Modeling Merit-Order Shifts in District Heating Networks: A Life Cycle Assessment Method for High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It adapts a consequential perspective, in contrast to predominantly attributional approaches in the existing literature, enabling decision-making and change-oriented assessment.

- It applies system expansion and a heating-system-wide functional unit to capture changes in heat supply composition across existing technologies, enabling causal net-impact assessment and improving consistent cost and emission accounting.

- It integrates a dynamic DHN-HT-ATES model to represent time-dependent technical performance relevant for LCA and economic assessment (notably schedule-dependent losses and capacity constraints).

- It adapts the DH-MO of Moser et al. [4] by distinguishing must-run and flexible capacities to identify the time resolved marginally displaced heat mix and associated costs and emission variations; the DH-MO is implemented within a merit-order dispatch model formulated as a linear program (LP).

- It quantifies environmental impacts using a hybrid approach that combines short-term operational impacts with long-term economy-wide effects, specifying the marginal technologies involved and the marginal data used [35].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Expansion and Functional Unit

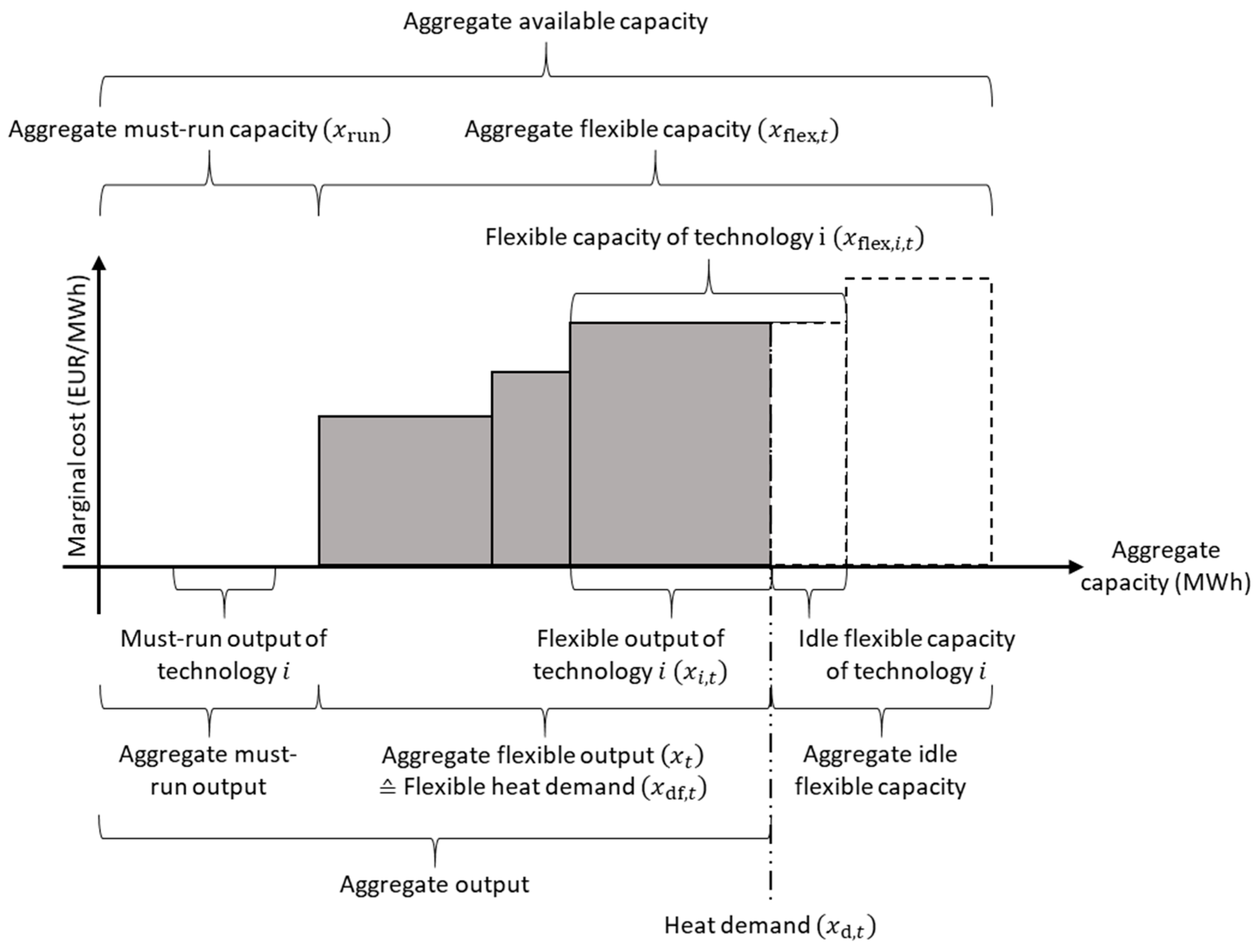

2.2. Adaptation of the District Heating Merit Order

- Heat demand is assumed not to change when introducing the HT-ATES; network inefficiencies (e.g., pipeline losses) are included in the available capacity of the HT-ATES.

- Marginal effects equal variable effects, assuming linear output relationships across a technology’s flexible capacity.

- Excess heat output may occur if demand is lower than must-run capacities. In such cases, surplus heat generation is assumed to be technically manageable (e.g., via dissipation).

- Must-run capacities do not change due to the HT-ATES integration.

2.3. Specifications of District Heating Technologies

- (MWh) is the available capacity of technology at time ,

- (MW) is the available heating power of technology over duration of time interval ,

- (h) is the duration of the time interval considered.

2.4. Dynamic DHN-HT-ATES Model

2.4.1. System Topology and Components

- Producer: Represented as an ideal heater with unlimited capacity, coupled with a circulation pump that governs mass flow. This component imposes the network’s supply temperature based on historical measurement data.

- Consumer: Modeled as an ideal cooler with unlimited cooling capacity. This component determines the heat load by cooling the working fluid down to the network’s historical return temperature.

- HT-ATES Integration: The HT-ATES and its associated heat pump and heat exchangers are hydraulically connected between the producer and consumer. This configuration allows the system to extract heat from the supply line during charging and inject heat back into the supply line during discharging.

2.4.2. Hydraulics and Network Assumptions

2.4.3. HT-ATES and Heat Pump Specification

- Well Configuration: Two-well system (one warm and one cold well).

- Aquifer Properties: Aquifer thickness, porosity, hydraulic conductivity, volumetric heat capacity, and thermal conductivity. Quantitative data are commonly derived from the literature for matching geological conditions (i.e., [58]) or field studies such as exploratory drilling.

- Heat Pump: To lift the temperature from the aquifer to the required network supply levels, a heat pump is modeled using a simplified Carnot efficiency approach with a constant efficiency factor of 0.5 [59].

2.4.4. Control Logic and Dispatch

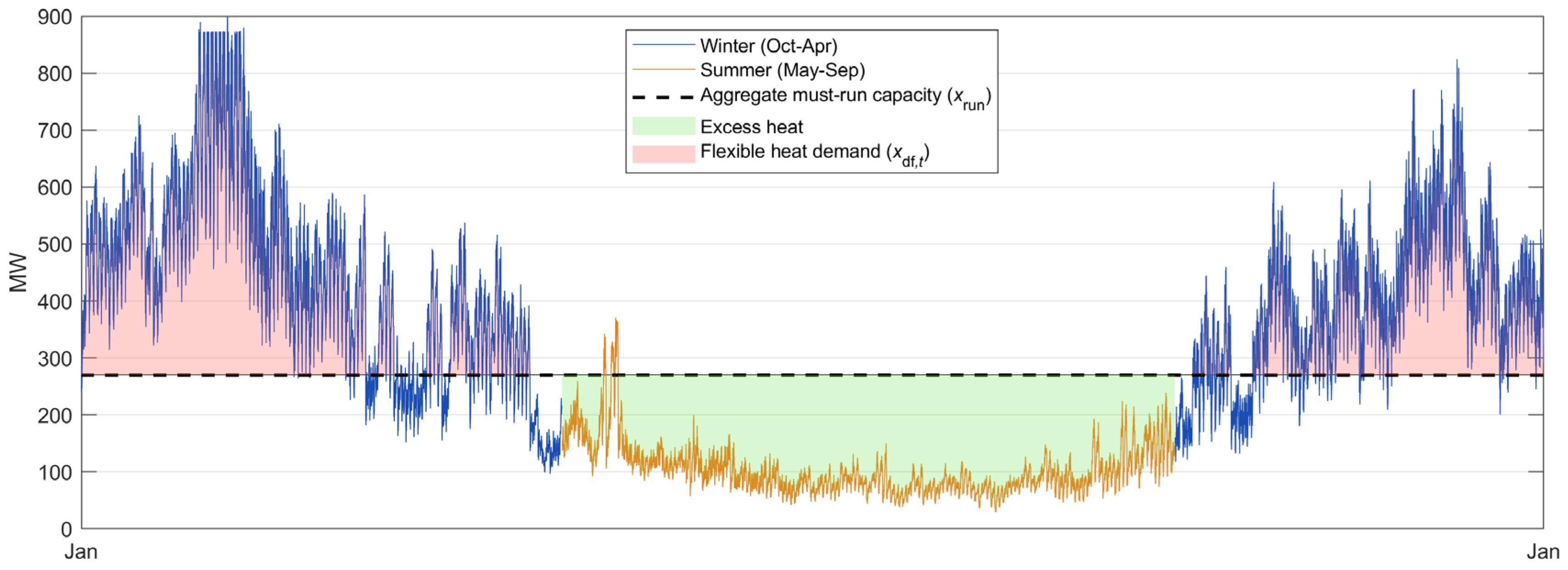

- Heat demand: Heat-demand data can be obtained in different ways. For retrospective assessments (i.e., “what if an HT-ATES had been integrated?”), historical demand data are suitable. Prospective assessments (i.e., “what if integration occurs in the future?”) require scenario-based modeling. An hourly resolution is recommended, used in this study, to capture DHN operational constraints and flexibility requirements.

- Charging: Charging is enabled during the storage season (1 May to 30 September). The control logic starts the injection pump when aggregate must-run generation exceeds network demand by at least 17 MW and the charging mass flow is capped at 200 m3/h. This ensures that costs and environmental impacts occurring due to charging are limited to the electricity consumption of the submersible injection pumps and not induced by additional heat generation. Charging operation is not affected by the merit-order-based discharging strategy.

- Discharging: Discharging is triggered after the charging season and when the HT-ATES temperature exceeds the median DHN return temperature. In the run that determines the maximum technically available discharge capacity, discharging depends only on the thermal states of the storage and the network. Economic constraints applied in the LP model then shift storage dispatch through merit-order considerations (Section 2.5).

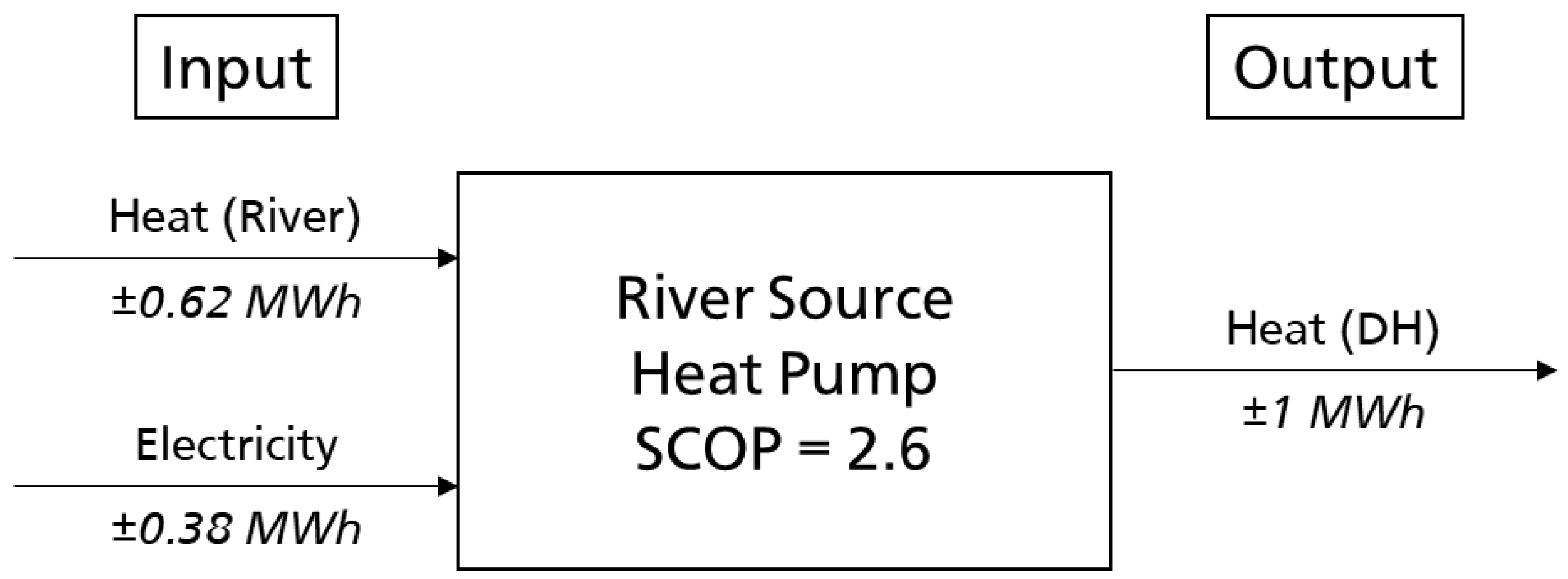

2.4.5. Seasonal Coefficient of Performance

- is the heat delivered to the DHN by the heat pump at time ,

- is electrical input of the heat pump compressor at time

- is the index of assessed time intervals, with being the total number of intervals.

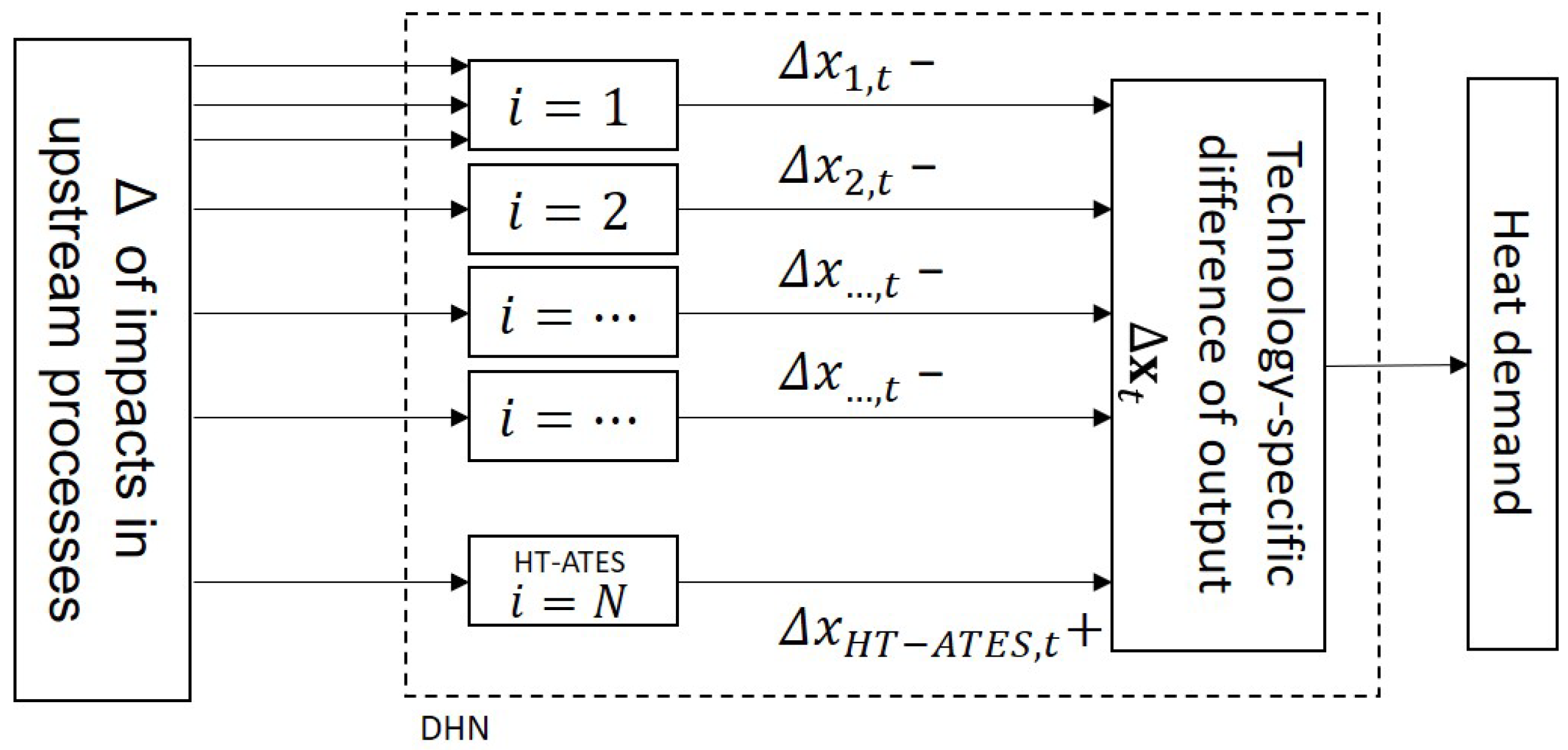

2.5. Computation of Difference in Heat Supply Composition

- Demand satisfaction: aggregate flexible output must equal flexible demand :

- Definition of flexible demand:

- Technology limits:

2.6. Life Cycle Inventory and Impact Assessment

2.6.1. Economic Impact Modeling

2.6.2. Environmental Impact Modeling

2.6.3. Data Quality Requirements and Evaluation

2.7. Case Study Description

3. Results

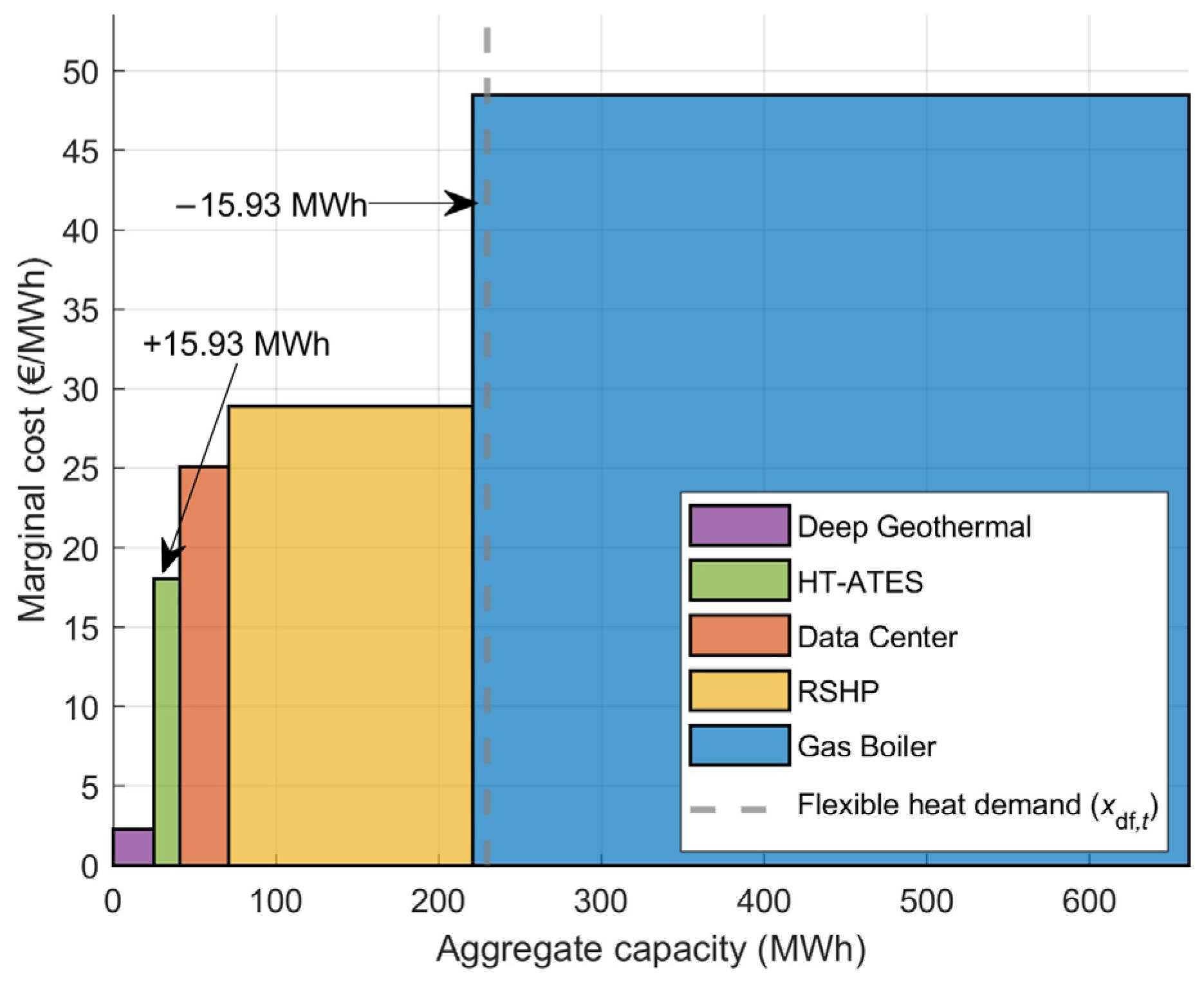

3.1. Case Study: Specifications of District Heating Technologies

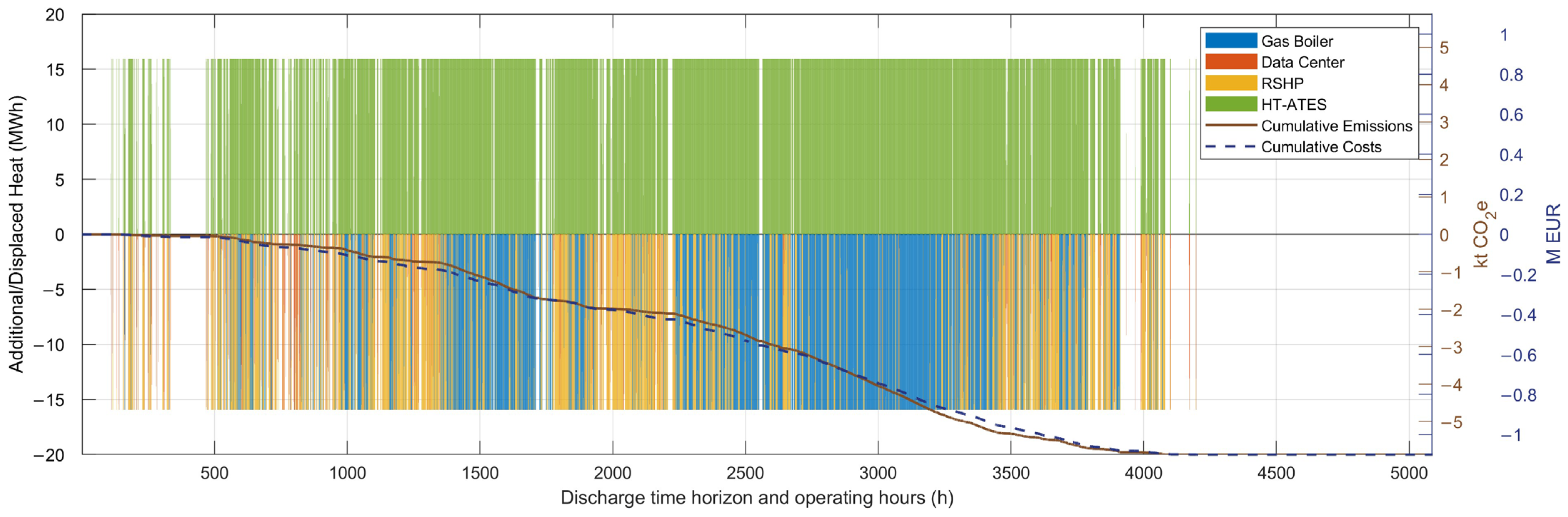

3.2. Case Study: Application of Dynamic DHN-HT-ATES Model

3.3. Case Study: Computation of Difference in Heat Supply Composition

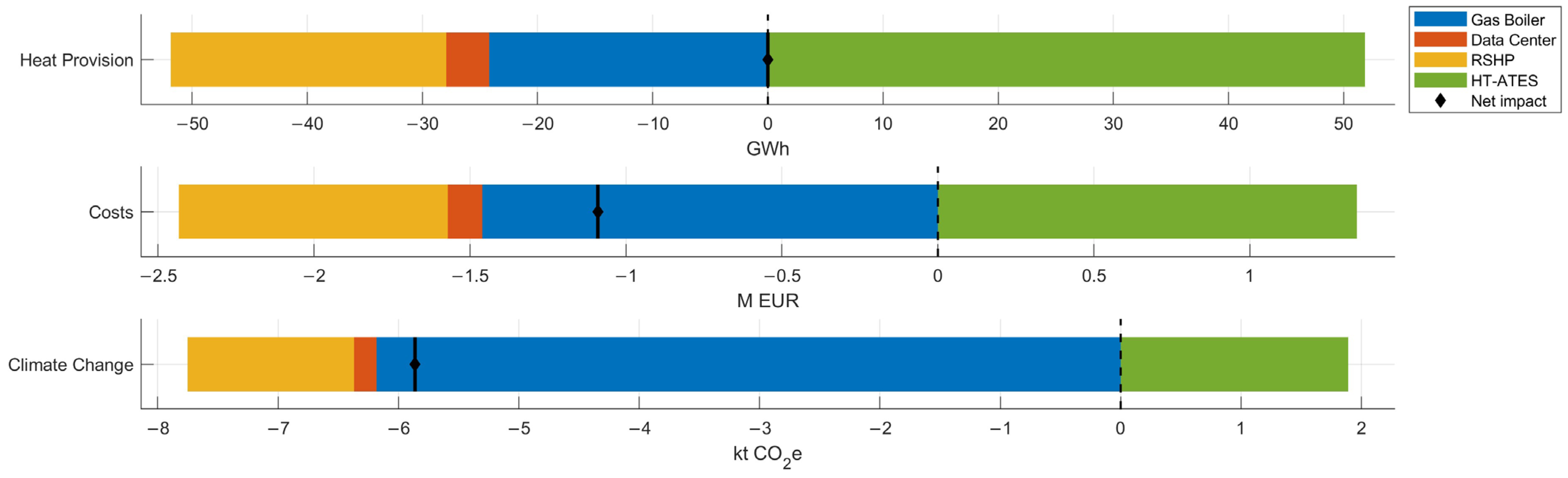

3.4. Case Study: Life Cycle Inventory and Impact Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Alternative Operation Schedules

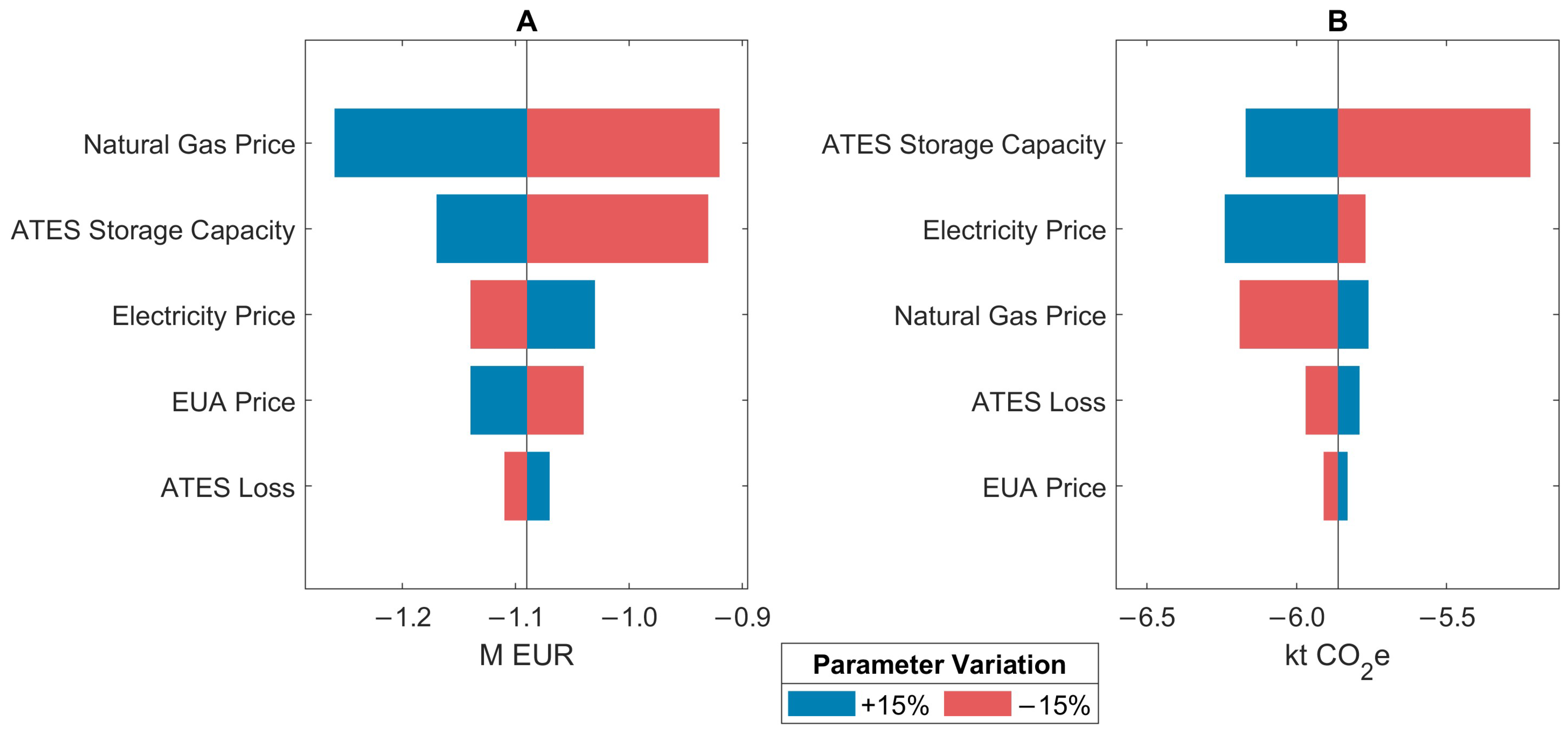

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4.3. Limitations

4.3.1. Conceptual Assumptions

4.3.2. Computational Simplifications

4.3.3. Applicability Boundaries and Transferability to Other DHNs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATES | Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

| DE | Deutschland (Germany) in ecoinvent dataset |

| DH-MO | District Heating Merit Order |

| DHN | District Heating Network |

| EUA | European Allowance |

| GWP100 | Global Warming Potential 100 Years |

| HT-ATES | High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage |

| IAM | Integrated Assessment Model |

| IN | Independent Discharge Schedule |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| LP | Linear Program |

| LT-ATES | Low-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage |

| MO | Merit-Order Operation Schedule |

| NG | Natural Gas Operation Schedule |

| NPi | National Policies implemented |

| RSHP | River Source Heat Pump |

| SCOP | Seasonal Coefficient of Performance |

| SSP | Shared Socioeconomic Pathway |

| Nomenclature | |

| Indices/Subscripts | |

| index of heating technology | |

| index of time interval | |

| index of year | |

| total number of heating technologies | |

| total number of assessed time intervals | |

| ~ | accent for variables in integration scenario |

| Scalars | |

| marginal cost of technology i at time t [EUR/MWh] | |

| heat delivered to the DHN by the heat pump at time t | |

| electrical input submersible pump | |

| [MWh] | |

| heat demand at time t [MWh] | |

| flexible heat demand at time t [MWh] | |

| aggregate flexible capacity at time t [MWh] | |

| flexible capacity of technology i at time t [MWh] | |

| aggregate must-run capacity [MWh] | |

| must-run capacity of technology i [MWh] | |

| aggregate flexible output at time t [MWh] | |

| flexible output of technology i at time t [MWh] | |

| available heating power of technology i at time t [MW] | |

| aggregate marginal cost at time t [EUR] | |

| annual aggregate marginal cost [EUR] | |

| marginal change of electricity [MWh] | |

| marginal change of heat from river [MWh] | |

| marginal change of a heat demand in district heating network [MWh] | |

| duration of time interval considered in the analysis [h] | |

| flexible output difference of technology i at time t [MWh] | |

| aggregate flexible output difference of technology i in year y [MWh] | |

| Vectors | |

References

- Autelitano, K.; Famiglietti, J.; Aprile, M.; Motta, M. Towards Life Cycle Assessment for the Environmental Evaluation of District Heating and Cooling: A Critical Review. Standards 2024, 4, 102–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, P.W.; Wang, H.; Tokbolat, S.; Boukhanouf, R.; Calautit, J.; Darkwa, J. Application of life cycle assessment for enhancing sustainability of district heating: A multi-level approach. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5077–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmle, R.; Arab, A.; Bauer, S.; Beyer, C.; Blöcher, G.; Bossennec, C.; Dörnbrack, M.; Hahn, F.; Jaeger, P.; Kranz, S.; et al. Current research on aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) in Germany. Grund. Z. Fachsekt. Hydrogeol. 2025, 30, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Puschnigg, S.; Rodin, V. Designing the Heat Merit Order to determine the value of industrial waste heat for district heating systems. Energy 2020, 200, 117579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuchaus, P.; Godschalk, B.; Stober, I.; Blum, P. Worldwide application of aquifer thermal energy storage—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, N.; Pellegrini, M.; Bloemendal, M.; Spaak, G.; Gallego, A.A.; Comins, J.R.; Grotenhuis, T.; Picone, S.; Murrell, A.; Steeman, H.; et al. Increasing market opportunities for renewable energy technologies with innovations in aquifer thermal energy storage. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidis, A.; Mindel, J.E.; Filho, F.D.O.; Guglielmetti, L. Techno-economic assessment and operational CO2 emissions of High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (HT-ATES) using demand-driven and subsurface-constrained dimensioning. Energy 2022, 249, 123682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.S.; Gil, A.G.; Vieira, A.; Michopoulos, A.K.; Boon, D.P.; Loveridge, F.; Cecinato, F.; Götzl, G.; Epting, J.; Zosseder, K.; et al. Shallow geothermal energy systems for district heating and cooling networks: Review and technological progression through case studies. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, O.; Alanne, K.; Virtanen, M.; Kosonen, R. Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES) for District Heating and Cooling: A Novel Modeling Approach Applied in a Case Study of a Finnish Urban District. Energies 2020, 13, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marojević, K.; Kurevija, T.; Macenić, M. Challenges and Opportunities for Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES) in EU Energy Transition Efforts—An Overview. Energies 2025, 18, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmle, R.; Hanna, R.; Menberg, K.; Østergaard, P.A.; Jackson, M.; Staffell, I.; Blum, P. Policies for aquifer thermal energy storage: International comparison, barriers and recommendations. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 1455–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghici, R.M.; Oude Essink, G.H.; Hartog, N.; Sommer, W. Integrated assessment of variable density–viscosity groundwater flow for a high temperature mono-well aquifer thermal energy storage (HT-ATES) system in a geothermal reservoir. Geothermics 2015, 55, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotta, G.; Marrasso, E.; Martone, C.; Luciano, N.; Squarzoni, G.; Roselli, C.; Sasso, M. Aquifer thermal energy storage for decarbonising heating and cooling energy supply in southern Europe: A dynamic environmental impact assessment. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 126105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agate, G.; Colucci, F.; Luciano, N.; Marrasso, E.; Martone, C.; Pallotta, G.; Roselli, C.; Sasso, M.; Squarzoni, G. Multi-software based dynamic modelling of a water-to-water heat pump interacting with an aquifer thermal energy storage system. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüchinger, R.; Hendry, R.; Walter, H.; Worlitschek, J.; Schuetz, P. Cost Analysis for Large Thermal Energy Storage Systems. ASME J. Eng. Sustain. Build. Cities 2025, 6, 021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinaud, J.; Loubet, P.; Gombert-Courvoisier, S.; Pryet, A.; Dupuy, A.; Larroque, F. Life Cycle Assessment of an Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage System: Influence of design parameters and comparison with conventional systems. Geothermics 2024, 120, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, M.; Grotenhuis, T.; Qiu, R. Comparative Life-Cycle Assessment of Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integrated with in Situ Bioremediation of Chlorinated Volatile Organic Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3039–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulopoulos, A. Life Cycle Assessment of an Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage system: Exploring the Environmental Performance of Shallow Subsurface Space Development. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasetta, C.; van Ree, C.C.D.F.; Griffioen, J. Life Cycle Analysis of Underground Thermal Energy Storage. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory—Volume 5: Urban Geology, Sustainable Planning and Landscape Exploitation; Lollino, G., Manconi, A., Guzzetti, F., Culshaw, M., Bobrowsky, P., Luino, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmle, R.; Blum, P.; Schüppler, S.; Fleuchaus, P.; Limoges, M.; Bayer, P.; Menberg, K. Environmental impacts of aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetta, C. Life Cycle Assessement of Underground Thermal Energy Storage Systems: Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage versus Borehole Thermal Energy Storage. Master’s Thesis, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venice, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, J. Environmental Footprint of High Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, J.; Bott, C.; Menberg, K.; Bayer, P. Comprehensive life cycle assessment of selected seasonal thermal energy storage systems. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholliers, N.; Ohagen, M.; Bossennec, C.; Sass, I.; Zeller, V.; Schebek, L. Identification of key factors for the sustainable integration of high-temperature aquifer thermal energy storage systems in district heating networks. Smart Energy 2024, 13, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drijver, B.; van Aarssen, M.; Zwart, B.D. High-temperature aquifer thermal energy storage (HT-ATES): Sustainable and multi-usable. In Proceedings of the Innostock 2012—The 12th International Conference on Energy Storage, Lleida, Catalonia, Spain, 16–18 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schüppler, S.; Fleuchaus, P.; Blum, P. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of an Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (ATES) in Germany. Geotherm Energy 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuchaus, P.; Schüppler, S.; Bloemendal, M.; Guglielmetti, L.; Opel, O.; Blum, P. Risk analysis of High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage (HT-ATES). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, S.; Werner, S. District Heating and Cooling; Studentlitteratur AB: Lund, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ohagen, M.; Koch, M.; Scholliers, N.; Pham, H.T.; Holler, J.K.; Sass, I. Managing High Groundwater Velocities in Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Systems: A Three-Well Conceptual Model. Energies 2025, 18, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, T. Attributional and Consequential Life Cycle Assessment. In Sustainability Assessment at the 21st Century; José Bastante-Ceca, M., Luis Fuentes-Bargues, J., Hufnagel, L., Mihai, F.-C., Iatu, C., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent developments in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoudt, D.; Desmedt, J.; van Bael, J.; Robeyn, N.; Hoes, H. An aquifer thermal storage system in a Belgian hospital: Long-term experimental evaluation of energy and cost savings. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 3657–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaebi, H.; Bahadori, M.N.; Saidi, M.H. Economic and Environmental Evaluations of Different Operation Alternatives of an Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage in Tehran, Iran. Sci. Iran. 2017, 24, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevin, R.J.; Delucchi, M.A.; Creutzig, F. Using Attributional Life Cycle Assessment to Estimate Climate-Change Mitigation Benefits Misleads Policy Makers. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijungs, R. Marginal and average considerations in LCA and their role for defining emission factors and characterization factors. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Li, K.; Gao, H.; Tatomir, A.; Sauter, M.; Ganzer, L. Techno-economic assessment of high-temperature aquifer thermal energy storage system, insights from a study case in Burgwedel, Germany. Appl. Energy 2024, 372, 123783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmelts, J.; Tensen, S.C.; Infante Ferreira, C.A. Seasonal thermal energy storage for large scale district heating. In Proceedings of the 13th IEA Heat Pump Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 26–29 April 2021; Heat Pump Centre c/o RISE Research Institutes of Sweden: Borås, Sweden, 2021; pp. 1633–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Réveillère, A.; Hamm, V.; Lesueur, H.; Cordier, E.; Goblet, P. Geothermal contribution to the energy mix of a heating network when using Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage: Modeling and application to the Paris basin. Geothermics 2013, 47, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, O.; Strodel, N.; Werner, K.F.; Geffken, J.; Tribel, A.; Ruck, W. Climate-neutral and sustainable campus Leuphana University of Lueneburg. Energy 2017, 141, 2628–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidema, B.P.; Pizzol, M.; Schmidt, J.; Thoma, G. Attributional or consequential Life Cycle Assessment: A matter of social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidema, B.P.; Frees, N.; Nielsen, A.-M. Marginal production technologies for life cycle inventories. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 1999, 4, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, O.; Finnveden, G.; Ekvall, T.; Björklund, A. Life cycle assessment of fuels for district heating: A comparison of waste incineration, biomass- and natural gas combustion. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1346–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagica, A.; Cliftb, R. Allocation of environmental burdens in multiple-function systems. J. Clean. Prod. 1999, 7, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Werner, S.; Wiltshire, R.; Svendsen, S.; Thorsen, J.E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mathiesen, B.V. 4th Generation District Heating (4GDH). Energy 2014, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, D.; Götz, M.; Theofilidi, M.; Bruckner, T. Control power provision with power-to-heat plants in systems with high shares of renewable energy sources—An illustrative analysis for Germany based on the use of electric boilers in district heating grids. Energy 2015, 82, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, G.; Rantzer, J.; Ericsson, K.; Lauenburg, P. The potential of power-to-heat in Swedish district heating systems. Energy 2017, 137, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkova, A.; Reuter, S.; Puschnigg, S.; Kauko, H.; Schmidt, R.-R.; Leitner, B.; Moser, S. Cascade sub-low temperature district heating networks in existing district heating systems. Smart Energy 2022, 5, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicherer, N.; Lorenzen, P.; Schäfers, H. Design of a district heating roadmap for Hamburg. Smart Energy 2021, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, W.-P. Residual load, renewable surplus generation and storage requirements in Germany. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicherer, N.; Benalcazar, P.; Lorenzen, P.; Kozlenko, O.; Tomtulu, S.; Trosdorff, J. Heat4Future: A strategic planning tool for decarbonizing district heating systems. MethodsX 2025, 14, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MVV Energie AG. Flusswärmepumpe 1. 2025. Available online: https://www.mvv.de/ueber-uns/unternehmensgruppe/mvv-umwelt/aktuelle-projekte/flusswaermepumpen/flusswaermepumpe-1 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Modelica: Modelica Association c/o PELAB, IDA, Linköpings Universitet. 2025. Available online: http://modelica.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Brück, D.; Elmqvist, H.; Mattson, S.E.; Olsson, H. Dymola for Multi-Engineering Modeling and Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Modelica Conference, Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany, 18–19 March 2002; pp. 55-1–55-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter, M.; Zuo, W.; Nouidui, T.S.; Pang, X. Modelica Buildings library. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2014, 7, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIT-IES. DisHeatLib. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/AIT-IES/DisHeatLib (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Maccarini, A.; Wetter, M.; Varesano, D.; Bloemendal, M.; Afshari, A.; Zarrella, A. Low-order aquifer thermal energy storage model for geothermal system simulation. In Proceedings of the 15th International Modelica Conference 2023, Aachen, Germany, 9–11 October 2023; Linköping University Electronic Press: Linköping, Sweden, 2023; pp. 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemendal, M.; Olsthoorn, T. ATES systems in aquifers with high ambient groundwater flow velocity. Geothermics 2018, 75, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, H.; Mašatin, V.; Volkova, A.; Ommen, T.; Elmegaard, B.; Brix Markussen, W. Modelling framework for integration of large-scale heat pumps in district heating using low-temperature heat sources. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2019, 20, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G. Principles of Economics; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Wirsing, G.; Luz, A. Hydrogeologischer Bau und Aquifereigenschaften der Lockergesteine im Oberrheingraben (Baden-Württemberg); Regierungspräsidium Freiburg: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, P.H.; Rechberger, H. Waste to energy—Key element for sustainable waste management. Waste Manag. 2015, 37, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ember. European Wholesale Electricity Price Data: Germany, Hourly. 2025. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/data/european-wholesale-electricity-price-data/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Monthly Natural Gas Imports. 2025. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Economy/Foreign-Trade/Tables/natural-gas-monthly.html (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP). EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS): Factsheet; International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP): Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lamaison, N.; Collette, S.; Vallée, M.; Bavière, R. Storage influence in a combined biomass and power-to-heat district heating production plant. Energy 2019, 186, 115714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaucour, R.; Wissocq, T.; Lamaison, N. HeatPro Python Package: Generate Heat Demand Load Profile for District Heating. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/CEA-Liten/heatpro (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Grundfos Holding A/S. Submersible Groundwater Pumps: SP 215-2A—No. 18A356A2. 2024. Available online: https://product-selection.grundfos.com/products/sp-sp-g/sp/sp-215-2a-18A356A2 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Steubing, B.; de Koning, D.; Haas, A.; Mutel, C.L. The Activity Browser—An open source LCA software building on top of the brightway framework. Softw. Impacts 2020, 3, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Nicholls, Z.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Forster, P.; Meinshausen, M.; Palmer, M.; Watanabe, M. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity Supplementary Material. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi, R.; Terlouw, T.; Siala, K.; Dirnaichner, A.; Bauer, C.; Cox, B.; Mutel, C.; Daioglou, V.; Luderer, G. PRospective EnvironMental Impact asSEment (premise): A streamlined approach to producing databases for prospective life cycle assessment using integrated assessment models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumstark, L.; Bauer, N.; Benke, F.; Bertram, C.; Bi, S.; Gong, C.C.; Dietrich, J.P.; Dirnaichner, A.; Giannousakis, A.; Hilaire, J.; et al. REMIND2.1: Transformation and innovation dynamics of the energy-economic system within climate and sustainability limits. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 6571–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference Scenario | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waste incineration CHP | (1) | 125 | 125 | 0 |

| Gas boilers (aggregated) | (2) | 440 | 0 | 440 |

| Data center | (3) | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| RSHP (aggregated) | (4) | 150 | 0 | 150 |

| Biomass CHP | (5) | 45 | 45 | 0 |

| Deep geothermal plants | (6) | 125 | 100 | 25 |

| Total | 915 | 270 | 645 | |

| Integration Scenario | ||||

| HT-ATES | (7) | 15.93 * | 0 | 15.93 * |

| Gas Boiler (Natural Gas) | Data Center | RSHP | Deep Geothermal | HT-ATES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | ηng = 98% | COPDC = 3.0 | SCOPRiv = 2.6 | COPGeo = 30 | SCOPHP,ATES = 4.21 |

| Input 1 | Natural Gas (11 kWh/m3; 0.74 kg/m3) | Electricity | Electricity | Electricity | Electricity (Heat pumpATES; submersible pump) |

| Formula | |||||

| Value | 92.76 m3 | 0.33 MWh | 0.38 MWh | 0.03 MWh | 0.24 MWh |

| Input 2 | O2 | HeatDC | HeatRiv | HeatGeo | HeatATES |

| Formula | stoichiometric ration | ||||

| Value | 274 kg | 0.67 MWh | 0.62 MWh | 0.97 MWh | 0.76 MWh |

| Output 1 | CO2 | ||||

| Formula | stoichiometric ration | ||||

| Value | 189 kg | ||||

| Output 2 | H2O | ||||

| Formula | stoichiometric ration | ||||

| Value | 154 kg | ||||

| Output 3 | Further linearly scaled elementary flows from ecoinvent * dataset “heat production, natural gas, at boiler condensing modulating >100 kW—Europe without Switzerland” | ||||

| Marginal Cost | Natural gas EUAs | Electricity | Electricity | Electricity | Electricity |

| Example (1) | Example (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 500 MWh | 150 MWh | |

| 270 MWh | 270 MWh | |

| 230 MWh | 0 MWh |

| HT-ATES Heat Provided to DHN [GWh] | Heat Extracted [GWh] (Efficiency * [%]) | Discharge Time Horizon [h] (Discharge Operating Hours [h]) | Direct HT-ATES Cost [M EUR] (per HT-ATES Heat Provided to DHN [EUR/MWh]) | Net Cost DHN [M EUR] (per HT-ATES Heat Provided to DHN [M EUR/MWh]) | Direct HT-ATES Climate Change [kt CO2e] (per HT-ATES Heat Provided to DHN [kg CO2e/MWh]) | Net Climate Change DHN [kt CO2e] (per HT-ATES Heat Provided to DHN [kg CO2e/MWh]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

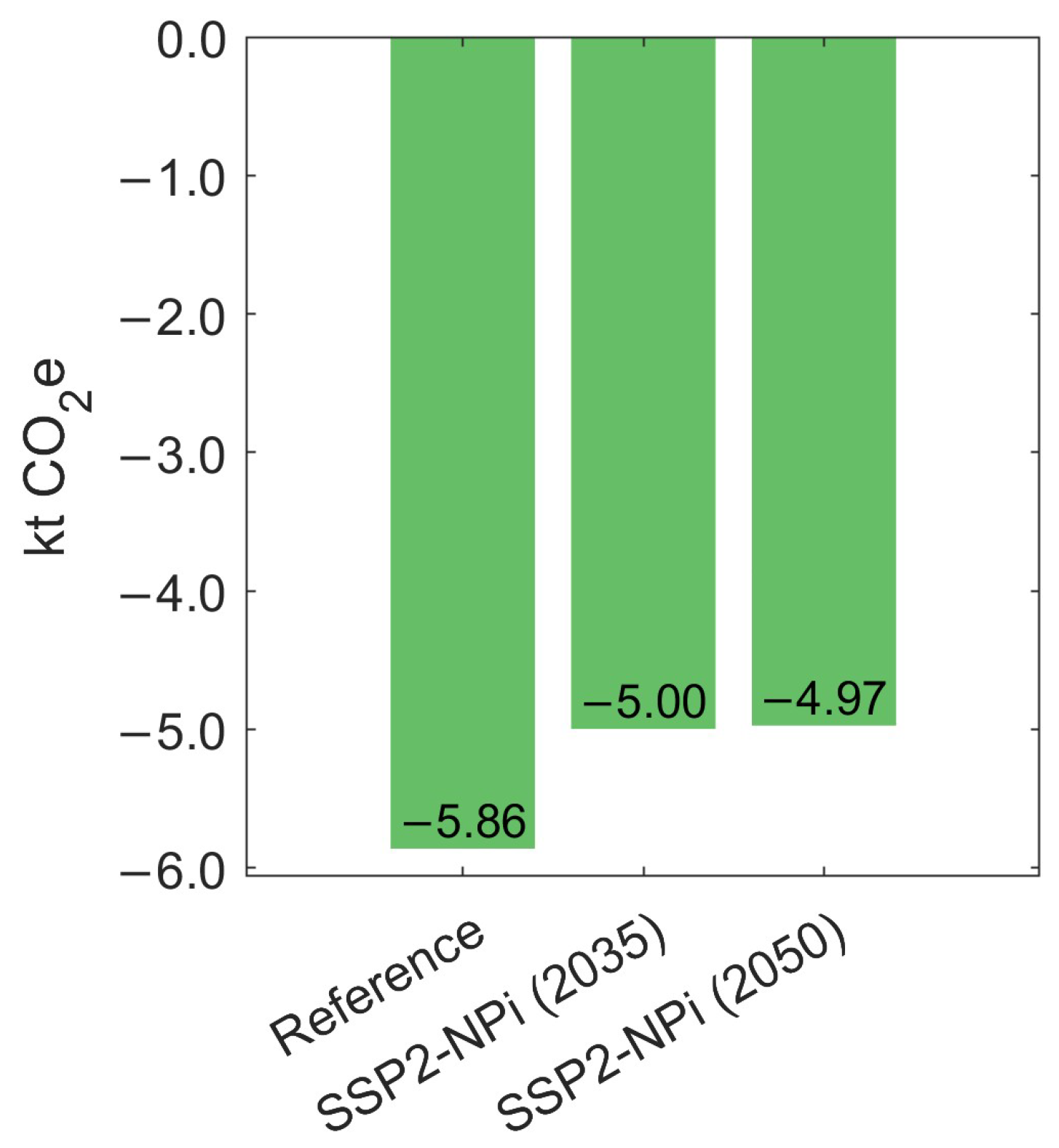

| MO | 51.8 | 39.5 (77.9) | 4251 (3299) | 1.34 (25.9) | −1.09 (−21.0) | 1.89 (36.4) | −5.86 (−113) |

| NG | 26.7 | 20.4 (40.2) | 5088→ (1759) | 0.88 (33.1) | −0.72 (−27.0) | 0.98 (36.8) | −5.84 (−219) |

| IN | 53.5 | 40.9 (80.6) | 3359 (3359) | 1.39 (25.9) | −0.70 (−13.1) | 1.95 (36.4) | −4.99 (−93) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scholliers, N.; Ohagen, M.; Schebek, L.; Sass, I.; Zeller, V. Modeling Merit-Order Shifts in District Heating Networks: A Life Cycle Assessment Method for High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integration. Energies 2026, 19, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010212

Scholliers N, Ohagen M, Schebek L, Sass I, Zeller V. Modeling Merit-Order Shifts in District Heating Networks: A Life Cycle Assessment Method for High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integration. Energies. 2026; 19(1):212. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010212

Chicago/Turabian StyleScholliers, Niklas, Max Ohagen, Liselotte Schebek, Ingo Sass, and Vanessa Zeller. 2026. "Modeling Merit-Order Shifts in District Heating Networks: A Life Cycle Assessment Method for High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integration" Energies 19, no. 1: 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010212

APA StyleScholliers, N., Ohagen, M., Schebek, L., Sass, I., & Zeller, V. (2026). Modeling Merit-Order Shifts in District Heating Networks: A Life Cycle Assessment Method for High-Temperature Aquifer Thermal Energy Storage Integration. Energies, 19(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010212