Abstract

To address the issues of narrow ignition limits and low combustion efficiency in ramjet combustors under low-temperature and low-pressure conditions, caused by low reactivity of liquid fuel and slow chemical reaction rates, a multi-channel gliding arc plasma excitation activation method for fuel–air mixtures is proposed. This method generates gaseous small molecules and highly active radicals. Focusing on the vaporizing flame holder of a subsonic ramjet combustor, this study investigates the fuel–air activation characteristics under different carrier gas flow rates, fuel flow rates, and numbers of discharge channels. The mechanism by which multi-channel gliding arc discharge plasma enhances fuel–air activation, ignition, and combustion performance is revealed.

1. Introduction

Under the starting lower boundary conditions (Ma = 1.0–2.5), subsonic ramjet combustors face challenging inlet parameters such as low temperature (minimum < 400 K), low pressure (minimum < 0.04 MPa), and high velocity (maximum > 0.3 Ma). These conditions lead to deteriorated fuel atomization quality, reduced evaporation and chemical reaction rates, resulting in difficult ignition and low combustion efficiency in ramjet combustors. Due to its unique thermal, chemical, and transport effects [1,2,3,4], gliding arc discharge plasma shows great application potential in fuel atomization improvement and cracking/reforming, and has been widely used in fuel cracking and reforming processes.

Over the past few decades, extensive research has been conducted domestically and internationally in the field of non-equilibrium plasma for ignition and combustion assistance. These studies have demonstrated that plasma can reduce fuel consumption [5], crack and activate fuels [6], reduce nitrogen oxide emissions [7], widen flammability limits, and shorten ignition delay times [8]. Internationally, research on plasma cracking and activation, particularly for hydrogen production via reforming, has been carried out [9,10], showing its significant potential to alter combustion characteristics [11]. Pre-treating fuels through cracking and activation before combustion is an effective method for enhancing ignition performance and promoting flame stability.

A lot of studies concentrate on plasma-assisted ignition and combustion and atomization enhancement [12,13,14,15], among which Lin [16] investigated the gliding arc plasma fuel injector for ignition and extinction improvement. To combine plasma technology with fuel atomizer, a plasma fuel nozzle was firstly proposed to assist atomization and combustion using transient DC discharge [17]. Plasma airblast fuel injection system was verified in our previous study [18,19] to be beneficial for atomization quality improvement.

Domestically, various plasma excitation methods have been employed in plasma cracking and activation research. For instance, the effects of parameters like power, electrode spacing, and gas flow rate on methane conversion rate and gaseous activation products have been investigated using microsecond and nanosecond pulsed plasma [20]. The main cracking products were hydrogen and acetylene. Using microsecond pulsed plasma for methane cracking achieved a maximum methane conversion rate of 91.2% with an energy conversion efficiency of approximately 44.3%. Dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma has been used to crack and activate n-decane, producing highly active gaseous products like hydrogen and acetylene. Increasing the excitation voltage favors higher production rates of these active gaseous products, while increasing the discharge frequency enhances the selectivity for hydrogen and acetylene in the product mixture [21,22]. The gliding arc discharge plasma, a type of non-equilibrium plasma combining the advantages of both thermal and non-thermal plasmas [23], features a relatively high gas temperature and is widely used for the cracking and reforming of hydrocarbon fuels to obtain desired products [24].

Traditional two-electrode gliding arc discharges are confined to a two-dimensional plane [25], where most fuel flows through the plasma excitation region without undergoing cracking activation, leading to low cracking rates. In contrast, gliding arcs with three-dimensional effects, such as rotating gliding arcs [26,27] or tornado gliding arcs [28], can contact more fuel–air mixtures, significantly improving fuel conversion rates and reducing energy consumption for hydrogen production. The spatial distribution of plasma and the effective contact time between the fuel–air mixture and the gliding arc are crucial for enhancing fuel–air activation effectiveness [29]. The application of plasma-assisted ignition and combustion in scramjet combustors can significantly improve ignition and flame stabilization performance [30]. Integrating multi-channel gliding arc plasma with scramjet combustors revealed that the gliding arc discharge can continuously generate new ignition kernels within the cavity recirculation zone, which aids ignition and flame stabilization while suppressing flame oscillations [31]. However, the mechanisms through which gliding arc plasma influences fuel cracking/activation remain unclear.

Previous research on gliding arc cracking activation has primarily focused on single-channel gliding arcs. Limited by discharge efficiency and arc length, the contact time between single-channel gliding arc and fuel–air mixtures remains insufficient, making it difficult to achieve qualitative improvements in cracking rates and energy conversion efficiency. While gliding arc discharge plasma has been extensively studied for cracking and activating fuels in swirl-stabilized combustors, there is a lack of exploration on fuel–air activation in subsonic ramjet combustors. The discharge configuration and cracking activation mechanisms of gliding arcs in subsonic ramjet combustors remain unclear.

To address these issues, a multi-channel gliding arc plasma method for fuel–air activation was proposed in this paper. By applying multi-channel gliding arc excitation within the recirculation zone of the flame holder, this study investigates the effects of inlet velocity, fuel flow rate, and number of discharge channels on component yield, selectivity, and cracking rate, revealing the mechanism of plasma-assisted fuel–air activation.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Facility and Ramjet Configuration

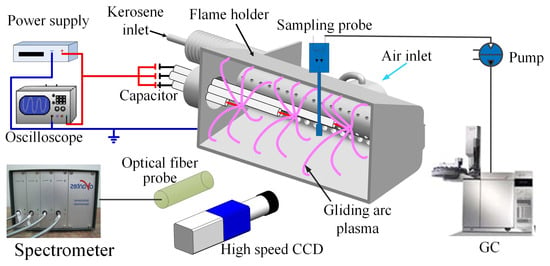

An experimental system for fuel–air activation using gliding arc plasma was established in this study to conduct activation experiments under atmospheric pressure and heated conditions, as shown in Figure 1. First, experiments on the discharge characteristics and spectral characteristics of the multi-channel gliding arc plasma were carried out. The emission spectrum of the gliding arc was measured using a four-channel (Avaspec-2048-M, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands) CCD spectrometer, with a wavelength measurement range of 200–1100 nm and a resolution of 0.1 nm. The motion and morphology of the gliding arc were captured by a high-speed CCD camera (Phantom v2512, Wayne, NJ, USA). This camera, capable of a maximum frame rate of 670,000 frames per second at its minimum resolution, was set to a resolution of 512 × 320, a frame rate of 25,000 fps, and an exposure time of 20 for the experiments.

Figure 1.

Schematic of experimental system.

In the fuel–air activation experiments, the outlet of the stabilizer was tightly connected to the sampling container to ensure that the pyrolysis and activation products sampled by the probe at the container outlet were pure and accurate. The experimental carrier gas (nitrogen) was supplied from a high-pressure nitrogen cylinder. The nitrogen passed sequentially through a D07-9E gas mass flow controller (measurement and control range: 0–300 L/min, error: ±2%) and a gas heater (rated power: 10 kW, capable of heating 1000 L/min of gas from room temperature to a maximum of 800 K) before entering the stabilizer. By adjusting the heater’s temperature controller, the intake gas temperature at the stabilizer was precisely maintained at 390 K.

The high-pressure nitrogen drove the room-temperature fuel from the fuel tank through a CX-M2 gear flow meter (measurement range: 0.5–150 mL/min, error: ±0.5%) and a kerosene flow restrictor orifice (0.5 mm diameter), after which it was injected into the stabilizer. The fuel–air mixture entered the action region of the gliding arc plasma in a spray form through two rows of distribution holes. The restrictor orifice limited the flow of kerosene in the pipeline, maintaining a nearly constant fuel injection pressure upstream of the stabilizer and ensuring a stable kerosene flow rate.

2.2. Operation Conditions

This study primarily investigates the effects of various parameters, including inlet velocity, kerosene flow rate, and number of discharge channels, on the effectiveness of fuel–air activation. The experimental operating conditions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operating conditions.

2.3. Active Species Measurement Methods

Under the influence of the gas flow, the multi-channel gliding arc plasma within the stabilizer continuously undergoes breakdown, stretching, extinction, and re-breakdown. Due to the relatively low velocity inside the stabilizer, the contact time between the fuel–air mixture and the multi-channel gliding arc is prolonged, which is conducive to thorough cracking and activation.

The products of fuel cracking and activation are filtered through an oil-gas separator and then directly introduced into a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890B, Santa Clara, CA, USA) via a sampling probe for detection of gaseous components in the activated products. The gas chromatograph is equipped with two thermal conductivity detectors (TCDs) and one flame ionization detector (FID). One TCD is used to analyze the hydrogen content in the cracking products, while the other quantitatively analyzes the contents of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, oxygen, and nitrogen. The FID enables quantitative analysis of components such as alkanes and alkenes below C4, and alkynes below C3. Before entering the gas chromatograph, the activated product components collected by the sampling probe undergo drying treatment with anhydrous calcium chloride and quartz wool to avoid the influence of moisture on the test results. Each fuel–air activation experiment under the same condition was repeated three times. The concentrations of the cracking and activation products obtained from the three tests were averaged to determine the product concentration data for that specific condition.

2.4. Evaluation Method of Fuel and Gas Activation Reaction

Several terms were introduced including the Effective Cracking Rate (ECR), the selectivity of hydrogen (SH2) in the fuel–air activation products, the selectivity S(CxHy) of other gaseous components (such as CH4, C2H6, C2H4, and C2H2, collectively assumed as CxHy), and the Production Rate (PR) of the cracking and activation components as evaluation indicators for the effectiveness of fuel–air activation.

The Effective Cracking Rate represents the proportion of kerosene that is cracked and activated into gaseous products. A higher ECR indicates that more kerosene is cracked and activated, generating more small gaseous molecules and active radicals, signifying better fuel–air activation performance. Based on the principle of hydrogen conservation, the ECR is defined as the ratio of the number of hydrogen atoms in the gaseous cracking and activation products to the number of hydrogen atoms in the initial kerosene feedstock, given by the following formula:

In the formula, MH is the molar mass of hydrogen element, that is, 1 g/mol; mH (g/s) represents the mass flow rate of hydrogen element in the initial kerosene without cracking activation; is the volume percentage of CxHy and H2 in the oil and gas activation product; (L/min) and (%) are the volume flow and volume percentage of nitrogen; Vm represents the gas molar volume, which is 22.4 L/mol under standard atmospheric conditions.

The selectivity of hydrogen and other gaseous products in oil and gas activation products is defined by the following formula, where represents the molar flow rate of hydrogen atoms in H2 or CxHy, in mol/s:

The Production Rate (PR) indicates the generation rate of each component in the gaseous products of fuel–air activation, directly characterizing the yield rate of each gaseous product component. It is defined by the following formula, where the unit of PR is mg/s, and N represents the molar mass of CxHy or H2, in g/mol:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Discharge Characteristics of Multi-Channel Gliding Arc Plasma

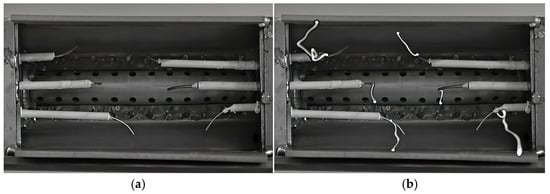

Under ambient temperature and pressure in an open environment, three high-voltage electrodes were inserted into each of the two side plates of the vaporizing flame holder. The electrodes, with a diameter of 1 mm, were insulated by ceramic tubes. The distance between the tip of each electrode and the inner contour surface of the stabilizer was approximately 5 mm. The six electrodes were distributed roughly uniformly along the spanwise direction of the stabilizer to maximize the contact area between the gliding arc and the fuel–air mixture, thereby enhancing the fuel–air activation effect. Viewed from downstream towards upstream of the stabilizer, a photograph of the six-channel gliding arc ignition and combustion assistance actuator and the discharge morphology captured by a high-speed camera are shown in Figure 2. Due to machining and assembly tolerances, it was difficult to ensure complete consistency in the six electrode gaps and tip shapes, resulting in slightly different breakdown voltages for each electrode gap.

Figure 2.

Six-channel gliding arc ignition and combustion assistance actuator. (a) Six-channel gliding arc plasma actuator for ignition/combustion. (b) Transient image of six-channel gliding arc discharge plasma.

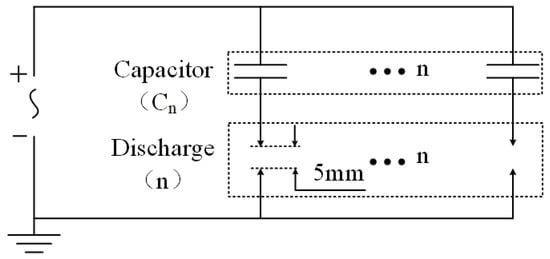

The electrical circuit for the multi-channel gliding arc discharge is shown in Figure 3. Each discharge channel was connected in series with a capacitor (the capacitance value was selected based on the number of discharge channels: 100 pF for six channels and 200 pF for three channels; no capacitor was connected in series for single-channel discharge) and then connected to the high-voltage terminal of the gliding arc power supply.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the multi-channel AC gliding arc discharge principle.

When no breakdown has occurred in any discharge channel, each discharge channel gap can be considered as a small capacitor. The capacitance of a short air gap obtained from simulations by Zhao et al. was only 4.34 pF [32]. For the multi-channel gliding arc with a single channel gap of 5 mm and an electrode diameter of about 1 mm, the calculated gap capacitance using the capacitance definition formula is approximately 1.39 pF. The capacitance Cn connected in series with the channel gap is 100 pF (or 200 pF). The impedance of a capacitor is inversely proportional to its capacitance, that is, a smaller capacitance results in a larger impedance. Therefore, the vast majority of the high voltage output from the gliding arc power supply is dropped across the channel gap itself. The presence of the series capacitor Cn does not increase the circuit’s requirement for the gliding arc output voltage.

When one of the gaps (assumed to be n1) breaks down and forms a discharge channel, n1 can be regarded as a resistor. The circuit begins to charge capacitor C1 (the capacitor in series with gap n1). When the voltage across C1 increases sufficiently to cause the next discharge gap n2 to conduct, gap n2 breaks down, forming the second discharge channel, and so on. It is important to note that this multi-channel AC gliding arc discharge circuit operates on a different principle than traditional DC multi-channel discharges [33]. The breakdown sequence of the multiple discharge channels in this circuit has a certain degree of randomness, meaning each discharge gap has a specific breakdown delay time. This delay time depends on parameters such as the rise time of the power supply’s output voltage, the precise value of capacitor Cn, the impedance matching between the power supply and the load circuit, and the distance between the gap awaiting breakdown and already broken-down gaps. A steeper voltage rise time, a smaller capacitance Cn in series with the discharge gap n, and a smaller distance from an already broken-down gap all contribute to a shorter breakdown delay time for the respective discharge gap. A broken-down discharge channel ionizes the surrounding air, generating many excited particles like electrons. The closer another gap is to this active channel, the stronger the electric field and the higher the electron density in its vicinity, making it easier for the unbroken gap to attract surrounding electrons and facilitate its own breakdown. This breakdown mode, aided by attracting electrons from nearby discharge channels, is also referred to as ‘induced’ breakdown discharge. Importantly, in this multi-channel AC gliding arc discharge system, the discharge channels can mutually promote breakdown, yet the failure of one specific gap to break down does not cause the entire system to fail; other channels can continue discharging unaffected. This characteristic gives this multi-channel gliding arc discharge structure high reliability and practical value in real-world applications.

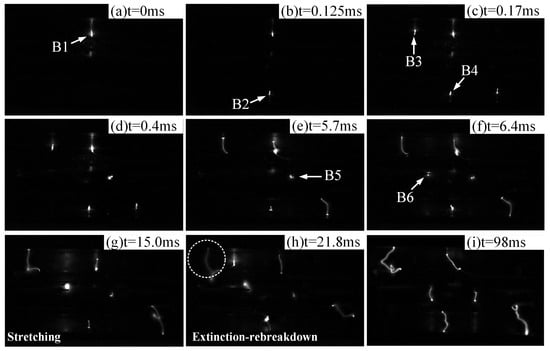

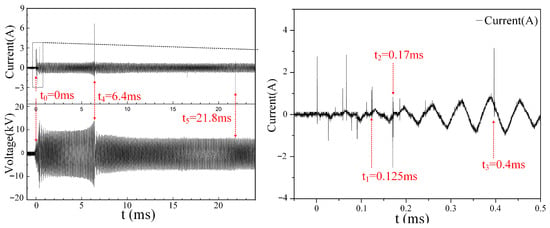

When the inlet flow velocity is V = 50 m/s, the discharge process of the six-channel gliding arc and the corresponding synchronized current and voltage waveforms are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively. At time t0 = 0 ms, the first discharge gap breaks down, denoted as B1. At t1 = 0.125 ms, the second discharge gap (B2) breaks down. The third and fourth discharge gaps (B3 and B4) break down simultaneously at t2 = 0.17 ms. At t3 = 0.4 ms, the fifth discharge gap (B5) breaks down. Subsequently, driven by the airflow, the five arc channels begin to slide along the inner contour surface of the stabilizer. At t4 = 6.4 ms, the final discharge gap (B6) breaks down, ultimately forming the six-channel gliding arc discharge plasma. The six arc channels continuously stretch under the sustained action of the airflow, increasing their individual arc lengths. This increase in arc length raises the impedance of each channel. A higher impedance requires a higher current to maintain the arc, known as the arc maintenance current. When the power supply’s output current falls below this maintenance current, the arc channel extinguishes. As shown in Figure 4h, after the initial breakdown of gap B1, the arc continuously stretches, reaching its maximum length at t5 = 21.8 ms before extinguishing. It then re-breaks down at the most susceptible location (typically the nearest point) and continues its motion cycle. Similarly, arcs in other channels repeat the typical gliding arc motion process of breakdown–stretching–extinction–rebreakdown. The motion processes of the arcs in each channel are independent of each other. It should be noted that in the designed multi-channel gliding arc ignition/combustion actuator, the electrodes of each discharge channel are curved upstream, forming a structure somewhat similar to the traditional ‘knife-type’ gliding arc between themselves and the upper and lower plates of the vaporizing stabilizer. However, unlike the ‘knife-type’ design, one electrode (the inner surface of the stabilizer plate) is a flat plane. This allows the gliding arc to slide simultaneously in both the streamwise and spanwise directions, cleverly utilizing the complex three-dimensional flow field characteristics inside the stabilizer. This design increases the probability and duration of contact between the gliding arc and the fuel–air mixture, as illustrated in Figure 4i.

Figure 4.

Dynamic process of multichannel gliding arc plasma discharge (V = 50 m/s).

Figure 5.

Synchronized current/voltage waveforms of multi-channel gliding arc discharge (V = 50 m/s).

Energy Density (ED, unit J/m) was defined to describe the discharge energy injected by the multi-channel gliding arc into the fuel–air mixture:

where P represents the average discharge power (unit: W), and V represents the inlet flow velocity (unit: m/s).

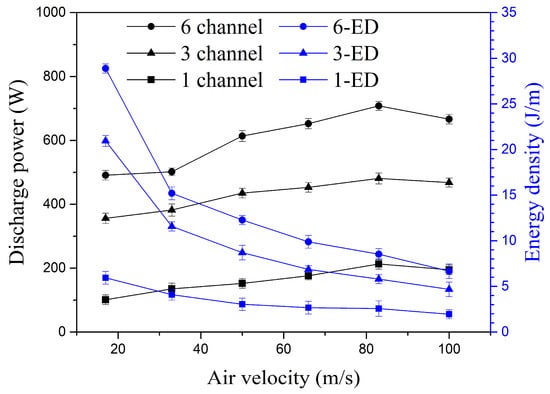

The variation in the average discharge power and energy density of the multi-channel gliding arc discharge with the inlet flow velocity is shown in Figure 6. For the six-channel gliding arc discharge, as the flow velocity increases from 17 m/s to 33 m/s, the average discharge power increases slightly from 491 W to 501.7 W (an increase of only about 2.2%), while the energy density decreases from 28.88 J/m to 15.2 J/m (a decrease of about 47.37%). This decrease in energy density is unfavorable for fuel cracking and activation. As the inlet velocity increases from 33 m/s to 83 m/s, the average discharge power for the six-channel gliding arc increases from 501.7 W to 708 W. Subsequently, as the velocity continues to increase to 100 m/s, the average discharge power begins to decrease slowly because the high flow velocity makes it difficult for the arcs to maintain their original length. The energy density gradually decreases with increasing inlet velocity, and the rate of decrease slows down. As the inlet velocity increases from 50 m/s to 83 m/s, the energy density decreases from 12.12 J/m to 8.59 J/m, a reduction of about 29.1%. Under the same conditions, due to the reduced number of arc channels, the total arc length and total impedance decrease. Consequently, the average discharge power of the three-channel gliding arc is smaller than that of the six-channel configuration, and its energy density is reduced by about 28.1% compared to the six-channel case at the same velocity. For the single-channel gliding arc, due to the further reduction in the number of arc channels, total length, and total impedance, its average discharge power is only about 40% of that of the three-channel gliding arc, and its energy density is significantly lower, reduced to about 34.1% of the three-channel gliding arc discharge. The multi-channel gliding arc, with its multiple discharge channels and three-dimensional discharge effect, significantly increases the total arc length of the gliding arc discharge. At higher inlet velocities, the swinging and twisting of the arc channels become more intense, consuming more energy. Although the energy density of the three-channel gliding arc is slightly less than that of the six-channel one, compared to the single-channel gliding arc, both the total arc discharge power and the energy density are significantly increased. The following sections will analyze the spectral characteristics and fuel cracking/activation characteristics for single-channel, three-channel, and six-channel gliding arc discharges.

Figure 6.

Variation in average discharge power and energy density with inlet velocity.

3.2. Emission Spectrum Characteristics of Multi-Channel Gliding Arc Plasma

In the mechanism of plasma-assisted ignition and combustion, the large quantity of excited state particles generated during the discharge process of gliding arc plasma is key to plasma fuel–air activation, alteration of reaction pathways, ignition promotion, and combustion enhancement. Therefore, investigating the distribution characteristics of active particles (such as vibrational temperature and rotational temperature) during discharge is essential for understanding the mechanism of plasma-assisted ignition and combustion and exploring the mechanism of plasma cracking and activation of kerosene.

Since the multi-channel gliding arc occupies almost the entire internal space of the stabilizer, when measuring the optical emission spectroscopy (OES) signals, the optical fiber probe was fixed to a three-axis translation stage. Six measurement points were uniformly selected along the gliding arc discharge region inside the stabilizer. Under the same conditions, each point was measured five times, and the signals from all points were averaged to obtain the spectral characteristics for that condition.

3.2.1. Spectral Intensity Analysis of Active Particles

A four-channel CCD spectrometer was used to study the spectral characteristics of the multi-channel gliding arc discharging in air at room temperature and atmospheric pressure (without kerosene). The emission spectral intensity plot of the gliding arc discharge in the 200–450 nm wavelength range was obtained.

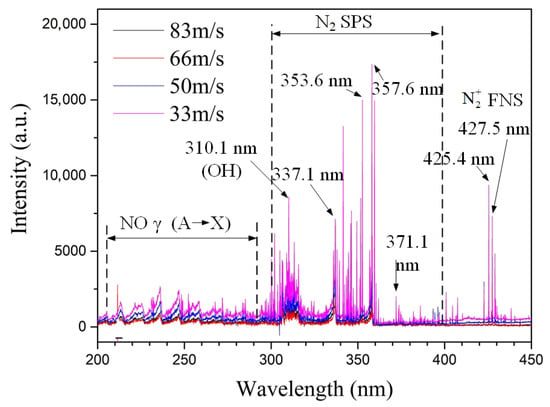

The effect of different inlet velocities on the spectral intensity is shown in Figure 7. The characteristic bands of the N2 Second Positive System (SPS, ), the First Negative System (FNS, ), and NO () are clearly identifiable. Among them, the peak spectral intensities at 310.1 nm, 337.1 nm, 353.6 nm, and 357.6 nm prove the presence of excited states of and . The peak bands at 425.4 nm and 427.5 nm prove the presence of excited states of . The line at 310.1 nm indicates the OH radical, presumably influenced by trace water vapor in the air. Overall, the spectral line intensities in the 200–450 nm wavelength range weaken as the inlet velocity increases. The reason is that the total arc length of the gliding arc decreases with increasing flow velocity, reducing the plasma interaction region between the arc and the gas, which is unfavorable for the generation of excited state particles.

Figure 7.

Effect of inlet velocity on spectral intensity (Spectral signal from a single channel in a three-channel gliding arc).

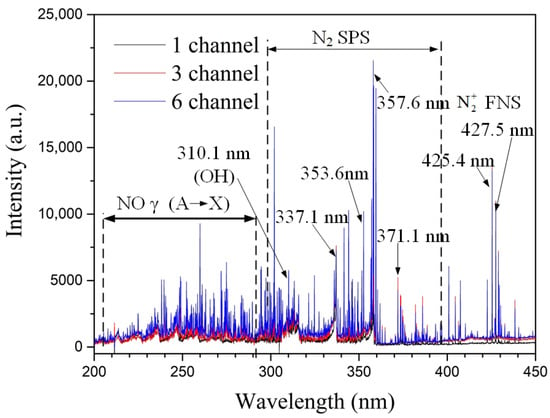

Figure 8 shows the effect of the number of discharge channels on the spectral intensity at an inlet velocity of 50 m/s. The distribution characteristics of the various spectral lines are very similar to those in Figure 7. In contrast, as the number of discharge channels increases, the intensity of the characteristic spectral lines enhances. There are two main reasons: firstly, the increase in the number of channels increases the total arc length of the discharge channels, expanding the interaction area between the arc and the air, ionizing more electrons, and promoting the generation of more excited state particles; secondly, the increase in the number of channels increases the total discharge power of the gliding arc (as known from the electrical characteristics analysis), which favors the generation of more excited state particles.

Figure 8.

Effect of the number of discharge channels on spectral intensity (Inlet velocity V = 50 m/s).

The high-energy electrons generated during the gliding arc discharge process collide with nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the air through collision decomposition reactions, producing highly chemically active energetic excited particles, while simultaneously causing a sharp rise in the surrounding gas temperature. The main reaction pathways for gliding arc discharge in an atmospheric air environment are as follows [34]:

Vibration-rotation reactions of N2(ν):

- ➀

- Collision decomposition reactions between N2, O2, and high-energy electrons:

- ➁

- Quenching reactions between excited N2 and O2:

- ➂

- Ion-electron recombination reactions:

The discharge of the gliding arc inside the stabilizer creates a non-uniform electric field. For a qualitative analysis of the changes in the electric field strength of the multi-channel gliding arc, the internal discharge can be considered as a uniform electric field, where the electric field strength E = U/d, related to the voltage and the distance along the field direction. Compared to traditional single-channel gliding arc discharge, the multi-channel gliding arc discharge structure generates multiple discharge channels within the same spatial volume (inside the stabilizer). Since the electric field strength at any point in space is the vector sum of the field strengths produced by all charges at that point (that is, the superposition principle of electric fields), even if the direction of the electric field force on a point in space from various directions changes constantly, the magnitude of the vector sum of the electric field strength at that point increases significantly. This is conducive to inducing more high-energy electrons to collide and decompose nitrogen and oxygen molecules, increasing the relative concentration of upper-state particles. This is manifested in the band intensities as a significant increase in the intensity values of the various characteristic spectral systems.

3.2.2. Vibration Temperature

Vibrationally excited particles play a key role in the plasma cracking process [35]. The higher the vibrational temperature, the higher the activity of the particles. The vibrational temperature of the multi-channel gliding arc discharge plasma based on the N2 Second Positive System (SPS, ) band lines were calculated using the Boltzmann plot method.

The intensity of a spectral band in atomic emission spectroscopy is proportional to the number of particles in the upper state:

where and represent the vibrational quantum numbers of the upper and lower states, respectively. represents the spectral line intensity for the transition from energy level to , is the number of particles in the upper vibrational level, h and c represent Planck’s constant () and the speed of light (), respectively, and and represent the wavelength and the transition probability of the band, respectively.

From quantum theory, the vibrational energy of the molecular upper state can be calculated by

For a plasma in local thermodynamic equilibrium [36,37], the upper state population follows a Boltzmann distribution:

From the above three equations, we obtain

Here, represents the total number of particles, represents the vibrational temperature, and C is a constant. A plot of versus is generated, and the vibrational temperature is calculated from the slope of the fitted line. To improve accuracy, two sequence band groups of the N2 SPS were selected: −1 (0–1, 1–2) and −2 (1–3, 2–4). The vibrational temperature was calculated for each group and then arithmetically averaged to obtain the N2 vibrational temperature for the corresponding condition.

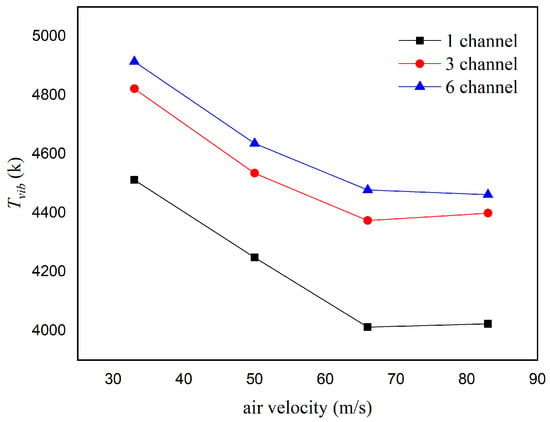

The calculated variations in the N2 vibrational temperature during gliding arc discharge under different inlet velocities and numbers of discharge channels are shown in Figure 9. When the inlet velocity increased from 33 m/s to 50 m/s, the vibrational temperature of the single-channel gliding arc discharge decreased from 4510 K to 4004 K (a decrease of about 11.22%), the vibrational temperature of the three-channel gliding arc discharge decreased from 4822 K to 4374 K (a decrease of about 9.3%), and the vibrational temperature of the six-channel gliding arc discharge decreased from 4914 K to 4472 K (a decrease of about 9.0%). It is evident that increasing the number of discharge channels slows down the rate of decrease in the vibrational temperature with increasing inlet velocity. The previous analysis showed that increasing the inlet velocity leads to a decrease in the intensity of the characteristic spectral lines. According to the vibrational temperature fitting formula, the weakening spectral intensity leads to a lower vibrational temperature.

Figure 9.

Effect of different inlet velocities and numbers of discharge channels on the vibrational temperature.

When the inlet velocity further increased from 66 m/s to 83 m/s, the vibrational temperature of the gliding arc discharge changed very little. This is due to the combined effect of two factors: on one hand, the increase in gliding arc discharge power favors the generation of more high-energy electrons; on the other hand, the shortened stretching length of the gliding arc reduces the interaction region between the arc and the gas, which is unfavorable for generating more excited state particles. At an inlet velocity of 83 m/s, the vibrational temperature of the single-channel gliding arc discharge was 4023 K, while the vibrational temperatures of the six-channel and three-channel gliding arc discharges were 4462 K and 4399 K, respectively, representing increases of 10.9% and 9.4%. The increase in the number of discharge channels effectively expands the contact area between the arc and the gas and the total arc length, increases the discharge power, promotes the generation of more excited state particles, and is beneficial for the plasma cracking and activation of the fuel–air mixture.

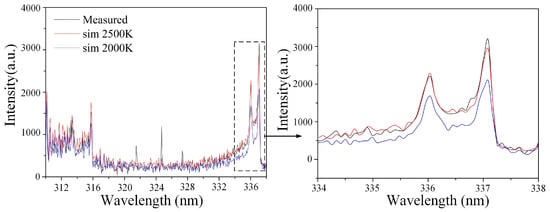

3.2.3. Rotation Temperature

The higher the gas temperature, the better the fuel atomization quality and evaporation rate, and the more readily chemical reactions proceed. Since the rotation-translation relaxation time is extremely short, the rotational temperature of gas molecules in the rotational state is often approximated as the gas temperature around the arc [38]. By setting different rotational temperatures in the plasma spectrum fitting software SPECAIR 3.0 [39], the fitted spectrum (N2 SPS: 310–338 nm) achieved a high degree of overlap with the experimentally collected spectrum. The set rotational temperature was then considered approximately equal to the N2 rotational temperature during the plasma discharge process. Under the same conditions, spectral data were collected and recorded three times, the rotational temperature was fitted for each, and the average was taken as the rotational temperature for that condition. As shown in Figure 10, for single-channel gliding arc discharge at an inlet velocity of 50 m/s, by comparing the fitted curves under different set rotational temperatures with the experimental curve, the highest degree of overlap between the calculated fitted curve and the experimental curve was found within the range of 2000–2500 K. Therefore, the rotational temperature under this condition is determined to be 2000–2500 K.

Figure 10.

Comparison between fitted and experimental curves under different rotational temperatures (Single-channel gliding arc, Inlet velocity V = 50 m/s).

Change the inlet velocity and fitting the emission spectra for different velocities, it was found that the N2 rotational temperature consistently fell within the range of 2000–2500 K, indicating that the inlet velocity has little effect on the rotational temperature. Keeping the inlet velocity at 50 m/s and only changing the number of discharge channels, the N2 rotational temperature during gliding arc discharge was fitted for different numbers of channels. The N2 rotational temperature ranges for both three-channel and six-channel gliding arc discharges were between 2500 K and 3000 K. Due to the larger discharge volume (almost covering the entire internal space of the stabilizer) and longer arc heating region in the multi-channel gliding arc, the contact time and contact area between the mixture and the arc are significantly increased, thereby raising the N2 rotational temperature. The increase in rotational temperature is beneficial for increasing the gas temperature around the arc, promoting improved fuel atomization, and enhancing the chemical reaction rate.

3.3. Effect of Inlet Velocity

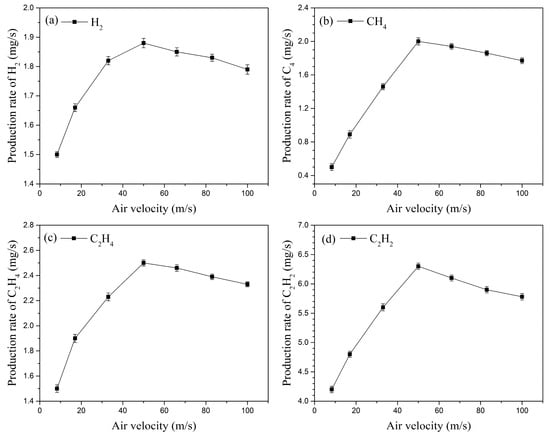

3.3.1. Production Rate of Activated Components

Plasma fuel–air activation experiments were conducted with a fixed kerosene volumetric flow rate of 29 mL/min and an applied three-channel gliding arc discharge, while the inlet velocity was adjusted from 8.3 m/s to 100 m/s (corresponding to an inlet flow rate range of 25 L/min to 300 L/min). Figure 11 shows the variation in the production rates (PR) of the four main cracking products (H2, CH4, C2H4, and C2H2) with the inlet velocity. As the inlet velocity increases, the production rates of these four main components first increase and then gradually decrease, reaching their maximum values at an inlet velocity of 50 m/s. The production rate of H2 increases from 1.5 mg/s at 8.3 m/s to 1.88 mg/s at 50 m/s. When the inlet velocity reaches 100 m/s, the H2 production rate decreases to 1.79 mg/s.

Figure 11.

Effect of inlet velocity on the production rates of the main cracking products.

Initially, as the inlet velocity increases, the total discharge power of the three-channel gliding arc also increases (as indicated by the electrical characteristics analysis). This enhances collision decomposition reactions between electrons and N2 and O2, generating more excited state particles. These excited particles then undergo reactions like collision dissociation with large kerosene molecules, producing more small gaseous molecules (e.g., H2, CH4, C2H4, and C2H2) and highly chemically active radicals. However, when the inlet velocity increases beyond a certain value (50 m/s in this experiment), the total arc discharge power ceases to increase due to limitations in the power supply’s output and discharge efficiency. Furthermore, higher inlet velocities lead to a shorter gliding arc length and a reduced plasma interaction region between the arc and the air, which is unfavorable for the generation of excited state particles (consistent with the earlier conclusion of decreased characteristic spectral line intensities at higher velocities). Consequently, the production rates of the cracking products begin to decline.

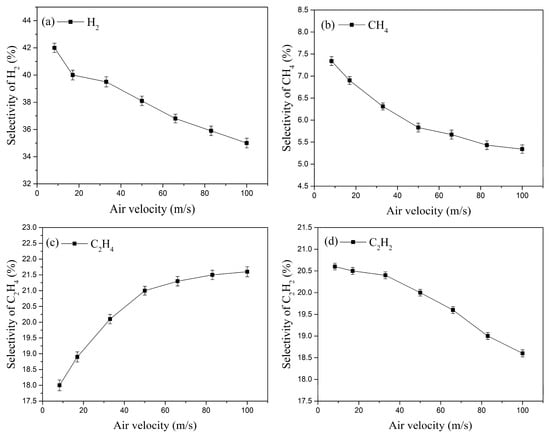

3.3.2. Components Selectivity

Different components in the cracking products have varying chemical reaction rates and laminar flame speeds, leading to different degrees of improvement in ignition and combustion performance. The presence of H2 and C2H2 can significantly reduce the minimum ignition energy, which is beneficial for shortening the ignition delay time and improving the ignition performance of the ramjet combustor. Although CH4 has a simple structure, its reactivity is relatively low compared to H2 and C2H2, resulting in a less pronounced effect on improving ignition performance. Studies have shown that H2 and C2H4 can significantly shorten the ignition delay time of kerosene, with C2H4 exhibiting the most prominent capability for enhancing kerosene ignition performance [40].

The variation in the selectivity of the four main cracking products with inlet velocity is shown in Figure 12. Under the same conditions, the selectivity of H2 is the highest, while that of CH4 is the lowest. As the inlet velocity increases, the selectivity of H2, CH4, and C2H2 decreases, whereas the selectivity of C2H4 increases. The increased inlet velocity promotes heat dissipation, causing a slight decrease in the gas temperature within the plasma interaction region. This lower temperature reduces the cracking reaction rate, leading to decreased selectivity for H2, CH4, and C2H2. Ethylene (C2H4) is produced by direct cleavage of the β-C-H bond and dehydrogenation of larger alkane molecules. Meanwhile, both H2 and C2H2 are generated by consuming ethyl radicals. The decreased selectivity for H2 and C2H2 implies that more ethyl radicals are available for direct conversion to C2H4, thereby promoting the rise in C2H4 selectivity.

Figure 12.

Effect of inlet velocity on the selectivity of the four main cracking products.

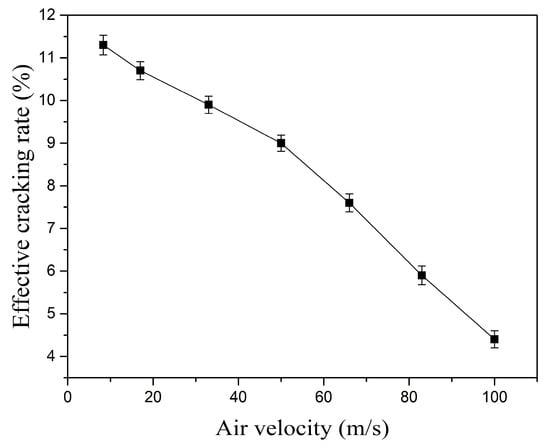

3.3.3. Effective Cracking Rate

Keeping the kerosene flow rate constant at 29 mL/min, the variation in the Effective Cracking Rate (ECR) for the three-channel gliding arc discharge with inlet velocity is shown in Figure 13. As the inlet velocity increases, the ECR continuously decreases. At 8 m/s, the ECR is 11.3%. When the inlet velocity increases to 50 m/s and 100 m/s, the ECR decreases to 9% and 4.4%, respectively.

Figure 13.

Effect of inlet velocity on the Effective Cracking Rate.

The increase in inlet velocity primarily brings about two effects: a physical effect and a chemical effect. Physical Effect: Increasing the inlet velocity can effectively reduce the kerosene droplet size inside the vaporizing flame holder, improving kerosene atomization quality. This is beneficial for collisions between kerosene molecules and excited state particles. Chemical Effect: As revealed by the earlier analysis of multi-channel gliding arc discharge characteristics, increasing the inlet velocity increases the total discharge power of the three-channel gliding arc but significantly reduces the energy density. Moreover, the previous analysis of spectral characteristics indicated that higher inlet velocities are unfavorable for the generation of excited state particles. This suppresses the cracking activation reactions between excited particles and large kerosene molecules, hindering the breaking of chemical bonds such as C-C and C-H bonds, and ultimately reduces the ECR. In this case, the influence of the chemical effect dominates.

3.4. Effect of Fuel Flow Rate

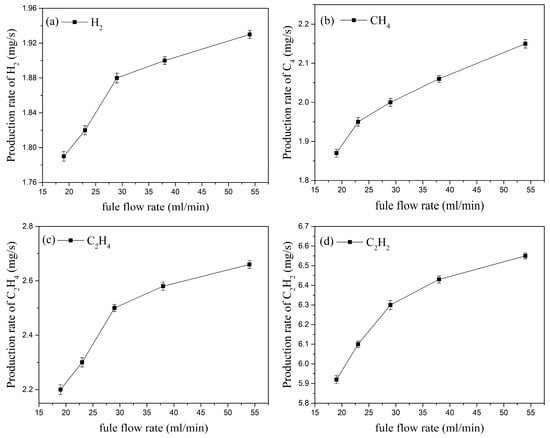

3.4.1. Production Rate of Activated Components

With the inlet velocity of nitrogen fixed at 50 m/s (corresponding to an inlet flow rate of 150 L/min) and a three-channel gliding arc discharge applied, the kerosene flow rate was adjusted from 19 mL/min to 54 mL/min. The resulting variations in the production rates of the activated components are shown in Figure 14. The production rates of H2, CH4, C2H4, and C2H2 all increase with the increasing kerosene flow rate. Regarding H2 and C2H4, when the kerosene flow rate increases from 19 mL/min to 54 mL/min, the H2 production rate increases from 1.79 mg/s to 1.93 mg/s (an increase of about 7.82%), and the C2H4 production rate increases from 2.2 mg/s to 2.66 mg/s (an increase of about 20.9%). Further increasing the kerosene flow rate causes the rates of increase for H2 and C2H4 production to slow down. The experimental system increases the kerosene flow rate by raising the fuel supply pressure. A higher supply pressure improves fuel atomization quality, increases the effective contact area between kerosene molecules and excited state particles, and thus enhances the production rates of the activated components.

Figure 14.

Effect of kerosene flow rate on the production rates of the cracking products.

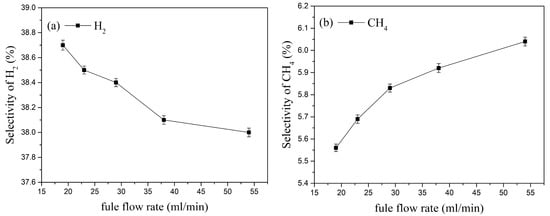

3.4.2. Components Selectivity

The selectivity of the cracking products under different kerosene flow rates is shown in Figure 15. As the kerosene flow rate increases, the selectivity of H2, CH4, and C2H2 decreases, while the selectivity of C2H4 increases. When the kerosene flow rate increases from 19 mL/min to 54 mL/min, the selectivity of H2 decreases from 38.7% to 38% (a decrease of about 1.84%); the selectivity of C2H4 increases from 20.6% to 21.5% (an increase of about 4.37%); similarly, the selectivity of C2H2 increases by about 5.3%, and the selectivity of CH4 increases from 5.56% to 6.04% (an increase of about 8.63%). This indicates that at the same inlet velocity, increasing the kerosene flow rate raises the fuel-to-air ratio inside the activation actuator, resulting in higher selectivity for C2H4 and CH4.

Figure 15.

Effect of kerosene flow rate on the selectivity of the main cracking products.

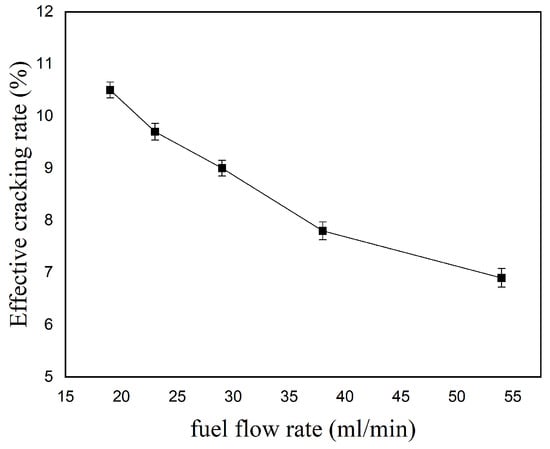

3.4.3. Effective Cracking Rate

The variation in the Effective Cracking Rate (ECR) with kerosene flow rate under a constant inlet velocity (V = 50 m/s) is shown in Figure 16. As the kerosene flow rate increases, the number of kerosene molecules increases. However, the number of high-energy electrons generated by the gliding arc discharge is limited. Consequently, a greater proportion of kerosene molecules leave the plasma interaction region without undergoing collision reactions with high-energy electrons, leading to a decrease in the ECR.

Figure 16.

Effect of kerosene flow rate on the Effective Cracking Rate.

3.5. Effect of the Number of Discharge Channels

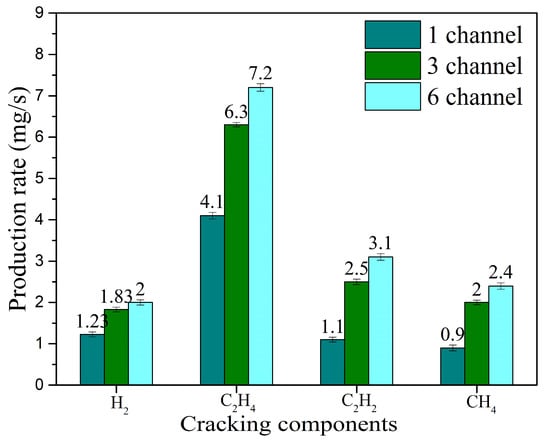

3.5.1. Production Rate of Activated Components

With the nitrogen inlet velocity fixed at 50 m/s (corresponding to an inlet flow rate of 150 L/min) and the kerosene flow rate at 29 mL/min, gliding arc plasma fuel–air activation experiments were conducted by varying the number of discharge channels (single-channel, three-channel, and six-channel). The production rates of the four main cracking products—H2, CH4, C2H4, and C2H2—are shown in Figure 17. Compared to single-channel discharge, the H2 production rate for the three-channel gliding arc increases from 1.23 mg/s to 1.83 mg/s (an increase of about 48.8%), and the C2H4 production rate increases from 4.1 mg/s to 6.3 mg/s (an increase of about 53.7%). Compared to the three-channel case, the six-channel gliding arc increases the H2 and C2H4 production rates by only 9.3% and 14.3%, respectively. Increasing the number of discharge channels boosts the total discharge power, which promotes collisions between high-energy electrons and kerosene molecules, enhances the cracking activation reactions, and improves the production rates of the activated components. When the number of channels increases from three to six, the rate of increase in total discharge power slows down (as indicated by the earlier electrical characteristics analysis), thus the enhancement effect on the production rates of the cracking products diminishes.

Figure 17.

Effect of the number of discharge channels on the production rates of cracking products.

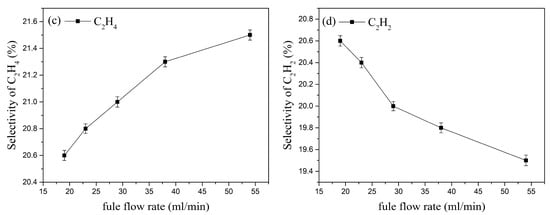

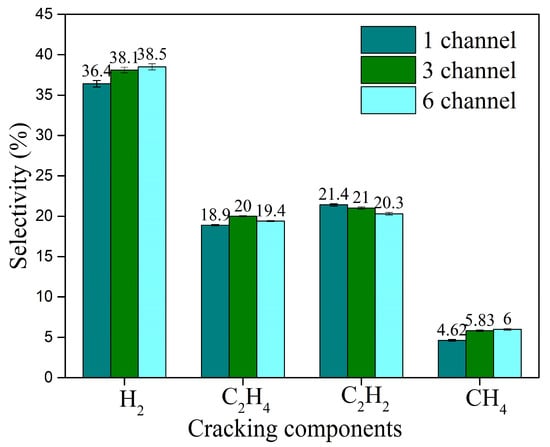

3.5.2. Components Selectivity

The effect of the number of discharge channels on the selectivity of the cracking products is shown in Figure 18. As the number of discharge channels increases, the selectivity of H2 and CH4 among the cracking products increases, while the selectivity of C2H2 decreases. Compared to single-channel discharge, the selectivity of H2 and C2H4 for three-channel discharge increases by about 4.7% and 5.8%, respectively. When increasing further from three-channel to six-channel gliding arc discharge, the trends for these two selectivities differ: the selectivity of H2 increases by about 1%, while the selectivity of C2H4 decreases from 20% to 19.4% (a decrease of about 3%). This indicates that for the highly active components H2 and C2H4, which are more effective for ignition and combustion assistance, the three-channel gliding arc discharge offers a better compromise in selectivity, making it easier to achieve benefits in ignition and combustion enhancement.

Figure 18.

Effect of the number of discharge channels on the selectivity of the cracking products.

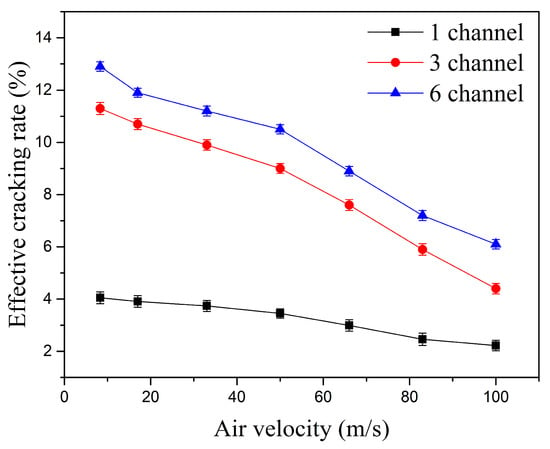

3.5.3. Effective Cracking Rate

The effect of the number of discharge channels on the Effective Cracking Rate (ECR) is shown in Figure 19. Under the same inlet velocity condition, increasing the number of discharge channels significantly improves the ECR. At an inlet velocity of 50 m/s, the ECR for single-channel, three-channel, and six-channel gliding arc discharges are 3.4%, 9.1%, and 10.5%, respectively. The three-channel gliding arc increases the ECR by about 168% compared to the single-channel case, while the six-channel gliding arc further increases the ECR by about 15.4% compared to the three-channel case. Multi-channel gliding arc discharge increases the total discharge power. Moreover, the significant increase in total arc length associated with multiple channels markedly expands the plasma interaction region, allowing the gliding arc plasma to occupy almost the entire flame holder. This intensifies collisions between high-energy electrons and kerosene molecules, enhances the kerosene cracking activation reactions, and substantially improves the effective cracking rate of kerosene molecules.

Figure 19.

Effect of the number of discharge channels on the Effective Cracking Rate (Kerosene flow rate: 50 mL/min).

Compared to the traditional single-channel gliding arc, the multi-channel gliding arc significantly increases the total arc length. The expanded plasma interaction region between the arc and the gas ionizes more electrons, promoting the generation of a greater number of excited species. The relatively high local gas temperature of the gliding arc discharge effectively promotes kerosene atomization, reducing droplet size and thereby increasing the contact area between high-energy electrons and gas molecules/large kerosene molecules. On the other hand, it enhances kerosene reactivity by raising its temperature, which is conducive to the breaking of C-C and C-H bonds within kerosene molecules, thereby increasing the cracking and activation reaction rate.

Under the action of multi-channel gliding arc plasma, the production rates of cracking products and the effective cracking rate are improved. The enhanced selectivity for H2 and C2H4 contributes to improving the ignition performance of the flame holder within the combustion chamber. The small gaseous molecules, such as H2, C2H4, and C2H2, generated during the fuel–air activation process facilitate more complete combustion of kerosene, thereby promoting highly efficient combustion.

4. Conclusions

Based on the vaporizing flame holder of a ramjet combustor, a multi-channel gliding arc plasma ignition and combustion assistance actuator was proposed in this paper. Through multiple experimental techniques including discharge characteristics analysis, optical emission spectroscopy diagnostics, and detection of fuel–air activation products, the emission spectral characteristics and fuel–air activation characteristics of multi-channel gliding arc plasma under atmospheric pressure were investigated. The vibrational temperature and rotational temperature of the multi-channel gliding arc plasma were obtained, along with the influence patterns of different inlet velocities, fuel flow rates, and numbers of discharge channels on the fuel–air activation effectiveness, including the production rate and selectivity of activated components and the effective cracking rate. The mechanism by which multi-channel gliding arc plasma cracking enhances ignition and combustion performance was revealed. Multi-channel gliding arc plasma cracking technology is expected to be applied in future scramjet engines and combined cycle engines, significantly improving the ignition performance and stable operating boundaries of the engines. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The multi-channel gliding arc utilizes the complex three-dimensional flow field characteristics inside the vaporizing flame holder, gliding simultaneously in both the streamwise and spanwise directions within the stabilizer. This effectively increases the discharge volume (almost covering the entire internal space of the stabilizer) and the contact area between the gas mixture and the arcs, thereby increasing the residence time of the fuel–air mixture within the gliding arc plasma interaction zone.

- (2)

- Increasing the number of discharge channels in the multi-channel gliding arc can increase the N2 vibrational temperature and rotational temperature, and to some extent, slow down the rate of decrease of the vibrational temperature with increasing inlet velocity. The N2 rotational temperature for single-channel gliding arc discharge ranges from 2000 to 2500 K, while for three-channel and six-channel gliding arc discharges, it can be elevated to 2500–3000 K. The increase in rotational temperature effectively raises the gas temperature around the arcs, promoting improved fuel atomization quality and chemical reactivity, which is beneficial for increasing the cracking and activation reaction rate.

- (3)

- The multi-channel gliding arc generates high-energy electrons through discharge, which undergo collision-induced cracking reactions with nitrogen molecules and kerosene molecules, breaking the C-C and C-H bonds in the long-chain alkane kerosene molecules. This produces highly active gaseous species such as H2, C2H4, and C2H2, which facilitate more complete combustion of kerosene and promote highly efficient combustion. Increasing the number of discharge channels enhances the production rates of the cracking products. For the highly active components H2 and C2H4, which are particularly effective for ignition and combustion assistance, the three-channel gliding arc discharge offers a favorable compromise in selectivity, making it easier to achieve benefits in ignition and combustion enhancement.

- (4)

- Compared to single-channel gliding arc discharge, the three-channel gliding arc can increase the effective cracking rate by approximately 168%, while the six-channel gliding arc can further increase the effective cracking rate by about 15.4% compared to the three-channel baseline. Multi-channel gliding arc discharge increases the total discharge power. Furthermore, the substantial increase in total arc length associated with multiple channels significantly expands the gliding arc plasma interaction region, allowing the plasma to occupy almost the entire flame holder. This intensifies collisions between high-energy electrons and kerosene molecules, enhances the kerosene cracking activation reactions, and substantially improves the effective cracking rate of kerosene molecules.

- (5)

- In this study, experimental validation of multi-channel gliding arc plasma cracking characteristics was conducted under typical inflow conditions of a subsonic ramjet combustor. However, the performance and effectiveness of this technology under supersonic ramjet combustor inflow conditions remain to be verified in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; methodology, S.H.; validation, S.Y. and D.J.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H.; resources, Y.W. and Y.L.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.Y. and D.J.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W. and Y.L.; funding acquisition, S.H. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 52207179 and 52488101).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ju, Y.; Sun, W. Plasma assisted combustion: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Combust. Flame 2015, 162, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Sun, W. Plasma assisted combustion: Dynamics and chemistry. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2015, 48, 21–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikovskiy, A.; Aleksandrov, N. Plasma-assisted ignition and combustion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 39, 61–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikovskaia, S.M. Plasma-assisted ignition and combustion: Nanosecond discharges and development of kinetic mechanisms. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 353001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Moon, A.; Kaneko, M. Development of microwave-enhanced spark-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Appl. Opt. 2010, 49, C95–C100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Xiao, M.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.; Yan, H.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Hydrogen production by steam-oxidative reforming of bio-ethanol assisted by Laval nozzle arc discharge. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 8318–8329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Mo, J.; Tang, J.; Huang, D.; Mo, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, S.; Chen, Z. Plasma reforming of bioethanol for hydrogen rich gas production. Appl. Energy 2014, 133, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Song, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Li, Y. Experimental investigation of multichannel plasma igniter in a supersonic model combustor. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2018, 99, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Huang, X.; Cheng, D.; Zhan, X. Hydrogen production from alcohols and ethers via cold plasma: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 9036–9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruj, B.; Ghosh, S. Technological aspects for thermal plasma treatment of municipal solid waste-A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 126, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Jin, T.; Yu, J.; Zeng, H. Current investigation progress of plasma-assisted ignition and combustion. J. Aerosp. Power 2016, 31, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombrello, T.; Qin, X.; Ju, Y.; Gutsol, A.; Fridman, A.; Carter, C. Combustion Enhancement via Stabilized Piecewise Nonequilibrium Gliding Arc Plasma Discharge. AIAA J. 2006, 44, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, I.B.; Matveeva, S. Non-equilibrium plasma igniters and pilots for aerospace application. In Proceedings of the 43rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 10–13 January 2005; AIAA paper. p. 1191. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, S.; Pilla, G.; Lacoste, D.A.; Scouflaire, P.; Ducruix, S.; Laux, C.O.; Veynante, D. Influence of nanosecond repetitively pulsed discharges on the stability of a swirled propane/air burner representative of an aeronautical combustor. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2015, 373, 20140335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, D.Z.; Lacoste, D.A.; Laux, C.O. Nanosecond repetitively pulsed discharges in air at atmospheric pressure—The spark regime. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2010, 19, 065015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Song, F.; Bian, D. Experimental investigation of gliding arc plasma fuel injector for ignition and extinction performance improvement. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, I.B.; Matveeva, S.A.; Kirchuk, E.Y.; Serbin, S.I.; Bazarov, V.G. Plasma fuel nozzle as a prospective way to plasma-assisted combustion. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2010, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jin Di Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Experimental investigation of spray characteristics of gliding arc plasma airblast fuel injector. Fuel 2021, 293, 120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jin Di Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Experimental investigation on spray and ignition characteristics of plasma actuated bluff body flameholder. Fuel 2022, 309, 122215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, R.; Tu, X.; Shao, T. Highly efficient conversion of methane using microsecond and nanosecond pulsed spark discharges. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Jin, D.; Jia, M.; Wei, W.; Song, H.; Wu, Y. Experimental study of n-decane decomposition with microsecond pulsed discharge plasma. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2017, 19, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Wu, Y.; Xu, S.; Jin, D.; Jia, M. N-decane decomposition by microsecond pulsed DBD plasma in a flow reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 3569–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesueur, H.; Czernichowski, A.; Chapelle, J. Device for generating low-temperature plasmas by formation of sliding electric discharges. French Patent 2639172, 17 November 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Weber, A.; Zhu, A. Plasma chain catalytic reforming of methanol for on-board hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.J.; Geiger, R.; Polevich, A.; Rabinovich, A.; Gutsol, A.; Fridman, A. On-board plasma-assisted conversion of heavy hydrocarbons into synthesis gas. Fuel 2010, 89, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Zhang, H.; Yan, S.X.; Yan, J.H.; Du, C.M. Hydrogen production from partial from partial oxidation of methane using an AC rotating gliding arc reactor. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2013, 41, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.; Cha, M.S.; Song, Y.H. Optimization scheme of a rotating gliding arc reactor for partial oxidation of methane. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2007, 31, 3343–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, C.S.; Gutsol, A.F.; Fridman, A.A. Gliding arc discharges as a source of intermediate plasma for methane partial oxidation. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2005, 33, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.L.; Wu, Y.; Xu, S.D.; Yang, X.K.; Xuan, Y.B. N-Decane reforming by gliding arc plasma in air and nitrogen. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2020, 40, 1429–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Bao, W.; Yu, D. Flame establishment and flameholding modes spontaneous transformation in kerosene axisymmetric supersonic combustor with a plasma igniter. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 119, 107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ban, Y.; Zhao, G.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Cai, Z.; et al. Suppression of combustion mode transitions in a hydrogen-fueled scramjet combustor by a multi-channel gliding arc plasma. Combust. Flame 2022, 237, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhan, H.; Zheng, J. Study of arc resistance model for short air gap. High Volt. Appar. 2012, 48, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Multi-Circuit Discharge Plasma Synthetic Jet Actuator and Its Application in Controlling Shock Wave/Boundary Layer Interaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Air Force Engineering University, Xi’an, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, N.A. Investigation of the mechanism for rapid heating of nitrogen and air in gas discharges. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2001, 27, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumghar, A.; Legrand, J.C.; Diamy, A.M.; Turillon, N.; Ben-Aïm, R.I. A kinetic study of methane conversion by a dinitrogen microwave plasma. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 1994, 14, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstaali, B.; Boubert, P.; Cheron, B.G.; Addou, A.; Brisset, J.L. Density and rotational temperature measurement of the OH and NO radicals produced by a gliding arc in humid air. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2002, 22, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Du, B.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, L. Dynamics of large-scale magnetically rotating arc plasmas. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 211501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.; Rincon, R.; Marinas, A.; Calzada, M.D. Hydrogen production from ethanol decomposition by a microwave plasma: Influence of the plasma gas flow. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 8708–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, C. Radiation and nonequilibrium collisional-radiative models. In Physico-Chemical Modeling of High Enthalpy and Plasma Flows; Von Karman Institute Lecture Series; Fletcher, D., Charbonnier, J.-M., Sarma, G.S., Magin, T., Eds.; Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics: Sint-Genesius-Rode, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.H.; Xi, S.H.; Zhang, L.N.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Hou, J.X. Numerical investigation for effects of small molecule fuels additive on RP-3 aviation kerosene combustion. J. Propuls. Technol. 2018, 39, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.