Near-Field Shock Wave Propagation Modeling and Energy Efficiency Assessment in Underwater Electrical Explosions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- (2)

- Experimental measurement and theoretical calculation of shock wave energy and utilization rates across capacitive energy storage parameters from 13 J to 100 J;

- (3)

- Development of an acoustic energy calculation model incorporating water surface and seabed reflection losses with established model selection criteria.

2. Numerical Calculation Model

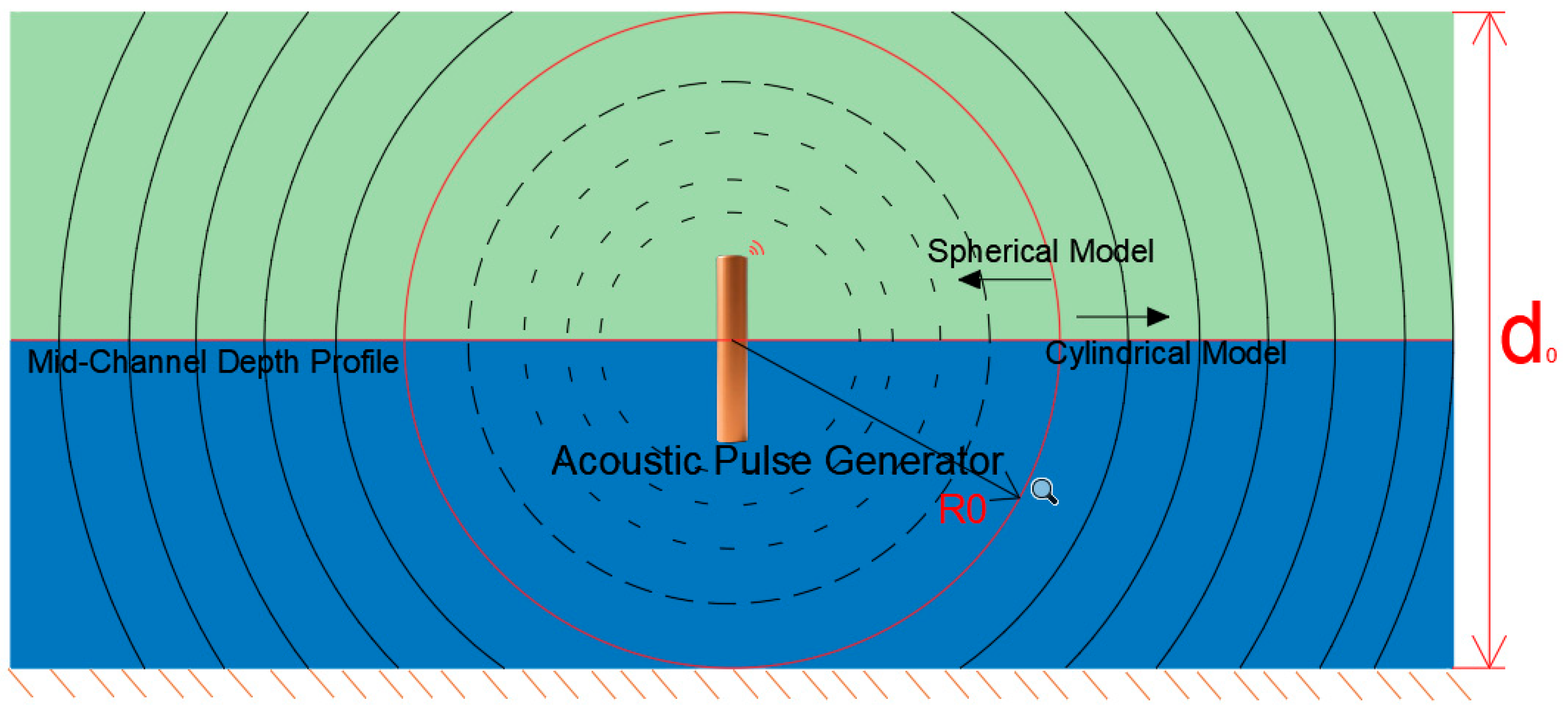

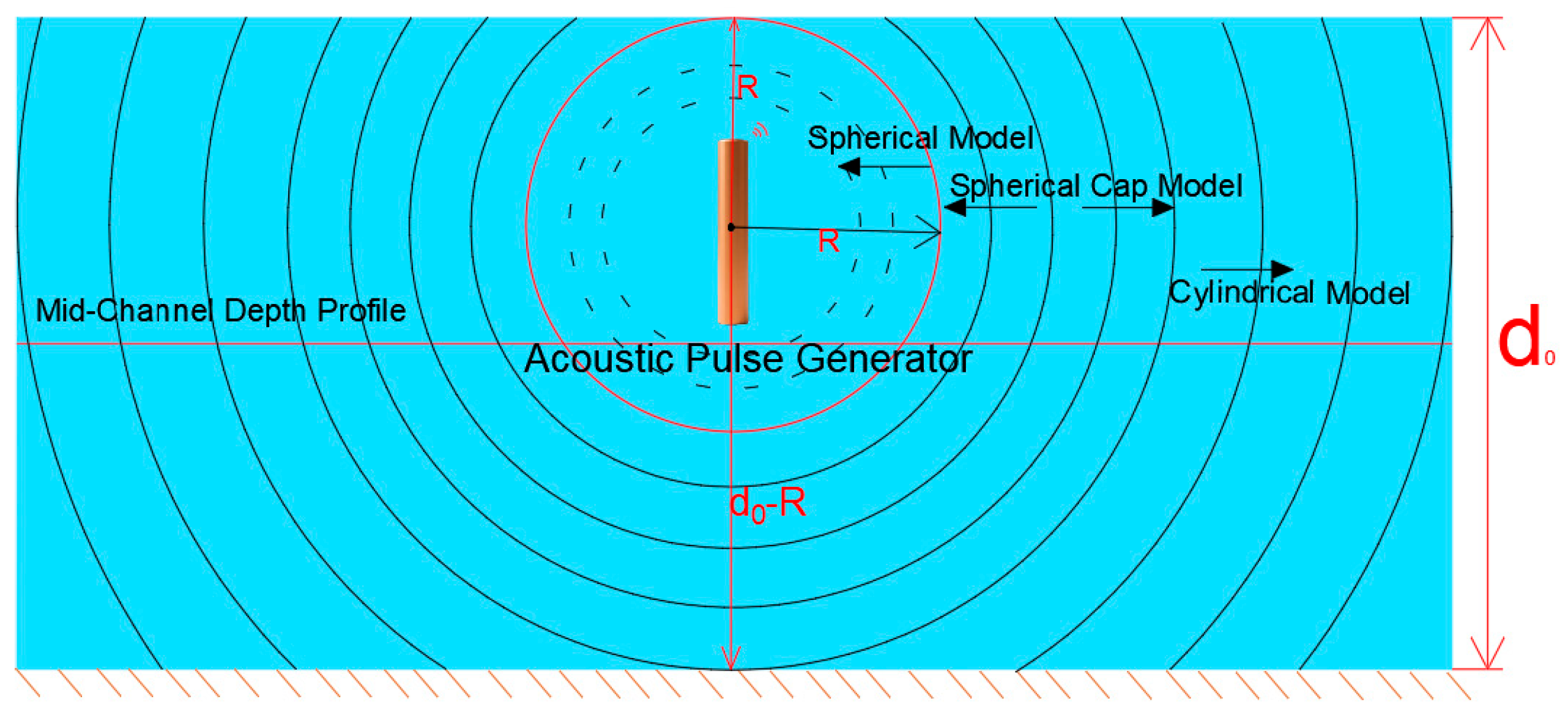

2.1. Mid-Water Wave Propagation Model

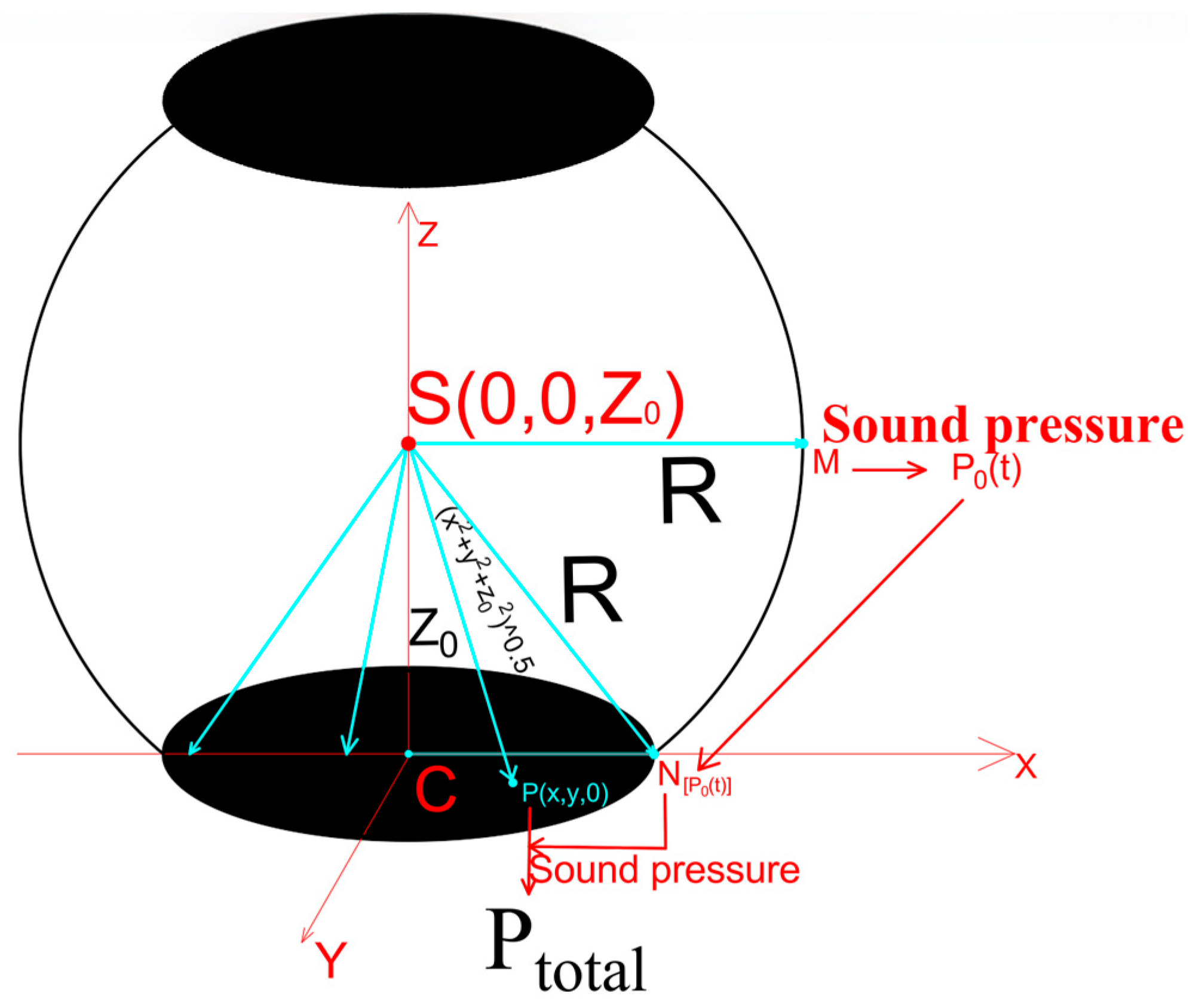

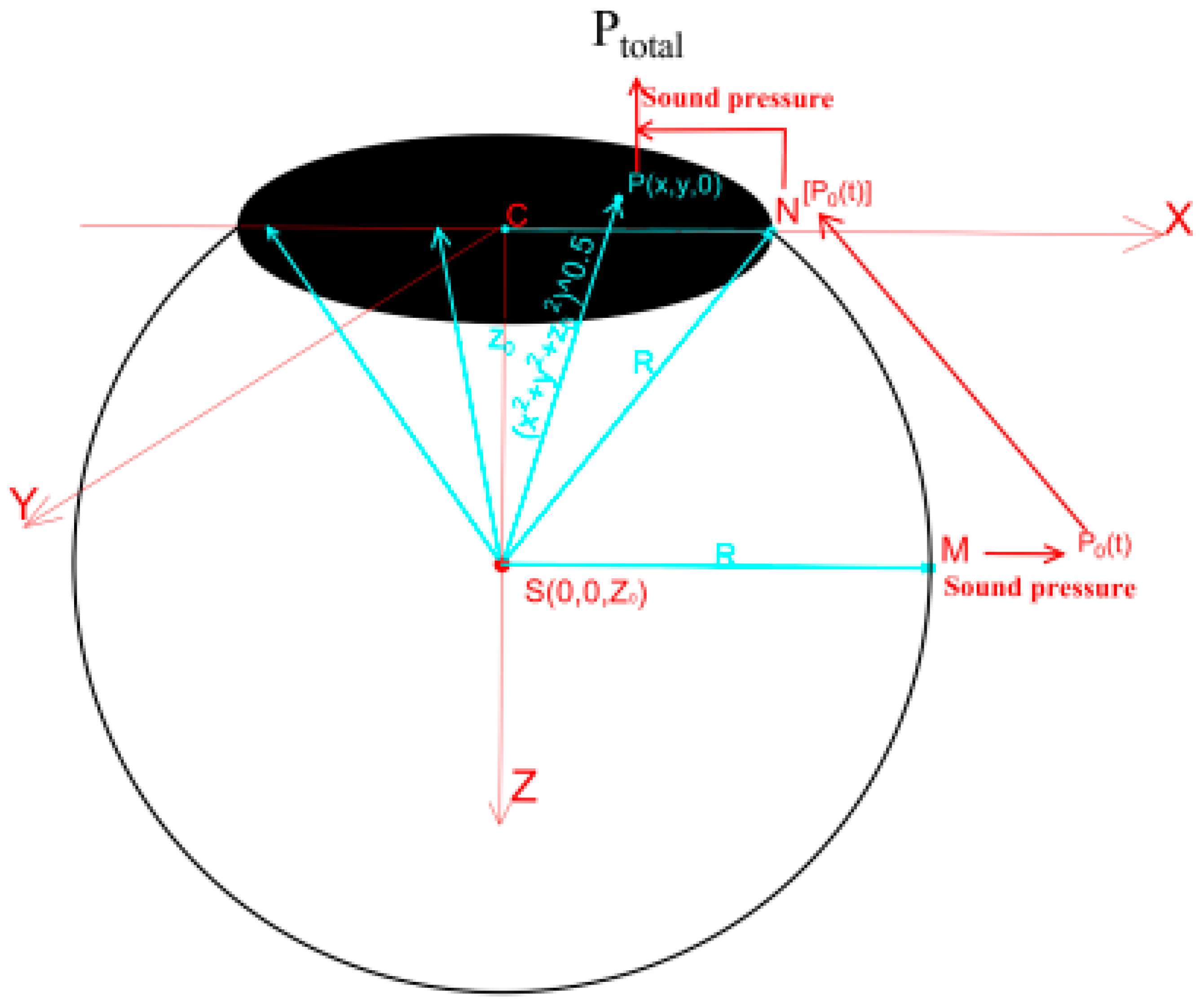

2.1.1. Cartesian Coordinate Integration

2.1.2. Spatial Integration Component

2.1.3. Temporal Integration Component

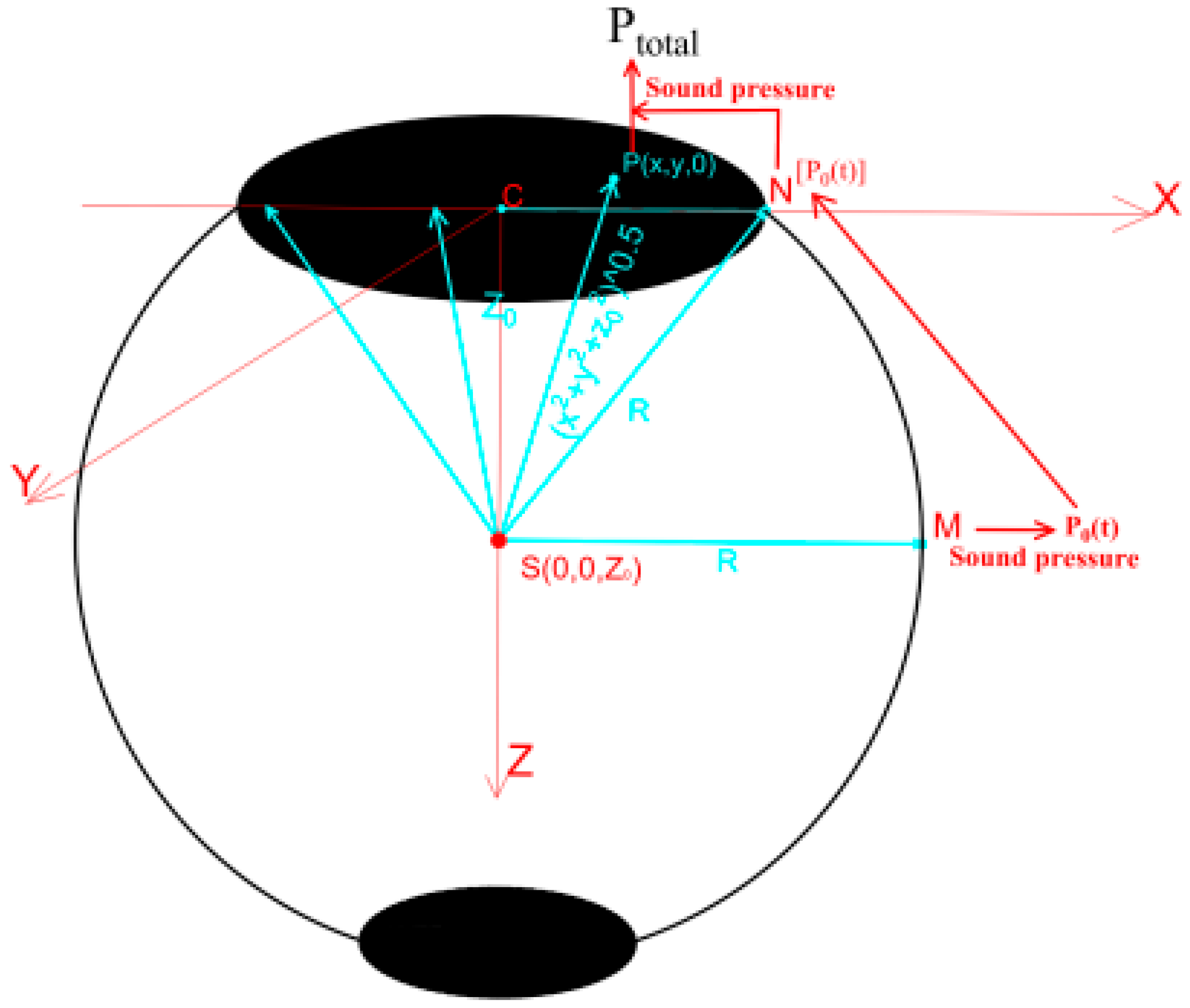

2.2. Upper-Half Space Propagation Model

2.3. Lower-Half Space Propagation Model

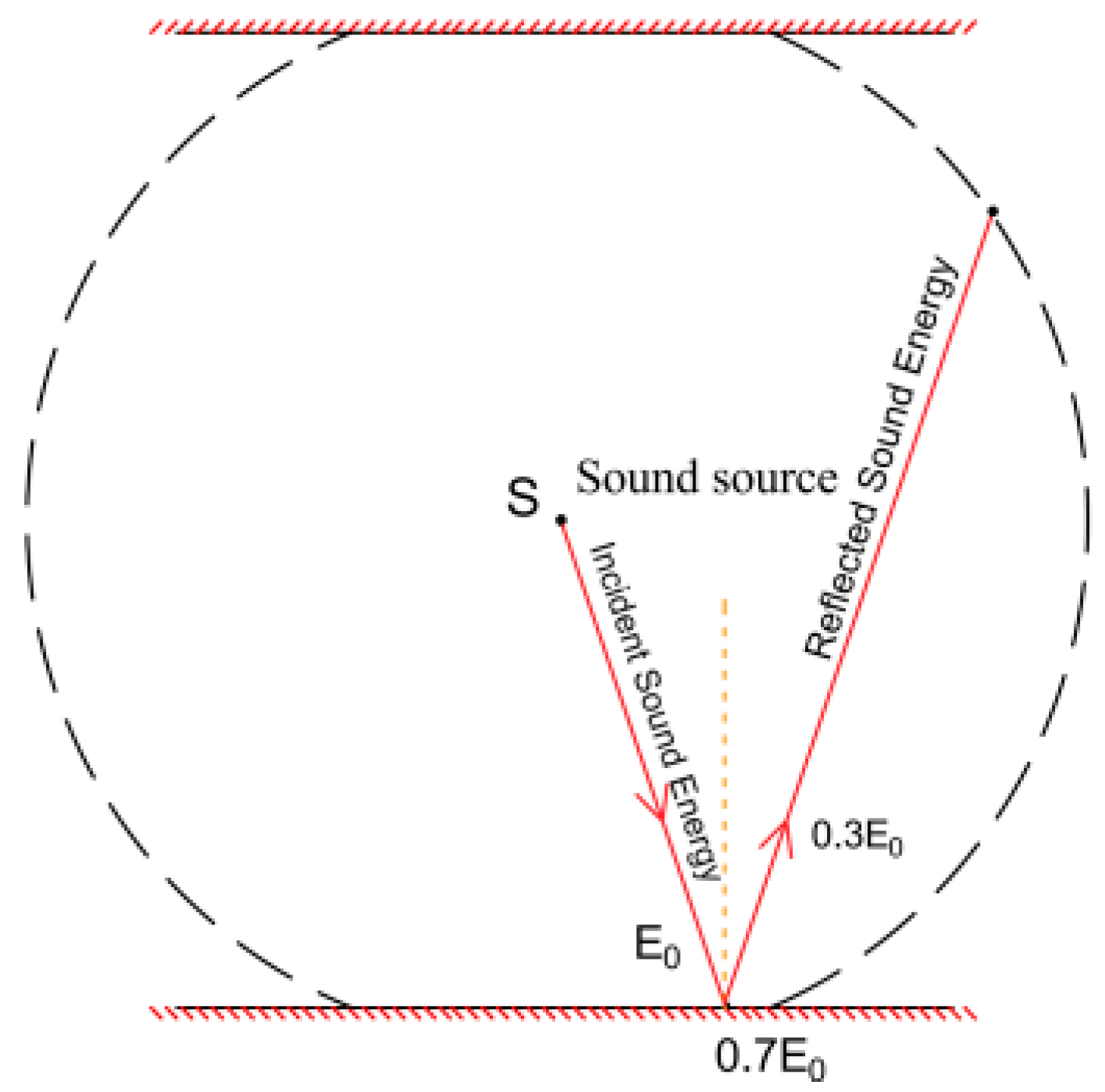

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Reflection Coefficient

2.5. Energy Balance Analysis

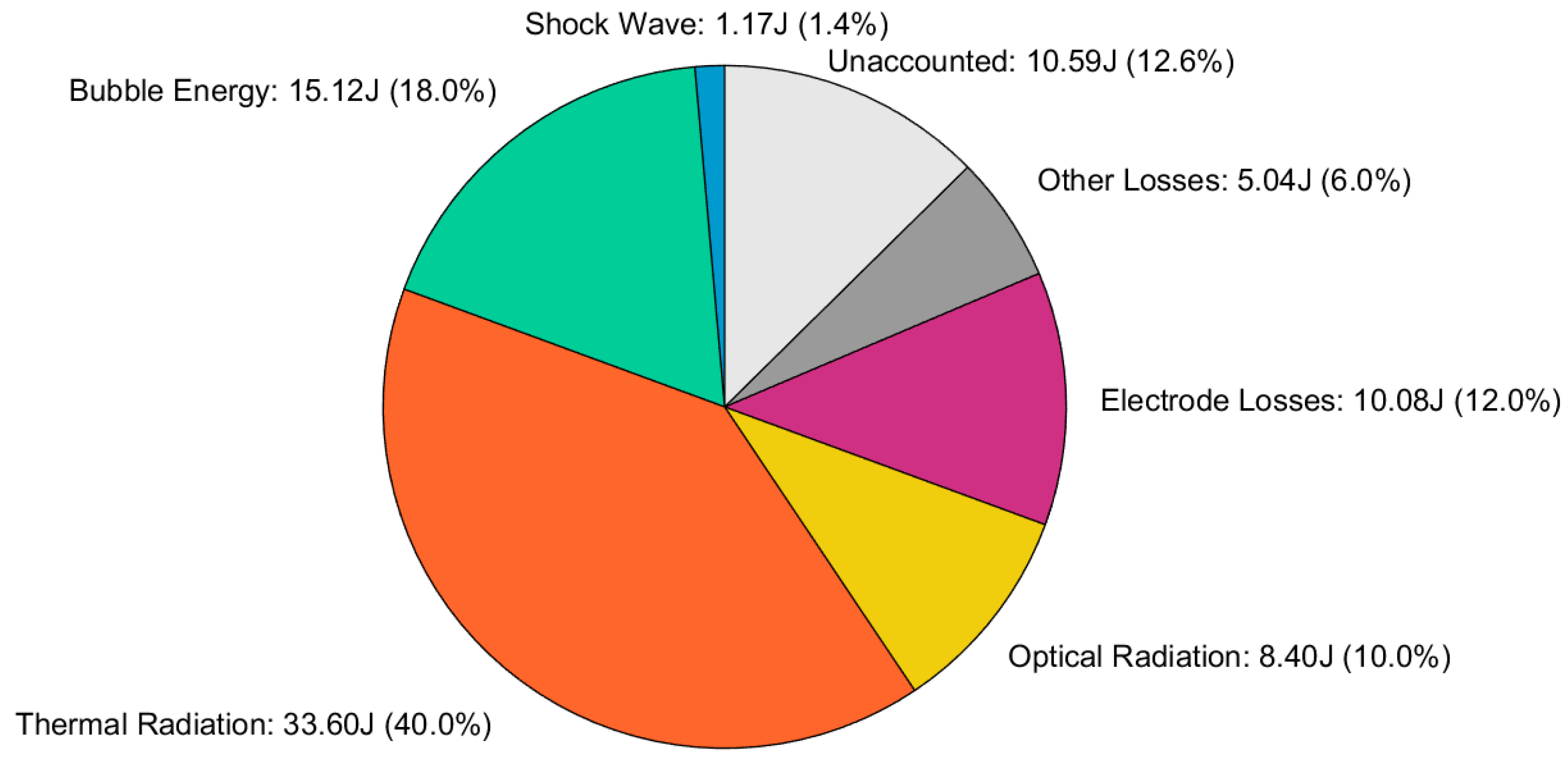

2.5.1. Energy Distribution Model

2.5.2. Estimation Methods for Energy Components

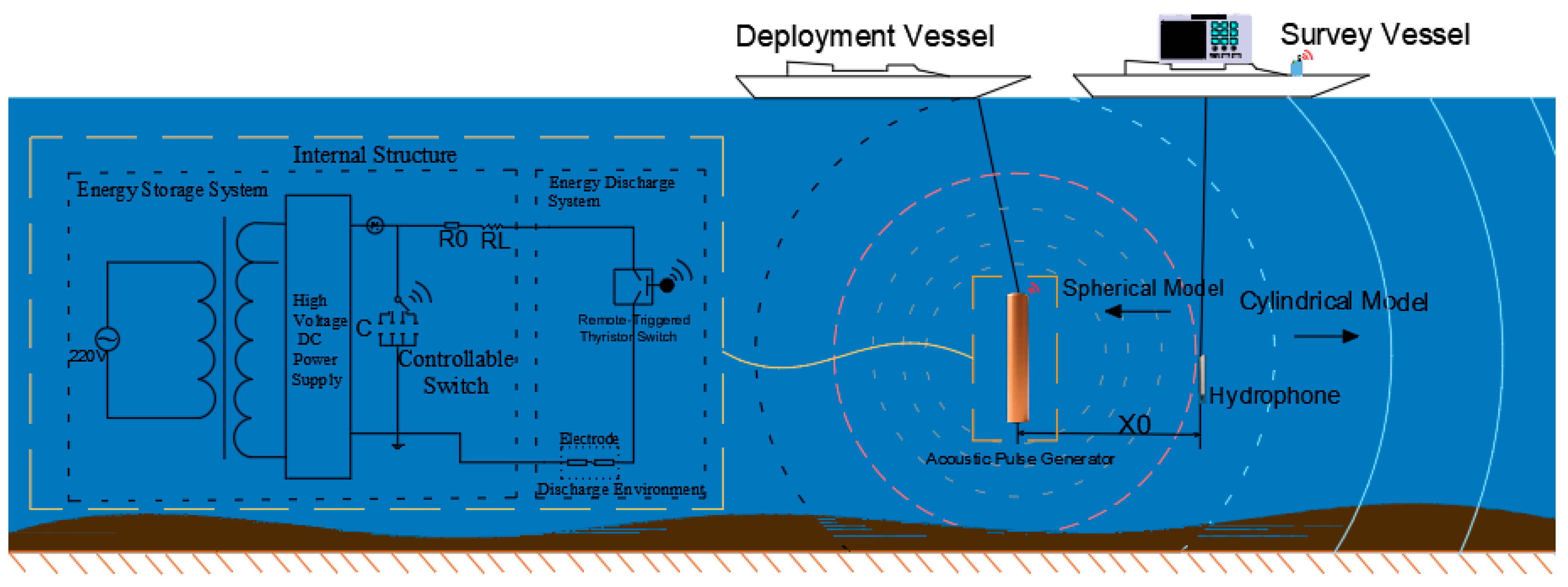

3. Electrode Experiments

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.1.1. Experimental Conditions

3.1.2. Environmental Parameters

3.2. Experimental Protocol

3.3. Experimental Results

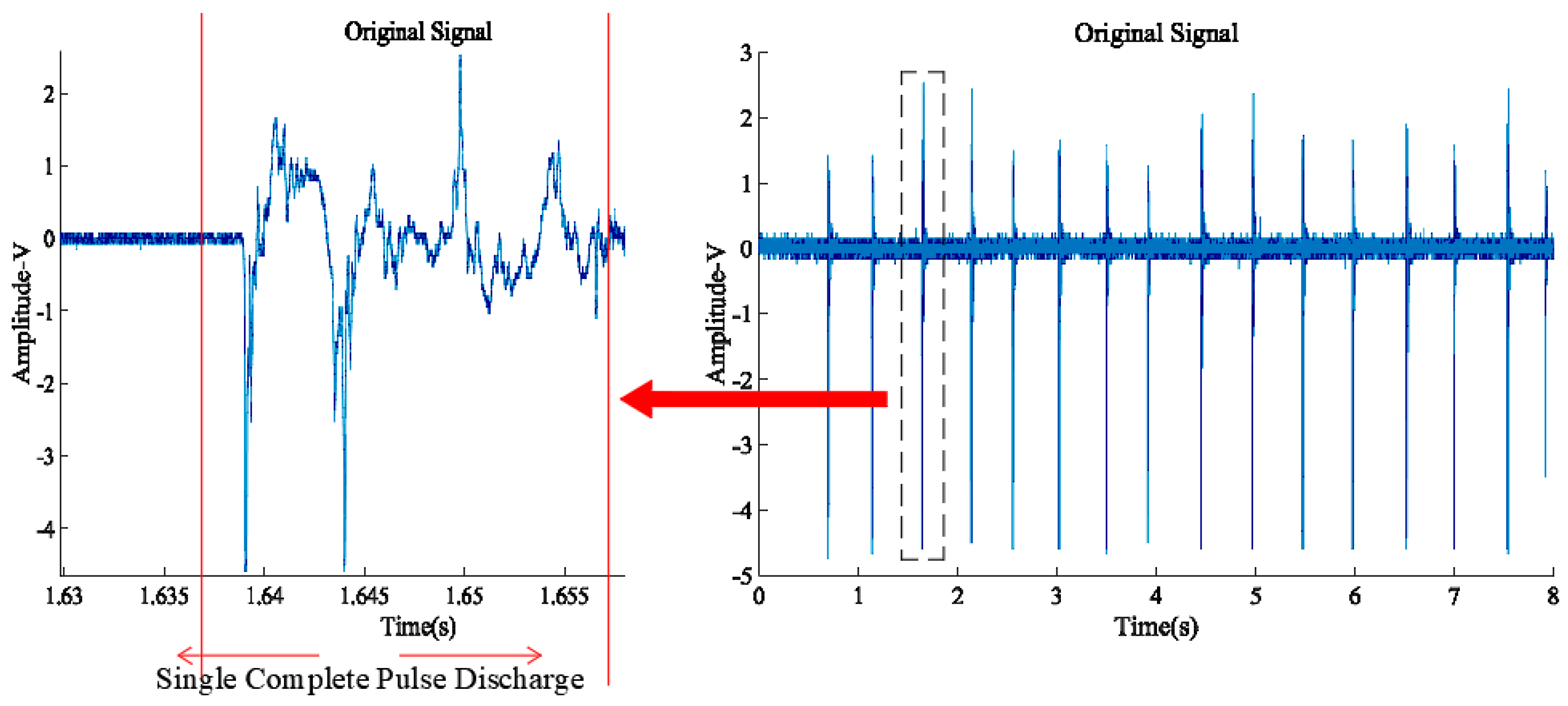

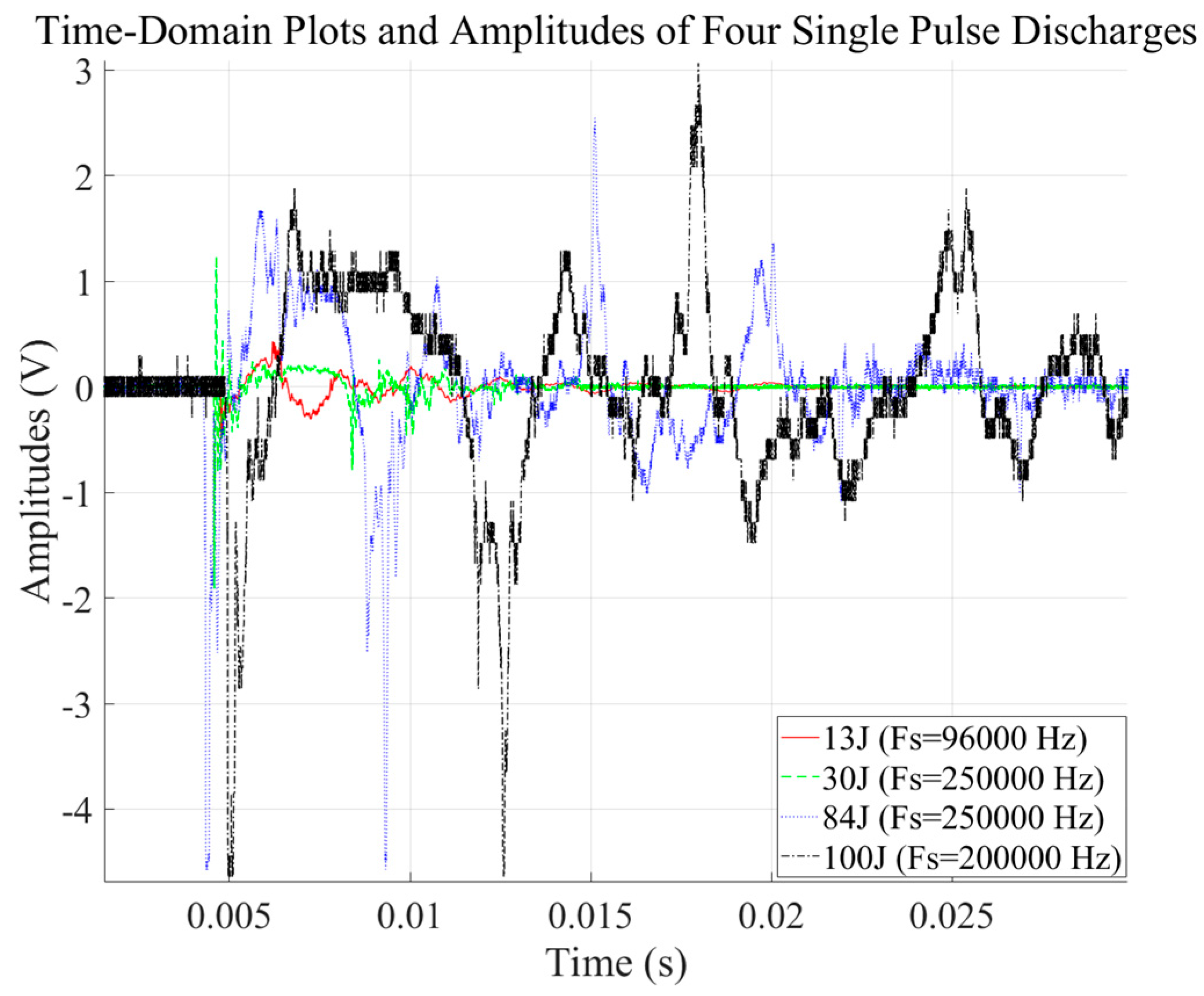

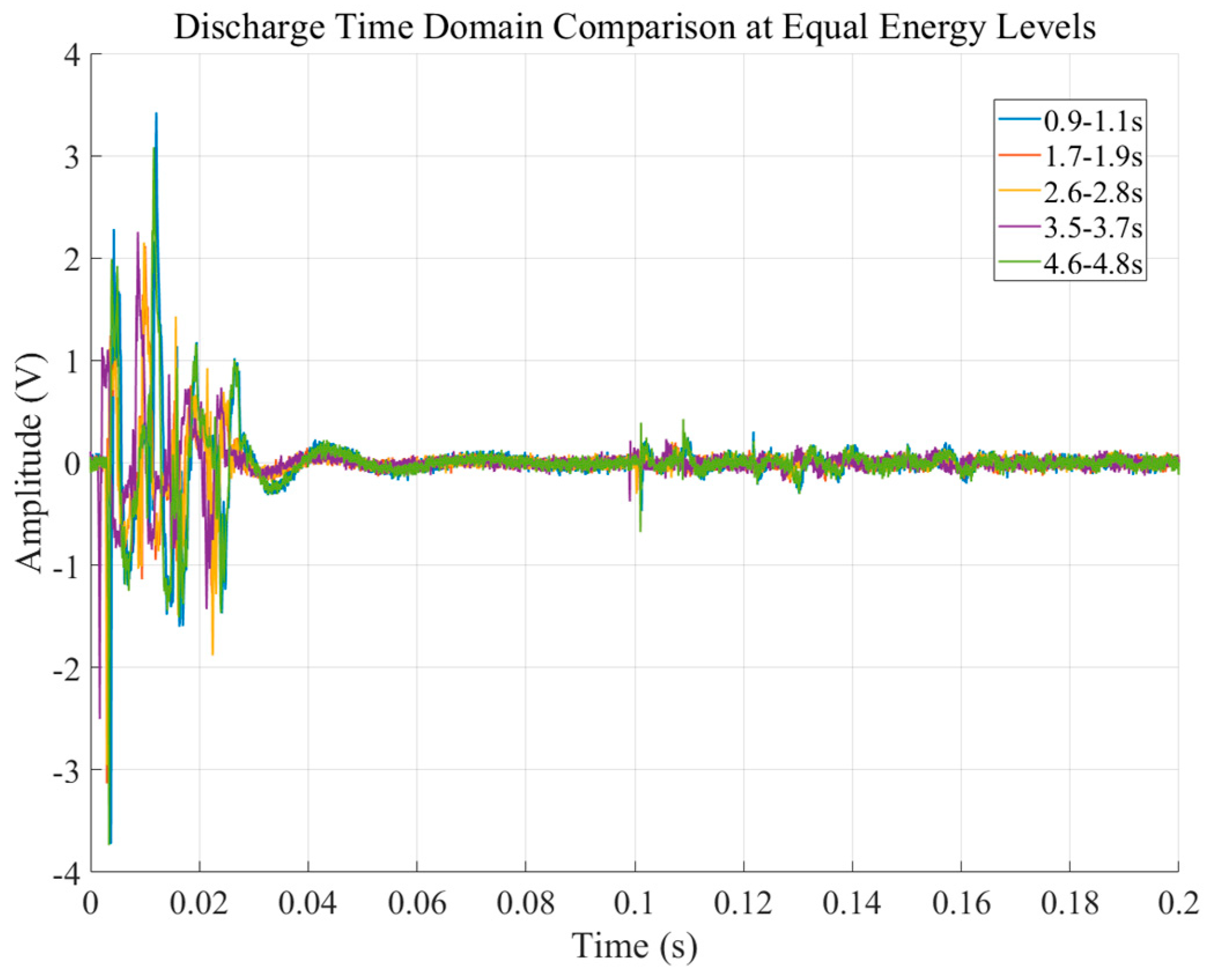

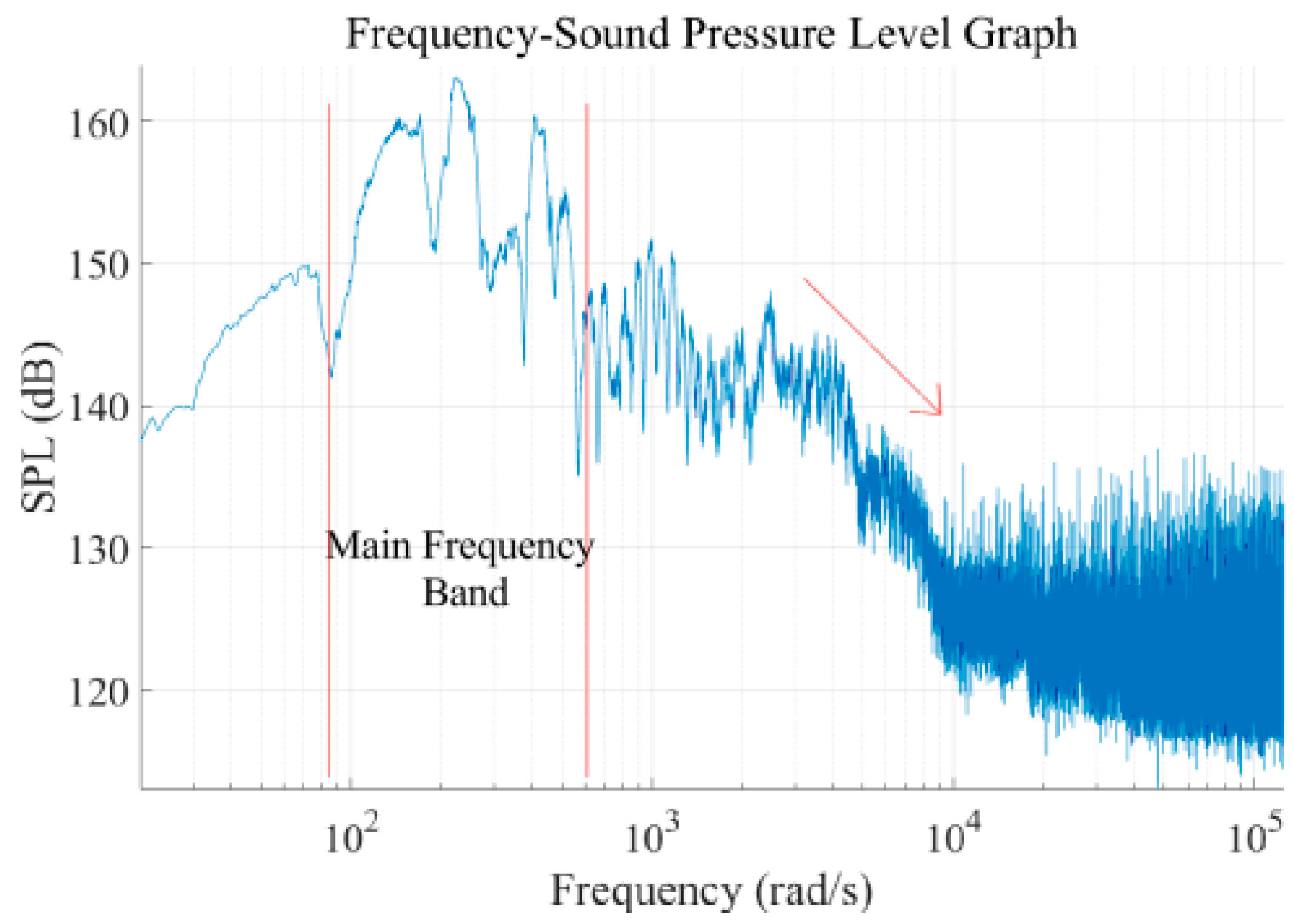

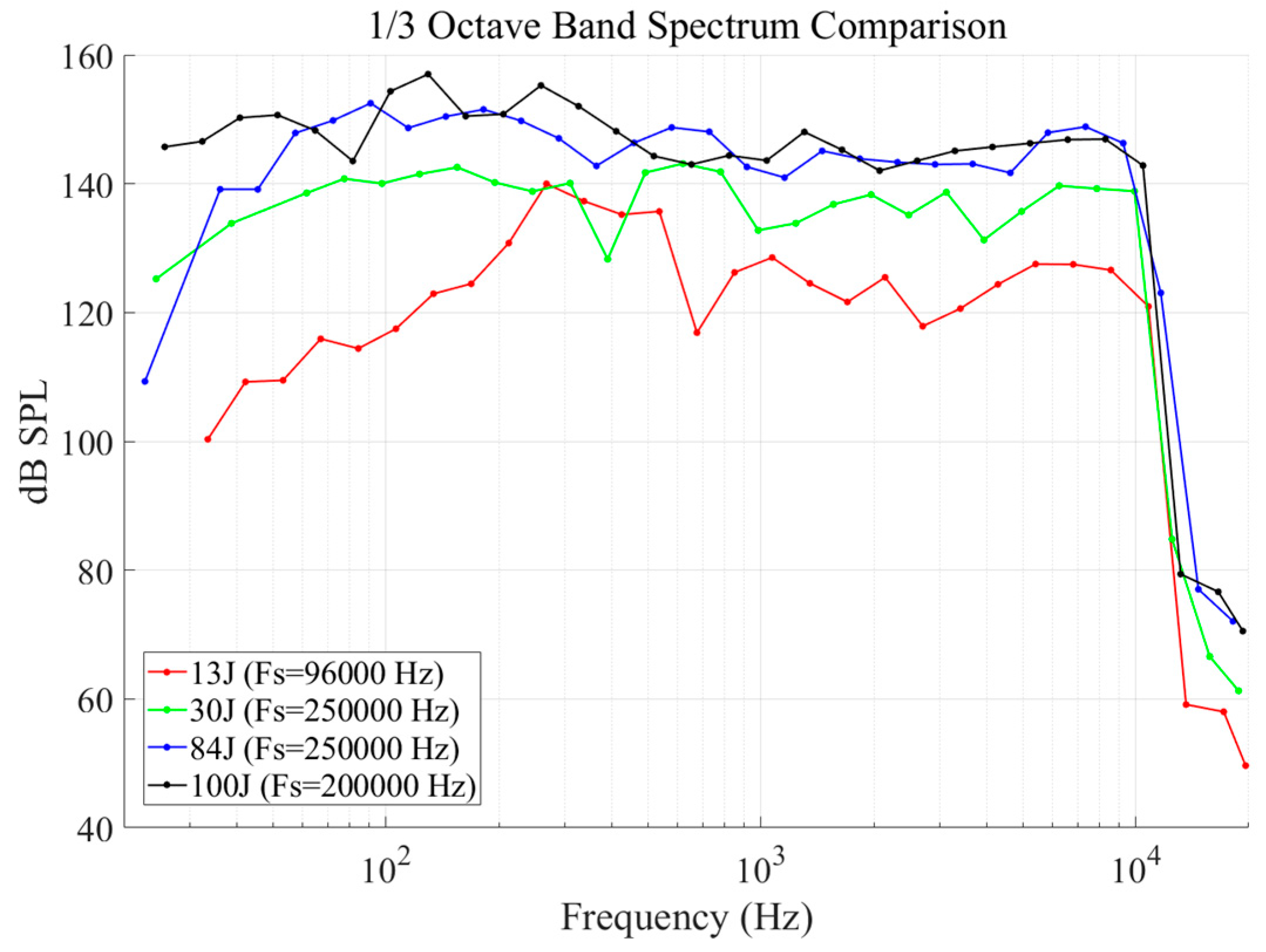

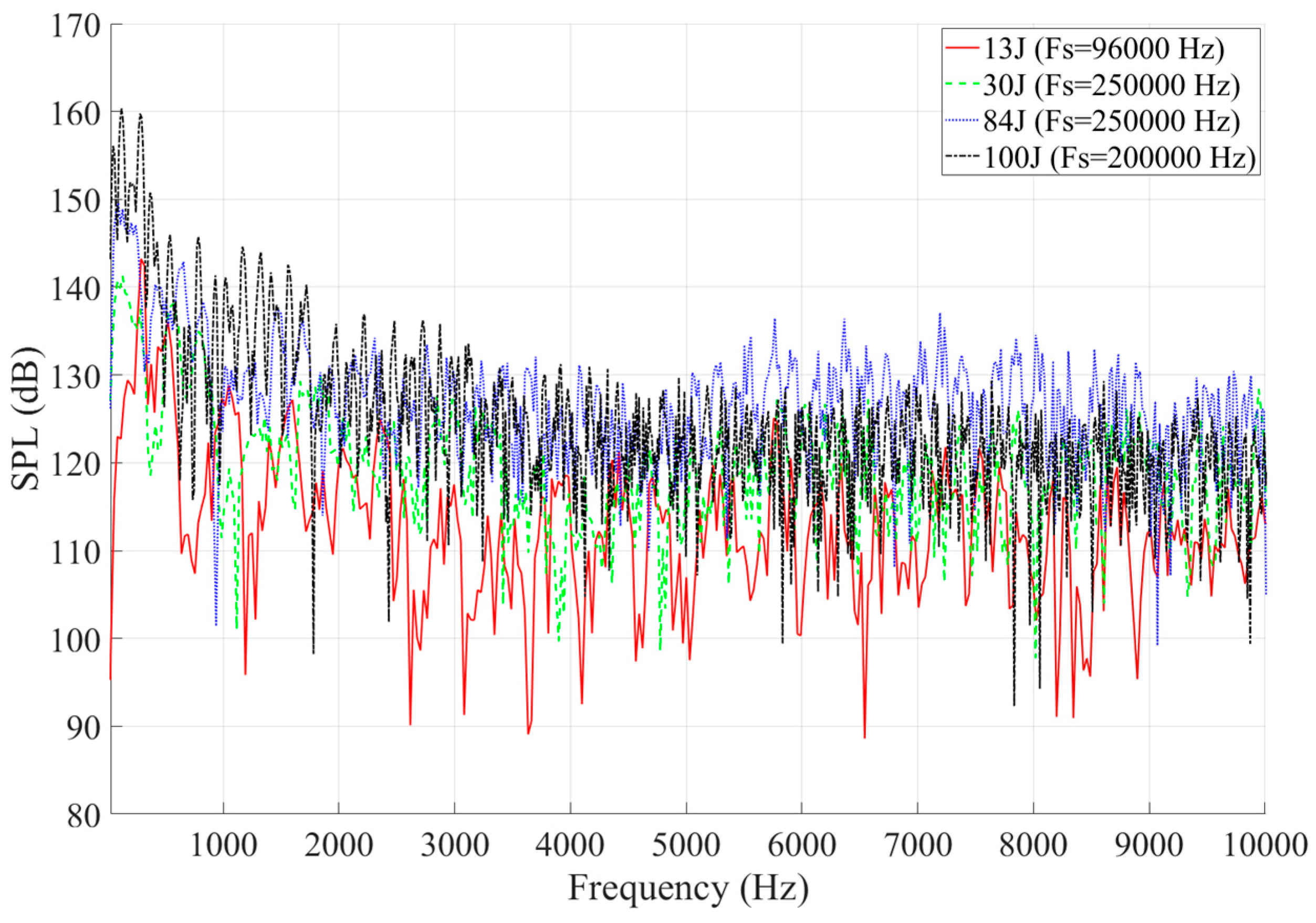

3.3.1. Time-Frequency Characteristics

3.3.2. Energy Analysis

3.4. Model Validation and Quantitative Comparison

- (1)

- Short-range deep-water conditions (spherical model should be used)

- (2)

- Long-range shallow-water conditions (cylindrical model should be applied)

4. Summary and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.; Maurel, O.; Reess, T.; De Ferron, A.S.; La Borderie, C.; Pijaudier-Cabot, G.; Rey-Bethbeder, F.; Jacques, A. Experimental study on an alternative oil stimulation technique for tight gas reservoirs based on dynamic shock waves generated by pulsed arc electrohydraulic discharges. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 88–89, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, S.; Cui, P.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. A unified theory for bubble dynamics. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 033323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutkin, L.A. Electrohydraulic Effect; Mashgiz: Moscow, Russia, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.-Y.; Wu, J.-W.; Zhou, H.-B.; Ding, W.-D.; Qiu, A.-C.; Clayson, T.; Wang, Y.-N.; Ren, H. Characteristics of exploding wires in water with three discharge types. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 033302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Inoue, K.; Itoh, S. Research on the underwater shock wave generated by discharge of high voltage impulsive current. In Proceedings of the ASME Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference (ASME, 2005), Denver, Colorado, 17–21 July 2005; Volume 41898, pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Pulsed discharge in water and its application as sound source. In Pulsed Discharge Plasmas: Characteristics and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 833–850. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Cao, Q.; Li, L.; Han, X. Effects of different parameters on the electrical and shock wave characteristics in underwater electrical explosion of copper wires: Modeling and analysis. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 138, 133302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Wu, J.; Ding, W.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, A. Optical radiation characteristics of electrical explosion of different metal wires in air. High. Voltage Eng. 2017, 9, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais, M.P.; Kress, J.D.; Collins, L.A. Electrical conductivity for warm, dense aluminum plasmas and liquids. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 025401(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilva, A.W.; Katsouros, J.D. Electrical conductivity of dense copper and aluminum plasmas. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 57, 5945–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftman, D.; Krasik, Y.E. Investigation of electrical conductivity and equations of state of non-ideal plasma through underwater electrical wire explosion. Phys. Plasmas 2010, 17, 112702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Lai, C.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Preparation, Mechanical Properties and Strengthening Mechanism of W-Re Alloys: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.Y.; Wu, J.W.; Ding, W.D.; Zhou, H.B.; Qiu, A.C.; Zhang, Y.M. Experimental study on characteristics of underwater copper wire electrical explosion under different pulsed currents. Proc. CSEE 2019, 39, 1251–1259. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Xu, D.W.; Liu, T.J. Variation of wire impedance during electrical explosion. Explos. Shock. Waves 2009, 29, 205–208. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.W. Calculation and Characteristic Analysis of Mid-Low Frequency Ocean Acoustic Field in Typical Seabed Environments Based on Finite Element Method. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harbin Engineering University, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zou, M.S.; Jiang, L.W. A computational method for the sound radiation field of a target in an ocean waveguide. Acta Acust. 2019, 44, 1027–1035. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasik, Y.E.; Efimov, S.; Sheftman, D.; Fedotov-Gefen, A.; Antonov, O.; Shafer, D.; Yanuka, D.; Nitishinskiy, M.; Kozlov, M.; Gilburd, L.; et al. Underwater electrical explosion of wires and wire arrays and generation of converging shock waves. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2016, 44, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.M.; Eltaleb, I.; Soliman, M.Y. Experimental Study of Energy Design Optimization for Underwater Electrical Shockwave for Fracturing Applications. Geosciences 2024, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xu, W.; Yin, C.; Lei, Z.; Kong, X. Correction Method for Initial Conditions of Underwater Explosion. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, R.; Jeyabarathi, P.; Rajendran, L.; Lyons, M.E.G. Theory for Electrochemical Heat Sources and Exothermic Explosions: The Akbari–Ganji Method. Electrochem 2023, 4, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, H. Research status and prospects of novel technology in underwater wet arc welding/laser cladding. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 148, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Almatrafi, E.; Hu, T.; Zhou, C.; Song, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, G. Efficient removal of microplastics from wastewater by an electrocoagulation process. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.Y.; Peng, Z.H.; Zhang, B. Statistical characteristics of shallow water acoustic propagation loss induced by undulating sea surface scattering and rapid sound field prediction method. Acta Acust. 2023, 48, 1098–1110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chace, W.G.; Moore, H.K. Exploding Wires; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959; Volume 1, pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pikuz, S.A.; Shelkovenko, T.A.; Sinars, D.B.; Greenly, J.B.; Dimant, Y.S.; Hammer, D.A. Multiphase foamlike structure of exploding wire cores. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qian, D.; Zou, X.; Wang, X. Effect of Deposition Energy on Underwater Electrical Wire Explosion. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2018, 46, 3444–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Li, X.; Jia, S. Electrical Characteristics of Microsecond Electrical Explosion of Cu Wires in Air Under Various Parameters. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2018, 46, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source Vertical Position | Propagation Distance Condition | Applicable Model | Physical Rationale and Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper-half space (Near water surface) | x0 ≤ R0 | Spherical Model | Wavefront not truncated by boundaries, approximating free-field spherical spreading. |

| R0 < x0 ≤ d0 − R0 | Cylindrical Model | Wavefront constrained by the seabed boundary, forming a cylindrical waveguide. | |

| x0 > d0 − R0 | Cylindrical Model (requires correction) | Wavefront asymmetrically constrained by both seabed and water surface, requiring consideration of different reflection coefficients. | |

| Mid-water (Half water depth) | x0 ≤ R0 | Spherical Model | Wavefront not truncated by boundaries, approximating free-field spherical spreading. |

| x0 > R0 | Cylindrical Model | Wavefront constrained by both upper and lower boundaries, forming a symmetric cylindrical waveguide. | |

| Lower-half space (Near seabed) | x0 ≤ R0 | Spherical Model | Wavefront not truncated by boundaries, approximating free-field spherical spreading. |

| R0 < x0 ≤ d0 − R0 | Cylindrical Model | Wavefront constrained by the water surface boundary, forming a cylindrical waveguide. | |

| x0 > d0 − R0 | Cylindrical Model (requires correction) | Wavefront asymmetrically constrained by both water surface and seabed, requiring consideration of different reflection coefficients. |

| Propagation Model | Baseline Value | Variation Range | Step Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-water propagation | 0.30 | 0.15–0.45 | 0.05 |

| Upper-half space | 0.35 | 0.20–0.50 | 0.05 |

| Lower-half space | 0.25 | 0.10–0.40 | 0.05 |

| Reflection Coefficient | Shock Wave Energy (J) | Relative Deviation | Energy Utilization Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | 2.12 | −13.5% | 2.12 |

| 0.25 | 2.31 | −5.7% | 2.31 |

| 0.30 | 2.45 | 0.0% | 2.45 |

| 0.35 | 2.58 | +5.3% | 2.58 |

| 0.40 | 2.72 | +11.0% | 2.72 |

| Energy Component | Energy Value (J) | Proportion (%) | Data Source | Uncertainty (±) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitor Energy Storage | 84.00 | 100.0 | Direct Measurement | 0.05% |

| Shock Wave Energy | 1.17 | 1.39 | Direct Measurement | 0.15% |

| Bubble Kinetic Energy | 15.12 | 18.0 | Indirect Calculation | 3.2% |

| Thermal Radiation | 33.60 | 40.0 | Indirect Calculation | 5.8% |

| Optical Radiation | 8.40 | 10.0 | Literature Estimate | 2.1% |

| Electrode Losses | 10.08 | 12.0 | Literature Estimate | 4.3% |

| Other Losses | 5.04 | 6.0 | Literature Estimate | 2.5% |

| Total Accounted | 73.41 | 87.4 | Total | - |

| Unaccounted Losses | 10.59 | 12.6 | Assumed Estimate | - |

| Parameter | Measurement Range | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Water temperature | 18.5–21.2 °C | Vertical gradient < 0.5 °C/m |

| Salinity | 0.08–0.12‰ | Freshwater environment |

| Wave height | 0–0.3 m | Calm to slight sea state |

| Water depth | 24.8–25.2 m | Negligible tidal influence |

| Stored Energy (J) | Primary Pulse Energy Share (%) | Secondary Pulse Energy Share (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 98.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | Energy release highly concentrated |

| 30 | 96.2 ± 1.5 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | |

| 84 | 85.4 ± 2.1 | 14.6 ± 2.1 | Significant contribution from secondary pulses |

| 100 | 78.3 ± 3.0 | 21.7 ± 3.0 | Energy temporally most dispersed |

| No. | Stored Energy (J) | Lateral Range (m) | Selected Model | Energy (J) | Energy Utilization Efficiency | Average Utilization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 10 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0568 | 0.437% | 0.394% |

| 2 | 13 | 10 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0512 | 0.394% | |

| 3 | 13 | 10 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0653 | 0.502% | |

| 4 | 13 | 31 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0458 | 0.352% | |

| 5 | 13 | 50 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0437 | 0.336% | |

| 6 | 30 | 1 | Cylindrical Model | 0.073 | 0.243% | 0.421% |

| 7 | 30 | 1 | Cylindrical Model | 0.0799 | 0.266% | |

| 8 | 30 | 1 | Spherical Model | 0.1472 | 0.491% | |

| 9 | 30 | 12 | Cylindrical Model | 0.1517 | 0.506% | |

| 10 | 30 | 12 | Cylindrical Model | 0.204 | 0.680% | |

| 11 | 84 | 1 | Spherical Model | 0.8908 | 1.060% | 1.391% |

| 12 | 84 | 1 | Spherical Model | 1.1883 | 1.415% | |

| 13 | 84 | 9 | Spherical Model | 1.0985 | 1.308% | |

| 14 | 84 | 11.5 | Cylindrical Model | 1.2892 | 1.535% | |

| 15 | 84 | 5.5 | Cylindrical Model | 1.2177 | 1.450% | |

| 16 | 100 | 10.5 | Spherical Model | 2.0058 | 2.006% | 2.450% |

| 17 | 100 | 10.5 | Spherical Model | 2.9124 | 2.912% | |

| 18 | 100 | 10.9 | Spherical Model | 2.4319 | 2.432% | |

| 19 | 100 | 10.9 | Spherical Model | 1.8284 | 1.828% | |

| 20 | 100 | 40.4 | Cylindrical Model | 3.7926 | 3.793% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xin, S.; Zhang, X.; Ni, L.; Zhou, X. Near-Field Shock Wave Propagation Modeling and Energy Efficiency Assessment in Underwater Electrical Explosions. Energies 2026, 19, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010261

Xin S, Zhang X, Ni L, Zhou X. Near-Field Shock Wave Propagation Modeling and Energy Efficiency Assessment in Underwater Electrical Explosions. Energies. 2026; 19(1):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010261

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Shihao, Xiaobing Zhang, Lei Ni, and Xipeng Zhou. 2026. "Near-Field Shock Wave Propagation Modeling and Energy Efficiency Assessment in Underwater Electrical Explosions" Energies 19, no. 1: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010261

APA StyleXin, S., Zhang, X., Ni, L., & Zhou, X. (2026). Near-Field Shock Wave Propagation Modeling and Energy Efficiency Assessment in Underwater Electrical Explosions. Energies, 19(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010261