1. Introduction

The 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and recent geopolitical and energy-market tensions have exposed structural vulnerabilities in financial systems, particularly through energy-price volatility, inflationary pressures, and the transmission of credit risk. These shocks have highlighted the importance of macro-financial resilience mechanisms that can mitigate systemic risk. In response, two structural transformations, financial digitalization through FinTech and the transition toward renewable energy (RE), have emerged as central components of contemporary economic policy, with potential implications for financial stability. Both are reshaping the structures of contemporary economies, with potential implications for systemic stability [

1,

2,

3]. FinTech restructures financial intermediation by increasing efficiency, transparency, and inclusion, while the development of renewable energy bolsters environmental sustainability and helps diversify economic activity. Despite their distinct domains, limited research has examined how these two dynamic processes may interact to influence financial stability (FST), particularly in developing economies where digital finance and energy transitions are accelerating within heterogeneous institutional environments [

4,

5]. From a macro-financial perspective, the digital transformation of finance and the energy transition are increasingly interconnected. FinTech facilitates the mobilization, allocation, and risk management of capital for large-scale renewable energy investments through digital payments, green lending platforms, and sustainable finance instruments. At the same time, renewable energy deployment can influence financial stability by reducing exposure to fossil-fuel price shocks, improving balance-of-payments dynamics, and lowering long-term inflationary pressures. When combined, these processes may enhance the capacity of financial systems to absorb shocks; however, rapid digitalization and capital-intensive energy transitions may also generate short-run volatility if regulatory and institutional frameworks lag behind.

Financial stability refers to the ability of the financial system to allocate resources efficiently, absorb shocks, and regain confidence in its institutions. Stability depends on striking a balance between innovation and caution. Technological innovations such as mobile banking, blockchain, and digital loans expand financial access while reducing transaction costs. However, they also bring increased risks: cyber risk, operational fragility, and market concentration are all new forms of vulnerability [

6]. Similarly, demand for green projects reshapes investment patterns and channels credit into new arenas. Thus, carbon markets, as well as green bonds, have emerged to fill the gaps left by conventional emissions-trading mechanisms [

6]. The overall result could be an improved long-run stability thanks to sustainable growth. But the same developments can also transmit high-frequency instability through speculative investment behavior and policy uncertainty [

7]. As such, whether the growth of FinTech and renewables contributes to or undermines macro-finance stability remains a high-policy-relevance open question. However, these effects are unlikely to be uniform over time. Recent evidence suggests that FinTech innovations may initially trigger market turbulence, abrupt adjustments in credit allocation, and operational vulnerabilities due to rapid digital adoption and insufficient regulatory preparedness [

8,

9]. Only after a period of institutional learning and technological consolidation do FinTech systems begin to enhance efficiency, reduce information asymmetry, and stabilize financial intermediation. Therefore, a proper empirical assessment must account for this temporal pattern: short-run destabilization versus long-run stabilization. Our empirical strategy explicitly incorporates these transitional dynamics through the ARDL framework and quantile-based heterogeneity.

From a theoretical perspective, Joseph Schumpeter’s Innovation theory posits that technological change is the primary driver of economic development and that financial innovation facilitates rational behavior in saving, investment, and entrepreneurship [

10]. This process is illustrated by FinTech democratizing financial services and raising capital for sustainable, productive industries, such as those related to renewable energy [

11,

12]. Endogenous growth theory assumes rationality about the effect of technological innovation, such as the introduction of new technologies in energy use [

13]. Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis posits that innovation, when it becomes excessive or inadequately regulated, can generate leverage and speculative behavior, ultimately leading to systemic risk [

14].

The BRICS economies—Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa offer an ideal setting in which to study the interaction between renewable energy and FinTech. The five countries combined represent a third of global GDP and form the most vibrant cluster of emerging markets currently undergoing simultaneous financial digitization and electrical energy transformation. Over the past decade, the vast majority of FinTech ecosystems in BRICS countries have been driven by open banking frameworks, innovation-friendly regulations, and digital payment networks [

15]. China stands as a world leader in digital finance and green energy technologies. India and Brazil have made commendable progress in popularizing mobile payments. Meanwhile, Russia and South Africa are, in turn, incorporating digital platforms into their own banking and investing spheres. At the same time, these countries are at the forefront of deploying renewable energy because growing energy consumption, commitments to reduce carbon emissions, and a quest for sustainable growth models coincide [

16,

17]. But the rapid pace of financial innovation and divergent development of regulatory and institutional frameworks raise questions about potential trade-offs in stability. The interrelationship among FinTech, renewable energy, and financial stability has received little study. Previous studies have primarily investigated the factors that influence the development of financial facilities, the role of green finance in mitigating carbon emissions, and the impact of financial technology on credit availability [

1,

8].

Few studies have explored the confluence or symbiotic effects of digital financial transformation and renewable energy development on systemic stability in developing economies. Nguyen and Dang [

18] analyzed 147 countries using quantile regression and concluded that renewable energy consumption tends to reduce financial stability, particularly in economies with already high financial resilience. This instability arises from the capital-intensive nature of renewable projects, which increases banks’ exposure and systemic risk. However, strong institutional quality can mitigate these negative effects by improving risk management and governance. Similarly, Imran et al. [

19] examined South Asian economies using a panel ARDL model. They found heterogeneous outcomes: renewable energy enhances financial stability in India and Bangladesh, remains insignificant in Nepal, and negatively affects Pakistan due to high import dependence and fiscal burdens. In contrast, Kirikkaleli [

20] demonstrated that in Ireland, renewable energy and financial stability are complementary, as financial soundness facilitates green investment and emission reduction. Moreover, the study [

21] confirmed a bidirectional relationship, suggesting that stable financial systems attract renewable energy investment, which in turn supports long-term resilience. In addition, the relationship between renewable energy expansion and financial stability remains theoretically and empirically ambiguous. While renewable energy may reduce exposure to fossil-fuel price volatility and support long-term macroeconomic resilience, several studies highlight that large-scale RE deployment can generate short-run financial stress due to high capital intensity, policy uncertainty, and technology-related risks. Consequently, assuming a uniformly positive effect of RES on financial stability would be overly optimistic. The relationship must be empirically validated and tested for potential spuriousness, especially because RES may proxy for broader structural factors, such as institutional quality, environmental policy, or technological capabilities that themselves influence financial stability. By focusing attention on the BRICS bloc and adopting a macro-financial approach, this study bridges a key gap in current understanding. It deepens our understanding of how technology-driven structural changes and sustainability impact the resilience of financial systems.

Based on balanced panel data, this analysis covers the period 2012–2022 and integrates data from various indicators on RE, FinTech, and financial stability. This approach enables the evaluation of both direct and interactive effects of FinTech and renewable energy on macro-financial resilience, while also controlling for differences in structure and institutions among BRICS member countries. We begin our analysis with a question: how do the digitalization of finance and the transition to clean energy together create systemic risk in emerging economies? As financial FinTech expands, sensitive systems become increasingly linked and driven by data, offering potentially improved risk management but also exposing themselves to cyber threats and the spread of market crises. Similarly, the transition to renewable energy involves significant financial appropriations. Digital finance channels and green financing tools often facilitate these financial flows. The interdependent processes presented in these circumstances reveal whether FinTech and renewable energy are complementary, enabling a more stable financial system, or whether alternative forces of destabilization introduce new systemic risks. The results will have far-reaching implications for asset management, the development of green finance regimes, and the advancement of digital technology and environmental protection strategies in emerging countries. This study makes several significant contributions to the current literature on financial stability, financial technology, and RE within emerging economies. First, it offers a novel research perspective by jointly examining the interactive effects of FinTech and RE on banks’ z-score in the BRICS economies.

While prior studies have tended to analyze these dimensions separately, this paper provides the first comprehensive empirical evidence on how digital financial transformation and the clean energy transition interact to influence macro-financial resilience. Second, the study advances theoretical understanding by integrating Schumpeter’s innovation theory and Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis to explain the dual role of FinTech as both a stabilizing and destabilizing force. In parallel, it conceptualizes renewable energy as a long-run stabilizer that mitigates the cyclical volatility induced by rapid digitalization, offering a unified framework for technological and ecological transitions. Third, methodologically, the study employs both Panel Quantile Regression (PQR) and Panel Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) models to capture heterogeneous effects across quantiles and time horizons. This dual approach enables a more robust analysis of asymmetric short-run dynamics and long-run equilibrium relationships, while addressing cross-sectional dependence and structural heterogeneity among BRICS members. These techniques provide a more rigorous empirical framework capable of identifying nonlinear, time-varying, and quantile-specific interactions that conventional estimators would miss. Fourth, the empirical results reveal a nonlinear and asymmetric relationship: FinTech has short-term destabilizing effects that transform into long-term benefits as regulatory and institutional frameworks mature, while renewable energy gradually enhances systemic resilience by reducing dependence on volatile fossil fuel markets. Finally, the study provides valuable policy implications by demonstrating that institutional quality and governance effectiveness amplify the stabilizing effects of both FinTech and renewable energy. Hence, the findings underscore the importance of integrated policy design that aligns financial innovation, clean energy investment, and institutional reform to foster a more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable financial system in emerging economies. Following the introduction, the data and empirical techniques employed in the study are presented in

Section 2. The experimental results are presented in

Section 3. The study is concluded with policy implications in

Section 4.

3. The Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics show substantial variability in BRICS economies (

Table 1). Although a value of 15.68 for FST exists, moderate changes in the standard deviation (SD) of approximately 5.33 are expected. FinTech exhibits a mean of 0.91 and a range of −0.27 to 2.01, underscoring varying levels of adoption of digital finance technologies, with China and India as the leading countries. GDP and IND highlight the structural asymmetries in production and income between China and other countries of the bloc. Among all the statistical results, the INR average of 3.40 suggests that the interest rate is moderately high, with slightly higher kurtosis at 5.16. Institutional governance indicators, with a lower value of −0.21, confirm the need for quality institutions to provide support and stability for innovation. The ROA and ROE of bank performance undergo significant changes. Although most variables exhibit moderate skewness and kurtosis, the Jarque–Bera test indicates that several variables (GDP, RE, ROE, and INR) deviate from normality at the 5% level. This supports our use of quantile-based estimation methods that do not rely on normality assumptions.

3.2. CSD Test

The results of the CSD tests [

28,

31,

32] show

p-values of 0.00, indicating strong statistical significance (

Table 2). This confirms the presence of CSD among the BRICS economies, meaning that financial stability, FinTech, and renewable energy indicators are interconnected across countries. Consequently, shocks or policy changes in one BRICS member are likely to influence others, justifying the use of econometric techniques that account for such interdependence, such as Panel ARDL and Panel Quantile Regression models.

3.3. Unit Test Root

Table 3 presents the first-generation Fisher–ADF and second-generation CIPS panel unit root tests. The Fisher–ADF statistics show that all variables, except renewable energy (RE), are non-stationary at levels but become stationary after first differencing, confirming their integration order of I(1). In contrast, RE is stationary in levels, and is therefore classified as I(0). The second-generation CIPS results, which account for cross-sectional dependence, support these findings: all variables have CIPS statistics below the 5% critical value (–2.52) in first differences, while RE is stationary in levels. Overall, the panel contains a mix of I(0) and I(1) variables, validating the use of the Panel ARDL approach for further analysis.

3.4. The Effect Results Using the Panel ARDL

In the panel ARDL model reported in

Table 4, the focus of interpretation and discussion is on both the short and long run. The results from the ARDL model provide valuable insights into the short- and long-run dynamics linking financial technology (FinTech) and RE, considering micro- and macro-variable determinants of financial stability in the BRICS economies. The model exhibits high explanatory power, with R

2 = 0.95 and Adjusted R

2 = 0.93, indicating that approximately 93% of the variation in financial stability is explained by the included variables. The Durbin–Watson statistic (2.45) confirms the absence of serial correlation, and the significant F-statistic of approximately 53.16 indicates a strong joint significance of the regressors. The significant coefficient for the lagged dependent variable, lagged FS, is 0.6, suggesting strong persistence in financial stability. This suggests that shocks to stability tend to be partially sustained over time and to converge with the long-run equilibrium.

The most remarkable conclusion pertains to the development of FinTech and its impact on financial stability. The current size of FinTech has significant negative short-run implications for financial stability (−6.22 at 5%), while its lagged value carries the opposite effect and is slightly larger (6.73). This pattern of movement in time suggests that, in the short term, a proliferation of FinTech products may trigger sharp adjustments and market turbulence. However, the positive coefficient of the lagged term indicates that, after an initial period of adaptation, a mature financial system emerges, characterized by efficiency, inclusivity, and risk aversion. Economically speaking, this type of cycle suggests that while FinTech innovation may, due to the reshaping of the financial system, temporarily increase both complexity and volatility in financial markets, once regulatory frameworks and technological infrastructures are established, In the BRICS context, these findings align with the digital transformation paths of countries such as China and India, where improvements followed the initial proliferation of FinTech platforms, leading to increased financial inclusion, expanded credit channels, and enhanced supervisory capacity. Thus, the model reflects the nonlinear and transitional effects of FinTech at the beginning, which are disruptive, and thereafter stabilize as digital systems solidify.

In addition to

Table 3, the RE coefficient shows a similar pattern in short-term adjustments. The current coefficient only shows positive values (0.44,

p < 0.01). It means that using renewable energy in the short term to break the cycle of resource constraints, such as dependence on coal or oil, can improve financial stability and reduce volatility. The overall interpretation suggests that renewable energy indeed serves as a structural stabilizer for financial systems, particularly during economic transitions toward sustainable growth models. However, evidence from advanced economies, particularly in Europe, shows that an accelerated, unbalanced deployment of renewable energy sources can destabilize energy systems and the broader economy. The rapid expansion of intermittent renewable technologies, combined with insufficient grid flexibility, storage capacity, and policy coordination, has increased energy price volatility, fiscal burdens, and supply insecurity in several European countries. These imbalances have, in some cases, translated into macroeconomic pressures and financial stress, challenging the assumption that renewable energy expansion is unambiguously stabilizing. These results aligned with [

19,

20]. Estimates of economic growth coefficients indicate a positive short-run effect of 0.15, followed by a lagged negative effect of about −0.16. This cyclical pattern suggests that periods of rapid economic expansion positively affect stability by boosting profitability and reducing default risk; however, this effect tends to diminish as credit extension accelerates in subsequent periods. The result reflects the procyclical nature of financial stability, where strong growth initially increases stability [

33,

34]. The industrial value-added variable has a positive current coefficient of 0.62, indicating that industrial expansion reinforces financial stability by generating sound income flows from production and employment [

35,

36]. The interest rate coefficient is −0.10 and is statistically insignificant, indicating that monetary policy’s impact on short-term stability is minimal. This may indicate the presence of offsetting channels: on the one hand, raising interest rates will lower inflationary pressures, but on the other hand, they will increase borrowing costs and potential default risk. The institutional governance coefficient of 5.48 is highly significant and substantial in magnitude, confirming the enormous importance of institutional quality to systemic stability [

37]. Profitability indicators also offer banks insights. The coefficient of Return on Assets is negative about −3.33, indicating that higher short-term profitability does not necessarily lead to greater systemic stability. In contrast, the Return on Equity is positive about 0.3, suggesting that well-capitalized banks with efficient equity deployment contribute to financial system stability.

3.5. The Panel QR Results

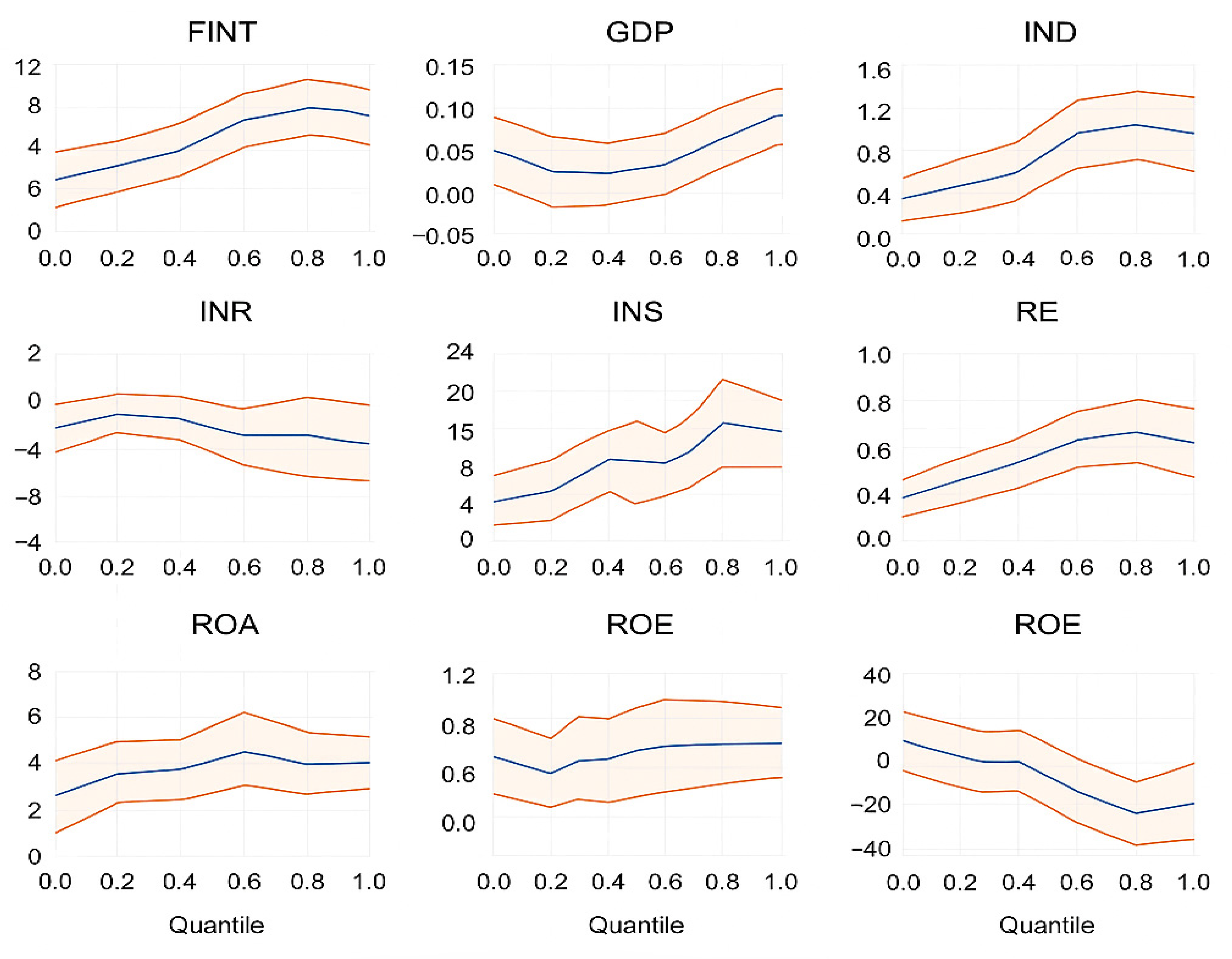

This section employs a panel QR, as shown in

Table 4. The data estimates from the quantile process showed that the impacts of financial technology and renewable energy on financial stability varied across BRICS nations (

Figure 1). The associated coefficient for these two variables increases smoothly from the lower quartile to the upper quartile, indicating that their contribution to financial stability strengthens as a resilient financial system emerges. In the case of FINT, the estimated coefficient for the lower quantile (0.1) is approximately 1.8, indicating a weak but positive effect in less stable environments. However, as breakdowns in stability increase, FINT’s effect becomes very marked, reaching approximately 4.5 at the median quantile (0.5) and approaching 9.0 at the upper quantile (0.9). This rising pattern demonstrates that the spread of FinTech innovation plays a crucial role in stabilizing mature financial systems by enhancing operational efficiency, promoting credit allocation, and managing risks. The findings also reveal that institutional strength influences the benefits of FinTech. Developing countries, such as China and India, with more comprehensive regulations and technical frameworks than their neighbors, Brazil and Russia, are likely to enjoy the most substantial stabilizing effects from the digital age. RE exhibits a similar, though less steep, upward trajectory across quantiles, indicating that its contribution to financial stability is gradual and continuous. At the lower quantile (0.1), it is approximately 0.25, indicating that when the economy remains in its early stage of energy transition, relying heavily on fossil fuels, a significant renewable resource allocation has only a modest impact; therefore, this effect is small. At the median quantile (0.5), the coefficient is approximately 0.55, indicating that as RE deployment becomes more intensive, these benefits are realized through regulation, with improved energy security, savings, and reduced injury from oil price downturns. At the upper quantile (0.9), the coefficient approaches 0.9, indicating that renewable energy expansion significantly enhances system resilience once clean energy becomes a substantial part of the energy mix. From a macroeconomic perspective, partial profits generated through renewables will mitigate the impact on the balance of payments. This is critically important for energy-importing economies, such as India or South Africa; in this case, the development of RE directly moderates the macroeconomic vulnerability associated with external energy price shocks. The industrial value added, regulation quality, and ROE exhibit a positive effect, while ROA and INT indicate an adverse effect across different quantiles, confirming the panel ARDL results.

Table 5 presents the Panel Quantile Regression estimates and highlights the heterogeneous effects of FinTech, renewable energy, and the control variables across the financial stability distribution. The effect of FinTech (FINT) increases monotonically from Q0.10 (1.80) to Q0.90 (9.00), suggesting that FinTech contributes only modestly to stability in less resilient financial systems but becomes a strong stabilizing force in more mature and robust ones. This supports the argument that digital financial innovations yield greater benefits when regulatory and technological infrastructures are well established. Renewable energy (RE) shows a similar but more gradual upward pattern, moving from 0.25 at the lower quantile to 0.90 at the upper quantile. This implies that the stabilizing effects of renewable energy expand as economies progress further in their energy transition. In lower-stability environments, RE investments only marginally reduce systemic risk, but in higher-stability contexts, they significantly enhance resilience by improving energy security and reducing exposure to fossil-fuel price shocks.

The control variables also display meaningful heterogeneity. GDP exhibits a rising positive effect across quantiles, indicating that economic expansion reinforces financial stability more strongly when the financial system is already robust. Industrial value added (IND) is consistently positive and increasing, reflecting the role of industrial development in providing stable cash flows, employment, and productive capacity—factors that support macro-financial resilience. Institutional quality (INS) is strongly positive across all quantiles. It becomes particularly influential at the upper end of the distribution, underscoring the importance of governance structures in amplifying the stabilizing effects of both FinTech and renewable energy. Profitability indicators exhibit asymmetric behavior: ROE strengthens financial stability across all quantiles and becomes more influential at higher levels. At the same time, ROA displays a consistently negative effect, echoing the ARDL results that short-term asset-driven profitability may reflect risk-taking behavior. The interest rate (INTRS) shows mild negative effects at all quantiles, suggesting that monetary tightening slightly reduces stability, though the magnitude is small. Overall, the PQR findings reinforce the nonlinear, quantile-specific nature of financial stability determinants and complement the ARDL results by illustrating how FinTech, renewable energy, and structural factors exert differentiated impacts across financial system conditions.

Beyond FinTech and renewable energy, the PQR results reveal heterogeneous effects of the control variables across the financial stability distribution. GDP shows a positive, increasing impact across the lower to upper quantiles, indicating that economic expansion contributes more strongly to financial resilience in already stable systems. Industrial value added (IND) shows a consistently positive effect across all quantiles, aligning with ARDL findings and suggesting that structural production capacity remains a key stabilizing factor. Institutional quality (INS) becomes more influential in higher quantiles, reinforcing the view that strong governance enhances systemic robustness, particularly in financially mature economies. Profitability indicators exhibit asymmetry: ROE shows a rising positive effect across quantiles, while ROA remains negative across the distribution, echoing the short-run ARDL interpretation that asset-based profitability may entail higher risk exposure. Interest rates (INTRS) show a mild negative effect across all quantiles, with the magnitude remaining small, consistent with limited short-run monetary transmission in BRICS. These results confirm the heterogeneous and nonlinear architecture of financial stability determinants and complement the ARDL findings by illustrating how structural, institutional, and profitability dynamics vary across different states of financial resilience.

The heterogeneous effects identified in this study are consistent with an emerging body of recent global and regional evidence. For instance, several cross-country studies confirm that FinTech adoption produces nonlinear stability responses, initially raising short-term operational and credit risks while improving long-run intermediation efficiency [

38,

39]. Similar patterns have been documented in Europe and the MENA region, where FinTech-enabled credit expansion improved inclusion but required stronger supervisory oversight to preserve stability [

2]. Parallel findings emerge in renewable-energy finance: recent analyses show that steady increases in renewable capacity reinforce macro-financial resilience by reducing energy-price volatility and sovereign risk, though the magnitude depends on institutional governance and capital-market depth [

40,

41]. Country-specific work from emerging Asia and Latin America also supports the view that the interaction between clean-energy investment and financial-system quality determines whether renewable energy exerts stabilizing or destabilizing effects [

19]. Collectively, this new evidence is aligned with the results observed for BRICS economies, reinforcing the conclusion that technological innovation and energy transition strengthen financial stability when supported by sound institutions, effective regulatory capacity, and sustainable investment frameworks [

42].

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study provides empirical evolutionary evidence on the dynamic and asymmetric impacts of financial technology and renewable energy on financial stability in BRICS economies from 2012 to 2022. Using a mix of PQR and panel ARDL models, the findings suggest that FinTech and renewable energy jointly strengthen the structural foundations of economic development, and their effects complement one another across different time horizons. The PQR estimates suggest that as the distribution of financial stability becomes richer. The ARDL results, meanwhile, make explicit both the short-run adjustment dynamics and the long-run equilibrium relationships among technological, structural, and institutional determinants of stability. From a policy perspective, these findings have several implications. Pilot regulatory programs and supervisory technologies can help manage innovation-induced volatility, while also accelerating the safe implementation of digital finance. The second implication is that to maintain macroeconomic and financial stability and achieve sustainable development, policy support for clean energy must be consistent with the financial sector’s strategy through means such as issuing green bonds, implementing carbon pricing, and establishing climate disclosure standards. By enticing private capital into innovation investment, such as through FinTech financing platforms, the funding side can diversify and thus improve the resilience of sustainable finance. In the short term, reducing adjustment costs and protecting against digital and energy shocks are crucial. On the other hand, policy objectives in the longer run should aim to shape a comprehensive system where economic innovation is in tune with environmental sustainability, alongside other dimensions such as quality upgrading and institutional reform. This study has several limitations. Although the PQR and Panel ARDL approaches address heterogeneity and dynamics, time-varying effects cannot be entirely excluded. Third, the dataset ends in 2022 and does not reflect more recent shocks. Finally, using aggregate national data may mask significant differences within a country. Future work could address these issues by employing instrumental-variable quantile methods and finer-grained datasets. Although our findings point to a stabilizing long-run effect, RES may also reflect deeper structural characteristics of BRICS economies. Future research could incorporate alternative measures of the energy transition, apply instrumental-variable quantile regressions, and explore potential endogeneity between RES expansion and financial stability.