Abstract

Anaerobic digestion (AD) of poultry manure often faces ammonia inhibition due to its high nitrogen content. This study investigated a combined strategy involving mild thermal hydrolysis pretreatment and bioaugmentation with ammonia-acclimatised inoculum to enhance methane production and process stability under ammonia-stressed conditions. Batch biomethanation efficiency assays were first conducted to evaluate the effect of different hydrolysis conditions (55–70 °C, 30–60 min) on substrate methane yields and biodegradability. The optimal condition (70 °C for 60 min) increased methane potential by 8.7% compared to the untreated substrate. In addition, a mesophilic continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR) experiment was conducted using both non-hydrolysed and thermally hydrolysed poultry manure under hydraulic retention times of 25 and 30 days, across four operational phases: steady-state, ammonia toxicity, bioaugmentation recovery, and increased organic loading rate. CSTRs were subjected to ammonia stress (6500 mg NH4+-N L−1) to assess the effectiveness of an acclimatised bioaugmentation inoculum. Methane yields recovered up to 93% and 100% of pre-inhibition and ammonia-toxicity levels, respectively, accompanied by process stability while reaching 7280 mg NH4+-N L−1. The synergistic application of hydrolysis and bioaugmentation significantly improved substrate conversion and overall AD robustness. This integrated approach provides a viable and scalable strategy for optimising AD performance of nitrogen-rich feedstocks, enabling its future application in AD plants.

1. Introduction

The continuous growth of the global population has intensified the demand for food production [1], thereby leading to an expansion of agricultural and livestock activities worldwide. This increasing agricultural output is accompanied by the generation of large volumes of organic residues, which, if not managed properly, pose significant environmental challenges [2]. One of the most well-established technologies regarding the treatment of such organic waste is the AD process. AD is a biological process where microorganisms degrade organic matter under oxygen-free conditions. AD simultaneously enables renewable energy generation in the form of biogas (~60% CH4, 40% CO2, trace gases) [3] and reduces the organic load of waste, mitigating environmental pollution. In addition, the possibility of digestate utilisation as a potential biofertilizer enables nutrient recycling, positioning AD as a key technology for advancing circular economy strategies in the agri-food sector [4].

In recent years, poultry production has shown remarkable growth worldwide, and is expected to keep growing, as the projected increase for meat and eggs is 21% and 16.6%, respectively, by the end of 2034 [5]. As a result, large quantities of poultry manure are produced, requiring proper treatment and management. Poultry manure constitutes a promising substrate for AD, due to its high protein content and estimated methane yield in the range of 200–360 mL CH4 g−1 VS [6].

Pretreating substrates prior to AD has the potential to accelerate the hydrolysis of complex organic matter and improve overall AD process performance. Extensive research has been conducted on the application of chemical, physical, and biological pretreatments that are effective in altering the physicochemical structures and improving the biodegradability of various substrates. Among these, ultrasonication, homogenization, and thermal hydrolysis have shown effectiveness for substrates with high protein content, such as poultry manure [7]. However, these pretreatments, especially conventional thermal hydrolysis, which is typically conducted at elevated temperatures (>100 °C), often increase the operational cost of AD due to higher energy requirements. In contrast, mild thermal hydrolysis performed at lower temperatures (50–80 °C) requires significantly less energy and can often utilise residual heat recovered from combined heat and power (CHP) units in biogas plants, thus minimizing the additional operational cost of this method [8,9]. Furthermore, the application of mild thermal hydrolysis enhances solubilisation of organic compounds and methane yield [10], while simultaneously contributing to feedstock decontamination, which may affect the AD process [11]. Thus, this pretreatment represents a potentially promising strategy to improve the AD of poultry manure.

Despite these benefits, thermal hydrolysis also increases nitrogen release, thereby influencing the total ammonium nitrogen (TAN) and free ammonia nitrogen (FAN) levels in subsequent AD stages [12]. Thus, the use of poultry manure in the AD process poses significant challenges due to its high nitrogen content [13]. Poultry manure contains elevated levels of proteins, uric acid, and other nitrogenous compounds that release ammonia during hydrolysis [14]. As a result, high ammonia concentrations can inhibit methanogenic activity and compromise process stability by disturbing the methanogenic microbiome [15]. In severe cases, provided the AD process does not collapse completely, methane production yield can decrease by more than one-third of the expected methane potential, limiting the efficient utilisation of poultry manure in full-scale AD plants [16].

Several strategies have been proposed to mitigate ammonia inhibition in AD systems. Conventional approaches include dilution with water and co-digestion with carbon-rich substrates to increase the C/N ratio and retain a balance in the AD process [17,18]. However, the practical application of such strategies, which are cost-expensive and time-consuming, is also often constrained by limited availability of suitable co-substrates and the overall cost [19]. This limitation hinders the ability to adjust the feeding mixture appropriately, resulting in feedstock storage for extended periods. Such storage conditions can result in organic matter loss and generate fluctuations in the organic loading rate (OLR), ultimately decreasing the overall energy recovery efficiency at a constant hydraulic retention time (HRT) [20,21]. Other approaches include physicochemical methods such as ammonia stripping, adsorption using ion-exchange materials, or chemical precipitation [19,22]. While these can reduce TAN concentrations, they often increase operational costs and process complexity [23,24], thus compromising both the energy efficiency and the economic feasibility of AD systems. These limitations collectively underline the need for alternative solutions that can stabilise and even improve the AD process without compromising the environmental and economic outputs of the full-scale AD plants.

One promising approach is bioaugmentation, where acclimatised microbial communities are introduced into the reactor to enhance process stability under inhibitory conditions [25]. Bioaugmentation has been successfully applied to overcome challenges such as high OLRs, accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFA), and degradation of recalcitrant compounds, demonstrating its versatility as a process intensification tool [26]. In the context of nitrogen-rich substrates such as poultry manure, the primary advantage of bioaugmentation is its capacity to mitigate ammonia inhibition and stabilise methanogenic pathways, particularly by reinforcing hydrogenotrophic methanogens that are more tolerant to elevated ammonia concentrations [27,28]. Moreover, bioaugmentation accelerates the ammonia acclimatisation period and facilitates rapid recovery following inhibitory shocks, thereby preventing long-term process destabilization [16].

The aforementioned beneficial effects highlight the importance of carefully evaluating the combination of pretreatment methods and microbial community adaptation to maximise methane production while maintaining process stability. Despite increasing nitrogen release, mild thermal hydrolysis can be a valuable tool, combined with bioaugmentation, to improve substrate solubilisation and overall AD performance. In contrast to conventional mitigation strategies that aim to reduce or remove ammonia prior to or during AD, the present study targets stable operation under retained high ammonia concentrations, in order to simultaneously sustain and improve methane production while also generating a nitrogen-rich digestate suitable for potential subsequent nutrient recovery and biofertilizer/biostimulant production. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have simultaneously investigated the combined application of mild thermal hydrolysis and bioaugmentation for the anaerobic digestion of poultry manure.

The overall aim of this study was to enhance methane production from poultry manure in mesophilic AD through the combined application of mild thermal hydrolysis and a robust bioaugmentation strategy with an ammonia-acclimatised inoculum. To achieve this aim, the effect of thermal hydrolysis was assessed under different operating conditions on TAN release and methane potential, to determine the most suitable poultry manure pretreatment conditions for the CSTR experiments. The most promising conditions were then applied to the feedstock used in the CSTR reactors, which were subsequently subjected to extremely high ammonia stress (>6500 mg NH4+-N L−1), to induce ammonia inhibition conditions. Bioaugmentation with ammonia-acclimatised inoculum was then tested as a stabilization and enhancement strategy under these conditions. Finally, a secondary aim was to assess continuous AD process robustness, adaptive capacity, and enhanced performance of the already bioaugmented CSTR reactor at extremely high ammonia concentrations (7280 mg NH4+-N L−1), by increasing the OLR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock and Inoculum

The inoculum was retrieved from a full-scale mesophilic (37 ± 1 °C) biogas plant in northern Greece. In order to reduce its residual methane production, it was stored under anaerobic conditions at 37 ± 1 °C for seven consecutive days without feeding. Two different poultry manure batches (i.e., PM1 and PM2) were retrieved separately from an egg production poultry farm in northern Greece and used as substrates for the thermal hydrolysis process (PM1) and the CSTR experiment (PM2). Prior to use, the poultry manures were diluted with water (1:1, v/v) and sieved to remove solid particles with a diameter greater than 3 mm. Finally, they were stored at −20 °C until used in the experiments. The characteristics of the inoculum and the substrates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inoculum and substrates characteristics.

2.2. Mild Thermal Hydrolysis

The hydrolysis experiment aimed to identify the most suitable thermal pretreatment conditions for application to the CSTR substrate, while also evaluating the potential TAN increase during the process. Two sets of mild thermal hydrolysis were performed at 55 °C and at 70 °C, respectively, in a standard incubator (Binder BD 260, Tuttlingen, Germany). Initially, 1600 g of poultry manure were distributed to eight 1 L glass bottles and sealed tightly. The incubator was set to 55 °C or 70 °C and four glass bottles containing the poultry manure were placed inside. After 30 min, two of the bottles were removed from the incubator, whilst the other two were removed after a total of 60 min. All the bottles from the two mild thermal hydrolysis experiments were allowed to cool at room temperature and stored at −4 °C.

2.3. Anaerobic Experimental Setup

2.3.1. Biomethanation Efficiency Experiment

To assess the effect of hydrolysis on AD efficiency, 18 batch reactors were prepared using PM1 and four differently hydrolysed substrates (HPM1) to identify the treatment yielding the highest methane production [29]. Glass bottles with an operating volume of 150 mL and a total volume of 321 mL were used for the experiment. The batch reactors were filled with inoculum and the corresponding substrate, to reach a substrate-to-inoculum ratio of 1 to 1.5 in terms of VS, then deionised water was added to reach the operating volume of 150 mL (Table 2). Blank reactors, containing only inoculum and deionised water, were used to subtract the residual methane production. To achieve anaerobic conditions, a gas mixture of N2/CO2 (80/20, v/v) was used to flush all batch reactors, which were then sealed with rubber stoppers and aluminium caps. All treatments were prepared in triplicate. The reactors were incubated at 37 ± 1 °C and manually mixed once per day. An additional nine batch reactors were similarly prepared, using hydrolysed and non-hydrolysed PM2 to identify the other substrate’s methane production efficiency [30] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Batch reactor treatments.

2.3.2. Acclimatisation of Bioaugmentation Inoculum

The acclimatisation of the methanogenic inoculum to extremely high ammonia levels (up to 6500 mg NH4+-N L−1) was achieved with the stepwise exposure of the inoculum to increasing ammonia concentrations [31] (Table 3). Glass bottles with an operating volume of 600 mL and total volume of 2290 mL were used for the acclimatisation process. Each batch reactor contained 400 mL of inoculum, 102 mL of original substrate mixed with 4 g of D-glucose (C6H12O6⋅H2O, Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands) and 98 mL of deionised water. The targeted ammonia concentration for each step was achieved with the addition of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) and the reactors were incubated at 37 ± 1 °C. The final acclimatised microbial culture was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min under anaerobic conditions to increase its concentration fivefold [32] and create the ammonia-tolerant bioaugmentation inoculum used in the CSTR reactors bioaugmentation experiments.

Table 3.

Stepwise increase of ammonia concentration in batch reactors.

2.3.3. CSTR Reactor Experiment

The final experimental stage was conducted in three identical lab-scale CSTR reactors (i.e., R1, R2 and R3) with a total and operating volume of 2 L and 1.5 L, respectively. Each reactor was equipped with an inox spiral heat exchanger circulating warm water to retain the temperature in the mesophilic range (37 ± 0.1 °C). The operation of the reactors began by adding inoculum, up to their operating volume and was divided into four experimental phases (Table 4). PI: Operation of the reactors until steady state was achieved, signified by the methane yield not varying by more than 10% for at least ten consecutive days [33]. PII: Substitution of 55% of the reactors’ operating volume (830 mL) with fresh substrate to increase the ammonia concentration and induce ammonia toxicity conditions. PIII: Bioaugmentation with 180 mL of the ammonia-acclimatised microbial culture, effectively replacing 12% of the CSTR reactors’ operating volume [32]. PIV: Under steady state, increase of the OLR of R2, to evaluate AD process robustness, adaptive capacity and enhanced performance of the already bioaugmented CSTR reactor (R2) at extremely high ammonia concentrations. Consistent with CSTR methodological practice, the phase transitions as well as the impact of ammonia shock, bioaugmentation, and OLR increase were evaluated through sequential quasi-steady-state phase comparisons within the same reactors, whereby each phase served as its own internal control under otherwise identical operational conditions, allowing reliable attribution of process responses.

Table 4.

CSTR operating conditions.

2.4. Analytical Methods

TS, VS and TAN were determined in accordance with standard methods [34]. For the calculation of FAN, Equation (1) was used:

where is the chemical equilibrium constant between free ammonia and ammonium ion, equal to 1.29 × 10−9 in the mesophilic range (37 °C), and is applied in AD systems under these conditions [35]. A digital bench pH meter (JENWAY 3520, Cole-Parmer, Essex, UK) was used to perform measurements of the pH value of the solutions. Biogas volume was monitored by using water displacement gas counters in the CSTR setup, whereas for the composition, a gastight syringe equipped with a pressure lock and an attached needle was used to obtain biogas samples almost daily from the headspace of the reactors. Then, the gas samples were injected into a gas chromatograph (GC-2010plusAT, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD), to determine the biogas composition [29]. The analysis of VFA samples was performed with a gas chromatograph (GC-2010plusAT, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) [33].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the experimental data was performed with the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA method). This method was used mainly for estimating standard errors, standard deviations, and the analysis included descriptive statistics and mean values. Differences were evaluated with Tukey’s least-significant-difference (significant when p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics v.29.0 software.

ANOVA was applied exclusively to batch experimental datasets, where all treatments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), while CSTR reactor data represent time-series measurements obtained from single reactors. The standard deviation bars presented for CSTR methane yields correspond solely to analytical triplicates of gas measurements at each sampling point and do not represent reactor replication.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Batch Experiments

3.1.1. Effect of Hydrolysis on Ammonia Profile

The results of the mild thermal hydrolysis process of PM1 showed that TAN and pH increased alongside temperature and duration of thermal hydrolysis increase, from 55 to 70 °C, and 30 to 60 min, respectively (Table 5). The maximum TAN concentration, which was statistically higher (p < 0.05) than all the other treatments, was achieved at 70 °C for 60 min. Specifically, a 12% increase in TAN was observed compared to the untreated PM1, suggesting enhanced degradation of organic nitrogen compounds and protein matter during thermal pretreatment, which is consistent with previous reports evaluating ammonia release at elevated temperatures [12,36]. This moderate rise in TAN indicates that the applied hydrolysis conditions promoted organic nitrogen degradation, thus providing a more degradable substrate for the AD process [37].

Table 5.

Hydrolysed substrate characteristics.

3.1.2. Effect of Hydrolysis on Biomethanation Efficiency

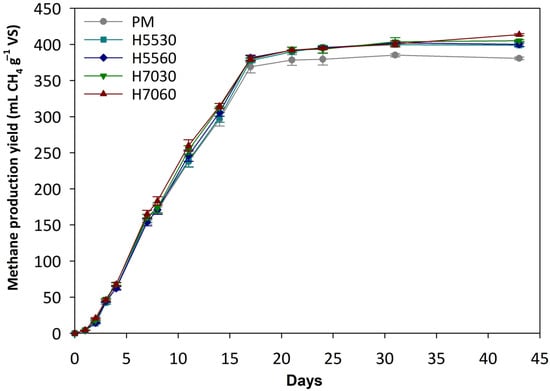

Methane production for all treatments began after a short lag period and exhibited similar increased daily production rates until approximately day 17 (Figure 1). Notably, more than 92% of the total methane yield was achieved within the first ~17 days across all treatments, followed by gradual stabilization with minor increases until day 43. Among the treatments, H7060 demonstrated enhanced production rate and yield up to day 17, and similarly, after day 31. Specifically, this treatment, using poultry manure pre-hydrolysed at 70 °C for 60 min, resulted in the highest cumulative methane yield (413.17 ± 1.74 mL CH4 g−1 VS), which was statistically higher (p < 0.05) compared to the other pre-hydrolysed treatments. The effectiveness of pre-hydrolysis at 70 °C for 60 min highlights the importance of both temperature and retention time in improving the biodegradability of organic matter, thereby facilitating AD process [12]. Treatments H5530, H5560, and H7030 yielded 398.44 ± 2.86, 399.93 ± 3.90, and 404.41 ± 1.75 mL CH4 g−1 VS, respectively, with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) between them. In addition, the PM (control) exhibited the lowest methane production yield (380.26 ± 2.12 mL CH4 g−1 VS) among all the tested treatments (p < 0.05), reflecting that thermal hydrolysis pretreatment enhanced the methane yield of poultry manure. Thus, the findings support that thermal pretreatment improved the AD efficiency of nitrogen-rich organic waste, such as poultry manure, under the conditions examined.

Figure 1.

Methane production yield per gram of VS for the examined treatments. Standard deviation is represented by the error bars for each treatment.

3.1.3. TAN, pH, FAN Variations

A clear trend of increasing TAN and FAN following AD across all treatments was observed (Table 6), reflecting the degradation of organic nitrogen and the accumulation of ammoniacal compounds in the soluble phase. This increase was more intense in treatments involving thermal pre-hydrolysis at higher temperatures and longer durations. Treatment H7060 (70 °C for 60 min) exhibited the highest increase in TAN (+19.69%) compared to the other treatments, reaching a final value of 2240 ± 29.89 mg NH4+-N L−1, indicating the most effective degradation of the organic nitrogen fraction and a corresponding increase in TAN due to thermal hydrolysis [36]. Similarly, cand was the highest among treatments. On the other hand, PM treatment displayed the lowest increase in TAN (+3.17%) and FAN concentration at the end of the experiment (63.85 mg NH3-N L−1). In addition, the resulting FAN concentrations under the tested conditions and across all treatments remained at low levels (<200 mg NH3-N L−1), which is often reported as a threshold for methanogenesis inhibition [13,38], indicating that the AD process proceeded without a profound disturbance to methanogenic activity, as reflected in the consistent performance results. All treatments using hydrolysed poultry manure showed a positive correlation between the intensity of thermal pretreatment (temperature and duration) and the efficiency of organic nitrogen degradation, accompanied by a gradual increase in pH.

Table 6.

Results of TAN, FAN, and pH in the batch reactors at the beginning and at the end of the experiment.

The observed increase in pH after AD, particularly in treatments with high methane yields, can be attributed to the combined effects of VFA consumption and ammonia accumulation, which together acted as a buffering system and resulted in a more alkaline environment [13]. These results support the selection of H7060 as the optimal pretreatment method for the CSTR experiment’s substrate, as it achieved the highest methane yield, nitrogen release, final pH, and FAN values.

3.2. CSTRs Experiment

3.2.1. Reactor Performance

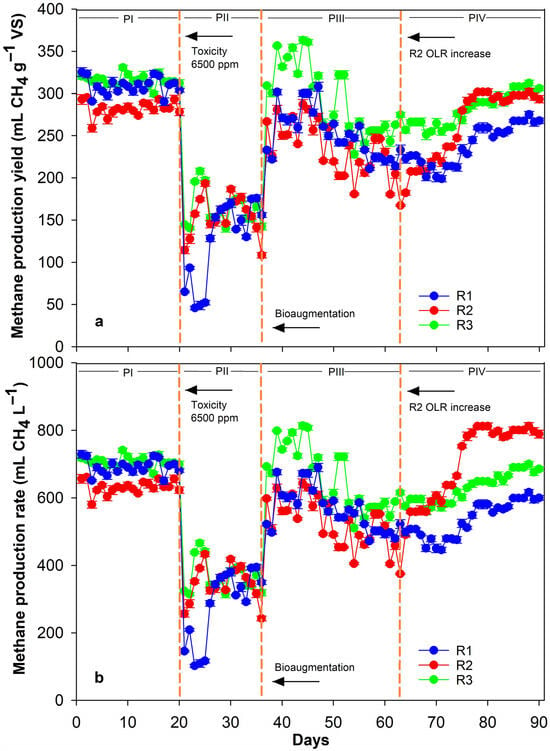

During the initial phase (PI), all reactors exhibited consistent methane production yields and rates, indicating a well-established AD process (Figure 2). Average methane production yields were 308.72 ± 9.97, 282.11 ± 8.70, and 315.65 ± 6.58 mL CH4 g−1 VS, while methane production rates were 391.54 ± 22.32, 631.93 ± 19.49, and 706.98 ± 14.75 mL CH4 L−1 d−1 for R1, R2, and R3, respectively. A quasi-steady state [33] was achieved before proceeding to the next phase. On average, R1, R2, and R3 reached 91.32%, 79.97%, and 89.47%, respectively of their corresponding biomethanation efficiency (i.e., 338.07 ± 12.22 and 352.78 ± 15.37 mL CH4 g−1 VS, for CPM and CHPM, respectively), indicating a well-performed continuous AD process.

Figure 2.

Methane production yield (a) and rate (b) throughout the duration of the CSTRs experiment (Phases I–IV). Standard deviation is represented by the error bars.

During PII (ammonia increased at 6500 mg NH4+-N L−1), all reactors exhibited an immediate sharp decline in methane yield that was at least 55.5% compared to PI, with R1 exceeding 85% (Figure 2). This result clearly showed that a strong ammonia-derived inhibition was established in all three CSTR reactors. The partial yield recovery for reactors R2 and R3, compared to R1 was possibly due to the increased availability of the organic matter provided by the hydrolysed substrate [37,39,40]. Between days 25 and 33, all reactors had a similar and stable methane production, which mimicked a typical inhibited steady state [28]. However, on days 33 to 36, a consecutive decline in methane production was observed, which was a profound indication of a complete AD process collapse, prompting the bioaugmentation phase.

Following the introduction of bioaugmentation inoculum (PIII), all reactors significantly recovered their methane yields by 81.73%, 83.00% and 92.80%, compared the non-inhibited methane yield during PI for R1, R2 and R3, respectively. This is a clear indication that bioaugmentation, not only prevented complete process failure, but also significantly enhanced methane recovery. Previous studies have reported considerable methane recovery of up to 97–100% following bioaugmentation [16,28]. In the present study, comparable recovery efficiencies were achieved at higher TAN concentrations, highlighting the resilience and adaptive capacity of the acclimatised microbial consortium, whilst overall process stabilisation based on the observed recovery. Even under extreme ammonia concentrations (approx. 6500–7100 mg NH4+-Ν L−1), methanogenic activity was successfully restored, demonstrating the resilience of the ammonia-acclimatised inoculum. Additionally, methane production yield after bioaugmentation, recovered by 50.97%, 78.66% and 100% for R1, R2 and R3, respectively, compared to the inhibited methane production during PII. Interestingly, R2 had a lower methane yield increase compared to R3 (using the same hydrolysed substrate), which can be attributed to the shorter HRT (i.e., 25 d) that slowed the bioaugmentation process establishment resulting in a “washout effect”, typically occurring in continuous reactors [31].

During PIV, following the OLR increase, R2 exhibited a progressive enhancement in methane yield, stabilizing around 280–300 mL CH4 g−1 VS. This indicates that R2 tolerated the higher substrate load without process instability, consistent with improved metabolic adaptability of the bioaugmented community in contrast to its decreased performance during PI, PII, PIII. This was also reflected in the significant increase of methane production rate (up to 29%) in R2 compared to R3, until the end of the experiment (Figure 2b). In contrast to R2 and R3, R1 displayed lower but steady increasing yields (up to 260 mL CH4 g−1 VS), consistent with slower microbial adaptation [25]. After day 75, all reactors exhibited increasing methane yields, confirming sustained acclimatisation and long-term microbial stabilisation. In total, PIV highlights that once bioaugmented consortia are fully adapted to extreme ammonia levels (>7000 NH4+-N L−1), a controlled OLR increase in a low-HRT system can enhance methane productivity, also reported by other studies [41,42,43].

Overall, the bioaugmentation with ammonia-acclimatised inoculum significantly improved methane production recovery, stability, and enhanced microbial adaptation in reactors exposed to extreme ammonia concentrations (approx. 6500–7100 mg NH4+-N L−1). The best overall performance was achieved in R3, where the combination of hydrolysis pretreatment and higher HRT provided greater resilience to ammonia inhibition. These findings demonstrated the efficiency of an integrated approach, with pretreatment and bioaugmentation, to mitigate ammonia toxicity in the AD of nitrogen-rich poultry manure and increase the methane output of the process by maximizing the organic matter conversion.

3.2.2. VFA, pH, and TAN in CSTRs

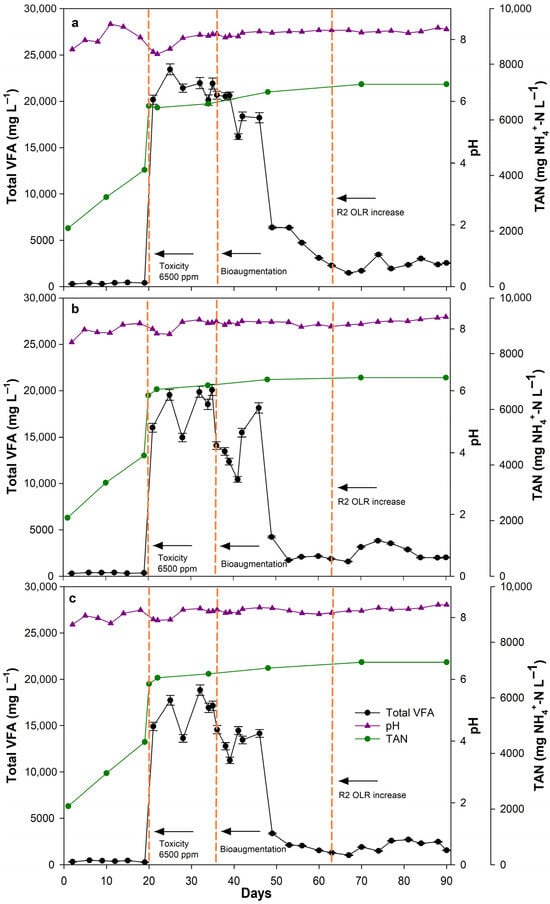

During PI, total VFA levels remained low in all reactors (Figure 3), averaging 379.55 ± 63.67, 357.43 ± 40.22, and 394.31 ± 80.04 mg VFA L−1 for R1, R2, and R3, respectively significantly lower than the proposed threshold of 1500 mg VFA L−1 for CSTR reactor optimal operation [44]. These values, combined with methane production results, indicate efficient substrate degradation and a balanced methanogenic microbiome [18]. TAN concentrations gradually increased from the initial 2100 mg NH4+-N L−1 to 4200–4400 mg NH4+-N L−1 toward the end of this phase, due to the inserted poultry manure’s TAN levels. The pH remained approximately within the range of 7.70–7.95, indicating effective buffering capacity and microbial activity leading to optimal conditions for methanogenesis [45]. The stable operation and low VFA accumulation across all reactors corresponded with the high methane yields recorded during this phase (Figure 2a), indicating a well-established and balanced AD process [46].

Figure 3.

Total VFA, pH and TAN values throughout the CSTR reactor experiment ((a): R1, (b): R2, (c): R3).

During PII, all reactors exhibited a rapid and significant accumulation of VFA, which triggered a severe inhibitory shock, reaching maximum concentrations of 23,445.69 ± 603.9 (R1), 20,090.71 ± 602.72 (R2), and 18,826.53 ± 564.80 mg VFA L−1 (R3). FAN levels reached approximately 1000–1400 mg NH3–N L−1 across all reactors, exceeding concentrations commonly associated with ammonia inhibition [13,38]. The sudden accumulation of VFA coincided with the sharp decline in methane production yields and rates (Figure 2), indicating that elevated FAN concentrations inhibited methanogens and possibly disrupted the syntrophic balance between acidogenesis and methanogenesis, causing transient accumulation of intermediates as also reported in previous studies on ammonia-stressed AD systems [47,48]. R1 exhibited higher VFA accumulation, specifically 16.7% and 24.24%, compared to R2 and R3, respectively, showing slower recovery and possibly suggesting that hydrolysis pretreatment of PM2 mitigated the severity of the inhibition by improving substrate availability and microbial resilience in R2 and R3 [40,49].

After bioaugmentation (PIII), all reactors showed significant improvement in process stability, and a rapid decline in VFA concentrations. Specifically, by day 49, total VFA levels decreased to 6385.79 ± 127.72 (R1), 4239.42 ± 97.51 (R2), and 3371.48 ± 67.43 mg VFA L−1 (R3). Such a reduction in VFA has been associated in previous studies with the reestablishment of aceticlastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogenic pathways, as well as the restoration of syntrophic cooperation between microbial consortia [50,51]. This association could potentially explain the trend observed in this study; however, to verify this interpretation, molecular or microbiological community analyses would be required. The most substantial reduction (82.09%), among reactors, was observed in R3, corresponding with its high methane yield and rate recovery (Figure 2a), which can be attributed to the bioaugmentation inoculum that improved the consumption of accumulated VFA [31]. During this phase, while FAN levels were approximately 1000–1500 mg NH3–N L−1, methane yields significantly increased across all reactors, supporting that bioaugmentation with the ammonia-acclimatised inoculum successfully stabilised the process and enabled the methanogenic population to maintain robust activity under extreme ammonia levels (TAN > 7000 mg NH4+-N L−1).

In the final phase (PIV), the OLR increase in R2, induced a short-term accumulation of total VFA, increasing to approximately 3822.65 mg ± 87.92 mg VFA L−1 on day 74, followed by stabilization around 2000 mg VFA L−1 toward the end of the experimental period. The temporary fluctuation of VFA in R2 reflected the metabolic adaptation of the microbial community to increased substrate availability under TAN and FAN concentrations of approximately 7140 mg NH4+-N L−1 and 1300–1600 mg NH3-N L−1, respectively. This indicates that the methanogenic population efficiently metabolised the additional intermediates once acclimated. Consequently, methane production yield and rate in R2 progressively increased (Figure 2), likely due to enhanced microbial activity and the improved substrate-to-biomass ratio resulting from the OLR increase. This positive response by R2 compared to its performance in previous phases demonstrated that the acclimatised microbial community could sustain higher substrate loads without causing process imbalance. R1 and R3, which operated under unchanged conditions from PIII and onward, exhibited stable performance during this phase, with an average VFA concentration of 2359.18 and 1934.38 mg VFA L−1, respectively, despite extreme TAN (up to 7280 mg NH4+-N L−1) and FAN (up to 1800 mg NH3-N L−1) levels, consistent with enhanced process stability under ammonia stress. Comparable studies on ammonia-tolerant bioaugmentation have reported similar recovery patterns under high TAN-FAN levels [16,28,52], supporting the observed resilience of the system. These observations in R2 highlight that bioaugmentation has created a robust AD process, with long-lasting effects, that allowed to further increase the methane production without compromising the overall process stability. Overall, these results support that the combined strategy of hydrolysis pretreatment and bioaugmentation with acclimatised inoculum significantly enhances the stability and resilience of AD process of nitrogen-rich poultry manure.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the combined application of mild thermal hydrolysis pretreatment and bioaugmentation with ammonia-acclimatised inoculum is an effective strategy to overcome extreme ammonia inhibition in the continuous AD of nitrogen-rich poultry manure. Mild thermal hydrolysis at 70 °C for 60 min enhanced substrate biodegradability, resulting in the highest methane yield during batch assays. Bioaugmentation with ammonia-acclimatised inoculum successfully restored methane production, achieving up to 93% and 100% recovery of pre-inhibition and ammonia-toxicity yields, respectively under extreme ammonia levels (>7000 mg NH4+-N L−1). The results of this study indicate several avenues for future research and practical application. Further investigations should examine the long-term operational stability and microbial community dynamics of hydrolysed and bioaugmented systems, as well as assess the scalability and economic feasibility of this integrated approach in full-scale AD plants. Beyond enhanced methane recovery, the resulting nitrogen-rich digestate represents a valuable co-product with potential for nutrient recovery and valorisation. Given its elevated ammonium and residual organic content, such digestate can be processed into biofertilizers and biostimulants, contributing to nutrient recycling and aligning with the principles of the circular economy. Integrating bioaugmentation strategies with digestate valorisation could therefore enable a closed-loop, resource-efficient system that supports renewable energy generation, sustainable agriculture, and greenhouse gas mitigation within the broader bioenergy framework. Thus, a full techno-economic, energy feasibility, and scale-up assessment of the proposed integrated strategy at industrial scale is identified as a critical objective for future research. This assessment requires long-term operational data, and could include thermal pretreatment, large-scale production of ammonia-acclimatised inoculum, operational requirements, potential coupling with digestate nitrogen recovery processes, and energy input calculations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.T., A.A.L., I.A.F. and T.A.K.; methodology, C.A.T., A.A.L., I.A.F. and T.A.K.; investigation, C.A.T. and A.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.T. and A.A.L.; writing—review and editing, C.A.T., A.A.L., D.S.P., M.-A.T., S.D.K., V.K.F., I.A.F. and T.A.K.; supervision, I.A.F. and T.A.K.; project administration, T.A.K.; funding acquisition, T.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project “Strengthening the industrial symbiosis in the value chain of anaerobic digestion” (ALIVE) is implemented in the framework of “(Strategy for Excellence in Universities & Innovation) (ID 16289)—SUB1.1. Clusters of Research Excellence (CREs)” under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0” funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (Implementation Body: ΕΔ ΕΣΠA ΥΠAΙΘA), (Project Number: ΥΠ3ΤA-0560157).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred-tank reactor |

| CHP | Combined heat and power |

| TAN | Total ammonium nitrogen |

| FAN | Free ammonia nitrogen |

| OLR | Organic loading rate |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acids |

| TS | Total solids |

| VS | Volatile solids |

| TKN | Total Kjeldahl nitrogen |

| P | Phosphorus |

| TCD | Thermal conductivity detector |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Shankar, N.D. Rethinking Global Food Demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 921–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Bhatia, T.; Sindhu, S.S. Sustainable Approach for Management of Organic Waste Agri-residues in Soils for Food Production and Pollution Mitigation. In Environmental Nexus Approach: Management of Water, Waste, and Soil; CRC Press: London, UK, 2024; pp. 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karne, H.; Mahajan, U.; Ketkar, U.; Kohade, A.; Khadilkar, P.; Mishra, A. A review on biogas upgradation systems. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034; OECD: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, W.; Wang, X.; Gabauer, W.; Ortner, M.; Li, Z. Tackling ammonia inhibition for efficient biogas production from chicken manure: Status and technical trends in Europe and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacleto, T.M.; Kozlowsky-Suzuki, B.; Björn, A.; Yekta, S.S.; Masuda, L.S.M.; de Oliveira, V.P.; Enrich-Prast, A. Methane yield response to pretreatment is dependent on substrate chemical composition: A meta-analysis on anaerobic digestion systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Yılmaz, C. Design and optimization of multigeneration biogas power plant using waste heat recovery System: A case study with Energy, Exergy, and thermoeconomic approach of Power, cooling and heating. Fuel 2022, 324, 124779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, M.; Hajinezhad, A.; Naseri, A.; Noorollahi, Y.; Moosavian, S.F. An overview of renewable energy technologies for the simultaneous production of high-performance power and heat. Futur. Energy 2023, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Huang, H.; Dai, J.; Chen, G.-H.; Wu, D. Impact of low-thermal pretreatment on physicochemical properties of saline waste activated sludge, hydrolysis of organics and methane yield in anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, P.; Balasundaram, G.; Tyagi, V.K.; Atabani, A.; Suthar, S.; Kazmi, A.; Štěpanec, L.; Juchelková, D.; Kumar, A. Principles and potential of thermal hydrolysis of sewage sludge to enhance anaerobic digestion. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, P.L.; Udugama, I.A.; Gernaey, K.V.; Young, B.R.; Baroutian, S. Mechanisms, status, and challenges of thermal hydrolysis and advanced thermal hydrolysis processes in sewage sludge treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; McAdam, E.; Zhang, Y.; Heaven, S.; Banks, C.; Longhurst, P. Ammonia inhibition and toxicity in anaerobic digestion: A critical review. J. Water Process. Eng. 2019, 32, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qiao, W.; Zhang, J.; Dong, R. Process Performance and Functional Microbial Community in the Anaerobic Digestion of Chicken Manure: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qiao, W.; Westerholm, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, R. High rate methanogenesis and nitrogenous component transformation in the high-solids anaerobic digestion of chicken manure enhanced by biogas recirculation ammonia stripping. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotidis, I.A.; Treu, L.; Angelidaki, I. Enriched ammonia-tolerant methanogenic cultures as bioaugmentation inocula in continuous biomethanation processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Yuan, W.; Wu, D.; Yang, P.; Peng, X. Long-term evaluation of the anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and landfill leachate to alleviate ammonia inhibition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniche, I.; Hungría, J.; El Bari, H.; Siles, J.A.; Chica, A.F.; Martín, M.A. Effects of C/N ratio on anaerobic co-digestion of cabbage, cauliflower, and restaurant food waste. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 11, 2133–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, M.; Zeng, H.; Min, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G. Application of physicochemical techniques to the removal of ammonia nitrogen from water: A systematic review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgert, J.E.; Herrmann, C.; Petersen, S.O.; Dragoni, F.; Amon, T.; Belik, V.; Ammon, C.; Amon, B. Assessment of the biochemical methane potential of in-house and outdoor stored pig and dairy cow manure by evaluating chemical composition and storage conditions. Waste Manag. 2023, 168, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lithourgidis, A.A.; Firfiris, V.K.; Kalamaras, S.D.; Tzenos, C.A.; Brozos, C.N.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. Energy Conservation in a Livestock Building Combined with a Renewable Energy Heating System towards CO2 Emission Reduction: The Case Study of a Sheep Barn in North Greece. Energies 2023, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanotti, M.B.; García-González, M.C.; Szögi, A.A.; Harrison, J.H.; Smith, W.B.; Moral, R. Removing and Recovering Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Animal Manure. Anim. Manure Prod. Charact. Environ. Concerns Manag. 2020, 67, 275–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.I.; Ali, I.M.; Hassan, D.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Strategies for ammonia recovery from wastewater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2699–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, S.M.; Badalucco, L.; Cano, B.; Laudicina, V.A.; Mannina, G. Ammonium adsorption, desorption and recovery by acid and alkaline treated zeolite. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoursarbani, M.; Tideman, J.; López, M.; Abendroth, C. Bioaugmentation in anaerobic digesters: A systematic review. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzila, A. Mini review: Update on bioaugmentation in anaerobic processes for biogas production. Anaerobe 2017, 46, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsong, H.; Lianhua, L.; Ying, L.; Changrui, W.; Yongming, S. Bioaugmentation with methanogenic culture to improve methane production from chicken manure in batch anaerobic digestion. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotidis, I.A.; Wang, H.; Fiedel, N.R.; Luo, G.; Karakashev, D.B.; Angelidaki, I. Bioaugmentation as a Solution to Increase Methane Production from an Ammonia-Rich Substrate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7669–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamaras, S.D.; Vasileiadis, S.; Karas, P.; Angelidaki, I.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. Microbial adaptation to high ammonia concentrations during anaerobic digestion of manure-based feedstock: Biomethanation and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 1970–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Alves, M.; Bolzonella, D.; Borzacconi, L.; Campos, J.L.; Guwy, A.J.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.; Jenicek, P.; van Lier, J.B. Defining the biomethane potential (BMP) of solid organic wastes and energy crops: A proposed protocol for batch assays. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, M.; Vasileiadis, S.; Karpouzas, D.; Angelidaki, I.; Kotsopoulos, T. Effects of organic loading rate and hydraulic retention time on bioaugmentation performance to tackle ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yan, M.; Treu, L.; Angelidaki, I.; Fotidis, I.A. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens are the key for a successful bioaugmentation to alleviate ammonia inhibition in thermophilic anaerobic digesters. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, M.; Vasileiadis, S.; Kalamaras, S.; Karpouzas, D.; Angelidaki, I.; Kotsopoulos, T. Ammonia-induced inhibition of manure-based continuous biomethanation process under different organic loading rates and associated microbial community dynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D. (Eds.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moerland, M.J.; Bruning, H.; Buisman, C.J.; van Eekert, M.H. Advanced modelling to determine free ammonia concentrations during (hyper-)thermophilic anaerobic digestion in high strength wastewaters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Suganuma, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Kim, W.; Nakashimada, Y.; Nishida, K. Reaction Rate of Hydrothermal Ammonia Production from Chicken Manure. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 23442–23446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Dichtl, N.; Dai, X.; Li, N. Effects of thermal hydrolysis on organic matter solubilization and anaerobic digestion of high solid sludge. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenigün, O.; Demirel, B. Ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion: A review. Process. Biochem. 2013, 48, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, T.; Neubauer, P.; Junne, S. Role of Microbial Hydrolysis in Anaerobic Digestion. Energies 2020, 13, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, P.L.; Young, B.R.; Brian, K.; Baroutian, S. New insight into thermal hydrolysis of sewage sludge from solubilisation analysis. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, A.; Harun, R.; Idrus, S. Performance Monitoring of Anaerobic Digestion at Various Organic Loading Rates of Commercial Malaysian Food Waste. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 775676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, H.; Wu, J.; Kobayashi, T.; Xu, K.-Q. Performance Comparison of CSTR and CSFBR in Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste with Grease Trap Waste. Energies 2022, 15, 8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; He, S.; Kang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Xing, T.; Guo, Y.; Li, L. Effect of Organic Loading Rate and Temperature on the Anaerobic Digestion of Municipal Solid Waste: Process Performance and Energy Recovery. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 522334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Boe, K.; Ellegaard, L. Effect of operating conditions and reactor configuration on efficiency of full-scale biogas plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 52, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, G.B.; Trømborg, E.; Solli, L.; Walter, J.M.; Wahid, R.; Govasmark, E.; Horn, S.J.; Aryal, N.; Feng, L. Biofilm application for anaerobic digestion: A systematic review and an industrial scale case. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, X.; Gao, T.; Cheng, Z.; Fu, W.; Wang, S. Ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion of organic waste: A review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 3927–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, F.; Popp, D.; Weinrich, S.; Sträuber, H.; Kleinsteuber, S.; Harms, H.; Centler, F. Ammonia Inhibition of Anaerobic Volatile Fatty Acid Degrading Microbial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Treu, L.; Zhu, X.; Tian, H.; Basile, A.; Fotidis, I.A.; Campanaro, S.; Angelidaki, I. Insights into Ammonia Adaptation and Methanogenic Precursor Oxidation by Genome-Centric Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12568–12582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Filer, J. Thermal Hydrolysis to Enhance Anaerobic Digestion Performance of Wastewater Sludge. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town, J.R.; Dumonceaux, T.J. Laboratory-scale bioaugmentation relieves acetate accumulation and stimulates methane production in stalled anaerobic digesters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 100, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayeri, D.; Mohammadi, P.; Bashardoust, P.; Eshtiaghi, N. A comprehensive review on the recent development of anaerobic sludge digestions: Performance, mechanism, operational factors, and future challenges. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Mancini, E.; Treu, L.; Angelidaki, I.; Fotidis, I.A. Bioaugmentation strategy for overcoming ammonia inhibition during biomethanation of a protein-rich substrate. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).