Abstract

The heating and cooling sector accounts for nearly half of Europe’s energy consumption and remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, emphasizing the urgent need for decarbonization. Simultaneously, the global shift toward renewable energy is accelerating, alongside growing interest in decentralized energy systems where prosumers play a significant role. In this context, district heating and cooling networks, serving nearly 100 million people, are strategically important. In next-generation systems, thermal prosumers can feed-in locally produced or industrial waste heat into the network via bidirectional substations, allowing energy flows in both directions and enhancing system efficiency. The complexity of these networks, with numerous users and interacting heat flows, requires advanced predictive models to manage large volumes of data and multiple variables. This work presents the development of a predictive model based on artificial neural networks (ANNs) for forecasting excess thermal renewable energy from a bidirectional substation. The numerical model of a substation prototype designed by ENEA provided the physical data for the ANN training. Thirteen years of simulation results, combined with extensive meteorological data from ECMWF, were used to train and to test a multi-step ANN capable of forecasting the six-hour thermal power feed-in horizon using data from the preceding 24 h, improving operational planning and control strategies. The ANN model demonstrates high predictive capability and robustness in replicating thermal power dynamics. Accuracy remains high for horizons up to six hours, with MAE ranging from 279 W to 1196 W, RMSE from 662 W to 3096 W, and R2 from 0.992 to 0.823. Overall, the ANN satisfactorily reproduces the behavior of the bidirectional substation even over extended forecasting horizons.

1. Introduction

The EU’s climate neutrality target for 2050, along with the interim goal of a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030 [1], requires a profound transition of energy sectors towards efficiency, renewable energy sources (RES), and the decarbonization of thermal systems [2]. Heating and cooling, which account for nearly half of Europe’s final energy demand [3], remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels, while RES accounted for only 24.8% of heat production in 2022 [4]. The EU Energy Efficiency Directive 2023/1791, aligned with the European Green Deal, promotes efficient district heating (DH) systems and the integration of RES and waste heat (WH) into thermal networks [5]. In this context, district heating networks are recognized as a key solution for supporting the energy transition, particularly in urban areas [6,7]. Leveraging the synergies among these interconnected infrastructures allows for the optimization of the overall energy system, enabling more efficient management and contributing to the common goal of emission reduction [8].

Europe currently accounts for approximately 19,000 DHNs, supplying heat to over 77 million people, with the highest penetration in Northern European countries, followed by Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands [9]. Decentralization is gaining increasing importance, as both electrical systems and, more recently, DHNs aim to enhance flexibility and sustainability through prosumers capable of locally producing, consuming, and sharing energy, thereby facilitating the integration of RES.

In recent years, the scientific community has increasingly focused on the integration of thermal prosumers within DHNs, aiming to model both the networks and bidirectional users simultaneously and to evaluate how prosumers affect overall hydraulic, thermal, and energy performance.

Several studies have focused on a detailed analysis of thermal substations, which are the terminal points where heat power is exchanged between the network and users. Some authors have employed an experimental approach. Rosemann et al. [10] tested one of the first dynamic control strategies for prosumer substations in DHNs using Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulations; Lamaison et al. [11] tested a bidirectional substation prototype on an actual DHN under HIL conditions, analyzing its performance over twelve days; Pipiciello et al. [12] developed and tested a bidirectional substation prototype for DHNs with HIL simulations, which was later extended [13] to assess, over an annual cycle, the optimization and recovery of locally produced thermal energy; finally, Sdringola et al. [14] further refined the system, enhancing local energy self-consumption and management of surplus heat.

Other researchers have adopted a modeling and simulation approach to investigate substation behavior. Using the experimental data reported in [12], Sdringola et al. [15] built a dynamic model of a bidirectional substation in Modelica language. Dino et al. [16] employed TRNSYS to extend the simulation to two sites with different solar irradiation profiles. Gianaroli et al. designed the retrofit of an existing substation to enable bidirectional operation; this configuration was replicated in the laboratory [17] and subsequently modeled and simulated in Dymola [18]. Other researchers, who focus on the substation level, such as Zinsmeister et al. and Abugabbara et al., analyze various prosumer-side configurations in DHN, evaluating their performance through simulations with SimulationX® and Modelica, respectively [19,20].

Other studies have investigated the integration of prosumers into DHNs using primarily modeling and simulation approaches. Ancona et al. [21] assessed the impact of thermal prosumers on the network’s hydraulic and thermal parameters depending on their location, while Dattilo et al. [22] extended the analysis to the dynamic behavior of bidirectional networks, also considering the distribution of thermal energy through allocation algorithms used in energy communities [23]. Testasecca et al. [24] employed TRNSYS to model a low-temperature DHN combining traditional consumers and prosumers capable of injecting thermal energy into the network. Licklederer et al. [25] developed a steady-state thermo-hydraulic model for smart thermal networks, representing prosumer integration via a generic supply node. Finally, Gross et al. [26] proposed a thermo-hydraulic model to simulate bidirectional DHNs with prosumers, represented by supermarkets feeding the network with their full heat production from WH and solar thermal collectors.

Despite significant advances in the modeling and management of prosumers, the increasing complexity of DHNs, characterized by variable heat flows and numerous interacting users, highlights the need for advanced predictive approaches to ensure optimal energy management. In this context, several studies have focused on developing models for forecasting thermal demand. Simonović et al. [27] presented a short-term heat load forecasting model for small DH systems using ANN optimized via particle swarm optimization (PSO), while Kováč et al. [28] compared conventional ANN and wavelet-enhanced ANN models for short-term heat demand forecasting, demonstrating that wavelet preprocessing significantly improves prediction accuracy. Frison et al. [29] highlighted how the use of ANN, in particular Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and LSTM models, can significantly improve the forecasting of thermal demand in complex DHN, contributing to operational optimization and energy savings. While the aforementioned studies mainly focused on heat demand forecasting, Maryniak et al. [30] demonstrated the effectiveness of a two-hidden-layer ANN model for daily forecasting of heat production in DH plants.

Although ANN have been widely applied across various energy-related forecasting tasks, their use in the DH sector remains relatively limited. Moreover, most existing studies have focused on predicting heat demand rather than estimating excess heat production from thermal RES. This highlights a research gap that the present work aims to address.

This study focuses on the analysis of a bidirectional substation and investigates the ability of a multi-features and multi-step ANN model to predict thermal power feed into the DHN. The training data for the ANN were obtained from a numerical model of the bidirectional substation developed in Modelica language (using Dymola 2024x software), simulated over 13 years adopting 1 h resolution, with 10 years used for training and 3 years for testing. The LSTM neural network, consisting of a single layer with 32 neurons, predicts the following 6 h based on the previous 24 h. Results show a strong agreement between simulated and predicted values, except for very low power outputs typical of winter periods, which, however, do not compromise system operation. In the authors’ view the present work can help bring thermal network management closer to what is already established in smart electrical grids, where bidirectional flows are common, providing predictive tools useful to manage decentralized thermal prosumer production and optimize plant operation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bidirectional Substation Layout

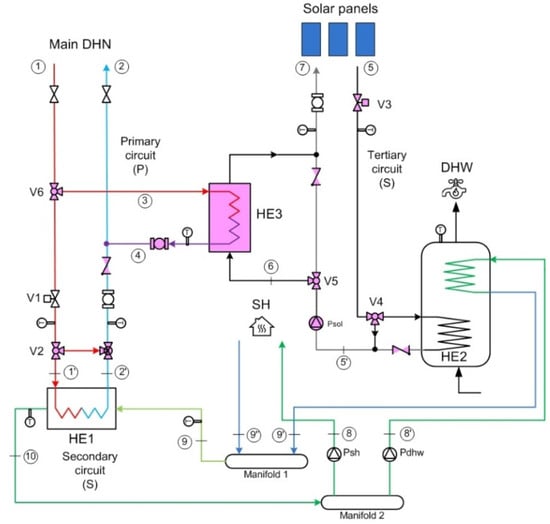

This study builds on the work of Gianaroli et al. [18], who designed a bidirectional substation for a third-generation existing DHN in northern Italy serving 34 residential units. The network’s supply temperature is maintained at 80 °C during the heating season and reduced to 70 °C in summer (ΔT = 20 °C) to meet domestic hot water (DHW) and space heating (SH) demands. Some of the connected buildings were already equipped with flat-plate solar thermal collectors, partially covering their DHW needs.

The retrofit aimed to integrate a thermal prosumer by converting the substation to a bidirectional configuration, leveraging the existing solar thermal system, which had previously been used solely for DHW self-consumption. This allows not only improved self-consumption but also the injection of surplus renewable energy into the network, providing additional thermal power.

Figure 1 shows the layout of the bidirectional substation in a supply-return configuration. This setup enabled a non-invasive retrofit while preserving the original control logic highlighting in the layout the new components in violet color. The HE1 heat exchanger, located at the interface between the user and the network, transfers thermal power from the primary to the secondary circuit, supplying DHW through the lower coil of the storage tank (HE2) and supporting SH. The solar system is connected to the upper coil of the tank to contribute to DHW production and to an additional heat exchanger (HE3) for feeding surplus thermal energy into the network’s return line. For more detailed information on the control strategies, the reader is invited to refer to [18].

Figure 1.

Bidirectional substation layout [18].

2.2. Numerical Model of Bidirecitonal Substation

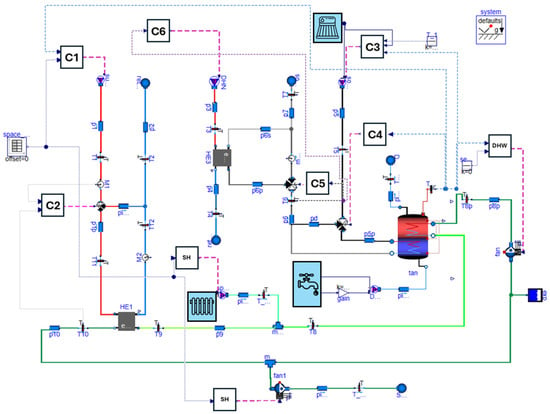

As part of the same study, the dynamic model of the substation was developed to operate throughout the entire year, as shown in Figure 2. The model was mainly built using components from the standard Modelica and IBPSA libraries, along with several custom-developed elements, such as a double-coil storage tank derived from IBPSA models.

Figure 2.

Bidirectional substation Dymola model [18].

The dynamic simulations, performed with a one-second time step, account for variations in DHW demand in terms of both temperature and mass flow rate, the regulation of SH through adjustments of the secondary circuit return temperature, and changes in solar generation profiles based on temperature fluctuations.

The data used for model validation were obtained from an experimental prototype [17], whose results were implemented in Modelica language (using Dymola 2024x software). Boundary conditions were dynamically defined using data tables as input signals.

In addition to the aforementioned data, the simulations require information on the demand of the new connected building, specifically the return temperature and mass flow of the SH system, as well as the mass flow and temperature of the DHW demand. These data were obtained from the results of Ricci et al. [31] for building #8. Furthermore, the solar thermal system was modeled specifically using the IBSA library. With respect to [18], in the present work the tabular inputs were replaced with numerical models of the building and the solar thermal system, enabling simulations over extended periods rather than single days. This approach provided a substantial dataset for training the ANN described in the following sections. Figure 2 shows the three components just described, highlighted as light blue rectangles (the color of the main branches refers to the same one used in the bidirectional substation layout).

Starting from the substation model described in the previous paragraphs, numerical simulations were carried out over a period of 13 years. The objective was to generate a sufficiently large dataset for the training of a dedicated ANN model. To collect the data, the ECMWF database was accessed through an ad hoc Python 3 script, which enabled the download of hourly data from the ERA5 [32] dataset for the same time interval reported in Table 1, corresponding to a location in Northern Italy. The environmental variables considered in this work (external air temperature and direct and diffuse solar irradiance) were selected as the primary drivers of solar thermal production and therefore exert the most direct influence on the excess heat fed into the DHN.

Table 1.

Model simulation set-up.

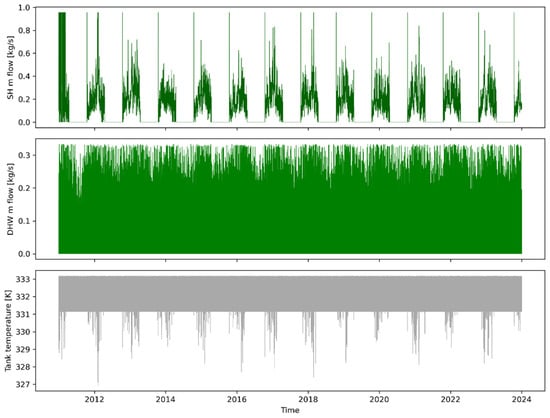

To illustrate the results obtained from the model simulations, two figures are presented showing the temporal evolution of the main variables characterizing the operation of the bidirectional substation. These results, covering the entire 13-year period, were also used as input for the ANN implementation. Specifically, Figure 3 displays three subplots showing, from top to bottom, the hot water flow rate required for SH, the hot water flow rate for DHW, and the temperature of the water in the storage tank. The SH flow rate clearly follows the typical seasonal pattern of the local climate, being active from October 15 to April 15 and zero for the rest of the year. The DHW flow rate maintains a stable daily profile throughout the simulation. Despite regular day-to-day variations, the overall demand pattern, characterized by morning and evening peaks, does not significantly change over the years. Finally, the tank temperature displays a typical set-point controlled pattern, remaining nearly constant at 62 °C (333.15 K) once the desired temperature is reached.

Figure 3.

Data trends over the entire simulated period: SH flow rate, DHW flow rate, tank temperature.

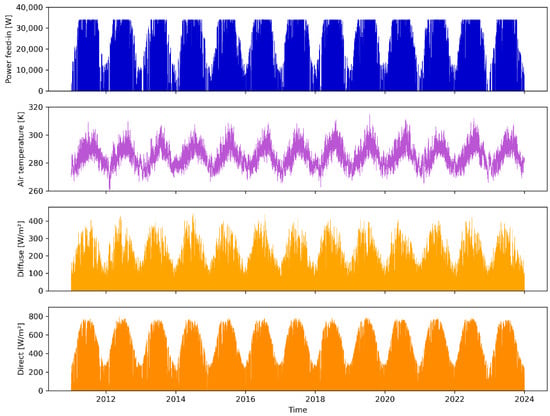

Figure 4, instead, presents four subplots showing, from top to bottom, the thermal power feed into the DHN by the substation, the outdoor air temperature, and the diffuse and direct solar radiation. All variables exhibit a typical seasonal behaviour, with peak values during the summer period, corresponding to higher ambient temperatures and increased solar irradiance, which in turn lead to greater thermal power feed into the network.

Figure 4.

Data trends over the entire simulated period: power feed-in, air temperature, diffuse radiation, direct radiation.

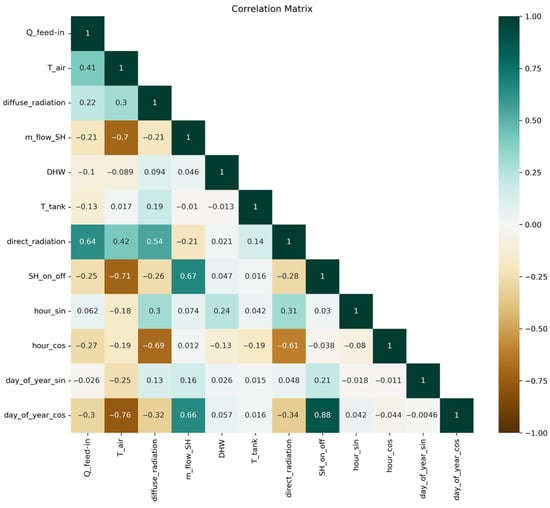

2.3. LSTM ANN Multi-Step Implementation

To effectively select input variables for training the ANN, the correlation coefficients among the measured quantities were calculated. The results of this analysis are summarized in the correlation matrix shown in Figure 5. The matrix clearly indicates that the target variable, i.e., the thermal power feed into the network (Q_feed-in), is strongly correlated with operational and environmental variables, particularly air temperature, global solar radiation, the mass flow in SH circuit, and the operational status of the SH system (on/off). These correlations were partly expected, given the physical nature of the process, which is strongly influenced by external conditions and solar irradiance. A significant correlation is also observed with cyclic temporal variables, such as hour of the day, day of the year, and month. Their seasonal and daily patterns can be effectively encoded using sine and cosine functions to preserve the cyclical continuity of the variable and improve the training of the ANN. Based on this consideration, only the aforementioned variables that show an absolute correlation coefficient higher than 0.25 have been selected as inputs for the ANN model to enhance its predictive capability and capture the complex dynamics affecting Q. In the cases when sine or cosine of a certain variable do not fulfil the cut-off value of 0.25, both are retained and used as inputs. This value has been chosen based also on previous simulations when it has been observed that adding variables did not lead to improved accuracy.

Figure 5.

Correlation Matrix.

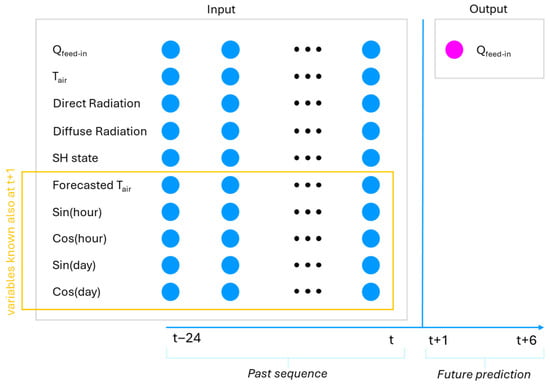

For the prediction of power feed into the DHN, the model inputs were selected by combining historical measurements with forecasted variables. This approach allows the model to leverage both past context and reliable predictive information for the forecast horizon. The historical variables include power feed-in, air temperature, diffuse and direct solar radiation, and the operational state of SH (on/off). In addition, cyclic encodings of the hour and day of the year are included, enabling the model to capture daily and seasonal periodic patterns. Input and output data window are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Forecasting model input data window and output.

To properly use input data for ANN, they were pre-processed to ensure consistency and temporal alignment across all signals. The power signal (Q_feed-in) was first slightly smoothed using a Savitzky–Golay filter to reduce noise and local fluctuations while preserving significant peaks, thereby promoting more stable and effective training of the ANN. Subsequently, all input variables were realigned and resampled to the same 1-h time step to ensure temporal consistency across all signals used for training. Continuous variables (e.g., T_air, diffuse_radiation, direct_radiation) were interpolated, while state variables (e.g., SH_on_off) were forward-filled. This procedure ensures that each input is perfectly synchronized with its corresponding target power value, maintaining temporal coherence and improving the LSTM model’s learning process. Additionally, some input variables have been scaled. In particular, the target variable Q_feed-in has been scaled using the RobustScaler utility provided by the Python package scikit-learn, which normalizes the data by subtracting the median and rescales the data based on the quantile range. All other continuous variables (external air temperature, diffuse and direct radiation) are instead scaled with the MinMaxScaler(a utility provided by the Python package scikit-learn) to bring them into the interval [0, 1].

Beyond historical variables, the model also incorporates forecasted information as variables that will be known at the time of prediction for the upcoming hours. In particular, in addition to measured air temperature from the ECMWF, the model uses the forecasts. Two forecasts are released daily and recorded in the ECMWF database, at 6:00 and 18:00, each covering the futures 12 h. These forecasted values are used as inputs not only as historical data but also as future variables, since they are known at the prediction time for the relevant horizon. The same approach is applied to other variables that can be determined in the future, such as the SH on/off state, whose seasonal pattern is fixed and known, and the cyclic time features (sine and cosine of hour and day).

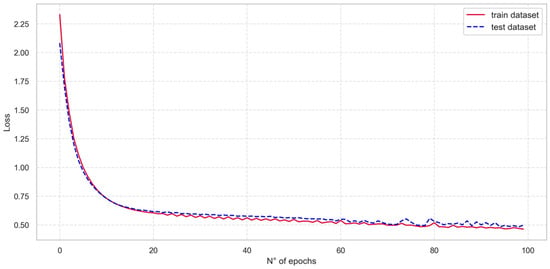

The implemented LSTM model is a multi-feature and multi-step model. Specifically, the model is trained for 10 years using hourly data to receive as input the selected historical and forecasted variables over the past 24 h and to predict the power feed-in for the following 6 h. The model is implemented in Python using the TensorFlow/Keras libraries. The chosen architecture consists of a single LSTM layer with 32 neurons and a hyperbolic tangent (tanh) activation function, followed by a dense output layer with a softplus activation function, suitable for regression of positive values. The loss function used for training is the Huber loss and optimization is performed using the Adam algorithm.

The model was trained for 100 epochs and Figure 7 illustrates the evolution of the loss metric throughout the training process. The results show that the loss function stabilizes, reaching a satisfactory level of stationarity on both the training and test datasets by the end of the 100 epochs, with no evidence of overfitting. Once training is complete, the model is used to generate predictions of the power feed-in, taking the test dataset as input.

Figure 7.

Training of the ANN: loss vs. epochs.

3. Results and Discussion

This section analyzes the performance of the predictive model during the testing phase, evaluating the ability of the ANN to forecast the thermal energy feed-in the DHN by the bidirectional substation. The results are compared with the data previously simulated in Dymola, in order to assess the accuracy of the predictions and their consistency with the physical behavior of the system.

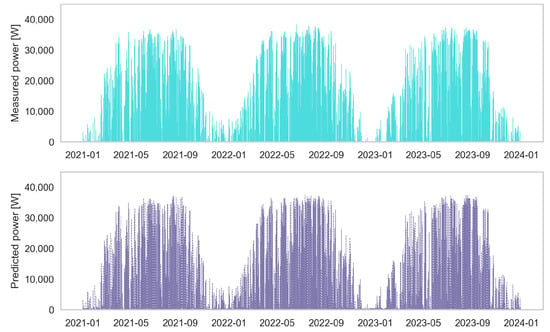

Figure 8 shows the trend of the thermal power feed-in the network by the substation, comparing the values (6 h prediction) obtained from the numerical model (upper plot) with those predicted by the ANN-based model (lower plot) over the period from January 2021 to January 2024. Although the selected time window does not allow a detailed inspection of the model’s accuracy, a good agreement can be observed between the two power profiles, providing preliminary qualitative evidence of the model’s effectiveness in reproducing the original data dynamics.

Figure 8.

Measured power vs. Predicted power.

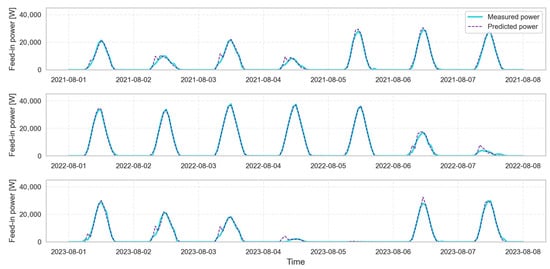

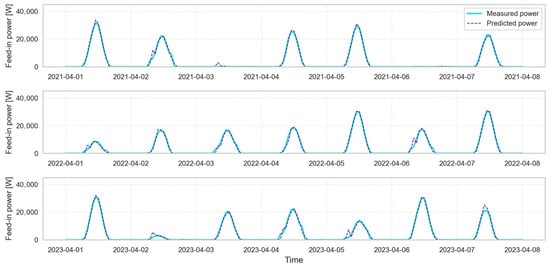

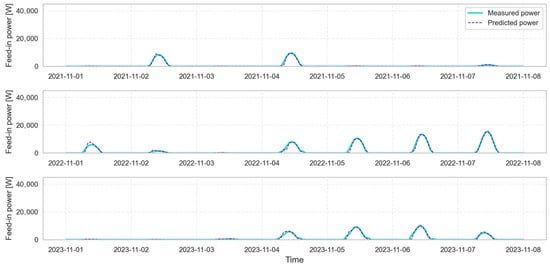

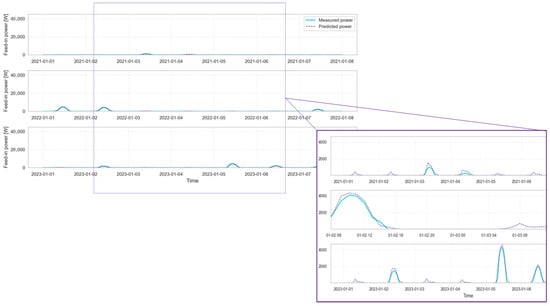

To provide a more detailed evaluation of the model’s predictive capability, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 present an in-depth analysis of the thermal power feed-in the network, showing the superimposed simulated and predicted values. The first set of plots, reported in Figure 9, focuses on a summer week between 1 and 8 August, analyzed over three consecutive years. This comparison is particularly useful as it highlights that the ANN does not merely “memorize” the data but is able to generalize effectively across different periods. An excellent level of accuracy can be observed, with the two curves almost completely overlapping. The same analysis was performed for a representative spring week (Figure 10) and autumn week (Figure 11), again confirming the strong consistency between the simulated and predicted data. For the winter period, an additional zoomed-in view is presented in Figure 12 to analyze the system dynamics in greater detail. During this season, as expected, solar production was lower due to reduced irradiation, resulting in a smaller (or even null) amount of thermal energy being fed into the network. This highlights that any discrepancies in the ANN model occur only for very low power values, without compromising the overall quality of the prediction. These low values correspond to periods of high intermittency, due to low levels of solar radiation, which are, however, effectively managed by the substation control and have minimal impact on the overall operation of the system.

Figure 9.

Measured power vs. predicted power: summer weeks.

Figure 10.

Measured power vs. predicted power: spring weeks.

Figure 11.

Measured power vs. predicted power: autumn weeks.

Figure 12.

Measured power vs. predicted power: winter weeks with zoom focus.

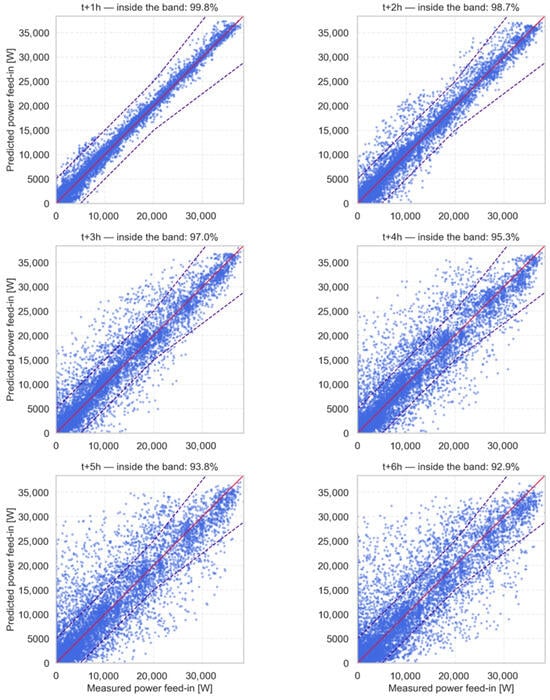

Figure 13 shows the comparison between the values obtained from the numerical model and those predicted by the ANN for the power fed into the network, considering individual forecast horizons from 1 to 6 h ahead. The plots are presented as scatter plots, where the bisector represents the ideal behavior in which the prediction perfectly matches the numerical data. The purple dashed lines indicate a tolerance band within which the prediction is considered acceptable. This band is calculated as the maximum between 25% of the value given by the numerical model and 5000 W (which is almost the 10% of the peak power). This approach prevents the model from being penalized for very low power values, where even a small absolute error (e.g., 500 W) could appear large in percentage terms. At the same time, the band increases proportionally for higher power values, maintaining a scale consistent with the physical behavior of the system. Looking at Figure 13, for each forecast horizon, the percentage of points falling within this tolerance band is reported. It can be observed that the model maintains a satisfactory accuracy even for longer horizons, decreasing from 99.8% in the first hour ahead to 92.9% in the sixth hour. Most points are distributed along the bisector, confirming the neural network’s ability to predict the thermal power with good precision, even in the presence of fluctuations and variations in the real data.

Figure 13.

Comparison between the measured and predicted feed-in power: scatter plot results in the 6 step-out hours.

Finally, to evaluate the predictive performance of the ANN model, several commonly used error metrics were calculated, including the mean absolute error (MAE), the root mean squared error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2), defined as follows:

where represents the measured thermal power from the substation simulation at time i, and represents the corresponding prediction generated by the ANN model.

The quantitative results of the ANN model predictions are summarized in Table 2. For a 1-h forecasting horizon, the model achieves a MAE of 279.6 W, an RMSE of 662 W, and an R2 value of 0.992, indicating a highly accurate estimation of thermal power. As the forecasting horizon increases, however, the model’s accuracy slightly decreases. This trend continues for longer horizons, reaching a MAE of 1196 W, an RMSE of 3096.5 W, and an R2 of 0.8233 at a 6-h horizon. These results show that while the prediction accuracy decreases with longer forecasting horizons, the R2 values remain relatively high up to 6 h, confirming the ANN model’s ability to capture the main thermal system dynamics even over extended time periods.

Table 2.

Error metrics for the ANN model.

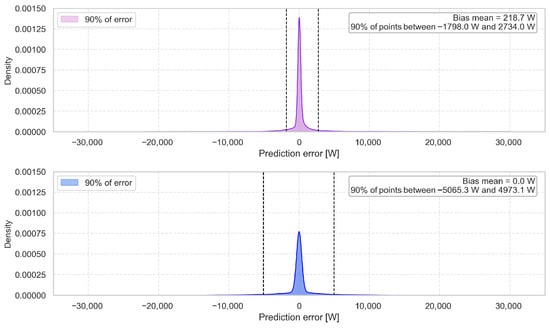

To evaluate the predictive performance of the ANN model, the results are compared with a simple persistence-based reference model. This model, used as a baseline, assumes that the variable of interest does not change significantly in the short term. In particular in this work, persistence is implemented by assuming that the thermal power at time t is equal to that observed at the same hour on the previous day. Comparing the ANN with this baseline model allows us to quantify the actual added value of a more sophisticated predictive approach. Figure 14 shows the density distributions of the residuals (errors), calculated as the difference between predicted (6 h prediction) and measured thermal power, for both the ANN model (top) and the persistence-based reference model (bottom). In the top plot, the distribution exhibits a sharp, symmetric peak around zero, indicating a strong ability of the model to reproduce the real behavior of the thermal system. The mean bias is +218.7 W, reflecting a slight overestimation, while 90% of the errors fall between –1798 W and +2734 W. In contrast, the bottom plot shows a broader and slightly flatter distribution, with a zero mean bias (0 W), but 90% of the errors range from −5065.3 W to +4973.1 W. The width of this interval, nearly twice that of the ANN model, highlights lower precision and greater variability in the predictions. Overall, Figure 14 demonstrates that the ANN provides a substantially more accurate estimate of thermal power, with residuals more tightly clustered around the true values and reduced mean error and dispersion compared to the persistence model.

Figure 14.

Distribution of prediction errors: LSTM model (top) vs. persistence baseline (bottom).

4. Conclusions

The topic of decentralization in energy systems is becoming increasingly relevant, not only in the electric sector, where this concept is well established, but also in the thermal sector. In this context, the shift toward decentralized configurations allows greater operational flexibility, promoting the integration of RES and the emergence of the thermal prosumer. DHN and thermal substations represent key elements of this transition, providing the infrastructure necessary for the bidirectional exchange of thermal energy between the network and users.

This study investigates the capabilities of a multi-feature and multi-step ANN model in predicting the thermal power feed into a DHN by a bidirectional substation that can exploit renewable energy from a solar thermal plant. To develop the ANN model, a numerical model of the bidirectional substation previously implemented in Modelica language (using Dymola software) was used [18]. Climate data for a location in Northern Italy were obtained from the ECMWF database via dedicated Python scripts, covering a 13-year period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2023 with an hourly time step. A simulation of the model was then performed to determine the thermal power feed into the network over the entire period. Based on the results, a correlation matrix was calculated to identify the most significant variables for model training, combining both historical data and variables known in the future. The ANN model, designed as a multi-step LSTM network, consists of a single layer with 32 neurons, aiming to predict the next 6 h based on the preceding 24 h. The implementation was developed in Python using TensorFlow libraries.

The results confirm the high predictive capability of the ANN model, which reproduces the temporal trend of thermal power feed into the network with excellent accuracy compared to the reference numerical model. Deviations occur only at very low power levels, typical of the winter season, and have minimal impact on the global results. Considering the adopted tolerance range, the model maintains high predictive accuracy, with 99.8% of predictions within acceptable limits for the one-hour horizon and 92.9% for the six-hour horizon. Error metrics further confirm the model’s robustness, with MAE ranging from 279 W for the one hour to 1196 W for the six hour and RMSE ranging from 662 W to 3096 W over the same horizons. The R2 coefficient remains high, from 0.992 for the one-hour forecast to 0.823 for the six-hour forecast, demonstrating the model’s ability to effectively capture the thermal dynamics of the system even over extended prediction horizons. Overall, the proposed ANN has proven capable of reproducing the physical behavior of the bidirectional substation with high fidelity.

The main contribution of this work is to show how predicting the thermal feed into the DHN can provide a useful tool to support, in the future, a more efficient management of decentralized thermal networks. With the rise in prosumers and distributed renewable sources, the ability to forecast energy flows becomes a key step toward exploring control strategies similar to those applied in the electricity market.

The bidirectional substation can play a crucial role in decarbonizing the system, as the controlled feed in of waste heat or excess renewable thermal energy reduces the load on the generation plant, which typically uses fossil-fuel boilers and cogenerators. This results in a lower environmental impact and potential economic benefits, primarily due to reduced fuel consumption. In this context, having a reliable predictive model helps the power plant regulate production, which cannot be modulated instantly or with extreme precision.

Future studies will focus on integrating the model into the network to evaluate its operational impact in terms of regulation and management of the plant evaluating the economic and environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.; methodology, M.R. and M.A.; software, M.R., M.A. and S.B.; validation, M.R. and F.G.; formal analysis, M.R. and F.G.; investigation, M.R., M.A. and F.G.; resources, S.B. and M.A.; data curation, F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, P.S., M.R. and M.A.; visualization, M.R. and F.G.; supervision, M.R., M.A. and P.S.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, M.R. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in the Program Agreement between the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA) and the Ministry of Environment and Energy Safety (MASE) for the Electric System Research, in the framework of its Implementation Plan for 2025–2027, Project 1.5 “High-efficiency buildings for the energy transition”, Work Package 3 “Innovative technologies and components for increasing the energy performance of buildings”. CUP: I53C24003330001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DH | District Heating |

| DHN | District Heating Network |

| DHW | Domestic Hot Water |

| HE | Heat Exchanger |

| HIL | Hardware In the Loop |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RES | Renewable Energy Source |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SH | Space Heating |

| WH | Waste Heat |

References

- European Climate Law—European Commission. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/european-climate-law_en (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Difs, K. National Energy Policies: Obstructing the Reduction of Global CO2 Emissions? An Analysis of Swedish Energy Policies for the District Heating Sector. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7775–7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billerbeck, A.; Breitschopf, B.; Preuß, S.; Winkler, J.; Ragwitz, M.; Keles, D. Perception of District Heating in Europe: A Deep Dive into Influencing Factors and the Role of Regulation. Energy Policy 2024, 184, 113860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Renewable_energy_statistics (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- EU. Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L 231/1, 1–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bürger, V.; Steinbach, J.; Kranzl, L.; Müller, A. Third Party Access to District Heating Systems—Challenges for the Practical Implementation. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Werner, S.; Möller, B.; Persson, U.; Boermans, T.; Trier, D.; Østergaard, P.A.; Nielsen, S. Heat Roadmap Europe: Combining District Heating with Heat Savings to Decarbonise the EU Energy System. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Chang, M.; Werner, S.; Svendsen, S.; Sorknæs, P.; Thorsen, J.E.; Hvelplund, F.; Mortensen, B.O.G.; Mathiesen, B.V.; et al. The Status of 4th Generation District Heating: Research and Results. Energy 2018, 164, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHC Market Outlook 2024—Euroheat & Power. Available online: https://www.euroheat.org/news/dhc-market-outlook-2024-the-most-comprehensive-publication-on-district-heating-and-cooling-to-date-1 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Rosemann, T.; Löser, J.; Rühling, K. A New DH Control Algorithm for a Combined Supply and Feed-In Substation and Testing Through Hardware-In-The-Loop. Energy Procedia 2017, 116, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaison, N.; Bavière, R.; Cheze, D.; Paulus, C. A Multi-Criteria Analysis of Bidirectional Solar District Heating Substation Architecture. In Proceedings of the SWC2017/SHC2017, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 29 October–2 November 2017; International Solar Energy Society: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pipiciello, M.; Caldera, M.; Cozzini, M.; Ancona, M.A.; Melino, F.; Di Pietra, B. Experimental Characterization of a Prototype of Bidirectional Substation for District Heating with Thermal Prosumers. Energy 2021, 223, 120036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipiciello, M.; Trentin, F.; Soppelsa, A.; Menegon, D.; Fedrizzi, R.; Ricci, M.; Di Pietra, B.; Sdringola, P. The Bidirectional Substation for District Heating Users: Experimental Performance Assessment with Operational Profiles of Prosumer Loads and Distributed Generation. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdringola, P.; Pipiciello, M.; Ricci, M.; Gianaroli, F.; Menegon, D.; Trentin, F.; Turrin, F.; Di Pietra, B. Prosumers and District Heating: Experimental Validation of Strategies to Improve Thermal Energy Production and Consumption. Energy Build. 2025, 338, 115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdringola, P.; Ricci, M.; Ancona, M.A.; Gianaroli, F.; Capodaglio, C.; Melino, F. Modelling a Prototype of Bidirectional Substation for District Heating with Thermal Prosumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dino, G.E.; Catrini, P.; Buscemi, A.; Piacentino, A.; Palomba, V.; Frazzica, A. Modeling of a Bidirectional Substation in a District Heating Network: Validation, Dynamic Analysis, and Application to a Solar Prosumer. Energy 2023, 284, 128621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianaroli, F.; Pipiciello, M.; Sdringola, P.; Trentin, F.; Ricci, M.; Di Pietra, B.; Melino, F. Empowering Prosumers in District Heating Networks: Experimental Analysis and Performance Evaluation of a Bidirectional Substation. In Proceedings of the ECOS2024, Rhodes, Greece, 1 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gianaroli, F.; Ricci, M.; Sdringola, P.; Pipiciello, M.; Menegon, D.; Melino, F. Innovative Approach and Numerical Modeling to Retrofit Existing Substations for Bidirectional Operation: Enabling Thermal Prosumer Participation in District Heating Network. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsmeister, D.; Licklederer, T.; Christange, F.; Tzscheutschler, P.; Perić, V.S. A Comparison of Prosumer System Configurations in District Heating Networks. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugabbara, M.; Lindhe, J.; Javed, S.; Bagge, H.; Johansson, D. Modelica-Based Simulations of Decentralised Substations to Support Decarbonisation of District Heating and Cooling. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, M.A.; Bianchi, M.; Branchini, L.; De Pascale, A.; Melino, F.; Peretto, A.; Rosati, J. Influence of the Prosumer Allocation and Heat Production on a District Heating Network. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021, 7, 623932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, A.; Melino, F.; Ricci, M.; Sdringola, P. Optimizing Thermal Energy Sharing in Smart District Heating Networks. Energies 2024, 17, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianaroli, F.; Ricci, M.; Sdringola, P.; Alessandra Ancona, M.; Branchini, L.; Melino, F. Development of Dynamic Sharing Keys: Algorithms Supporting Management of Renewable Energy Community and Collective Self Consumption. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testasecca, T.; Catrini, P.; Beccali, M.; Piacentino, A. Dynamic Simulation of a 4th Generation District Heating Network with the Presence of Prosumers. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 20, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licklederer, T.; Zinsmeister, D.; Lukas, L.; Speer, F.; Hamacher, T.; Perić, V.S. Control of Bidirectional Prosumer Substations in Smart Thermal Grids: A Weighted Proportional-Integral Control Approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 354, 122239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Karbasi, B.; Reiners, T.; Altieri, L.; Wagner, H.-J.; Bertsch, V. Implementing Prosumers into Heating Networks. Energy 2021, 230, 120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonović, M.B.; Nikolić, V.D.; Petrović, E.P.; Ćirić, I.T. Heat Load Prediction of Small District Heating System Using Artificial Neural Networks. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, S1355–S1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováč, S.; Micháčonok, G.; Halenár, I.; Važan, P. Comparison of Heat Demand Prediction Using Wavelet Analysis and Neural Network for a District Heating Network. Energies 2021, 14, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frison, L.; Kollmar, M.; Oliva, A.; Bürger, A.; Diehl, M. Model Predictive Control of Bidirectional Heat Transfer in Prosumer-Based Solar District Heating Networks. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryniak, A.; Banaś, M.; Michalak, P.; Szymiczek, J. Forecasting of Daily Heat Production in a District Heating Plant Using a Neural Network. Energies 2024, 17, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Sdringola, P.; Tamburrino, S.; Puglisi, G.; Donato, E.D.; Ancona, M.A.; Melino, F. Efficient District Heating in a Decarbonisation Perspective: A Case Study in Italy. Energies 2022, 15, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 19 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).