1. Introduction

One of the conditions for effectively solving a field problem is the selection of an appropriate coordinate system. This selection is based on an analysis of the symmetry of the problem and aims to minimize the number of physical quantity coordinates required to describe it. This can be proven by the analysis of the electrostatic field in the vicinity of a point charge in three-dimensional space: the electric field intensity vector has three components in Cartesian coordinates, whereas in spherical coordinates it has only one—similarly to the magnetic field intensity vector near a current-carrying conductor when expressed in cylindrical coordinates. Therefore, it is necessary to know the representation of differential operators in different systems.

This aspect is particularly important in the mathematical and field-oriented modeling of electrical machines, in which cylindrical symmetry frequently appears. Field modeling approaches—including those based on the finite element method—are now widely used for the analysis, design, and optimization of rotating electrical machines, especially with regard to efficiency, losses, and electromagnetic performance [

1,

2]. Recent contributions also demonstrate a growing interest in the use of fractional-order calculus in electromechanical systems. For example, Zafar et al. [

3] developed a fractional-order model of a brushless DC motor based on Caputo derivatives and investigated its nonlinear dynamic behavior. However, such studies focus primarily on time-domain system dynamics and do not address spatially distributed electromagnetic fields. In contrast, the present work extends fractional-order modeling into the spatial domain by formulating fractional differential operators in cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems, making them suitable for electromagnetic field analysis in electrical machines and other electromechanical devices.

For integer operators, so-called Lamé coefficients are used when changing coordinate systems [

4,

5]. Currently, the theory of fractional differential operators is rapidly developing and being applied in physics [

6,

7,

8], engineering sciences, biophysics [

9,

10], medicine [

11], and economics [

12,

13]. In 2015, prof. J. A. Tenreiro Machado, in his paper [

14], lists over 30 fields of application for fractional calculus. There is therefore a need to develop Lamé coefficients for fractional differential operators in various coordinate systems. Classic Lamé coefficients describe only the local geometry of the coordinate system and do not take into account non-local phenomena occurring in real electromagnetic systems. As a result, they prove insufficient in situations involving material heterogeneity, eddy current diffusion, or the skin effect, where the field distribution depends on the environment of the point and not only on its immediate location. Generalizing Lamé coefficients to the case of fractional derivatives allows for the introduction of controlled non-locality, enabling a more realistic description of phenomena that are difficult to capture using classical operators. In recent years, fractional formulations of Maxwell’s equations have attracted considerable attention, with many researchers investigating their applicability to electromagnetic field modeling [

15,

16,

17].

In modern electrical engineering, accurate modeling of electromagnetic fields plays a key role in the design and optimization of electrical machines such as motors, generators, and actuators. Increasing demands for energy efficiency, reduced losses, and improved operational characteristics require mathematical tools capable of representing coupled electric and magnetic phenomena with high fidelity. Fractional-order calculus offers such capabilities. Extending Lamé coefficients to fractional differential operators provides a framework that can improve field modeling in systems with cylindrical and spherical symmetry—including energy-efficient electromechanical devices.

2. Lamé Coefficients for Integer Differential Operators

The relationship between a generalised orthogonal coordinate system (

u,

v,

w) and the Cartesian coordinate system is expressed by Equation (1) [

4,

5]:

After differentiation, the following form of the system is obtained:

It is generally known that in the Cartesian system the square of the distance is:

Thus, in a generalised orthogonal coordinate system:

where Lamé coefficients

g11,

g22 and

g33 are as follows:

The areas of the surface elements defined by:

u =

const,

v =

const and

w =

const are, respectively:

Whereas the volume enclosed between the surfaces:

u = a;

u = a + du,

v = b;

v = b + dv and

w = c;

w = c + dw is:

The nabla operator in a generalised orthogonal coordinate system takes the form:

where

-coordinate system unit vectors (

u,

v,

w).

Based on Equation (8), it is possible to derive the formulas for the gradient of scalar function V, the divergence and rotation of vector A, the scalar Laplacian of the function V and the vector Laplacian of the function A. These formulas take the following forms:

By determining the Lamé coefficients for an arbitrary orthogonal coordinate system, the differential operators can be expressed within that system. For example, in the cylindrical coordinate system (

ρ,

φ,

z) Equation (1) take the form:

Whereas the coefficients (5) are as follows:

In the spherical coordinate system (

r,

φ, Θ), Equation (1) take the form:

Whereas the Lamé coefficients from Equation (5) have the following form:

it should be noted that φ and Θ are coordinates in spherical and cylindrical coordinate systems.

The presented coefficients are well known and appear in problems related to field theory across various coordinate systems.

3. Lamé Coefficients of Fractional Differential Operators

To create Lamé coefficients for fractional derivatives, the first-order derivatives in Equation (5) should be replaced with fractional derivatives. Among the many definitions of fractional derivatives, particular attention should be given to the Caputo fractional derivative definition [

18], as the initial and boundary conditions are expressed in terms of integer-order derivatives, making them easier to interpret physically. In the definition of the Riemann-Liouville derivative, it is necessary to use fractional order initial conditions, which are difficult to interpret physically in electromagnetism. Furthermore, the Caputo derivative allows the application of classical boundary conditions, e.g., Dirichlet and Neumann. The Caputo fractional derivative of order

is defined as follows:

where

,

n ∈

R+. In (19),

n denotes the independent variable and

dτ is the integration variable.

Therefore, this definition will be used in the following discussion.

3.1. Lamé Coefficients for Fractional Differential Operators for Cylindrical Systems

In the cylindrical coordinate system, the Lamé coefficients (5) for fractional derivatives take the following form:

where

they are operators of a fractional order derivative in the Caputo sense, acting on various functions.

Assuming that 0 <

α < 1, the individual derivatives will take the form:

Given the relationship:

the following is obtained:

The integrals appearing in expressions (23) can be determined using the Lommel functions, which belong to the family of hypergeometric functions. Hypergeometric functions [

19] form a broad class, characterized by the property that their Chebyshev coefficients can be expressed relatively simply using values from this same class of functions [

20]. The introduction of the Lommel function results from the analytical representation of integrals appearing in Equation (23), which gives the solutions universal characteristics. These functions are defined using infinite series or in terms of hypergeometric functions with specific properties and relations to other special functions.

Currently, these functions are used in the broadly understood dynamics of non-integer order systems. This allows for analytical representation of solutions.

Thus, the integrals in expressions (23) are expressed as [

21]:

where

are Lommel functions as defined by [

14]:

The function appearing in Equation (25)

is a hypergeometric function defined as follows [

20]:

where (

α)

k is the Pochhammer symbol (rising factorial), defined as:

.

Therefore, the functions denoted by

L1 and

L2 take the form:

Ultimately:

and the final coefficient:

Thus, Equations (22), (29), and (30) define the Lamé coefficients in the cylindrical coordinate system for derivatives of non-integer (more precisely, fractional) order α (0 < α < 1).

Accordingly, the fractional nabla operator in the cylindrical coordinate system takes the form:

From this, the formulas for the gradient, divergence, rot, and scalar or vector Laplacian of fractional order in the cylindrical coordinate system can be derived in a straightforward manner.

3.2. Lamé Coefficients for Fractional Differential Operators for Spherical Systems

In the spherical coordinate system (17), the Lamé coefficients (5) for fractional derivatives take the following form:

Assuming that 0

< α < 1, the individual derivatives can be expressed by the following relationships:

Given that

and subsequently:

The integrals appearing in the above expressions were presented in the previous section. Thus, the following is obtained:

The subsequent coefficients take the form:

The integrals appearing in expressions (38) are equal to:

Finally, the following result is obtained:

Equations (35), (37), and (40) define the Lamé coefficients in the spherical coordinate system for fractional derivatives

α (0 <

α <1). Accordingly, the fractional nabla operator in the spherical coordinate system takes the form:

And in its expanded form:

From this, the formulas for the gradient, divergence, rotation, and scalar or vector Laplacian of fractional order in the spherical coordinate system can be derived in a straightforward manner.

The application of the proposed method is illustrated in Examples 1 and 2.

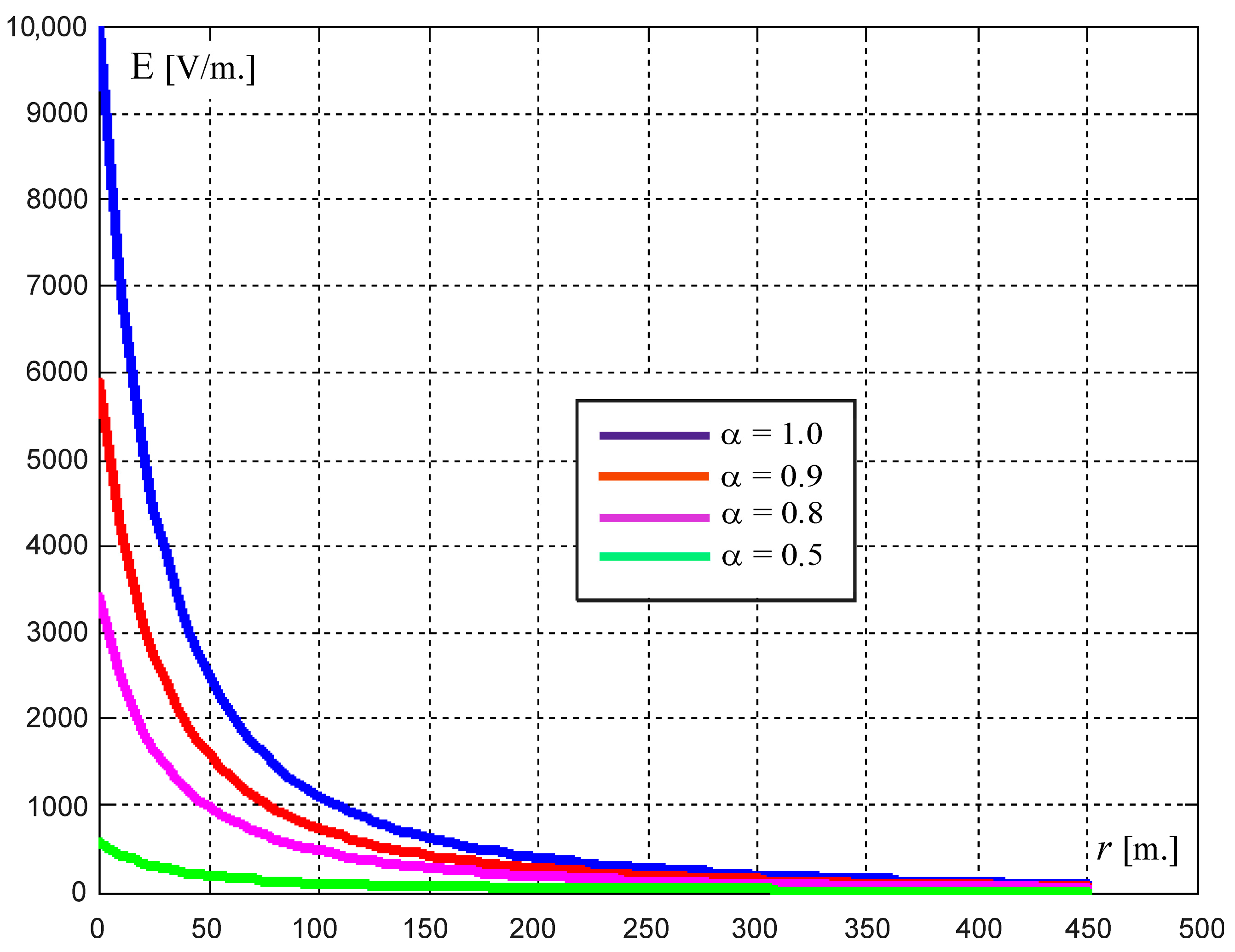

3.3. Example 1

As Example 1, the previously mentioned electrostatic field in the vicinity of a point charge in three-dimensional space will be considered. In Cartesian coordinates, the electric field intensity vector has three components, whereas in spherical coordinates, it has only one [

22].

The potential

V(

r) from a point charge is a function of a single variable

r, therefore, the electric field intensity for fractional-order derivatives takes the form:

The function

appearing in Equation (29) is proportional to the function 1/

r—(2), and thus its fractional-order derivative for

, according to definition (19), is:

The results of the calculations for the fractional derivative of the function 1/

r, which is proportional to the electric field intensity, for selected orders

α = 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.5 (0 <

α < 1) are presented in

Figure 1.

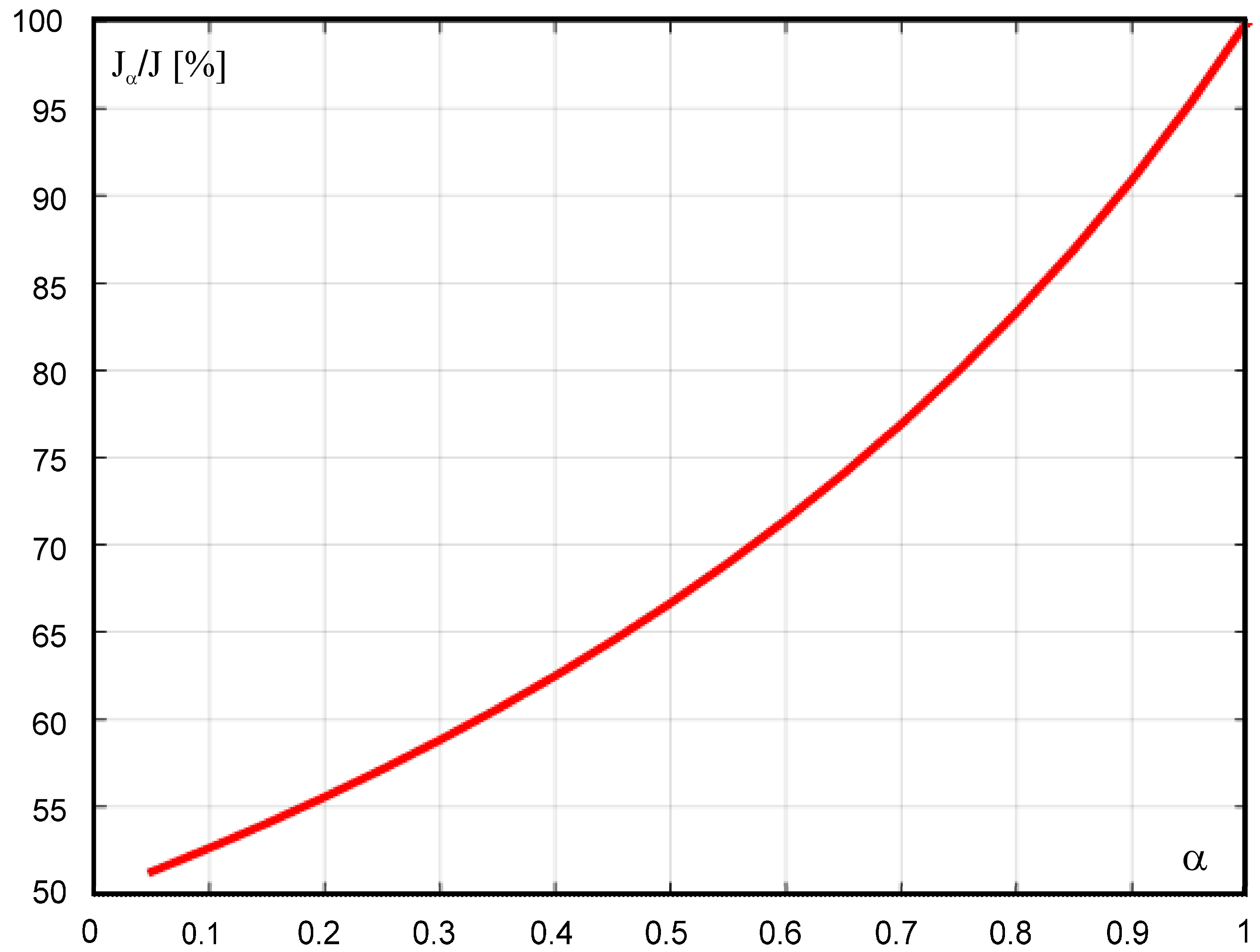

3.4. Example 2

In Example 2, the previously mentioned problem of determining the current density vector in a cylindrical conductor of radius R, carrying a uniformly distributed current I, will be considered. The analysis is based on the magnetic field intensity on the surface of the conductor, expressed in cylindrical coordinates [

23]. In the classical formulation, the magnetic field intensity at a distance

ρ from the axis of the conductor is given by the expression:

while the rotation of the magnetic field intensity, equal to the current density with a single component along the z-axis, is represented by expression (46):

The fractional-order

rot H in cylindrical coordinates takes the following form:

By substituting the determined Lamé coefficients for the order

in cylindrical coordinates (Formulas (22), (29) and (30)), along with the definition of the fractional derivative according to Caputo (19), the following is obtained:

where

.

The graph in

Figure 2 presents the percentage value of

Jα in (48) relative to

J in (46).

For , and therefore for a classical rotation, the percentage ratio JαJ equals 100%. If the value of α decreases, the percentage value of Jα/J also decreases, which can be used in the case of inhomogeneous current distribution across the conductor cross-section, e.g., when taking into account the skin effect.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents the formulation of Lamé coefficients for fractional-order derivative operators in cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems. The expressions obtained enable the definition of fractional operators in geometries typical for electromagnetic field modeling, and the results obtained remain consistent with classical operators of integer order.

Analytical examples confirmed the consistency of the proposed approach and indicated the potential of fractional operators to describe phenomena that are difficult to capture within classical calculus. The derived coefficients can serve as a basis for creating electromagnetic field models in cylindrically symmetric structures, which is particularly important in the analysis and design of machines and generators, where such geometries occur naturally.

The developed operators may in the future support more precise modeling of field distributions in air gaps, windings, and areas with complex electromagnetic diffusion. Their application may enable the construction of alternative analytical and numerical models for selected issues related to the operation of electrical machines and generators, especially where non-local or dynamic phenomena play an important role.

It is worth noting that the use of non-integer order operators in cylindrical and spherical symmetry systems can also bring computational benefits. Generalized Lamé coefficients allow non-local effects to be described without the need to refine the numerical grid or use complex iterative methods, which can lead to reduced computation time compared to classical finite element-based approaches. Future work plans to investigate the computational efficiency of the proposed operators in practical numerical implementations to assess their usefulness in the analysis and design of rotating machines.

Since the currently used calculation methods are based on integer-order operators, future work will focus on implementing non-integer-order operators in numerical tools and analyzing their usefulness for modeling rotating devices. The author also intends to draw the attention of the community researching machines and generators to the potential of non-integer order calculus as a tool that can expand the available methods of field description and support the development of new computational approaches.