Abstract

Public transport still uses vehicles powered by fossil fuels. Replacing the fleet with zero-emission vehicles will take many years. During this period, it is still necessary to carry out work aimed at reducing energy consumption and thus the emission of toxic substances into the atmosphere. An important part of this work is the study of the relationship between energy demand of buses with different power plants and urban traffic conditions. These conditions include traffic intensity, average and maximum speeds, and number of stops. The VSP (Vehicle-Specific Power) model is useful in research on this relationship. In this article, such research was carried out using data from public bus monitoring and data provided by the city authorities of Rzeszów. In the first stage, a VSP model was created and tuned for three buses with different power plants operating on selected routes. Then, as a result of a large number of simulation processes, the impact of the average speed on the energy demand was determined. The results of the conducted research can be used in the modernization or planning of public transport networks and the modification of road infrastructure. All these activities should contribute to reducing energy consumption and environmental pollution.

1. Introduction

The transport sector consumes large amounts of energy contained in nonrenewable fossil fuels. In addition, it is a source of emissions of many harmful substances into the atmosphere [1]. However, without efficient transport, the economy could not function properly and there would be great difficulties in the functioning of cities. In recent years, considerable emphasis has been placed on environmental protection and a reduction in the consumption of fossil fuels [2]. All these activities are taking place as part of the work aimed at developing sustainable transport. There are a considerable number of publications covering the above issues in a comprehensive way [3,4,5,6] and in more detail [7,8]. In the case of cities and urban areas, the operation of transport also contributes to reducing quality of life through excessive noise and congestion [7]. For this reason, public transport and bicycles are preferred in cities [9]. Compared to individual transport, public transport is characterized by a lower energy consumption per passenger [10,11]. It also reduces air pollution [12], traffic, and congestion [13,14]. For these reasons, public transport is the preferred form of transport in the policy of most city authorities [7]. The most desirable form of public transport would be zero-emission transport that does not use fossil fuels. Most countries and cities are moving toward implementing such a solution [15]. This solution requires significant financial investments, as well as solving many technical problems related to energy storage. Currently, the vast majority of public transport is carried out by vehicles with classic drive systems using energy from fossil fuels [16,17]. A complete shift away from this form of transport is a matter of at least a dozen or more years. However, this does not mean that during this transition period all work aimed at reducing energy consumption and environmental pollution by vehicles using classic drive systems will be abandoned. A number of actions are being taken to improve public transport and reduce its harmfulness [18,19,20,21]. These activities may cover various areas related to the operation of public transport. The simplest activity in this area is driver training [22] to reduce fuel consumption. Changes in the city’s transport infrastructure are much more difficult and capital intensive [23]. These changes include the use of transit priority at intersections for city buses and the smoothing of bus traffic through the use of bus lanes [24,25,26,27,28]. Harmfulness of public transport may be reduced by improving its management by minimizing energy consumption and thus reducing environmental pollution [29]. In the case of activities aimed at this improvement, it is necessary to recognize the operating parameters of the bus and the external traffic conditions. Traffic conditions can be recognized by an external vehicle traffic monitoring system. For the operating parameters, there are two methods of recognition. The first involves equipping the vehicle with a set of measurement sensors monitoring the vehicle’s condition and operating parameters during movement, such as specific fuel consumption, engine speed and torque, and vehicle speed. The second way is simpler. It assumes the use of data from an external bus speed and position monitoring system and the VSP (Vehicle-Specific Power) mathematical model. The VSP model makes it possible to determine the energy and fuel consumption of a vehicle during a given movement. It also allows to determine the emissions of harmful substances into the atmosphere [30,31]. In the work [30], the VSP methodology was used to assess the environmental characteristics of transport at roundabouts for their different geometric variations. But the focus of this study is on road geometry, not on a systematic analysis of transport routes. The authors [31] describe in detail the stages of using the VSP method. The conclusions from this study highlight the importance of speed regulation and driver behavior modification to improve vehicle operation efficiency; however, this work does not compare the efficiency of vehicles with different powertrains. It also does not take into account passenger load, which is an important parameter for public transport. The description and use of the VSP model can be found in the literature [10,32,33,34,35]. In the paper [35], due to the small amount of data, covering only 17 trips from one November day in 2019, and the low accuracy of the GPS (Global Positioning System) measurement system, the results obtained are only informative. The work itself is preliminary research to test the capabilities of the VSP model. Upgrading and expanding the monitoring system has made it possible to conduct new comprehensive research covering multiple bus lines. This article contains such research. This study investigates the impact of traffic conditions on public bus fuel consumption. The data used in this research came from three different buses that made more than 1000 trips in total during one month. The object of this research in 2023 was again public transport [7,36,37] in the city of Rzeszow. The parameters of the new measurement system are presented in the paper [36].

Based on the bus speed, passenger load, and fuel consumption data, the VSP models associated with the studied buses were first calibrated and verified. Next, using verified models, computer simulations were carried out to determine the energy demand under various traffic conditions. Based on the results obtained, the impact of changing traffic conditions on energy consumption was determined. The data collected and the results obtained can provide useful guidance for the implementation of work aimed at improving the operation of public transport in the city and reducing its energy consumption and harmfulness to the environment.

The work consists of the following parts:

- Section 1 is an introduction that presents basic information about the specificity of urban transport and its impact on the environment.

- Section 2 characterizes the operating conditions of public transport in the city using the selected route as an example and presents information on the resistance of bus motion and energy demand, the principles of VSP (Vehicle-Specific Power) model, and the process of estimating VSP model parameters for three selected buses.

- Section 3 contains a description of simulations with real traffic parameters conducted for three different buses running on different routes and on the same route for all vehicles. This chapter includes selected results of the simulations and provides an analysis of the results.

- Section 4 is a summary of the article.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Operating Conditions of Urban Buses

City bus operating conditions are highly unfavorable with respect to energy demand. The movement is not uniform. Numerous processes of acceleration and braking occur, which in many cases end with the stop. In the case of the ICE (internal combustion engine) bus, the bus engine still runs and consumes fuel during the stop. Frequent stops result in an increase in fuel consumption along the set route and thus in an increase in harmful emissions into the atmosphere.

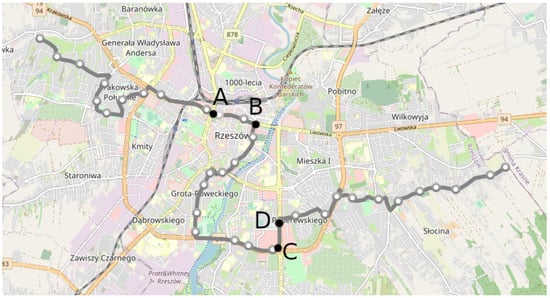

Figure 1 shows selected bus route no. 6 in Rzeszów. Two fragments, A–B and C–D, are marked on this route. Route fragment A–B is located on the main street that runs through the city center. In this fragment there are 2 lanes in both directions. There is also a bus lane in both directions that is active only during morning and afternoon peak. Outside the peak hours it is a normal lane. There are 4 traffic lights in this fragment. Fragment C–D is located on a street that runs outside the city center. In this fragment there are 2 lanes in the C–D direction and 3 lanes in D-C direction. There are 2 traffic lights in this fragment.

Figure 1.

Bus route no. 6 with stops and the traffic volume measurement fragments A–B and C–D marked.

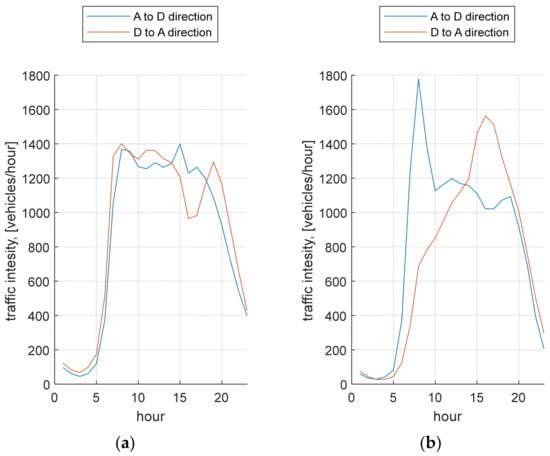

The hourly traffic volume during the day on the selected route fragments is shown in Figure 2. The traffic volume was measured by induction loops and cameras on the intersections. In the case of the A–B fragment, the direction of traffic does not matter much. In both directions there is practically similar traffic volume depending only on the time of day. In the case of the traffic volume on fragment C–D, the direction of traffic is important. In the morning hours in the D direction, the traffic intensity reaches its peak. In direction A, the peak traffic volume occurs in the afternoon. On the selected fragment C–D at the same time of day, depending on the direction of traffic, the vehicle may encounter extremely different traffic conditions.

Figure 2.

Hourly traffic of vehicles at the chosen sections: (a) Section A–B; (b) Section C–D.

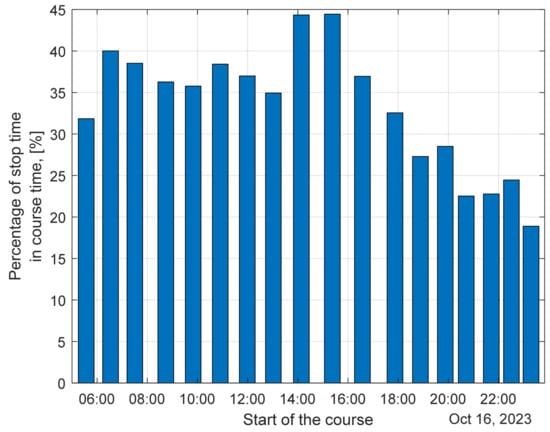

Depending on the time of day and external traffic conditions, the speed profile of the vehicle and the total time of stops during the trip change. These stops result from stops at bus stops and from unplanned stops caused by external traffic conditions. Figure 3 shows the share of stop times in relation to the total duration of the trip. It is based on data for one day of operation of a bus operating on route no. 6. A more detailed analysis can be found in the paper [38]. In the case of peak hours, the sum of stop times reaches approximately 44% of the total duration of the trip.

Figure 3.

Share of total stop times in relation to the trip duration depending on the trip start time.

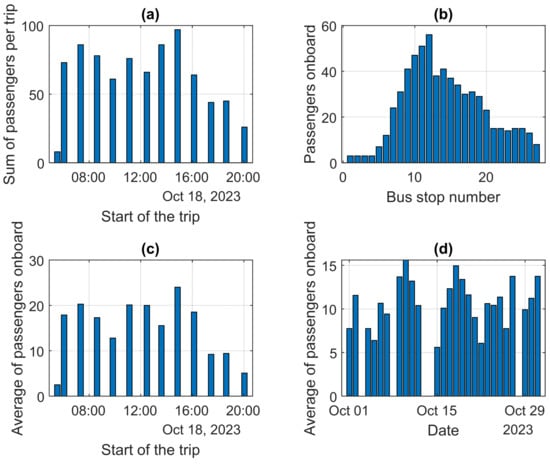

The time of day also affects the number of passengers carried by the bus. To visualize this, Figure 4 was created. Figure 4a shows the sum of passengers on trip carried by the selected 12 m long CNG (Compressed Natural Gas)-powered bus on 18 October 2023 depending on the trip start time. One day was chosen to show the effect of time of the day on the total number of passengers. During the execution of a given trip, the number of passengers on board between bus stops is constantly changing. Figure 4b shows how the number of passengers carried between bus stops changed for one peak-hours trip. This figure was developed for the 15:00 trip on 18 October 2023. This trip was chosen as an example, because during this trip, the bus carried the highest number of passengers during the day, as shown in Figure 4a. To compare the passenger load of each trip on a particular day, the average number of passengers on board the bus was determined. These values were determined from the transport work, defined by the number of passenger-kilometers performed on a given trip or on the entire working day. Transport work is defined as a number of passengers multiplied by distance traveled. Then, this work was divided by the number of kilometers traveled on a given trip or on a given day. Figure 4c shows the average number of bus passengers on board the bus on a selected day in October. Figure 4d shows the average number of bus passengers on board the bus on each day in October 2023.

Figure 4.

Passenger transport by the selected CNG bus: (a) The sum of passengers carried on each trip on 18 October; (b) The number of passengers between bus stops for the 15:00 trip on 18 October; (c) The average number of passengers on board the bus on 18 October; (d) The average number of passengers on board the bus on each day in October.

Figure 4a,c show that the early morning and evening trips have the smallest passenger volumes and the lowest average number of bus passengers between bus stops. The highest number of bus passengers between bus stops on 18 October was 56 passengers on the 15:00 trip.

2.2. Methodology of Determining Energy Consumption

As the ICE (internal combustion engine) bus moves, the torque provided by the engine after transformation in the drive train is used to overcome the external resistance to movement [35]. When stationary, the vehicle’s engine powers auxiliary systems—such as the air compressor and alternator—that are essential for the bus’s operational functionality.

The bus’s total fuel-based energy requirement is expressed by the following relation:

where ET is total energy, MJ; E1 denotes the energy required to counteract external resistive force, MJ; E2 is energy consumed when the bus is stationary, MJ.

ET = E1 + E2

Direct computation of fuel consumption under the variable traffic conditions specified in Equation (1) is analytically demanding. Engine energy efficiency is non-uniform across operating conditions [39]. It varies with operating parameters, including engine torque Te and shaft angular velocity ω. The ranges of Te and ω during bus operation are extensive [40]. Engine energy efficiency exhibits substantial variability [41]. Therefore, with this method, it is necessary to know the exact external characteristics of the engine.

Public transport companies have many different types of buses that date from different years of production. It is virtually impossible to obtain accurate external characteristics of internal combustion engines for each bus in operation. In addition, the external characteristics of the engine determined under laboratory conditions may differ from the actual characteristics. Under such conditions, a method using the VSP (Vehicle-Specific Power) model is useful for determining energy consumption [32,33,34,35,40]. This method is also applicable for determining environmental emissions [34,42,43,44,45]. The method involves determining the VSP index, which takes into account the aerodynamic drag, inertia, tire rolling resistance, and road slope. The VSP is generally defined as the power per unit vehicle weight and is a function of the vehicle speed, acceleration, and road grade. The VSP index can be determined using Equation (2) [35]:

where is ambient air density, kg/m3; S is frontal area of the vehicle, m2; cx is air drag coefficient; v is velocity, m/s; g is acceleration of gravity, m/s2; ft is rolling resistance term coefficient; m is gross vehicle weight, kg; a is acceleration, m/s2; α—angle of slope, rad.

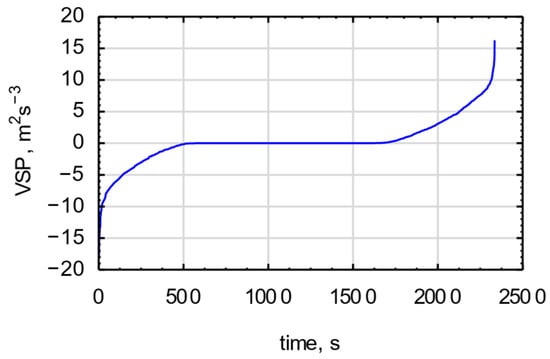

The unit of the VSP index is W/kg−1, or more commonly m2/s−3. An example graph of the VSP as a function of time, from a selected section of the route, ranked from the smallest to the largest values, is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Dependence of VSP on time.

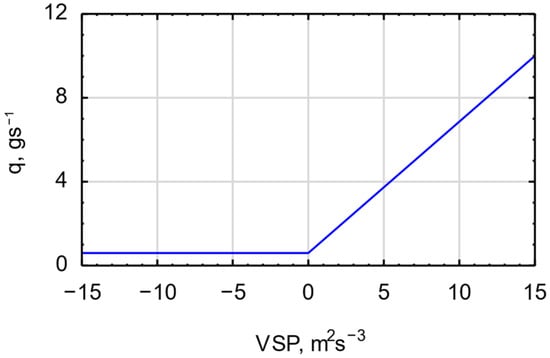

Another important step in the VSP model is the determination of fuel consumption q (gs−1) as a function of the VSP index. For this purpose, the collected data on total fuel consumption on a given route are used. An example of fuel consumption q as a function of the VSP index is shown in Figure 6. The horizontal section of fuel consumption in Figure 6 allows to determine the energy consumed when the bus is stationary. The remaining part of the waveform q = f(VSP) makes it possible to determine the energy consumption required during the bus movement.

Figure 6.

Fuel consumption q as a function of Vehicle-Specific Power (VSP) (Adapted from [35]).

A critical step in the VSP method involves defining intervals and specifying the number of samples per interval. An example of such interval determination is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of Vehicle-Specific Power (VSP) ranges (Adapted from [35]).

Using Equation (3), fuel consumption from the analyzed mileage can ultimately be determined.

where Q denotes the total fuel consumption over a specified driving cycle, g; qi represents the energy consumption rate corresponding to VSP range i, g/s; ti denotes the duration spent in VSP mode i during a specified driving cycle, s.

The precision of fuel consumption estimation using the VSP method depends on the accuracy of the relationship depicted in Figure 6. Rigorous model calibration and precise determination of the curve in Figure 6 reduce the relative error between measured and calculated values to a few percent [42].

In establishing the relationship q = f(VSP), a key criterion is the minimization of the error ∆Q defined by the Equation (4).

where ∆Q is fuel consumption determination error, g; Qm is measured fuel consumption, g; Qe is calculated fuel consumption, g.

2.3. Estimation of VSP Model Parameters for Selected Vehicles

In this study, recorded data obtained from 3 different buses were used to create VSP energy consumption models. The buses run on different lines. Traffic data were collected using the GSP monitoring system, the parameters of which can be found in the article [36]. The GPS used was Teltonika FMB920, the characteristic of which is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specification of Teltonika FMB920 tracker (Adapted from [36]).

The data on fuel consumption and the number of bus passengers came from MPK Rzeszów (Rzeszów, Poland) (municipal transport company) and ZTM Rzeszów (Rzeszów, Poland) (municipal transport authority). All data are from October 2023. In this month, air conditioning was no longer used in the buses analyzed and heating was not yet turned on. The main characteristics of the buses studied are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of the studied buses.

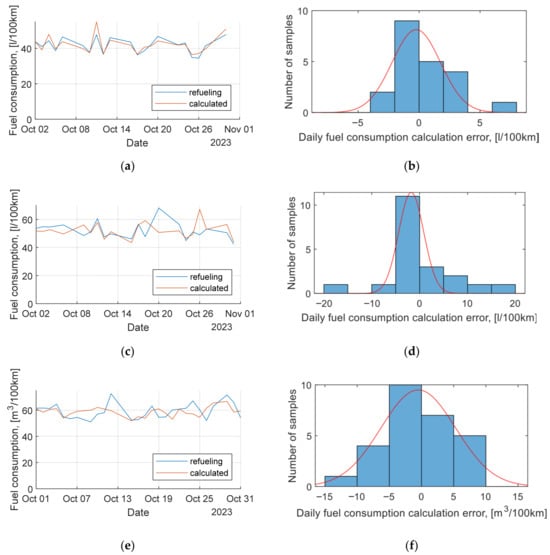

Each of the buses presented in Table 2 was characterized by its individual fuel consumption, defined in L/(100 km) for buses no. 810 and no. 760, or m3/(100 km) for bus no. 943. The results obtained in October 2023, shown in Figure 7a,c,e, are characterized by some variability. The buses ran on different routes at different times of the day. They were often operated by different drivers. In addition, there were often driver changes during the day. This change resulted from the permissible daily work hours limit of the driver. The process of fueling the bus itself was also important. This was performed at the bus depot by an authorized employee after the day of work for every bus. It is very likely that the fuel tank was not always full when refueling. Missing fuel was filled on the following day or days. With the tank capacity of bus no. 810 being 220 L, an underfill of 4–5 L of fuel could have gone unnoticed. In the 760 articulated bus, the fuel tank has a capacity of 360 L. In the 943 CNG bus, the tank capacity was 320 L. With a daily mileage in the range of 100 to 300 km, such a refueling method could have introduced errors when determining fuel consumption per 100 km. In the process of estimating the parameters of the VSP model for the 3 buses in Equation (4), the total fuel consumption for the month of October was used. This approach was intended to eliminate errors that can arise from daily fueling. In October, bus no. 810 consumed 2255.19 L of fuel, the 760 articulated bus consumed of 1715.11 L of fuel, and the 943 CNG bus consumed 3837.26 m3 of CNG. With such amounts of fuel consumed, the error from under-fueling a few l of diesel or m3 of CNG no longer has a significant impact on the results of the model parameter estimation process. VSP models were developed in the MATLAB R2024a software. Daily fuel usage data were used to calibrate the VSP model parameters for each bus separately. Using the developed VSP models, the daily fuel consumption for each bus was determined, which is shown in Figure 7a,c,e. Figure 7b,d,f show the distribution of daily differences between the refueled value and the result of simulation calculations using the VSP models.

Figure 7.

Daily fuel consumption and its calculation error distribution: (a) Daily fuel consumption for bus no. 810; (b) Differences between measured and calculated daily fuel consumption for bus no. 810; (c) Daily fuel consumption for bus no. 760; (d) Differences between measured and calculated daily fuel consumption for bus no. 760; (e) Daily fuel consumption for bus no. 943; (f) differences between measured and calculated daily fuel consumption for bus no. 943.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Calculations Using the VSP Method

Using calibrated VSP models, simulation calculations were performed for the three buses studied. The road slope resistance FW was ignored in the simulation calculations. Most of the trips take place on flat terrain. The difference in elevation did not exceed 30 m. In the calculations, a constant number of passengers was assumed. In most of the cases analyzed, the average number of passengers between bus stops in a 12 m bus during peak hours did not exceed 20–25 passengers. On the trips on 18 October (Figure 4c), the average number of passengers between bus stops reached the value of 24 passengers only once. The average number of passengers on four trips did not exceed 10. The lowest average number of passengers occurred on the first morning trip and was 2.5 passengers. Taking into account the average passenger weight of 60 kg, the average passenger load on the bus varied from 150 kg to 1440 kg. In relation to the unloaded weight of the bus of 11,000 kg, this represents between 1.4% and 13.1%. In the simulation calculations for the 12 m buses, it was assumed that passengers and fuel represent a constant load of 1000 kg. In real traffic conditions, the total weight of the bus could vary both up and down. However, these variations did not exceed 10% of the total weight of the bus.

Research conducted in the work [36] used data from March 2022 on one public transport route in Rzeszów. It did not show significant dependencies in the amount of fuel consumed on the number of passengers transported and thus on the transport work expressed in passenger-kilometers. Similar information can be found in papers [10,39,42,43,44]. The article [39] does not consider real traffic conditions, where stops can account for 20% to 45% of the duration of the trip (Figure 3). The results presented in the work [39] concern fuel consumption in a simple driving cycle. The calculations did not consider stop times, in which fuel consumption does not depend on the number of passengers on board the bus. Therefore, the changes in fuel consumption depending on the number of passengers shown in the article [39] are overestimated. In the case of the 760 articulated bus (net weight 17,500 kg), it was assumed that the additional passenger load was constant at 2000 kg.

As the first part of the simulation of energy consumption, calculations were made for each bus considering its mileage in October. Based on the recorded instantaneous speed profiles from the entire working day, the average speeds on each trip were determined first. Then, using an appropriate energy model for a given bus, the energy consumption for each trip was determined. To compare the energy consumption of diesel buses with a CNG bus, all the results obtained present energy consumption in MJ/km. These results consider the heating value of each fuel. The figures included show the results of calculations for selected days and the aggregate results of energy consumption from the entire month of operation. The second part of the simulation assumes that the movement of the considered buses occurs under the same conditions, that is, along the same route on the selected day. The instantaneous and average speeds are the same. However, in the case of energy consumption, significant differences are noticeable.

3.1.1. Calculation Results for Bus No. 810

On 19 October, the bus was traveling until 19:20 on 15.7 km long route no. 11. From 19:30 the bus was traveling on 11.7 km long route no. 30. During the day, the bus made 16 trips, reaching a maximum speed of over 60 km/h several times, and was driven by two drivers. Both routes ran along the main streets of the city. Figure 8 shows the speed profile for the entire working day, the average speed for each trip, and the average energy consumption determined for each trip.

Figure 8.

Calculation results for bus no. 810 on 19 October 2023: (a) Profile of instantaneous speed during the analyzed working day; (b) Average speed on each trip; (c) Average energy consumption on each trip.

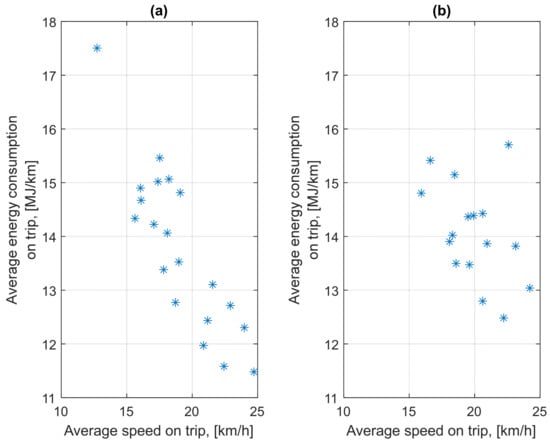

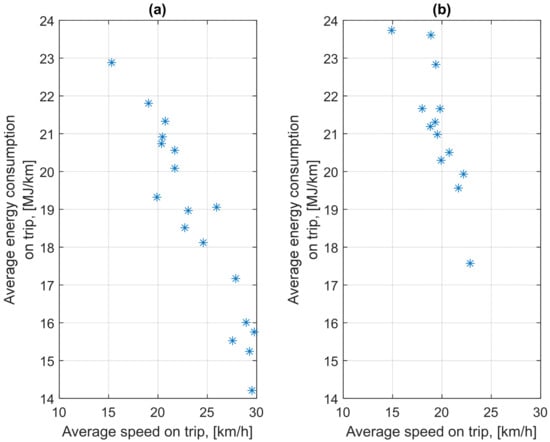

Figure 9 shows the energy consumption per 1 km of the route depending on the average trip speed from two selected days. The bus traveled different routes on the two days considered. On 18 October, the bus operated on the main streets of the city with similar characteristics and traffic volumes. On 19 October, until 17:30, the bus traveled on route no. 10 on secondary downtown streets. After 18:05, the bus traveled on route no. 40 running outside the city center. The characteristics of these routes were different. For this reason, the results shown in Figure 9b are more scattered.

Figure 9.

Average energy consumption per trip depending on average trip speed: (a) on 18 October 2023; (b) on 19 October 2023.

In October, 338 trips were recorded for bus no. 810.

It is necessary to determine whether the volume of the statistical sample is sufficient to obtain a reliable estimate of energy consumption. The necessary number of statistical values of the speed is determined by Formulas (5) and (6):

where tα is confidence probability function; σ2 is variance, (km/h−1)2; Err is extreme error allowed, km/h−1.

where δ is relative accuracy of accounting, δ in {0.02, 0.03}; is average daily speed, km/h−1.

If confidence probability θ = 0.9, then tα = 1.65. In this way, we determine the required number of speed measurements:

Therefore, the statistical sample size is reasonable.

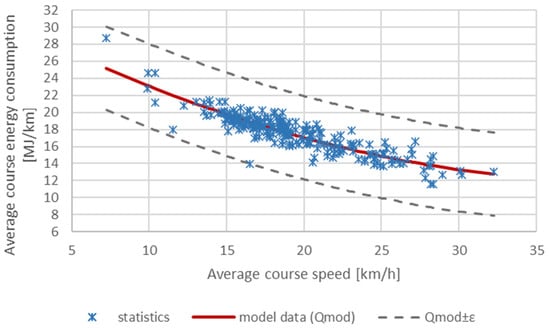

Figure 10 shows the determined energy consumption per 1 km of route for all 338 trips completed in October as a function of the average speed in a given trip. The decrease in energy consumption per 1 km of route as the average speed increases is clear.

Figure 10.

Average energy consumption for all 338 trips of bus no. 810 in October depending on the average speed of a given trip.

Statistical data were approximated by analytical dependencies (8)–(14):

Table 3 shows the coefficient of determination R2 and the sum of squared deviations for each of the obtained models.

Table 4 shows that a more adequate model for estimating average energy consumption is the Second-degree polynomial model (10) (Figure 10). The sum of the squares of the deviations of the experimental data from the model data under this model is the smallest and is 242.2739. At the same time, the largest absolute error value is max(∆Q) = 2.9887 MJ/km. The polynomial (Qmod3) deviates from the discrete function Qm of the statistical (measured) values of average energy consumption by no more than ε > 0:

Table 4.

Approximation results of the dependence of average energy consumption on average speed of a given trip for bus no. 810.

Thus, all statistical data are in a “tube” of width 2ε (Figure 10) relative to the polynomial Qmod3.

3.1.2. Calculation Results for Bus No. 760

On 17 October, the articulated 760 bus operated on 9.8 km route no. 19, which runs along the main streets through the city center. The trips were run from 6:30 to 16:30. During the working day, the bus instantaneous speed, except for two extreme cases, rarely exceeded 50 km/h. The extreme cases in which the bus reached a speed of more than 60 km/h happened during the departure from the bus depot and the return to the bus depot. Figure 11 shows the profile of the instantaneous speed from the entire working day, the average speed for each trip, and the average energy consumption for each trip.

Figure 11.

Calculation results for bus no. 760 on 17 October 2023: (a) Profile of instantaneous speed during the analyzed working day; (b) Average speed on each trip; (c) Average energy consumption on each trip.

The average trip speeds on 17 October were low. This can be seen in Figure 12a. On 18 October, bus no. 760 traveled from 4:35 to 8:04 and from 12:50 to 17:10 on 16.1 km long route no. 12, which runs outside the city center. Figure 12 shows the determined energy consumption per 1 km of route for these two selected days depending on the average trip speed. The characteristics of the relationships are similar. The ranges of the average trip speeds are different.

Figure 12.

Average energy consumption of bus no. 760 per trip depending on average trip speed: (a) Of 17 October 2023; (b) Of 18 October 2023.

For bus no. 760, 236 trips were recorded in October. The minimum required statistical sample size for bus 760 is determined similarly to (5) and (6) with θ = 0.95 and δ = 0.03:

The sample size is sufficient.

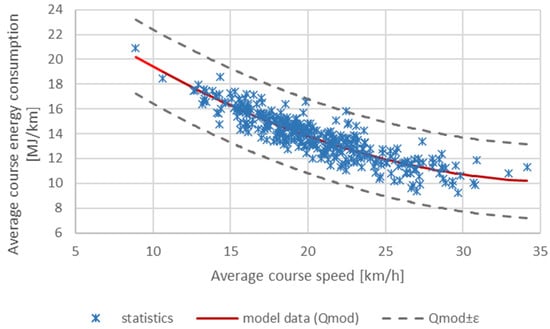

Figure 13 shows the determined energy consumption per 1 km of route for all trips made in October, depending on the average trip speed. In the range of the average trip speed of 10 to 30 km/h, a significant relationship between energy consumption and average trip speed is visible.

Figure 13.

Average energy consumption for all 236 trips of bus no. 760 in October depending on the average trip speed.

Approximation of discrete values of average energy consumption depending on average values of speed was carried out (Figure 13). The specified dependence for estimating the average energy consumption is most accurately is approximated by a second-degree polynomial (17):

The sum of the squares of the deviations of the experimental data from the model data under this model is 243.2285 (R2 = 0.8035). At the same time, the largest absolute error is ε = 4.9023 MJ/km.

3.1.3. Calculation Results for Bus No. 943

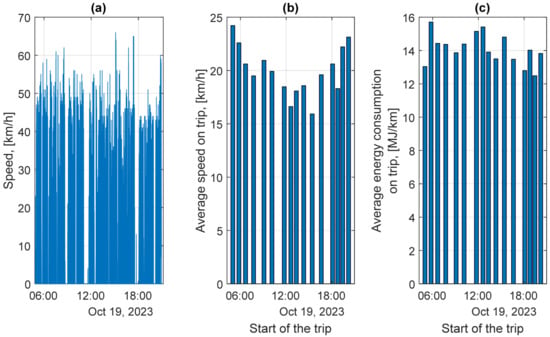

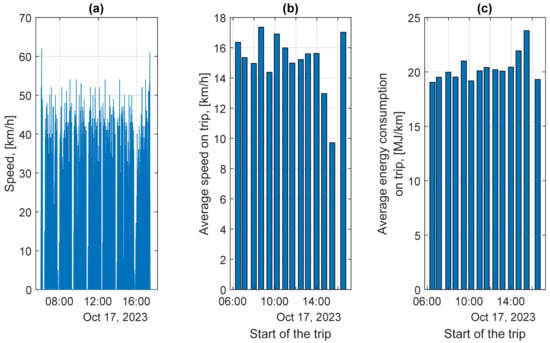

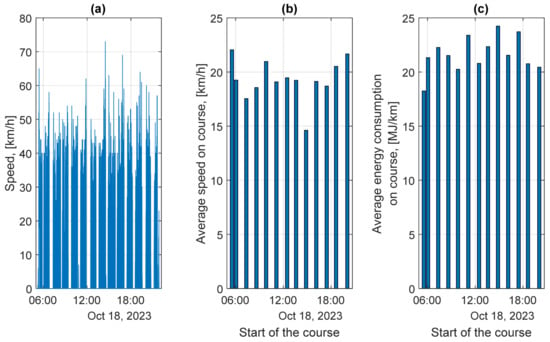

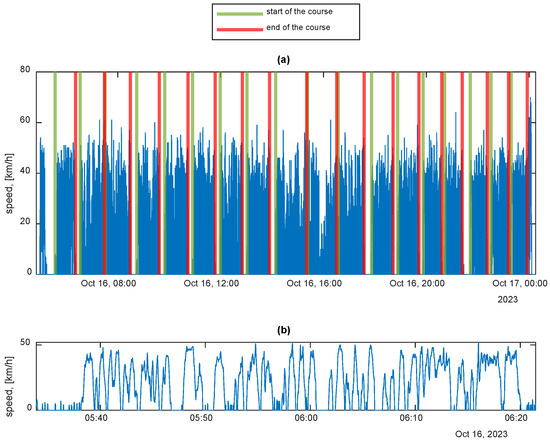

The CNG-powered 943 bus was traveling on 18 October on the 18.6-km-long route no. 15, that runs through the city center. Between the hours of 5:32 and 21:27, it made 13 trips. Figure 14 shows the profile of instantaneous speed from the entire working day, the average speed on each trip, and the average energy consumption on each trip.

Figure 14.

Calculation results for bus no. 943 of 18 October 2023: (a) Profile of instantaneous speed during the analyzed working day; (b) Average speeds on each trip; (c) Average energy consumption on each trip.

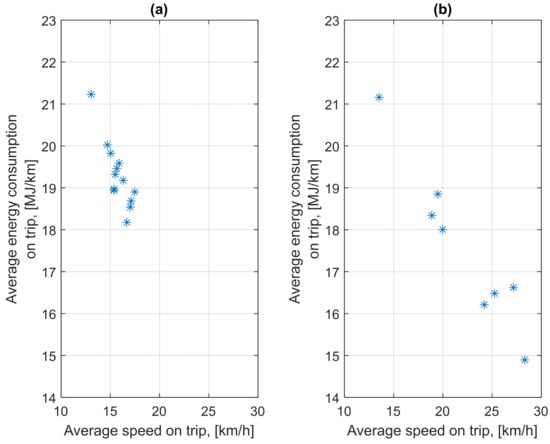

On 17 October, bus no. 943 operated on two routes that mostly ran outside the city center. From 5:53 to 8:30 and from 12:25 to 19:30, it was an 18.4-km route no. 16. From 3:45 to 5:43, from 8:45 to 12:17 and from 19:46 to 21:40, the bus traveled on a 14.9 km long route no. 33. Routes outside the city center were characterized by higher average trip speeds than those on 18 October.

Figure 15 shows the determined energy consumption per 1 km of route on each trip depending on the average trip speed on two selected days.

Figure 15.

Average energy consumption on trip depending on average trip speed: (a) on 17 October 17 2023; (b) on 18 October 2023.

For bus no. 943, 411 trips were recorded in October. The minimum required statistical sample size for bus 943 is determined similarly to (5) and (6) with θ = 0.95 and δ = 0.02:

The sample size is sufficient.

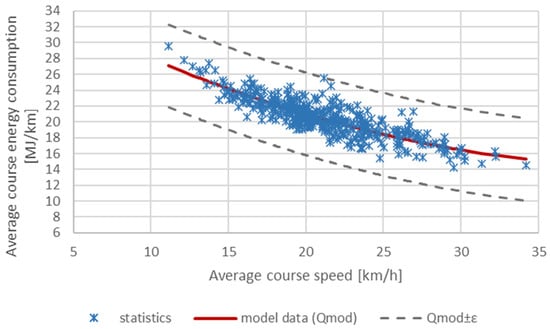

Figure 16 shows the energy consumption per 1 km of route as a function of average trip speed for all the trips completed in October. The relationship between the average trip speed and the average energy consumption is clearly visible.

Figure 16.

Average energy consumption for all 411 trips of bus no. 943 in October depending on the average trip speed.

Approximation of discrete values of average energy consumption depending on average values of speed was carried out (Figure 16). The specified dependence for estimating the average energy consumption is approximated by a second-degree polynomial (19):

The sum of the squares of the deviations of the experimental data from the model data under this model is 637.97 (R2 = 0.73). At the same time, the largest absolute error in energy consumption estimation is 5.2142 MJ/km.

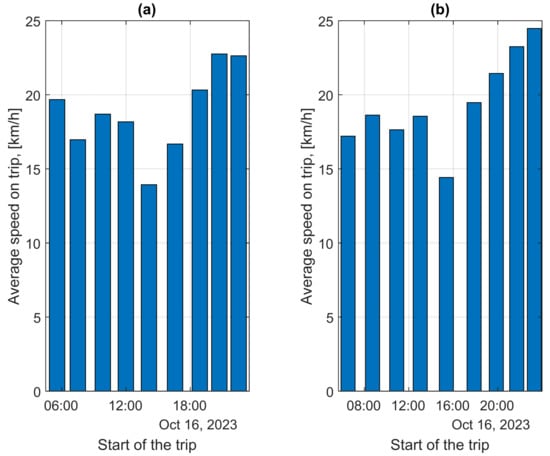

3.1.4. Simulation of Energy Consumption on the Same Route

The previous subsections presented the results of the energy consumption simulations for buses traveling on different routes. Therefore, it is not possible to directly compare the energy consumption results for these buses. To make such a comparison, simulation calculations were performed again. This time, all buses in the energy consumption simulation used data from the recorded speed profile of bus no. 810 on 16 October 2023. This profile and its time slice are shown in Figure 17. On that day, this bus was traveling on route no. 6 shown in Figure 1. During the energy consumption simulation, the recorded instantaneous speed profile for each trip was separated into two groups. Each of them considers a different travel direction. This division resulted from the different traffic volumes in the two directions, as shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 17.

Speed profile: (a) from the whole day; (b) from the selected trip.

Figure 18 shows the average trip speeds for the two traffic directions. The greatest differences in the average trip speeds can be seen in the morning hours. During these hours, there are also quite significant differences in traffic volume between the two directions, as shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 18.

Average trip speeds depending on the start time of the trip: (a) in direction A–D; (b) in direction D–A.

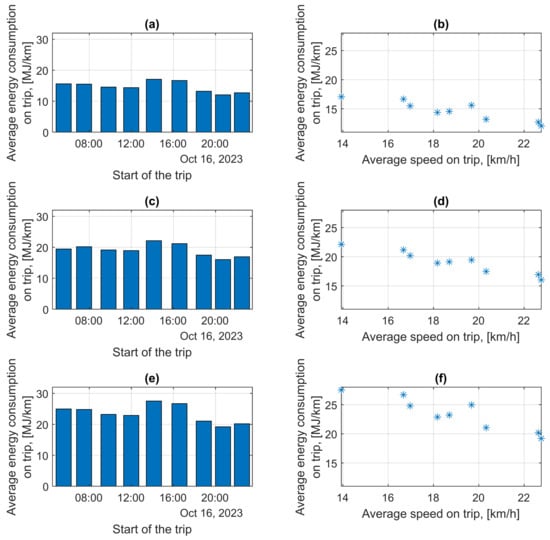

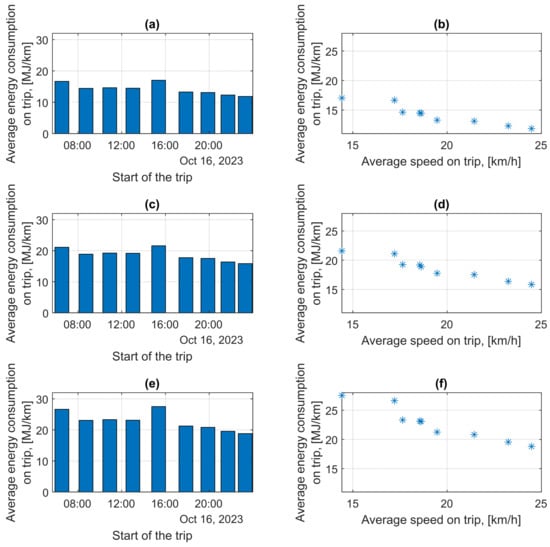

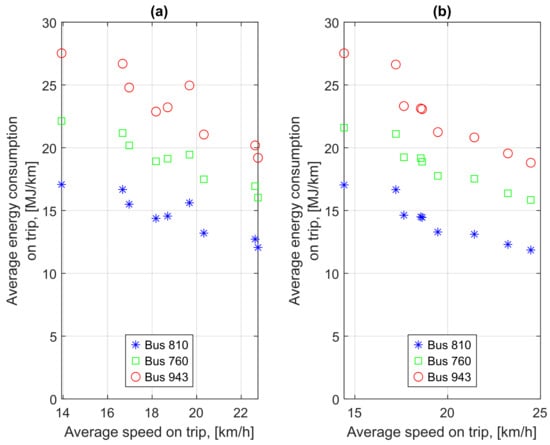

Figure 19 shows the results of simulation calculations of energy consumption per 1 km of route for the three buses considered and the energy consumption graph as a function of average trip speed in the A–D direction.

Figure 19.

Average energy consumption on the trip in the A–D direction: (a) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 810; (b) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on average trip speed for bus no. 810; (c) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 760; (d) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on average trip speed for bus no. 760; (e) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 943; (f) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the average trip speed for bus no. 943.

Figure 20 shows the results of simulation calculations of energy consumption per 1 km of the route for the three buses considered and the energy consumption graph as a function of average trip speed in the D–A direction.

Figure 20.

Average energy consumption on the trip in the D–A direction: (a) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 810; (b) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on average trip speed for bus no. 810; (c) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 760; (d) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on average trip speed for bus no. 760; (e) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the trip start time for bus no. 943; (f) Average energy consumption on the trip depending on the average trip speed for bus no. 943.

Figure 21 shows a comparison of energy consumption per 1 km of route for all three buses and both directions of traffic. In most cases, a decrease in average speed results in an increase in energy consumption. CNG-powered bus no. 943 had the highest energy consumption. The calculations assumed that buses no. 810 and no. 943 carry the same number of passengers. Articulated bus no. 760 was assumed to carry almost twice as many passengers as bus no. 810 or no. 943.

Figure 21.

Comparison of energy consumption of buses studied; (a) in direction A–D; (b) in direction D–A.

3.2. Analysis of Simulation Results

Figure 10, Figure 13 and Figure 16 show that the relationship between the average trip speed and energy consumption per 1 km of route is visible. This applies to all the buses considered. A decrease in the average trip speed leads to an increase in energy consumption. In these figures, several points away from the main cluster are visible. In relation to the number of calculation results, they represent a very small share. They are probably caused by random disturbances, such as lane blockage due to an accident or vehicle breakdown. The scattering of results is also influenced by the nature of the route. An example of this influence can be seen in Figure 9b. This figure shows results from routes through downtown streets that are not major thoroughfares, as well as through streets outside the city center.

During their monthly operation, the buses considered ran on different routes. The selected operating parameters of these buses are presented in Table 4. The average trip speeds during the month were similar for all three buses and ranged from 19.29 to 21.24 km/h. The difference between the maximum and minimum value was approximately 10%. The coefficient of variation of the average trip speed was similar in all buses. The standard deviation was also almost similar. The data with these values are shown in Table 4 and were determined for all trips of a given bus in October (338, 236, and 411 samples, respectively). Noticeable differences occur in the energy consumption per 1 km of route. In this case, the total weight of the bus and the type of engine have a strong influence. A CNG-powered engine is characterized by a lower energy efficiency. The CNG-powered bus was characterized by the highest energy consumption. The results of the energy consumption calculations are also shown in Table 5. Despite the significant differences in energy consumption, the coefficients of variation in energy consumption do not differ significantly from each other.

Table 5.

Selected results of energy consumption simulation on various routes.

Table 6 shows the results of the simulation of energy consumption for three buses traveling on the same route in one day.

Table 6.

Selected parameters of energy consumption simulation on the same route.

CNG-powered bus no. 943 had the highest average energy consumption. Bus no. 810 had the lowest energy consumption. The energy consumption of all buses was greater than that shown in Table 4. Due to the vastly different number of samples analyzed (18 samples from one day and 236 to 411 from the entire month), it is appropriate to only compare the nature of the changes occurring and not the values obtained.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The research was conducted in the city of Rzeszów. The size of the city and its traffic conditions have a significant impact on the energy consumption of a public bus. In small cities with approximately 50,000 inhabitants, the fuel consumption of the 12 m diesel city bus ranges from 35 to 38 L/100 km. In Rzeszów, which has 200,000 inhabitants, it is between 41 and 43 L/100 km. In large cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants, the same bus has a fuel consumption of 45–48 L/100 km. In the case of energy consumption, the average and maximum speeds of the bus are also important. In many cases, confirmed by previous studies [35], an increase in the maximum bus speed on the route to 70 km/h, despite an increase in the average trip speed, contributed to an increase in energy consumption. At high speeds, more of the vehicle’s kinetic energy was lost in the braking process and the driver was accelerating more aggressively.

During the research, the dependence of the average trip energy consumption on the average trip speed for fixed routes of the three studied city buses (diesel bus, articulated diesel bus, and CNG-powered bus) was constructed. These dependencies are well approximated by polynomials of the second degree. At the same time, the absolute modeling error for these three buses does not exceed 5.2142 MJ/km.

For the city studied, the research showed that as the average trip speed decreased, the energy consumption increased for all three buses considered. In most cases, the decrease in this speed is the result of stops caused by traffic conditions on the route. Thus, measures taken by city authorities to smooth traffic flow can contribute to lower energy consumption and shorter travel times. Such measures will also contribute to increasing the competitiveness of public transport in relation to individual transport by car.

Among the buses studied, diesel bus no. 810 had the lowest energy consumption. The energy consumption of CNG-powered bus no. 943 is approximately 50% higher than that of bus no. 810. The energy consumption of articulated bus no. 760 is approximately 30% higher than that of bus no. 810. However, the CNG bus has lower environmental emissions [46]. The selection of a suitable bus for a given route must take into account the route requirements. For the city center, ecology is the most important factor. In the absence of electric buses, the CNG bus will be the preferred means of transport there. For other routes outside the city center, it can be assumed that the most important criterion is energy consumption. Many parameters must be considered when choosing a bus. Examples of these parameters are passenger flow and trip frequency. For large passenger flows, an articulated bus is more suitable. An increase in energy consumption of approximately 30% compared to that of bus no. 810 is offset by almost twice the passenger capacity. With a large number of passengers, the energy consumed per 1 passenger-kilometer will be significantly lower. The number of vehicles on the road will also be reduced, reducing road congestion. The constructed energy model and the adopted simulation methodology proved to be fully useful for determining the energy consumption of public transport. The model will be used for further comprehensive work considering a much larger number of considered routes and buses. Based on fuel or energy consumption models, it is possible to calculate environmental pollution. Such activities are part of the sustainable development of public transport. The main goal of further work will be to develop action plans aimed at reducing energy consumption and thus environmental pollution.

This study has limitations:

- Only bus operation in October was studied—October has the lowest fuel consumption, because there is no heating or cooling in the bus. This allows to best study the impact of traffic on fuel consumption.

- Ambient temperature was not considered.

- Constant passenger load was assumed.

- Most of the city is located on flat terrain, so the road grade was assumed to be 0.

- Buses rarely exceeded 50 km/h with passengers, so the impact of higher speeds is not known.

Future research should be aimed at removing the aforementioned limitations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and V.M.; methodology, M.S. and N.K.; software, J.M.; validation, M.S., and V.M.; formal analysis, M.S. and N.K.; investigation, V.M.; resources, V.M.; data curation, J.M. and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and N.K.; visualization, J.M. and N.K.; supervision, V.M.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gupta, J.; Chen, Y.; Rammelt, C. Transport within Earth System Boundaries. npj Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2024, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazos, J.S.; Ardila, L.M.; Cardona, C.J. Energy transition in sustainable transport: Concepts, policies, and methodologies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 58669–58686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; de Barros, A.G.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Public Transportation and Sustainability: A Review. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevia, D.; Mukhopadhyay, C.; Lathia, S.; Gounder, K. The role of urban transport in delivering sustainable development goal 11: Learning from two Indian cities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Khan, K.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. 2030 agenda of sustainable transport: Can current progress lead towards carbon neutrality? Transp. Res. Part. D Transp. Environ. 2023, 122, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziioannou, I.; Nikitas, A.; Tzouras, P.G.; Bakogiannis, E.; Alvarez-Icaza, L.; Chias-Becerril, L.; Karolemeas, C.; Tsigdinos, S.; Wallgren, P.; Rexfelt, O. Ranking Sustainable Urban Mobility Indicators and their matching transport policies to support Liveable City Futures: A micmac approach. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 18, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Dobrzanska, M.; Dobrzanski, P. Rzeszow as a City Taking Steps Towards Developing Sustainable Public Transport. Sustainability 2019, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, K.; Pietrzak, O. Environmental effects of electromobility in a sustainable urban public transport. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzanski, P.; Smieszek, M.; Dobrzanska, M. Bicycle transport within selected Polish and European Union cities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 27, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shan, X.; Ye, J.; Yi, F.; Wang, Y. Evaluating the effects of traffic congestion and passenger load on feeder bus fuel and emissions compared with passenger car. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Ali, A.M.; Attia, T. Optimizing Electric bus performance via Predictive Maintenance: A combined experimental and Modeling Approach. Front. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 1506866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Hu, J.; Shao, L.; Feng, T.; Appolloni, A. Can public transportation development improve urban air quality? Evidence from China. Urban Clim. 2024, 54, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, M.W.; Liberini, F.; Russo, A.; Ommeren, J.N. The congestion relief benefit of public transit: Evidence from Rome. J. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 21, 397–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.; Chen, W.; Tariq, K.; Linjun, H.; Zhaosheng, L. Role of public transportation in reducing traffic congestion, enhancing connectivity, and promoting Sustainable Urban Development in Manchester and Shenzhen. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Invent. 2025, 12, 8401–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Pradhan, R.P. A comprehensive review and research agenda on the adoption, transition, and procurement of electric bus technologies into public transportation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 75, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, C.; Sanzò, N.; Dorsini, R.; Nigliaccio, G.; Di Florio, G.; Cigolotti, V.; Agostini, A. An economic and environmental assessment of different bus powertrain technologies in public transportation. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 16, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport. Annual Bus Statistics: Year Ending March 2024 (Revised); GOV.UK: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-bus-statistics-year-ending-march-2024 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Dzikuć, M.; Miśko, R.; Szufa, S. Modernization of the public transport bus fleet in the context of low-carbon development in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.; Dias, G.; Mendes, J.F. Public transport decarbonization: An exploratory approach to bus electrification. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Transportation Carbon Reduction Technologies: A Review of Fundamentals, application, and performance. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 11, 1340–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyan, A.F.; Haouari, M.; Sleiti, A. Decarbonizing public transportation: A multi-criteria comparative analysis of battery electric buses and fuel cell electric buses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrese, S.; Gemma, A.; La Spada, S. Impacts of driving behaviours, slope and vehicle load factor on bus fuel consumption and emissions: A real case study in the City of Rome. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 87, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Yan, H.; Pan, S.; Li, X.; Gu, X. Bus system optimization for timetables, routes, charging, and facilities: A summary. Digit. Transp. Saf. 2025, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Xue, Y.; He, H.-D.; Lu, W.-Z. Impacts of traffic congestion on fuel rate, dissipation and particle emission in a single lane based on Nasch Model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 503, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Dai, G.; Zhao, J.; Long, B.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S. Optimization model for bus priority control considering carbon emissions under non-bus Lane conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstam, J.; Häll, C.H.; Bhattacharyya, K.; Gebrehiwot, R. Traffic impacts of dynamic bus lanes: A simulation experiment of real-world bus operations. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2025, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Batista, S.F.A.; Menéndez, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Powering up urban mobility: A comparative study of energy efficiency in electric and diesel buses across various lane configurations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartłomiejczyk, M.; Jagiełło, A.; Wołek, M. The role of bus traffic prioritization in optimizing battery size and reducing the costs of electric buses. Energies 2025, 18, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ding, J.; Lin, J.; Zheng, G.; Sun, Y.; Fang, J.; Xu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Gu, B. Big-data empowered traffic signal control could reduce urban carbon emission. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostopoulos, A.; Galanis, A.; Kehagia, F.; Politis, I.; Theofilatos, A.; Lemonakis, P. Using a microsimulation traffic model and the vehicle-specific power method to assess turbo-roundabouts as Environmentally Sustainable Road Design Solutions. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.S.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. A telemetric framework for assessing vehicle emissions based on driving behavior using unsupervised learning. Vehicles 2024, 6, 2170–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, G.O.; Gonçalves, G.A.; Farias, T.L. A Methodology to Estimate Real-world Vehicle Fuel Use and Emissions based on Certification Cycle Data. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 111, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rakha, H.A. Fuel consumption model for conventional diesel buses. Appl. Energy 2016, 170, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, T.; Li, H. Improving urban bus emission and fuel consumption modeling by incorporating passenger load factor for real world driving. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Mateichyk, V. Determining the fuel consumption of a public city bus in urban traffic. In Proceedings of the 26th International Slovak-Polish Scientific Conference on Machine Modelling and Simulations (MMS 2021), Bardejovské Kúpele, Slovakia, 13–15 September 2021; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1199, p. 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Kostian, N.; Mateichyk, V.; Mosciszewski, J.; Tarandushka, L. Estimation of the Public Transport Operating Performance: Example of a Selected City Bus Route. Commun.-Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2023, 25, B7–B21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Mateichyk, V.; Dobrzanska, M.; Dobrzanski, P.; Weigang, G. The Impact of the Pandemic on Vehicle Traffic and Roadside Environmental Pollution: Rzeszow City as a Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieszek, M.; Mateichyk, V.; Kostian, N.; Tarandushka, L.; Mosciszewski, J. Analysis of the time and number of stops during the operation of selected public bus line in rzeszow. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, L. Analysis of the influence of passenger load on bus energy consumption a vehicle-engine combined model-based simulation framework. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macor, A.; Rossetti, A. Fuel consumption reduction in urban buses by using power split transmissions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 71, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Du, J.; Xiong, Y. Study on driving cycle synthesis method for city buses considering random passenger load. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 3871703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, F.; Fonseca, N.; López, J.-M.; Casanova, J. Effects of passenger load, road grade, and congestion level on real-world fuel consumption and emissions from compressed natural gas and diesel urban buses. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, H.C.; Rouphail, N.; Zhai, H.; Farias, T.; Gonçalves, G.A. Comparing real-world fuel consumption for diesel- and hy-drogen-fueled transit buses and implication for emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, R.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Fu, L.; Hao, J. Real-world fuel consumption and CO2 emissions of urban public buses in Beijing. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmark, S.L.; Wang, B.; Sperry, R. Comparison of on-road emissions for hybrid and regular transit buses. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2013, 63, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.; Yasmin, T.; Shakoor, A. International experience with compressed natural gas (CNG) as environmental friendly fuel. Energy Syst. 2015, 6, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).