1. Introduction

In recent years, thermoelectric power generation systems based on thermoelectric generator modules (TEGs) have emerged as promising alternatives for low-power applications and waste heat recovery [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These devices, based on the Seebeck effect, directly convert temperature differences into electrical energy, offering advantages such as the absence of moving parts, low maintenance, and modular scalability [

5]. However, the conversion efficiency of TEGs remains limited, being strongly influenced by the applied thermal gradients and the characteristics of the semiconductor materials employed [

6,

7].

Beyond the intrinsic physical limitations of the thermoelectric material, the energy performance of TEG systems also depends on the proper use of electronic converters and maximum power point tracking (MPPT) techniques [

8]. In environments with thermal variation and dynamic load behavior, MPPT algorithms become fundamental to ensuring operation near the point of maximum energy transfer, minimizing losses, and optimizing power extraction from the generators [

9,

10,

11].

Several approaches have been proposed in the literature to implement MPPT in thermoelectric systems [

12,

13]. While extensive comparisons exist for Photovoltaic (PV) systems, specific literature regarding Multistring TEG arrays remains less comprehensive. Current methodologies range from classic methods like Perturb and Observe (P&O) and Incremental Conductance (InC) [

14] to meta-heuristic techniques such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Each of these methods has specific characteristics regarding accuracy, response time, robustness against environmental variations, and computational complexity [

19,

20]. However, most comparative studies focus on uniform thermal conditions, often neglecting the complex multi-peak phenomena that arise in large-scale multistring TEG configurations under asymmetric gradients.

This research is part of a broader line of research and development (R&D) by the Energy and Sustainability Research Group (GPEnSE), focused on the development of solid-state generators, self-powered devices, and autonomous sensors based on energy harvesting [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. While previous comprehensive design methodologies developed by the group were crucial for optimizing TEG proofs of concept, the selection of effective control strategies remains a fundamental subset for ensuring maximum power extraction in these autonomous devices. The comparative analysis of MPPT algorithms, therefore, becomes an essential step for the practical implementation of such systems.

In this context, the present study aims to conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis of different MPPT algorithms applied to TEG systems, considering various thermal operation scenarios and gradient distribution profiles. For this purpose, computational models were developed in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, encompassing thermoelectric generation blocks, boost converters, and controllers based on each tracking method. The simulation, based on 11 distinct scenarios, evaluates indicators such as tracking efficiency, convergence time, and steady-state stability, with a particular focus on behavior under multiple maximum power points (MPPs).

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

Development of a Scalable Simulation Framework: A reproducible MATLAB/Simulink environment for multistring TEG arrays (up to 196 modules), capable of simulating complex series-parallel configurations and asymmetric thermal gradients often omitted in standard PV-centric literature.

Comparative Assessment of Control Strategies: A rigorous evaluation of four MPPT algorithms (P&O, InC, PSO, and GA) under identical constraint conditions, establishing benchmarks for convergence speed, steady-state ripple, and tracking accuracy in multi-peak scenarios.

Analysis of Algorithm Limitations in Non-Uniform Gradients: The study explicitly categorizes failure modes of classical algorithms in specific thermal asymmetry scenarios, providing design guidelines for selecting control strategies in real-world waste heat recovery applications where thermal uniformity cannot be guaranteed.

This paper is structured to guide the reader through the modeling, development, and performance analysis of MPPT algorithms for thermoelectric energy harvesting.

Section 2 presents the conceptual design of the simulation framework, including the computational modeling of thermoelectric modules, implementation of the four MPPT algorithms (P&O, InC, PSO, GA), and the construction of eleven thermal scenarios.

Section 3 details the numerical analysis of the simulations and presents a comparative performance evaluation based on convergence time, tracking accuracy, and power ripple.

Section 4 discusses the results and highlights the strengths and limitations of each algorithm in ideal and complex scenarios. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions and outlines future research directions for experimental validation and modeling improvements.

2. Design, Computational Modeling, and Development

This section details the methodology employed in the development and simulation of the system components. It addresses the modeling of the thermoelectric generator (TEG), the implementation of Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) algorithms, and finally, the design of the thermal and electrical scenarios used to validate and compare the performance of the methods. The computational tools and simulation parameters are described to ensure the reproducibility of the results.

2.1. Thermoelectric Module Modeling

The modeling focuses on the power generation of thermoelectric generator (TEG) modules, primarily considering the Seebeck coefficient, internal electrical resistance, and temperature gradients. Thermal resistance and convection aspects were disregarded, as they are assumed to not significantly alter the steady-state P-V curve shape for the purpose of MPPT algorithm comparison.

The MATLAB® and Simulink® (Version R2023a) software programs were employed for modeling and simulation. MATLAB® was used for algorithm testing and graph generation, while Simulink® allowed for the assembly of the converter circuit, TEG blocks, and MPPT methods, leveraging its libraries of electrical components, logic gates, and controllers.

The simulation parameters were based on [

30,

31]. The Seebeck coefficient and internal resistance parameters were extracted from the inbC1-127.08HTS module datasheet and applied uniformly to all TEGs, varying only the thermal gradient and the series/parallel configuration. The primary data of the TEG modules used in the simulations are summarized in

Table 1.

The structure of the TEG simulation block is presented in

Figure 1. The internal view (a) shows the “ΔT Gradient” block calculating the difference between the TH and TC temperatures. This gradient is multiplied by the Seebeck coefficient and the number of modules in series, resulting in the open-circuit voltage (VOC) applied to a controlled voltage source and internal resistance. The external view (b) shows the block as implemented in Simulink.

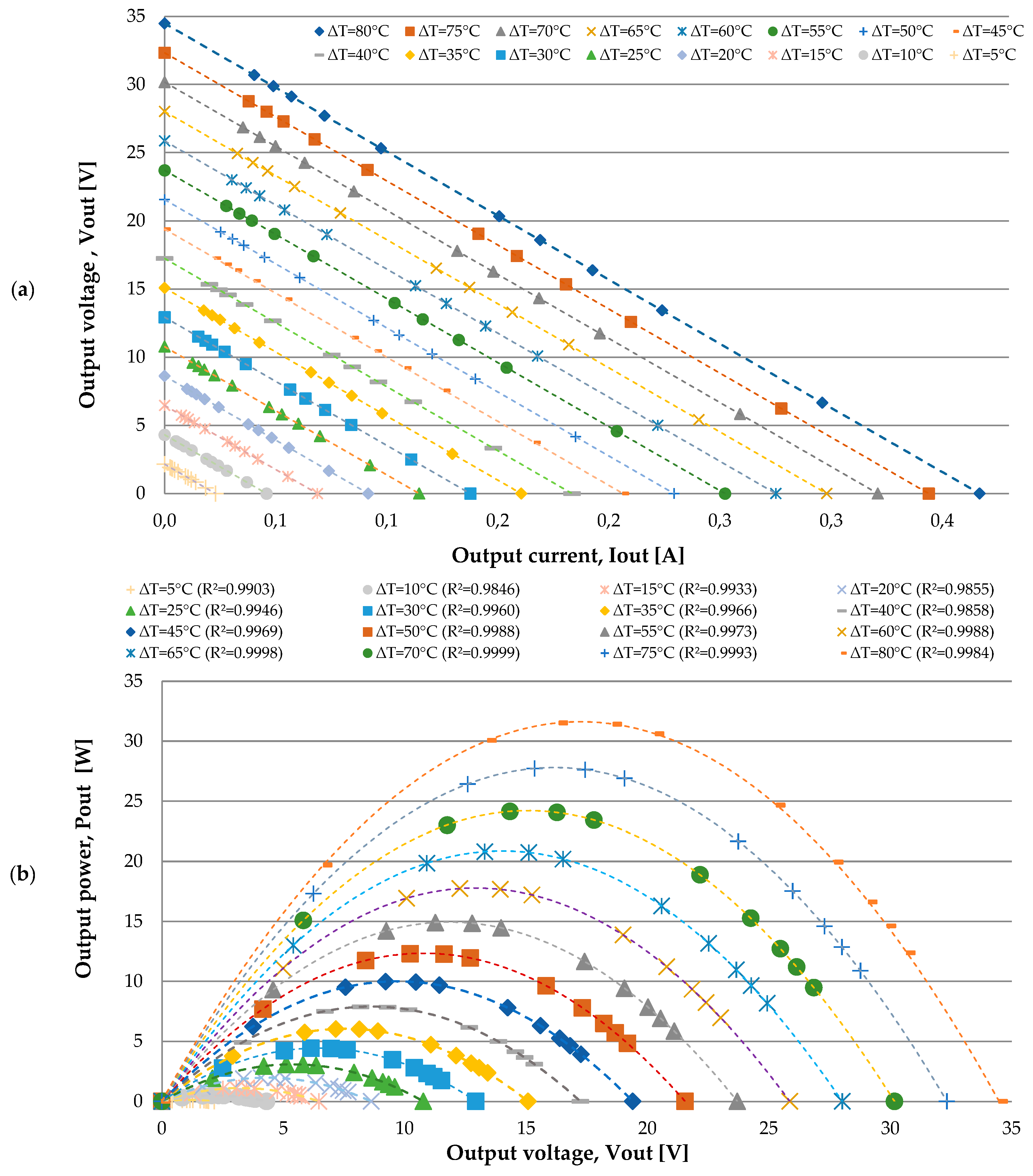

Figure 2 illustrates the linearity of the Seebeck law. It is important to highlight the limitations of this modeling approach. The simulation treats TEGs as voltage sources dependent on temperature difference and internal resistance, explicitly disregarding dynamic thermal resistance, convection losses, and the Peltier effect (cooling due to current flow). While these factors influence the absolute magnitude of power generation and thermal settling times in physical systems, the primary objective of this study is the comparative logic of MPPT algorithms under instantaneous electrical P-V curves. The formation of local and global maxima (multi-peak behavior) results fundamentally from the electrical interconnection of modules under different gradients. Therefore, this simplified electrical model is sufficient and valid for stress-testing the tracking algorithms’ ability to navigate complex search spaces, which is the core contribution of this work.

To obtain the characteristic power curves, a variable load circuit, detailed in

Figure 3, was used. This circuit allowed for sweeping the TEG’s operation and generating the I-V (a) and P-V (b) curves presented in

Figure 4, which are fundamental for the analysis of the maximum power point (MPP).

2.2. MPPT Algorithm Implementation

The MPPT block controls the duty cycle of the DC-DC converter based on voltage and current measurements, generating a PWM signal via a comparator and a triangular wave generator. The logic of each algorithm is encapsulated in a MATLAB Function block in Simulink®, with voltage, current, and timer inputs. To smooth the ripple of the DC-DC signals, which affects the measurements, a digital moving average (low-pass) filter with a 100-sample window was adopted. The sampling frequency was ten times higher than the PWM frequency, satisfying the Nyquist criterion and preserving the mean value of the signal. Four distinct MPPT algorithms were implemented for comparison.

The Perturb & Observe (P&O) algorithm, based on [

30], calculates the input power at each period T and compares the voltage (ΔV) and power (ΔP) variations to adjust the duty cycle

. The adjustment parameters used for the P&O method are detailed in

Table 2.

Similarly, the Incremental Conductance (InC) algorithm replaces the absolute variations with approximated derivatives ΔV → AV and ΔI → AI. The adjustment parameters for InC, were kept identical to those of P&O to allow for a direct performance comparison.

For the P&O and InC methods, a fixed step size (Δd = 0.03) was selected. While variable step-size algorithms exist to optimize the trade-off between speed and oscillation, a fixed step was chosen to establish a standardized baseline. This ensures that the comparison focuses on the algorithms’ inherent ability (or failure) to escape local maxima, rather than on the tuning optimization of adaptive steps. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm, introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart [

32] and adapted from the implementation by Raza [

33], begins with a population of N individuals (duty cycles) randomly generated. The velocity (

) and position (

or duty cycle) of each particle are updated at each iteration, according to Equations (1) and (2), respectively.

Stopping criteria include the maximum number of iterations or a percentage approximation to the theoretical power. A re-initialization criterion is activated if the power () or voltage () variation exceeds a threshold, as per Equation (3).

Regarding the stopping criteria, the simulation utilizes a threshold based on the theoretical maximum power to precisely quantify the “Time to Convergence” metric during benchmarking. It must be emphasized that in a physical hardware implementation, where the theoretical global maximum is unknown, the stopping criterion would rely on standard steady-state detection or a fixed generation limit, as is standard in metaheuristic deployments. The theoretical power reference is used here strictly as a simulation validation tool. The adjustment parameters for PSO are defined in

Table 3.

In the simulation environment, the stopping criterion for the PSO algorithm and GA was defined as a percentage approximation of the theoretical maximum power. This approach was adopted exclusively for benchmarking purposes, allowing for a standardized and measurable comparison of convergence times and accuracy across all MPPT techniques under controlled conditions.

However, it is essential to emphasize that this criterion is not applicable in real-world implementations, since the actual global maximum power point (GMPP) is unknown during operation. Consequently, the use of the theoretical power as a reference may artificially favor global search algorithms, such as PSO and the GA, by guiding them directly toward the known optimal region in simulation.

In practical hardware-based systems, alternative and realistic stopping criteria should be used instead, such as: (i) A fixed maximum number of iterations; (ii) A minimal change in fitness or output power across successive iterations; (iii) Detection of steady-state conditions using sliding windows or thresholds; and (iv) Derivative-based convergence (e.g., when dP/dt approaches zero).

Therefore, the use of the theoretical power reference in this study should be interpreted as a simulation-only tool, with no implication or advantage in physical systems. Future work should consider implementing more realistic criteria to better reflect the behavior of MPPT algorithms in embedded applications or real thermoelectric systems.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA) begins with a population of bit sequences (genes) converted into duty cycles. At each generation, selection by relative fitness occurs, followed by random single-point crossover and bit-wise mutation with a probability

.

Table 4 demonstrates the crossover process. The GA configuration parameters are listed in

Table 5.

2.3. Thermal Scenario Development

To comprehensively evaluate the stability, efficiency, and convergence time of the MPPT algorithms, eleven distinct scenarios were designed. The rules for scenario selection were defined to test the algorithms’ performance under multiple critical operating conditions [

34].

Table 6 summarizes the configuration data for each of the eleven simulated scenarios, including the gradient range, theoretical maximum power (MPP), thermal profile, and the number of TEGs.

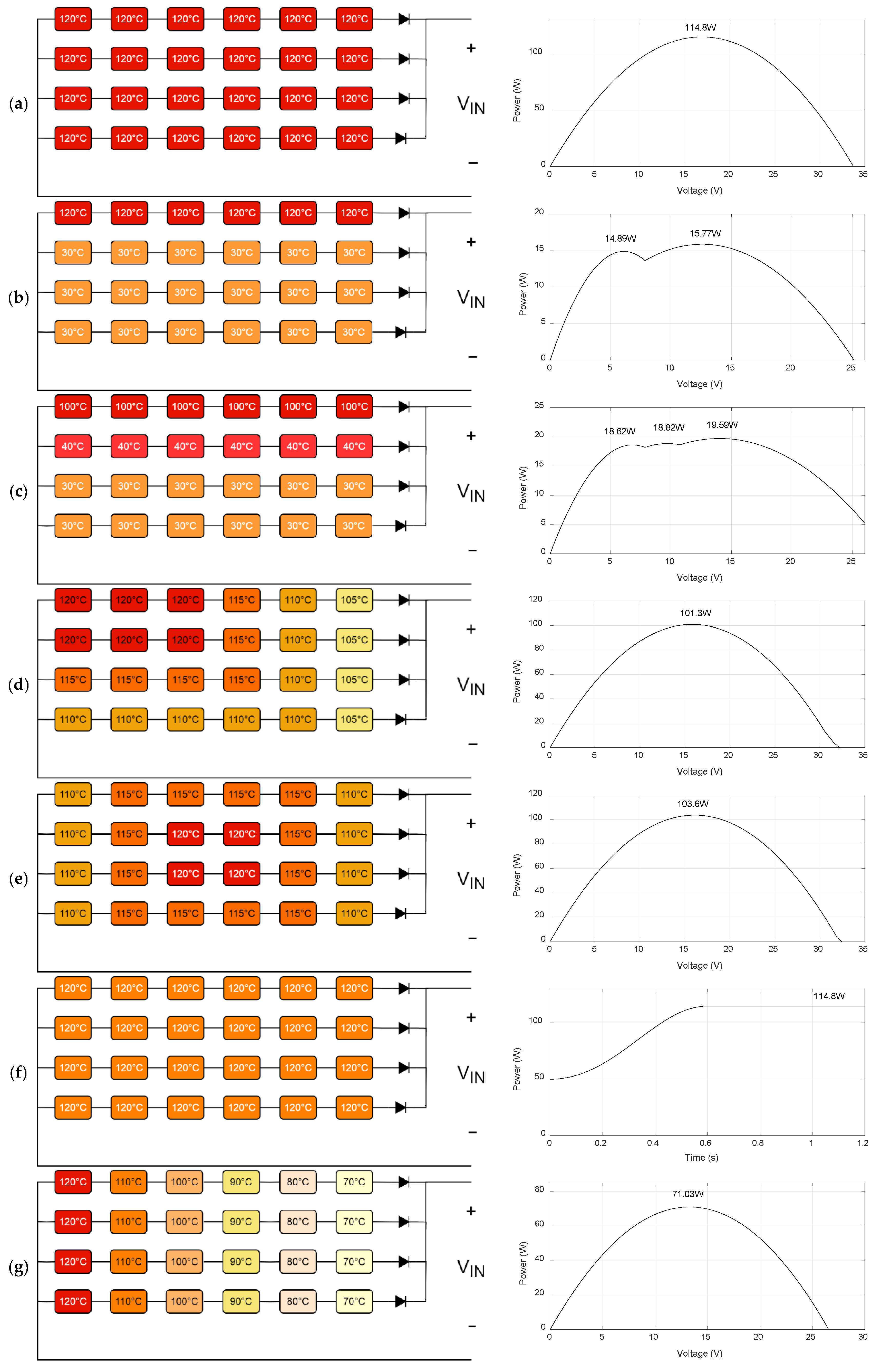

Figure 5 illustrates the TEG connections, while the scenarios analyzed in this research include:

Ideal Conditions (Scenario 1): A constant and uniform thermal gradient to measure baseline performance.

Multiple Maxima Conditions (Scenarios 2–5, 10, 11): Non-uniform gradients (stepped or banded) that create P-V curves with multiple local maximum power points (LMPPs) and a single global maximum power point (GMPP), testing the algorithms’ ability to avoid local optima.

Dynamic Conditions (Scenario 6): A sinusoidal gradient profile to assess the algorithms’ adaptation speed and stability to thermal changes.

Gradient Variations (Scenarios 7, 8): Constant profiles but with different average gradient levels.

Scalability (Scenarios 9–11): An increase in the number of TEG modules (from 24 to 196) to verify convergence time in larger systems.

To provide a visual basis for performance comparison,

Figure 5 illustrates the TEG connections, the spatial distribution of the thermal gradient, and the resulting P-V curves for each of the eleven scenarios (a–k). This figure is crucial for understanding the complexity that each scenario imposes on the MPPT algorithms, especially the formation of multiple power peaks in the non-uniform gradient scenarios.

3. Computational Numerical Analysis and Results

This section presents the numerical simulation results, beginning with the definition of the DC-DC converter design parameters. It then details the comparative analysis of the MPPT algorithms in three selected validation scenarios (ideal, intermediate, and complex), which evaluate the accuracy, speed, and robustness of each method. The section culminates in a general performance evaluation, comparing the algorithms across all eleven simulated scenarios.

3.1. Converter Design Parameters

The converter parameters were chosen considering all implemented simulation scenarios, ensuring that the duty cycles corresponding to the GMPPs and LMPPs remained within the 0.1 to 0.9 range. For this, a load resistance of 16 Ω was selected, the input power was determined, and Equations (4) and (5) were used to guarantee the duty cycles within this range. The inductor and capacitor calculations were performed using Equations (6) and (7), respectively.

They were calculated for all scenarios, and the highest values for both were selected; subsequently, the nearest higher value from the E24 series was chosen for both. The selected switching frequency was 10 kHz, with a current ripple (

) of 30% of the maximum output current and a voltage ripple (

) of 1% of the output voltage. It is important to note that for the large-scale scenarios (up to 196 modules), output voltages can exceed 120 V. Consequently, the component selection implies the use of capacitors and semiconductors with voltage ratings sufficient to withstand these stresses (e.g., >150 V) in a physical implementation. The resulting converter components are summarized in

Table 7.

3.2. Scenario Selection Criteria

To evaluate the performance of the MPPT algorithms in representative situations, three scenarios were selected from the eleven simulated. The selection rules prioritized representativeness of operation, covering an ideal scenario (Scenario 1), an intermediate one with two power peaks (Scenario 2), and a complex one with three peaks (Scenario 3), to encompass different tracking challenges. Furthermore, realism was sought by using conditions of constant and asymmetrically distributed thermal gradients, typical of real thermoelectric system operation (e.g., shading, partial obstructions, gradient variations). Finally, the robustness criterion was applied to evaluate the operational stability, conversion efficiency, and convergence speed of each algorithm under these distinct conditions. Scenario 1 uses 24 modules under a constant gradient (120 °C) with a single MPP. Scenario 2 simulates partial shading (30–120 °C gradients), generating one LMPP and one GMPP. Scenario 3, the most complex, features varied gradients (100 °C, 40 °C, 30 °C), resulting in three close power peaks, demanding greater exploration capability.

3.3. Analysis of Results for Scenario 1: Ideal Conditions

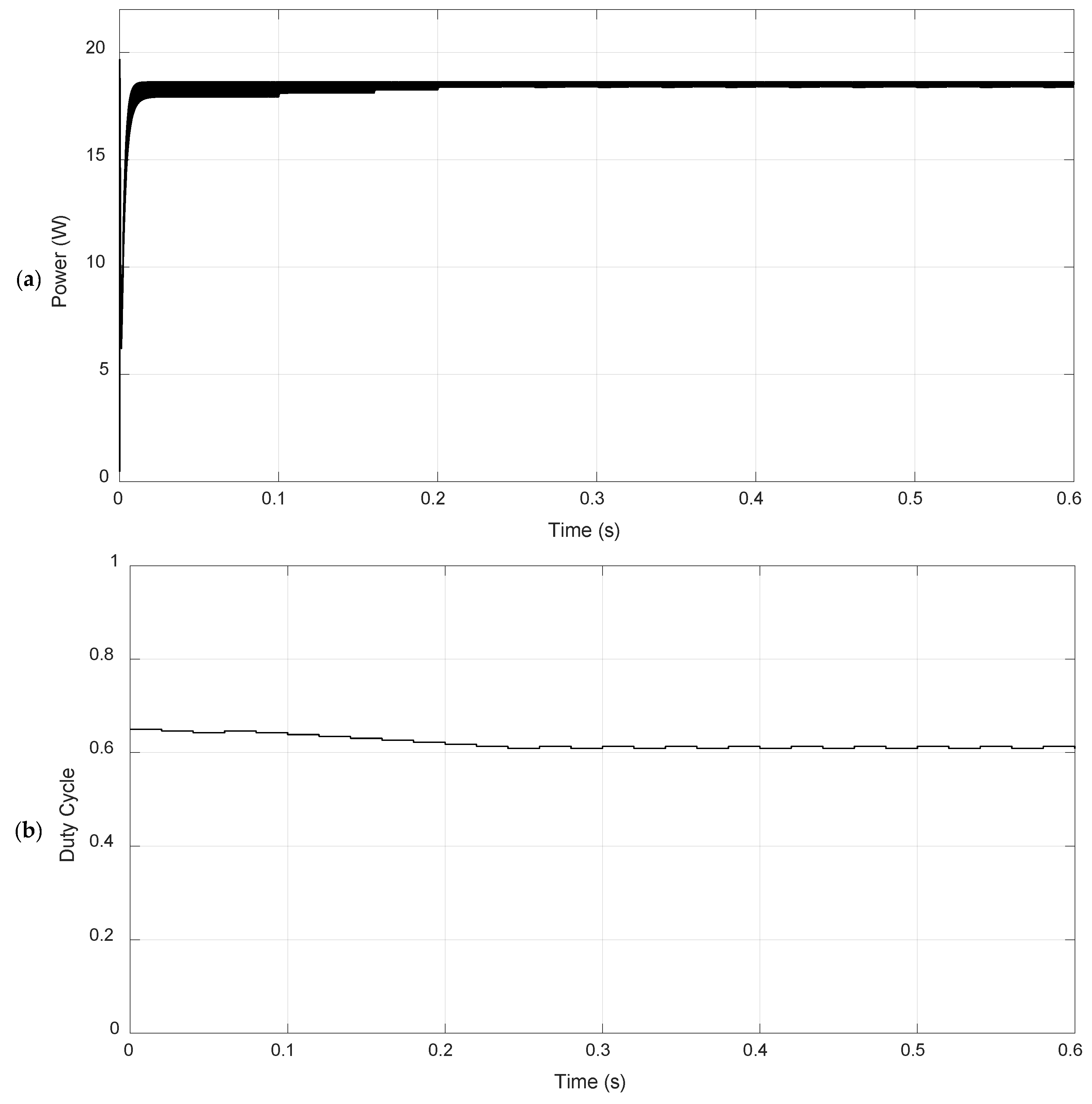

This subsection analyzes the performance of the four algorithms in Scenario 1, an ideal condition with a uniform gradient of 120 °C and a single maximum power point (GMPP) of 114.8 W. This scenario serves as a baseline to measure accuracy and convergence stability under conditions without local maxima.

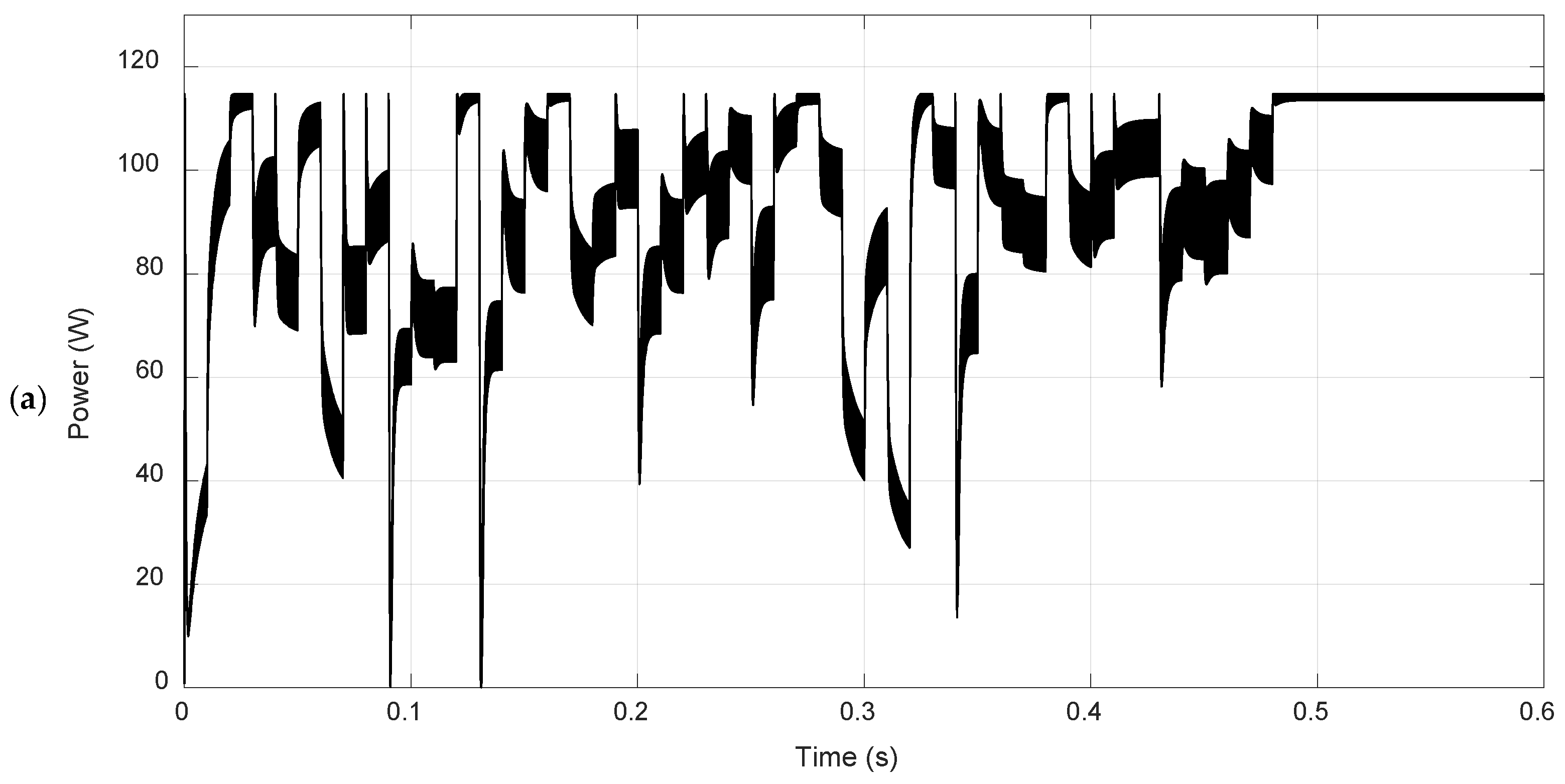

The Perturb & Observe (P&O) method tracked an input power (

) of 114.36 W, corresponding to a relative error of 0.38% compared to the GMPP. The observed power ripple was 2.39 W (2.09%), and the convergence time was 0.30 s, starting from an initial duty cycle of 0.65 and settling at 0.60. The detailed simulation data for P&O are presented in

Table 8. Despite good accuracy in finding the MPP, the algorithm exhibited high ripple, a characteristic behavior of this method which uses constant perturbations. The power and duty cycle curves over time, shown in

Figure 6, demonstrate the incremental nature of the algorithm, which continuously adjusts the duty cycle around the MPP.

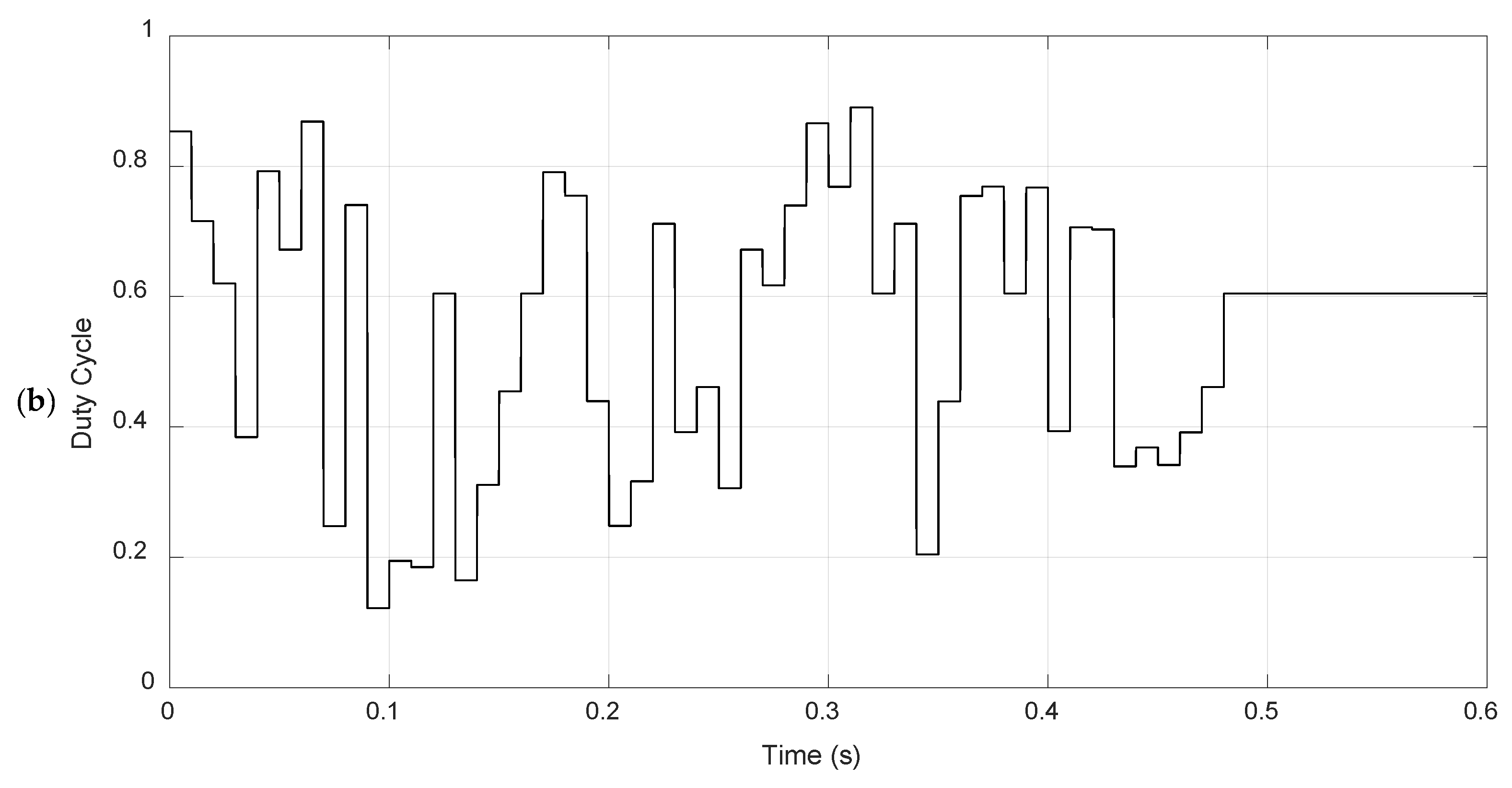

The Incremental Conductance (InC) algorithm resulted in a tracked power of 114.37 W, with a relative error of 0.38% from the MPP and a power ripple of 1.68 W (1.47%), with a convergence time of 0.30 s. This behavior, detailed in

Table 9, shows convergence equal to P&O but with smaller oscillations. Efficiency remained at 97.3%, with a (

) of 111.33 W. The power and duty cycle curves in

Figure 7 show a response and output ripple similar to P&O.

To compensate for the randomness of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), an average of 10 simulations was performed. The average (

) was 114.34 W (0.40% error), and the average convergence time was 0.24 s, the fastest among all methods in this scenario, as consolidated in

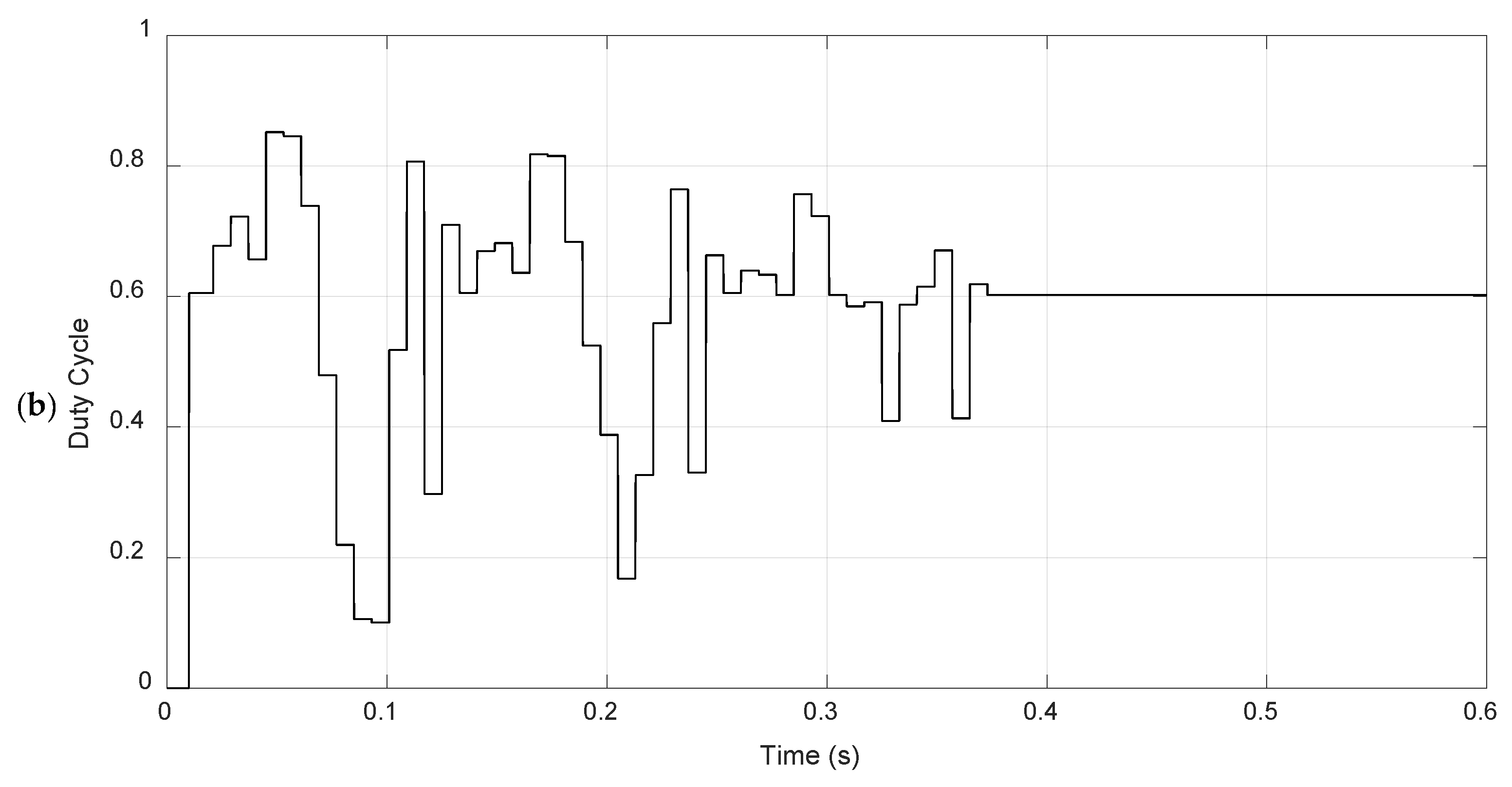

Table 10. The output voltage and current remained at 42.20 V and 2.64 A, with 97.3% efficiency. The duty cycle evolution curves in

Figure 8 show an active search for the MPP, respecting the stopping criterion (99.6% of theoretical power) or the end of iterations, resulting in efficient and stable convergence.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA), also averaged over 10 rounds, tracked

= 114.27 W (0.42% error), with a ripple of 1.80 W (1.56%) and an average convergence time of 0.27 s, as detailed in

Table 11. The average output voltage was 42.19 V, with

= 2.64 A and 97.3% efficiency. The duty cycle behavior in

Figure 9 shows selection and genetic crossover converging to the MPP in a few generations, with stability comparable to PSO.

In summary, under ideal conditions (Scenario 1), all methods achieved errors below 0.5% and efficiency near 97.3%. PSO obtained the shortest convergence time (0.24 s), followed by the GA (0.27 s) and the P&O and InC methods (0.30 s). In terms of ripple, PSO and the GA showed lower voltage and current fluctuations, offering greater stability in power delivery, while P&O and InC, although accurate, maintain higher oscillation levels.

3.4. Analysis of Results for Scenario 2: Intermediate Gradients

In Scenario 2, the algorithms are challenged by a P-V curve with two power peaks (one LMPP and one GMPP of 15.77 W), simulating partial shading conditions. This scenario tests the methods’ ability to avoid local optima.

The Perturb & Observe (P&O) tracked

= 14.83 W, with a relative error of 5.9%, ripple of 0.31 W (2.12%), and a convergence time of 0.30 s. The algorithm converged to a duty cycle of 0.60, near the local maximum (LMPP), resulting in an output power of 13.96 W (94.1% efficiency), as detailed in

Table 12.

The Incremental Conductance (InC) achieved

= 14.84 W (5.91% error), ripple of 0.19 W (1.3%), and convergence in 0.26 s (see

Table 13). The output power was 13.97 W (94.1% efficiency), demonstrating precision and speed similar to P&O, and like it, failing to locate the GMPP.

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) tracked an average

of 15.77 W (0.01% error), ripple of 0.45 W (2.9%), and an average convergence time of 0.07 s. The average output power was 14.92 W (94.5% efficiency). The data in

Table 14 show a superior ability to find the GMPP compared to P&O and InC.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA) obtained an average power of 15.77 W (0.01% error), average ripple of 0.43 W (2.7%), and an average convergence time of 0.06 s, being the fastest in this scenario. As shown in

Table 15, the GA demonstrated the best performance, locating the GMPP with slightly lower ripple values than PSO.

In summary, in Scenario 2, the GA and PSO found the GMPP with the lowest error (0.01%) and similar, rapid average convergence times, with the GA being slightly faster (0.06 s) than PSO (0.07 s). P&O and InC failed to locate the GMPP, converging on a local maximum and confirming their limitations on curves with multiple peaks.

3.5. Analysis of Results for Scenario 3: Complex Multi-Peak Gradients

Scenario 3 represents the most complex condition, with three close power peaks (GMPP of 19.59 W) due to varied thermal gradients (100 °C, 40 °C, 30 °C). This analysis tests the exploration capability and robustness of the algorithms.

The Perturb & Observe (P&O) method tracked

= 18.55 W (5.3% error), ripple of 0.39 W (2.11%), and converged in 0.30 s. However, as detailed in

Table 16, it remained at the first local maximum (LMPP), resulting in an output power of 17.56 W (94.7% efficiency).

The Incremental Conductance (InC) also converged to the same LMPP, tracking

= 18.56 W (5.3% error) and taking 0.26 s, with a ripple of 0.25 W (1.3%). The data in

Table 17 show that

was 17.57 W (94.7% efficiency), exhibiting the same limitation as P&O.

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) tracked an average

of 19.59 W (0.01% error), ripple of 0.58 W (3.0%), and converged, on average, in 0.07 s. The average

was 18.63 W (Efficiency 95%).

Table 18 demonstrates PSO’s good exploration capability in the presence of three peaks.

The Genetic Algorithm (GA) obtained

= 19.59 W (0.01% error), ripple of 0.53 W (2.7%), and converged in an average time of 0.05 s, with

= 18.63 W (Efficiency 95.0%).

Table 19 indicates that the GA showed robustness at the GMPP and the shortest search time in this scenario.

In the most complex scenario, the meta-heuristic algorithms (PSO and GA) were highly effective, both locating the GMPP with near-zero error (0.01%). The GA was the fastest algorithm, converging in just 0.05 s, followed closely by PSO at 0.07 s. P&O and InC failed to bypass the first local maximum, resulting in significant power losses (5.3% error).

3.6. General Comparison Metrics Across All Scenarios

Using the results obtained from the simulations of all eleven proposed scenarios,

Table 20 was prepared with the main performance indicators of the analyzed algorithms, aiming to allow a comprehensive comparison between the different MPPT approaches. The table presents, for each scenario and method, values such as the tracked power at the converter input (

), the percentage error relative to the theoretical maximum power (ϵ), the power effectively delivered to the load (

), the convergence time (t) in seconds, and the converter efficiency (η).

This table allows for an objective analysis of the advantages and limitations of each technique. It was observed, for example, that the P&O and InC methods maintained low errors (<0.5%) only in simple, single-peak scenarios, but demonstrated high error rates (>5%) and failed to find the GMPP in complex scenarios (e.g., 2, 3, 10, 11). On the other hand, algorithms like PSO and the GA demonstrated superior robustness and agility in convergence, successfully finding the GMPP in complex cases, with times often below 0.20 s. The table demonstrates how the performance of the algorithms is directly related to the complexity of the P-V curve.

It is also important to note that although the PSO algorithm and GA were executed independently 10 times to enable statistical evaluation, all simulation runs produced identical results for tracked power, convergence time, and ripple. This outcome reflects the fully deterministic nature of the simulation environment, which excludes noise, randomized initialization, or thermal perturbations. As a result, dispersion metrics such as standard deviation and variance are exactly zero. These zero-dispersion values are nevertheless included in the results tables to reinforce the consistency of the computational model. In contrast, physical implementations using real-world hardware are inherently subject to external influences such as sensor noise, quantization errors, and thermal instability, which would naturally introduce variability. These factors are expected to be addressed in future experimental validations.

Table 21 synthesizes the average performance of the methods in the three validation scenarios (1, 2, and 3), considering relative error, convergence time, average ripple, and conversion efficiency.

In summary, the P&O and InC methods show large errors and high ripple scenarios with local maxima, though they converge adequately in simple conditions. PSO and the GA demonstrate high robustness and are indicated for systems with multiple peaks; PSO balances precision with the fastest overall average speed (0.23 s), while the GA, also fast on average (0.31 s), proved to be the most agile in the most complex scenarios (2 and 3).

It is important to note that the use of the theoretical global maximum power point (GMPP) as a stopping criterion in PSO and the GA represents a controlled simulation artifact. While it facilitates precise benchmarking by standardizing convergence metrics, this approach is not transferable to real-world systems, where the true GMPP is unknown. Consequently, the results presented here may overestimate the effectiveness of global optimization algorithms under idealized conditions. In practical implementations, convergence would rely on alternative real-time criteria, such as plateau detection, derivative thresholds, or predefined iteration limits. This distinction must be kept in mind when interpreting the reported performance gains of metaheuristic algorithms and highlights the need for experimental validation using realistic termination strategies.

4. Comparative Analysis and Discussion

The comparative analysis of the four MPPT algorithms (P&O, InC, PSO, and GA) demonstrated significant performance differences as a function of the simulated scenarios. The efficacy of each technique is directly linked to the complexity of the P-V curve generated by the TEG module array and the distribution of thermal gradients.

Under ideal conditions (Scenario 1), featuring a P-V curve without multiple peaks, all methods located the GMPP with an error below 0.5%. PSO was the fastest (0.24 s), with the GA presenting similar performance but with a slightly longer convergence time (0.27 s). The traditional methods, P&O and InC, showed satisfactory stability and precision but with a higher power ripple due to their perturbative logic.

This robustness, however, was tested in Scenarios 2 and 3, which simulated conditions of thermal shading and asymmetric distribution. In these cases, the meta-heuristic algorithms (PSO and GA) excelled, proving capable of locating the GMPP with near-zero errors (≈0.01%), even with nearby local peaks. In contrast, the P&O and InC methods converged to local maxima, exhibiting errors exceeding 5%. This highlights their structural limitation: as “hill-climbing” algorithms, they are inherently trapped by the first local maximum power point (LMPP) they encounter, lacking the mechanism to scan the P-V curve to find the global maximum (GMPP). This finding aligns with the challenges identified in [

12,

13].

The analysis of dynamic performance (Scenario 6—Sinusoidal) revealed a critical distinction in tracking mechanics. While P&O exhibited a significantly slower convergence time (0.92 s) compared to PSO (0.67 s), this gap is attributed to the nature of the algorithms. P&O relies on a step-by-step perturbation approach; when the gradient shifts rapidly, the algorithm consumes multiple periods oscillating to determine the new derivative direction (dP/dV). In contrast, the PSO algorithm utilizes a re-initialization trigger (Equation (3)) that detects abrupt power changes and effectively “resets” the particles across the search space. This allows the swarm to jump to the new optimal region almost immediately, ensuring faster recovery in time-varying thermal environments.

The metrics for speed and stability also revealed a clear trade-off. The output ripple was consistently lower in the PSO and GA methods, especially in Scenario 3 (oscillation < 3%), reinforcing their suitability for stable power delivery. Considering the average convergence time (

Table 21), PSO proved to be the fastest overall (≈0.23 s), followed by the GA (≈0.31 s), InC (≈0.33 s), and P&O, which, although slower (≈0.39 s), maintained acceptable performance in simple scenarios (Scenario 1), and it consistently underperformed under multi-peak conditions. As seen in

Table 21, PSO and the GA maintained <1% error across complex scenarios, while P&O exceeded 5%.

It is noteworthy that while the GA had a slightly higher average time than PSO, it was the fastest in the most complex, multi-peak scenarios (0.06 s and 0.05 s), suggesting high efficiency in difficult search spaces. This agility reinforces the GA’s potential as a preferred algorithm in real-time embedded implementations with high gradient variability.

A critical design consideration raised in this comparative study is the trade-off between computational complexity and energy harvesting efficiency. It is acknowledged that metaheuristic algorithms (PSO and GA) impose a higher computational load regarding floating-point operations compared to the simple logic of P&O. However, in the context of modern low-power microcontrollers (e.g., ARM Cortex-M series), the energy consumption required to execute these additional cycles is in the order of milliwatts. Conversely, the energy “loss” caused by a classical algorithm getting trapped in a local maximum (as observed in Scenarios 2 and 3) can represent a significant portion of the total generated power (losses > 5%). Therefore, the net energy gain achieved by accurately tracking the GMPP using metaheuristics vastly outweighs the marginal increase in the microcontroller’s power consumption.

Finally, the scalability of the methods was validated in scenarios involving up to 196 TEG modules (Scenarios 9, 10, and 11). Metaheuristic algorithms preserved tracking precision and convergence efficiency even with the increased system size, demonstrating robustness in large-scale multistring architectures. Such scalability is fundamental for practical deployments in waste heat recovery and industrial energy harvesting systems.

In summary, the comparative results highlight that while classical methods are computationally efficient and easy to implement, they are insufficient in dynamic or complex environments. Metaheuristic strategies, although more resource-intensive, provide superior tracking performance, scalability, and resilience, key attributes for modern embedded applications that demand high reliability and adaptability.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper presented a comparative and critical analysis of four maximum power point tracking algorithms applied to thermoelectric systems based on thermoelectric generators, modeled and simulated in the MATLAB/Simulink environment. The evaluated methods (Perturb and Observe, Incremental Conductance, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Genetic Algorithm) were tested under eleven distinct thermal gradient scenarios, including conditions featuring multiple power peaks and gradient asymmetries. The simulation results revealed that:

Under ideal conditions (Scenario 1), all methods successfully located the global maximum power point (GMPP), achieving relative errors below 0.5% and conversion efficiencies around 97.3%. However, classical methods (P&O and InC) exhibited higher power ripple compared to PSO and the GA.

In multi-peak scenarios (Scenarios 2, 3, 10, 11), the metaheuristic algorithms clearly outperformed the classical ones. Both PSO and the GA achieved near-zero errors (≈0.01%) in locating the GMPP, while P&O and InC were trapped in local maxima, resulting in average errors exceeding 5%.

In terms of convergence time, the GA demonstrated the fastest response in complex thermal conditions (as low as 0.05 s in Scenario 3), while PSO presented the best overall average time (≈0.23 s), maintaining robust performance across all scenarios.

These considerations help contextualize the findings and establish the scope of applicability. It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of the simplified modeling approach adopted. The simulation treated TEGs as voltage sources dependent on temperature difference and internal resistance, explicitly disregarding dynamic thermal resistance, convection losses, and the Peltier effect (cooling due to current flow). While this abstraction is valid for comparing the logical tracking capabilities of the algorithms against instantaneous P-V curves, it does not capture the thermal settling times or the dynamic interaction between load current and temperature gradient found in physical prototypes.

The outcomes emphasize that advanced MPPT algorithms, particularly PSO and the GA, significantly enhance the energy harvesting capabilities of TEG systems in asymmetric environments. While these methods carry a slightly higher computational cost, the discussion highlighted that the net energy gain from accurate GMPP tracking vastly outweighs the marginal power consumption of modern low-power microcontrollers required to run them.

In summary, the objectives outlined in the Introduction were fully achieved. The study developed a complete modeling and digital implementation of four MPPT algorithms (P&O, InC, PSO, and GA) within a robust MATLAB/Simulink framework simulating a multistring thermoelectric generator array [

34]. Through eleven carefully designed thermal gradient scenarios, the research demonstrated the superior performance of metaheuristic methods in complex environments.

Finally, to extend this research and enhance the applicability of the results, several directions are recommended [

35]. Future works should focus on constructing physical prototypes of multistring TEG arrays to validate algorithmic performance under real-world thermal dynamics and incorporating detailed thermal-electrical coupling, including the Peltier effect and thermal lag, to refine simulation accuracy regarding transient responses. Furthermore, it is essential to investigate the impact of sensor noise and quantization errors in low-cost hardware, implementing robust digital filtering stages to prevent false peaks in metaheuristic search spaces. Additionally, a practical measurement of the energy consumption of the microcontroller running GA/PSO algorithms versus P&O is suggested to experimentally quantify the trade-off between computational load and energy harvesting gain.

Furthermore, it is recommended that future studies replace the theoretical power-based stopping criterion with more realistic and implementable strategies. In real-world applications, the global maximum power is not known a priori, and practical convergence must be based on observable metrics such as steady-state detection, minimal power variation, or fixed iteration limits. Adopting these practical criteria in experimental setups will ensure a more accurate assessment of the robustness and efficiency of metaheuristic MPPT algorithms and avoid any artificial advantage resulting from simulation-specific assumptions.