Abstract

How to economically and effectively mobilize remaining oil and achieve carbon sequestration after water flooding in low-permeability, high-water-cut reservoirs is an urgent challenge. This study, focusing on Block Y of the Daqing Oilfield, employs numerical simulation to systematically reveal the synergistic influencing mechanisms of CO2 flooding and geological storage. A three-dimensional compositional model characterizing this reservoir was constructed, with a focus on analyzing the controlling effects of key geological (depth, heterogeneity, physical properties) and engineering (gas injection rate, gas injection volume, bottom-hole flowing pressure) parameters on the displacement and storage processes. Simulation results indicate that the low-permeability characteristics of Block Y effectively suppress gas channeling, enabling a CO2 flooding enhanced oil recovery (EOR) increment of 15.65%. Increasing reservoir depth significantly improves both oil recovery and storage efficiency by improving the mobility ratio and enhancing gravity segregation. Parameter optimization is key to achieving synergistic benefits: the optimal gas injection rate is 700–900 m3/d, the economically reasonable gas injection volume is 0.4–0.5 PV, and the optimal bottom-hole flowing pressure is 9–10 MPa. This study confirms that for Block Y and similar high-water-cut, low-permeability reservoirs, CO2 flooding is a highly promising replacement technology; through optimized design, it can simultaneously achieve significant crude oil production increase and efficient CO2 storage.

1. Introduction

Enhancing oil recovery (EOR) and addressing global climate change are two core challenges facing the energy sector today [1,2]. Carbon dioxide (CO2) flooding technology can effectively combine these two objectives, improving oilfield recovery while achieving geological storage of CO2, making it a highly promising green and low-carbon development technology [3]. This technology, through miscible/near-miscible interactions between CO2 and crude oil, effectively reduces oil viscosity, causes oil swelling, and improves the mobility ratio, thereby displacing remaining oil that is difficult to mobilize by water flooding [4,5,6].

However, the promotion and application of this technology still face numerous challenges, especially in the widely existing continental sedimentary, low-permeability, high-water-cut reservoirs in China [7]. After long-term water flooding development, such reservoirs have not only formed complex preferential flow channels with high water cut and highly dispersed remaining oil [8,9], but also face a unique “water-shielding effect”: the high water saturation in the formation physically hinders direct contact between CO2 and remaining oil, significantly delaying the miscible process and postponing production response, making adjustments using traditional development methods difficult [10,11]. Microscopic mechanistic studies further reveal that displacing residual oil surrounded by water films in nanopores by CO2 requires first disrupting the stable water film structure, a process that is complex [12].

Nevertheless, both theory and practice have proven that CO2 flooding remains an effective technology for enhancing oil recovery in such reservoirs. Its core mechanism lies in the fact that after dissolving in crude oil, CO2 causes it to swell, significantly reduces its viscosity, and can extract light hydrocarbons, thereby improving the mobility ratio and mobilizing remaining oil in small pores and blind ends that are difficult for water flooding to access [13,14]. Field pilot tests (e.g., in the Cainan Oilfield, H-26 block of Liaohe Oilfield, etc.) have also confirmed that through optimized design, production increase can still be achieved under high water-cut conditions [15,16]. To overcome the adverse effects of high water cut, various strategies have been proposed, including optimizing injection parameters and timing [17], adopting water-alternating-gas (WAG) injection [11], developing new technologies such as thickened supercritical CO2 to suppress gas channeling [18], and utilizing methods like non-steady-state huff-n-puff to mobilize remaining oil [19]. Furthermore, CO2 flooding in such reservoirs offers significant geological storage benefits. Injected CO2 can dissolve in large quantities into formation water or be fixed through mineral reactions, making the project a potential carbon mitigation pathway while enhancing oil recovery [20,21].

Previous research has enriched the understanding of the mechanisms and individual strategies for CO2 flooding in high-water-cut reservoirs. However, most studies have focused on early reservoir stages, medium-low water-cut periods, or miscible flooding conditions. Research on the integration of CO2 flooding and storage for reservoirs like Block Y in the Daqing Oilfield, which have entered the late high-water-cut stage, remains insufficient. In particular, studies that systematically compare and mechanistically analyze the synergistic influence mechanisms of key geological factors (such as depth, heterogeneity, and physical properties) and core engineering parameters (such as gas injection rate and bottom-hole flowing pressure) within the same framework on displacement efficiency and storage capacity require further deepening [22,23,24,25,26]. A quantitative understanding of this synergy is a key prerequisite for optimizing development plans and ensuring the technical and economic feasibility of projects [25,27].

Based on this, this study takes Block Y as the research object, aiming to systematically reveal the synergistic influencing mechanisms of CO2 flooding and storage in low-permeability reservoirs during the late high-water-cut stage through numerical simulation. The research first establishes a conceptual model characterizing the geological features of Block Y. It then delves into investigating the synergistic influence patterns of reservoir depth, heterogeneity, physical parameters (thickness, permeability, porosity), and injection-production parameters (gas injection rate, gas injection volume, shut-in gas-oil ratio, bottom-hole flowing pressure) on displacement efficiency and storage capacity. Ultimately, it aims to provide a theoretical basis and quantitative design guidance for implementing integrated CO2 flooding and storage schemes in Block Y and similar reservoirs.

2. Analysis of Geological Characteristics and Research Methodology

2.1. Structural and Physical Characteristics of Block Y

This study is based on a typical low-permeability, high-water-cut reservoir in Block Y (Table 1). The burial depth of this block ranges from 1033 to 1118 m, with an average porosity of 9.6% and an average permeability of 5.45 mD. The original oil saturation is 53%, characterizing it as a typical reservoir with low porosity, low permeability, and high water saturation. The main clay minerals in the reservoir include illite, kaolinite, chlorite, and illite/smectite mixed layer. Among these, chlorite is relatively abundant and stable, typically occurring as thin films coating grain surfaces. In contrast, smectite-group minerals (e.g., illite/smectite mixed-layer) exhibit strong water sensitivity and are prone to swelling and migration upon contact with water. During long-term water flooding, hydrodynamic scouring by injected water may cause physical migration and even dissolution of certain clay minerals (such as kaolinite and illite), thereby altering the micro-scale pore structure and affecting the flow capacity of the reservoir. The reservoir exhibits significant pinch-out development and strong intra-layer heterogeneity, leading to poor conventional water flooding performance and a rapid rise in water cut to 78.42%. Preferential flow channels have become dominant during water flooding production, necessitating an urgent shift in the development method to enhance oil recovery and production.

Table 1.

Basic Crude Oil Data for Block Y.

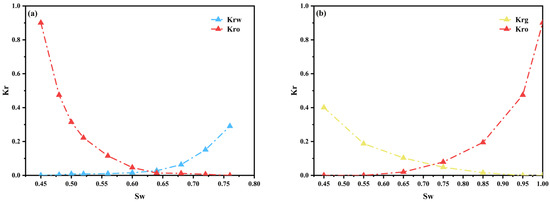

Based on the actual oil–gas and oil–water relative permeability data provided from the field, relative permeability curves are used to characterize the flow characteristics of Block Y. The corresponding relative permeability curves are shown in Figure 1. As indicated by the oil–water relative permeability curve, the irreducible water saturation is 0.45 and the residual oil saturation is 0.23.

Figure 1.

Oil–Water and Oil–Gas Relative Permeability Curves: (a) oil-water permeability curve; (b) oil-gas permeability curve.

2.2. Numerical Simulation Model Setup

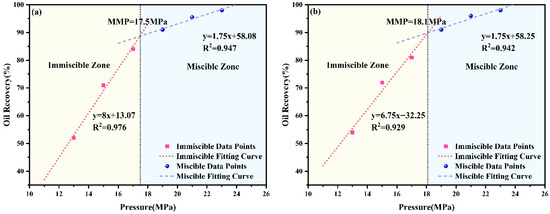

Based on the results of constant composition expansion experiments, differential liberation experiments, and gas injection swelling experiments, a fluid component model was established through fluid matching using the Winprop module of the CMG software. The experimental and simulation results are shown in Figure 2. The minimum miscibility pressure (MMP) determined by the slim-tube experiment is 17.5 MPa, while the MMP obtained from numerical simulation fitting is 18.1 MPa, resulting in a relative error of approximately 3.4%. This indicates that the established fluid component model accurately characterizes the phase behavior of the target fluids, providing a reliable physical property foundation for subsequent displacement simulations.

Figure 2.

Slim-tube experiment and numerical simulation results: (a) Experimental results; (b) Simulation results.

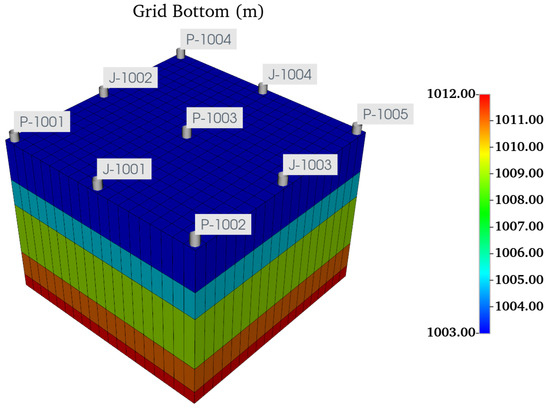

To focus on the core displacement mechanisms and the analysis of influencing factors, this study established a three-dimensional homogeneous conceptual model based on the key geological parameters of Block Y, which reflects its fundamental characteristics (Figure 3). It should be noted that this simplified model, constructed using average petrophysical properties, was deliberately adopted to isolate and quantify the individual effects of specific geological and engineering parameters. This approach allows for a clear revelation of their intrinsic influencing patterns, avoiding the coupled interference caused by actual complex heterogeneity. However, this also constitutes a limitation of the present study. As described in Section 2.1, the actual reservoir in Block Y features significant pinch-out development and strong intra-layer heterogeneity. Such complex spatial variability would significantly impact CO2 migration pathways, the formation of preferential channels, and the ultimate sweep efficiency. Therefore, the quantitative parameter optimization ranges obtained in this study primarily reflect underlying mechanistic trends. For future field application design, it is recommended to build upon the optimization principles identified here and further develop refined geological models that incorporate heterogeneous elements such as fractures, interlayers, and spatial property distributions. Conducting more realistic simulations based on such models would enhance the operability of development plans.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the conceptual model grid.

The GEM compositional simulator within the CMG numerical simulation software was used for modeling, as it can accurately describe the complex phase behavior between CO2 and crude oil.

- (1)

- Grid System: The model employs a Cartesian grid system with grid dimensions of 19 × 19 × 5, resulting in a total of 1805 grid blocks. The grid size is set to 20 m × 20 m in the X and Y directions. The layer thickness in the Z direction was set according to different simulation schemes to represent variations in reservoir thickness.

- (2)

- Reservoir and Fluid Parameters: The baseline parameters for the model are shown in Table 2. The relative permeability curves used the measured oil–water and oil–gas relative permeability data from Block Y to accurately characterize the multiphase flow behavior.

- (3)

- Well Pattern and Boundary Conditions: A five-spot well pattern was adopted, with 4 injection wells and 5 production wells. The distance between injection and production wells is 240 m. The model boundaries are set as closed to simulate an independent development unit.

Table 2.

Baseline Parameters of the Conceptual Model.

Table 2.

Baseline Parameters of the Conceptual Model.

| Parameter Name | Value | Parameter Name | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Grids | 19 × 19 × 5 | Production Pressure Differential | 3.5 MPa |

| Grid Dimensions | 20 m × 20 m | Initial Water Saturation | 0.45 |

| Porosity | 9.4% | Formation Temperature | 56 °C |

| Permeability (X, Y direction) | 5 mD | Initial Oil Saturation | 0.53 |

| Permeability (Z direction) | 0.5 mD | Minimum Miscibility Pressure (MMP) | 17.5 MPa |

| Effective Thickness | 11 m | Initial Reservoir Pressure | 12 MPa |

2.3. Simulation Workflow

To simulate the actual development process of switching to CO2 flooding during the high water-cut stage, the numerical simulation study followed the workflow below:

- (1)

- Initialization: The model was initialized to the original reservoir pressure (12 MPa) of Block Y.

- (2)

- Water Flooding Stage: Water flooding was first simulated. All production wells operated at a constant liquid production rate, and injection wells injected at a constant water injection rate, until the field’s comprehensive water cut reached 80%. This simulated the water flooding history and established the remaining oil distribution at the high water-cut stage.

- (3)

- CO2 Flooding Stage: When the water cut reached the 80% threshold for switching, water injection was stopped, and CO2 injection began at the injection wells. During this stage, different injection-production parameters (such as gas injection rate and bottom-hole flowing pressure) were applied to study the effects of various factors. Production wells operated under either a constant bottom-hole flowing pressure or a constant liquid production rate. The simulation was terminated when the economic limit (a water cut of 98% or a gas-oil ratio of 2500 m3/m3) was reached.

Through this workflow, the development performance of pure water flooding versus subsequent CO2 flooding can be systematically compared, and the impact of various factors on the EOR increment and CO2 storage efficiency can be quantitatively analyzed.

3. Analysis of Influencing Factors

3.1. Influence of Reservoir Depth

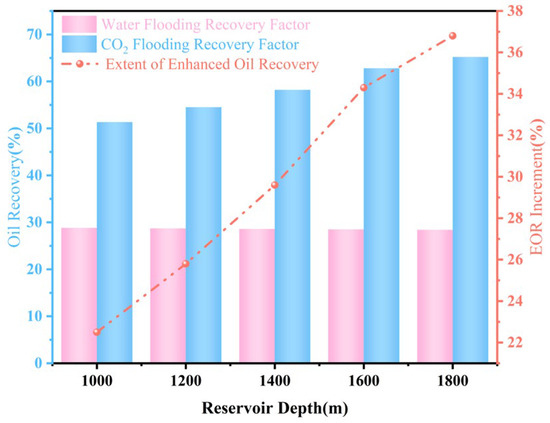

Reservoir burial depth directly determines the formation temperature and pressure systems, making it a key factor influencing the effectiveness of CO2 flooding and storage. To systematically study its influence, this study established numerical simulation models based on the geological background of Block Y, setting up five different top-depth scenarios: 1000 m, 1200 m, 1400 m, 1600 m, and 1800 m. The development scheme switched from water flooding to CO2 flooding when the water cut reached 80%, and the displacement and storage performance were systematically evaluated.

Simulation results (Figure 4) show that as the reservoir top depth increases, the pure water flooding recovery factor slightly decreases from 28.85% (1000 m) to 28.44% (1800 m), indicating a limited impact of depth on water flooding performance. However, after switching to CO2 injection, both the ultimate recovery factor and the EOR increment significantly improve. When the top depth increases from 1000 m to 1800 m, the gas injection recovery factor increases from 51.27% to 65.18%, and the EOR increment increases from 22.42% to 36.74%. On average, for every 200 m increase in burial depth, the EOR increment increases by approximately 3–5%.

Figure 4.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

The above trend is primarily attributed to the corresponding increase in formation temperature and pressure with greater burial depth. Higher formation pressure helps reduce CO2 viscosity and improves the mobility ratio between CO2 and crude oil, thereby enhancing displacement efficiency. Simultaneously, the increased viscosity difference and gravity segregation effect work together, promoting the accelerated vertical migration of CO2 and effectively expanding the vertical sweep efficiency, ultimately significantly improving oil recovery. The simulation results confirm that even at a burial depth of 1000 m, CO2 flooding can achieve a significant EOR increment of 22.42%, indicating that the current burial depth conditions of Block Y are very suitable for CO2 flooding development.

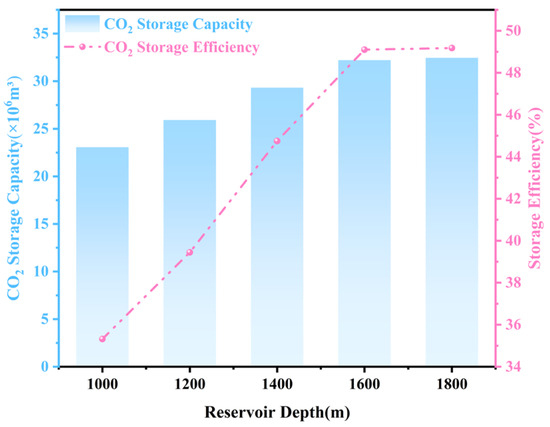

Reservoir depth also has a significant impact on the CO2 storage capacity. As shown in Figure 5, as the top depth increases from 1000 m to 1800 m, the cumulative CO2 storage increases from 23.10 × 106 m3 to 32.50 × 106 m3, and the storage efficiency increases from 35.40% to 49.25%, showing a clear growth trend.

Figure 5.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

The improvement in storage performance primarily benefits from the higher formation pressure and temperature in deeper reservoirs. The high-temperature and high-pressure environment, on one hand, increases CO2 density, facilitating its existence in a supercritical state, thereby enhancing the storage potential per unit volume of rock. On the other hand, the decrease in CO2 viscosity caused by the temperature increase makes it more mobile within the reservoir, allowing it to access more pore space, thus expanding the macroscopic storage volume.

Reservoir depth exerts a significantly positive influence on both CO2 flooding and geological storage. For the displacement process, it primarily enhances oil recovery by improving the mobility ratio and strengthening gravity segregation. For the storage process, it improves storage efficiency by increasing the storage density of CO2 and expanding the sweep volume. This effect highlights the importance of the formation pressure and temperature system: with increasing burial depth, the higher formation pressure not only improves CO2 mobility, but the combined effect of elevated pressure and temperature leads to increased CO2 density and decreased viscosity, which are key to enhancing the storage capacity per unit volume and the macroscopic sweep efficiency [28,29,30]. Therefore, based on the factor of reservoir depth, Block Y possesses favorable geological conditions for implementing synergistic CO2 flooding and storage projects.

3.2. Influence of Vertical Heterogeneity

Reservoir vertical heterogeneity, specifically the ratio of vertical to horizontal permeability (KV/Kh), is a key geological factor controlling vertical fluid migration and displacement efficiency. This study systematically analyzed the impact of vertical heterogeneity on CO2 flooding and storage effects by setting up five scenarios with KV/Kh ratios ranging from 0.1 to 0.5, while maintaining a constant horizontal permeability of 5 mD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Basic Data for Heterogeneity Models.

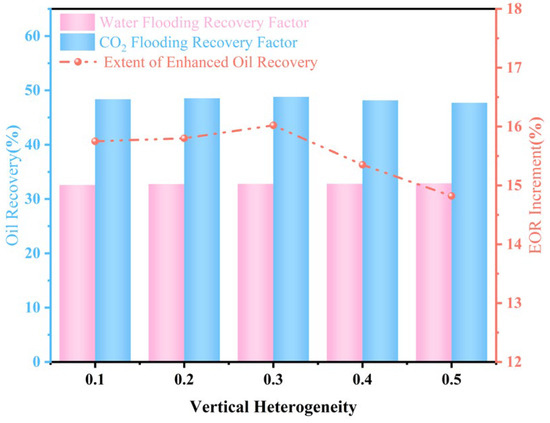

Simulation results (Figure 6) show that vertical heterogeneity has minimal impact on the water flooding recovery factor, which remains stable between 32.60% and 32.88%. However, the development performance after switching to CO2 flooding shows a clear non-linear relationship with the KV/Kh ratio. When the KV/Kh ratio increases from 0.1 to 0.3, the gas injection recovery factor increases from 48.35% to 48.80%, and the EOR increment increases from 15.81% to 16.00%. But when the KV/Kh ratio further increases to 0.5, the gas injection recovery factor and EOR increment decrease to 47.70% and 14.82%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

This trend of initial increase followed by a decrease is primarily controlled by two competing mechanisms:

- (1)

- Moderate vertical connectivity favors gravity segregation: When the KV/Kh ratio is low to moderate (e.g., 0.1–0.3), the injected CO2 can overcome certain flow resistance and migrate upward under buoyancy, effectively expanding the vertical sweep volume and mobilizing oil in the upper, lower-permeability layers, thereby improving displacement efficiency.

- (2)

- Excessive vertical connectivity exacerbates gas channeling: When the KV/Kh ratio is too high (e.g., >0.3), the preferential flow channels formed during long-term water flooding become more developed. Injected CO2 will preferentially and rapidly break through along these high-permeability channels, causing a sharp rise in the gas-oil ratio (GOR) at production wells and leading to gas channeling. This shortens the effective interaction time between CO2 and crude oil, resulting in decreased macroscopic displacement efficiency. The KV/Kh ratio in Block Y is approximately 0.1. Simulation results show that under this condition, a high EOR increment of 15.81% can be achieved, indicating that its current geological conditions are favorable for implementing CO2 flooding.

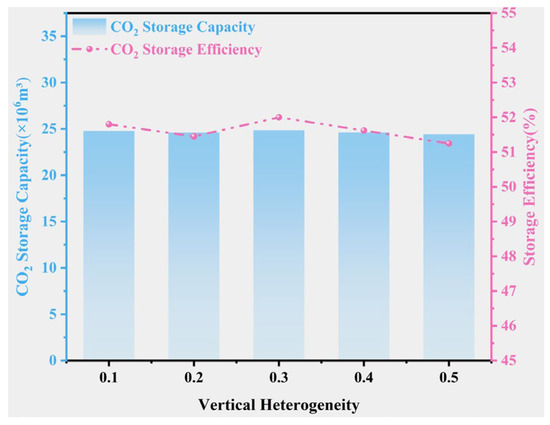

The influence of vertical heterogeneity on CO2 storage follows a pattern similar to its impact on oil displacement. As shown in Figure 7, as the KV/Kh ratio increases from 0.1 to 0.5, the CO2 storage efficiency fluctuates between 51.25% and 52.00%, peaking at a ratio of 0.3.

Figure 7.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

Under conditions of moderate heterogeneity (KV/Kh = 0.3), the reservoir possesses channels conducive to the macroscopic migration of CO2 without forming extreme preferential pathways. This allows CO2 to enter the reservoir pore space more uniformly and achieve effective trapping in various forms, such as free phase and dissolution, resulting in the highest storage efficiency. When the heterogeneity is too strong, gas channeling leads to a significant amount of CO2 being produced prematurely, reducing its effective retention volume in the reservoir and thus lowering storage efficiency.

Vertical heterogeneity is a key factor influencing the displacement and storage behavior of CO2 in high-water-cut reservoirs. There exists an optimal range for the KV/Kh ratio (approximately 0.3 in this study). Within this range, it is possible to utilize gravity segregation to expand the sweep volume while effectively suppressing gas channeling, thereby optimizing both oil displacement and storage effects. For Block Y (KV/Kh ≈ 0.1), its relatively low vertical connectivity, while somewhat limiting the positive effects of gravity segregation, effectively suppresses the risk of gas channeling. Overall, it still possesses good potential for CO2 flooding and storage applications.

3.3. Influence of Reservoir Thickness

Reservoir thickness directly affects the vertical migration space for fluids and the sweep efficiency of injected agents, making it an important parameter for optimizing CO2 flooding and storage schemes. This study systematically evaluated the impact of reservoir thickness on development performance by setting up conceptual models with five different thicknesses, ranging from 3 m to 19 m.

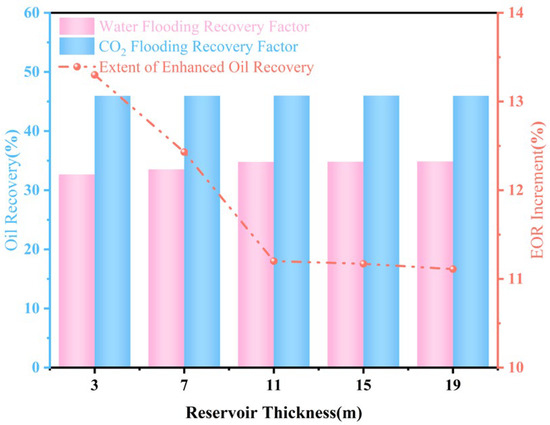

Numerical simulation results (Figure 8) reveal contrasting trends in the impact of reservoir thickness on water flooding versus CO2 flooding performance. As the reservoir thickness increases from 3 m to 19 m, the water flooding recovery factor steadily rises from 32.65% to 34.85%. This is primarily because greater thickness provides more space for vertical migration of the injected water, helping to improve the vertical sweep efficiency.

Figure 8.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

However, the ultimate recovery factor after switching to CO2 flooding follows a different pattern. The gas injection recovery factor remains relatively stable across the different thickness models, at approximately 45.95%. This phenomenon leads to a significant decrease in the EOR increment as thickness increases, dropping from 13.30% (3 m) to 11.11% (19 m).

The core mechanism behind this phenomenon is gravity override. In thicker reservoirs, the injected CO2, which has a much lower density than oil and water, rapidly migrates to the top of the reservoir under strong gravity segregation after injection, forming a preferential gas flow channel along the top. This leads to early gas breakthrough, preventing CO2 from effectively displacing the remaining oil in the middle and lower sections of the reservoir, severely limiting its vertical sweep efficiency [31]. Consequently, although thick reservoirs have a higher base water flooding recovery, the additional oil recovery potential from CO2 flooding is reduced due to the limited sweep volume. For Block Y (with a thickness of about 10 m), the EOR increment is 11.20%, indicating that while this thickness condition is not optimal, CO2 flooding can still be effectively implemented.

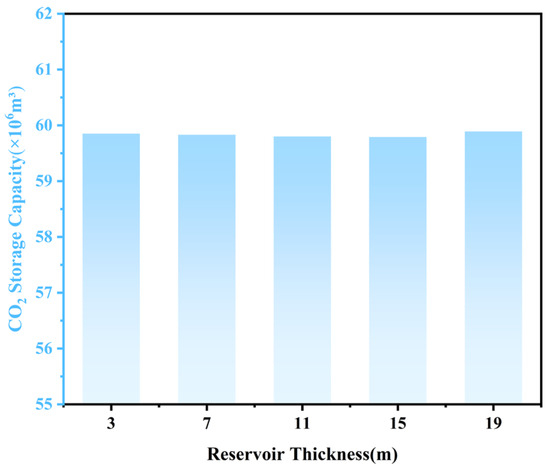

Unlike its effect on oil displacement, reservoir thickness has a negligible impact on CO2 storage efficiency. Simulation results (Figure 9) show that when the reservoir thickness varies from 3 m to 19 m, the CO2 storage efficiency remains stable at around 59.83%, with an extremely small range of fluctuation (59.79–59.89%).

Figure 9.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

This result indicates that the CO2 storage efficiency is primarily determined by its interaction with formation fluids (oil, water), such as dissolution, and the physical trapping capacity of the rock, processes that are relatively independent per unit volume [32]. Although a thick layer provides a larger absolute storage volume, gravity override causes CO2 to be concentrated at the top, resulting in an uneven vertical distribution and no significant increase in the effective storage amount per unit volume [33]. Therefore, the overall storage efficiency shows little sensitivity to thickness changes.

The influence of reservoir thickness on CO2 flooding and storage is asymmetric:

- (1)

- For oil displacement, thinner reservoirs help suppress gravity override, improve CO2 sweep efficiency, and thus achieve a higher EOR increment.

- (2)

- For storage, variations in thickness have little effect on the final storage efficiency, which is mainly controlled by other geological and engineering factors.

In summary, from the perspective of enhancing oil recovery, thinner reservoirs (e.g., <11 m) are more conducive to leveraging the technical advantages of CO2 flooding. The reservoir thickness of approximately 10 m in Block Y falls within a favorable range, enabling effective oil production increase while ensuring a high CO2 storage efficiency.

3.4. Influence of Reservoir Permeability

Reservoir permeability is a key physical property parameter controlling fluid flow capacity, and it has a decisive effect on the sweep efficiency and breakthrough behavior of the displacing agent. This study systematically analyzed the impact of reservoir permeability on the development performance of switching to CO2 flooding during the high water-cut stage by setting up five permeability scenarios ranging from 5 mD to 25 mD.

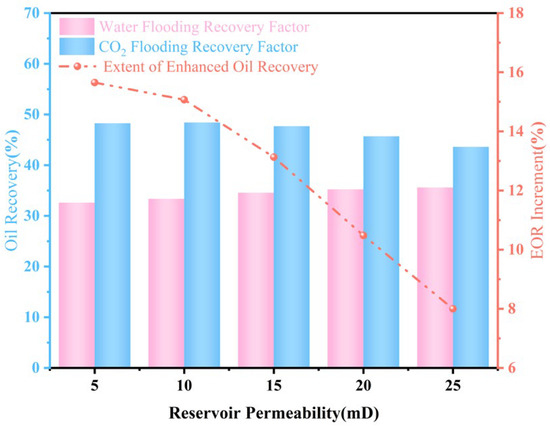

Simulation results (Figure 10) indicate that reservoir permeability has distinctly different effects on water flooding versus CO2 flooding performance. As permeability increases from 5 mD to 25 mD, the water flooding recovery factor steadily improves from 32.60% to 35.60%. This is primarily because higher permeability provides better flow channels for the injected water, thereby expanding the water flood sweep volume and improving water flooding performance.

Figure 10.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

However, the effectiveness of CO2 flooding shows the opposite trend. As permeability increases, the gas injection recovery factor significantly decreases from 48.25% (5 mD) to 43.60% (25 mD), and the corresponding EOR increment also drops sharply from 15.65% to 8.00%.

The core mechanism behind this contrasting phenomenon lies in the preferential channeling effect and gas mobility control. In high-permeability, high-water-cut reservoirs, long-term water flooding has already established stable water-flow preferential channels. When switching to the injection of very low-viscosity CO2, the gas will preferentially and rapidly channel through these high-permeability pathways. This causes the gas-oil ratio (GOR) at production wells to rise sharply within a short period, quickly reaching the economic limit and leading to well shut-in. This severe gas channeling prevents CO2 from effectively displacing the remaining oil in the matrix, greatly reducing the effective utilization of the gas and the macroscopic displacement efficiency. The average permeability of Block Y is 5.45 mD. Simulation results show that under these low-permeability conditions, a high EOR increment of 15.65% can be achieved, indicating that its permeability conditions are very favorable for implementing CO2 flooding.

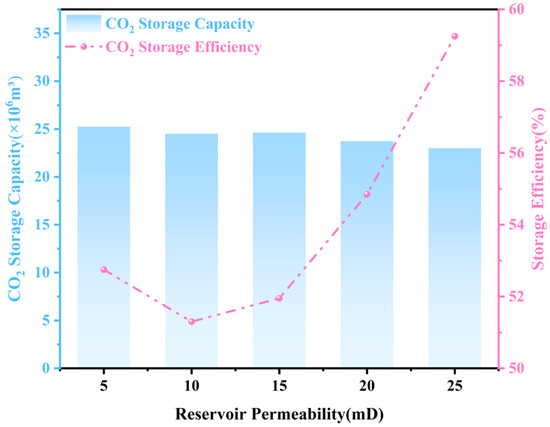

The influence of reservoir permeability on CO2 storage capacity follows a trend consistent with its impact on oil displacement. As shown in Figure 11, as permeability increases from 5 mD to 25 mD, the CO2 storage capacity decreases from 25.25 × 106 m3 to 23.00 × 106 m3, and the storage efficiency also shows a fluctuating downward trend.

Figure 11.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

The decline in storage performance is mainly due to gas channeling shortening the effective residence time of CO2 in the reservoir. In low-permeability reservoirs, the flow resistance for CO2 is greater, and its migration velocity is slower. This prolongs its contact time with crude oil and formation water, promoting dissolved phase storage (in oil and water) and allowing it to fill the pore space in a more controlled manner, thereby achieving higher storage capacity. In contrast, in high-permeability reservoirs, the rapid channeling of CO2 leads to its premature production, reducing its effective volume retained in the reservoir and its residence time. Although the storage efficiency for the 25 mD scenario in the corresponding table might appear relatively high, this could be because gas channeling drastically reduces the total amount injected. The reduction in the denominator (amount injected) exceeds that of the numerator (amount stored), resulting in a seemingly higher calculated storage efficiency, but this cannot mask the fact that its absolute storage capacity is the lowest.

Reservoir permeability exerts a significant and consistent influence on both CO2 flooding and storage: lower permeability conditions are more favorable for achieving synergistic benefits. The simulation results of this study clearly reveal the unique advantage of low-permeability reservoirs (~5 mD) in this technology. Contrary to conventional understanding, lower permeability effectively suppresses CO2 channeling, prolongs its contact time with crude oil, and creates conditions for sufficient phase behavior interactions (such as oil swelling and viscosity reduction), thereby significantly enhancing both displacement efficiency and storage capacity [34]. This finding confirms, at the reservoir scale, the natural controlling effect of low-permeability conditions on CO2 mobility, which aligns with the experimental observations of Zhang et al. 2025 in tight sandy conglomerates [35]. Therefore, as a typical low-permeability reservoir, the physical properties of Block Y provide a natural advantage for implementing CO2 flooding and storage.

3.5. Influence of Reservoir Porosity

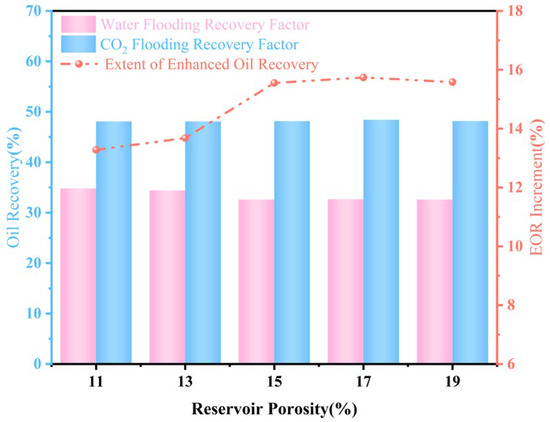

Reservoir porosity determines the fluid storage space and the rock’s pore structure, making it a key parameter affecting storage capacity and flow characteristics. This study thoroughly analyzed its impact on CO2 flooding and storage performance in high-water-cut reservoirs by setting up five different porosity scenarios ranging from 11% to 19%

Simulation results (Figure 12) reveal different influence patterns of porosity on water flooding versus CO2 flooding performance. As porosity increases from 11% to 19%, the water flooding recovery factor decreases from 34.80% to 32.60%. This phenomenon may stem from the more complex pore structure and stronger microscopic heterogeneity in high-porosity reservoirs, which increase the blind pore volume inaccessible to water flooding, thereby reducing macroscopic sweep efficiency.

Figure 12.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

However, the EOR increment after switching to CO2 flooding improves significantly with increasing porosity. When porosity increases from 11% to 17%, the EOR increment rises from 13.28% to 15.74%. This indicates that under higher porosity conditions, CO2 flooding can more effectively mobilize the remaining oil that is difficult to access by water flooding.

The superior performance of CO2 flooding in higher porosity reservoirs is primarily attributed to the unique mechanisms of CO2:

- (1)

- Enhanced Diffusion and Mass Transfer Capacity: CO2 molecules have a high diffusion coefficient. In higher porosity reservoirs with more developed pore structures, CO2 can diffuse more effectively into tiny pores and blind ends that water flooding cannot reach, interact with the remaining oil therein (causing viscosity reduction and swelling), and displace it [32].

- (2)

- Improved Mobility Ratio: CO2 injection improves the mobility ratio between the displacing and displaced phases, which is particularly important for enhancing sweep efficiency in reservoirs with complex pore structures [36].

The porosity of Block Y is 9.6%, slightly lower than the minimum value simulated here. The simulation trend suggests that despite the relatively low porosity, CO2 flooding can still achieve a significant EOR effect. If measures can be taken to improve the pore structure in the near-wellbore zone through reservoir stimulation, further enhancement of development performance can be expected.

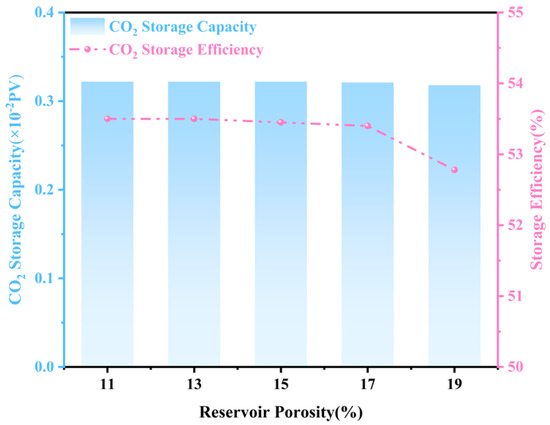

Unlike its effect on oil displacement, the influence of porosity on CO2 storage efficiency is relatively limited and shows a slight negative correlation. As shown in Figure 13, as porosity increases from 11% to 19%, the CO2 storage efficiency slowly decreases from 53.50% to 52.78%, with a variation of less than 1%.

Figure 13.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

The reasons for the slight decrease in storage efficiency with increasing porosity may include:

- (1)

- Changes in Pore Structure: An increase in porosity may be accompanied by an increase in pore throat radii and enhanced pore connectivity. This could, in turn, weaken the capillary trapping of CO2, making some CO2 more susceptible to escaping during subsequent water flooding or pressure fluctuations [37].

- (2)

- Relative Dissolution Space: Although the absolute pore volume increases, the volumes of crude oil and formation water also increase correspondingly. The amount of CO2 dissolved in the fluids depends on the fluid volume, while the free-phase storage depends on the pore space. The difference in the growth proportions of these two components might lead to minor changes in the overall storage efficiency [35].

Nonetheless, the storage efficiency for all scenarios remains above 52%, indicating that CO2 can achieve efficient storage across the studied porosity range. The porosity conditions in Block Y fully meet the requirements for CO2 storage.

The mechanisms by which reservoir porosity influences CO2 flooding and storage are different:

- (1)

- For oil displacement, higher porosity, although potentially unfavorable for water flooding, provides a more favorable space for CO2 to utilize its diffusion and mass transfer advantages, resulting in a higher EOR increment.

- (2)

- For storage, variations in porosity over a wide range have a negligible impact on the final storage efficiency, which remains consistently high.

In summary, CO2 flooding technology is particularly suitable for developing high-water-cut reservoirs with medium to high porosity but low water flooding efficiency, enabling synergy between oil displacement and storage. For Block Y, although its porosity is relatively low and not the ideal condition, CO2 flooding can still effectively enhance oil recovery and achieve stable geological storage.

3.6. Influence of Gas Injection Rate

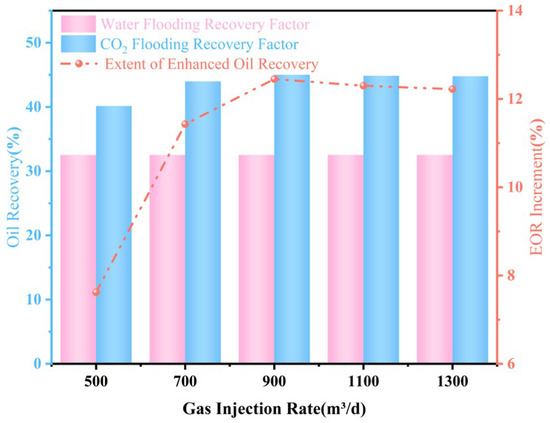

The gas injection rate is a key engineering parameter that regulates the flow regime, sweep volume, and interaction time with crude oil for CO2 in the reservoir. To determine the reasonable gas injection rate for switching to CO2 flooding in high-water-cut reservoirs, this study simulated five gas injection rate scenarios ranging from 500 m3/d to 1300 m3/d.

Numerical simulation results (Figure 14) clearly indicate that there is an optimal range for the gas injection rate concerning CO2 flooding recovery. When the gas injection rate increases from 500 m3/d to 900 m3/d, the gas injection recovery factor significantly improves from 40.15% to 45.00%, and the EOR increment increases from 7.62% to 12.45%. However, when the gas injection rate further increases to 1300 m3/d, the recovery factor and EOR increment slightly decrease and then stabilize.

Figure 14.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

This variation trend results from the competition between two effects:

- (1)

- Positive Effect (Enhancing Sweep and Drive Pressure): At lower injection rates (e.g., 500–900 m3/d), increasing the rate allows for a quicker establishment of an effective drive pressure system, overcoming capillary forces, enabling CO2 to enter medium and low-permeability pathways, and utilizing gravity segregation to expand the vertical sweep volume.

- (2)

- Negative Effect (Aggravating Gas Channeling and Viscous Fingering): When the injection rate is too high (e.g., >900 m3/d), the velocity of CO2 becomes excessive, intensifying viscous fingering between CO2 and crude oil. This causes CO2 to bypass large volumes of oil, forming channeling directly through high-permeability pathways. The gas-oil ratio (GOR) at production wells rises rapidly, shortening the effective oil displacement time and thus reducing displacement efficiency.

Therefore, approximately 900 m3/d is the optimal gas injection rate under this conceptual model. This provides crucial operational parameter guidance for the field implementation in Block Y.

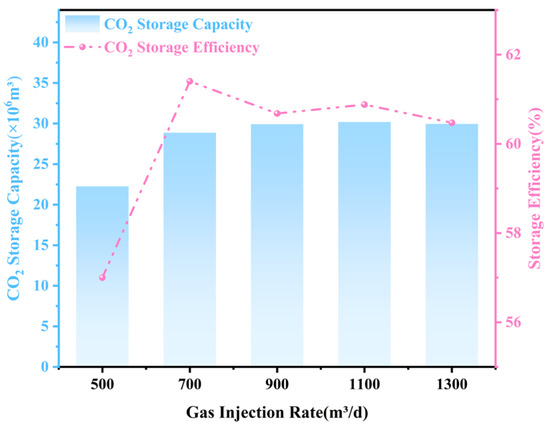

The influence of the gas injection rate on CO2 storage efficiency is highly synergistic with its impact on oil displacement. As shown in Figure 15, both the CO2 storage capacity and storage efficiency also exhibit a characteristic of initially increasing rapidly and then stabilizing as the injection rate increases.

Figure 15.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

At lower rates (500–700 m3/d), increasing the injection rate significantly raises the volume of CO2 residing within the reservoir and allows more sufficient time for it to dissolve into the formation fluids; thus, both storage efficiency and capacity increase simultaneously. Near the optimal rate (700–900 m3/d), the storage efficiency peaks. Thereafter, although further increasing the injection rate allows more CO2 to be injected (storage capacity increases slightly), the proportion of CO2 being produced also increases concurrently due to aggravated channeling, preventing further improvement or even causing a slight decrease in storage efficiency.

The gas injection rate exhibits a distinct optimal range (700–900 m3/d) for both CO2 flooding and storage. An excessively low rate fails to establish an effective drive pressure system to expand the sweep volume, while an excessively high rate triggers severe viscous fingering and gas channeling, causing premature CO2 breakthrough. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in high-water-cut reservoirs that have undergone long-term water flushing and preferential channel development [26,38], significantly reducing both CO2 utilization efficiency and storage efficiency. Therefore, for Block Y, controlling the gas injection rate within this reasonable interval is a key engineering measure for achieving the synergistic optimization of the dual objectives of oil displacement and storage.

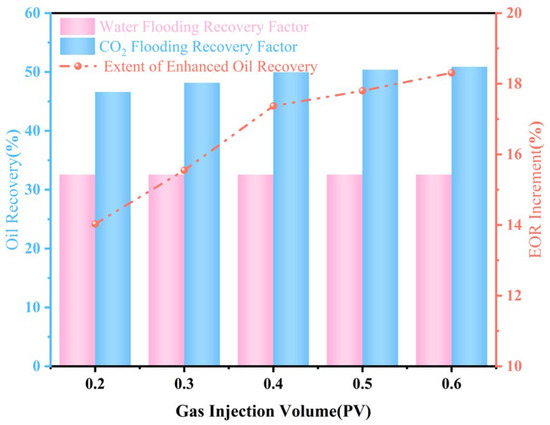

3.7. Influence of Gas Injection Volume

The gas injection volume, expressed as Pore Volume (PV) multiples, directly determines the total volume of CO2 injected into the reservoir and is a macro-level engineering parameter affecting the displacement process and storage scale. This study simulated the impact of injecting CO2 volumes ranging from 0.2 PV to 0.6 PV on development performance.

Simulation results (Figure 16) indicate that as the cumulative gas injection volume increases, the ultimate recovery factor and EOR increment from CO2 flooding continuously improve. When the gas injection volume increases from 0.2 PV to 0.6 PV, the gas injection recovery factor steadily grows from 46.60% to 50.88%, and the EOR increment also increases from 14.03% to 18.31%.

Figure 16.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

This growth trend primarily stems from two mechanisms:

- (1)

- Expanding the Sweep Volume: A larger injection volume means more CO2 reaches deeper into the reservoir, displacing remaining oil from more distant areas and gradually entering medium and low-permeability zones, thereby continuously expanding both macroscopic and microscopic sweep efficiency.

- (2)

- Maintaining Reservoir Energy and Sustained Interaction: Continuous CO2 injection effectively replenishes reservoir energy, maintaining a higher formation pressure. This not only provides more time for sufficient interaction between CO2 and crude oil (viscosity reduction, swelling, extraction) but also helps effectively drive the mobilized oil towards the production wells.

It is noteworthy that after the gas injection volume exceeds 0.4 PV, the rate of increase in the recovery factor (the slope of the curve) noticeably slows down. This indicates that the marginal benefit gradually decreases with increasing injection volume. CO2 injected in the later stages may be used more to compensate for gas channeling losses and maintain pressure, rather than directly displacing new oil.

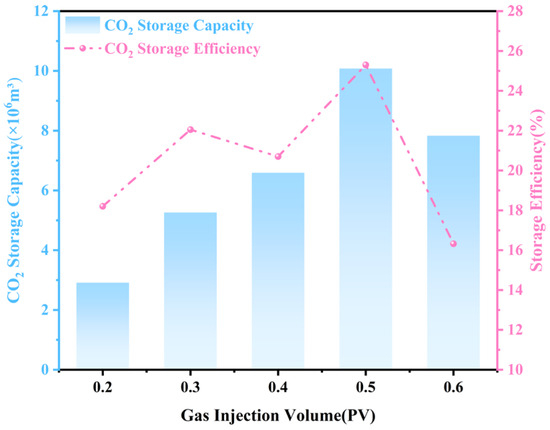

The influence of gas injection volume on CO2 storage exhibits a complex, non-monotonic characteristic. As shown in Figure 17, as the gas injection volume increases from 0.2 PV to 0.5 PV, the CO2 storage capacity increases significantly from 2.91 × 106 m3 to 10.08 × 106 m3, and the storage efficiency also improves from 18.20% to 25.30%.

Figure 17.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

However, when the injection volume reaches 0.6 PV, although the absolute storage capacity remains high, the storage efficiency drops sharply to 16.29%. This phenomenon reveals a critical turning point:

- (1)

- At low to medium injection volumes (0.2–0.5 PV), the injected CO2 is primarily effectively trapped in the reservoir (through dissolution, residual phase, and structural trapping).

- (2)

- When the injection volume is too high (0.6 PV), the storage capacity of the reservoir gradually approaches saturation. The additionally injected CO2 cannot be effectively retained. Simultaneously, the large injection volume exacerbates the development of gas channeling pathways, causing a significant portion of the injected CO2 to be produced. This results in the rate of increase in produced gas volume surpassing the rate of increase in stored gas volume, ultimately leading to a substantial decline in storage efficiency.

Simulation results indicate that the impact of cumulative gas injection volume on oil displacement and storage requires trade-offs. For enhanced oil recovery, when the injection volume exceeds 0.4 PV, the growth rate of the recovery factor slows significantly, implying that the marginal benefit of incremental oil production begins to decline. For CO2 storage, both the storage efficiency and capacity peak at 0.5 PV; beyond this point, they decrease sharply due to exacerbated gas channeling. Therefore, if the economic objective is solely crude oil production, controlling the injection volume around 0.4 PV may be more economically efficient. However, if the project also aims for carbon emission reduction and can obtain corresponding carbon tax credits or carbon trading income, the climate benefits from injecting and storing more CO2 translate into economic value. In this context, increasing the cumulative injection volume to 0.5 PV is expected to maximize the comprehensive benefits of both oil displacement and storage. The specific optimal value requires detailed Net Present Value (NPV) analysis based on local energy prices, CO2 costs, and carbon policies.

In project design, blindly pursuing a large injection volume is not advisable. Numerical simulation studies combined with economic evaluation should be conducted to determine a reasonable gas injection volume that balances both recovery targets and storage efficiency. For Block Y, it is recommended to control the cumulative gas injection volume within the range of 0.4–0.5 PV to achieve synergistic optimization of oil displacement and storage.

3.8. Influence of Shut-In Gas-Oil Ratio

The shut-in Gas-Oil Ratio (GOR) determines how long a production well continues to operate after gas breakthrough occurs. It is a key development decision parameter for balancing crude oil production against gas recycling and wastage. This study simulated five shut-in GOR scenarios ranging from 1000 m3/m3 to 3000 m3/m3.

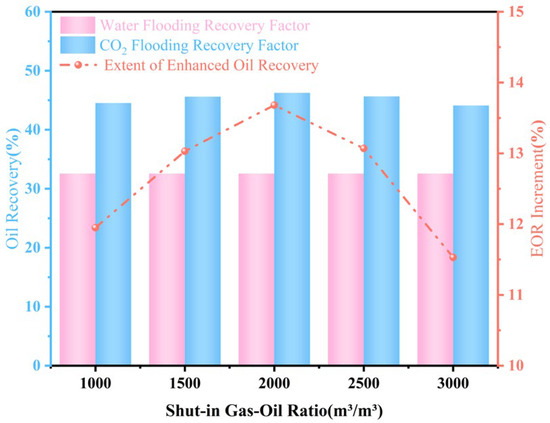

Simulation results (Figure 18) indicate that there is a clear optimal value for the shut-in GOR concerning CO2 flooding recovery. As the shut-in GOR increases from 1000 m3/m3 to 2000 m3/m3, the gas injection recovery factor improves from 44.52% to 46.25%, and the EOR increment increases from 11.95% to 13.68%. However, when the shut-in GOR is further increased to 3000 m3/m3, both the recovery factor and EOR increment decrease.

Figure 18.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

This trend of initial increase followed by a decrease results from the balance between gas control and oil production:

- (1)

- Limitation of an overly low GOR (e.g., 1000 m3/m3): An excessively restrictive GOR limit causes production wells to be shut in at the very early signs of gas breakthrough. While this minimizes CO2 production, it also prematurely abandons the oil yet to be displaced in the drainage area controlled by the well, thus limiting the potential for recovery improvement.

- (2)

- Balance at the optimal GOR (e.g., 2000 m3/m3): A moderate shut-in GOR allows a production well to continue operating for some time after gas breakthrough. This enables subsequently injected CO2 to more fully displace the remaining oil further from the wellbore. Simultaneously, by re-injecting the produced gas, the project’s overall economy can still be maintained, thereby maximizing the recovery factor.

- (3)

- Wastage at an overly high GOR (e.g., 3000 m3/m3): An excessively lenient limit, while extending production time, leads to significant inefficient recycling of CO2. The gas forms a “short-circuit” in high-permeability channels, failing to effectively displace oil, while substantially increasing lifting and separation costs. Ultimately, this degrades the net oil increase and leads to a lower recovery factor.

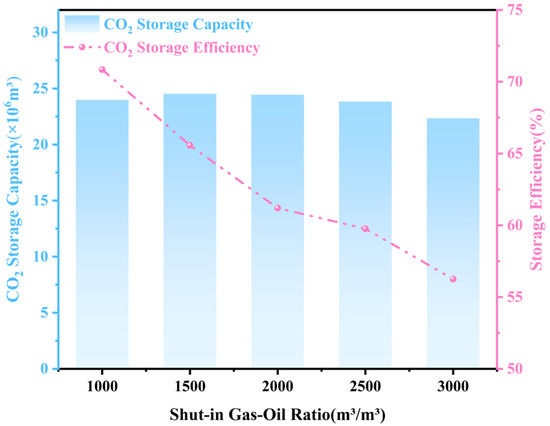

The influence of the shut-in GOR on CO2 storage shows a very clear trend, as depicted in Figure 19. As the shut-in GOR increases from 1000 m3/m3 to 3000 m3/m3, the CO2 storage capacity decreases from 23.98 × 106 m3 to 22.34 × 106 m3, and the storage efficiency drops significantly from 70.85% to 56.25%.

Figure 19.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

This represents a direct trade-off: a higher shut-in GOR means allowing more of the injected CO2 to be produced. Although the cumulative injection volume might be larger at a high GOR, the volume of gas that is produced and recycled also increases dramatically, leading to a continuous decline in the proportion of CO2 net stored underground (storage efficiency). From a purely storage efficiency perspective, a stricter shut-in policy (lower shut-in GOR) is more advantageous.

The setting of the shut-in gas-oil ratio (GOR) directly reflects the core trade-off between the objectives of oil displacement and storage in CO2 flooding projects. To maximize oil recovery, it is necessary to allow a certain degree of gas production to drive the remaining oil between wells. The optimal value of approximately 2000 m3/m3 identified in this study balances crude oil production with gas control. Conversely, to maximize storage efficiency, a lower shut-in GOR (e.g., 1500 m3/m3 or lower) should be adopted to retain the maximum amount of CO2 within the reservoir. This direct conflict highlights the importance of clarifying primary and secondary objectives in practical project decision-making [21,39]. Therefore, for Block Y, if the focus is primarily on oil displacement, it is recommended to set the shut-in GOR around 2000 m3/m3; if greater emphasis is placed on storage, a lower strategy could be considered. Ultimately, the optimal shut-in GOR should be determined based on the project’s main goal (whether it is primarily enhancing oil recovery or carbon storage) or the comprehensive economic benefits.

3.9. Influence of Bottom-Hole Flowing Pressure

The Bottom-Hole Flowing Pressure (BHP), by regulating the production pressure differential, profoundly affects the pressure distribution within the reservoir, the phase behavior of CO2, and its migration and displacement behavior. This study simulated five BHP scenarios ranging from 6 MPa to 10 MPa.

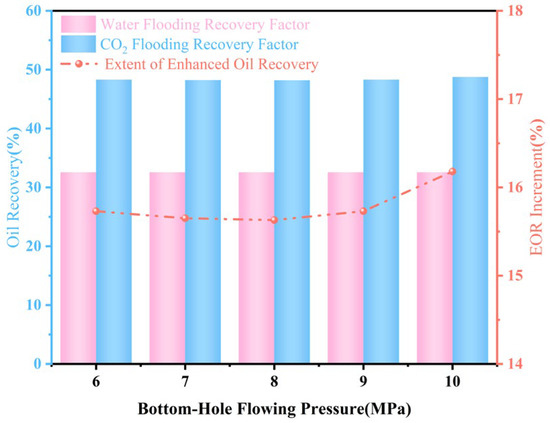

Simulation results (Figure 20) show that the influence of BHP on CO2 flooding recovery exhibits a complex, “high at both ends, lower in the middle” characteristic. When the BHP increases from 6 MPa to 8 MPa, the gas injection recovery factor slightly decreases from 48.30% to 48.20%. Subsequently, as the BHP further increases to 10 MPa, the gas injection recovery factor rebounds to 48.75%, achieving the highest EOR increment of 16.18%.

Figure 20.

Reservoir Recovery Factor.

This non-monotonic trend of “high at both ends, low in the middle” can be understood through the competitive relationship between “displacement drive” and “gas channeling risk”. At a lower BHFP (e.g., 6 MPa), the large production pressure differential, while accelerating fluid flow towards the wellbore, may also create a lower-pressure “sink” in the near-wellbore region. This pressure sink alters the direction of the pressure field to some extent, causing the injected CO2 to converge laterally towards the production well on a macroscopic scale rather than overriding vertically under gravity too early. This unintentionally partially suppresses the early formation of vertical gas channeling, thereby preserving a baseline displacement efficiency.

However, in the medium BHFP range (7–8 MPa), the production pressure differential is moderate. This pressure level is sufficient to maintain fluid flow but not enough to significantly alter the near-wellbore pressure field structure to suppress channeling. Conversely, it creates a “window” for a more unfavorable condition: the CO2 flow velocity is sufficient for mobility, yet gravity segregation makes it prone to upward migration. At this point, CO2 is more likely to break through and channel along existing or potential preferential pathways, leading to significant inefficient recycling of CO2 and a consequent decrease in displacement efficiency.

When the BHFP is increased to a high level (9–10 MPa), the production pressure differential becomes very small. This significantly reduces the flow velocity of all fluids, particularly greatly suppressing the channeling tendency of the low-viscosity CO2. The lower flow velocity allows more time for sufficient interaction between CO2 and crude oil (dissolution, swelling). Simultaneously, the higher average reservoir pressure helps maintain CO2 density and displacement capability. Therefore, the positive effect of suppressing channeling becomes completely dominant, resulting in the optimal oil displacement performance.

In summary, the optimal oil displacement effect occurs under flowing pressure conditions that maximally suppress gas channeling (whether by altering the flow field direction with a large pressure differential or directly reducing flow velocity with a small differential). The recovery “trough” in the medium flowing pressure interval precisely reflects the critical state where the risk of gas channeling is highest and the means to suppress it are insufficient.

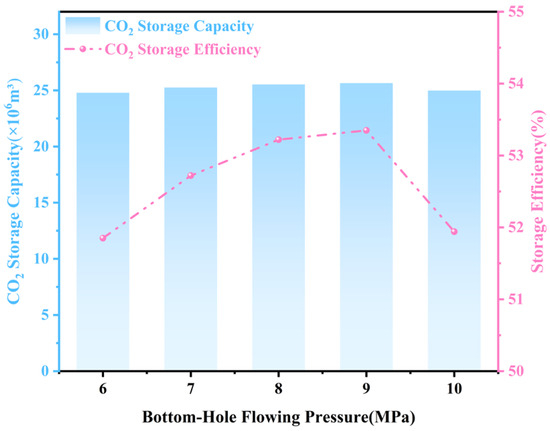

The influence of BHP on CO2 storage shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing (Figure 21). As the BHP increases from 6 MPa to 9 MPa, the CO2 storage capacity increases from 24.78 × 106 m3 to 25.64 × 106 m3, and the storage efficiency rises from 51.85% to 53.35%. However, at 10 MPa, both values decline.

Figure 21.

CO2 Storage Capacity and Storage Efficiency.

This trend is closely related to the overall reservoir pressure level:

- (1)

- Medium-High BHP (7–9 MPa) favors storage: Maintaining a relatively high BHP equates to maintaining a higher reservoir pressure system. This not only increases CO2 density (enhancing the spatial efficiency of free-phase storage) but also favors greater dissolution of CO2 into the crude oil and formation water (increasing dissolved storage) and enhances mechanical trapping mechanisms like capillary trapping. Therefore, the storage effect is optimal in this range.

- (2)

- Potential risks of excessively high BHP (10 MPa): When the BHP is too high, although beneficial for suppressing channeling, it may bring the reservoir pressure too close to or even exceed the pressure-bearing limit of the caprock or wellbore, posing safety risks. Simultaneously, the slight decrease observed in this model may indicate that injection efficiency begins to be affected, or that CO2 distribution in the reservoir is approaching saturation.

The bottom-hole flowing pressure (BHFP) is a key parameter that requires precise optimization. Research has found that maintaining a relatively high BHFP (9–10 MPa) is a crucial strategy that can synergistically enhance both oil displacement and storage effects. From the perspective of oil displacement, a higher BHFP (~10 MPa) effectively suppresses gas channeling by reducing the production pressure differential, thereby improving displacement efficiency. From a storage standpoint, a higher BHFP (~9 MPa) helps maintain a higher reservoir pressure system, which not only promotes the dissolution of CO2 into crude oil and formation water but also enhances mechanical trapping mechanisms such as capillary trapping, thereby maximizing both storage efficiency and capacity [23]. This indicates that a well-designed injection-production strategy can break the traditional trade-off between the two objectives and achieve a win-win outcome. In summary, for Block Y, a production strategy employing a relatively high BHFP (9–10 MPa) is recommended. However, during implementation, close attention must be paid to the integrity of the reservoir and wellbore to ensure the pressure remains within a safe operational window.

3.10. Summary of Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Guidance

Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5, Section 3.6, Section 3.7, Section 3.8 and Section 3.9 systematically investigated the effects of key parameters—including reservoir depth, vertical heterogeneity (KV/Kh), reservoir thickness, permeability, porosity, gas injection rate, cumulative gas injection volume, shut-in gas-oil ratio (GOR), and bottom-hole flowing pressure (BHFP)—on the performance of CO2 flooding and storage. To present the influencing patterns and optimization directions of these parameters clearly and comprehensively, the findings from the above analyses are summarized in Table 4. This table not only outlines the simulated test range and the impact trends on enhanced oil recovery (EOR) and CO2 storage for each parameter but also specifies their recommended optimal values or ranges. It is intended to provide direct parameter optimization guidance for implementing synergistic CO2 flooding and storage projects in Block Y and similar reservoirs.

Table 4.

Summary of Sensitivity Analysis Parameters.

4. Conclusions

Through systematic numerical simulation, this study reveals the synergistic influencing mechanisms and optimization pathways for implementing CO2 flooding and geological storage in the low-permeability, high-water-cut reservoir of Block Y in the Daqing Oilfield. The research confirms that the low-permeability characteristic (approximately 5.45 mD) of this reservoir effectively suppresses CO2 channeling, serving as a natural advantage for efficient displacement, and under these conditions, CO2 flooding can enhance oil recovery by more than 15.65%. Among the geological factors, reservoir depth is identified as a decisive parameter; its increase synergistically improves both oil recovery and storage efficiency by elevating formation pressure and temperature. Furthermore, an optimal range exists for vertical heterogeneity (KV/Kh ≈ 0.3), while thinner reservoirs are more favorable for achieving a higher EOR increment. In terms of engineering strategy, parameter optimization is key to achieving synergistic benefits: the optimal gas injection rate should be controlled within 700–900 m3/d, the economically reasonable cumulative gas injection volume is 0.4–0.5 PV, and a relatively high bottom-hole flowing pressure (9–10 MPa) is recommended for production to synchronously optimize oil displacement and storage effects. This study provides a technical pathway for Block Y and similar reservoirs, demonstrating that through the synergistic optimization of geological and engineering parameters, it is entirely feasible to simultaneously achieve significant crude oil production enhancement (EOR > 15%) and efficient CO2 geological storage.

It should be noted that the homogeneous conceptual model adopted in this study, while effective for focusing on mechanistic insights, does not fully capture the complex effects of actual reservoir heterogeneities such as fractures and interlayers on gas migration and sweep efficiency. Future research could incorporate more refined geological models and consider long-term storage mechanisms like mineral reactions to more comprehensively evaluate the long-term stability of storage. Simultaneously, conducting a full lifecycle economic evaluation of the optimization parameters obtained in this study will be a critical step in advancing this technology from theory to large-scale field application.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Writing—original draft, Q.W.; Writing—review and editing, J.Z.; Software, G.H.; Validation, P.W.; Investigation, F.L.; Data curation, X.T.; Writing—original draft, Q.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qi Wang, Guantong Huo, Peng Wang and Qiang Xie were employed by the company Daging Oilfeld Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cao, X.; Lyu, Q.; Lyu, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, W. CO2 high-pressure miscible flooding and storage technology and its application in Shengli Oilfield, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Augusto Sampaio, M.; Ojha, K.; Hoteit, H.; Mandal, A. Fundamental aspects, mechanisms and emerging possibilities of CO2 miscible flooding in enhanced oil recovery: A review. Fuel 2022, 330, 125633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Rui, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Du, K. An improved prediction model for miscibility characterization and optimization of CO2 and associated gas co-injection. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 242, 213284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Qiao, L.; Li, Z.; Luo, R.; Han, G.; Tan, J.; Liu, X. Experimental study on oil recovery characteristics of different CO2 flooding methods in sandstone reservoirs with NMR. Fuel 2025, 385, 134124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-R.; Zhang, D.-F.; Liu, S.-Y.; Gong, R.-D.; Wang, L. Multiscale investigation into EOR mechanisms and influencing factors for CO2-WAG injection in heterogeneous sandy conglomerate reservoirs using NMR technology. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 2977–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Xiao, W.; Pu, W.; Tang, Y.; Bernabé, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zheng, L. Characterization of CO2 miscible/immiscible flooding in low-permeability sandstones using NMR and the VOF simulation method. Energy 2024, 297, 131211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.-J.; Gao, M.; Wang, Z.-B.; Liu, W.-L. Status and progress of worldwide EOR field applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 193, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, L.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, X. Investigation of CO2-EOR and storage mechanism in Injection-Production coupling technology considering reservoir heterogeneity. Fuel 2024, 368, 131595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wu, Z.; Lian, L. Microscopic Experiments to Assess the Macroscopic Sweep Characteristics of Carbon Dioxide Flooding. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.Y.; Wang, R.; Cui, M.L.; Tang, Y.Q.; Zhou, X. Experiment on CO2 Miscible Displacement Under High Water Cut Conditions. Acta Pet. Sin. 2017, 38, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, C.; Lun, Z.; Cui, M.; Lang, D. Displacement characteristics of CO2 flooding in extra-high water-cut reservoirs. Energy Geosci. 2024, 5, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Yan, Z.; Lai, J.; Wang, K. Molecular insight into oil displacement by CO2 flooding in water-cut dead-end nanopores. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25385–25392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H. Study on the microscopic mechanism of CO2 flooding in deep high-temperature, high pressure, ultra-high water-cut reservoirs: A case study of the X-1 reservoir. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15337–15346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Gou, F.F.; Lang, D.J. Oil Displacement Mechanism of CO2 in High Water Cut Reservoirs. Acta Petrolei Sinica 2016, 37, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wan, W.S.; Li, C.; Luo, H.C.; Liu, Y.T.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhang, R.X. Pilot Test of CO2 Miscible Flooding in Extra-High Water Cut Reservoir of Xishanyao Formation in Cai 9 Well Block. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2021, 28, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Wu, H.; Wang, J. Potential of carbon dioxide miscible injections into the H-26 reservoir. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, F.K.; Xu, Y.F.; Wen, C.Y.; Li, Y.J. Joint Optimization of CO2 Oil Displacement and Storage in High Water Cut Reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2024, 31, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.; Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Fu, H.; Bai, M.; Emami-Meybodi, H. A Novel Method for Enhancing Oil Recovery by Thickened Supercritical CO2 Flooding in High-Water-Cut Mature Reservoirs. Engineering 2025, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, W.; Li, S.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Xue, X.; Tu, N.; He, S. Research and Application of Non-Steady-State CO2 Huff-n-Puff Oil Recovery Technology in High-Water-Cut and Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, B.S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lü, G.Z.; Zhang, C.B.; Cao, W.D. Research Status and Key Unsolved Problems of CO2 Oil Displacement and Geological Storage Mechanisms in High Water Cut Reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2023, 30, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Rui, Z. A Storage-Driven CO2 EOR for a Net-Zero Emission Target. Engineering 2022, 18, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Huang, S.; Hao, H.; Zhang, M.; Lu, G. Performance and applicable limits of multi-stage gas channeling control system for CO2 flooding in ultra-low permeability reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 192, 107336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Su, Y.-L.; Li, L.; Meng, F.-K.; Zhou, X.-M. Characteristics and mechanisms of supercritical CO2 flooding under different factors in low-permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, J.; Lorinczi, P.; Glover, P.; Yang, S.; Chen, H. Oil production performance and reservoir damage distribution of miscible CO2 soaking-alternating-gas (CO2-SAG) flooding in low permeability heterogeneous sandstone reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Cao, B.; Liu, F.; Jiang, L.; Luo, Z.; Liu, P.; Chen, Y. CO2 flooding effects and breakthrough times in low-permeability reservoirs with injection–production well patterns containing hydraulic fractures. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Xin, Y.; Han, X.; Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, B. Experimental study on CO2 flooding in tight sandy conglomerate cores: Oil displacement and CO2 storage. Energy 2025, 333, 137336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, B.; Hao, H.; Deng, S.; Wu, H.; Sun, T.; Cheng, L.; Jin, Z. Laboratory experiments of CO2 flooding and its influencing factors on oil recovery in a low permeability reservoir with medium viscous oil. Fuel 2024, 371, 131871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Yao, J.; Li, A.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L. Pore-Scale Investigation of Carbon Dioxide-Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 5324–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Riyami, H.F.; Kamali, F.; Hussain, F. Effect of Gravity on Near-Miscible CO2 Flooding. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 24–27 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Qi, H.; Sun, X.; Luo, J. Effect of gravity segregation on CO2 flooding under various pressure conditions: Application to CO2 sequestration and oil production. Energy 2021, 226, 120294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.G.; Zhao, F.L.; Feng, H.R.; Wang, Q.; Lou, X.K. Influence Law of Permeability on CO2 Flooding Gravity Override in Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2020, 27, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Su, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, W. Experimental exploration of CO2 dissolution, diffusion, and flow characteristics in bound water conditions during oil displacement and sequestration. Fuel 2025, 386, 134249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.L.; Song, L.G.; Feng, H.R.; Cheng, J. Experimental Study on CO2 Flooding Gravity Override Affected by Crude Oil Density in Thick Sandstone Reservoirs. Fault-Block Oil Gas Fields 2021, 28, 842–847. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, X.G.; Dong, R.C.; Teng, W.C.; Zhan, S.Y.; Zeng, G.Y.; Jia, C.Q. Reservoir heterogeneity controls of CO2-EOR and storage potentials in residual oil zones: Insights from numerical simulations. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.-X.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Yang, E.-L.; Du, S.-Y. Experimental study of microscopic oil production and CO2 storage in low-permeable reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cheng, L.; Cao, R.; Lyu, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Rao, X. Carbon dioxide transport in radial miscible flooding in consideration of rate-controlled adsorption. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, L.; Chai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K. Effect of pore structure on recovery of CO2 miscible flooding efficiency in low permeability reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.; Xu, C.; Zuo, M.; Gao, S.; Yi, W.; Liu, H.; Qi, X.; Brahim, M.S. Characteristics of the CO2 Flooding Front for CO2-EOR in Unconventional Reservoirs: Considering the Different Miscibilities of CO2-Crude Oil. In Proceedings of the Mediterranean Offshore Conference, Alexandria, Egypt, 20–22 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, P.; Cui, C.; Wu, Z.; Yan, D. Influence of reservoir heterogeneity on immiscible water-alternating-CO2 flooding: A case study. Energy Geosci. 2024, 5, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).