Abstract

Microalgae have been characterized as an effective raw material for obtaining bioproducts from a biorefinery approach. However, production costs limit the large-scale production of microalgae, which makes these processes uncompetitive in the market. Therefore, in the present work, different agricultural fertilizers were evaluated as low-cost culture media for microalgae growth and the use of the biomass for biocrude production. The tests were carried out in three phases: phase I, Laboratory scale 1 L Erlenmeyer (Boeco, Hamburg, Germany) and phase II–III Pilot scale with cylindrical photobioreactors (PBRs) (Atb services S.A.S, Medellin, Colombia) with a capacity of 20 L. In phase I, four commercial fertilizers Crecilizer® (C), Florilizer® (F) (Fertilizer, Bogota, Colombia), AcuaLeaf Macros® (Ma), and AcuaLeaf Micros® (Mi) (Deacua, Medellin, Colombia) were tested separately and in combination (C + Ma, F + M, and Ma + Mi). The most effective treatments (C and F) in phase I were chosen for scale-up during phase II. In phase III, the concentration of the best treatment from phase II was increased. The biomass obtained from the best phase III treatment showed a cultivation medium cost 50% lower than the biomass obtained using Bold’s Basal Medium (BBM). Following each treatment, the harvested biomass was processed via hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) to yield biocrude. The reduction in culture medium cost contributed to an estimated 40% decrease in the relative biocrude yield cost.

1. Introduction

The production of microalgae has gained relevance in different industries due to the opportunities they offer, most of which are related to human health, sustainable development, and bioremediation [1,2,3,4,5]. The most notable applications include the production of pigments, the capture of greenhouse gases, the production of biocrude, and water treatment, among others. However, the profitability and sustainability of these applications depend on the aforementioned production cost associated with the processes, which has hindered their large-scale application; for example, the production cost of microalgal fuel is at least twice as high as that of fossil fuels [1,3]. Situations like the aforementioned have meant that microalgae have been relegated to high-value applications or very specific markets related to pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food [6].

Typically, the production costs of microalgal biomass are primarily attributed to the expenses incurred in the culture medium and energy consumption [7]. Of particular significance are the costs associated with nutrient requirements, given that these microorganisms require approximately 200 tons of CO2, 10 tons of nitrogen, and 1 ton of phosphorus to produce 100 tons of biomass [6], which proves to be economically burdensome at an industrial scale. It has been reported that there is potential to achieve an 80% reduction in the production costs of biocrude derived from microalgae by optimizing expenses associated with nutrients, water, and CO2 utilized during cultivation through low-cost alternatives [8,9]. A low-cost nutrient option is commercial fertilizers commonly employed in plant cultivation, which allows cost savings in large-scale cultivation, facilitates the preparation of the culture medium, and enhances the production of microalgae with a high nutritional value [7,10].

Authors such as Banerjee et al. [11] and Nordio et al. [12] reported that the replacement of traditional growing media with alternative media is a viable option due to the supply of essential nutrients (NPK) provided by inorganic fertilizers and the chemical species supplied. For example, inorganic nitrogen is essential for the synthesis of proteins, ribonucleic acid (RNA), and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which account for approximately 70–90%, 10–15%, and 1–2% of cellular nitrogen in microalgae, respectively. In inorganic fertilizers, the most common chemical species is ammonium (NH4+) [13], one of the most directly assimilable forms by microalgae since it does not need to be reduced, and once inside the cell, it is incorporated into nitrogen compounds, thus saving energy compared to nitrate (NO3) [14]. However, its concentration must be controlled to avoid toxicity [15,16].

Phosphorus is usually found in the form of phosphate (PO43−) and is essential for ATP formation. Also, it is a key component of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) and cell membranes (phospholipids) [13,17]. Potassium is a key ion in osmotic regulation and in the functioning of several enzymes involved in photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism. Inorganic fertilizers containing potassium, such as potassium chloride (KCl), help maintain ionic balance in microalgae cells, which is essential for the uptake of other nutrients [18]. On the other hand, the use of inorganic fertilizers as nutrients not only allows the decrease of costs for biomass production but can also increase cell productivity, as suggested by Banerjee et al. [11], who reached values of 0.6 g/L-d and increased the carbon, lipid, and hydrogen content.

Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) is a thermochemical process that converts wet biomass into a petroleum-like biocrude under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. Microalgal biomass is particularly suitable for HTL due to its high content of organic compounds, making it a promising feedstock for sustainable biofuel production. This would improve the efficiency of the HTL process by generating higher biomass to biocrude conversion, lower percentage of residues, and lower impurities than other biomass sources, thereby producing a better-quality biocrude [19]. Given these findings, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a commercial fertilizer on the cell productivity of Scenedesmus obliquus ATCC 11457® (S. obliquus) and on the biomass costs, considering only the cost of the culture medium. Within the study, the effect of fertilizers on microalgae growth, proximal composition, and biocrude characteristics is also discussed.

2. Bibliometric Analysis of the Use of Fertilizers as Microalgae Culture Media

Culture media prepared from analytical grade reagents are expensive and not cost-effective for large-scale production of microalgae; therefore, they tend to be replaced by cheaper alternatives, such as commercial fertilizers, because they contain important nutrients such as N, P, K, and some trace elements (Mg, Fe, Zn, Cu and Ca), which are essential for cell growth and maintenance [20]. Ribeiro et al. [21] reported that the combined use of fertilizers based on urea, ammonia, and nitrate in Chlorella sorokiniana cultures increased the production of high-value metabolites such as proteins, carotenoids, and organic acids without affecting biomass productivity compared to the reference medium BG-11. Therefore, it is suggested that the use of agricultural fertilizers allows for reducing costs without reducing the composition and nutritional values of microalgae. Due to the positive effects of fertilizers on microalgae cultivation, it was pertinent to analyze the technological advances of fertilizer-based media and the development of bioproducts from biomass. A systematic search was carried out in the scientific database Scopus under the search criteria established by the equation TITLE-ABS-KEY (“fertilizer” AND “microalgae” AND (“culture medium” OR “nutrients”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”)). The information collected was refined to avoid repetition of terms with abbreviations and hyphens [22]. VOSviewer version 1.6.16 (Leiden University, The Netherlands) and CorTextManager (INRAE, Noisy-le-Grand, France) types were used to develop the co-occurrence network and Sankey diagram, respectively [23].

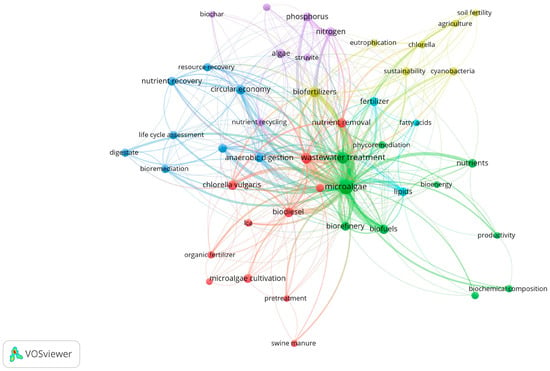

Figure 1 presents the author keyword co-occurrence map with seven topic clusters. The clusters identified showed the interconnection of fertilizers as nutrient sources for microalgae cultivation within various biotechnological domains. The map shows cluster keywords in blue related to circular economy approaches such as nutrient recovery, life cycle assessment, bioremediation, and resource recovery. The light blue and green clusters present terms such as biofuels, lipids, fatty acids, biochemical composition, and bioenergy. These are associated with the use of biomass to obtain value-added products through the biorefinery concept. In addition, the red and yellow clusters present keywords related to strains and culture media such as Chlorella vulgaris, cyanobacteria, and organic fertilizer. The purple cluster shows terms linked to essential nutrients for microalgae, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and struvite (a rich source of phosphorus) [24,25].

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence network of author keywords in publications on the use of fertilizers as microalgae culture media. Note: Seven theme clusters: yellow, blue, green, purple, red, and sky blue.

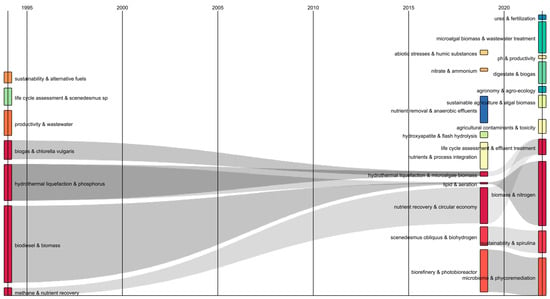

On the other hand, a Sankey diagram was constructed in order to analyze the interconnections between different attributes of the research database. This diagram allows us to represent the evolution and connection of different topics along a time scale in an efficient way [26]. Consequently, transformations in keyword combinations over time were identified and interrelated by gray color flows. Figure 2 shows keyword combinations between “biogas & nutrient recovery”, “hydrothermal liquefaction & phosphorus”, “biodiesel & biomass”, and “methane & nutrient recovery”, which converged with “hydrothermal liquefaction & microalgae biomass”, “lipid & aeration”, and “nutrient recovery & circular economy”, for the period 1995–2015. These flows indicate the 20-year evolution of the subject, which focused on the use of microalgae biomass to obtain energy products. Likewise, it was found that the keyword flow “hydrothermal liquefaction & microalgae biomass” and “nutrient recovery & circular economy” converged with “life cycle assessment & effluent treatment”. Therefore, hydrothermal liquefaction is suggested as a tool of interest in sustainable processes from microalgae [27]. It should be noted that the bibliometric analysis made it possible to identify the importance of fertilizers in the low-cost microalgae biorefinery, which represented a significant contribution to the structuring of the present work.

Figure 2.

Sankey diagram of author keywords in publications on the use of fertilizers as microalgae culture media.

3. Materials and Methods

The growth kinetics and cell productivity of S. obliquus were established in different culture media composed of commercial fertilizers and using Bold’s Basal Medium (BBM) as a control. The fertilizers used were Crecilizer®, Florilizer®, AcuaLeaf micros®, and AcuaLeaf macro®. These fertilizers were selected due to their high nutrient composition as reported by the manufacturer (Table 1). In this study, the cost analysis is limited to the nutritional component of the crop. The purpose was to determine the feasibility of using commercial fertilizers as an alternative to conventional inorganic salts in the growing medium, without estimating the total cost of biomass production.

Table 1.

Composition of the commercial fertilizers.

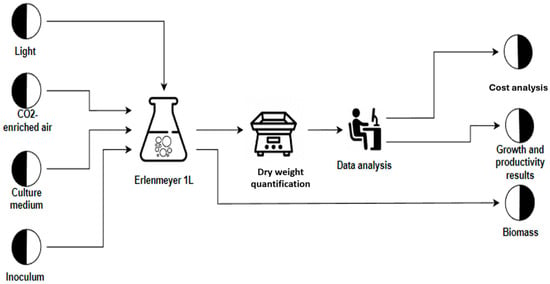

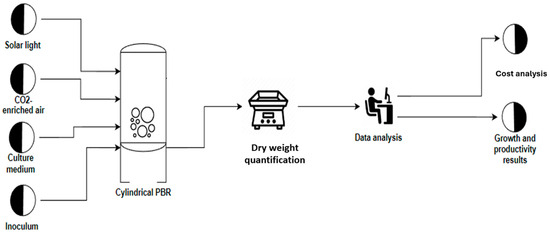

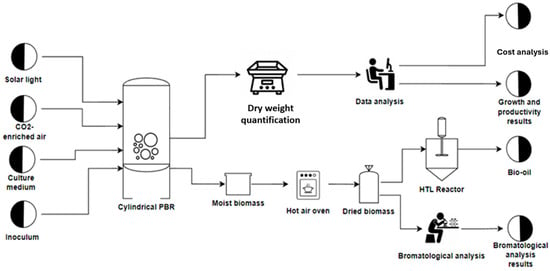

The tests were carried out in three phases: phase I, Laboratory scale (1 L Erlenmeyer) and phase II–III Pilot scale with cylindrical photobioreactors (PBRs) with a capacity of 20 L. In phase I (Figure 3), the following fertilizers were used: Crecilizer®, Florilizer®, AcuaLeaf macros®, and AcuaLeaf micro®, which will be called A, B, C, and D, respectively, using the quantities described in Table 2. In phase II, the growth kinetics for the two most effective treatments from phase I were established (Figure 4) (Table 3). In phase III (Figure 5), different concentration levels of the best fertilizer tested in phase II were evaluated: 5 mL/L (F-5) and 10 mL/L (F-10). Cell productivity, bromatological composition of the biomass, and biocrude yield were determined. A cost comparison was conducted to produce 1 kg of biomass with respect to the BBM culture medium.

Figure 3.

Flux diagram of phase I. Screening of fertilizer concentrations (1 L Erlenmeyer).

Table 2.

Description of the culture media used in the different phase I treatments.

Figure 4.

Flux diagram of phase II. Validation in 20 L photobioreactor.

Table 3.

Description of the culture media used in the different phase II and III treatments.

Figure 5.

Flux diagram of phase III. Scale-up and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL).

The fertilizer concentrations used in this study were defined based on the elemental nitrogen input, with the aim of adjusting the availability of N in the culture medium. In phase I, the initial dose was established by matching the nitrogen concentration provided by the fertilizer with the concentration of N present in the BBM medium. To do this, the information reported by the manufacturer and the composition of the reference medium were used. In phase II, these concentrations were validated in photobioreactor systems with a working volume of 20 L in order to confirm their behavior under operating conditions other than at the laboratory scale. Finally, in phase III, 5-fold and 10-fold increases of the base dose were evaluated to determine whether additional nitrogen availability enhanced microalgal growth. It is important to mention that, in this study, the cost of the culture medium was estimated for the purpose of determining the viability of using commercial fertilizers as an alternative to conventional inorganic salts. This estimate does not include the total cost of biomass production.

3.1. Growth Conditions

The fermentations were carried out in 12 h photoperiods, light intensity of 52 μmol/m2s, and a working volume of 1 L for phase I. The conditions of the pilot-scale tests were light intensity and natural photoperiods, with a working volume of 20 L. For all phases, the temperature was ambient, the initial concentration was 0.2 g/L, and the bubbling was air-enriched with synthetic CO2. Assays were performed in triplicate. Cell growth kinetics were determined by quantifying biomass through the dry weight method, with samples taken every 48 h [28].

3.2. Proximal Biomass Analysis

The proximal analysis of the biomass obtained in phase III was conducted to examine the compositional changes resulting from varying concentrations of fertilizer in the microalgae culture medium. The percentage of carbohydrates, proteins, fat, fiber, and ashes was analyzed under the standards of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC) at 923.03, 990.03, 920.39, and 926.09, respectively [3].

3.3. Production of Biocrude Through HTL

The biomass obtained in phase III was used to produce biocrude by HTL using a 250 mL PARR4576 B reactor (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA). The conditions under which the biocrude was produced were 3:1 solvent–algae ratio, temperature 300 °C, K2CO3 catalyst, and residence time of 45 min, using a small amount of organic solvent. The conditions are protected under US Patent US 11814586B2 [29]. These conditions allow for obtaining positive operating profits, with a view to the financial feasibility of the process [30].

The amount of biocrude in each reaction was determined by gravimetry. The Higher Heating Value (HHV) was quantified by an Automatic Isoperibol Calorimeter Parr 6400 (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA) under ASTM D240-19 [31]. The API gravity was measured by correlation based on density according to ASTM D4052-18 [32], and the metals content was measured by ICP-OES ASTM D5185-18 [33].

3.4. Experiment Design

To establish the effect of the total replacement of the BBM culture medium by different fertilizers on cell growth and productivity, a single-factor experimental design was used, where the factor evaluated was the nutrients in the culture medium (phase I). Specific combinations of fertilizers were tested as described in Table 2.

In phase II, the type of fertilizer (Crecilizer® or Florilizer®) was employed as a single-factor experimental design. In phase III, the single-factor design considered was fertilizer concentration at two levels: 5 mL/L (F-5) and 10 mL/L (F-10). Each assay was performed in triplicate for a total of 21, 6, and 6 experimental units for phases I, II, and III, respectively. For the statistical analysis, STATGRAPHICS Centurion Software version XVI was used. The statistical analysis of the results was carried out using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 95% confidence level. The assumptions of the ANOVA were verified through the quantitative tests of Shapiro–Wilk, Kolmogorov, Levene, and Durbin–Watson. The Least Significant Difference (LSD) multiple range test was used to establish treatments that exhibited a significant effect on response variables. The error bars presented in the graphs represent the statistical error observed among the replicates for each treatment.

4. Results and Discussion

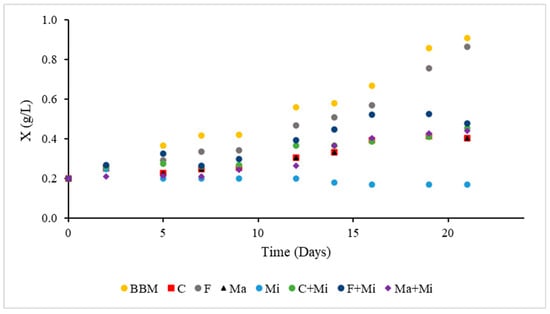

The kinetic growth of S. obliquus under the different treatments of the design of experiments on a laboratory scale (phase I) is observed in Figure 6. The highest final cell concentrations of 0.86 and 0.88 g/L were observed in treatments C and F, respectively. The growth kinetics of these two treatments present an exponential phase between the first and nineteenth days of growth. Treatments containing fertilizer Ma showed final cell concentrations below 0.50 g/L, implying that the nutrient composition or quantity in these treatments is inadequate to support cell development. It was observed that the treatment with fertilizer Mi presented inhibition in cell growth; possibly, this can be attributed to the property of the dark color of the fertilizer, which when adding the 5 mL/L, dispersed its color throughout the crop, blocking the light necessary for photosynthesis and diminishing the capacity to generate the energy necessary for cell growth and development [34].

Figure 6.

Growth kinetics of S. obliquus in laboratory-scale culture using different fertilizer-based media.

The higher growth observed in treatments C and F may be attributed to the higher nitrogen content of the fertilizer used (100 y 200 N (g/L), respectively), compared to the other fertilizers, which contained approximately 11.30 N (g/L). Nitrogen, together with phosphorus and potassium, is one of the most essential macronutrients for microalgae growth, as it enables the synthesis of key biomolecules such as DNA, RNA, chlorophyll, and proteins. Its availability is therefore crucial to prevent interruptions in photosynthesis, protein synthesis, and cell division processes [24,25].

The similar behavior between treatments C and F could be explained by their identical NPK ratios, while slight differences in performance might result from other components in their formulations, such as buffering agents or micronutrients not specified by the supplier. If the fertilizers contain different nitrogen species (e.g., nitrate, ammonium, or urea), these could also influence assimilation rates and growth efficiency, as microalgae exhibit varying preferences and uptake capacities for each form. Likewise, treatments C + Mi and F + Mi presented final cell concentrations lower than 0.59 g/L, indicating that the optical barrier generated by fertilizer Mi negatively affected light efficiency and, therefore, cell yield compared to the other treatments without this interference.

Authors such as Murprayana et al. [10], Banerjee et al. [11], and Nordio et al. [12] reported that evaluating various fertilizer concentrations as a replacement of the traditional culture medium for strains such as Odontella aurita, Scenedesmus sp., and Nannochloropsis sp. resulted in an upward trend in cell growth comparable to that found in the present investigation. This behavior suggests that certain fertilizer concentrations offer adequate nutrient availability, promoting cell proliferation and proper development of different microalgae strains under controlled conditions.

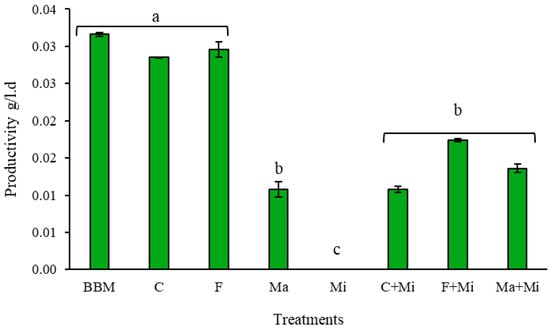

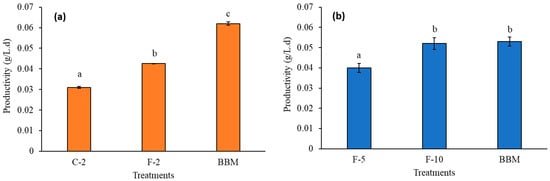

Figure 7 displays the cell productivity obtained in the different treatments in phase I. According to the ANOVA, significant differences were observed among the mean productivity levels. Treatments C and F exhibited cell productivity statistically comparable to that of the control treatment BBM, suggesting that fertilizers used in both treatments supply the necessary nutrients to maintain cell productivity, as suggested by Banerjee et al. [11]. Additionally, NPK content (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) in fertilizers has variability among manufacturers and also incorporates trace elements such as potassium (K), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn), making them attractive feedstock for microalgae cell growth [35,36]. The treatments with Mi showed a productivity lower than 0.02 g/L-d, indicating that the tested concentrations did not supply the essential nutrients in sufficient amounts to support effective microalgae growth.

Figure 7.

Productivity per treatment at laboratory scale. The same letters in the figure correspond to statistically homogeneous groups according to the LSD multiple range test, with a confidence level of 95%.

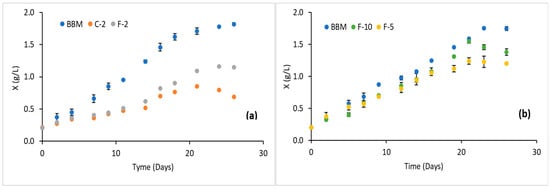

Figure 8a shows the growth kinetics for each of the treatments in phase II. The highest cell concentration obtained was 1.82 g/L for the control treatment (BBM), followed by treatments F and C with 1.23 and 0.80 g/L, respectively. These values are comparable with those reported by Koley et al. [37] for Scenedesmus accuminatu in open tank fermentations also using fertilizer-based culture media and varying different operating conditions, reaching maximum concentrations of 1.12 g/L. It was observed that the final cell concentration obtained in phase II was higher than that obtained with the same fertilizers in phase I (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 8.

Growth kinetics of S. obliquus. (a) Phase II and (b) phase III.

It is important to note that the scale-up from Erlenmeyer flasks to 20 L photobioreactors introduced inherent environmental variations, including differences in light distribution, mixing, and mass transfer. Although fertilizer concentration was maintained as the primary variable under study, the observed changes in growth kinetics likely resulted from the combined effects of nutrient availability and operational differences associated with the cultivation system.

Authors such as Koley et al. [38] reported variations in cell productivity when different designs or materials of the culture systems were used. This may be due to changes in the transmission of light to the cells inside the culture, and the large contact surface that the light achieves with the microalgae. Some systems maximize light uptake and, consequently, improve the efficiency of the photosynthetic process, which increases biomass productivity and stimulates the formation and accumulation of some secondary metabolites of economic importance, such as lipids used in the production of biocrude oil [39].

Figure 8b shows the cell growth in phase III when Florilizer® fertilizer was used in different concentrations. The progressive increase in cell concentration indicates that the treatments evaluated at different concentrations were adequate for cell growth. However, after day nineteen, the F-10 treatment showed a higher concentration than F-5, reaching 1.5 g/L, whereas F-5 remained around 1.1 g/L. This suggests that higher fertilizer concentration in F-10 may enhance cell growth during the late exponential phase. This suggests that the nutrient concentration in the medium has a direct effect on cell growth, considering not only NPK components but also the contribution of micronutrients present in the fertilizer. It is important to highlight that none of the concentrations evaluated in phases I, II, or III using Florilizer® presented any inhibition of cell growth. This is possibly due to the concentration and composition of the nutrients. Nitrogen is found in this fertilizer in various assimilable forms for the microalgae (ammonium and nitrate), which allows different stages and absorption rates, optimizing the availability of this nutrient according to the metabolic needs of the microalgae [40]. For example, ammonium avoids energy consumption by not having to reduce nitrate/nitrite to be incorporated into the synthesis of essential molecules (amino acids and proteins) through the GS-GOGAT cycle by the enzymes glutamine synthetase (GS)-glutamate synthetase (GOGAT) and also by not producing the enzymes nitrate reductase (NR) and nitrite reductase (NiR) [41,42], leading to reduced expenditure of ATP and reducing compounds such as NADPH. The chemical form of nitrogen plays a crucial role in its assimilation, as microalgal cells preferentially utilize specific nitrogen species. Nevertheless, concentrations above 100 mg/L can lead to cytotoxic effects [43]. Additionally, prolonged exposure is toxic, as it disrupts cellular homeostasis and induces oxidative damage, ultimately inhibiting cell growth [42,44,45,46,47,48].

Potassium and phosphorus are found in the fertilizer in the forms of K2O and P2O5, which react to release the ions in forms that microalgae can absorb. Potassium ions (K+) are released through the solubilization of K2O (Equation (1)), while P2O5 contributes to the formation of phosphate ions (H2PO4−/HPO42−) (Equations (2)–(5)), which are more bioavailable and efficiently assimilated by microalgae for metabolic functions and growth [13,49].

Figure 9 displays the cell productivity obtained in the different treatments in phases II and III. In both phases, there were statistically significant differences between the treatments, and it was evident that the Florilizer® allows higher productivity than Crecilizer® (Figure 9a). When the concentration of Florilizer® increases, it is possible to achieve productivity levels comparable to those observed with the BBM control medium (Figure 9b), suggesting that the F-10 treatment can supply the nutritional needs of S. obliquus. The productivity obtained from treatment F-10 (0.05 g/L·d) was 1.7 times higher compared to that reported by Koley et al. [38] (0.03 g/L·d), indicating that Florilizer® fertilizer possibly promotes greater uptake of nutrient species for S. obliquus strain than other commercial fertilizers.

Figure 9.

Productivity per treatment in phases (a) II; (b) III. The same letters in the figure correspond to statistically homogeneous groups according to the LSD multiple range test, with a confidence level of 95%.

On the other hand, Table 4 presents the results of the proximate analysis performed on the biomass from F-5 and F-10 treatments in phase III. A higher fertilizer concentration results in increases in the percentage of protein, fiber, and fat, but decreases in the percentage of carbohydrates. Greater concentrations of assimilable nitrogen compounds, provided by the fertilizer, enhance the production of nitrogen-rich macromolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, as reported previously [50,51,52]. The increased protein content in the biomass, as obtained in the F-10 biomass, may be associated with a reduction in the synthesis of energy storage compounds, such as carbohydrates, as suggested by [38,53]. The higher fiber content observed in the F-10 treatment could be associated with a hyperosmotic effect resulting from high nutrient concentration. Furthermore, previous studies indicate that nutrient availability can modulate the synthesis and composition of the cell wall [54] and, in microalgae, culture conditions influence the accumulation of both structural polysaccharides and wall glycoproteins [55].

Table 4.

Results of the proximate analysis of the biomass from phase III.

A cost comparison was made for the production of 1 kg of dry biomass (considering only the contribution of medium used) between the BBM control culture medium and the treatments evaluated in phase III. The cost reduction trend can be compared with that published by Rofidi [56], who reports that media prepared from NPK fertilizers can be approximately 49.39 times less expensive than analytical media such as F/2 medium [57], a higher reduction than that obtained in the study. On the other hand, when analyzing the effect of fertilizer concentration on biomass production costs, during phase III (Figure 9b), it was observed that, although the culture medium cost increased due to the higher amount of fertilizer used, the F-5 treatment still presented a lower culture cost compared to BBM. It should be noted that the estimated values were 60.93 USD/kg for the BBM medium, 40.22 USD/kg for F-5, and 64.35 USD/kg for F-10. In addition, F-5 had the lowest cost per unit of biomass, demonstrating its competitiveness as a productive alternative. This suggests that F-5 can be considered a cost-effective alternative culture medium, allowing a reduction of up to 66% in production costs per unit of biomass, even with a slight decrease in productivity.

Table 5 presents the results of the biocrude obtained in the liquefaction process of the biomass obtained from the phase III treatments. The data reveal that, although there are differences in the protein content in the biomass, the HHV in the biocrude obtained remains around 34–35 MJ/kg for both samples, a value comparable with conventional biodiesel [58]. Furthermore, the density, expressed in °API, classifies biocrude oil as heavy crude oil [59].

Table 5.

Experimental results from the thermal liquefaction of biomass harvested in phase III.

Additionally, the high content of ashes in the evaluated microalgae could serve as a catalyst in the liquefaction process, avoiding the addition of basic catalysts, by alkaline metals content like calcium (11.8 w/w%), potassium (5.8 w/w%), magnesium (1.5 w/w%), and sodium (0.7 w/w%) as determined by ICP-OES. This suggests that the alkali and alkaline earth metals naturally present in the biomass can promote catalytic reactions during thermal conversion. Such intrinsic catalytic behavior has also been reported for other lignocellulosic materials. For example, Feng et al. [60] reported that K and Ca compounds present in white pine bark ash catalyzed the conversion of the bark into biocrude. The authors stated that de-ashing of the bark reduced the biocrude yield compared to the raw bark. Table 6 shows a general composition of the main functional groups for the biocrudes obtained through HTL by GC–MS analyses, in which the different compounds obtained were grouped by families. These compositions could vary in terms of the protein content in the microalgae. These results, according to the NIST database installed in the chromatograph, are for coincidences of signals >95%.

Table 6.

Chemical composition of the biocrudes from GC–MS analyses.

Table 6 also shows a high content of alkanes like hexadecenoic acid, phytol, heptadecane, hexadecane, and pentadecane, representing around 40% of the biocrude. It should be noted that biomass with higher carbohydrate content (treatment with F-5) will promote the formation of alkanes (57.49%) and ketones (3.68%) in the biocrude, which are not unstable compared to nitrogenous compounds [3]. Also, the results confirm that a high nitrogen content in the biocrude is observed due to a higher number of compounds such as quinoline and pyridines. Considering these results, the implementation of an upgrading process is essential to obtain liquid commercial fuels—such as diesel or gasoline—with reduced heteroatom content. On the other hand, the biocrude obtained from the biomass produced in the F-5 treatment shows a low cost of around 50% less than treatment with BBM. This results in a lower biocrude production cost, given that microalgae represent 40% of the total cost, leading to an estimated price of 45–50 USD per barrel [30].

5. Conclusions

The culture media used in treatments C and F showed similar growth performance to the BBM medium. However, the results showed that S. obliquus growth was affected by both the type of fertilizer and the scale-up process, indicating that fertilizer-based medium could replace BBM medium.

Commercial fertilizers are not only composed of NPK but also a series of trace elements that, when absorbed by the microalgae, can increase the ash content in the resulting biomass compared to that obtained with the BBM control culture medium. Increasing the fertilizer concentration is viable, as observed in the F-5 treatment. However, higher concentrations cause the biomass production costs associated with the culture medium to exceed those of the BBM medium. In addition, the biomass produced exhibited higher protein content and lower carbohydrate levels, which are characteristics considered undesirable in the production of commercial biofuels.

The cost of microalgal biomass could represent as much as 40% of the total production cost of biocrude via HTL. The use of commercial fertilizers as an alternative nutrient source for microalgae cultivation represents a promising strategy to improve the economic feasibility of biocrude production through HTL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.M., F.H.-T., G.J.V., and A.A.S.; software, A.M.M. and F.H.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.M. and F.H.-T.; writing—review and editing, A.M.M., F.H.-T., and G.J.V.; supervision, D.O., G.J.V., and A.A.S.; project administration, D.O., G.J.V., and A.A.S.; funding acquisition, G.J.V. and A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to thank the Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación—Minciencias (Colombia) for the financing of the program “Precommercial Biofactory for obtaining Microalgae Bioproducts from the Valorization of CO2 from Industrial Sources BIOFACO2”, contract No. 80740-440-2021 and project code 86018.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Colombian Ministry of Science, Cementos Argos, Universidad EAFIT, and Universidad de Antioquia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HTL | Hydrothermal liquefaction |

| PBR | Cylindrical photobioreactors |

| BBM | Bold’s Basal Medium |

| HHV | Higher Heating Value |

| AOAC | Association of Official Agricultural Chemists |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| LSD | Least Significant Difference |

References

- Brasil, B.S.A.F.; Silva, F.C.P.; Siqueira, F.G. Microalgae Biorefineries: The Brazilian Scenario in Perspective. New Biotechnol. 2017, 39, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, M.; Moreno, J.M.M.; García, J.J.H.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.J. Application of Microalgae in Cauliflower Fertilisation. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Ocampo, D.; Vargas, G.J.; Ríos, L.A.; Sáez, A.A. Nitrogen Content Reduction on Scenedesmus Obliquus Biomass Used to Produce Biocrude by Hydrothermal Liquefaction. Fuel 2021, 305, 121592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.W.R.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Ting, H.-Y.; Koji, I.; Show, P.L. Digitalised Prediction of Blue Pigment Content from Spirulina Platensis: Next-Generation Microalgae Bio-Molecule Detection. Algal Res. 2024, 83, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mahari, W.A.; Wan Razali, W.A.; Manan, H.; Hersi, M.A.; Ishak, S.D.; Cheah, W.; Chan, D.J.C.; Sonne, C.; Show, P.L.; Lam, S.S. Recent Advances on Microalgae Cultivation for Simultaneous Biomass Production and Removal of Wastewater Pollutants to Achieve Circular Economy. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acién Fernández, F.G.; Fernández Sevilla, J.M.; Molina Grima, E. Costs Analysis of Microalgae Production. In Biofuels from Algae, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780444641922. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, J.C.D.; Sydney, E.B.; Ferrari, L.; Tessari, A.; Soccol, C.R. Chapter 2—Culture Media for Mass Production of Microalgae. In Biofuels from Algae, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780444641922. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.M.; Cho, K.; Kang, N.S.; Kim, E.S.; Ki, H.; Choi, G.; An, H.S.; Go, G.M. Development of a Cost-Effective Medium Suitable for the Growth and Fucoxanthin Production of the Microalgae Odontella Aurita Using Jeju Lava Seawater and Agricultural Fertilizers. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 188, 107310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién Fernández, F.G.; Gómez-Serrano, C.; Fernández-Sevilla, J.M. Recovery of Nutrients From Wastewaters Using Microalgae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murprayana, R.; Stella, M.; Pukan, H.; Prastiwi, T.; Widjaja, A.; Wirawasista, H. The Effects of UV-C and HNO2 Mutagen, PH and the Use of Commercial Fertilizers on the Growth of Microalgae Botryoc Brauniioccus. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1053, 012095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Guria, C.; Maiti, S.K. Fertilizer Assisted Optimal Cultivation of Microalgae Using Response Surface Method and Genetic Algorithm for Biofuel Feedstock. Energy 2016, 115, 1272–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordio, R.; Viviano, E.; Sánchez-Zurano, A.; Hernández, J.G.; Rodríguez-Miranda, E.; Guzmán, J.L.; Acién, G. Influence of PH and Dissolved Oxygen Control Strategies on the Performance of Pilot-Scale Microalgae Raceways Using Fertilizer or Wastewater as the Nutrient Source. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. Revisiting Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Metabolisms in Microalgae for Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 144590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Q. Microalgae-Based Nitrogen Bioremediation. Algal Res. 2020, 46, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Xia, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Synergistic Treatment of Digested Wastewater with High Ammonia Nitrogen Concentration Using Straw and Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 412, 131406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, P.; Addy, M.; Zhang, R.; Deng, X.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Hussain, F.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Carbon-Dependent Alleviation of Ammonia Toxicity for Algae Cultivation and Associated Mechanisms Exploration. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyhrman, S.T. The Physiology of Microalgae; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.S.; Al Mahmud, J.; Hossen, M.S.; Masud, A.A.C.; Moumita; Fujita, M. Potassium: A Vital Regulator of Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Sharma, K.; Haider, M.S.; Toor, S.S.; Rosendahl, L.A.; Pedersen, T.H.; Castello, D. The Role of Catalysts in Biomass Hydrothermal Liquefaction and Biocrude Upgrading. Processes 2022, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baouchi, A.; Boulif, R. Agriculture Fertilizer-Based Media for Cultivation of Marine Microalgae Destined for Biodiesel Production. J. Energy Manag. Technol. 2020, 4, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.M.; Roncaratti, L.F.; Possa, G.C.; Garcia, L.C.; Cançado, L.J.; Williams, T.C.R.; dos Santos Alves Figueiredo Brasil, B. A Low-Cost Approach for Chlorella Sorokiniana Production through Combined Use of Urea, Ammonia and Nitrate Based Fertilizers. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 9, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağbulut, Ü.; Sirohi, R.; Lichtfouse, E.; Chen, W.H.; Len, C.; Show, P.L.; Le, A.T.; Nguyen, X.P.; Hoang, A.T. Microalgae Bio-Oil Production by Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal Liquefaction: Mechanism and Characteristics. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 376, 128860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Espinosa, E.A.; Bellettre, J.; Tarlet, D.; Montillet, A.; Piloto-Rodríguez, R.; Verhelst, S. Experimental Investigation of Emulsified Fuels Produced with a Micro-Channel Emulsifier: Puffing and Micro-Explosion Analyses. Fuel 2018, 219, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Dai, D.; Li, S.; Qv, M.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Huang, L.Z.; Zhu, L. Responses of Microalgae under Different Physiological Phases to Struvite as a Buffering Nutrient Source for Biomass and Lipid Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moed, N.M.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Struvite as Alternative Nutrient Source for Cultivation of Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 56, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, A.; Chakma, S. A Bibliometric and Visual Analysis of Contaminant Transport Modeling in the Groundwater System: Current Trends, Hotspots, and Future Directions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 32032–32051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, E.; Beltrán, V.V.; Gómez, E.A.; Ríos, L.A.; Ocampo, D. Hydrothermal Liquefaction Process: Review and Trends. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 7, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Ossa, E.A.; Vargas, G.J.; Sáez, A.A. Efecto de Las Bajas Concentraciones de Nitratos y Fosfatos Sobre La Acumulación de Astaxantina En Haematococcus Pluvialis UTEX 2505. Inf. Tecnol. 2019, 30, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo Echeverri, D.; Rios, L.A.; Gómez Mejía, E.A.; Vargas Betancur, G.J. Solvothermal Liquefaction Process from Biomass for Biocrude Production. U.S. Patent 11814586B2, 14 November 2023. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US11814586B2/en (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Ríos, L.A.; Vargas, G.J.; Ocampo, D.; Elkin, A.G. Effects of the Use of Acetone as Co-Solvent on the Financial Viability of Bio-Crude Production by Hydrothermal Liquefaction of CO2 Captured by Microalgae. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 89, 102960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D240; Standard Test Method for Heat of Combustion of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels by Bomb Calorimeter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D4052; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, and API Gravity of Liquids by Digital Density Meter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D5185; Standard Test Method for Multielement Determination of Used and Unused Lubricating Oils and Base Oils by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Parveen, A.; Bhatnagar, P.; Gautam, P.; Bisht, B.; Nanda, M.; Kumar, S.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Kumar, V. Enhancing the Bio—Prospective of Microalgae by Different Light Systems and Photoperiods. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihantini, N.B.; Prihantini, N.B.; Rakhmayanti, N.; Handayani, S. Biomass Production of Indonesian Indigenous Leptolyngbya Strain on NPK Fertilizer Medium and Its Potential as a Source of Biofuel. Evergreen 2020, 7, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, R.; Hidayati, N.A. Effect of Commercial NPK Fertilizer on Growth and Biomass of Navicula Sp. and Nannochloropsis Sp. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 762, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, S.; Mathimani, T.; Bagchi, S.K.; Sonkar, S.; Mallick, N. Microalgal Biodiesel Production at Outdoor Open and Polyhouse Raceway Pond Cultivations: A Case Study with Scenedesmus Accuminatus Using Low-Cost Farm Fertilizer Medium. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 120, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, S.; Sonkar, S.; Kumar, S.; Patnaik, R.; Mallick, N. Development of a Low-Cost Cultivation Medium for Simultaneous Production of Biodiesel and Bio-Crude from the Chlorophycean Microalga Tetradesmus Obliquus: A Renewable Energy Prospective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-baset, A.; Matter, I.A.; Ali, M.A. Enhanced Scenedesmus Obliquus Cultivation in Plastic-Type Flat Panel Photobioreactor for Biodiesel Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.H.M.; Hurin, J.O.B.S.; Froymson, R.E.A.E.; Athews, T.E.J.M. Functional Divergence in Nitrogen Uptake Rates Explains Diversity—Productivity Relationship in Microalgal Communities. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, D.W.; Hurd, C.L.; Beardall, J.; Hepburn, C.D. Restricted Use of Nitrate and a Strong Preference for Ammonium Reflects the Nitrogen Ecophysiology of a Light-Limited Red Alga. J. Phycol. 2014, 51, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, S.C.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; Wacker, A.; Spijkerman, E. Nitrate or Ammonium: Influences of Nitrogen Source on the Physiology of a Green Alga. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, P.; Guo, Y.; Kang, H.; Lefebvre, C.; Loh, K. Enhancing Microalgae Cultivation in Anaerobic Digestate through Nitrification. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronzucker, H.J.; Glass, A.D.M.; Siddiqi, M.Y. Inhibition of Nitrate Uptake by Ammonium in Barley. Analysis of Component Fluxes. Plant Physiol. 1999, 120, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Helguen, S.; Maguer, J.-F.; Caradec, J. Inhibition Kinetics of Nitrate Uptake by Ammonium in Size-Fractionated Oceanic Phytoplankton Communities: Implications for New Production and f-Ratio Estimates. J. Plankton Res. 2008, 30, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbitani, G.; Carfagna, S. Ammonium Utilization in Microalgae: A Sustainable Method for Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhai, J.; Wei, H.; Wang, Q. Effect of Ammonium Nitrogen on Microalgal Growth, Biochemical Composition and Photosynthetic Performance in Mixotrophic Cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 273, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, U.; Altınba, M. Evaluating Ammonia Toxicity and Growth Kinetics of Four Different Microalgae Species. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, S.; Hussain, J.; Zeb, I.; Kong, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Identification of Potassium Transport Proteins in Algae and Determination of Their Role under Salt and Saline-Alkaline Stress. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.; In, Y.; Park, K.; Kim, Y.; Keun, H.; Suk, O.; Choo, K.; Bo, Y. Incidence of Nonunion after Surgery of Distal Femoral Fractures Using Contemporary Fixation Device: A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2020, 141, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, F.; Van, T.C.; Brown, R.; Rainey, T. Nitrogen and Sulphur in Algal Biocrude: A Review of the HTL Process, Upgrading, Engine Performance and Emissions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 181, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, S.; Hu, T.; Nugroho, Y.K.; Yin, Z.; Hu, D.; Chu, R.; Mo, F.; Liu, C.; Hiltunen, E. Effects of Nitrogen Source Heterogeneity on Nutrient Removal and Biodiesel Production of Mono- and Mix-Cultured Microalgae. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 201, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Nerantzis, E. Microalgae for High-Value Compounds and Biofuels Production: A Review with Focus on Cultivation under Stress Conditions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, M.; Hoefgen, R.; Roessner, U.; Persson, S.; Khan, G.A. Feeding the Walls: How Does Nutrient Availability Regulate Cell Wall Composition? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, G.; Pereira, R.N. Effects of Innovative Processing Methods on Microalgae Cell Wall: Prospects towards Digestibility of Protein-Rich Biomass. Biomass 2022, 2, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofidi, I. Commercial Fertilizer as Cheaper Alternative Culture Medium for Microalgal Growth (Chlorella Sp.). Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lananan, F.; Jusoh, A.; Ali, N.; Lam, S.S.; Endut, A. Effect of Conway Medium and f/2 Medium on the Growth of Six Genera of South China Sea Marine Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 141, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Relationships Derived from Physical Properties of Vegetable Oil and Biodiesel Fuels. Fuel 2008, 87, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Palou, R.; Mosqueira, M.d.L.; Zapata-Rendón, B.; Mar-Juárez, E.; Bernal-Huicochea, C.; de la Cruz Clavel-López, J.; Aburto, J. Transportation of Heavy and Extra-Heavy Crude Oil by Pipeline: A Review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2011, 75, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yuan, Z.; Leitch, M.; Xu, C.C. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Barks into Bio-Crude—Effects of Species and Ash Content/Composition. Fuel 2014, 116, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).