Abstract

Financial supply side structural reform (FSSR) serves as a key for advancing the low-carbon transformation of industrial energy (LTIE) and supporting the dual carbon strategic goals. By using provincial panel data from China for the period of 2008–2022 and leveraging the national financial comprehensive reform pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment, this study uses the difference-in-differences method to examine empirically the effect of FSSR on the LTIE and the underlying mechanisms. Research findings indicate that, first, FSSR can significantly advance the LTIE, which remained unchanged after other policies, omitted variables, and other potential influencing factors were controlled. Second, the mechanism tests indicate that FSSR can drive the LTIE by increasing green financial support, fostering green industrial development, and promoting green technological innovation. Third, the heterogeneity tests reveal that the benchmark effect is pronounced in regions with weak environmental regulation and a low level of financial development. This study provides theoretical and empirical evidence to understand the crucial role of FSSR in advancing the LTIE and insights for relevant policy formulation.

1. Introduction

In recent years, environmental problems caused by human activity have garnered widespread attention. Countries have taken proactive measures to address natural challenges, such as climate change, including regulating their carbon emissions and accelerating their transition to renewable energy. Low-carbon energy transition involves shifting the focus of energy consumption from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources to reduce the adverse environmental effects of pollution emissions from energy use [1,2,3]. According to publicly available data from the National Bureau of Statistics and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2022, China’s industrial energy consumption accounted for 67.2% of its total energy consumption in 2021, with carbon emissions from industrial activities reaching 68.5% of the national total. Industry is a major contributor to China’s energy consumption and carbon emissions; thus, the progress of industry’s low-carbon energy transition will directly affect the strategic achievement of the country’s dual carbon goals. Therefore, advancing the optimization of industrial energy structures and promoting efficiency improvements have become key pathways in national energy strategies and climate policies. In this regard, the Chinese government has formulated numerous policies and regulations to strengthen its overall environmental protection framework and drive the development of clean energy and green technology [4]. In addition, China is actively promoting and using renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, nationwide to reduce the dependence of industrial production activities on traditional energy sources [5]. Given the importance of the industrial sector, identifying an effective pathway to accelerate the low-carbon transformation of industrial energy (LTIE) remains a priority for the Chinese government in this stage.

Driving the LTIE will require substantial financial support; thus, optimizing the financial supply side and implementing structural reforms are imperative. Financial supply side structural reform (FSSR) can significantly alleviate financing constraints and further promote technological innovation among enterprises [6,7]. From a macroeconomic perspective, FSSR can play a positive role in promoting economic growth [8]. Although research has yet to thoroughly examine the effect of FSSR on the LTIE, a causal relationship may theoretically exist between the two factors, which must be elucidated further. Since 2012, China has successively established financial comprehensive reform pilot zones (NFCRPZs) with local characteristics in 11 provinces including Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Xinjiang. Such zones aim to explore locally tailored approaches to drive supply side structural reforms that can foster a two-way linkage between financial innovation and services and the real economy [9]. Can FSSR effectively drive the LTIE? What is the specific driving mechanism? Do any heterogeneous differences exist? To address the aforementioned questions comprehensively, this study utilizes the NFCRPZs as a quasi-natural experiment to examine empirically the effect of FSSR on the LTIE and the underlying mechanisms.

The contributions of this study primarily encompass three aspects. First, this study uses an improved weighted multidimensional vector angle method to measure the LTIE and thus demonstrates a degree of innovation. At the theoretical level, by breaking through the existing framework of traditional environmental research, this study explores how FSSR can influence the LTIE to provide a new perspective for understanding the theoretical mechanisms through which financial system reforms can facilitate green development. At the same time, this study conducts empirical validation. Second, research has yet to reveal the effect of FSSR on the LTIE. This study systematically examines the crucial role of green financial support (GFS), green industrial development (GID), and green technological innovation (GTI) from theoretical and empirical perspectives. Simultaneously, this study conducts an in-depth investigation into the heterogeneous differences of external factors, such as varying environmental regulation and financial development levels. Third, from a practical standpoint, by building on existing findings, this study provides empirical evidence to formulate policies that will support green development through financial reform. Furthermore, this study offers practical insights and policy implications to advance the LTIE.

2. Literature Review

Driven by the dual imperatives of economic growth and environmental governance, the LTIE has become a critical issue in China that requires in-depth research. The concept of energy transition originated in Germany, with its core essence being the shift from petroleum and nuclear power, as primary energy sources, toward renewable alternatives [10]. In 2014, the World Energy Council defined energy transition as a fundamental shift in a nation’s energy mix. Energy transition signifies the comprehensive and deep transformation of the entire energy system [11]. Research has explored the potential influencing factors of energy transition from multiple perspectives. From an internal perspective, key factors include technological innovation [12,13], chief executive officers’ risk aversion [14], and workforce gender composition [15]. Specifically, intelligent technology can accelerate the LTIE by promoting industrial structure upgrades and thus reverse the high-carbon consumption patterns of traditional energy- and carbon-intensive industries [13]. From an external perspective, key factors include financial system support [16], environmental regulation [17], and the digital economy [18]. For example, the digital economy is an economic model that relies on emerging technology, such as big data, the Internet of things, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. The digital economy can achieve high-quality economic and industrial development with the input of key production factors, such as digital knowledge and information. Characterized by the distinct features of intelligence, networking, platformization, and sharing, the digital economy can lead the green and low-carbon transformation of industries from multiple dimensions across society [18]. Regarding measurement approaches, research has proposed multiple metrics. For instance, energy structure transformation has been measured by the proportion of clean energy consumption in the total energy consumption [19]. In recent years, most scholars employed two methods to calculate the “energy decarbonization index”: Kaya-based indicators and aggregated indicators. However, the two methods have certain limitations. Analysis of carbon content in energy consumption to construct an index is a sound approach [20]. Wan et al. employed the weighted multidimensional vector angle index to measure the low-carbon transition of energy [21]. However, the method has yet to be used in the industrial sector. This study attempts to measure the LTIE by using the aforementioned method.

The LTIE is characterized by substantial investments, high risks, and extended timelines, with the underlying cause being the misallocation of resources within the traditional financial system. The overarching objective of the NFCRPZs is to establish a diversified modern financial system that is commensurate with its level of economic development to address the distortions in the allocation of financial resources and reduce the regulatory constraints on financial innovation. The objective can enhance the capability of financial services to support the real economy [22] and thus meet the practical demands of the LTIE.

The NFCRPZ policy is a key tool for implementing FSSR, which exerts a distinct effect at the macro and micro levels. At the macro level, domestic financial and trade reforms are closely associated with economic growth [8]. At the meso level, comprehensive financial reforms can significantly enhance urban resilience through technological innovation and industrial clustering [23]. Notably, financial policy innovations send a positive signal to the outside world of the importance of the transformation of high-pollution industries. That is, institutional frameworks may play a role in fostering environmental innovation to a certain extent [24]. In terms of GID, FSSR can enhance capital aggregation in green industries and strengthen market information transmission [25], which can facilitate the improvement of investment efficiency in green industries, with a particularly pronounced effect on the clean energy sector [26,27]. At the micro level, comprehensive financial reform is conducive to improving corporate operations. For example, fintech is defined as financial innovation that is achieved through the introduction of advanced technology, such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and big data, into the financial sector [28]. Such technology can substantially alleviate corporate financing constraints by mitigating information asymmetry [6]. As the NFCRPZ policy is implemented progressively, industrial enterprises have begun to prioritize the low-carbon energy transition of their production models. The financial resources that flow into such sectors can address their deep-seated development needs while enhancing their investment efficiency [29] and thus significantly boost corporate green innovation [7]. Although the literature has elucidated the significant economic and social impact of FSSR, it has yet to explore the underlying mechanisms for the LTIE. This gap serves as a research opportunity for this study.

In summary, the literature has conducted in-depth research on the factors that can influence the LTIE and the economic consequences of FSSR. However, it has limitations. First, from the perspective of metric measurement, existing methods exhibit certain limitations. This study innovatively employs an improved weighted multidimensional vector angle method to address such shortcomings. Although research has examined the link between the financial and industrial sectors [30,31], it has yet to delve into the effect of FSSR on systems involved in the LTIE. Thus, gaps exist in the literature. This study discusses the topics comprehensively to fill such gaps. Second, the mechanism through which FSSR can affect the LTIE has yet to be revealed. This study further examines the crucial role of GTI, GFS, and GID to fill the research gaps. Finally, this study further examines heterogeneous variations in external factors, such as differing environmental regulation and financial development levels, to deepen its investigation.

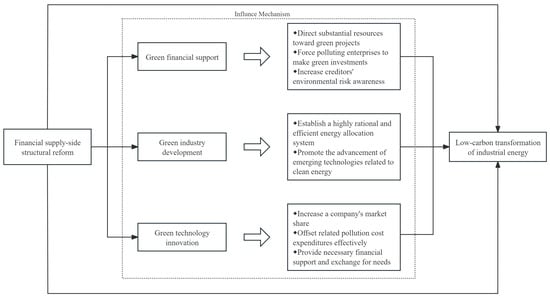

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

FSSR is a long-term institutional innovation that aims to serve the real economy effectively by optimizing the allocation of financial resources and adjusting the financial structure [32]. The traditional financial system is suffering from severe financial resource misallocation [33], which can significantly hinder the progress of the LTIE. FSSR can address the issue, as manifested primarily in three aspects. First, FSSR can significantly enhance financial resource allocation efficiency to effectively address the challenge of “difficult and costly financing” faced by real economy enterprises. FSSR can guide substantial financial resources toward green enterprises through factor allocation and thus effectively curb the flow of resources to polluting enterprises [34]. This scenario can incentivize green enterprises to advance their development and compel high-energy-consuming and high-polluting enterprises to pursue low-carbon transformation. The scenario can further drive the industrial sector to shift from reliance on traditional high-carbon energy sources toward reliance on clean energy alternatives to achieve enhanced energy efficiency [35]. Second, FSSR can enhance organizations’ operational efficiency. FSSR has optimized the corporate investment structure and efficiency [29] and thus can further guide the precise implementation of green innovation projects and promote widespread application in the field of industrial decarbonization. The upgrading and optimization of industrial structures can be achieved by effectively ensuring the availability of funding [36], which can drive the LTIE. Finally, FSSR can strengthen financial system regulation to ensure the stability of financial resource supply and demand [37]. Under the FSSR framework, the management of special funds has become highly standardized. Such conditions have enhanced financial resource utilization efficiency, effectively mitigated the associated risks, and maximized support for the development of green projects in the industrial sector to achieve the LTIE. On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

FSSR can positively drive the LTIE.

FSSR can facilitate the adjustment and optimization of the traditional financial system and thus provide institutional safeguards for GFS and promote coordinated economic and environmental development. FSSR can enhance GFS and thus promote improved financial services for the real economy and guide green industrial upgrading [38,39]. Under the FSSR framework, green finance can broadly encourage social environmental protection and guide financial markets toward eco-friendly investments [40].

Owing to growing societal concern about environmental issues, improving the green financial service system and developing new green finance projects have become key strategies for advancing the LTIE [41]. FSSR can enable green finance to break through the traditional financial system. On the one hand, it can channel increased resources toward green projects, incentivize green innovation activities to enhance competitive advantages, and reduce financing and transaction costs for green enterprises [34]. On the other hand, FSSR can increase environmental costs for high-energy-consuming and high-polluting enterprises through the dual effects of penalties and incentives. This situation can compel profit-maximizing polluting enterprises to pursue green investments, improve their processing techniques, and achieve low-carbon transformation [42]. At the same time, FSSR can increase creditors’ environmental risk awareness to a certain extent [43] and thus further promote the LTIE. On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

FSSR can drive the LTIE by increasing GFS.

FSSR can promote the development of financial markets to guide credit resources and social capital away from high-carbon sectors toward green industries and provide stable and reliable financial support for the LTIE [44]. For example, in China and India, financial markets have become the primary financing channel for clean energy industries [45]. In addition, stock market development can exert a significant positive effect on clean energy [46]. FSSR can alleviate economic pressures associated with clean energy targets [44] and thus provide essential support for GID.

GID has driven the LTIE in two aspects. First, green industries focus on adjusting the proportion of various energy sources within the total energy mix to establish a highly rational and efficient energy allocation system. The approach can control fossil fuel consumption and achieve the LTIE [47]. Second, GID can drive the upgrading of emerging technology related to clean energy [48,49], enhance energy efficiency, and accelerate energy substitution and thus demonstrates considerable potential in long-term energy intensification. On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

FSSR can drive the LTIE by fostering GID.

In the process of economic transformation and development, GTI represents an innovative practice within the environmental technology sector. GTI by enterprises is characterized by high risks, long payback periods, and uncertain returns and thus requires robust financial support [50]. FSSR can broaden corporate financing channels and enable risk hedging throughout the innovation process and thus ensure the smooth progression of GTI activities [23]. Moreover, FSSR can prompt green enterprises to develop green technology by squeezing out traditional high-polluting, high-energy-consuming enterprises [51]. Compared with other enterprises in the industrial sector, green enterprises will more likely secure financial support and thus facilitate the promotion of GTI.

GTI can increase a company’s market share and core competitiveness and effectively offset related pollution costs and thus generate an innovation compensation effect [31], which can help promote technological decarbonization in the industrial sector and achieve energy efficiency improvements. Furthermore, GTI can provide viable solutions for the transformation and upgrading of traditional industries and thus achieve efficient resource utilization, reduce pollution, and protect the environment. GTI can also offer essential financial support and demand exchange for the energy sector. Specifically, green technology can optimize production processes and reduce energy waste to lower carbon emissions within high-carbon-emissions industrial sectors [52,53]. The condition can ultimately drive the LTIE and achieve the win–win outcome of economic growth and environmental protection. On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

FSSR can drive the LTIE by promoting GTI.

The impact mechanism is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Impact mechanism.

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study utilizes panel data from 30 provinces in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet) covering the period of 2008–2022, comprising a total of 450 observations. The specific data sources are the China Statistical Yearbook, China Insurance Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, China Electric Power Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, National Intellectual Property Administration, Qiyan Database, China Emission Accounts and Datasets, Wind Database, China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database, and EPS Database.

4.2. Main Variables

4.2.1. LTIE Measurement

By referring to the methodology of [21], this study constructs an LTIE index based on an improved weighted multidimensional vector angle method to measure the low-carbon energy transition of regional industrial sectors comprehensively. The construction of the index involves three steps.

First, this study assumes that m types of energy sources exist, with the highest to the lowest carbon emissions. The consumption share of each energy type is (j = 1, 2, …, m). Based on the aforementioned information, this study constructs an m-dimensional vector space for the energy structure Et(,, …,).

Second, this study ranks the m types of energy consumed in industrial processes from highest to lowest based on their unit thermal value carbon emissions coefficient. This study uses the theoretical lower-bound structure as the baseline vector (1, 0, …, 0).

Third, this study calculates vector angle between the industrial energy consumption structure vector …, at period t and from the structural shift in the jth energy source. The calculation is as follows:

In this context, and represent the angles that are calculated relative to the reference vector and current vector, respectively, to avoid overestimation or underestimation. The specific calculation is as follows:

This study derives the industrial energy structure decarbonization index through weighted synthesis, as follows:

This study analyzes a total of 25 energy categories, such as coke and raw coal, and converts all the energy types into standard coal equivalents. The low-carbon level ranking of each energy category is based on its carbon emissions coefficient per unit of calorific value. A high carbon emissions coefficient per unit of calorific value indicates a low level of low carbonization.

4.2.2. Difference-in-Differences Measurement

Since 2012, the Chinese government has implemented a series of FSSR policies in phases to enhance the capacity of financial services to support the real economy. Given the interconnectedness and continuity of such policies, by referring to the methodology of [7], this study employs the NFCRPZs as a quasi-natural experiment. The 11 provinces and municipalities comprising the pilot zones (Table 1) serve as the experiment group, whereas the remaining provinces constitute the control group. This study assigns a value of 1 to the provinces and municipalities included in the NFCRPZs in the current and subsequent years and 0 to those that are not included in the zones.

Table 1.

Provinces that Implemented the NFCRPZs Policy and their Implementation Timeline.

4.2.3. Mediating Variable Measurement

The key mechanism variables in this study are as follows: (1) GFS—green finance is a financial service centered around the core values of human survival and environmental benefits to achieve sustainable development. By referring to the methodology of [54], this study constructs an indicator system that comprises green credit, green investment, green insurance, and carbon finance. The indicator employs the entropy weight method to calculate the comprehensive green finance index. (2) GID—as the core engine of green development, the new energy industry’s scale expansion can directly determine the progress of the attainment of carbon neutrality goals, making it a crucial indicator of GID. By referring to the methodology of [55], this study measures the growth of new energy enterprises by taking the natural logarithm of their incremental value plus 1. (3) GTI—green patents are the outcome of innovation activities and serve as a core indicator of the actual status of GTI. By referring to the methodology of [21], this study measures GTI by using the number of green patents granted.

4.2.4. Control Variable Measurement

This study selects several control variables on the basis of previous research [56,57]. (1) Economic development level (PGDP) is measured by taking the natural logarithm of the per capita gross domestic product (GDP). (2) Industrial governance investment (IPCI) is measured by using the total amount of industrial governance investment. (3) Industrial air pollution (SO2) is measured by using the natural logarithm of sulfur dioxide emissions. (4) Industrial solid waste pollution (ISWG) is measured by using the natural logarithm of the total industrial solid waste volume. (5) Industrial enterprise scale (FAC) is measured by taking the natural logarithm of the total number of industrial enterprises. (6) Population density (POPU) is measured by employing the population per unit area of administrative divisions. (7) Foreign direct investment (FDI) is measured by taking the natural logarithm of the actual amount of foreign capital utilized in each province.

4.3. Empirical Model

This study adopts the methodology of [7] to assess the effect of FSSR on the LTIE accurately. This study constructs a multiperiod difference-in-differences (DID) model for empirical testing by using the NFCRPZs as a quasi-natural experiment, as detailed in Equation (5).

where denotes the LTIE, indicates inclusion in an NFCRPZ, represents a set of control variables, represents provincial fixed effects, represents annual fixed effects, and represents the error term. In Equation (5), if coefficient is significantly positive, then FSSR can significantly drive the LTIE.

This study uses the methodology of [58] and builds on Equation (5) to construct Equation (6) to further investigate the mechanism through which FSSR can drive the LTIE.

where represents the mechanism variables, such as GFS, GID, and GTI. The definitions of the variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variable Definitions.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

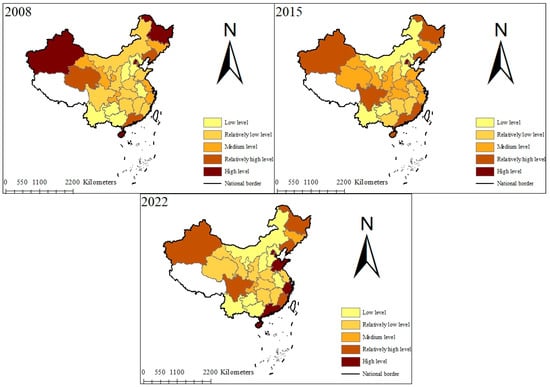

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables. The mean value of LTIE is 0.204, with a standard deviation of 0.080. The minimum and maximum values of LTIE are 0.091 and 0.426, respectively, which indicate significant regional disparities in the industrial low-carbon transition level and an overall low baseline. From temporal and spatial perspectives, the changes in LTIE are highly evident, with the pilot provinces generally performing well overall, as shown in Figure 2. The mean value of DID is 0.209, which indicates that approximately 20.9% of the provinces in the sample are within the NFCRPZs. Overall, the median values of GFS, GID, and GTI are relatively low, which suggest that more than half of the provinces exhibit suboptimal levels. The distribution characteristics of the control variables are reasonable and consistent with those in previous studies.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics.

Figure 2.

Spatiotemporal evolution trend of LTIE (Drawing Review Number: GS(2024)0650. No changes to the map).

5.2. Baseline Regression

Table 4 presents the baseline regression results of the effect of FSSR on LTIE. Columns (1)–(3) provide the regression results for the current period, one period lagged, and two periods lagged. The regression coefficient of DID is statistically significant at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, which indicates that FSSR can significantly drive LTIE. Moreover, it exhibits a continuously strengthening dynamic effect as the NFCRPZ policy progresses in depth; thus, Hypothesis 1 is validated.

Table 4.

Baseline Regression Results.

Among the control variables, PGDP significantly and positively influences the transition process, which indicates that environmental concerns gain prominence as economic growth progresses, and thus can facilitate the LTIE. Conversely, SO2 and ISWG exhibit negative correlations, which signify that pollution emissions can severely impede the LTIE. This result meets the theoretical expectations of this study.

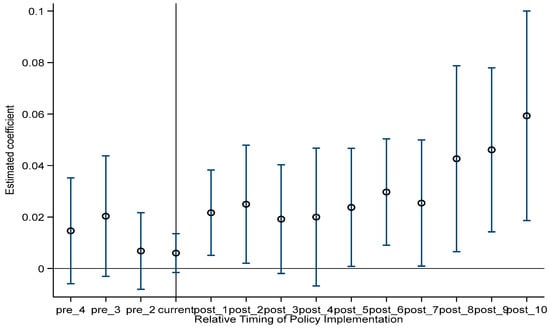

5.3. Parallel Trends Analysis

The application of the multiperiod double-difference method requires satisfying the parallel trends assumption, which aims to determine whether the experiment and control groups maintain consistent change trends prior to policy implementation. By referring to the methodology of [59], this study constructs Equation (7) by using the event analysis approach.

where j denotes the jth year after the implementation of the policy in the NFCRPZs, j = 0 represents the year of the policy implementation, j < 0 indicates the j years preceding the implementation, and j > 0 signifies the j years following the implementation. In addition, this study uses the year preceding the policy implementation as the base period and excludes it from the analysis. The results of the parallel trends test are presented in Figure 3. Prior to policy implementation, the difference in the LTIE levels between the experiment and control groups is not significant, which satisfies the parallel trends assumption. As the NFCRPZ policy progresses, the estimated coefficients for the subsequent years become consistently positive and reach a level of significance. This finding indicates that, after the implementation of the NFCRPZ policy, the level of the LTIE in the pilot provinces exhibited a marked improvement.

Figure 3.

Parallel trends test results.

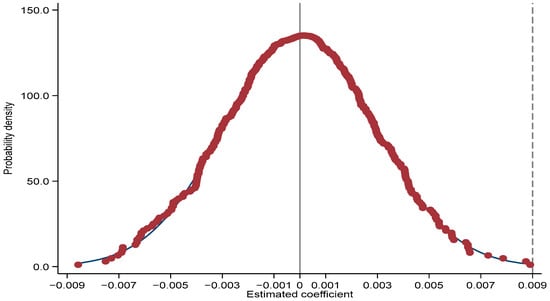

5.4. Placebo Test

Although this study controls for multiple variables that represent provincial characteristics in the multiperiod DID model, the results may be subject to interference from unobserved variables. To eliminate the influence of potential unobservable factors, this study conducts a placebo test by using dummy policy variables, with reference to the research paradigm of [60]. Specifically, this study randomly generates 500 simulated false policy shocks, and the results are presented in Figure 4. The estimated coefficients from the random replication of the “pseudo” treatment group for the policy effect testing cluster around zero and follow a normal distribution, all falling below the baseline regression coefficient of 0.009. This finding indicates that the baseline regression results are valid and confirms that FSSR can robustly drive the LTIE.

Figure 4.

Placebo test results.

5.5. Robustness Tests

This study controls for the effects of other policies implemented during the same period. Given the long-term nature of the NFCRPZ policy, the simultaneous or overlapping implementation of other related policies can potentially confound our research results. To identify and control for the effects of other policies, this study draws on existing policies and the literature [61,62] and separately examines the causal relationship between FSSR and the LTIE under the distinct influence of the carbon emissions trading pilot city policy (Carbon_pilot), the low-carbon city pilot policy (Low_carbon), and the key air pollution control zone pilot policy (KCApost), as detailed in Table 5. The results in Columns (1)–(3) indicate that the policy effect of FSSR remains statistically significant after each of the three policy variables is incorporated, thereby confirming the basic findings.

Table 5.

Robustness Tests.

This study controls for the interference of the omitted variable error. To eliminate the effect of the omitted variable error on the baseline conclusions, this study further controls for the effects of industrial structure (IS) and government fiscal intervention (Gov) [63,64]. This study measures IS by using the share of the tertiary industry value-added in the GDP and Gov by using the share of local government budget expenditures in the GDP. As indicated in Column (4), the regression coefficient of FSSR remains significantly positive for LTIE, which further supports the previously drawn conclusions.

6. Further Analysis

6.1. Mechanism Analysis

The baseline regression results in Table 4 validate that FSSR can significantly drive LTIE. Column (1) of Table 6 presents the effect of FSSR on GFS. The regression coefficient of DID is 0.001 and significant at the 1% statistical level, which demonstrates that FSSR can significantly increase GFS. Increasing GFS can effectively alleviate resource misallocation [34] and thus help resolve financing challenges in the LTIE. On the one hand, green finance can penalize high-carbon emitters by increasing their environmental compliance costs. On the other hand, green finance can provide the green enterprises in the industrial sector with expanded financing channels and reduced financing and transaction costs and thus accelerate their growth and vigorously advance the LTIE [41]. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is verified.

Table 6.

Mechanism Analysis.

Column (2) of Table 6 presents the results of the effect of FSSR on GID. The regression coefficient of DID is 0.160 and statistically significant at the 1% level. The finding suggests that FSSR can significantly support GID. The development of green industries, such as new energy, can optimize energy consumption structures and curb carbon emissions [47], whereas financial markets can provide critical safeguards for green industry growth [44]. FSSR can support the widespread application of emerging technology, such as energy storage, and thus enhance energy efficiency and accelerate energy substitution. Such conditions can significantly boost the LTIE [49]. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is validated.

Column (3) of Table 6 presents the results of the effect of FSSR on GTI. The regression coefficient of DID is 0.379 and statistically significant at the 1% level. The finding suggests that FSSR can significantly promote GTI. Green innovation activities can accelerate the renewal and iteration of emerging green technology and thus exhibit a significant innovation compensation effect [31], which can help create a virtuous cycle of green development in the real economy. Emerging green technology can optimize production processes in the industrial sector, enhance energy efficiency, and curb carbon emissions [53] and thus advance the LTIE. Hence, Hypothesis 4 is verified.

6.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Regional variations in provincial conditions may influence the relationship between FSSR and the LTIE. This study examines the heterogeneous effects of FSSR on the LTIE from two perspectives: environmental regulation and financial development.

The effectiveness of FSSR is susceptible to environmental regulation. Environmental oversight strengthening can effectively enhance financial resource allocation efficiency. By referring to the methodology of [65], this study uses the frequency of keywords related to environmental regulation in local government reports to measure environmental regulation. This study divides the sample into a low environmental regulation group (Low_ER) and a high environmental regulation group (High_ER) based on the median. As indicated in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 7, the regression coefficient of DID in the Low_ER group is 0.020 and significant at the 1% level. The finding indicates that FSSR exerts a pronounced effect on the sectoral promotion of the LTIE in provinces with weak environmental regulation. A possible explanation for this result is that weak local environmental regulation can reduce the cost of environmental violations, which can lead enterprises to prioritize resource allocation to expand their production capacity, rather than reduce their emissions [66]. FSSR can effectively compensate for such shortcomings through market-based measures, such as differentiated credit policies and green bonds, and thus exert a highly pronounced effect on the LTIE.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity Analysis.

Meanwhile, the financial system is one of the core entities that can integrate virtual and real sectors in modern economies. Regional financial development may influence the implementation of FSSR. By referring to the methodology of [67], this study measures financial development by using the ratio of deposit and loan balances to the local GDP and divides the sample into a low financial development group (Low_FD) and a high financial development group (High_FD) based on the median. As indicated in Table 7 Columns (3) and (4), the regression coefficient of DID in the Low_FD group is 0.019 and significant at the 1% level. The finding indicates that FSSR exerts a pronounced driving effect on the LTIE in provinces with low-level financial development. Provinces with low-level financial development typically face issues such as inadequate financial service systems and limited financing channels for enterprises. FSSR can enhance the efficient allocation of financial resources and thus demonstrates strong marginal effects [68].

7. Discussion

China is currently in a critical window period for achieving its dual carbon goals [41]. The industrial sector, as the primary contributor to energy consumption and carbon emissions, plays a pivotal role in achieving the nation’s overarching strategic objectives through its low-carbon transition [69]. However, the path to transformation is fraught with challenges. The inertia of traditional high-carbon industrial systems is strong, with pronounced lock-in effects on technological pathways and high transition costs. Meanwhile, GTI involves long cycles and high risks [31]. Green industries require substantial, long-term, and low-cost financial support during their early development stages. The traditional financial system is fraught with structural contradictions, rendering it incapable of providing effective assistance to the LTIE. Previous studies suggested that financial system innovation can help drive the low-carbon transition of the energy sector [21,56]. The primary and core finding of this study is that FSSR can significantly drive the LTIE. The finding underscores the importance of FSSR as a major strategic initiative in China and is consistent with that of previous studies. Within the international community, financial resource support is also regarded as a key means to drive the low-carbon transformation of energy [70]. Strengthening financial innovation to address challenges and changes across different periods is equally essential [71]. The findings drawn in this study offer valuable insights for other countries worldwide.

Previous studies examined the impact of financial policies on low-carbon transition from a single perspective, such as technological progress, but rarely conducted systematic analysis [72,73]. This study reveals three specific transmission pathways from the perspective of green development: increase in GFS, facilitation of GID, and promotion of GTI. The mechanism analysis can considerably deepen our understanding of how FSSR can affect the LTIE. FSSR can redirect financial resources toward green projects by reshaping capital flows and thus effectively curb the allocation of resources to polluting enterprises [34]. This can provide financial backing to green industries and guide their industrial restructuring toward low-carbon development through market signals [35]. At the same time, FSSR can stimulate vitality in green technology R&D and thus safeguard corporate innovation. Compared with previous studies, this study offers a more comprehensive framework by organically linking financial support, industrial upgrading, and technological innovation.

This study also examines the heterogeneous effects of external factors such as environmental regulation and financial development. The findings provide some important insights. Specifically, in regions with stringent environmental regulation, strict administrative orders and penalties will impose strong constraints on high carbon emissions [74]. Thus, the LTIE serves primarily as a passive choice driven by compliance pressures and hence can potentially obscure the marginal effects of financial policies. Conversely, in areas with weak environmental regulation, where administrative constraints fall short, market-based financial incentives are crucial in filling regulatory gaps and driving the LTIE. Similarly, in regions with a low level of financial development, financial resource allocation may be distorted [75]. FSSR can expand the resource allocation scope and exert a pronounced effect on the LTIE. For regions with relatively weak environmental governance and financial systems, FSSR can serve as a crucial mechanism for addressing institutional shortcomings and promoting coordinated green development.

We must be acutely aware that the impact of FSSR on the LTIE may be accompanied by certain challenges and unintended consequences. In guiding financial resources toward large-scale, long-term investment in green and low-carbon sectors, the identification and management of financial risks are crucial. The success of FSSR will require not only incentive mechanisms but also complementary risk-monitoring, early warning, and risk-sharing mechanisms to ensure its sustainability. The neglect of the risk dimension may expose the LTIE process to disruptions caused by financial turbulence. In addition, regional disparities, institutional quality, and economic reforms may lead to unintended consequences. Overall, emphasizing policy adaptability, refining market mechanisms, and mitigating risks are crucial to ensuring the smooth implementation of the LTIE during FSSR.

8. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Advancing the LTIE is a crucial strategic measure for achieving the “3060” dual carbon goals. FSSR can provide the necessary funding and policy support; thus, examining industrial energy decarbonization through the perspective of FSSR is important. By using provincial panel data from China for the period of 2008–2022 and leveraging the NFCRPZs as a quasi-natural experiment, this study uses the DID method to empirically examine the effect of FSSR on the LTIE and the underlying mechanisms. The research findings indicate that, first, FSSR can significantly advance the LTIE. The conclusion remains unchanged after other policies, omitted variables, and other potential influencing factors were controlled. Second, the mechanism tests indicate that FSSR can drive the LTIE by increasing GFS, fostering GID, and promoting GTI. Third, the heterogeneity tests indicate that the benchmark effect is highly pronounced in the regions with weak environmental regulation and a low level of financial development.

On the basis of the aforementioned research findings, the current study proposes the following policy recommendations. First, the proven experiences of NFCRPZs in advancing LTIE are summarized and synthesized, providing practical references for other regions. Aligned with the key tasks outlined in the Guiding Opinions on Further Strengthening Financial Support for Green and Low-Carbon Development, local governments should elevate effective innovative explorations into exemplary models for dissemination and sharing, while simultaneously establishing universally applicable practical pathways. Second, the deep enabling role of GFS, GID, and GTI in LTIE should be enhanced. Focusing on typical high-energy-consumption and high-carbon-emission industries, such as steel, building materials, nonferrous metals, and petrochemicals, targeted industrial energy low-carbon transformation service modules must be developed. Local governments should provide dedicated funding support to foster green industry growth and improve financial service mechanisms for green industries. Third, differentiated financial service strategies must be applied to achieve tailored approaches. Local governments should consider differentiated financial support measures based on provincial conditions, leveraging financial tools in tandem with environmental governance to promote the precise implementation of FSSR strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W., Y.N. and T.F.; methodology, Z.W. and T.F.; software, Z.W.; formal analysis, Y.N. and T.F.; data curation, Z.W. and Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W., Y.N. and T.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. and T.F.; funding acquisition, Z.W. and T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Soft Science Research Program of Zhejiang Province, grant number 2024C35G2101766; the Major Humanities and Social Sciences Research Projects in Zhejiang Higher Education Institutions, grant number 2024QN138; the Zhejiang Province University Student Science and Technology Innovation Activity Plan and New Talent Program Funding Project, grant number 2025R412A019; the National Undergraduate Innovation Training Program, grant number 202513283015.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to database access restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FSSR | Financial supply side structural reform |

| LTIE | Low-carbon transformation of industrial energy |

| GFS | Green financial support |

| GID | Green industrial development |

| GTI | Green technological innovation |

| NFCRPZs | National financial comprehensive reform pilot zones |

References

- Siciliano, G.; Wallbott, L.; Urban, F.; Dang, A.N.; Lederer, M. Low-carbon energy, sustainable development, and justice: Towards a just energy transition for the society and the environment. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Ahmed, M.F.; Lim, C.K. Enhancing sustainable development via low carbon energy transition approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Lekavicius, V.; Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. Energy poverty and low carbon just energy transition: Comparative study in Lithuania and Greece. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 158, 319–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Jiang, K.; Han, P.; Hausfather, Z.; Cao, J.; Kirk-Davidoff, D.; Ali, S.; Zhou, S. The Chinese carbon-neutral goal: Challenges and prospects. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 39, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Di Maria, C.; Ghezelayagh, B.; Shan, Y. Climate policy in emerging economies: Evidence from China’s low-carbon city pilot. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2024, 124, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. FinTech and financing constraints of enterprises: Evidence from China. J. Int. Financ. Mark. I 2023, 82, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H.; Qi, X. Regional financial reform and corporate green innovation—Evidence based on the establishment of China National Financial Comprehensive Reform Pilot Zones. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, L.; Schindler, M.; Tressel, T. Growth and structural reforms: A new assessment. J. Int. Econ. 2013, 89, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.B. Research, technological change and financial liberalization in South Korea. J. Macroecon. 2010, 32, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2024, 52, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Topcu, B.A.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Vo, X.V. The effect of financial development on renewable energy demand: The case of developing countries. Renew. Energy 2021, 178, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Shahzad, U.; Doğan, B. The role of environmental technology for energy demand and energy efficiency: Evidence from OECD countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Weng, S.; Chen, X.; ALHussan, F.B.; Song, M. Artificial intelligence-driven transformations in low-carbon energy structure: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2024, 136, 107719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Saadi, S.; Amin, A.S. Does CEO risk-aversion affect carbon emission? J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 1171–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl-Martinez, R.; Stephens, J.C. Toward a gender diverse workforce in the renewable energy transition. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2016, 12, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Su, C.W.; Naqvi, B.; Rizvi, S.K.A. Can Fintech development pave the way for a transition towards low-carbon economy: A global perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2022, 174, 121278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, X. Environmental regulation and energy-environmental performance—Empirical evidence from China’s non-ferrous metals industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Dong, K.; Dong, X. How does the digital economy improve high-quality energy development? The case of China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2022, 184, 121960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Yuan, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Exploring the Role of Green Finance in Advancing the Shift to Green Energy: Insights from Industrial Enterprises in China. Energy 2025, 341, 139379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, T. Measuring energy transition away from fossil fuels: A new index. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 200, 114546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Sheng, N.; Wei, X.; Su, H. Study on the spatial spillover effect and path mechanism of green finance development on China’s energy structure transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Huang, X.; Wu, X. Financial reform and innovation: Evidence from China’s financial reform pilot zones. Asian J. Technol. Inno 2023, 31, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Impact of financial reform on urban resilience: Evidence from the financial reform pilot zones in China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 94, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, H. Can green finance improve the financial performance of green enterprises in China? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 88, 1287–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fan, Z. Green finance and investment behavior of renewable energy enterprises: A case study of China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 87, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, A. Assessing the impact of green finance on financial performance in Chinese eco-friendly enterprise. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.A.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Yang, C.; Albitar, K. The impact of Fintech on corporate carbon emissions: Towards green and sustainable development. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 5776–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Mao, Z.; Ho, K.C. Effect of green financial reform and innovation pilot zones on corporate investment efficiency. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Lean, H.H. Does financial development increase energy consumption? The role of industrialization and urbanization in Tunisia. Energy Policy 2012, 40, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, A.; Zhu, M. Impact of Pilot Zones for Green Finance Reform and Innovations on green technology innovations: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing corporates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43901–43913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tan, J. Financial development, industrial structure and natural resource utilization efficiency in China. Resour. Policy 2020, 66, 101642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whited, T.M.; Zhao, J. The misallocation of finance. J. Financ. 2021, 76, 2359–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhong, Q. Does green finance policy promote green total factor productivity? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in the green finance pilot zone. Clean. Technol. Environ. 2024, 26, 2661–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, J.; Kuang, S.; Işık, C.; Su, Y.; Ju, G.L.N.G.E.; Li, S.; Xia, Z.; Muhammad, A. Exploring the impact of sustainable finance on carbon emissions: Policy implications and interactions with low-carbon energy transition from China. Resour. Policy 2024, 97, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, F.; Sanders, M. How to finance the transition to low-carbon energy in Europe? Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownbridge, M.; Kirkpatrick, C. Financial regulation in developing countries. J. Dev. Stud. 2000, 37, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Natural resources, consumer prices and financial development in China: Measures to control carbon emissions and ecological footprints. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Zhang, J.; Hou, X. Decarbonization like China: How does green finance reform and innovation enhance carbon emission efficiency? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoarde-Segot, T. Sustainable finance. A critical realist perspective. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Song, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C. Does green finance promote the green transformation of China’s manufacturing industry? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T. Does green financial policy affect debt-financing cost of heavy-polluting enterprises? An empirical evidence based on Chinese pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2022, 179, 121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, J.J.; Kamp-Roelands, N. Stakeholders expectations of an environmental management system: Some exploratory research. Eur. Account. Rev. 2000, 9, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Zhang, D. How much does financial development contribute to renewable energy growth and upgrading of energy structure in China? Energy Policy 2019, 128, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liming, H. Financing rural renewable energy: A comparison between China and India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Ummalla, M.; Apergis, N. The effect of foreign direct investment and stock market growth on clean energy use across a panel of emerging market economies. Energy Econ. 2016, 56, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Marshall, J.P. Coal, nuclear and renewable energy policies in Germany: From the 1950s to the “Energiewende”. Energy Policy 2016, 99, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešenić, T.; Vujanović, M.; Besagni, G.; Duić, N.; Markides, C.N. Clean energy technologies and energy systems for industry and power generation: Current state, recent progress and way forward. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, L. Low carbon-oriented planning of shared energy storage station for multiple integrated energy systems considering energy-carbon flow and carbon emission reduction. Energy 2024, 290, 130139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Tong, Y.; Yang, Y. Can green finance promote green technology innovation in enterprises: Empirical evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 87628–87644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; Fan, Z. An empirical analysis of the impact of digital economy on manufacturing green and low-carbon transformation under the dual-carbon background in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Wang, C.S.; He, Z.; Xing, W.W.; Wang, K. How does green finance affect energy efficiency? The role of green technology innovation and energy structure. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Lin, X.; Zhong, Y. A Pathway Exploration of Green Finance Reform Pilot Zone Policies to Promote Urban Green Development: Evidence from China. Law Econ. 2024, 3, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Impact of green finance on China’s pollution reduction and carbon efficiency: Based on the spatial panel model. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, X. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: The road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, H.; Jiang, J.; Zong, Q. Digital finance and the low-carbon energy transition (LCET) from the perspective of capital-biased technical progress. Energy Econ. 2023, 120, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, J. How to achieve a low-carbon transition in the heavy industry? A nonlinear perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Guo, B. Is the energy quota trading policy a solution to carbon inequality in China? Evidence from double machine learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 382, 125326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.; Fridley, D.; Hong, L. China’s pilot low-carbon city initiative: A comparative assessment of national goals and local plans. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 12, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Luo, T.; Gao, J. The effect of emission trading policy on carbon emission reduction: Evidence from an integrated study of pilot regions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, J. Industrial structure, technical progress and carbon intensity in China’s provinces. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2935–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luintel, K.B.; Matthews, K.; Minford, L.; Valentinyi, A.; Wang, B. The role of Provincial Government Spending Composition in growth and convergence in China. Econ. Model. 2020, 90, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kahn, M.E.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.V.D. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. The impact of financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.; Parro, F.; Valenzuela, P. Does finance alter the relation between inequality and growth? Econ. Inq. 2019, 57, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P.W.; Hammond, G.P.; Norman, J.B. Industrial energy use and carbon emissions reduction: A UK perspective. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2016, 5, 684–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezec, M.; Scholtens, B. Financing energy transformation: The role of renewable energy equity indices. Int. J. Green Energy 2017, 14, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, R.; Bose, A. An analysis of the role of finance in energy transitions. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2014, 4, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniya, G.; Tang, D. Green finance and industrial low-carbon transition: A case study on green economy policy in Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, X.; Xie, Y. Can green credit policy promote low-carbon technology innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 132061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yi, M. Impacts and mechanisms of heterogeneous environmental regulations on carbon emissions: An empirical research based on DID method. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 99, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Does financial resource misallocation inhibit the improvement of green development efficiency? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.