Abstract

This paper presents a method for detecting inter-turn short-circuit faults in motor windings using the inverter’s DC link current. The proposed approach leverages the fact that the second harmonic component of the DC bus current increases significantly under abnormal conditions. By analyzing the dynamic behavior of this second harmonic signal, the method enables fast, easily integrated fault diagnosis without requiring any hardware modifications. The experimental results verify the method’s effectiveness. At 500 rpm, a 5% partial short circuit produces a second harmonic component about 2.8 times larger than that of a healthy motor, while a 30% fault raises the ratio to about 3.6. The close match between theory and experiment confirms the accuracy and practicality of the proposed technique.

1. Introduction

Permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) are now widely used for their high efficiency and are increasingly replacing induction motors in appliances and electric vehicles [1,2,3]. PMSM design often focuses on increasing power density to reduce weight or size while maintaining performance. However, this design trend also brings challenges in mechanical stress, heat dissipation, and noise, leading to an increased risk of failure [4]. Motor failures can often be categorized into mechanical and electrical causes. A survey of over 7000 industrial motors found that more than 30% of failures were due to stator winding problems. More than 80% of these involve inter-turn short-circuit (ITSC) faults [5]. An ITSC fault in a motor is a failure of the insulation between the turns of the motor winding, causing the current to bypass the predetermined path. This can be caused by factors such as aging insulation, vibration, or overload, and can cause symptoms such as overheating or unusual noises.

Based on the literature review, ITSC fault diagnosis methods can be broadly categorized with analytical models and signal processing-based methods. Analytical model-based diagnosis estimates system states and compares them with predefined tables, but its accuracy depends heavily on the complexity of the mathematical model [6,7]. At this time, AI-assisted analysis methods allow large datasets to be used for learning and analysis, and recent advances have significantly improved their performance [8,9,10]. Signal-based methods process control signals and require relatively simple hardware and software. Methods such as Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA) and Motor Voltage Signature Analysis (MVSA) are non-invasive and utilize signals already available in the motor controller [11,12,13]. However, inverter feedback signals in these methods often carry considerable noise, requiring the diagnostic circuitry to be highly noise-tolerant to prevent false alarms.

On the other hand, studies have shown that during ITSC faults, the dq axis voltage and current of vector-controlled PMSM present second harmonic components [14,15]. While voltage or current-based harmonic analysis can capture these features, instantaneous power harmonics have been shown to provide more comprehensive fault information. To further improve robustness under varying bandwidth conditions, this study also introduced a Rayleigh Quotient-based weighting function that evaluates the relationship between current and voltage ratios [16]. Following this harmonic-based analysis, ref. [9] proposed using the zero-sequence voltage component (ZSVC) as an indicator. This approach, which relies on low-frequency voltage signal analysis, offers a relatively simple implementation. However, it requires access to the neutral point voltage and the construction of a zero-sequence impedance network. These requirements often necessitate intrusive paths into the stator windings, which presents a significant challenge in compact or miniaturized motor designs. Subsequent studies further extended the ZSVC-based diagnostic approach by integrating fault-tolerant control strategies [17,18,19,20]. By injecting designated current signals into the control loop based on the acquired diagnostic indicators, the proposed methods aimed to suppress current fluctuations and torque pulsations during ITSC events.

From the drive system as a whole, when an ITSC fault occurs, the motor operates in an unbalanced three-phase state. Because the motor current comes from the inverter, abnormal changes in the inverter’s DC link current can be used to detect ITSC faults. Therefore, this paper proposes to use DC link current monitoring in inverters to identify inter-turn short-circuit faults in PMSMs. Since DC voltage and current monitoring are basic inverter protection functions, analyzing these signals during ITSC events enables faster and simpler fault detection. In other words, the proposed method leverages the existing inverter protection loop to detect ITSC faults without modifying the controller hardware. It uses the same signals required for motor speed monitoring and DC bus protection, with only a second harmonic calculation added in software, making the implementation simple and easy to integrate into existing online motor drive diagnostic systems.

It should be noted that compared with MCSA and ZSVC, the proposed method focuses primarily on the single observation of the second harmonic current, resulting in a substantially lower computational burden and facilitating easier integration into existing protection firmware. By embedding directly into the inverter’s existing protection architecture and working in harmony with other protection functions, the proposed design prioritizes a balance between computing resources and reasonable detection sensitivity. Additionally, during normal operation, the system is subject to various industrial interferences, including DC bus ripple, inverter switching noise, and grid disturbances, which may affect harmonic extraction. However, the spectral characteristics of these disturbances differ from those utilized by the proposed method, and they can be effectively distinguished and identified through appropriate signal processing.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the electromagnetic principle of the PMSM and the paradigm of the proposed inter-turn short-circuit detection method. Section 3 discusses the effect of torque ripple on motor operation. Section 4 presents the test results, followed by Section 5, which draws the conclusions.

2. Electromagnetic Theory Analysis of PMSM

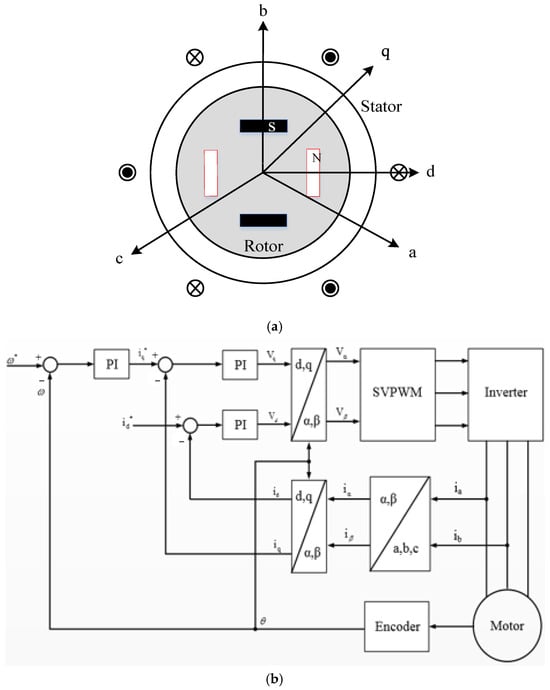

Figure 1a illustrates a cross-sectional schematic of an interior permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM). In an ideal motor model, the back electromotive force (EMF) is assumed to be sinusoidal and three-phase balanced. Magnetic hysteresis and eddy current losses are neglected, and the self-inductance and mutual inductance of the three-phase windings are considered constant [21,22]. Under these assumptions, the relationship between the motor phase voltages and the stator flux linkages can be expressed as follows:

where va, vb, vc are the three-phase stator voltages, Rs is the stator winding resistance, ia, ib, ic are the three-phase stator currents, and λa, λb, λc denote the respective phase flux linkages. The stator flux linkages are further expressed in terms of inductances and the rotor’s permanent magnet flux as follows:

where Ls and Ms are the self- and mutual inductances of the stator windings, and λma, λmb, λmc represent the flux linkages due to the rotor permanent magnets projected onto each phase axis.

Figure 1.

Basic structure and field-oriented controller of permanent magnet synchronous motor: (a) schematic cross-sectional view; (b) field-oriented controller.

Based on the above electromagnetic model, field-oriented control (FOC) can be employed to achieve decoupled control of torque and flux in PMSM drives [22,23]. The FOC strategy typically consists of a speed or torque controller, inner current control loops, and a space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) scheme [24,25,26].

As shown in Figure 1b, the mechanical angular speed command ω*m is compared with the speed feedback signal, and the resulting error is processed by the speed controller to generate the dq-axis current references (i*d, i*q). These references are compared with the measured currents and processed by the current regulators, which are then transformed back to the αβ frame via inverse Park and Clarke transformations [23,27]. The resulting signals are input to the SVPWM module and used to drive the power transistors.

3. Proposed Fault Detection Method

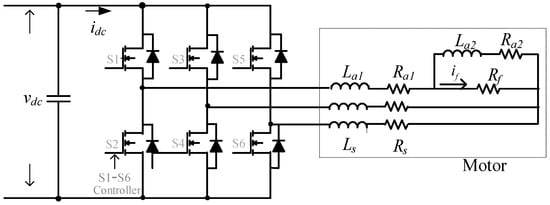

Figure 2 illustrates the equivalent circuit model under the stator fault in phase A of the motor. When a short-circuit fault occurs in the stator winding of phase A, the EMFs (ea, eb, ec) can be derived by differentiating the corresponding magnetic flux linkages. In this case, Equations (1) and (2) can be modified accordingly.

where vas1, vas2, Ra1, Ra2, and if are the fault-induced positive-sequence phase voltage, negative-sequence phase voltage, the corresponding resistance of the phase A winding, and the resulting fault current. Although motor faults introduce high-frequency harmonics in the flux linkage, their amplitudes are much smaller than the fundamental component and can thus be neglected. The severity of the stator short-circuit fault is then quantified using the fault ratio factor u, defined as the ratio of shorted turns NS in phase A to the total turns NT in the same phase. Accordingly, (3) can be rewritten as follows:

Figure 2.

Circuit model of the stator winding turn-to-turn short circuit fault in the motor.

The fourth row of the above matrix yields the following:

Since the effects of the winding resistance, inductance, and mutual inductance cancel out and are relatively minor, the resulting fault current can be approximately expressed as follows:

From (6), the fault current is a sinusoidal waveform, whose amplitude is proportional to the fault ratio u, the rotational speed, and the magnitude of the main flux linkage. Substituting (6) into (3) and applying the dq-axis transformation yields the following:

Here, vdq represents the dq-axis components of the motor voltage, while id and iq denote their current components. Equation (7) indicates that under an inter-turn short-circuit fault in the stator winding, the dq-axis voltage of a PMSM can be decomposed into the healthy component vdqh and the fault-induced component vdqf, which is related to the fault current if as follows:

where Tθ denotes the product of the Clarke and Park transformations matrix. From (9), the fault voltage component can be expressed as follows:

In the above equation, θif represents the phase angle difference between the fault current and the electrical angle. Moreover, the latter term in Equation (11) corresponds to the second harmonic voltage component of the fault voltage. Taking the inter-turn short-circuit fault of phase a in Figure 2 as an example, θif is 90 electrical degrees. In this case, the second harmonic component of the fault voltage is as follows:

From the above equation, the offset and amplitude of the fault voltage caused by the second harmonic component are related to the severity of the fault. Due to the differential relationship between the voltage and magnetic flux linkage within the motor, the second harmonic component of the fault voltage induces an additional second harmonic component in the rotor flux linkage.

where λmd0 represents the DC component of the rotor flux linkage, and λmd2 and λmq2 denote the second harmonic component of the rotor flux linkage in the dq-axis domain. Furthermore, the electromagnetic torque of the motor can be expressed as follows:

Continuing with Ld and Lq as the stator inductance components in the dq-axis domain, then

As shown in Figure 1b, id in the field-oriented controller is often set as zero. In this case, with Te0 and Te2 denoting the DC and second harmonic torque components, Equations (13)–(15) simplify as follows:

From Equation (16), the second harmonic component of the inter-turn short-circuit fault voltage induces a corresponding second harmonic component in the rotor flux linkage, resulting in torque pulsations at twice the fundamental frequency in the motor output. Notably, from the perspective of the DC link voltage (vdc) and current (idc) of the inverter, and neglecting inverter losses, the following relation holds:

By substituting Equation (16) into Equation (17), we obtain the following:

where and represent the variations in the DC link voltage and current, respectively. From Equation (18), the motor torque pulsation is related to the input DC link voltage and current of the inverter. In practice, since short-duration voltage sags may occur in the utility power supply, large electrolytic capacitors are typically installed in the inverter’s DC link to ensure continuous operation during such events. Therefore, if the capacitance is sufficiently large, can be neglected. As a result, during an inter-turn short-circuit fault in the motor, the electromagnetic torque pulsation will induce an additional second harmonic component in the DC link current. Hence, the amplitude of this harmonic current can be used as an indicator for detecting inter-turn short-circuit faults in the motor windings.

4. Effect of Torque Ripple on Motor Operation on Proposed Method

In dynamic motor drive control systems, torque ripple is a critical factor that degrades speed stability and increases vibration and acoustic noise. In PMSM drives, torque pulsations are mainly caused by magnetic field harmonics, current distortion, and nonideal current regulation, which lead to deviations from the ideal sinusoidal flux linkage [28]. To reduce torque ripple, both control-based and machine design-based approaches have been reported in the literature. From a control perspective, harmonic current suppression and improved current regulation strategies have been shown to effectively reduce electromagnetic torque oscillations without additional hardware [29,30,31]. From a machine design perspective, structural optimization of the rotor and stator has also been demonstrated to significantly reduce cogging torque and torque ripple, particularly in applications requiring high torque smoothness [29].

Accordingly, to analyze the influence of torque ripple on the proposed method, the harmonic components of the stator flux linkage λabc in (2) can be expressed as follows:

where h is the harmonic order. Basically, the dominant harmonic components in the flux linkage λ are the 5th and 7th harmonics. Using Clarke and Park transformations, (19) can be further expressed as follows:

and

After the coordinate transformation, the original 5th and 7th harmonics of the flux linkage λ in the three-phase vector space appear as 6th harmonic components in the dq-axis domain.

where , and the rotor flux linkage of the motor can thus be described as follows:

where λmd0, λmd(q)6, and λmd(q)12 represent the DC component and the 6th and 12th order harmonic components of the rotor flux linkage in the dq-axis, respectively. Using the motor electromagnetic torque and the stator flux linkage in (16), the following can be obtained:

where Te0, Te6, and Te12 represent the DC component and the 6th and 12th harmonic components of the motor torque, respectively. Comparing (18) and (24), the distortion of the sinusoidal waveform of the internal flux linkage indeed causes torque pulsations at the 6th harmonic series. However, this is distinct from the second harmonic torque component caused by stator inter-turn short-circuit faults, and therefore, it is expected not to interfere with the detection of the stator winding inter-turn short-circuit indicator proposed in this paper.

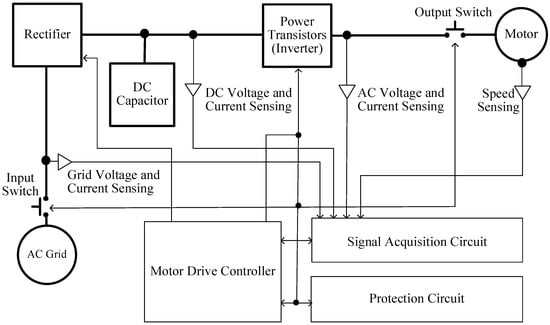

5. Integration with VFD Protection System

This paper analyzes the dynamic behavior of inverter DC current under inter-turn winding faults and proposes a new fault detection method. The method can be directly integrated into existing inverter protection frameworks, reducing the DC link signal-processing load and requiring no modifications to the controller software. Figure 3 shows the block diagram of the proposed scheme embedded within the inverter control and protection architecture. The monitoring signal acquisition circuit performs voltage and current sensing, filtering, and isolation for signals from the grid input, DC link, and motor side. Based on these signals, the protection circuit evaluates inverter operating conditions and sends protection commands to the motor drive controller and input/output switches.

Figure 3.

Motor drive control and protection circuit diagram.

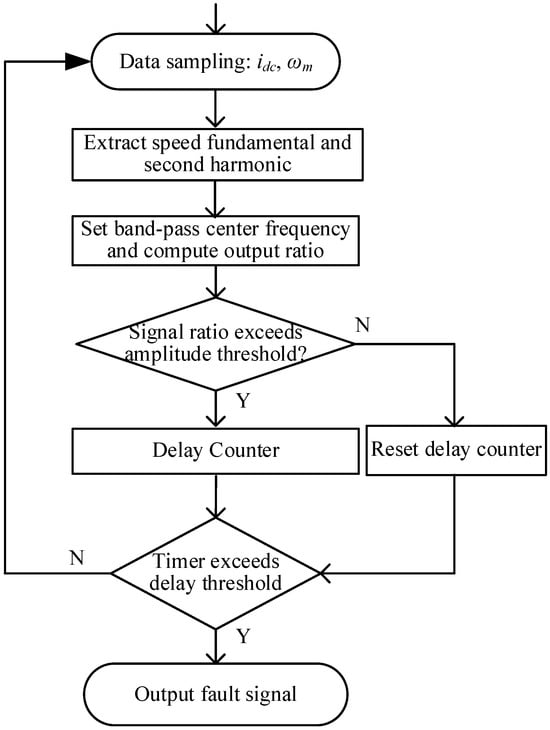

The detailed procedure for detecting inter-turn short circuits is shown in Figure 4. The monitoring circuit first provides the DC link current reference and motor speed signals. Next, the amplitudes of the DC current component and its second harmonic are extracted and compared, and their ratio is used as the fault detection index for identifying inter-turn winding short circuits. At this stage, the center frequency of the band-pass filter is adaptively adjusted according to the rotor speed provided by the FOC controller. The quality factor of the filter is kept constant and is set to 3 based on engineering experience. It is noteworthy that, considering the transient inrush current during motor startup and the system noise during operation, a time threshold is incorporated into the proposed detection flow in practical applications. In this case, the program outputs a fault signal for the stator windings only when both the magnitude and duration of the signal variation exceed the permissible limits. With its high sensitivity and capability for continuous data acquisition, the proposed programmable architecture ensures timely and adaptive responses to varying fault conditions within the drive system.

Figure 4.

Proposed fault detection flowchart.

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Computer Simulation

To ensure successful implementation of the proposed study, a vector-controlled PMSM was simulated in Simulink. The simulation analyzed changes in the inverter DC link current, including the fundamental component related to motor speed and the second-order harmonic component, under inter-turn short-circuit conditions. The motor parameters are as follows: rated voltage 220 V ± 10% (three-phase), rated current 18 A, rated speed 3000 rpm, eight poles, stator resistance 175 mΩ, and d- and q-axis inductances of 0.76 mH and 1.61 mH, respectively. Figure 3 shows the control block diagram of the simulation model.

- (1)

- Healthy Motor Operation Test:

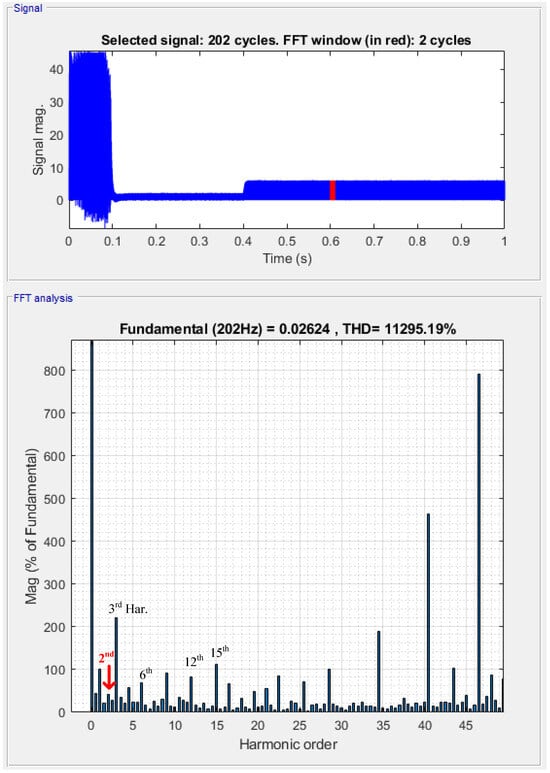

This test verifies the voltage inverter control function of the drive system. The DC link voltage is set to a constant 200 V, the speed command is 3000 rpm, and an external load torque of 2 Nm is applied at 0.4 s. The simulation results are shown in Figure 5, which presents the frequency spectrum of the three-phase motor currents over a short interval around 0.6 s. The results indicate that, under healthy conditions, the three-phase current magnitudes are nearly identical and contain harmonic components dominated by the 3rd- and 6th-order harmonics referenced to the fundamental frequency of 202 Hz, with magnitudes of 220.81% and 65.74%, respectively. These harmonics are mainly caused by the three-phase winding configuration and torque ripple associated with current control. Other components, such as the 101 Hz harmonic, are related to the inverter dead-time setting. The second-order harmonic component of the DC link current under healthy operation is 39.39% of the fundamental motor current, which is significantly lower than the 3rd- and 6th-order harmonics.

Figure 5.

Constant speed test waveform and current spectrogram of certain interval around 0.6 s in motor health state.

- (2)

- Motor Winding Fault Operation Test:

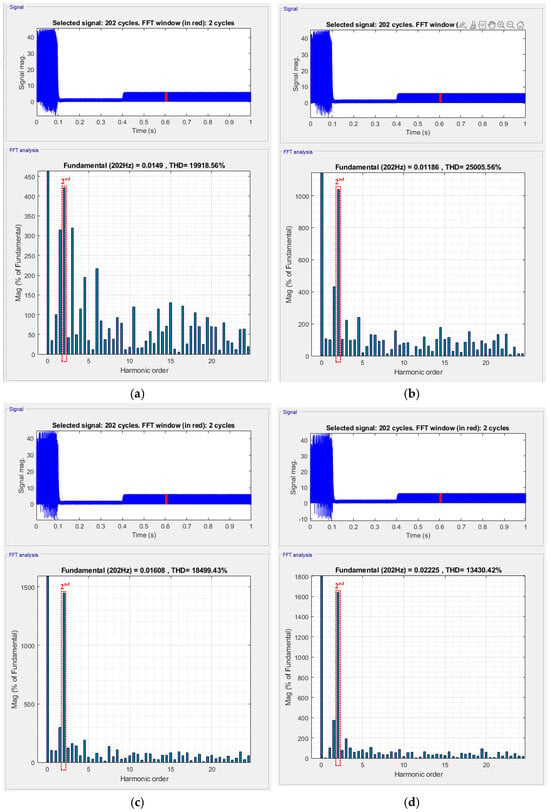

Figure 6 shows the DC link current waveform and its frequency spectrum when a partial inter-turn short-circuit fault occurs in the motor windings, resulting from the A-phase current being 5–30% higher than the B- and C-phase currents. The tested motor has eight poles; therefore, at 3000 rpm, the ideal electrical frequency is 200 Hz. The results indicate that when the A-phase current exceeds the B- and C-phase currents by 5%, a second-order harmonic component appears in the DC link current at 404 Hz with a magnitude of 420.88% of the fundamental current. When the A-phase current increases by 10%, 20%, and 30%, the corresponding DC link second-order harmonic magnitudes are 1038.64%, 1446.65%, and 1639.34% of the fundamental current, respectively. These results show that during inter-turn short-circuit faults, the magnitude of the DC link second-order harmonic current relative to the fundamental current exhibits a clear variation, which is consistent with the theoretical analysis.

Figure 6.

Test waveform of current imbalance of motor short circuit and spectrogram of certain interval around 0.6 s: (a) 5% more current in phase A; (b) 10% more current in phase A; (c) 20% more current in phase A; (d) 30% more current in phase A.

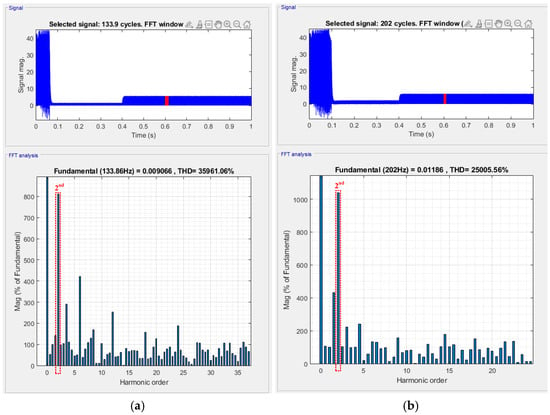

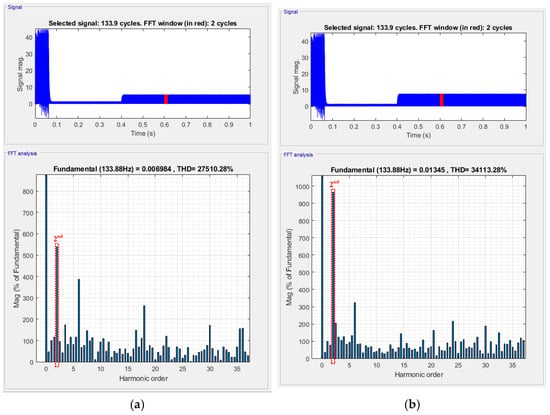

The effects of different motor speeds and load conditions on the proposed method were further investigated. Figure 7 shows the simulated winding fault results when the A-phase current is 10% higher than the B- and C-phase currents, with the motor speed controlled at 2000 rpm and 3000 rpm. In the 2000 rpm case, the actual speed control results in a fundamental electrical frequency of 133.86 Hz, and the DC link second-order harmonic current reaches 810.87% of the fundamental component. At 3000 rpm, the second-order harmonic current is 1038.64% of the fundamental. These results indicate that the ratio of the second-order harmonic current to the fundamental current varies with motor speed. Figure 8 presents the simulation results at 2000 rpm with the A-phase current 10% higher than the B- and C-phase currents under different load torques. The observed second-order harmonic currents are 540% and 952% of the fundamental component at load torques of 1 Nm and 3 Nm, respectively. The results show that the proposed method is not sensitive to load variations and can detect inter-turn short-circuit faults in the motor windings.

Figure 7.

10% current imbalance at different speeds: (a) 2000 rpm; (b) 3000 rpm.

Figure 8.

Test diagram of 10% current imbalance with different loads: (a) 1Nm; (b) 3Nm.

6.2. Experimental Validation

To evaluate the proposed method, experiments were performed on a 3 kW PMSM supplied by a FOC variable-frequency inverter. The test setup applied a DC voltage of 200 V to the inverter, which controlled the motor. The motor has 8 poles, a stator winding resistance of 175 mΩ, and dq-axis inductances of 0.76 mH and 1.61 mH, respectively.

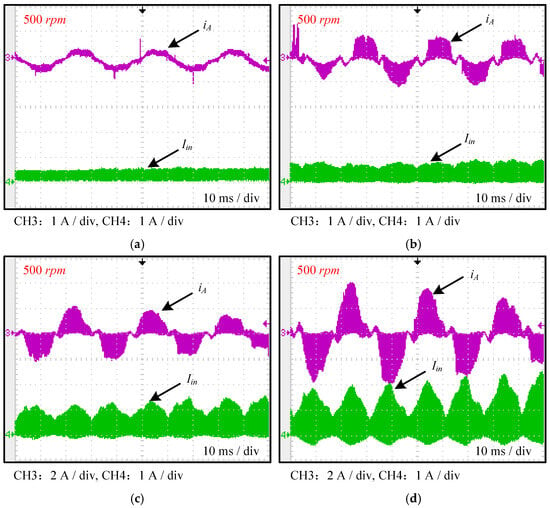

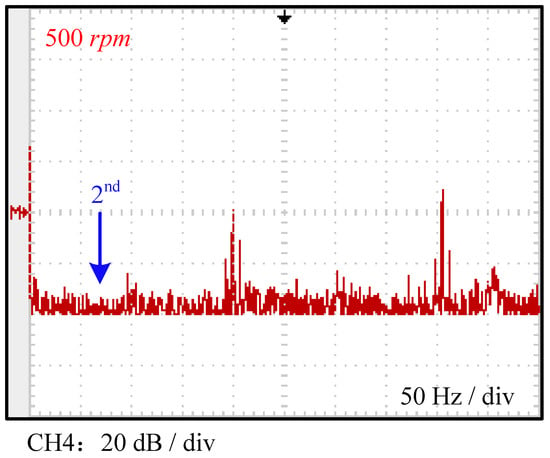

Figure 9 shows the phase A current and the DC link current waveforms under healthy and various fault severity conditions at 500 rpm, while Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the corresponding Fourier frequency-domain analysis results obtained automatically by the oscilloscope. Since the tested motor is an 8-pole machine, the ideal electrical frequency at 500 rpm is 200 Hz. From Figure 10 and Figure 11, under healthy conditions, although harmonic components exist in the inverter DC bus current, they are mainly dominated by the 3rd and 6th harmonics of the fundamental frequency. These 3rd and 6th harmonics are primarily caused by the motor’s three-phase winding arrangement and current control-induced torque pulsations. Other minor harmonic components around 100 Hz are related to the inverter dead-time settings. Regarding the second harmonic component of the DC link current monitored in this study, it accounts for only 12.1% of the motor fundamental frequency current during healthy operation, which is significantly lower than the amplitude of the 3rd and 6th harmonic components.

Figure 9.

Waveforms of A-Phase Current (iA) and DC Link Current (Iin) in the Inverter at 500 rpm. (a) Motor Healthy State. (b) 5%; (c) 10%; (d) 15% inter-turn fault level.

Figure 10.

DC link current spectra in inverter under motor healthy state at 500 rpm.

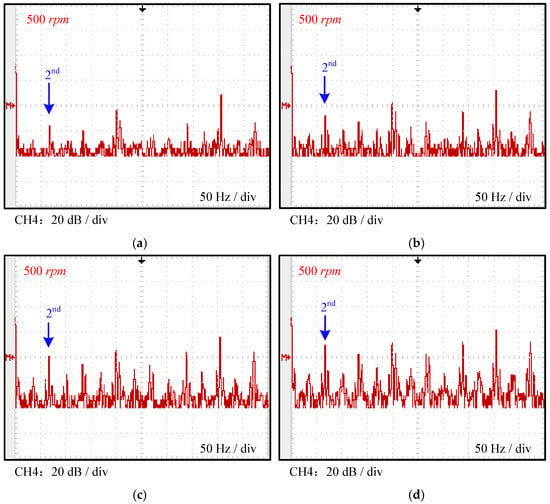

Figure 11.

DC link current spectra in inverter under varying inter-turn fault levels at 500 rpm: (a) 5%; (b) 10%; (c) 15%; (d) 30%.

Furthermore, when inter-turn short circuits occur in the motor winding, and the phase A coil current exceeds the other phases by 5%, 10%, 15%, and 30%, the DC link current exhibits elevated harmonic content. Moreover, the severity of the inter-turn short circuit correlates with the magnitude of the harmonic current. Test results show that if the phase A current exceeds phases B and C by 5%, the second harmonic current at 400 Hz in the DC link current reaches 32.9% of the fundamental frequency current. When the phase A current exceeds phases B and C by 10%, 15%, and 30%, the corresponding second harmonic currents in the DC link are 44.1%, 54.9%, and 68.7% of the fundamental current, respectively. These results indicate that during motor inter-turn short-circuit faults, the magnitude of the second harmonic current in the DC link relative to the fundamental current shows significant variation, consistent with the theoretical analysis presented earlier.

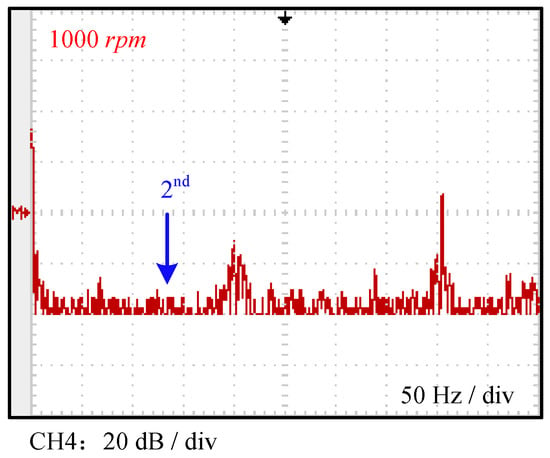

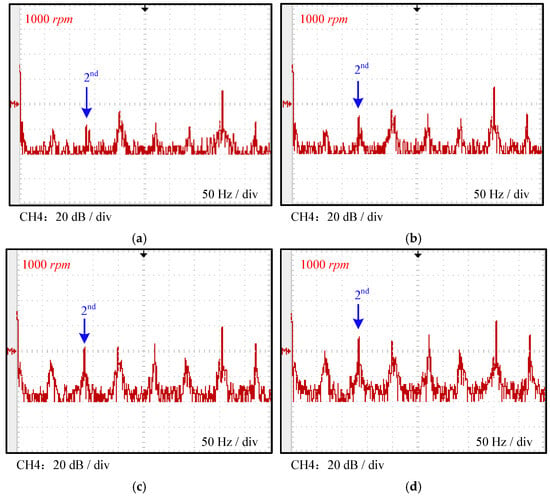

Figure 12 and Figure 13 presents the test results at 1000 rpm. The magnitude of the second harmonic component of the DC link current, which is monitored in this study, is only 11.8% of the motor fundamental frequency current during healthy operation, significantly lower than the amplitudes of the 3rd and 6th harmonic components. However, when partial inter-turn short circuits occur and the phase A current exceeds phases B and C by 5%, 10%, 15%, and 30%, the observed second harmonic currents in the inverter’s DC link current correspond to 33.3%, 43.5%, 58.3%, and 72.2% of the fundamental frequency current, respectively. The test results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively detect inter-turn short-circuit faults in motor windings across different rotational speeds.

Figure 12.

DC link current spectra in the inverter for motor healthy state at 1000 rpm.

Figure 13.

DC link current spectra in the inverter under varying inter-turn fault levels at 1000 rpm: (a) 5%; (b) 10%; (c) 15%; (d) 30%.

7. Conclusions

This study investigates variations in the inverter DC link current and proposes a detection algorithm that uses the ratio of the second harmonic component to the fundamental frequency current in the DC link as an indicator of inter-turn short-circuit faults. Experimental tests on the prototype platform demonstrate that at motor speeds of 500 and 1000 rpm, when a winding short circuit fault exceeding 5% occurs, the second harmonic current magnitude in the inverter DC link can exceed that of a healthy motor more than 2.8 times. In other words, the relative magnitude of the ratio of the second harmonic current to the fundamental frequency current in the DC link shows significant variation during inter-turn short-circuit faults, with sufficient amplitude change serving as a reliable detection indicator.

Since the DC voltage and current within the motor inverter are already essential monitoring points for protection circuits, the proposed method leverages the dynamic changes in the inverter DC link current to characterize motor winding inter-turn short-circuit faults. This approach enables faster detection and can be integrated into the existing protection system of the motor inverter, thereby enhancing the safety of both the inverter and the motor during operation. Future work will extend the study to investigate the effects of grid quality issues and industrial interferences on the proposed signal-based fault detection method, enabling further comparative analyses and discussions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.-S.P.; methodology, F.-S.P.; software, C.-K.C.; validation, C.-K.C.; formal analysis, F.-S.P.; investigation, F.-S.P.; resources, F.-S.P.; data curation, C.-K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-K.C.; writing—review and editing, F.-S.P. and C.-K.C.; visualization, C.-K.C.; supervision, F.-S.P.; project administration, F.-S.P.; funding acquisition, F.-S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan under Project No. NSTC 114-2221-E-024-005, which greatly contributed to the research resources. The authors sincerely acknowledge this support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author F.-S.P. is employed by the National University of Tainan, Taiwan. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chau, K.T.; Chan, C.C.; Liu, C. Overview of permanent-magnet brushless drives for electric and hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 2246–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.I.; Sakkas, G.K.; Xintaropoulos, F.P.; Pechlivanidou, M.S.C.; Kefalas, T.D.; Tsili, M.A.; Kladas, A.G. Overview on Permanent Magnet Motor Trends and Developments. Energies 2024, 17, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Cheng, M.; Huang, J. Online Interturn Fault Diagnosis of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine Using Zero-sequence Components. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 6731–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, A.H. Root Cause AC Motor Failure Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2000, 36, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.M.; Faiz, J. Feature Extraction for Short-circuit Fault Detection in Permanent-magnet Synchronous Motors using Stator-current Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarani, M.; Bostanci, E.; Qi, Y.; Goktas, T.; Akin, B. Interturn Short-Circuit Faults in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Extended Review, and Comprehensive Analysis. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2018, 6, 2173–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoletti, M.A.; Bossio, G.R.; D’Angelo, C.H.; Trejo, D.R.E. A Model-based Strategy for Interturn Short-circuit Fault Diagnosis in PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 7218–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, J.A.; Romeral, L.; Ortega, J.A.; Rosero, E. Short-circuit Detection by Means of Empirical Mode Decomposition and Wigner-Ville Distribution for PMSM Running under Dynamic Condition. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 4534–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, N.H.; Boileau, T.; Nahid-Mobarakeh, B. Modeling and Diagnostic of Incipient Inter-turn faults for a Three Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor using Wavelet Transform. In Proceedings of the IEEE 51st Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Addison, TX, USA, 18–22 October 2015; pp. 4426–4434. [Google Scholar]

- Zsuga, Á.; Sugny, T.; de la Torre, I.M. Early Detection of ITSC Faults in PMSMs Using Wavelet-Transformer Method. Energies 2025, 18, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.Z.; Lopez, C.A.; Foster, S.N.; Strangas, E.G. A Voltage-based Approach for Fault Detection and Separation in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 5305–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, Y. Interturn Short-Circuit Fault Detection of a Five-Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies 2021, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Wang, C. Fault Detection of Stator Inter-Turn Short-Circuit in PMSM on Stator Current and Vibration Signal. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Griffo, A.; Sen, B. Stator Turn Fault Detection by Second Harmonic in Instantaneous Power for a Triple-redundant Fault-tolerant PM Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 7279–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Aggarwal, A.; Strangas, E.G.; Li, K.; Niu, F.; Huang, X. Robust Stator Winding Fault Detection in PMSMs with Respect to Current Controller Bandwidth. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 5032–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H. Simple Online Fault Detecting Scheme for Short-circuited Turn in a PMSM through Current Harmonic Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 2565–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urresty, J.C.; Riba, J.R.; Romeral, L. Diagnosis of Interturn Faults in PMSMs Operating under Nonstationary Conditions by Applying Order Tracking Filtering. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhan, W.; Ehsani, M. Fault-tolerant Control of PMSM With Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Fault. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 34, 2267–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welchko, B.A.; Wai, J.; Jahns, T.M.; Lipo, T.A. Magnet-flux-nulling Control of Interior PM Machine Drives for Improved Steady-state Response to Short-circuit Faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2006, 42, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Sun, W.S.; Hu, Q.; Ren, X.; Ding, S. Integration of Inter-turn Fault Diagnosis and Fault-Tolerant Control for PMSM Drive System. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, J. Sensorless control of induction motor drives. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1359–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R. Permanent Magnet Synchronous and Brushless DC Motor Drives; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z. Improved field-oriented control of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on accurate dq-axis modeling. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 3723–3733. [Google Scholar]

- Preindl, M.; Bolognani, S. Model predictive direct speed control with finite control set of PMSM drive systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.G.; Lipo, T.A. Pulse Width Modulation for Power Converters: Principles and Practice; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rub, H.; Iqbal, A.; Guzinski, J. High Performance Control of AC Drives with MATLAB/Simulink Models; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, M. Review of control strategies for permanent magnet synchronous motor drives. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 207902–207918. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z. Torque ripple suppression for PMSM drives based on improved current control strategy. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 112345–112354. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, W.-T.; Hwang, J.-C.; Liu, J.-E. Development of three-phase permanent-magnet synchronous motor drive with strategy to suppress harmonic current. Energies 2021, 14, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liao, Y.; Lin, H.; Sun, J. Torque ripple suppression of permanent magnet synchronous machines by minimal harmonic current injection. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Lai, C.; Kar, N.C. Speed harmonic based decoupled torque ripple minimization control for permanent magnet synchronous machine with minimized loss. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.