Identification of Important Lines in Power Grids Based on Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Original ProfitLeader Algorithm

- The ProfitLeader algorithm was originally designed for identifying key nodes in social networks. As this study focuses on identifying critical lines in power systems, it is necessary to transform the power network into a line correlation network before applying the algorithm, thereby adapting it to the specific requirements of line analysis.

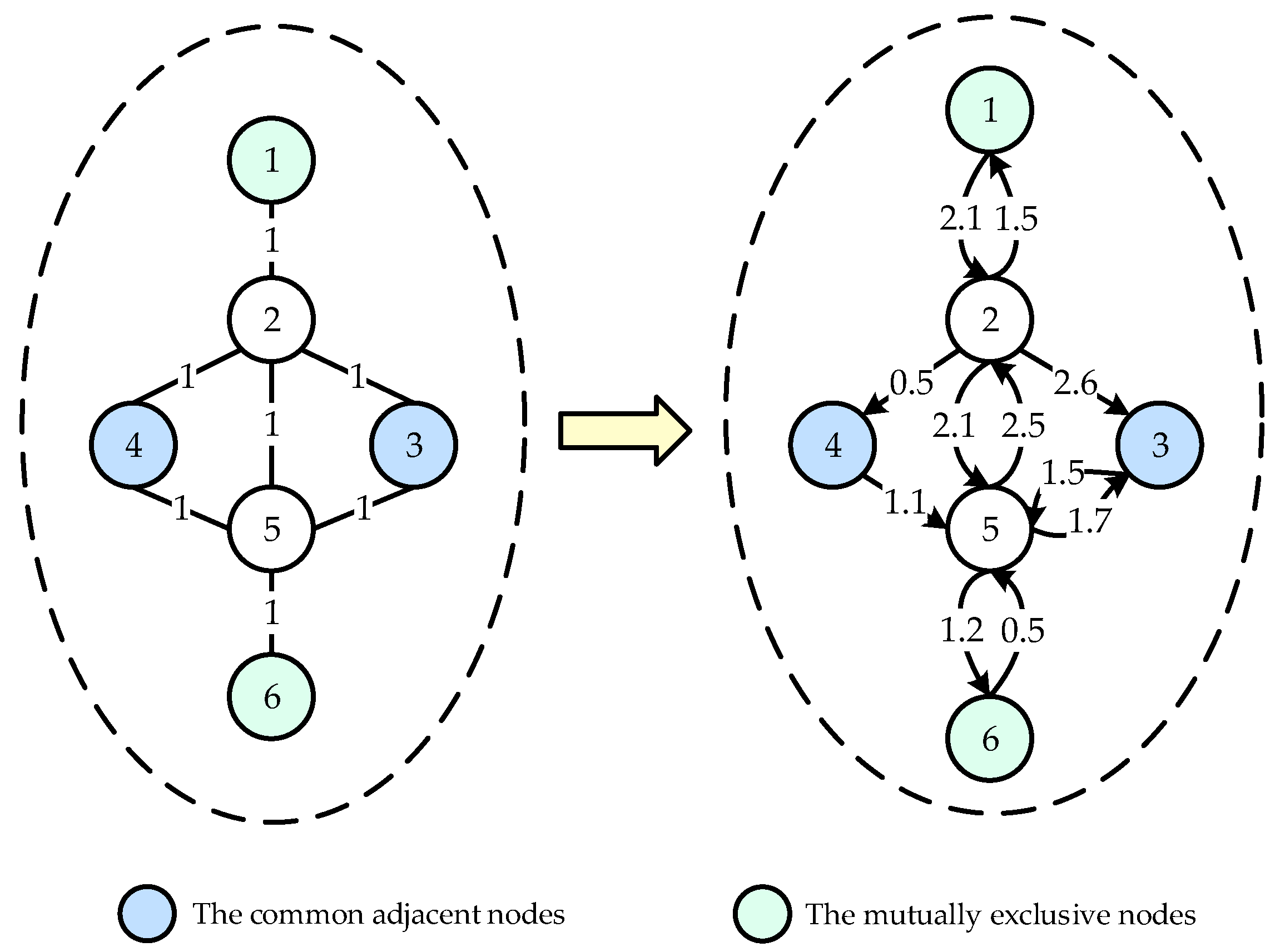

- The ProfitLeader algorithm primarily analyzes direct connections between nodes but does not adequately account for variations in connection strength. Given the significant differences in connection strength between nodes, the weights of connections should be emphasized when screening for critical lines.

- In the network model constructed by the traditional ProfitLeader algorithm, the relationships between nodes are typically assumed to be symmetric and undirected. However, in the actual fault propagation process of power systems, the electrical coupling and power flow transfer between lines exhibit significant asymmetry and directionality. Consequently, to more accurately assess the importance of nodes in fault propagation, it is necessary to distinguish between the out-degree and in-degree of nodes in the model to reflect their differential influences in different propagation directions.

3. Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm

3.1. Comparison Between Social Network Evaluation and Power Grid Transmission Line Assessment

- Calculate and record the power flow magnitude through each transmission line under normal operating conditions.

- Perform sequential branch outages by disconnecting each line individually, then compute and document the resulting power flow variations in all other lines.

- If no line exceeds its thermal stability limit, proceed to Step 4. Otherwise, disconnect the overloaded line, recalculate the power flow, and record the new system state.

- Normalize the power flow variation in each line by dividing it by the corresponding thermal stability limit, thereby obtaining the correlation matrix of the power system.

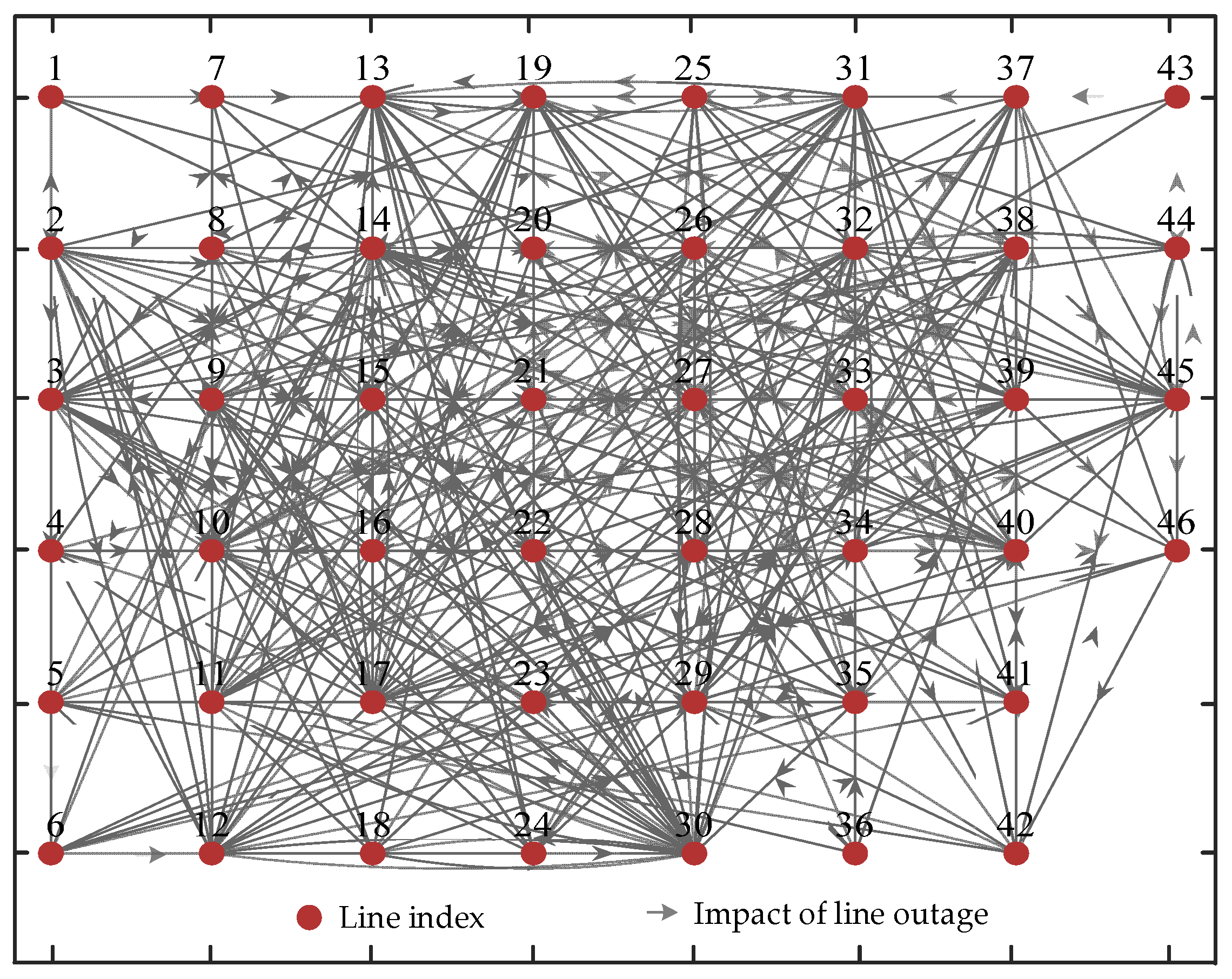

3.2. Construction of the Line Correlation Matrix

- If the power flow direction on the line remains unchanged before and after the fault, and the absolute value of the post-fault power flow is less than its initial absolute value, then ΔPi,j is set to 0.

- If the power flow direction remains unchanged before and after the fault and the absolute value of the post-fault power flow is not less than the initial value, or if the power flow direction reverses after the fault, then ΔPi,j is assigned the absolute value of the difference between the pre-fault and post-fault power flows on the line.

3.3. Important Transmission Lines

3.4. ProfitLeader Algorithm Calculation Process

- Load the power grid data, calculate the power flow distribution of each transmission line under the initial operating state, and record the thermal stability margin of each line.

- Considering the subsequent overload failures under the N−1 security criterion, compute the correlation matrix according to Equations (4) and (5), and construct a correlation network that reflects the interdependencies among transmission lines. This transforms the line identification problem into a node evaluation problem.

- Based on Equations (7) and (8), calculate, respectively, the available resources each line can provide to neighboring lines and the probability of resource sharing.

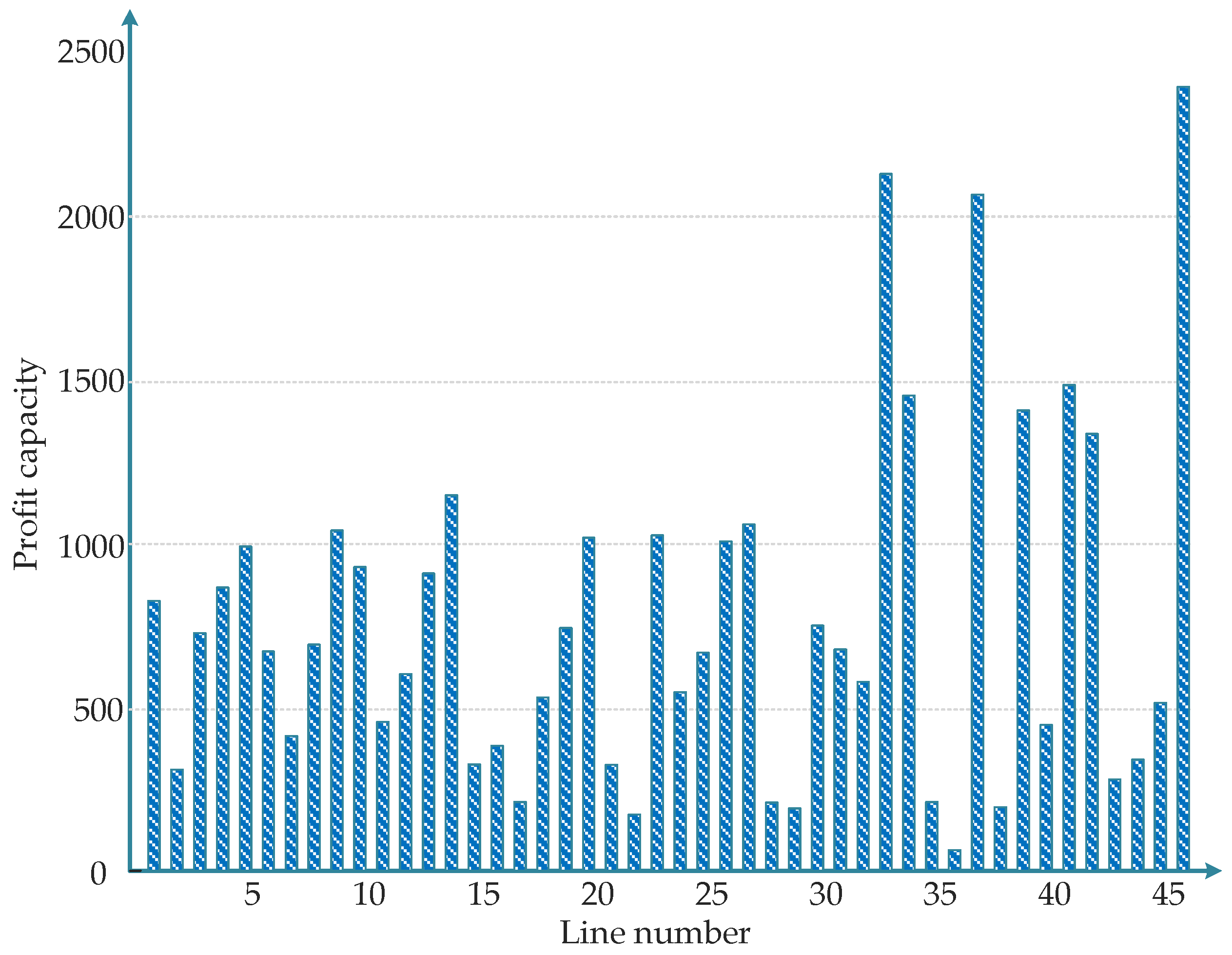

- Determine the profit capacity value of each transmission line using Equation (9).

- Rank the transmission lines in descending order of their profit capacity. Lines with higher profit capacity exert greater influence on surrounding lines when they fail, and thus possess higher importance.

4. Case Study

4.1. Indicator Verification

4.1.1. System Connectivity Metric

4.1.2. System Load Loss Metric

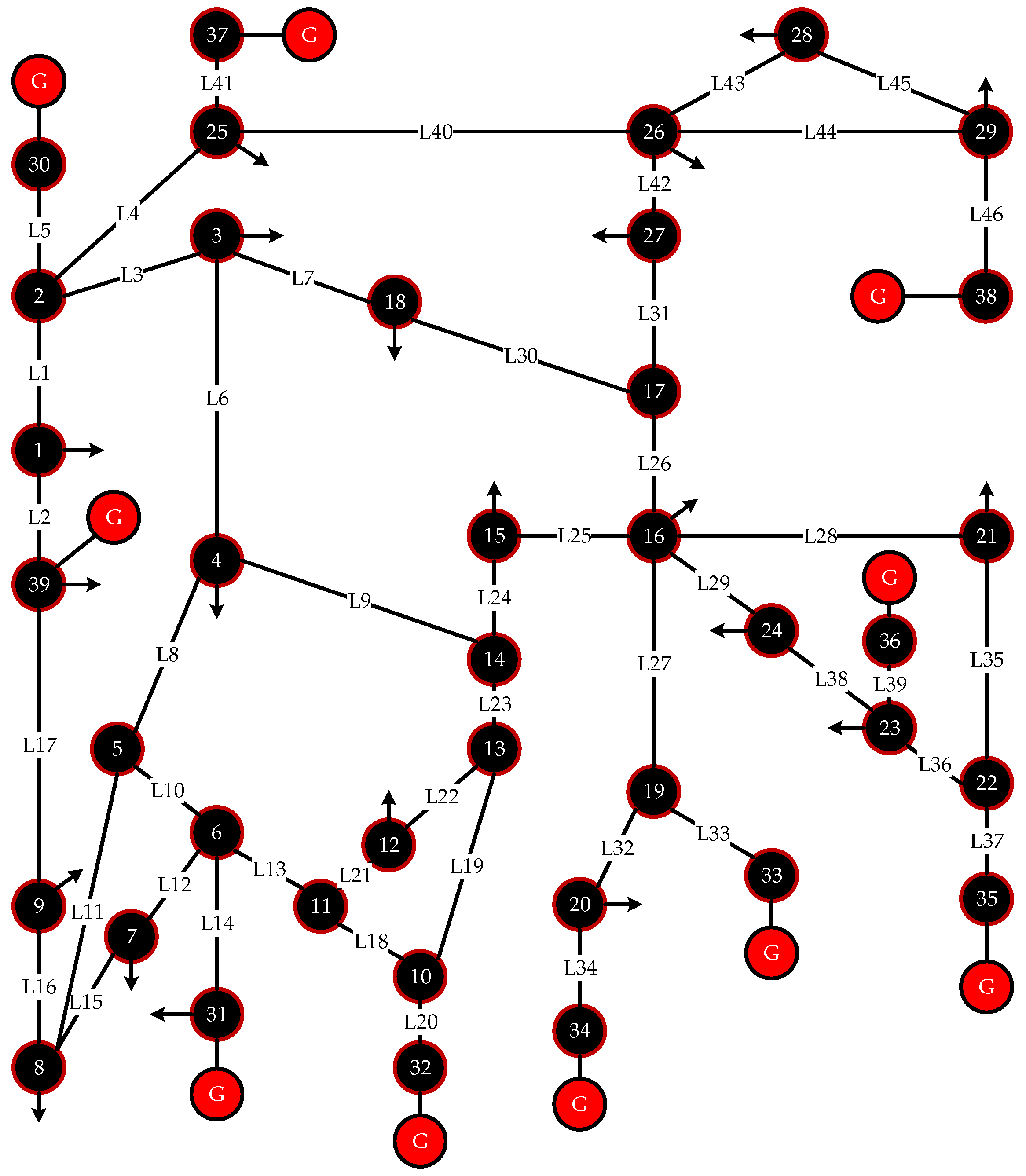

4.2. IEEE 39-Bus Electrical Power System

5. Conclusions

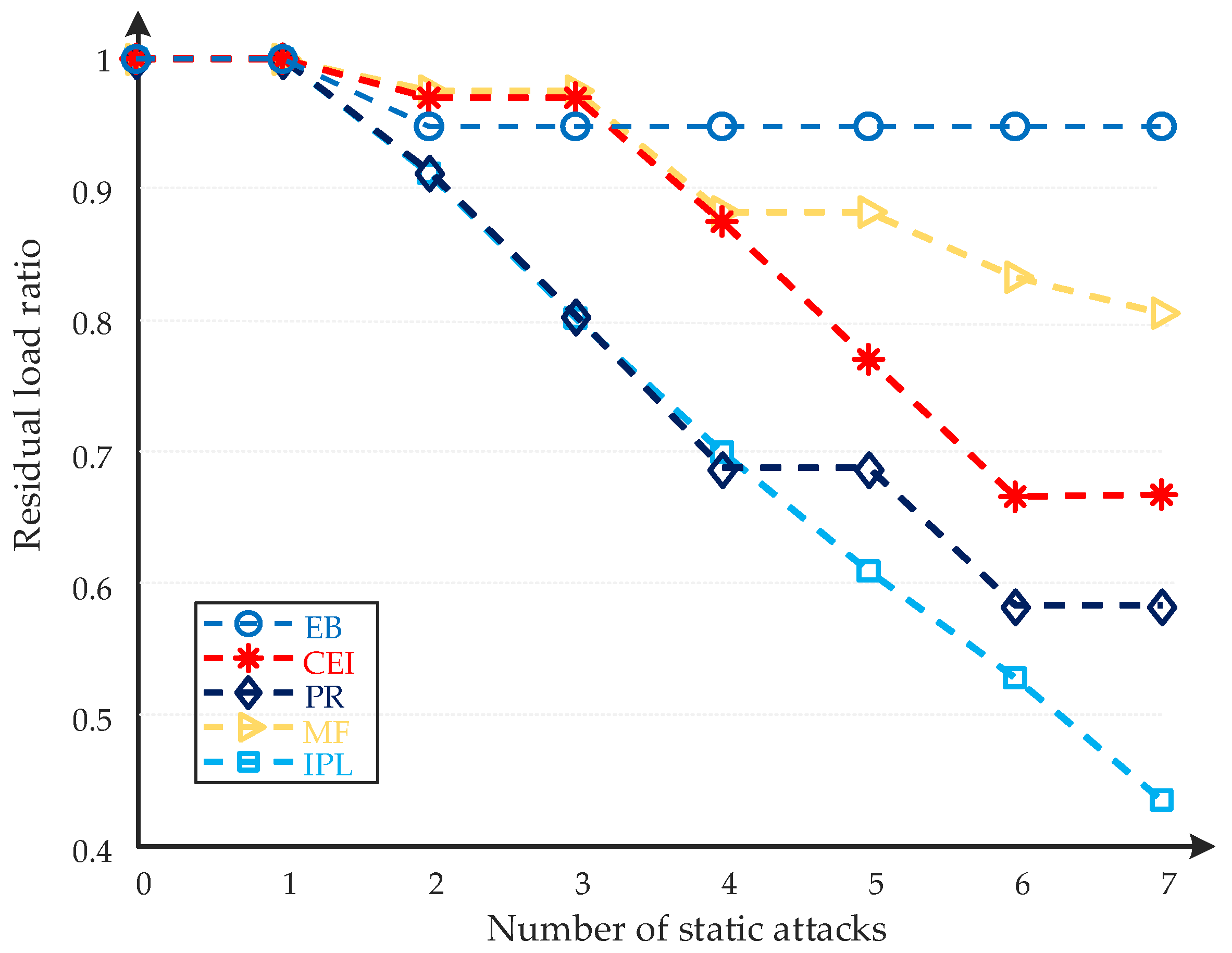

- The study constructs a directed weighted correlation network for power system lines, transforming the problem of line criticality identification into one of node importance evaluation in networks. This approach quantifies mutual influences between lines and, unlike MF and EB methods that primarily focus on topological impacts, comprehensively considers both power flow dynamics and topological structural effects on line identification.

- The IPL algorithm demonstrates superior performance over PR, CEI, MF, and EB methods in terms of both system remaining load ratio and number of electrical islands. When the top seven critical lines identified by the improved algorithm were subjected to static attacks, the system’s remaining load ratio decreased to 43.7% while the number of electrical islands increased to eight. These results confirm that the proposed method can more accurately identify critical lines in power systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OPA | ORNL-PSERC-Alaska |

| IPL | Improved ProfitLeader |

| PR | PageRank |

| EB | Electric Betweenness |

| MF | Maximum Flow |

| CEI | Catastrophic Expectation Index |

| DC-OPA | Direct ORNL-PSERC-Alaska |

References

- Wang, W.; Lin, W.; He, G.; Shi, W.; Feng, S. Enlightenment of 2021 Texas blackout to the renewable energy development in China. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 4033–4043. [Google Scholar]

- Saribulut, L.; Ok, G.; Ameen, A. A case study on national electricity blackout of Turkey. Energies 2023, 16, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Cao, N. A control measure for interconnection power grid cascading failure based on heterogeneous cellular automata. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2020, 48, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carreras, B.A.; Colet, P.; Reynolds-Barredo, J.M.; Gomila, D. Assessing blackout risk with high penetration of variable renewable energies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 132663–132674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Wu, Z. Performance and reliability of electrical power grids under cascading failures. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2011, 33, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; He, F.; Zhang, X.; Xia, D. An improved OPA model and the evaluation of blackout risk. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2009, 24, 814–823. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Hao, Q.; Liu, J.; Meng, F.; Hu, B.; Xue, Y. Critical branch identification of cascading failure based on social network influence analysis. Adv. Technol. Electr. Eng. Energy 2022, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Xia, C.; Zhong, M.; Guan, L. Critical line identification of power grid based on fault chain clustering algorithm. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2022, 41, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, X.; Liu, Q.; Cao, L.; Ding, N. Key line identification and cascading fault prediction for the grid containing large-scale wind power. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 38, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, P.; Jiang, X.; Yang, G.; Lv, W. Fast screening method for important transmission lines in electrical power system. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Vulnerability Assessement and Differentiated Planning on Complex Power Grid to Prevent Blackouts. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 1 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bompard, E.; Pons, E.; Wu, D. Extended topological metrics for the analysis of power grid vulnerability. IEEE Syst. J. 2012, 6, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Yu, X. A maximum-flow-based complex network approach for power system vulnerability analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2011, 9, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetta, R.; Patelli, E. Assessment of power grid vulnerabilities accounting for stochastic loads and model imprecision. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 98, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, R.; Duan, J.; Cheng, W. Comprehensive weight method based on game theory for identify critical transmission lines in power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 124, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Shen, C.; Liu, F.; Mei, S. Fast screening of vulnerable transmission lines in power grids: A pagerank-based approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 10, 1982–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shao, J.; Yang, Q.; Sun, Z. Profitleader: Identifying leaders in networks with profit capacity. World Wide Web 2019, 22, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Li, Q.; Xiao, Y.; He, X.; Tong, Y.; Hu, P.; Zeng, Z. Power system vulnerability analysis based on topological potential field theory. Phys. Scr. 2021, 96, 125227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social Network | Power Network | Power System-Related Network |

|---|---|---|

| Entity | Transmission Line | Node |

| Inter-entity Connection | Inter-line linkage | Line |

| Ranking | IPL | PR | CEI | MF | EB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | 46 | 35 | 26 | 24 |

| 2 | 33 | 14 | 14 | 37 | 25 |

| 3 | 37 | 37 | 23 | 30 | 26 |

| 4 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 33 | 3 |

| 5 | 41 | 35 | 37 | 29 | 8 |

| 6 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 38 | 9 |

| 7 | 39 | 10 | 13 | 27 | 27 |

| 8 | 42 | 39 | 19 | 7 | 6 |

| 9 | 27 | 41 | 38 | 36 | 23 |

| 10 | 9 | 34 | 39 | 20 | 31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Han, G.; Lv, D.; Sun, G. Identification of Important Lines in Power Grids Based on Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm. Energies 2025, 18, 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246628

Liu X, Han G, Lv D, Sun G. Identification of Important Lines in Power Grids Based on Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246628

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinghua, Guangyang Han, Dongfei Lv, and Guowei Sun. 2025. "Identification of Important Lines in Power Grids Based on Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm" Energies 18, no. 24: 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246628

APA StyleLiu, X., Han, G., Lv, D., & Sun, G. (2025). Identification of Important Lines in Power Grids Based on Improved ProfitLeader Algorithm. Energies, 18(24), 6628. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246628