A Unified Optimization Approach for Heat Transfer Systems Using the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Extend BxR and MO-BxR algorithms for the optimization of representative heat transfer systems.

- (2)

- Evaluate their ability to generate high-quality Pareto-optimal solutions for multi-objective heat transfer problems.

- (3)

- Use surrogate models like RSM together with a robust, parameter-free optimization framework to cut computational cost, simplify design, and support practical engineering decisions in thermal and energy systems.

- (4)

- Use a simple decision-making method after optimization to select the most balanced compromise solution from the Pareto front.

2. Materials and Methods: Description of the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms for Optimization

2.1. Description of the BxR Algorithms for Single-Objective Optimization

- X{v,b,i}: best value Xb

- X{v,w,i}: worst value Xw

- X{v,m,i}: mean value Xm

- X{v,r,i}: random value Xr

2.1.1. Best–Worst–Random (BWR) Algorithm

2.1.2. Best–Mean–Random (BMR) Algorithm

2.1.3. Best–Mean–Worst–Random (BMWR) Algorithm

2.2. Description of the MO-BxR Algorithms for Multi-Objective Optimization

- Start—Initialize the optimization procedure.

- Generate Initial Population—Create the initial population of candidate solutions randomly within the prescribed variable bounds.

- Elite Seeding—Incorporate high-quality or previously identified strong solutions to enrich the starting population.

- Fast Non-dominated Sorting—Organize solutions into Pareto fronts and compute their crowding distances.

- Constraint Checking and Repair—Detect and correct constraint violations whenever feasible.

- Penalty Application—Apply penalty functions to any solution with unrepairable constraint violations to steer the search appropriately.

- Objective Evaluation—Evaluate all objective functions for every solution in the population.

- Edge Boosting—Enhance exploration near extreme regions of the Pareto front to improve boundary diversity.

- Local Exploration—Perform localized search around elite or promising solutions to refine solution quality.

- MO-BWR/MO-BMR/MO-BMWR Update—Generate updated solutions using the specific update rule.

- Termination Check—Assess whether the stopping criterion (e.g., maximum iterations) has been satisfied.

- Search Continuation—If the termination condition is not met, return to the constraint-handling stage and continue the evolutionary process.

- Output Pareto Front—Produce the final set of non-dominated solutions representing the approximated Pareto front.

3. Case Studies, Results and Discussion on Applying the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms for Optimizing Different Heat Transfer Systems

3.1. Design Optimization of a Heat Exchanger Network

- x1 = Heat exchanger area for heat exchanger #1

- x2 = Heat exchanger area for heat exchanger #2

- x3 = Heat flow rate or heat duty

- x4 = Flow rate factor for the first heat exchanger/fluid stream

- x5 = Heat flow or energy transfer requirement (large scale)

- x6 = Flow rate factor for the second exchanger/fluid stream

- x7, x8, and x9 are temperatures at different nodes

100 ≤ x7 ≤ 600, 100 ≤ x8 ≤ 600, and 100 ≤ x9 ≤ 900

- g1(x): Ensures heat duty x3 matches exchanger #1 capacity (area x1 and flow x4).

- g2(x): Ensures heat load x5 matches exchanger #2 capacity (area x2 and flow x6).

- g3(x): Energy balance linking x3 to temperature rise up to node x7.

- g4(x): Energy balance linking x5 to temperature drop from 300 °C to x7.

- g5(x): Relates heat duty x3 to temperature drop involving node x8.

- g6(x): Relates heat load x5 to the temperature change up to node x9.

- g7(x): LMTD-based constraint using temperatures x7, x8, and flow x4.

- g8(x): LMTD-based constraint using temperatures x7, x9, and flow x6.

3.2. Single-Objective Optimization of Design and Operating Parameters of Jet-Plate Solar Air Heater (JPSAH)

- Glass cover (single transparent sheet): Allows solar radiation to enter while reducing convective heat loss to the ambient environment.

- Absorber plate (black-coated): Converts incident solar irradiance into heat. Its upper surface loses heat to the glass cover and ambient air, while the lower surface transfers heat to the impinging jet flow.

- Jet-plate: A thin plate containing uniformly sized holes/nozzles that accelerate the incoming air into high-velocity jets.

- Air channel: The region between the jet-plate and absorber plate (and between the jet-plate and back plate) where the jets impinge, mix, and flow toward the outlet.

- Back plate with insulation: Reduces heat losses from the rear side of the system.

- Inlet/Outlet: Ambient or process air enters through the inlet, is heated by the absorber via jet impingement, and is discharged through the outlet.

1.89810 * D − 15.63062 * E + 0.59211 * A * B − 0.25318 * A * C − 0.43423 * A * D + 4.10535 * A * E −

67.91390 * B * C − 125.66138 * B * D + 952.90466 * B * E − 4.93038 * C * D − 2348.28454 * B2

and 0.003 m ≤ E ≤ 0.005 m.

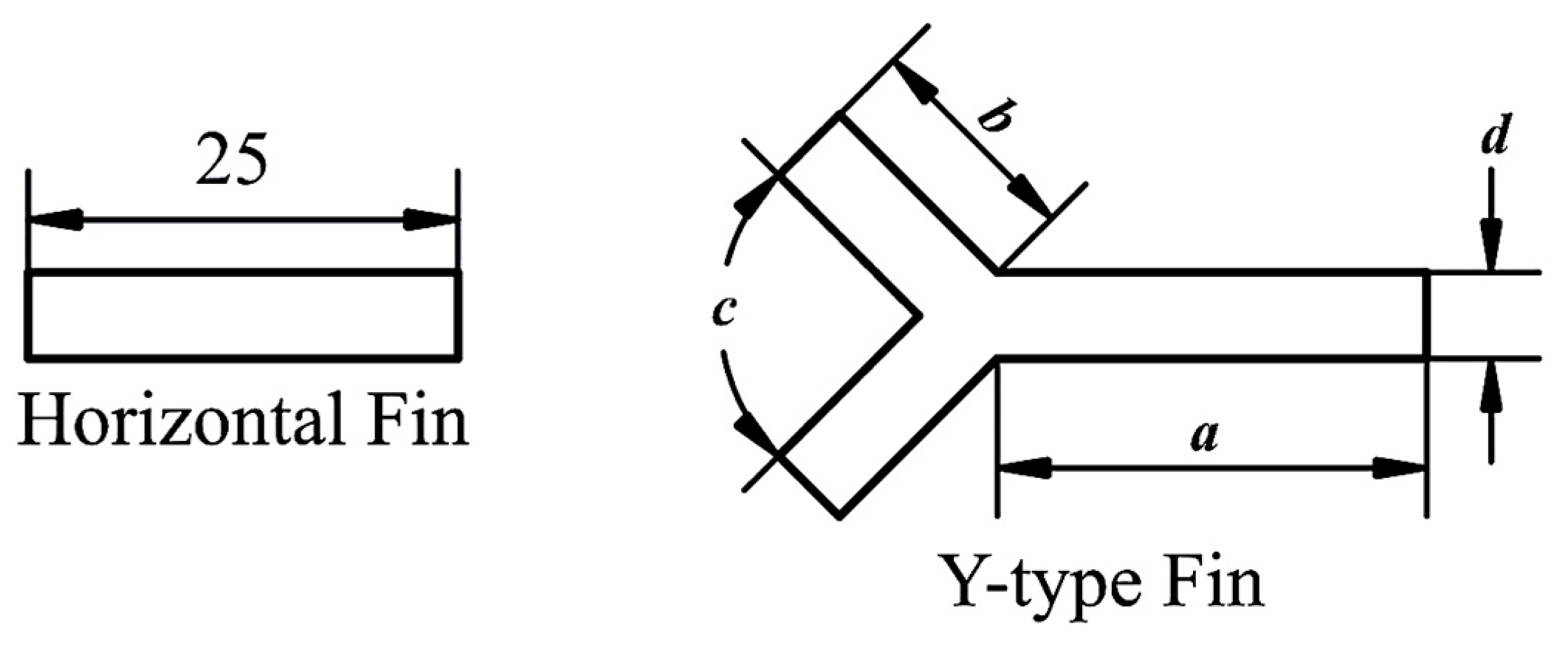

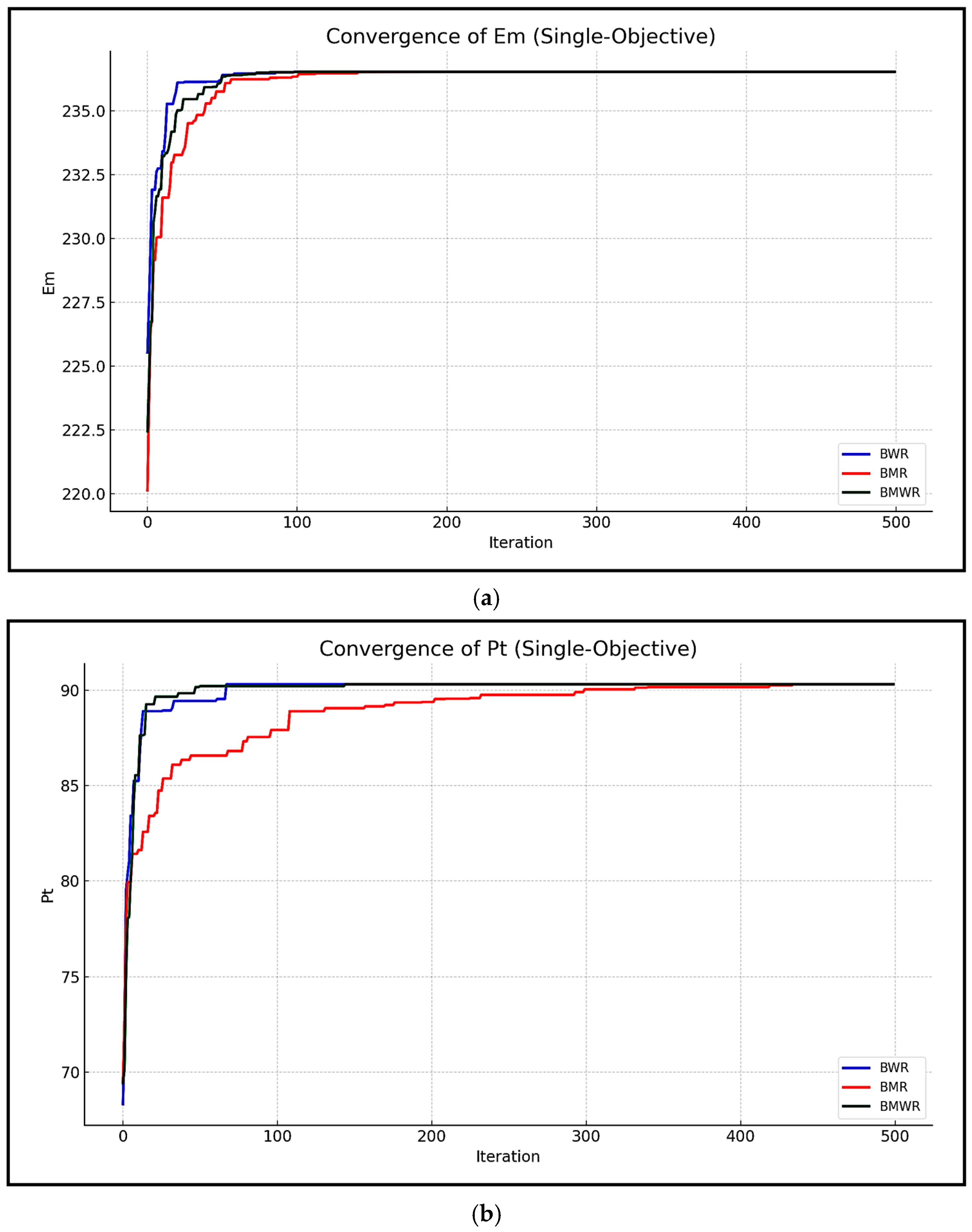

3.3. Design Parameters Optimization of Y-Type Fin Structure in Rectangular Phase-Change Energy Storage Units for Thermal Energy Storage (2-Objectives)

0.004025 * a * c − 0.72222 * a * d + 0.000569 * b * c − 0.355625 * b * d − 0.012361 * c * d +

0.005761 * a2 + 0.020182 * b2 + 0.000047 * c2 + 0.746979 * d2

0.008012 * a * c + 0.335833 * a * d − 0.018736 * b * c + 0.4225 * b * d − 0.012889 * c * d +

0.175041 * a2 + 0.277708 * b2 + 0.000986 * c2 + 1.114890 * d2

- High-Em designs when maximizing stored energy or charging performance, which is critical;

- High-Pt designs when heat transfer capability, which is the priority;

- Compromise designs that balance both objectives efficiently.

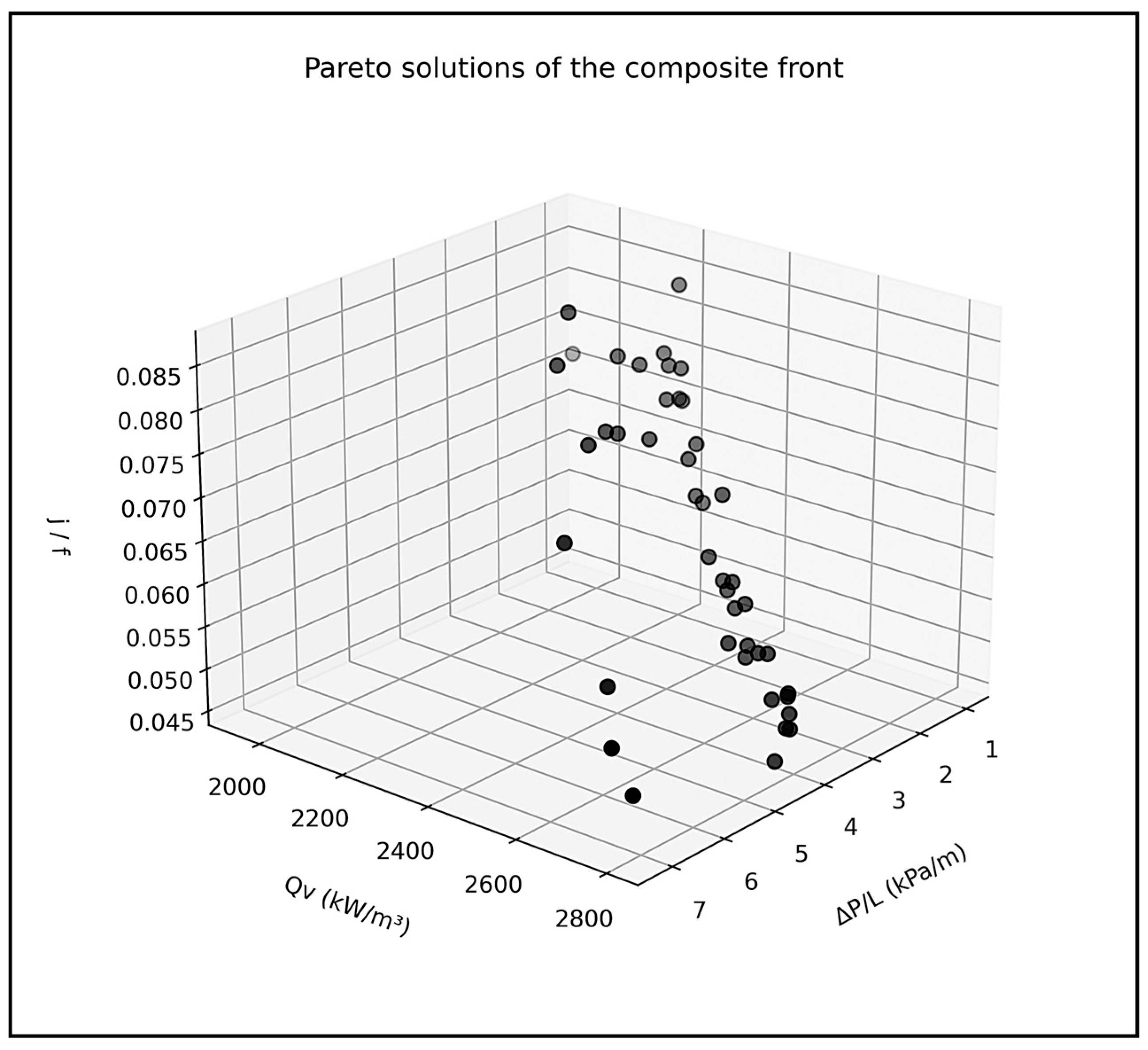

3.4. Design and Performance Optimization of a Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS)–Fin-Based Three-Fluid Heat Exchanger (3-Objectives)

0.0468 * D * Fs + 0.3552 * D * w + 0.2444 * D * u + 0.0077 * V * Fs + 0.0725 * V * w + 0.0005 * V * u −

0.0345 * Fs * w + 0.0132 * Fs * u + 0.2226 * w * u − 0.5868 * D2 − 0.0130 * V2 − 0.0048 * Fs2 −

1.8653 * w2 − 0.1095 * u2

6.3099 * D * V + 4.0928 * D * Fs + 9.8830 * D * w + 2.4911 * D * u − 1.0088 * V * Fs +

17.7390 * V * w + 1.9293 * V * u − 9.3141 * Fs * w − 0.9787 * Fs * u + 11.5879 * w * u +

6.7370 * D2 − 0.2754 * V2 + 0.6284 * Fs2 + 1.0416 * w2 + 0.3242 * u2

0.0001 * D * Fs − 0.0080 * D * w + 0.0009 * D * u − 0.0011 * V * u + 0.0019 * Fs * w −

0.0001 * Fs * u + 0.0022 * w * u + 0.0124 * D2 + 0.0002 * V2 + 0.009 * w2 + 0.0018 * u2

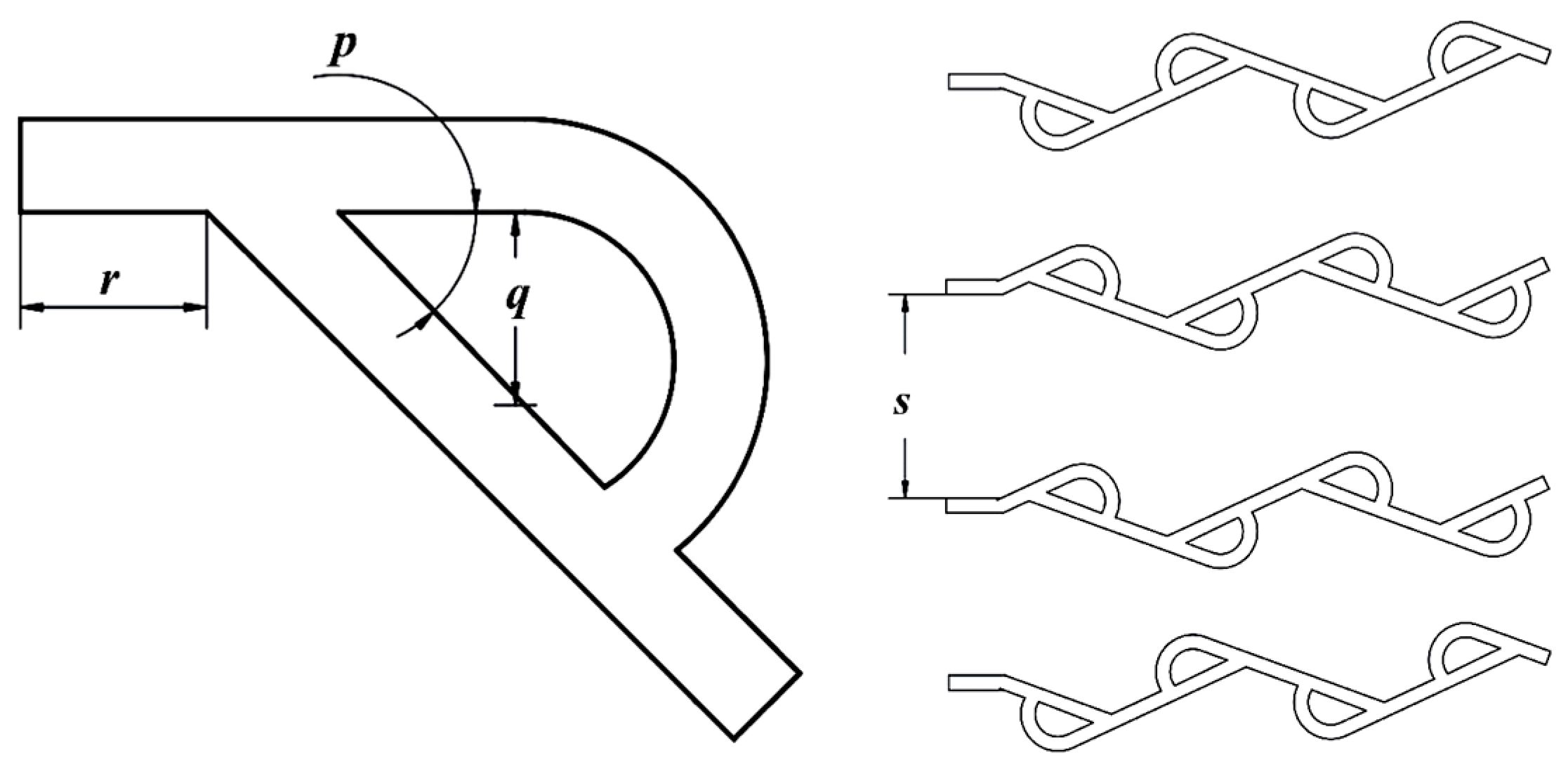

3.5. Multi-Objective Optimization of a Tesla-Valve Direct-Evaporative Cold Plate for LiFePO4 Modules (3-Objectives)

0.01892391 * q2 − 0.00056089 * r2 + 0.00265559 * s2 − 0.0033455 * p * q + 0.00021796 * p * r +

0.0001149 * p * s + 0.0057255 * q * r + 0.0007003 * q * s − 0.00058177 * r * s

0.0118352 * q2 + 0.0173193 * r2 + 0.00151787 * s2 + 0.00094303 * p * q − 0.00282608 * p * r −

0.00064754 * p * s + 0.02815675 * q * r + 0.00199447 * q * s + 0.00133136 * r * s

2.142945 * r2 − 0.117625 * s2 − 0.453103 * p * q + 0.05122 * p * r + 0.206428 * p * s + 4.593471 * q * r +

1.654882 * q * s + 0.617446 * r * s

- All variables strictly adhered to the original bounds of the DOE;

- No solution is allowed to enter unexplored or extrapolated regions;

- The surrogate models are used precisely in the same manner as in earlier publications.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinik, R.A.; Bhuiyan, A.A.; Karim, M.R. Performance enhancement of double-tube heat exchangers using nonuniformly twisted elliptical tubes: A CFD-based multi-objective optimization approach via RSM and NSGA-II. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 69, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qian, Y.; Gong, Z. Multi-objective optimization of the TPMS-fin three-fluid heat exchanger for vehicles using RSM–NSGA-III. Energy 2025, 328, 136462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, P. Multi-objective optimization research of printed circuit heat exchanger based on RSM and NSGA-II. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadibafekr, S.; Mirzaee, I.; Shirvani, H. Thermo-entropic analysis and multi-objective optimization of wavy lobed heat exchanger tube using DOE, RSM, and NSGA-II algorithm. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 184, 107921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qian, Y.; Qian, D. Optimization and performance analysis of a gyroid-fin-based three-fluid heat exchanger using advanced multi-objective optimization techniques. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 166, 109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Xu, J.; Cheng, J. Multi-objective optimization of vortex generators for enhanced thermal–fluid performance in finned-tube heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2026, 283, 128946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, H. Multi-objective optimization of the plate-fin heat exchanger coupled with ortho–para hydrogen conversion for hydrogen liquefaction. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 175, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wang, N.; Shao, S. A comprehensive investigation of shell-and-tube heat exchangers based on porous baffle design and multi-objective parameter optimization. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 221, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, Y.-G.; Jin, T.-X. Multi-objective optimization study on heat transfer performance of solar salt in non-circular twisted tube heat exchanger based on entropy generation number and NSGA-II. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 211, 109681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzied, A.S.; Basem, A.; Babiker, S.G. Thermal performance optimization of microchannel heat sinks with triangle wave fin designs and various heat transfer fluids using GA/RSM/TOPSIS. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 72, 106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M.; Maganti, L.S. Multi-objective optimization of parallel microchannel heat sink with u-, i-, and z-type manifold configurations by RSM and NSGA-II. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 201, 123641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Zunaid, M.; Mishra, R.S. Multi-objective optimization of the hydrothermal and exergetic performance of a convergent–divergent microchannel heat sink using ANN, NSGA-II, and TOPSIS algorithms. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 67, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, M.; Li, J. Multi-objective optimization of a bionic microchannel heat sink based on fibonacci spiral for electronic components. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 253, 127544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, C. Thermal–hydraulic performance and multi-objective design optimization of a microchannel heat sink with hollow twisted tapes. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2025, 116, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L. Geometric multi-objective optimization of a microchannel–pin-fin hybrid heat sink. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 221, 109711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Sun, R.; Zhou, P. Multi-objective optimization of flow boiling heat transfer in a manifold microchannel heat sink with curved corners. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 247, 127182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chen, C.; Wang, L. Enhanced cooling performance of reflective high-concentration photovoltaic cells using optimized double-layer spider web microchannel heat sinks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, M.; Chen, L. Design and optimization of a novel microchannel heat sink integrated with nanoporous membrane for ultra-high-heat-flux thermal management. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 253, 127538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, H.; Shao, S. Multi-objective optimization of wavy microchannel heat sinks with symmetric configurations generated by interpolation curves. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, C. Multi-objective optimization on thermal–hydraulic performance of symmetrical hierarchical microchannel heat sinks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 271, 126309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridy, S.; Radwan, A.; Abdelrehim, O. Thermal management of high-concentrator photovoltaic modules using an optimized microchannel heat sink. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Abdellatif, H.E.; Alhushaybari, A. Investigation and optimization of shell-and-tube thermal energy storage unit with biomimetic leaf-vein fins and carbon nanotubes for superior PCM efficiency. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 167, 109250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Li, Q.; Xue, C. Enhanced casing molten salt thermal energy storage through cobblestone-fin composite: Multi-objective optimization with RSM and NSGA-II. J. Energy Storage 2025, 105, 114575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedrtnam, A.; Kalauni, K.; Soares, N. Hybrid optimization of phase change material-based thermal storage for hvac efficiency in commercial buildings. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 128143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Multi-objective optimization of y-type fin structure in rectangular phase change energy storage units. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 276, 126899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Cui, L. Optimization of a novel fin structure and heat transfer characteristics of a phase change thermal energy storage unit. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchane, H.; Mekhilef, S.; Tey, K.S. Maximizing energy efficiency and drying quality in pvt-pcm solar dryers through multi-objective optimization and nocturnal heat release analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2026, 282, 128774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, K.; Mahboobtosi, M.; Ganji, D.D. Optimization of antenna-shaped fins configuration for enhanced solidification in triplex thermal energy storage systems with radiative heat transfer. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qader, B.S.; Supeni, E.E.; Abu Talib, A.R. RSM approach for modeling and optimization of designing parameters for inclined fins of solar air heater. Renew. Energy 2019, 139, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, P.K.; Das, P.P.; Kundu, B. Parametric optimization of solar air heaters with dimples on absorber plates using metaheuristic approaches. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 233, 121242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, P.K.; Kundu, B. Experimental and meta-heuristic optimization for the highest thermo-hydraulic performance of a solar air heater with a v-notch pattern of hemispherical protrusions on absorber surfaces. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 156, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, B. Multi-parameters optimization design of downward jet solar air collector with corrugated absorber plate structure. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 164, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamida, M.B.; Rasheed, R.H.; Chamkha, A. Intelligent design framework for finned solar air heaters: A synergy between pso/ga-tuned mlpnn and multi-objective crystal structure algorithm (MOCryStAl). Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 170, 108560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Xiao, Q. Multi-objective optimization design of solar air collector with a frustum-shaped protrusion. Sol. Energy 2024, 262, 112558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Lee, D. Parametric optimization of an impingement jet solar air heater for active green heating in buildings using hybrid CRITIC–COPRAS approach. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 198, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobayen, S.; Assareh, E.; Garcia, D.A. Dynamic analysis and multi-objective optimization of an integrated solar energy system for zero-energy residential complexes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 305, 118480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheswaran, M.M.; Arjunan, T.V.; Muthusamy, S.; Natrayan, L.; Panchal, H.; Subramaniam, S.; Khedkar, N.K.; El-Shafay, A.S.; Sonawane, C. A case study on thermo-hydraulic performance of jet plate solar air heater using response surface methodology. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yuan, K.; Peng, W.; He, S.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J. Flow pattern analysis and multi-objective optimization of helically corrugated tubes used in the intermediate heat exchanger for nuclear hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 4885–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; He, L.; Deng, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, L. Multi-objective optimization of a tesla-valve direct-evaporative cold plate for prismatic LiFePO4 modules using RSM–NSWOA. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2026, 282, 128848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Davim, J.P. Single, Multi-, and many-objective optimization of manufacturing processes using two novel and efficient algorithms with integrated decision-making. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Davim, J.P. Optimization of different metal casting processes using three simple and efficient advanced algorithms. Metals 2025, 15, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V. BHARAT: A simple and effective multi-criteria decision-making method that does not need fuzzy logic. Part 1: Multi-attribute decision-making applications in the industrial environment. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2024, 15, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Shah, R. BMR and BWR: Two simple metaphor-free optimization algorithms for solving real-life non-convex constrained and unconstrained problems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.11149v2. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.; Wu, M.Z.; Ali, R.; Mallipeddi, P.N.; Suganthan, S.; Das, S. A test-suite of non-convex constrained optimization problems from the real-world and some baseline results. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2020, 56, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.; Srinivasan, N.; Biswas, N. An improved unified differential evolution algorithm for constrained optimization problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1231–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, M.; Beyer, H.-G. A matrix adaptation evolution strategy for constrained real-parameter optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Fang, Y.; Li, W.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bian, X. LSHADE44 with an improved ε constraint-handling method for solving constrained single-objective optimization problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Javier, G.R.; Aguirre, A.H.; Cedeño, O.D. COLSHADE for real-world single-objective constrained optimization problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, K.M.; Elsayed, S.M.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Ryan, M.J. Multioperator differential evolution algorithm for solving real-world constrained optimization problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), San Sebastián, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Floudas, C.A.; Ciric, A.R.; Grossmann, J.E. Automatic synthesis of optimum heat exchanger network configurations. AIChE J. 1986, 32, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Best | Median | Mean | Worst | Std. Dev. | FR | MV | SR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUDE [44] | 189 | 260 | 229 | 285 | 80.6 | 24 | 0.0000112 | 4 |

| εMAgES [44] | 189 | 492 | 455 | 437 | 223 | 84 | 0.000147 | 20 |

| iLSHADEε [44] | 190 | 194 | 206 | 229 | 19.3 | 28 | 0.0136 | 4 |

| COLSHADE [48] | 189.48406 | 209.452 | 210.4055 | 217.2743 | 25.4516 | 88 | - | - |

| EnMODE [49] | 189.31 | 189.31 | 189.31 | 189.31 | 0 | 100 | - | - |

| BWR | 189.31162966 | 189.31162966 | 189.31162966 | 189.31162966 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| BMR | 189.31162966 | 189.31163566 | 189.31163566 | 189.31172133 | 0.00001564 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| BMWR | 189.31162966 | 189.31163254 | 189.31163254 | 189.311742322 | 0.00002004 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Method | JPSAH Input Parameters | Thermo-Hydraulic Efficiency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collector Length (A) m | Flow Rate of Air (B) kg/s | Stream-Wise Pitch (C) m | Span-Wise Pitch (D) m | Jet Diameter (E) m | ||

| RSM [37] | 1.5108 | 0.01386 | 0.05108 | 0.03414 | 0.0046 | 0.6812 |

| Analytical [37] | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP | 0.6830 |

| BWR | 1.5000 | 0.01357678 | 0.0400 | 0.0300 | 0.0050 | 0.6910879 |

| BMR | 1.5000 | 0.01357678 | 0.0400 | 0.0300 | 0.0050 | 0.6910879 |

| BMWR | 1.5000 | 0.01357678 | 0.0400 | 0.0300 | 0.0050 | 0.6910879 |

| Algorithm | Best η | Mean η | Std. Dev. of η |

|---|---|---|---|

| BWR | 0.6910879 | 0.691063465 | 0.00003696 |

| BMR | 0.6910879 | 0.691070089 | 0.00003301 |

| BMWR | 0.6910879 | 0.691071520 | 0.00003546 |

| Algorithm | Y-Fin Design Parameters | Best Em (kJ/kg) | Best Pt (W) | Mean Em (kJ/kg) | Mean Pt (W) | Std. Dev. of Em (kJ/kg) | Std. Dev. of Pt (W) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Segment Length (a) mm | Branch Segment Length (b) mm | Branch Angle (c) ° | Fin Thickness (d) mm | |||||||

| BWR | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 0 | 0 |

| BMR | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 0 | 0 |

| BMWR | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | 0 | 0 |

| BWR | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 0 | 0 |

| BMR | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 0 | 0 |

| BMWR | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | 0 | 0 |

| Solution | Y-Fin Design Parameters | Em (kJ/kg) | Pt (W) | Algorithm | Normalized Em | Normalized Pt | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Segment Length (a) mm | Branch Segment Length (b) mm | Branch Angle (c) ° | Fin Thickness (d) mm | |||||||

| 1 | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 236.534 | 41.972 | All algorithms | 1 | 0.464816 | 0.766553 |

| 2 | 26.627 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 224.04 | 42.01 | MO-BWR | 0.947179 | 0.465237 | 0.736956 |

| 3 | 26.633 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 224.025 | 42.015 | MO-BMR | 0.947115 | 0.465293 | 0.736944 |

| 4 | 26.689 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 223.907 | 42.06 | MO-BMWR | 0.946617 | 0.465791 | 0.73688 |

| 5 | 27.323 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 222.546 | 42.646 | MO-BWR | 0.940863 | 0.472281 | 0.736467 |

| 6 | 28.244 | 15.997 | 90 | 2 | 220.582 | 43.74 | MO-BWR | 0.932559 | 0.484396 | 0.737071 |

| 7 | 28.249 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 220.57 | 43.754 | MO-BMWR | 0.932509 | 0.484551 | 0.73711 |

| 8 | 28.261 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 220.543 | 43.771 | MO-BMR | 0.932394 | 0.484739 | 0.737127 |

| 9 | 29.064 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 218.837 | 44.979 | MO-BWR | 0.925182 | 0.498117 | 0.738896 |

| 10 | 30.089 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 216.669 | 46.849 | MO-BWR | 0.916016 | 0.518827 | 0.742762 |

| 11 | 30.396 | 15.919 | 90 | 2 | 216.099 | 47.208 | MO-BMWR | 0.913607 | 0.522802 | 0.743138 |

| 12 | 30.812 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 215.147 | 48.389 | MO-BWR | 0.909582 | 0.535881 | 0.746574 |

| 13 | 30.865 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 215.037 | 48.508 | MO-BMR | 0.909117 | 0.537199 | 0.746886 |

| 14 | 31.485 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 213.736 | 49.987 | MO-BWR | 0.903616 | 0.553578 | 0.75093 |

| 15 | 31.627 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 213.44 | 50.344 | MO-BMWR | 0.902365 | 0.557532 | 0.751949 |

| 16 | 32.104 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 212.443 | 51.597 | MO-BMWR | 0.89815 | 0.571408 | 0.755625 |

| 17 | 32.638 | 15.996 | 90 | 2 | 211.334 | 53.079 | MO-BWR | 0.893461 | 0.58782 | 0.760141 |

| 18 | 32.818 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 210.956 | 53.621 | MO-BMWR | 0.891863 | 0.593823 | 0.761858 |

| 19 | 33.17 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 210.228 | 54.682 | MO-BMR | 0.888786 | 0.605573 | 0.765248 |

| 20 | 33.327 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 209.901 | 55.171 | MO-BWR | 0.887403 | 0.610988 | 0.766831 |

| 21 | 33.575 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 209.387 | 55.961 | MO-BMWR | 0.88523 | 0.619737 | 0.769422 |

| 22 | 33.746 | 15.971 | 90 | 5.78 | 78.092 | 86.22 | MO-BMR | 0.330151 | 0.954838 | 0.60264 |

| 23 | 33.852 | 15.965 | 90 | 5.734 | 79.063 | 86.113 | MO-BWR | 0.334256 | 0.953653 | 0.604437 |

| 24 | 33.996 | 15.974 | 90 | 2.41 | 193.239 | 58.966 | MO-BWR | 0.816961 | 0.653016 | 0.745448 |

| 25 | 33.998 | 16 | 90 | 4.546 | 117.439 | 74.195 | MO-BMWR | 0.496499 | 0.821668 | 0.638338 |

| 26 | 34 | 8 | 173.443 | 2 | 217.266 | 45.666 | MO-BMR | 0.91854 | 0.505725 | 0.73847 |

| 27 | 34 | 15.909 | 90 | 5.604 | 82.653 | 84.926 | MO-BMWR | 0.349434 | 0.940508 | 0.60726 |

| 28 | 34 | 15.94 | 90 | 2.939 | 173.858 | 61.616 | MO-BWR | 0.735023 | 0.682363 | 0.712053 |

| 29 | 34 | 15.94 | 90 | 3.189 | 164.866 | 63.143 | MO-BWR | 0.697008 | 0.699274 | 0.697996 |

| 30 | 34 | 15.957 | 90 | 4.736 | 111.106 | 75.81 | MO-BWR | 0.469725 | 0.839553 | 0.631044 |

| 31 | 34 | 15.974 | 90 | 3.834 | 141.971 | 67.906 | MO-BWR | 0.600214 | 0.752021 | 0.666432 |

| 32 | 34 | 15.997 | 90 | 6 | 69.793 | 90.282 | MO-BWR | 0.295065 | 0.999823 | 0.602481 |

| 33 | 34 | 15.998 | 90 | 5.116 | 98.401 | 79.936 | MO-BWR | 0.416012 | 0.885247 | 0.620692 |

| 34 | 34 | 15.999 | 90 | 4.239 | 127.924 | 71.396 | MO-BWR | 0.540827 | 0.790671 | 0.649809 |

| 35 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 208.51 | 57.362 | MO-BMR, MO-BMWR | 0.881522 | 0.635252 | 0.774099 |

| 36 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.085 | 205.315 | 57.691 | MO-BMR | 0.868015 | 0.638896 | 0.768073 |

| 37 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.118 | 204.058 | 57.825 | MO-BWR | 0.8627 | 0.64038 | 0.765724 |

| 38 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.195 | 201.192 | 58.141 | MO-BMWR | 0.850584 | 0.643879 | 0.760419 |

| 39 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.2 | 200.988 | 58.163 | MO-BMR | 0.849721 | 0.644123 | 0.760039 |

| 40 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.247 | 199.26 | 58.361 | MO-BWR | 0.842416 | 0.646316 | 0.756877 |

| 41 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.331 | 196.133 | 58.732 | MO-BMWR | 0.829196 | 0.650424 | 0.751216 |

| 42 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.366 | 194.834 | 58.892 | MO-BMR | 0.823704 | 0.652196 | 0.748892 |

| 43 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.437 | 192.207 | 59.222 | MO-BMWR | 0.812598 | 0.655851 | 0.744225 |

| 44 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.439 | 192.108 | 59.235 | MO-BWR | 0.812179 | 0.655995 | 0.744051 |

| 45 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.568 | 187.371 | 59.863 | MO-BMWR | 0.792153 | 0.662949 | 0.735794 |

| 46 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.598 | 186.259 | 60.017 | MO-BWR | 0.787451 | 0.664655 | 0.733887 |

| 47 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.618 | 185.503 | 60.122 | MO-BMR | 0.784255 | 0.665818 | 0.732593 |

| 48 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.682 | 183.172 | 60.454 | MO-BMR | 0.7744 | 0.669494 | 0.72864 |

| 49 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.707 | 182.26 | 60.587 | MO-BMWR | 0.770545 | 0.670967 | 0.727109 |

| 50 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.787 | 179.313 | 61.025 | MO-BWR | 0.758086 | 0.675818 | 0.7222 |

| 51 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2.86 | 176.662 | 61.434 | MO-BMR | 0.746878 | 0.680347 | 0.717857 |

| 52 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.033 | 170.378 | 62.454 | MO-BMWR | 0.720311 | 0.691643 | 0.707806 |

| 53 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.065 | 169.226 | 62.649 | MO-BWR | 0.71544 | 0.693803 | 0.706002 |

| 54 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.288 | 161.24 | 64.072 | MO-BMWR | 0.681678 | 0.709562 | 0.693841 |

| 55 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.292 | 161.075 | 64.102 | MO-BMR | 0.68098 | 0.709894 | 0.693592 |

| 56 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.39 | 157.598 | 64.762 | MO-BMR | 0.666281 | 0.717203 | 0.688493 |

| 57 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.423 | 156.429 | 64.989 | MO-BMWR | 0.661338 | 0.719717 | 0.686803 |

| 58 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.532 | 152.541 | 65.764 | MO-BMR | 0.644901 | 0.7283 | 0.681279 |

| 59 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.546 | 152.072 | 65.86 | MO-BWR | 0.642918 | 0.729363 | 0.680625 |

| 60 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.567 | 151.325 | 66.013 | MO-BMWR | 0.63976 | 0.731057 | 0.679584 |

| 61 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.657 | 148.141 | 66.678 | MO-BMWR | 0.626299 | 0.738422 | 0.675207 |

| 62 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.663 | 147.933 | 66.722 | MO-BMR | 0.62542 | 0.738909 | 0.674924 |

| 63 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.689 | 147.003 | 66.921 | MO-BWR | 0.621488 | 0.741113 | 0.673668 |

| 64 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.731 | 145.529 | 67.24 | MO-BMR | 0.615256 | 0.744646 | 0.671696 |

| 65 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.796 | 143.265 | 67.738 | MO-BMWR | 0.605685 | 0.750161 | 0.668705 |

| 66 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.921 | 138.909 | 68.726 | MO-BMR | 0.587269 | 0.761102 | 0.663095 |

| 67 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.935 | 138.431 | 68.837 | MO-BMR | 0.585248 | 0.762331 | 0.662492 |

| 68 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 3.95 | 137.892 | 68.963 | MO-BWR | 0.582969 | 0.763727 | 0.661816 |

| 69 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.053 | 134.339 | 69.807 | MO-BMWR | 0.567948 | 0.773074 | 0.657424 |

| 70 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.104 | 132.578 | 70.235 | MO-BMR | 0.560503 | 0.777813 | 0.655294 |

| 71 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.121 | 131.963 | 70.386 | MO-BMWR | 0.557903 | 0.779486 | 0.654557 |

| 72 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.124 | 131.856 | 70.413 | MO-BMR | 0.557451 | 0.779785 | 0.654433 |

| 73 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.185 | 129.781 | 70.929 | MO-BMWR | 0.548678 | 0.785499 | 0.651979 |

| 74 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.31 | 125.49 | 72.028 | MO-BMWR | 0.530537 | 0.79767 | 0.64706 |

| 75 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.363 | 123.659 | 72.509 | MO-BWR | 0.522796 | 0.802997 | 0.645019 |

| 76 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.487 | 119.433 | 73.649 | MO-BWR | 0.50493 | 0.815622 | 0.640453 |

| 77 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.661 | 113.568 | 75.299 | MO-BMR | 0.480134 | 0.833894 | 0.634444 |

| 78 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.669 | 113.302 | 75.376 | MO-BMWR | 0.479009 | 0.834747 | 0.634182 |

| 79 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.742 | 110.829 | 76.097 | MO-BMWR | 0.468554 | 0.842732 | 0.63177 |

| 80 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.848 | 107.284 | 77.156 | MO-BMWR | 0.453567 | 0.85446 | 0.628436 |

| 81 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.86 | 106.901 | 77.272 | MO-BMR | 0.451948 | 0.855744 | 0.628084 |

| 82 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.894 | 105.764 | 77.619 | MO-BMR | 0.447141 | 0.859587 | 0.62705 |

| 83 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 4.956 | 103.697 | 78.259 | MO-BMWR | 0.438402 | 0.866675 | 0.625215 |

| 84 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.005 | 102.075 | 78.767 | MO-BWR | 0.431545 | 0.872301 | 0.623802 |

| 85 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.011 | 101.871 | 78.832 | MO-BMR | 0.430682 | 0.87302 | 0.62363 |

| 86 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.099 | 98.934 | 79.771 | MO-BMWR | 0.418265 | 0.883419 | 0.621166 |

| 87 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.171 | 96.562 | 80.545 | MO-BMR | 0.408237 | 0.891991 | 0.619251 |

| 88 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.183 | 96.179 | 80.672 | MO-BWR | 0.406618 | 0.893397 | 0.618951 |

| 89 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.241 | 94.267 | 81.308 | MO-BMWR | 0.398535 | 0.900441 | 0.617466 |

| 90 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.302 | 92.259 | 81.986 | MO-BMR | 0.390045 | 0.907949 | 0.615955 |

| 91 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.344 | 90.914 | 82.446 | MO-BMWR | 0.384359 | 0.913043 | 0.614971 |

| 92 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.416 | 88.549 | 83.266 | MO-BMR | 0.374361 | 0.922125 | 0.613295 |

| 93 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.494 | 86 | 84.166 | MO-BWR | 0.363584 | 0.932092 | 0.611567 |

| 94 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.554 | 84.058 | 84.863 | MO-BWR | 0.355374 | 0.93981 | 0.610305 |

| 95 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.649 | 80.996 | 85.983 | MO-BMR | 0.342429 | 0.952214 | 0.608417 |

| 96 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.843 | 74.786 | 88.331 | MO-BWR | 0.316174 | 0.978217 | 0.604957 |

| 97 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.848 | 74.618 | 88.396 | MO-BMR | 0.315464 | 0.978936 | 0.604871 |

| 98 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.888 | 73.36 | 88.885 | MO-BMR | 0.310146 | 0.984352 | 0.604234 |

| 99 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 5.911 | 72.611 | 89.178 | MO-BMWR | 0.306979 | 0.987597 | 0.603864 |

| 100 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 69.787 | 90.298 | MO-BMWR | 0.29504 | 1 | 0.602544 |

| 101 | 34 | 16 | 90.137 | 4.403 | 122.313 | 72.838 | MO-BMR | 0.517105 | 0.80664 | 0.6434 |

| 102 | 34 | 16 | 98.118 | 5.823 | 75.058 | 86.284 | MO-BWR | 0.317324 | 0.955547 | 0.595717 |

| Method | Y-Fin Design Parameters | Em (kJ/kg) | Pt (W) | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Segment Length (a) mm | Branch Segment Length (b) mm | Branch Angle (c) ° | Fin Thickness (d) mm | ||||

| No fin [25] | --- | --- | --- | --- | 290.33 | 13.48 | The values of the design parameters are not provided. The Pt value is very low. |

| Horizontal fin [25] | --- | --- | --- | --- | 278.52 | 21.23 | The values of the design parameters are not provided. The Pt value is low. |

| Y-fin with NSGA [25] considering only Em | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 265.18 * (236.5342) | 41.97 | * The value of Em shown as 265.18 was incorrectly computed by Sun et al. [25]. The corrected value is now shown in brackets. |

| Y-fin with NSGA [25] considering only Pt | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 187.87 * (69.7866) | 90.30 * (90.29844) | * The value of Em shown as 187.87 was incorrectly computed by Sun et al. [25]. The corrected value is now shown in brackets. |

| Y-fin with NSGA [25] considering both Em and Pt with wEm = 0.5638 and wPt = 0.4362 | 33.97 | 15.94 | 90 | 2 | 247.1 * (208.62) | 57.02 * (57.009) | * The value of Em shown as 247.1 was incorrectly computed by Sun et al. [25]. The corrected value is now shown in brackets. |

| Y-fin with BxR algorithms considering only Em | 25 | 8 | 90 | 2 | 236.5342 | 41.9724 | BxR algorithms have given the highest Em and a reasonable Pt. |

| Y-fin with BxR algorithms considering only Pt | 34 | 16 | 90 | 6 | 69.7866 | 90.29844 | BxR algorithms have given the highest Pt and a reasonable Em. |

| Y-fin with the MO- BxR algorithms with wEm = 0.5638 and wPt = 0.4362 | 34 | 16 | 90 | 2 | 208.51 | 57.36204 | The solution given by MO-BxR algorithms is a logical compromise solution, giving highly reasonable Em and Pt values. |

| Algorithm | GD | IGD | Spacing | Spread | Hypervolume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO-BWR | 0.001191 | 0.007834 | 0.014158 | 0.505566 | 0.485711 |

| MO-BMR | 0.001141 | 0.007939 | 0.014292 | 0.502847 | 0.486531 |

| MO-BMWR | 0.001116 | 0.007115 | 0.010523 | 0.509629 | 0.486008 |

| Composite | 0 | 0 | 0.00669 | 0.5 | 0.494054 |

| Solution | Design Variables of TPMS–Fin-Based Three-Fluid Heat Exchanger | ΔP/L (kPa/m) | Qv (kW/m3) | j/f | MO- Algorithm | Normalized ΔP/L | Normalized Qv | Normalized j/f | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (mm) | V (%) | Fs (%) | w (%) | u (m/s) | |||||||||

| 1 | 6.2 | 16 | 57.07753 | 0.198923 | 4 | 3.370284 | 2618.922 | 0.058227 | BWR | 0.287441 | 0.933739 | 0.6772 | 0.632793 |

| 2 | 6.189943 | 16 | 55.59947 | 0.381877 | 4 | 3.190741 | 2559.181 | 0.058363 | BWR | 0.303615 | 0.91244 | 0.678782 | 0.631612 |

| 3 | 6.092302 | 16 | 53.91996 | 0 | 4 | 2.586486 | 2400.657 | 0.069607 | BWR | 0.374546 | 0.85592 | 0.809553 | 0.680006 |

| 4 | 6.19237 | 16 | 50 | 0.15691 | 5.7049 | 3.891346 | 2248.148 | 0.081427 | BWR | 0.248952 | 0.801545 | 0.947024 | 0.66584 |

| 5 | 6.181099 | 16 | 55.52897 | 0.334059 | 4 | 3.173219 | 2547.643 | 0.05924 | BWR | 0.305292 | 0.908326 | 0.688981 | 0.6342 |

| 6 | 6.17198 | 16 | 51.32836 | 0.080601 | 4 | 1.804665 | 2294.072 | 0.076765 | BWR | 0.536807 | 0.817919 | 0.892803 | 0.749176 |

| 7 | 6.098918 | 16 | 50.70768 | 0 | 4.627865 | 2.586217 | 2235.837 | 0.079203 | BWR | 0.374585 | 0.797156 | 0.921158 | 0.697633 |

| 8 | 6.162022 | 16 | 60 | 0.5 | 4.123422 | 4.4364 | 2804.768 | 0.046226 | BWR | 0.218366 | 1 | 0.537624 | 0.58533 |

| 9 | 6.2 | 16 | 59.4362 | 0.5 | 4 | 4.002103 | 2781.814 | 0.048367 | BWR | 0.242062 | 0.991816 | 0.562525 | 0.598801 |

| 10 | 6.161705 | 16 | 56.71883 | 0.117413 | 4 | 3.295474 | 2581.891 | 0.059968 | BWR | 0.293966 | 0.920536 | 0.697448 | 0.637317 |

| 11 | 6.165914 | 15.79119 | 58.10735 | 0.107183 | 5.754128 | 6.191157 | 2632.609 | 0.05695 | BWR | 0.156474 | 0.938619 | 0.662348 | 0.585814 |

| 12 | 6.172786 | 16 | 57.00877 | 0.5 | 4 | 3.575851 | 2644.116 | 0.052995 | BWR | 0.270916 | 0.942722 | 0.61635 | 0.609996 |

| 13 | 6.183259 | 16 | 60 | 0.063757 | 4 | 3.879021 | 2772.239 | 0.051882 | BWR | 0.249743 | 0.988402 | 0.603405 | 0.61385 |

| 14 | 6.183554 | 16 | 52.90909 | 0 | 5.066774 | 3.654421 | 2359.701 | 0.074655 | BMR | 0.265092 | 0.841318 | 0.868263 | 0.658224 |

| 15 | 6.120722 | 16 | 50.27866 | 0.118377 | 4 | 1.684852 | 2240.652 | 0.077492 | BMR | 0.57498 | 0.798872 | 0.901258 | 0.75837 |

| 16 | 6.066616 | 16 | 58.09812 | 0.044971 | 4.037423 | 3.83268 | 2633.314 | 0.055199 | BMR | 0.252762 | 0.938871 | 0.641983 | 0.611205 |

| 17 | 6.2 | 16 | 50 | 0 | 4 | 1.192548 | 2219.604 | 0.084116 | BMR | 0.812342 | 0.791368 | 0.978298 | 0.860669 |

| 18 | 6.190154 | 16 | 52.85742 | 0.160685 | 4 | 2.304569 | 2386.886 | 0.070446 | BMR | 0.420364 | 0.85101 | 0.819311 | 0.696895 |

| 19 | 6.2 | 16 | 53.15572 | 0.010302 | 5.563021 | 4.363295 | 2375.374 | 0.075342 | BMR | 0.222024 | 0.846906 | 0.876253 | 0.648394 |

| 20 | 6.2 | 16 | 50 | 0 | 5.602478 | 3.418884 | 2218.258 | 0.085982 | BMR | 0.283355 | 0.790888 | 1 | 0.691414 |

| 21 | 6.2 | 15.99321 | 52.14251 | 0.499228 | 4 | 2.332668 | 2406.245 | 0.063897 | BMR | 0.4153 | 0.857912 | 0.743144 | 0.672119 |

| 22 | 6.2 | 16 | 60 | 0.212616 | 4 | 4.004891 | 2788.619 | 0.050151 | BMR | 0.241893 | 0.994242 | 0.583273 | 0.60647 |

| 23 | 6.2 | 15.95752 | 60 | 0.040234 | 4.230106 | 4.176677 | 2768.56 | 0.051978 | BMR | 0.231944 | 0.98709 | 0.604522 | 0.607852 |

| 24 | 6.167557 | 16 | 53.14892 | 0.301359 | 4 | 2.589985 | 2418.737 | 0.065566 | BMR | 0.37404 | 0.862366 | 0.762555 | 0.66632 |

| 25 | 6.188564 | 16 | 55.23067 | 0.021331 | 4 | 2.709357 | 2492.568 | 0.067186 | BMR | 0.35756 | 0.888689 | 0.781396 | 0.675882 |

| 26 | 6.2 | 16 | 54.46356 | 0.199081 | 6 | 5.642762 | 2471.769 | 0.069029 | BMWR | 0.171681 | 0.881274 | 0.802831 | 0.618595 |

| 27 | 6.1204 | 16 | 53.04277 | 0 | 4.473147 | 3.000478 | 2357.397 | 0.072335 | BMWR | 0.322868 | 0.840496 | 0.841281 | 0.668215 |

| 28 | 6.2 | 15.67845 | 51.38177 | 0 | 4.519756 | 2.383209 | 2263.453 | 0.078128 | BMWR | 0.406493 | 0.807002 | 0.908655 | 0.707383 |

| 29 | 6.2 | 16 | 50 | 0.35661 | 4 | 1.682621 | 2283.659 | 0.072494 | BMWR | 0.575743 | 0.814206 | 0.84313 | 0.74436 |

| 30 | 6.2 | 16 | 59.01739 | 0.371598 | 6 | 7.001983 | 2735.668 | 0.05424 | BMWR | 0.138355 | 0.975363 | 0.63083 | 0.581516 |

| 31 | 6.188413 | 16 | 50 | 0.341465 | 4 | 1.699269 | 2278.939 | 0.072701 | BMWR | 0.570102 | 0.812523 | 0.845537 | 0.742721 |

| 32 | 6.2 | 16 | 55.07058 | 0.279367 | 4.14633 | 3.219451 | 2519.633 | 0.061694 | BMWR | 0.300908 | 0.898339 | 0.717522 | 0.638923 |

| 33 | 6.2 | 12.18347 | 50 | 0.016611 | 4 | 0.968757 | 1938.147 | 0.071393 | BMWR | 1 | 0.691018 | 0.830325 | 0.840448 |

| 34 | 6.152257 | 16 | 51.27814 | 0.049699 | 4.107913 | 1.955545 | 2282.756 | 0.077288 | BMWR | 0.49539 | 0.813884 | 0.898886 | 0.736053 |

| 35 | 6.2 | 16 | 55.6061 | 0.5 | 4 | 3.189406 | 2576.607 | 0.056525 | BMWR | 0.303742 | 0.918652 | 0.657405 | 0.6266 |

| 36 | 6.2 | 16 | 52.25619 | 0.087803 | 5.17779 | 3.755707 | 2344.212 | 0.074902 | BMWR | 0.257943 | 0.835795 | 0.871136 | 0.654958 |

| 37 | 6.2 | 16 | 60 | 0.08865 | 4.043514 | 3.938987 | 2777.466 | 0.051791 | BMWR | 0.245941 | 0.990266 | 0.602347 | 0.612851 |

| 38 | 6.2 | 16 | 58.71548 | 0.095655 | 4.139944 | 3.842049 | 2700.663 | 0.055216 | BMWR | 0.252146 | 0.962883 | 0.642181 | 0.61907 |

| 39 | 6.2 | 16 | 60 | 0.5 | 5.931302 | 7.193364 | 2804.449 | 0.050751 | BMWR | 0.134674 | 0.999886 | 0.590251 | 0.574937 |

| 40 | 6.2 | 16 | 60 | 0.325578 | 4 | 4.082897 | 2798.409 | 0.0488 | BMWR | 0.237272 | 0.997733 | 0.567561 | 0.600855 |

| 41 | 6.2 | 15.58129 | 58.04361 | 0.190055 | 4 | 3.534836 | 2643.806 | 0.054232 | BMWR | 0.27406 | 0.942611 | 0.630737 | 0.615803 |

| 42 | 6.05961 | 16 | 52.18864 | 0.002852 | 4 | 2.19299 | 2305.01 | 0.074194 | BMWR | 0.441752 | 0.821818 | 0.862902 | 0.708824 |

| 43 | 6.164605 | 16 | 58.97748 | 0.045571 | 4 | 3.691673 | 2705.267 | 0.054793 | BMWR | 0.262417 | 0.964524 | 0.637261 | 0.621401 |

| Method | Design Variables of TPMS–Fin-Based Three-Fluid Heat Exchanger | ΔP/L (kPa/m) | Qv (kW/m3) | j/f | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (mm) | V (%) | Fs (%) | w (%) | u (m/s) | |||||

| Simulation by Wei et al. [2] using NSGA-III + TOPSIS | 6.11 | 11.16 | 51.06 | 0.16 | 4.04 | 2.038 * (1.6024) | 2271 * (1911.11) | 0.1032 * (0.06064) | * The values of ΔP/L, Qv, and j/f were incorrectly reported by Wei et al. [2]. The corrected values are shown in brackets. |

| Composite front + BHARAT | 6.2 | 16 | 50 | 0 | 4 | 1.192548 | 2219.604 | 0.084116 | All the objectives have achieved much better values compared to that of Wei et al. [2]. |

| Algorithm | GD | IGD | Spacing | Spread | Hypervolume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO-BWR | 0.029557 | 0.052289 | 0.070316 | 0.379571 | 0.540129 |

| MO-BMR | 0.054814 | 0.048187 | 0.078348 | 0.400044 | 0.522067 |

| MO-BMWR | 0.063497 | 0.081945 | 0.071403 | 0.5355 | 0.536269 |

| Composite | 0 | 0 | 0.042984 | 0.529144 | 0.576298 |

| Solution | Design Variables | Tmax (°C) | ΔT (°C) | ΔP (Pa) | Normalized Tmax | Normalized ΔT | Normalized ΔP | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Angle (p), (°) | Diversion Length (q) (mm) | Valve Spacing (r), (mm) | Channel Spacing (s), (mm) | ||||||||

| 1 | 48.81473 | 3.83 | 6.966994 | 22.87009 | 19.75851 | 2.619805 | 890.6635 | 1 | 0.961171 | 0.877006 | 0.946059 |

| 2 | 47.95611 | 3.83 | 6.945432 | 23.46677 | 19.75953 | 2.61471 | 882.8612 | 0.999948 | 0.963043 | 0.884757 | 0.949249 |

| 3 | 47.71838 | 3.83 | 6.858289 | 23.64299 | 19.76201 | 2.608944 | 878.5641 | 0.999823 | 0.965172 | 0.889084 | 0.95136 |

| 4 | 46.13899 | 3.83 | 6.976847 | 22.83137 | 19.76571 | 2.632205 | 866.0993 | 0.999636 | 0.956643 | 0.90188 | 0.952719 |

| 5 | 47.21946 | 3.807818 | 6.88513 | 23.44512 | 19.76599 | 2.613263 | 874.0657 | 0.999622 | 0.963577 | 0.89366 | 0.952286 |

| 6 | 47.20109 | 3.83 | 6.720226 | 23.81666 | 19.7666 | 2.602004 | 870.3327 | 0.999591 | 0.967746 | 0.897493 | 0.954943 |

| 7 | 48.81473 | 3.83 | 6.966994 | 22.87009 | 19.75851 | 2.619805 | 890.6635 | 0.99956 | 0.960395 | 0.907049 | 0.955668 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 129 | 43 | 2.33 | 5.340512 | 23.98766 | 20.06175 | 2.555032 | 795.9639 | 0.984885 | 0.985537 | 0.981348 | 0.983923 |

| Method | Design Variables | Tmax (°C) | ΔT (°C) | ΔP (Pa) | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valve Angle (p), (°) | Diversion Length (q) (mm) | Valve Spacing (r), (mm) | Channel Spacing (s), (mm) | |||||

| NSWOA using TOPSIS and LINMAP [39] | 43.017 | 3.83 | 4.4 | 24 | 19.83 | 2.57 | 787.30 | MO-BxR performed better compared to NSWOA in Tmax and ΔP and equal in performance with respect to ΔT |

| MO-BxR with BHARAT | 43 | 3.83 | 4 | 24 | 19.82 | 2.57 | 781.11 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rao, R.V.; Taler, J.; Taler, D.; Lakshmi, J. A Unified Optimization Approach for Heat Transfer Systems Using the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms. Energies 2026, 19, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010034

Rao RV, Taler J, Taler D, Lakshmi J. A Unified Optimization Approach for Heat Transfer Systems Using the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms. Energies. 2026; 19(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Ravipudi Venkata, Jan Taler, Dawid Taler, and Jaya Lakshmi. 2026. "A Unified Optimization Approach for Heat Transfer Systems Using the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms" Energies 19, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010034

APA StyleRao, R. V., Taler, J., Taler, D., & Lakshmi, J. (2026). A Unified Optimization Approach for Heat Transfer Systems Using the BxR and MO-BxR Algorithms. Energies, 19(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010034