Abstract

Integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage (HWSS) bases are pivotal for advancing new power systems under the low carbon goals. However, the independent decision-making of diverse generation investors, coupled with limited transmission capacity, often leads to a dilemma in which individually rational decisions lead to collectively suboptimal outcomes, undermining overall benefits. To address this challenge, this study proposes a novel cooperative game-based method that seamlessly integrates grid congestion into capacity allocation and benefit distribution. First, a bi-level optimization model is developed, where a congestion penalty is explicitly embedded into the cooperative game’s characteristic function to quantify the maximum benefits under different coalition structures. Second, an improved Shapley value model is introduced, incorporating a comprehensive correction factor that synthesizes investment risk, congestion mitigation contribution, and capacity scale to overcome the fairness limitations of the classical method. Third, a case study of a high-renewable-energy base in Qinghai is conducted. The results demonstrate that the proposed cooperative model increases total system revenue by 20.1%, while dramatically reducing congestion costs and wind/solar curtailment rates by 86.2% and 79.3%, respectively. Furthermore, the improved Shapley value ensures a fairer distribution, appropriately increasing the profit shares for hydropower (from 28.5% to 32.1%) and energy storage, thereby enhancing coalition stability. This research provides a theoretical foundation and practical decision-making tool for the collaborative planning of HWSS bases with multiple investors.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

The global energy landscape is undergoing a profound transformation driven by the imperative to achieve carbon peak and neutrality. Large-scale integration of renewable energy sources (RES), primarily wind and solar power, has become a central strategy worldwide [1,2]. Integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage (HWSS) bases, leveraging multi-energy complementarity and synergistic operation, have emerged as a critical pathway to mitigate the inherent intermittency and volatility of RES, thereby enhancing system efficiency, reliability, and renewable hosting capacity [3,4].

However, the rapid expansion of wind and solar power introduces significant operational challenges. Their anti-peak regulation characteristics and spatiotemporal mismatch with load demand exacerbate the difficulties in maintaining real-time power balance [5,6]. This issue is particularly acute in regions with limited transmission capacity, where grid congestion becomes a critical bottleneck, restricting clean energy delivery and leading to substantial curtailment [7,8]. When multiple, independent investors make self-interested capacity planning decisions under such physical constraints, the system can fall into a “prisoner’s dilemma,” where individual rationality leads to collective inefficiency [9,10]. Therefore, developing effective coordination mechanisms for capacity allocation and benefit distribution among diversified investors in HWSS, explicitly accounting for grid congestion, is a pressing yet underexplored research problem.

1.2. Literature Review

Traditional capacity planning often uses a single-entity approach. Stochastic programming handles energy system uncertainties [8], while robust optimization addresses data ambiguity under worst-case scenarios [9]. However, these methods are unsuitable for multi-investor contexts where individual strategic behavior dominates.

Cooperative game theory offers a principled framework for such multi-agent environments. It models coalition formation and provides a mechanism to secure collective benefits [10]. Its strength lies in aligning individual and collective goals to unlock synergy and ensure cooperation stability through fair profit-sharing [11]. There are many applications in this field: coordinating distributed resources in microgrids, optimizing integrated electricity-gas-heat systems, and managing virtual power plants [12].

Specific studies demonstrate clear benefits. Chen et al. [13] used cooperative games for capacity allocation in a wind-solar-hydrogen microgrid, proving economic gains from collaboration. Jiang et al. [14] applied it to electricity-gas systems, showing enhanced renewable integration and lower emissions.

The Shapley value is the standard for fair profit distribution, allocating payouts based on each member’s marginal contribution [15]. Despite its theoretical fairness, it has practical flaws. It fails to account for differences in investment risk [16], contributions to solving system-wide constraints like grid congestion, or the strategic value of capacity scale, which can destabilize cooperation [17].

This has led to various improvements. Tian et al. [18] modified the Shapley value within a master-slave game for fairer profit-sharing in solar communities. Li et al. [19] applied a similar logic for cost allocation of shared storage in multi-microgrids. Other methods like Nash bargaining have also been used for systems like wind-solar-hydrogen hubs [20].

Despite this progress, a critical gap remains. Most studies, including the cooperative game applications above, assume an ideal grid and ignore the real-world impact of grid congestion on both planning and profit-sharing [21,22]. While some research tackles congestion from a short-term operational view [23], it treats it as a dispatch problem, not a planning factor [24,25]. Research that explicitly integrates congestion costs into the cooperative game’s core model and refines the benefit allocation accordingly is still scarce [26,27].

1.3. Contributions

To bridge the identified research gaps, this paper proposes a novel method for capacity configuration and benefit distribution in HWSS that explicitly considers grid congestion within a cooperative game framework. The main contributions are threefold:

- A Congestion-Aware Cooperative Game Model: We construct a bi-level joint operation optimization model that incorporates a penalty for grid congestion. This congestion cost is explicitly embedded into the characteristic function of the cooperative game, enabling the precise quantification of the maximum attainable benefits under different coalition structures and reflecting real-world physical limitations.

- A Fairer Benefit Distribution Mechanism: We propose an improved Shapley value model by introducing a comprehensive correction factor that integrates an investment risk factor, a congestion mitigation contribution factor, and a capacity factor. This model ensures a more equitable distribution of coalition gains by accounting for the heterogeneous contributions and risks of each participant.

- Comprehensive Validation and Practical Insights: The proposed method is rigorously validated through a case study based on a high-renewable-penetration base in Qinghai Province, China. Simulation results demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in enhancing total system revenue while significantly reducing congestion costs and curtailment. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis provides valuable insights into parameter influences and system robustness, offering a practical decision-making tool for planners and policymakers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the research methodology, including the cooperative game framework, the bi-level optimization model, and the improved Shapley value model. Section 3 presents the case study, results, and discussion. Finally, Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Description and Game Framework

Traditional single-entity optimization methods (e.g., stochastic programming, robust optimization) are ill-suited for resolving benefit coordination and fair distribution among multiple independent investors. Cooperative game theory, in contrast, is naturally suited for such multi-agent decision environments. It not only unlocks synergistic potential through coalition formation but also utilizes solution concepts like the Shapley value to distribute benefits based on quantified marginal contributions, thereby incentivizing coalition stability—a core advantage unattainable by classical optimization methods.

The game framework decomposes the research object multidimensionally. This paper constructs a game framework containing four key elements for the studied object. The four key elements are the set of players, the strategy space, the coalition structure, and the characteristic function. The characteristic function is defined as the maximum benefit that coalition can obtain through coordinated operation.

2.1.1. System Structure and Players

The players in this game include hydropower investors (H), wind power investors (W), photovoltaic investors (P), and energy storage investors (S). Each player can act independently or form a coalition C (e.g., {H, W} or {H, W, P, S}), achieving maximum total coalition benefit through coordinated planning and operation. The core idea is to form a “virtual power plant” through cooperation to uniformly address grid congestion and achieve win–win outcomes.

Consider an integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage system comprising four heterogeneous power sources. Each investment entity makes strategic decisions during the capacity planning stage. The system structure is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Structure of the integrated Hydro-Wind-Solar-Storage system and schematic of grid congestion.

Figure 1 shows the physical structure schematic of the hydro-wind-solar-storage system studied. This system includes four types of heterogeneous power sources: hydropower (H), wind power (W), solar power (S), and energy storage (S). These four heterogeneous power sources can be configured as a microgrid or provide power in a decentralized manner. They are connected to the grid through a common point of interconnection and deliver power via a single transmission channel. Due to the significant randomness, volatility, and anti-peak regulation characteristics of wind and solar output, inherent contradictions exist with load demand. This inherent contradiction, compounded by “grid congestion” in the transmission channel, inevitably leads to wind/solar curtailment and increased system operating costs. Incorporating the hydro-wind-solar-storage system into a game system and introducing a cooperative game mechanism allows the diverse investment entities to form a coalition, collaboratively plan capacities, and schedule operations. This transforms the physical system in Figure 1 into an economic system with “source-grid-load” synergistic benefits, solving the “congestion” problem, ensuring grid security, optimizing the total coalition benefit and the benefits of individual members.

Based on the physical structure in Figure 1, the following sections construct the cooperative game model, define the strategy space and coalition forms of the players, and build the set of game players as follows:

where —Hydropower investor; —Wind power investor; —Solar power investor; —Energy storage investor.

The strategy space defines the decision range of each investor during the planning stage. The strategy for each player is to choose its suitable installed capacity, where the capacity upper and lower limits satisfy the following set:

where —Lower and upper capacity limits under technical feasibility and policy constraints.

2.1.2. Game Form and Coalition Structure

Based on the aforementioned system structure and strategy space, the corresponding cooperative game form needs to be constructed to analyze synergistic benefits. The cooperative game problem can be formally described as a characteristic function game, where the characteristic function assigns a value to each possible coalition, representing the maximum total benefit achievable by that coalition through coordinated optimization. Players can form any coalition structure, including:

- Independent decision-making: {{H}, {W}, {S1}, {S2}};

- Partial coalitions: e.g., {{H, W}, {S1}, {S2}};

- Grand coalition:{H, W, S1, S2}.

2.1.3. Basic Assumptions

To simplify the model and focus on the core issues, this paper makes the following basic assumptions:

- To capture the realistic scenario where investors coordinate operations while maintaining decision-making autonomy, we assume bounded rationality and information sharing. Players share key operational and cost information within the coalition, but investment decisions remain subject to local information asymmetry. Dispatch coordination is achieved through a central mechanism, reflecting practical cooperation dynamics.

- For model tractability in medium-to-long-term planning, we simplify grid physical constraints. System transmission limits are modeled through nodal electricity prices and congestion penalties, while dynamic stability impacts such as voltage and frequency fluctuations are excluded. This allows the model to focus on economic congestion effects without the complexity of short-term stability analysis.

- To establish a rational basis for evaluating coalition value, we adopt an operational coordination assumption. A unified dispatch strategy is implemented within the coalition, maximizing total coalition benefit during operation optimization. This ensures the characteristic function quantifies maximum achievable synergy, consistent with standard cooperative game applications in energy systems.

2.2. Cooperative Game Model Considering Grid Congestion

2.2.1. Grid Congestion and Its Economic Implications

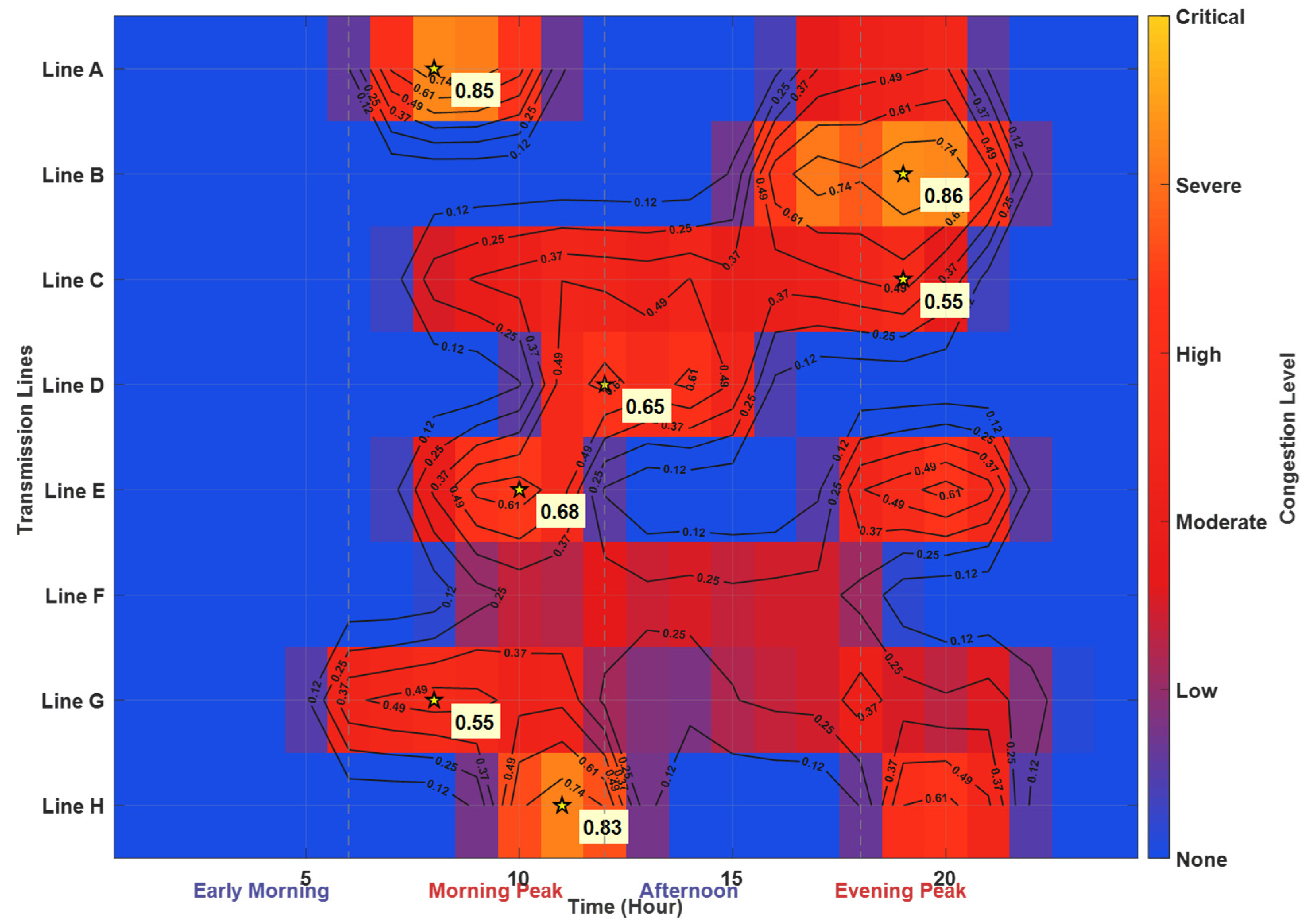

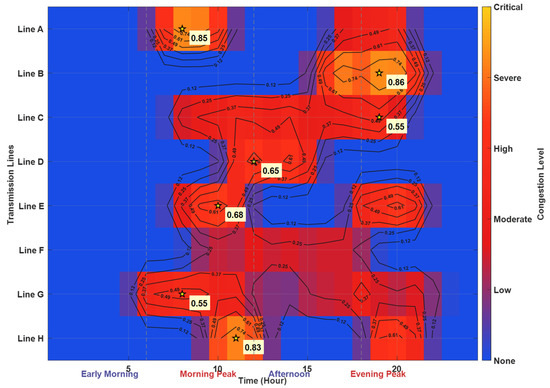

Grid congestion occurs when the power flow on transmission lines or interfaces exceeds their physical limits, preventing economical electricity delivery. In HWSS bases, congestion is a key bottleneck constraining high-proportion renewable integration. As illustrated by the spatiotemporal heatmap in Figure 2, congestion exhibits significant heterogeneity, concentrating during morning and evening peak hours (08:00–12:00 and 17:00–21:00) due to the anti-peak regulation characteristics of wind and solar power.

Figure 2.

Spatio-temporal congestion distribution in Hydro-Wind-Solar-Storage system.

The spatiotemporal heatmap clearly reveals that grid congestion exhibits significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity and regularity. Temporally, congestion is primarily concentrated during the morning and evening peak load hours (08:00–12:00 and 17:00–21:00). This is closely related to the anti-peak-regulation characteristics of wind and solar power generation—wind power output is typically higher at night and lower during the day, while solar generation only occurs during daylight hours, resulting in a low temporal matching degree with load demand. When load demand peaks while renewable energy output is insufficient, the system must rely on conventional power sources, easily leading to power flow violations at critical transmission interfaces. Spatially, the severity of congestion varies significantly across different transmission lines. As the main outward delivery channels, Line A and Line B experience the most severe congestion, with peak congestion levels reaching 0.85 and 0.78, respectively. This is directly attributable to their critical positions within the grid topology and their limited transmission capacities.

Within our cooperative game framework, the economic impact of congestion is modeled as a cost and embedded into the characteristic function. When congestion levels exceed a critical threshold (e.g., 0.7, shown in dark red in Figure 2), the system is forced to curtail renewable energy or dispatch costly reserves, significantly increasing operational costs. Our joint operation model translates this physical constraint into an economic signal via nodal prices and a congestion penalty, guiding power sources to proactively consider congestion mitigation during the capacity planning stage.

Notably, hydropower and energy storage are indispensable for alleviating congestion. Hydropower, with its rapid regulation capability, can increase output during congested peaks, displacing curtailed renewables. Energy storage systems, employing “peak-shaving and valley-filling,” shift energy from congested to non-congested periods, smoothing power fluctuations on transmission corridors. This physical reality forms the basis for introducing the Congestion Mitigation Contribution Factor in our improved Shapley value model.

The cooperative game-based capacity allocation method considering grid congestion, proposed in this paper, is fundamentally grounded in a profound understanding of these spatiotemporal congestion characteristics. By explicitly integrating congestion costs into the cooperative game framework, the system can spontaneously form an optimal “Generation-Grid-Load” coordinated capacity planning solution during the planning phase: appropriately controlling the installation scale of variable renewable energy (wind, solar) while incentivizing the rational allocation of flexible resources (hydropower, storage).

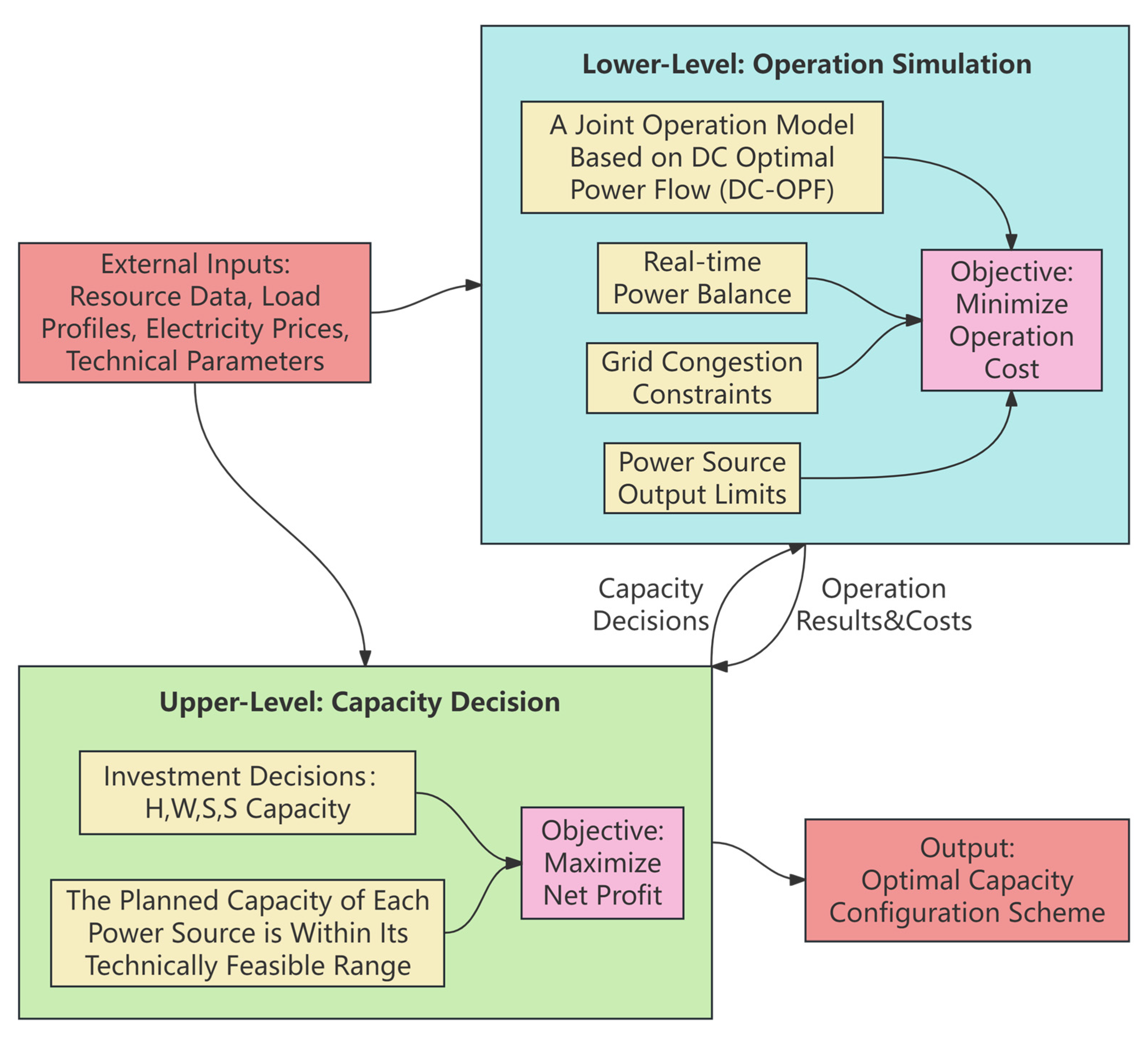

2.2.2. Bi-Level Optimization Framework and Solution Method

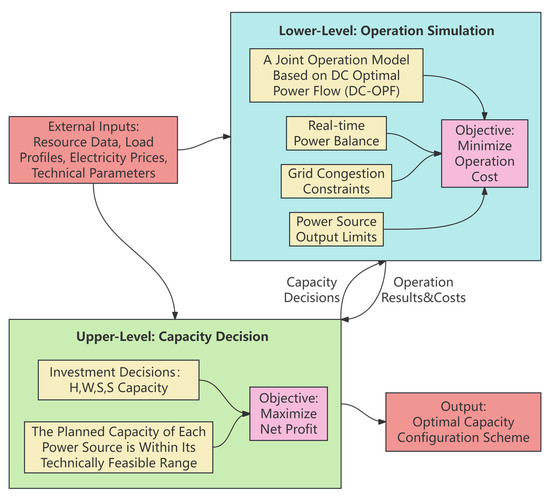

After defining the game framework and basic assumptions, an optimization model capable of precisely quantifying the value of different coalitions needs to be constructed. This model adopts a bi-level optimization structure: the upper level makes capacity planning decisions, while the lower level simulates the system’s joint operation, thereby closely coupling long-term planning with short-term operation. The schematic of the bi-level optimization framework is shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Schematic of the Bi-Level optimization framework.

The upper-level planning is the capacity decision layer. Its objective function aims to maximize the net benefit of the coalition over its entire lifecycle, comprehensively considering various revenues and costs during the operational period and deducting the initial investment cost. The objective function is:

where —Total revenue; —Investment cost; —Operation and maintenance cost; —Congestion cost.

To ensure the planned capacity of each power source is within its technically feasible range, the decision variable in the objective function is subject to the following constraints:

where —Installed capacity selected for power source (e.g., H, W, S, S) during the planning stage; —Minimum installed capacity for power source under technically feasible conditions; —Maximum installed capacity for power source under technically feasible conditions.

The lower-level planning is the operation simulation layer, employing a joint operation model based on DC optimal power flow (DC-OPF) to simulate the coalition’s actual dispatch behavior under grid physical constraints. It ensures the minimization of coalition operating costs while satisfying line power constraints and power source output limits. The objective function is:

where —Total number of time intervals in the dispatch period; —Operating cost of power source at time ; —Congestion cost at time .

The objective of the lower-level model is to minimize the total operating cost of the coalition, including generation costs and penalty costs due to line congestion, primarily achieved through the following balance and constraints.

- Real-time Power Balance

The power balance constraint must be satisfied, meaning the total output of the coalition at any time should meet the load demand, maintaining real-time system power balance. The balance equation is:

where —Load demand at time .

- Grid Congestion Constraints

The key cause of grid congestion is reflected in the line power flow constraints, i.e., the power flow on each line does not exceed its transmission limit. The constraint equation is:

where —Power flow on line at time ; —Transmission limit of line .

2.2.3. Detailed Modeling of Revenue and Cost Functions

To accurately calculate the coalition’s benefits, its various revenues and costs need to be modeled in detail.

- Electricity Revenue

Based on electricity sales methods in the power market, electricity revenue can be expressed as:

where —Electricity price at time (CNY/kWh); —Output of power source at time (kW); —Time interval duration (h).

- Ancillary Service Revenue

Ancillary service revenue reflects the compensation flexibility resources receive for providing ancillary services:

where —Reserve capacity compensation price for power source ; —Regulation service compensation price for power source ; —Regulation energy provided by power source .

- Investment Cost

The model annualizes the initial investment cost for economic comparison over the entire lifecycle:

where —Unit capacity investment cost for power source (CNY/kW); —Discount rate; —Economic life of power source (years).

- Operation and Maintenance Cost

This cost is proportional to the installed capacity of the power sources, representing the system’s fixed O&M expenditure:

where —Fixed O&M cost rate for power source .

- Congestion Cost

This cost term introduces the physical constraint of grid congestion into the objective function as an economic penalty, encouraging planning and operation schemes to avoid congestion.

where —Congestion penalty coefficient for line ; —Power flow on line at time ; —Transmission limit of line .

2.3. Benefit Distribution Model Based on Improved Shapley Value

2.3.1. Classical Shapley Value Theory

After quantifying the value of each coalition through the characteristic function, the next key issue is how to fairly distribute the total benefits within the grand coalition (i.e., the coalition of all players) to ensure cooperation stability.

The Shapley value, a seminal solution concept in cooperative game theory, provides a unique and fair distribution scheme based on each player’s marginal contribution to every possible coalition they could join. Its core principle is that a player’s payoff should reflect their average importance to the collective effort.

The underlying logic of the Shapley value can be understood in three steps. First, consider Every Possible Scenario: imagine all players joining the grand coalition one by one, in every possible joining order. Second, calculate Marginal Contributions: in each specific joining sequence, when a player joins, they bring a certain additional value to the existing coalition. Third, average the Contributions: the Shapley value for a player is simply the average of their marginal contributions across all possible joining sequences. This ensures that the distribution does not depend on the order of formation, which might be arbitrary.

For a cooperative game , the Shapley value for player is defined as:

where —Any subset not be contained; —Weighting factor for permutation; —Marginal contribution of player to coalition .

However, the classical method has limitations: it only considers the player’s marginal contribution to the coalition, neglecting (1) differences in investment risk (wind/solar investments have higher uncertainty); (2) the actual contribution to congestion mitigation (hydropower peak shaving, energy storage peak shaving and valley filling have greater value); (3) individual rationality constraints. To address these shortcomings, this paper improves the Shapley value model for the game analysis.

2.3.2. Improved Shapley Value Model

To resolve the limitations of the classical method, this paper proposes an improved Shapley value model incorporating a comprehensive correction factor.

The comprehensive correction factor is constructed as follows:

where the weight coefficients satisfy: . The weighting factors comprehensively consider heterogeneity across three dimensions: investment risk, congestion mitigation contribution, and capacity scale. The factors , , are analyzed below.

- Investment Risk Factor

The investment risk factor quantifies the uncertainty of different power source investments, aiming to reasonably compensate high-risk investors and enhance their willingness to cooperate. Calculation method:

where —Output volatility rate of power source ; —Investment cost volatility rate of power source .

Calculation method for volatility rates:

- Congestion Mitigation Contribution Factor

The congestion mitigation contribution factor quantifies the value of each power source in alleviating the system’s key contradiction, thereby reflecting its contribution to grid security in the distribution. Calculation method:

where —Congestion indicator function for line at time ; —Contribution degree of power source to mitigating congestion on line at time ; is the set of players, is the set of lines, is the total number of time periods.

is the relative value of the congestion indicator function , reflecting the impact value of each power source on alleviating the system’s key contradiction. The calculation method for is as follows:

Here, the coefficient of 0.9 is introduced to reflect the practical operational safety margin required for power sources, preventing equipment overload and ensuring system security and stability.

- Capacity Factor

The capacity factor reflects the relative proportion of the power source’s installed capacity within the coalition, embodying its scale contribution. Calculation method:

2.3.3. Calculation of the Improved Shapley Value

First, perform normalization processing for the comprehensive correction factor:

where —Normalized comprehensive correction factor for player ; —Original comprehensive correction factor for player ; —Sum of original comprehensive correction factors for all players.

Then calculate the improved Shapley value:

This correction method adjusts the classical Shapley value based on the comprehensive correction factor , enabling the distribution result to more comprehensively reflect the heterogeneous contributions of the players.

2.3.4. Weight Determination Method

A combination weighting method is used to determine the weight coefficients , which balance the objective laws of data and the subjective experience of decision-makers. The combination weighting can be calculated using the following two methods.

- Entropy Weight Method (Objective Weight)

- Analytic Hierarchy Process—AHP (Subjective Weight)

The subjective weight vector is determined using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to incorporate expert judgment. The construction process is as follows: First, experts in the field are invited to perform pairwise comparisons of the three factors—investment risk, congestion mitigation contribution, and capacity scale—based on their relative importance to the long-term stability of the coalition. These comparisons are structured into a judgment matrix , where each element represents the relative importance of factor compared to factor , using the standard Saaty’s 1–9 scale (e.g., 1 for equal importance, 9 for extreme importance). Subsequently, the eigenvector corresponding to the principal eigenvalue of matrix is calculated and normalized to obtain the subjective weight vector . To ensure the logical consistency of expert judgments, a consistency check is performed on the matrix. The Consistency Ratio (CR) is calculated, and a value of CR < 0.1 is considered acceptable.

Construct a judgment matrix through expert scoring and calculate the eigenvector to obtain the subjective weight . Combination Weight:

where is the combination coefficient.

2.3.5. Coalition Stability Check

To ensure the stable operation of the cooperative coalition, the benefit distribution scheme must be checked against the following conditions:

- Individual Rationality Condition

This condition ensures that each participant’s benefit after cooperation is not less than their benefit from independent decision-making.

- Group Rationality Condition

This condition ensures that the total benefits of the grand coalition are fully distributed.

- Coalition Stability Indicator

Coalition stability is measured by a stability index, defined as follows:

When StabilityIndex > 0, it indicates that all participants’ cooperative benefits are higher than their independent benefits, meaning the coalition is considered stable. This indicator measures the degree of benefit improvement for the least stable member in the coalition.

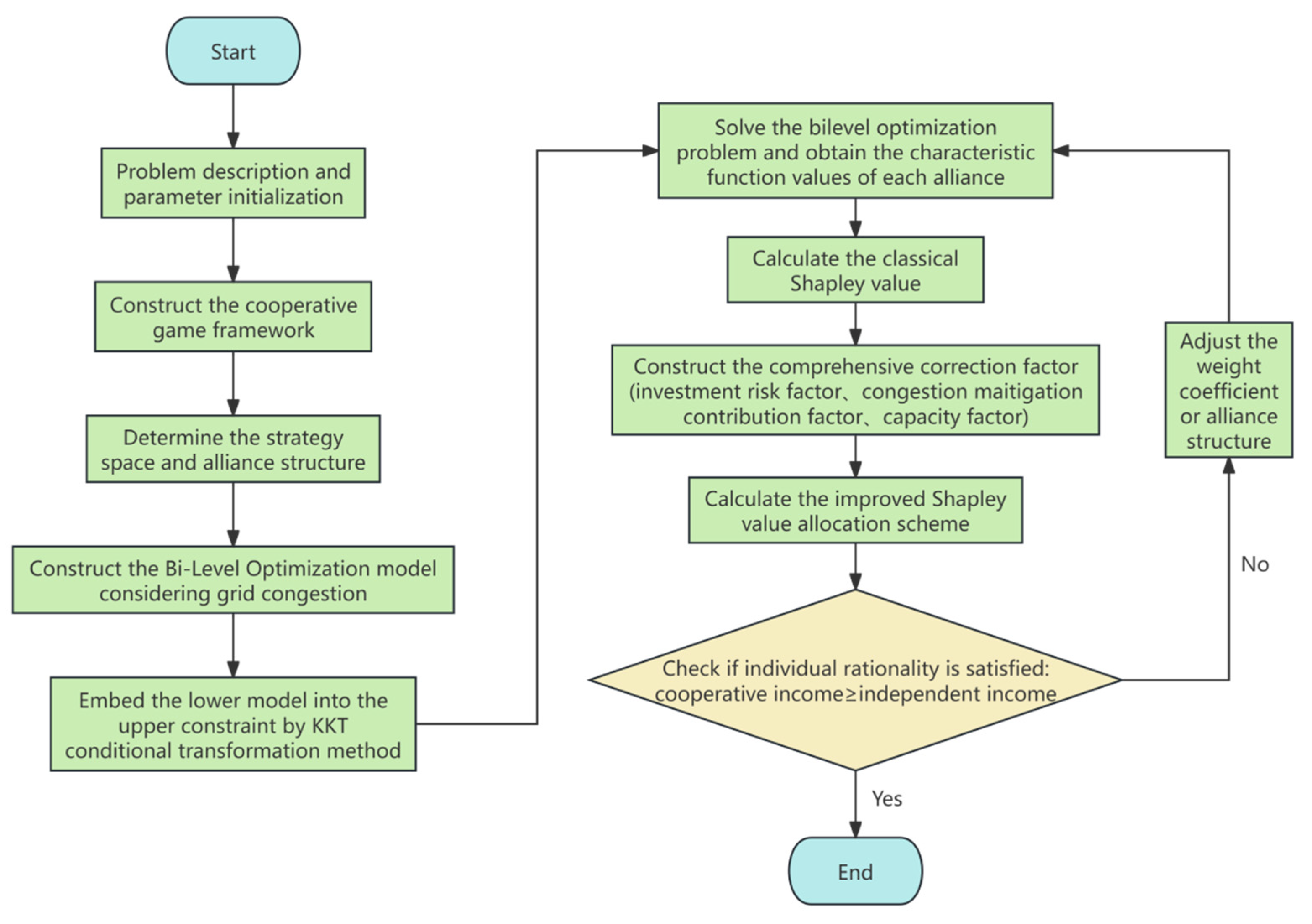

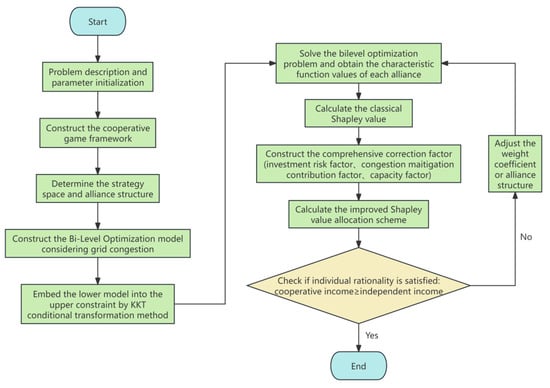

The complete solution flowchart for the proposed hybrid algorithm for “Capacity Allocation and Benefit Distribution Considering Grid Congestion and Cooperative Games” is shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the cooperative game capacity allocation and benefit distribution algorithm.

The flowchart starts with problem description and parameter initialization, sequentially including core steps such as cooperative game modeling, joint operation optimization, characteristic function calculation, and Shapley value calculation, finally outputting the optimal capacity configuration scheme and performing a coalition stability check.

The core logic of this flowchart can be summarized as “One Framework, Two-Level Optimization, Threefold Improvement”:

- One Framework: The cooperative game framework runs throughout, transforming the physical system’s capacity allocation problem into an economic system’s coalition formation and benefit distribution problem.

- Two-Level Optimization: Reflects the temporal coupling of capacity planning and joint operation. The upper level makes long-term capacity decisions, the lower level performs short-term operation simulation, and the two interact through iterative feedback to ensure the feasibility and economy of the planning scheme at the operational level.

- Threefold Improvement: Focus on the distribution of benefits. Addressing the shortcomings of the classical Shapley value method, the algorithm introduces the investment risk factor, congestion mitigation contribution factor and capacity factor to form a comprehensive correction factor, performing refined adjustment of the distribution results. This improvement ensures that the benefit distribution can more fairly reflect the heterogeneity of participants in terms of investment risk, system functional value, and scale contribution, thereby fundamentally enhancing coalition stability.

As seen from the flowchart, this paper deeply embeds grid physical constraints into the economic model of game theory, combining the two to achieve optimal capacity configuration for hydro-wind-solar-storage systems under the benefit distribution of cooperative games.

3. Case Study

3.1. Data Description and Scenario Setting

3.1.1. Basic Data Sources

This case study takes an integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage base in Qinghai Province as the research object. This base boasts abundant wind and solar resources (with annual utilization hours of approximately 2200 and 1600 h, respectively) and strong hydropower regulation capability (e.g., from large hydro plants like Longyangxia). However, its transmission channel capacity is limited (set at 500 MW), making it prone to grid congestion during periods of high renewable generation, thus constituting a typical scenario for validating the proposed model. The load curve data was cited from the Qinghai Power Grid typical daily load database, which exhibits a daily peak-to-valley difference rate of about 35%, further intensifying the system’s peak-shaving and transmission congestion challenges.

- Wind and solar resource data: Sourced from the “Qinghai Province Wind and Solar Energy Resource Assessment Report (2022).”

- Hydropower regulation capability: Based on the dispatch logs of the Upper Yellow River Hydropower Company (2021–2023).

- Load curve: Cited from the Qinghai Power Grid typical daily load database.

- Economic parameters: Referenced from the “China New Energy Power Generation Cost White Paper (2023).”

- Key grid sections: The transmission limit of the base’s outgoing transmission channel is selected as 500 MW to simulate congestion scenarios.

3.1.2. Economic and Technical Parameters

Parameter values are shown in Table 1, including investment cost, O&M cost, electricity price, congestion penalty coefficient, etc. These parameters are calibrated based on industry reports and literature (e.g., references [1,3,10]) and discounted to the full lifecycle.

Table 1.

Economy and technical parameter setting.

The economic and technical parameters listed in Table 1 are calibrated based on industry benchmarks, notably the “China New Energy Power Generation Cost White Paper (2023),” and the relevant literature to ensure practical relevance. The rationale for key parameter categories is as follows:

Unit Investment Cost and Economic Life: The specified costs for hydropower, wind, PV, and storage reflect their respective technological maturity and infrastructure requirements. The lower unit cost but shorter economic life for energy storage is typical of current battery technology. All initial investments are annualized over the project’s economic life using the given discount rate (8%) for a consistent lifecycle economic comparison.

Fixed O&M Cost Rate and Operating Cost Coefficient: The Fixed O&M Cost Rate, expressed as a percentage of the investment cost, accounts for regular maintenance and administrative expenses. The slightly higher rates for wind and storage indicate their more complex maintenance needs. The Operating Cost Coefficient represents the marginal variable cost of generation. The higher values for hydropower and storage reflect the operational costs associated with water usage and cycle degradation, respectively, while the near-zero cost for wind and PV is consistent with their negligible fuel expenses.

Electricity Rate and Ancillary Service Price: The electricity price is set within a range to simulate market dynamics. Hydropower is assumed to participate in both the energy and ancillary service markets, with the compensation prices reflecting typical standards from pilot electricity markets in China, acknowledging its superior regulation capability.

Blocking Penalty Coefficient and Line Transmission Limit: The Blocking Penalty Coefficient is a crucial parameter that internalizes the physical grid constraint as an economic signal. Its value is set to be high enough to effectively guide capacity configuration decisions towards mitigating congestion, but not so high as to unduly suppress economic activity. The transmission limit for the key interface is set based on the typical constraints of the studied Qinghai base, representing the core physical bottleneck that triggers congestion.

3.1.3. Improved Shapley Value Model Parameters

- Values for investment risk factor : Wind , Solar , Hydro , Storage .

- Weight coefficients: Using the combination weighting method (Entropy Weight + AHP), set (investment risk), (congestion mitigation contribution), (capacity). Robustness verified via sensitivity analysis.

3.1.4. Scenario Parameter Settings

Scenario 1: Independent decision-making (Non-cooperative game Nash equilibrium), each power source optimizes capacity separately, without considering cooperation.

Scenario 2: Cooperation but ignoring grid congestion, coalition optimization neglects congestion constraints.

Scenario 3: Cooperation and considering grid congestion (Proposed model), coalition optimization embeds congestion penalties.

Scenario 4: Post-cooperation using classical Shapley value distribution, allocating benefits based solely on marginal contribution.

Scenario 5: Post-cooperation using the proposed improved Shapley value distribution, introducing the comprehensive correction factor.

3.2. Result Analysis and Discussion

3.2.1. Capacity Allocation and Economic Comparison

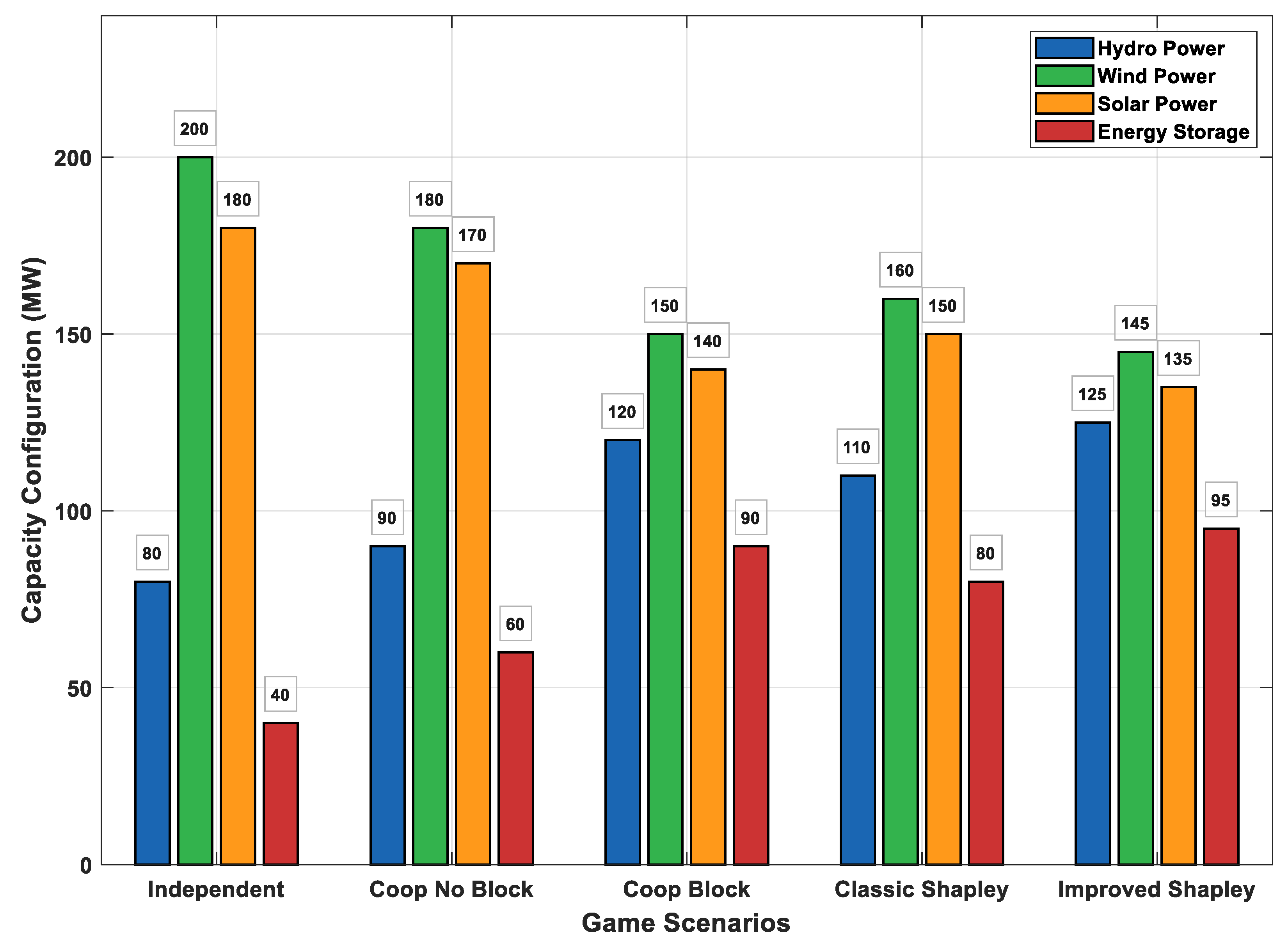

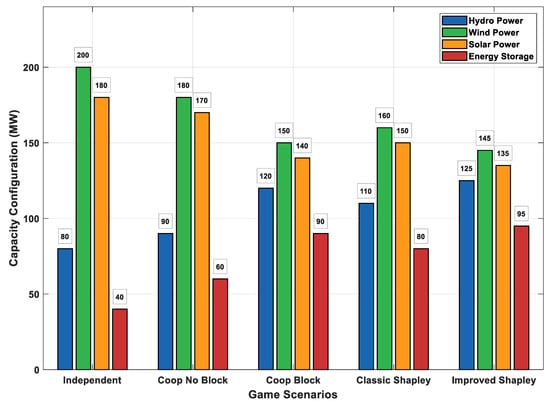

The equilibrium capacity allocation results for hydropower (H), wind power (W), photovoltaic (P), and energy storage (S) under the five game scenarios are systematically displayed using grouped bar charts, as shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

Capacity configuration comparison across different game scenarios.

In Scenario 1 (independent decision-making), each investment entity made decisions based on individual rationality, leading to over-expansion of volatile wind and solar capacity (reaching 200 MW and 180 MW, respectively), while the configuration of flexible hydropower and energy storage was severely insufficient (80 MW and 40 MW, respectively).

After introducing the cooperative game mechanism (Scenario 2), the overall system coordination improved, wind and solar capacity were rationally restrained, and the energy storage configuration increased to 60 MW. When further considering the key physical constraint of grid congestion (Scenario 3, the core model of this paper), the system’s power source structure underwent significant optimization: to effectively alleviate transmission bottlenecks, the configuration capacities of highly flexible resources, hydropower and energy storage, were fully incentivized, drastically increasing to 120 MW and 90 MW, representing increases of 50% and 125%, respectively; meanwhile, the capacities of more volatile wind and solar were reasonably limited to 150 MW and 140 MW.

The evolution of the configuration structure clearly shows that the “physical–game” coupling model constructed in this paper can, through a market-oriented cooperation mechanism guided by grid security constraints, spontaneously form an optimal capacity planning scheme that balances economy, security, and reliability.

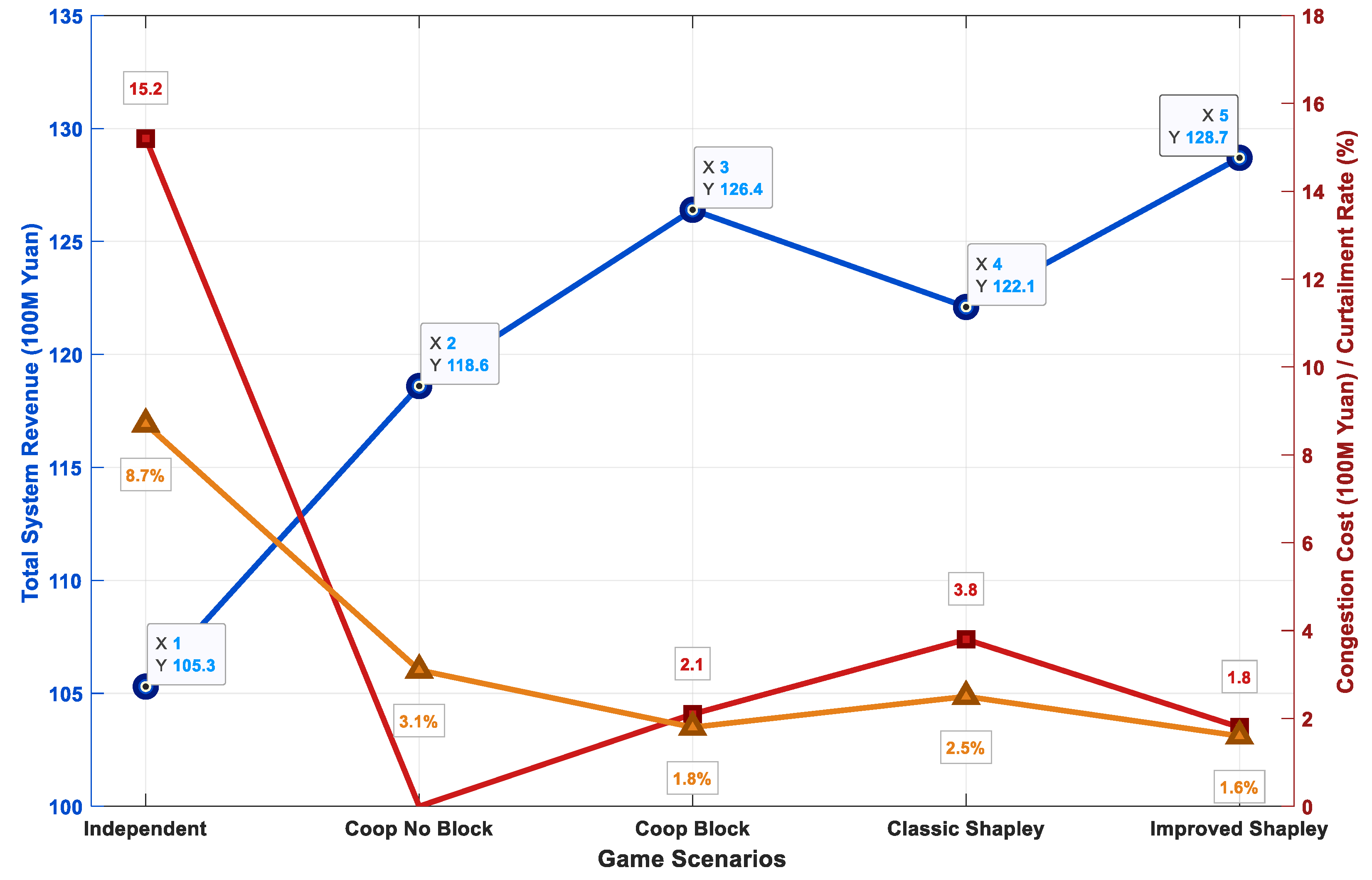

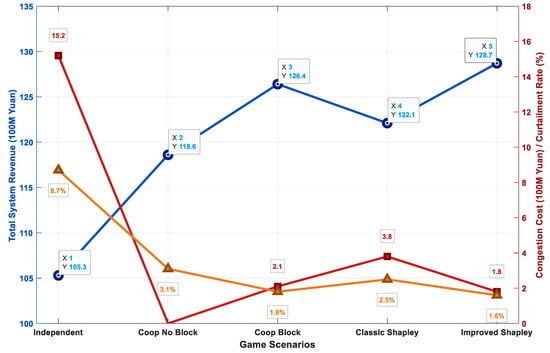

A dual-Y-axis line chart was used to quantitatively evaluate and compare the economic dimensions of the different game scenarios, as shown in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Economic performance comparison across different game scenarios.

The results show that Scenario 3 (cooperation considering congestion) achieved the highest total system revenue (12.64 billion CNY), an economic improvement of 20.1% compared to Scenario 1 (independent decision-making) at 10.53 billion CNY. Regarding operating costs, the congestion cost and wind/solar curtailment rate in Scenario 3 both dropped to very low levels, 210 million CNY and 1.8%, respectively, representing reductions of 86.2% and 79.3% compared to Scenario 1 (1.52 billion CNY and 8.7%).

Further analysis shows that although Scenario 2 (cooperation ignoring congestion constraints) achieved an ideal state of zero congestion cost, its total system revenue (11.86 billion CNY) was significantly lower than Scenario 3. This reveals that “idealized” cooperation schemes ignoring physical constraints may lead to economically suboptimal decisions. Scenario 5 (using the improved distribution method) further optimized based on Scenario 3, achieving the highest total revenue of 12.87 billion CNY, proving the positive promoting effect of fair benefit distribution on overall coalition efficiency.

Comprehensive economic indicator analysis shows that by deeply embedding grid congestion constraints into the cooperative game framework, the proposed model successfully guides system decisions from the Nash equilibrium of “individual rationality” to the Pareto optimum of “collective rationality”, significantly enhancing overall economic benefits while strongly ensuring power system operational security and efficient renewable energy integration. Table 2 provides the economic indicators for each scenario:

Table 2.

Comparison of economic indicators.

Scenario 3 has the highest total system revenue and the lowest congestion cost and wind/solar curtailment rate, demonstrating the dual necessity of cooperation (Scenario 3 vs. Scenario 1) and considering congestion (Scenario 3 vs. Scenario 2).

3.2.2. Benefit Distribution and Coalition Stability Analysis

Table 3 compares the distribution results of the classical and improved Shapley values.

Table 3.

Comparison of benefit distribution results.

Under the improved method, the distribution proportions for hydropower (H) and energy storage (S), which contribute significantly to congestion mitigation, increased notably, while the proportions for wind (W) and solar (S), which have higher investment risks, decreased slightly, making the distribution fairer.

The coalition stability check verified that under the improved Shapley value distribution, all participants satisfy , meaning their benefits after cooperation are higher than acting alone, ensuring coalition stability.

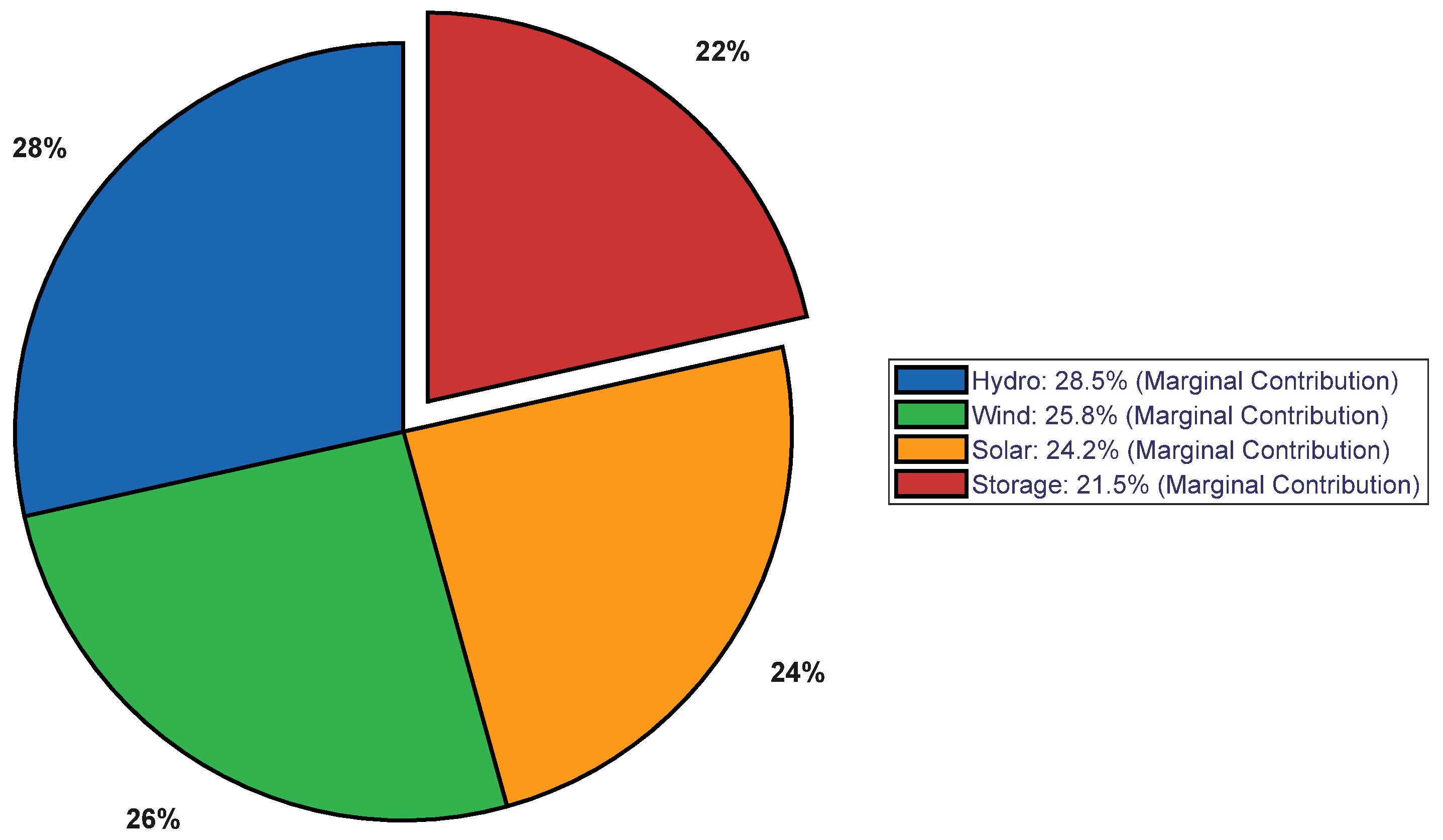

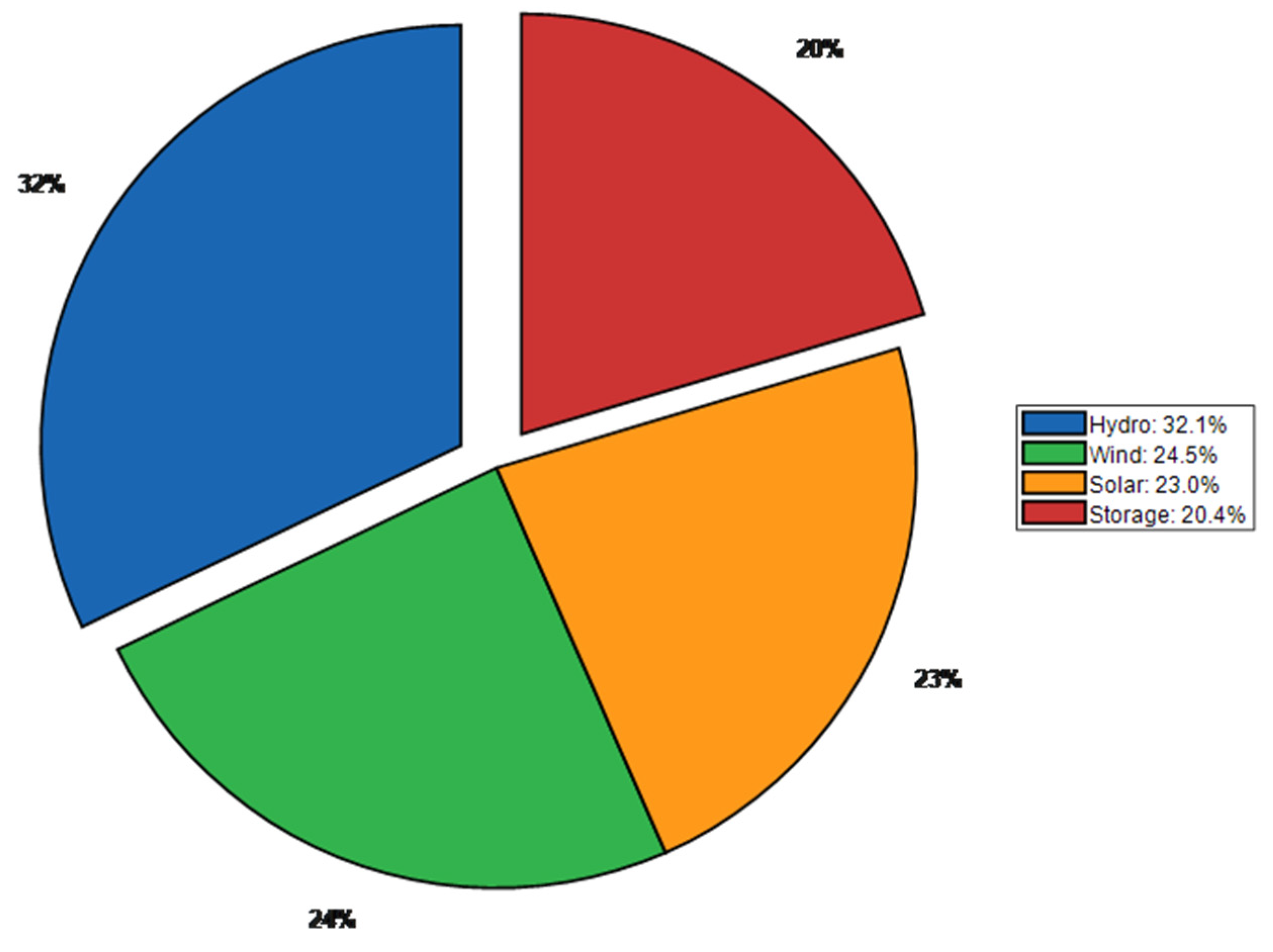

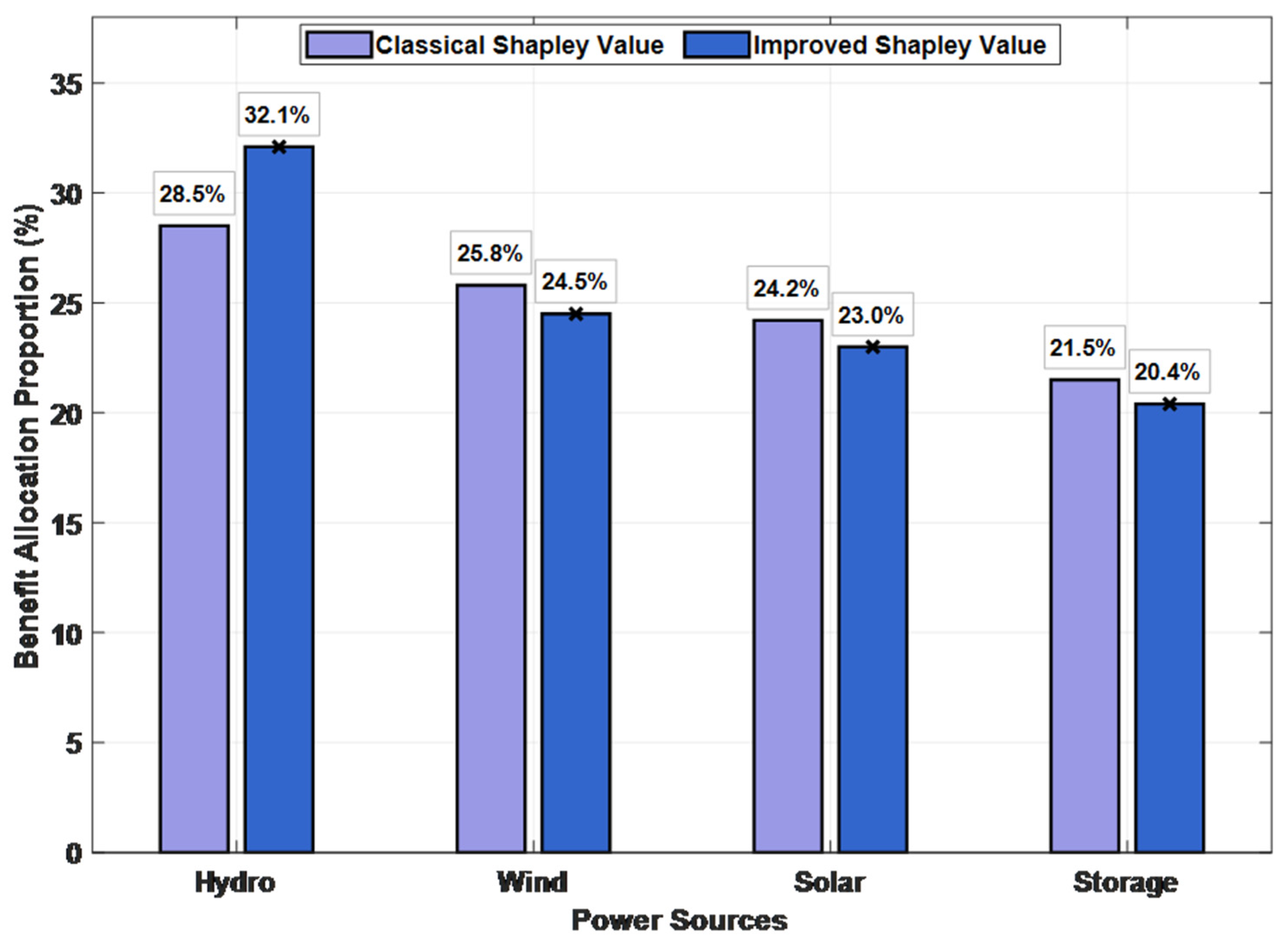

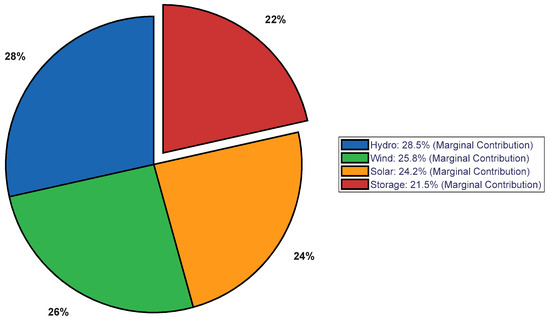

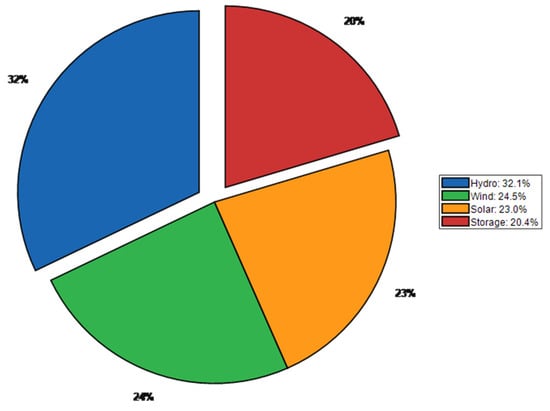

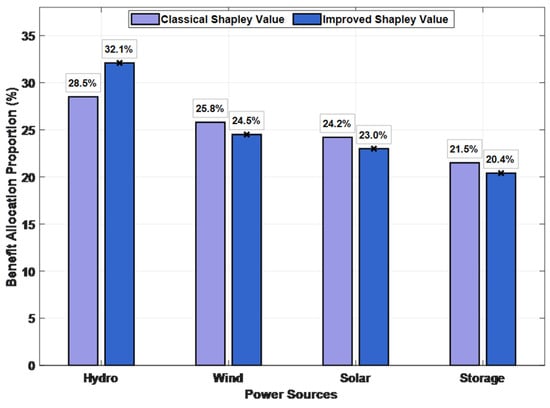

Figure 7 and Figure 8 visually compare the benefit distribution results of the classical Shapley value method and the proposed improved method using pie charts. Under the classical method (Figure 6), the benefit proportions of each power source are roughly consistent with their marginal contributions but fail to reflect the heterogeneity of their functional values. After applying the improved Shapley value method (Figure 7), the distribution structure changed significantly: hydropower’s revenue share increased from 28.5% to 32.1%, and energy storage’s share remained at a relatively high level of 20.4%. This change stems from the congestion mitigation contribution factor introduced in the improved method, which quantifies and compensates for the additional value created by hydropower and energy storage for the coalition through peak shaving and congestion alleviation, making the distribution result more aligned with the fair principle of “distribution according to contribution”.

Figure 7.

Classical Shapley value benefit allocation.

Figure 8.

Improved Shapley value benefit allocation.

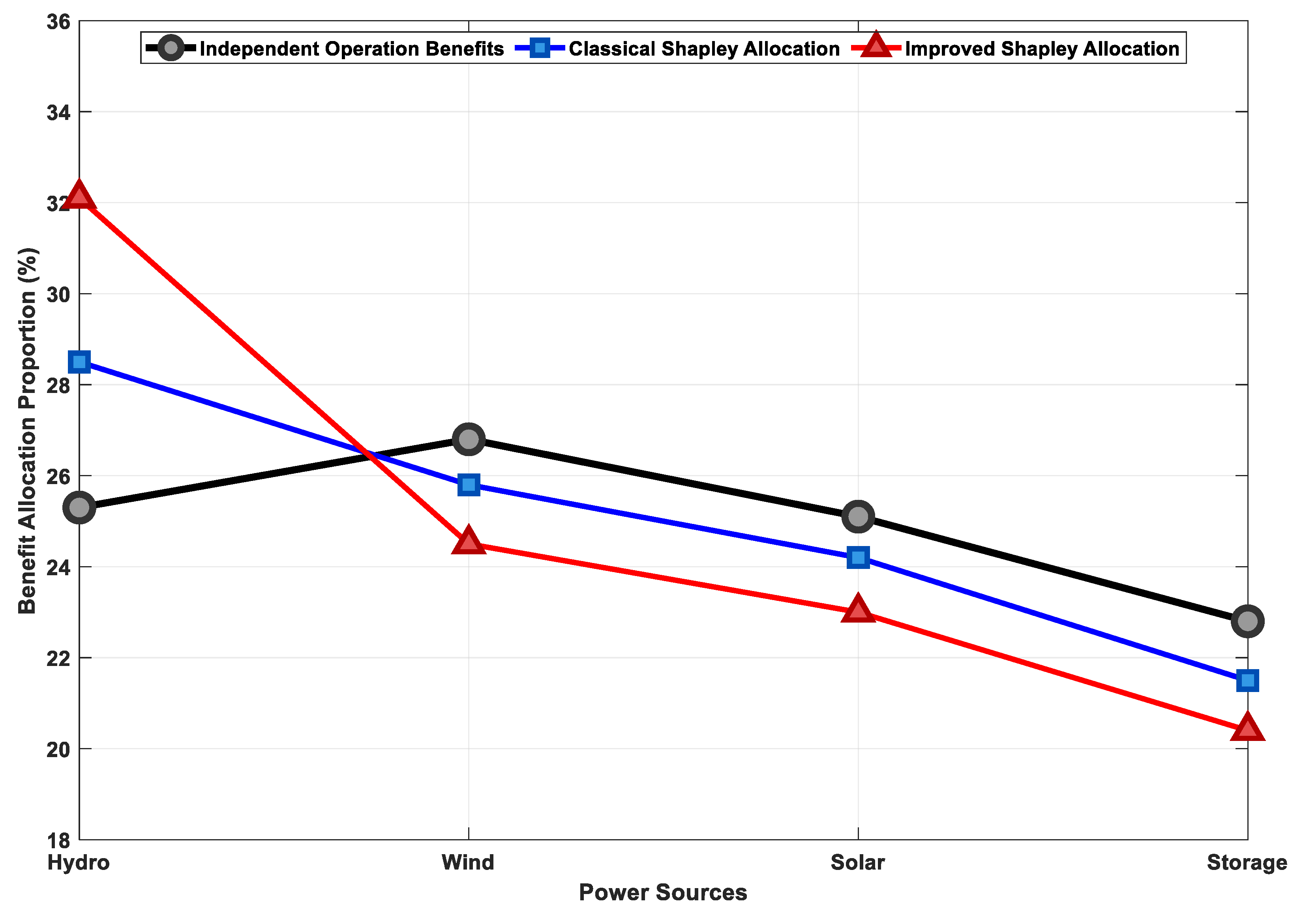

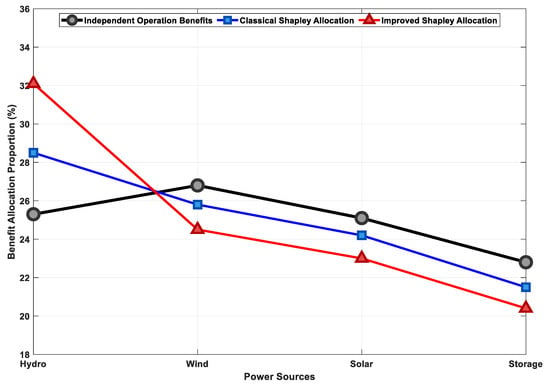

Figure 9 quantifies the changes in distribution proportions using a bar chart, clearly showing that the improved method reasonably tilts benefits towards flexible resources. Figure 10 provides a key verification of coalition stability. It shows that, regardless of using the classical or improved method, the benefits obtained by all participants after cooperation (the “Classical Allocation” and “Improved Allocation” curves) are higher than their benefits from independent decision-making (the “Independent Revenue” curve); i.e., satisfying the “individual rationality” condition of cooperative games. Particularly for wind and solar, whose revenue shares decreased under the improved method, their cooperative benefits still exceed their independent benefits, ensuring their motivation to participate in the coalition. This proves that the proposed improved distribution scheme is not only theoretically fairer but also practical, serving as the cornerstone for maintaining long-term coalition stability.

Figure 9.

Classical vs. improved Shapley value allocation comparison.

Figure 10.

Coalition stability analysis: individual rationality verification.

3.2.3. Multi-Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and System Robustness Evaluation

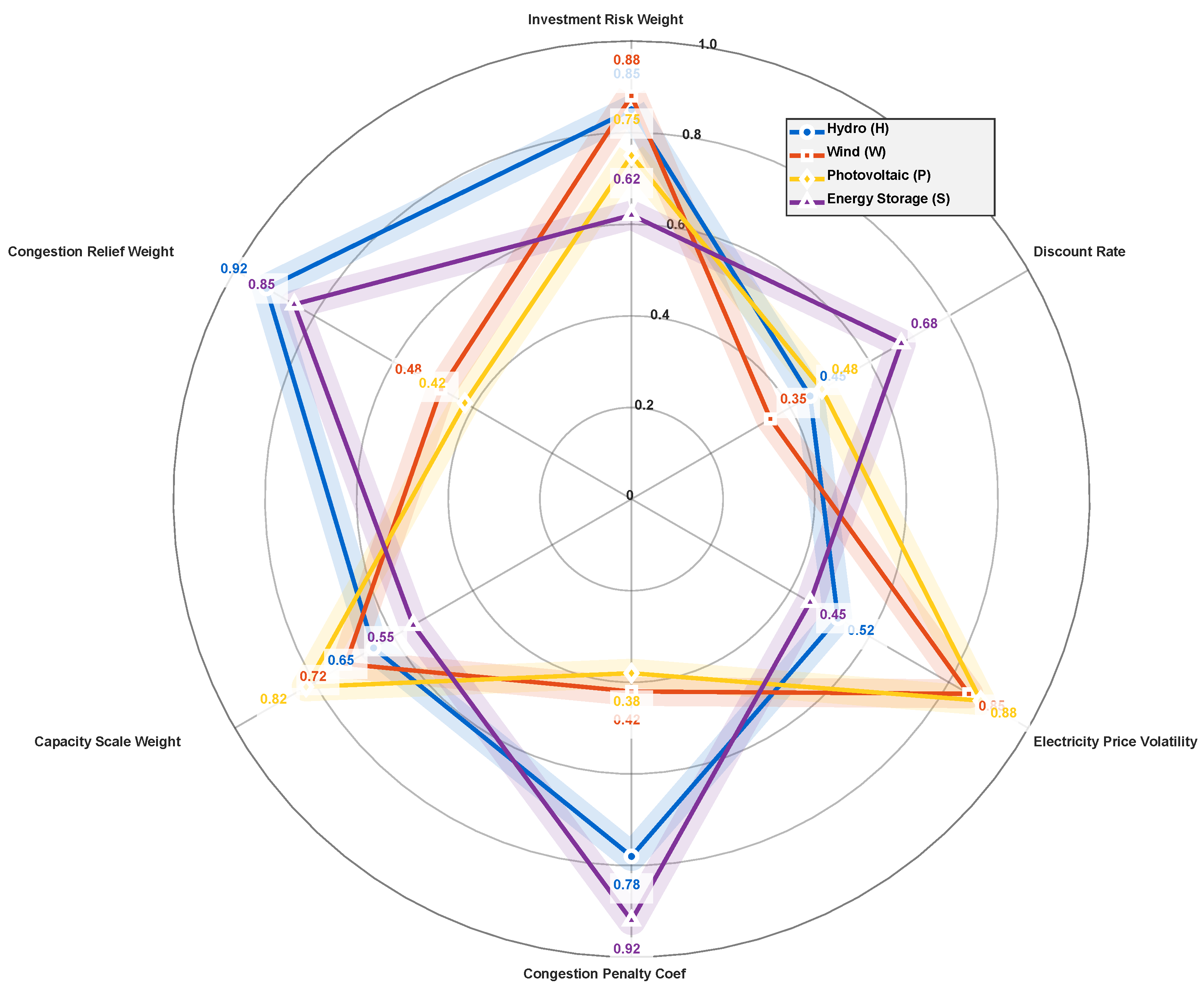

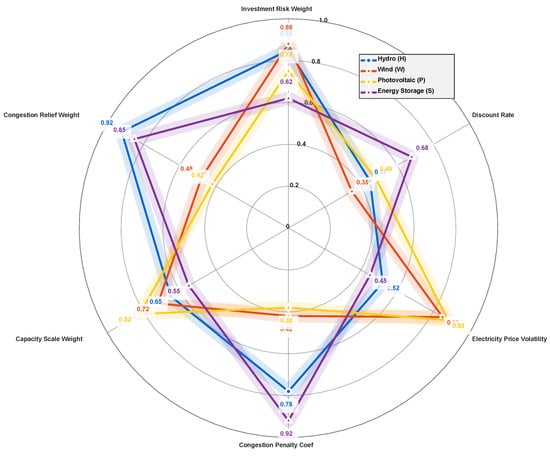

To further validate the robustness of the proposed cooperative game model and the improved Shapley value allocation method, a systematic multi-parameter sensitivity analysis was conducted. The radar chart in Figure 11 quantifies the sensitivity of each power source to six key parameters from different dimensions: investment risk weighting, congestion mitigation weighting, capacity scale weighting, congestion penalty coefficient, electricity price volatility, and discount rate. The analysis results reveal a significant functional differentiation in parameter sensitivity among different power sources, a finding that aligns well with the theoretical framework of the cooperative game constructed in this study.

Figure 11.

Multi-Parameter sensitivity analysis for hybrid energy system.

Hydropower (H) exhibits high sensitivity to parameters related to congestion mitigation (congestion mitigation weighting: 0.92, congestion penalty coefficient: 0.78). This is entirely consistent with its core functions of peak-shaving and congestion mitigation within the system. During peak load hours with severe grid congestion, hydropower, leveraging its rapid regulation capability and reservoir storage characteristics, can effectively displace curtailed renewable energy. This constitutes the physical basis for introducing the Congestion Mitigation Contribution Factor in the improved Shapley value. Wind power (W) and Solar power (S) are most sensitive to the investment risk weighting (0.88 and 0.75, respectively), reflecting the high uncertainty characteristics of wind and solar investments—their output possesses significant randomness and volatility, leading to relatively high investment recovery risks. This finding validates the necessity of considering the investment risk factor in benefit distribution; providing reasonable compensation to high-risk investors can enhance their willingness to participate in cooperation.

The sensitivity pattern of Energy Storage (S) is particularly distinct. It shows the highest sensitivity to the congestion penalty coefficient (0.92), while also being moderately sensitive to the capacity scale weighting (0.55). This characteristic accurately corresponds to the system’s “spatiotemporal energy transfer” function: through its “peak-shaving and valley-filling” operational strategy, energy storage can shift energy from congested periods to non-congested periods, directly alleviating power flow limit violations on transmission corridors. Within the cooperative game framework, this unique value of energy storage is explicitly translated into an economic signal, influencing capacity allocation decisions through the internalization of congestion penalty costs.

The sensitivity analysis also reveals synergies and trade-offs among parameters. The investment risk weighting and the congestion mitigation weighting correspond to the system’s economic efficiency and security objectives, respectively, and exhibit a certain trade-off relationship when influencing the benefit distribution of each power source. When the investment risk weighting increases, the revenue shares of wind and solar power increase accordingly; whereas when the congestion mitigation weighting increases, the allocation proportions of hydropower and energy storage increase significantly. This differentiated distribution of parameter sensitivity provides decision-makers with flexible policy adjustment space: depending on the specific strategic orientation of energy development, weight coefficients can be adjusted to achieve different distribution objectives.

From the perspective of overall system robustness, the sensitivities of all power sources to the discount rate and electricity price volatility are generally at a moderate level (0.35–0.52), indicating that the proposed model possesses good robustness against changes in long-term economic parameters. This characteristic is particularly important for the long-term planning of integrated hydropower-wind-solar-storage bases, as such projects typically have long investment payback periods and require a certain degree of adaptability to future market environment changes.

In summary, the sensitivity analysis results demonstrate that the proposed “cooperative game-based capacity allocation and benefit distribution model considering grid congestion” is not only theoretically innovative, but also exhibits good parameter adaptability and system robustness in practical application. The sensitivity characteristics of each power source highly align with their physical functions and economic roles within the system, proving the rationality and practicality of the model design. This analysis provides a more scientific decision-making basis for the collaborative planning of diversified investment entities, contributing to promoting the high-quality development of integrated hydropower-wind-solar-storage bases in practice.

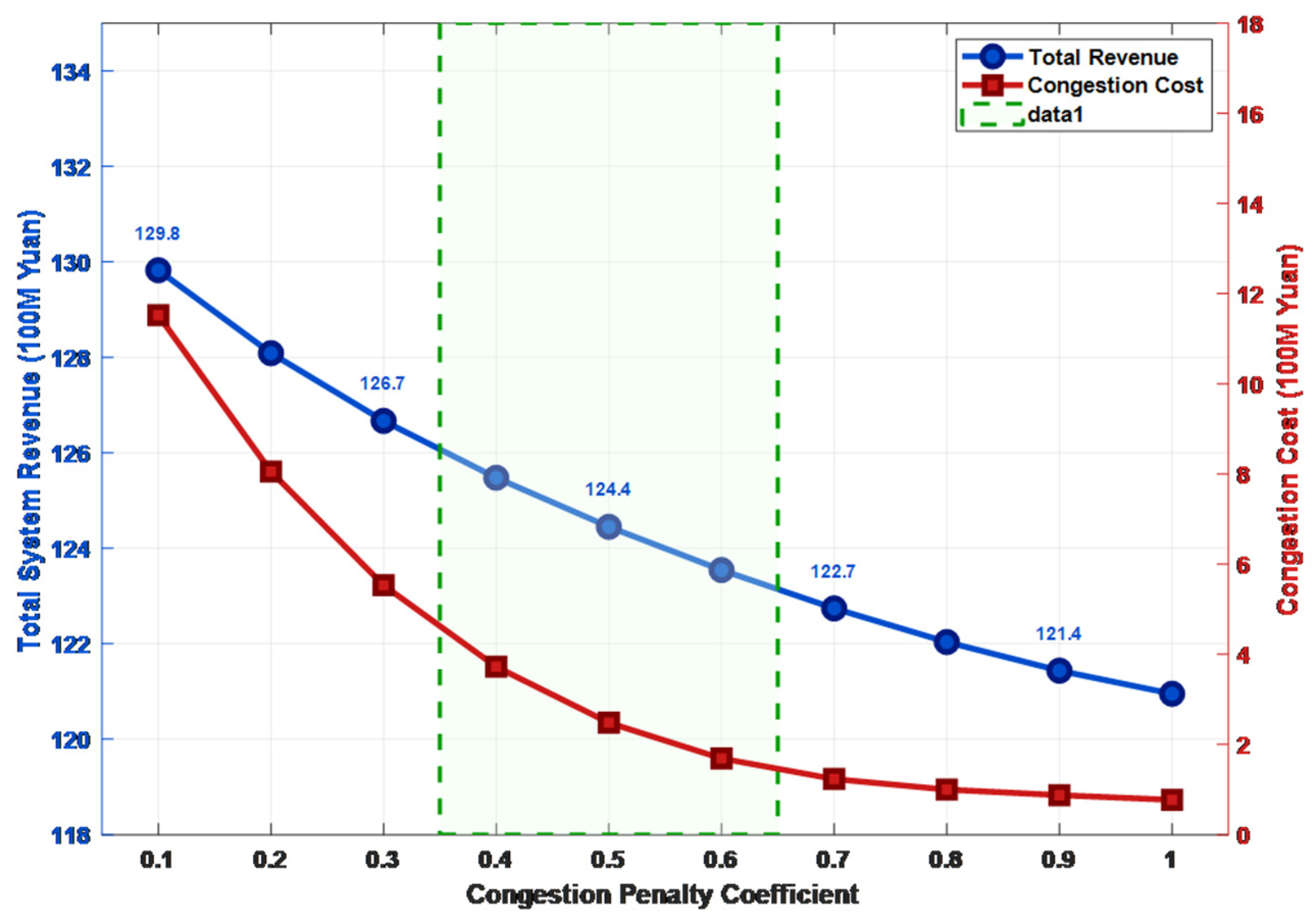

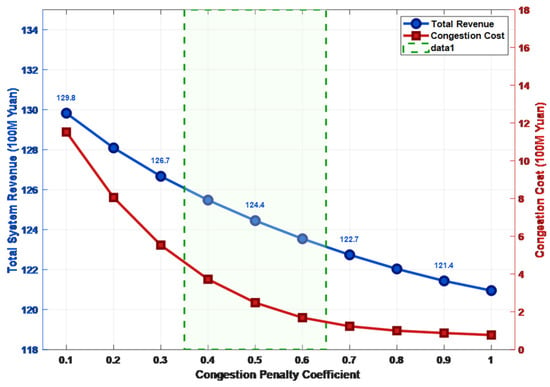

Figure 12 reveals the impact mechanism of the congestion penalty coefficient on system economics. As the penalty coefficient increases, the congestion cost decreases exponentially, indicating that increasing the congestion penalty can effectively suppress line overloads. The total system revenue initially rises rapidly and then stabilizes, exhibiting an optimal penalty coefficient range (approximately 0.4–0.6). This provides a quantitative basis for regulators or grid companies to formulate reasonable congestion management policies: too low a penalty renders the constraint ineffective, while too high may excessively suppress economic activity.

Figure 12.

Impact of congestion penalty coefficient on system economics.

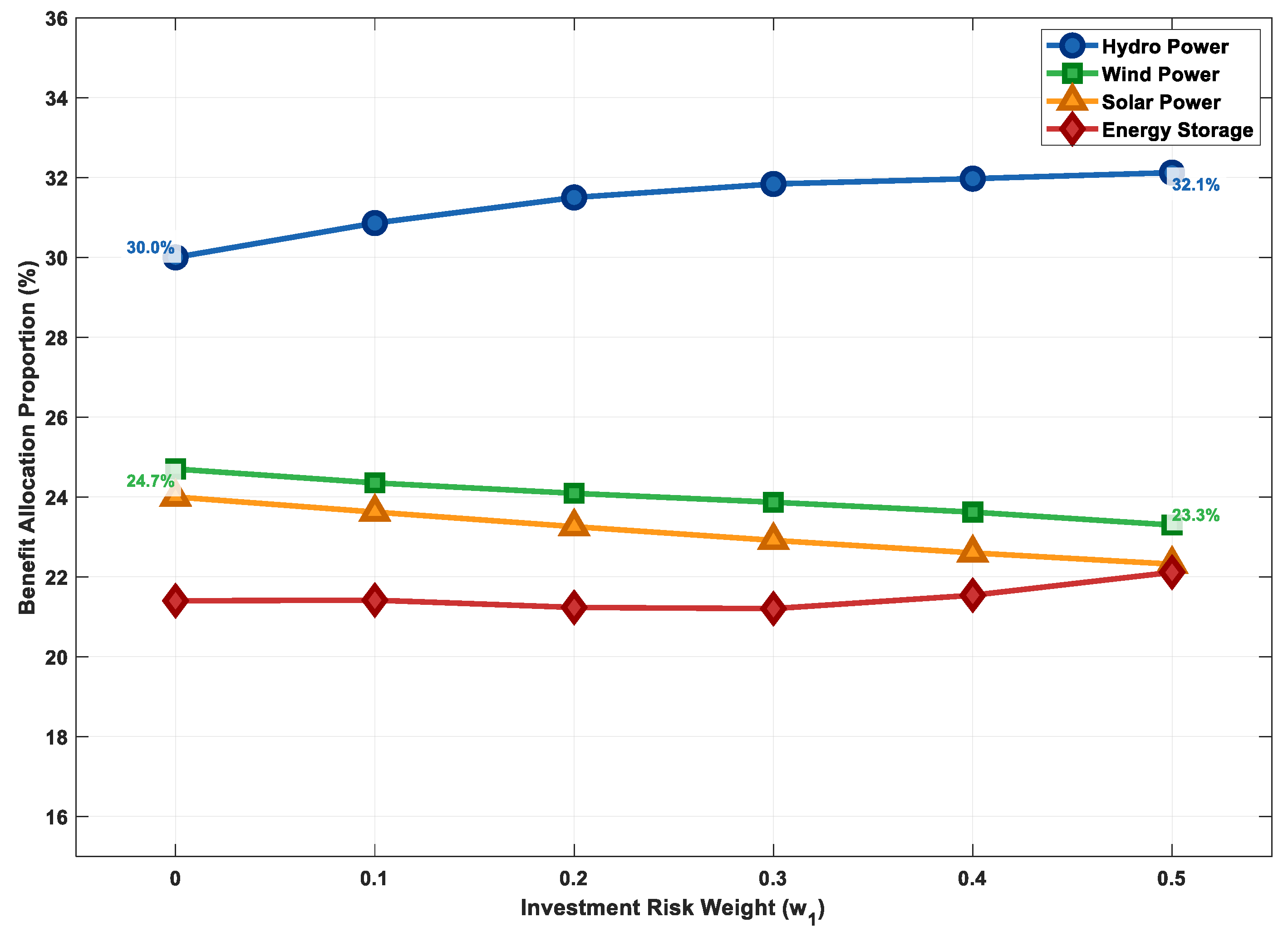

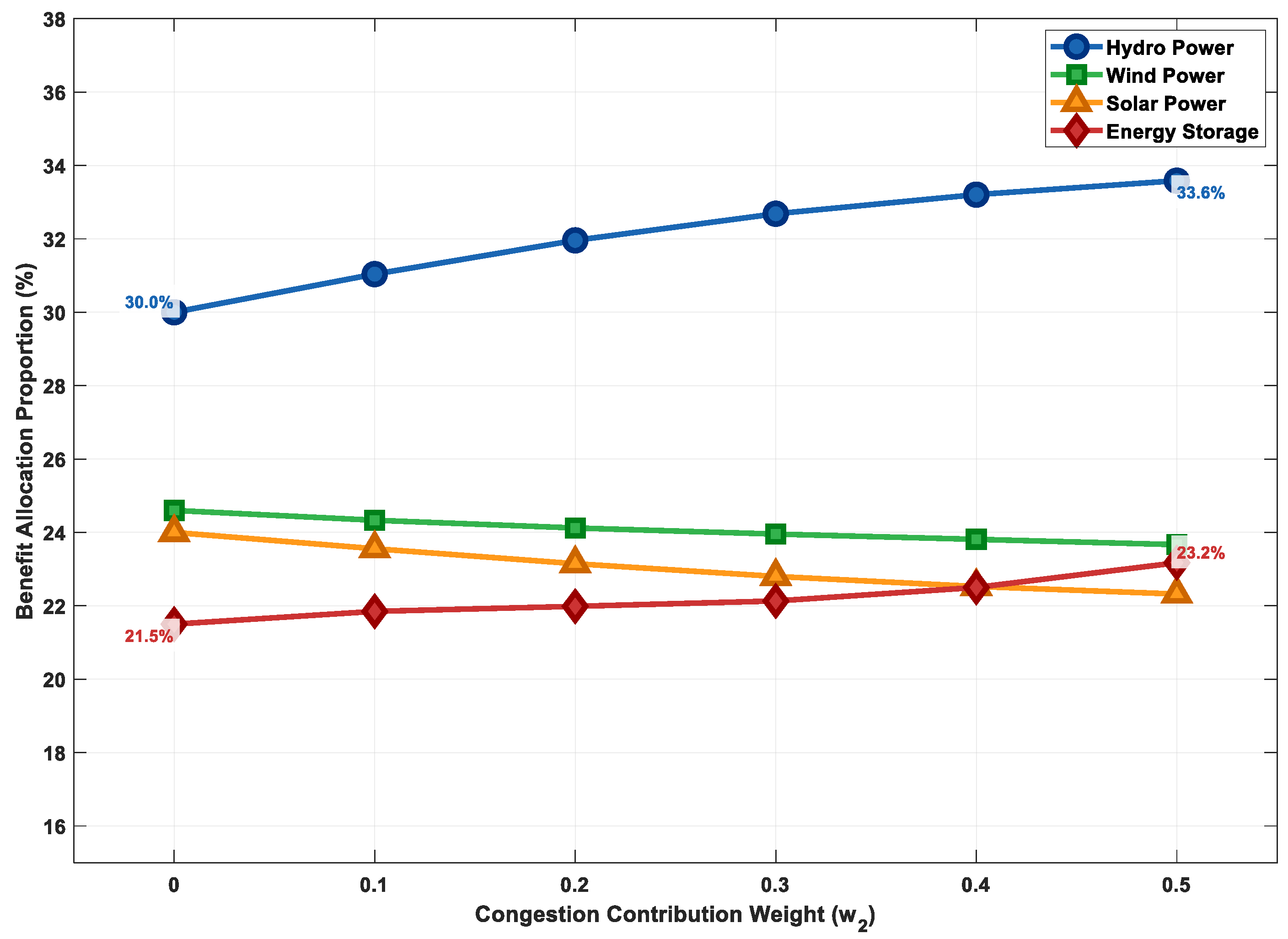

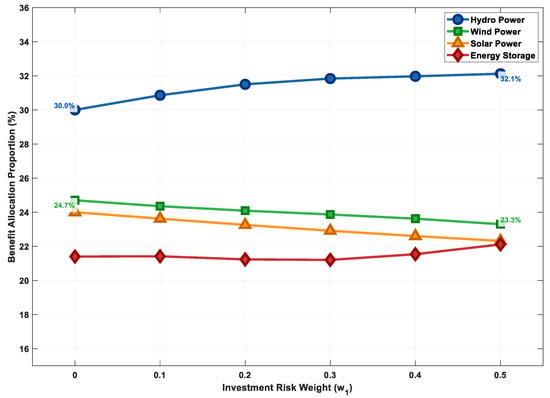

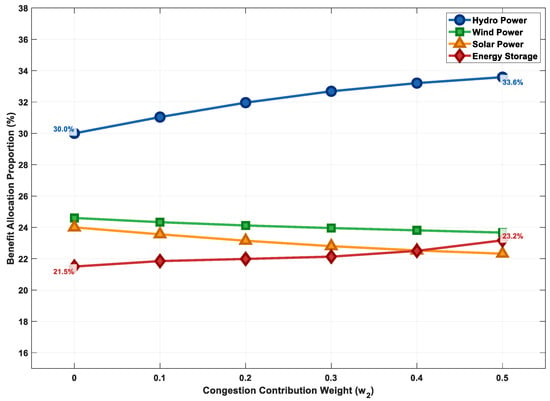

Figure 13 and Figure 14 analyze the sensitivity of the weight coefficients in the improved Shapley value method. Figure 13 shows that as the investment risk weight () increases, the revenue share of higher-risk wind power decreases, while the share of relatively lower-risk hydropower increases, reflecting reasonable compensation and incentive for high-risk investments. Figure 14 indicates that the congestion mitigation contribution weight () has a significant positive impact on the revenues of hydropower and energy storage, which aligns highly with their actual functional positioning in the system. These two figures jointly demonstrate that the constructed benefit distribution model has good parameter robustness and logical consistency. Decision-makers can adjust the weights according to specific policy directions or project characteristics to achieve different distribution objectives.

Figure 13.

Impact of investment risk weight on benefit allocation.

Figure 14.

Impact of congestion contribution weight on benefit allocation.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the critical challenge of coordinating multiple investors in an integrated hydro-wind-solar-storage (HWSS) base under grid congestion. A cooperative game-theoretic framework, integrating a bi-level optimization model and an improved benefit allocation scheme, is proposed to achieve synergistic capacity allocation and fair profit distribution.

The principal findings and contributions of this research are summarized as follows:

- Synergistic Value of Cooperation under Congestion: The proposed cooperative game model successfully internalizes grid congestion costs into the planning decision-making process. Case study results demonstrate that cooperation, when explicitly considering transmission constraints, guides the system from individual rationality (Nash equilibrium) to collective rationality (Pareto improvement). This approach yields a 20.1% increase in total system revenue compared to the non-cooperative scenario, while simultaneously achieving dramatic reductions in congestion costs (by 86.2%) and wind/solar curtailment rates (by 79.3%). This underscores that cooperation is not merely beneficial in theory but is essential for practical, economically optimal, and physically feasible planning under grid constraints.

- Enhanced Fairness and Stability via Improved Allocation: The classical Shapley value method is refined by introducing a comprehensive correction factor that accounts for investment risk, congestion mitigation contribution, and installed capacity. This improvement ensures a fairer distribution of coalition surplus by quantitatively recognizing the heterogeneous value of each participant. The allocation results justly increase the profit shares for flexible resources—hydropower (from 28.5% to 32.1%) and energy storage (maintained at a significant 20.4%)—which are crucial for peak shaving and alleviating transmission bottlenecks. Stability analysis confirms that the improved allocation satisfies individual rationality for all participants, thereby securing the long-term viability of the grand coalition.

- Practical Insights from Sensitivity Analysis: The sensitivity analysis provides valuable insights for system planners and policymakers. It identifies an optimal range for the congestion penalty coefficient (0.4–0.6), offering a quantitative basis for effective congestion management. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that the allocation model is robust and adaptable, allowing decision-makers to adjust the weight coefficients based on specific policy priorities, such as emphasizing investment risk mitigation or rewarding grid congestion relief.

In conclusion, this research provides a theoretically sound and practically viable decision-making tool for the collaborative planning of HWSS bases with diversified investment entities, effectively bridging the gap between physical grid constraints and economic incentives.

Future work will consider the uncertainty of parameters and focus on incorporating long-term uncertainties associated with renewable energy forecasting and market prices using stochastic programming or robust optimization to enhance the robustness of the configuration scheme. Furthermore, exploring a master-slave game structure that includes the grid company or government as a leader will be undertaken to investigate policy-guided coalition formation mechanisms.

Author Contributions

L.C.: conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft; J.Q.: funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing; D.T., X.M. and H.Z.: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52269020).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, W.; Liu, M.; Zuo, C.; Wang, K. Massive Multi-Source Joint Outbound and Benefit Distribution Model Based on Cooperative Game. Energies 2023, 16, 6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, P.; Wu, D. Analytical optimization and sensitivity analysis of installed capacity allocation for hydro-wind-solar complementary system. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 54, 978–986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Sheng, B. Research on capacity allocation of wind and solar power in hydro-wind-solar-storage complementary power generation system. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2023, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhong, S. A review on capacity allocation optimization of wind-solar-storage microgrid. Electr. Technol. Econ. 2022, 4, 23–25, +29. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y. Hierarchical capacity configuration of wind-solar-storage virtual power plant considering reliability and flexibility. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2022, 50, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, P.; Li, C.; Wu, S. Optimal Scheduling of a Cascade Hydropower Energy Storage System for Solar and Wind Energy Accommodation. Energies 2024, 17, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeiras, F.; Gomes, Á.; Gomes, M.; Coelho, P. Application and Challenges of Coalitional Game Theory in Power Systems for Sustainable Energy Trading Communities. Energies 2023, 16, 8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Liao, S. Collaborative optimization of integrated electricity and natural gas energy system considering renewable energy uncertainty. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, L.; Wu, N. An optimal scheduling strategy for electricity-thermal synergy and complementarity among multi-microgrid based on cooperative games. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Lei, R.; Ouyang, S.; Huang, W. Capacity Optimization Allocation of Multi-Energy-Coupled Integrated Energy System Based on Energy Storage Priority Strategy. Energies 2024, 17, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Yan, S. Two-Stage Collaborative Power Optimization for Off-Grid Wind-Solar Hydrogen Production Systems Considering Reserved Energy of Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Huang, W.; Zhai, S.; Lin, G.; He, X.; Fang, G.; Su, S.; Wang, D.; Ai, Q. Collaborative Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Clusters and Distribution Networks Based on Cooperative Game Theory in the Electric-Carbon Coupling Market. Energies 2025, 18, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, S.; Xie, S.; Hu, B.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Z. Capacity allocation of wind-photovoltaic-electric hydrogen microgrid based on cooperative game. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Z.; Niu, J.; Zuoke, S.; Yang, C. Cooperative game of multi-electricity-gas interconnected system considering renewable energy consumption and low-carbon emission. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2023, 44, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, K.; Meng, K.; Meng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lü, Y. Economic Optimization of Hybrid Energy Storage Capacity for Wind Power Based on Coordinated SGMD and PSO. Energies 2025, 18, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, S.; Fang, Z. Optimal configuration and cost allocation of shared energy storage for multi-microgrid. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, J. Shared Energy Storage Capacity Configuration of a Distribution Network System with Multiple Microgrids Based on a Stackelberg Game. Energies 2024, 17, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Optimal operation strategy of shared energy storage for distributed photovoltaic community based on master-slave game and improved Shapley value. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 2252–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Lü, H.; Peng, X.; Wang, B.; Zhu, J. Low-carbon cooperative optimization strategy for multi-park integrated energy service providers considering dynamic pricing and carbon trading. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Pei, W.; Xiao, H. Cooperative operation method of wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen multi-agent energy system based on Nash bargaining theory. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 25–39, +395. [Google Scholar]

- Xingjin, Z.; Pietro, C.E.; Xiaojian, B.; Egusquiza, M.; Xu, B.; Wang, C.; Guo, H.; Chen, D.; Egusquiza, E. Capacity configuration of a hydro-wind-solar-storage bundling system with transmission constraints of the receiving-end power grid and its techno-economic evaluation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116177. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Liang, D.; Li, Y.; Mojing, S. Research on two-layer low-carbon scheduling strategy considering cooperative game for multi-microgrid and distribution network with electricity-carbon coupling. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2025, 46, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Luo, Y.; Wu, T. Optimization of electro-hydrogen energy storage configuration in off-grid wind-solar-hydro complementary systems. Energy 2025, 332, 137221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Mu, L. Multi-agent low-carbon optimal dispatch of regional integrated energy system based on mixed game theory. Energy 2024, 295, 130953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Li, F.; Zhang, G. Congestion management strategy for active distribution network considering wind power uncertainty. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 10345–10354. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ai, X. Congestion management of active distribution network based on master-slave game. Mod. Electr. Power 2022, 39, 649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Jia, Z.; Dang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. Economic low-carbon dispatch of multi-energy complementary microgrid considering electricity-carbon-green certificate joint trading. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2025, 46, 717–726. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).