Abstract

Depressurization combined with thermal stimulation based on injection-production well patterns is considered promising for gas hydrate development. Nevertheless, its direct application to Shenhu challenging hydrates may be problematic due to the presence of low reservoir permeability and permeable boundaries. The present study proposes to improve the development potential of Shenhu hydrate by reservoir reconstruction, including boundary sealing and reservoir fracturing, and numerically investigates the production performance. The results showed that water intrusion, hot loss, and gas leakage can be effectively addressed by boundary sealing. Nevertheless, it cannot enhance productivity as thermal decomposition gas accumulated around the injection well. Conversely, reservoir fracturing can significantly improve extraction efficiency as substantial amounts of hydrates dissociate along the fractures, and the gas can be well recovered through the fractures. However, reservoir fracturing was not conducive to water control and energy utilization as it induced more severe water flooding and gas leakage. Under the synergistic effect of the two, there was no methane leakage, and the gas production rate increased with increasing fracture conductivity, while the gas-to-water ratio and energy ratio presented the opposite trend. To obtain a favorable production performance, a fracture with a conductivity of 1–10 D·cm was recommended. Therefore, the combination of boundary sealing and reservoir fracturing makes it feasible for safe and efficient extraction of offshore challenging hydrate under the injection-production mode.

1. Introduction

Natural gas hydrate (NGH) is a crystalline compound in which guest gas molecules (mainly methane) are encapsulated in a cage of water molecules [1]. Due to the wide distribution and huge reserves, with a carbon content of about 1/3 of the global total [2,3], NGH is widely recognized as a promising new clean energy resource that will play a significant role in future energy supply [4].

At present, Japan, China, the European Union, as well as other countries and regions, have been vigorously advancing the commercial development and utilization of hydrates [5]. However, more than 97% of NGH is hosted in deep-sea shallow sediments, facing enormous challenges for development due to the complex marine environment, unique occurrence conditions, and a range of potential geo-environmental issues [6]. The Shenhu Area of the South China Sea is currently one of the most active NGH trial production sites in the world, where NGH is endowed in low-permeability clayey silty sediments without impermeable boundaries [7,8,9]. According to the classification of hydrates by Moridis et al. (2011), this falls under the category of challenging hydrates due to the great extraction difficulty [10]. Furthermore, the two rounds of trial production of Shenhu hydrates have proven the feasibility of recovering gas from this deposit [11,12]. Especially in the second trial production, horizontal wells were used for productivity enhancement, with 86.14 × 104 m3 of gas produced within 30 days [12]. Nevertheless, it is still far below the accepted commercial productivity of 5–50 m3/d [13,14]. Consequently, enhancing the productivity of challenging hydrates has become a hot topic.

The feasible NGH extraction methods include depressurization, thermal stimulation, gas displacement (mainly CO2), and inhibitor injection [15]. Among them, the combination of depressurization and thermal stimulation is generally considered highly promising as it can provide sufficient heat for hydrate decomposition [16,17,18,19]. Particularly, the injection-production mode based on a multi-well shows tantalizing potential because of the efficient mass and heat transfer and has been proposed for the commercial development of NGH by Japan [20]. However, this development mode may be problematic if applied directly to challenging hydrates. The most pronounced distinction is that the permeability of the clayey silty deposits in the Shenhu Area (mostly less than 10 mD) is much lower than the sandy deposits in the Nankai Trough (hundreds to thousands of mD), which is unfavorable for temperature–pressure transfer and fluid flow. Li et al. (2010) and Su et al. (2012) found that thermal stimulation was confined to a limited area [21,22]. Feng et al. (2015) and Jin et al. (2016) revealed that the low permeability cuts off the inter-well hydraulic connection, resulting in the thermal decomposition gas being hard to recover [23,24]. Additionally, the absence of an impermeable boundary results in significant heat fluid losses, which are highly detrimental to energy utilization [25]. Most importantly, thermal decomposition gas tends to escape to the cover layers driven by the high injection pressure, significantly increasing the geo-environmental risk [26]. These issues need to be well addressed in challenging hydrate development under the injection-production mode.

Reservoir fracturing (RF) is an important strategy for unconventional oil and gas development [27,28,29]. Because of this, RF has been proposed to improve the injection-production performance of challenging hydrates. Furthermore, the fracability of hydrate deposits and the stimulation potential have been initially evaluated [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Ju et al. (2020) found that RF improved the hot water wave area, thereby facilitating hydrate decomposition [34]. Zhong et al. (2011, 2022) discovered that RF greatly increased the mass and heat transfer between injection and production wells, and was expected to reach commercial productivity [13,37]. However, the hot water loss and gas leakage induced by the open boundary were not considered. According to our previous assessment, uncontrolled hydrate decomposition caused by RF can significantly increase the risk of gas leakage [38]. Against this background, the current study attempts to address the negative effects induced by RF and permeable boundaries.

The permeable cover layer of the NGH deposits is similar to the boundary conditions of gas reservoirs containing edge or bottom water. The primary solution technique is boundary sealing (BS), that is, the use of sealing and plugging materials (e.g., cement) to create impermeable artificial barriers that prevent water intrusion. Yue et al. (2012) developed a flow model for horizontal wells in bottom-water-driven reservoirs with impermeable barriers, demonstrating that the barrier can enhance the critical rate and delay water breakthrough [39]. Liu et al. (2023) constructed an improved artificial barrier by injecting oil-soluble resin as the selective water shut-off agent during the crack generation phase [40]. Bai et al. (2024) reviewed the macroscopic effects and microscopic mechanisms of gel agents during the “injection, migration, plugging, and stabilization” process [41]. Similarly, this technology can be integrated into hydrate development. Our previous research has demonstrated that the hydraulic connection between the reservoir and caprock can be severed by the BS, thereby addressing issues including injected hot loss, boundary water intrusion, and methane leakage [42]. However, the low reservoir permeability hindered the migration of thermal decomposition gas to production wells, resulting in no contribution to productivity during the first three years of hot water injection. Given all the considerations above, the combination of BS and RF may be a novel and promising development mode for offshore challenging hydrates.

This study intends to improve the development potential of challenging hydrates under the injection-production mode through reservoir reconstruction, including BS and RF. The production performance, including NGH decomposition, gas–water production, energy utilization, as well as hot loss and gas leakage, was numerically analyzed, with Shenhu challenging hydrates as the geological background. Furthermore, the synergistic effects between BS and RF were thoroughly evaluated. The novel findings of this study could provide valuable insights for challenging hydrate extraction.

2. Modeling

2.1. Development Plan

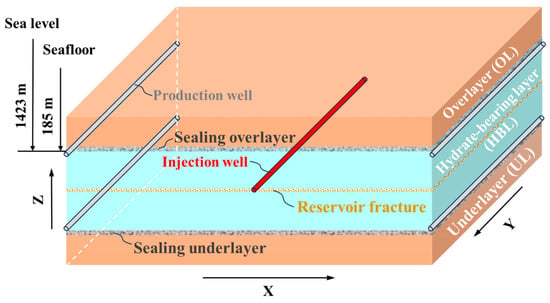

The development plan is designed based on the geological characteristics of hydrates at the Shenhu SH2 site, as shown in Figure 1. Geological surveys indicate that the hydrate deposits at the Shenhu SH2 site belong to Class 2 [43,44]. Furthermore, both the overlayer (OL) and underlayer (UL) are permeable with the same permeability as the hydrate-bearing layer (HBL) of 10 mD. Consequently, this represents a classic challenging hydrate characterized by the absence of impermeable boundaries and low reservoir permeability [10]. In the development plan, a five-spot horizontal well pattern with a rectangular distribution was adopted, including one hot water injection well located in the middle of the reservoir and four production wells distributed at the top and bottom of the HBL. Previous studies have demonstrated that this type of well deployment is efficient for gas recovery [45,46]. One feasible reservoir reconstruction scheme is given as follows: firstly, a high-conductivity artificial fracture is created in the middle of the HBL by RF through the injection well; then, impermeable artificial barriers are formed at the top and bottom of the HBL by injecting sealing materials (e.g., cement) through the production wells, thereby sealing open boundaries.

Figure 1.

Proposed development plan for the NGH reservoir at the Shenhu SH2 site, wherein the injection and production horizontal wells were arranged along the X-axis; all horizontal sections were drilled along the Y-axis; and the Z-axis represents the vertical direction.

2.2. Geometric Modeling

The HBL thickness at Shenhu SH2 is reported to be 0–44 m [43], and 40 m is taken here. Several researchers have demonstrated that a 30 m thick cover layer is sufficient for the simulation of reservoir temperature–pressure evolution [47,48,49]. While considering the permeable characteristics in this case, the thickness of the OL and UL was set to be 80 m. The horizontal well spacing between the injection and production wells was 100 m, assuming that the reservoir was homogeneous along the Y-axis, and thus only one unit length of the horizontal well section was modelled. As a result, the model size is 200 m (X) × 1 m (Y) × 200 m (Z).

The fracture width and half-length were set as 0.01 and 1 m, with a conductivity of 1–50 D·cm. The 1 m-thick layer at the top and bottom of the HBL was modeled as the barrier, and the permeability was set as 0 to simulate the sealing effect. In the X direction, the grids were refined from 1 m to 0.2 m toward the wellbore, resulting in 203 subdivided meshes. In the Y direction, only one grid was subdivided. In the Z-direction, the grids were refined from the model boundary toward the fracture to 0.01 m, resulting in 106 subdivided meshes. As a result, the total number of meshes is 21,518.

2.3. Simulation Code

Tough + Hydrate (T + H, v1.0), developed by Lawrence Berkeley, was used here because of its reliability in describing phase transitions, heat exchange, and fluid flow in complex media. Furthermore, its accuracy has been fully tested on both experimental and mine scales [50,51,52], which ensures the accuracy of the simulation results.

2.4. Initial and Boundary Conditions

Reservoir pressure and temperature were initialized using hydrostatic pressure and geothermal gradients due to the permeable cover layers. Dirichlet boundary conditions were imposed at the top and bottom model boundaries, as sufficient cover layers have been considered. Model parameters are presented in Table 1. Notably, to ensure the reliability of simulation results, the selected reservoir parameters in the model, including porosity, permeability, and hydrate saturation, as well as the properties of the OL and UL, were consistent with the real geological conditions of Shenhu SH2 Site.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

2.5. Simulation Scheme

In our simulations, the production behaviors under various BS cases including sealing OL (BSO), UL (BSU), or both (BSOU) were investigated; subsequently, various RF cases were analyzed, including Cf of 1 (RF1), 5 (RF5), 10 (RF10), and 50 (RF50) D·cm, respectively; and finally, the synergistic effect between RF and BS was evaluated. Notably, the unreconstructed reservoir serves as a base case for comparative analyses. Consequently, the final simulation scheme in Table 2 was developed.

Table 2.

Simulation scheme.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Production Performance Under BS

3.1.1. Reservoir Physical Field Distribution

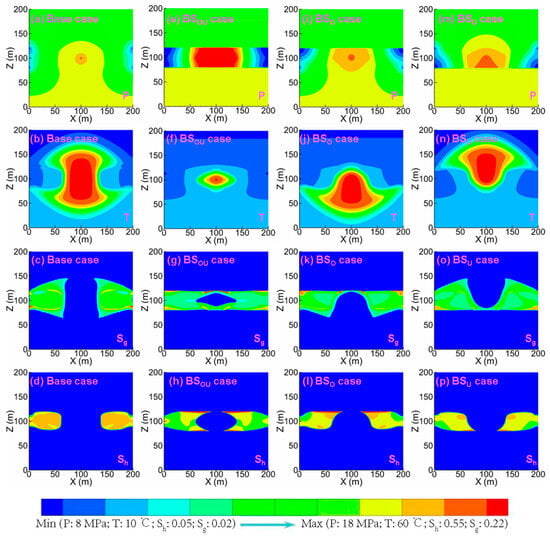

The reservoir physical field distribution at 1800 days in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Reservoir pressure (P), temperature (T), hydrate saturation (Sh), and gas saturation (Sg) in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases.

The high injection pressure extended to the cover layer in the base case (Figure 2a), and considerable injected hot water flowed into the OL and UL (Figure 2b). Furthermore, the propagation of low production pressures was suppressed, similar to the boundary water intrusion phenomenon in the development of conventional gas reservoirs containing edge or bottom water. This interlayer permeability difference is detrimental to hydrate dissociation and gas recovery. It can be observed that the thermal decomposition gas escaped into cover layers (Figure 2c) and a significant amount of NGH was reserved (Figure 2d). In the BSOU case, the high injection pressure can be successfully maintained in the HBL, and the low production pressure was also efficiently propagated, creating a satisfactory pressure gradient between the injection and production wells (Figure 2e). In addition, there was no hot water loss (Figure 2f) and gas escape (Figure 2g). Regrettably, gas was hard to transport to the production wells due to the low reservoir permeability. This causes a large amount of gas that is trapped in the vicinity of the injection wells (Figure 2g), thus inhibiting the injection and diffusion of hot water (Figure 2f). As a result, the NGH decomposition efficiency (Figure 2h) was lower relative to the base case. In the BSO case, high injection pressure maintenance failed (Figure 2i). The mechanism is that the injected hot water penetrated through the bottom of the HBL and migrated downward into the permeable UL, causing partial thermal decomposition gas to escape into the UL (Figure 2j–l). In the BSU case, high injection pressure primarily propagated towards the permeable OL (Figure 2m). This results in hot water breaking through the top of the HBL and thermal decomposition gas escaping into the permeable OL (Figure 2n–p). Thus, partial sealing does not fully prevent hot water loss and gas escape.

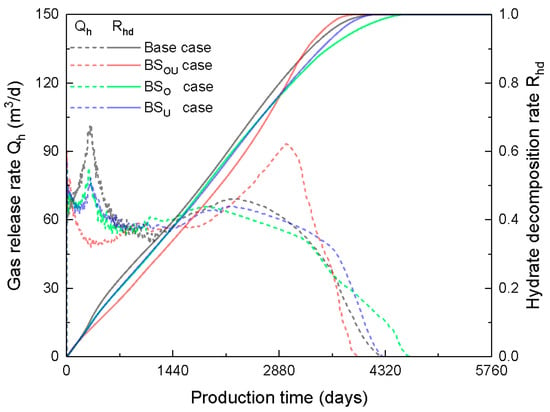

3.1.2. Hydrate Dissociation Behavior

The variation of NGH dissociation rate (Qh, gas released volume per day) and NGH decomposition ratio (Rhd, defined by the ratio of decomposed hydrate mass to the in situ hydrate mass) in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases is shown in Figure 3. The variation of Qh in the base case presents four different phases. In the first phase (~330 days), Qh increased greatly with injected hot water spreading and low production pressure propagation and peaked at 113 m3/d. Subsequently (~1000 days), Qh decreased sharply, with a minimum value of 50 m3/d. Mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon include a significant amount of hot water leaked into UL and OL, the slower and slower forward advance of the thermal decomposition leading edge, as well as the boundary water intrusion that inhibits the propagation of low production pressures. In the third phase (~2340 days), inter-well interaction gradually intensified with NGH decomposition, and therefore Qh increased slowly and peaked at 71 m3/d. After that, Qh dropped sharply as there was less and less hydrate remaining in the reservoir.

Figure 3.

Variation of Qh and Vhd in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases.

Unlike the base case, the initial Qh in the BSOU case decreased rapidly with a minimum value of 45 m3/d at 327 days. This is because the gas accumulated around the injection well suppressed the injection and diffusion of hot water. Then, a piston-like displacement gradually formed under a stable inter-well pressure gradient, and thus Qh stabilized at 55 m3/d. Afterward, Qh began to rise at about 1800 days and peaked at 98 m3/d at 3090 days. This is because the gas is recovered by the production wells, which promotes the injection and diffusion of hot water, thus increasing the hydrate decomposition efficiency. After that, Qh decayed dramatically as the inter-well NGH was nearly completely decomposed. The variation of Qh in BSO and BSU cases is similar to the base case. In addition, the NGH decomposition cycle Th for the base, BSU, and BSO cases is 4130–4530 days, suggesting that sealing the UL or OL alone has a limited effect on hydrate decomposition. Nevertheless, simultaneously sealing both of them decreased the initial Qh, but the mid- and post-Qh were more substantial, resulting in the shortest Th of 3800 days.

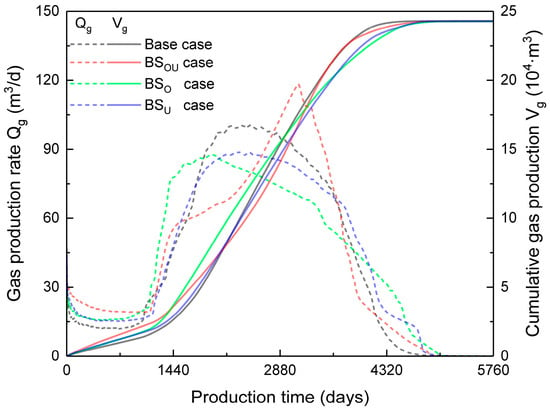

3.1.3. Gas Production Behavior

The variation of gas production rate Qg and cumulative gas production Vg in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Variation of Qg and Vg in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases.

As shown in Figure 4, the variation of Qg presented three phases in all cases. Firstly, there was a low gas production phase, where Qg stabilized after a slight decrease, and the produced gas was contributed by depressurized decomposed gas. Furthermore, Qg in the BSOU case is the maximum, about 20 m3/d, followed by those in BSO and BSU cases, about 15 m3/d, and the minimum is 12 m3/d in the base case. The second phase was entered at approximately 1000 days, where Qg increased significantly as more and more thermal decomposition gas was recovered by production wells. Affected by the evolutions of Qh, the peak values of Qg in the BSOU case are the maximum (118 m3/d), followed by 100 m3/d in the base case, 88 m3/d in the BSO case, and 86 m3/d in the BSU case. Ultimately, there is a gas production depletion phase due to the insufficient gas supply. Additionally, the final Vg within 5760 days in all cases was consistent, and boundary conditions barely affected the gas recovery cycles Tg, as they were about 4700–4900 days.

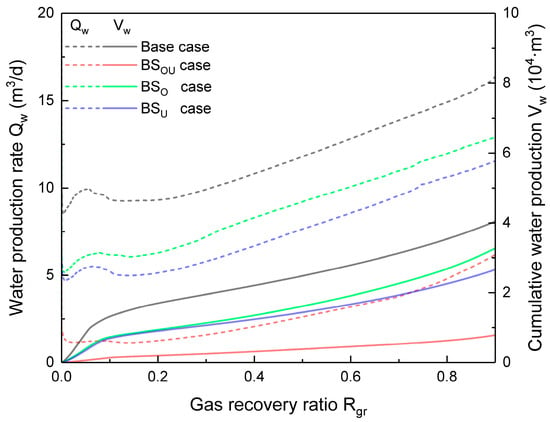

3.1.4. Water Production Behavior

Figure 5 shows the variation of water production rate Qw and cumulative water production Vw with gas recovery ratio Rgr (defined by the ratio of Vg to total gas available in the reservoir) in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases. It can be seen that Qw exhibits three phases in all cases, including an initial slight rise, followed by a brief decline, and another rapid rise. The mechanism is that more and more injected water was recovered by the production wells as inter-well interactions increased. This is similar to the water flooding phenomenon in water-driven reservoir development, since open boundaries could induce severe water intrusion. The Qw in the base case is the highest, followed by the BSO, BSU, and BSOU cases, respectively. Specifically, the Vw at Rgr of 0.7 (acceptable for water-driven development of China’s offshore low-permeability gas reservoirs) in the base case is 3.13 × 104 m3, which is 5.89, 1.38, and 1.61 times that of BSO, BSU, and BSOU cases, respectively. Consequently, boundary intrusion can be well addressed by simultaneously sealing the upper and lower boundaries, which is an effective means of water control.

Figure 5.

Variation of Qw and Vw in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases.

Figure 6 shows the variation of gas-to-water ratio Rgw (defined by the ratio of Vg to Vw) in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases. It can be seen that Rgw in the base case is the lowest (<5), and its change presents three stages of fall-rise-fall, which correspond to the initial stage of low gas and low water production, the middle stage of increasing water and gas production, and the later stage of low gas and high water production, respectively. Compared to the base, the evolution of Rgw in BSO and BSU cases is similar, and its enhancement is not significant. Encouragingly, Rgw in the BSOU case is satisfactory, reaching 32 at an Rgr of 0.7, 5.87, 4.25, and 3.63 times that of the base, BSO, and BSU cases, respectively. Therefore, gas–water production behavior can be improved by sealing OL and UL.

Figure 6.

Variation of Rgw in the base, BSOU, BSO, and BSU cases.

3.2. Injection-Production Performance Under Reservoir Fracturing

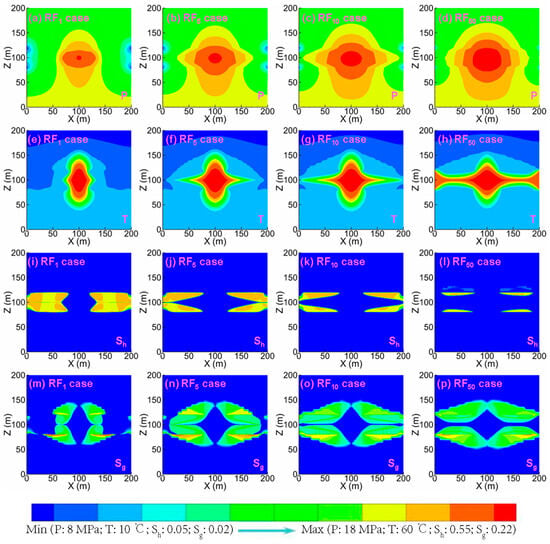

3.2.1. Reservoir Physical Field Distribution

Figure 7 shows the reservoir physical field distribution at 720 days in the RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases. It can be seen that as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, the high injection pressure propagates faster (Figure 7a–d) and a wider wave of hot water in the horizontal direction is observed (Figure 7e–h). This improves the reservoir heating efficiency, thus promoting hydrate decomposition (Figure 7i–l). Furthermore, more hydrate dissociates along the fracture surface as Cf increases, which leads to a shift in hydrate decomposition mode from piston-type to volumetric-type. However, increasing Cf could not avoid gas leakage (Figure 7m–p), which is consistent with previous studies. It should be specifically pointed out that the current model assumes a constant Cf value throughout the production process. In reality, given the weakly cemented nature of NGH deposits, fractures may buckle, become plugged with sand proppant, or interact with natural heterogeneities. This may impact long-term forecasts. Consequently, the variation pattern of Cf as well as its influence needs to be further investigated.

Figure 7.

Reservoir pressure (P), temperature (T), hydrate saturation (Sh), and gas saturation (Sg) in the RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

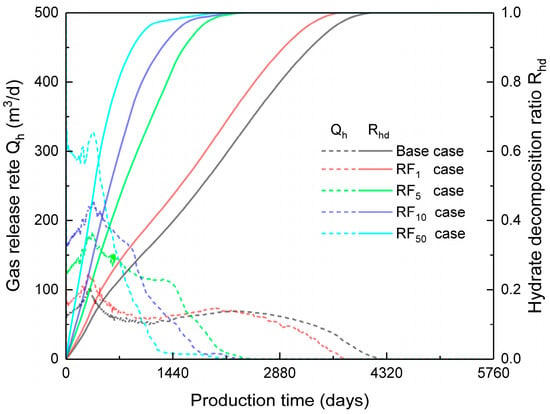

3.2.2. Hydrate Dissociation Behavior

Figure 8 shows the variation of Qh and Rhd in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases. As can be seen, the variation of Qh in the RF cases is similar to that in the base case. The difference is that the initial Qh increases with the increase in Cf. Specifically, the peak value increases from 130 to 317 m3/d as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, which is 1.16–2.83 times higher than that in the base case. The mechanism is that a greater Cf is more favorable for hot water migration, allowing more hydrate to dissociate along the fracture. Additionally, at greater Cf, the leading edge of hydrate decomposition moves away from the fracture faster, which leads to a higher post-peak Qh decay rate. The Th reduces from 3700 to 2170 days as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, a reduction of 430–1960 days compared to the base case. As a result, increasing Cf is helpful for hydrate decomposition.

Figure 8.

Variation of Qh and Vhd in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

3.2.3. Gas Production Behavior

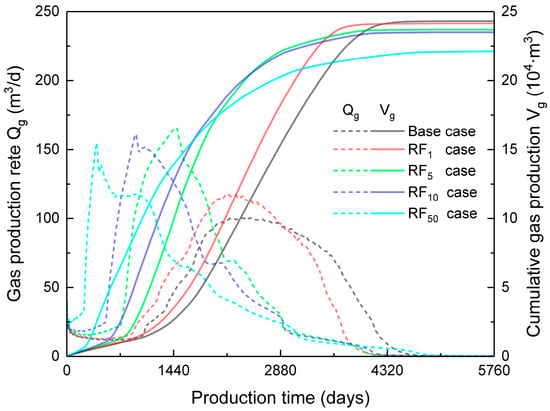

Figure 9 shows the variation of Qg and Vg in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

Figure 9.

Variation of Qg and Vg in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

With Cf increasing, the initial low productivity phase is greatly shortened, and the corresponding time for Qh to peak is earlier. Specifically, this time is shortened from 2160 days to 400 days as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, a reduction of 260–1790 days relative to the base case. The mechanism is that the gas flow rate inside the fracture is higher with a greater Cf, and therefore, thermal decomposition gas can be extracted more rapidly from production wells. However, the peak value of Qg does not always increase as Cf increases, with a maximum value of 161 m3/d occurring at Cf of 10 D·cm. This is attributed to the fact that increasing CF simultaneously increases the hot water injection rate, thereby reducing the gas-phase relative permeability in the fracture. Additionally, it is observed that the Vg within 5760 days decreases from 24.13 to 22.12 × 104 m3 as CF increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, a reduction of 0.18–2.18 × 104 m3 compared to the base case. This suggests that gas leakage occurs in the RF case and that the amount of leaked gas increases with increasing Cf. Thus, increasing Cf can substantially increase the gas recovery efficiency, but also induce more serious gas leakage.

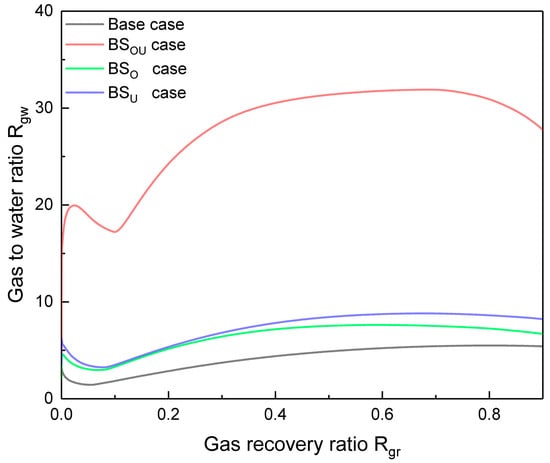

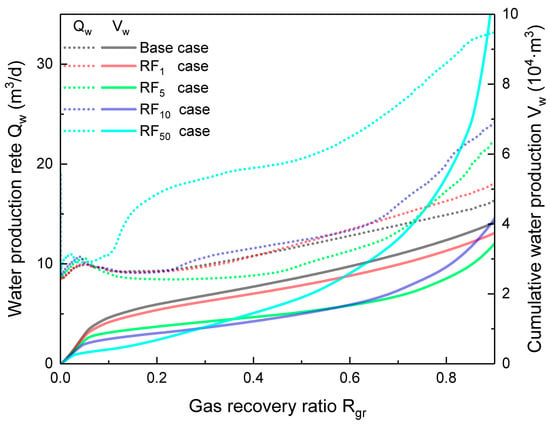

3.2.4. Water Production Behavior

Figure 10 shows the variation of Qw and Vw in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases. At the early production stage (Rgr < 0.1), the influence of Cf on Qw is not significant. Interestingly, Qw and Vw do not always increase with increasing Cf. Specifically, when Rgr is 0.7, Vw decreases from 2.84 to 1.94 × 104 m3 as Cf increases from 1 to 5 D·cm, a reduction of 0.29–1.19 × 104 m3 compared to the base case. In contrast, Vw increases from 1.94 to 3.60 as Cf increases from 5 to 50 D·cm, indicating that increasing Cf in this interval is more favorable for water production compared to gas production. Consequently, properly controlling the Cf value of 1–10 D·cm is conducive to water control.

Figure 10.

Variation of Qw and Vw in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

Figure 11 shows the variation of Rgw in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases. The Rgr corresponding to the peak value of Rgw reduced from 0.72 to 0.20 as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, a reduction of 0.08–0.60 relative to the base case. The reason is that increasing Cf can significantly improve Qg, but also induce premature water flooding. The Rgw at Rgr of 0.7 increases first and then decreases with increasing Cf, and the maximum value of 8.82 appears at CF of 5 D·cm, 1.61 times that in the base case. As a result, RF can improve the gas and water production behavior, but needs to control Cf reasonably.

Figure 11.

Variation of Rgw in the base, RF1, RF5, RF10, and RF50 cases.

3.3. Production Performance Under BS and RF

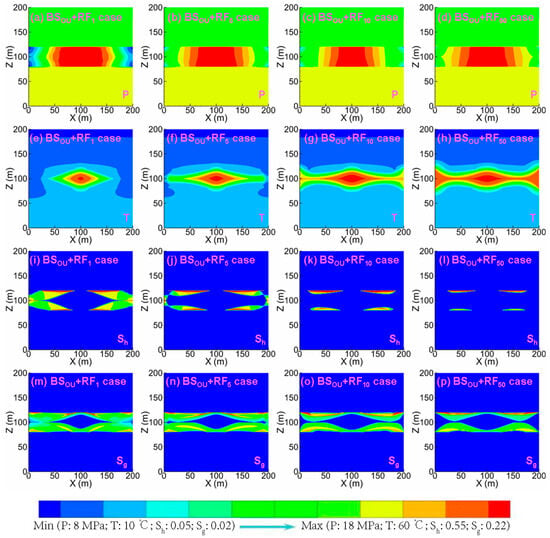

3.3.1. Reservoir Physical Field Distribution

Figure 12 shows the reservoir physical field distribution at 1800 days in the BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases. The high injection pressure only propagated in the HBL, and ideal pressure gradients between the injection and production wells were generated (Figure 12a–d). Similar to the RF cases in Figure 6, the hot water spread area increases as CF increases (Figure 12e–h), and therefore, more hydrates are decomposed along the fracture (Figure 12i–l). The difference is that there is no hot water loss (Figure 12e–h) and gas leakage (Figure 12i–l). As a result, BS can improve the utilization efficiency of hot water while effectively addressing gas leakage induced by RF.

Figure 12.

Reservoir pressure (P), temperature (T), hydrate saturation (Sh), and gas distribution (Sg) in the BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases.

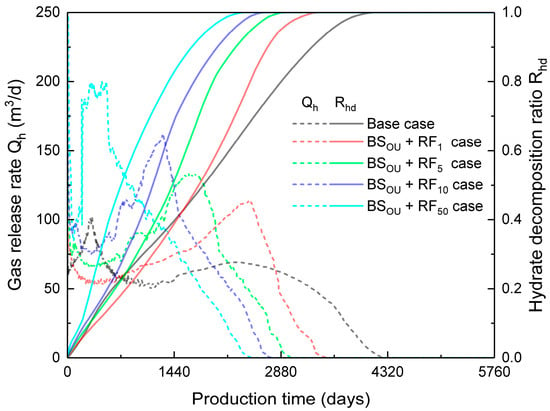

3.3.2. Hydrate Dissociation Behavior

The variation of Qh and Vhd in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases is shown in Figure 13. As can be seen, the peak value of Qh increases from 122 to 204 m3/d as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, which is 1.72–2.87 times that of the base case. Additionally, the Th reduced from 3370 to 2380 days as Cf increased from 1 to 50 D·cm, a reduction of 760–1750 days relative to the base case. As a result, increasing Cf in BS + RF cases is still an effective method for promoting hydrate decomposition.

Figure 13.

Variation of Qh and Rhd in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases.

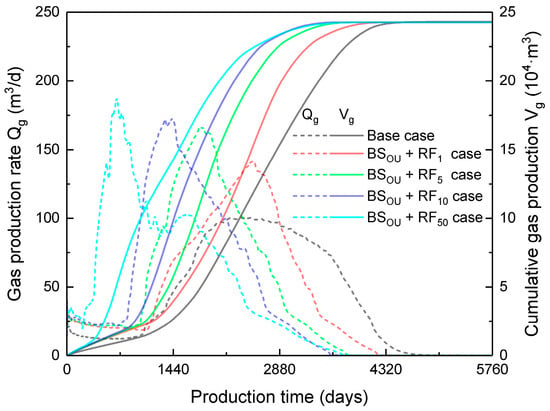

3.3.3. Gas Production Behavior

Figure 14 shows the variation of Qg and Vg in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases. The Qg in the BS + RF cases is much higher than that in the base case. Furthermore, as CF increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, the peak value of Qg increases from 142 to 186 m3/d, and the Tgr is shortened from 4210 to 3720 days, indicating that the extraction efficiency is greatly improved by increasing Cf. The final Vg within 5760 days in all cases is consistent, indicating there is no gas leakage. As a result, BS can greatly improve gas recovery efficiency while addressing gas leakage induced by RF.

Figure 14.

Variation of Qg and Vg in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases.

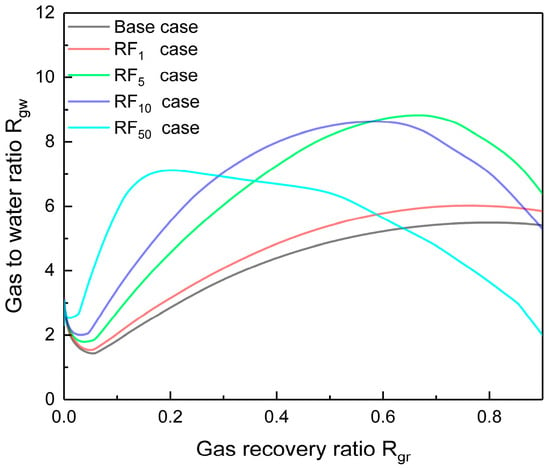

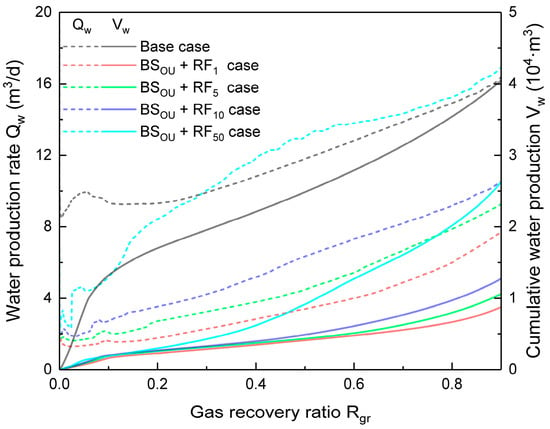

3.3.4. Water Production Behavior

The variation of Qw and Vw in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases is shown in Figure 15. The Qw in Cf of 1–10 D·cm cases is much lower than that in the base case. For Cf of 50 D·cm, Qw is higher than that of the base case in the mid and late periods. In addition, Qw and Vw increase with increasing Cf. At Rgr of 0.7, Vw increases from 0.55 to 1.61 × 104 m3 as Cf increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, accounting for 17–51% of the base case. Thus, significant reductions in water production are achieved.

Figure 15.

Variation of Qw and Vw in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases.

Figure 16 shows the variation of Rgw in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases. The Rgw in BS + RF cases is much higher than in the base case, and it decreases with increasing Cf. Specifically, the Rgw at Rgr of 0.7 decreases from 30 to 10 as CF increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, 1.84–5.53 times higher than the base case. Therefore, combining BS with RF greatly improves gas–water production performance.

Figure 16.

Variation of Rgw in the base, BSOU + RF1, BSOU + RF5, BSOU + RF10, and BSOU + RF50 cases.

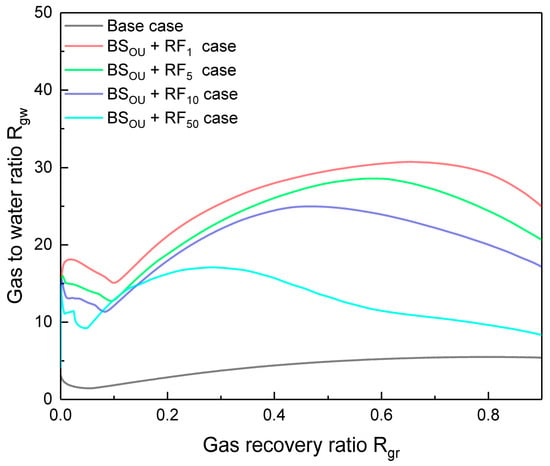

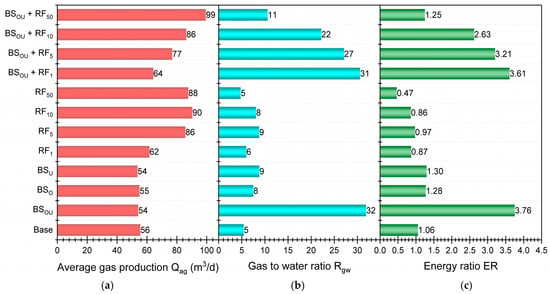

4. Synergistic Effects of BS and RF

From the analysis of the above results, it is found that the hot water loss and boundary water intrusion can be addressed by BS; RF can significantly improve extraction efficiency, but also exacerbate the gas leakage, whereas the combination of the two seems to result in a satisfactory production behavior. Here, the synergistic effects of BS and RF on gas and water production are analyzed with the average gas production rate Qag (Figure 17a) and Rgw (Figure 17b) at Rgr of 0.7. In addition, for the multi-well injection development mode, energy ratio ER, defined by Vg·Cg/[Cw·Mi·(Ti–T0)], is a crucial parameter to measure the economy and feasibility of exploitation [53]. As a result, the ER at Rgr of 0.7 is employed as a key indicator for synergistic effect analysis (Figure 17c). Notably, the ER used here did not account for the energy required to create artificial barriers and perform reservoir fracturing. Given the significant challenges in reconstructing hydrate deposits, more comprehensive economic feasibility assessments need to be conducted based on systems analysis methods before field application [54].

Figure 17.

The Qag (a), Rgw (b), and ER (c) at Rgr of 0.7 in all simulation cases.

As can be observed from Figure 17a, the Qag in the BSO, BSU, and BSOU cases is slightly lower than that in the base case. The mechanism involves the thermal decomposition gas accumulating around the injection well, which suppresses hot water injection and thereby reduces the thermal stimulation area. This indicates that boundary sealing alone does not enhance productivity. Surprisingly, Qag can be significantly increased by RF, especially at Cf ≥ 5 D·cm. Furthermore, the synergistic effect of BS and RF shifts with changes in Cf. That is, they exhibit positive synergy at Cf of 1 and 50 D·cm, and negative synergy at Cf of 5 and 10 D·cm. However, this synergistic effect is not significant as the variation interval of Qag is only [−9, 11]. This indicates that in fractured reservoirs, the effect of BS on productivity is very limited. Furthermore, under the synergistic effect of BS and RF, Qag increases significantly with the increase in Cf, specifically from 64 to 99 m3/d as C increases from 1 to 50 D·cm, an enhancement of 10–45 m3/d relative to the BSOU case. Given that BS can address RF-induced methane leakage and has a limited impact on Qag, it is suggested here to increase productivity by adjusting Cf.

As can be seen from Figure 17b, relative to the base case, there is very limited improvement in Rgw by RF alone or sealing one open boundary. However, simultaneously sealing the upper and lower boundaries obtains the highest Rgw of 32, 6.40 times that of the base case. At different Cf values, the Rgw after boundary sealing is all enhanced, which demonstrates the excellent water control ability of the BS. However, the increase in Cf weakens the water control ability of BS as a considerable amount of injected water induces severe water flooding. Nevertheless, the final water yield under the synergistic effect of BS and RF is still much lower than that of the base case.

As can be seen from Figure 17c, the ER of the base case is 1.06, indicating that it is not economically feasible to develop challenging hydrates directly using the multi-well injection-production mode. After the application of BS, the ER reaches 1.28, 1.30, and 3.76 for the BSO, BSU, and BSOU cases, respectively, indicating that only the simultaneous sealing of the upper and lower boundaries could significantly improve ER because hot water loss is effectively addressed. The ER values in the RF case are all lower than 1.0, indicating that the application of RF alone is still not economically feasible. In addition, ER decreases significantly with increasing Cf under the synergistic effect of BS and RF. However, they are still greater than 1.0, 1.18–3.41 times that of the base case.

To summarize, BS can effectively address boundary water intrusion and hot water loss, thereby substantially increasing Rgw and ER, but barely affecting Qag, whereas RF can significantly increase Qag, but also induce severe gas leakage and decrease Rgw and ER. Nevertheless, with the synergistic effect of the two, safe extraction and the relatively ideal production behavior can be obtained by regulating the Cf.

5. Conclusions

The present research numerically investigated the injection-production performance under various BS and/or RF cases and thoroughly analyzed their synergistic stimulation mechanisms. The following conclusions can be drawn.

- BS can effectively address boundary water intrusion, hot loss, and methane leakage, thereby reducing water production and enabling the full utilization of injection energy. However, it cannot speed up hydrate decomposition and gas production. Additionally, partial sealing does not fully prevent hot water loss and gas escape.

- RF is very effective in facilitating hydrate decomposition and gas recovery, and the extraction efficiency improves greatly with increasing Cf. However, the final ER is lower than 1.0 due to the severe water flooding induced by the fracture, making it unfeasible for economic extraction. Additionally, RF exacerbates the risk of gas leakage, which poses a great challenge for the safe exploitation of marine hydrates.

- There is no methane leakage under the synergistic effect of RF and BS. Furthermore, Qh and Qg improve significantly as Cf increases, whereas Rgw and ER show the opposite trend. Therefore, rational regulation of Cf value is essential to obtain satisfactory multi-well injection-production behavior, with 1–10 D·cm recommended.

- BS is an indispensable technology for the economic and safe extraction of offshore challenging hydrates under the multi-well injection-production mode. Although RF is helpful for hydrate decomposition and gas production, its induced water flooding and methane leakage should not be neglected in future applications.

The current simulations indicate that the combination of BS and RS can significantly enhance the performance of the injection-production well pattern. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the fracture and barrier settings in our model are relatively ideal to maximize the desired effect, and the injection-production parameters employed also need further evaluation and optimization. Additionally, a homogeneous model without interlayers was employed because the hydrate distribution remains unclear. Consequently, follow-up research should fully account for these issues to advance and support engineering implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N. and K.L.; data curation, K.L.; software, X.Z. and S.N.; writing—original draft, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was Funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department, grant number QN2024286.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Soga, K.; Lee, S.L.; Ng, M.Y.A.; Klar, A. Characterisation and engineering properties of Methane hydrate soils. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Characterisation and Engineering Properties of Natural Soils, Singapore, 29 November–1 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Milkov, A.V. Global estimates of hydrate-bound gas in marine sediments: How much is really out there? Earth-Sci. Rev. 2004, 66, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B.; Sandler, S.I. Global Distribution of Methane Hydrate in Ocean Sediment. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, D.F.; Greinert, J.; Artemov, Y.; Beaubien, S.E.; Wüest, A. Fate of rising methane bubbles in stratified waters: How much methane reaches the atmosphere? J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, 09007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.R.; Yang, S.H.B.; Babu, P.; Linga, P.; Li, X. Review of natural gas hydrates as an energy resource: Prospects and challenges. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 1633–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zheng, T.; Cui, J.; Yuan, Q.; Qin, H.; Sun, C.; Chen, G. Review on the accumulation behavior of natural gas hydrates in porous sediments. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Sha, Z.; Liang, J.; Wu, N.; Qiao, S.; Cong, X.; Yang, R. Gas hydrates distribution in the Shenhu Area, northern South China Sea: Comparisons between the eight drilling sites with gas-hydrate petroleum system. Geol. Acta 2016, 14, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.; Lu, J.A.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, J.; Kuang, Z.; Lu, C.; Kou, B.; Lu, Q.; Wang, J. Fine-grained gas hydrate reservoir properties estimated from well logs and lab measurements at the Shenhu gas hydrate production test site, the northern slope of the South China sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 122, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liang, J.; Wei, J.; Lu, J.A.; Su, P.; Lin, L.; Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Deng, W.; Yang, X.; et al. Geological and geophysical features of and controls on occurrence and accumulation of gas hydrates in the first offshore gas-hydrate production test region in the Shenhu area, Northern South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J.; Reagan, M.T.; Boyle, K.L.; Zhang, K. Evaluation of the Gas Production Potential of Some Particularly Challenging Types of Oceanic Hydrate Deposits. Transp. Porous Media 2011, 90, 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ye, J.; Qin, X.; Qiu, H.; Wu, N.; Lu, H.; Xie, W.; Lu, J.; Peng, F.; Xu, Z.; et al. The first offshore natural gas hydrate production test in South China Sea. China Geol. 2018, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Qin, X.; Xie, W.; Lu, H.; Ma, B.; Qiu, H.; Liang, J.; Lu, J.; Kuang, Z.; Lu, C.; et al. The second natural gas hydrate production test in the South China Sea. China Geol. 2020, 3, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Pan, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tu, G.; Nie, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, K.; Chen, C. Commercial production potential evaluation of injection-production mode for CH-Bk hydrate reservoir and investigation of its stimulated potential by fracture network. Energy 2022, 239, 122113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, Y.; Fujii, T.; Sato, A.; Akamine, K.; Naiki, M.; Masuda, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Nagao, J. Key Findings of the World’s First Offshore Methane Hydrate Production Test off the Coast of Japan: Toward Future Commercial Production. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 2607–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, X.; Li, G.; Wang, Y. Investigation into gas production from natural gas hydrate: A review. Appl. Energy 2016, 172, 286–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Si, H.; Li, B.; Li, G. Heat transfer analysis of methane hydrate dissociation by depressurization and thermal stimulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Large Scale Experimental Evaluation to Methane Hydrate Dissociation Below Quadruple Point by Depressurization Assisted with Heat Stimulation. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 4117–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, S.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H. The use of electrical heating for the enhancement of gas recovery from methane hydrate in porous media. Appl. Energy 2018, 227, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Jia, R.; Li, B.; Li, S. Numerical study of depressurization and hot water injection for gas hydrate production in China’s first offshore test site. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium M.R. 2017. Available online: http://www.mh21japan.gr.jp/mh21wp/wp-content/uploads/mh21form2017_doc01.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Li, G.; Moridis, G.J.; Zhang, K.; Li, X. Evaluation of Gas Production Potential from Marine Gas Hydrate Deposits in Shenhu Area of South China Sea. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 6018–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Moridis, G.J.; Zhang, K.; Wu, N. A huff-and-puff production of gas hydrate deposits in Shenhu area of South China Sea through a vertical well. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 86–87, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.-C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.-S.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.-Y. Production behaviors and heat transfer characteristics of methane hydrate dissociation by depressurization in conjunction with warm water stimulation with dual horizontal wells. Energy 2015, 79, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Xu, T.; Xin, X.; Wei, M.; Liu, C. Numerical evaluation of the methane production from unconfined gas hydrate-bearing sediment by thermal stimulation and depressurization in Shenhu area, South China Sea. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Zhong, X.; Ma, Y.; Pan, D.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, C. Numerical simulation of a new methodology to exploit challenging marine hydrate reservoirs without impermeable boundaries. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 96, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, M.; Song, Y. Experimental analysis on thermodynamic stability and methane leakage during solid fluidization process of methane hydrate. Fuel 2021, 284, 119020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Min, K.-B.; Song, Y. Observations of hydraulic stimulations in seven enhanced geothermal system projects. Renew. Energy 2015, 79, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nianyin, L.; Yu, J.; Daocheng, W.; Chao, W.; Jia, K.; Pingli, L.; Chengzhi, H.; Ying, X. Development status of crosslinking agent in high-temperature and pressure fracturing fluid: A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 107, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zeng, Q.; Yao, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Yan, X. Numerical Study of Elasto-Plastic Hydraulic Fracture Propagation in Deep Reservoirs Using a Hybrid EDFM–XFEM Method. Energies 2021, 14, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Liu, K.; Zhong, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Song, J. Research on Hydraulic Fracture Propagation Patterns in Multilayered Gas Hydrate Reservoirs Using a Three-Dimensional XFEM-Based Cohesive Zone Method. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 5106–5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Igarashi, A.; Suzuki, K.; Nagakubo, S.; Matsuzawa, M.; Yamamoto, K. Laboratory Study of Hydraulic Fracturing Behavior in Unconsolidated Sands for Methane Hydrate Production. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC19324), Houston, TX, USA, 5–8 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Yang, L.; Jia, R.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Simulation Study on the Effect of Fracturing Technology on the Production Efficiency of Natural Gas Hydrate. Energies 2017, 10, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Jia, R.; Li, B. Evolution on the Gas Production from Low Permeability Gas Hydrate Reservoirs by Depressurization Combined with Reservoir Stimulation. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15819–15828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Liu, F.; Fu, P.; White, M.D.; Settgast, R.R.; Morris, J.P. Gas Production from Hot Water Circulation through Hydraulic Fractures in Methane Hydrate-Bearing Sediments: THC-Coupled Simulation of Production Mechanisms. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4448–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, G.; Guo, W.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y. Enhancement of gas production from natural gas hydrate reservoir by reservoir stimulation with the stratification split grouting foam mortar method. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 81, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Jia, R.; Li, B. Numerical simulation of horizontal well hydraulic fracturing technology for gas production from hydrate reservoir. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 112, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Pan, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Li, X.; Tu, G.; Chen, C. Fracture network stimulation effect on hydrate development by depressurization combined with thermal stimulation using injection-production well patterns. Energy 2021, 228, 120601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Song, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. Numerical Evaluation of a Novel Development Mode for Challenging Oceanic Gas Hydrates Considering Methane Leakage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Du, Z.; Chen, X.; Liang, B. The critical rate of horizontal wells in bottom-water reservoirs with an impermeable barrier. Pet. Sci. 2012, 9, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhu, W.; Pan, B. Laboratory evaluation on oil-soluble resin as selective water shut-off agent in water control fracturing for low-permeability hydrocarbon reservoirs with bottom aquifer. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 225, 211672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Pu, W.; Jin, X.; Shen, C.; Ren, H. Review of the micro and Macro mechanisms of gel-based plugging agents for enhancing oil recovery of unconventional water flooding oil reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Liu, K.; Xu, K.; Zhong, X.; Tang, S.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Numerical study on the stimulation effect of boundary sealing and hot water injection in marine challenging gas hydrate extraction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Lu, J.A.; Su, X.; Schultheiss, P.; Holland, M.; Zhu, Y. Gas Hydrate System of Shenhu Area, Northern South China Sea: Geochemical Results. J. Geol. Res. 2011, 2011, 370298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J.; Collett, T.S. Strategies for Gas Production from Hydrate Accumulations Under Various Geological and Reservoir Conditions; Report LBNL-52568; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002.

- Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, B. Assessment of Gas Production Potential from Hydrate Reservoir in Qilian Mountain Permafrost Using Five-Spot Horizontal Well System. Energies 2015, 8, 10796–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G. Analytic modeling and large-scale experimental study of mass and heat transfer during hydrate dissociation in sediment with different dissociation methods. Energy 2015, 90, 1931–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J. Numerical Studies of Gas Production from Methane Hydrates. SPE J. 2003, 8, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J. Numerical Studies of Gas Production from Class 2 and Class 3 Hydrate Accumulations at the Mallik Site, Mackenzie Delta, Canada. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2004, 7, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J.; Kowalsky, M.B.; Pruess, K. Depressurization-Induced Gas Production from Class-1 Hydrate Deposits. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2007, 10, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Moridis, G.; Chong, Z.R.; Tan, H.K.; Linga, P. Numerical analysis of experimental studies of methane hydrate dissociation induced by depressurization in a sandy porous medium. Appl. Energy 2018, 230, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Suzuki, A.; Kogawa, T.; Okajima, J.; Komiya, A.; Maruyama, S. Numerical analysis of gas production from layered methane hydrate reservoirs by depressurization. Energy 2019, 166, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Feng, Y.; Okajima, J.; Komiya, A.; Maruyama, S. Production behavior and numerical analysis for 2017 methane hydrate extraction test of Shenhu, South China Sea. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 53, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.-C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.-S.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y. Three dimensional experimental and numerical investigations into hydrate dissociation in sandy reservoir with dual horizontal wells. Energy 2015, 90, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyushin, Y.; Nosova, V.; Krauze, A. Application of Systems Analysis Methods to Construct a Virtual Model of the Field. Energies 2025, 18, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.