Between Habit and Investment: Managing Residential Energy Saving Strategies in Polish Households

Abstract

1. Introduction

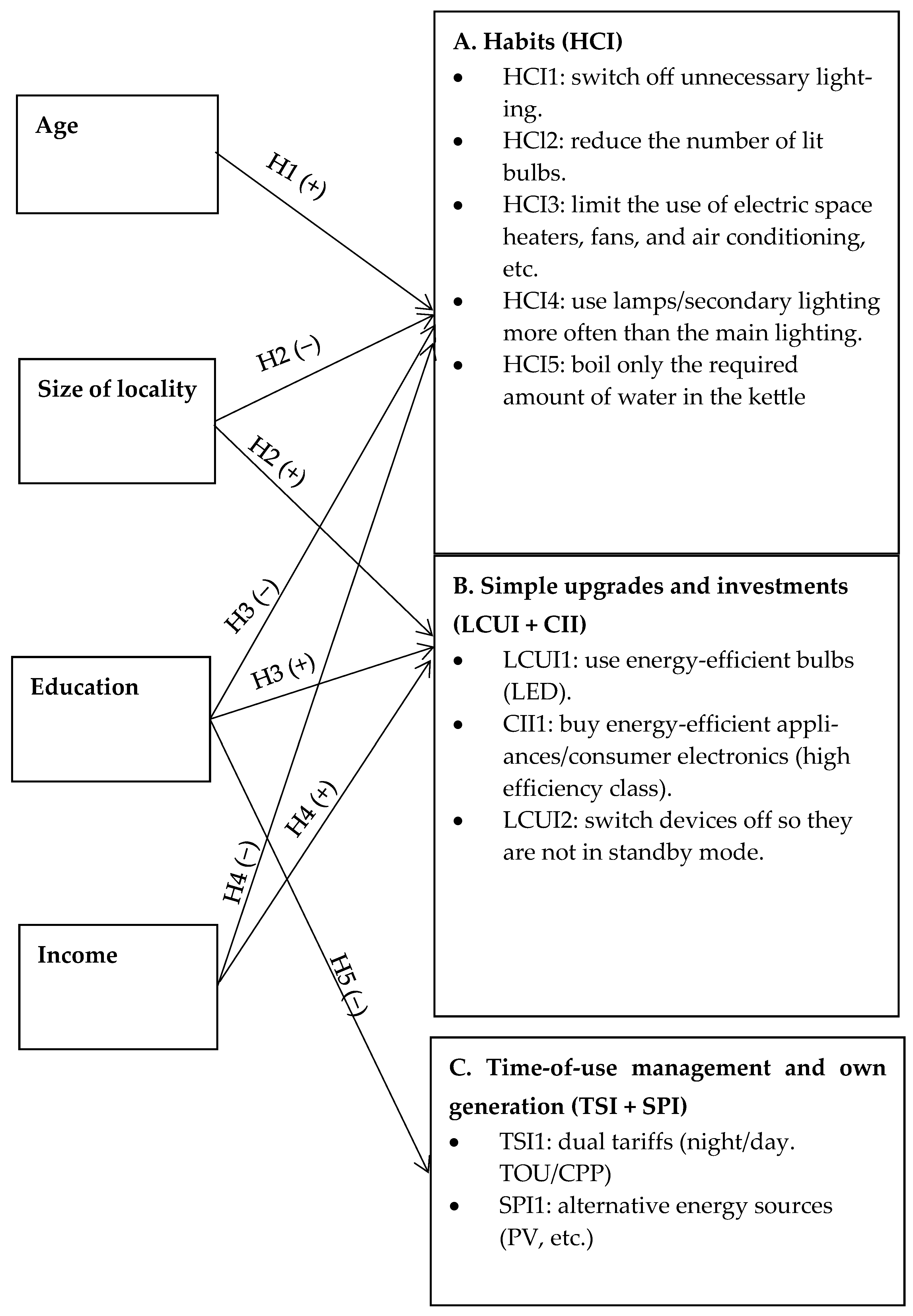

2. Theoretical Framework

- (1)

- (2)

- Technical control and light management systems such as presence sensors, daylight harvesting mechanisms, and task-ambient systems allow for significant reductions in lighting consumption while maintaining visual comfort [22,38,39,40]. In the context of Demand Response, building control integrates with network management [41,42]. LED adoption produces unambiguous energy and cost benefits [43,44], though uptake depends on income, education and innovation readiness. Younger cohorts transition faster [8,9,31]. Communication that simplifies lifecycle costs, as evidenced in energy-label reforms, further reduces intergenerational differences [10,11].

- (3)

- Prosumer oriented interventions such as PV and storage solutions are driven primarily by economic incentives and openness to innovation [45,46]. Profitability increases when consumption aligns with production or when storage mitigates temporal mismatches, particularly under time-differentiated tariffs [20,47,48]. In this context age exerts only an indirect influence through income, property ownership, risk appetite and technological openness [45,49,50,51]. Transparent information and decision support tools further reduce generational disparities [18,52].

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

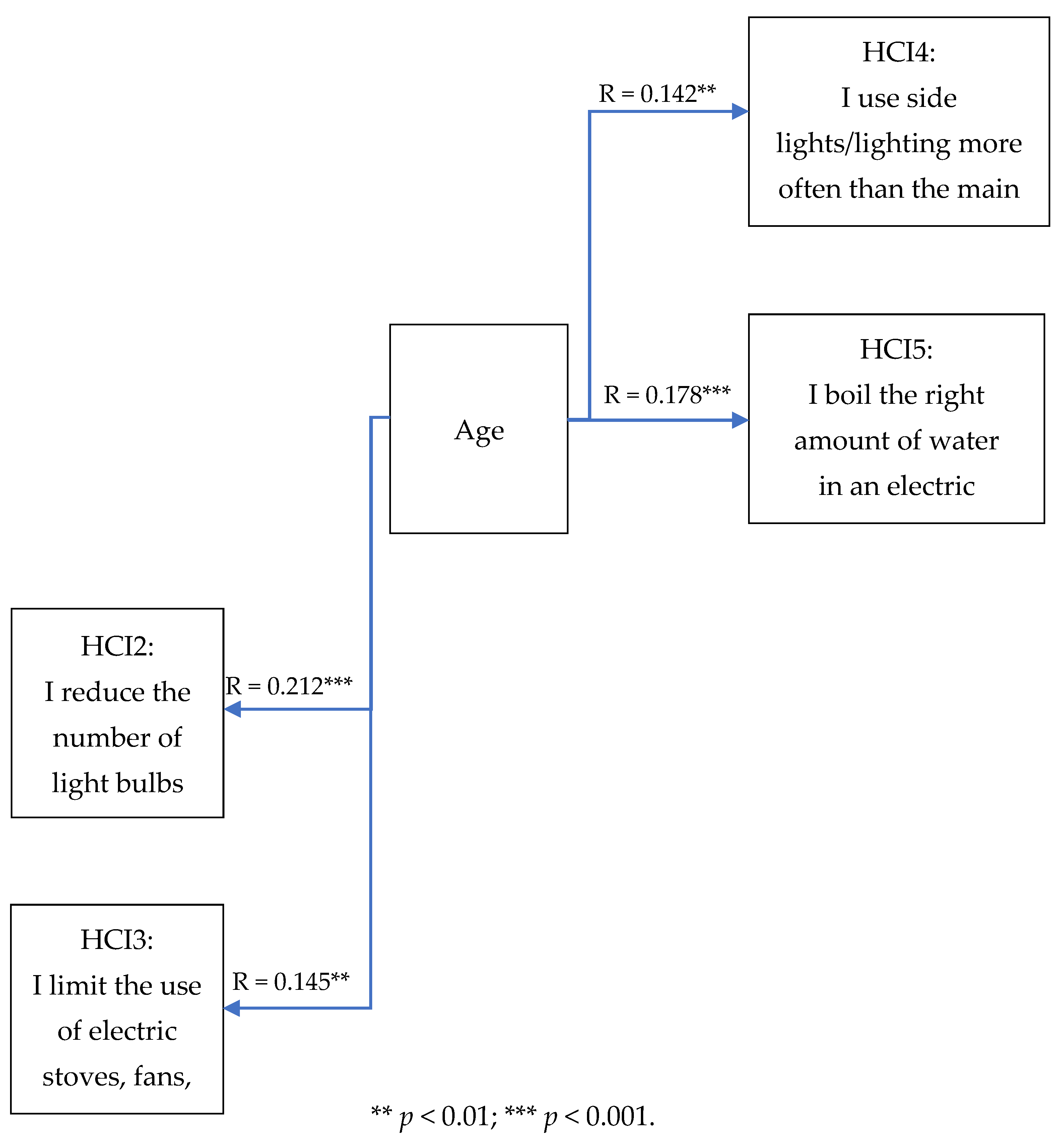

- Reducing the number of bulbs in use (R = 0.212; t = 4.341; p < 0.001);

- Boiling only the amount of water needed (R = 0.178; t = 3.604; p < 0.001);

- Limiting the use of stoves and air conditioning (R = 0.145; t = 2.930; p = 0.004);

- More frequent use of side lighting (R = 0.142; t = 2.857; p = 0.004).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Energy-Saving Strategy Categories | |

| CII | Capital-Intensive Investments (technology-oriented actions requiring financial outlays) |

| CPP | Critical Peak Pricing (tariff with substantially higher rates during peak demand periods) |

| DR | Demand Response (mechanisms enabling consumers to adjust electricity use in response to price signals or grid needs) |

| HCI | Habitual, Cost-Free Improvements (everyday low-cost behaviours requiring no financial investment) |

| LCUI | Low-Cost Upgrades & Investments (low-cost technical improvements) |

| PV | Photovoltaic system (solar panels used for household electricity generation) |

| SPI | Self-Production Interventions (renewable micro-generation, e.g., PV systems) |

| TOU | Time-of-Use tariff (electricity pricing varying by time of day) |

| TSI | Time-Shifting Interventions (time-of-use management TOU/CPP tariffs) |

| Statistical Symbols | |

| R | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (unitless) |

| p | significance level (p-value) |

| t(n − 2) | test statistic for Spearman’s rank correlations significance |

| α | assumed significance level (α = 0.05) |

| Units Used in the Article | |

| W | watt (standby consumption) |

| kWh | kilowatt-hour (energy consumption) |

| % | percentage |

| (no units) | Likert-type scales used for behavioural measures |

References

- Rausser, G.; Strielkowski, W.; Mentel, G. Consumer Attitudes toward Energy Reduction and Changing Energy Consumption Behaviors. Energies 2023, 16, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N. The Evolution of Sustainable Investment: The Role of Decentralized Finance and Green Bonds in the Efficiency and Transparency of Green Finance. FinTech Sustain. Innov. 2025, 1, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupik, S.; Kos-łabędowicz, J.; Trzęsiok, J. How to Encourage Energy Savings Behaviours? The Most Effective Incentives from the Perspective of European Consumers. Energies 2021, 14, 8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, G.; Dal Cin, E.; Rech, S. Integrating Energy Generation and Demand in the Design and Operation Optimization of Energy Communities. Energies 2024, 17, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R.; Gifford, R. Please Turn off the Lights: The Effectiveness of Visual Prompts. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Becerra, V.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D.; Foster, J.M.; Roberts, K.; Hutchinson, D.; Fawcett, J. Demand Response Model Development for Smart Households Using Time of Use Tariffs and Optimal Control—The Isle of Wight Energy Autonomous Community Case Study. Energies 2020, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintoudi, A.D.; Bezas, N.; Zyglakis, L.; Isaioglou, G.; Timplalexis, C.; Gkaidatzis, P.; Tryferidis, A.; Ioannidis, D.; Tzovaras, D. Incentive-Based Demand Response Framework for Residential Applications: Design and Real-Life Demonstration. Energies 2021, 14, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.; Santos, B.; Paolo, B.; Quicheron, M. Solid State Lighting Review—Potential and Challenges in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, M.M.; Jasmon, G.B.; Mokhlis, H.; Bakar, A.H.A. Analysis of the Performance of Domestic Lighting Lamps. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, C.; Møller, N.F. The Impact of EU’s Energy Labeling Policy: An Econometric Analysis of Increased Transparency in the Market for Cold Appliances in Denmark. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, M.; Schubert, R. How Do Different Designs of Energy Labels Influence Purchases of Household Appliances? A Field Study in Switzerland. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdziej, M.; Dudek, D.; Gajdzik, B.; Jaciow, M.; Lipowska, I.; Lipowski, M.; Tkaczyk, J.; Wolniak, R.; Wolny, R. Energy Efficiency Starts in the Mind: How Green Values and Awareness Drive Citizens’ Energy Transformation. Energies 2025, 18, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Nekmahmud, M. Purchase Behavior of Energy-Efficient Appliances Contribute to Sustainable Energy Consumption in Developing Country: Moral Norms Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 2022, 15, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.P.; Meier, A. Measurements of Whole-House Standby Power Consumption in California Homes. Energy 2002, 27, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgett, J.M. Fixing the American Energy Leak: The Effectiveness of a Whole-House Switch for Reducing Standby Power Loss in U.S. Residences. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.M.; Liao, J.; Stankovic, L.; Stankovic, V. Understanding Usage Patterns of Electric Kettle and Energy Saving Potential. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Hirzel, S.; Rohde, C.; Gebele, M.; Lopes, C.; Olsson, E.; Barkhausen, R. Electric Kettles: An Assessment of Energy-Saving Potentials for Policy Making in the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqui, A.; Sergici, S. Household Response to Dynamic Pricing of Electricity: A Survey of 15 Experiments. J. Regul. Econ. 2010, 38, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussein, S.N.B.; Barzamini, R.; Ebrahimi, M.R.; Farahani, S.S.S.; Arabian, M.; Aliyu, A.M.; Sohani, B. Revolutionizing Demand Response Management: Empowering Consumers through Power Aggregator and Right of Flexibility. Energies 2024, 17, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Cutler, D.; Ardani, K.; Margolis, R. Solar plus: Optimization of Distributed Solar PV through Battery Storage and Dispatchable Load in Residential Buildings. Appl. Energy 2018, 213, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Chen, Q.; Xu, H.; Xu, Q. A Bi-Level Demand Response Framework Based on Customer Directrix Load for Power Systems with High Renewable Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.L.M.; Hooper, R.J.; Gnoth, D.; Chase, J.G. Residential Electricity Demand Modelling: Validation of a Behavioural Agent-Based Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakins, J.; Power, B.; Ryan, G.; Strömberg, H.; Diamond, L. Who Saves Energy and Why? Analysing Diverse Behaviours in 27 European Countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 121, 103922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasmanaki, E.; Galatsidas, S.; Tsantopoulos, G. Developing a Typology Based on Energy Practices and Environmental Attitudes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.C.; Jian, I.Y.; Chi, H.L.; Yang, D.; Chan, E.H.W. Are You an Energy Saver at Home? The Personality Insights of Household Energy Conservation Behaviors Based on Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żywiołek, J.; Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Khan, M.A.; Sharif, A. Trust in Renewable Energy as Part of Energy-Saving Knowledge. Energies 2022, 15, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.A.; Hirani, T.; Arora, V.; Kakkar, S. Predictive Analytics for Personalized Debt Management: Leveraging Machine Learning to Provide Actionable Financial Advice. FinTech Sustain. Innov. 2025, 1, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Malesios, C.; Poulou, D. Electricity Curtailment Behaviors in Greek Households: Different Behaviors. Different Predictors. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umit, R.; Poortinga, W.; Jokinen, P.; Pohjolainen, P. The Role of Income in Energy Efficiency and Curtailment Behaviours: Findings from 22 European Countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 53, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardianou, E. Estimating Energy Conservation Patterns of Greek Households. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 3778–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. The Socio-Demographic and Psychological Predictors of Residential Energy Consumption: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2015, 8, 573–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardazzi, R.; Pazienza, M.G. Switch off the Light, Please! Energy Use, Aging Population and Consumption Habits. Energy Econ. 2017, 65, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Bongers, C.; McBain, B.; Rey-Lescure, O.; de Dear, R.; Capon, A.; Lenzen, M.; Jay, O. The Potential for Indoor Fans to Change Air Conditioning Use While Maintaining Human Thermal Comfort during Hot Weather: An Analysis of Energy Demand and Associated Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e301–e309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, T.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H. Extending Air Temperature Setpoints: Simulated Energy Savings and Design Considerations for New and Retrofit Buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 88, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassola, F.; Morgado, L.; Coelho, A.; Paredes, H.; Barbosa, A.; Tavares, H.; Soares, F. Using Virtual Choreographies to Identify Office Users’ Behaviors to Target Behavior Change Based on Their Potential to Impact Energy Consumption. Energies 2022, 15, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutule, A.; Domingues, M.; Ulloa-Vásquez, F.; Carrizo, D.; García-Santander, L.; Dumitrescu, A.M.; Issicaba, D.; Melo, L. Implementing Smart City Technologies to Inspire Change in Consumer Energy Behaviour. Energies 2021, 14, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, S.; Marden, S.; Arteaga, S.S.; Grossman, L.; Keselman, A.; Le, P.-T.; Masterson Creber, R.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Schnall, R.; Tabor, D.; et al. Behavioral Interventions Using Consumer Information Technology as Tools to Advance Health Equity. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Atkinson, B.; Garbesi, K.; Page, E.; Rubinstein, F. Lighting Controls in Commercial Buildings. LEUKOS 2012, 8, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.-H.; Keumala, N.; Ghafar, N.A. Energy Saving Potential and Visual Comfort of Task Light Usage for Offices in Malaysia. Energy Build. 2017, 147, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.-C.; Blomsterberg, Å. Energy Saving Potential and Strategies for Electric Lighting in Future North European. Low Energy Office Buildings: A Literature Review. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daminov, I.; Rigo-Mariani, R.; Caire, R.; Prokhorov, A.; Alvarez-Hérault, M.C. Demand Response Coupled with Dynamic Thermal Rating for Increased Transformer Reserve and Lifetime. Energies 2021, 14, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Wu, Q.; Wang, B. A Cluster-Based Baseline Load Calculation Approach for Individual Industrial and Commercial Customer. Energies 2019, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Intriago, V.B.; Rezabala-Cedeño, D.D.; Vera-Cevallos, W.L. LED Lights and Their Impact on Energy Savings in a Residential Environment. Int. J. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2024, 7, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganandran, G.S.B.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Ong, H.C.; Rismanchi, B.; Chong, W.T. Cost-Benefit Analysis and Emission Reduction of Energy Efficient Lighting at the Universiti Tenaga Nasional. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 745894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic Self-Consumption in Buildings: A Review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, V.; Marique, A.F.; Udalov, V. A Conceptual Framework to Understand Households’ Energy Consumption. Energies 2019, 12, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etongo, D.; Naidu, H. Determinants of Household Adoption of Solar Energy Technology in Seychelles in a Context of 100% Access to Electricity. Discov. Sustain. 2022, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.; Managi, S. Household Energy-Saving Behavior. Its Consumption. and Life Satisfaction in 37 Countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Le, B.N.; Pervan, S.; Vu, T.D.; Nguyen, T.M.N. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Energy Curtailment Behavior and Purchases of Energy-Efficient Appliances. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2026, 88, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.; Sugeta, H. Efficiency Investment and Curtailment Action. Environ Resour. Econ. 2022, 83, 759–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewale, A.; Mokhade, A.; Funde, N.; Bokde, N.D. An Overview of Demand Response in Smart Grid and Optimization Techniques for Efficient Residential Appliance Scheduling Problem. Energies 2020, 13, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B.F.; Schleich, J. Why Don’t Households See the Light?: Explaining the Diffusion of Compact Fluorescent Lamps. Resour. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardmeier, M.; Berthold, A.; Siegrist, M. Factors Influencing People’s Willingness to Shift Their Electricity Consumption. J. Consum. Policy 2024, 47, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Xu, X.; Cao, Z.; Mockus, A.; Shi, Q. Analysis of Social–Psychological Factors and Financial Incentives in Demand Response and Residential Energy Behavior. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 932134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badtke-Berkow, M.; Centore, M.; Mohlin, K.; Spiller, B. Making the Most of Time-Variant Electricity Pricing; Environmental Defense Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jessoe, K.; Rapson, D. Knowledge Is (Less) Power: Experimental Evidence from Residential Energy Use. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1417–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markotić, T.; Šljivac, D.; Marić, P.; Žnidarec, M. Sustainable Integration of Prosumers’ Battery Energy Storage Systems’ Optimal Operation with Reduction in Grid Losses. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A.; Pragidis, I.C.; Price, M.K. Toward an Understading of the Economics of Prosumers: Evidence from a Natural Filed Experiment; Nber Working Paper Series; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blasch, J.; Boogen, N.; Filippini, M.; Kumar, N. Explaining Electricity Demand and the Role of Energy and Investment Literacy on End-Use Efficiency of Swiss Households. Energy Econ. 2017, 68, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Labandeira, X.; Löschel, A. Pro-Environmental Households and Energy Efficiency in Spain. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 63, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Factors Influencing Energy-Saving Behavior of Urban Households in Jiangsu Province. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X. The Urban Renewable Energy Transition: Impact Assessment and Transmission Mechanisms of Climate Policy Uncertainty. Energies 2025, 18, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N.; Brandt, N. Determinants of Households’ Investment in Energy Efficiency and Renewables. In OECD Economics Department Working Papers; No. 1165; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromada, A.; Trębska, P. Energy Efficiency—Case Study for Households in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiński, P.; Hadyński, J.; Lira, J.; Rosa, A. Regional Diversification of Electricity Consumption in Rural Areas of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanelyte, D.; Radziukyniene, N.; Radziukynas, V. Overview of Demand-Response Services: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribó-Pérez, D.; Larrosa-López, L.; Pecondón-Tricas, D.; Alcázar-Ortega, M. A Critical Review of Demand Response Products as Resource for Ancillary Services: International Experience and Policy Recommendations. Energies 2021, 14, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišljenović, N.; Žnidarec, M.; Knežević, G.; Šljivac, D.; Sumper, A. A Review of Energy Management Systems and Organizational Structures of Prosumers. Energies 2023, 16, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, J.; Kossowski, T. Comparison of Values of Pearson’s and Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients on the Same Sets of Data. Quaest. Geogr. 2011, 30, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska, L.; Śmiech, S. Shadow of Single-Family Homes: Analysis of the Determinants of Polish Households’ Energy-Related CO2 Emissions. Energy Build. 2022, 277, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angowski, M.; Kijek, T.; Lipowski, M.; Bondos, I. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Photovoltaic Systems in Rural Areas of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B.; Schleich, J. Household Transitions to Energy Efficient Lighting. Energy Econ. 2014, 46, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. An Empirical Analysis of Green Electricity Adoption among Residential Consumers in Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, E.; Wiśniewski, J.W. Sustainable Energy Consumption—Empirical Evidence of a Household in Poland. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCI1: I turn off unnecessary lighting | 0.036 | 0.728 | 0.467 |

| LCUI1: I use an energy-saving light bulb | 0.048 | 0.962 | 0.337 |

| CII1: I buy energy-efficient equipment | 0.052 | 1.048 | 0.295 |

| HCI2: reduce the number of bulbs in use | 0.212 | 4.341 | 0.000 |

| HCI3: I limit the use of electric stoves, fans, air conditioning, etc. | 0.145 | 2.930 | 0.004 |

| LCUI2: I turn off devices, e.g., electronics, completely so that they are not in standby mode | 0.058 | 1.151 | 0.250 |

| HCI4: I use the side lights/lighting more often than the main one | 0.142 | 2.857 | 0.004 |

| HCI5: I boil the right amount of water in an electric kettle (not too much, not too little) | 0.178 | 3.604 | 0.000 |

| TSI1: I have two tariffs: night and day | −0.025 | −0.498 | 0.619 |

| SPI1: I use alternative energy sources, e.g., I have photovoltaic panels | −0.030 | −0.590 | 0.555 |

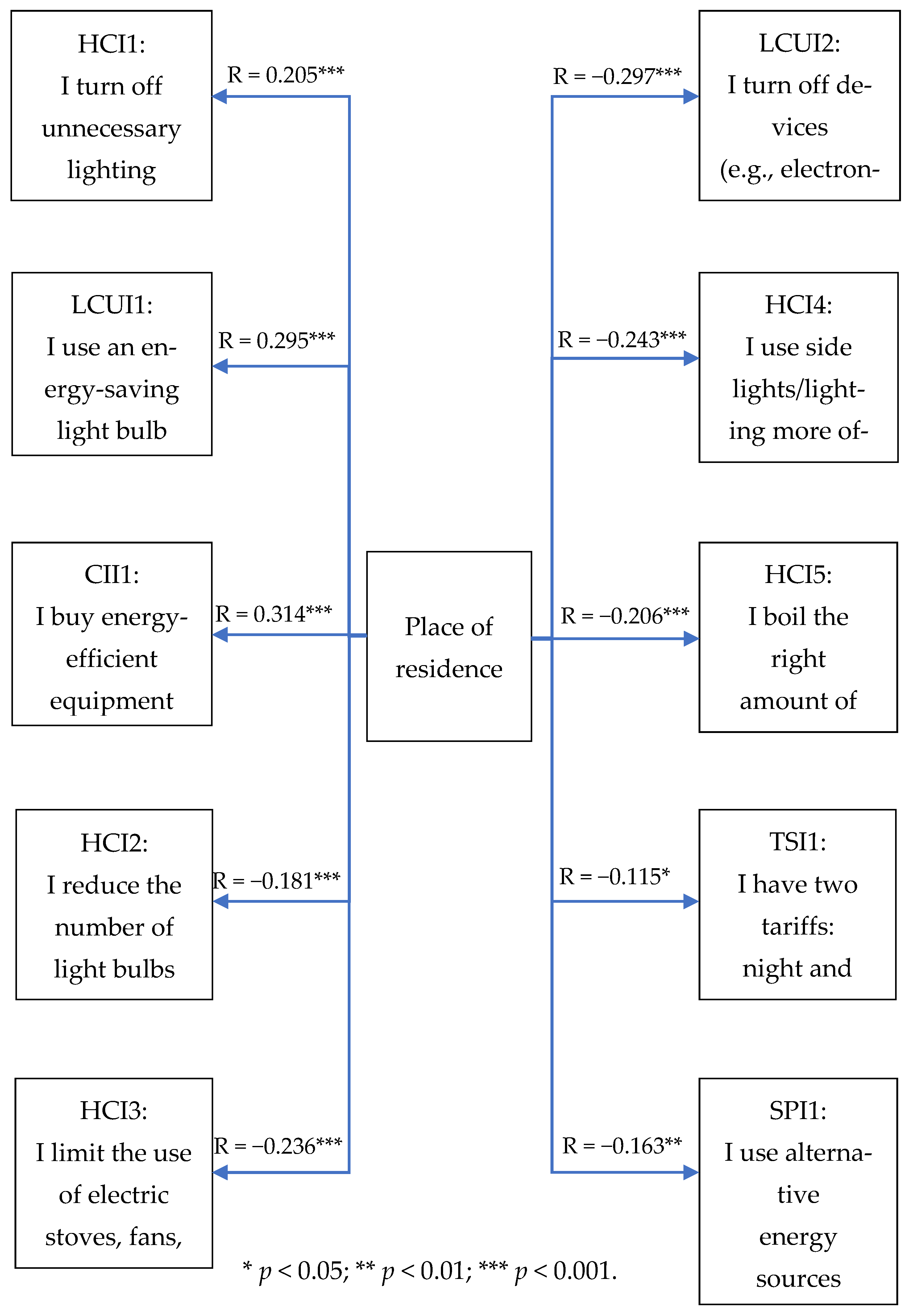

| Factors | R | t(n− 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCI1: I turn off unnecessary lighting | 0.205 | 4.177 | 0.0000 |

| LCUI1: I use an energy-saving light bulb | 0.295 | 6.167 | 0.0000 |

| CII1: I buy energy-efficient equipment | 0.314 | 6.598 | 0.0000 |

| HCI2: reduce the number of light bulbs | −0.181 | −3.678 | 0.0003 |

| HCI3: I limit the use of electric stoves, fans, air conditioning, etc. | −0.236 | −4.860 | 0.0000 |

| LCUI2: I turn off devices, e.g., electronics, completely so that they are not in standby mode | −0.297 | −6.204 | 0.0000 |

| HCI4: I use the side lights/lighting more often than the main one | −0.243 | −5.005 | 0.0000 |

| HCI5: I boil the right amount of water in an electric kettle (not too much. not too little) | −0.206 | −4.212 | 0.0000 |

| TSI1: I have two tariffs: night and day | −0.115 | −2.319 | 0.0209 |

| SPI1: I use alternative energy sources, e.g., I have photovoltaic panels | −0.163 | −3.300 | 0.0011 |

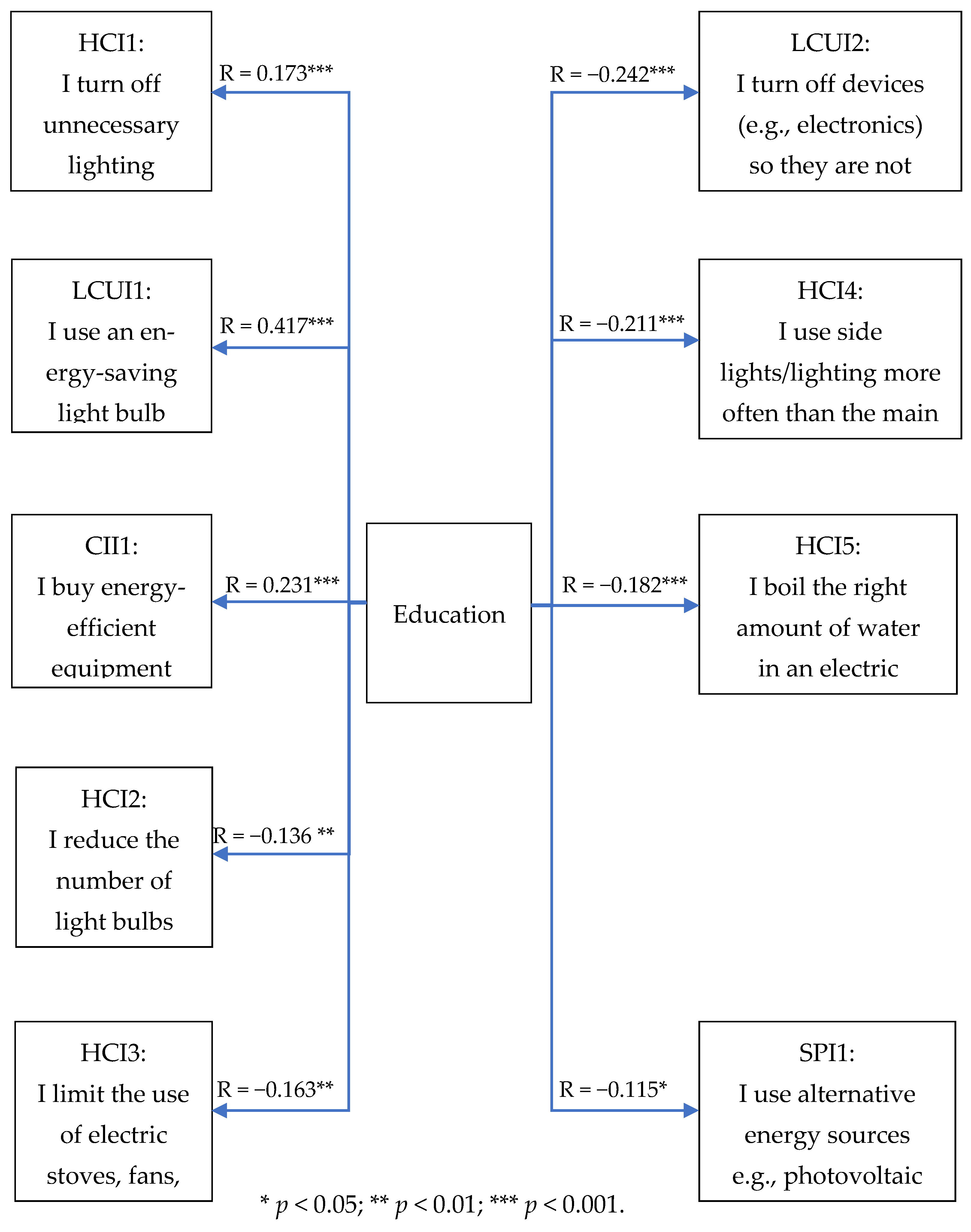

| Factors | R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCI1: I turn off unnecessary lighting | 0.173 | 3.516 | 0.000 |

| LCUI1: I use an energy-saving light bulb | 0.417 | 9.176 | 0.000 |

| CII1: I buy energy-efficient equipment | 0.231 | 4.743 | 0.000 |

| HCI2: reduce the number of light bulbs | −0.136 | −2.734 | 0.007 |

| HCI3: I limit the use of electric stoves, fans, air conditioning, etc. | −0.163 | −3.303 | 0.001 |

| LCUI2: I turn off devices, e.g., electronics, completely so that they are not in standby mode | −0.242 | −4.989 | 0.000 |

| HCI4: I use the side lights/lighting more often than the main one | −0.211 | −4.311 | 0.000 |

| HCI5: I boil the right amount of water in an electric kettle (not too much, not too little) | −0.182 | −3.702 | 0.000 |

| TSI1: I have two tariffs: night and day | −0.073 | −1.458 | 0.146 |

| SPI1: I use alternative energy sources, e.g., I have photovoltaic panels | −0.115 | −2.319 | 0.021 |

| Factors | R | t(n − 2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

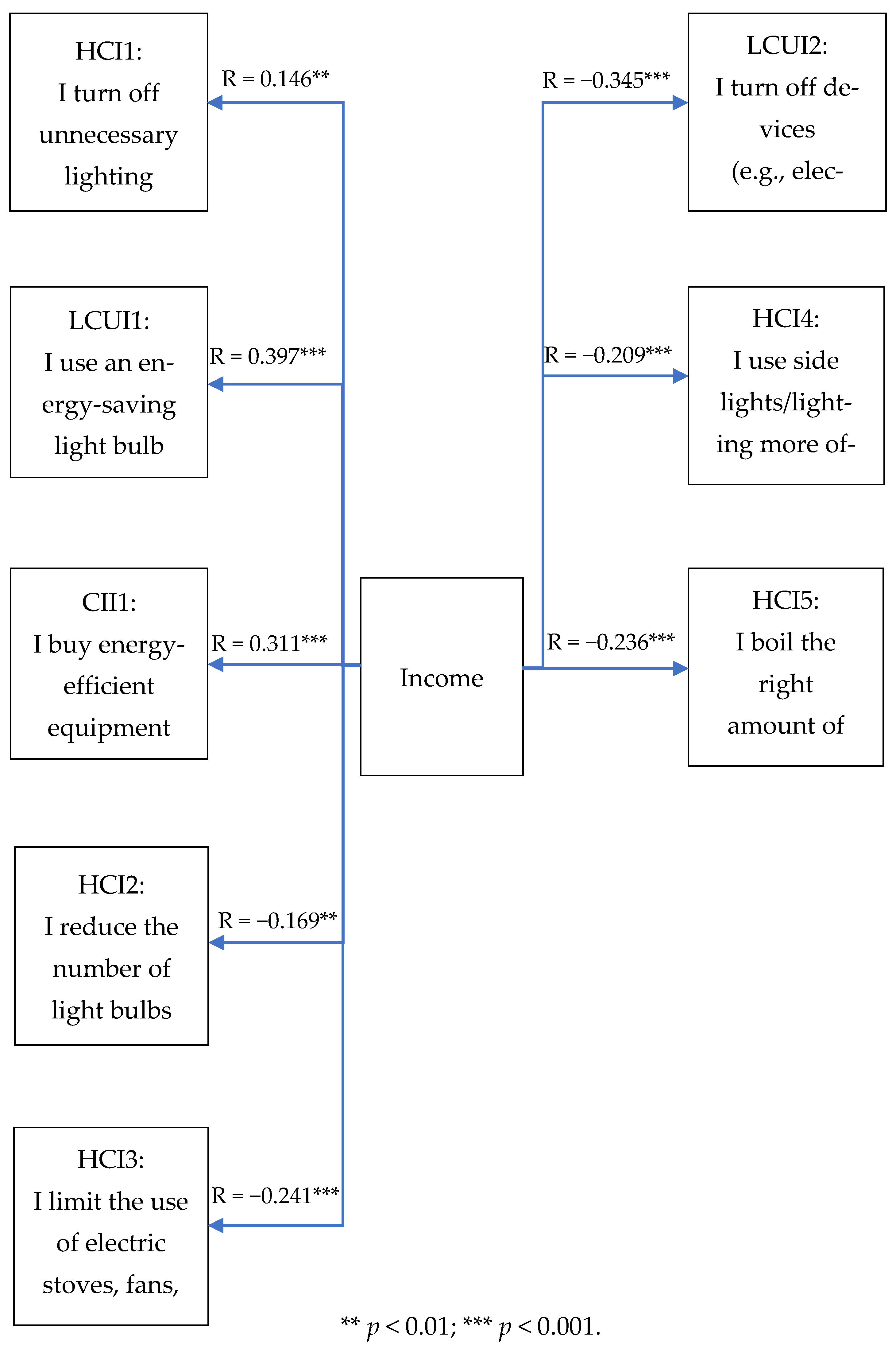

| HCI1: I turn off unnecessary lighting | 0.146 | 2.943 | 0.003 |

| LCUI1: I use an energy-saving light bulb | 0.397 | 8.647 | 0.000 |

| CII1: I buy energy-efficient equipment | 0.311 | 6.525 | 0.000 |

| HCI2: reduce the number of light bulbs | −0.169 | −3.421 | 0.001 |

| HCI3: I limit the use of electric stoves, fans, air conditioning, etc. | −0.241 | −4.954 | 0.000 |

| LCUI2: I turn off devices, e.g., electronics, completely so that they are not in standby mode | −0.345 | −7.342 | 0.000 |

| HCI4: I use the side lights/lighting more often than the main one | −0.209 | −4.265 | 0.000 |

| HCI5: I boil the right amount of water in an electric kettle (not too much, not too little) | −0.236 | −4.860 | 0.000 |

| TSI1: I have two tariffs: night and day | −0.066 | −1.324 | 0.186 |

| SPI1: I use alternative energy sources. e.g., I have photovoltaic panels | −0.010 | −0.193 | 0.847 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peszko, A.; Parkitna, A.; Ucieklak-Jeż, P.; Urbańska, K. Between Habit and Investment: Managing Residential Energy Saving Strategies in Polish Households. Energies 2026, 19, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010191

Peszko A, Parkitna A, Ucieklak-Jeż P, Urbańska K. Between Habit and Investment: Managing Residential Energy Saving Strategies in Polish Households. Energies. 2026; 19(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010191

Chicago/Turabian StylePeszko, Agnieszka, Agnieszka Parkitna, Paulina Ucieklak-Jeż, and Kamila Urbańska. 2026. "Between Habit and Investment: Managing Residential Energy Saving Strategies in Polish Households" Energies 19, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010191

APA StylePeszko, A., Parkitna, A., Ucieklak-Jeż, P., & Urbańska, K. (2026). Between Habit and Investment: Managing Residential Energy Saving Strategies in Polish Households. Energies, 19(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010191