1. Introduction

The global drive toward sustainable development and mitigating climate change necessitates innovative energy solutions across all sectors, including household appliances. The IPCC report from 2023 underscores human activity as the primary cause of global warming, making energy efficiency a cornerstone of the energy transition [

1,

2]. Household appliances (AGD) contribute significantly to global energy consumption; in 2022, EU households accounted for 25.8% of the final energy consumption, with heating (space and water) being dominant [

3]. Even marginal efficiency improvements in individual appliances, scaled across the vast market, yield substantial macro-level benefits. Regulatory pressures, such as the EU Ecodesign Directive (2009/125/EC) and Energy Labeling Regulation (2017/1369), compel manufacturers to integrate advanced energy recovery technologies to achieve higher efficiency classes [

4]. This regulatory landscape, coupled with rising consumer environmental awareness, transforms energy efficiency from a technical challenge into a strategic market imperative.

Despite technological advancements, many household appliances, including dishwashers, operate below optimal energy efficiency. Significant energy is irreversibly lost as waste heat from hot drain water or from operating components such as heating elements. In modern dishwashers, approximately 67% of the total energy is consumed by the internal electric heating element [

5]. This substantial energy consumption highlights the potential for significant savings through effective heat recovery [

6]. For instance, recovering heat from dishwasher greywater can yield annual electricity savings of 53.48 kWh and increase dishwasher efficiency by about 16% [

7]. Existing mechanisms for improving efficiency, such as improved insulation or optimized cycles, often fail to fully address inefficient thermal energy management, as waste heat is rarely effectively recovered. Current designs may prioritize production costs and reliability over maximizing heat recovery [

8]. This indicates a need for more sophisticated, active heat recovery solutions that integrate directly into appliance functionality [

9].

Optimizing thermal processes is crucial for overcoming current energy efficiency barriers in household appliances [

10]. Heat exchangers are fundamental for transferring thermal energy between fluids without direct mixing [

11]. Counter-flow heat exchangers are particularly effective, as hot and cold fluids flow in opposite directions, maximizing the temperature gradient along the exchanger’s length and leading to more efficient heat transfer. This principle is quantitatively described by Fourier’s law for heat conduction and the heat balance equation involving the overall heat transfer coefficient (U) and the logarithmic mean temperature difference (LMTD) [

12]. The key parameters that influence heat exchanger performance include heat exchange surface area, fluid flow velocity, temperature difference between hot and cold fluids, fluid thermophysical properties, and fouling. Maximizing surface area (e.g., via meandering channels) and optimizing flow for turbulence are critical for efficiency. The selection of materials with high thermal conductivity and corrosion resistance is also vital for durability and performance in the dishwasher’s harsh environment (high temperatures, humidity, and alkaline detergents).

A counter-flow heat exchanger is characterized by a configuration in which the hot outflow water flows in the opposite direction to the cold inflow water. This maintains a high temperature gradient along the entire length of the exchanger, enabling more efficient thermal energy transfer. A key aspect of the design is the appropriate selection of materials resistant to corrosion, detergents, and high temperatures, ensuring long-term use in the aggressive environment of a dishwasher.

The designated location for installing a counter-flow heat exchanger (heat exchanger on the side wall, HEBS) in a dishwasher is the side wall of the wash chamber in the area known as the air gap, whose primary function is to prevent water backflow in the hydraulic system. The air gap serves as a buffer zone, housing the heat exchanger, allowing water to flow in a counter-flow manner. This solution allows for heat recovery from hot wastewater that leaves the wash chamber after the wash cycle is completed. This heat is transferred to the cold water entering the machine, allowing its temperature to be raised before the next wash cycle begins. This arrangement significantly reduces the demand for electricity, which is typically used to heat water.

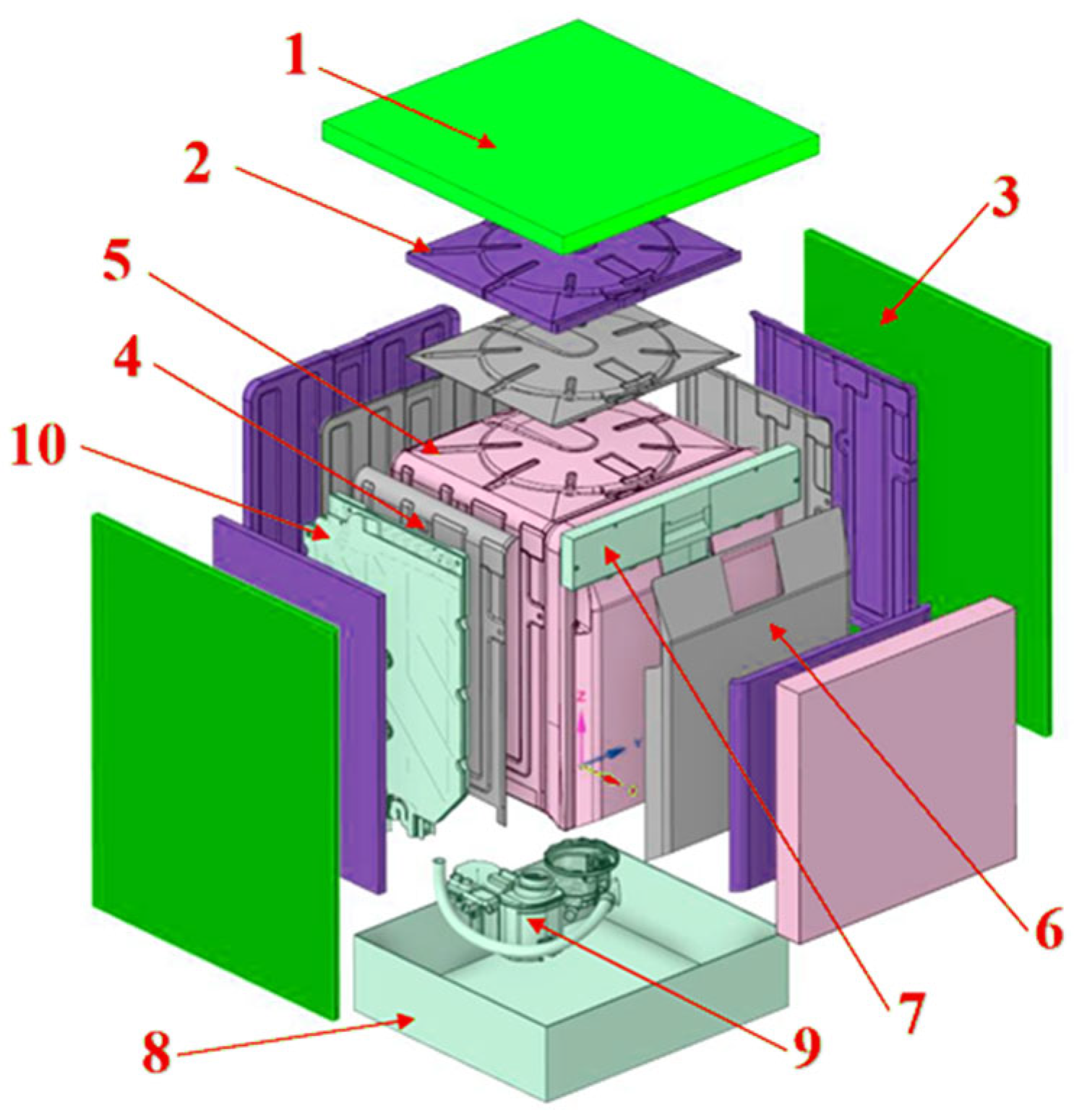

In the presented design, based on the model used in dishwashers from a leading manufacturer, the heat exchanger is integrated into a plastic side panel. Inside, a meandering channel maximizes the heat exchange surface while maintaining a compact design. The attached drawings show the design details of the heat exchanger and its layout within the dishwasher. The channel structure and flow direction of the cold and hot water are also visible, illustrating the principle of counter-flow. This configuration achieves intensive heat exchange with minimal pressure loss, positively impacting the appliance’s energy efficiency (

Figure 1).

Household appliance electrification and tighter regulatory targets motivate heat-recovery measures that are compact, low-cost, and robust against aggressive operating environments. Although the present study focuses on a side wall counter-flow exchanger concept, it is important to place the design within the broader landscape of domestic heat-recovery research. Recent works have explored plate, coaxial, and microchannel geometries for greywater recovery, each with trade-offs between pressure drop, manufacturability, fouling sensitivity, and thermal effectiveness.

Unlike typical waste heat recovery systems based on large, external storage tanks, the proposed HEBS solution addresses a specific engineering challenge: integrating a high-efficiency counter-flow exchanger into the extremely limited volume of the appliance’s ‘air gap’ (side wall). This constraint prohibits the use of standard shell-and-tube geometries. Furthermore, this study focuses on the transient heat exchange during the rapid ‘filling phase’ (dynamic flow), which differs significantly from static heat recovery from stored greywater. Therefore, the novelty of this work lies not in the appliance itself, but in the validation of a compact, integrated exchanger design under transient operating conditions, providing a verified methodology for industry-standard appliances.

Despite compelling laboratory demonstrations, a persistent challenge for appliance-integrated exchangers is the divergence between numerical predictions and measured energy recovery. The causes include

Systematic quantification of these effects is a prerequisite for technology transferring from prototype to product. Accordingly, this paper contributes three practical advances:

an explicit comparison that not only reports global performance (ΔT, recovered energy) but also decomposes the dominant uncertainty sources and their numerical proxies,

a pragmatic sensitivity study (parameter sweep of outer wall HTC, contact resistance, and flow maldistribution) that identifies the parameters to which HEBS performance is most responsive,

design recommendations that bridge CFD-level improvements with manufacturability considerations. Namely, geometric changes and sensor and measurement strategies that reduce measurement uncertainty in validation campaigns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CFD Numerical Simulation Methodology

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is an indispensable tool for analyzing fluid flow and heat transfer: it enables precise modeling of the underlying phenomena, optimizes heat exchanger design, and allows for an assessment of energy efficiency while reducing the time and cost of experimental testing [

15,

16].

Simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent 2022R2, which employs the finite volume method (FVM) to discretize the governing equations of fluid flow. The continuity, Navier–Stokes, and energy equations were solved; for turbulent flows, the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) approach with the k-ω shear stress transport (SST) turbulence model was used, offering a good compromise between accuracy and computational cost [

17]. The selection of these models ensures a trade-off between computational efficiency and solution fidelity [

18], which is based on the following expressions:

where

is the density [kg/m

3],

is the flow velocity vector [m/s],

τ is the viscous stress tensor [Pa],

p is the pressure [Pa],

is the gravitational acceleration [m/s

2], T is the temperature [K],

E is the internal energy [J/kg],

keff is the effective thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)], and

SE is the volumetric energy source term [W/m

3]. The partial derivative operator (i.e.,

) denotes the change in density over time. The divergence operator

denotes how much mass is “spread out” at a given point. The convection operator

is the propagation of momentum (tensor) in space (how momentum is transferred through the flow) and

is the divergence of the viscous stress tensor. The gradient operator

is the force resulting from the pressure drop (which acts against the pressure gradient).

Near the walls, the k-ω model provides a better representation of the boundary layer and a correct prediction of the velocity gradients and shear stresses. In the flow region far from the walls, the k-ε model’s functionality is utilized, which is more effective at describing flows with large eddies. A switch in the SST mechanism allows for smooth transitions between these approaches, making the k-ω SST model particularly effective in analyzing near-wall, separating, and boundary layer flows with large velocity gradients. This model is widely used in engineering applications, offering a compromise between accuracy and computational cost. The transport equation for the turbulent kinetic energy

k and the specific dissipation rate

ω is given as follows:

where

is the turbulent viscosity [Pa·s],

k is the turbulent kinetic energy [m

2/s

2],

ω is the turbulence frequency,

is the density [kg/m

3],

µ is the dynamic molecular viscosity [Pa·s],

is the spatial gradients defining the direction and rate of change in ω in space (important for diffusion),

is the flow velocity vector [m/s],

Pk is the turbulent kinetic energy production [W/m

3],

are the model coefficients that represent the turbulent Prandtl numbers that control the diffusive transport of

k and

ω in their respective transport equations, and

α and

β are the model constants [

19,

20].

Due to the complexity of the dishwasher wash cycle, it was necessary to simplify the analyses to encompass all the interdependencies between components [

21,

22]. To achieve this undertaking, the number of process steps was reduced—for example, the short rinsing and drying phases were omitted and the time control method was simplified, focusing on the main phases of water intake, heating, and circulation. The complexity of the dishwasher design offers extensive optimization opportunities [

23]; therefore, a model-based approach was necessary to assess the effects in all the key aspects of the device’s operation [

24].

2.2. Geometry and Boundary Conditions for HEBS

The CAD model was prepared in ANSYS SpaceClaim 2023R1 (

Figure 2) based on components from a commercial dishwasher. The geometry was simplified for computational efficiency by removing unnecessary details such as small embossments, roundings, and recesses. This adaptation ensured system consistency, reduced the model size, and significantly accelerated the solution process.

The numerical mesh for the sidewall heat exchanger, which included the washing chamber, comprised 4,588,633 polyhedral elements with a minimum orthogonal quality of 0.1507 [

22]. The material data for the various components and fluids were obtained from the ANSYS Fluent 2022R2 database and literature.

Several physical simplifications were applied: fluid properties such as water viscosity and density were assumed constant, the effects of cavitation and surface tension were omitted, and the flow was treated as stationary. The boundary conditions were reduced to key parameters—i.e., steady temperatures and inlet/outlet flows—which enabled stable and convergent results in the nonlinear analyses.

The simulation focused on the critical moment of filling the heat exchanger tank with cold mains water (15 °C), while hot water (55 °C) was injected into the washing chamber from spray arms. The heat exchanger design featured a thin (0.4 mm) aluminum tube for hot water flow, in direct contact with the incoming cold water, and a meandering channel system to maximize heat transfer. The original ventilation hole was eliminated to increase the contact area.

Boundary conditions included:

temperatures: hot water at ~55 °C, cold water at ~15 °C, and ambient at 20.4 °C,

mass flow: cold water flow of 0.0417 kg/s (2.5 L/min) for a 120-s exchange time,

outer walls: convection boundary condition with a heat transfer coefficient (HTC) of 3.5 W/(m2·K) (determined from a separate calibration experiment),

chamber–HEX interface: calibrated heat-transfer coefficient, HTC

chamber ≈ 8.3 ± 1.2 [W/m

2∙K] (at ≈ 60 °C). The value was determined in a dedicated calibration experiment performed for representative heat transfer conditions (a brief summary of the procedure and uncertainty assessment is in

Section 2.5). In the sensitivity analysis, the range HTC

chamber ∈ [5, 12] [W/m

2∙K] was assumed, which explains a significant part of the initial simulation overestimation,

solver settings: PISO scheme for pressure-velocity coupling, PRESTO! for pressure spatial discretization, and compressive method for volume fraction discretization. First-order upwind schemes were used for other spatial discretizations. The optimal time step was 0.025 p.

2.2.1. Mesh Strategy and Quality

A polyhedral-dominant mesh was generated with prism (inflation) layers at all the solid-fluid interfaces. This topology was specifically chosen to accurately resolve flow gradients near the curved walls and fillets of the heat exchanger, ensuring high fidelity in complex geometric regions (

Figure 3). To properly resolve boundary layers [

25]. The mesh objectives and quality targets were:

target y+ in the near-wall cells: y+ ≤ 1 on all the walls where conjugate heat transfer is important (tube surfaces and channel walls); where y+ ≤ 1 could not be achieved in coarse grids, wall functions were used and documented,

prism layer specification: 5–8 prism layers, a growth ratio of 1.2, and a first-layer thickness chosen to meet y+ target based on estimated local uτ from preliminary runs,

cell types: a polyhedral core with a boundary inflation, a typical skewness of <0.85, and a minimum orthogonal quality of >0.15 (with a reported minimum of 0.1507 for the final grid).

2.2.2. Numerical Discretization and Solver Settings

The spatial discretization and temporal settings were as follows:

pressure–velocity coupling: PISO for transient runs (and SIMPLE for steady approximate solutions used in preliminary studies),

spatial schemes: pressure PRESTO!, momentum and energy: second-order upwind, VoF advection: compressive scheme, and gradients: least-squares cell-based,

limiters and relaxation: MUSCL-type reconstruction with default Fluent limiters, limiter settings and under-relaxation factors were adjusted to ensure monotonicity in strongly convective zones (settings: a momentum under-relaxation of 0.7 and a pressure of 0.3 for transient PISO inner iterations),

temporal discretization: second-order implicit and time step chosen as Δt = 0.025 s (sensitivity checked with Δt = 0.01 − 0.05 s). The Courant number was monitored and kept below 1 in the critical regions for VoF.

2.2.3. Convergence Criteria and Monitoring

Residual targets: 1 × 10−6 for energy and 1 × 10−5 for momentum. Additionally, mass conservation and monitored integral quantities (mass flow at inlets, outlet temperature, and heat transfer rate ) were required to show temporal stability (monitored over at least five characteristic time scales). For steady-state approximations, integral convergence and the constant thermal power were required rather than the absolute residual thresholds alone.

2.2.4. Grid Independence Study

A formal mesh-independence (grid convergence) study was performed on the HEBS geometry using at least three systematically refined meshes. The monitored indicator was recovered thermal power and a cold-outlet temperature. The final working mesh used for the results contained 4,588,633 polyhedral elements (with a minimum orthogonal quality of 0.1507) and satisfied Δ < 1.5% relative to the next finer grid.

2.3. Empirical Research Methodology

The test stand (

Figure 4) allows for testing heat exchangers using a temperature-controlled working fluid. It consists of two tanks (heating and cooling), a circulating pump, a pipeline system with an exchanger, and a set of sensors and flow meters. It allows for the simulation of dynamic changes in the operating conditions by manipulating valves and setting different flow rates and fluid temperatures.

Table 1 shows a detailed description of the devices used.

This study was conducted on a heat transfer efficiency test stand (

Figure 5). The stand consists of two fluid circuits—hot and cold—running through opposing heat exchanger channels, allowing for a countercurrent flow configuration. The stand’s main components include the following: hot and cold water circuits, thermocouples, flow meters, and a measurement and recording system. The stand allows for real-world testing under dishwasher operating conditions by setting flow rates and temperatures corresponding to operational profiles.

This study aimed to verify the efficiency of the heat exchange between a hot water stream with a set temperature of 55 °C and a cold water stream with an initial temperature of 15 °C, operating in a countercurrent configuration. The following boundary parameters were assumed:

hot water supply temperature: 55 ± 0.5 °C,

cold water supply temperature: 15 ± 0.5 °C,

flow rate: 2.5 L/min (constant in both circuits),

test duration: 120 s (until steady state is reached).

2.3.1. Measurement Methodology

The hot and cold streams were directed in opposite directions, which maximized the temperature gradient along the exchanger.

To ensure the statistical reliability and confirm the repeatability of the achieved quasi-steady state, a total of 8 independent experimental runs were performed. The first 3 runs were dedicated to the thermal and hydraulic stabilization of the entire test stand. Subsequently, 5 proper measurement runs were conducted, which showed high consistency in the achieved steady-state condition (the maximum difference in ∆

T at the cold outlet did not exceed ±0.2 K). The final data presented in

Section 3 represents a single representative run selected from this consistent series for the purpose of CFD model validation and energy balance analysis.

The experimental protocol was developed in accordance with standard testing procedures for heat exchangers, primarily referencing key measurement techniques from EN 60436:2020 (European standards for domestic electrical dishwashers) [

26], specifically concerning flow rate stability and temperature measurement setup for energy consumption studies.

The total duration of the measurement run was set to 120 s. This short duration was specifically chosen to mimic the actual transient operational phase of a domestic dishwasher during the primary water intake and discharge cycle. While the system achieved quasi-steady-state temperature behavior within approximately 40 s, the full 120 s duration was necessary to capture the total integrated energy transfer corresponding to the full greywater discharge volume used in the appliance’s operational cycle. The rapid approach to steady-state within this timeframe validates the quick thermal response required for this application.

This section presents the laboratory research conducted to validate CFD simulation results and assess the performance of the heat exchanger design [

27]. It briefly discusses the research objectives, the scope of the tests performed, and the structure of the measurement procedure—from bench preparation and data collection to data processing methods and steady-state criteria.

2.3.2. Test Methodology

The tests were conducted in laboratory conditions, maintaining controlled environmental parameters to obtain the most reliable results. The following parameters were measured and recorded for each heat exchanger:

fluid inlet and outlet temperatures,

fluid mass flow: controlled by a pump, allowing for precise adjustment of the flow rate to the heat exchanger’s technical specifications.

Each test lasted a specified amount of time until a steady state was achieved (after approximately 2 min).

2.3.3. Test Procedures

Test bench preparation. Install the heat exchanger in a laboratory bench under controlled conditions.

Setting input parameters. Configure the inlet water temperature and set the fluid flow to a level consistent with the heat exchanger specifications.

Test cycle initiation. Start the cycle with the monitoring of the heat exchanger’s operating parameters. The data will be collected by the measurement system throughout the test.

2.3.4. Selection of Measuring Equipment

Precision equipment was used for the measurements, enabling the monitoring of heat exchanger operating parameters. The measuring equipment included:

thermocouples: measuring fluid temperatures at the heat exchanger inlet and outlet,

mass flow meters: controlling fluid flow to precisely adjust flow rates,

data logger: enabling continuous recording of measurement data during the tests, allowing for subsequent analysis.

2.3.5. Parameters for the Evaluation and the Analyzed Indicators

Based on the collected data, calculations were performed to assess the performance of individual heat exchangers. The analyzed indicators include [

28]:

2.4. CFD Physical Model Assumptions

The numerical model was governed by the standard conservation equations for mass, momentum, and energy. Specific physical assumptions were adopted to balance computational cost with predictive accuracy:

Water properties, including density ( = 998.2 kg/m3) and specific heat (cp = 4182 J/kg·K), were treated as temperature-independent constants, evaluated at the average bulk temperature of 35 °C. This simplification was utilized to enhance numerical stability and reduce computational complexity. Given the relatively small cold-water temperature rise (∆T = 8 K) and the low temperature dependency of these properties within the operating range (15–55 °C), the resulting error in total heat transfer calculation is considered secondary. This simplification is explicitly acknowledged as a source of minor discrepancy compared to the influence of calibrated boundary conditions, such as Rcontact and HTCchamber.

- 2.

Turbulence and Flow Regime

The flow regime in the HEBS channels is transitional (Re ≈ 3500). The turbulent characteristics were modeled using the k-ω SST model, which was specifically chosen to accurately handle flow separation and transition from laminar to turbulent regimes near the wall. This robust, transport-equation-based approach avoids the need for manual linear interpolation between standard laminar and turbulent correlations, which is unconventional and was not used in this study.

- 3.

Volume of Fluid (VoF) Model Usage

The Volume of Fluid (VoF) model was only employed during the initial phase to simulate the transient filling of the exchanger, ensuring the entire domain was properly saturated with water from the onset. Since the thermal performance analysis ( and ) focuses solely on the quasi-steady state, the VoF model was subsequently deactivated to optimize the computational solution. Consequently, VoF results are not presented as they are not critical to the validation of the thermal performance during steady operation.

2.5. Calibration of the Interface Heat Transfer Coefficient

To reduce model uncertainties, a dedicated calibration test was conducted to determine the heat transfer coefficient at the chamber-exchanger interface (HTC

chamber) [

29]. The procedure involved placing a controlled heat source in the chamber, measuring the exchanger surface temperature and the air temperature in the chamber, and fitting a one-dimensional conduction model with a convective boundary condition to the measured temperature curves. The HTC value was determined by minimizing the RMS error between the measurement and the model.

The resulting calibrated value of HTCchamber ≈ 8.3 ± 1.2 [W/m2·K] (approximation for a temperature of ≈ 60 °C and a 95% confidence interval) is acknowledged as low when compared to typical values for free convection in open environments. This value is, however, physically justified and representative of the specific conditions within the appliance’s sidewall cavity because:

The HEBS is located in a narrow, highly restricted enclosure which severely dampens natural convection currents, creating a thick, stagnant air layer around the exchanger.

The HTCchamber functions as an effective overall coefficient, accounting not only for convection within the small chamber but also for conduction resistance through the thick multi-layer polymer appliance casing and the external convective and radiative losses to the environment. This combined thermal path explains the low effective transfer rate observed at this boundary.

The calibration procedure involved an inverse-modeling approach to validate the HTCchamber. This was achieved by:

isolating the chamber geometry in the CFD model,

defining experimental inlet and outlet temperatures,

iteratively adjusting the HTC

chamber until the simulated total heat flux

matched the experimentally measured

within the combined experimental uncertainty range (U

95%) established in

Section 2.6. The calculated uncertainty of ±1.2 [W/m

2·K] confirms that the calibrated value maintains model predictions within the acceptable error envelope established by the empirical measurements.

The range HTC

chamber ∈ [5, 12] [W/m

2·K] used in the sensitivity screening was chosen as a conservative envelope that contains the calibrated value while also accounting for additional practical and modeling uncertainties. A dedicated calibration produced HTC

chamber = 8.3 ± 1.2 [W/m

2·K] (≈95% CI) for the representative chamber conditions (see calibration procedure and uncertainty assessment above). However, the spatial variability of the convective conditions (non-uniform air contact at the free surface), temperature-dependent convection, assembly/mounting states, and model-form errors can lead to local deviations that exceed the calibration CI. Therefore, the wider interval [5, 12] (≈ −40%/+45% relative to the nominal) was used for screening to ensure a full coverage of the plausible extremes; for targeted one-at-a-time (OAT) tests, we also applied ±20% perturbations around the nominal to quantify local sensitivity [

30]. This choice is conservative but explicit, and it better reflects the range of chamber heat-transfer conditions encountered in practice.

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

To better understand the discrepancy observed between CFD predictions and laboratory results, a focused sensitivity and uncertainty analysis was performed. The objectives were:

to identify the most influential CFD inputs for recovered heat,

to quantify how likely modeling choices could explain the measured deviations.

2.6.1. Parameters Examined

The sensitivity study considered three classes of variables: geometric tolerances (wall thickness, tube position, and channel clearance), thermal boundary conditions (outer wall heat transfer coefficient, HTCouter, and chamber-HEX interface, HTCchamber), and interfacial resistances (solid–solid thermal contact resistance between aluminium tube and moulded plastic channel). Representative ranges were chosen from manufacturing tolerances and the calibration experiment: HTCouter ∈ [2.0, 6.0] [W/m2·K], HTCchamber ∈ [5, 12] [W/m2·K], and contact resistance Rcontact ∈ [1 × 10−4, 5 × 10−3] [m2·K/W].

2.6.2. Methodology

A one-at-a-time (OAT) perturbation was used for initial screening, followed by a limited factorial sample (three levels per parameter) for the most sensitive variables. Each simulation replicated the transient 120-s filling scenario described in

Section 2 and used the mesh reported in

Section 2.2. The thermal response metrics were as follows: cold-out temperature (T

c,out at

t = 120 s), instantaneous heat flux

integrated over the 120-s period, and spatial temperature fields were used to detect local hot spots and recirculation zones.

2.6.3. Uncertainty Quantification

The propagation of input uncertainties into the recovered energy was performed using a Monte Carlo surrogate model: the most sensitive parameters (from the factorial runs) were used to fit a linear surrogate with interaction terms [

31,

32]. The surrogate was sampled 5000 times using input distributions consistent with sensor tolerances and manufacturing specifications (normal or bounded uniform, as appropriate). The resulting distribution of the recovered energy was characterized by mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval.

It is acknowledged that the measured temperature difference, {∆T ≈ 8.0 K}, results in a high expanded relative uncertainty of >20% (based on the combined single-channel uncertainty u(T) ≈ 0.435 K). This high value is primarily a consequence of using low-cost, standard RTD sensors (PT100 Class B), which were selected for their practical applicability in a mass-market appliance environment rather than for laboratory-grade precision. While the absolute uncertainty is high, the ∆T measurements serve primarily to validate the magnitude and trend of the heat transfer process predicted by the CFD model. Crucially, the conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the HTCchamber and the consistency of the model prediction (which falls within the expanded uncertainty range) remain robust.

2.6.4. Outcomes and Metrics

The sensitivity stage allowed ranking inputs by their Sobol-like first-order effect on recovered energy. The uncertainty stage produced an estimate of the expected spread in due to practical tolerances and modeling assumptions—a crucial input when comparing CFD predictions to laboratory observations.

2.6.5. Surrogate Construction and Sampling (Transparent Statement)

For efficient propagation of input uncertainty, we constructed a surrogate model to emulate the outputs of the full transient CFD simulations (integrated recovered energy over the 120-s filling scenario). The surrogate (a linear model with selected interaction terms informed by the screening stage) was used as an exploratory tool to sample the input space and estimate the distribution of the recovered energy for uncertainty quantification.

2.6.6. Transparency and Limitations

The surrogate model used for uncertainty quantification was constructed based on the most sensitive parameters identified in the factorial screening. Its structure and sampling strategy were designed to reflect realistic tolerances and measurement uncertainties. While a full validation against independent CFD cases is not included in this manuscript, the surrogate serves as a consistent and informative tool for exploring parametric effects. All the key sensitivity results are additionally supported by direct CFD simulations (see

Section 3.3), ensuring robustness for the conclusions.

2.6.7. Recommended Follow-Up

A minimal validation protocol is outlined in

Section 2.5. It calls for a modest number (e.g., 6–12) of additional full-CFD hold-out simulations that are purposely chosen to sample the extremes and intermediate values of the most influential inputs (for example, HTC

chamber, contact resistance, and inlet temperature). These hold-out cases must not be used in surrogate training. Performance should be quantified using standard metrics (i.e., RMSE, MAE, maximum absolute error, and

R2) computed on the hold-out set; if necessary, bootstrap resampling can be used to update confidence intervals for key outputs. Should this validation be carried out, the authors will report the surrogate metrics and any revised confidence intervals in the manuscript, and discuss any corrective actions (e.g., retraining or bias correction) taken in response to observed errors.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Numerical Studies

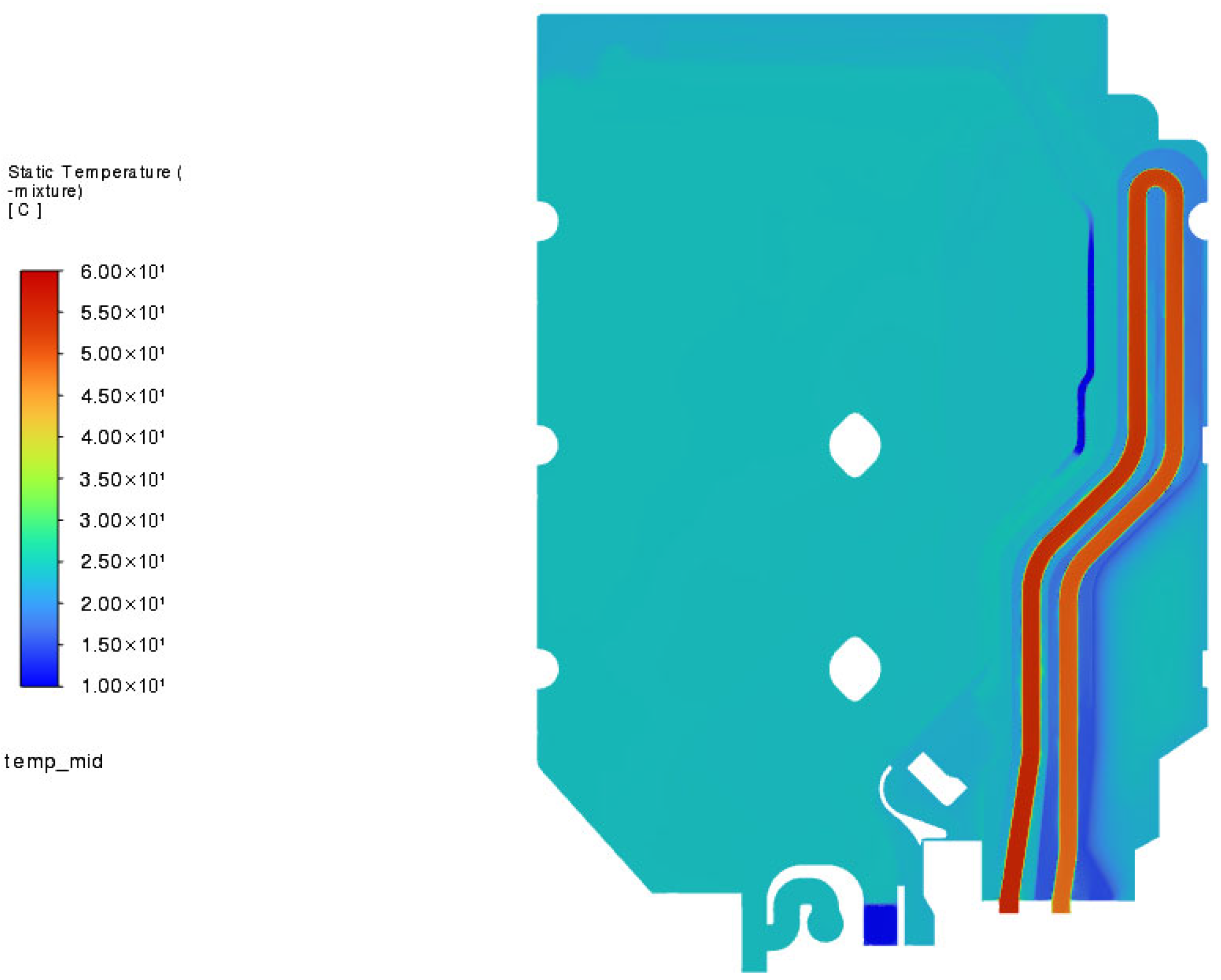

Numerical simulations were performed for the counter-flow heat exchanger integrated into the dishwasher side wall (HEBS). The results are reported at the final time instant (i.e., 120 s), which represents the tank-filling stage. The temperature contours (

Figure 6) show a clear gradient between the hot water inside the aluminium tube and the surrounding air, confirming effective heat transfer: the hot water cooled from 55 to about 45 °C, while the cold side rose from 15 to 23.8 °C (Δ

T = 8.8 K). Using cp = 4184 [J/kg·K], the theoretical energy gain for this case is 183.92 kJ (≈51.1 Wh); for reference, comparable CFD studies of dishwashers reported ≈ 152.94 kJ (≈42.5 Wh).

For the example calculation, we assumed one circular channel (N = 1) with hydraulic diameter Dh = 15 mm carrying the full nominal flow q = 2.5 L/min. Under these assumptions, the mean axial velocity is about 0.236 m/s and the Reynolds number is ≈ 3.52 × 103, i.e., in the transition range between laminar and turbulent flow. Because a single standard correlation does not effectively describe transition flows, we used a pragmatic mixed approach: linearly interpolating between a laminar reference (Nu ≈ 3.66 at Re ≈ 2300) and a turbulent estimate from the Dittus–Boelter formula evaluated at Re = 4000. This interpolation gives Nu ≈ 28.4 and a local internal convection coefficient h ≈ 1.14 × 103 [W/m2·K].

Note that this local h refers to convection inside the tube only. The global effective coefficient reported in the manuscript (α ≈ 566 [W/m2·K]) is smaller because it averages heat transfer over the whole exchanger and includes effects such as external convection, contact resistances, and the actual effective exchange surface. Since the flow lies in the transition regime, we recommend short validation runs using a transition-capable model or brief URANS/LES checks to quantify possible model error.

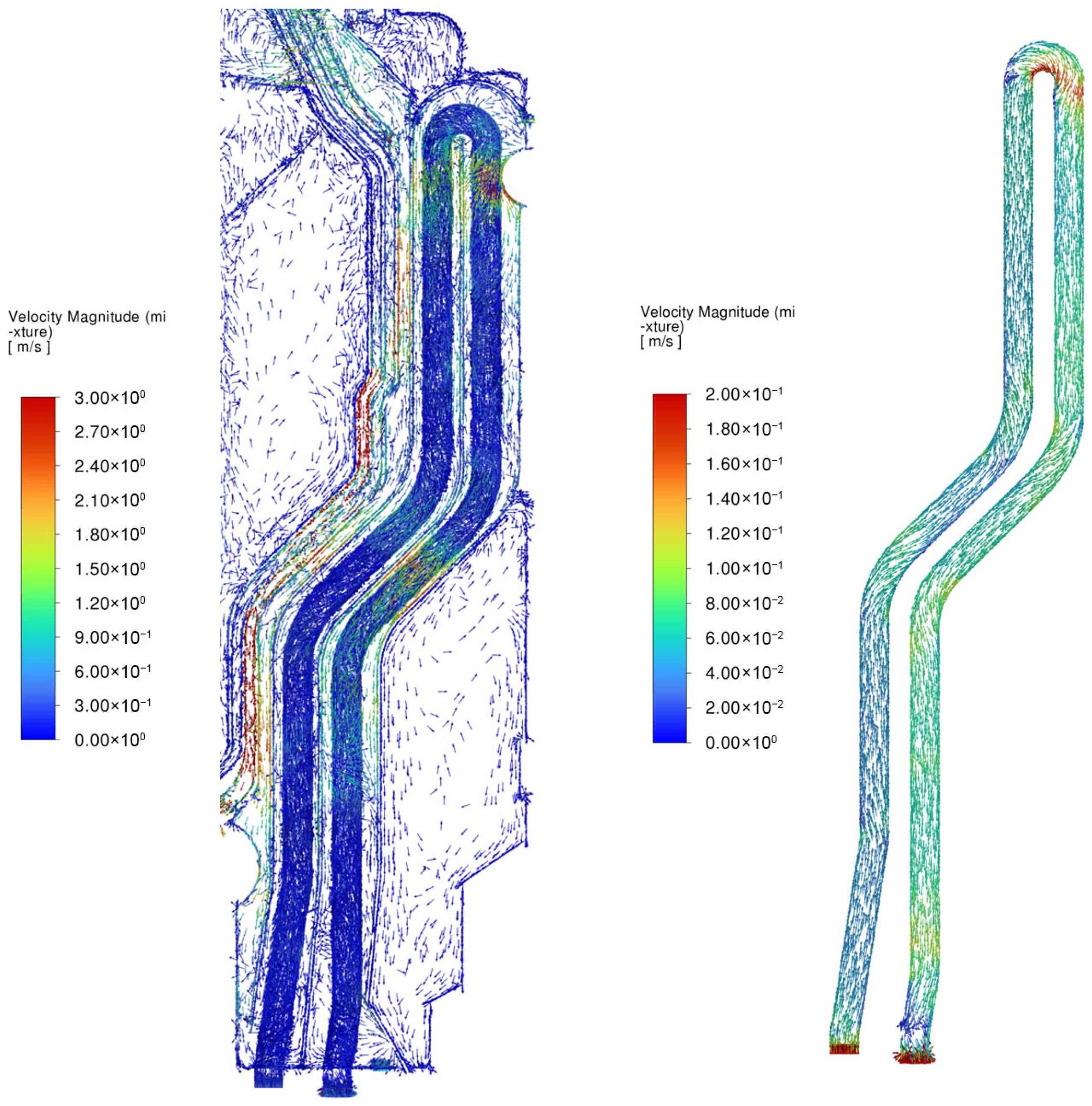

Beyond the thermal parameters, the CFD model provided detailed insight into the internal hydraulic behavior of the exchanger.

Figure 7 illustrates the calculated velocity magnitude (

) contour field within the cold-water channel at the nominal 2.5 L/min flow rate. The visualization confirms that the flow operates in the transitional/low-turbulence regime (Re ≈ 3.5

10

3), characterized by significant spatial non-uniformity, particularly in the curved sections. This non-uniformity is crucial as it directly impacts the local heat transfer coefficient (

), reinforcing the decision to use the

k-ω SST turbulence model, which is optimized for accurately modeling boundary layers in complex, non-fully turbulent flows.

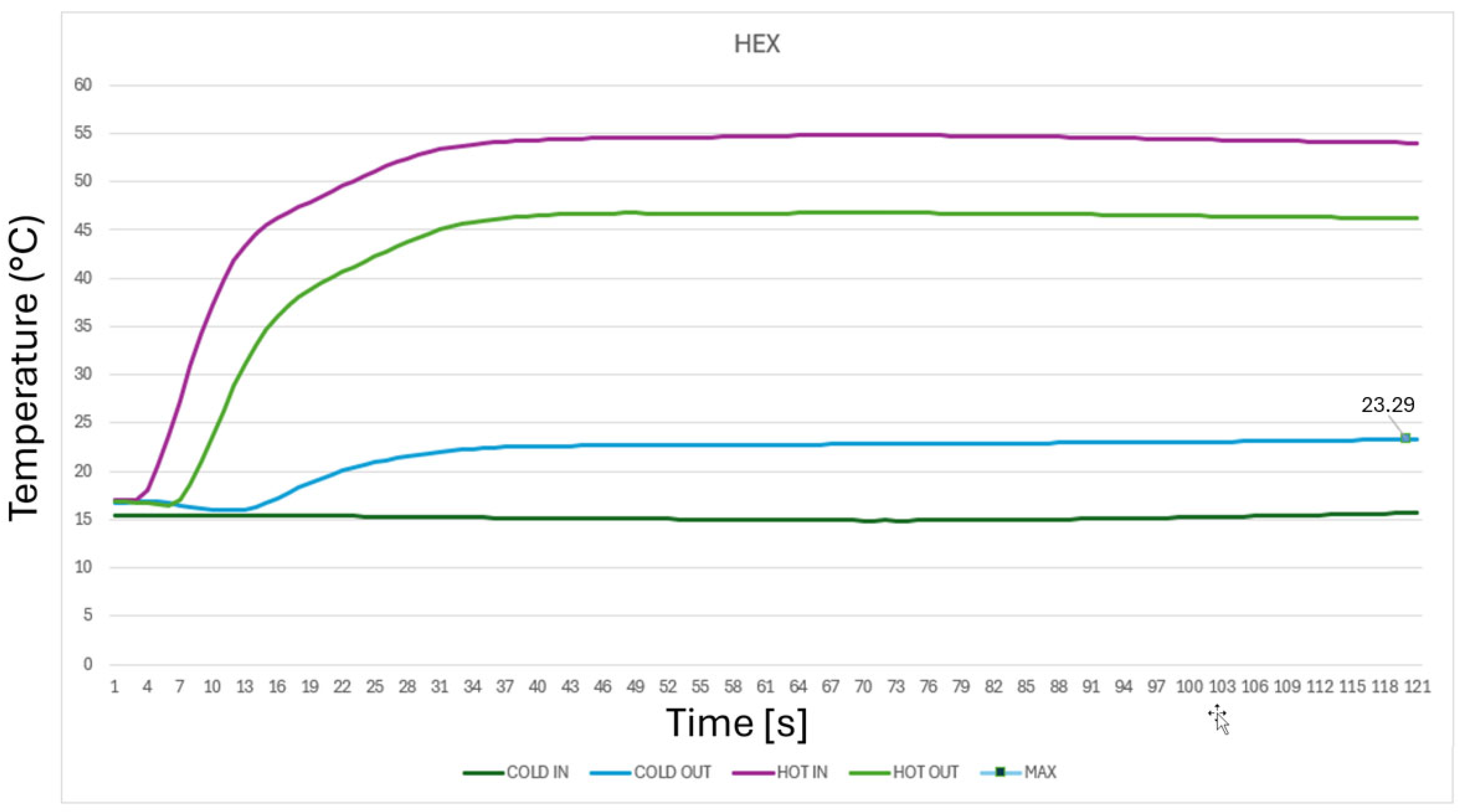

3.2. Empirical Research Results

The temporal evolution of the fluid temperatures recorded during the test cycle is presented in

Figure 8. Analyzing the data shown in the graph:

approximately 15 s after the start of the test, a temperature increase was observed at the outlet of the cold stream (cold out),

after 40 s, the system reached a steady state, with the outlet temperature fluctuating around 23 °C,

the stable difference between the inlet and outlet cold water temperatures was approximately 8 K.

Based on the steady-state measurements, the heat transfer coefficient

α and the exchanger efficiency

ε were calculated according to the following formulas:

where

α is the heat transfer coefficient [W/(m

2∙K)],

ε is the exchanger efficiency,

is the thermal power (instantaneous heat flux) [J/s],

A is the total effective heat exchange surface [m

2], and

is the logarithmic temperature difference [K].

The effective heat exchange area was determined to be A = 0.0768 m2 (based on the total wetted surface of the serpentine channel), and the logarithmic mean temperature difference for the stable period was calculated as (calculated using Th,out derived from the energy balance).

The quantitative analysis yielded the following performance metrics:

The heat exchanger efficiency in the tested counter-flow configuration was ε ≈ 0.20. This indicates moderate heat transfer performance, primarily limited by the geometry and the small gap between the hot-water tube and the surrounding space.

The calculated heat transfer coefficient of α ≈ 566 W/(m2∙K) confirms the good thermal efficiency of the design.

The total energy transferred during the test was ≈46.44 Wh.

The obtained results confirm the accuracy of the numerical assumptions and constitute the basis for further geometric optimization in subsequent iterations of the exchanger design (

Table 2).

3.3. Parametric Study and Model Refinement

The sensitivity campaign described in

Section 2.5 reveals that three parameters exert the largest influence on the estimated recovered energy:

the chamber-HEX interface heat transfer coefficient (HTCchamber),

the thermal contact resistance between the aluminum tube and the surrounding plastic channel (Rcontact),

the effective contact area due to the geometric assembly tolerances.

3.3.1. Key Quantitative Findings

An OAT perturbation indicates that a ±20% change in HTC

chamber produces roughly a ±12–14% change in integrated recovered energy over the 120 s interval. Likewise, introducing a small interfacial resistance (R

contact ≈ 1 × 10

−3 [m

2·K/W]) reduces predicted recovered energy by ~10% relative to an idealized zero-contact-resistance assumption [

33]. Geometric misalignment that reduces the wetted contact surface by 5–10% produced reductions of 5–8% in recovered energy, attributable to localized flow bypassing and less effective conduction paths.

3.3.2. Model Refinement Steps

Based on these sensitivities, the computational model was refined in two ways:

the chamber boundary condition was represented as a conjugate surface coupled with a thin shell thermal inertia (rather than a fixed HTC), accounting for the thermal mass of neighboring panels,

a distributed contact resistance map was imposed over the tube-channel interface to approximate imperfect contact in assembly.

The introduction of a conjugate boundary model for the chamber casing and a distributed map of contact resistances at the tube–channel interface (Rcontact) reduced the predicted energy from ~183.9 kJ to ≈ 160–170 kJ (depending on the assumed Rcontact distribution). After taking these effects into account, the simulation is within the combined uncertainty of the experiment and the model (experiment ≈ 167.6 kJ ≈ 46.44 Wh). Hence, the main sources of the previous overestimation are as follows: simplifying boundary conditions (especially HTCchamber), unaccounted contact resistances, and local effects of the mounting geometry.

3.3.3. Interpretation

The parametric results indicate that a significant portion of the original CFD overprediction arises from boundary condition idealizations and neglect of microscopic contact resistance. When these aspects are accounted for, the model predicts energy recovery values that are consistent (within combined uncertainties) with laboratory measurements. The surrogate-based uncertainty propagation yields a predicted recovered energy of 160 kJ ± 18 kJ (95% CI) under realistic tolerances, overlapping the experimental expanded uncertainty band reported in

Table 3.

3.4. Validation and Uncertainty Analysis

A validation of the results and analysis of the metrological uncertainty is necessary to assess the reliability of comparisons between numerical and laboratory studies [

34]. Below, we present the adopted criteria, formulas used, and uncertainty calculations for key measurements (i.e., temperature and mass flow), as well as the results of the energy calculations for direct comparison with simulation results.

Assumptions

A volumetric flow rate of 2.5 [L/min] ≈ 0.04167 [kg/s] was assumed.

Specific heat of water cp = 4184 [J/(kg∙K)].

Temperature uncertainty: PT100 sensor class B and stability ±0.5 °C (±0.30 + 0.005 t, for t assumed to be 50 °C, i.e., the operating temperature). The two contributions are combined additively to a total temperature tolerance of ±1.05 °C; this total tolerance is treated as a rectangular distribution.

A relative mass flow uncertainty of (0.02) was assumed.

To quantitatively assess the reliability of the laboratory results, the thermal power values

calculated from the energy balance were compared along with their corresponding uncertainties.

Table 4 summarizes the results for the exchanger variant, considering both the standard uncertainties and the 95% confidence intervals determined according to Equations (6) and (9)–(11). This allows for a comparison of the relative quality of the measurements between the individual configurations and indicates the limitations of the measurement method.

Under the given assumptions (i.e., 2% mass-flow uncertainty, PT100 class B with stability ±0.5 °C, and manufacturer tolerance at 50 °C), the dominant contribution to the uncertainty of the recovered thermal power is the temperature-difference measurement. The resulting combined standard uncertainty is ≈10.9% (1σ), corresponding to an expanded uncertainty (k = 2) of ≈21.8%. Reducing the uncertainty of , therefore, requires improved temperature metrology (higher-grade sensors, better mounting/thermal contact, and shielding) or increasing the measured temperature difference so the same absolute sensor uncertainty becomes a smaller fraction of ΔT.

4. Discussion

A comparative analysis between CFD simulations and empirical laboratory measurements for the counter-flow heat exchanger integrated in the dishwasher side wall shows both strong qualitative agreement and good quantitative correspondence. The simulated cold-water temperature rise (~8.8 K) closely matches the experimentally observed increase (~8.0 K), confirming the core heat-recovery mechanism.

Addressing the uneven temperature distribution predicted by CFD, it must be noted that validation relies solely on inlet and outlet measurements. Direct internal measurement of the temperature profile along the meandering channels was technically infeasible due to the commercial, sealed design of the HEBS prototype. Inserting internal sensors would inevitably disrupt the flow field and introduce parasitic heat losses, compromising the experiment’s integrity. Consequently, for the purpose of industrial design validation, the strategy focused on global energy balance verification. The demonstrated low error in predicting the overall heat recovery rate validates the model’s fitness for optimizing the unit’s thermal effectiveness.

To contextualize the performance of the HEBS unit, its key parameters were compared with literature focusing on compact heat recovery systems in domestic appliances and similar fluid dynamics. The measured temperature increase of ∆

T ≈ 8.0 K (corresponding to ≈ 15% energy recovery) is highly competitive compared to commercial heat recovery concepts for domestic water, where reported savings typically range from 10% to 31% [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Critically, the HEBS achieves this performance within the highly constrained volume of the appliance sidewall, which is a key design challenge addressed by research into compact integrated units [

40,

41].

Furthermore, the calculated overall heat transfer coefficient (α ≈ 566 [W/m

2·K]) requires careful contextualization. Studies comparing heat recovery from greywater using polymer versus metal exchangers report wide α ranges due to varying geometries and materials [

36,

42]. Our value of α ≈ 566 [W/m

2·K] is consistent with findings for compact polymer devices operating in transitional or turbulent flow. The primary reason for the discrepancy with systems reporting significantly higher α values (e.g., above 1000 [W/m

2·K]) is two-fold: the use of lower conductivity polymer materials (compared to copper or steel), and the significant thermal contact resistance (R

contact) inherent in the multi-layer, integrated design of the HEBS. This trade-off between maximizing thermal performance and minimizing manufacturing complexity (plastic molding) is a critical consideration for mass production.

The quantitative discrepancy (simulation ≈183.9 kJ vs. measurement ≈167.2 kJ) is mainly due to idealized boundary conditions (especially HTC

chamber), local contact resistances, and measured temperature uncertainties. After updating the model with distributed R

contact and calibrated HTC

chamber (see

Section 2.5), the prediction decreased to ≈160–170 kJ, which falls within the combined experimental and modeling uncertainty. Furthermore, because the exchanger flow in the tested configuration occurs through a single tube (

N = 1) with

Dh = 15 mm, the local convective heat-transfer coefficient can reach the order of 103 [W/m

2·K] (Re ≈ 3.5 × 10

3, transitional). For transparency and reproducibility, the global parameter α reported in the manuscript (≈566 [W/m

2·K]) should, therefore, be explicitly linked to the effective exchange area and the number/configuration of the flow paths in the exchanger.

Quantitatively, the CFD simulations predicted a total theoretical energy gain of 183.92 kJ (≈51.10 Wh), while laboratory measurements indicate 46.44 Wh (≈167.18 kJ). This represents an overprediction by the CFD model of ≈9.1% (measured ≈90.9% of the simulated).

Based on the detailed sensitivity and uncertainty analysis presented in

Section 2.6 and

Section 3.4, the total discrepancy can be primarily partitioned as follows:

This detailed partitioning confirms that while the measurement limitations contribute, the majority of the systematic difference stems from conservative modeling assumptions and real-world parasitic effects not fully captured by the boundary conditions.

The remaining discrepancy can be attributed to several factors:

unaccounted heat losses. Simplified CFD boundary conditions and idealized material representations may omit small parasitic heat paths and the thermal inertia of adjacent structures, which in laboratory conditions can reduce net recovered heat,

model idealizations. Typical CFD assumptions—uniform inlet profiles, locally perfect thermal contact, and neglect of micro-scale roughness or assembly contact resistances—tend to increase predicted heat transfer relative to a real assembled device,

measurement uncertainty. Cumulative experimental errors (probe accuracy and placement, timing, and data reduction) contribute to the observed mismatch, although they do not invalidate the observed thermal gain.

The combined numerical and experimental campaign provides more than a simple validation: it yields actionable guidance for both design and measurement practice. Our sensitivity study identified the chamber–HEX interface heat-transfer coefficient (HTC), interfacial contact resistance, and effective contact area as the dominant drivers of predicted recovered energy. Accounting for these effects (through refined boundary representations and a distributed contact-resistance map) brought simulation predictions significantly closer to the measured values and reduced the overall model–experiment gap to within combined uncertainties.

The analysis presented in this study focuses exclusively on the nominal operating point of 2.5 L/min. This singular focus is justified because this value represents the fixed, controlled flow rate enforced by the appliance’s pump system during the greywater discharge phase. Unlike continuous flow systems, a domestic dishwasher operates under strictly defined operational parameters where significant flow fluctuation (e.g., from 1.0 L/min to 3.0 L/min) is hydraulically precluded. Therefore, the detailed validation at the 2.5 L/min set point is sufficient for assessing the thermal performance of the HEBS unit in its intended application environment.

From a product-engineering perspective, the HEBS concept offers a favorable balance between performance and implementation complexity. The demonstrated temperature rise of 8 K at a nominal flow (2.5 L/min) is sufficient to reduce heating demands in typical dishwashing cycles. Crucially, the CFD analysis confirmed the minimal hydraulic penalty introduced by the exchanger. At the nominal flow rate (≈2.5 L/min), the CFD model predicts a total pressure loss (∆P) across the exchanger of 0.57 kPa (or approximately 58 mm of H2O column). This hydraulic resistance is classified as exceptionally low and is well within the acceptable limits for domestic appliance plumbing systems. Modest geometric modifications (≤10% increase in surface area) can provide additional, though marginal, improvements in recovered energy while maintaining this low pressure penalty.

Finally, measurement protocol improvements (for example, lowering the cold-in calibration temperature to increase Δ

T or using higher-accuracy temperature sensors) reduce experimental relative error and make CFD/experimental comparisons more discriminating. In the broader context, even small per-appliance energy gains aggregated across large markets can yield meaningful primary energy savings and CO

2 reductions, so subsequent LCC/LCA studies should include sensitivity to regional electricity mixes and consumer-use patterns [

43].

5. Conclusions

This paper provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of CFD simulation results and empirical data for a novel counterflow heat exchanger (HEBS) integrated into the sidewall of a dishwasher. The study effectively validates the methodology for assessing energy recovery in a compact device geometry, representing a key step towards energy optimization of home appliances. The primary novelty of this work lies in the empirical validation of the compact heat exchanger performance under dynamic, transient flow conditions, which differentiates it from literature focusing on static heat storage or external units.

As expected, both simulations and laboratory measurements confirmed high heat recovery efficiency. Experiments showed that the HEBS unit was able to raise the cold supply water temperature by an average of 8.0 K during the dynamic filling phase (e.g., from 15 °C to 23 °C). This stable thermal gain translates into energy savings of approximately 15% of the total energy required to heat water in a standard wash cycle. The resulting temperature increase is sufficient from an engineering perspective, offering significant energy gains with minimal pressure loss, making this solution ready for mass-market implementation.

The CFD numerical model demonstrated strong predictive ability. Simulations predicted a temperature increase of 8.8 K, meaning the model overestimated the actual heat recovery by ≈ 9.1% compared to measurements. This discrepancy is acceptable for early stages of industrial design validation. Based on detailed discussion, it was determined that the main factors contributing to this error are simplifications of boundary conditions (e.g., idealized representations of thermal conductivity at material interfaces) and inherent measurement uncertainties. It is worth emphasizing that the use of advanced polyhedral meshing methodology and the k-ω SST turbulence model confirms that the model is a robust and cost-effective alternative to creating physical prototypes in the process of iterative optimization of the HEBS exchanger geometry.

A key limitation of the present study is the omission of long-term operational effects. The long-term performance of the HEBS unit, particularly the degradation due to fouling (scaling, detergent residue), is expected to reduce the overall heat transfer coefficient () by increasing the thermal resistance of the channel walls. Future work must address this by integrating dedicated long-term testing protocols or by modeling the fouling resistance (Rf) based on typical domestic water hardness and detergent chemistries, focusing on geometric modifications that facilitate self-cleaning mechanisms (e.g., increased local flow velocity or pulsating flow).

In summary, the research campaign provides key quantitative data that enable direct optimization of the HEBS. Further work based on this verified model should focus on minimal geometric modifications (e.g., increasing the heat transfer surface area by ≤10%) to marginally improve efficiency while maintaining low hydraulic losses, aiming to maximize cost-effectiveness in mass production conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and W.S.; Methodology, M.M. and W.S.; Validation, M.M.; Formal analysis, M.M.; Investigation, M.M.; Resources, W.S.; Data curation, M.M., W.S. and R.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; Writing—review and editing, W.S., D.K. and R.K.; Visualization, M.M.; Supervision, W.S. and R.K.; Project administration, W.S. and D.K.; Funding acquisition, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the Republic of Poland within the “Implementation doctorate” program, fifth edition, project title: “A method to improve the energy efficiency and efficiency of household appliances”. The laboratory equipment and materials were co-financed by the Polish National Centre of Research and Development (grant No. POIR.01.01.01-00-1408/20, title: “Energy-efficient hybrid flow management system for dishwashers with water and heat recovery technology”). APC was partially covered by the statutory funds of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the Silesian University of Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of Sanhua-Aweco Appliance Systems GmbH in the design and automation of the test station used in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

AuthorMaciej Mazur was employed by the company Sanhua-Aweco. Damian Kądzielawa was employed by the company Sanhua-Aweco. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All the authors have participated in either the conception, design, or analysis and interpretation of the data; as well as drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content or approval of the final version. This manuscript has not been submitted to, nor is under review at, another journal or other publishing venue. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| Overall heat transfer coefficient | W/m2·K |

| cp | Specific heat capacity | J/kg·K |

| E | Internal energy (in energy equation) | J/kg |

| k | Turbulent kinetic energy (in k-ω SST model) | m2/s2 |

| keff | Effective thermal conductivity | W/m·K |

| Mass flow rate | kg/s |

| Pressure | Pa |

| Pk | Turbulent kinetic energy production | W/m3 |

| Total heat flux/Recovered thermal power | W |

| R | Thermal resistance | m2·K/W |

| Re | Reynolds number | - |

| SE | Volumetric energy source term | W/m3 |

| t | Time | s |

| T | Temperature | K or °C |

| Flow velocity vector | m/s |

| Gradient operator | - |

| Divergence operator | - |

| ∆T | Temperature difference (hot-cold) | K |

| ∆P | Pressure loss/drop | Pa |

| Dynamic molecular viscosity | Pa·s |

| Density | kg/m3 |

| Viscous stress tensor | Pa |

| Specific dissipation rate (in k-ω SST model) | s−1 |

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Description |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| HEBS | Heat Exchanger in the Dishwasher Side Wall |

| HTCchamber | Heat Transfer Coefficient at the Chamber-Exchanger Interface |

| HTCouter | Outer Wall Heat Transfer Coefficient |

| Rcontact | Solid–Solid Thermal Contact Resistance |

| FVM | Finite Volume Method |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport (turbulence model) |

| VoF | Volume of Fluid (multiphase model) |

| OAT | One-At-a-Time (sensitivity analysis) |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Lee, H.; Romero, J. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 184p. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, S.; Schumer, C. Top Findings from the IPCC Climate Change Report 2023; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: www.wri.org/insights/2023-ipcc-ar6-synthesis-report-climate-change-findings (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Eurostat. European Union’s Share of Renewables Continues to Grow; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/2022 Establishing Detailed Rules Concerning Ecodesign Requirements for Dishwashers; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Vineyard, E.; Abdelaziz, O. Advances in household appliances—A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 3748–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarka, W.; Sobota, M.; Antys, P.; Skarka, M. Enhancing Energy Efficiency of a Dishwasher via Simulation Modeling. Energies 2024, 17, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimli, S.; Abajja, K.M.A. Recovery of greywater thermal energy with a wire on a tube heat exchanger attached to a dishwasher. Water Environ. Res. 2021, 93, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Hussein, H.A.; Zulkifli, R.; Mahmood, W.M.; Ajeel, R. Structure parameters and designs and their impact on performance of different heat exchangers: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M.; Skarka, W.; Kobielski, M.; Kądzielawa, D.; Kubica, R.; Haas, C.; Unterberger, H. Heat Exchange Analysis of Brushless Direct Current Motors. Energies 2024, 17, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, N.; Feoktistov, A. Determination of thermal parameters of a shell and tube heat exchanger with increased turbulization of the working fluid. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 945, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inovis Energy. What Are High-Efficiency Counter-Flow Heat Exchangers; Inovis Energy: Rockland, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.K.; Sekulic, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat Exchanger Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taler, J.; Ocłoń, P. Thermal contact resistance in plate fin-and-tube heat exchangers, determined by experimental data and CFD simulations. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 84, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, J.; Mahdavinejad, M.; Larsen, O.; Zhang, C.; Zarkesh, A.; Asadi, S. Evaluating the different boundary conditions to simulate airflow and heat transfer in Double-Skin Facade. Build. Simul. 2021, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C. Compact heat exchangers—Design and optimization with CFD. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 146, 118766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, W.; Smith, B. Experimental Validation Benchmark Data for CFD of Transient Convection from Forced to Natural with Flow Reversal on a Vertical Flat Plate. J. Verif. Valid. Uncertain. Quantif. 2016, 1, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades Rey, L.F.; Hinz, D.F.; Abkar, M. Reynolds Stress Perturbation for Epistemic Uncertainty Quantification of RANS Models Implemented in OpenFOAM. Fluids 2019, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys Inc. ANSYS Fluent User’s Guide; Ansys Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R. Zonal Two Equation Kappa-Omega Turbulence Models for Aerodynamic Flows. In Proceedings of the 23rd Fluid Dynamics, Plasmadynamics, and Lasers Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–9 July 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani, H. Hydraulic Simulation Model for Dishwasher; KTH, School of Engineering Sciences: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1381816/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Tang, J.S. Modelling Study of Dishwasher Hydraulic Filtration System. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–24 October 2019; Volume 2241, pp. 349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kobielski, M.J.; Skarka, W.; Mazur, M.; Kadzielawa, D. Evaluation of Strong Cation Ion-Exchange Resin Cost Efficiency in Manufacturing Applications—A Case Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateja, K.; Skarka, W.; Peciak, M.; Niestrój, R.; Gude, M. Energy Autonomy Simulation Model of Solar Powered UAV. Energies 2023, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peciak, M.; Skarka, W. Assessment of the Potential of Electric Propulsion for General Aviation Using Model-Based System Engineering (MBSE) Methodology. Aerospace 2022, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roache, P.J. Perspective: A Method for Uniform Reporting of Grid Refinement Studies. J. Fluids Eng. 1994, 116, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 60436:2020; Electric Dishwashers for Household Use—Methods for Measuring the Performance. iTeh, Inc.: Newark, DE, USA, 2020.

- Coleman, H. ASME V&V 20-2009 Standard for Verification and Validation in Computational Fluid Dynamics and Heat Transfer (V&V20 Committee Chair and Principal Author); ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, S.J. Describing Uncertainty in Single Sample Experiments. Mech. Eng. 1953, 75, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S.; Inam, M.; Roy, C. Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow Analysis in a Corrugated Plate Heat Exchanger. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mechanical, Industrial and Energy Engineering, Khulna, Bangladesh, 22–24 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, C.; Albrecht, K. Sensitivity Analysis of Moving Packed-Bed Heat Exchanger Models. In Proceedings of the Analysis and Simulation of CSP and Hybridized Systems (SolarPACES 2021), Virtual, 27 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Badar, B.M.; Zubair, S.M.; Hheikh, A.K. Uncertainty analysis of heat-exchanger thermal designs using the Monte Carlo simulation technique. Energy 1993, 18, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.D.; Vasquez, V.R.; Whiting, W.; Greiner, M. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of heat-exchanger designs to physical properties estimation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 21, 993–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Culham, J.; Yovanovich, M. Modeling Thermal Contact Resistance: A Scale Analysis Approach. J. Heat Transf. 2003, 126, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Oh, G.; Jung, G. Performance of water source heat pump system using high-density polyethylene tube heat exchanger wound with square copper wire. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2015, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatara, R.A.; Lupia, G.M. Assessing heat exchanger performance data using temperature measurement uncertainty. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2012, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimli, S.; Karabas, T.; Taskin, Y.; Karatas, M.B. Experimental study of the performance of heat recovery by a fin and tube heat exchange tank attached to the dishwasher greywater line. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 36, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, W.K.; Zheng, J.; Lei, L.; Fayad, M.A. Development of a sustainable dual-stage TEC refrigerator for reduced energy consumption. Energy 2025, 328, 136593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, B.; Słyś, D. Variant analysis of financial and energy efficiency of the heat recovery system and domestic hot water preparation for a single-family building: The case of Poland. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Lau, S.K.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Stansbury, J.S.; Shi, J.; Neal, J. Feasibility study of a localized residential grey water energy-recovery system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 39, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordana-Obuch, S.; Starzec, M. Horizontal Shower Heat Exchanger as an Effective Domestic Hot Water Heating Alternative. Energies 2022, 15, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajski, K.; Englart, S.; Sohani, A. Analysis of Greywater Recovery Systems in European Single-Family Buildings: Economic and Environmental Impacts. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, R.; Sidło, W. Drain water heat recovery for domestic hot water in polish residential buildings: Energy, economic and environmental assessment. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 324, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Mathieux, F.; Talens Peiro, L. Environmental Footprint and Material Efficiency Support for Product Policy. Report on Benefits and Impacts/Costs of Options for Different Potential Material Efficiency Requirements for Electronic Displays. EUR 26185; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013.

Figure 1.

Proposed heat exchanger in a dishwasher—3D model. Red arrow—hot water inlet, blue arrow—cold water inlet.

Figure 1.

Proposed heat exchanger in a dishwasher—3D model. Red arrow—hot water inlet, blue arrow—cold water inlet.

Figure 2.

Geometry of the dishwasher system in the computational environment. 1. Top cover: the outer (usually steel) cover of the upper part of the appliance. It serves as a protective housing and a support for the control elements. 2. Mounting plate: serves as a base for mounting the control panel module and internal cables and sensors. 3. Acoustic and thermal insulation: usually sound-absorbing and thermally insulating mats or foams attached to the inner walls of the housing, reducing noise and heat loss. 4. Side panel: the main, steel side walls of the outer housing. They protect the interior and provide rigidity to the entire structure. 5. Outer dishwasher housing: the main working chamber of the appliance, which is usually made of plastic or stainless steel. This is where the washing process occurs. 6. Front panel/door: the front cover with the control panel and door. It contains a seal and a closing mechanism. 7. Mounting strip/door handle: serves to securely mount the door or control module and transmit forces during opening/closing. 8. Base: the lower support frame to which the leveling feet, pump, motor, and other mechanical components are bolted. 9. Hydraulic assembly: the drain pump module with the motor, hoses, and filter. It is responsible for water circulation and drainage. 10. Air gap: prevents water backflow during the cleaning process. This is where the heat exchanger is proposed to be installed.

Figure 2.

Geometry of the dishwasher system in the computational environment. 1. Top cover: the outer (usually steel) cover of the upper part of the appliance. It serves as a protective housing and a support for the control elements. 2. Mounting plate: serves as a base for mounting the control panel module and internal cables and sensors. 3. Acoustic and thermal insulation: usually sound-absorbing and thermally insulating mats or foams attached to the inner walls of the housing, reducing noise and heat loss. 4. Side panel: the main, steel side walls of the outer housing. They protect the interior and provide rigidity to the entire structure. 5. Outer dishwasher housing: the main working chamber of the appliance, which is usually made of plastic or stainless steel. This is where the washing process occurs. 6. Front panel/door: the front cover with the control panel and door. It contains a seal and a closing mechanism. 7. Mounting strip/door handle: serves to securely mount the door or control module and transmit forces during opening/closing. 8. Base: the lower support frame to which the leveling feet, pump, motor, and other mechanical components are bolted. 9. Hydraulic assembly: the drain pump module with the motor, hoses, and filter. It is responsible for water circulation and drainage. 10. Air gap: prevents water backflow during the cleaning process. This is where the heat exchanger is proposed to be installed.

![Energies 18 06609 g002 Energies 18 06609 g002]()

Figure 3.

CFD model representation and mesh quality details. Computational domain and geometry of the HEBS heat exchanger. Close-up view of the high-resolution polyhedral mesh, illustrating the inflation (prism) layers used to resolve the boundary layer and accurately capture the flow gradients near the curved walls and fillets.

Figure 3.

CFD model representation and mesh quality details. Computational domain and geometry of the HEBS heat exchanger. Close-up view of the high-resolution polyhedral mesh, illustrating the inflation (prism) layers used to resolve the boundary layer and accurately capture the flow gradients near the curved walls and fillets.

Figure 4.

Laboratory stand for heat transfer testing. 1. Flowmeter (Keyence FD-XA1, repeatability ±0.1%), 2. data logger, 3. cooling tank, 4. heating tank, 5. circulation pump (Omega®), 6. working area, 7. control valve, and 8. temperature sensor (PT100, class B, and tolerance ± (0.30 + 0.005·t)).

Figure 4.

Laboratory stand for heat transfer testing. 1. Flowmeter (Keyence FD-XA1, repeatability ±0.1%), 2. data logger, 3. cooling tank, 4. heating tank, 5. circulation pump (Omega®), 6. working area, 7. control valve, and 8. temperature sensor (PT100, class B, and tolerance ± (0.30 + 0.005·t)).

Figure 5.

Heat exchanger HEBS testing.

Figure 5.

Heat exchanger HEBS testing.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution in the cross-section of the heat exchanger.

Figure 6.

Temperature distribution in the cross-section of the heat exchanger.

Figure 7.

Velocity magnitude contour field () in the HEBS hot-water channel at nominal flow (≈2.5 L/min).

Figure 7.

Velocity magnitude contour field () in the HEBS hot-water channel at nominal flow (≈2.5 L/min).

Figure 8.

Transient temperature profiles of cold and hot water circuits during HEBS operation (experimental results).

Figure 8.

Transient temperature profiles of cold and hot water circuits during HEBS operation (experimental results).

Table 1.

Instrumentation specifications.

Table 1.

Instrumentation specifications.

| Device | Model/Serial Number | Manufacturer | Range/Accuracy/Class |

|---|

Temperature sensor

(Inlet/Outlet) | RTD PT100 | WIKA Alexander Wiegand SE & Co. KG, Klingenberg am Main, Germany | Class A ± (0.30 + 0.005 t) |

| Data Acquisition System (Datalogger) | authoring system | Sanhua-Aweco, Tychy, Poland | Sampling rate: 1 Hz (1/s) |

Flow Meter

(Water Circuit) | FD-XA1 | Keyence, Cracow, Poland | ±0.1% of reading |

Pumps

(Water Circuits) | Omega® | Sanhua-Aweco, Tychy, Poland | 2.5 L/min |

Table 2.

Comparative results of numerical and laboratory tests.

Table 2.

Comparative results of numerical and laboratory tests.

| Key Parameter | CFD Test Result | Laboratory Test Result | Conclusions |

|---|

| Temperature Increase (∆T) | 8.8 K | 8 K | High consistency of results, confirming the reliability of the model. |

Table 3.

Parametric sensitivity results—approximate change in integrated recovered energy () over 120 s.

Table 3.

Parametric sensitivity results—approximate change in integrated recovered energy () over 120 s.

| Parameter (Variation) | Typical Change in Recovered Energy (%) | Notes |

|---|

| HTCchamber (±20%) | ±12–14% | OAT perturbation: ±20% HTCchamber → ~±12–14%

|

| Rcontact (introduce ≈ 1 × 10−3 [m2·K/W]) | ≈10% | Small interfacial resistance reduces conduction between tube and channel |

| Geometry—effective contact area (−5%) | ≈5% | Reduced wetted contact area from misalignment → local bypassing |

| Geometry—effective contact area (−10%) | ≈8% | Larger assembly tolerance effects produce larger reductions |

Table 4.

Uncertainty study—Temperature measurements and the impact on .

Table 4.

Uncertainty study—Temperature measurements and the impact on .

| Parameter | Description/Formula | Value | Unit | Notes/Reference Equation |

|---|

| Sensor | PT100 kL. B | - | - | - |

| Manufacturer’s tolerance (±) | ±(0.30 + 0.005 t) | ±0.55 | °C | manufacturer spec. |

| Stability (±) | Sensor stability (user) | ±0.50 | °C | user assumption |

| DAQ/Logger | Rack2 NI9211 | <0.07 | °C | instrument spec (typical) |

| Sensor unit standard uncertainty | | 0.318; 0.289 | °C | converted from rectangular tolerances (10) |

| Combined sensor standard uncertainty usensor | | 0.429 | °C | independent components |

| u(T) (combined single-channel uncertainty) | | 0.435 | °C | including DAQ (9) |

| Uncertainty ∆T | u(∆T) | 0.615 | K | (9) |

| ∆T used in calculations [K] | | 8.0 | K | measured |

| calculated [W] | | 1394.78 | W | (6) |

| Relative component of ∆T | | 0.0786 | - | 7.7% |

| Total relative uncertainty | | 0.07944 | - | 7.9% [35] |

| u() [W] | | 110.74 | W | standard uncertainty (1σ) |

| U(95%)

| Expanded uncertainty, k = 2 | ±221.48 | W | 95% confidence |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).