Abstract

The three key design criteria for nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEBs) and climate-neutral buildings are minimizing energy use, ensuring high occupant comfort, and reducing environmental impact. Thermal comfort is one of the main components of indoor environmental quality (IEQ), strongly affecting occupants’ health, well-being, and productivity. As energy-efficiency requirements become more demanding, the appropriate selection of heating systems, their automated control, and the management of solar heat gains are becoming increasingly important. This study investigates the influence of two low-temperature radiant heating systems—underfloor and wall-mounted—and the use of Venetian blinds on perceived thermal comfort in a highly glazed public nZEB building located in a densely built urban area within a temperate climate zone. The assessment was based on the PMV (Predicted Mean Vote) index, commonly used in IEQ research. The results show that both heating systems maintained indoor conditions corresponding to comfort or slight thermal stress under steady state operation. However, during periods of strong solar exposure in the room without blinds, PMV values exceeded 2.0, indicating substantial heat stress. In contrast, external Venetian blinds significantly stabilized the indoor microclimate—reducing PMV peaks by an average of 50.2% and lowering the number of discomfort hours by 94.9%—demonstrating the crucial role of solar protection in highly glazed spaces. No significant whole-body PMV differences were found between underfloor and wall heating. Overall, the findings provide practical insights into the control of thermal conditions in radiant-heated spaces and highlight the importance of solar shading in mitigating heat stress. These results may support the optimization of HVAC design, control, and operation in both residential and non-residential nZEB buildings, contributing to improved occupant comfort and enhanced energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

A key area essential for achieving climate neutrality in the policy of the European Union—as well as in many other countries worldwide—is the improvement of energy efficiency in the sectors with the highest energy consumption. One of the leading sectors in this regard is the building sector, which accounts for approximately 40% of total energy use and 36% of CO2 emissions in Europe [1]. The need to reduce energy consumption in the building sector arises both from international commitments and their implementation into national legal regulations. In the EPBD directives [2,3,4,5], the European Union obliges Member States to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings and gradually move toward the nearly zero-energy building (nZEB) standard. Likewise, the regulation on the governance of the energy union and climate action [6] emphasizes the necessity of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing energy savings.

In Poland, this requirement is reflected in the Building Law Act [7] and in the Technical Conditions [8], which define national requirements concerning the energy performance of buildings. Reducing energy use in buildings is therefore not only part of implementing the EU climate policy but also a national legal obligation aimed at improving environmental quality, lowering operating costs, and strengthening the country’s energy security.

In nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEB), which constitute the standard within the European Union, both the selection of appropriate energy sources and a comprehensive approach to indoor microclimate management are of key importance. Achieving high energy efficiency must result not only from the application of modern, low-emission technologies for heat and cooling generation but also from the development of a coherent system in which the energy source operates in synergy with highly efficient building installations, such as HVAC systems. These systems play a crucial role in shaping indoor environmental quality (IEQ), ensuring a high level of user comfort.

In both residential and public buildings, modern devices such as heat pumps—drawing energy from air, ground, or water—are particularly noteworthy [9]. The growing popularity of heat pumps as heating and cooling sources is confirmed by market data. In recent years, the European heat pump market has experienced significant growth; for example, in 2022, sales increased by about 38.9% compared with the previous year, reaching approximately 3 million units [10]. In Poland, the number of heat pumps sold increased by around 112% relative to the earlier period [11].

Heat pumps achieve their highest operational efficiency in low-temperature heating systems, as the temperature difference between the heat source and the supply temperature of the heating installation is much smaller compared to high-temperature heating systems. A smaller temperature difference translates into a higher Coefficient of Performance (COP/SCOP), meaning lower electricity consumption for the same amount of delivered heat. Systems such as underfloor or wall heating enable heat pumps to operate at supply temperatures of around 30–40 °C, significantly reducing compressor load and thermodynamic losses. Consequently, the heat pump operates more steadily, with fewer on–off cycles, which further extends its lifespan and improves the overall energy efficiency of the entire system.

Numerous studies have analyzed systems combining heat pumps with surface heating/cooling technologies, highlighting their potential to enhance both thermal comfort and energy efficiency. Previous research has shown that underfloor heating systems supplied by heat pumps benefit from the thermal inertia of the floor and building structure, enabling heat storage and more flexible heat pump operation under varying control conditions [12]. Experimental and simulation-based studies have further demonstrated that appropriate control strategies, including low supply temperatures and hybrid configurations, can significantly reduce energy consumption while maintaining thermal comfort [13,14]. In [15], the results showed that reducing the supply temperature by 10 °C to 45 °C in an underfloor heating system was sufficient to maintain an indoor temperature of 25 °C, while leading to significant energy savings. This demonstrates that even relatively simple control strategies can provide measurable benefits, whereas integrated control of multiple subsystems may further enhance overall system performance. Other studies investigated advanced solutions, such as radiant floors incorporating phase-change materials (PCM), which resulted in improved indoor temperature stability, increased load flexibility, and reduced operating costs [16,17]. In situ investigations also confirmed that improved building envelope insulation and hybrid renewable energy systems positively affect the seasonal performance of underfloor heating systems connected to air-source heat pumps (ASHPs) [18].

Modern HVAC systems in buildings with enhanced energy standards are equipped with a range of advanced technologies that, while minimizing energy consumption, sim-ultaneously maintain a high level of user comfort—one of the key aspects of building de-sign and operation. Buildings should not only meet technical and energy requirements but, above all, provide a healthy, safe, and user-friendly environment. The topic of thermal comfort in indoor spaces has been the subject of scientific research for many years, as evidenced by the large number of publications dedicated to this issue [19,20]. Considering that residents of industrialized countries spend the majority of their time indoors, it is essential to seek new knowledge on indoor microclimate optimization and its impact on occupants [21].

Thermal comfort can be assessed using the PMV (Predicted Mean Vote) index, which evaluates thermal sensation on a seven-point scale [22]. The scale is shown in Figure 1, where “0” represents comfort conditions most favorable for occupants in terms of thermal comfort. Thermal comfort can also be evaluated using the PPD (Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied) index, which estimates what share of the population will feel dissatisfied with the prevailing thermal conditions in a given environment. Standard [23] defines several categories of indoor environment, with recommended ranges presented in Table 1. The indoor thermal comfort level, according to Fanger’s scale, is determined based on microclimate parameters such as air temperature, mean radiant temperature, air velocity, and relative humidity. Additionally, two human-related factors are required for the calculations: clothing insulation level and metabolic rate [24].

Figure 1.

Fanger’s thermal comfort scale [25].

Table 1.

Design categories for mechanically heated and cooled buildings [23].

The wide range of available heating methods raises the question of which systems are not only energy-efficient but also positively influence the perception of thermal comfort. An example of a well-matched combination of a heat source and a heating/cooling system is low-temperature radiant heating integrated with a heat pump. This solution provides high thermal comfort due to the uniform temperature distribution within the room and the predominance of radiant heat transfer. Limited air movement reduces dust circulation and the sensation of draughts, while a gentle, consistent temperature gradient between the floor and the ceiling enhances comfort and supports a healthy indoor microclimate.

With the development of intelligent HVAC systems, growing attention is being paid to the integration of heating systems, shading devices (particularly in highly glazed spaces), and building automation, with the aim of optimizing both thermal comfort and energy efficiency [26,27]. In the context of climate change and rising expectations regarding IEQ, such integrated approaches offer promising directions for future research and practical applications.

The impact of radiant heating on thermal comfort, as well as comparisons with other heating systems (e.g., fan-coil units), has been widely investigated; however, relatively little attention has been paid to wall-based radiant solutions. In [28], thermal comfort achieved with underfloor heating was compared with that provided by a wall-mounted air conditioner, showing neutral temperatures of 22.0 °C and 23.0 °C, respectively. The study also demonstrated that local discomfort caused by convective wall units—primarily due to uneven temperature distribution—significantly influenced overall comfort perception, whereas underfloor heating improved comfort while reducing energy consumption. Numerical analysis in [29] examined the influence of local subdivision of underfloor air distribution systems on thermal comfort under varying supply temperatures and airflow velocities. Experimental studies in [30] showed that local heating mats can significantly improve thermal sensation and overall comfort in cold environments, particularly when larger mats and higher power levels are applied. Similarly, ref. [31] investigated the influence of the floor-level thermal environment on task performance by analyzing psychophysiological responses using multilevel structural equation modeling. The results demonstrated that underfloor heating increases feet temperature, leading to improved thermal comfort and perceived concentration compared to convective air conditioning.

Researchers have also proposed innovative concepts to improve the energy efficiency of radiant heating systems. In [32], a novel underfloor heating panel design with integrated metal inserts was analyzed using numerical simulations. The results indicated that, compared to conventional radiant floor heating, the proposed solution can significantly reduce annual energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions while lowering operating costs.

In addition to heating and cooling systems, many other factors influence occupants’ comfort—among them glazing, which allows short-wave radiation to enter the building as passive solar gains. This phenomenon is particularly relevant and noticeable in energy-efficient buildings with large glazed surfaces, especially those oriented to the south and west. Excessive solar gains often lead to thermal discomfort, increased fatigue, reduced productivity, and may result in health issues such as dehydration or impaired thermoregulation of the human body. Overheating is not only a matter of discomfort but also has significant consequences in terms of increased energy demand for space cooling. As a result, the building loses its energy efficiency, and its carbon footprint increases, which contradicts the goals of sustainable development and climate policy. The European EPBD directive [3], guidelines from organizations such as ASHRAE [33], and national regulations [8] indicate that the problem of overheating should be mitigated—for example, through solutions that minimize energy use while ensuring thermal comfort. Examples include dynamic building envelope, high-quality thermal insulation, appropriately designed façades and shading devices, as well as modern, efficient ventilation and air-conditioning systems. Consequently, in buildings with a high standard of IEQ, user comfort and energy efficiency are mutually reinforcing objectives.

Indoor overheating and the management of passive solar gains have been widely investigated in the literature. Article [34] links overheating with radiant floor heating in buildings with large glazed areas, where direct solar radiation may cause local floor overheating, reduced thermal comfort, and degraded system performance. The authors proposed and experimentally validated a discretization-based model accounting for non-uniform solar radiation. Simulations showed floor surface temperatures up to 35.6 °C near south-facing windows—about 8.5 °C higher than in shaded zones—with heating outputs reaching 171 W/m2 compared to 79 W/m2 in non-irradiated areas. The model enables improved design and control strategies to limit local overheating. Gamero-Salinas et al. [35] analyzed thermal comfort during heatwaves in residential buildings in Pamplona, Spain, showing that satisfactory comfort corresponded to indoor temperatures of 25.7–26 °C, while discomfort occurred above 28 °C. Overheating was mitigated using a combination of active, passive, and low-energy cooling measures (e.g., fans). Alrasheed and Mourshed [36] reviewed the current state of knowledge on overheating in residential buildings and the factors influencing overheating risk, aiming to reduce its impact on thermal comfort and occupants’ well-being. They identified external solar shading as the most effective retrofit solution for insulated buildings, while cooling coatings were found to be more suitable for non-insulated buildings. Kenny et al. [37] conclude that the likelihood of exposure to overheated indoor environments will increase as climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of heatwaves and extreme heat events. Consequently, vulnerable groups will be at high risk of serious health impacts related to indoor overheating. Kiil et al. [38] reported significant overheating in modern office buildings during the heating season, despite low air velocities, with occupants preferring temperatures of 23–25 °C due to lighter clothing levels. They proposed adaptive temperature control based on outdoor conditions. Kosori et al. [39] found that highly insulated and airtight buildings, including passive houses—designed to minimize heat losses in temperate and cold climates—may face increased summer overheating risk, particularly in bedrooms, despite generally low dwelling-level risk. Lomas and Porritt [40] concluded that overheating during heatwaves is most pronounced in non-air-conditioned buildings, particularly in dwellings located in temperate climates, where building design primarily focuses on winter thermal comfort.

A substantial body of research addresses strategies for mitigating overheating through the use of shading elements. In highly glazed buildings research highlights the importance of both windows low-U-value [41] and effective shading systems [42]. Lu [43] demonstrated that a combined system of dynamic glazing and kinetic shading outperforms static and single-technology solutions in terms of integrated energy, visual comfort (daylight and glare), and thermal comfort. Kuhn [44] reviewed advanced solar control technologies, including multifunctional systems incorporating building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) and building-integrated solar thermal energy (BIST) solutions. Wijewardane et al. [45] reviewed dynamic shading devices that respond in real time to changing weather conditions, demonstrating their potential to reduce cooling demand while maintaining thermal and visual comfort. The study highlights both actively controlled systems and emerging passive solutions based on smart materials, such as electroactive polymers, shape memory alloys, shape memory polymers, and bimetals. Recent studies also highlight the role of dynamic shading, its integrated control with HVAC and lighting systems, and personalized environmental control systems (PECS), all of which enable real-time microclimate management—particularly in office buildings with large glazed façades [46,47,48].

Despite the growing use of heat pump–supplied radiant heating systems and solar shading solutions, their combined experimental evaluation in highly glazed nZEB buildings remains insufficiently addressed. In the previous study [42], the authors analyzed the impact of external Venetian blinds on thermal comfort in an nZEB building during a series of sunny days in the transitional season, when neither heating nor cooling systems were in operation. Their work demonstrated the potential of external shading to prevent overheating under free-floating conditions. In contrast, the present study extends this research by focusing on late-winter conditions with active heating and variable solar exposure, thereby providing new experimental insight into how radiant heating systems interact with solar gains to shape indoor thermal conditions in highly glazed public nZEB buildings. The study combines in situ microclimate measurements with PMV-based comfort assessment for two types of low-temperature surface heating—wall-mounted and underfloor—in two geometrically identical rooms: one equipped with an external Venetian blinds and the other with an unprotected glazed façade. The experimental facility is located within a dense urban area of a provincial capital city in southern Poland, representing a temperate climate zone typical for many Central European cities. The research question, addressing the identified knowledge gap, is therefore as follows: which of the two surface heating systems—underfloor or wall-mounted—provides better thermal comfort in a glazed space with and without Venetian blinds?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Test Rooms

The experiment was conducted at the Małopolska Centre of Energy-Efficient Building (MCBE), located on the campus of the Cracow University of Technology in Kraków, southern Poland, within a densely built urban area in a temperate climate zone. The facility meets the requirements typical of passive buildings in terms of thermal insulation and airtightness [49]. Two comparable test rooms, denoted as L1 and L2, were selected for the study. They are located on the southern façade of the building, on the first and second floors, respectively.

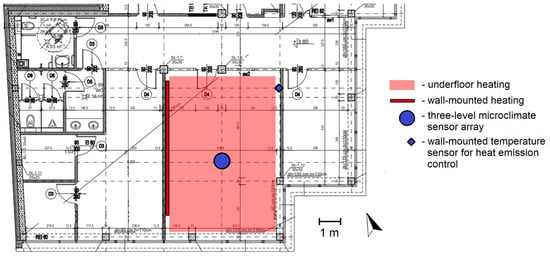

Rooms L1 and L2 are equivalent in terms of geometry, thermal insulation of the building envelope, and the configuration of the heating and ventilation systems. Both rooms have identical internal dimensions of 7.6 m (L) × 5.1 m (W) × 3.4 m (H). Their exterior walls consist entirely of floor-to-ceiling triple-glazed windows with aluminum frames. Each room is separated from adjacent rooms by 12.5 cm partition walls (two-layer gypsum board on a steel frame filled with mineral wool), and from the corridor by a glazed partition with an aluminum frame. The main difference between the rooms is the presence of external Venetian blinds: room L2 is equipped with solar shading, whereas room L1 has no shading system (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

View of the experimental Room L1 without solar protection on the first-floor plan of the building. The second floor, containing Room L2 equipped with external Venetian blinds, has an analogous layout. Author’s own study based on [49].

Two types of low-temperature surface heating systems were analyzed in the study: underfloor and wall-mounted (hereafter referred to as wall heating). Both are hydronic systems supplied from the building’s water-based energy storage, which is charged by a system of air-source heat pumps (ASHPs). Heating pipes were arranged in meandering coils with 0.15 m spacing and embedded either in the screed layer beneath ceramic tile flooring or incorporated into the walls as a wall-mounted system. Each local room distributor was equipped with a pump–mixing unit consisting of a circulation pump, a control valve with an actuator, and both temperature and dew point sensors (the latter preventing moisture accumulation on the surfaces during cooling mode) on the supply side of the surface heating system.

Local heat emission was managed through the Building Management System (BMS) using a traditional rule-based control (RBC) strategy. Room temperature was regulated using a two-position controller with a 0.2 °C hysteresis band, implemented in a dedicated local automation controller in each room. The temperature signal was obtained from a wall-mounted sensor placed on a partition wall, away from windows and zones directly affected by solar radiation, at a height of approximately 1.4 m above the floor. Furthermore, PI controllers were deployed to regulate the supply temperature of both surface heating systems at a constant level of 40 °C.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

The experiment was conducted simultaneously in both test rooms at the end of winter and consisted of two 10-day measurement cycles corresponding to the operation of the underfloor and wall heating systems, respectively. Each cycle was preceded and separated by stabilization periods to ensure conditions in the test rooms close to steady state (see Table 2). The selected duration of the cycles enabled an assessment of the variability of the environmental conditions, ensuring that the results were both reliable and representative.

Table 2.

Experimental procedure in the two test rooms.

The temperature setpoint for heat emission control in the experimental rooms was kept constant at 24 °C throughout the entire day, with no reduction during nighttime (setback). Due to the applied hysteresis, the heating system was deactivated once the setpoint was reached and reactivated when the indoor temperature fell 0.2 °C below it. Fresh air was supplied to each Room L2 the mechanical ventilation system at a stabilized temperature of approximately 22 °C and an airflow of around 125 m3/h. In Room L2, the blinds were fully opened in a horizontal slat position. However, due to the low angle of the winter sun and the slat geometry, the blinds provided only partial shading of direct solar radiation, while still allowing increased daylight availability in the room.

From a physical perspective, thermal comfort in highly glazed interiors is governed by radiative and convective heat transfer processes, strongly influenced by transient solar radiation and the thermal inertia of radiant heating systems. To ensure comparable thermal influence of the adjacent rooms on the test spaces, the air-based heating systems were used to stabilize the temperatures in the neighboring rooms, both horizontally and vertically, throughout the entire experiment. Furthermore, both experimental rooms were intentionally unoccupied to eliminate any interference with data collection.

The outdoor conditions during the measurement cycles were representative of late-winter weather typically observed in recent years in the urban area of Kraków. Based on data from the meteorological station installed on the southern façade of the MCBE—corresponding to the orientation of the dominant glazing of the investigated rooms—the outdoor air temperature ranged from approximately −1.7 °C to +10 °C. Wind speed did not exceed 6 m/s (moderate wind), while solar irradiance reached values of up to 600 W/m2.

2.3. Data Acquisition

To measure the indoor microclimate conditions and assess thermal comfort, EHA MM101 devices (Ekohigiena Aparatura Ryszard Putyra Sp.J., Środa Śląska, Poland) were used. The instruments comply with the EN ISO 7726:2002 Class C requirements [50]. The metrological characteristics of the sensors are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Metrological parameters of the sensors in the EHA MM101 device [51].

Thermal comfort was assessed using the PMV (Predicted Mean Vote) index, which was calculated directly by the EHA MM101 device in accordance with EN ISO 7730 [25]. The PMV calculation was based on the measured indoor environmental parameters, including air temperature, mean radiant temperature (derived from black globe temperature), relative humidity and air velocity, as well as on predefined human-related parameters required by the standard.

The calculation required assumptions to be made regarding clothing insulation and human metabolic rate. Clothing thermal resistance (clo) defines the level of insulation that enables maintaining an average skin temperature of approximately 33 °C while staying in a room with an air temperature of 21 °C, relative humidity below 50%, and an air velocity of 0.1 m/s. In the analysis, a value of clo = 1.0 was adopted, which according to the standard [25] corresponds to typical winter office clothing.

The second parameter was the metabolic rate (met). Metabolism describes the amount of heat produced by the human body through oxidation processes and is expressed as metabolic heat per unit body surface area. Its value depends on the level of human activity and is given in “met” or W/m2 (1 met = 58.2 W/m2). Typical values for different activity levels are provided in the EN ISO 7730 [25]. In the study, a metabolic rate of met = 1.2 was adopted, corresponding to sedentary office work.

Identical sets of microclimate sensors were installed in the central area of both rooms (see Figure 2). The sensors were positioned at three heights corresponding to a seated occupant, in accordance with the standard [25]: 0.1 m (feet level), 0.6 m (center of gravity), and 1.1 m (head level). Measurements were collected every 10 min, enabling a detailed analysis of microclimate parameter variability over time.

3. Results

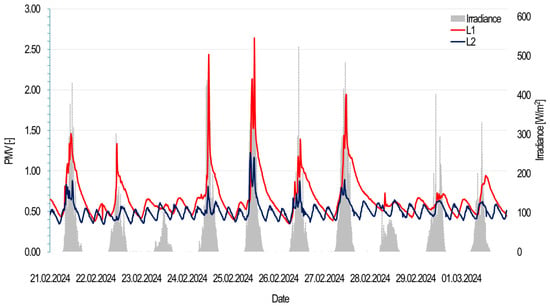

3.1. Indoor Thermal Comfort at Seated Body Gravity Height

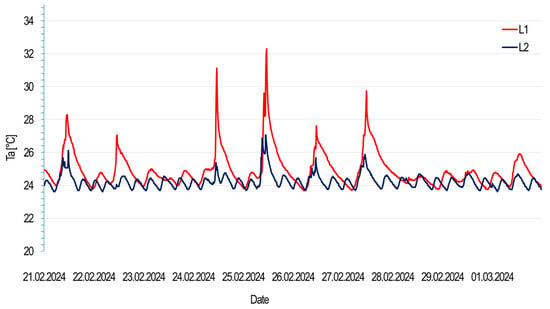

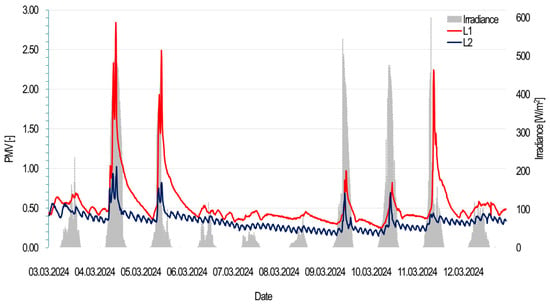

The first measurement cycle focused on assessing the indoor microclimate and thermal comfort conditions during the operation of the underfloor heating system. Figure 3 presents the temporal variation in the PMV index in both rooms at a height of 0.6 m, corresponding to the gravity center of a seated person, alongside the irradiance measured on the building’s southern façade. The recorded PMV values ranged from 0.35 to 2.64 in Room L1 and from 0.34 to 1.23 in Room L2, with substantially greater amplitude of PMV variation observed in Room L1 during periods of solar exposure, compared to Room L2. Figure 4 shows the corresponding air temperature (Ta) recorded in the rooms at the same height. The variation patterns of air temperature were strongly aligned with the PMV dynamics, indicating a strong correlation between indoor air temperature and the PMV index.

Figure 3.

PMV values in rooms L1 and L2 at a height of 0.6 m, together with irradiance on the southern façade of the building during underfloor heating operation.

Figure 4.

Air temperature (Ta) in rooms L1 and L2 at a height of 0.6 m during underfloor heating operation.

The second measurement cycle similarly aimed to assess the indoor microclimate and thermal comfort conditions, this time during the operation of the wall heating system (see Figure 5). Under these conditions, the PMV values in Room L1 ranged from 0.25 to 2.84, and from 0.15 to 1.02 in Room L2. Consistent with the observations for the underfloor heating system, solar exposure triggered a stronger PMV response in Room L1, resulting in a noticeably greater amplitude of variation compared to Room L2.

Figure 5.

PMV values in rooms L1 and L2 at a height of 0.6 m, together with irradiance on the southern façade of the building during wall heating operation.

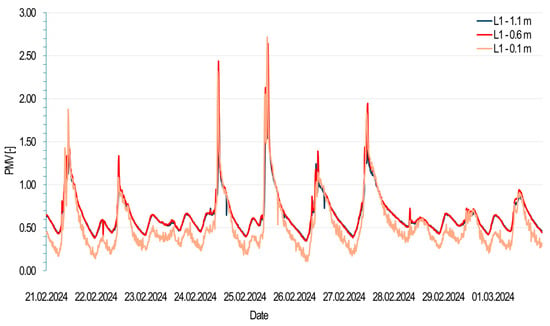

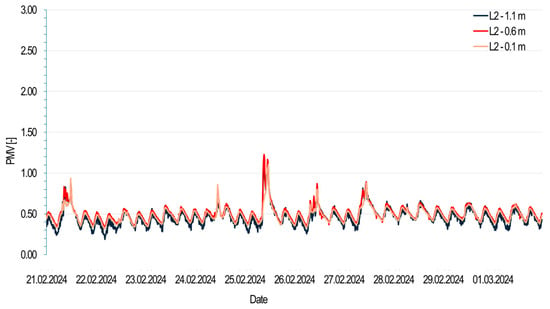

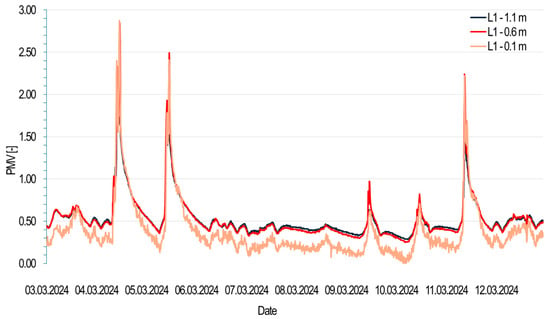

3.2. Vertical Gradient of Indoor Thermal Comfort

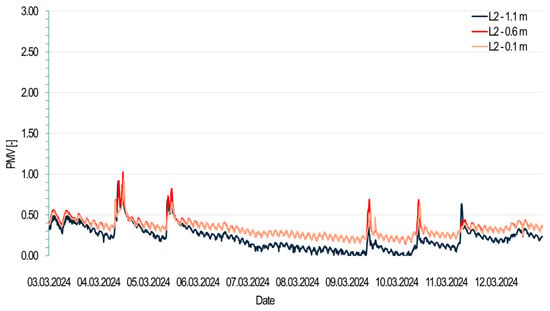

During the experiment, data were also collected from sensors positioned at 1.1 m (head level for a seated person) and 0.1 m (feet level). To investigate how the thermal comfort index varies with height for both surface heating systems, the PMV time profiles from the room without blinds (L1) and the room with blinds (L2) were compared across all measurement levels. The results are presented separately for the underfloor heating system (Figure 6 and Figure 7) and for the wall heating system (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 6.

PMV values in room L1 at a height of 0.1 m, 0.6 m and 1.1 m, during underfloor heating operation.

Figure 7.

PMV values in room L2 at a height of 0.1 m, 0.6 m and 1.1 m, during underfloor heating operation.

Figure 8.

PMV values in room L1 at a height of 0.1 m, 0.6 m and 1.1 m, during wall heating operation.

Figure 9.

PMV values in room L2 at a height of 0.1 m, 0.6 m and 1.1 m, during wall heating operation.

3.3. Comparative Summary

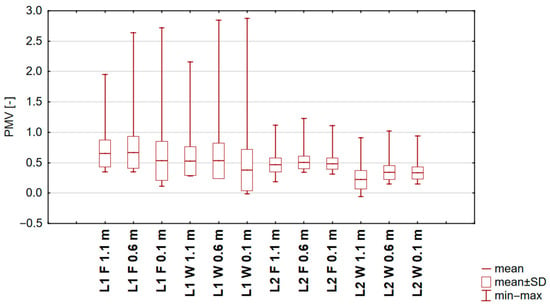

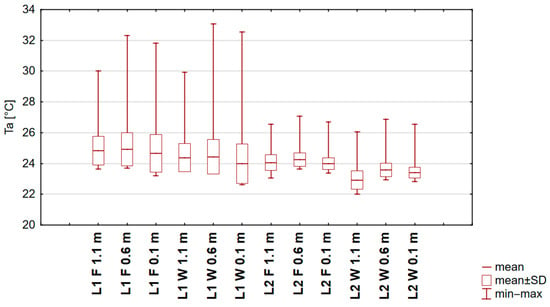

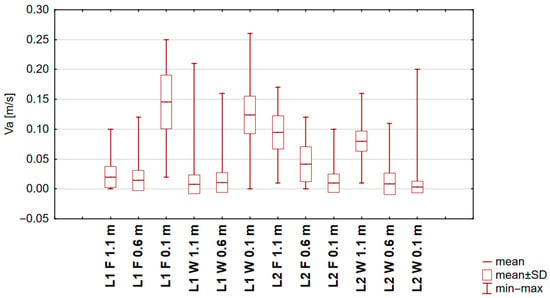

Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the selected microclimate parameters recorded during the experiment. Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 illustrate the distribution of the following variables at three measurement heights in both rooms and for both heating systems: PMV values (Figure 10), air temperatures (Figure 11), and air velocities (Figure 12). Regardless of the room type and heating system, the average PMV values were consistently highest at the middle measurement height, corresponding to the center of gravity of a seated person. This pattern was also reflected in the mean, maximum, and minimum air temperature values. Furthermore, PMV values in Room L1 showed considerably higher variability than in Room L2 at all three measurement heights for both the underfloor heating system (L1: SD = 0.22–0.32, L2: SD = 0.09–0.12) and the wall heating system (L1: SD = 0.24–0.34, L2: SD = 0.10–0.15). In contrast, within each room, the variability of PMV did not differ significantly between the two heating systems.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of selected microclimate parameters measured at three heights in rooms L1 (without shading) and L2 (with solar shading), depending on the applied surface heating system type.

Figure 10.

Distribution of PMV values at three heights in Rooms L1 (no shading) and L2 (solar shading) under floor (F) and wall-mounted (W) heating systems.

Figure 11.

Distribution of air temperatures at three heights in Rooms L1 (no shading) and L2 (solar shading) under floor (F) and wall-mounted (W) heating systems.

Figure 12.

Distribution of air velocity at three heights in Rooms L1 (no shading) and L2 (solar shading) under floor (F) and wall-mounted (W) heating systems.

In Table 5, a comparative summary of underfloor and wall-mounted heating is presented for both experimental rooms, each characterized by a different level of solar protection. According to [25], the PMV measurement at the height corresponding to the user’s center of gravity (0.6 m) is considered the reference value, as it best represents whole-body thermal comfort. However, in rooms where notable vertical temperature differences may occur—particularly when surface heating systems are used—relying on a single measurement height may not adequately reflect the actual overall thermal sensation experienced by occupants. Therefore, in addition to the reference PMV value at 0.6 m, the mean whole-body PMV was reported, calculated as a weighted average of the PMV values measured at three height levels. The weights represent the contribution of corresponding body segments to thermal sensation: head—0.25, center of gravity—0.45, and feet—0.30. This approach provides a more comprehensive and representative assessment of thermal comfort, especially under conditions of temperature stratification. Including all three measurement levels also increases the reliability of evaluating both heating systems and shading strategies.

Table 5.

Comparison of underfloor and wall-mounted heating under contrasting solar protection levels in the two experimental rooms (L1 and L2).

In this analysis, the occupied hours were assumed to be 08:00–18:00, corresponding to typical occupancy schedules of public buildings [52,53]. Based on this timeframe, the number of discomfort hours for both measurement cycles was determined using the criterion PMV ≥ 1.0, i.e., values exceeding the classification limits of indoor environment categories according to EN 16798-1 [23] (see Table 1).

Both the reference mean PMV and the mean whole-body PMV values (see Table 5) were higher in Room L1 than in Room L2 for both types of surface heating systems. For underfloor heating and wall-mounted heating, the values in Room L1 were 0.67/0.62 and 0.53/0.49, respectively, while in Room L2 they reached 0.53/0.49 and 0.34/0.31, respectively. This trend is consistent with the air temperature recorded at the reference height of 0.6 m, where higher values were observed in Room L1 (24.93 °C and 24.44 °C) compared to Room L2 (24.24 °C and 23.58 °C)—see Table 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Solar Exposure and Shading on Thermal Comfort

On clear days, during periods of intense solar exposure around midday, a noticeable increase in indoor air temperature occurs along with rising irradiance—markedly stronger in Room L1 (see Figure 4). This demonstrates the significant impact of solar gains on the winter heat balance in a room with large south-east-facing glazing. After the peak solar influence, in the afternoon hours, natural air cooling takes place. This process is slightly prolonged due to the thermal inertia of the room, until the temperature stabilizes at approximately 24 °C, maintained by the heating system. The natural cooling process in Room L1 lasts considerably longer than in Room L2 because of the much higher indoor temperatures reached and, consequently, the increased heat storage in the room’s structure. The observed temperature fluctuations of approximately 23.7–24.5 °C result from the heating system operation and the adopted control method. These thermal dynamics are also clearly reflected in the PMV trends (compare Figure 3 and Figure 4).

The observed positive correlation between solar irradiance and PMV (see Figure 3 and Figure 5) confirms that the level of solar exposure has a decisive impact on thermal comfort variation in both rooms. On cloudy days, when diffuse radiation dominates, the PMV values in both rooms remain stable and similar. In contrast, on clear days, Room L1 experienced a significant deterioration of thermal comfort during periods of high solar exposure, while Room L2—equipped with Venetian blinds—remained considerably more stable. This indicates that increased solar gains and radiant temperature effects are the dominant factors contributing to discomfort in Room L1.

The recorded time profiles, supported by statistical analysis, confirm that the blinds in Room L2 effectively mitigated solar impact, leading to substantially lower PMV increases at all three measurement heights. As a result, even during peak irradiance, thermal conditions remained relatively stable—mostly within the range of moderate thermal stress. During the periods of highest irradiance, the external shading reduced peak PMV values by an average of 50.2% and lowered the number of discomfort hours (PMV ≥ 1.0) during occupied hours by 94.9%, highlighting the crucial role of solar protection in highly glazed spaces—even in late winter.

According to the thermal comfort scale (see Figure 1), PMV values in Room L1 occasionally exceeded 2.0, indicating thermal conditions that may cause severe thermal stress (warm/hot – strong heat stress), temporally correlated with peaks in solar irradiance. Prolonged exposure to such conditions may pose potential health risks [54,55]. In contrast, Room L2 exhibited noticeably flatter PMV curves with a lower amplitude of variation (see Figure 5 and Figure 10). PMV generally remained within the range of 0.0–1.0, corresponding to thermal sensations between neutral (comfortable, no thermal stress) or slightly warm (slightly thermal stress) [56]. Only in two measurement days (one for underfloor heating and one for wall heating) did the PMV in Room L2 briefly exceed 1.0, indicating moderate thermal stress (slightly warm). This suggests that during periods of intense solar exposure, the fixed horizontal slat position—resulting in only partial blocking of direct sunlight—may not provide fully effective protection against overheating in winter. However, unlike in Room L1, the prevailing thermal conditions in Room L2 should not significantly impair cognitive performance or physiological functions.

Outside periods of strong solar influence—i.e., during cloudy days or after the afternoon cooling phase—thermal conditions in both rooms remained stable and similar, regardless of the heating system used, driven by the heating control method and a target indoor temperature of 24 °C. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 5, PMV values in both rooms generally ranged between 0.0 and 1.0, corresponding to comfortable or slightly warm conditions [56], and can be classified within category IV according to the standard [23]. This confirms that the key differentiating factor between rooms was the presence of blinds —which effectively limited solar gains and stabilized the indoor microclimate. From the occupant perspective, Room L2 consistently provided more favorable and predictable thermal conditions, independent of heating system type.

The PMV analysis was conducted using fixed assumptions for clothing insulation (clo = 1.0) and metabolic rate (met = 1.2), in accordance with EN ISO 7730. It should be noted, however, that PMV values are sensitive to variations in both parameters. During periods of strong solar exposure, adaptive occupant behavior such as reducing clothing insulation may lead to lower PMV values under otherwise identical indoor conditions. Therefore, the use of constant clo and met values may result in a slight overestimation of thermal discomfort, particularly in the room without solar shading. Nevertheless, since identical assumptions were applied across all analyzed cases, the comparative nature of the results and the main conclusions of the study remain unaffected.

4.2. Vertical Distribution of Thermal Comfort

To assess the uniformity of thermal sensation across the seated human body, the vertical PMV gradient was analyzed at three heights. The most uniform distribution was achieved in Room L2 under underfloor heating—PMV values at different heights were highly consistent, with the head level being only slightly cooler (average PMV lower by 0.04; see Figure 11 and Table 4 and Table 5). Under wall heating, PMV values at 0.6 m and 0.1 m remained similar, whereas at head level—outside periods of intense solar exposure—they were noticeably lower (average difference of 0.09) and exhibited greater variability (SD = 0.15 vs. 0.11 and 0.10 at the remaining heights). This indicates that heat was perceived most intensely at the center of gravity and feet levels, while the head area remained the coolest and the least thermally stable.

In contrast, in Room L1—regardless of heating system—PMV values remained similar at 0.6 m and 1.1 m throughout the measurements, while at the feet level—outside periods of intense solar exposure—they were substantially lower (by 0.13 and 0.15 on average for underfloor and wall heating, respectively). This level also showed the highest variability (SD = 0.32 for underfloor heating and 0.34 for wall heating), indicating that heat was perceived most strongly at the center of gravity and head levels, whereas the feet area remained the coolest and least thermally stable. A clear tendency toward a reduced vertical PMV gradient was observed during periods of overheating in both rooms (see Figure 6, Figure 8 and Figure 9), suggesting a thermal equalization effect under strong solar exposure.

No significant differences in overall thermal comfort were observed between underfloor and wall heating in a seated position, according to both the reference PMV and whole-body PMV. However, when examining the vertical PMV gradient, some nuanced patterns emerged. Although the overall vertical distribution of thermal sensation remained relatively uniform, it is noteworthy that in Room L1 the foot zone was consistently perceived as cooler, while in Room L2 a slightly cooler sensation occurred at head level—particularly with wall-mounted heating. One plausible explanation may be related to local air movements at these heights (see Table 4 and Figure 12): the measured air velocity was slightly higher (≈0.09–0.14 m/s) compared to the remaining levels (≈0.01–0.04 m/s). Such micro-scale airflow effects are known to influence thermal perception even when mean indoor conditions remain within comfort limits [57]. Importantly, these subtle variations align with the physical characteristics of radiant systems [28]. Surface heating systems inherently promote uniform heat distribution, which limits vertical thermal stratification and results in small PMV deviations across height levels. Moreover, because both underfloor and wall heating provide large-area heat emission, they yield similar operative temperatures; consequently, whole-body PMV values for both systems remain closely matched. It should also be noted that PMV, as a global index of thermal comfort, does not always capture local discomfort phenomena such as cool feet, radiant asymmetry, or slight vertical temperature differences. Therefore, the observed differences should not necessarily be attributed solely to the heating system type; rather, they may reflect subtle interactions between air movement, heat distribution, and occupant-sensitive height levels. This suggests that future research could further investigate how local air velocity fields (especially at feet and head level) interact with surface heating and solar gains in shaping thermal sensation.

4.3. Implications for Automated Control Strategies

In the automatic temperature control of indoor environments (e.g., with surface heating systems), solar irradiance acts as a dynamic disturbance factor. The presence of blinds mitigated this impact, contributing to more stable indoor thermal conditions regardless of the heating technology. From a room energy balance perspective, however, this increased stability is achieved at the expense of reduced utilization of potentially beneficial passive solar heat gains. From a qualitative energy perspective, the observed differences between Rooms L1 and L2 indicate divergent heating demand profiles. As shown in Figure 4, extended periods of temperature exceedance in Room L1 should translate into reduced heating energy demand due to the storage of solar heat within the building structure. In contrast, the external shading in Room L2 limited solar heat gains, resulting in more stable thermal conditions but potentially increasing reliance on active heating to maintain the setpoint temperature. This suggests an inherent trade-off between thermal comfort stability and the effective use of passive solar gains. Such a trade-off highlights the importance of control strategies that balance comfort requirements with energy efficiency objectives, particularly in the context of nZEB buildings, where both the utilization of solar gains and the avoidance of overheating are critical. Moreover, the rapid, solar-driven increases in air temperature and PMV observed in the unshaded room underline the high thermal inertia of surface heating systems when responding to fluctuating solar irradiance. In such conditions, the limitations of the applied room-temperature-based RBC become apparent, as the control action is triggered solely by measured indoor air temperature, which may result in prolonged and unnecessary active heating already during periods of passive solar heating. Earlier system deactivation based on solar irradiance measurements or predictive control approaches could therefore contribute to reducing PMV peaks and heating energy demand. This identifies an important area for optimization in automated control strategies and emphasizes the need for more adaptive, solar-aware control approaches.

Based on the findings, several practical recommendations for simple automated control measures can be proposed, which may help improve thermal comfort and reduce heating energy consumption:

- adjustment of hysteresis parameters in two-point control to minimize overheating and temperature fluctuations,

- integration of solar irradiance detection—temporary heating shutdown during high solar exposure to allow passive heating;

- demand-responsive control that incorporates the thermal inertia of surface heating systems, e.g., switching off heating a certain time before the scheduled end of occupancy, with the option of an occupancy-based override,

- implementation of nighttime setback strategies.

Furthermore, as part of practical operational guidelines, a slight reduction in the heating setpoint could improve thermal comfort by lowering average PMV values during periods without solar exposure towards PMV ≈ 0. This would not only reduce heating demand but should also enhance the system’s response to incoming solar gains by lowering PMV peaks. In Room L2—characterized by high stability and only brief overheating episodes—such an adjustment would likely allow PMV to be consistently maintained within the optimal range (−0.5 to 0.5), corresponding to comfort class II/I [23].

This study considered a horizontal slat position. However, dynamic automated control of slat tilt angle according to sun position and irradiance could further improve indoor conditions [44,45,58]. Partially closing the blinds during occupancy could limit PMV increases, enhance comfort, and reduce glare risk during low winter sun conditions [54]. On non-working days, fully opening the blinds could support passive heating by maximizing solar gains and reducing heating energy demand. Such an integrated approach to dynamically controlling the building envelope, lighting, and HVAC systems represents a key pathway toward achieving the highest levels of both energy efficiency and occupant comfort, as it fully leverages solar gains when beneficial and actively prevents overheating when adverse.

4.4. Summary, Insights and Directions for Future Work

Overall, the findings of this study provide new evidence on how solar exposure and shading strongly govern thermal comfort dynamics in surface-heated nZEB interiors. Outside solar exposure periods, occupants experienced comfort to slight thermal stress; however, during high-irradiance periods, in the room without blinds, the PMV index exceeded 2.0, indicating strong heat stress. By contrast, the presence of Venetian blinds substantially improved and stabilized the indoor microclimate, confirming the decisive role of basic solar protection in maintaining comfort in highly glazed spaces. Importantly, no significant differences in overall thermal comfort were observed between underfloor and wall heating according to whole-body PMV indices, suggesting that under transient solar loads, the presence or absence of shading exerts a stronger influence on perceived comfort than heating technology itself.

The results align with earlier research emphasizing the importance of both surface heating and shading strategies in controlling indoor thermal environments. Previous studies have demonstrated that radiant floor systems combined with heat pumps deliver stable thermal conditions and energy savings in residential and office buildings [12,13,14]. Our observations are consistent with these conclusions, extending them to wall-mounted systems and further indicating that solar gains remain a decisive factor for thermal comfort variation even under late-winter conditions, particularly in highly glazed rooms of modern nZEB buildings. This supports the premise reported by Mazzetto [46] and Kuhn [44], who emphasized the necessity of integrating shading into HVAC strategies.

By providing in situ experimental evidence from an operational public nZEB building, this study advances the understanding of the interaction between radiant heating systems, transient solar gains, and fixed external shading in shaping indoor environmental conditions. The results indicate that even non-adjustable shading elements can meaningfully influence indoor thermal conditions and should therefore be considered as an integral part of the design process in high-performance buildings. The findings offer practical insights for optimizing HVAC operation and support the development of simplified yet more predictive control approaches. Furthermore, they suggest potential benefits of adaptive and demand-responsive control approaches, in line with the growing research trend toward intelligent HVAC management [59,60]. Nevertheless, several aspects require further investigation.

A key limitation of this study is the analysis of only one room typology. Furthermore, microclimate conditions were evaluated at three heights but only in the central zone of the room, offering a limited perspective on conditions in peripheral areas where seated occupants may be located. Despite these limitations, the consistency between our results and findings from other published studies reinforces the conclusions regarding comfort conditions in the presence of external shading across different types of surface heating during periods of strong late-winter solar exposure.

Thermal comfort in this study was assessed using the PMV index, in line with current standards. However, future research should examine how the choice of comfort model influences indoor environmental evaluation in such spaces. In naturally ventilated buildings, adaptive comfort models are recommended, as occupants tend to tolerate or actively adapt to less favorable conditions [61,62]. In low-energy buildings, mechanical ventilation is typically used, inherently limiting the applicability of adaptive concepts. As a result, translating scientific insights into design and operational practice remains challenging [63]. Nonetheless, adaptive comfort ranges are increasingly used in buildings with hybrid ventilation, and many mechanically ventilated facilities also include operable windows. Therefore, future analyses should consider both Fanger’s PMV/PPD and adaptive models (e.g., according to ASHRAE criteria [33] or EN 16798-1 [23]). Such an approach may provide deeper insight into thermal comfort perception under real operating conditions and help bridge the gap between scientific guidelines and practical building design and operation.

Further work should also investigate the spatial distribution of indoor microclimate, with particular attention to areas near glazing or heated wall surfaces. Combining multi-level comfort measurements with CFD-based airflow modeling could clarify how local air movements enhance or attenuate vertical stratification. Another promising direction includes analyzing the complementary use of floor and wall heating to create more uniform thermal fields.

Broadening the scope to include different room orientations and glazing characteristics—such as size, glazing type or selective coatings—would deepen the understanding of thermal comfort dynamics in buildings exposed to varying solar conditions. Another relevant direction involves studying nZEB buildings with diverse orientations in the context of projected climate change.

Energy performance and reducing environmental impact are equally important criteria in low-energy building design. In this context, future studies should complement comfort analyses with assessments of heating energy demand, including how shading, glazing and surface heating configurations influence overall HVAC loads. Attention should also be given to the energy supply side, particularly the operational flexibility of integrated heat pump and building thermal energy storage systems. Advanced intelligent control strategies that integrate surface heating, movable blinds (where applicable), occupancy scheduling, occupancy detection, HVAC, lighting, and user feedback offer significant potential for optimizing thermal stability, reducing discomfort peaks and improving both visual comfort and energy performance. Modern building automation systems make it possible to control thermal and energy conditions dynamically, considering both indoor and outdoor variability. Recent developments in data-driven and adaptive approaches—such as reinforcement learning, fuzzy logic and artificial neural networks—show considerable promise as alternatives to rule-based control and Model Predictive Control (MPC). Integrating such advanced decision-making mechanisms into real-world building automation may provide more flexible, efficient and user-oriented management of surface heating systems [59,60,64].

The insights obtained in this study may support the design and operation of buildings with extensive glazing, including modern offices, educational facilities and residential structures. Validating the findings across different building types, climates and usage scenarios (e.g., private vs. open-plan offices, classrooms or shared spaces) would enhance their general applicability and facilitate engineering implementation. In effect, this line of research may help improve indoor thermal comfort while simultaneously advancing the energy efficiency objectives of nZEB buildings.

5. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence on how low-temperature radiant heating systems and solar control strategies jointly shape thermal comfort conditions in highly glazed nZEB interiors. Both analyzed heating configurations—underfloor and wall-mounted—ensured indoor conditions corresponding to comfort or slight thermal stress under steady operating conditions. However, during periods of strong solar exposure, the room without shading experienced pronounced thermal instability, with PMV values exceeding 2.0, indicating substantial heat stress.

By contrast, the use of external Venetian blinds effectively stabilized the indoor microclimate, reducing PMV peaks by an average of 50.2% and lowering the number of discomfort hours by 94.9%. These results confirm that solar protection plays a decisive role in maintaining comfort in highly glazed spaces, regardless of the specific surface-heating technology applied. The absence of notable whole-body PMV differences between floor and wall heating suggests that, under transient solar loads, shading conditions exert a stronger influence on perceived comfort than the heating system type itself.

The findings highlight the importance of integrating solar gain management with the design and control of radiant heating systems in nZEB buildings. They offer practical guidance for improving HVAC operation, emphasizing the need for shading as a core component of comfort-oriented design. These insights may support engineers and designers in optimizing thermal performance while upholding the energy-efficiency objectives of modern nZEB buildings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.-C., M.D., A.B.-C. and A.R.; methodology, M.F.-C., M.D., A.B.-C. and A.R.; software, M.D. and A.R.; validation, M.F.-C., E.R.-Z., M.D., A.B.-C. and A.D.; formal analysis, M.F.-C., M.D. and A.B.-C.; investigation, M.F.-C., M.D. and A.B.-C.; resources, M.F.-C., A.B.-C. and M.D.; data curation, M.D. and A.B.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.-C., E.R.-Z., M.D., A.B.-C., A.R. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, M.F.-C., M.D. and A.B.-C.; visualization, M.D. and A.B.-C.; supervision, M.F.-C. and E.R.-Z.; project administration, M.D. and A.B.-C.; funding acquisition M.F.-C. and E.R.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are part of a broader ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| nZEB | nearly zero-energy building; standard applicable in the European Union |

| HVAC | heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system |

| PMV | predicted mean vote [-] |

| PPD | predicted percentage dissatisfied [%] |

| IEQ | indoor environmental quality |

| PECS | personalized environmental control systems |

| ASHP | air-source heat pump |

| COP | coefficient of performance [-] |

| MCBE | Małopolska Center of Energy Efficient Building |

| BMS | building management system |

| BIPV | building-integrated photovoltaic |

| BIST | building-integrated solar thermal system |

| L1 | experimental room without a solar shading system |

| L2 | experimental room equipped with an external Venetian blind system |

| Ta | air temperature [°C] |

| RH | relative humidity [%] |

| Va | air velocity [m/s] |

| min | minimum |

| max | maximum |

| RBC | rule-based control |

| MPC | model predictive control |

References

- European Climate Foundation. Available online: https://europeanclimate.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Directive 2002/91–EN–EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32002L0091 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Directive-2010/31-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/31/oj (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Directive 2018/844–EN–EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/844/oj (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Directive 2023/1791-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32023L1791 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Regulation 2018/1999-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1999 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Act of 17 September 2021 Amending the Construction Law and the Act on Spatial Planning and Development, in Polish. 2021; Issued by: Chancellery of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210001986 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Regulation of the Minister of Development and Technology of 31 January 2022 Amending the Regulation on Technical Conditions to be Met by Buildings and Their Location, in Polish. 2022. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220000248 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Barnaś, K.; Jeleński, T.; Nowak-Ocłoń, M.; Racoń-Leja, K.; Radziszewska-Zielina, E.; Szewczyk, B.; Śladowski, G.; Toś, C.; Varbanov, P.S. Algorithm for the Comprehensive Thermal Retrofit of Housing Stock Aided by Renewable Energy Supply: A Sustainable Case for Krakow. Energy 2023, 263, 125774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BUILD UP-The European Portal for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy in Buildings. Available online: https://build-up.ec.europa.eu/en/home (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- EHPA-European Heat Pump Association. Available online: https://Ehpa.Org/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Akmal, M.; Fox, B. Modelling and Simulation of Underfloor Heating System Supplied from Heat Pump. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 28.1–28.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.J.; Jeong, J.W. Energy Saving Potential of Radiant Floor Heating Assisted by an Air Source Heat Pump in Residential Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Huang, H. Research on Optimization of the Heating System in Buildings in Cold Regions by Energy-Saving Control. Arch. Thermodyn. 2024, 45, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romańska-Zapała, A. Experiment Results of Building Integrated Control System—Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2016 Second International Conference on Event-Based Control, Communication, and Signal Processing (EBCCSP), Krakow, Poland, 13–15 June 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y. Experimental Study on Phase Change Heat Storage Floor Coupled with Air Source Heat Pump Heating System in a Classroom. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Li, X.; Chang, C.; Zhou, W.; Wang, G.; Tong, C. Heating Performance of PCM Radiant Floor Coupled with Horizontal Ground Source Heat Pump for Single-Family House in Cold Zones. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorca, A.; Sarbu, I. Thermal Protection Impact Assessment of a Residential House on the Energy Efficiency of the Air-Source Heat Pump Radiant Floor Heating System. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 67, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djongyang, N.; Tchinda, R.; Njomo, D. Thermal Comfort: A Review Paper. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2626–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.F.; Vásquez, N.G.; Lamberts, R. A Review of Human Thermal Comfort in the Built Environment. Energy Build. 2015, 105, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppe, P. Different Aspects of Assessing Indoor and Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1972; ISBN 9780070199156. [Google Scholar]

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings-Ventilation for Buildings-Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics-Module M1-6. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Piasecki, M.; Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Furtak, M.; Biskupski, J. Experimental Confirmation of the Reliability of Fanger’s Thermal Comfort Model—Case Study of a Near-Zero Energy Building (NZEB) Office Building. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 7730:2025; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Mahdavinejad, M.; Bazazzadeh, H.; Mehrvarz, F.; Berardi, U.; Nasr, T.; Pourbagher, S.; Hoseinzadeh, S. The Impact of Facade Geometry on Visual Comfort and Energy Consumption in an Office Building in Different Climates. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alders, E.E. Adaptive Heating, Ventilation and Solar Shading for Dwellings. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2017, 60, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Chen, W.; Wu, H.; Zheng, Z. Experimental Investigation of Indoor Thermal Comfort under Different Heating Conditions in Winter. Buildings 2022, 12, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakkama, H.J.; Khaleel, A.J.; Ahmed, A.Q.; Al-Shohani, W.A.M.; Obaida, H.M.B. Effect of Local Floor Heating System on Occupants’ Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Fluids 2023, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Ge, B. Experimental Study on Local Floor Heating Mats to Improve Thermal Comfort of Workers in Cold Environments. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakubo, S.; Arata, S.; Suganuma, C.; Takuwa, Y.; Ikaga, T. Effects of Residential Floor-Level Thermal Environment on Task Performance via Psychophysiological Responses Using Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling. Build. Environ. 2025, 283, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Daneshazarian, R.; Mwesigye, A.; Leong, W.H.; Dworkin, S.B. A Novel Radiant Floor System: Detailed Characterization and Comparison with Traditional Radiant Systems. Int. J. Green. Energy 2020, 17, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE 55-2017; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc. [ASHRAE]: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2017.

- Zheng, J.; Yu, T.; Lei, B.; Luo, X. Evaluation of the Thermal Performance of Radiant Floor Heating System with the Influence of Unevenly Distributed Solar Radiation Based on the Theory of Discretization. Build. Simul. 2022, 16, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero-Salinas, J.; López-Hernández, D.; González-Martínez, P.; Arriazu-Ramos, A.; Monge-Barrio, A.; Sánchez-Ostiz, A. Exploring Indoor Thermal Comfort and Its Causes and Consequences amid Heatwaves in a Southern European City—An Unsupervised Learning Approach. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheed, M.; Mourshed, M. Domestic Overheating Risks and Mitigation Strategies: The State-of-the-Art and Directions for Future Research. Indoor Built Environ. 2023, 32, 1057–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.P.; Tetzlaff, E.J.; Journeay, W.S.; Henderson, S.B.; O’Connor, F.K. Indoor Overheating: A Review of Vulnerabilities, Causes, and Strategies to Prevent Adverse Human Health Outcomes during Extreme Heat Events. Temperature 2024, 11, 203–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiil, M.; Simson, R.; Thalfeldt, M.; Kurnitski, J. Overheating and Air Velocities in Modern Office Buildings During Heating Season. Indoor Air 2024, 2024, 9992937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosori, V.; Tablada, A.; Trivic, Z.; Horvat, M.; Vukmirovi, M.; Domingo-Irigoyen, S.; Todorovi, M.; Kaempf, J.H.; Goli, K.; Peric, A.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Overheating Risk for Typical Dwellings and Passivhaus in the UK. Energies 2022, 15, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, K.J.; Porritt, S.M. Overheating in Buildings: Lessons from Research. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Radoń, M. New Generation Window Glazing and Other Solution in Low Energy Buildings. In Proceedings of the CESB 2013 PRAGUE-Central Europe Towards Sustainable Building 2013: Sustainable Building and Refurbishment for Next Generations, Prague, Czech Republic, 26–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Nowak, K.; Furtak, M. Analysis of the Effect of Using External Venetian Blinds on the Thermal Comfort of Users of Highly Glazed Office Rooms in a Transition Season of Temperate Climate—Case Study. Energies 2019, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. Dynamic Shading and Glazing Technologies: Improve Energy, Visual, and Thermal Performance. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.E. State of the Art of Advanced Solar Control Devices for Buildings. Sol. Energy 2017, 154, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewardane, S.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Santamouris, M. Dynamic Solar Shadings: Redefining the Building Envelope. Sol. Compass 2025, 16, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Dynamic Integration of Shading and Ventilation: Novel Quantitative Insights into Building Performance Optimization. Buildings 2025, 15, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, E.; Manav, B. Integrated Lighting and Solar Shading Strategies for Energy Efficiency, Daylighting and User Comfort in a Library Design Proposal. Buildings 2025, 15, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perino, M.; Bilardo, M.; Fabrizio, E. A Framework for Assessing the Energy Performance of Personalized Environmental Control Systems (PECS) for Heating, Cooling and Ventilation. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 111925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, M.; Szydłowski, R.; Wójcik, K.; Spaczyński, M. As-Built Documentation, Construction of the Małopolska Laboratory of Energy Efficient Building at Warszawska 24 in Cracow, Poland; Internal technical documentation, Cracow University of Technology: Cracow, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 7726:2002; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Instruments for Measuring Physical Quantities (ISO 7726:1998). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Ekohigiena Aparatura Ryszard Putyra. Operating Instructions Microclimate Meter EHA MM101; Ekohigiena Aparatura Ryszard Putyra: Środa Śląska, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norouziasas, A.; Attia, S.; Hamdy, M. Impact of Space Utilization and Work Time Flexibility on Energy Performance of Office Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Bertrand, S.; Cuchet, M.; Yang, S.; Tabadkani, A. Comparison of Thermal Energy Saving Potential and Overheating Risk of Four Adaptive Façade Technologies in Office Buildings. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, K. Indoor Light Environment Factors That Affect the Psychological Satisfaction of Occupants in Office Facilities. Buildings 2024, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbin, J. Środowiskowe Czynniki Fizyczne Wpływające Na Organizm Człowieka [Environmental Physical Factors Affecting the Human Body, in Polish]. In Wybrane Problemy Higieny i Ekologii Człowieka [Selected Issues in Human Hygiene and Ecology, in Polish]; Kolarczyk, E., Ed.; Jagiellonian University Publishing: Kraków, Poland, 2008; pp. 29–100. ISBN 978-83-233-2467-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ekici, C. A Review of Thermal Comfort and Method of Using Fanger’s PMV Equation. In Proceedings of the 5TH International Symposium on Measurement, Analysis and Modeling of Human Functions 2013, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27–29 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fanger, P.O.; Christensen, N.K. Perception of Draught in Ventilated Spaces. Ergonomics 1986, 29, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, C.; Zhong, L. Optimizing Automated Shading Systems for Enhanced Energy Performance in Cold Climate Zones: Strategies, Savings, and Comfort. Energy Build. 2023, 300, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, P.; Michailidis, I.; Vamvakas, D.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Model-Free HVAC Control in Buildings: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, M. Towards Characterization of Indoor Environment in Smart Buildings: Modelling PMV Index Using Neural Network with One Hidden Layer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dear, R.J.; Brager, G.S. Towards an Adaptive Model of Thermal Comfort and Preference. ASHRAE Trans. 1998, 104, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, J.F.; Humphreys, M.A. Adaptive Thermal Comfort and Sustainable Thermal Standards for Buildings. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, R.T.; Teli, D.; Schweiker, M.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, M.C.J.; Mora, R.; Rawal, R.; Wang, Z.; Al-Atrash, F. A Framework for Adopting Adaptive Thermal Comfort Principles in Design and Operation of Buildings. Energy Build. 2019, 205, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, M.; Romanska-Zapala, A.; Bomberg, M. A Neural Network for Monitoring and Characterization of Buildings with Environmental Quality Management, Part 1: Verification under Steady State Conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.