Governance Quality and the Green Transition: Integrating Econometric and Machine Learning Evidence on Renewable Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Direct Effect of Governance Quality of Renewable Energy Efficiency

2.2. Transmission Mechanisms (Renewable Energy Investment, Green Policies, and Green Technology)

3. Methods

3.1. Variable Measurement

| Variable | Measurement | Source | References |

| Dependent variable | |||

| Renewable energy efficiency (REE) | Measured using MPI-DEA with inputs (e.g., labor, capital, energy) and outputs (e.g., renewable electricity generation) | Own calculation based on World Bank’s, Energy Institute—Statistical Review of World Energy data (2024) | [39,40,41,42,43] |

| Independent Variable | |||

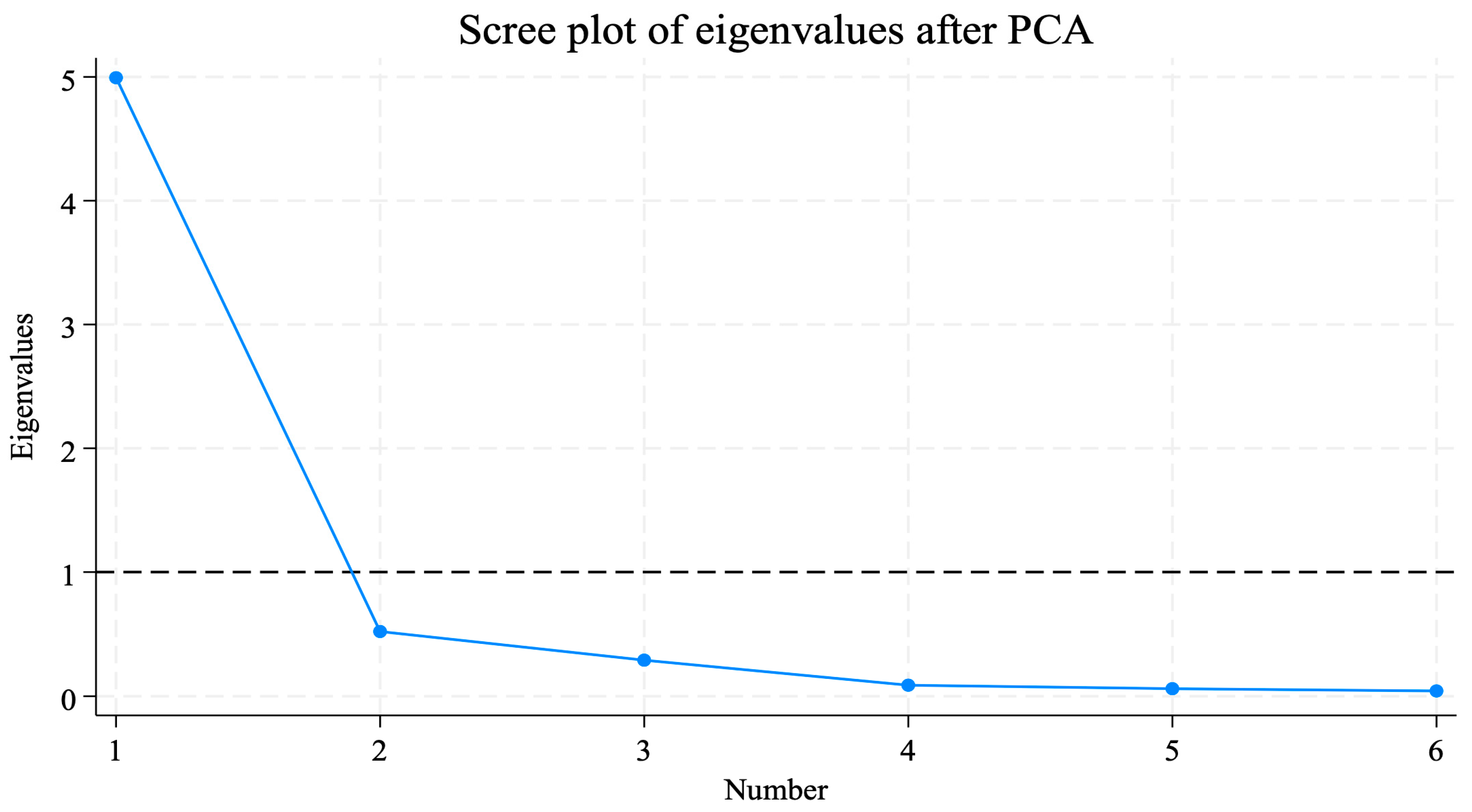

| Governance Quality Index (GQI) | PCA composite index based on control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, and government effectiveness | World Governance Indicators | [44,45,46] |

| Control variables | |||

| GDP growth (rGDP) | Annual real GDP growth rate (% change from previous year) | World Development Indicators | [6,27,49,52,54,55,56] |

| FDI energy sector (FDIE) | Inward FDI flows to energy sector (% of energy use) | OECD | |

| Human Capital Index (HCI) | Human Capital Index score | World Development Indicators | |

| Government expenditure (GE) | Government final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) | World Development Indicators | |

| Electricity (renewable) (EREN) | Renewable electricity output (% of total electricity production) | Energy Institute—Statistical Review of World Energy (2024) | |

| GDP per capital (GDPPC) | GDP per capita (constant 2010 USD) | World Development Indicators | |

| Urbanization (URB) | Urban population as % of total population | World Development Indicators | |

| Mechanism Variables | |||

| Renewable policy (RP) | Index score or dummy (1 = policy exists; 0 = none | International Energy Agency (IEA) | [46,47,48] |

| Renewable investment (RE) | Annual renewable energy investment (USD millions) | International Energy Agency (IEA) | [49,50] |

| Green patent technology (GT) | Number of patents filed in renewable/green technologies (per year or per million population) | International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) | [51,52,53] |

3.2. Model Estimations

3.3. Machine-Learning Counterfactual Simulations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Empirical Results

4.1.1. Addressing Autocorrelation and Multicollinearity Issues

4.1.2. Benchmark Regression Analysis

4.1.3. Robustness Checks and Addressing Endogeneity

4.1.4. Transmission Mechanisms Analysis

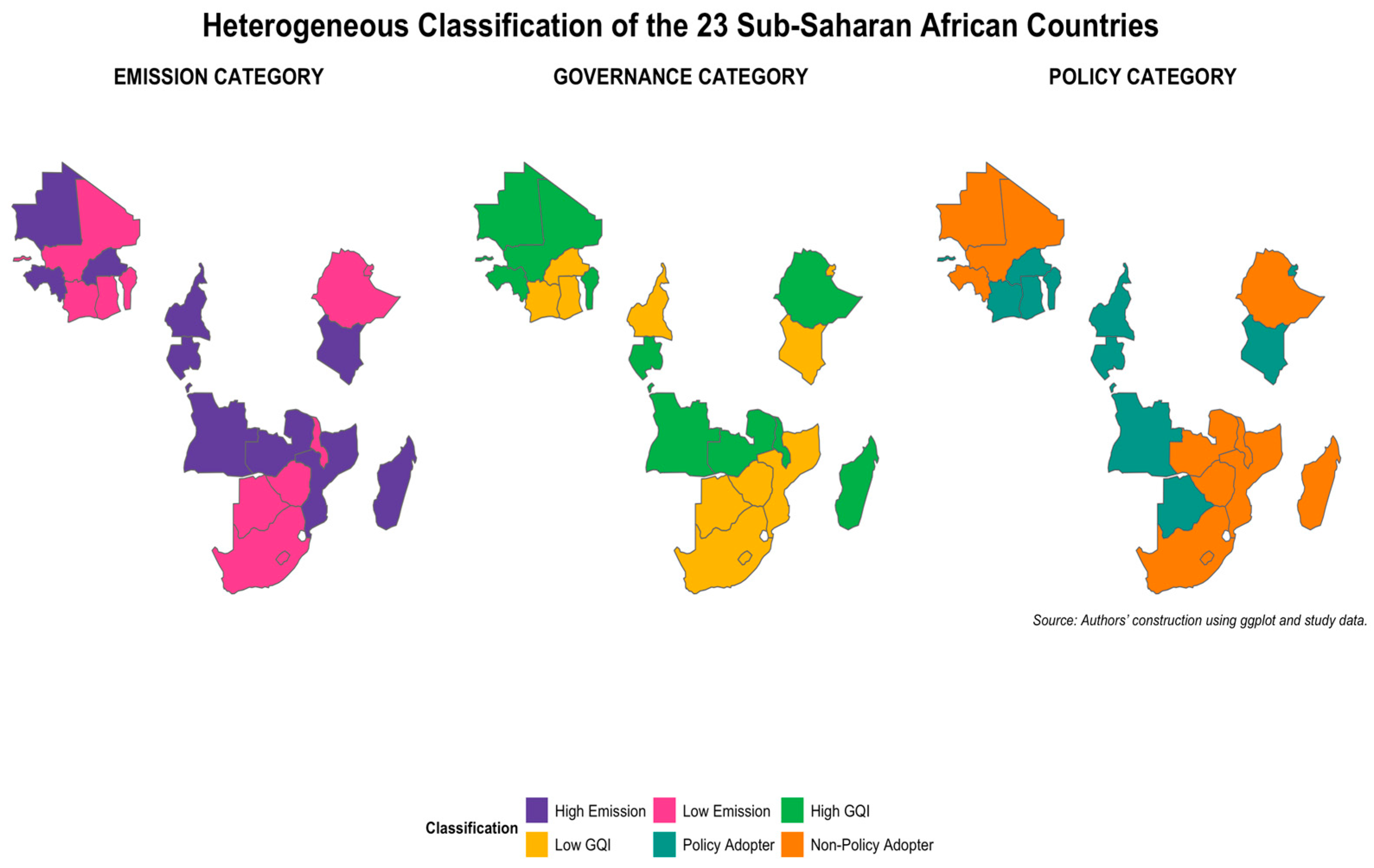

4.1.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.2. Machine-Learning Validation and Counterfactual Simulations

4.2.1. Governance Quality and Renewable-Energy Efficiency (DML Validation)

4.2.2. Average Treatment Effects of Policy Levers

4.2.3. Heterogeneous Effects and Country-Level Targeting

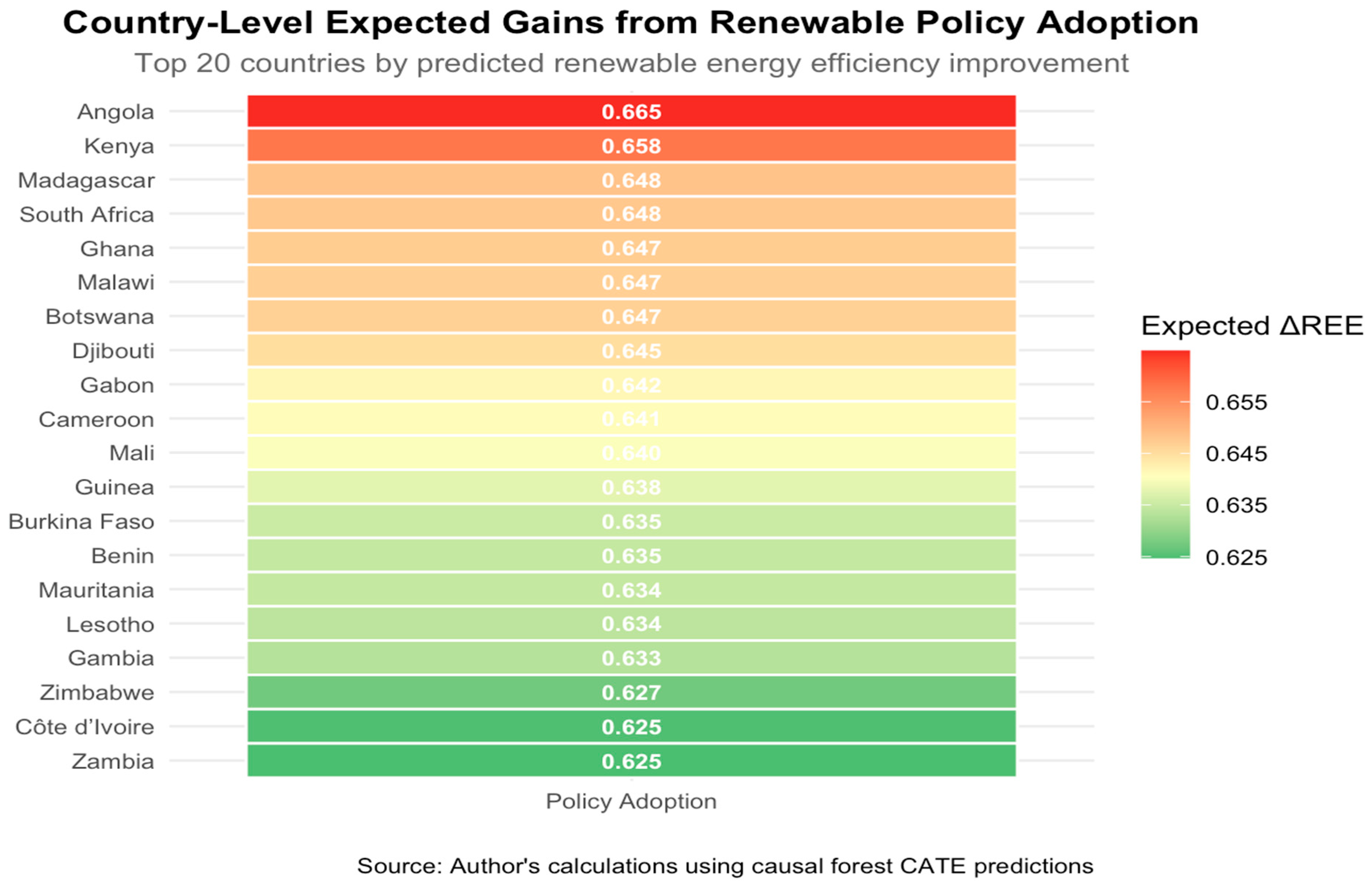

4.2.4. Country-Level Expected Gains from Renewable-Policy Adoption

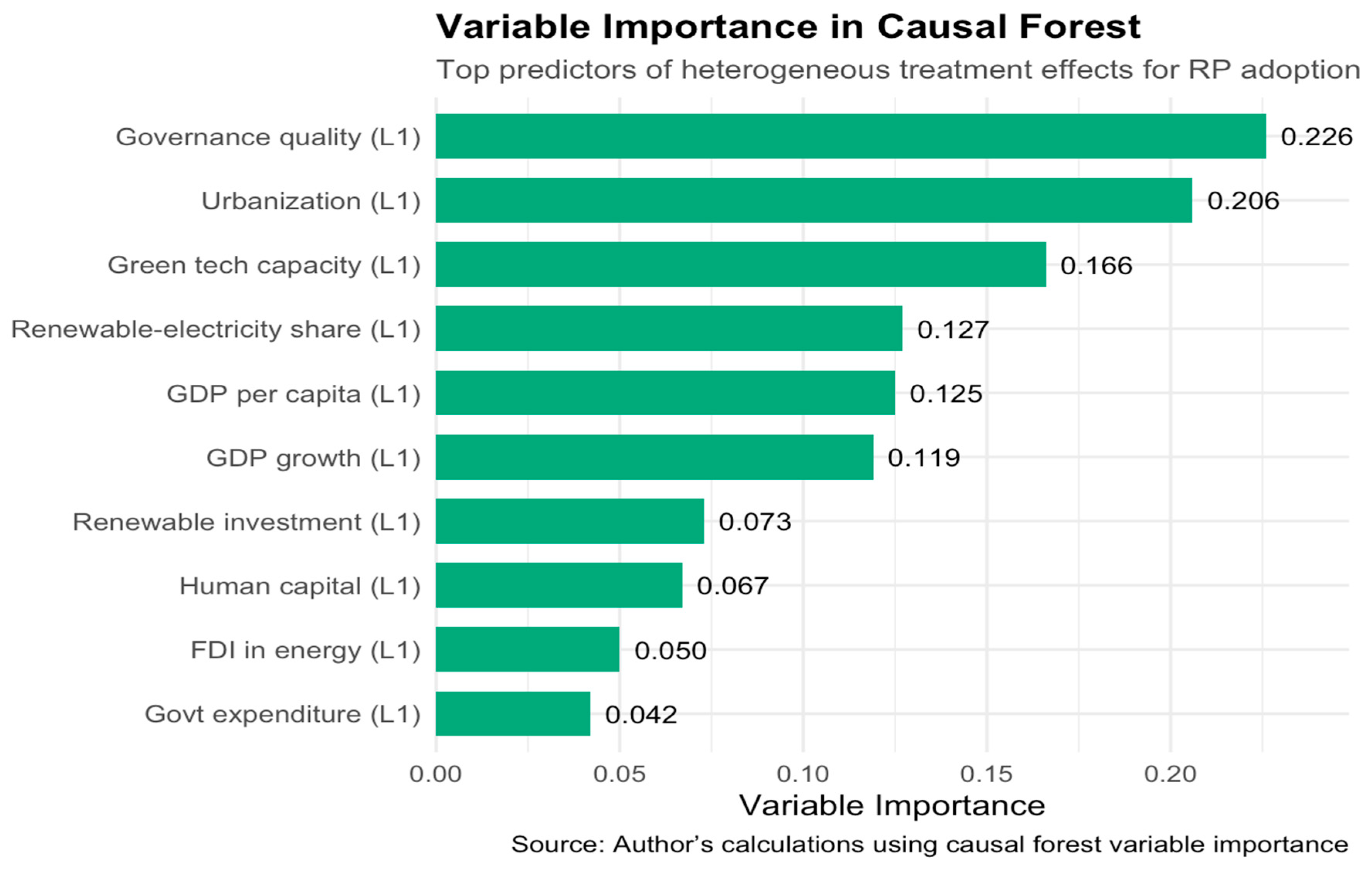

4.2.5. Determinants of Heterogeneous Policy Impacts

4.2.6. Treatment Prevalence and Diagnostic Robustness

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Recommendations

- i.

- Policy-Adopter and High-GQI countries stand to benefit most from scaling green technologies and deepening policy coherence. Here, emphasis should be placed on enhancing technological readiness, improving monitoring systems, and fostering innovation ecosystems that leverage existing strengths.

- ii.

- High-emission countries should prioritize governance reforms that directly address inefficiencies in the electricity sector, reduce regulatory bottlenecks, and create incentives for rapid clean-energy deployment.

- iii.

- Low-GQI and institutionally fragile countries require foundational governance strengthening, including improved contract enforcement, depoliticized regulatory processes, and targeted capacity-building to ensure that renewable-energy policies translate into actual performance gains. In these contexts, sequencing reforms, starting with transparency, basic regulatory stabilization, and small-scale technology pilots, may yield the highest marginal returns.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Countries

- -

- Policy Adopters: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya.

- -

- Non-Policy Adopters: Ethiopia, Guinea, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

- -

- High-GQI SSA Countries: Angola, Benin, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Guinea, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Zambia.

- -

- Low-GQI SSA Countries: Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe.

- -

- High-Emission Countries (HEC): Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Zambia.

- -

- Low-Emission Countries (LEC): Benin, Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, South Africa, Zimbabwe.

References

- Charamba, A.N.; Kumba, H.; Makepa, D.C. Assessing the Opportunities and Obstacles of Africa’s Shift from Fossil Fuels to Renewable Sources in the Southern Region. Clean Energy 2025, 9, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterl, S.; Fadly, D.; Liersch, S.; Koch, H.; Thiery, W. Linking Solar and Wind Power in Eastern Africa with Operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, L.; Moran, J.; Manqele, S. Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme Review 2016: A Critique of Process of Implementation of Socio-Economic Benefits Including Job Creation; Alternative Information Development Centre: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahamoud Abdi, A.; Murayama, T.; Nishikizawa, S.; Suwanteep, K. Social Acceptance and Associated Risks of Geothermal Energy Development in East Africa: Perspectives from Geothermal Energy Developers. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klagge, B.; Greiner, C.; Greven, D.; Nweke-Eze, C. Cross-Scale Linkages of Centralized Electricity Generation: Geothermal Development and Investor–Community Relations in Kenya. Politics Gov. 2020, 8, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Nagaj, R.; Wolniak, R.; Bałaga, D.; Žuromskaitė, B.; Grebski, W.W. Renewable Energy Share in European Industry: Analysis and Extrapolation of Trends in EU Countries. Energies 2024, 17, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjærseth, J.B. Towards a European Green Deal: The Evolution of EU Climate and Energy Policy Mixes. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2021, 21, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, R.; Plazas-Niño, F.; Cannone, C.; Yeganyan, R.; Howells, M.; Luscombe, H. Long-Term Energy System Modelling for a Clean Energy Transition and Improved Energy Security in Botswana’s Energy Sector Using the Open-Source Energy Modelling System. Climate 2024, 12, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Onatunji, O.G. Towards Achieving Inclusive Energy in SSA: The Role of Financial Inclusion and Governance Quality. Energy 2024, 311, 133310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, T.A.M.; Kambaye, E.N.; Asongu, S.A.; Alinsato, A.S.; Berhe, M.W.; Dossou, K.P. Foreign Direct Investment and Renewable Energy Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does Governance Quality Matter? Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrkasten, S.; Roehrkasten, S. Global Governance on Renewable Energy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 73–116. [Google Scholar]

- Abegaz, M.B.; Debela, K.L.; Hundie, R.M. The Effect of Governance on Entrepreneurship: From All Income Economies Perspective. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Nghiem, S. Linking Governance with Environmental Quality: A Global Perspective. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J. New Insights into How Green Innovation, Renewable Energy, and Institutional Quality Shape Environmental Sustainability in Emerging Economies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1525281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy Justice: Conceptual Insights and Practical Applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Cai, J.; Davenport, J. Legal Systems, National Governance and Renewable Energy Investment: Evidence from Around the World. Br. J. Manag. 2021, 32, 579–610. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Elmagrhi, M.H.; Ntim, C.G.; Wu, Y. Environmental Performance, Sustainability, Governance and Financial Performance: Evidence from Heavily Polluting Industries in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2313–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. Institutions and Their Consequences for Economic Performance. In The Limits of Rationality; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 383–401. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.; Khan, N.; Omri, A. Environmental Policy Stringency, ICT, and Technological Innovation for Achieving Sustainable Development: Assessing the Importance of Governance and Infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A.; Dzwigol, H.; Dzwigol-Barosz, M.; Pavlyk, V.; Barosz, P. The Impact of the Government Policy on the Energy Efficient Gap: Evidence from Ukraine. Energies 2021, 14, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Edziah, B.K.; Sun, C.; Kporsu, A.K. Institutional Quality, Green Innovation and Energy Efficiency. Energy Policy 2019, 135, 111002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. Review of Policies and Measures for Energy Efficiency in Industry Sector. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6532–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziabina, Y.; Navickas, V. Innovations in Energy Efficiency Management: Role of Public Governance. Mark. I Menedžment Innovacij 2022, 13, 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bellakhal, R.; Kheder, S.B.; Haffoudhi, H. Governance and Renewable Energy Investment in MENA Countries: How Does Trade Matter? Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtaruzzaman, M. The Link Between Good Governance, Economic Development and Renewable Energy Investment: Evidence from Upper Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Empir. Econ. 2022, 1, 2250005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Kor, S. Nexus Between Green Investment, Fiscal Policy, Environmental Tax, Energy Price, Natural Resources, and Clean Energy—A Step Towards Sustainable Development by Fostering Clean Energy Inclusion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Zhou, K.; Muhammad, F.; Khan, D.; Khan, A.; Ali, N.; Akhtar, R. Renewable Energy Investment and Governance in Countries along the Belt & Road Initiative: Does Trade Openness Matter? Renew. Energy 2021, 180, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N.J.; Adams, V.M.; Byrne, J.A. Moving Beyond the Plan: Exploring Opportunities to Accelerate Implementation of Municipal Climate Change Adaptation Policies and Plans. Environ. Policy Gov. 2025, 35, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; García, C. Environmentalism in the EU-28 Context: The Impact of Governance Quality on Environmental Energy Efficiency. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 37012–37025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; Dentener, F.; Gielen, D.; Grubler, A.; Jewell, J.; Klimont, Z.; Morgan, G. Energy Pathways for Sustainable Development. In Global Energy Assessment: Toward a Sustainable Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 1205–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoldi, P.; Huld, T. Tradable Certificates for Renewable Electricity and Energy Savings. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Khan, A.R.; Aslam, S.; Rasheed, A.K.; Mohsin, M. Financial Impact of Energy Efficiency and Energy Policies Aimed at Power Sector Reforms: Mediating Role of Financing in the Power Sector. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 18891–18904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Xinyan, X.; Siddik, A.B.; Islam, M.E. Unlocking Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance through Energy Efficiency and Green Tax: SEM-ANN Approach. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Saydaliev, H.B.; Ma, X. Does Green Finance Investment and Technological Innovation Improve Renewable Energy Efficiency and Sustainable Development Goals? Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhosseini, S.; Heshmati, A.; Altmann, J. A Review of Renewable Energy Supply and Energy Efficiency Technologies; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Tanveer, A.; Fu, X.; Gu, Y.; Irfan, M. Modeling the Influence of Critical Factors on the Adoption of Green Energy Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, G.; Sun, H.; Ali, I.; Pasha, A.A.; Khan, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Shah, Q. Influence of Green Technology, Green Energy Consumption, Energy Efficiency, Trade, Economic Development and FDI on Climate Change in South Asia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Hameed, J.; Alqhtani, H.A.; Fatemah, A.; Dar, A.A. Intrinsic Role of Green Technologies and Renewable Energy: A Pathway to Mitigate Climate Change in China. Geol. J. 2025, 60, 2808–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xia, M.; Wang, P.; Xu, J. Renewable Energy Output, Energy Efficiency and Cleaner Energy: Evidence from Non-parametric Approach for Emerging Seven Economies. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökgöz, F.; Güvercin, M.T. Energy Security and Renewable Energy Efficiency in EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, F.A.; Wang, J.; Cobbinah, B.B.; Makwetta, J.J.; Chen, J. The Drivers of Energy Efficiency Improvement Among Nine Selected West African Countries: A Two-Stage DEA Methodology. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amowine, N.; Balezentis, T.; Zhou, Z.; Streimikiene, D. Transitions Towards Green Productivity in Africa: Do Sovereign Debt Vulnerability, Eco-Entrepreneurship, and Institutional Quality Matter? Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 3405–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amowine, N.; Ma, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Asunka, B.A.; Amowine, J. Energy Efficiency Improvement Assessment in Africa: An Integrated Dynamic DEA Approach. Energies 2019, 12, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeswayo, P.S.; Handoyo, S.; Abdul Hasyir, D. Investigating the Relationship Between Public Governance and the Corruption Perception Index. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2342513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S. Worldwide Governance Indicators: Cross Country Data Set 2012–2022. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, M.; Hellquist, A. Trust and Collaborative Governance. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Feng, S. Does Renewable Energy Policy Work? Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 135, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Feiock, R.C. Renewable Energy Politics: Policy Typologies, Policy Tools, and State Deployment of Renewables. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, X. Investment in Renewable Energy Resources, Sustainable Financial Inclusion and Energy Efficiency: A Case of US Economy. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Qin, C.; Ding, L.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Vătavu, S. Can Green Bond Improve the Investment Efficiency of Renewable Energy? Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xue, Q.; Qin, J. Environmental Information Disclosure and Green Technology Innovation: Empirical Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121453. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.F.; Niu, P.; Wang, J.Z.; Liu, J. Capital Market Liberalization and Green Innovation for Sustainability: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatraro, F.; Scandura, A. Academic Inventors and the Antecedents of Green Technologies: A Regional Analysis of Italian Patent Data. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 156, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Environmental Governance and Regional Green Development: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yuan, Y. Different Types of Environmental Regulations and Heterogeneous Influence on Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector: Evidence from Chinese Provincial Data. Energy Policy 2020, 145, 111747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Li, Q.; Du, K. How Does Environmental Regulation Promote Technological Innovations in the Industrial Sector? Evidence from Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, M.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Unraveling the Determinants of Traffic Incident Duration: A Causal Investigation Using the Framework of Causal Forests with Debiased Machine Learning. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 208, 107806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaus, M.C. Double Machine Learning-Based Programme Evaluation Under Unconfoundedness. Econom. J. 2022, 25, 602–627. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Renewable Energy Efficiency (REE) | 414 | 0.91 | 0.37 | 0.03 | 1.31 |

| Governance Quality Index (GQI) | 414 | −0.53 | 1.03 | −4.2 | 3.30 |

| Renewable Investment (RI) | 414 | 13.44 | 2.64 | 0 | 8.32 |

| Renewable Policy (RP) | 414 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 |

| Green Technology (GT) | 414 | 82.60 | 8.03 | 0 | 92.05 |

| GDP Growth (rGDP) | 414 | 4.27 | 1.26 | 0.041 | 5.877 |

| FDI Energy Sector (FDIE) | 414 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.1 | 2.79 |

| Human Capital Index (HCI) | 414 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.79 |

| Government Expenditure (GE) | 414 | 23.58 | 6.29 | 12.05 | 37.37 |

| Electricity (Renewable) (EREN) | 414 | 34.18 | 17.39 | 2.08 | 95.06 |

| GDP per capita (GDPPC) | 414 | 3482.08 | 1842.45 | 481.20 | 9633.66 |

| Urbanization (URB) | 414 | 35.89 | 11.92 | 14.72 | 68.35 |

| ||||||||||||

| Multicollinearity and Autocorrelation | ||||||||||||

| VIF | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 4.78 | 1.77 | 1.09 | 2.19 | 3.84 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 1.62 | |

| 1/VIF | 0.918 | 0.965 | 0.969 | 0.209 | 0.565 | 0.915 | 0.456 | 0.260 | 0.968 | 0.758 | 0.617 | |

| Durbin-Watson | 2.53 | |||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | REE | REE | REE | REE |

| OLS | Fixed Effect | |||

| Governance quality | 0.02 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.31 *** | 0.30 ** |

| (3.11) | (2.35) | (4.12) | (2.34) | |

| GDP growth | 0.01 * | 0.01 *** | ||

| (1.88) | (2.84) | |||

| FDI (energy sector) | 0.03 *** | 0.11 ** | ||

| (4.36) | (2.46) | |||

| HCI | 0.04 *** | 0.05 *** | ||

| (2.71) | (4.29) | |||

| Government expenditure | 0.21 *** | 0.04 ** | ||

| (4.12) | (2.08) | |||

| Electricity (renewable) | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| (0.26) | (0.08) | |||

| GDP per capita | 0.09 *** | 0.80 *** | ||

| (4.78) | (4.40) | |||

| Urbanization | 0.043 *** | 0.10 *** | ||

| (2.96) | (2.91) | |||

| Constant | 1.00 *** | 1.61 *** | 1.00 *** | 0.60 *** |

| (16.29) | (9.83) | (8.19) | (14.50) | |

| N | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 |

| R-squared | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| Countries | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Country FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | REE | REE | REE | REE | REE |

| Two-step GMM | GEE Model | GLS Model | PCSE | ||

| L.REE | 0.32 ** | 0.35 ** | |||

| (2.19) | (2.09) | ||||

| Governance quality | 0.01 *** | 0.04 ** | 1.25 *** | 2.13 *** | 1.12 *** |

| (3.94) | (2.03) | (2.97) | (3.43) | (3.75) | |

| Constant | 1.32 *** | 0.33 ** | −2.91 *** | 3.86 *** | 0.16 *** |

| (9.11) | (2.56) | (−4.53) | (3.07) | (4.14) | |

| N | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Countries | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| R-squared | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.49 |

| AR (2) | −1.48 (0.14) | −1.04 (0.29) | |||

| Sargan test | 507.92 (0.14) | 490.10 (0.38) | |||

| Hansen test | 26.71 (0.20) | 25.80 (0.48) | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | GTFPCH | GTFPCH | GTECH | GTECH |

| Green Technology Efficiency | Green Technological Progress Efficiency | |||

| GQI | 0.09 *** | 0.04 ** | 0.10 *** | 0.04 *** |

| (6.22) | (2.25) | (7.92) | (4.44) | |

| Constant | 1.04 *** | −8.75 * | 1.01 *** | 3.16 *** |

| (4.43) | (−1.88) | (6.38) | (8.23) | |

| N | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 |

| R-squared | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| Countries | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | Path a | Path b, c’ | Path a | Path b, c’ | Path a | Path b, c’ |

| Renewable Investment | Green Policy | Green Technology | ||||

| Governance quality | 0.25 ** | 0.03 *** | 1.10 *** | 0.03 *** | 9.81 *** | 0.02 *** |

| (2.35) | (3.54) | (3.06) | (4.68) | (3.77) | (4.46) | |

| RI | 0.04 *** | |||||

| (4.61) | ||||||

| RP | 0.03 *** | |||||

| (2.92) | ||||||

| GT | 0.01 *** | |||||

| (5.45) | ||||||

| Constant | 12.57 *** | 0.83 * | 16.38 *** | 0.95 ** | −5.49 ** | 0.64 *** |

| (8.46) | (1.74) | (4.87) | (2.26) | (−2.49) | (3.77) | |

| N | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 | 414 |

| R-squared | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 0.25 |

| Countries | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | REE Policy Adopters | REE Non-Policy Adopters | REE High-Emission | REE Low-Emission | REE High-GQI | REE Low-GQI |

| GQI | 1.48 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.01 ** | 0.66 *** | 0.02 ** |

| (3.48) | (3.19) | (4.14) | (2.12) | (3.03) | (2.53) | |

| Constant | −18.73 ** | 3.41 | −8.19 | −1.09 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| (−2.37) | (0.47) | (−1.04) | (−0.14) | (−0.07) | (0.19) | |

| Wald Test | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| N | 198 | 216 | 216 | 198 | 198 | 216 |

| R-squared | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.29 |

| Countries | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nyabvudzi, J.; Xu, H.; Sarpong, F.A. Governance Quality and the Green Transition: Integrating Econometric and Machine Learning Evidence on Renewable Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energies 2025, 18, 6618. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246618

Nyabvudzi J, Xu H, Sarpong FA. Governance Quality and the Green Transition: Integrating Econometric and Machine Learning Evidence on Renewable Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6618. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246618

Chicago/Turabian StyleNyabvudzi, Joseph, Hongyi Xu, and Francis Atta Sarpong. 2025. "Governance Quality and the Green Transition: Integrating Econometric and Machine Learning Evidence on Renewable Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa" Energies 18, no. 24: 6618. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246618

APA StyleNyabvudzi, J., Xu, H., & Sarpong, F. A. (2025). Governance Quality and the Green Transition: Integrating Econometric and Machine Learning Evidence on Renewable Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energies, 18(24), 6618. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246618