Abstract

This study examines the economic performance of residential photovoltaic systems combined with battery storage (PV-BESS) under Poland’s net-billing regime for a single-family household without subsidy support in 10-year operational horizon. These insights extend existing European evidence by demonstrating how net-billing fundamentally alters investment incentives. The analysis incorporates real production data from selected locations and realistic household consumption profiles. Results demonstrate that optimal system configuration (6 kWp PV with 15 kWh storage) achieves 64.3% reduction in grid electricity consumption and positive economic performance with NPV of EUR 599, IRR of 5.32%, B/C ratio of 1.124 and discounted payback period of 9.0 years. The optimized system can cover electricity demand in the summer half-year by over 90% and reduce local network stress by shifting surplus solar generation away from midday peaks. Residential PV-BESS systems can achieve economic efficiency in Polish conditions when properly optimized, though marginal profitability requires careful risk assessment regarding component costs, durability and electricity market conditions. For Polish energy policy, the findings indicate that net-billing creates strong incentives for regulatory instruments that promote higher self-consumption, which would enhance the economic role of residential storage.

1. Introduction

In response to the increasing challenges related to the European Union’s energy transition strategy, the energy policies of European countries prioritize the promotion of renewable energy sources [1,2]. Photovoltaic (PV) systems are integral to global electricity production. Their increasing adoption, especially in the distributed sector, is driving a significant paradigm shift in energy management from consumer to prosumer [3,4,5]. Recent years have seen a notable increase in installed photovoltaic capacity globally [6], with Poland also experiencing this trend [7]. Poland exhibits one of the highest growth rates for prosumer photovoltaics within the European Union. As of the end of Q1 2025, Poland’s total photovoltaic installation capacity reached 21.8 GW, with prosumer micro-installations (up to 50 kW per installation) accounting for 59% of this capacity [7]. The success attributed to support programs like “Mój Prąd” (My Electricity) presents considerable challenges for grid infrastructure [3]. Distribution service providers in Poland encounter challenges in exporting surplus energy from the low-voltage grid to the medium-voltage grid, frequently resulting in voltage instability and necessitating the shutdown of inverters at individual producers [3,8].

Therefore, battery energy storage systems (BESS) are essential for the effective utilization of solar energy [9,10,11,12]. These systems alleviate the burden on local power sub-grids during periods of peak solar irradiance and enhance the efficient utilization of generated energy. Small-scale BESS, installed in residential settings generally consist of small photovoltaic panels, typically up to 5 kWp, and compact energy storage units, usually up to 13.5 kWh [13]. They accelerated the integration of new installations with distribution systems [5] and enabled maximum use of renewable energy sources [14]. Additionally, the transition from net-metering to net-billing has further influenced the dynamics of the Polish market [8]. The revised system prioritizes self-consumption rather than energy export, with surpluses being compensated at the monthly market price, generally lower than the retail energy price [3]. Research across multiple countries indicates a direct correlation between increased self-consumption and the profitability of savings and investments [8,15]. The government support program “Mój Prąd” (My Electricity), in the latest version, has been modified to emphasize the optimization of self-consumption in response to these challenges. Such subsidies are indicated as essential for the profitability of PV-BESS systems [5,15]. The economic efficiency of photovoltaic systems integrated with energy storage for residential prosumers has been extensively examined in academic research [16,17]. Recent studies have concentrated on creating methodologies that accurately consider both technical factors and complex market conditions [18,19]. Key economic indicators, including Net Present Value (NPV), Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), and Discounted Payback Period (DPBP/DPP), are commonly employed to evaluate the long-term profitability of investments [16,17,20].

This study aims to evaluate the technical and economic conditions, as well as the optimal configuration, under which an investment in a residential PV-BESS system in Poland can be effective for a private investor, without reliance on subsidy programs or selling excess production to the power grid. This restriction in modeling is a response to market changes resulting from frequent inverter shutdowns or the sale of PV energy at increasingly lower prices. This approach also originates from the need to solve the problem of significant power surpluses in Poland during periods of increased daily solar radiation and offers private investors practical guidance for optimal investment decisions, considering the unique characteristics of the Polish market, technical variability, and conservative financial assumptions. The findings may be beneficial for policymakers in formulating future strategies that promote the advancement of PV-BESS. This article also contributes to the broader academic discourse regarding the economic efficiency of these systems [3,8,16,19,21,22,23,24,25].

Our approach to the solution combines various methodologies used in previous research. This allows us to merge best practices from existing approaches while taking into account multiple factors and characteristics that have not been considered simultaneously:

- An in-depth examination of a PV-BESS system within the Polish regulatory framework, excluding subsidy support, akin to Hoppmann et al. [16]. What individualizes our study is the consideration of household operating modes and the distinction among different types of days (working days, weekends, holidays, and others). This results in a reduction or increase in efficiency consistent with actual consumption dependent on the day type. This also differentiates it from other analyses utilizing FIT (Feed-in Tariff) systems and conventional net metering [22,26], as well as from studies of systems functioning under net billing [8];

- Comprehensive technical and economic modeling. High time resolution is necessary due to the dynamic characteristics of photovoltaic production and the variability of household load. Early studies utilized hourly data [16], but recent analyses demonstrate that precise modeling of BESS operations necessitates high sub-hourly resolution to effectively capture peaks and dynamic changes [8]. This article employs an operational simulation characterized by high temporal resolution. Fifteen-minute intervals over a decade are employed, while production and consumption components are generated with minute accuracy and subsequently transformed into energy-balancing intervals. This is essential for a comprehensive analysis of the PV-BESS operation, which enhances storage utilization to optimize savings on grid energy purchases [27]. The simulated load reflects realistic and diverse device usage patterns for a household;

- Integration of uncertainty factors (stochastic photovoltaic data). This analysis uses a stochastic approach that, unlike deterministic models, estimates photovoltaic (PV) energy production for future periods using actual data from a historical dataset [28]. The data in our forecasts is drawn for subsequent years from a set of historical data. Consumption is generated randomly based on established patterns of household appliance usage taking into account the type of day. Capturing the high variability of production inherent to the Polish climate is essential for accurately comparing it with energy variable demand;

- Efficiency of the storage system and inverters: It is essential to consider the efficiency of batteries and power electronics, along with standby consumption [19,29]. In our approach inverter loses, charging cycle loses, and energy consumed during inverter idle operation are included;

- Component aging and degradation: Investment horizons, typically ranging from 10 to 25 years, necessitate an assessment of degradation. PV panel degradation and battery aging, both cyclical and calendar, significantly influence system economics and sizing. Neglecting these factors leads to an underestimation of long-term costs and an overestimation of PV production [4,19,30,31]. Our model takes into account the degradation of PV panels and the preservation of battery efficiency during the analysis due to the reduced operating range of the energy storage compared to the maximum capacity;

- Energy management strategies (EMS): To attain optimal economic advantages in prosumer systems, it is essential to implement advanced energy management strategies. Effective energy management is crucial in the context of fluctuating tariff structures [8]. The literature indicates that advanced management algorithms provide substantial economic advantages [29]. In our solution, charging the storage has priority, but it allows testing other energy storage operation strategies;

- Long-term optimization of investment scale, integrated with an evaluation of the project’s financial efficiency and a distinctive assumption concerning the cost of capital. Net Present Value (NPV) analysis and optimization of installation size, specifically photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage system (BESS) sizes, were performed from the viewpoint of a private investor without reliance on subsidy mechanisms.

Although the analysis focuses on Poland, the findings may be transferable to markets that share comparable regulatory and technical characteristics. In particular, the results apply to systems operating under net-billing or similar compensation schemes that do not remunerate surplus generation at retail prices; countries with mid-latitude irradiance profiles; household consumption patterns dominated by daytime absence and evening peaks; and distribution grids where operators increasingly promote local balancing and self-consumption. Outside these conditions, especially in markets with FIT remuneration, generous export tariffs, or markedly different load structures, the financial performance of PV-BESS systems may diverge substantially. This clarification delineates the scope within which the present results may be generalized to other European contexts.

The subsequent sections of the article are structured as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology for investment efficiency assessment and the technical–economic modeling framework, including simulation of PV generation, consumption, and storage operation. Section 3 describes the case study assumptions for a 6 kWp PV-BESS with 15 kWh storage, including capital expenditures, degradation, additional operational consumption, and estimated benefits, as well as efficiency indicators such as NPV, IRR, B/C ratio, PBP, and DPBP. Section 4 analyses optimal sizing of PV and storage capacities for a given load profile and investigates sensitivity to capital expenditures, cost of capital, and grid prices, while Section 5 discusses the main findings, limitations and potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

A computer simulation was employed to prepare data for the efficiency assessment, utilizing a series of programs in R. The simulation aimed to replicate a realistic daily and seasonal profile of alternating current (AC) energy production and consumption, utilizing a PV-BESS system, with automatic support from the power grid during instances of energy shortages in the storage system or PV production. Calculations were based on a household consisting of two adults and two school-aged children. Calculations were conducted using a time step of 15 min. The simulation duration extended from 1 August 2025, to 31 July 2035. The initial program facilitated the downloading, verification, cleaning, and correction of source data reflecting actual energy production from panels functioning in real-world conditions over the past six years. The second program modeled family energy consumption, considering factors such as season, day type, typical electrical appliances, and their usage by family members across various days and hours. The third module includes a procedure for simulating the operation of the energy storage system, considering production and required consumption in 15 min intervals (96 slots per day).

Although the general structure of the simulation follows widely used PV-BESS analytical frameworks, several components of the modeling approach applied here extend standard practice. Specifically, the model integrates stochastic year-to-year PV generation drawn from empirical high-resolution datasets, device-level stochastic household demand, and a recursive state-of-charge algorithm that captures PV aging, battery cycle and conversion losses, and inverter consumption. These elements are combined within a unified 15 min operational horizon, calibrated to net-billing constraints that prohibit surplus-energy exports. This combination of stochastic production, stochastic consumption, detailed loss modeling, and private-investor financial evaluation has not been jointly implemented in previous analyses. The framework therefore contributes an original methodological extension by enabling a more realistic representation of household-scale PV-BESS operation under Polish net-billing conditions.

2.1. Evaluation of Investment Efficiency

This article focuses on Net Present Value (NPV) as the primary metric for evaluating investment efficiency. NPV is a widely recognized measure in corporate finance [32,33,34] and is well-supported by financial theory in academic literature [35,36,37]. This measure relies on the fundamental principle of deducting investment costs from the total benefits accrued. The outcome is a net value that signifies the aggregate of net benefits. The Net Present Value (NPV) is defined by the Formula (1).

- NPV—net present value of the investment project;

- CFt—cash flow in the period t = 0, 1, 2, …, n;

- r—cost of capital for the project (%);

- t—time index of the cash flow t = 0, 1, 2, …, n;

- n—time index of the last year of the project.

The difficulty in NPV calculations is estimating the cost of capital, which is related to a specific level of market risk in a given business activity and facilitates the comparison of benefits spread over time. When market risk impacts an individual and the definition of their business risk is ambiguous, it is appropriate to define the cost of capital as the rate of return on an alternative investment available to the investor [38]. While it is feasible for an individual to engage in active investment and attain substantial returns, such occurrences are infrequent. Individuals tend to prefer investing in straightforward instruments, such as bank deposits, or may choose not to invest their surplus funds altogether. The National Bank of Poland [39] reports that over 50% of Polish savings are maintained in cash and bank deposits, which yield low returns. This figure is the highest among major EU economies and considerably exceeds the EU average of 31%. Individuals, when considering inflation, realize a negative return on their capital. Considering the widespread nature of this behavior, it is reasonable to conclude that the opportunity cost of capital for an individual investing in a PV-BESS system corresponds to the inflation rate. This rate is also close to the typical level of deposits in Polish banks available without fulfilling various promotional conditions necessary for higher interest rates. At the investment start date (1 August 2025), the inflation rate was 3.1%, which was incorporated into the NPV calculations and other discounting methods employed. A complementary sensitivity analysis for alternative discount rates is presented in the Section 4, where the implications of higher opportunity-cost assumptions for investment viability are quantified.

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is another frequently utilized metric [32,33,34]. This measure indicates the overall return on investment, which must exceed the assumed cost of capital. The third measure employed in the calculations, which is infrequently utilized yet facilitates the estimation of benefits per monetary unit invested, is the Benefit Cost Ratio (B/C) [35,37]. The Payback Period (PBP) and Discounted Payback Period (DPBP) metrics were also calculated. The corporate finance literature critiques these measures [35,37], yet they possess a distinct and noteworthy interpretation in the examined example. The payback period indicates the duration required for the PV-BESS system to function without major failures necessitating replacement to recover the investment costs. DPBP incorporates the investor’s cost of capital, resulting in its extension compared to PBP.

Although the Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) metric is widely utilized in energy efficiency assessments, it was not applied in our example. The LCOE metric exhibits methodological requirements, notably the exclusion of production profile, usage flexibility, and grid integration costs [40,41]. Incorporating these parameters into the calculation presents challenges, as it necessitates several additional assumptions. LCOE is not appropriate for household PV-BESS under net-billing because the system is not generation-maximizing; therefore NPV and IRR are used as primary metrics.

Time is a crucial element in analyzed investment. While the investment may require a longer duration, we have assumed a 10-year operational period, which is a reasonable timeframe for a private investment of this magnitude. The useful life of the panels can extend to 20 years or more, a detail that certain companies explicitly state in their PV panel warranties. However, the technical durability of inverters and energy storage electronics may raise concerns. Minor assembly errors, such as inadequately tightened power connectors, along with substandard components, particularly capacitors and power transistors, may lead to failures occurring prior to the anticipated ten-year lifespan. This also pertains to the durability of energy storage batteries and the electronics that control their operation. It is assumed, potentially with some optimism, that the equipment will last for the intended ten-year lifespan. To accommodate an extended operational lifespan, it is necessary to revise this assumption and incorporate further considerations regarding the likelihood and costs associated with equipment failure.

Key inputs and assumptions underlying the simulation are summarized below. The model integrates: (i) empirical 15 min PV generation data corrected for degradation, (ii) a stochastic household electricity-demand model based on device-level power profiles and usage probabilities, (iii) fixed technical parameters of the PV-BESS system, including a 15 kWh LiFePO4 battery, 10–90% allowable state of charge, inverter idle consumption and conversion losses, and (iv) economic parameters such as the 3.1% cost of capital, zero scheduled maintenance, component prices, and electricity tariffs applicable as of August 2025. These inputs and assumptions are implemented consistently across all stages of the simulation and form the basis for the efficiency evaluation presented in Section 3.

2.2. Simulation of Electricity Production in the Analyzed Model

To accurately predict long-term economic efficiency, it is essential to include uncertainty modeling, such as sampling production years from a historical dataset [42]. The PV panels production simulation utilizes empirical data derived from the measured output of the photovoltaic systems installed on a south-facing roof with a 35-degree slope in a suburban area of Szczecin (latitude 53°43′ N). All available data in our dataset comprises 4983 locations across Poland and Central Europe, enabling an evaluation of the efficiency and optimization of installations in areas with diverse microclimate characteristics, including variations in sunlight, cloud cover, and temperature. We selected one location in the city in which the planned installation is located. The input data for the chosen location spans from 20 April 2019 to 16 July 2025. However, for the simulation of future production, only complete years of production are utilized. A full year of PV production is randomly selected from the available input data for each planned year of analysis (refer to Figure 1).

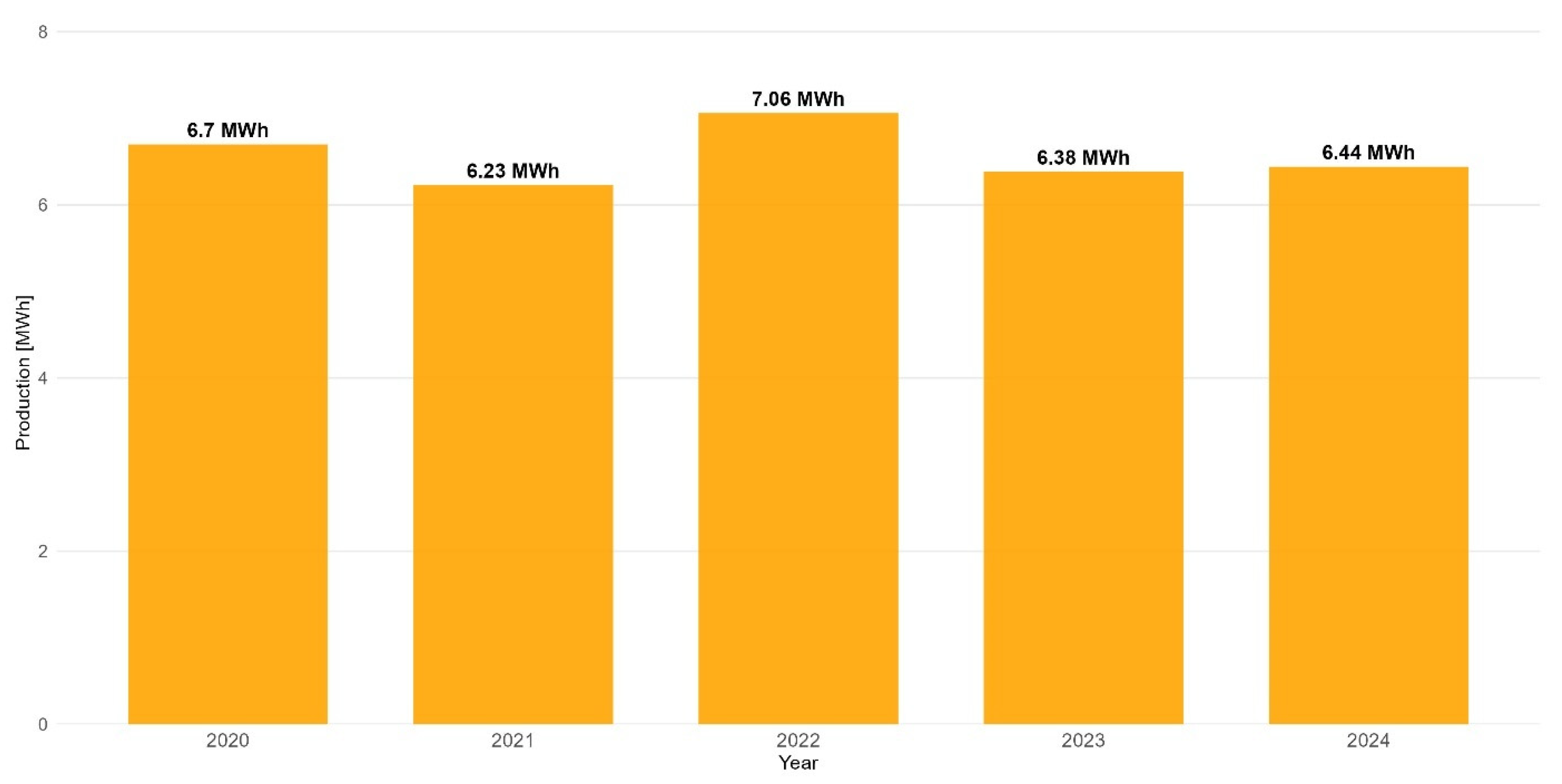

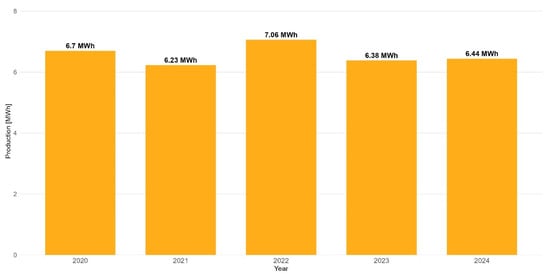

Figure 1.

Empirical annual PV production corrected for degradation at the selected location (2020–2024).

The data were verified, cleaned and extended before use. Data were collected at irregular intervals, with a median duration of 5 min. The start and end of each slot was different every day. The data were converted into 15 min intervals, with proportional adjustments applied at the beginning and end of each interval based on the start or end time of the original data segment. During the six-year period, several missing values were substituted with data from the preceding day or with the average production from the two or three days prior to the missing data, with a maximum of three consecutive days of missing data. A month-long interval of missing measurements was addressed by utilizing average production data from the corresponding calendar day in the other years.

Following the conversion to 15 min intervals, the data were revised upward to remove the effect of manufacturer-reported degradation in historical data, restoring them to their original performance levels for modeling purposes. A proportional change in PV panel production throughout the year was assumed, with each production in a specific day’s slot adjusted for the cumulative daily degradation value. This led to historical data that remained unaffected by the degradation of the photovoltaic panels. Figure 2 presents data on historical monthly average production, adjusted in plus for degradation. A reverse adjustment was conducted to model PV panels performance in simulation over the intended 10-year period, decreasing the annual PV production by the cumulative degradation for each subsequent day. The historical data was collected for LONGI 310W panels (LONGi Green Energy Technology, Xi’an, China), which have a manufacturer-declared annual degradation rate of 1.9% in the first year and 0.55% in subsequent years. The installation will utilize Jinko Solar 435 panels (JinkoSolar Holding, Shanghai, China), which have a manufacturer-declared degradation rate of 1.0% in the first year and 0.4% in the following years.

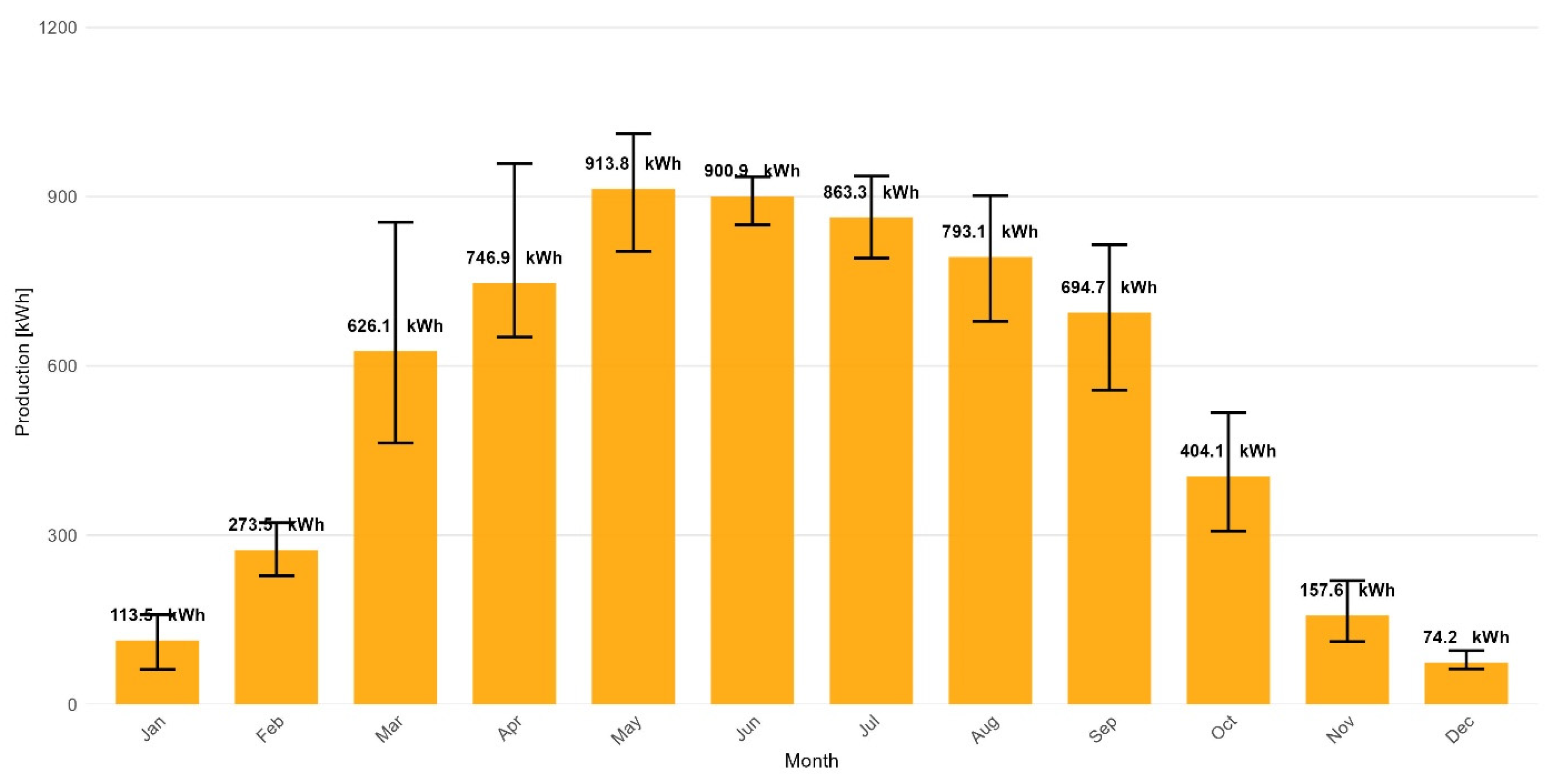

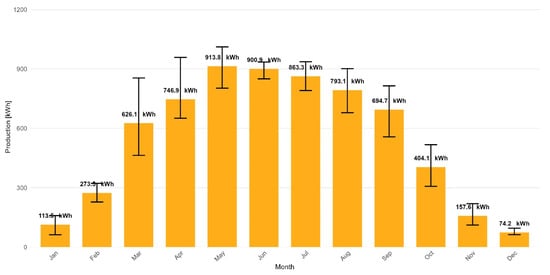

Figure 2.

Average monthly PV production with min/max range corrected for degradation at the selected location (2020–2024). Source: empirical PV production data corrected for degradation.

2.3. Simulation of Household Electricity Consumption

A simulation lasting 15 min was created to model electricity consumption in a household with two adults and two children, utilizing established device profiles, day types, and household schedules. The simulation spans from 1 August 2025 to 31 July 2035 providing consumption data in kWh for each time slot, categorized by device type for control purposes. Initialization encompasses several elements, including household composition (two adults, two children), definitions of day types (weekday, weekend, holiday, vacation at home, and away from home), and a comprehensive set of 13 device profiles detailing rated power, activity windows, daily start probabilities, and cycle times. Table 1 presents the list of devices. The assigned power for a washing machine is 2.0 kW, for a kitchen induction hob is 2.5 kW, and for a TV is 0.150 kW. Operating windows are differentiated based on the type of day and the defined probabilities of session or daily cycle occurrences.

Table 1.

Overview of equipment and selected performance parameters used in the electricity consumption simulation.

The sustained power of devices is utilized to compute the energy within a slot. Device activity windows are established within specific time frames based on the type of day, such as varying for a washing machine on weekdays compared to weekends. Additionally, for specific devices, the likelihood of usage on a particular day (e.g., laundry, computer, gaming console) is assessed, differing across various types of days. Each device is allocated a specific cycle duration or a variable operating time within designated activity windows (e.g., a 60 min cycle for a washing machine, a 90 min average session for a gaming console on weekdays with a standard deviation of 20 min, differing means and standard deviations for other types of days).

The day type for each slot is established according to the holiday calendar and the designated “at home” and “away from home” holiday ranges, verified through an auxiliary function. The classification employs the subsequent priorities: holiday, vacation away from home, vacation at home during weekdays, vacation at home during weekends, weekdays, and weekends. The outcome consists of time-based data categorized by day type, which is then utilized to randomize daily parameters and regulate device activity. Data are categorized by date and day type, with session or work cycle parameters randomized for each day, thereby introducing daily variability (e.g., laundry does not occur daily, and meal times vary). The television’s viewing time follows a normal distribution constrained by a specific window and a random initiation within that window. The washing machine operates based on daily probabilities and a random start. Meal preparation times are derived from a normal distribution centered around the means, with deterministic cooking time added. Boiling water occurs few times daily randomly at different times within designated daily activity windows, with the start time determined within the allowed minutes of the day. The gas furnace consumes electricity, with energy usage varying by season (winter, transition, summer) and occupancy modifiers, such as increased consumption during winter weekends. Devices including computers, printers, gaming consoles, and hobby devices operate in sessions that are probabilistically determined. The durations of these sessions follow a normal distribution, while the start times are randomly assigned within the constraints of the designated work window for the day. The printer accommodates both printing and standby phases. Lighting is contingent upon the type of day and is modified according to sunrise and sunset, as reflected in monthly profiles.

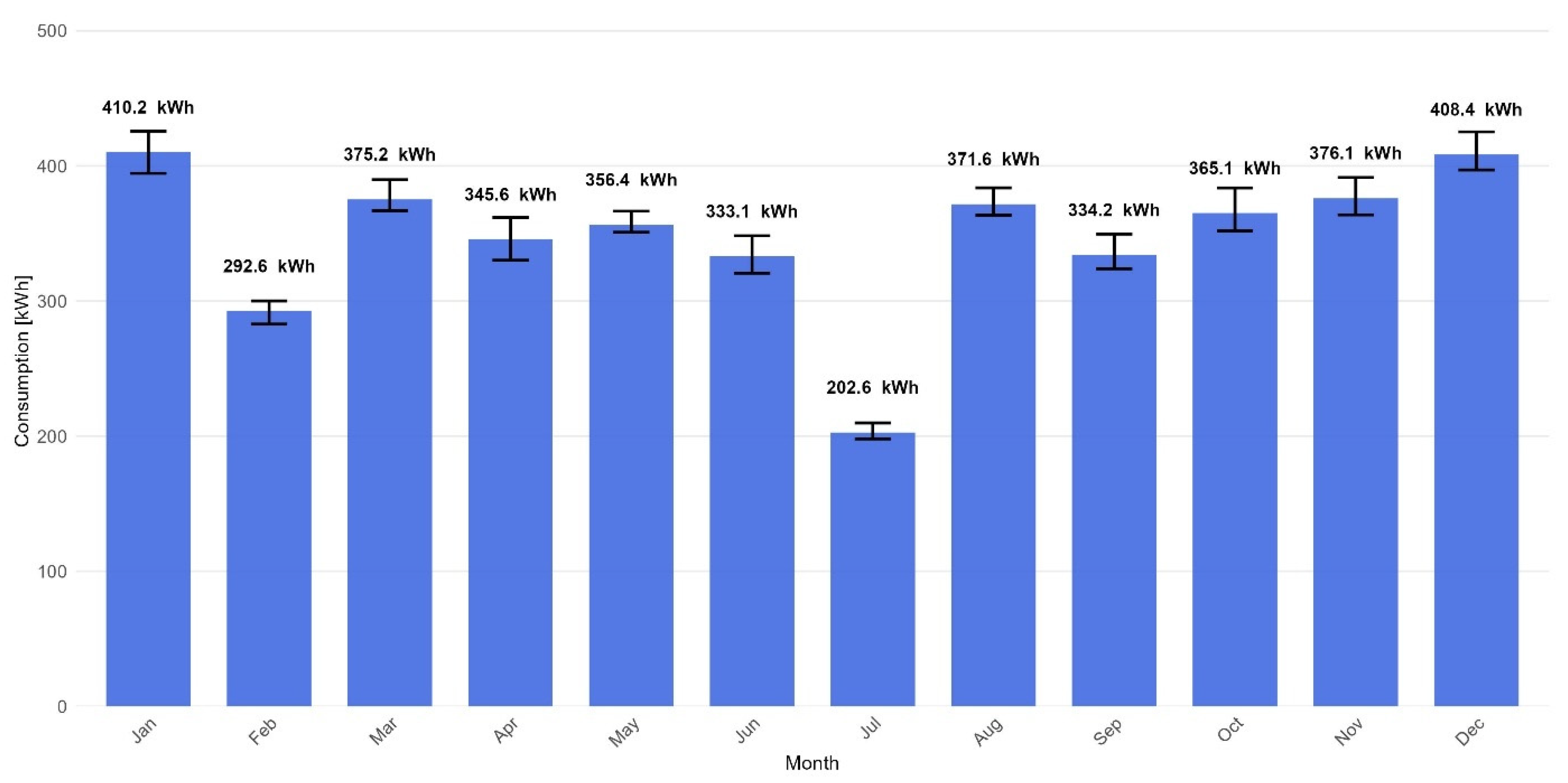

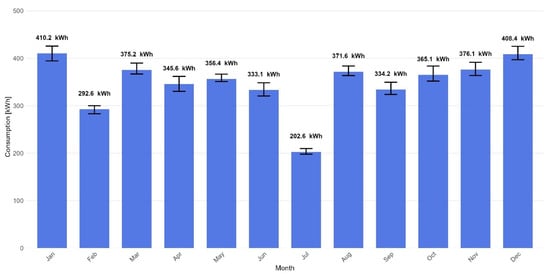

Figure 3 illustrates the total monthly consumption and its deviations. The overall AC consumption within a slot is calculated by aggregating the components from all device categories. It is worth noting the reduced consumption in February and July, when holiday trips are planned. The output frame includes time metadata (slot start/end, date), day type, slot length, and a detailed breakdown of consumption by device, in addition to the total consumption value.

Figure 3.

Average monthly AC consumption with min/max range (2025–2035). Source: simulation results.

The average energy consumption recorded in our simulation is 4357 kWh annually. Statistics Poland (Central Statistical Office, GUS) reported that energy consumption in the average Polish household in 2021 was 2523 kWh [43], with an average household size of 2.55 individuals [44]. The average electricity consumption per capita is 989.4 kWh, resulting in a total of 3958 kWh for a family of four. This shows a slight divergence from our findings. It is important to highlight that the simulation employed an electric cooker, which is utilized in approximately 20% of households in Poland. Thus, we can approximate that the simulation represents an average four-person family residing in a house heated by a non-electric source.

2.4. Simulation of PV and BESS System Operation

The simulation procedure for the integrated photovoltaic system and energy storage system is performed at fifteen-minute intervals. This process balances DC flows on the photovoltaic side, accounts for conversion losses, and meets AC demand to accurately reflect self-consumption patterns, storage charging and discharging, and grid interaction throughout the entire time horizon of the input data. The input data comprises actual photovoltaic (PV) production time series, which have undergone a singular scale correction based on the presumed size of the PV installation, ranging from 7 to 14 panels, each with a capacity of 430 Wp. The initial normalization of photovoltaic (PV) production through a specified scale factor facilitates the projection of system performance for a particular installed capacity, while preserving the relative daily and seasonal patterns observed historically. The second input element in the PV-BESS system simulation is the energy consumption pattern of the building, which is considered as exogenous demand in each time slot. The simulation serves to enforce technical constraints and prioritize energy flows among photovoltaic systems, storage, loads, and the grid. Initially, a consistent time frame is established by aligning photovoltaic (PV) production years with consumption years, utilizing a singular reference year derived from a complete set of years. This resolves calendar discrepancies and guarantees comprehensive coverage of 15 min intervals. Each year of the planned PV-BESS system operation is paired with a corresponding year from historical production data. The sequence of years is recorded and utilized in subsequent simulations of system operation, varying the sizes of the PV panels and storage arrays. This guarantees comparability among the variants produced by the sensitivity analysis. The combined production years are subsequently adjusted for the photovoltaic panel degradation factor as outlined in the preceding procedure. Following the standardization of the time horizon, the production and consumption sets are integrated based on the day and time key, maintaining quarter-hour precision. This ensures that each time slot contains a complete pair of input quantities: PV energy on the DC side and load on the AC side. Table 2 presents the sequence of the drawn years.

Table 2.

Randomly drawn order of historical electric production years for PV production used in all system simulations.

The energy control model operates sequentially, prioritizing the utilization of local photovoltaic (PV) systems and storage over grid consumption, thereby consistently applying the energy import minimization heuristic. The system initially directs photovoltaic (PV) energy to charge the storage in each slot, constrained by the available PV power, the permissible charging energy limit per interval, and the remaining battery capacity adjusted for cycle efficiency. Materialized charging losses are documented as a distinct output item. Subsequently, the residual photovoltaic energy is transformed into alternating current to meet the inverter’s continuous idle consumption, followed by addressing the current household load. DC-to-AC conversion losses are documented as the total inverter losses within a specified interval.

In the event that unmet demand persists following PV utilization and the state of charge surpasses the minimum allowable load, the third step involves the allocation of energy from storage. This process adheres to the established supply sequence: prioritizing inverter idling, followed by load demand, thereby minimizing loss arbitrage and averting unnecessary partial discharge cycles. This step involves the explicit accumulation of DC to AC losses, while simultaneously updating the state of charge to reflect the energy exported from the AC side and the associated conversion losses. The fourth step aligns the remaining demand with grid imports, thereby closing the slot balance and ensuring that the total of flows and losses matches the unmet demand and the operation of the inverter.

To minimize initial state of the system influence on operation, the system simulation starts with the charge state set to the minimum allowable, and then the final state of each slot is carried forward as the initial state for the next slot throughout the time series. This recursive update of the storage state effectively determines process memory and facilitates the mapping of the impacts of sequencing solar and load events on energy availability in the following hours and days. The algorithm preserves energy integrity by precisely accounting for storage and conversion losses, facilitating reliable aggregation at daily, monthly, and annual intervals while maintaining balance accuracy.

The resulting data comprises synchronized production and demand inputs for verification, along with variables that describe energy flows and resource status in each interval. This enables direct assessment of storage utilization, self-consumption, and grid dependency indicators. The components included are: energy transferred from photovoltaic (PV) systems to storage for charging, energy delivered directly from PV to AC loads, energy transferred from storage to loads, energy drawn from the grid, inverter losses, charging cycle losses, energy consumed during inverter idle operation, and the final state of charge measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh). The output variables are defined at the slot level, facilitating subsequent filtering and recombination according to analytical and scenario requirements. Dividing flows into direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) components, along with distinct loss accounting, facilitates clear comparisons of efficiency variations and evaluation of sensitivity to conversion parameters.

The peak instantaneous power recorded in a slot was an 8.53 kW draw over the entire projected 10-year period, succeeded by four draws ranging from 8.30 to 7.60 kW. All other slots exhibited draws below 7 kW, with 91.6% of the 15 min slots demonstrating draws under 5.5 kW, which is less than 50% of the maximum inverter load.

The simulation utilized several key parameters to define the state and flow trajectory, including: storage capacity in kWh (tested at 5, 10, and 15 kWh), minimum and maximum allowable state of charge as fractions of capacity (ranging from 10% to 90% of storage capacity), storage cycle efficiency, DC/AC inverter efficiency, constant inverter idle power consumption, calculation interval length, maximum allowable charging energy based on current and voltage constraints, PV production scaling factor (number of PV panels ranging from 7 to 14), an algorithm for aligning reference years of production with years of consumption, and the initialization condition of the storage state. The integration of a deterministic feed-in sequence with precise loss accounting establishes a replicable and physically consistent model of PV-BESS system operation at a fifteen-minute resolution. This model is prepared for the analysis of self-consumption efficiency, grid energy reduction, and inverter load across diverse input conditions. This establishes an objective framework for comparing system configurations, evaluating the effects of alterations in technical parameters and input data quality, and developing operational metrics for optimization and investment planning.

The physical and economic validity of the model is supported by the close alignment of simulated outcomes with empirical benchmarks. Simulated annual household electricity demand (4357 kWh) closely matches Statistics Poland data for a four-person household (3958 kWh), with the remaining difference explained by the inclusion of an electric cooker used in approximately 20% of Polish households. Likewise, simulated PV production profiles are based directly on measured high-resolution generation data from the analyzed location (2020–2024), ensuring realistic seasonal and daily variability. The model also reproduces typical peak household loads (up to 8.5 kW), consistent with values reported in Polish and European residential studies. These correspondences confirm that the simulated energy balance—both on the generation and consumption side—is representative of real household conditions and provides a valid basis for the subsequent economic evaluation.

3. Results

The efficiency calculations presented in this article derive from data acquired through simulations of electricity production from PV panels, residential electricity consumption, and storage operations. The foundation for efficiency calculations is aligned with the investment efficiency assessment methodology, focusing on cash flows. In this context, cash flows encompass the capital expenditures related to the construction of the PV-BESS system and the savings in electricity consumption from the grid, which serve as a positive benefit of the system installation. The energy balance in the simulation of energy production and consumption incorporated the operating costs of the system, which encompassed inverter power consumption, inverter losses, and storage losses. This section focuses exclusively on numerical results derived from the simulation and the resulting economic indicators.

3.1. Capital Expenditures and Advantages of Implementing a PV-BESS System

Two fundamental categories of variables required for analyzing the efficiency of a private investment in a PV-BESS system are capital expenditures and the benefits derived from its utilization. Capital expenditures encompass the acquisition of system components, their installation, and subsequent inspection by a licensed electrician. The assumption was that this constituted a ground-based installation, permitting the user to self-install the equipment prior to inspection by an electrician. This substantially lowers installation costs and, as the analysis indicates, is essential for attaining economic efficiency. Labor costs for the installation are estimated to range from EUR 1752 to EUR 3971 (all estimations and calculations made in PLN; the PLN-to-EUR conversions are based on the average NBP (National Bank of Poland) exchange rate of 4.2813 PLN/EUR as of 1 August 2025). The costs are contingent upon specific site conditions that affect the complexity of the work involved. These tasks, being straightforward in nature—ground, mechanical, and electrical works—are suitable for execution by a private investor. System safety must be guaranteed through inspection by a licensed electrician prior to commissioning. A mid-life technical inspection of the system was assumed to occur after the fifth year. The installation inspection costs have risen due to inflation relative to the costs at the time of installation. Table 3 summarizes the total investment costs.

Table 3.

Investment outlay planned in the PV-BESS project.

The primary and most expensive components of the system are the energy storage system, photovoltaic panels, and an inverter that functions as an MPPT controller, powers the energy storage system, and converts direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC). All system components are accessible in the Polish market. These components are generally manufactured in China, yet they can be shipped from European countries and come with a warranty. This guarantees the inclusion of relevant customs duties and VAT in the pricing of all components.

The second crucial element of the analysis pertains to the savings derived from procuring electricity from the grid. The savings were assumed to encompass all variable charges associated with electricity at the commencement of installation (1 August 2025). The standard price lists from Enea, which supplies electricity in the Szczecin region, were utilized as of the end of July 2025. At the time of project launch, the cost of 1 kWh of electricity, inclusive of transmission, was EUR 0.2267 (PLN 0.9707). Savings arise from decreased electricity consumption from the grid due to the implementation of the PV-BESS system. The original consumption is determined by the total electricity demand of the home. The reduced grid consumption from the PV-BESS system accounts for the energy balance, including the additional consumption from the inverter and energy storage. This additional demand, particularly during winter months, is met by the grid due to inadequate sunlight. The financial evaluation also relies on several simplifying assumptions regarding system operation. The model does not incorporate maintenance or repair costs, which constitutes a limitation, as real-world operation may involve occasional inverter servicing, battery management tasks or component replacement that could reduce long-term financial performance. This implies that the reported NPV and IRR represent upper-bound estimates achieved under idealized durability conditions, and any deviation from perfect component reliability would shift these results downward.

The total cash flow utilized for efficiency calculations is represented by Formula (2).

CFt—cash flow in the period t = 0, 1, 2, …, n;

CAPEXt—capital expenditures (total investment costs, usually in t = 0);

CONSt—electricity consumption in t = 1, 2, …, n;

eGRIDt—electricity consumption from the grid with the PV-BESS system operational in period t = 1, 2, …, n;

CHCKt—costs of checking the installation (planned in period 5).

The NPV, IRR, B/C ratio, PBP, and DPBP are calculated on the base of presented cash flow. Comprehensive discussions of NPV and other efficiency indicators are available in academic literature on financial management [35,36,37]. Additionally, we compute the total net benefits without applying a discounting, which reflects the net present value at a zero cost of capital.

3.2. Assessment of the Efficiency of a PV-BESS System

To prevent the optimal commissioning of the PV-BESS system immediately prior to the peak solar radiation season, we assumed that the private investor postpones start up to a suboptimal time, with the activation scheduled for 1 August 2025. This indicates that during a ten-year analysis period, we apply a discounting for eleven periods. In the initial period, a power of 0.4192 is utilized for discounting, corresponding to the remaining days in the first year of operation, followed by 1.4192 for the subsequent full year, and so forth. A power of 9.4192 is utilized for the penultimate period, while a power of 10 is applied for the final eleventh period lasting 7 months. The remaining discounted measures are adjusted in a similar manner. This aligns with the principles of financial mathematics regarding unequal discounting periods.

The initial design involved a PV-BESS system comprising 14 PV panels, each rated at 430 Wp, resulting in a total capacity of 6.0 kWp, installed on the ground, alongside a 15 kWh storage system utilizing a 48V LiFePO4 battery configuration. This solution was selected under the premise of adequate safety and simplicity for home installation, while also meeting assumed system size and efficiency criteria. Table 4 presents the cash flow model for this solution.

Table 4.

Efficiency evaluation model for a PV-BESS system with 6 kWp in PV panels and 15 kWh in energy storage.

The efficiency results indicate NPV of EUR 599. This signifies that after a decade of projected system operation, the investor will realize a net monetary benefit equivalent to this amount, factoring in the investor’s cost of capital. The analysis of the capital expenditure, represented by the B/C ratio, indicates that the investor will achieve a return of EUR 1.124 for each EUR 1 invested in the project. The project’s internal rate of return (IRR) is 5.32%, exceeding the cost of capital at 3.1%. The indicators reflect the profitability of this investment project; however, the financial surplus is limited, and any misstep during implementation—such as a failure or adverse change in electricity prices—can significantly jeopardize its profitability. The payback period (PBP) and discounted payback period (DPBP) are 8.0 and 9.0 years, respectively, serving as reliable indicators of the project’s technical requirements. This indicates that a duration of nine years is required to achieve the critical point at which the investment benefits completely offset the capital expenditure. This implies that equipment failures must be avoided during this period, as unforeseen repair costs, which are not factored into the calculations, will undermine the marginal efficiency achieved. The fulfillment of this requirement for the equipment in question remains uncertain and poses a considerable risk to the project.

Analysis of the results indicates that extending the system’s operation by one additional full year will yield an increase in the net discounted benefit of approximately EUR 584. Conversely, an electrician’s inspection of the system should be scheduled every five years, including after year 10, resulting in a reduced surplus of EUR 93 after applying discounting over the years of system inspection. Considering these relationships, the net present value (NPV) of the fifteen-year project is EUR 2706, while the NPV of the twenty-year project is EUR 5182. This calculation fails to consider the potential for electronic equipment failure or the need for battery replacement. The lifespan of a LiFePO4 battery, when operated at an 80% charge/discharge cycle, ranges from 5000 to 6000 cycles. Consequently, the entire battery pack would require replacement at least once within a 20-year timeframe, resulting in an estimated cost increase of approximately EUR 981 in current currency values.

3.3. Outcomes of the PV-BESS System Simulation

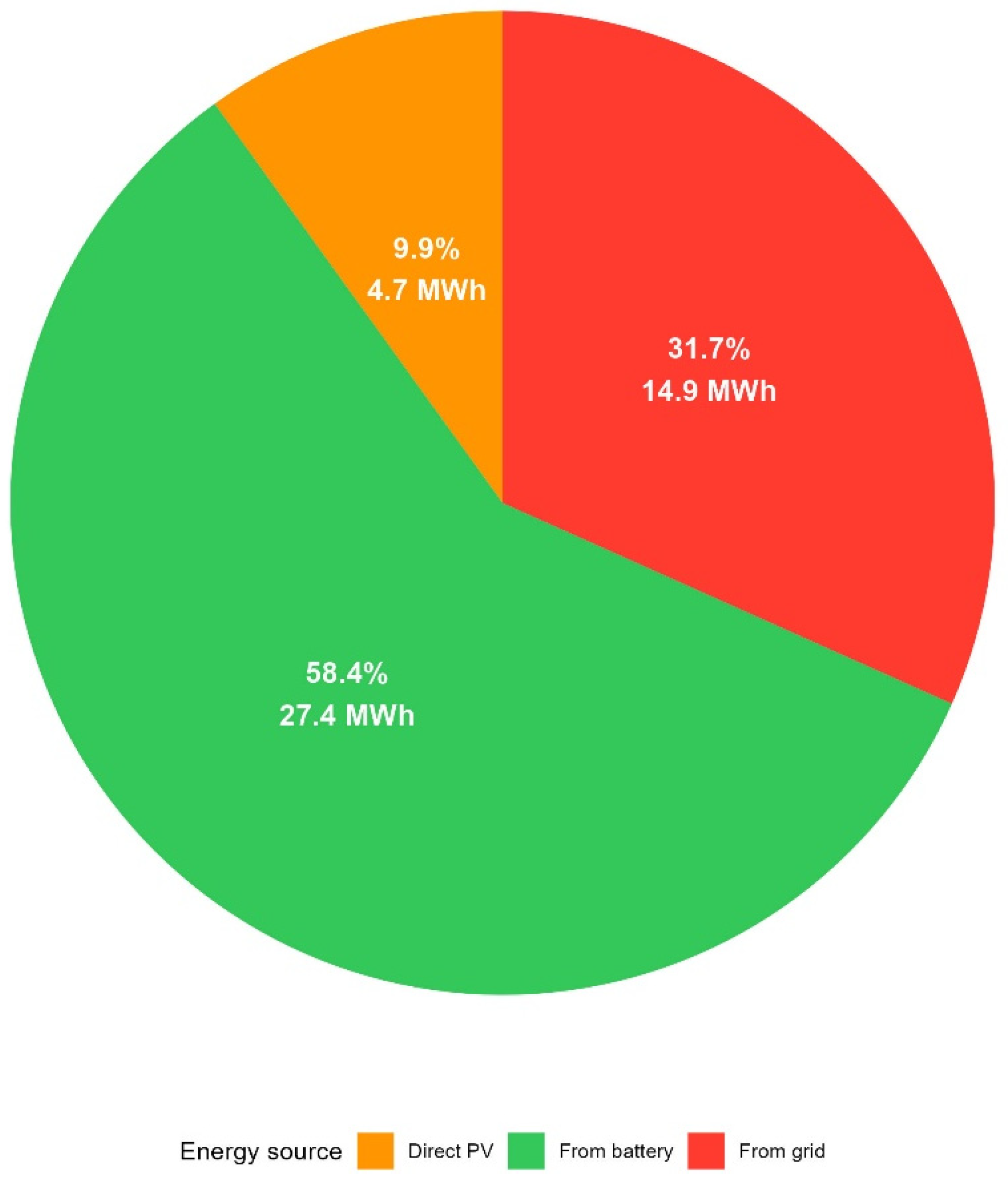

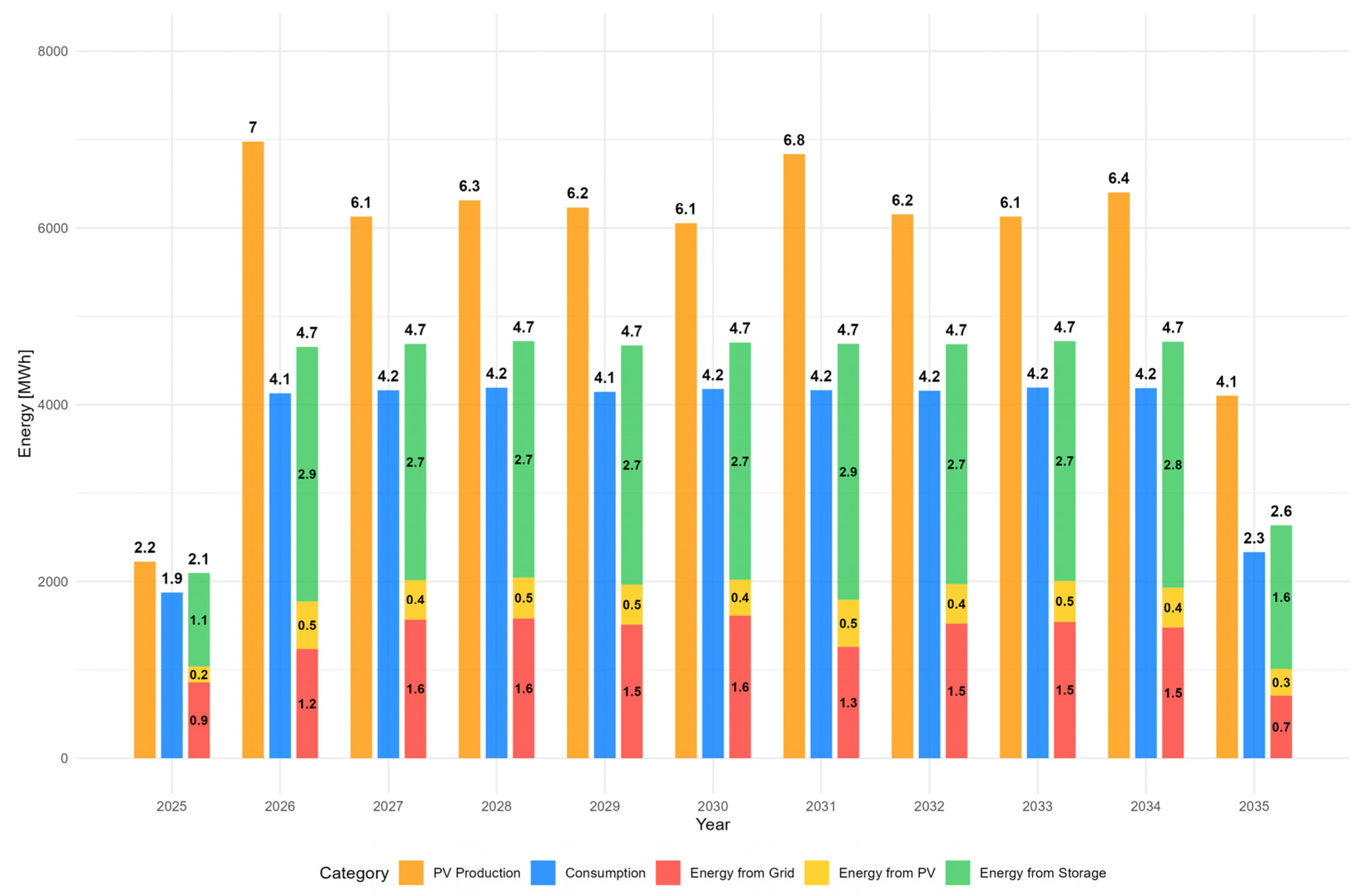

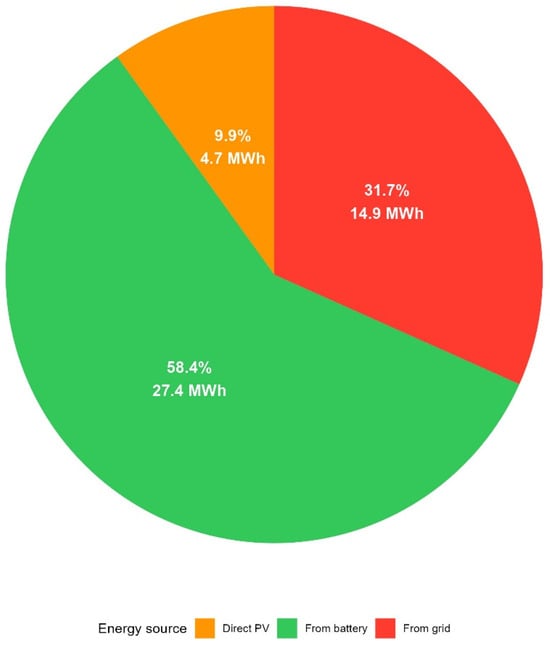

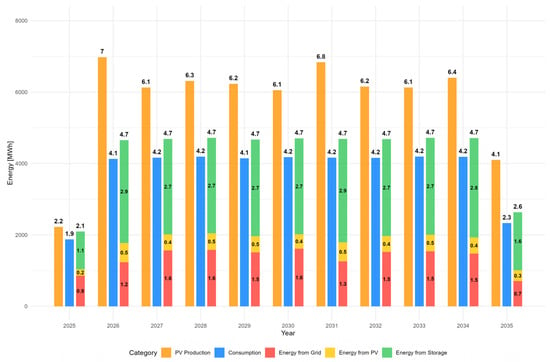

As shown in Figure 4, the system achieves a 64.3% reduction in grid imports, primarily because storage enables a substantial shift in daytime PV generation into evening peak consumption. This pattern confirms that self-consumption, not gross PV yield, is the main determinant of economic performance under net-billing. The figure also indicates that inverter and storage losses constitute the majority of residual grid dependency, which limits further efficiency gains even when PV capacity is increased.

Figure 4.

Structure of energy demand coverage over the planned 10 years of PV-BESS system operation. Source: simulation results (2025–2035). Note: total consumption of 47.0 MWh includes house demand 41.7 MWh plus inverter consumption 5.3 MWh (consumption increase by 12.6%).

The inverter is configured to prioritize the charging of the storage system, with direct energy draw from the photovoltaic panels occurring only from surplus energy stored. During winter and transitional periods, when sunlight is insufficient, the storage is recharged from the power grid to maintain a minimum charge level of 10% of its capacity. Figure 5 demonstrates that annual PV surpluses consistently exceed the absorptive capability of storage and on-site demand, leaving roughly half of generated energy unused. This confirms that storage capacity, not PV potential, is the binding constraint on system utilization under net-billing. The figure also shows that increasing PV size without parallel changes in seasonal demand or regulatory conditions would not materially improve economic outcomes.

Figure 5.

Annual energy balance (MWh). Source: simulation results (2025–2035).

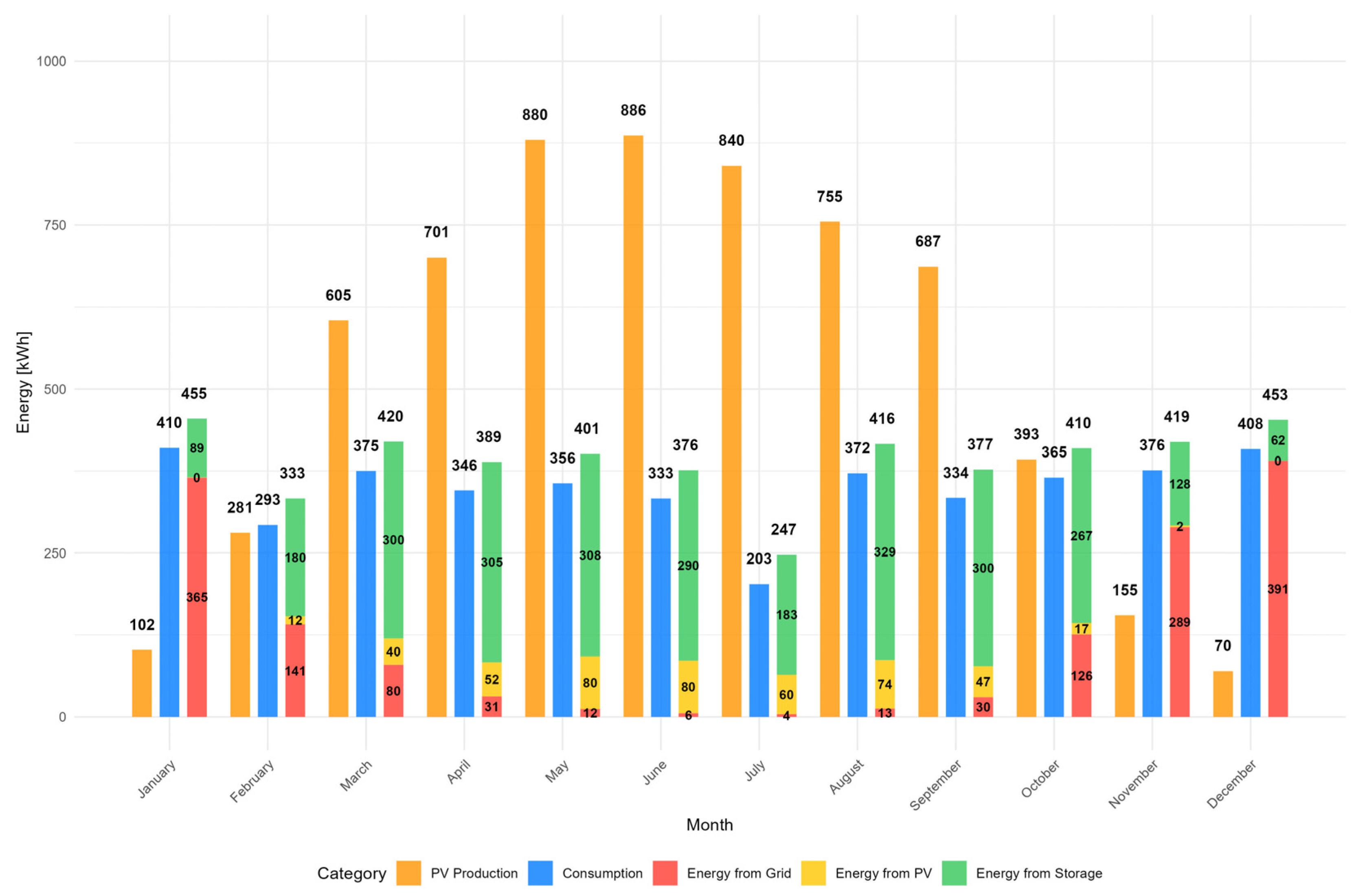

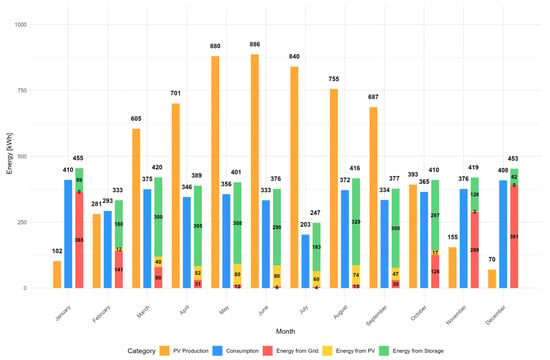

During the 10–year period, the total excess energy for the analyzed PV-BESS configuration is 31.4 MWh, which is nearly equivalent to the energy consumed by the PV-BESS system, recorded at 32.1 MWh. This represents a significant challenge in optimizing the system’s efficiency, as approximately 50% of the production remains unused. One potential solution is to enhance energy storage capacity; however, this would subsequently lead to an increase in capital expenditures. Analysis indicates that even an expanded storage facility would not enhance consumption during the summer months, as the current configuration relies almost entirely on the PV-BESS system for nearly 100% of its consumption. In winter months, even a storage facility twice the size will not suffice for energy needs, as diminished solar radiation inhibits charging capabilities. Figure 6 illustrates this point.

Figure 6.

Monthly energy balance with sources and consumption (kWh, average values for all years). Source: simulation results (2025–2035).

Energy production surpluses, as illustrated in Figure 6 (the difference between PV generation and total energy supplied from PV, storage and grid), are observed from March to September. This seasonal asymmetry drives the system’s marginal profitability, as utilization is concentrated in spring–summer while winter operation relies almost entirely on grid imports. In months with low irradiance (November–January), PV-BESS contribution is minimal, with December showing the strongest dependence on the grid.

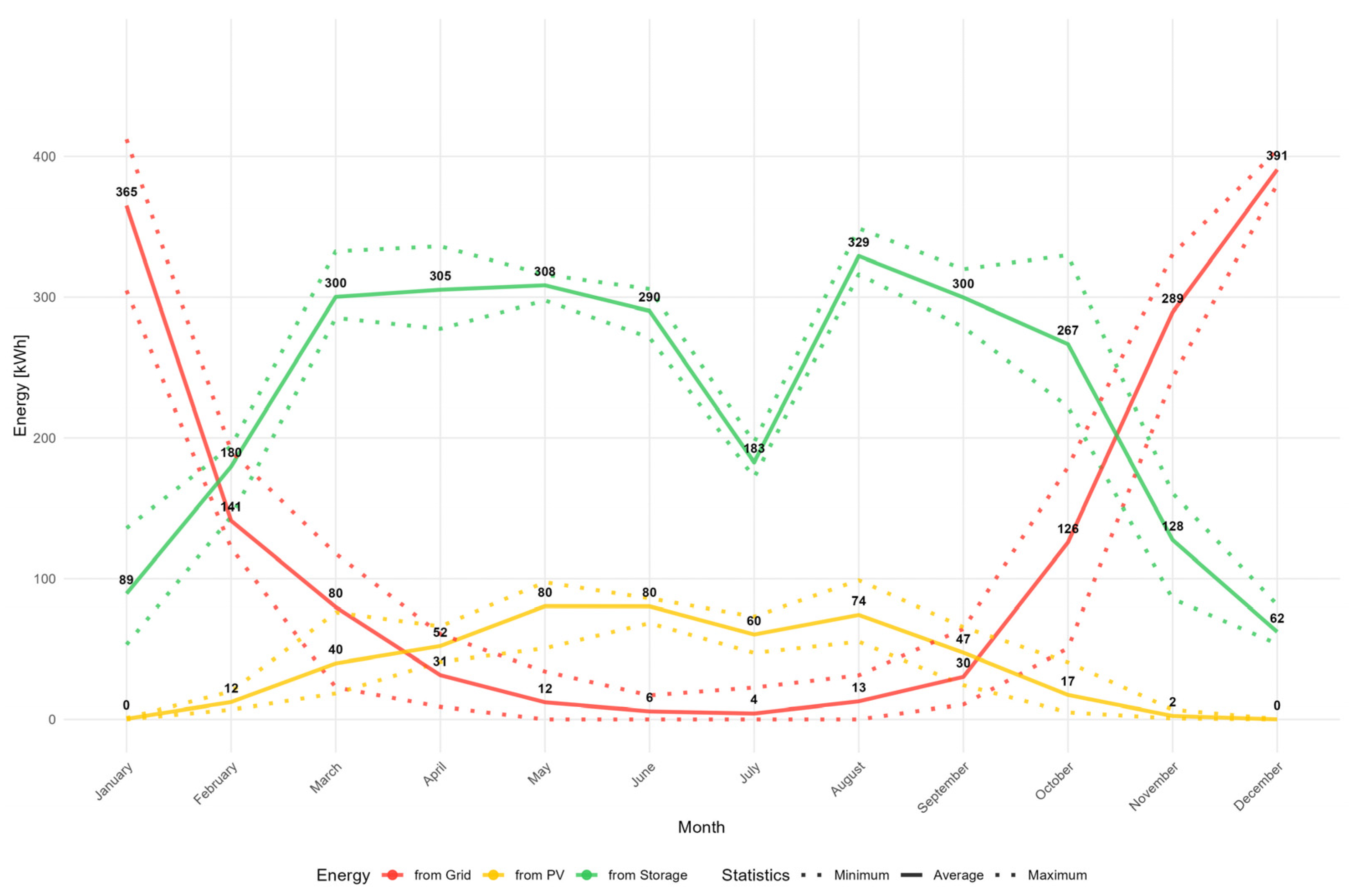

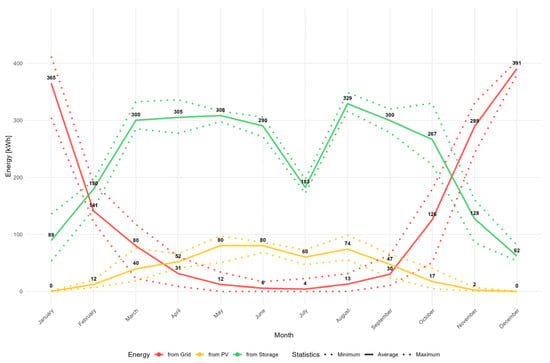

These results indicate that the economic viability of the analyzed PV-BESS configuration remains marginal under current Polish electricity prices, but improves significantly when the operational horizon is extended beyond ten years or when electricity prices increase. This reflects the strong sensitivity of residential storage profitability to long-term market conditions and modeling assumptions regarding system lifetime. Figure 7 shows that storage supports load coverage mainly in late spring and summer, while its contribution in winter remains negligible due to insufficient PV input. This confirms that annual efficiency is governed by a narrow seasonal window when PV supply and household demand align.

Figure 7.

PV-BESS system energy sources by month (kWh). Source: simulation results (2025–2035).

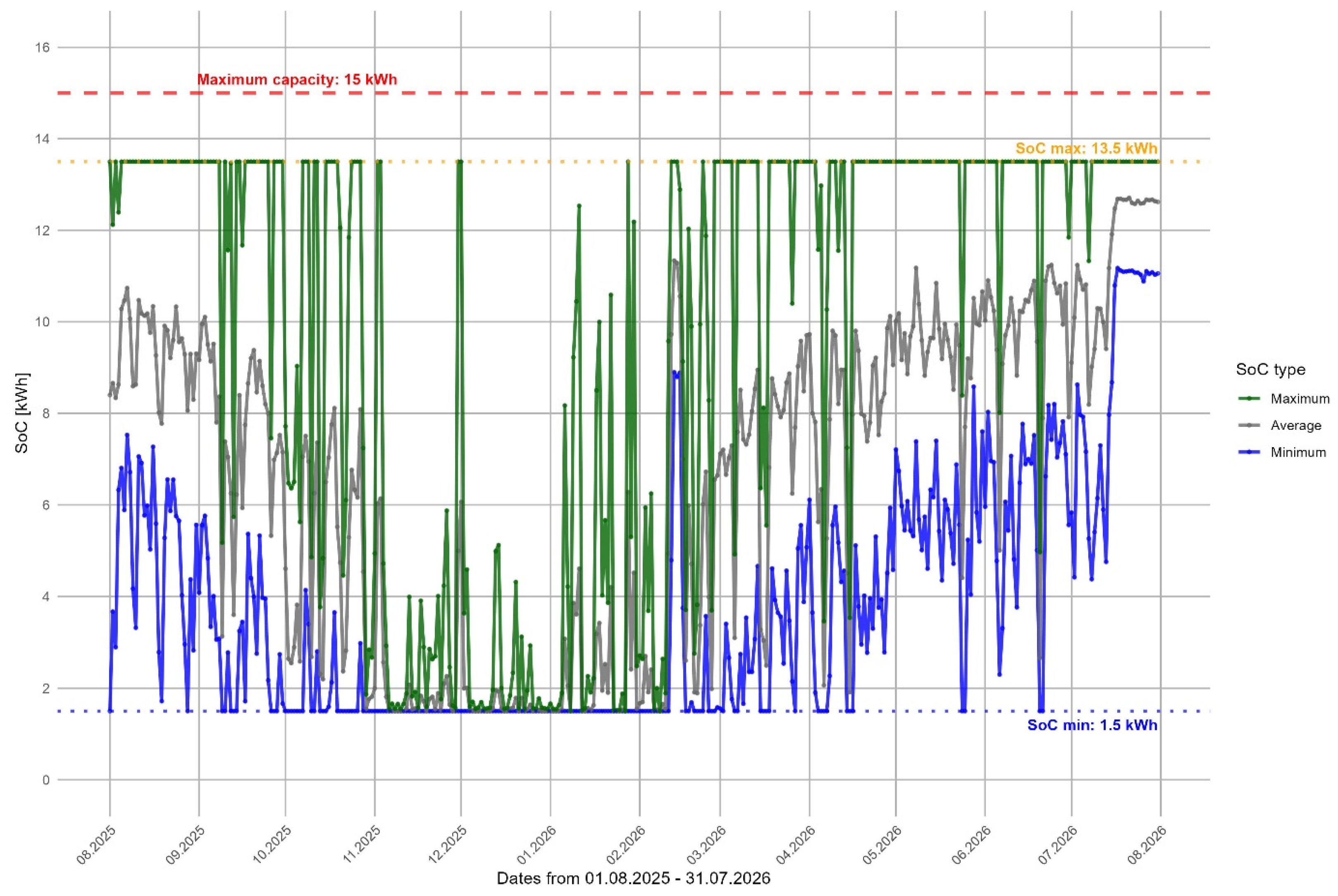

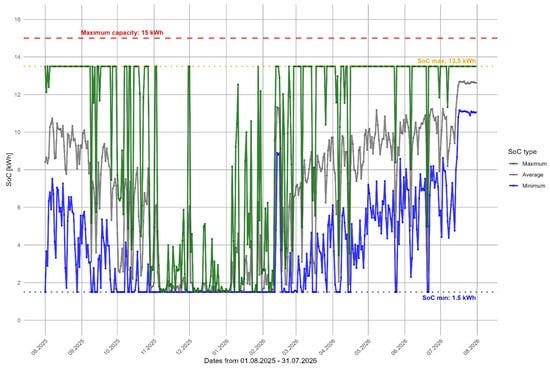

Figure 8 illustrates extended low state-of-charge intervals during winter, confirming that system utilization is limited by irradiance rather than storage capacity. High SOC levels occur regularly in summer, indicating that without additional flexible loads, surplus generation cannot be effectively absorbed. Together, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show that increasing battery size would not materially improve winter performance because the underlying constraint is seasonal generation, not storage availability.

Figure 8.

Battery storage state of charge during the first year of system operation. Source: simulation results (2025–2035).

3.4. Intangible and Hard-to-Quantify Benefits of Implementing a PV-BESS System

Although the economic evaluation focuses on measurable cash flows, residential PV-BESS installations provide several qualitative benefits that are not captured by NPV or IRR. These include short-term resilience during grid outages, improved behind-the-meter voltage stability, and reduced exposure to electricity price volatility under the net-billing regime. In systems equipped with a sine-wave-generating inverter, the household network can also be stabilized in situations where the external grid remains operational but experiences voltage fluctuations or instability, effectively isolating the domestic installation from power-quality disturbances. The system also increases operational independence by enabling a higher share of self-consumed energy and reducing reliance on external supply during peak-demand periods or adverse grid conditions. In addition, extending system operation beyond the modeled ten-year horizon may generate further non-monetary gains, although long-term equipment aging introduces uncertainties that fall outside the present analysis. Forthcoming regulatory developments—such as hourly settlement, dynamic tariffs, or incentives for local balancing—could further enhance the practical attractiveness of storage by increasing the value of flexibility and on-site demand shifting. While these effects are difficult to quantify, they represent relevant ancillary benefits that may influence household investment decisions and long-term PV-BESS adoption.

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimization of the Scale of the Photovoltaic and Energy Storage System

The interpretation of system performance in this section directly follows from the modeling framework outlined in Section 2, where production, consumption and storage processes were simulated in 15 min resolution under net-billing constraints. All observations regarding the economic viability of PV-BESS configurations therefore arise endogenously from the model—specifically from the interaction among stochastic PV generation, household demand profiles, conversion losses and storage state-of-charge dynamics. This ensures that the conclusions presented below remain fully consistent with the physical and financial assumptions defined in the Materials and Methods section.

Numerous authors emphasize that minimizing energy costs requires the simultaneous optimization of photovoltaic installations and energy storage systems [45,46]. The described simulation model facilitates the comparison of different hardware configurations, enabling the selection of the most suitable option based on the consumption profile. We conducted simulations of a PV-BESS system across nine configurations, utilizing efficiency indicators and results from home energy production and consumption simulations. Each configuration comprised 7, 10, or 14 panels rated at 430 Wp, resulting in total powers of 3.0 kWp, 4.3 kWp, and 6.0 kWp, respectively, along with energy storage systems of 5, 10, and 15 kWh capacities. Table 5 summarizes the results of these simulations.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis results for investment efficiency relative to panel size and energy storage capacity.

To ensure comparability, the same production profile (as presented in Table 2) was utilized in the sensitivity analyses, given the random elements in consumption and production profiles. This involved maintaining the order of drawing production years in the simulated future years of system operation and using an identical equipment usage profile previously established in the household electricity consumption simulation procedure. A fundamental sensitivity analysis facilitates the optimal alignment of storage capacity with PV panel power through a two-dimensional examination of the results based on these parameters.

Table 5 presents the variations in capital expenditures for all examined combinations of system sizes in the Investment Expenditures section. Table 5 in section Sum of CF presents the aggregate of negative and positive cash flows without applying any discounting. This represents the net surplus from project implementation, excluding the individual’s cost of capital. This exemplifies the scenario of an individual maintaining their surplus in a non-interest-bearing bank account. The net surplus remains modest, peaking at EUR 1637. When the cost of capital is set at a minimum level of 3.1%, the discounted net surplus (namely NPV) decreases to EUR 599. Only four of the nine combinations of PV panel and energy storage sizes demonstrate operational efficiency, which is, in all instances, modest. The IRR in the optimal scenario is 5.3% (6.0 kWp + 15 kWh), whereas in the other efficient scenarios, it is 4.5%, 4.3%, and 3.6%. This is in relation to a cost of capital of 3.1%, indicating a limited margin of safety. The medium-range installation scenario (4.3 kWp + 10 kWh) yields a marginally positive efficiency, with the internal rate of return (IRR) exceeding the assumed cost of capital by only 0.5%. The analysis indicates that, given the system configuration and consumption, investment efficiency can be attained; however, even in the optimal scenario, net benefits, after accounting for the cost of capital, remain modest. This leads to a limited margin of economic security for the investment, effectively excluding it from bank financing unless supplemented by external sources, such as subsidies. Installation costs are similarly affected. Outsourcing the installation of a PV-BESS system to a third party leads to inherent project inefficiencies.

Across all configurations, the simulations indicate that economic viability is achieved only within the upper range of system sizes. The 6 kWp + 15 kWh configuration is the only variant that consistently delivers a positive NPV at the assumed electricity price and cost of capital. All smaller systems either remain marginal or fall below the break-even point, which confirms that the financial margin is structurally narrow and highly sensitive to system sizing.

The limited profitability observed across the evaluated configurations results primarily from the seasonal imbalance between PV supply and household demand. These results are consistent with expectations for residential PV-BESS operating in a Northern-European irradiance regime, where winter solar production is insufficient to sustain high storage utilization. As a consequence, annual self-consumption remains structurally limited and financial performance is driven primarily by consumption during the summer half-year. The system operates with high utilization only in late spring and summer, while winter periods rely almost entirely on grid imports, which structurally restricts annual self-consumption. In addition, inverter idle consumption, conversion losses and battery round-trip inefficiencies erode a significant share of generated energy, further reducing the monetary value of savings. These factors jointly explain why even technically adequate system sizes yield only marginal financial performance under current Polish net-billing conditions. These findings also reinforce the importance of regulatory instruments—such as dynamic tariffs, hourly settlement or compensation mechanisms for winter balancing—in improving the economic viability of residential PV-BESS under such climatic conditions. Net-metering prosumers can already be billed at zero prices for exported electricity, which structurally limits the financial value of surplus production and further increases the relative importance of self-consumption and storage within residential PV-BESS systems.

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Results to Fundamental Economic Variables

Table 6 provides a sensitivity analysis of capital expenditures. This enables the assessment of the feasibility of incorporating higher-cost components in the PV-BESS system. The results of this analysis are straightforward to anticipate; as capital expenditures function without discounting, an increase in expenditures correspondingly diminishes the NPV. The system variant featuring the highest number of panels and the most extensive energy storage system demonstrates that a 12.4% rise in expenditures renders the investment unprofitable. This represents an increase of EUR 599, which corresponds precisely to the NPV value in this variant.

Table 6.

Sensitivity of NPV to changes in capital expenditures (CAPEX).

The project must consider a higher cost of capital if financed through a loan, given that the prevailing interest rate in Poland exceeds 10%. The project’s financing structure could increase the cost of capital to a range of 7% to 15%. The weighted average cost of capital (WACC), a fundamental concept in corporate finance, should be applied in this scenario. This denotes the average cost of equity (investor capital) and debt (loan capital), weighted according to the capital structure (the proportion of financing for each component within the overall project financing). The procedure for determining the cost of capital can similarly be applied by a private investor, excluding the influence of the interest tax shield, as it is not relevant in this context. Table 7 illustrates the effect of an increased cost of capital on the efficiency of a 6 kWp + 15 kWh project. The results show that project viability is highly sensitive to both the electricity price and the investor’s cost of capital. The system becomes clearly profitable only at electricity prices of approximately EUR 0.2920–03504/kWh, while prices below EUR 0.1752/kWh drive the NPV sharply negative, even under a zero-cost-of-capital scenario. Furthermore, increasing the cost of capital from 3.1% to 10–15% substantially depresses NPV, indicating that financing conditions constitute a binding constraint on the economic feasibility of residential PV-BESS systems.

Table 7.

NPV sensitivity to energy price and investor’s cost of capital.

The second dimension of Table 7 pertains to the price of electricity sourced from the grid, focusing on its variable component, which encompasses the cost of energy transmission. An increase in electricity prices enhances outcomes, as it leads to greater monetary savings despite maintaining the same level of electricity consumption reduction from the grid. A substantial reduction in electricity prices will hinder the project’s economic efficiency. Conversely, any rise in electricity prices exceeding inflation will enhance the project’s efficiency.

The sensitivity results presented in Table 7 are deterministic with respect to capital expenditures and electricity prices. Although the production and consumption profiles originate from stochastic year-to-year variation, the economic outcomes do not incorporate uncertainty bounds for CAPEX or future tariff trajectories. A full probabilistic treatment, such as Monte Carlo simulation of cost and price scenarios was not implemented, which constitutes a limitation and implies that the reported NPV values represent point estimates rather than a distribution of possible outcomes. Moreover, the assumption of self-installation and a uniform 3.1% cost of capital limits the generalizability of the results, as professionally installed systems or higher financing costs would materially reduce economic performance.

The model also reveals that a two-week reduction in household demand during the peak summer irradiance period (annual vacation) lowers the system’s overall economic efficiency by approximately EUR 292, a loss that is explicitly incorporated into our results. This effect is rarely addressed in the PV-BESS literature despite its practical relevance for household investors, as reduced occupancy systematically lowers self-consumption during periods of maximum photovoltaic yield.

A significant issue regarding the economic efficiency of residential photovoltaics in Poland is the low Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR). Research indicates that in Polish households, the range of PV self-consumption is between 22% and 28% [3]. A case study in southern Poland, performed in real-world conditions, demonstrated that an integrated PV-BESS system achieved the shortest payback period of 9.0 years with financial support, 11.8 years without, leading to self-consumption rate of 56.3% [8]. In our model, the simple payback period is 8.0 years, SCR achieves 42,4% and reduction in the original AC consumption before installation of the PV-BESS system amounts to 64.3%. For a comparable PV installation size, the panel tilt angle in our model differs, which promotes higher production, especially during the winter-to-summer transition period. The solutions also differ in pricing parameters and grid billing methods. European study conducted in Croatia indicates that the optimal economic decision results in the installation of 2.5 kWp, which is significantly influenced by the discount rate [17]. In our study, the optimal size is 6 kWp, which is justified by the more northern location of our system. In a study by Hoppmann et al. [16], the optimal PV-BESS system size for Germany was estimated at 7 kWp of PV power and 7 kWh of battery capacity. Our optimal system configuration of 6 kWp + 15 kWh reflects the differences in electricity prices, investment costs between these solutions, and energy storage technology. Comparisons between the results of different studies are difficult due to differences in the technical parameters of the systems, solar radiation and PV panel settings, prices at the time of investment and energy market settlement conditions.

Taken together, the size-optimization and economic-sensitivity results provide a coherent picture: PV-BESS viability in Poland is structurally limited by seasonal mismatch, conversion losses and narrow savings margins. The results reinforce earlier evidence from CEE that storage is most beneficial in summer but underutilized in winter, which depresses annual self-consumption. Economic outcomes are therefore highly dependent on hardware costs and electricity price trajectories, both of which exhibit significant uncertainty. These findings suggest that system feasibility is contingent not only on technical sizing but also on regulatory and market conditions.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Conclusions

The analysis indicates that through careful selection of system components, considering the present state of the photovoltaic panel and energy storage market, as well as current electricity prices, it is feasible to attain a low yet positive efficiency of the PV-BESS system in Poland without the need for subsidies. The 6 kWp/15 kWh configuration delivers a positive NPV under baseline assumptions.

Energy policy trends in the EU, including the Clean Industrial Deal and the increasing penetration of intermittent renewable generation, indicate that distribution grids will face greater operational volatility and rising network reinforcement costs. Recent large-scale grid failures in Europe [47] highlight the growing importance of household-level resilience, although these events remain difficult to quantify in financial models. In this context, PV-BESS systems may provide additional value by stabilizing behind-the-meter voltage, maintaining supply during short-term outages, and reducing exposure to dynamic retail tariffs or hourly settlement mechanisms expected in the coming years. The potential extension of system operation beyond the 10-year horizon also introduces non-financial considerations related to long-term equipment aging, inverter replacement cycles and battery degradation, which, while not included in the economic model, affect real-world viability. These factors suggest that the economic and operational environment for residential PV-BESS systems may gradually strengthen as regulatory frameworks increasingly reward flexibility, local balancing and self-consumption.

Overall, the findings indicate that the economic performance of residential PV-BESS systems remains strongly dependent on regulatory design and future electricity price trajectories, with profitability concentrated in configurations that maximize self-consumption. For residential investors, the results imply that PV-BESS viability under Polish net-billing conditions requires careful assessment of component costs, discount rates, degradation risks and household load profiles before committing capital. For Polish energy policy, the findings suggest that net-billing creates incentives for regulatory instruments and tariff designs that reward higher self-consumption and flexibility, thereby enhancing the economic role of residential storage and supporting more stable operation of distribution networks.

5.2. Limitations

The resulting positive performance indicator strongly depends on the assumptions made, which are also limitations of the presented model. These assumptions include:

- electricity consumption reflective of an active four-person household,

- uninterrupted system operation for a duration of 10 years,

- energy prices increasing in accordance with inflation,

- self-installation by the end user, followed by verification from an electrician,

- financing sourced from the investor’s personal funds, without reliance on bank financing.

The last two assumptions may require systemic solutions that would enable widespread implementation of such projects.

5.3. Future Research

Given the model’s design and the input data used, it can serve as a basis for further analyses. In particular, future research directions include:

- Examining actual operating conditions across diverse locations (input data across nearly 5000 locations in Central Europe) which can reveal the influence of microclimate on energy production and storage operation;

- Integrating diverse household energy consumption profiles into the analysis, including changes related to children maturing and evolving daily routines, electric vehicle charging, or air conditioning usage during the summer months;

- Assessing the impact of dynamic electricity tariffs on system efficiency;

- Exploring advanced control strategies for the storage system, including the regulation of maximum charge and minimum discharge levels in response to seasonal fluctuations in solar radiation.

Taken together, the findings demonstrate that the long-term economic and operational relevance of residential PV-BESS systems will depend on both technological progress and the evolution of regulatory frameworks in Poland and the EU. Continued empirical validation and methodological refinement will be essential to develop robust, policy-relevant assessments of household-level energy flexibility resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W. and M.P.; methodology, T.W. and M.P.; software, T.W.; validation, T.W. and M.P.; investigation, T.W.; data curation, T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, T.W. and M.P.; visualization, T.W.; project administration, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Alternating Current |

| B/C | Benefit Costs Ratio |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage Systems |

| BTM ESS | Behind-The-Meter Energy Storage Systems |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DPBP | Discounted Payback Period |

| FIT | Feed-in Tariff |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| NBP | National Bank of Poland |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| PBP | Payback Period |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PV-BESS | Photovoltaic system coupled with battery energy storage |

| PVGIS | Photovoltaic Geographical Information System |

| SCR | Self-Consumption Ratio |

References

- Chatzistamoulou, N.; Koundouri, P. Is Green Transition in Europe Fostered by Energy and Environmental Efficiency Feedback Loops? The Role of Eco-Innovation, Renewable Energy and Green Taxation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 1445–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnicki, P.; Luft, R.; Wójtowicz, Ł. Evolution and Impact of the European Union’s Energy Policy: From Fossil Fuels to Renewable Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewierski, T.; Wędzik, A.; Szypowski, M. Optimising Sustainable Home Energy Systems Amid Evolving Energy Market Landscape. Energies 2025, 18, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurasz, J.; Ceran, B.; Orłowska, A. Component degradation in small-scale off-grid PV-battery systems operation in terms of reliability, environmental impact and economic performance. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 38, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M. Photovoltaic energy systems with battery storage for residential areas: An economic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourasl, H.H.; Vatankhah Barenji, R.; Khojastehnezhad, V.M. Solar Energy Status in the World: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 3474–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instytut Energetyki Odnawialnej (IEO), Rynek Fotowoltaiki w Polsce 2025. Fotowoltaika na Rynku Energii Elektrycznej i Ciepła, 13th ed.; IEO: Warsaw, Poland, 2025; Available online: www.ieo.pl (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Goryl, W. Real-World Performance and Economic Evaluation of a Residential PV Battery Energy Storage System Under Variable Tariffs: A Polish Case Study. Energies 2025, 18, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipaschalis, I.; Poullikkas, A.; Efthimiou, V. Overview of current and future energy storage technologies for electric power applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A. Maximizing solar PV energy penetration using energy storage technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.C.; Østergaard, J. Battery energy storage technology for power systems—An overview. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2009, 79, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkuriyingoma, O.; Özdemir, E.; Sezen, S. Techno-economic analysis of a PV system with a battery energy storage system for small households: A case study in Rwanda. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 957564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeimozafar, M.; Monaghan, R.F.D.; Barrett, E.; Duffy, M. A review of behind-the-meter energy storage systems in smart grids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 164, 112573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadnan Sakib, S.; Hossain, M.B.; Zamee, M.A.; Hossain, M.J.; Habib, M.A. Role of Battery Energy Storage Systems: A Comprehensive Review on Renewable Energy Zones Integration in Weak Transmission Networks. J. Energy Storage 2025, 128, 117223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalcazar, P.; Kalka, M.; Kamiński, J. From consumer to prosumer: A model-based analysis of costs and benefits of grid-connected residential PV-battery systems. Energy Policy 2024, 191, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppmann, J.; Volland, J.; Schmidt, T.S.; Hoffmann, V.H. The economic viability of battery storage for residential solar photovoltaic systems–A review and a simulation model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimić, Z.; Topić, D.; Crnogorac, I.; Knežević, G. Method for Sizing of a PV System for Family Home Using Economic Indicators. Energies 2021, 14, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufo-López, R.; Bernal-Agustín, J.L. Techno-economic analysis of grid-connected battery storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 91, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzke, N.; Büchle, F.; Smith, A.; Hiller, M. Influence of Efficiency, Aging and Charging Strategy on the Economic Viability and Dimensioning of Photovoltaic Home Storage Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinna, B.C.; Okedu, K.E.; Kalnoor, G.; Raju, L.; Krishna, V.B.M.; Colak, I. Economic Analysis of Off-Grid Energy Projects: A FINPLAN Model Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 83916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deotti, L.; Guedes, W.; Dias, B.; Soares, T. Technical and Economic Analysis of Battery Storage for Residential Solar Photovoltaic Systems in the Brazilian Regulatory Context. Energies 2020, 13, 6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerino Abdin, G.; Noussan, M. Electricity storage compared to net metering in residential PV applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, A.; Jahed, A.; Ahmadi, A. Techno-economic analysis of PV–wind–diesel–battery hybrid power systems for industrial towns under different climates in Spain. Energy Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2831–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsipe, O.C.; Moya, D.; Kaparaju, P. Design and economic analysis of off-grid solar PV system in Jos-Nigeria. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvönen, J.; Santasalo-Aarnio, A.; Syri, S.; Lehtonen, M. Feasibility study of energy storage options for photovoltaic electricity generation in detached houses in Nordic climates. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic Self-Consumption in Buildings: A Review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, H.; Dauenhauer, P. Effects of load estimation error on small-scale off-grid photovoltaic system design, cost and reliability. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 34, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Yin, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xin, Y. Photovoltaic power prediction based on DBSCAN and BiLSTM-transformer. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3074, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Stelt, S.; Alskaif, T.; van Sark, W. Techno-economic analysis of household and community energy storage for residential prosumers with smart appliances. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, M.; Gamberi, M.; Graziani, A. Technical and economic design of photovoltaic and battery energy storage system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 86, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelic, M.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Blaabjerg, F. Impact of Power Converters and Battery Lifetime on Economic Profitability of Residential Photovoltaic Systems. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2022, 3, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. J. Financ. Econ. 2001, 60, 187–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andor, G.; Mohanty, S.K.; Toth, T. Capital budgeting practices: A survey of Central and Eastern European firms. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2015, 23, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brounen, D.; De Jong, A.; Koedijk, K. Corporate finance in Europe: Confronting theory with practice. Financ. Manag. 2004, 33, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brealey, R.A.; Myers, S.C.; Allen, F. Principles of Corporate Finance, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran, A. Investment Valuation: Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.A.; Westerfield, R.W.; Jaffe, J.; Jordan, B.D. Corporate Finance, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jurek, J.W.; Stafford, E. The Cost of Capital for Alternative Investments. J. Financ. 2015, 70, 2185–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBP. Informacja o Aktywach Finansowych i Zobowiązaniach Gospodarki Polskiej w I Kwartale 2025 r. na podstawie rachunków finansowych; Departament Statystyki, Narodowy Bank Polski: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. Available online: https://static.nbp.pl/dane/statystyka/rachunki-finansowe/archiwum/Informacja_o_aktywach_finansowych_i_zobowiazaniach_gospodarki_polskiej_w_I_kwartale_2025.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).