Assessment of Potential for Green Hydrogen Production in a Power-to-Gas Pilot Plant Under Real Conditions in La Guajira, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This study provides a comprehensive performance assessment of a power-to-gas (PtG) pilot plant powered by a hybrid wind-solar system under real operating conditions over a continuous 9-month period, going beyond short-term or purely theoretical analyses.

- This study delivers a detailed quantification of the actual energy yield from each renewable source (wind and solar PV) and the corresponding capacity factors under site-specific resource conditions, which can be comparable with regions with tropical conditions.

- This study integrates a temporal analysis of hydrogen production that is explicitly aligned with the dynamic operation of the electrolysis system, enabling the estimation of the real system operation state depending on the availability of renewable sources.

- This study bridges the gap between simulation-based projections and real-world performance, providing new insights into small-scale PtG systems’ operational behavior and constraints.

- This study establishes a realistic operational scenario for power-to-gas systems in regions with similar irradiation and wind regimes and could serve as a decision-support tool for system planning, optimization, and future upscaling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pilot Plant Scheme

2.2. Calculation of the Theoretical Power of Wind and Photovoltaic Systems

2.3. Data Collection for Energy Production from the Hybrid System

2.4. Calculation of the Capacity Factor

3. Results and Discussions

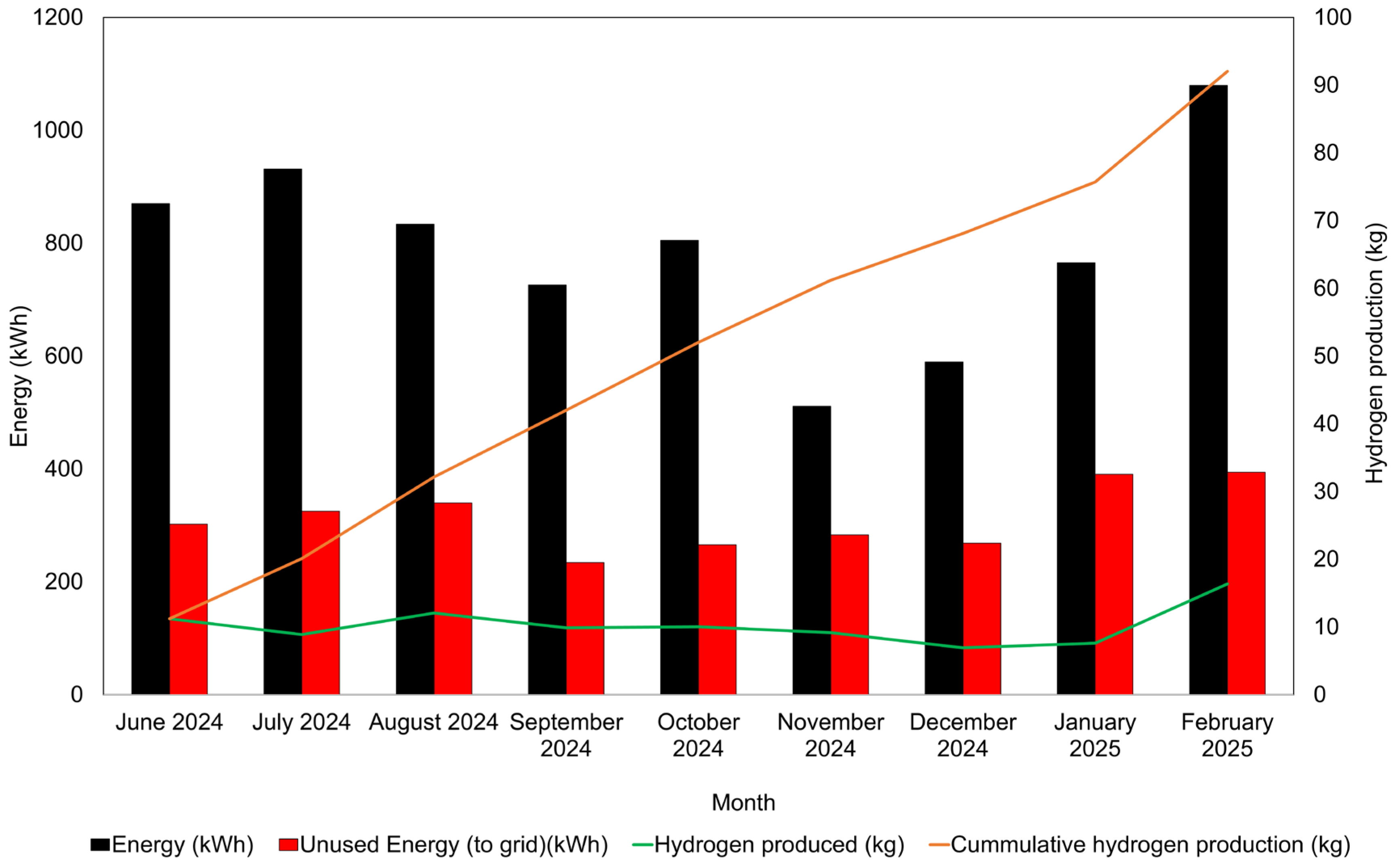

3.1. Pilot Plant Renewable Energy Production

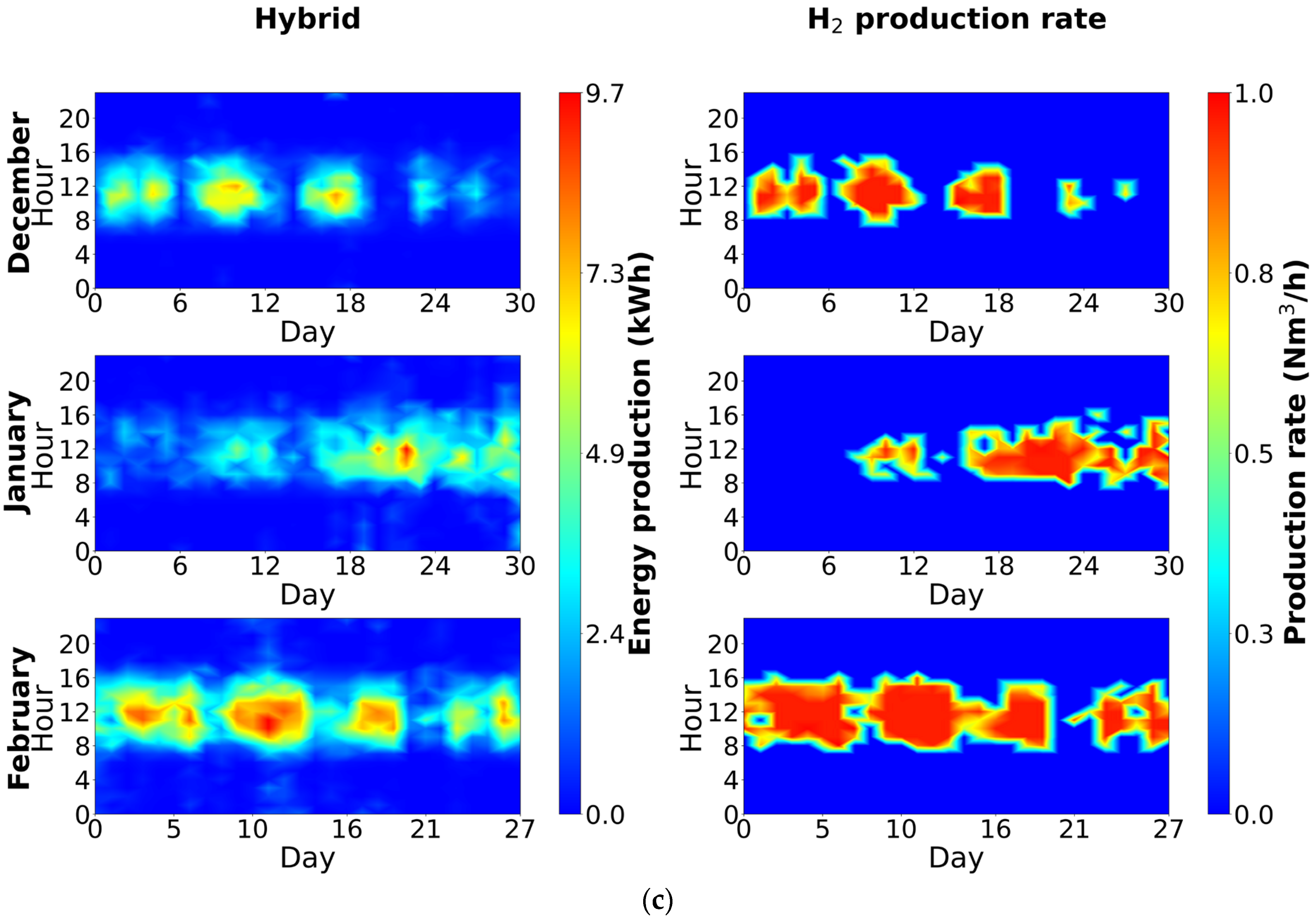

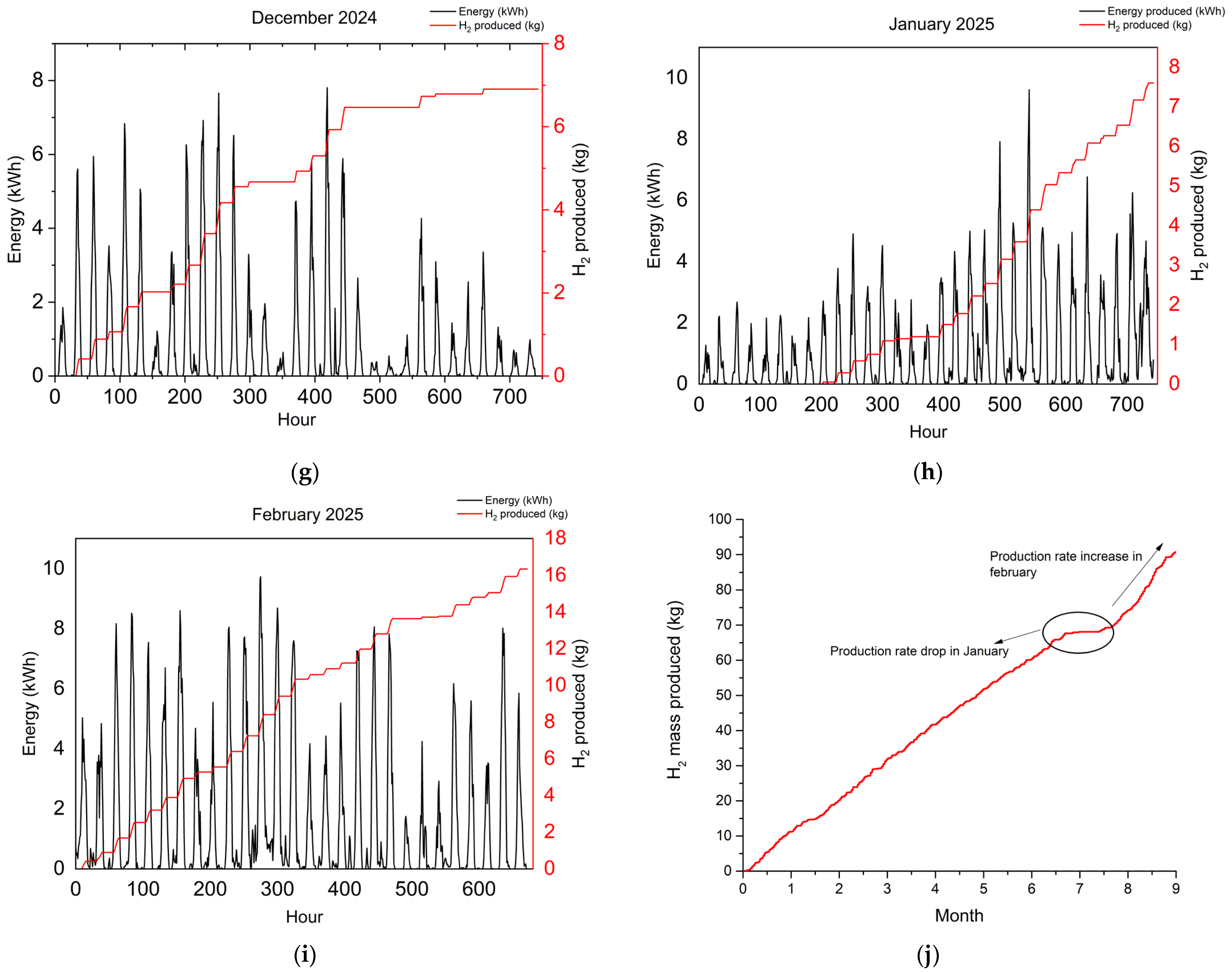

3.2. Green Hydrogen Production Potential Based on the Availability of Renewable Sources

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gahleitner, G. Hydrogen from Renewable Electricity: An International Review of Power-to-Gas Pilot Plants for Stationary Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 2039–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias, P.; Antón-Sancho, Á.; Lampropoulos, G.; Vergara, D. On Green Hydrogen Generation Technologies: A Bibliometric Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas Barranco, M.; Serrano Flórez, D.; Amell Arrieta, A.; Echeverri Uribe, C.; Colorado Granda, A.; Córdoba Ramírez, M. Desarrollo de Sistemas Power to Gas Basados En Fuentes de Energía Renovables No Convencionales Del Departamento de La Guajira. In Alianza SENECA: Impulsando la Transformación y la Sostenibilidad Energética de Colombia; Universidad de la Guajira: Riohacha, Colombia, 2023; Volume 1, ISBN 978-628-7619-95-1. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C.; Selosse, S.; Maïzi, N. The Role of Power-to-Gas in the Integration of Variable Renewables. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Botero, C.; Echeverri-Uribe, C.; Ferrer-Ruiz, J.E.; Amell, A.A. Effect of Preheat Temperature, Pressure, and Residence Time on Methanation Performance. Energy 2023, 269, 126693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Zheng, W.; Bai, Z.; Han, Y.; Yu, Z. Operating Characteristics Analysis and Capacity Configuration Optimization of Wind-Solar-Hydrogen Hybrid Multi-Energy Complementary System. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1305492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Azam, A.M.I.; Ragunathan, T.; Zulkefli, N.N.; Masdar, M.S.; Majlan, E.H.; Mohamad Yunus, R.; Shamsul, N.S.; Husaini, T.; Shaffee, S.N.A. Investigation of Performance of Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) Electrolysis with Different Operating Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Nagasawa, K.; Todoroki, N.; Ito, Y.; Matsui, T.; Nakajima, R. Influence of Renewable Energy Power Fluctuations on Water Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 4572–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobó, Z.; Palotás, Á.B. Impact of the Current Fluctuation on the Efficiency of Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 5649–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, E.; Olivier, P.; Pera, M.C.; Pahon, E.; Roche, R. Impacts of Intermittency on Low-Temperature Electrolysis Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 474–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Qin, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Liu, D.; et al. Highly Efficient Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers via Chromium-Doped Amorphous Electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.; Li, X.; Sluijter, S.; Shirvanian, P.; Lai, Q.; Liang, Y. Design and Scale-Up of Zero-Gap AEM Water Electrolysers for Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Pereira, R.M.M.; Pereira, A.J.C. Techno-Economic Assessment of Hydrogen Production Using Solar Energy. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 2022, 20, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Alawi, A.H.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Aamer, H.; Yoo, C. Techno-Economic Risk-Constrained Optimization for Sustainable Green Hydrogen Energy Storage in Solar/Wind-Powered Reverse Osmosis Systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, F.I.; Monforti Ferrario, A.; Lamagna, M.; Bocci, E.; Astiaso Garcia, D.; Baeza-Jeria, T.E. A Techno-Economic Analysis of Solar Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis in the North of Chile and the Case of Exportation from Atacama Desert to Japan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 13709–13728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaresi, A.; Morini, M.; Gambarotta, A. Review on the Status of the Research on Power-to-Gas Experimental Activities. Energies 2022, 15, 5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yang, H.; Lu, L. A Feasibility Study of a Stand-Alone Hybrid Solar-Wind-Battery System for a Remote Island. Appl. Energy 2014, 121, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buraiki, A.S.; Al-Sharafi, A. Hydrogen Production via Using Excess Electric Energy of an Off-Grid Hybrid Solar/Wind System Based on a Novel Performance Indicator. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, R.; Hamdi, M.; El Salmawy, H.A.; Ismail, M.A. Optimized System for Combined Production of Electricity/Green Hydrogen for Multiple Energy Pathways: A Case Study of Egypt. Clean. Energy 2024, 8, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Kaufmann, F.; Hollinger, R.; Voglstätter, C. Real Live Demonstration of MPC for a Power-to-Gas Plant. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega de la Cruz, L.A.; Serrano-Florez, D.; Bastidas-Barranco, M. Analysis of the Availability Curve of the 15 KW Wind–Solar Hybrid Microplant Associated with the Demand of the Power-to-Gas (PtG) Pilot Plant Located at University of La Guajira. Processes 2024, 12, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H2lac.org La Guajira: Un Polo En El Desarrollo Del Power-to-Gas En Colombia. Available online: https://h2lac.org/noticias/la-guajira-un-polo-en-el-desarrollo-del-power-to-gas-en-colombia/#:~:text=El%20piloto%20corresponde%20a%20un%20sistema%20tecnológico,con%20dióxido%20de%20carbono%20para%20formar%20metano.&text=Así%2C%20constituye%20una%20estrategia%20destacada%20en%20la%20transición%20energética (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Enapter Aem Technology—Knowledge Base. Available online: https://handbook.enapter.com/knowledge_base/aem_technology.html (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Enapter Enapter EL 2.1 Handbook. Available online: https://handbook.enapter.com/electrolyser/el21/el21.html?_x_tr_hist=true (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Mejía Botero, C.; Echeverri Uribe, C.; Amell Arrieta, A.A.; Bastidas Barranco, M. Análisis del efecto de operar un reactor de metanación en cargas diferentes de las de diseño en un proceso P2G. Ing. Cienc. Tecnol. E Innovación 2022, 9, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hu, W.; Cao, D.; Liu, W.; Huang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Z. Enhanced Design of an Offgrid PV-Battery-Methanation Hybrid Energy System for Power/Gas Supply. Renew. Energy 2021, 167, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Power Data Acces Viewer. Available online: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Chioncel, C.P.; Spunei, E.; Tirian, G.O. The Problem of Power Variations in Wind Turbines Operating under Variable Wind Speeds over Time and the Need for Wind Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Son, S.Y. Theoretical Energy Storage System Sizing Method and Performance Analysis for Wind Power Forecast Uncertainty Management. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, M.Z.; Nazari, M.E.; Shamlou, S.; Shafie-Khah, M. The Simultaneous Impacts of Seasonal Weather and Solar Conditions on Pv Panels Electrical Characteristics. Energies 2021, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo, F.M.; Santos, P.J.; Pires, A.J. A Comparative Analysis of Real and Theoretical Data in Offshore Wind Energy Generation. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 11, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Stackhouse, P.; Kim, J.H.; Muehleisen, R.T. Development of Typical Solar Years and Typical Wind Years for Efficient Assessment of Renewable Energy Systems across the U.S. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffell, I.; Pfenninger, S. Using Bias-Corrected Reanalysis to Simulate Current and Future Wind Power Output. Energy 2016, 114, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.; Nazih, N.; Makeen, P. Wind Speed Prediction Based on Variational Mode Decomposition and Advanced Machine Learning Models in Zaafarana, Egypt. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra Gasca, L.M.; Gomez Pimentel, S.; Montoya Castillo, C. Complementariedad Energética Entre las Centrales Eléctricas Renovables de Colombia; Universidad ICESI: Cali, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, G.; Prado, B. Complementariedad Energética entre los Recursos Eólico y Solar para la Región Caribe Colombiana; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, H.K.; Yadav, S.; Narayan Gupta, M.; Sarkar, A.; Sarkar, J. Diurnal Variations in Wind Power Density Analysis for Optimal Wind Energy Integration in Different Indian Sites. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüdisüli, M.; Mutschler, R.; Teske, S.L.; Sidler, D.; van den Heuvel, D.B.; Diamond, L.W.; Orehounig, K.; Eggimann, S. Potential of Renewable Surplus Electricity for Power-to-Gas and Geo-Methanation in Switzerland. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 14527–14542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Harrison, G.P.; Dodds, P.E. A Multi-Model Method to Assess the Value of Power-to-Gas Using Excess Renewable. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9103–9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, S. Power to Gas: An Option for 2060 High Penetration Rate of Renewable Energy Scenario of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 6857–6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Nwobu, J.; Campos-Gaona, D. The Co-Development of Offshore Wind and Hydrogen in the UK—A Case Study of Milford Haven South Wales. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; Institute of Physics: Singapore, 2023; Volume 2507. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; West, S.R. Co-Optimisation of Wind and Solar Energy and Intermittency for Renewable Generator Site Selection. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayedin, F.; Maroufmashat, A.; Sattari, S.; Elkamel, A.; Fowler, M. Optimization of Photovoltaic Electrolyzer Hybrid Systems; Taking into Account the Effect of Climate Conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 118, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, S.; Cordero, R.R.; Damiani, A.; Jackson, R.B. Climate Change Extremes and Photovoltaic Power Output. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of performance ( | 0.59 | [21] |

| Swept area (A) | 24.6 m2 | Wind turbine datasheet |

| Mechanical drive, electrical generator, and auxiliary system efficiency ( | 0.95 | Wind turbine datasheet |

| Number of panels ( | 28 | - |

| Inverter efficiency ( | 0.99 | Inverter datasheet |

| Rated power of the solar panels ( | 330 W | Solar panel datasheet. |

| Reference radiation ( | 1000 W/m2 | [26] |

| The temperature coefficient ( | [26] | |

| Reference cell temperature ( | 25 °C | [26] |

| Period | Mean Bias Error (MBE) | Mean Squared Error (RSME) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | Wind | Hybrid System | PV | Wind | Hybrid System | PV | Wind | Hybrid System | |

| June 2024 | 2755.1 | 125.2 | 2151.8 | 3775.2 | 1009.4 | 2909.0 | 0.1352 | 0.0014 | 0.6712 |

| July 2024 | 2782.8 | 273.7 | 2259.8 | 3811.5 | 1111.3 | 3537.3 | 0.0005 | 0.0116 | 0.0512 |

| August 2024 | 2423.6 | −3.6 | 2016.1 | 3646.0 | 1116.2 | 3830.8 | 0.1335 | 0.0094 | 0.1950 |

| September 2024 | 2438.2 | −179.3 | 1788.2 | 3593.8 | 928.4 | 3516.2 | 0.1214 | 0.0013 | 0.1854 |

| October 2024 | 2738.2 | −133.2 | 1611.3 | 3667.0 | 1281.2 | 2969.9 | 0.0052 | 0.0111 | 0.0215 |

| November 2024 | 2988.5 | −319.0 | 1416.0 | 3784.3 | 1278.5 | 2310.5 | 0.0230 | 0.0161 | 0.3990 |

| December 2024 | 2268.0 | 509.8 | 1918.1 | 3179.5 | 1206.6 | 2974.9 | 0.0422 | 0.0898 | 0.1505 |

| January 2025 | 2057.2 | 1013.7 | 2714.3 | 3365.4 | 1440.9 | 3935.3 | 0.0540 | 0.0116 | 0.0147 |

| February 2025 | 1253.2 | −814.9 | 338.3 | 3387.6 | 1910.6 | 4327.9 | 0.2396 | 0.0442 | 0.2341 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cordoba-Ramirez, M.; Bastidas-Barranco, M.; Serrano-Florez, D.; Noriega De la Cruz, L.A.; Amell Arrieta, A.A. Assessment of Potential for Green Hydrogen Production in a Power-to-Gas Pilot Plant Under Real Conditions in La Guajira, Colombia. Energies 2025, 18, 6631. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246631

Cordoba-Ramirez M, Bastidas-Barranco M, Serrano-Florez D, Noriega De la Cruz LA, Amell Arrieta AA. Assessment of Potential for Green Hydrogen Production in a Power-to-Gas Pilot Plant Under Real Conditions in La Guajira, Colombia. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6631. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246631

Chicago/Turabian StyleCordoba-Ramirez, Marlon, Marlon Bastidas-Barranco, Dario Serrano-Florez, Leonel Alfredo Noriega De la Cruz, and Andres Adolfo Amell Arrieta. 2025. "Assessment of Potential for Green Hydrogen Production in a Power-to-Gas Pilot Plant Under Real Conditions in La Guajira, Colombia" Energies 18, no. 24: 6631. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246631

APA StyleCordoba-Ramirez, M., Bastidas-Barranco, M., Serrano-Florez, D., Noriega De la Cruz, L. A., & Amell Arrieta, A. A. (2025). Assessment of Potential for Green Hydrogen Production in a Power-to-Gas Pilot Plant Under Real Conditions in La Guajira, Colombia. Energies, 18(24), 6631. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246631