1. Introduction

Concurrently, modern individuals spend a considerable portion of their daily lives inside vehicles, a confined environment where the infiltration of on-road pollutants can adversely affect occupant health and comfort. In particular, atmospheric particulate matter (PM2.5) is closely linked to respiratory illnesses, with studies indicating that exposure can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and respiratory ailments, including asthma [

1,

2].

Poor in-cabin air quality (IAQ) caused by the infiltration of external pollutants can be mitigated through appropriate vehicle ventilation settings, thereby reducing occupant exposure [

3,

4,

5]. Furthermore, continuous operation of the HVAC system in recirculation mode can reduce the compressor load, thereby enhancing the overall system performance. However, while this mode minimizes the inflow of external pollutants and reduces particle exposure for occupants, it simultaneously leads to an accumulation of carbon dioxide (CO

2) resulting from occupant breath [

6,

7]. Prolonged exposure to elevated CO

2 concentrations can negatively impact drivers, causing decreased concentration and impaired cognitive function [

8,

9]. Therefore, effective control of particulate and CO2 levels inside the vehicle cabin requires a well-designed ventilation strategy that optimizes the mixture of recirculated and fresh air. This context necessitates an integrated design approach for R744 systems that extends beyond energy efficiency to combine IAQ control strategies.

Accordingly, this study analyzes the correlation between energy efficiency and IAQ by simulating a model of an R744 heat pump system, integrated with an air quality model for both CO2 and PM2.5, under various fresh-to-recirculated air ratios using the 1D multi-physics tool, Simcenter AMEsim. Using the developed model, we comprehensively analyzed the system dynamic behavior, control stability, energy consumption (e.g., , SOC), and in-cabin pollutant concentration changes under various air mixing ratios and the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Cycle (WLTC). Ultimately, this research aims to establish a foundational basis for an intelligent, integrated control strategy capable of maximizing driving range while simultaneously ensuring occupant comfort and health amidst this complex trade-off.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. R744

2.1.1. R744 Heat Pump System Modeling

WANG et al. [

10] experimentally compared and analyzed the performance of R744 and R134a refrigerant heat pump systems under various cooling and heating modes. The automotive R744 HVAC system model for this study was constructed based on the R744 heat pump system from the aforementioned prior study, which comprised an outdoor heat exchanger, an indoor evaporator, an indoor gas cooler, an electronic expansion valve (EEV), a scroll compressor, a 4-way valve, an internal heat exchanger (IHX), and an accumulator. Consistent with the prior study, micro-channel heat exchangers were adopted to withstand the high-pressure operating conditions inherent to the R744 refrigerant. While the original experiment utilized an integrated unit combining the IHX and the accumulator, this study modeled these two components separately due to limitations in implementing an integrated component within the AMEsim environment. In the simulation, the compressor RPM is modulated to meet the target cabin temperature, and the EEV opening is adjusted through a PID controller. Based on the optimal high-side pressure range proposed by Ying et al., the EEV control logic for cooling mode was designed to maintain operation within a pressure range of 80 to 160 bar [

11]. Similarly, for heating mode, the controller was designed to maintain the high-side pressure between 70 and 100 bar, following the research conducted by Dong et al. [

12]. Regarding the heat exchangers, the model calculates heat transfer phenomena in real-time by dynamically computing the convective heat transfer coefficient based on the immediate environmental conditions for both cooling and heating modes. Although the same heat-exchanger component model is used to represent both the evaporator and the in-cabin heat exchanger within the simulation framework, their thermodynamic roles differ depending on the operating mode. In heating operation, the heat exchanger functioning as the indoor heat exchanger (physically a gas cooler in the transcritical R744 cycle) is connected in parallel with the evaporator and activated by switching the refrigerant flow path through a 4-way valve. Under this mode, high-temperature and high-pressure refrigerant discharged from the compressor flows directly into the indoor heat exchanger. Consequently, the inlet enthalpy of the gas cooler includes the compressor work. The heating capacity is therefore calculated from the refrigerant-side enthalpy difference across the indoor gas cooler, whereas the cooling capacity is obtained from the enthalpy difference across the evaporator in cooling mode. Because the inlet enthalpy of the gas cooler already accounts for the compressor work, the magnitudes of heating and cooling capacities are neither physically nor numerically identical. The refrigerant-side energy balance is consistently satisfied in the model, such that the heating capacity equals the sum of the cooling capacity and the compressor work. Finally, the complete automotive R744 heat pump system was modeled within the AMEsim environment, as depicted in

Figure 1, where the red and blue arrows denote the refrigerant flows on high pressure and low pressure sides, respectively.

2.1.2. R744 Heat Pump System Validation

The model validation was performed by comparing simulation outputs results with the experimental data presented in the literature [

10]. This assessment was conducted under the specific cooling scenario conditions and heating scenario conditions defined in that study. In this study, the validation was performed using heating/cooling capacity and the Coefficient of Performance (

) as the validation metrics. The validation focused on these metrics, for which the respective calculation methods are provided in the following equations.

Because these performance indicators are evaluated on the basis of specific enthalpy differences rather than temperature alone, ambient humidity is inherently incorporated into the validation process. Accordingly, relative humidity serves as an essential input parameter for accurate thermal load calculation and was integrally included in the R744 heat pump simulation framework used in this study.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the comparison between the experimental data and our simulation data for the cooling and heating modes, respectively, under the specified scenario conditions. Whereas the prior study calculated the heating and cooling capacities on the air side by using the air mass flow rate and specific enthalpy difference, our model validation was performed by calculating the capacities on the refrigerant side. Although these calculation methods differ, the average discrepancy between the airside and refrigerant-side calculations was found to be 0.258%, which was thus considered negligible for this validation process. The validation results in cooling modes demonstrated an average error of 7.84% for

and 6.93% for cooling capacity relative to the experimental data. For the heating mode, the average errors were 6.46% for

and 7.52% for heating capacity, respectively, demonstrating a high degree of agreement with the experimental data.

2.2. Air Quality

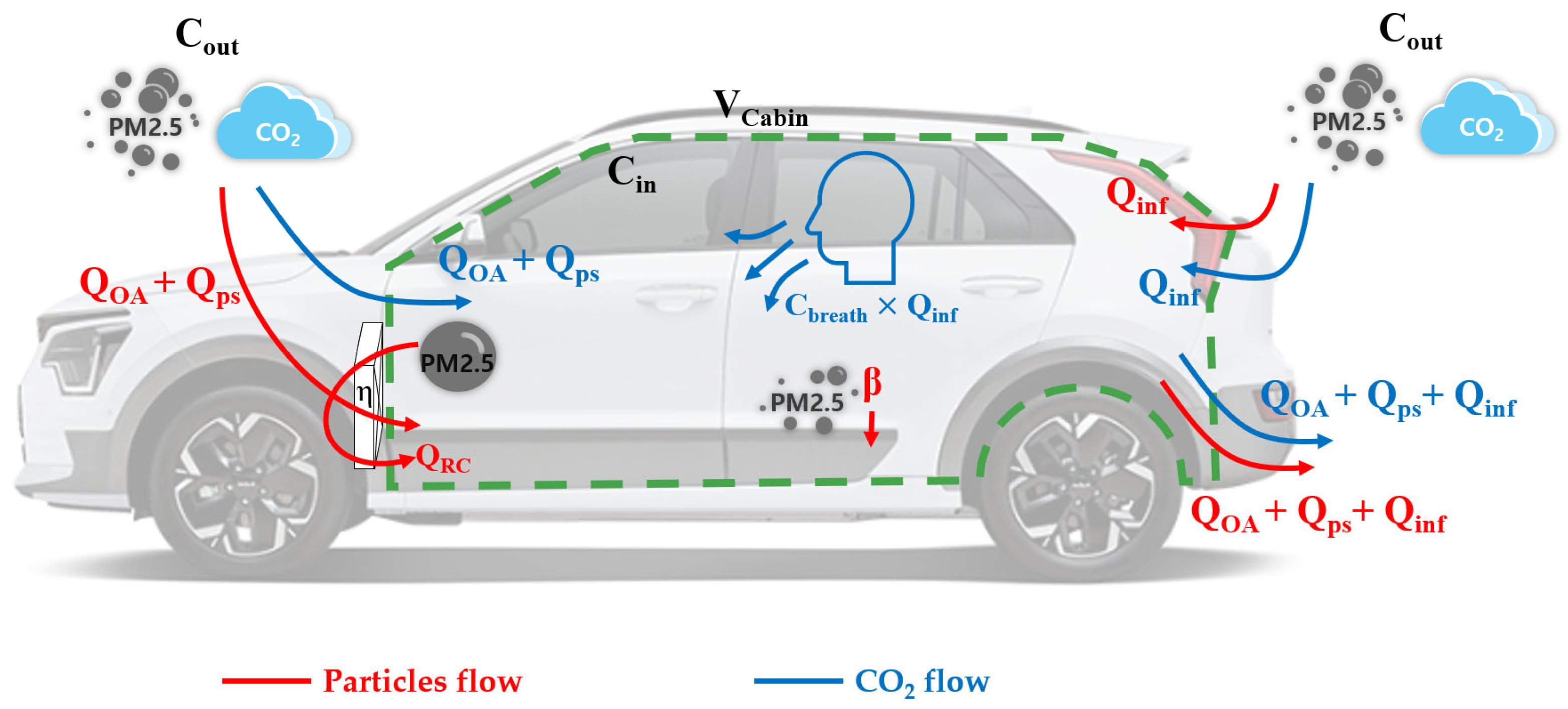

2.2.1. Air Quality Modeling

The vehicle cabin is a confined space, largely isolated from the external environment, and is therefore susceptible to the accumulation of pollutants that can adversely affect occupant health and comfort. In this study, an IAQ model was developed to predict the concentrations of pollutants in real-time, for analyzing the trade-off with energy efficiency and designing an optimized, integrated control strategy The scope of pollutants was specifically limited to two species: carbon dioxide (CO

2), generated by occupant breath, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less, which infiltrates from the external environment. The in-cabin concentration of each pollutant was modeled based on a mass balance equation, which accounts for the rates of inflow, generation, exit, and removal within the vehicle interior [

4].

In fresh air mode, the infiltration of PM2.5 into the cabin occurs through three primary pathways: mechanically driven airflow from the HVAC fan (

), air flow induced by vehicle speed or wind (

), and uncontrolled infiltration through the vehicle surface, such as cracks (

). Airflows

and

pass through the HVAC filter, where a portion of particles is removed according to the filter efficiency (

), whereas

bypasses the filtration system, allowing unfiltered particles to penetrate directly into the cabin. This infiltration process is governed by a penetration factor (

= 0.6), which accounts for the fraction of particles lost within the cracks and crevices of the vehicle surface before they can enter the cabin. Furthermore, particles suspended within the cabin are able to removal by deposition onto interior surfaces, a process characterized by a deposition loss rate constant (

= 8 h

−1). Particle removal through occupant breath was considered negligible, as its rate is significantly smaller than those of other ingress and removal mechanisms [

13]. Also the effects of humidity-induced phase changes or hygroscopic growth of PM2.5 particles were excluded.

Similarly, CO

2 enters the cabin with the same air exchange rates (

,

,

); however, unlike particulate matter, it is a non-filterable thus passes through the HVAC filter without removal. Simultaneously, CO

2 is generated within the cabin as a direct result of occupant breath. In recirculation mode, the fresh air intake is nominally closed, and the interior air is recirculated at a flow rate as

. During this operation, particles are progressively removed as the air passes repeatedly through the filter; however, uncontrolled infiltration (

) remains a persistent source of external particle entry. Consequently, the filter acts as the primary sink for in-cabin particles, while infiltration serves as the sole source for their introduction.

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic flow of pollutants, depicting the transport mechanisms for PM2.5 and CO

2 within the vehicle cabin.

The primary internal source of CO

2 is occupant breath, the rate of which is dictated by metabolic activity; for this model, a constant generation rate of 18.3 g/h per adult was assumed for the simulations, corresponding to an average respiration volume of 6.5 L/min [

14]. This IAQ model was subsequently coupled with the previously mentioned R744 heat pump system model. The fresh air intake volume, in particular, emerges as the critical linking variable, as it simultaneously impacts both cabin thermal/humidity control and indoor pollutant dilution, thereby leading to the central trade-off that must be resolved in an integrated control strategy.

2.2.2. Infiltration Flow

Infiltration into vehicles is defined as the uncontrolled flow of ambient air into the cabin through crack in the vehicle surface, such as door seals and window. This phenomenon provides a pathway through which unfiltered external pollutants can enter the cabin, by passing the main HVAC filtration system. Previous study has characterized the infiltration flow rate and developed mathematical models using both experimental data and numerical simulations [

4].

Equation (7) represents the pressure differential (

) developed between the vehicle cabin and the exterior, which is induced by the fresh air intake (

,

) through the HVAC system. In this equation,

and

are vehicle specific parameters describing the cabin leakage characteristics.

denotes the air intake flow rate, which is induced by the vehicle forward motion or ambient wind rather than by the mechanical fan. This flow rate (

) has a linear relationship with the vehicle speed (

) and is calculated using Equation (8).

Equation (9) defines the aerodynamic pressure differential (

) generated on the vehicle exterior surface during driving; It is an empirical relation derived from experimental differential pressure measurements taken at the vehicle trunk location. The coefficients in this equation

,

, and

vary by vehicle type, with the source literature providing values of 0.33, 0.51, 0.04 for a sedan and 0.23, 4.44, 0.02 for a minivan, respectively. In the present study, the parameters corresponding to the sedan (

= 0.33,

= 0.51,

= 0.04) were adopted for the model.

Using the previously mentioned pressure differential, the infiltration pressure difference (

) is derived in Equation (10). Infiltration through the vehicle cracks occurs when this infiltration pressure is positive (

> 0). This resulting pressure differential dP

inf is then used to calculate the final infiltration flow rate (

), as expressed in Equation (11). Herein,

represents a reverse flow correction factor, employed to compensate for flow discrepancies between infiltration and exfiltration; a value of 0.65, adopted from the literature, was used for this study. Herein,

represents a reverse leakage flow correction factor, employed to compensate for flow discrepancies between infiltration and exfiltration; a value of 0.65, adopted from the literature, was used for this study.

To estimate the accumulation of in-cabin pollutants, the relationships defined in Equations (7)–(11) were used and solved within the simulation model. The ambient CO

2 concentration was set to 420 ppm, based on South Korea 2020 annual average. For PM2.5, an ambient concentration of 100 μg/m

3 was used, which exceeds the threshold for the ‘Very Bad’ (

76 μg/m

3 ~) air quality category under South Korean standards. Furthermore, in-cabin occupant was assumed to be a single person. The vehicle specific parameters (

,

) and the cabin volume (

) were adopted from the previous literature, specifically selecting the values corresponding to the vehicle with the lowest characterized infiltration rate [

4]. This selection was deliberately made to minimize the influence of uncontrolled infiltration, thereby isolating the effects of the controlled ventilation strategies (the fresh-to-recirculated air ratio) on system performance. The detailed parameters used in-cabin air quality model are summarized in

Table 1.

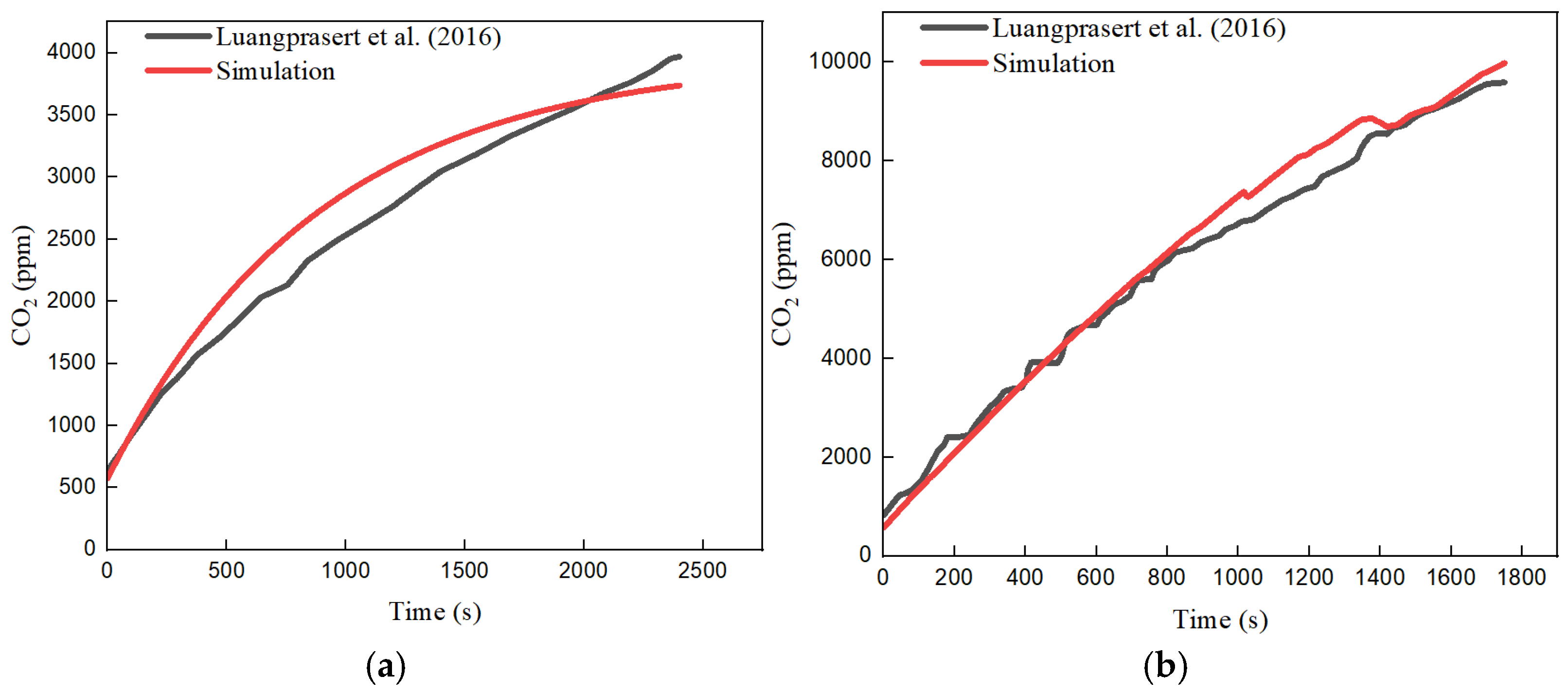

2.2.3. Air Quality Model Validation

Figure 5 shows the comparative results of CO

2 accumulation between our simulation model and the data presented by Lesage et al. [

15]. Lesage et al. sought to optimize the simultaneous achievement of IAQ and thermal comfort, all while minimizing energy costs. To this end, they used a simulation tool to comprehensively analyze the influence of ventilation strategies on CO

2 concentration, humidity levels, and energy consumption under various operating conditions.

Figure 5 shows the simulation results from our model compared to the experimental data for in-cabin CO

2 concentration build-up over time, conducted under stationary vehicle and full recirculation mode conditions. The comparison confirms a good agreement between the simulation and experimental data, with a relative error margin of less than 7%.

For a second validation case, experimental data was referenced from Laungpraset et al. [

16], who conducted a study measuring real-world CO

2 concentrations using sensors during on-road driving tests.

Figure 6a presents the comparison for the static driving condition, plotting our simulation results against the experimental data from Laungpraset et al. Similarly,

Figure 6b illustrates the simulation results for the dynamic driving condition under the setting of two occupants and full recirculation mode. Validation results indicate that the simulation results exhibit trends that are highly similar to the experimental data, with relative errors within 7% for

Figure 6a and 5% for

Figure 6b, respectively. The discrepancies observed between the simulation results and the experimental data in

Figure 6 are primarily attributed to parameter uncertainties inherent to the modeling process, rather than random measurement errors. The dominant source of uncertainty arises from the leakage-related parameter

and

, which characterizes the air infiltration behavior of the vehicle cabin. Because the experimental vehicle used in the referenced study and the vehicle configuration assumed in the present simulation cannot be perfectly matched, uncertainties are inevitably introduced in the estimation of the infiltration airflow rate (

). In addition, the simulation model assumes a perfectly mixed cabin air volume, whereas the experimental measurements were obtained at localized positions within the cabin. This difference in spatial representation between the lumped-parameter model and point-wise experimental measurements further contributes to the observed deviations. These discrepancies therefore reflect systematic modeling uncertainties associated with parameter identification and spatial averaging, rather than stochastic errors originating from measurement equipment.

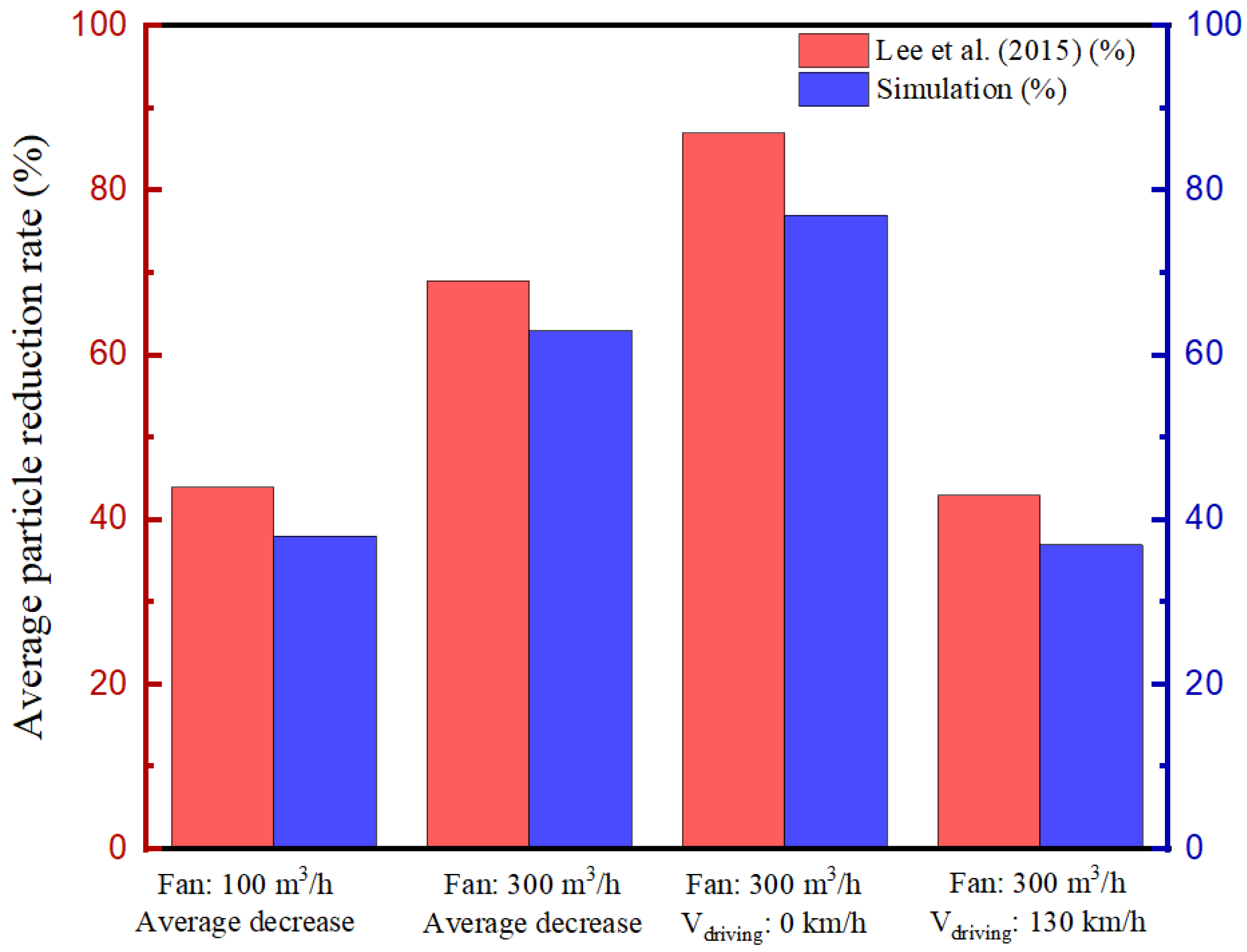

Figure 7 illustrates the comparison of average particle reduction rates under recirculation mode, which were calculated based on the simulated indoor-to-outdoor (I/O) concentration ratios. In the present study, a comparative validation was conducted by simulating the PM2.5 infiltration trends with our model and comparing them against the results of the UFP model proposed by Lee et al. [

4]. It should be noted that these two metrics (UFP and PM2.5) reflect distinct physical characteristics, thus limiting the possibility of a direct absolute quantitative comparison. Accordingly, this validation is primarily used to verify that the model can accurately capture the overall qualitative trends associated with different ventilation strategies. To support this qualitative assessment, the relative error between the simulation and reference data for all evaluated parameters remained within 10%. Furthermore, the system exhibited behavior that closely followed the qualitative trends associated with variations in blower speed and driving speed.

3. Results and Discussion

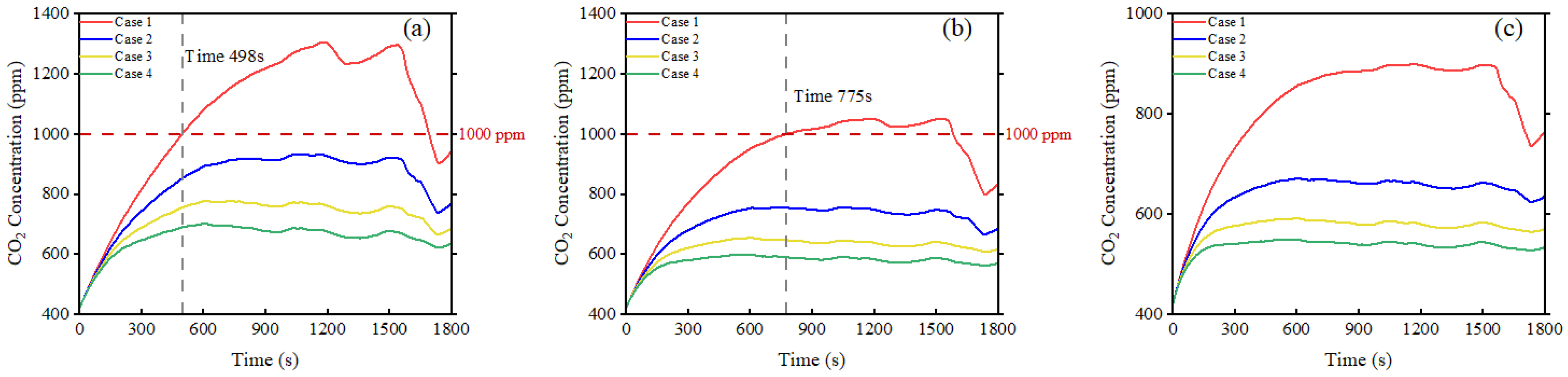

3.1. In-Cabin Air Quality

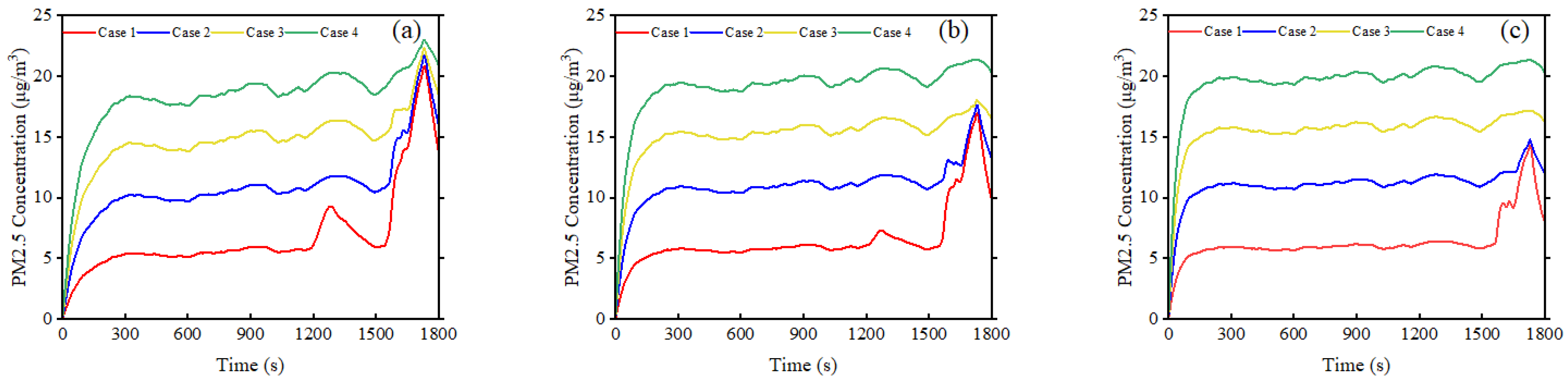

We analyzed the impact of varying the fresh-to-recirculated air ratio on the in-cabin concentrations of the primary pollutants, CO

2 and PM2.5, during R744 system operation. Simulations were performed under four distinct cases, defined by recirculation ratios of 90%, 80%, 70%, and 60%. As occupant breath is the primary internal source of CO

2, dilution from fresh air intake is the essential mechanism for its control. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the results demonstrates a clear inverse relationship between the fresh air intake ratio and the CO

2 concentration. In the case with the lowest fresh air intake (10%), the CO

2 concentration remains at the highest levels, irrespective of the specific blower fan setting. Conversely, the case with the highest fresh air intake (40%) consistently maintains the lowest concentration levels. This result confirms that the inflow of fresh ambient air effectively dilutes the internally generated CO

2. Regarding CO

2 concentration standards, ASHRAE guidelines suggest a comfort threshold below 1100 ppm; however, this standard must be applied flexibly in a vehicular context due to the variability of exposure duration and environmental conditions. Furthermore, South Korean in-door air quality management standards recommend levels below 1000 ppm for public facilities, while the guidelines for public transport vehicles are set at 2000 ppm at non-peak and 2500 ppm at peak congestion. Therefore, for the purpose of this analysis, a CO

2 concentration threshold of 1000 ppm was adopted for the passenger vehicle scenario, assuming a single occupant. As shown in

Figure 9a,b, the time required to reach this 1000 ppm threshold was extended from 498 s to 775 s as the blower fan speed increased, an effect attributed to the higher air exchange rate suppressing the CO

2 concentration build-up.

The other way, as shown in

Figure 9, the primary source of PM2.5 is the external environment; therefore, the fresh air intake rate directly affects the in-cabin concentration. Consequently, the case with the lowest fresh air intake (10%) maintains the lowest PM2.5 concentration. This result is attributed to the minimization of external pollutant inflow, coupled with the continuous recirculation and purification of the cabin air through the HVAC filter. Conversely, the case with the highest fresh air intake (40%) exhibits the highest PM2.5 concentration. This indicates that despite the presence of the HVAC filter, which removes a portion of the incoming pollutants, the increased total mass of contaminants infiltrating from the outside air led to an increase in the in-cabin concentration. Furthermore, as observed in

Figure 9, an increase in the blower flow rate results in a decrease in the infiltration rate for Case 1. This phenomenon is attributed to the rise in cabin pressurization at higher blower speeds, which effectively suppresses the uncontrolled infiltration of external pollutants.

3.2. Summer and Winter Boundary Conditions

For summer operation, the indoor cabin target temperature was set to 22 °C. Unlike buildings, vehicle cabins are highly exposed to radiative heat gains due to thin body panels, extensive glazing surrounding the occupants, and a significantly smaller interior volume. During summer conditions, solar radiation can substantially increase the temperature of exterior surfaces and the mean radiant temperature experienced by occupants. As a result, the thermal environment of a vehicle cabin differs fundamentally from that of typical indoor building spaces, where summer indoor air temperatures around 26 °C are commonly maintained. Consequently, the application of building-based comfort setpoints to vehicle cabins is not directly appropriate, and the target cabin temperature in vehicles must be applied more flexibly. In addition, vehicle occupants generally remain inside the cabin for much shorter durations than in buildings, and therefore the selected target temperature should be regarded as a reference operating condition rather than a strict comfort criterion.

For winter operation, to clearly capture both the degradation of heat pump performance at low ambient temperatures and the increased heating demand associated with ventilation, representative winter operating conditions were considered. Among possible cold-weather scenarios, an ambient temperature of −15 °C was selected as a boundary condition. This temperature represents extreme yet realistic climatic conditions that can occur in cold regions, including parts of South Korea and other mid- to high-latitude areas, and is therefore appropriate for evaluating system performance under severe winter operation. The indoor cabin target temperature was set to 26 °C. Unlike buildings, vehicle cabins are characterized by a much smaller enclosed volume, thinner thermal boundaries, higher air exchange rates, and more complex airflow patterns. Consequently, thermal comfort criteria commonly applied to buildings—where winter indoor temperatures around 20 °C are typically maintained—are not directly applicable to vehicle environments. Previous studies have reported that acceptable thermal comfort in vehicle cabins spans a relatively wide temperature range, typically between approximately 22 and 28 °C, depending on exposure duration, clothing insulation, and operating conditions [

17]. Accordingly, the selected target temperature should be regarded as a reference operating condition rather than a strict comfort criterion, and remains within a realistic and acceptable range for vehicle cabin heating.

3.3. Cooling Mode Result

The commonly cited fresh air requirement of approximately 30 m3/h per person, which is widely used to suppress CO2 accumulation in enclosed spaces, is also applicable to vehicle cabins. In the present study, however, this requirement was not enforced by prescribing a fixed outdoor air flow rate. Instead, the recirculation–outdoor air ratio was selected as the primary control variable, as this approach more accurately reflects practical vehicle HVAC operation. In both heating and cooling mode simulations, the total blower fan flow rate was fixed at 390 m3/h, and a single-occupant condition was assumed. Under this configuration, even the minimum outdoor air case (Case 1), corresponding to an outdoor air fraction of 10%, resulted in an outdoor air intake of approximately 39 m3/h. This value exceeds the per-person fresh air requirement of 30 m3/h, thereby ensuring sufficient ventilation in all simulated scenarios.

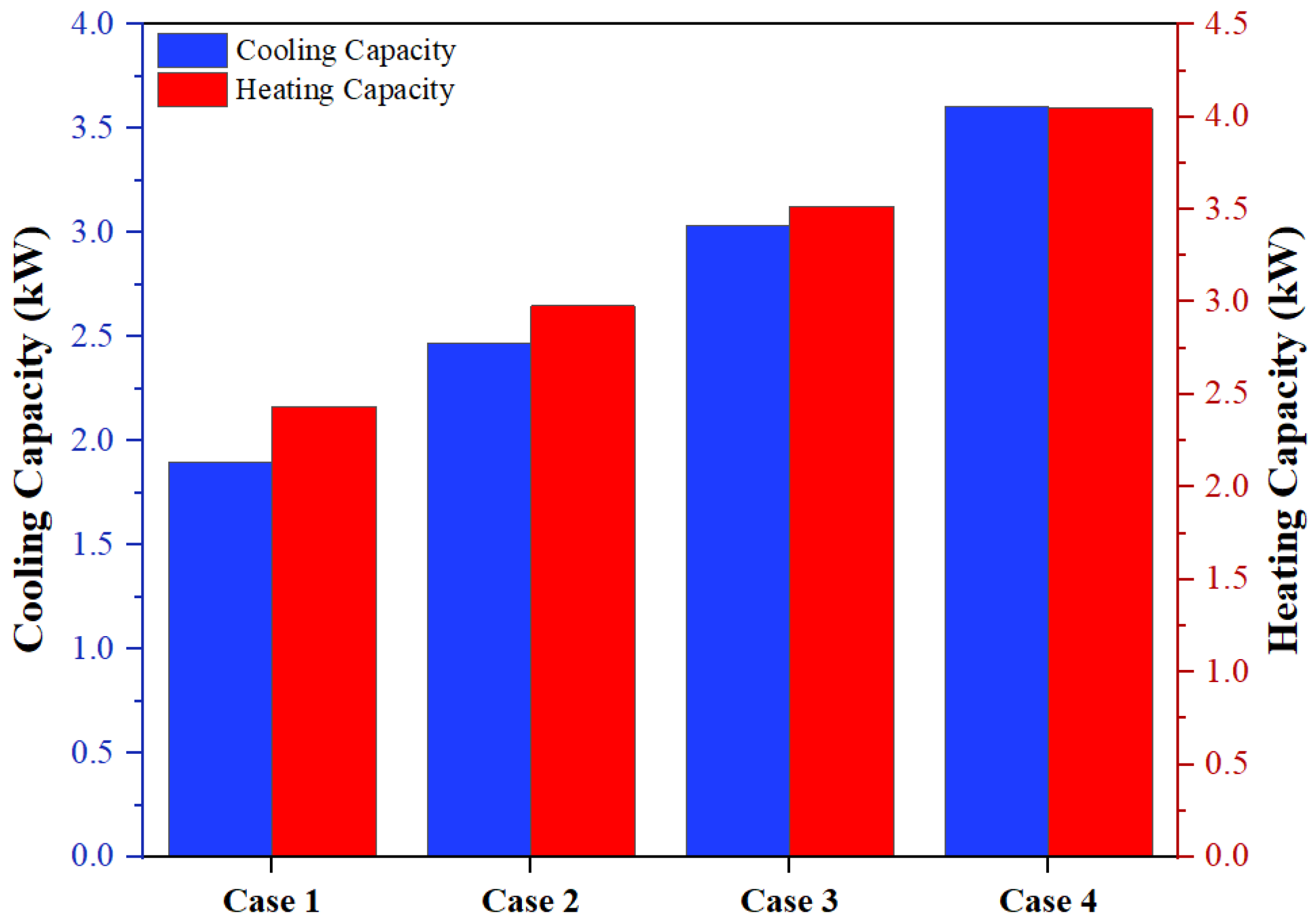

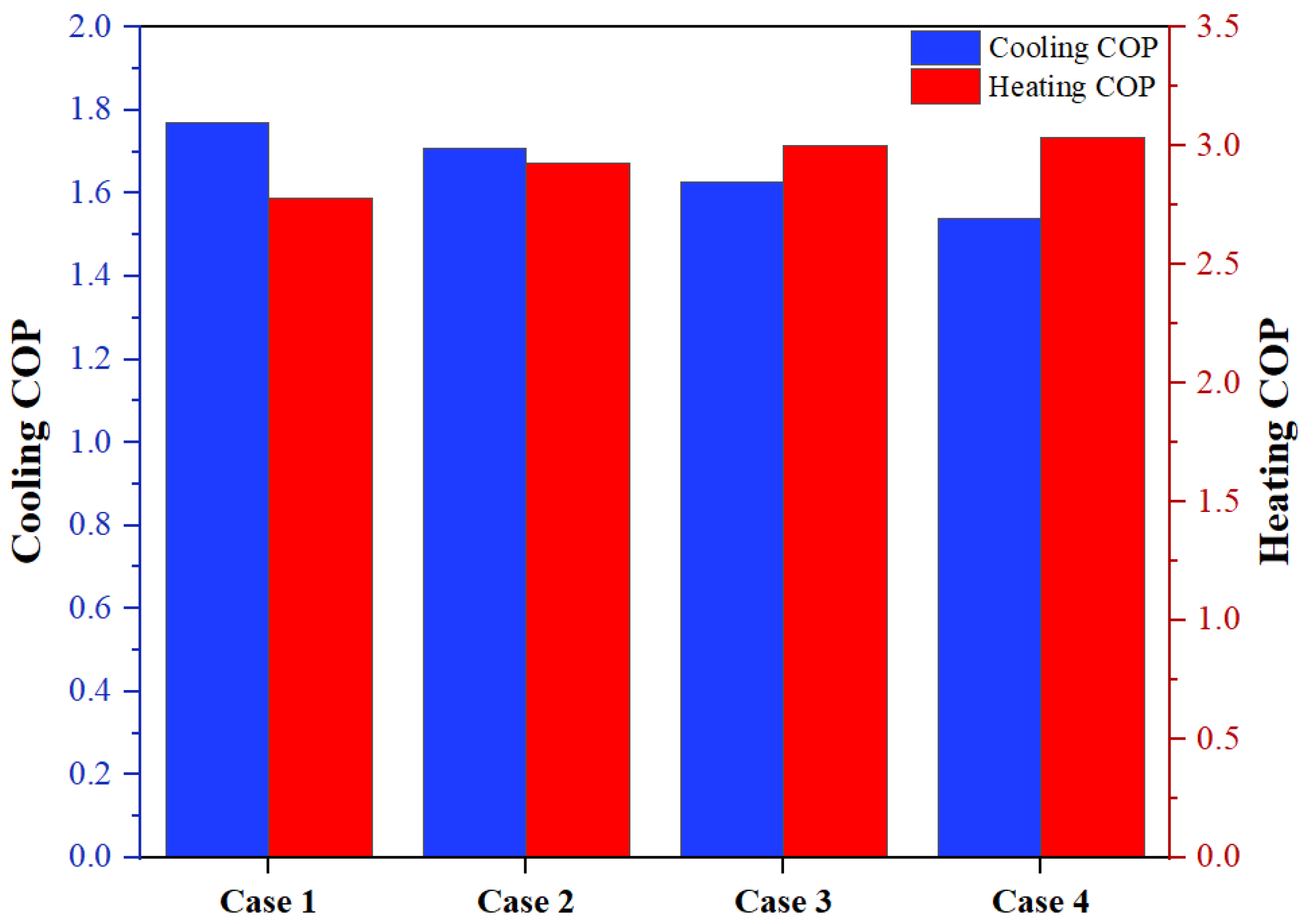

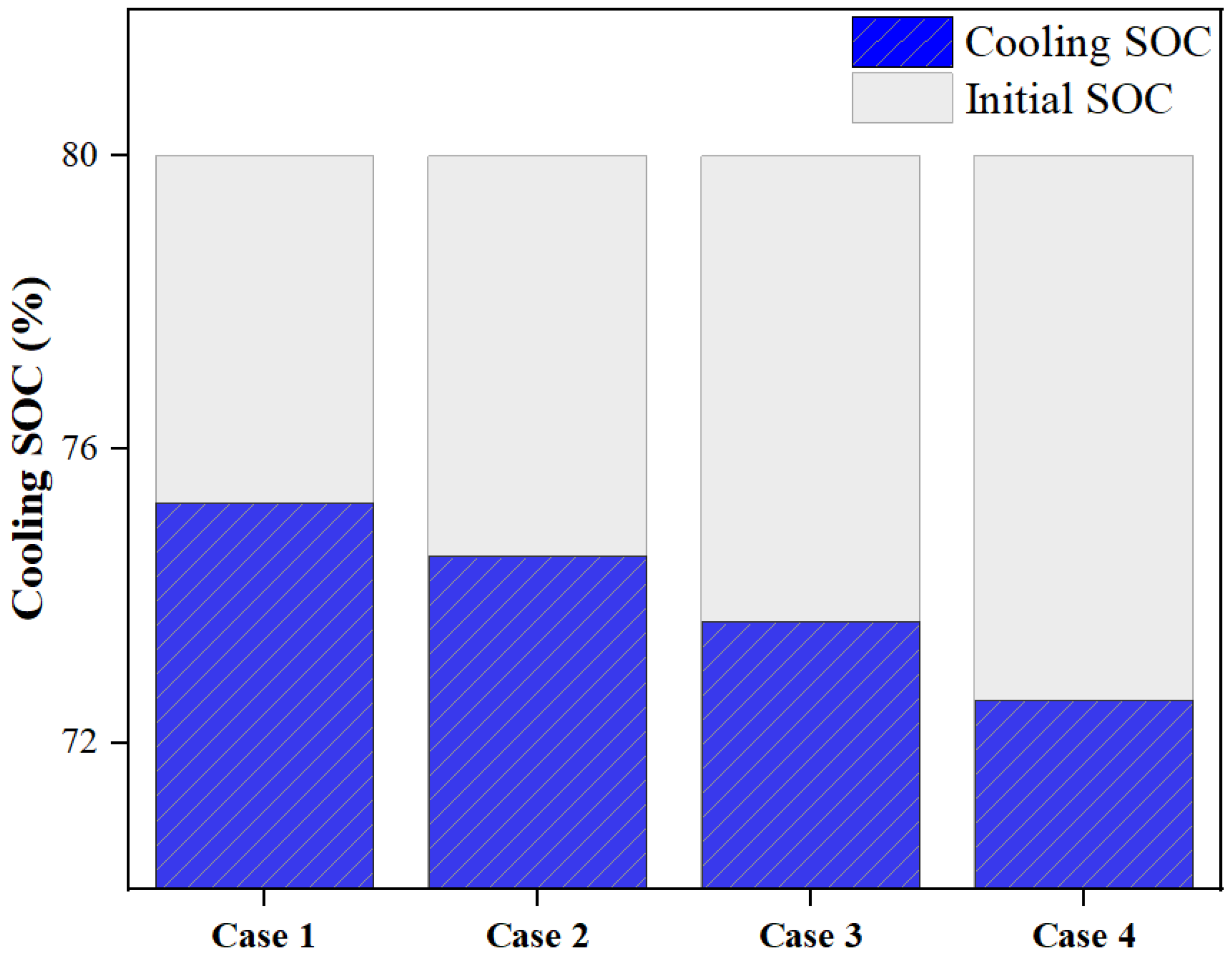

We analyzed the impact of the varying fresh-to-recirculated air ratio on the R744 cooling system performance, specifically its

and SOC of battery in the EV under hot and humid ambient conditions (35 °C, 60% RH) with a cabin target temperature of 22 °C. The simulation results reveals that the system

exhibits a progressive decreasing trend, declining from 1.77 to 1.538 as the fresh air intake ratio increase. Concurrently, the final SOC also decreases as the fresh air intake ratio rise. This degradation in efficiency is directly attributed to the sharp increase in the cooling load, which is driven by the greater inflow of fresh air. As the increased fresh air ratio introduces a larger volume of hot and humid outside air, the enthalpy of the air entering the evaporator rises, consequently increasing the thermal load that the evaporator must remove. To manage this elevated thermal load, the compressor RPM is increased by up to 82% relative to the lowest intake case. As a result, the increased compressor speed leads to a higher refrigerant mass flow rate, which enhances the system cooling capacity, as shown in

Figure 10. Meanwhile, the elevated operating condition causes a rise in the high-side pressure, thereby increasing the compression ratio and ultimately raising the compressor power consumption, as presented in

Figure 11.

Figure 12 illustrates the system

results for both the cooling and heating modes. As shown for the cooling mode, the system

progressively decreases. This trend occurs because, despite an accompanying increase in cooling capacity, the compressor power consumption rises significantly to manage the elevated thermal load from the increased fresh air intake. Regarding the battery SOC, the total change was analyzed relative to an initial 80% capacity, corresponding to the different fresh air intake ratios. As shown in

Figure 13, the results demonstrate that as the fresh air intake ratio rises, the total SOC consumption progressively increases from 4.74% to 7.42%, representing a maximum increase in energy depletion of 57% compared to Case 1. This finding is a direct consequence of the aforementioned increase in compressor power consumption, which, driven by the higher thermal load resulting from increased fresh air intake, consequently leads to greater overall battery consumption.

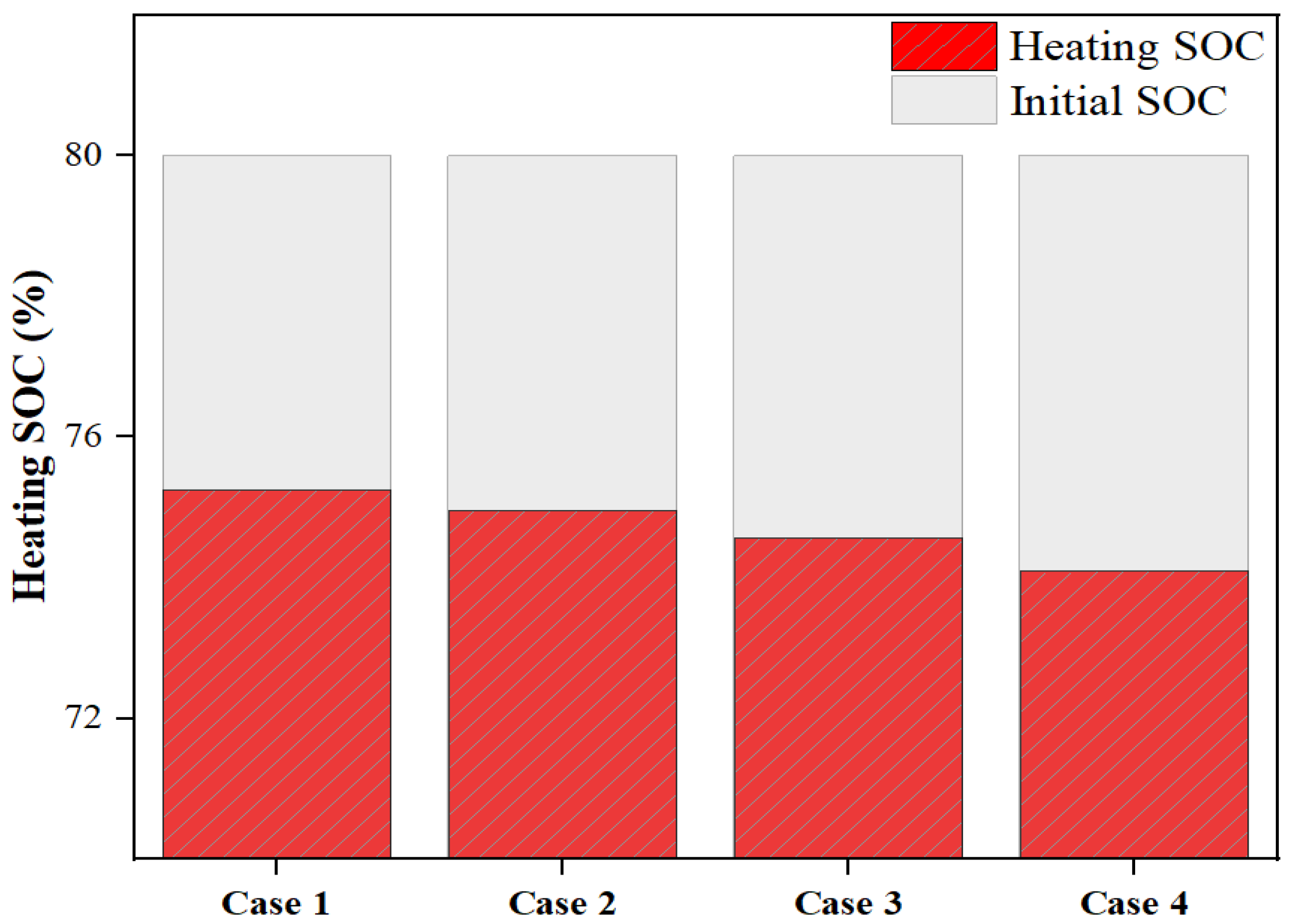

3.4. Heating Mode Result

The results for the heating mode simulation at an ambient temperature of −15 °C, and a target cabin temperature of 26 °C shows a trend similar to the cooling mode: as the intake ratio of cold fresh air increases, the compressor load rise to maintain the target temperature, leading to an observable increase in compressor power consumption of up to 52% compared to Case 1. Regarding heating capacity, this increased compressor load also leads to a higher refrigerant mass flow rate. Crucially, as the fresh air intake ratio increases, the temperature of the air entering the internal heat exchanger decreases. This creates a larger temperature differential against the hot, high-pressure refrigerant, thereby significantly enhancing the overall heat transfer efficiency. As a result, the total heat released from the refrigerant increases, causing the system heating capacity to rise substantially by up to 66% compared to Case 1. As shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the increase in heating capacity exceeds the corresponding increase in power consumption, resulting in up to a 9% improvement in the system

compared with the cooling mode as the fresh air intake increases. However, regarding SOC, the trend similar the cooling mode. Regarding SOC, the trend is like cooling mode. As shown in

Figure 14, the total SOC consumption rises from 4.76% to 5.91% as the fresh air ratio increases, representing a maximum increase of 24% compared to Case 1. This result is a consequence of the increased compressor power consumption, which rises to handle to overall thermal load imposed by the increased fresh air intake.

4. Conclusions

This study analyzed the impacts of adjusting the core control variable, the fresh-to-recirculated air ratio on both IAQ and energy efficiency during the operation of an R744-based automotive HVAC system via system simulation.

The principal findings are as follows:

First, a clear and fundamental trade-off was confirmed regarding IAQ control. An increased fresh air intake ratio effectively dilutes indoor CO2 concentrations, but it simultaneously increases infiltration of external PM2.5. This indicates that the management goals for CO2 and PM2.5 are contradictory. Furthermore, a secondary effect was identified: increasing the blower flow rate not only accelerates CO2 dilution but also provides the ancillary benefit of partially suppressing PM2.5 infiltration via cabin pressurization.

Second, during cooling mode, increasing the fresh air intake for ventilation aggravates the thermal load, leading to a reduction in the system’s and a corresponding increase in total energy consumption. This demonstrates that, in cooling, the pursuit of better air quality incurs a direct penalty in terms of energy efficiency. As the recirculation ratio decreases, the inflow of warm and humid outdoor air into the cabin increases, resulting in a decrease in the system from 1.77 to 1.538, by 13% reduction and an increase in battery energy consumption from 4.74% to 7.42%, representing an approximate 57% increase.

Third, during heating mode, a non-intuitive trend was observed: despite the increase in the fresh air intake ratio, the system increases. This improvement was analyzed to be a result of enhanced heat transfer efficiency at the internal heat exchanger from the mixing of cold fresh air, which causes the rate of increase in heating capacity to surpass the rate of increase in compressor power consumption. However, due to the increase in the total heating load that had to be managed, the total energy consumption still rise as the fresh air intake ratio increases. In the heating mode, the system increases from 2.78 to 3.30, by approximately 9% increase as the recirculation ratio decreases. However, despite the improvement in , battery energy consumption increases from 4.76% to 5.91%, corresponding to an increase of approximately 24%.

The distinct trade-offs confirmed in this study offer actionable insights for practical engineering scenarios, particularly in the development of adaptive ventilation control strategies. The identified correlations between CO2 dilution, PM2.5 ingress, and energy consumption serve as a fundamental logic for designing real-time HVAC control algorithms. In practical applications, these findings can be integrated with sensor-based control systems that continuously monitor in-cabin pollutant levels and thermal parameters. By utilizing the trade-off relationships established here, the control logic can dynamically modulate the outdoor air-to-recirculation ratio. This optimization minimizes unnecessary fresh air intake while preventing CO2 accumulation and limiting PM2.5 intrusion, thereby achieving a balanced compromise between IAQ and energy efficiency. Consequently, this approach provides a viable framework for implementing intelligent climate control platforms in next-generation electric vehicles.

Note that this study focused on general driving conditions to analyze ventilation trade-offs. Specific operating modes driven by safety constraints, such as defrosting or rapid dehumidification, require distinct control logic and will be addressed in future studies. Finally, while this study validated the model using literature data, future works will focus on conducting independent experiments under broader operating conditions to further verify the model’s applicability and refine the proposed control strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and K.K.; methodology, J.C.; software, J.C., J.P. and S.B.; validation, J.C., J.P. and S.B.; formal analysis, J.C. and K.K.; investigation, J.C.; resources, K.K.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a funding for the Academic Research Program of Chungbuk National University (2025) and by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center), funded by the Ministry of Education(MOE) and the (Chungcheongbuk-do), Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-014-03).

Data Availability Statement

The simulation datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Nomenclatures

| Cin | In-cabin concentration of PM2.5, μg/m3 or CO2, ppm |

| Cout | Ambient concentration of PM2.5, μg/m3 or CO2, ppm |

| Qoa | Outside air ventilation airflow rate, m3/h |

| Qps | Outside air passive ventilation airflow rate, m3/h |

| Qrc | Recirculation ventilation airflow rate, m3/h |

| Qinf | Infiltration airflow rate, m3/h |

| Qbreath | Exhalation flow, m3/h |

| Vcabin | Cabin volume, m3 |

| Cbreath | Concentration of CO2 at breath, ppm |

| dPmech | Mechanical ventilation-controlled differential pressure, Pa |

| dPaero | Aerodynamic differential pressure on vehicle envelope surface, Pa |

| △Pinf | Differential pressure affecting infiltration, Pa |

| vdriving | Driving speed, km/h |

| Kf | Leakage flow coefficient |

| Kp | Aerodynamic pressure distribution coefficient |

| Frev | Reserve leakage flow coefficient factor |

| a | Coefficient for calculating dPmech |

| b | Coefficient for calculating dPaero |

| N | Number of occupant |

| n | Leakage pressure exponent |

| α | Particle penetration loss partitioning coefficient |

| β | Particle deposition coefficient, h−1 |

| η | Cabin air filter efficiency |

References

- Jiang, Y.; Si, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, F.; Lu, X.; Li, X.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z. The relationship between PM2.5 and eight common lung diseases: A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Toxics 2024, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Ye, L. Adverse effects of PM2.5 on cardiovascular diseases. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 37, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.S.; Stenstrom, M.K.; Zhu, Y. Ultrafine particle infiltration into passenger vehicles. Part I: Experimental evidence. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 38, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Stenstrom, M.K.; Zhu, Y. Ultrafine particle infiltration into passenger vehicles. Part II: Model analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 38, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudda, N.; Eckel, S.P.; Knibbs, L.D.; Sioutas, C.; Delfino, R.J.; Fruin, S.A. Linking in-vehicle ultrafine particle exposures to on-road concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 59, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, P.; Varghese, G.K. Simultaneous control of carbon dioxide and particulate matter inside a car cabin. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 133, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, J.; Manna, V.P.-L. The air quality paradigm inside car microenvironments: Balancing between PM2.5 and CO2 offsets. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE SENSORS Conference, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 25–28 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, R.A.; Markov, D.G.; Simova, I.; Velichkova, R.; Stankov, P. Accumulation of metabolic carbon dioxide (CO2) in a vehicle cabin. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 664, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirapuraj, P.; Minnoli, N.V.; Saranrai, M.; Thevaruban, K. Automated ventilation system for maintaining indoor CO2 concentration to reduce allergic and respiratory diseases: For rural area in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Pune, India, 27–29 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Jia, S.; Huang, L. Experimental comparison of R744 and R134a heat pump systems for electric vehicle application. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 121, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gu, J. The optimum high pressure for CO2 transcritical refrigeration systems with internal heat exchangers. Int. J. Refrig. 2005, 28, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Experimental study of R744 heat pump system for electric vehicle application. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 183, 116191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Nielsen, F.; Ekberg, L.; Dalenbäck, J.O. Size-resolved simulation of particulate matters and CO2 concentration in passenger vehicle cabins. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 45364–45379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matton, T.J.P. Simulation and Analysis of Air Recirculation Control Strategies to Control Carbon Dioxide Build-up Inside a Vehicle Cabin. Master’s thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 2015; p. 5269. Available online: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5269 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lesage, M.; Chalet, D.; Migaud, J.; Krautner, C. Optimization of air quality and energy consumption in the cabin of electric vehicles using system simulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luangprasert, M.; Vasithamrong, C.; Pongratananukul, S.; Chantranuwathana, S.; Pumrin, S.; De Silva, I.P.D. In-vehicle carbon dioxide concentration in commuting cars in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2017, 67, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhao, B. Research Progress on Thermal Comfort Evaluation in Vehicle Cab. Mech. Eng. Adv. 2025, 3, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |