Author Contributions

Formal analysis, F.Z.; data curation, F.Z., Z.Y. and M.Y.; methodology, M.Y.; validation, Z.Y., J.C. and R.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y., M.Y., J.C., R.Z. and Y.Z.; supervision, J.C. and Y.Z.; project administration, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

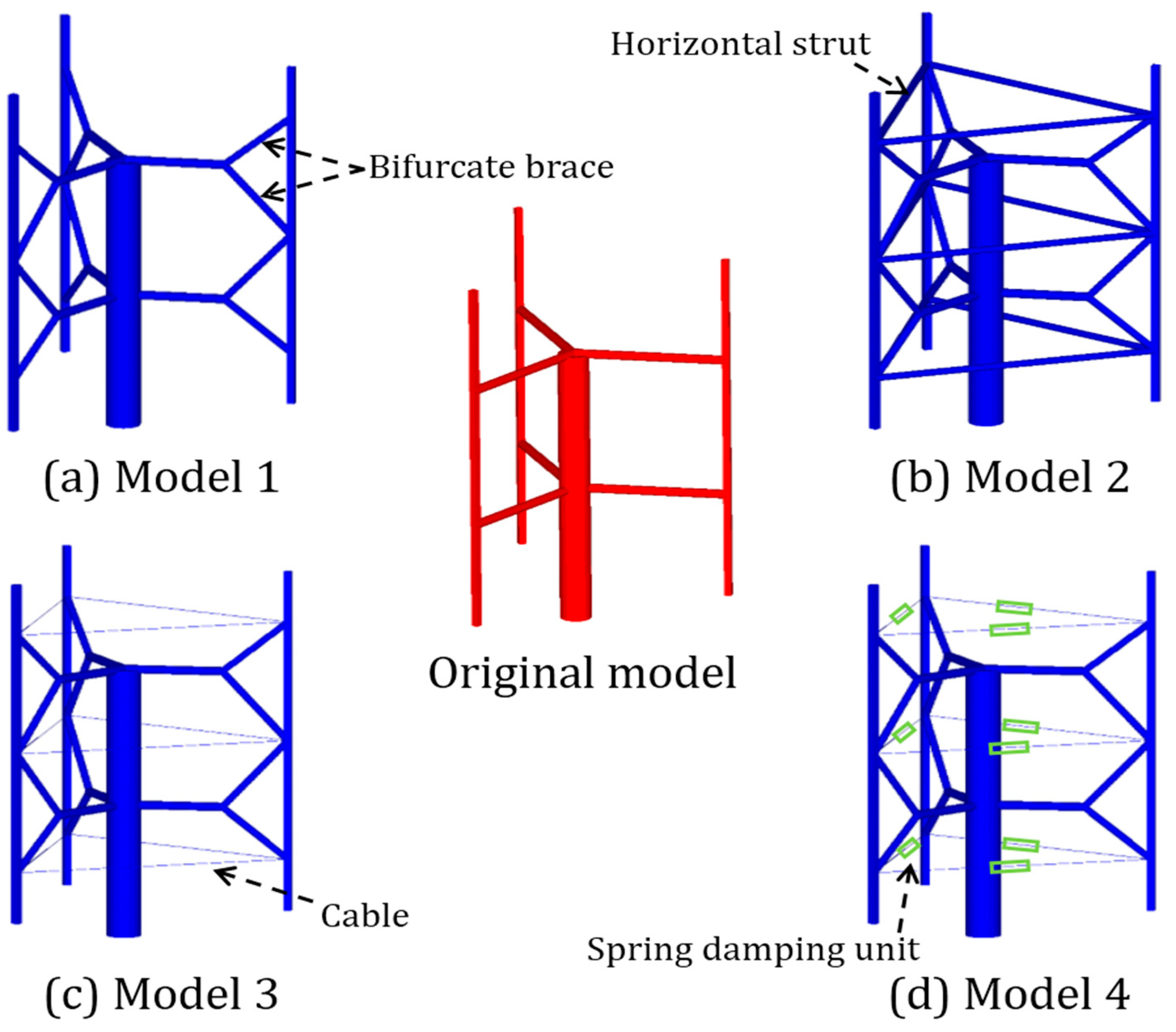

Figure 1.

Schematic models of the original and four optimized VAWTs.

Figure 1.

Schematic models of the original and four optimized VAWTs.

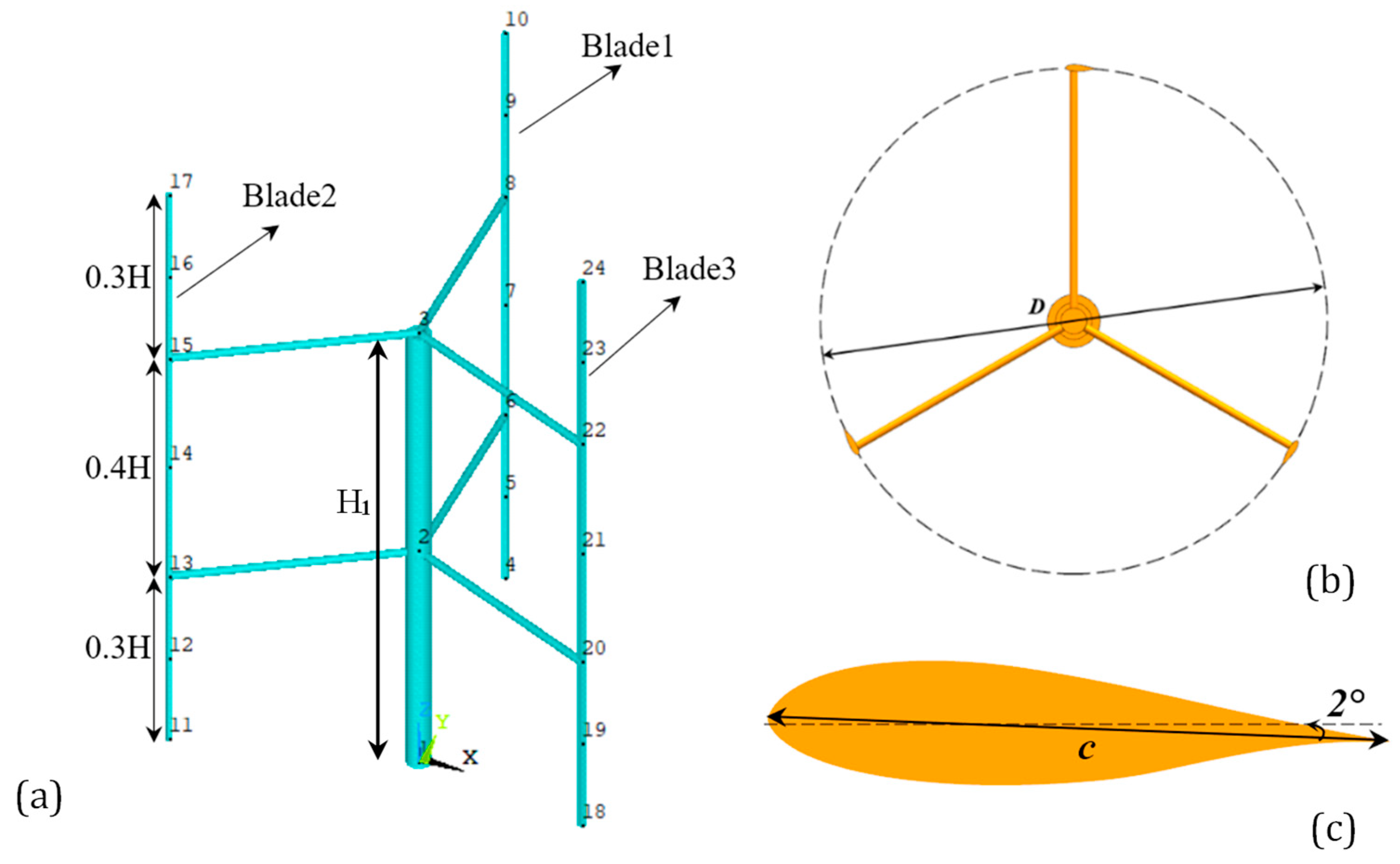

Figure 2.

Configuration of original VAWT model: (a) overview; (b) top view; (c) blade airfoil of DU-06-W-200 with a pitch angle of 2°.

Figure 2.

Configuration of original VAWT model: (a) overview; (b) top view; (c) blade airfoil of DU-06-W-200 with a pitch angle of 2°.

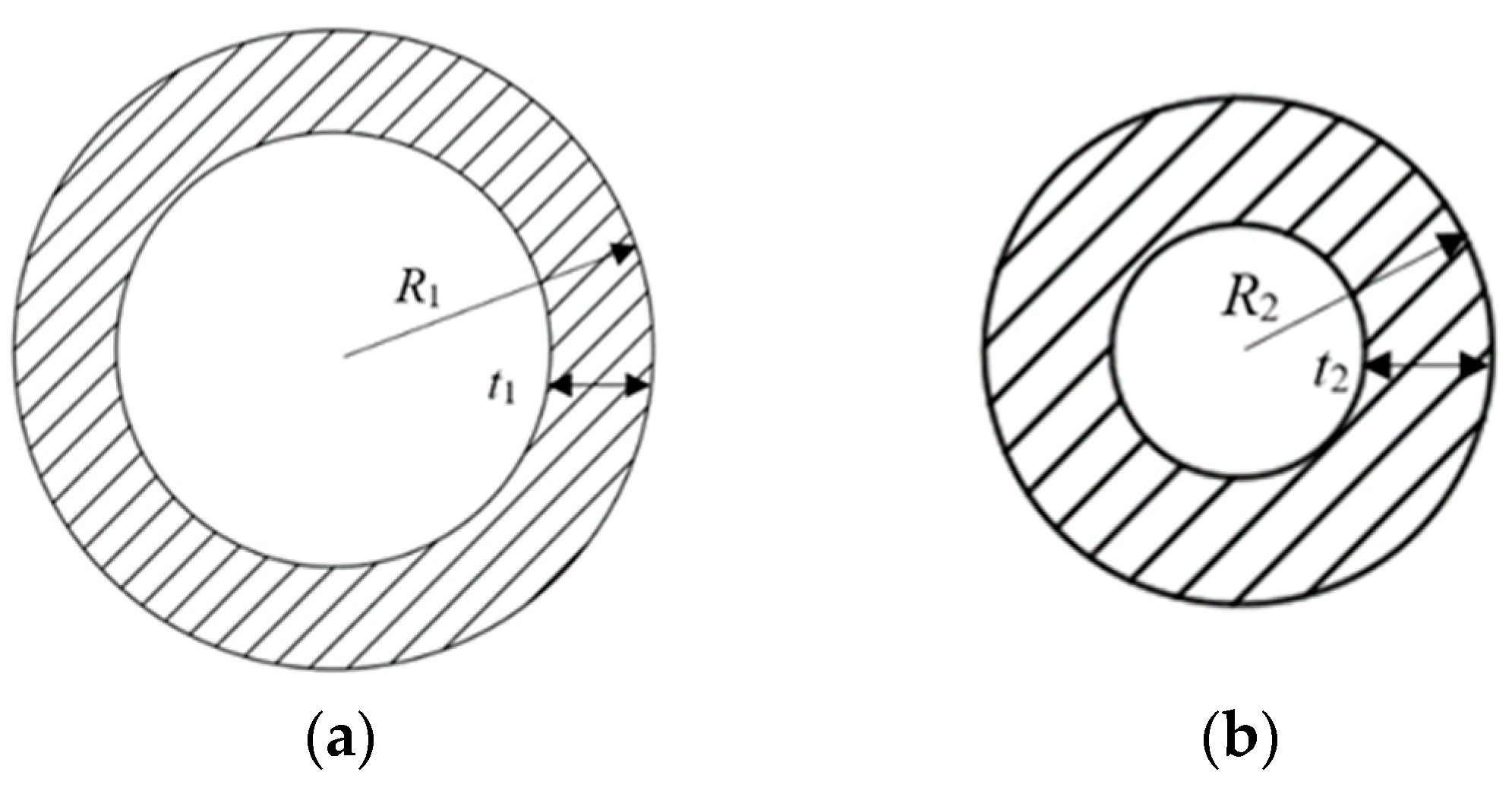

Figure 3.

Sections of shaft and strut: (a) shaft: m, m; (b) strut: m, m.

Figure 3.

Sections of shaft and strut: (a) shaft: m, m; (b) strut: m, m.

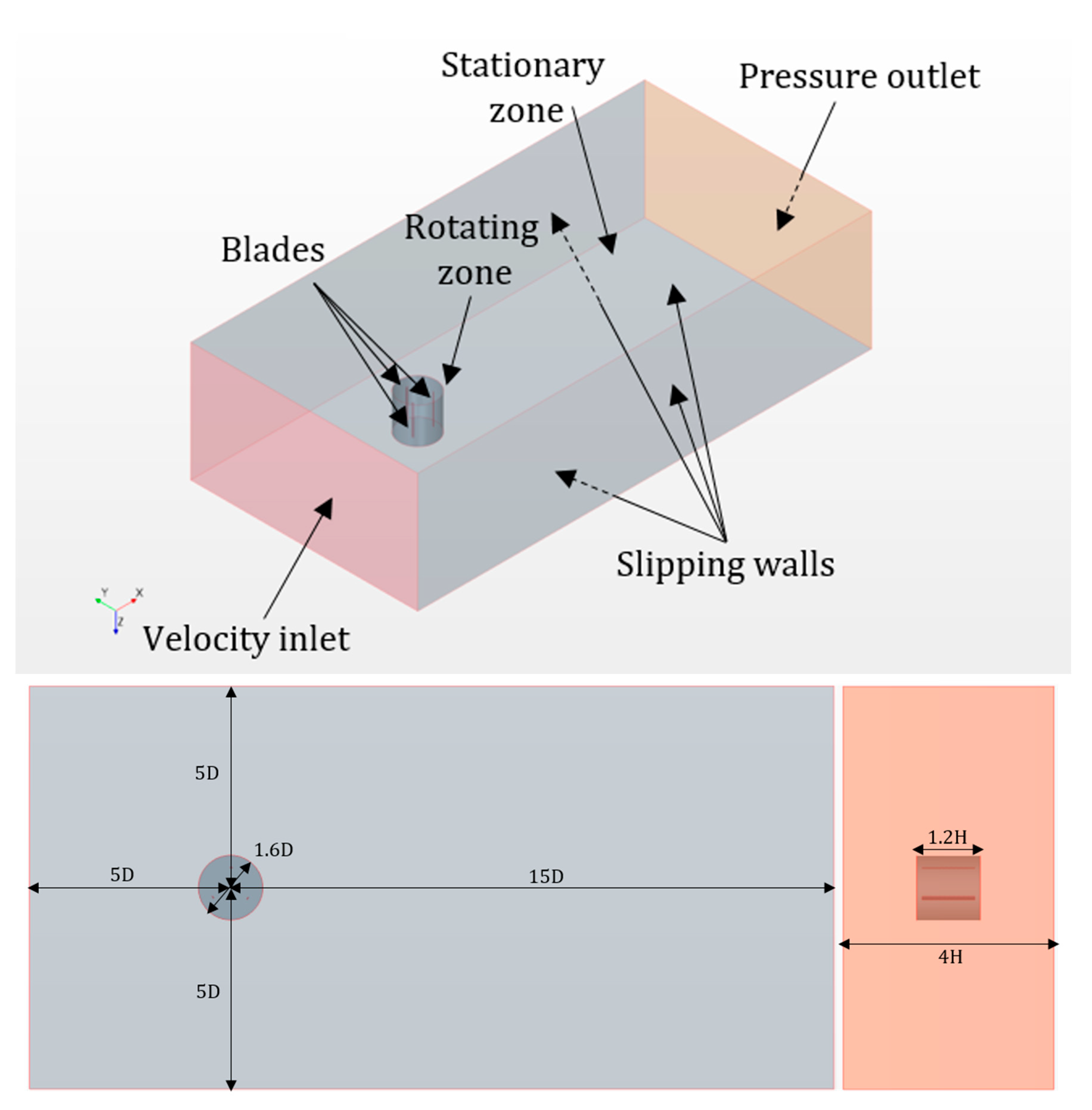

Figure 4.

The layout of VAWT simulation in 3D-CFD.

Figure 4.

The layout of VAWT simulation in 3D-CFD.

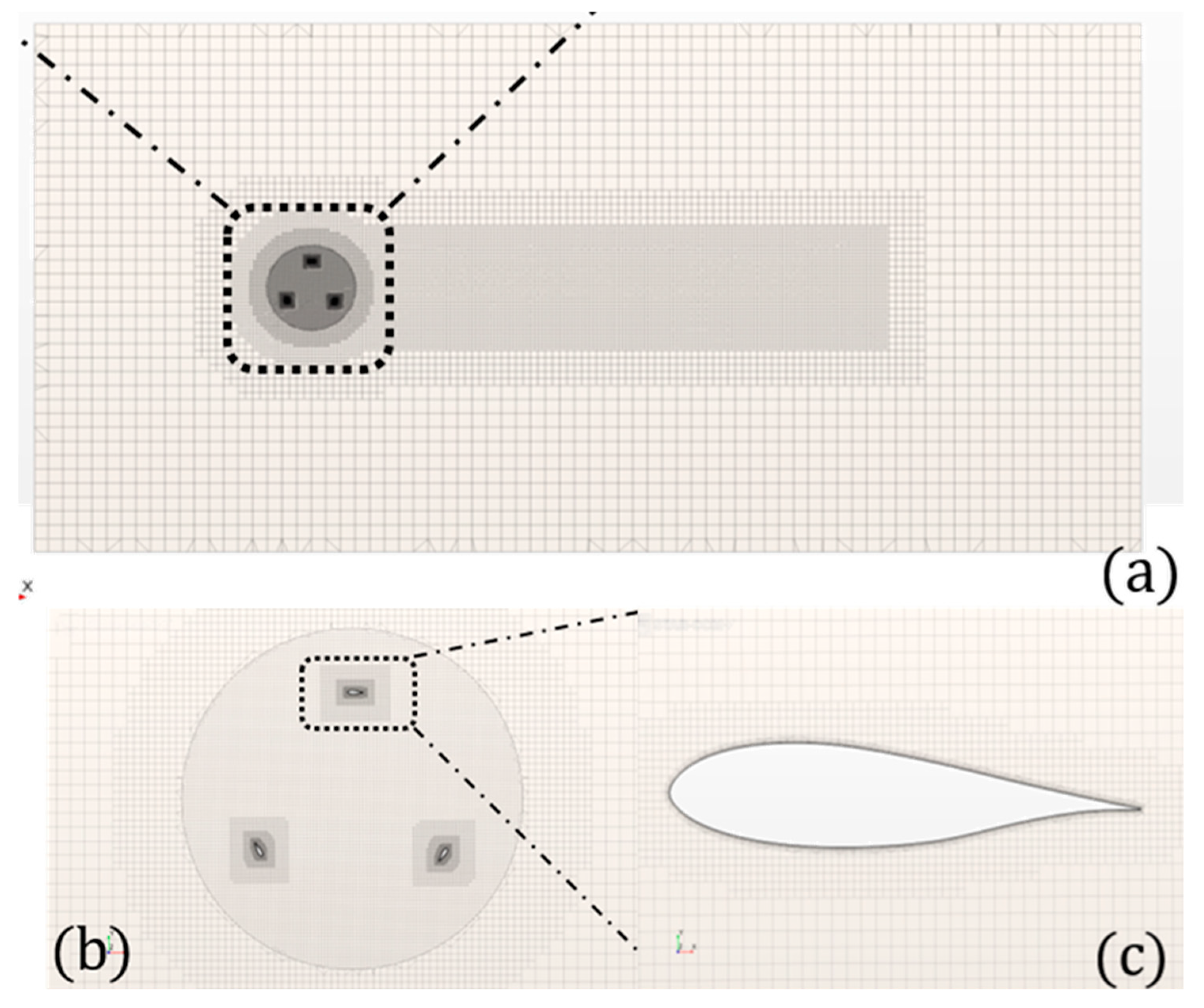

Figure 5.

The cross-section of the mesh topology of the VAWT model: (a) whole domain; (b) rotating domain; (c) DU-06-W-200 airfoil.

Figure 5.

The cross-section of the mesh topology of the VAWT model: (a) whole domain; (b) rotating domain; (c) DU-06-W-200 airfoil.

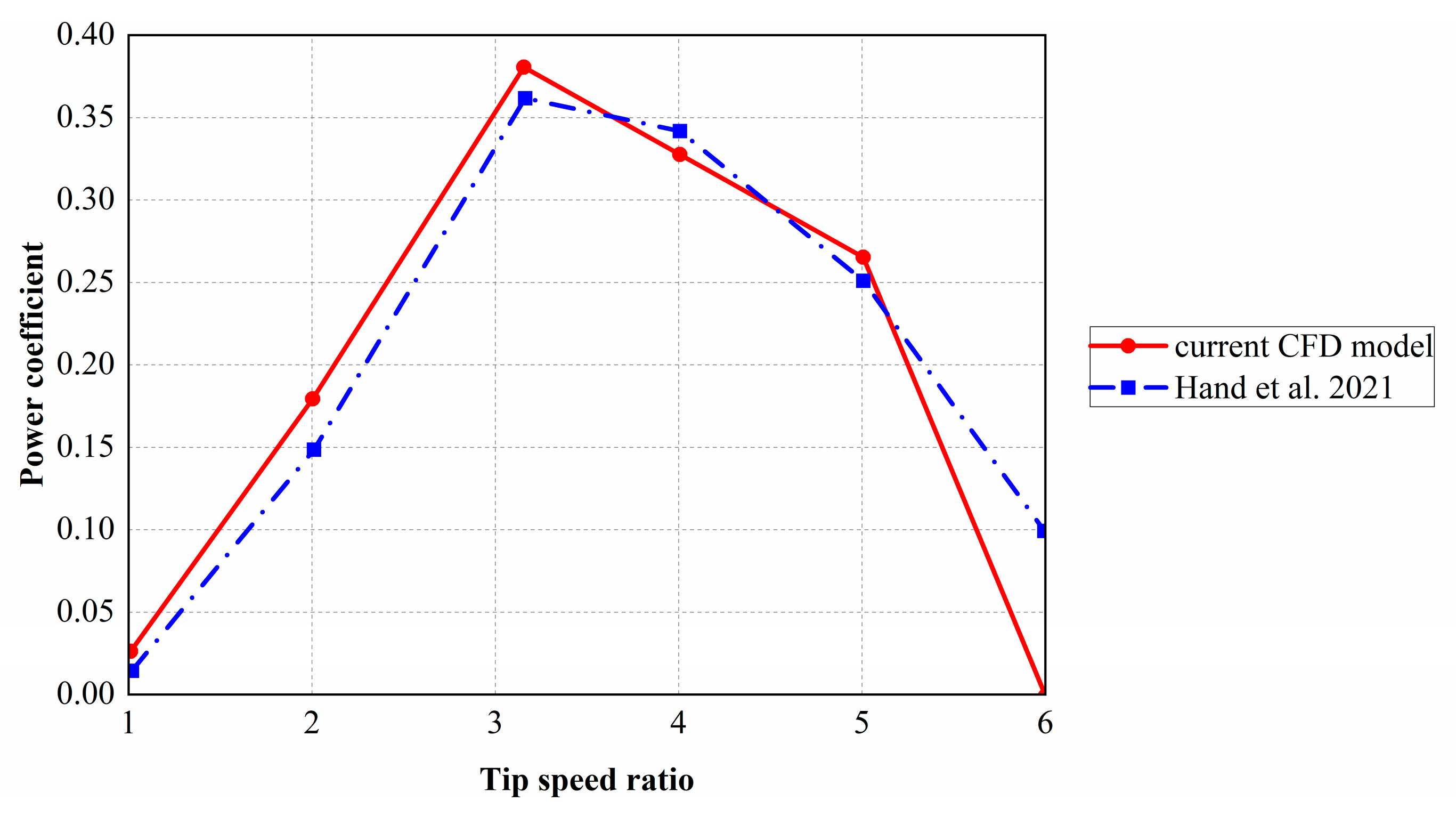

Figure 6.

Comparison of wind energy utilization coefficient curves of the VAWT. Data from Hand et al. [

6].

Figure 6.

Comparison of wind energy utilization coefficient curves of the VAWT. Data from Hand et al. [

6].

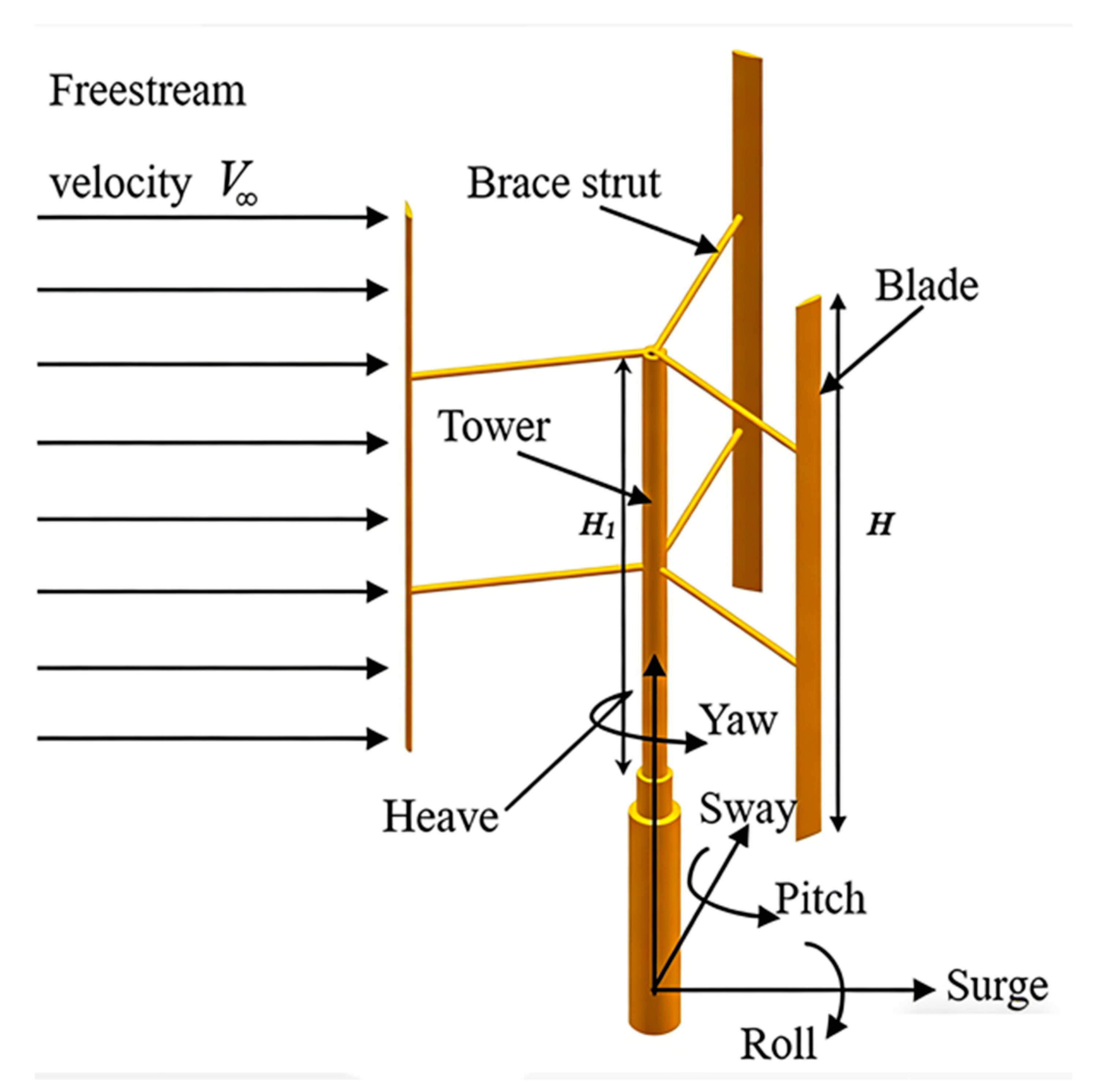

Figure 7.

Degrees of freedom (DOF) for a floating VAWT platform.

Figure 7.

Degrees of freedom (DOF) for a floating VAWT platform.

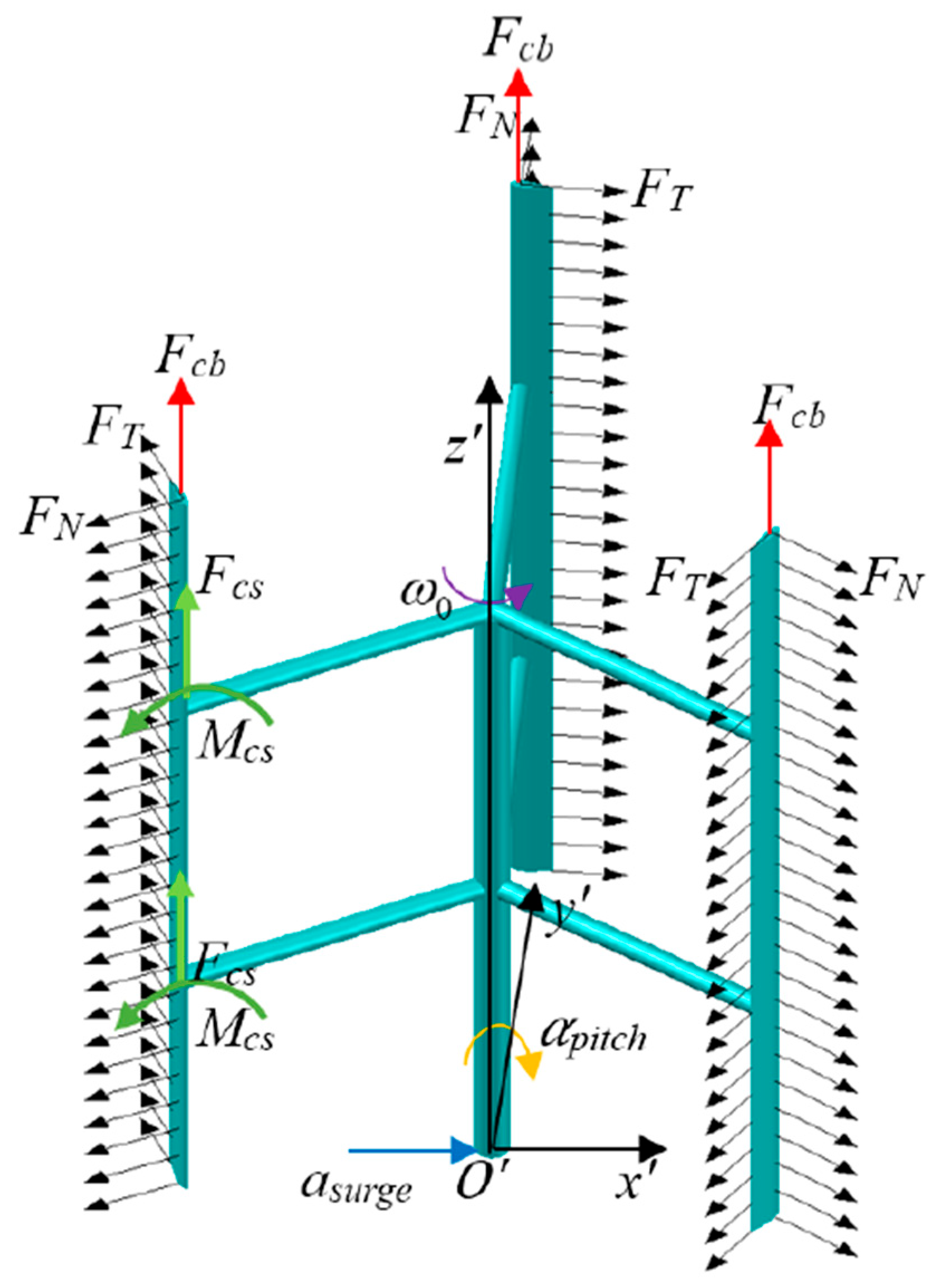

Figure 8.

Diagram of floating VAWT under loads.

Figure 8.

Diagram of floating VAWT under loads.

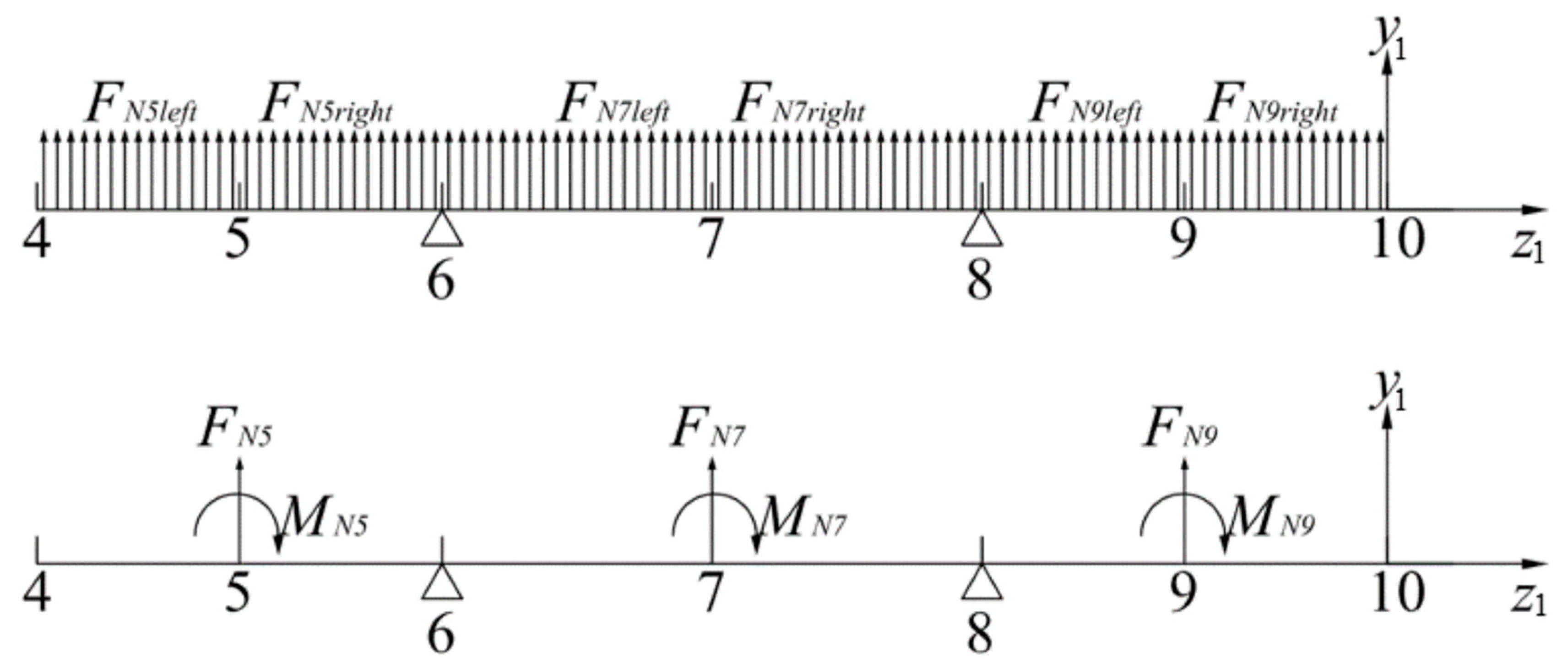

Figure 9.

Diagram of the original normal force (upper) and equivalent blade normal force (lower) for VAWT blade #1.

Figure 9.

Diagram of the original normal force (upper) and equivalent blade normal force (lower) for VAWT blade #1.

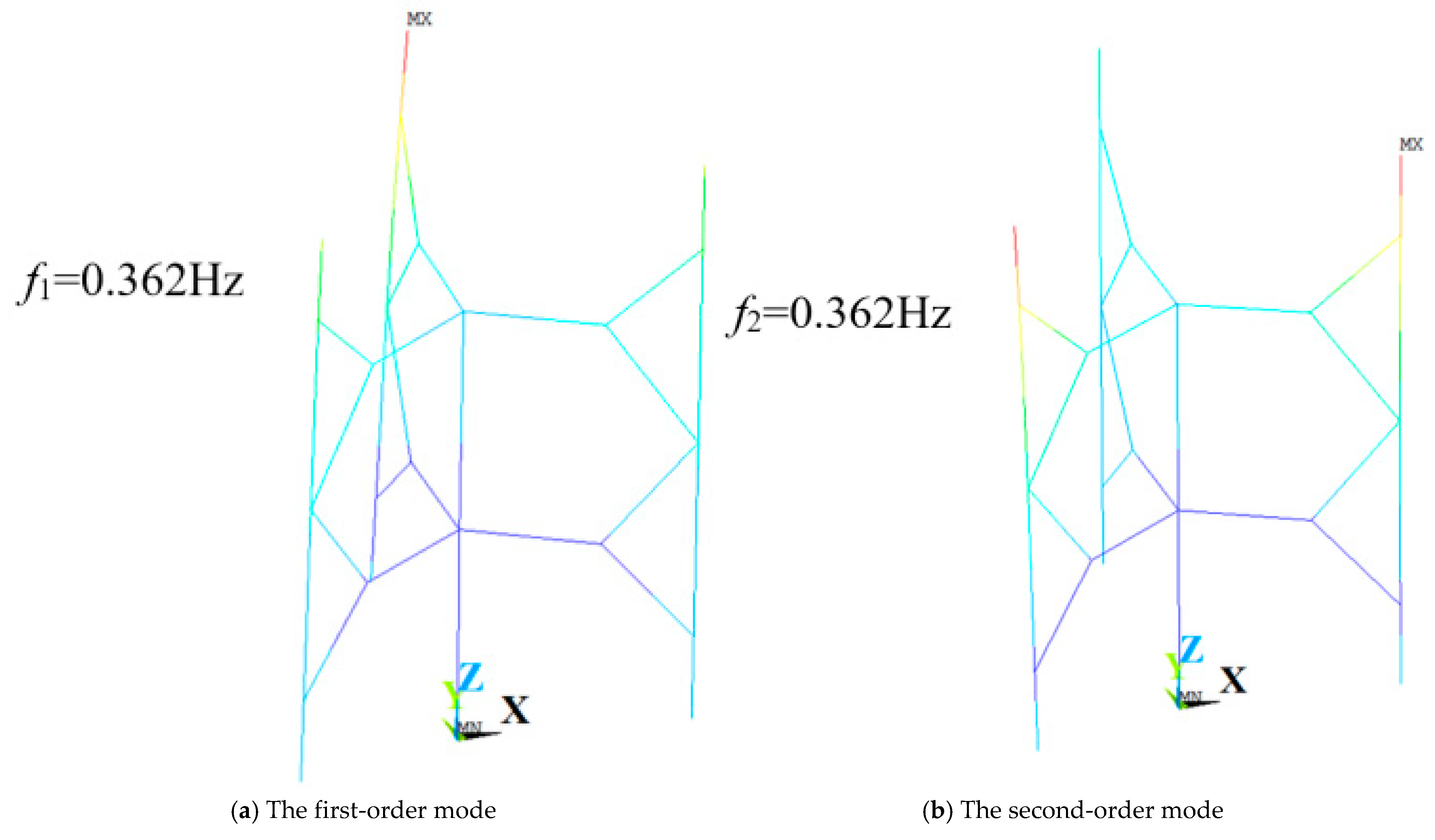

Figure 10.

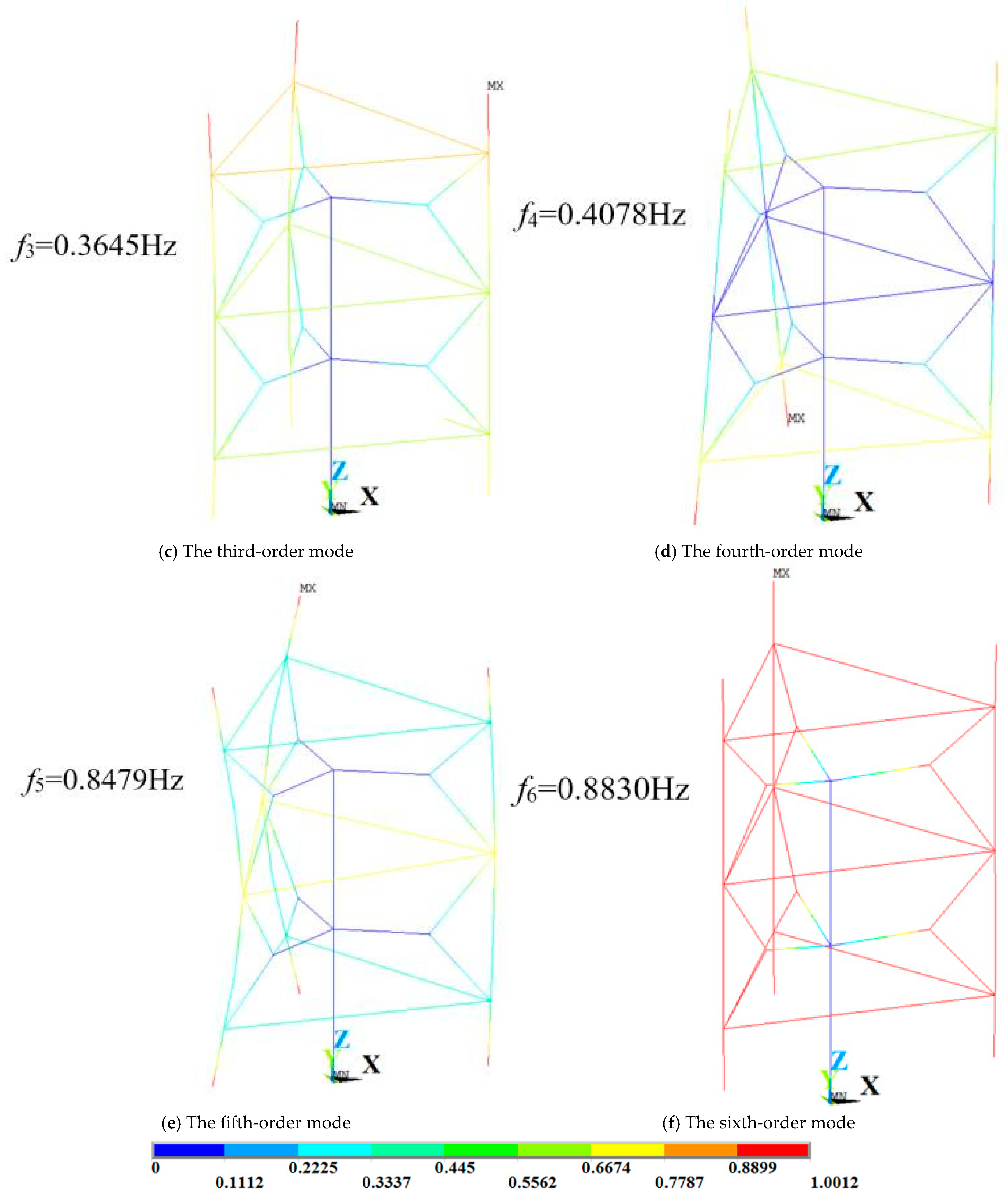

Vibration mode diagram of Model 1.

Figure 10.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 1.

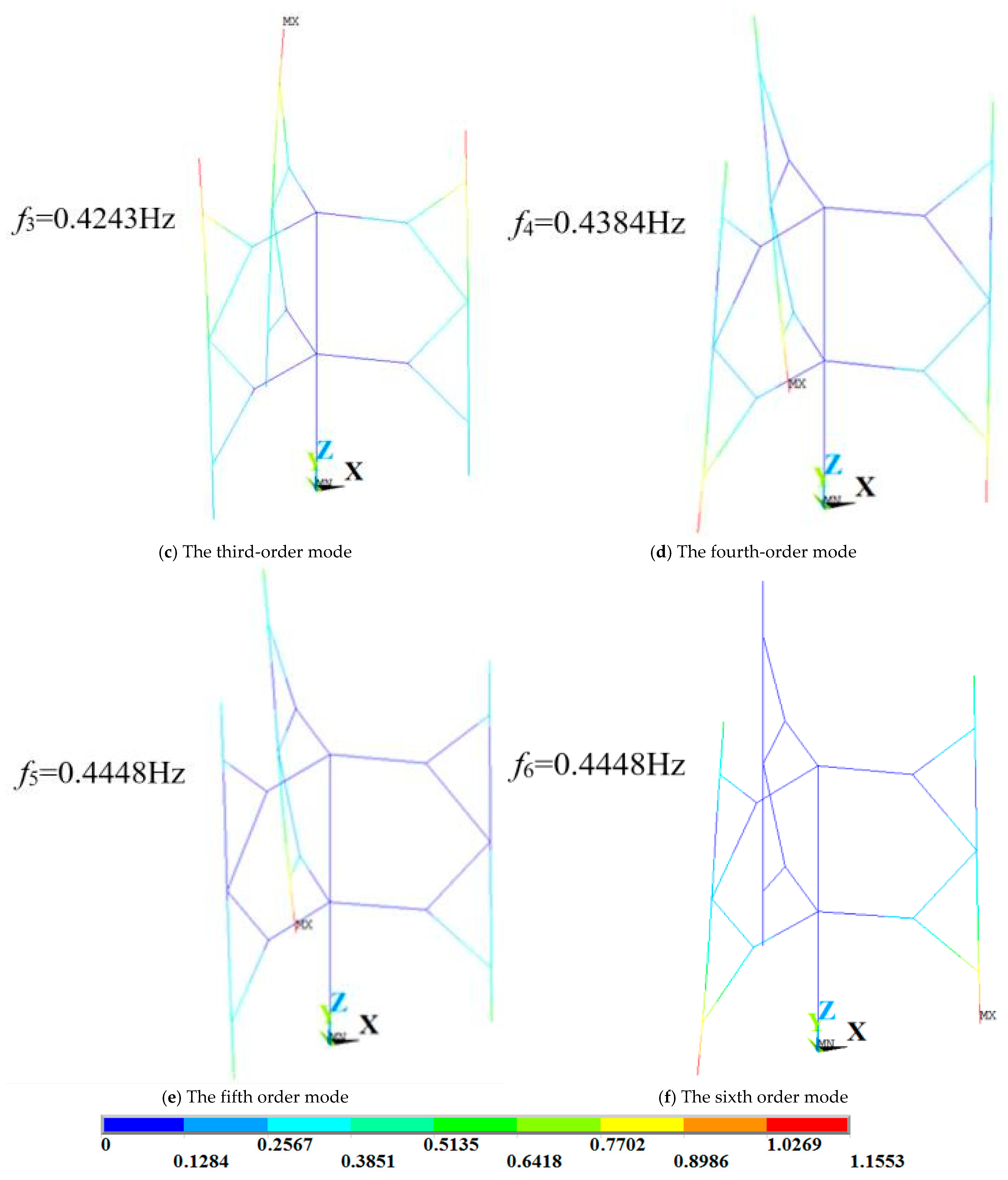

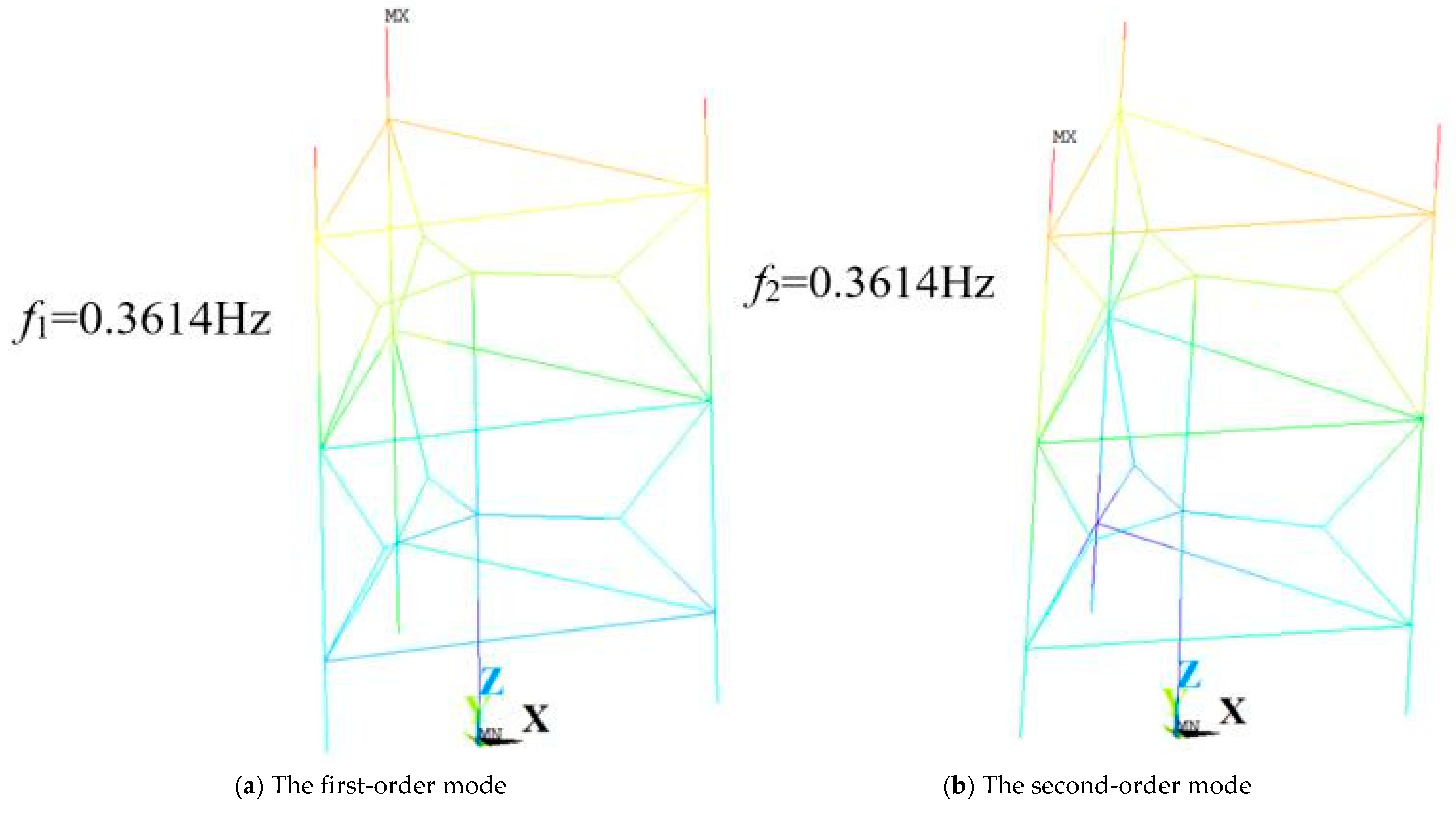

Figure 11.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 2.

Figure 11.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 2.

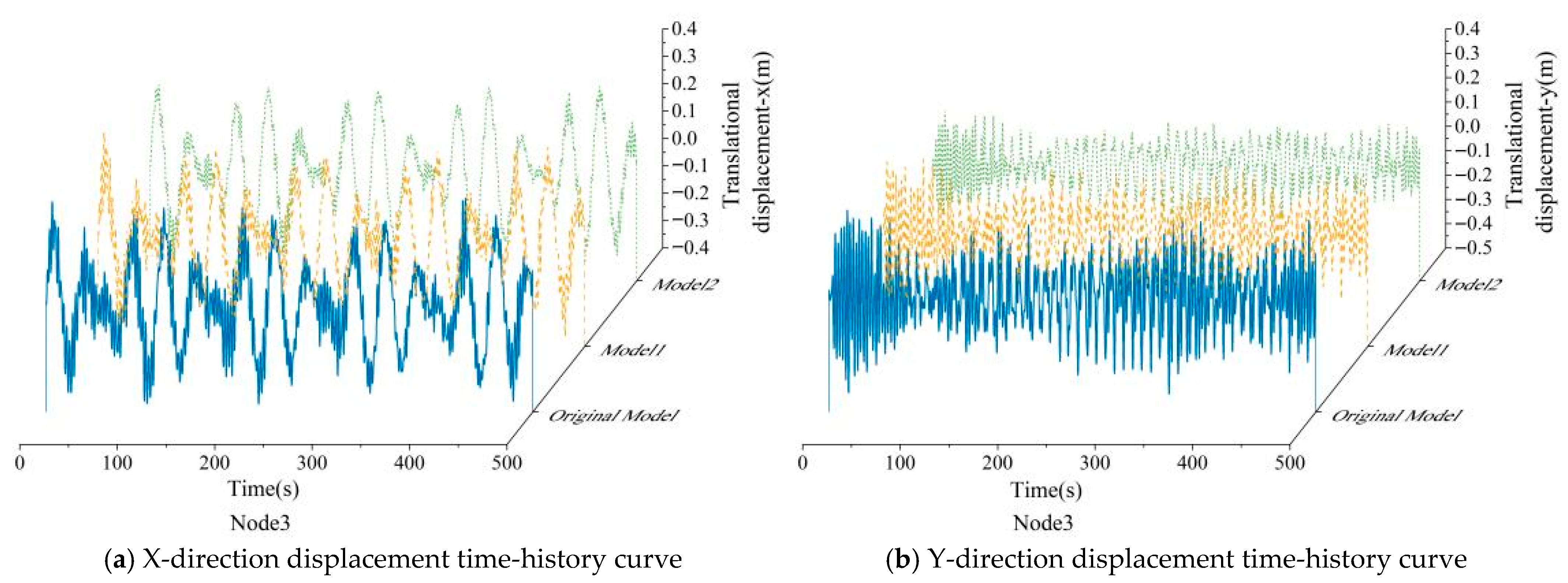

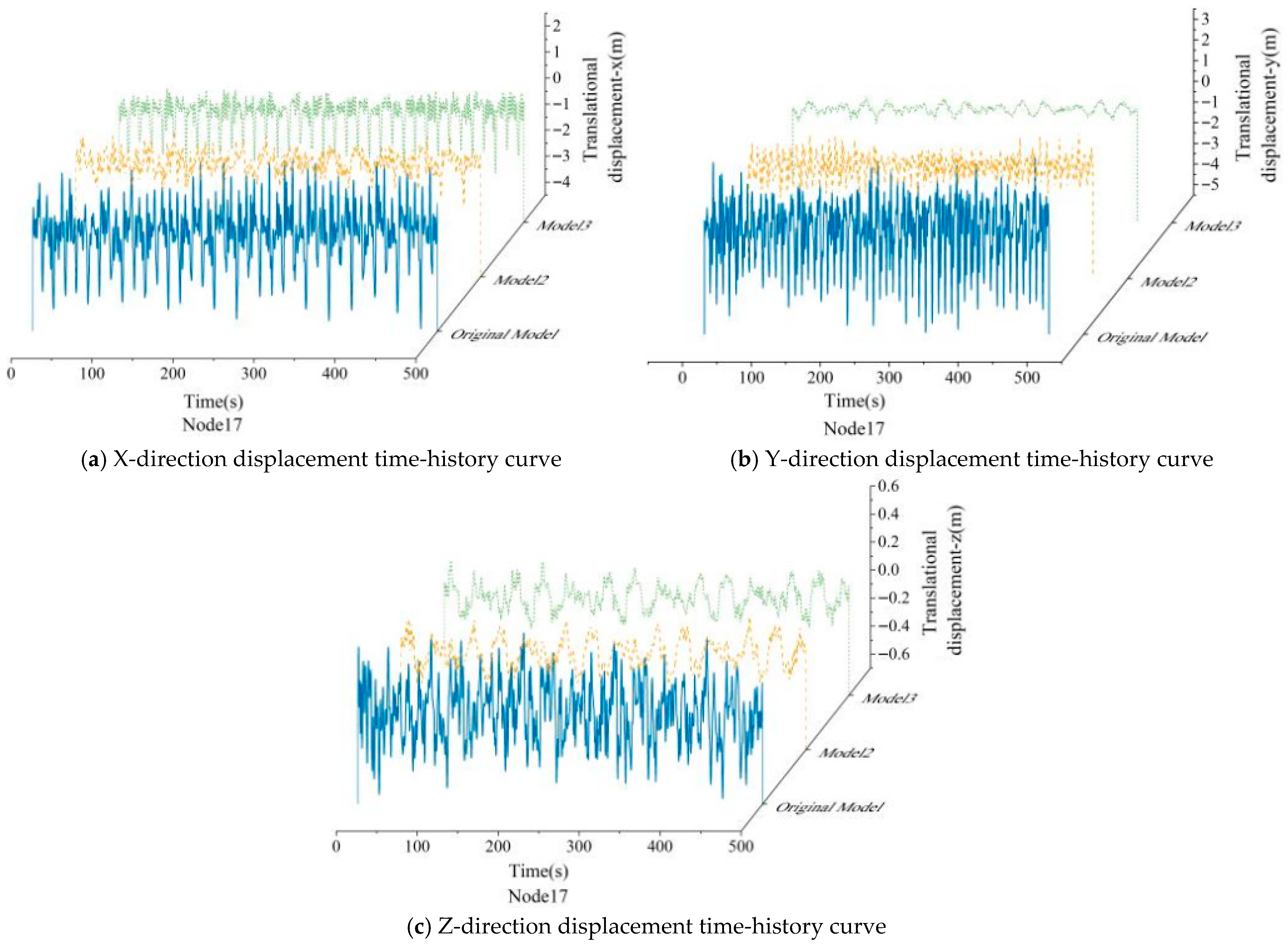

Figure 12.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top for the original model, Model 1, and Model 2.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top for the original model, Model 1, and Model 2.

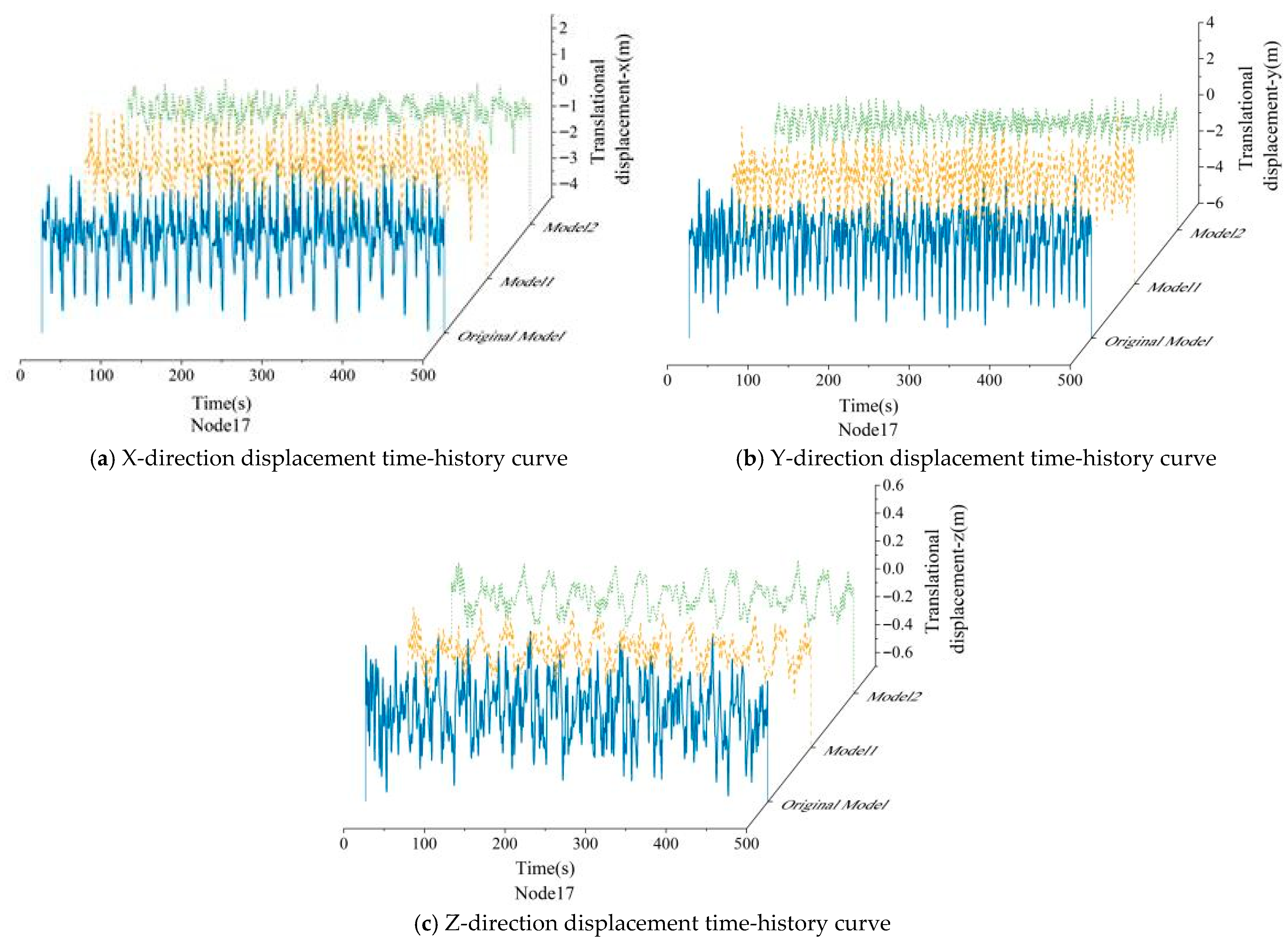

Figure 13.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade top for the original model, Model 1, and Model 2.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade top for the original model, Model 1, and Model 2.

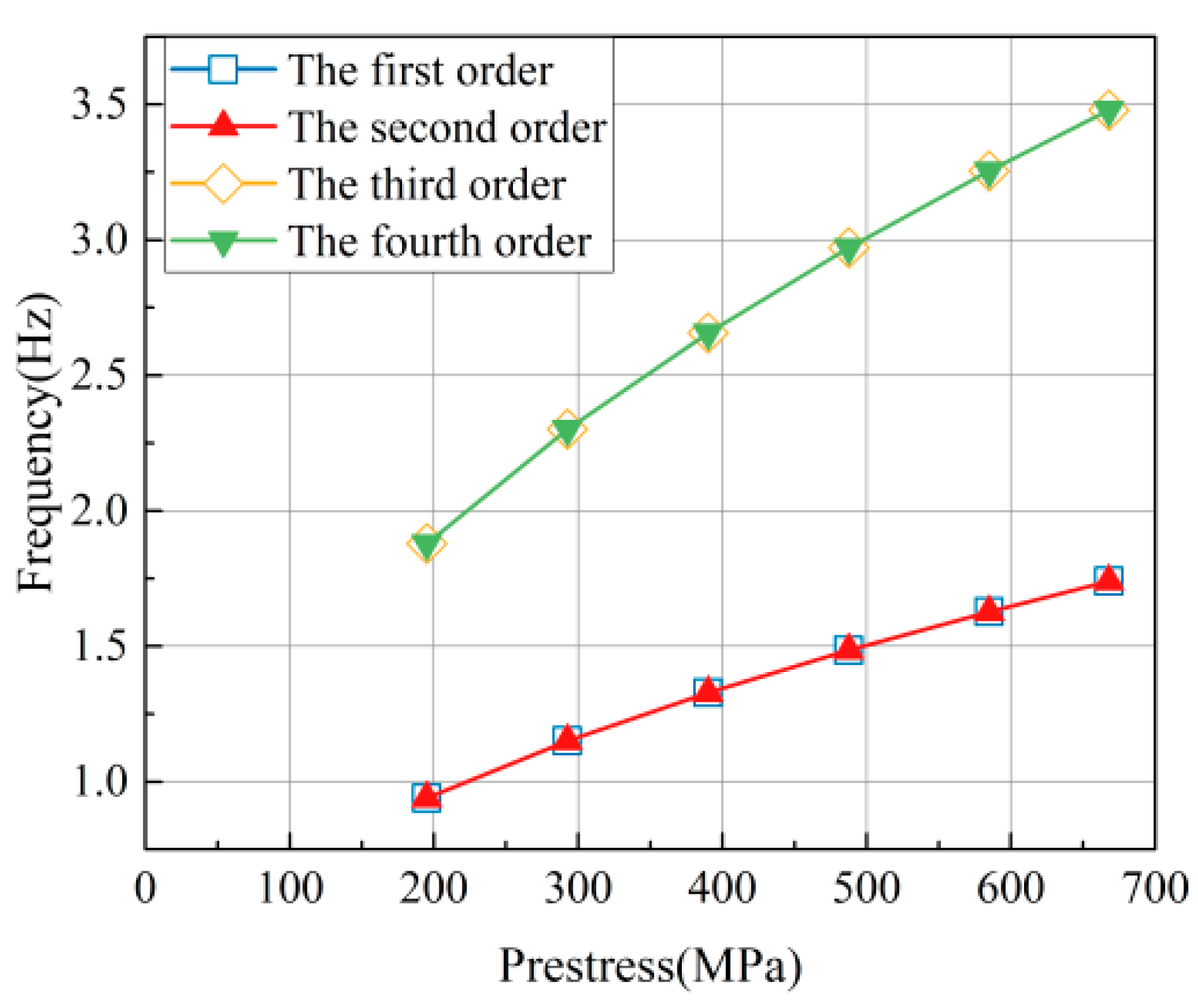

Figure 14.

Curves of cable natural vibration frequency with different prestress.

Figure 14.

Curves of cable natural vibration frequency with different prestress.

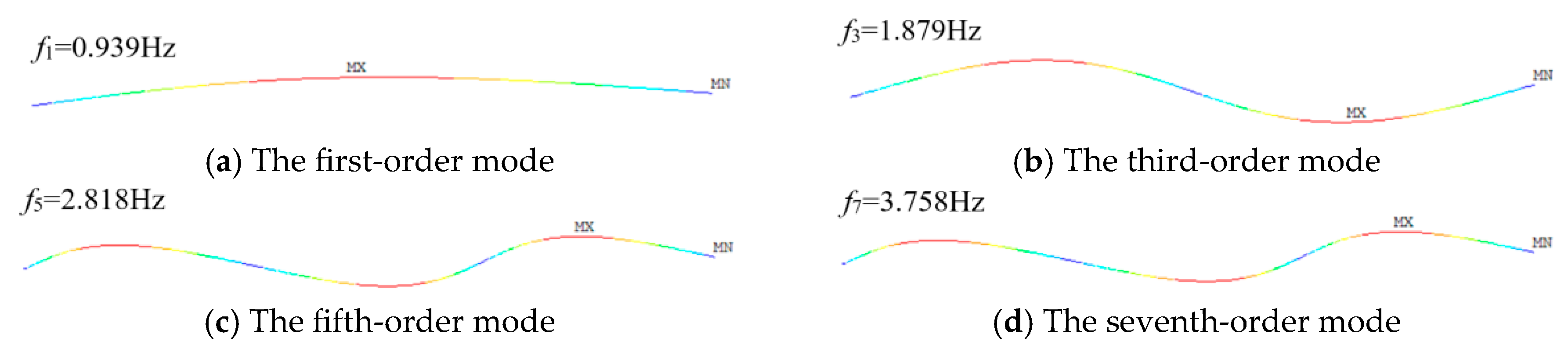

Figure 15.

Vibration mode diagram of the cable.

Figure 15.

Vibration mode diagram of the cable.

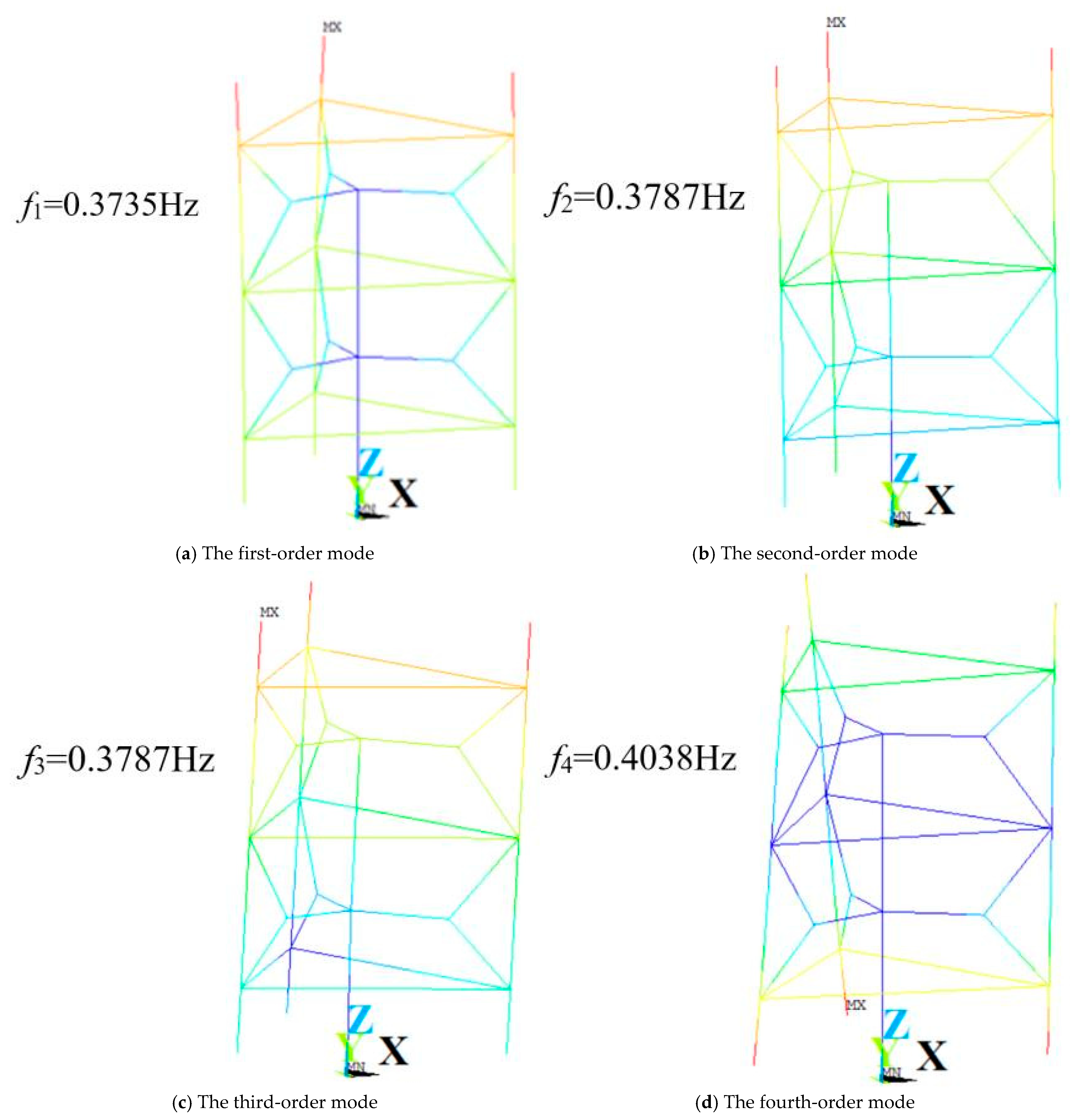

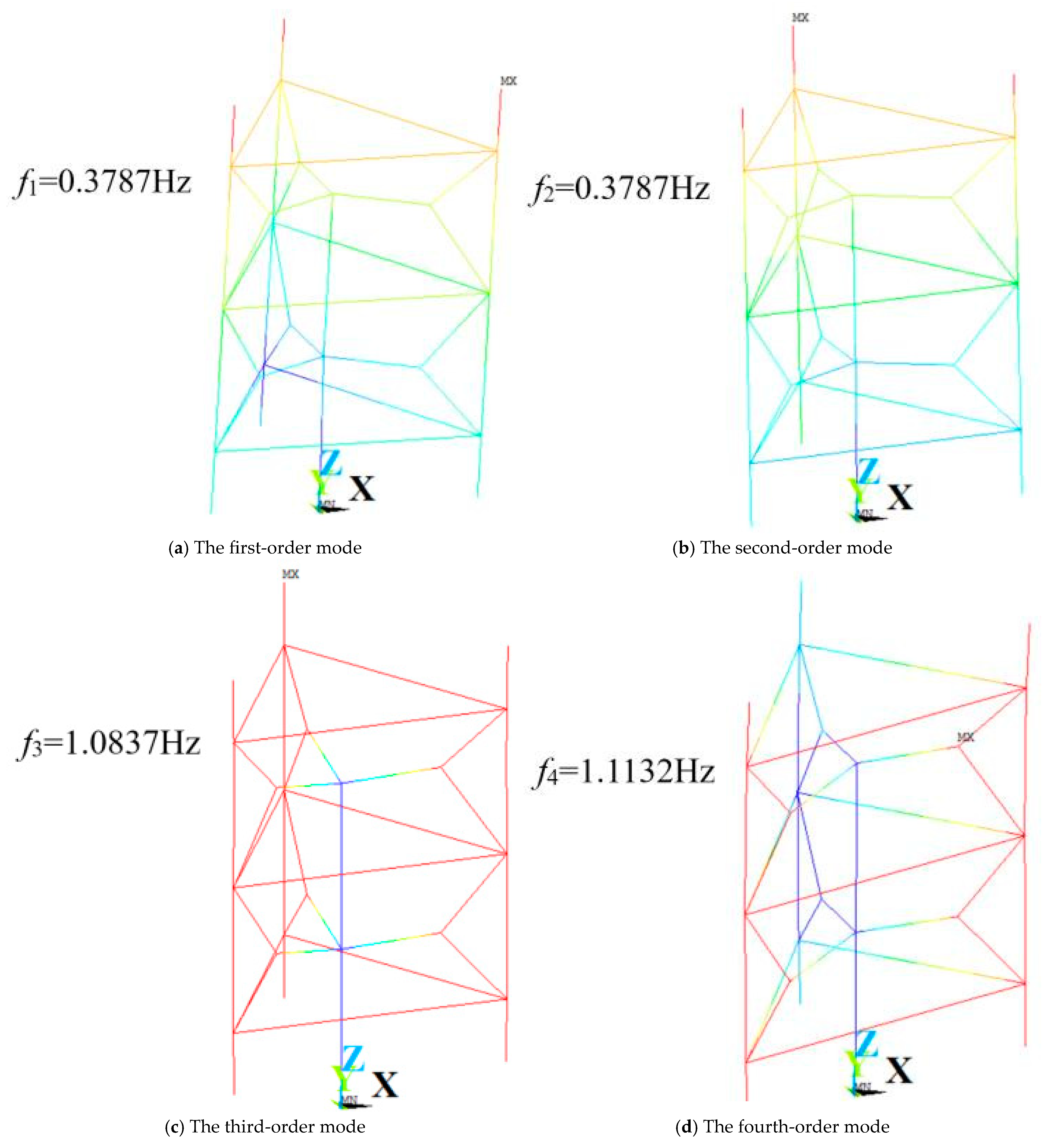

Figure 16.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 3.

Figure 16.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 3.

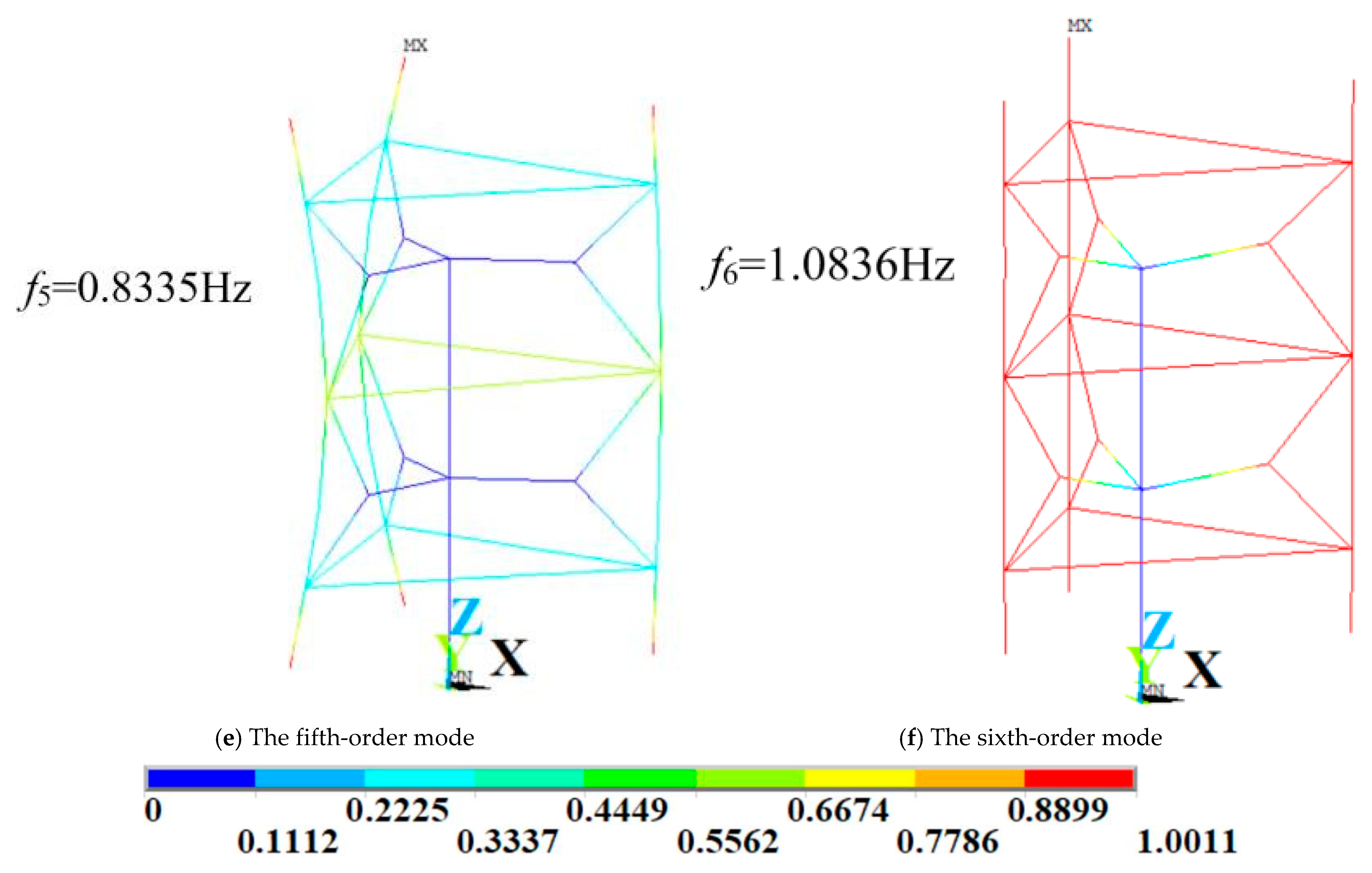

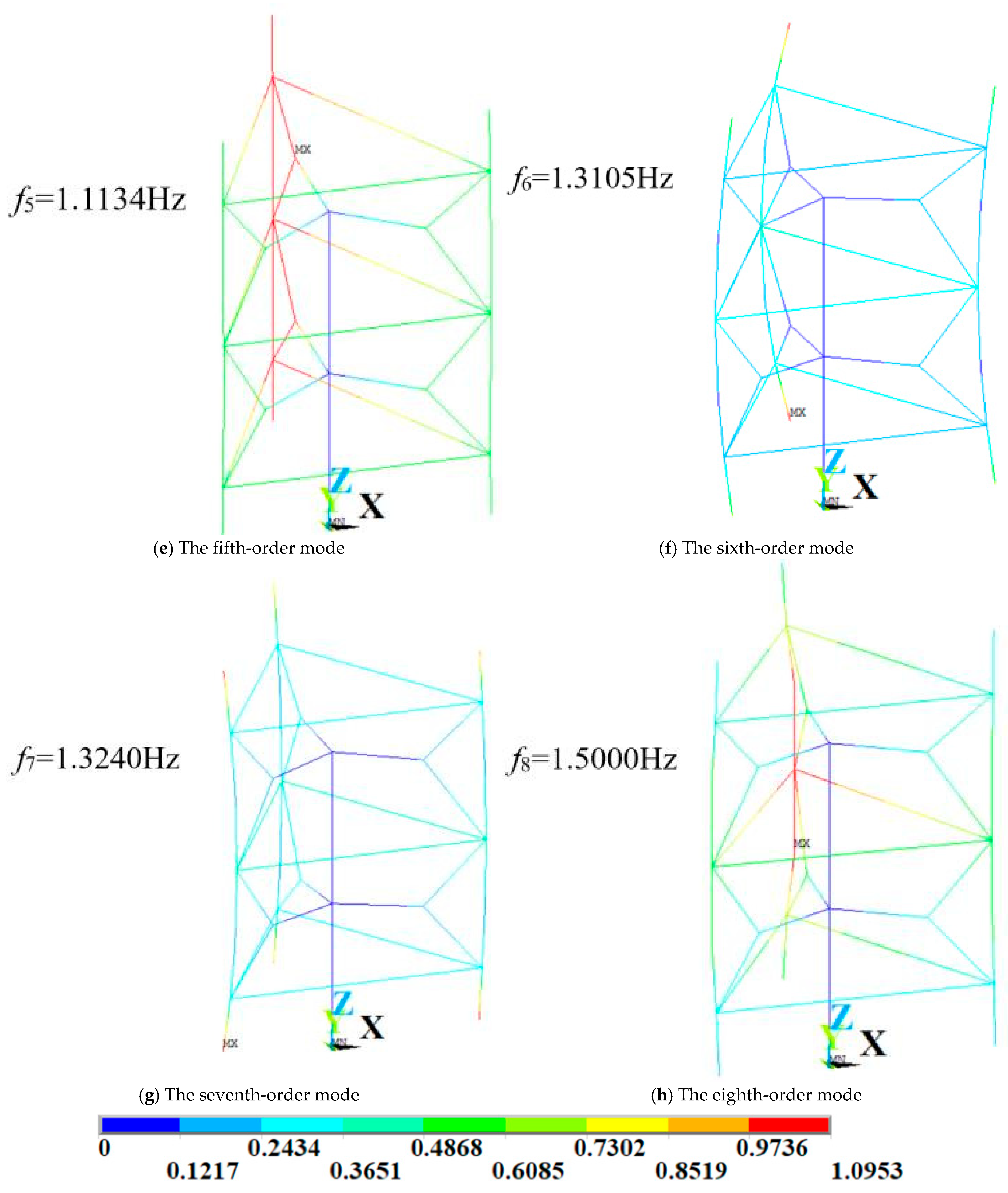

Figure 17.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top for the original model, Model 2, and Model 3.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top for the original model, Model 2, and Model 3.

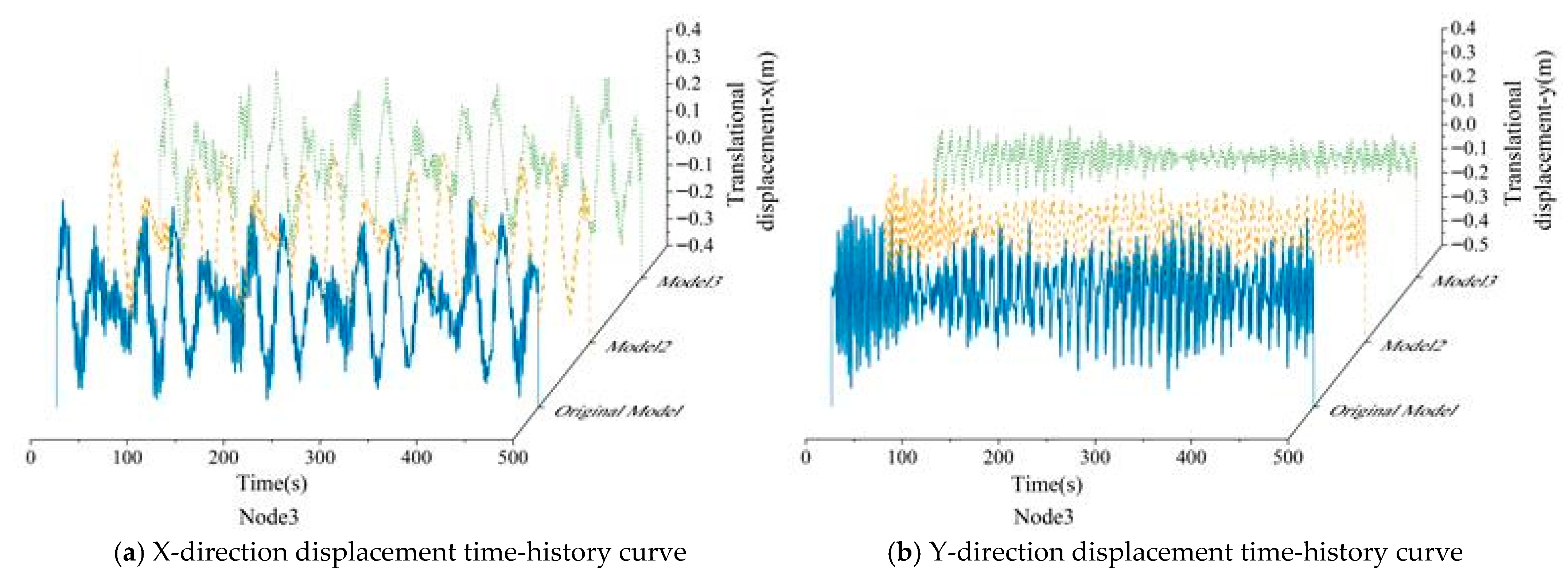

Figure 18.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade tip of the original model, Model 2, and Model 3.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade tip of the original model, Model 2, and Model 3.

Figure 19.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 4.

Figure 19.

Vibration mode diagram of Model 4.

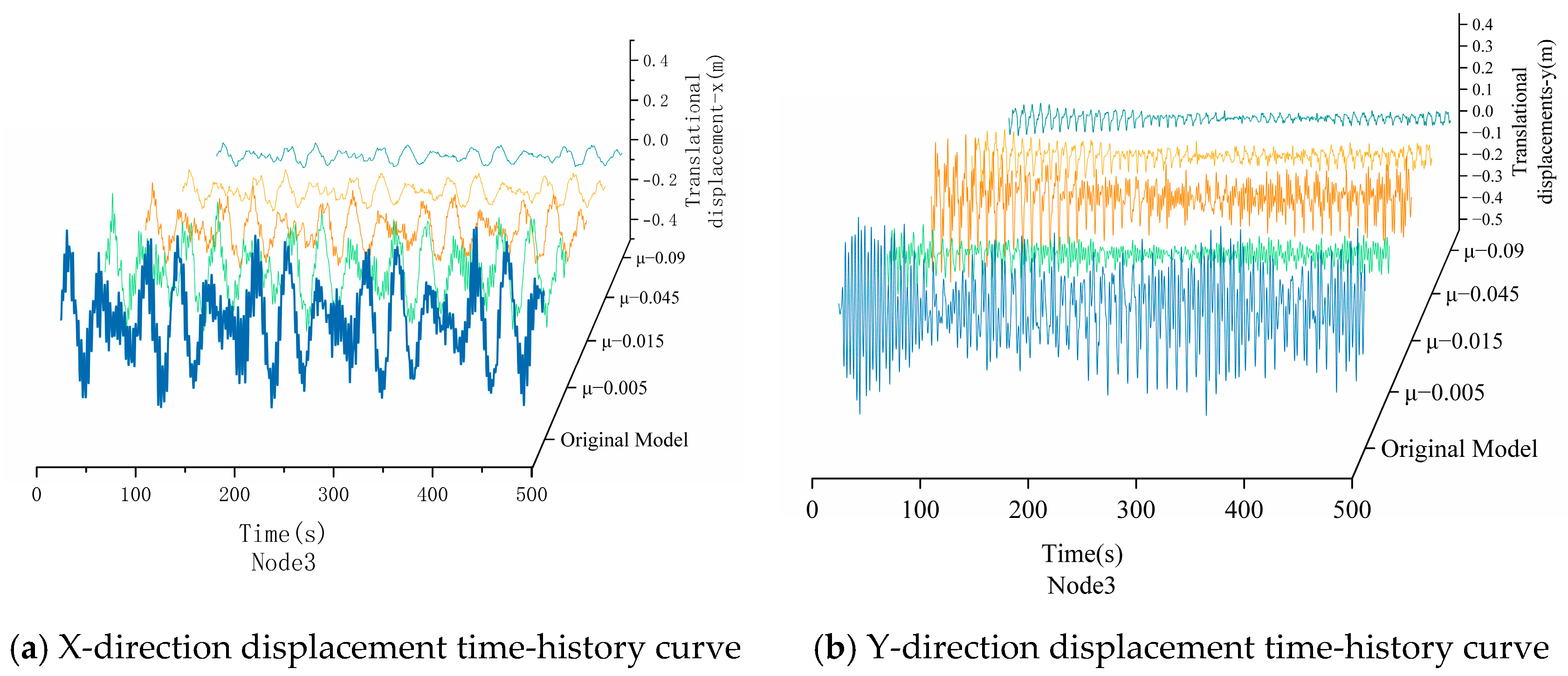

Figure 20.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top between Model 4 under different mass ratios and the original model.

Figure 20.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT tower top between Model 4 under different mass ratios and the original model.

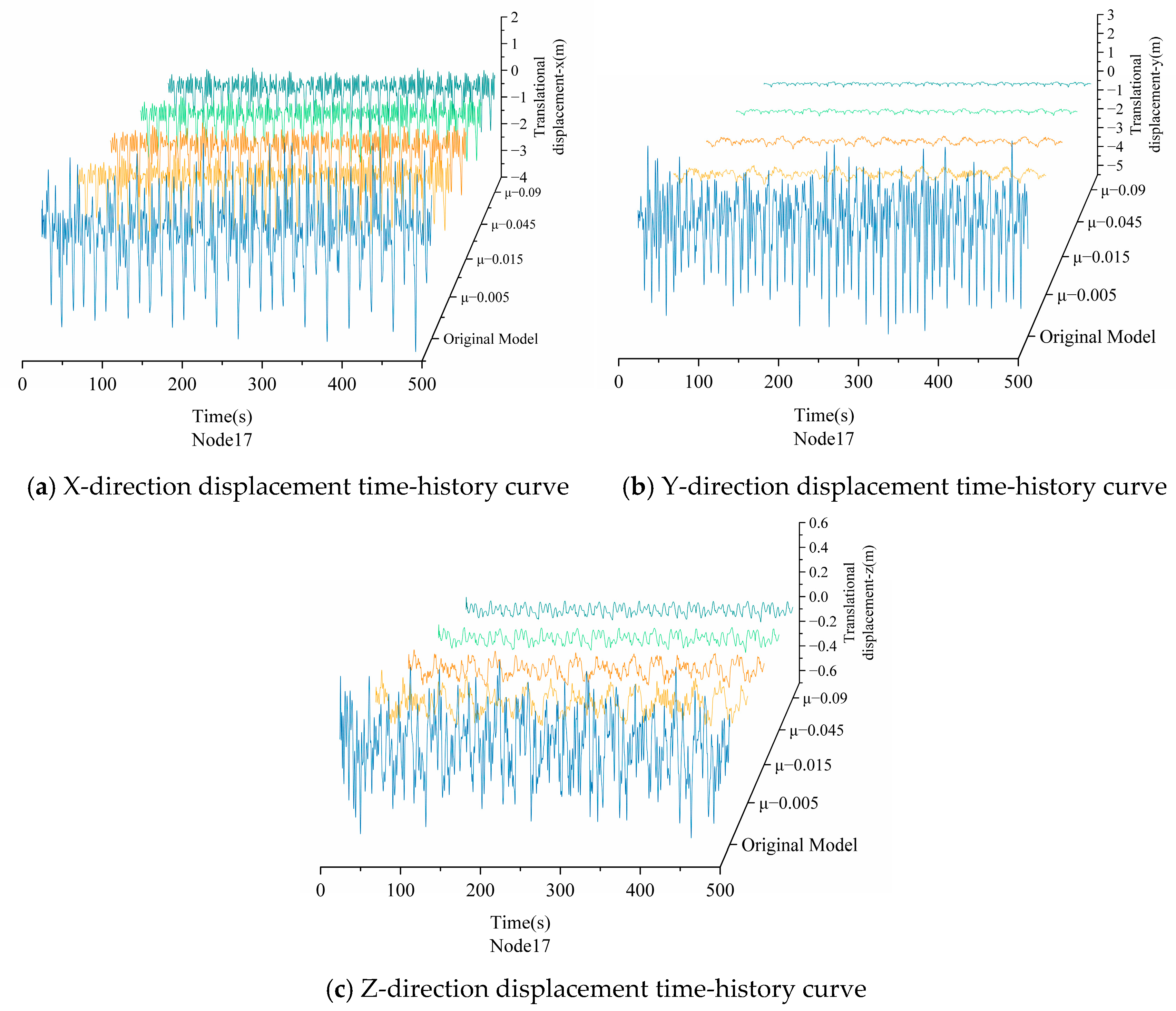

Figure 21.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade top between Model 4 under different mass ratios and the original model.

Figure 21.

Comparison of the displacement time-history curves of the VAWT blade top between Model 4 under different mass ratios and the original model.

Table 1.

Geometrical and operating settings of the original 5 MW VAWT model.

Table 1.

Geometrical and operating settings of the original 5 MW VAWT model.

| Geometrical and operating settings for original 5 MW VAWT model |

| Specific output power | 5 MW | ) | 13 m/s |

| Rotor diameter (D) | 96.872 m | Blade height (H) | 127.144 m |

| Blade number (N) | 3 | Strut-blade connection position | 0.3 H |

| ) | | Blade chord length (c) | 6.357 m |

| Airfoil type | DU-06-W-200 | Struts number for each blade | 2 |

| ) | 2.167–6.810 rpm | Cut-in wind speed | 3.5 m/s |

| Torque range | m | Cut-out wind speed | 25 m/s |

| ) | 100 m | ) | 3.260–24.875 |

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of VAWT materials.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of VAWT materials.

| Components | Material Type | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|

| Brace struts, blades | Carbon fiber epoxy resin | 1.62 × 103 | 120 | 0.31 |

| Tower | 40Cr alloy steel | 7.85 × 103 | 211 | 0.3 |

Table 3.

Mechanical Parameters of the Cable.

Table 3.

Mechanical Parameters of the Cable.

| Section Area (mm2) | Density

(kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Linear Expansion Coefficient | Temperature Difference | Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|

| 7854 | 7850 | 195 | 1.15 × 10−5 | 10° | 1670 |

Table 4.

Optimal parameters of TMD under different mass ratios.

Table 4.

Optimal parameters of TMD under different mass ratios.

| Optimal parameters of TMD under different mass ratios |

| Mass Ratio μ | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.045 | 0.09 |

| TMD mass (kg) | 46,072 | 138,216 | 414,648 | 829,296 |

| 0.995 | 0.985 | 0.957 | 0.917 |

| 0.043 | 0.074 | 0.127 | 0.176 |

| Structural circular frequency (rad/s) | 2.347 | 2.347 | 2.347 | 2.347 |

| TMD circular frequency (rad/s) | 2.335 | 2.312 | 2.246 | 2.153 |

| TMD rigidity (N/m) | 251,202 | 738,829 | 2,091,051 | 3,843,919 |

| TMD damping (N∙s/m) | 9293 | 47,578 | 236,655 | 628,341 |

Table 5.

First 10 natural frequencies of Model 1.

Table 5.

First 10 natural frequencies of Model 1.

| First 10 natural frequencies of Model 1 and Model 2 |

| Model 1 | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.424 | 0.438 | 0.445 |

| Order | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 0.445 | 0.495 | 0.495 | 0.848 | 0.851 |

| Model 2 | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 0.361 | 0.361 | 0.365 | 0.408 | 0.848 |

| Order | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Frequency (Hz) | 0.883 | 1.027 | 1.027 | 1.179 | 1.179 |

Table 6.

Peak displacement comparison of both the top of the VAWT tower and the top of the VAWT blade.

Table 6.

Peak displacement comparison of both the top of the VAWT tower and the top of the VAWT blade.

| | Top of Spindle (m) | Top of Blade (m) |

|---|

| Original Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Original Model | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|

| Ux | Max | 0.381 | 0.384 | 0.315 | 2.035 | 2.466 | 1.088 |

| Min | −0.371 | −0.363 | −0.346 | −4.407 | −3.078 | −1.765 |

| Uy | Max | 0.328 | 0.271 | 0.197 | 3.029 | 3.631 | 1.582 |

| Min | −0.427 | −0.339 | −0.272 | −5.416 | −4.137 | −1.593 |

| Uz | Max | | | | 0.524 | 0.311 | 0.253 |

| Min | | | | −0.658 | 0.359 | −0.234 |

Table 7.

Comparison of damping efficiencies between Model 1 and Model 2.

Table 7.

Comparison of damping efficiencies between Model 1 and Model 2.

| | Top of Spindle (m) | Top of Blade (m) |

|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|

| Ux | Max | −0.81% | 17.19% | −21.17% | 46.56% |

| Min | 2.19% | 6.88% | 30.15% | 59.94% |

| Uy | Max | 17.61% | 39.98% | −19.88% | 47.78% |

| Min | 20.56% | 36.19% | 23.61% | 70.58% |

| Uz | Max | | | 40.76% | 51.81% |

| Min | | | 45.42% | 64.47% |

Table 8.

Technical parameters of the cable.

Table 8.

Technical parameters of the cable.

| Category | Section Area (mm2) | Density

(kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Linear Expansion Coefficient | Difference in Temperature | Standard Value of Tensile Strength

(MPa) |

|---|

| Parameter | 7854 | 7850 | 195 | | 10° | 1670 |

Table 9.

Frequencies of cables with different cross-sectional areas.

Table 9.

Frequencies of cables with different cross-sectional areas.

| Section Area (mm2) | 1st Order (Hz) | 2nd Order (Hz) | 3rd Order (Hz) | 4th Order (Hz) | 5th Order (Hz) | 6th Order (Hz) | 7th Order (Hz) | 8th Order (Hz) | 9th Order (Hz) | 10th Order (Hz) |

|---|

| 3927 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 2.818 | 2.818 | 3.758 | 3.758 | 4.697 | 4.697 |

| 7854 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 2.818 | 2.818 | 3.758 | 3.758 | 4.697 | 4.697 |

| 11,781 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 2.818 | 2.818 | 3.758 | 3.758 | 4.697 | 4.697 |

| 15,708 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 2.818 | 2.818 | 3.758 | 3.758 | 4.697 | 4.697 |

Table 10.

Frequencies of cables with different initial stress.

Table 10.

Frequencies of cables with different initial stress.

| Prestress (MPa) | 1st Order (Hz) | 2nd Order (Hz) | 3rd Order (Hz) | 4th Order (Hz) | 5th Order (Hz) | 6th Order (Hz) | 7th Order (Hz) | 8th Order (Hz) | 9th Order (Hz) | 10th Order (Hz) |

|---|

| 195 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 1.879 | 1.879 | 2.818 | 2.818 | 3.758 | 3.758 | 4.697 | 4.697 |

| 292.5 | 1.151 | 1.151 | 2.301 | 2.301 | 3.452 | 3.452 | 4.602 | 4.602 | 5.753 | 5.753 |

| 390 | 1.328 | 1.328 | 2.657 | 2.657 | 3.985 | 3.985 | 5.314 | 5.314 | 6.643 | 6.643 |

| 487.5 | 1.485 | 1.485 | 2.971 | 2.971 | 4.456 | 4.456 | 5.941 | 5.941 | 7.427 | 7.427 |

| 585 | 1.627 | 1.627 | 3.254 | 3.254 | 4.881 | 4.881 | 6.508 | 6.508 | 8.136 | 8.136 |

| 668 | 1.740 | 1.740 | 3.479 | 3.479 | 5.219 | 5.219 | 6.959 | 6.959 | 8.699 | 8.699 |

Table 11.

The first 10 natural frequencies of Model 3.

Table 11.

The first 10 natural frequencies of Model 3.

| The first 10 natural frequencies of Model 3 |

| Order | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Frequency (Hz) | Frequency (Hz) | 0.373 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 0.404 | 0.833 |

| Order | Order | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Frequency (Hz) | Frequency (Hz) | 1.084 | 1.113 | 1.113 | 1.317 | 1.317 |

Table 12.

Damping efficiencies of Model 3 at the top of the main shaft and the top of the blade.

Table 12.

Damping efficiencies of Model 3 at the top of the main shaft and the top of the blade.

| | Top of Spindle (m) | Top of Blade (m) |

|---|

| Original Model | Model 3 | Damping Efficiencies | Original Model | Model 3 | Damping Efficiencies |

|---|

| Ux | Max | 0.381 | 0.382 | −0.32% | 2.035 | 0.626 | 69.23% |

| Min | −0.371 | −0.376 | −1.44% | −4.407 | −2.590 | 41.23% |

| Uy | Max | 0.328 | 0.130 | 60.29% | 3.029 | 0.534 | 82.38% |

| Min | −0.427 | −0.171 | 59.84% | −5.416 | −0.690 | 87.26% |

| Uz | Max | | | | 0.524 | 0.262 | 50.11% |

| Min | | | | −0.658 | −0.220 | 66.61% |

Table 13.

Frequencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

Table 13.

Frequencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

| Mass Ratio | 1st Order (Hz) | 2nd Order (Hz) | 3rd Order (Hz) | 4th Order (Hz) | 5th Order (Hz) | 6th Order (Hz) | 7th Order (Hz) | 8th Order (Hz) | 9th Order (Hz) | 10th Order (Hz) |

|---|

| 0.005 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 0.718 | 0.749 | 1.015 | 1.084 | 1.113 | 1.113 | 1.318 | 1.319 |

| 0.015 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 1.066 | 1.084 | 1.102 | 1.113 | 1.114 | 1.244 | 1.320 | 1.332 |

| 0.045 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 1.084 | 1.113 | 1.113 | 1.311 | 1.324 | 1.500 | 1.529 | 1.609 |

| 0.09 | 0.379 | 0.379 | 1.084 | 1.113 | 1.114 | 1.312 | 1.328 | 1.695 | 1.712 | 1.797 |

Table 14.

Displacements of the top of the tower and damping efficiencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

Table 14.

Displacements of the top of the tower and damping efficiencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

| | | Displacement (m) | Damping Efficiencies (%) |

|---|

| Original Model | | | | | | | | |

|---|

| Ux | Max | 0.381 | 0.345 | 0.217 | 0.107 | 0.066 | 9.37 | 43.01 | 71.88 | 82.65 |

| Min | −0.371 | −0.255 | −0.172 | −0.092 | −0.057 | 31.36 | 53.53 | 75.30 | 84.68 |

| Uy | Max | 0.328 | 0.118 | 0.065 | 0.029 | 0.017 | 64.05 | 80.28 | 91.32 | 94.87 |

| Min | −0.427 | −0.163 | −0.090 | −0.036 | −0.020 | 61.84 | 78.98 | 91.58 | 95.21 |

Table 15.

Displacements of the top of the blade and damping efficiencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

Table 15.

Displacements of the top of the blade and damping efficiencies of Model 4 under different mass ratios.

| | | Displacement (m) | Damping Efficiencies (%) |

|---|

| Original Model | | | | | | | | |

|---|

| Ux | Max | 2.035 | 0.583 | 0.600 | 0.585 | 0.578 | 71.36 | 70.51 | 71.26 | 71.61 |

| Min | −4.407 | −2.464 | −2.434 | −2.339 | −2.300 | 44.10 | 44.76 | 46.93 | 47.80 |

| Uy | Max | 3.029 | 0.408 | 0.273 | 0.158 | 0.116 | 86.52 | 90.99 | 94.80 | 96.18 |

| Min | −5.416 | −0.472 | −0.368 | −0.230 | −0.171 | 91.28 | 93.20 | 95.75 | 96.83 |

| Uz | Max | 0.524 | 0.228 | 0.142 | 0.105 | 0.102 | 56.51 | 72.94 | 80.01 | 80.51 |

| Min | −0.658 | −0.174 | −0.137 | −0.110 | −0.098 | 73.64 | 79.18 | 83.23 | 85.19 |

Table 16.

Comparison of damping efficiency of four models.

Table 16.

Comparison of damping efficiency of four models.

| | Top of Blade (m) | Top of Blade (m) |

|---|

| Free degree | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Ux | 2.19% | 17.19% | −0.32% | 84.68% | 30.15% | 59.94% | 69.23% | 71.61% |

| Uy | 20.56% | 39.98% | 60.29% | 95.21% | 23.61% | 70.58% | 87.26% | 96.83% |

| Uz | | | | | 45.42% | 64.47% | 66.61% | 85.19% |