Experimental and Modelling Study on the Performance of an SI Methanol Marine Engine Under Lean Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

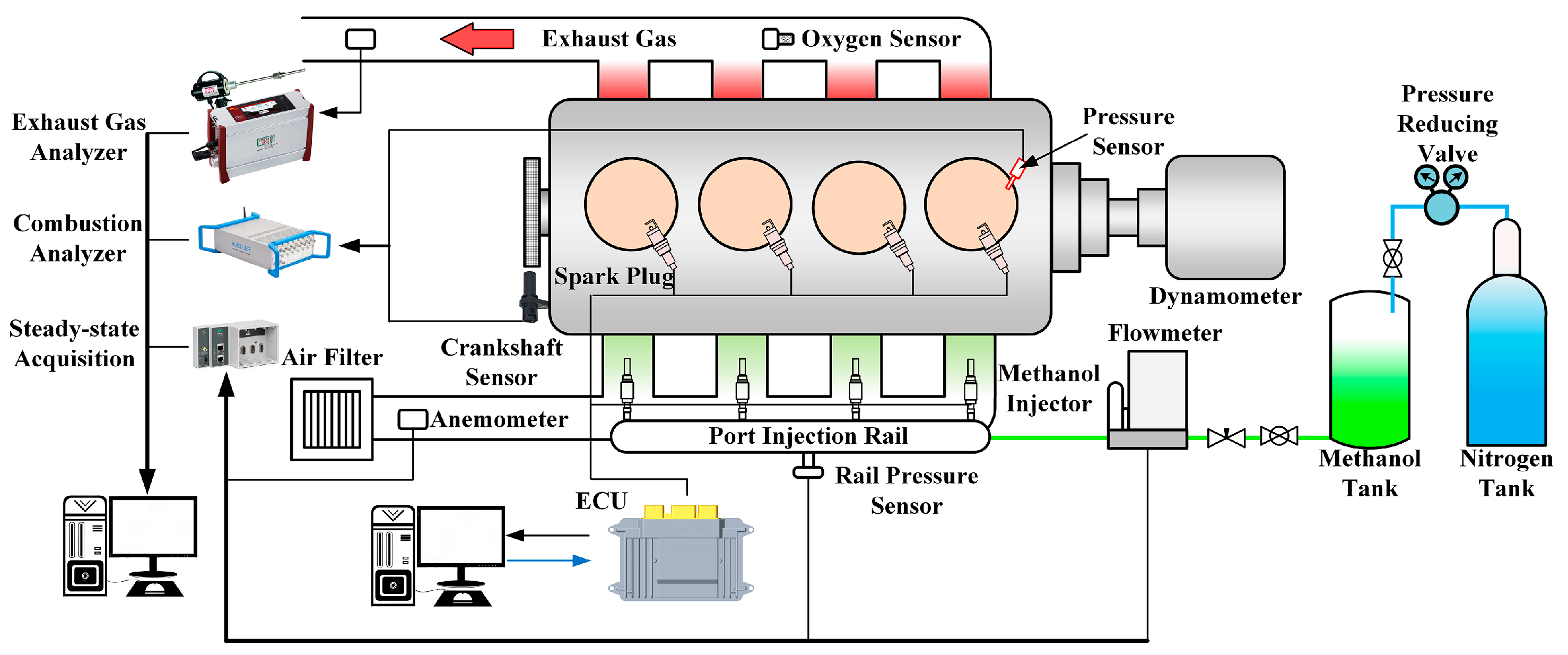

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Data Processing

2.3. Machine Learning Models of the Methanol Engine

3. Results and Discussion

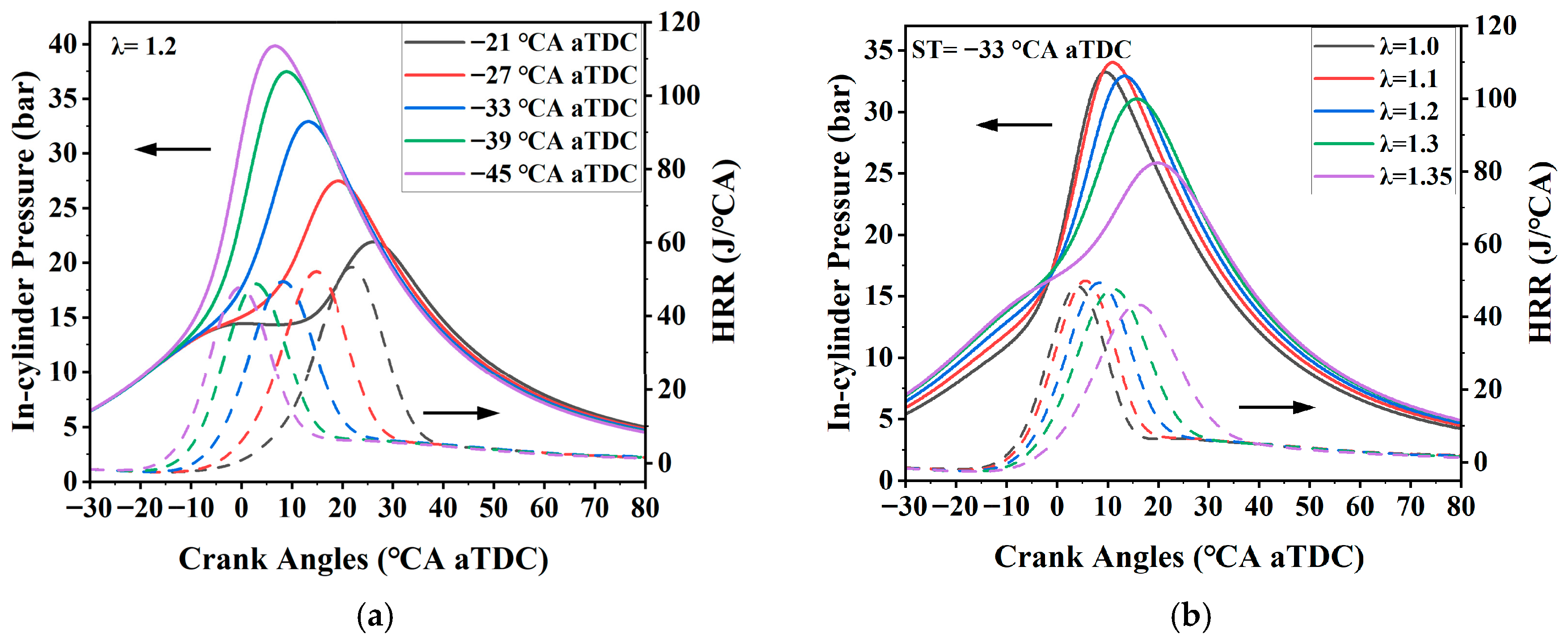

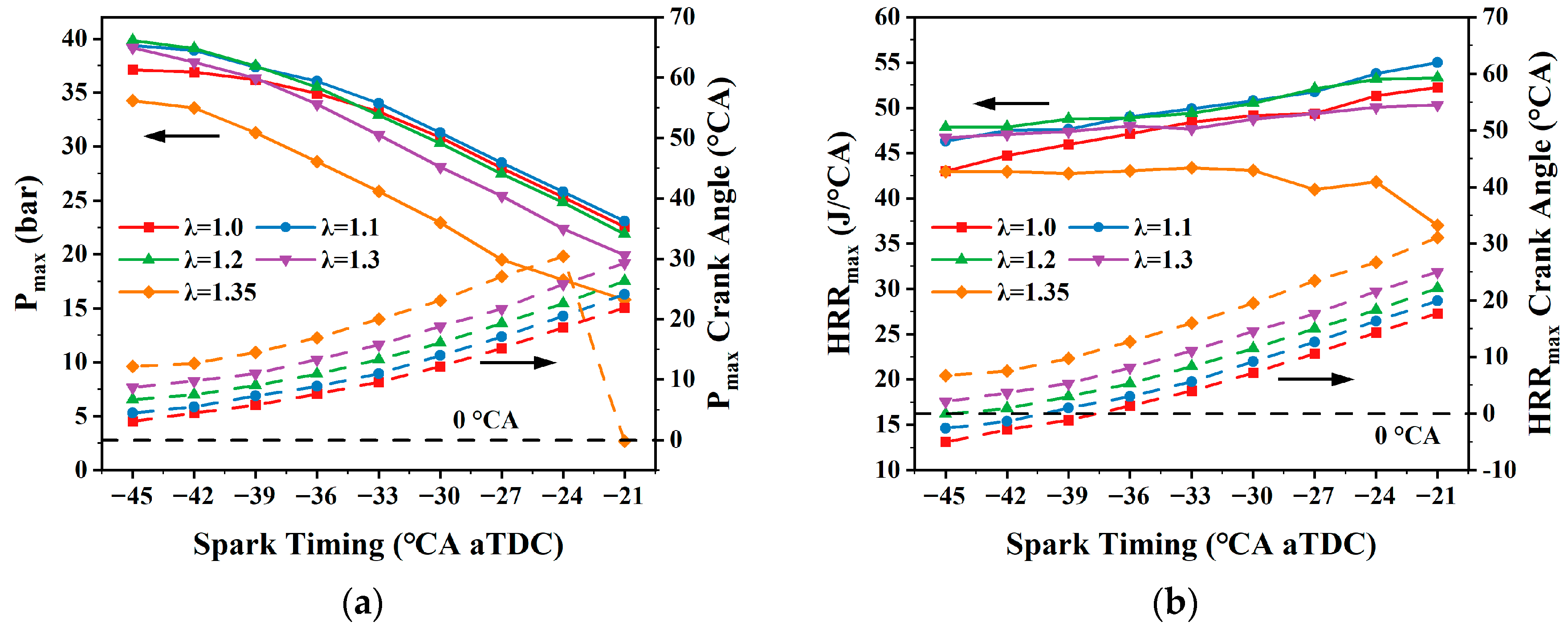

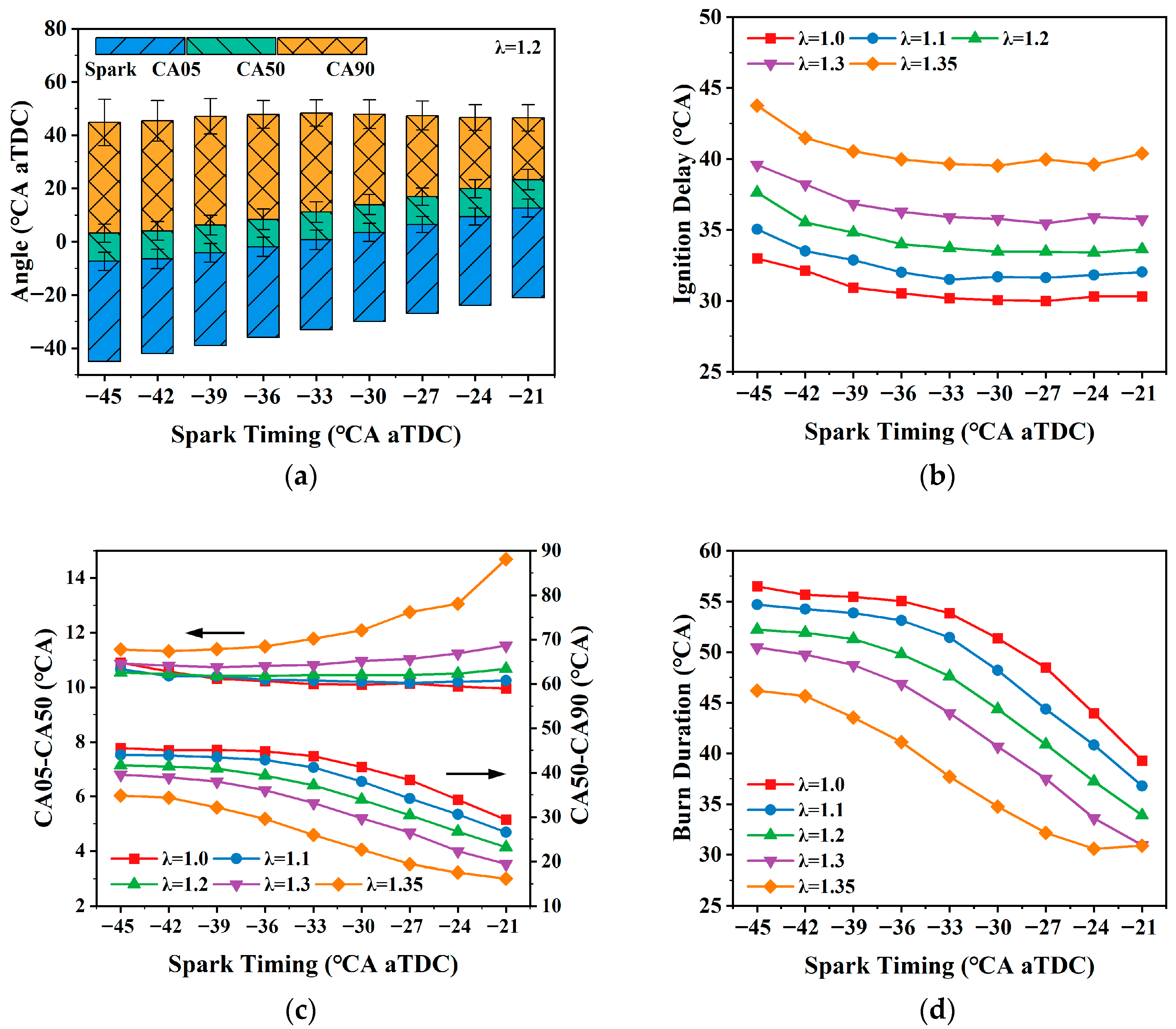

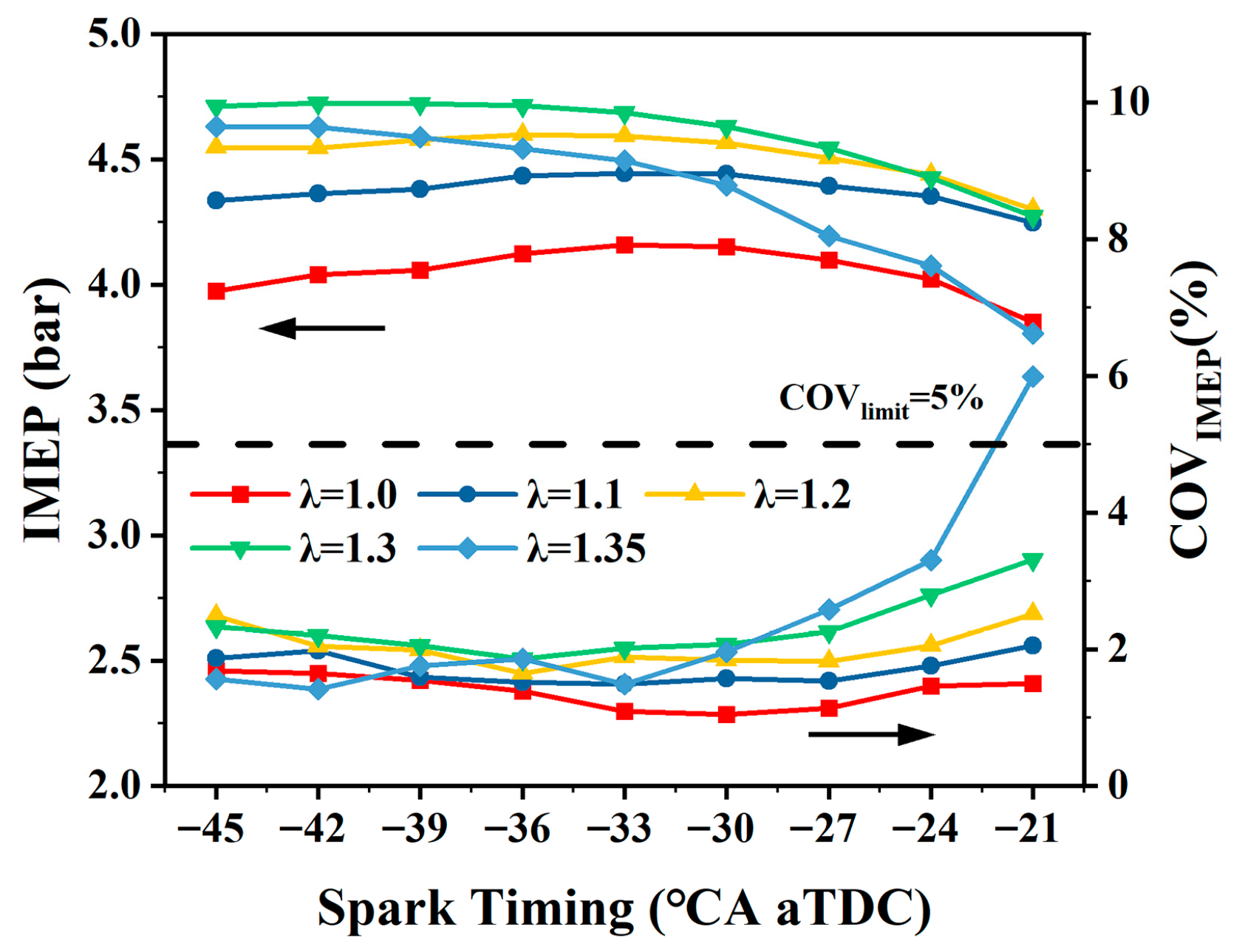

3.1. Combustion Characteristics

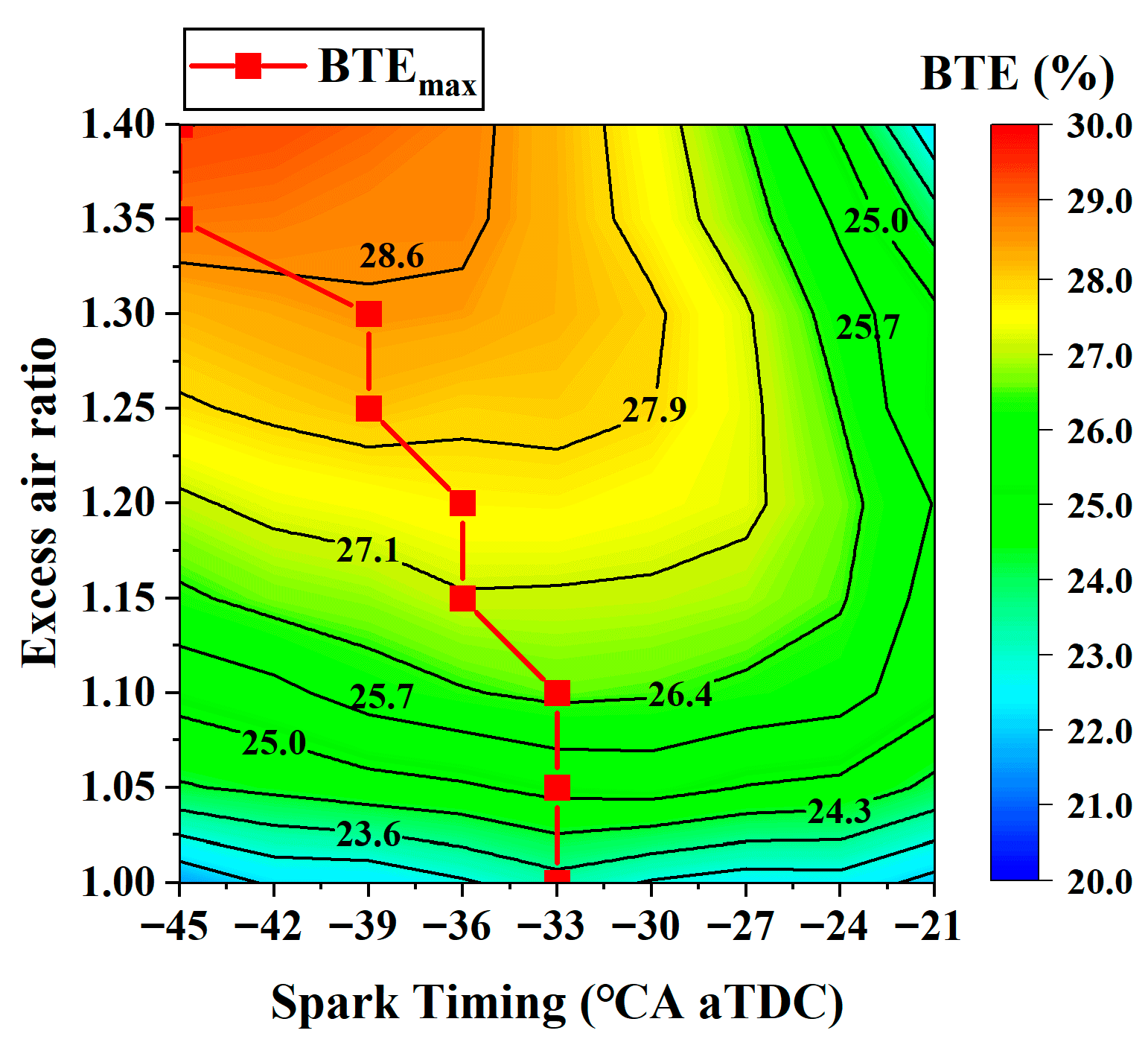

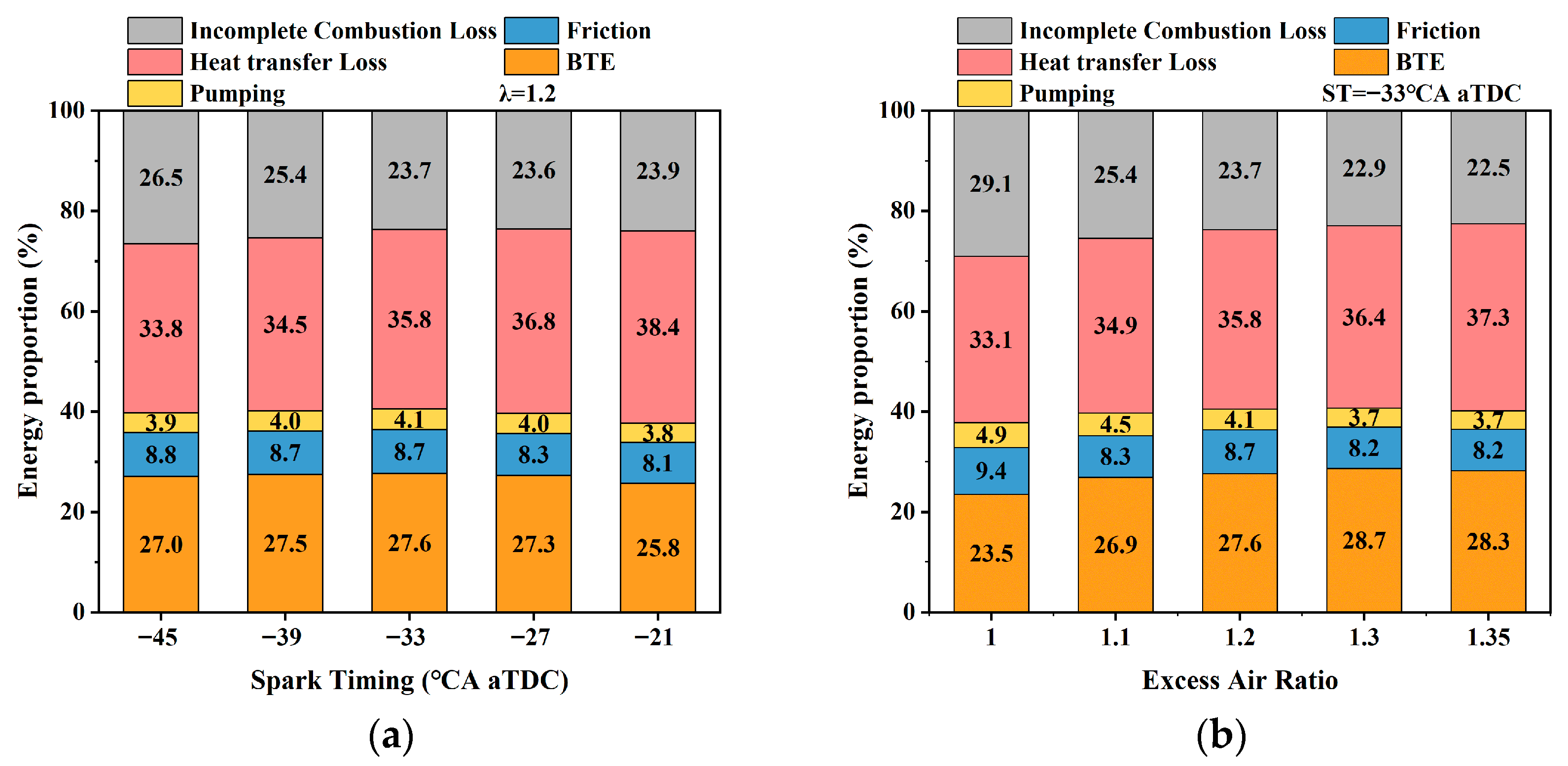

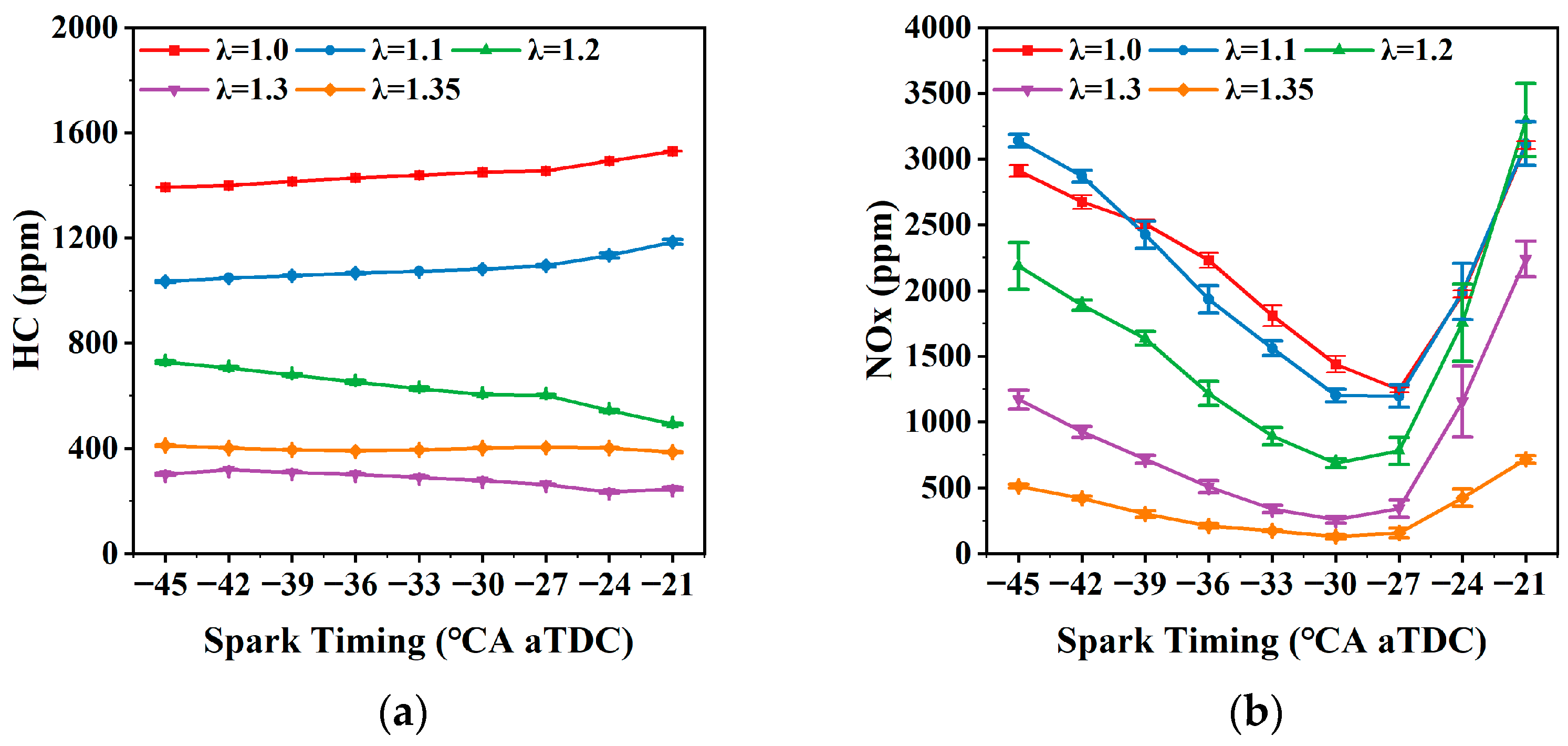

3.2. Engine Performance and Emission Characteristics

3.3. Machine Learning Modelling for Methanol Engine Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bortnowska, M. Projected reductions in CO2 emissions by using alternative methanol fuel to power a service operation vessel. Energies 2023, 16, 7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, O.; Daly, C. Litigating the fit for 55 package: Statutory and rights-based challenges to national energy and climate plans as a means of implementing and/or enhancing the ambition of the EU’s fit for 55 package. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2025, 34, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakko-Saksa, P.T.; Lehtoranta, K.; Kuittinen, N.; Järvinen, A.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johnson, K.; Jung, H.; Ntziachristos, L.; Gagné, S.; Takahashi, C.; et al. Reduction in greenhouse gas and other emissions from ship engines: Current trends and future options. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 94, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.; McDonagh, S.; O’Shea, R.; Smyth, B.; Murphy, J.D. Decarbonising ships, planes and trucks: An analysis of suitable low-carbon fuels for the maritime, aviation and haulage sectors. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Study of knock in a high compression ratio SI methanol engine using LES with detailed chemical kinetics. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 75, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Mu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Du, R.; Guan, W.; Liu, S. Cylinder-to-cylinder variation of knock and effects of mixture formation on knock tendency for a heavy-duty spark ignition methanol engine. Energy 2022, 254, 124197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hong, W.; Xie, F.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Fang, K.; Zhu, X. Effects of diluents on cycle-by-cycle variations in a spark ignition engine fueled with methanol. Energy 2019, 182, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Yuan, C.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sheng, C. Methanol as an alternative fuel for marine engines: A comprehensive review of current state, opportunities, and challenges. Renew. Energy 2025, 252, 123562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Mu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Du, R.; Liu, S. Experimental evaluation of performance of heavy-duty SI pure methanol engine with EGR. Fuel 2022, 325, 124948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zeng, K. Comparative study of combustion process and cycle-by-cycle variations of spark-ignition engine fueled with pure methanol, ethanol, and n-butanol at various air–fuel ratios. Fuel 2019, 254, 115683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Jeong, H.J.; Massoudi Farid, M.; Hwang, J. Effect of staged combustion on low NOx emission from an industrial-scale fuel oil combustor in south korea. Fuel 2017, 210, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Iida, N. An investigation of multiple spark discharge using multi-coil ignition system for improving thermal efficiency of lean SI engine operation. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qu, H.; Han, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Xie, F.; Qian, D. Effect of the miller cycle strategy on methanol and ethanol engines under stoichiometric combustion and lean burn. Energy 2025, 327, 136416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Park, C.; Oh, S.; Cho, G. The effects of stratified lean combustion and exhaust gas recirculation on combustion and emission characteristics of an LPG direct injection engine. Energy 2016, 115, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, F. Numerical evaluation of ignition timing influences on performance of a stratified-charge H2/methanol dual-injection automobile engine under lean-burn condition. Energy 2024, 290, 130209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Kou, H.; Li, T.; Yin, X.; Zeng, K.; Wang, L. Effects of injection and spark timings on combustion, performance and emissions (regulated and unregulated) characteristics in a direct injection methanol engine. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 247, 107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Duan, Q.; Kou, H.; Zeng, K. Parametric study on effects of methanol injection timing and methanol substitution percentage on combustion and emissions of methanol/diesel dual-fuel direct injection engine at full load. Fuel 2020, 279, 118424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Yue, G.; Liu, J.; Duan, H.; Duan, Q.; Kou, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Zeng, K. Investigation into the operating range of a dual-direct injection engine fueled with methanol and diesel. Energy 2023, 267, 126625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri-Garavand, A.; Heidari-Maleni, A.; Mesri-Gundoshmian, T.; Samuel, O.D. Application of artificial neural networks for the prediction of performance and exhaust emissions in IC engine using biodiesel-diesel blends containing quantum dot based on carbon doped. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 16, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ji, C.; Shi, C.; Ge, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, J. Development of cyclic variation prediction model of the gasoline and n-butanol rotary engines with hydrogen enrichment. Fuel 2021, 299, 120891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Molkdaragh, R.; Jafarmadar, S.; Khalilaria, S.; Soukht Saraee, H. Prediction of the performance and exhaust emissions of a compression ignition engine using a wavelet neural network with a stochastic gradient algorithm. Energy 2018, 142, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, G.; Li, B.; Tian, H.; Leng, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, D.; Long, W. Study on the performance of diesel-methanol diffusion combustion with dual-direct injection system on a high-speed light-duty engine. Fuel 2022, 317, 123414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Deng, J.; Wang, C.; Deng, R.; Yang, H.; Tang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, L. Operating and thermal efficiency boundary expansion of argon power cycle hydrogen engine. Processes 2023, 11, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.; Kosaka, H.; Bady, M.; Sato, S.; Abdel-Rahman, A.K. Combustion and emission characteristics of DI diesel engine fuelled by ethanol injected into the exhaust manifold. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 164, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, G. Quantitative investigation the influences of the injection timing under single and double injection strategies on performance, combustion and emissions characteristics of a GDI SI engine fueled with gasoline/ethanol blend. Fuel 2020, 260, 116363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyfuss, B.; Flicker, L.; Gotthard, T.; Hofmann, P.; Zahradnik, F.; Krenn, C.; Lubich, G. Evaluation of Spark-Ignited Kerosene Operation in a Wankel Rotary Engine; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Ji, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Ge, Y. Comparative evaluation of intelligent regression algorithms for performance and emissions prediction of a hydrogen-enriched wankel engine. Fuel 2021, 290, 120005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Shen, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Z. Research on the prediction and influencing factors of heavy duty truck fuel consumption based on LightGBM. Energy 2024, 296, 131221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar De Lima Nogueira, S.; Och, S.H.; Moura, L.M.; Domingues, E.; Coelho, L.D.S.; Mariani, V.C. Prediction of the NOx and CO2 emissions from an experimental dual fuel engine using optimized random forest combined with feature engineering. Energy 2023, 280, 128066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Geng, L. Experimental study of the effects of spark timing and water injection on combustion and emissions of a heavy-duty natural gas engine. Fuel 2020, 276, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ma, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, F.; Hu, Q.; Duan, H.; Zeng, K. Optimizing air-fuel ratio for balancing thermal efficiency and emissions in a methanol direct injection engine under diverse operating conditions. Energy 2025, 334, 137547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B. Effect of spark timing on the performance of a hybrid hydrogen–gasoline engine at lean conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Xu, L.; Duan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, K.; Wang, Y. In-depth comparison of methanol port and direct injection strategies in a methanol/diesel dual fuel engine. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 241, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wan, J.; Qian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Experimental investigation of water injection and spark timing effects on combustion and emissions of a hybrid hydrogen-gasoline engine. Fuel 2022, 322, 124051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Pan, G.; Han, D.; Huang, Z. Combustion and emissions of an ammonia-gasoline dual-fuel spark ignition engine: Effects of ammonia substitution rate and spark ignition timing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhak, M.İ.; Tangöz, S.; Akansu, S.O.; Kahraman, N. An experimental investigation of the use of gasoline-acetylene mixtures at different excess air ratios in an SI engine. Energy 2019, 175, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, F. Combined impact of excess air ratio and injection strategy on performances of a spark-ignition port- plus direct-injection dual-injection gasoline engine at half load. Fuel 2023, 340, 127605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Specification |

|---|---|

| Number of cylinders | Inline 4-cylinder |

| Displacement (L) | 4.214 |

| Bore (mm) | 108 |

| Stroke (mm) | 115 |

| Compression ratio | 12.5:1 |

| Number of valves | 2 |

| IVO/IVC (°CA aTDC) | 327/606 |

| EVO/EVC (°CA aTDC) | 114/378 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Engine speed (rpm) | 1400 |

| Excess air ratio | 1.0~1.4 |

| Spark timing (°CA aTDC) | −21~−45 |

| Coolant temperature (K) | 348 ± 5 |

| End of injection (°CA aTDC) | −240 |

| Intake pressure (bar) | 1.0 |

| Injection pressure (MPa) | 0.9 |

| Injection pulse width (ms) | 1400 |

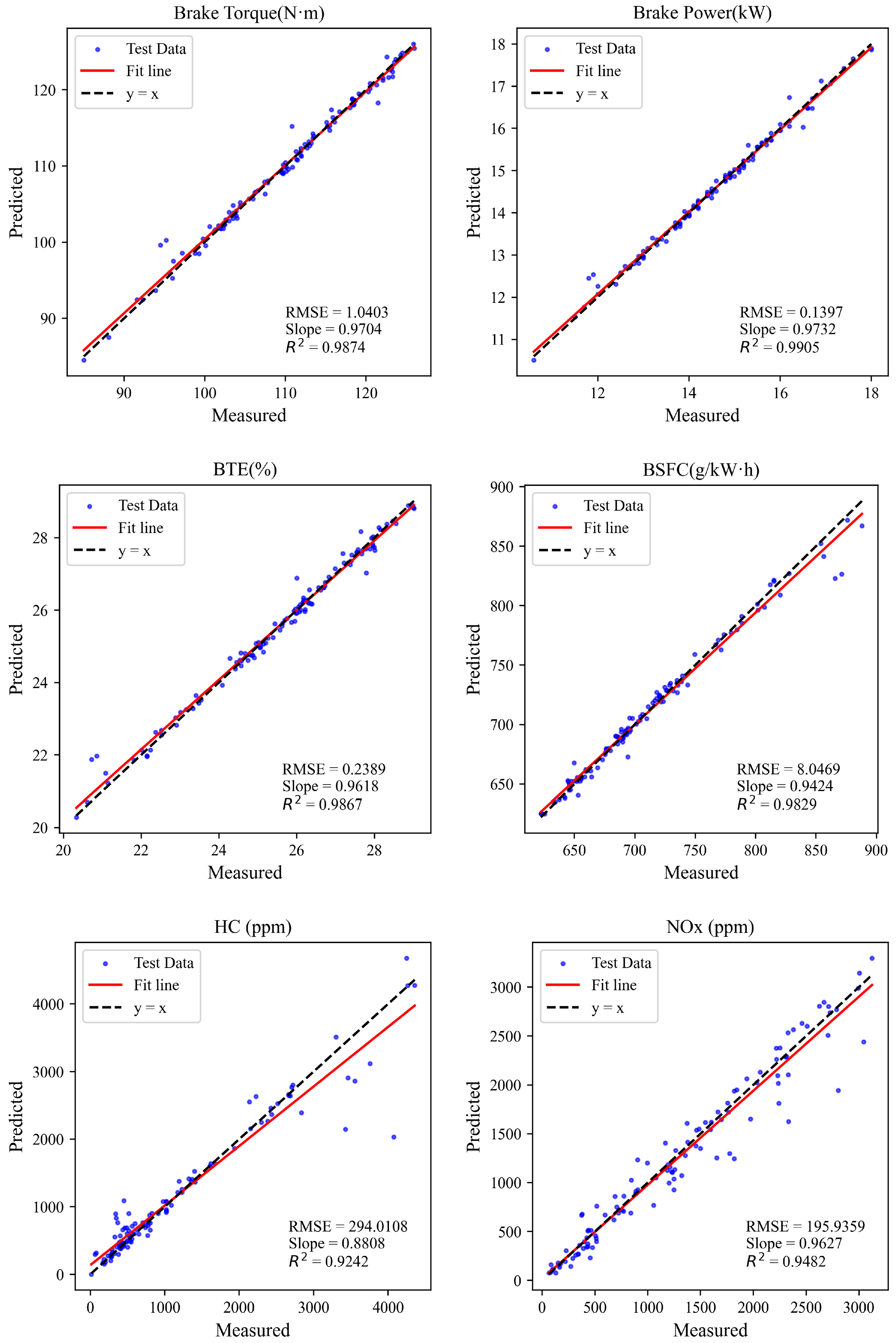

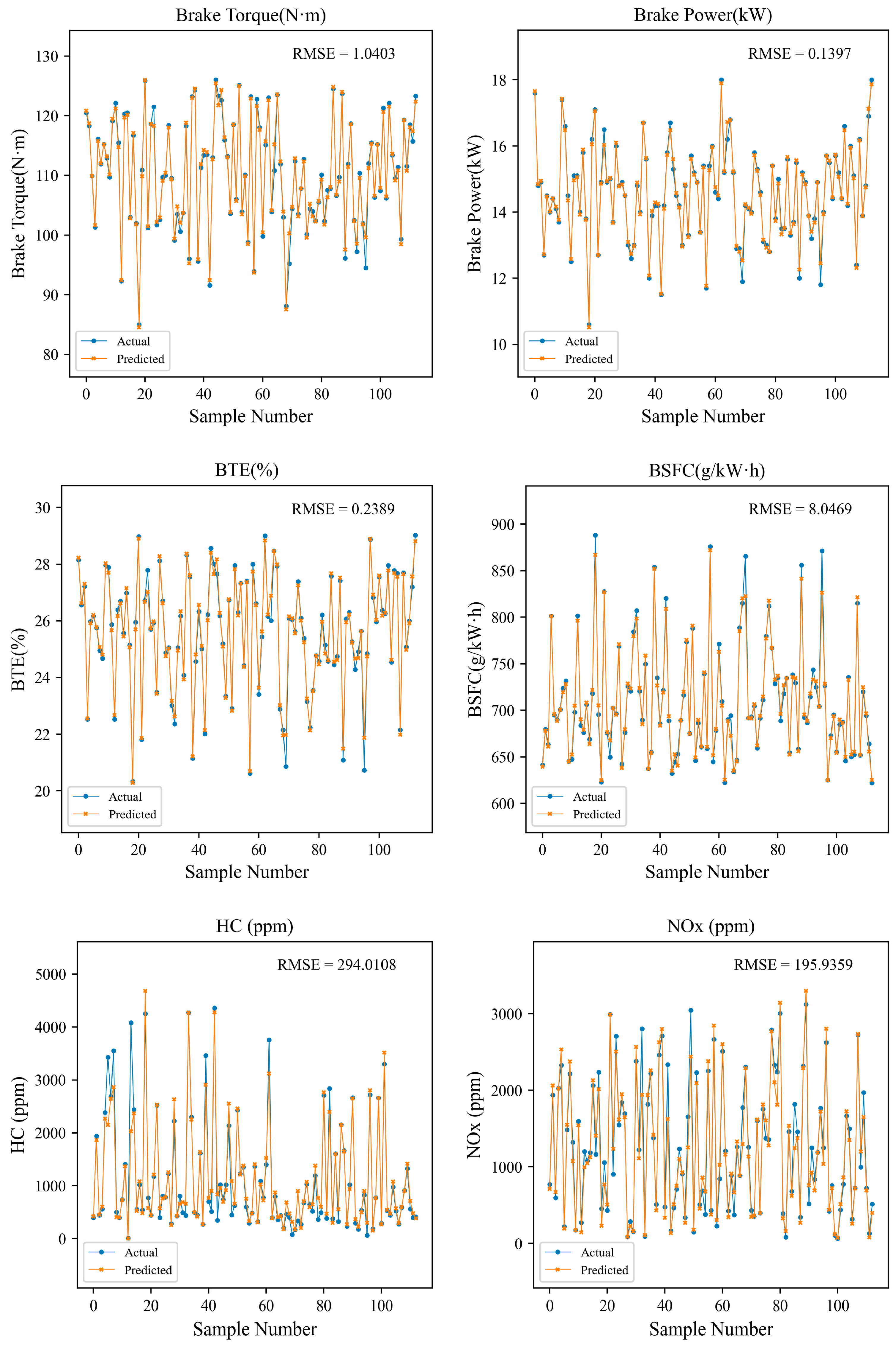

| R2 | RMSE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | ANN | LightGBM | RF | SVM | ANN | LightGBM | RF | |

| Brake Torque (N·m) | 0.9874 | 0.9496 | 0.9760 | 0.9245 | 1.0403 | 2.0818 | 1.4367 | 2.5469 |

| Brake Power (kW) | 0.9905 | 0.9802 | 0.9764 | 0.9516 | 0.1397 | 0.2016 | 0.2197 | 0.3147 |

| BTE (%) | 0.9867 | 0.9670 | 0.9806 | 0.9476 | 0.2389 | 0.3764 | 0.2886 | 0.4739 |

| BSFC (g/kW·h) | 0.9829 | 0.9573 | 0.9797 | 0.9379 | 8.0469 | 12.7104 | 8.7745 | 15.3364 |

| HC (ppm) | 0.9242 | 0.8541 | 0.9894 | 0.9486 | 294.0108 | 407.7730 | 110.1627 | 241.9497 |

| NOx (ppm) | 0.9482 | 0.8951 | 0.8687 | 0.8399 | 195.9359 | 278.8169 | 311.9660 | 344.5104 |

| Train MSE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold 1 | Fold 2 | Fold 3 | |

| Brake Torque (N·m) | 0.0586 | 0.0524 | 0.0459 |

| Brake Power (kW) | 0.0355 | 0.0331 | 0.0272 |

| BTE (%) | 0.0639 | 0.0565 | 0.0465 |

| BSFC (g/kW·h) | 0.0765 | 0.0675 | 0.0614 |

| HC (ppm) | 0.3216 | 0.2687 | 0.2213 |

| NOx (ppm) | 0.2541 | 0.2147 | 0.2094 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, S.; Liu, W.; Luo, J.; Fang, Z.; Gao, X. Experimental and Modelling Study on the Performance of an SI Methanol Marine Engine Under Lean Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246607

Gong S, Liu W, Luo J, Fang Z, Gao X. Experimental and Modelling Study on the Performance of an SI Methanol Marine Engine Under Lean Conditions. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246607

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Shishuo, Weijie Liu, Junbo Luo, Zhou Fang, and Xiang Gao. 2025. "Experimental and Modelling Study on the Performance of an SI Methanol Marine Engine Under Lean Conditions" Energies 18, no. 24: 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246607

APA StyleGong, S., Liu, W., Luo, J., Fang, Z., & Gao, X. (2025). Experimental and Modelling Study on the Performance of an SI Methanol Marine Engine Under Lean Conditions. Energies, 18(24), 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246607