Abstract

Headspace (HS) in anaerobic batch biodigesters is a critical design parameter that modulates pressure stability, gas–liquid equilibrium, and methanogenic productivity. This systematic review, guided by PRISMA 2020, analyzed 84 studies published between 2015 and 2025, of which 64 were included in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis. The interplay between headspace volume fraction , operating pressure, and normalized methane yield was assessed, explicitly integrating safety and instrumentation requirements. In laboratory settings, maintaining a headspace volume fraction (HSVF) of 0.30–0.50 with continuous pressure monitoring P(t) and gas chromatography reduces volumetric uncertainty to below 5–8% and establishes reference yields of 300–430 NmL CH4 g−1 VS at 35 °C. At the pilot scale, operation at 3–4 bar absolute increases the CH4 fraction by 10–20 percentage points relative to ~1 bar, while maintaining yields of 0.28–0.35 L CH4 g COD−1 and production rates of 0.8–1.5 Nm3 CH4 m−3 d−1 under OLRs of 4–30 kg COD m−3 d−1, provided pH stabilizes at 7.2–7.6 and the free NH3 fraction remains below inhibitory thresholds. At full scale, gas domes sized to buffer pressure peaks and equipped with continuous pressure and flow monitoring feed predictive models (AUC > 0.85) that reduce the incidence of foaming and unplanned shutdowns, while the integration of desulfurization and condensate management keep corrosion at acceptable levels. Rational sizing of HS is essential to standardize BMP tests, correctly interpret the physicochemical effects of HS on CO2 solubility, and distinguish them from intrinsic methanogenesis. We recommend explicitly reporting standardized metrics (Nm3 CH4 m−3 d−1, NmL CH4 g−1 VS, L CH4 g COD−1), absolute or relative pressure, HSVF, and the analytical method as a basis for comparability and coupled thermodynamic modeling. While this review primarily focuses on batch (discontinuous) anaerobic digesters, insights from semi-continuous and continuous systems are cited for context where relevant to scale-up and headspace dynamics, without expanding the main scope beyond batch systems.

1. Introduction

Batch anaerobic digestion (AD) has become an essential tool in research on the valorization of agro-industrial organic waste, allowing for the evaluation of biodegradability and biochemical methane potential (BMP) of different substrates under controlled conditions [1]. In these systems, the biodigester is loaded only once with substrate and inoculum and hermetically sealed during the fermentation period, enabling the production and accumulation of biogas without continuous feeding or discharge [2]. Although this operating scheme simplifies control and promotes experimental reproducibility, it introduces a frequently underestimated design parameter: headspace (HS), defined as the gas volume available above the liquid phase of the reactor [3].

The HS (hybrid storage) plays critical roles that go beyond mere gas accumulation. From a physicochemical perspective, it regulates internal pressure, gas solubility, and the equilibrium between the liquid and gas phases (CO2, CH4, H2S, NH3), all of which are governed by Henry’s law and operating conditions [4]. A large gas volume buffers pressure variations and facilitates sampling, but it can induce excessive CO2 outgassing, raise the pH, and alter the carbonate–bicarbonate equilibrium, increasing the risk of inhibition by free ammonia in nitrogen-rich substrates. Conversely, a reduced HS increases the partial pressure of gases, promotes their dissolution in the liquid phase, and can alter mass transfer kinetics and biogas composition [5]. This complex balance makes the HS a direct determinant of the efficiency, stability, and safety of the anaerobic process [6].

The design of the HS varies substantially depending on the scale and purpose of the reactor [7]. In laboratory BMP tests, volume fractions of 30–50% are typically used to ensure stable pressure and facilitate correction of measurements to standard conditions [8]. In contrast, in pilot or industrial digesters, the HS is maintained between 10 and 25%, incorporating flexible domes or external gasometers that dampen pressure spikes and reduce structural risks [9]. However, there is no consensus on the optimal sizing, such as the physicochemical conditions, substrate composition, and agitation regimes nonlinearly alter the gas–liquid interaction and the volumetric methane yield [10].

Recent literature shows a growing interest in quantitatively modeling the effects of HS. Extensions of the ADM1 model (Anaerobic Digestion Model No.1) have explicitly incorporated the gas phase, demonstrating that variations in HS pressure modify pH dynamics, CO2 solubility, and the availability of volatile intermediates [11]. This approach has allowed correlation of the fraction with methane yield and reactor stability parameters, opening the possibility of optimizing the design through coupled thermodynamic simulation [12]. However, the lack of comparative systematization of scales, operating strategies, and quantitative results limits the ability to extrapolate conclusions and standardize experimental protocols [13].

Therefore, this review proposes a comprehensive and comparative synthesis of HS behavior in batch biodigesters. Verifiable evidence on the effects of headspace volume fraction, pressure, and methane production on operational safety is compiled and analyzed to identify quantitative patterns and design criteria that support modeling and scale-up of anaerobic digestion systems. In this way, the work seeks to bridge the gap between empirical practice and theoretical-predictive foundations, providing a robust scientific basis for the rational design of more efficient and sustainable biodigesters.

2. Systematic Review Methodology

This review was developed following the guidelines of the PRISMA 2020 protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [14] with the purpose of ensuring transparency, reproducibility and traceability in the collection, selection and analysis of scientific literature related to the design, operation and modeling of headspace in batch biodigesters.

2.1. Search Strategy and Databases

The literature search was conducted between July and September 2025 in Scopus and PubMed. Search equations were designed a priori, combining controlled descriptors and free terms with Boolean operators, aimed at capturing studies on anaerobic digestion and the influence of headspace on biogas generation and measurement. The search equations combined keywords and Boolean operators under the general format:

2.1.1. For Scopus

(“anaerobic digestion” OR “biochemical methane potential” OR “BMP test”) AND (“headspace” OR “gas phase” OR “gas volume ratio” OR “VHS/Vtot”) AND (“biogas yield” OR “methane production” OR “pressure” OR “CO2 solubility” OR “gas-liquid equilibrium”).

2.1.2. For PubMed

(“anaerobic digestion”[Title/Abstract] OR “biochemical methane potential”[Title/Abstract] OR “BMP test”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“headspace”[Title/Abstract] OR “gas phase”[Title/Abstract] OR “gas volume ratio”[Title/Abstract] OR “Vhs/Vtot”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“biogas yield”[Title/Abstract] OR “methane production”[Title/Abstract] OR “pressure”[Title/Abstract] OR “CO2 solubility”[Title/Abstract] OR “gas-liquid equilibrium”[Title/Abstract]).

To maximize coverage, we included synonyms for headspace (e.g., “gas cap,” “gas volume,” “gas retention zone”) and terms related to reactor scale (lab scale, pilot scale, industrial scale). No geographical or language restrictions were applied, although peer-reviewed articles in English and Spanish were prioritized.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Peer-reviewed scientific articles published between 2015 and 2025.

- Experimental, comparative or modeling studies that explicitly report the headspace fraction () or related parameters (pressure, gas volume, CH4 yield). For this review, batch anaerobic digesters are operationally defined as systems loaded once with substrate and inoculum, hermetically sealed during fermentation without continuous feeding or discharge. Semi-continuous and continuous systems (e.g., CSTR, UASB) are not considered batch but are referenced in comparative analyses to provide context on headspace dynamics at larger scales, without expanding the primary scope.

- Publications that present verifiable data on pressure, temperature, volume or composition of biogas. For the purposes of this review, “verifiable data” were defined as quantitative information explicitly reported in the publication (in text, tables, or figures), consistent throughout the manuscript, and traceable to original sources through valid DOIs or accessible full-text references, enabling cross-validation during data extraction.

- Book reviews or chapters with active DOI and verifiable access.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Documents without quantitative information related to headspace: absence of (), volume/gas phase ratio, measured pressure, or its impact on biogas/methane yield.

- Theses, technical reports or gray literature without peer review or verifiable DOI/URL, or without access to the full text.

- Duplicate records or studies with verifiable inconsistencies between text, tables and/or figures (e.g., discrepancies in (), pressure or units).

- Studies evaluating aerobic digestion, composting, nitrification/denitrification, photofermentative processes, oxy-fermentations, or other non-anaerobic technologies; or anaerobic studies that do not address the measurement or effect of headspace on pressure, gas–liquid equilibrium, or CH4 yield.

2.3. Study Selection Process

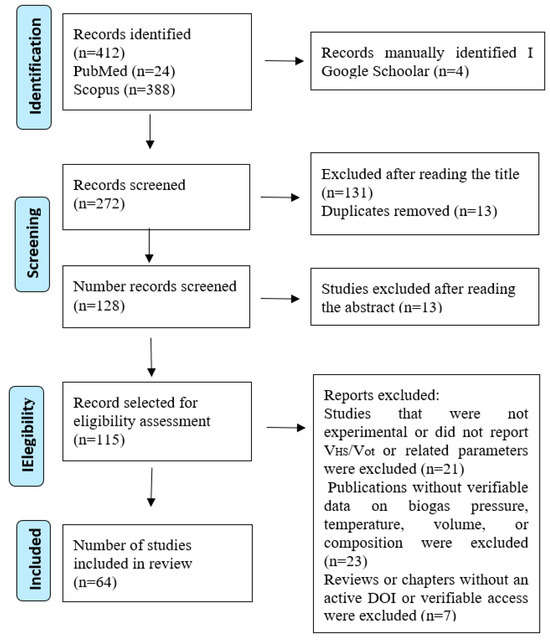

The search strategy identified 416 records: Scopus (n = 388), PubMed (n = 24), and a manual search in Google Scholar (n = 4). After initial cleaning (duplicate removal and first screening by title), 272 references were submitted for evaluation. At this stage, 131 were excluded for thematic irrelevance, and 13 additional duplicates were removed, leaving 128 for screening by abstract (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flowchart of the selection process.

In the abstract review, 13 records were excluded for not meeting the required methodological and reporting criteria, leaving 64 articles to proceed to full-text evaluation. In this eligibility phase, 51 studies were excluded for the following reasons: they were not experimental or did not explicitly report the headspace fraction () or related parameters (pressure, gas volume, CH4 yield) (n = 21); they lacked verifiable data on pressure, temperature, volume, or biogas composition (n = 23); or they were reviews/chapters without an active DOI or verifiable access (n = 7). Finally, 64 studies were included in qualitative and quantitative synthesis.

The diagram details the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion phases, with the counts at each stage and the reasons for exclusion in full text, in accordance with PRISMA 2020. The flow documents the transition from 416 initial records to 64 included studies.

2.4. Data Extraction and Validation

The following quantitative and operational parameters were extracted from each selected publication:

- Scale and type of reactor (BMP, laboratory, pilot, industrial).

- Primary substrate type.

- Volumetric fraction of headspace ().

- Operating pressure and temperature.

- Biogas monitoring method (GC, NDIR, flow meters).

- Specific methane production (mL CH4·g−1 VS. or L CH4·L−1·d−1).

The data were verified by cross-referencing the numerical information with the original sources and their DOIs. In the case of ranges or values reported under non- standard conditions, they were normalized to 101.3 kPa and 0 °C to ensure comparability of the results.

2.5. Analysis and Synthesis of Information

A mixed-methods approach was used, combining narrative synthesis and quantitative analysis. Studies were grouped by scale of operation and substrate type, among other relevant variables. The verified data were structured in comparative matrices, and the effects of headspace fraction and operating pressure on methanogenic yield were analyzed to interpret the influence of headspace on CO2 solubility. Finally, the review was supplemented with safety considerations, given their impact on the design and operation of biodigesters.

2.6. Limitations of the Review

Despite the rigorous application of the PRISMA protocol, it is acknowledged that the available literature exhibits heterogeneity in the way headspace volume, internal pressures, and gas correction conditions are reported. Some studies lack unit standardization or sufficient information to calculate the ratio .

However, the convergence of multiple experimental sources and reviews made it possible to identify consistent trends that support the proposed ranges and the predictive equation presented in Section 7.

3. Technical Fundamentals of Headspace

In batch-operated biodigesters, the HS constitutes the gaseous phase confined above the liquid digestion phase and plays a crucial role in thermodynamics, gas–liquid mass transfer, acid-base equilibria, and operational safety of the system. From a macroscopic perspective, the internal pressure results from the accumulation of gas moles according to the equation of state, while at the species level, partial pressures regulate solubility equilibria and the direction of transfer flows. These interactions are modulated by temperature, reactor geometry, the volumetric ratio of HS to the total volume, and venting and storage strategies. Table 1 synthesizes the key physicochemical parameters, design relations, and safety considerations, with primary references; their relevance to design and operation is discussed below.

Batch biodigesters with moderate pressures and under mesophilic or thermophilic conditions, the gas behavior can approximate that of an ideal gas, such that the pressure P in the HS satisfies PVHS = ngRT, where ng is the total moles accumulated, VHS is the HS volume, and T is the temperature [15]. This relationship reveals the buffering role of a sufficiently large VHS: for the same biogas production pulse, the pressure increase is smaller than the larger VHS is, which reduces the risk of overpressure and improves the repeatability of measurements. This effect can be expressed as a gaseous “capacitance” Ce = (∂ng/∂P)T = VHS/(RT), which increases linearly with VHS and T; in systems with domes or flexible gasometers, the elasticity of the container increases the effective capacitance, attenuating pressure spikes [16]. However, the reduction in partial pressure by frequent venting or operation at low back pressure favors the shift in the gas–liquid equilibrium towards the gas phase, intensifying the stripping of volatile acid species.

Dalton’s law allows the total biogas pressure to be partitioned into partial pressures, Pi = yi P. Combined with Henry’s law, this enables quantification of the solubility of gases such as CO2 and H2S, expressed as . The Henry constant Hi(T) decreases with temperature following a van’t Hoff-type relationship, ; consequently, under thermophilic conditions, the lower solubility of CO2 and H2S increases their volatility, altering the biogas composition and the acid-base status of the liquid digestion phase. For ammonia, gas–liquid partitioning depends on the N/NH3 equilibrium, whose pKa ≈ 9.25 at 25 °C and decreases with temperature. Therefore, increases in pH and T raise the fraction of free NH3, entailing a greater risk of biological inhibition [17]. These interactions are modulated by the carbonate system, characterized by pKa1 ≈ 6.35 and pKa2 ≈ 10.33 [18]. CO2 stripping tends to raise pH and effective alkalinity, shifting the CO2 (aq)--- equilibria. Although this phenomenon can contribute to deacidification during the initial phase of acidogenesis, it also increases the fraction of free NH3 and, depending on pH, alters reduced-sulfur speciation (H2S/HS−), with implications for both biological toxicity and system corrosion [19].

From a design perspective, the volumetric ratio represents a fundamental compromise between operational safety, gas metrology, and the structural compactness of the biodigester. In laboratory systems, such as BMP bottles and experimental reactors, typical ratios between 0.30 and 0.50 are recommended to facilitate sampling and prevent overpressures, always correcting biogas volumes to standard conditions and discounting water vapor according to guidelines such as VDI 4630 and equivalent methodological consensus [20]. At pilot and farm scales, internal ratios of 0.10 to 0.25 are commonly used, complemented by domes or flexible storage systems that increase the effective gas capacitance , providing mechanical damping and reducing pressure fluctuations [21]. The reactor geometry, particularly the height-to-diameter ratio and the arrangement of baffles, along with the nature of the materials, influences hydrodynamics, foam formation, and selective permeability to trace compounds. In this context, materials such as stainless steel, fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP) and EPDM/PTFE elastomer membranes are selected for their chemical compatibility against acid gases such as H2S and volatile bases such as NH3, although permeability, thermal resistance and UV radiation aging must be considered, factors that directly affect the durability of the system [22].

In terms of safety, the sizing and certification of relief valves must ensure that the setpoint remains below the design pressure , with controlled biogas flow to flares, consumers, or venting systems, and the incorporation of backflow prevention devices to avoid flame flashbacks, in accordance with NFPA (2021) and ATEX Directive 2014/34/EU (2014). Similarly, environmental monitoring of H2S and CH4, proper condensate management, and early desulfurization through biological oxidation, adsorption on ferric oxides, or chemical scrubbing are effective strategies for mitigating occupational risks and reducing corrosion [23]. Ultimately, continuous instrumentation of pressure, temperature, and composition in the biogas storage system is not only a regulatory safety requirement but also essential for accurately interpreting the stability, performance, and efficiency of the biogas process.

Table 1.

Physicochemical and design parameters relevant to headspace in batch biodigesters and safety considerations.

Table 1.

Physicochemical and design parameters relevant to headspace in batch biodigesters and safety considerations.

| Category | Parameter/Relationship | Typical Value/Expression | Technical Comment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas status | Equation of state | PVHS = ng RT | Ideal gas equation valid at moderate pressures; it is recommended to correct for water vapor when normalizing dry biogas | [24] |

| Gaseous capacitance | Ce = (∂ng/∂ P)T | Ce = VHS/(RT) | Capacitance increases with dome volume; it reduces pressure variation . Flexible domes increase effective capacitance. | [25] |

| Partial pressure | Dalton’s Law | Pi = yiP | Determine the equilibrium concentration using Henry’s Law and the mass transfer driving force | [26] |

| Henry’s constant (CO2) | HCO2 (25 °C) ≈ 29 bar·m3·kmol−1; d(ln H)/d(1/T) ≈ ΔHsol/R. | It decreases with temperature, increasing “stripping” in thermophilic. | [27] | |

| Henry’s constant (H2S) | HH2S (25 °C) ≈ 1.0 bar·m3·kmol−1 | It exhibits high solubility. Speciation depends on pH (H2S/HS− equilibrium). | [27] | |

| Balance | pKa, | pKa ≈ 9.25 (25 °C), decrece con T | The fractionation of free increases with pH and temperature; risk of biological inhibition at high values. | [28] |

| Gas–liquid transfer | Gas–liquid mass transfer flow | Ni = kLa(C − C∗) | kLa~10−3–10−2 s−1 in sludge with solids; intermittent agitation improves but may induce foaming. | [29] |

| Carbonate system | pKa1/pKa2 | pKa1 ≈ 6.35; pKa2 ≈ 10.33 (25 °C) | “Stripping” raises pH and alkalinity; it interacts with the free ammonia balance. | [30] |

| Ranges VHS/Vtot | Laboratory vs. pilot/farm | BMP: 0.30–0.50; Pilot/farm: 0.10–0.25 | Compromise between metrological safety and structural compactness. | [31] |

| Materials | Chemical compatibility | Stainless steel, GRP, EPDM/PTFE | Materials resistant to H2S and NH3; attention to permeability and thermal or UV aging of membranes. | [32] |

| Security | Relief and venting | Setpoint < Pdesign; non-return valve and torch. | Compliance with NFPA/ATEX regulations; CH4 and H2S monitoring; gas line condensate management. | [33] |

Note. Symbols and abbreviations: = total gas pressure (bar or Pa); = headspace volume (m3); = number of moles of gas (mol); = universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1); = absolute temperature (K); = gas capacitance, defined as (mol·bar−1 or mol·Pa−1); = partial pressure of component (bar or Pa); = mole fraction of component in gas phase (dimensionless); = equilibrium concentration of component in liquid phase (mol·m−3); = temperature-dependent Henry’s law constant (bar·m3·mol−1); = molar enthalpy of solution (J·mol−1); = molar flow rate of component transfer (mol·m−2·s−1); = volumetric mass transfer coefficient (s−1); = concentration of the solute in the liquid phase (mol·m−3); = equilibrium concentration in the liquid phase (mol·m−3); , , = negative logarithms of the dissociation constants of the acid-base system (dimensionless); = total volume of the reactor (m3); = design pressure of the system (bar or Pa). Material abbreviations: PRFV = fiberglass reinforced plastic); EPDM = ethylene propylene diene monomer (a corrosion-resistant elastomer); PTFE = polytetrafluoroethylene (commercially known as Teflon).

4. Influence of Headspace on Process Performance

The HS, defined by the free gas volume, internal pressure, and gas composition, is an operational parameter that modulates the physicochemical and microbiological equilibria in anaerobic digestion. The results summarized in Table 2 indicate that this variable affects methane production and rate, biogas composition, reactor stability, and the transfer of inhibitory or corrosive gases.

Table 2.

Headspace in biogas batch systems and operational considerations.

Regarding methane production and rate, studies agree that the volume and pressure of the HS alter both the measurement and the kinetics of the process. Himanshu et al. [34] determined that by increasing the free volume of the HS from 50 to 180 mL in BMP tests, the internal pressure decreased and a higher apparent biogas production was obtained, without notable variations in the CH4 fraction. This behavior is interpreted as an effect on gas compressibility and release, rather than on methanogenic activity. Hafner et al. [31]. They corroborated this phenomenon by quantifying measurement errors of up to 24% when the HS represented only 25% of the total volume, showing that reduced gas fractions cause overpressure and delay in the volume reading.

The effect of pressure on bioconversion also depends on the substrate. Valero et al. [35]. They recorded decreases in methane in coffee residues when the overpressure exceeded 600 mbar, while no variations were observed in cocoa husks and manure, indicating a differential sensitivity related to organic composition and buffering capacity. Similarly, Yan et al. [25] showed that a moderate HS pressure (3–6 psi, 0.2–0.4 bar) increased the conversion of volatile solids and CH4 production by 10–31%, which suggests that slight gas confinement can intensify mass transfer between phases and improve the availability of soluble intermediates.

More recent results confirm this trend. Sharma et al. [49] used an initial pressure of 3.3 psi (~0.23 bar) in mixed reactors and observed an increase in methanogenic productivity, attributable to a more stable equilibrium between gas production and solubilization. Qian et al. [50] analyzed digesters pressurized to 1.0 MPa and concluded that controlling the pressure in the headspace (HS) intensifies anaerobic digestion by modifying the solubility of CO2 and allowing temporary retention of CH4, although high pressures may reduce the total volume of biogas. These findings are explained by Henry’s solubility principle: as pressure increases, CO2, being more soluble than CH4, is preferentially transferred to the liquid phase, generating a residual biogas with a higher proportion of methane [51].

The composition of biogas is also influenced by the headspace gas. Koch et al. [38] showed that an initial flush with N2/CO2 (80/20) increased methane production by more than 20% compared with pure N2, indicating that the initial presence of CO2 modulates the system’s acid-base balance. Similarly, Liu et al. [47] reported that a headspace with 90% CO2 favored organic matter conversion (0.81 g COD per g VS removed) by redistributing carbon toward acidogenesis. These findings suggest that the initial headspace composition can steer metabolic pathways by influencing pH and the partial pressure of CO2.

Reactor stability, assessed by pH and alkalinity, is indirectly linked to the magnitude of the headspace. A smaller gas fraction increases CO2 dissolution in the liquid phase and carbonic acid formation, which can lower pH and reduce buffering capacity. Cabrita & Santos [41] emphasized that experimental designs should report the working volume–to–headspace volume ratio, as its omission limits the interpretation of alkalinity and free NH3 variations. Aworanti et al. [44] showed that high internal pressure alters NH3 partitioning between phases, increasing its concentration in the liquid and, consequently, its inhibitory potential.

Foam and crust formation depend on the balance between gas release and bubble retention. Wu et al. [51] observed that bottles with a larger headspace fraction (80%) produced 14–23% more methane than those with a smaller gas volume, a result associated with lower resistance to biogas release and a more continuous release rate. Although the available studies do not directly quantify foam, this behavior suggests that headspace plays a role in bubble rise dynamics and solids training.

Regarding gaseous and corrosive inhibitors, the relationship between headspace and H2S removal has been experimentally demonstrated. Ramos et al. [42] reported that H2S removal efficiency dropped from 99% to 15% when headspace volume was reduced from 50 L to 1.5 L in micro-oxygenated reactors, evidencing mass-transfer limitations in confined spaces. Similarly, Song et al. [46] introduced air into the headspace of reactors treating poultry manure and observed a decrease in H2S (~1015 ppm) along with a 6.4% increase in methane. These findings show that headspace control affects not only biogas production but also its quality and the corrosiveness of the surrounding environment.

Taking together, the evidence in Table 2 shows that headspace volume and pressure govern the balance among gas solubility, mass transfer, and the digestate’s chemical conditions. Intermediate gas fractions (0.50–0.75 of total volume) help minimize measurement errors and keep internal pressures within ranges that do not constrain biochemical processes [47]. In contrast, pressures above 1 bar or very small headspaces can cause excessive CO2 dissolution, shift pH, and hinder biogas release. As noted by Kouzi et al. [48] the lack of systematic reporting on these parameters limits predictive modeling of reactor performance. Therefore, future studies should quantitatively report headspace volume, operating pressure, gas composition, and stability indicators (pH, alkalinity, NH3, VFA) to derive empirical patterns and thermodynamic models for optimizing this design variable.

5. Influence of Headspace on Anaerobic Digestion According to the Scale of Operation

5.1. Influence on Physicochemical and Kinetic Processes on a Laboratory Scale

Influence on physicochemical and kinetic processes on a laboratory scale the impact of headspace manifests with distinct characteristics at different operational scales. In laboratory digesters and BMP systems, headspace (HS) ceases to be a merely auxiliary volume and becomes an active regulator of gas–liquid equilibrium, observed kinetic behavior, and the metrological validity of the data obtained. Recent literature has repeatedly demonstrated that the HS volume modulates internal pressure, gas solubility, and the distribution of inorganic carbon between the system’s phases, with these factors accounting for up to one-third of the interlaboratory variability in BMP assays reported over the last decade [52].

When the HS volume is reduced, the internal pressure increases disproportionately with respect to gas production, generating a significant increase in the solubility of CO2 in the liquid. Studies such as those by Mlinar et al. [53] have confirmed that HS/total volume ratios below 20% can lead to underestimations of up to 15–25% in net methane production due to increased retention of dissolved CO2. This retention alters alkalinity, shifts the carbonate–bicarbonate equilibrium, and modifies the pH of the medium, affecting methanogenic activity without any underlying biological phenomenon. Conversely, excessively large HS volumes favor early CO2 desorption, generating kinetic artifacts that artificially shorten the lag time and increase the apparent rate of methanogenesis, thus compromising the fit of models such as Gompertz or first-order models [54].

In addition to thermodynamic effects, recent research has highlighted the impact of headspace on mass transport dynamics. Leite et al. [55] demonstrated that agitation enhances CO2 transfer from the liquid phase when the headspace is large, thereby increasing CO2 output and altering the instantaneous biogas composition. Lauzurique et al. [56] have confirmed that this phenomenon can explain discrepancies between BMP tests performed with identical substrates but different ratios, even under nominally equivalent temperature and stirring conditions.

Another crucial aspect is the metrological quality of the data. Hafner et al. [37]. have identified a direct relationship between the pressure stability provided by the HS and the accuracy of the manometric sensors used, highlighting that variations in VHS modify the system’s sensitivity to micro-pressure fluctuations. These micro-fluctuations affect not only the calculation of the accumulated volume but also the estimation of net methane after humidity and temperature corrections, generating dispersion in comparative results between laboratories even when the equipment is identical [57].

Recent literature converges on the fact that HS in laboratory tests is a first-order physicochemical variable that conditions the solubility of gases, pH, observed kinetics, interlaboratory reproducibility and the accuracy of the manometric measurement, which justifies its explicit declaration and its standardization at the methodological level.

5.2. Operational Functions of the Headspace in Pilot Reactors and Their Impact on the Stability and Quality of the Biogas

When the process is scaled up to pilot size, the headspace takes on an operational role that transcends its function in BMP tests, acting as a pressure modulator, hydrodynamic stabilizer, load oscillation dampener, and determining factor in biogas composition. One of the most significant transformations identified in recent years is the use of the headspace as an internal compression chamber, since operating at pressures moderately higher than atmospheric increases the solubility of CO2 in the liquid, favoring CH4-enriched biogas without altering the metabolic capacity of the microorganisms [58].

Post-2020 research has shown that operating pressures between 110 and 160 kPa increase the methane fraction by 10 to 20 percentage points compared to atmospheric systems, with values ranging from 65% to 75% depending on the substrate and mixing regime [59]. This physical effect does not improve the yield per gram of degraded sludge, but it does increase the energy value of the biogas and provides greater resilience to fluctuations in influent quality [60]. Simultaneously, the increased CO2 solubility enhances bicarbonate formation, reinforcing pH stability and reducing the risk of acidification during occasional organic overloads [61].

Hydrostatic hydrolysis (HS) at pilot scale also directly contributes to foam formation and mitigation. Kougias et al. [62] demonstrated that reduced VHS values (<0.10) generate highly turbulent bubbling patterns that favor the retention of fine solids on the surface, increasing the frequency of foaming events, especially in protein or surfactant-rich matrices. Conversely, levels of 15–30% allow for the dissipation of surface energy and improve hydrodynamic stability, significantly reducing reactor collapse episodes [63].

Another recent advance has been the use of the headspace as a controlled oxidation zone for H2S. Di Costanzo et al. [64] demonstrated that micro-oxygenation of the headspace, when applied at extremely low doses, allows the removal of between 90 and 99% of H2S without compromising methanogenesis, making the headspace a useful engineered space for low-cost pre-desulfurization.

HS has been incorporated into advanced predictive control models. Studies using machine learning [65] have shown that minute pressure fluctuations in the HS contain sufficient information to predict VFA accumulation, the onset of foaming events, and efficiency losses. The inclusion of the HS in hybrid kinetic-data- driven models has enabled the prediction of failures with over 85% accuracy, positioning this variable as a strategic focus for pilot reactor management [66].

5.3. Headspace Behavior in Industrial Digesters and Operational Control and Energy Efficiency

In industrial digesters, the headspace (HS) acquires a functional relevance that surpasses its role in laboratory and pilot systems [67]. Due to the large operating volume and high loading rates, the HS becomes a space where physical, chemical, and operational phenomena converge, determining the stability and efficiency of the process [68]. Unlike small digesters, where the HS functions as a relatively simple accommodation volume, in industrial digesters its dynamics become a structural component of the reactor, influencing internal pressure, gas transfer, the damping of operating peaks, and the interaction with contaminants such as H2S, water vapor, and trace compounds [69].

A distinctive feature of industrial systems is the ability of the HS to reflect process instabilities through pressure micro-oscillations [70]. Gambelli et al. [71] have demonstrated that very small fluctuations (1–5 mbar) anticipate events of dissolved CO2 accumulation, foam formation, or decreased methanogenic activity. This behavior makes the HS a highly useful passive sensor, especially when these patterns are integrated into predictive control models capable of adjusting operation before critical deviations occur.

HS also significantly influences corrosion processes in industrial facilities. Recent studies by Vakili et al. [72] reveal that the combination of H2S, high humidity, and repeated condensation in the upper zone of digesters drastically increases the corrosion rate on exposed metal surfaces. This necessitates the consideration of H2S management strategies, such as controlled purges, micro-oxygenation, or partial dehumidification, that minimize structural deterioration without compromising the performance of the anaerobic process [73].

Another notable advance in the industrial sector is the expansion of pressurized anaerobic digestion (HPAD). Alavi et al. [74] demonstrated that operating digesters under moderate pressures (50–200 kPa) modifies CO2 solubility, favoring its retention in the liquid phase and effectively increasing the methane fraction in the biogas. In these systems, the HS acts as a regulating chamber that modulates the internal pressure and contributes to the thermodynamic stability of the reactor, clearly differing from the HS in non-pressurized reactors.

In energy terms, HS affects the stability of the biogas flow fed to cogeneration engines and upgrading systems. Neri et al. [75] demonstrated that domes equipped with a properly sized heat sink can reduce pressure pulses and stabilize gas composition, thereby enhancing electrical efficiency and minimizing mechanical wear. These dynamics also affect technologies sensitive to operational variations, such as separation membranes or pressure adsorption, whose performance is reduced when the heat sink does not adequately dampen biogas fluctuations [76]

The importance of industrial HS is clearly reflected in the comparative data presented in Table 3, which shows how the fraction progressively decreases as the operating scale increases. In 500 mL or 1 L BMP digesters, HS can represent up to 40% of the total volume, while in industrial digesters this fraction typically falls to values between 5 and 10%. This reduction has direct implications for the reactor’s internal pressure, which reaches higher values in industrial digesters (160–200 kPa compared to ~101–130 kPa in BMP tests). The increased pressure affects the solubility of gases such as CO2, modifying the biogas composition and the transfer dynamics at the liquid–gas interface [77].

Furthermore, it is evident that volumetric methanogenic productivity also increases at industrial scales due to high volumetric yield, although not necessarily due to the direct effects of the HS (hybrid storage system), but rather due to the interaction between large volume, high organic loading, and continuous operation [78]. However, the HS continues to play a crucial role in energy efficiency and stability: too low a fraction can generate recurring overpressures, while oversizing increases gas retention time and can promote thermal stratification and condensate accumulation [79].

Therefore, Table 3 not only summarizes operating parameters at various scales; it also demonstrates that headspace evolves from a mere buffer in BMP tests to a structural regulator in industrial digesters. Its influence is not limited to safety and pressure aspects, but also encompasses mass transfer phenomena, energy efficiency, equipment durability, and long-term process stability.

Table 3.

Verified parameters and methanogenic productivity ranges according to scale and headspace fraction.

Table 3.

Verified parameters and methanogenic productivity ranges according to scale and headspace fraction.

| Reactor Scale/Type | Type of Substrate | VHS/Vtot (-) | Pressure (kPa) | CH4 Production (Unit) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP (500 mL) | Bovine manure | 0.25–0.35 (compiled) | ≈101–130 | 129–366 mL CH4·g−1 VS (compiled) | [31] |

| BMP (1 L) | Anaerobic sludge | 0.30–0.40 (compiled) | ≈101–130 | 140–230 mL CH4·g−1 VS (compiled) | [8] |

| Laboratory (5 L) | Food waste | 0.20–0.30 (reported) | 110–150 | 0.6–1.2 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (reported) | [80] |

| Pilot (20 L) | Pig slurry | 0.15–0.25 (reported) | 120–160 | 0.9–1.3 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (reported) | [81] |

| Pilot (50 L) | Plant residues | 0.20–0.30 (filled) | 110–140 | 0.7–1.2 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (compiled) | [82] |

| Semi-industrial (200 L) | Sewage | 0.10–0.20 (reported) | 150–180 | 0.5–1.0 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (reported) | [83] |

| Industrial (1000 L) | Mixed substrate | 0.05–0.10 (filled) | 160–200 | 0.8–1.6 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (compiled) | [84] |

| UASB reactor | Wastewater/vinasse | 0.10–0.15 (reported) | 120–140 | 0.2–3.1 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (reported) | [85] |

| CSTR (2 m3) | Co-digested | 0.08–0.12 (compiled) | 150–180 | 1.0–1.6 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (compiled) | [75] |

| Thermophilic (10 m3) | Agricultural waste | 0.05–0.10 (compiled) | 180–220 | 1.2–2.2 L CH4·L−1·d−1 (compiled) | [86] |

Note: The term (compiled) indicates values that have been synthesized from ranges reported in the cited review articles, based on primary data from multiple experimental studies summarized therein. These are not secondary interpretations by the authors but direct compilations from the referenced sources to provide representative ranges. (Reported) refers to values directly stated in the primary study, and (filled) denotes values estimated or inferred from the study’s context where explicit data were not provided.

6. Headspace Design and Operation

The design of the HS (hybrid storage) is a critical component for the operational stability and metrological accuracy of anaerobic systems (Table 4). In laboratory tests of the BMP type (500 mL−1 L), headspace volume fraction () ratios of 0.25–0.40 allow for maintaining a gauge pressure between 101 and 130 kPa, ensuring reliable gas collection without causing CO2 supersaturation in the liquid phase. Values below 0.2 tend to increase the error in the volumetric estimation of biogas and favor digestate acidification by shifting the Henry’s law equilibrium of dissolved CO2 [41]. This effect is particularly evident in bovine manure digestions, where BMPs with HS below 25% of the total volume showed an average reduction of 10–15% in CH4 production [87].

Table 4.

Typical operating parameters and headspace volume ratios in anaerobic systems.

In benchtop reactors (5–50 L) operated at 37–38 °C, intermediate ratios (0.15–0.30) facilitate a balance between pressure damping and volumetric reactor utilization. The literature reports methane production rates between 0.6 and 1.2 L CH4·L−1·d−1 for food waste and pig slurry [98]. The performance of these systems demonstrates that increasing the HS reduces pressure oscillations associated with discontinuous gas generation and agitation, preventing leaks and stabilizing flow meter readings. From a thermodynamic perspective, a large HS acts as a “compressibility capacity” that dampens transient pressure increases (ΔP/Δt), protecting joints, sensors, and valves from mechanical overload [99].

The term (compiled) indicates values that have been synthesized from ranges reported in the cited review articles, studies, or literature, based on primary data from multiple experimental sources summarized therein. These are not secondary interpretations by the authors but direct compilations from the referenced sources to provide representative ranges. (Reported) refers to values directly stated in the primary study. Combinations like (reported/compiled) denote values that include both direct reports and compilations from reviews.

At pilot and industrial scales (≥200 L), the ratio typically decreases to 0.05–0.15 to maximize active liquid volume. Nevertheless, volumetric productivities of 0.8–1.6 L CH4·L−1·d−1 indicate that digesters with very small headspace require automatic pressure control and gas relief to avoid structural failures or oxygen ingress due to negative suction. In such cases, continuous instrumentation, such as NDIR gas analyzers and pressure transmitters, is essential to correct gas composition and to apply real-gas equations of state (van der Waals) for normalization to standard conditions [100,101].

Agitation is another factor that modulates the behavior of the HS. In small-scale, intermittent systems, manual or magnetic stirring promote homogenization without inducing excessive foam formation; however, reactors with continuous stirring generate larger gas–liquid interfaces, increasing CO2 release and bubble coalescence, which can distort biogas measurements if the dissolved gas is not compensated for [100]. Therefore, the sizing of the HS must consider not only the average pressure but also the oscillations induced by mixing, with a damping margin of at least 10% above the nominal operating pressure being recommended [102].

From a control and safety standpoint, the selection of the reactor and HS materials is critical. At pressures above 160 kPa and in the presence of H2S, carbon steels are susceptible to sulfidation, which is why industrial design standards (e.g., EN 13445 [103]) recommend stainless steel or epoxy coatings [104]. In glass or polymer reactors (BMP scale), Teflon seals and relief valves calibrated to 120 kPa are effective measures to prevent overpressures and methane leaks.

Comparative evidence from the compiled studies shows an inverse correlation between the size of the HS and the volumetric production rate: reducing the HS increases apparent productivity (L CH4·L−1·d−1) because it maximizes the usable liquid volume, although it sacrifices measurement accuracy and pH stability. Therefore, the optimal design involves a compromise between safety, accuracy, and volumetric yield. From a scientific perspective, the data in the table suggests that a moderate HS (0.10–0.25) represents the equilibrium point for mesophilic conditions, as it allows for stable operating pressure (110–160 kPa) and high specific yield without affecting system integrity [105].

Finally, temperature differences also modulate the behavior of the HS. In thermophilic digestion (55 °C), the partial pressure of water vapor and the gasification kinetics increase the absolute system pressure by 15 and 20% compared to mesophilic digestion, requiring the recalibration of gas sensors and the design of redundant valves to prevent overpressures [106].This behavior confirms that the HS is not simply an empty space, but a functional parameter that defines the physical, chemical, and safety response of the anaerobic reactor.

7. Conclusions

The comparative analysis of 64 included studies demonstrates that the headspace fraction is a key design and control parameter that modulates pressure, gas solubility, pH, and methanogenic performance across scales; in the laboratory, maintaining an HSVF of 0.30–0.50 with continuous P(t) recording, STP corrections, and GC minimizes uncertainty (≤5–8%) and establishes reference yields at 300–430 NmL CH4 g−1 VS at 35 °C; in pilot, operating at 3–4 bar absolute in controlled domes at pH 7.2–7.6 and with free NH3 below inhibitory thresholds enriches the % of CH4 of the biogas by 10–20 points without penalizing productivities (0.8–1.5 Nm3 CH4 m−3 d−1) or yields (0.28–0.35 L CH4 g COD−1) under OLR 4–30 kg COD m−3 d−1; and in plant, domes sized to dampen peaks with continuous pressure/flow monitoring and integration into the control architecture feed predictive models with AUC > 0.85 that reduce severe foaming episodes and shutdowns by 30–60%, while early desulfurization and condensate management keep corrosion within acceptable limits. In terms of design, excessively small HS values (<0.10–0.20) induce overpressure, higher dissolved CO2, acidification, and volumetric errors; excessive HS values (>0.35–0.40) favor CO2 outgassing, transiently raise the pH, and can reduce the apparent rate. Therefore, intermediate ranges (0.10–0.25 in pilot/industrial applications; 0.30–0.50 in BMP applications) represent robust operational compromises between safety, accuracy, and performance. Coupled gas–liquid modeling (extensions of ADM1) quantitatively supports that modest variations in HS can alter CH4 production by up to ~5–8% under pressurized mesophilic conditions, underscoring that HS is an active control lever rather than a mere buffer volume. Consequently, it is recommended to standardize the reporting of HSVF, absolute/relative pressure, normalized metrics (Nm3 CH4 m−3 d−1, NmL CH4 g−1 VS, L CH4 g COD−1), analytical method and inertias/agitation conditions, and incorporate calibrated relief valves, continuous instrumentation (P/T/NDIR/GC) and desulfurization/condensate management from the design stage, to separate physicochemical effects of HS from actual methanogenesis, improve inter-study comparability and enable predictive and safe scale-ups.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; He, P.; Peng, W.; Zhang, H.; Lü, F. Biochemical Methane Potential Database: A Public Platform. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekwichai, P.; Chutivisut, P.; Tuntiwiwattanapun, N. Enhancing Biogas Production from Palm Oil Mill Effluent through the Synergistic Application of Surfactants and Iron Supplements. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmaissia, A.; Hernández, E.M.; Boivin, S.; Vaneeckhaute, C. Start-Up Strategies for Thermophilic Semi-Continuous Anaerobic Digesters: Assessing the Impact of Inoculum Source and Feed Variability on Efficient Waste-to-Energy Conversion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Liang, H.; Li, G. Solubility and Exsolution Behavior of CH4 and CO2 in Reservoir Fluids: Implications for Fluid Compositional Evolution—A Case Study of Ledong 10 Area, Yinggehai. Processes 2025, 13, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihi, M.; Ouhammou, B.; Aggour, M.; Daouchi, B.; Naaim, S.; El Mers, E.M.; Kousksou, T. Modeling and Forecasting Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion Process for Sustainable Resource Energy Recovery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.S.; Parveez, M. Synergistic Effects of Anaerobic Digestion for Diverse Feedstocks: A Holistic Study on Feedstock Properties, Process Efficiency, Biogas Yield, and Economic Viability. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 87, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F.; Borja, R.; Ibelli-Bianco, C. Predictive Regression Models for Biochemical Methane Potential Tests of Biomass Samples: Pitfalls and Challenges of Laboratory Measurements. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 127, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filer, J.; Ding, H.H.; Chang, S. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assay Method for Anaerobic Digestion Research. Water 2019, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, C.; Collaguazo, G.; Streche, C.; Apostol, T.; Cocarta, D.M. Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of the OFMSW: Improving Biogas Production and Startup. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Dujany, A.; Guerin Rechdaoui, S.; Rocher, V.; Pauss, A.; Ribeiro, T. Optimization of Liquid-State Anaerobic Digestion by Defining the Optimal Composition of a Complex Mixture of Substrates Using a Simplex Centroid Design. Water 2024, 16, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, A.; Carecci, D.; Leva, A.; Guerreschi, A.; Ferretti, G.; Ficara, E. Towards Maximization of Parameters Identifiability: Development of the CalOpt Tool and Its Application to the Anaerobic Digestion Model. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 155743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, T.; Ortiz, A.P.; Schomäcker, R.; Repke, J.-U. Performance Evaluation of Different Reactor Concepts for the Oxidative Coupling of Methane on Miniplant Scale. Methane 2025, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Xie, K. Synergetic Mitigation of Air Pollution and Carbon Emissions of Coal-Based Energy: A Review and Recommendations for Technology Assessment, Scenario Analysis, and Pathway Planning. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 59, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J.J.; Urrútia, G.; Romero-García, M.; Alonso-Fernández, S. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una Guía Actualizada Para La Publicación de Revisiones Sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Ganeshan, P.; Gohil, N.; Kumar, V.; Singh, V.; Rajendran, K.; Harirchi, S.; Solanki, M.K.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; et al. Advanced Approaches for Resource Recovery from Wastewater and Activated Sludge: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, A.; Limonti, C.; Curcio, G.M. Performance Evaluation of Pressurized Anaerobic Digestion (PDA) of Raw Compost Leachate. Fermentation 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shi, S.; Tan, Q.; Wang, C.; Han, L.; Yao, J. Effects of Benthic Bioturbation on Anammox in Nitrogen Removal at the Sediment-Water Interface in Eutrophic Surface Waters. Water Res. 2023, 243, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meybodi, M.K.; Vazquez, O.; Sorbie, K.S.; Mackay, E.J.; Jarrahian, K. Equilibrium Modelling of Interactions in DETPMP-Carbonate System. In Proceedings of the Society of Petroleum Engineers—SPE Oilfield Scale Symposium, OSS 2024, Aberdeen, UK, 5–6 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzenos, C.A.; Kalamaras, S.D.; Economou, E.A.; Romanos, G.E.; Veziri, C.M.; Mitsopoulos, A.; Menexes, G.C.; Sfetsas, T.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. The Multifunctional Effect of Porous Additives on the Alleviation of Ammonia and Sulfate Co-Inhibition in Anaerobic Digestion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, S.; Nistor, M.; Liu, J. Towards Eliminating Systematic Errors Caused by the Experimental Conditions in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Tests. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.F.; Fahl, F. Biogas: Developments and Perspectives in Europe. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, Y.A.; Zhao, Z.; Yoshida, A.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Small-Scale Biomass Gasification Systems for Power Generation (<200 kW Class): A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, P.K.; Sabharwall, P. Sizing and Selection of Pressure Relief Valves for High-Pressure Thermal–Hydraulic Systems. Processes 2023, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Treu, L.; Tsapekos, P.; Luo, G.; Campanaro, S.; Wenzel, H.; Kougias, P.G. Biogas Upgrading and Utilization: Current Status and Perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Larsen, O.C.; Muhayodin, F.; Hu, J.; Xue, B.; Rotter, V.S. Review of Anaerobic Digestion Models for Organic Solid Waste Treatment with a Focus on the Fates of C, N, and P. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2024, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.J.; Luo, Y.; Chu, G.W.; Cai, Y.; Le, Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Chen, J.F. Dispersion Behaviors of Droplet Impacting on Wire Mesh and Process Intensification by Surface Micro/Nano-Structure. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 219, 115593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s Law Constants (Version 4.0) for Water as Solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 4399–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirong, C.; Zhang, W.; Heaven, S.; Banks, C.J. Influence of Ammonia in the Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5131–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, A.A.; Santos, J.M.; Timchenko, V.; Stuetz, R.M. A Critical Review on Liquid-Gas Mass Transfer Models for Estimating Gaseous Emissions from Passive Liquid Surfaces in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2018, 130, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapunov, V.N.; Saveljev, E.A.; Voronov, M.S.; Valtiner, M.; Linert, W. The Basic Theorem of Temperature-Dependent Processes. Thermo 2021, 1, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.D.; de Laclos, H.F.; Koch, K.; Holliger, C. Improving Inter-Laboratory Reproducibility in Measurement of Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP). Water 2020, 12, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarski, K.; Pilarska, A.A.; Pietrzak, M.B. Biogas Production in Agriculture: Technological, Environmental, and Socio-Economic Aspects. Energies 2025, 18, 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, P.; Xiong, Z.; Huang, B.; Peng, J.; Liu, R.; Liu, W.; Lai, B. Efficient Activation of Ferrate (VI) by Colloid Manganese Dioxide: Comprehensive Elucidation of the Surface-Promoted Mechanism. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, H.; Voelklein, M.A.; Murphy, J.D.; Grant, J.; O’Kiely, P. Factors Controlling Headspace Pressure in a Manual Manometric BMP Method Can Be Used to Produce a Methane Output Comparable to AMPTS. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; Montes, J.A.; Rico, J.L.; Rico, C. Influence of Headspace Pressure on Methane Production in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Tests. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.H.; Selvam, A.; Wong, J.W.C. Influence of Acidogenic Headspace Pressure on Methane Production under Schematic of Diversion of Acidogenic Off-Gas to Methanogenic Reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.D.; Astals, S. Systematic Error in Manometric Measurement of Biochemical Methane Potential: Sources and Solutions. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.; Bajón Fernández, Y.; Drewes, J.E. Influence of Headspace Flushing on Methane Production in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Tests. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 186, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, M.; Andres, Y.; Blel, W. Modeling of Sludge and Flax Anaerobic Co-Digestion Based on Combination of First Order and Modified Gompertz Models: Influence of C/N Ratio and Headspace Gas Volume. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 250, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leto, Y.; Mineo, A.; Capri, F.C.; Gallo, G.; Mannina, G.; Alduina, R. The Effects of Headspace Volume Reactor on the Microbial Community Structure during Fermentation Processes for Volatile Fatty Acid Production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 61781–61794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, T.M.; Santos, M.T. Biochemical Methane Potential Assays for Organic Wastes as an Anaerobic Digestion Feedstock. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.; Díaz, I.; Fdz-Polanco, M. The Role of the Headspace in Hydrogen Sulfide Removal during Microaerobic Digestion of Sludge. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 66, 2258–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi-Eshkaftakia, M.; Mockaitis, G. Structural Optimization of Biohydrogen Production: Impact of Pretreatments on Volatile Fatty Acids and Biogas Parameters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7072–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworanti, O.A.; Agbede, O.O.; Agarry, S.E.; Ajani, A.O.; Ogunkunle, O.; Laseinde, O.T.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Fattah, I.M.R. Decoding Anaerobic Digestion: A Holistic Analysis of Biomass Waste Technology, Process Kinetics, and Operational Variables. Energies 2023, 16, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, V. The Effects of Incubation and Operational Conditions on Biogas Production Karaelmas Fen Müh. Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit Üniversitesi 2017, 7, 597–601. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Mahdy, A.; Hou, Z.; Lin, M.; Stinner, W.; Qiao, W.; Dong, R. Air Supplement as a Stimulation Approach for the In Situ Desulfurization and Methanization Enhancement of Anaerobic Digestion of Chicken Manure. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 12606–12615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dong, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, W.; Litti, Y.; Liu, C.; Yan, B. The Effect of CO2 Sparging on High-Solid Acidogenic Fermentation of Food Waste. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2025, 7, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzi, A.I.; Puranen, M.; Kontro, M.H. Evaluation of the Factors Limiting Biogas Production in Full-Scale Processes and Increasing the Biogas Production Efficiency. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28155–28168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Salhotra, S.; Rathour, R.K.; Solanki, P.; Putatunda, C.; Hans, M.; Walia, A.; Bhatia, R.K. Recent Developments in Separation and Storage of Lignocellulosic Biomass-Derived Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels: A Comprehensive Review. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 204, 108417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Zeng, C.; Lian, X.; Xia, Z.; Zou, J. Research on Methane-Rich Biogas Production Technology by Anaerobic Digestion Under Carbon Neutrality: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Methane Production from Biomass by Thermochemical Conversion: A Review. Catalysts 2023, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliger, C.; Alves, M.; Andrade, D.; Angelidaki, I.; Astals, S.; Baier, U.; Bougrier, C.; Buffière, P.; Carballa, M.; De Wilde, V.; et al. Towards a Standardization of Biomethane Potential Tests. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinar, S.; Weig, A.R.; Freitag, R. Influence of Mixing and Sludge Volume on Stability, Reproducibility, and Productivity of Laboratory-Scale Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 11, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Hassan, D.; Iwasaki, M.; Yoshida, G.; Umetsu, K.; Ihara, I. Kinetic Modeling of Anaerobic Co-Digestion with Glycerol: Implications for Process Stability and Organic Overloads. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 199, 109061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, S.A.F.; Leite, B.S.; Ferreira, D.J.O.; Baêta, B.E.L.; Dangelo, J.V.H. The Effects of Agitation in Anaerobic Biodigesters Operating with Substrates from Swine Manure and Rice Husk. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauzurique, Y.; Segura, S.; Guerra, S.; Carvajal, A.; Huiliñir, C.; Poblete-Castro, I. Enhancing Methane Production Using Various Forms of Steel Shavings and Their Effect on Microbial Consortia during Anaerobic Digestion of Swine Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaouefi, Z.; Taktek, S.; Bélanger, F.; Fortin, P.; Charbonneau, J.; Lange, S.; Horchani, H. Optimized Biogas Yield and Safe Digestate Valorization Through Intensified Anaerobic Digestion of Invasive Plant Biomass. Energies 2025, 18, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wilkinson, D.W.; Wang, C.; Wilkinson, S.J. Pressurised Anaerobic Digestion for Reducing the Costs of Biogas Upgrading. BioEnergy Res. 2023, 16, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengur, O.; Akgul, D.; Calli, B. In Situ Methane Enrichment with Vacuum Application to Produce Biogas with Higher Methane Content. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 2024, 28307–28318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mario, J.; Montegiove, N.; Gambelli, A.M.; Brienza, M.; Zadra, C.; Gigliotti, G. Waste Biomass Pretreatments for Biogas Yield Optimization and for the Extraction of Valuable High-Added-Value Products: Possible Combinations of the Two Processes toward a Biorefinery Purpose. Biomass 2024, 4, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelaVega-Quintero, J.C.; Nuñez-Pérez, J.; Lara-Fiallos, M.; Barba, P.; Burbano-García, J.L.; Espín-Valladares, R. Advances and Challenges in Anaerobic Digestion for Biogas Production: Policy, Technological, and Microbial Perspectives. Processes 2025, 13, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.G.; Boe, K.; O-Thong, S.; Kristensen, L.A.; Angelidaki, I. Anaerobic Digestion Foaming in Full-Scale Biogas Plants: A Survey on Causes and Solutions. Water Sci. Technol. 2014, 69, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Krooneman, J.; Euverink, G.J.W. Strategies to Boost Anaerobic Digestion Performance of Cow Manure: Laboratory Achievements and Their Full-Scale Application Potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, N.; Di Capua, F.; Cesaro, A.; Carraturo, F.; Salamone, M.; Guida, M.; Esposito, G.; Giordano, A. Headspace Micro-Oxygenation as a Strategy for Efficient Biogas Desulfurization and Biomethane Generation in a Centralized Sewage Sludge Digestion Plant. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 183, 107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Long, F.; Liao, W.; Liu, H. Prediction of Anaerobic Digestion Performance and Identification of Critical Operational Parameters Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, O. Data Driven Modelling and Control Strategies to Improve Biogas Quality and Production from High Solids Anaerobic Digestion: A Mini Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, R.; Muñoz, R.; Polanco, M.; Díaz, I.; Susmozas, A.; Moreno, A.D.; Guirado, M.; Carreras, N.; Ballesteros, M. Biogas from Anaerobic Digestion as an Energy Vector: Current Upgrading Development. Energies 2021, 14, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonov, I.; Chorukova, E.; Kabaivanova, L. Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion for Green Energy Production: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, T.; Meister, M.; Pillei, M.; Senfter, T.; Draxl-Weiskopf, S.; Ebner, C.; Winkler, J.; Rauch, W. Impact of Design and Mixing Strategies on Biogas Production in Anaerobic Digesters. Water 2024, 16, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, D.; Mohammadi, P.; Bashardoust, P.; Eshtiaghi, N. A Comprehensive Review on the Recent Development of Anaerobic Sludge Digestions: Performance, Mechanism, Operational Factors, and Future Challenges. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudul, H.M.; Rasul, M.G.; Narayanan, R.; Akbar, D.; Hasan, M.M. Technoeconomic Assessment of Biogas Production from Organic Waste via Anaerobic Digestion in Subtropical Central Queensland, Australia. Energies 2025, 18, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Koutník, P.; Kohout, J. Addressing Hydrogen Sulfide Corrosion in Oil and Gas Industries: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Angelidaki, I.; Cetecioglu, Z.; Kong, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Tsapekos, P. Editorial: Biological Strategies to Enhance the Anaerobic Digestion Performance: Fundamentals and Process Development. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 762875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi-Borazjani, S.A.; da Cruz Tarelho, L.A.; Capela, M.I. Biohythane Production via Anaerobic Digestion Process: Fundamentals, Scale-up Challenges, and Techno-Economic and Environmental Aspects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 49935–49984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, A.; Hummel, F.; Benalia, S.; Zimbalatti, G.; Gabauer, W.; Mihajlovic, I.; Bernardi, B. Use of Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors for Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Dairy and Meat Industry By-Products for Biogas Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, X.; Gao, T.; Cheng, Z.; Fu, W.; Wang, S. Ammonia Inhibition in Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Waste: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadou, I.A.; Gioulounta, K.; Stamatelatou, K. Production of Biogas via Anaerobic Digestion. In Handbook of Biofuels Production; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 253–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellacuriaga, M.; Cascallana, J.G.; González, R.; Gómez, X. High-Solid Anaerobic Digestion: Reviewing Strategies for Increasing Reactor Performance. Environments 2021, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Q. Mass Transfer Enhancement in High-Solids Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Wastes: A Review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, T.; Qiang, F.; Liu, G.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Ai, N.; Ma, H. Soil Quality Evaluation of Typical Vegetation and Their Response to Precipitation in Loess Hilly and Gully Areas. Forests 2023, 14, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanegas, M.; Romani, F.; Jiménez, M. Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Digestion of Pig Manure with Thermal Pretreatment: Stability Monitoring to Improve the Potential for Obtaining Methane. Processes 2022, 10, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Tsompanidis, C.; Velonia, K.; Manios, T. Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Polylactic Acid. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Rechdaoui, S.G.; Jabagi, E.; Lacroix, C.; Azimi, S.; Rocher, V. Pilot-Scale Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Wastewater Sludge with Lignocellulosic Waste: A Study of Performance and Limits. Energies 2023, 16, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, A.A.; Mikheeva, E.R.; Kovalev, D.A.; Katraeva, I.V.; Zueva, S.; Innocenzi, V.; Panchenko, V.; Zhuravleva, E.A.; Litti, Y.V. Feasibility Study of Anaerobic Codigestion of Municipal Organic Waste in Moderately Pressurized Digesters: A Case for the Russian Federation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Arriaga, E.B.; Reynoso-Deloya, M.G.; Guillén-Garcés, R.A.; Falcón-Rojas, A.; García-Sánchez, L. Enhanced Methane Production and Organic Matter Removal from Tequila Vinasses by Anaerobic Digestion Assisted via Bioelectrochemical Power-to-Gas. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wachemo, A.C.; Yuan, H.R.; Li, X.J. Anaerobic Digestion Performance and Microbial Community Structure of Corn Stover in Three-Stage Continuously Stirred Tank Reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 287, 121339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, J.; Han, T.; Tian, P.; Li, G.; Li, Y. Optimization of Anaerobic Co-Digestion Parameters for Vinegar Residue and Cattle Manure via Orthogonal Experimental Design. Fermentation 2025, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, J.E.; Herrmann, C.; Petersen, S.O.; Dragoni, F.; Amon, T.; Belik, V.; Ammon, C.; Amon, B. Assessment of the Biochemical Methane Potential of In-House and Outdoor Stored Pig and Dairy Cow Manure by Evaluating Chemical Composition and Storage Conditions. Waste Manag. 2023, 168, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Domínguez, E.; Rubio, J.Á.; Lyng, J.; Toro, E.; Estévez, F.; García-Morales, J.L. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Organic Solid By-Products from Table Olive Processing: Influence of Substrate Mixtures on Overall Process Performance. Energies 2025, 18, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Tao, J.; Luo, J.; Xie, W.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, B.; Guo, G.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Cai, H.; et al. Pilot-Scale Two-Phase Anaerobic Digestion of Deoiled Food Waste and Waste Activated Sludge: Effects of Mixing Ratios and Functional Analysis. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Guldberg, L.B.; Hansen, M.J.; Feng, L.; Petersen, S.O. Frequent Export of Pig Slurry for Outside Storage Reduced Methane but Not Ammonia Emissions in Cold and Warm Seasons. Waste Manag. 2023, 169, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, F.; Yuan, H.; Zou, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Li, X. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Kitchen Waste and Fruit/Vegetable Waste: Lab-Scale and Pilot-Scale Studies. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2627–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, K.; Jariyaboon, R.; O-Thong, S.; Cheirsilp, B.; Kaparaju, P.; Wang, Y.; Kongjan, P. Performance of Pilot Scale Two-Stage Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Waste Activated Sludge and Greasy Sludge under Uncontrolled Mesophilic Temperature. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaralleh, R.M.; Kennedy, K.; Delatolla, R. Improving Biogas Production from Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Thickened Waste Activated Sludge (TWAS) and Fat, Oil and Grease (FOG) Using a Dual-Stage Hyper-Thermophilic/Thermophilic Semi-Continuous Reactor. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.Y.U.; Alves, I.; Del Nery, V.; Sakamoto, I.K.; Pozzi, E.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z. Methane Production in a UASB Reactor from Sugarcane Vinasse: Shutdown or Exchanging Substrate for Molasses during the off-Season? J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kumar, G.; Yun, Y.M.; Kwon, J.C.; Kim, S.H. Effect of Feeding Mode and Dilution on the Performance and Microbial Community Population in Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, J.T.; Warren, K.J.; Wilson, S.A.; Muhich, C.L.; Musgrave, C.B.; Weimer, A.W. An Updated Review and Perspective on Efficient Hydrogen Generation via Solar Thermal Water Splitting. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2024, 13, e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffka, F.T.S.; Behainne, J.J.R.; Parise, M.R.; De Castilho, G.J. Dynamics of the Pressure Fluctuation in the Riser of a Small Scale Circulating Fluidized Bed: Effect of the Solids Inventory and Fluidization Velocity Under the Absolute Mean Deviation Analysis. Mech. Mach. Sci. 2021, 95, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, N.; Silva, V.B.; Bispo, C.; Rouboa, A. From Laboratorial to Pilot Fluidized Bed Reactors: Analysis of the Scale-up Phenomenon. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 119, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Esparza, J.; Ibarra-Esparza, F.E.; González-López, M.E.; Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Instrumentation and Continuous Monitoring for the Anaerobic Digestion Process: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 193820–193837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Ginige, M.P.; Cheng, K.Y.; Qie, T.; Peacock, C.S.; Kaksonen, A.H. Dynamics of Gas Distribution in Batch-Scale Fermentation Experiments: The Unpredictive Distribution of Biogas between Headspace and Gas Collection Device. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.M.; Choi, Y.K.; Kan, E. Effects of Dairy Manure-Derived Biochar on Psychrophilic, Mesophilic and Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestions of Dairy Manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 13445:2021; Unfired Pressure Vessels. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Albiter, A.; Albiter, A. Sulfide Stress Cracking Assessment of Carbon Steel Welding with High Content of H2S and CO2 at High Temperature: A Case Study. Engineering 2020, 12, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crescenzo, C.; Marzocchella, A.; Karatza, D.; Molino, A.; Ceron-Chafla, P.; Lindeboom, R.E.F.; van Lier, J.B.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D. Modelling of Autogenerative High-Pressure Anaerobic Digestion in a Batch Reactor for the Production of Pressurised Biogas. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholizadeh, T.; Ghiasirad, H.; Skorek-Osikowska, A. Life Cycle and Techno-Economic Analyses of Biofuels Production via Anaerobic Digestion and Amine Scrubbing CO2 Capture. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.