis wind turbine efficiency through leading edge tubercles: A multifaceted analysis. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Yoon, H.S.; Jung, J.H.; Chun, H.H.; Park, D.W. Hydrodynamic characteristics for flow around wavy wings with different wave lengths. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2012, 4, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Patel, R. Experimental investigations to improve the performance of the Savonius hydrokinetic turbines using wavy edge vanes. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 161, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khder, A.; Panthi, K.; Ahmed, W.U.; Castellani, F.; Iungo, G.V. Riblets and scales on 3D-printed wind turbine blades: Influence of surface micro-patterning properties on enhancing aerodynamic performance. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 266, 106188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jiao, Z.; Song, Y.; Ren, W.; Niu, S.; Han, Z. Water-trapping and drag-reduction effects of fish Ctenopharyngodon idellus scales and their simulations. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2017, 60, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jiao, Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Yan, Y. Experimental investigations on drag-reduction characteristics of bionic surface with water-trapping microstructures of fish scales. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.W.; Tutunea-Fatan, O.R.; Bordatchenkov, E.V. Drag reduction by fish-scale inspired transverse asymmetric triangular riblets: Modelling, preliminary experimental analysis and potential for fouling control. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Xing, Q.; Chen, Z. A Review: Natural Superhydrophobic Surfaces and Applications. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 11, 110–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, H.; Li, C.; Yang, Y. Biomimetic design optimization for support structure of offshore wind turbine subjected to coupled wind and wave loadings. Thin-Walled Struct. 2026, 218, 114061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gose, J.W.; Golovin, K.; Boban, M.; Tuteja, A.; Perlin, M.; Ceccio, S.L. Characterization of superhydrophobic surfaces for drag reduction in turbulent flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2018, 845, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Sui, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Ge, A.; Coyle, T.W.; Mostagimi, J. Superhydrophobic ceramic coatings with lotus-leaf-like hierarchical surface structures deposited via suspension plasma spray process. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 38, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, Z. A comparison between superhydrophobic surfaces (SHS) and slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS) in application. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 22398–22424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, B.R.; Khalil, K.S.; Varanasi, K.K. Drag reduction using lubricant-impregnated surfaces in viscous laminar flow. Langmuir 2014, 30, 10970–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.F.; Zhan, M.S. Effect of barchan dune guide blades on the performance of a lotus-shaped micro-wind turbine. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 136, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Ja’fari, M.; Jaworski, A.J. A numerical study of horizontal axis wind turbine blade contamination: Aerodynamic and sustainable impacts. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, O.; Perot, B.; Rothstein, J.P. Laminar drag reduction in microchannels using ultrahydrophobic surfaces. Phys. Fluids 2004, 16, 4635–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, G.D.; Bhushan, B. Bioinspired rice leaf and butterfly wing surface structures combining shark skin and lotus effects. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 12139–12143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, H.; Zhong, D. A review on ice detection technology and ice elimination technology for wind turbine. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmouch, R.; Ross, G.G. Superhydrophobic wind turbine blade surfaces obtained by a simple deposition of silica nanoparticles embedded in epoxy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, L.; Green, L.; Song, K.; Wang, L.; Smith, R. Advances of drag-reducing surface technologies in turbine blades based on boundary layer control. J. Hydrodyn. 2015, 27, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Lei, J. Bio-inspired design of multiscale structures for function integration. Nano Today 2011, 6, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. Comparative study on wettability of typical plant leaves and biomimetic preparation of superhydrophobic surface of aluminum alloy. In MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Qingdoi, China, 2018; Volume 142, p. 04004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B. Rice leaf and butterfly wing effect. In Biomimetics. Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 383–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwindran, S.N.; Azizuddin, A.A.; Oumer, A.N. A Rudimentary Computational Assessment of Low Tip Speed Ratio Asymmetrical Wind Turbine Blades. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2020, 12, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwindran, S.N.; Azizuddin, A.A.; Oumer, A.N. Comparative CFD power extraction analysis of novel nature inspired vertical axis wind turbines. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 863, p. 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J.; Caley, T.M.; Turner, M.G. Maple Seed Performance as a Wind Turbine. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, AIAA, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 5–9 January 2015. AIAA 2015-1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, E.J.; Sohn, M.H. Mechanism of autorotation flight of maple samaras (Acer palmatum). Exp. Fluids 2014, 55, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, K.; Chang, S.; Wang, Z.J. The kinematics of falling maple seeds and the initial transition to a helical motion. Nonlinearity 2012, 25, C1–C16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.S.; Lai, H.N. Investigating the design parameters of maple seed’s aerodynamic force by Taguchi method to apply to wind turbine blades. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Green Technology and Sustainable Development (GTSD), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 23–24 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentink, D.; Dickson, W.B.; Leeuwen, J.L.V.; Dickinson, M.H. Leading edge vortices elevate lift of autorotating plant seeds. Science 2009, 324, 1438–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteno, T.C.A. Nature’s wind turbine: The measured aerodynamic efficiency of spinning maple seeds approaches theoretical limits. Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2022, 7, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, G.K.; Hall, N.; Somers, K.; Davis, B.; Gruszewski, H.; Powers, C.; Collver, M.; Schamale, D.G., III; Ross, S.D. Wind dispersal of natural and biomimetic maple samaras. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J.R. Experimental Testing and Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Maple Samara Flight Performance Analysis in Wind Turbine. Master’s Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2016. Available online: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=ucin1481031621058525&disposition=inline. (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Pratik, V.; Narayanan, U.K.; Kumar, P. Design analysis of vertical axis wind turbines using biomimicry. J. Mod. Mech. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 1–11. Available online: https://zealpress.com/index.php/jmmet/article/view/322/288 (accessed on 2 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.J.; Lam, H.F.; Peng, H.Y. A Thin Cambered Bent Biomimetic Wind Turbine Blade Design by Adopting the 3D Wing Geometry of a Borneo Camphor Seed. Energy Proc. 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Chu, Y.; Lam, H.; Liu, H.; Sun, S. Static aerodynamic analysis of bio-inspired wind turbine efficiency: Modeling Borneo camphor seed blade designs and their parallel plate arrangements. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 331, 119681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, P.; Manabendra, M.D. Numerical investigation of stand-still characteristics of a bio-inspired vertical axis wind turbine rotor. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 377, p. 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.J. A new biomimicry marine current turbine: Study of hydrodynamic performance and wake using software OpenFOAM. J. Hydrodyn. 2016, 28, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

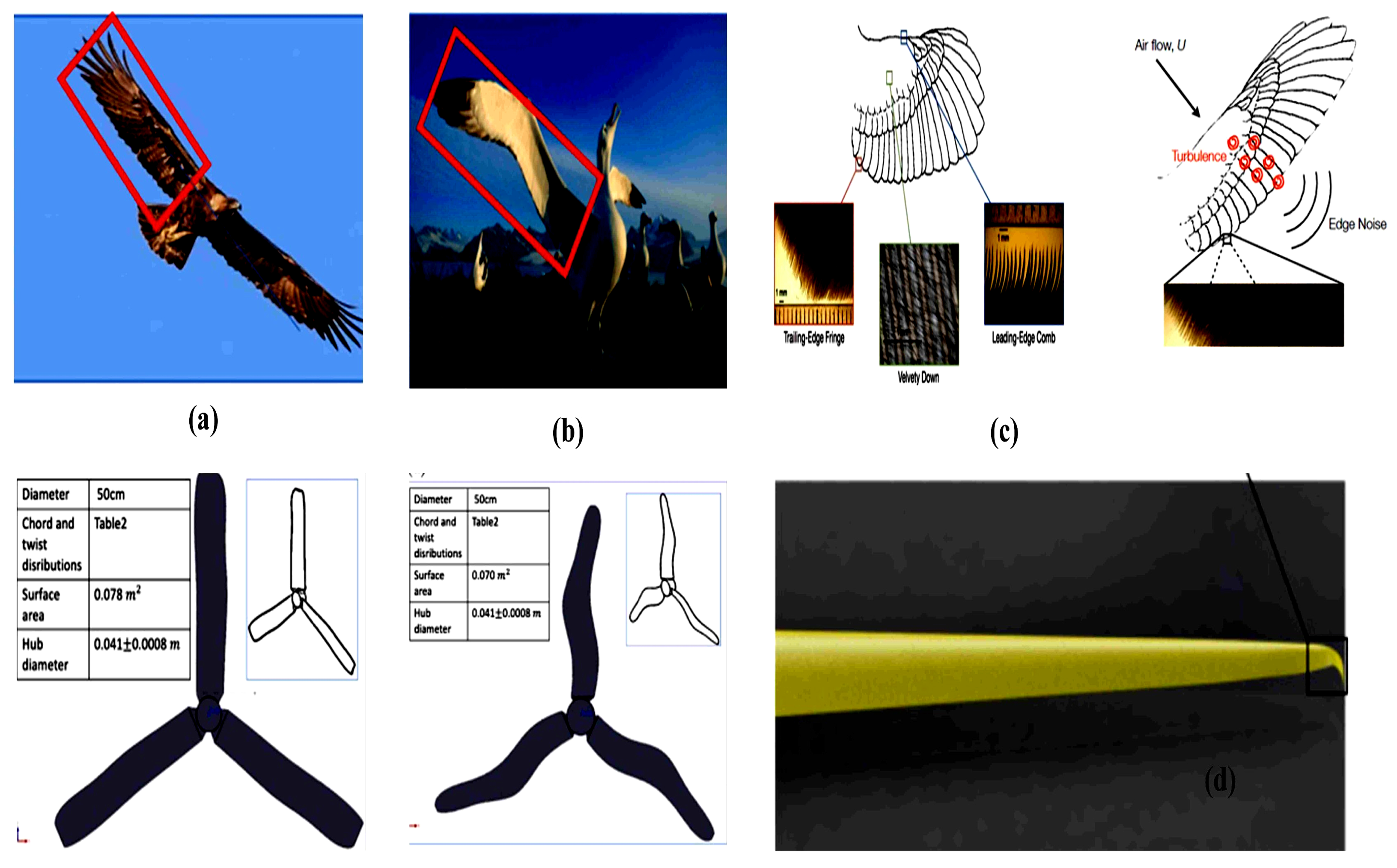

- Tian, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Cong, Q. Bionic Design of Wind Turbine Blade Based on Long-Eared Owl’s Airfoil. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2017, 2017, 8504638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, P.; Teotia, P.; Sahlot, A.D.; Thakur, H.C. An analysis of silent flight of owl. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 8571–8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesalim, D.; Naser, J. Effects of an Owl Airfoil on the Aeroacoustics of a Small Wind Turbine. Energies 2024, 17, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.R. The Silent Flight of Owls. J. R. Aeronaut. Soc. 1934, 38, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, T.; Roberts, T.; Dieppa, K.; Scherrer, J. Improved Energy Generation with Insect-Inspired Wind Turbine Designs: Towards More Durable and Efficient Turbines. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MIT Undergraduate Research Technology Conference (URTC), Cambridge, MA, USA, 3–5 November 2017; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8284198 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Zheng, L.; Hedrick, T.L.; Mittal, R. Time-Varying Wing-Twist Improves Aerodynamic Efficiency of Forward Flight in Butterflies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Physical-data driven hybrid modelling for structural optimization of buckling resistance of wind turbine blades bio-inspired by beetle elytron. Compos. Struct. 2025, 373, 119634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, R. Bio-Inspired Aerofoils for Small Wind Turbines. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 2020, 18, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | HAWT | VAWT |

|---|---|---|

| Axis Orientation [15] | Horizontal | Vertical |

| Wind Direction [16,40] | Unidirectional | Omnidirectional |

| Location [41,42,43] | Top of tower | Grounded |

| Aerodynamic Mechanism | Lift | Lift or drag |

| Maintenance | Complicated | Simple |

| Suitable Location | Mountain, isolated location | Urban building, highways |

| Self-starting | Usually good | Often needs assistance/modifications |

| Noise | Generates noise | Less noise |

| Augmenting Devices | Effect on Flow | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Whale tubercles | Restrict spanwise/radial flow | Delays stall |

| Riblets | Reduced formation of large vortices | Reduces skin-friction drag |

| Winglets | Reduced formation of large vortices | Reduces induced drag; enhances aerodynamic performance |

| Serrated trailing-edge Gurney flap (SGF) | Serrations induce secondary vortices that break columnar trailing-edge vortices | Reduced drag with maintained lift |

| Plain trailing-edge Gurney flap (PGF) | Increases circulation and effective camber | Higher lift but with greater induced drag |

| Inward semicircular dimple + small Gurney flap | Alters local pressure distribution; enhances tangential force | Reduces or eliminates light dynamic stall |

| Leading-edge sinusoidal serrations (VAWT) | Modulate leading-edge shear layer; suppress dynamic stall over azimuth | Increased power coefficient; reduced dynamic-stall extent |

| Tip modifications (sweep/dihedral/winglet) | Control tip vortices and redistribute lift along the span | Improved aerodynamic power capture |

| Grass carp | Ridges promote attached flow; crescent roughness manages turbulence | Drag reduction |

| Lotus leaf | Air retention in surface cavities reduces wetting and skin friction | Water repellency, anti-icing potential, drag mitigation |

| Rice-leaf riblets | Guide droplets/flow along span; riblet-like boundary-layer control | Viscous drag reduction; self-cleaning/antifouling |

| Owl | Disrupts coherent eddies and smooths near-edge flow | Noise reduction |

| Golden eagle | Locally adjusts camber and delays separation during rapid pitch-up | Improved manoeuvrability and torque |

| Albatross | Redistributes lift and reduces induced losses | Enhanced flight duration |

| Andean condor | Reduces tip-vortex strength and induced drag | Increased power efficiency |

| Dragonfly | Passive twist/camber traps and controls vortices | Stall delay, increased lift to drag ratio, lightweight design potential |

| Butterfly wing | Favourable pressure distribution and vortex trapping | Higher lift to drag ratio and delayed stall |

| Cicada, bee, wasp wing structure | Veins channel and stabilize flow; structural reinforcement | Increased RPM |

| Mosquito+fly long wing | Stabilizes leading-edge vortices and prolongs autorotation effects | Improved energy-extraction window |

| Maple seed | Stable leading-edge vortex (LEV), self-stabilizing autorotation | High lift to drag, low-Re performance |

| Borneo camphor seed (shuttlecock) | Autorotation expands effective rotor span; faces flow during descent | Improved lift to drag ratio and aerodynamic efficiency |

| Bauhinia/Mimosa | Helical seed-pod | Start-up at 2 m/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramakrishnan, R.; Kamra, M.; Nuaimi, S.A. Harnessing Energy and Engineering: A Review of Design Transition of Bio-Inspired and Conventional Blade Concepts for Wind and Marine Energy Harvesting. Energies 2026, 19, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010047

Ramakrishnan R, Kamra M, Nuaimi SA. Harnessing Energy and Engineering: A Review of Design Transition of Bio-Inspired and Conventional Blade Concepts for Wind and Marine Energy Harvesting. Energies. 2026; 19(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamakrishnan, Revathi, Mohamed Kamra, and Saeed Al Nuaimi. 2026. "Harnessing Energy and Engineering: A Review of Design Transition of Bio-Inspired and Conventional Blade Concepts for Wind and Marine Energy Harvesting" Energies 19, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010047

APA StyleRamakrishnan, R., Kamra, M., & Nuaimi, S. A. (2026). Harnessing Energy and Engineering: A Review of Design Transition of Bio-Inspired and Conventional Blade Concepts for Wind and Marine Energy Harvesting. Energies, 19(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010047