Abstract

Remote islands face persistent challenges in achieving secure, sustainable and affordable energy supply due to their geographic isolation, fragile ecosystems and dependence on imported fossil fuels. Hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES)—typically combining photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines and battery energy storage systems (BESS)—have emerged as the dominant off-grid solution, demonstrating their potential to reduce fossil fuel dependence and greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, empirical case studies from Zanzibar, Thailand, Malaysia, the Galápagos, the Azores and Greece confirm that current systems remain transitional, relying on oversized storage and fossil backup during low-resource periods. Comparative analysis highlights both technical advances and persistent limitations, including seasonal variability, socio-economic barriers and governance gaps. Future directions for PV—wind-based (non-dispatchable) island microgrids point toward long-term hydrogen storage, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven predictive energy management and sector coupling—alongside participatory planning frameworks that enhance social acceptance and community ownership. By synthesizing technical, economic and social perspectives, this study provides a roadmap for advancing resilient, autonomous and socially embedded hybrid off-grid systems for remote islands.

1. Introduction

Remote islands around the world face unique and persistent challenges in achieving secure, sustainable and affordable energy supply. Their geographic isolation, small-scale economies and often fragile ecosystems make them heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels, which exposes them to high energy costs, supply disruptions and carbon-intensive electricity generation [1]. At the same time, these islands often possess abundant renewable energy resources, primarily solar and wind, which could be harnessed to achieve energy autonomy and contribute to broader decarbonization goals under the European Green Deal and the UN Sustainable Development Goals [2]. The global drive toward 100% renewable energy systems has placed small islands at the forefront of experimentation, yet their energy transitions remain technologically, economically and socially complex [3].

Over the past decade, HRES—typically combining PV and wind generation with BESS—have emerged as the dominant technological approach for off-grid islands [4]. Such systems can reduce fossil fuel dependence, lower greenhouse gas emissions and improve local energy security [5]. However, despite remarkable progress, existing deployments often rely on basic operational strategies such as load-following and curtailment, which limit their efficiency and resilience during prolonged periods of low renewable output [6]. Seasonal variability in solar and wind resources further constrains their ability to meet continuous demand, especially during peak tourism seasons, while battery-based storage alone—even when combined with short-term strategies—struggles to provide reliable multi-week or seasonal buffering, as shown in long-term operation studies of isolated microgrids with hybrid seasonal-battery storage [7].

In addition to technical constraints, island microgrids must navigate socio-political and institutional challenges. The social acceptance of renewable energy systems in island and island-like contexts—whether in isolated (islanded) microgrids or grid-connected island systems—depends on public trust, perceptions of fairness and the extent of community involvement in planning processes [8]. Local resistance, often rooted in perceived procedural injustice, aesthetic concerns, or misinformation, can delay or derail otherwise technically viable projects [9]. Furthermore, current regulatory and financial frameworks in many regions are not well adapted to decentralized, community-driven energy projects, limiting the replication and scaling of successful models [10].

Beyond these socio-institutional barriers, persistent technical limitations—particularly in the area of energy storage—continue to hinder the full transition toward renewable autonomy. Reliable and cost-effective energy storage remains one of the most critical enablers of high renewable penetration on islands. While batteries currently serve as the backbone of short-term balancing, their limited capacity and high cost restrict their ability to address multi-day or seasonal gaps between generation and demand. Therefore, the development of complementary long-term storage technologies has become essential to ensure round-the-clock energy security and to reduce reliance on fossil backup. While batteries remain the backbone of short-term balancing, other short-duration flexibility options (e.g., flywheels) can also support fast power-quality and frequency-control needs in islanded systems. Against this backdrop, the integration of green hydrogen as a complementary long-term storage solution is increasingly discussed as a pathway toward resilient and self-sufficient energy systems for remote islands [11]. By converting surplus renewable electricity into hydrogen via electrolysis and storing it for later use in fuel cells, islands could overcome the inherent temporal mismatch between supply and demand. Such seasonal storage could substantially enhance the reliability and autonomy of hybrid systems, particularly when combined with advanced battery storage for short-term balancing. Nevertheless, hydrogen technologies remain at early stages for small-scale island applications and their economic viability, safety protocols and infrastructure requirements demand further research and innovation [12].

Another promising direction lies in the application of artificial intelligence (AI)-based energy management and predictive optimization tools. Beyond real-time operation, a core design challenge in island and island-like systems (including grid-connected island applications) is the joint selection and sizing of complementary resources (e.g., PV–wind portfolios) together with storage (BESS, hydrogen) under correlated resource variability and uncertain demand.

AI methods—ranging from machine-learning surrogates to reinforcement learning and bi-level co-optimization—help quantify spatiotemporal complementarity, solve multi-objective techno-economic sizing and enforce reliability constraints at minimum cost [13,14,15].

These approaches can forecast load and renewable output, schedule dispatch from storage assets and minimize curtailment, thereby improving both reliability and cost-effectiveness [16]. Smart microgrid architectures integrating sector coupling—linking electricity with heating, cooling and mobility—could also enhance resource efficiency and system flexibility in the constrained contexts of small islands [17,18]. Such innovations could pave the way for the next generation of hybrid off-grid systems that are not only technically robust but also socially accepted, economically viable and environmentally sustainable.

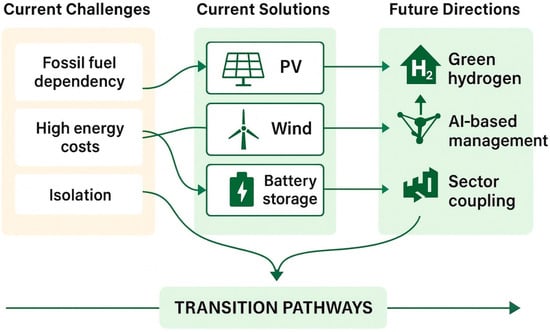

This manuscript is written as a Perspective (targeted narrative review) that synthesizes recent technical and socio-institutional evidence on hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) for isolated and remote islands. The discussion is motivated in part by prior techno-economic work on autonomous island systems, including Nisyros [19,20] and is expanded here to a broader international context. Specifically, we summarize prevailing HRES architectures and their benefits and limitations, synthesize insights from published real-world island case studies and discuss future directions including green hydrogen for long-term storage, AI-enabled energy management and participatory planning approaches. To enhance transparency, the synthesis is informed by a targeted literature scan (primarily 2022–2025) using keyword combinations such as “island microgrids”, “hybrid renewable energy systems”, “hydrogen seasonal storage”, “AI/optimization energy management” and “energy communities/social acceptance”, complemented by backward and forward citation screening. Accordingly, we do not claim a systematic-review protocol; rather, we aim to provide a structured synthesis and a research-and-deployment agenda for accelerating the transition to more resilient hybrid island energy systems. As illustrated in Figure 1, the transition from fossil-fuel-dependent island microgrids to future hybrid systems requires coordinated progress on technical, economic and social barriers alongside the integration of emerging options such as hydrogen storage, AI-enabled control and participatory planning.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram illustrating transition pathways linking current challenges, existing solutions and future directions of hybrid renewable energy systems on remote islands, including sector coupling and potential energy-cascading pathways (source: authors’ elaboration).

The remainder of this Perspective is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology (literature scan, case selection and data extraction) and summarizes baseline PV–wind–BESS architectures and operating logic. Section 3 presents the selected island cases and reported indicators, Section 4 discusses cross-cutting insights and future directions and Section 5 addresses social/governance enablers and concludes with key takeaways.

2. Current Architectures of Hybrid Off-Grid Systems

2.1. Methodology: Literature Scanning, Case Selection and Data Extraction

This Perspective is based on a targeted literature scan of island and remote microgrid studies, using scholarly databases and publisher platforms (e.g., Google Scholar and major journal databases) to identify peer-reviewed articles and traceable technical reports. Search strings combined keywords such as island microgrid, diesel hybrid, PV–wind–battery/BESS, renewable penetration/share, LCOE/COE, NPC, hydrogen storage, electrolyser/fuel cell, energy management system (EMS), AI/forecasting and sector coupling (including EV/V2G). The scan focused primarily on 2022–2025, emphasizing recent evidence and implementations or implementation-oriented simulations. Studies were included when they: (i) examined island or island-like isolated power systems; and (ii) reported at least one traceable technical or techno-economic indicator (e.g., capacities, renewable share/penetration, LCOE/COE, NPC, curtailment, diesel runtime/starts, or reliability proxies). Six island cases were then purposively selected to represent diverse geographies and system maturities (diesel-hybrid, renewable-dominant hybrids and control-focused microgrid studies), while ensuring that each case is supported by at least one primary source with extractable indicators. For each case, we extracted (where reported) generation and storage capacities, renewable penetration/share and cost indicators (LCOE/COE/NPC) and explicitly marked metrics as ‘not reported’ when absent. No new empirical dataset was created or collected in this study; all quantitative indicators are drawn from the cited primary sources.

The number of cases (six) was chosen to strike a practical methodological balance between diversity and interpretability: it is sufficient to capture cross-regional variation in technology pathways and governance contexts, while remaining small enough to allow a consistent, in-depth qualitative synthesis of reported technical and techno-economic indicators. This purposive sampling therefore prioritizes traceability and comparability of evidence over statistical representativeness.

2.2. Baseline Architectures and Operating Logic

HRES have emerged as the predominant technological configuration for powering remote islands over the past decade. These systems typically combine PV panels and wind turbines with BESS to provide a stable and reliable electricity supply with reduced reliance on mainland imports. Their modular nature, ability to scale according to local demand and potential to drastically reduce fuel imports have made them the primary strategy for decarbonizing remote and island (-like) communities [21]. For instance, recent work demonstrates that properly optimized PV–wind–battery microgrids can reach high renewable shares with competitive levelized costs compared to diesel-only baselines, both in general remote contexts [22] and in real island settings such as Tumbatu Island in Zanzibar [23].

The prevailing operational paradigm of these systems is based on simple load-following logic. Renewable generation is prioritized to serve instantaneous demand and any surplus energy is either curtailed or stored in batteries for later use. Diesel gensets or other fossil backup units are typically kept on standby to cover residual demand when renewable output is low [6]. While this approach is robust and straightforward to implement, it has inherent limitations: it does not account for predictive variations in demand or renewable availability, leading to frequent curtailment during peak production and supply shortages during prolonged low-resource periods. These effects are amplified on tourism-driven islands where demand profiles vary seasonally, often peaking during periods of low renewable output [24].

Battery storage plays a critical role in these hybrid systems by smoothing short-term fluctuations, yet its relatively high cost, limited energy density and degradation constraints prevent it from providing multi-day or seasonal storage. Consequently, most current island microgrids must oversize their battery capacity—often by a factor of ten or more relative to daily load—to reach high renewable shares [25]. This oversizing increases upfront investment costs, requires substantial land area and contributes to higher embodied emissions from battery production. For example, a recent study examined an islanded hybrid microgrid on Pulau Perhentian (Malaysia) [26] and showed that even with significant PV–wind–BESS integration, system performance during low-resource periods required reliance on backup generation unless advanced optimization and control strategies were applied.

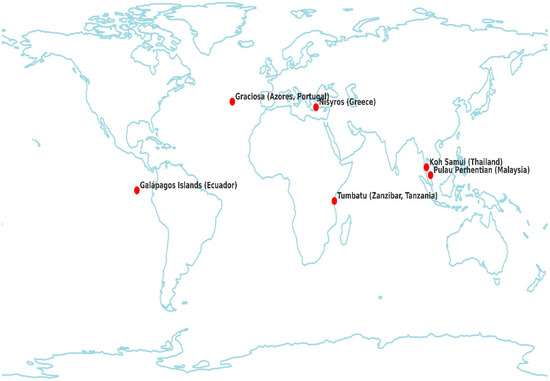

Several other real-world implementations underline the operational and economic constraints of current hybrid architectures. On the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador, ref. [27] demonstrated that while a transition to 100% renewable supply is technically feasible, it requires substantial storage capacity and major grid upgrades, with system costs and renewable curtailment strongly dependent on dispatch strategies and storage sizing. Similarly, on Graciosa Island in the Azores, ref. [28] analyzed expansion scenarios for the island’s hybrid energy system, highlighting that although renewable penetration levels have significantly increased, diesel backup remains necessary to ensure stability during periods of low wind and solar availability. On Nisyros Island in Greece, ref. [20] developed an off-grid techno-economic model integrating PV, wind and battery storage, showing that a fully autonomous configuration could meet local demand at competitive costs while reducing lifecycle emissions by over 80%, highlighting the potential of hybrid systems even in resource-constrained island settings. Figure 2 provides a global overview of representative island case studies analyzed in the case study section, highlighting the diversity of contexts in which current hybrid off-grid systems have been deployed.

Figure 2.

Global map of representative island case studies with existing hybrid off-grid renewable energy systems (source: authors’ elaboration).

3. Evidence from Published Island Case Studies (Narrative Synthesis of Real-World Reports)

This section provides a narrative synthesis of evidence reported in peer-reviewed articles, technical reports and publicly available project documentation for six island systems. The cases were selected to represent diverse geographies and maturity levels of island power systems (diesel-hybrid, renewable-dominant hybrids and microgrid control-focused studies), while ensuring that at least one primary source provides traceable technical and/or techno-economic indicators. For each case, we extracted (where reported) generation and storage capacities, renewable penetration/share and cost indicators (e.g., COE/LCOE, NPC) and we explicitly note when a metric is not provided in the underlying source.

While Section 2 provided an overview of current hybrid off-grid architectures and their operational characteristics, this section shifts the focus toward reported real-world evidence from selected island case studies. Such evidence helps identify gaps between expected and reported performance and reveals context-specific technical, economic and socio-institutional barriers that are difficult to capture in generalized modeling frameworks alone. Remote islands serve as natural laboratories for energy transition: their small scale, resource endowments and isolation provide conditions where renewable energy integration can be observed in concentrated form. At the same time, these environments expose the full range of challenges—seasonal variability, storage limitations, fluctuating demand, regulatory misalignment and issues of social acceptance. Thus, reviewing the operational outcomes of existing island systems provides both cautionary lessons and forward-looking strategies for the global diffusion of HRES.

In what follows, six geographically diverse islands are analyzed: Tumbatu Island, Zanzibar (East Africa), Koh Samui and Pulau Perhentian (Southeast Asia), the Galápagos Islands (Latin America), Graciosa (Europe, Azores) and Nisyros (Europe, Aegean Sea). Collectively, these cases depict an evolution from diesel-dominated supply and early diesel–PV hybrid configurations toward more sustainable PV–wind–BESS island microgrids, while acknowledging that fossil backup often remains necessary during low-resource periods and peak-demand events. These case studies were selected to provide cross-regional diversity while maintaining sufficient depth for consistent qualitative comparison across technical performance, governance constraints and social acceptance factors.

Table 1 provides a concise overview of the six islands and their basic contextual descriptors (e.g., location, grid status and indicative demand/population, where reported), to support transparent cross-case comparison.

Table 1.

Overview of the selected island cases (geography, grid status and context descriptors).

Population size and detailed demand statistics are not consistently reported across the primary sources used for the six cases; therefore, Table 1 lists these items as ‘Not reported’ where the underlying paper does not provide traceable values, to avoid introducing non-source-based estimates. Building on this overview, Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6 discuss each island case in turn and summarize the reported technical and techno-economic indicators.

The choice of six islands reflects a deliberate methodological balance: a sample large enough to capture cross-regional diversity, yet sufficiently limited to allow for in-depth qualitative comparison of technological performance, institutional mechanisms and social acceptance patterns. This mixed-scope approach enables both analytical coherence and cross-contextual insights. Together, these cases illustrate a wide spectrum of system designs, scales and governance contexts. Each case study highlights not only the technical performance of hybrid PV–wind–battery systems, but also the broader economic and social conditions shaping their adoption. Importantly, differences in regulatory and institutional settings are treated here not only as barriers but also as potential enablers, since less prescriptive frameworks can sometimes facilitate piloting and experimentation with new technical and governance models.

3.1. Case Study: Tumbatu Island, Zanzibar (East Africa)

On Tumbatu Island in Zanzibar, ref. [23] analyzed the optimal design of a grid-connected hybrid PV–wind–battery system using HOMER Pro (version 3.14.2; HOMER Energy by UL Solutions, Boulder, CO, USA). Their findings demonstrated that renewable energy penetration could be maximized through careful sizing of PV and wind resources combined with storage, resulting in a system capable of meeting local demand at significantly lower levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) compared to diesel-only generation. It should be noted, however, that the HOMER optimization process is primarily cost-driven and assumes full load coverage 24/7, which can lead to oversizing of generation and storage components, especially in small island contexts where load profiles are highly variable. This limitation must therefore be considered when interpreting the economic and technical feasibility outcomes.

The study also highlighted the role of grid connection in enhancing flexibility and resilience, enabling surplus renewable energy to be exported while maintaining system stability. Importantly, the authors noted that local socioeconomic conditions, including limited capital investment capacity and policy support, remain critical barriers to scaling such systems in the broader Tanzanian context. Although Tumbatu is grid-connected rather than fully off-grid, we include it here as a boundary case because many of the techno-economic design questions and socio-institutional constraints it illustrates are shared with small island systems that rely primarily on local hybrid generation.

This case underlines two key lessons for remote islands:

- System optimization and mixed resource integration can significantly improve cost-effectiveness compared to fossil-based baselines.

- Institutional and financial constraints often determine the pace of renewable transition as much as technical feasibility, emphasizing the importance of supportive policy frameworks and financing mechanisms.

3.2. Case Study: Koh Samui, Thailand (Southeast Asia)

On Koh Samui Island in Southern Thailand, ref. [24] examined the performance of a hybrid solar–wind–diesel–BESS system designed to address the island’s rapidly growing electricity demand, driven largely by seasonal tourism. The study showed that although high renewable fractions could be achieved under average conditions, the system faced significant challenges during peak tourist seasons when demand surged while solar and wind resources were insufficient. As a result, reliance on diesel backup remained essential to ensure supply adequacy.

One of the most critical findings was the mismatch between peak demand and renewable availability, which led to frequent curtailment of renewable energy during low-demand periods and shortages during peak-load events. This highlighted the limitations of simple load-following strategies in contexts where demand is highly variable and seasonal.

From this case, two important lessons emerge:

- Tourism-driven demand variability requires advanced forecasting and predictive energy management to optimize resource use.

- Although the original study did not examine hydrogen storage, the incorporation of long-term storage technologies (such as green hydrogen) or demand-side flexibility could, in principle, mitigate seasonal imbalances and reduce diesel reliance in similar island contexts.

3.3. Case Study: Pulau Perhentian, Malaysia (Southeast Asia)

This case study [26] investigated the optimization and control of a solar–wind islanded hybrid microgrid on Pulau Perhentian, Malaysia. The study applied heuristic and deterministic optimization algorithms along with fuzzy logic control to evaluate how advanced dispatch strategies could improve system performance compared to conventional load-following approaches.

The findings revealed that while the PV–wind–BESS system could provide a high renewable share under favorable conditions, prolonged low-resource periods (e.g., during extended cloudy and windless days) forced reliance on fossil backup unless advanced optimization was applied. Importantly, the research demonstrated that oversizing battery storage alone was insufficient to guarantee reliability without substantially raising costs and embodied emissions.

The case underlined two broader insights:

- Advanced control strategies (e.g., fuzzy logic, predictive optimization) can significantly reduce curtailment and improve system resilience.

- Without such strategies, even large-scale storage oversizing cannot ensure autonomy, reinforcing the need for next-generation architectures that integrate smart energy management.

3.4. Case Study: Galápagos Islands, Ecuador (Latin America)

This case study [27] analyzed the transition pathways of the Galápagos Islands toward a 100% renewable power supply. Using long-term and short-term operational models, the study explored the optimal sizing of storage technologies and grid upgrades under different dispatch strategies.

The results demonstrated that while achieving 100% renewable penetration is technically feasible, it requires substantial investments in storage capacity (both batteries and complementary technologies) and major grid reinforcements. Without these, the islands risk frequent curtailment of renewable energy during surplus periods and dependence on fossil backup during low-resource events.

A key lesson from the Galápagos case is that system costs and renewable curtailment are highly sensitive to storage sizing and dispatch strategies. Policy support and carefully staged infrastructure upgrades are therefore essential to avoid economic burdens while maintaining energy security.

3.5. Case Study: Graciosa Island, Azores (Europe)

This case study [28] investigated expansion scenarios for the hybrid energy system of Graciosa Island in the Azores, which integrates wind, solar and battery storage alongside fossil backup. The analysis covered technical, economic and operational perspectives, focusing on pathways to reduce fossil dependency while maintaining grid stability.

Reported operational evidence and simulations indicate that renewable penetration has significantly increased in recent years, yet diesel backup remains indispensable to ensure stability during prolonged low-resource periods. This underscores the challenge of resource intermittency in mid-Atlantic climates, where variability in wind and solar availability directly impacts system reliability.

The Graciosa case highlights the importance of incremental expansion planning, showing that even with substantial renewable shares, hybrid microgrids often require transitional reliance on fossil backup. It also illustrates how careful policy support, investment in storage and advanced dispatch optimization are essential for pushing systems closer to full autonomy. From this case, two important lessons emerge:

- Even with high renewable penetration, prolonged low-resource periods can make firm backup capacity indispensable unless longer-duration storage and more advanced dispatch strategies are deployed.

- Incremental expansion planning—supported by targeted policy measures and investment in storage and optimization—remains a pragmatic pathway to progressively reduce diesel reliance while maintaining stability.

3.6. Case Study: Nisyros Island, Aegean Sea (Greece)

This case study [20] developed an off-grid techno-economic model for Nisyros Island, a small non-interconnected island in the Aegean Sea. The system design integrates PV, wind turbines and battery storage, aiming for a fully autonomous energy configuration that minimizes fossil fuel dependence.

The analysis showed that a properly optimized hybrid PV–wind–BESS system could meet local demand at competitive costs, while simultaneously reducing lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions by more than 80% compared to diesel-based baselines. Unlike other island case studies where fossil backup remains necessary, the modeling for Nisyros demonstrated the technical and economic feasibility of complete autonomy under specific resource and demand conditions. Nevertheless, the scenario for Nisyros also entails several limitations. The analysis assumes stable long-term resource availability and simplified operational control, which may not fully capture short-term intermittency or equipment degradation. Moreover, the high share of variable renewables implies increased dependency on accurate forecasting, advanced storage management and preventive maintenance strategies to ensure reliability. Economic uncertainties—such as fluctuating battery costs, replacement intervals and financing conditions—could also affect overall system viability.

A key insight from this case is that even resource-constrained islands can achieve high resilience and sustainability if hybrid systems are carefully designed with context-specific optimization. The findings also stress the need for robust participatory planning and supportive policy frameworks to translate technical potential into real-world deployment. This case underlines two key lessons for remote islands:

- Fully autonomous PV–wind–BESS configurations can be techno-economically feasible under favorable resource–demand conditions, but results are sensitive to operational assumptions (forecasting, component aging and maintenance).

- Translating modeled autonomy into robust real-world deployment requires not only technical design optimization but also participatory planning and supportive policy/financing frameworks to secure durable acceptance and operational reliability.

Across the six cases, the reported evidence converges on a common operational pattern: high renewable shares are feasible, yet reliability during prolonged low-resource periods and peak-demand episodes often still requires dispatchable backup or additional flexibility (e.g., Koh Samui, Pulau Perhentian and Graciosa) [24,26,28]. A second recurring finding is the strong sensitivity of techno-economic outcomes to storage sizing and dispatch strategy—oversizing storage can improve autonomy but quickly raises costs, while simple load-following operation increases curtailment and can shift shortages to peak periods [24,26,27]. The Galápagos pathway further indicates that reaching very high renewable penetration at system scale requires coordinated investments in both storage and network upgrades to manage curtailment and maintain security of supply [27]. In contrast, fully autonomous configurations may be achievable under specific resource–demand conditions (as in Nisyros), but their robustness depends on forecasting, maintenance and lifecycle cost assumptions [19,20].

Taken together, the six cases highlight that today’s hybrid island systems are effective but transitional, with performance shaped by intermittency, storage/dispatch choices and demand seasonality. Thes qualitative cross-case patterns are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison between current and future hybrid off-grid energy systems for remote islands.

Overall, the current generation of hybrid microgrids for remote islands can be characterized as effective but transitional. They demonstrate that high renewable shares are feasible in isolated environments, yet they rely on heavy storage oversizing, simplified dispatch strategies and fossil backup to ensure supply security. As summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 2, current hybrid systems on remote islands are primarily based on PV–wind generation with battery storage and simple load-following strategies, whereas future systems are expected to incorporate long-term hydrogen storage, AI-enabled energy management and sector coupling. These constraints highlight the necessity of transitioning to next-generation hybrid systems incorporating predictive energy management, demand-side flexibility, sector coupling and long-term storage—directions that are further discussed in Section 4, “Future Directions of Hybrid Off-Grid Systems for Remote Islands.”

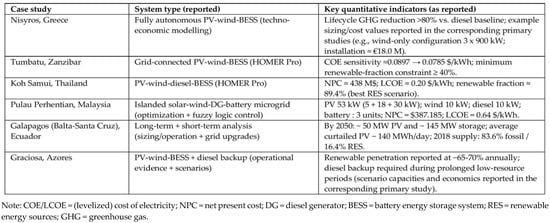

To complement the qualitative comparison in Table 2, Table 3 summarizes the key quantitative indicators reported in the six primary island case studies (where available), enabling transparent cross-case comparison and the corresponding Figure 3 summarizing reported quantitative indicators.

Table 3.

Quantitative indicators reported in the six published island case studies (as available in primary sources).

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of the key quantitative metrics reported in the six island case studies (generation/storage sizing, renewable share/penetration and cost indicators where available) based on data from [19,20,23,24,26,27,28].

4. Future Directions of Hybrid Off-Grid Systems for Remote Islands

While current HRES deployed on remote islands have demonstrated significant potential in reducing fossil fuel dependency, they remain transitional solutions that rely on heavy storage oversizing and simplified operational strategies. To move toward resilient, autonomous and socially accepted energy systems, next-generation architectures must incorporate advanced storage technologies, intelligent energy management and integrated sectoral approaches. To avoid an overly idealized framing, we explicitly discuss feasibility constraints (scale, costs, logistics, safety and institutional capacity) and summarize implementation barriers and decision-relevant metrics for islands.

The aim is not to prescribe a single “best” solution, but to outline least-regret pathways and boundary conditions under which hydrogen, AI-enabled control and sector coupling become technically and socio-economically justified.

This section synthesizes these widely discussed pathways through the lens of remote-island constraints and derives a practical agenda of research and deployment priorities (Section 4.5), grounded in the cross-case evidence summarized in Section 3. Rather than proposing new technological directions, we consolidate (i) recurring island-specific barriers (seasonality, logistics, governance capacity), (ii) commonly reported performance bottlenecks (curtailment, storage oversizing, diesel dependence) and (iii) corresponding design and policy levers into a coherent, island-focused roadmap.

4.1. Green Hydrogen as Seasonal Storage

One of the most critical limitations of current island microgrids is their inability to provide reliable multi-week or seasonal energy buffering. Batteries, while essential for short-term balancing, are cost-prohibitive and environmentally burdensome when scaled to cover extended periods of low renewable availability. In this context, green hydrogen has emerged as a promising long-term storage solution. By converting surplus renewable electricity into hydrogen through electrolysis, islands can store large amounts of energy in chemical form and later reconvert it into electricity using fuel cells or gas turbines.

Several pilot projects have demonstrated the feasibility of hydrogen integration in island contexts. For example, in a small island case in the Mediterranean, green hydrogen seasonal storage was used to complement batteries by absorbing surplus solar and wind power and supporting supply during low-resource periods [29]. In Northern Europe, remote island systems combining hydrogen and battery storage have been explored to enhance renewable electrification and reduce curtailment [30]. Additionally, integrated battery–hydrogen systems in campus-scale testbeds show that such hybrid storage can improve grid flexibility and utilization [31]. This capability reduces reliance on diesel generators and increases renewable penetration in hybrid systems. However, multiple barriers remain. First, the capital cost of electrolysers and fuel cells is still high, particularly in small-scale island applications where economies of scale are limited. Second, hydrogen infrastructure requires strict safety protocols for storage and handling, which may be challenging to implement in remote areas with limited technical capacity. Third, the establishment of reliable supply chains for spare parts and maintenance remains uncertain. Despite these challenges, rapid technological progress and ongoing technological progress suggest that hydrogen will play a central role in the future of island microgrids, especially when combined with advanced energy management systems (EMS) that can optimize its integration.

Feasibility and implementation barriers. Hydrogen is most relevant when islands face multi-week resource droughts or strong seasonality that makes battery-only autonomy economically inefficient. However, feasibility is constrained by minimum viable scale (CAPEX and O&M costs of electrolysers/fuel cells), water availability and treatment needs, storage safety requirements (setbacks, permitting, hazard management) and the availability of local technical capacity for maintenance and spare parts logistics. For small islands, hybrid portfolios (BESS for fast dynamics and hydrogen for long-duration adequacy) typically require careful sizing and staged deployment to avoid stranded assets. In this manuscript, feasibility is therefore framed using decision metrics such as renewable curtailment, unserved energy, diesel runtime and lifecycle costs (NPC/LCOE), rather than assuming that hydrogen automatically eliminates fossil backup [26,30].

Detailed hydrogen supply-chain economics and market dynamics (e.g., delivered hydrogen costs, transport logistics and demand variability) are context-specific and are therefore treated here as implementation-dependent boundary conditions rather than explicitly modeled market mechanisms.

4.2. Advanced Energy Management and AI

Even the most technically advanced hybrid configurations are constrained by the way they are managed. Traditional load-following strategies, while simple, lead to curtailment during surplus production and shortages during prolonged low-resource events. The future of island energy systems lies in the adoption of predictive and adaptive EMS that leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) (e.g., forecasting and data-driven control) alongside advanced optimization algorithms. ML forecasting improves short-term prediction of load and renewable output, enabling proactive scheduling and lower curtailment [32], while model predictive control (MPC) dynamically coordinates multi-asset dispatch under constraints, enhancing reliability and cost performance [33]. Together with prior techno-economic frameworks [34], these approaches underpin next-generation EMS for islands. However, deployment at scale is often constrained by non-technical barriers, including limited local technical capacity and a lack of a skilled workforce for commissioning, operation and maintenance of advanced EMS.

AI-enabled approaches can provide multiple advantages:

- Forecasting—By integrating weather predictions, demand profiles and historical data, AI models can accurately forecast renewable generation and consumption patterns [32,33].

- Optimization of dispatch—Advanced control systems such as Model Predictive Control (MPC) can determine the optimal real-time allocation of resources, minimizing diesel use and curtailment [34,35].

- Fault detection and resilience—Machine learning algorithms can detect anomalies in system operation and trigger corrective actions before failures occur [33,35].

- Demand-side integration—Smart appliances and flexible loads can be dynamically adjusted based on system conditions, aligning demand with renewable availability [35].

Recent studies show that AI-driven energy management improves renewable utilization and reduces curtailment and operating costs compared to conventional rule-based strategies [33,35]. For islands with high seasonal demand variability, such as those reliant on tourism, predictive optimization is particularly crucial. By anticipating peaks in demand and fluctuations in renewable resources, AI systems can schedule storage use and backup dispatch more efficiently, avoiding both blackouts and excessive curtailment. Beyond operational optimization, AI methods also support planning and sizing of PV–wind–storage systems; for example, machine-learning-based models (including surrogate modeling) can accelerate configuration and improve component sizing under variable climatic and demand conditions, supporting cost-effective and resilient system design [34].

Implementation prerequisites. AI/ML and predictive control are not “plug-and-play” upgrades. Their effectiveness depends on data availability (high-resolution load/RES measurements), communication reliability, cybersecurity and operator acceptance. Islands often face limited SCADA instrumentation and intermittent connectivity, so robust baselines (e.g., MPC/optimization with explicit constraints) should be benchmarked against simpler rule-based dispatch using transparent metrics (curtailment rate, renewable fraction, unserved energy, diesel starts and operating cost).

At the same time, AI integration introduces important trade-offs that are particularly salient in remote communities. First, effective operation and maintenance of AI-enabled EMS requires a skilled workforce (or reliable external support), which may be limited in small island settings and can increase dependence on vendors and continuous training. Second, increased digitalization expands the cyber-attack surface of island microgrids, making robust cybersecurity-by-design, secure communications and contingency procedures essential. Third, the use of high-resolution consumption and operational data raises questions of data ownership, privacy and data sovereignty (e.g., where data are stored and who can access them), which can affect trust and acceptance. These issues reinforce the need for staged deployment, clear governance arrangements and risk-informed design alongside performance optimization. We therefore frame AI-enabled management as an incremental pathway—monitoring → forecasting → predictive dispatch—rather than an immediate replacement of conventional control [13,16,33]. Crucially, the value of predictive EMS increases further when islands move beyond electricity-only operation toward integrated multi-sector systems. The next section discusses sector coupling, where AI-enabled EMS becomes the coordinating layer that aligns flexible cross-sector loads (e.g., EV charging, desalination, heating/cooling) with renewable availability.

4.3. Sector Coupling and Integrated Resource Use

Sector coupling expands the controllable ‘solution space’ for EMS by introducing additional flexible loads and storage-like services across end-use sectors. Accordingly, many of the AI/ML capabilities discussed in Section 4.2 (forecasting, predictive dispatch and constraint-aware optimization) become even more valuable when electricity, water, mobility and heat are co-optimized. Beyond electricity, remote islands must also address parallel challenges in heating, cooling, mobility and water supply. The concept of sector coupling—integrating electricity with other end-use sectors—offers a pathway to maximize renewable resource utilization and system-wide efficiency.

For example:

- Electric mobility: The adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) can provide flexible demand that absorbs excess renewable electricity, while vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies allow EV batteries to act as distributed storage assets [36,37].

- Intentional renewable oversizing for sector coupling: In some island systems, limited RES oversizing can be a deliberate design choice when surplus electricity is routed to other sectors—most notably transportation via EV charging (and V2G where feasible)—turning potential curtailment into useful energy services and improving overall system utilization.

- Desalination and water management: Many islands rely on an energy-intensive desalination plants for freshwater. Scheduling desalination during periods of renewable surplus can balance demand and reduce curtailment. This scheduling can be further improved through AI-enabled forecasting and predictive control that aligns desalination operation with expected renewable surplus and grid constraints. In this way, freshwater storage (tanks/reservoirs) can function as a practical ‘operational energy buffer’, converting surplus electricity into stored water and shifting an energy-intensive production away from scarce-generation periods.

- Heating and cooling: Electrification of heating and cooling through heat pumps can align with renewable output, especially when combined with thermal storage.

In this context, energy cascading (cascaded use) can further enhance system-wide efficiency by reusing energy across services—for example, routing waste heat from generators, electrolysers or fuel cells to domestic hot water, space heating, or thermal desalination and enabling heat-driven cooling where relevant. Such cascaded pathways reduce total energy input and can lower curtailment by expanding the set of useful end-uses that absorb renewable surplus.

Importantly, the flexibility offered by EV charging (and V2G where feasible) is only fully exploitable through an island-appropriate EMS that co-optimizes distributed storage, flexible loads (e.g., desalination) and backup operation under network and reliability constraints. Framing EV/V2G and EMS together in this way emphasizes their functional role as complementary enablers of curtailment reduction and peak management rather than separate “emerging trends” [36,37].

Sector coupling thus transforms islands into multi-energy systems, where electricity, water, transport and heating are co-optimized rather than managed separately. This approach not only enhances technical resilience but also promotes local development by integrating energy transition into broader socio-economic activities. In practice, sector coupling on islands is constrained by space (ports/charging infrastructure), local grid limits, tariff design and acceptance of demand-shifting (e.g., desalination scheduling), including practical integration of flexible loads and cascaded heat uses [36,37,38].

Beyond PV and wind, marine renewables can act as a complementary resource layer for specific island contexts, particularly where oceanographic conditions are favorable. Tidal-stream generation is often highlighted for its cyclic and comparatively predictable output, which may support more reliable scheduling of flexible island loads (e.g., desalination) and storage dispatch than highly weather-driven resources. Wave energy can also contribute meaningful generation in exposed coastal settings, but its performance and seasonal profile are strongly site-dependent and still constrained by technology maturity and O&M logistics. In tropical and subtropical regions, ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) is frequently discussed as a potential continuous (baseload) option and can be linked with cooling or water services, yet it remains capital-intensive and infrastructure-demanding [39]. Accordingly, maritime resources are best framed as selective complements within hybrid portfolios—supporting adequacy and curtailment reduction in well-suited sites—rather than universally applicable solutions for all islands.

Given the pivotal role of ports and maritime transport in island economies, integrating these sectors into the renewable energy transition is essential. Hybrid port infrastructures that combine on-site generation, advanced storage systems and AI-enabled energy management can significantly reduce emissions from docked vessels and port operations. Moreover, the concept of nearly zero-energy ports demonstrates how HRES can be extended beyond the island grid to include maritime facilities, creating synergistic energy ecosystems [38].

4.4. Governance, Financing and Social Dimensions

While technical innovations are essential, the social and institutional dimension will determine the actual pace of transition. Published evidence suggests that lack of community involvement and inadequate financing mechanisms frequently undermine otherwise viable projects. The next generation of hybrid island systems must therefore integrate participatory planning frameworks, ensuring that local populations are actively engaged in decision-making and share in the benefits of renewable energy.

Importantly, even when studies report competitive (or lower) LCOE, acceptance is often shaped by what residents actually experience on their electricity bills. Whether system-level savings translate into lower consumer costs depends on tariff design, fixed charges, settlement rules and the way benefits are allocated (e.g., bill credits through REC schemes). Governance and financing models should therefore include explicit mechanisms for transparent and fair pass-through of benefits, since visible bill reductions are frequently among the strongest arguments for local support.

Cultural and political economy constraints. Beyond formal institutions, island energy transitions are shaped by local cultural norms, power structures and political economy. Social acceptance and “participatory planning” can be constrained by asymmetric access to information and decision-making, historical distrust toward external developers and local clientelistic dynamics that influence siting decisions and permitting outcomes. In practice, conflicts may emerge between incumbent actors benefiting from the status quo (e.g., fuel supply chains, local contractors, political patrons) and new renewable energy communities (RECs) arrangements. Even when RECs are legally enabled, implementation may face governance frictions such as contested representation (“who speaks for the community”), benefit-sharing disputes, tariff and connection-rule uncertainty and concerns about procedural fairness and distributional justice. These dynamics can delay commissioning and increase transaction costs. They may also affect operational performance through curtailment disputes, unclear maintenance responsibilities, or limitations on demand-side participation.

Equally important is the establishment of innovative financing mechanisms tailored to the constraints of small island economies. These may include blended finance models, international climate funds, or community-based ownership schemes that reduce upfront investment barriers. Regulatory frameworks must also evolve to facilitate decentralized energy governance, allowing microgrids to operate flexibly while maintaining safety and reliability.

Table 4 synthesizes these recurring governance risks into practical checkpoints for RECs in remote-island HRES, alongside indicative mitigation measures and operational implications.

Table 4.

Governance and conflict-of-interest checkpoints for RECs in remote-island HRES (indicative).

4.5. Research and Deployment Priorities for Next-Generation Island HRES

Based on the evidence synthesized in Section 3, future work should prioritize island-relevant questions that can be tested, compared and implemented across contexts:

- Seasonal adequacy and least-regret storage portfolios: quantify when batteries alone are sufficient versus when long-duration storage (e.g., hydrogen) is justified under multi-year weather variability and tourism-driven demand swings.

- Control architectures that reduce curtailment without oversizing: benchmark AI-enabled forecasting and predictive dispatch against robust optimization baselines using common metrics (renewable fraction, unserved energy, curtailment rate, diesel runtime and lifecycle cost).

- Sector coupling with island constraints: evaluate electricity–heat–mobility coupling options under realistic infrastructure limits (space, water, port logistics) and local acceptance considerations.

- Governance and participation as performance enablers: assess how ownership models, tariff design and participatory planning affect project timelines, acceptance and operational outcomes, particularly where external funding and technical capacity are limited.

Collectively, these priorities shift the discussion from generic “future directions” to island-specific evidence needs and decision-ready design guidance. To operationalize these feasibility considerations, Table 5 summarizes an indicative checklist of constraints and decision-relevant metrics for island HRES.

Table 5.

Feasibility checklist and decision metrics for next-generation hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) on remote islands (indicative).

4.6. Actionable Policy and Financing Implementation Pathways

Although “hybrid financing models” and “regulatory reforms” are often discussed at a high level, island projects require sequenced, implementation-ready pathways that match the local policy environment and institutional capacity. To operationalize these recommendations without prescribing country-specific rules, we translate them into practical instruments, responsible actors and typical sequencing using common island policy archetypes. Table 6 summarizes actionable regulatory and financing steps that can be adapted to specific national and regional contexts.

Table 6.

Actionable policy and financing implementation pathways for island hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES), by policy archetype (indicative).

4.7. Synthesis

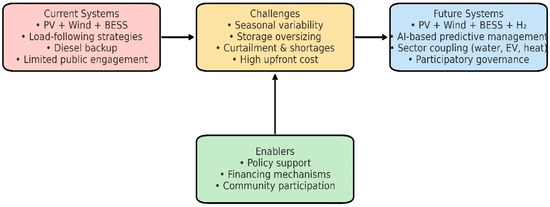

Taken together, the technological pillars—hydrogen storage, AI-enabled energy management and sector coupling—alongside governance and financing innovations, outline a coherent trajectory for the future of hybrid island systems. Moving beyond transitional solutions based on oversized batteries and diesel backup, next-generation systems are expected to become multi-layered, intelligent and socially embedded. In line with the research and deployment priorities summarized in Section 4.5, these configurations may deliver higher renewable penetration and lower emissions while improving resilience, economic viability and community acceptance. Figure 4 summarizes this transition by mapping the evolution from current to future systems across technical, economic and social dimensions.

Figure 4.

Transition pathways for future hybrid off-grid systems on remote islands (source: authors’ elaboration).

5. Social Acceptance and Participatory Planning

The success of HRES on remote islands depends not only on technological feasibility and economic viability but also on the degree of social acceptance among local communities. Social acceptance is multidimensional, encompassing perceptions of fairness, levels of trust in institutions, transparency of decision-making and the quality of community engagement throughout the project cycle [9]. Without the involvement and support of local populations, even technically sound projects risk delays, resistance, or outright cancelation.

One of the most important factors is trust and transparency. When citizens perceive that information about project objectives, impacts and benefits is openly shared and when they are invited to participate in the planning process, acceptance tends to rise. Conversely, opaque procedures or top-down impositions generate suspicion and resistance [40]. This is particularly evident in small island contexts, where close-knit social networks amplify both positive and negative narratives surrounding renewable energy projects.

Another dimension concerns psychological and social drivers of involvement. A systematic review has shown that citizens are more likely to support and actively participate in renewable energy initiatives when they perceive direct benefits—such as reduced energy costs, increased resilience, or community ownership structures—combined with a sense of collective efficacy and fairness [41]. Participation is therefore not only a procedural issue but also a matter of identity, belonging and perceived empowerment.

RECs offer a practical model for participatory planning in islands. These initiatives allow local stakeholders to co-own generation and storage assets, share economic benefits and engage in decision-making. Evidence suggests that RECs can enhance social cohesion and distribute the gains of energy transition more equitably, particularly in resource-constrained settings. When properly designed, RECs can align individual motivations with collective goals, fostering a virtuous cycle of trust, participation and long-term sustainability.

Beyond island settings, evidence from remote islanded microgrid communities (e.g., Alaska) indicates that local capacity, governance and ownership arrangements are pivotal for adopting and sustaining community renewable energy projects, reinforcing the importance of community-driven planning and locally anchored co-ownership models [42].

For island microgrids, participatory planning is not a luxury but a necessity. Ensuring that citizens are included from the earliest stages of project development that their concerns are addressed and that benefits are tangibly shared, increases the likelihood of durable social acceptance. Ultimately, the integration of participatory models and RECs can transform hybrid off-grid systems from externally driven projects into genuinely community-anchored infrastructures. In this respect, community-driven bottom-up approaches—co-designed with local stakeholders and aligned with local priorities—are generally more suitable than purely top-down deployment for building legitimacy, sustained engagement and long-term operability.

Beyond technical optimization and community participation, the long-term success of hybrid off-grid systems depends heavily on user education and behavioral adaptation. Training programs that cultivate energy literacy, promote efficient consumption habits and enhance awareness of renewable resource variability can significantly improve the stability and sustainability of island microgrids. Empowering end-users to understand load management, demand-response principles and maintenance responsibilities not only reduces system stress but also strengthens local ownership and resilience. Educational interventions—ranging from community workshops to school curricula—have demonstrated measurable reductions in energy waste and greater acceptance of intermittent renewables across similar contexts in Greece and other regions [43].

6. Discussion and Synthesis

The analysis presented in the previous sections highlights the multifaceted nature of energy transitions in remote islands. HRES have proven to be effective transitional solutions, enabling significant reductions in fossil fuel dependence and greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, the reviewed case studies and theoretical perspectives reveal persistent challenges that must be addressed to achieve resilient, autonomous and socially accepted energy systems. This section synthesizes these insights, comparing lessons across geographic contexts and integrates technological, economic and social dimensions to outline pathways for accelerating the global diffusion of hybrid off-grid systems.

6.1. Key Insights from Technical Perspectives

Published evidence demonstrates that PV–wind–battery architectures remain the dominant design paradigm for island microgrids. In Zanzibar, Thailand and Malaysia, techno-economic optimization studies have shown that properly sized hybrid systems can achieve competitive levelized costs of electricity compared to diesel-only baselines [23,24,26]. In Europe and Latin America, islands such as Graciosa, Nisyros and the Galápagos have made notable strides toward high renewable penetration, with renewable fractions often exceeding 60–70% [20,27,28]. These achievements confirm that hybrid systems can reliably meet demand in isolated environments.

However, the studies also reveal the structural limitations of current architectures. Battery storage, while critical for smoothing short-term fluctuations, remains inadequate for addressing multi-day or seasonal gaps [25]. Oversizing battery capacity introduces significant financial and environmental costs, requiring land-intensive installations and entailing high embodied emissions from production. Even in advanced cases, such as Graciosa or the Galápagos, reliance on fossil backup remains unavoidable during prolonged periods of low wind and solar output [27,28]. This confirms that current-generation systems, while effective, are inherently transitional.

6.2. Comparative Lessons from Case Studies

A cross-case comparison highlights both commonalities and regional specificities. Tourism-driven islands such as Koh Samui face unique seasonal demand profiles, where peak loads coincide with resource scarcity, exposing the weaknesses of simple load-following strategies [24]. By contrast, smaller and less industrialized islands such as Tumbatu and Nisyros emphasize affordability and autonomy, where techno-economic optimization demonstrates the feasibility of near-total fossil independence under favorable resource conditions [20,23].

The Galápagos and Graciosa provide intermediate lessons. Both islands show that high renewable shares are achievable in practice, but they also illustrate that infrastructure upgrades, diversified storage portfolios—including batteries for short-term balancing and hydrogen or thermal systems for seasonal energy buffering—and advanced dispatch strategies are essential for moving beyond transitional reliance on fossil fuels [27,28]. The corresponding techno-economic cost indicators (LCOE/COE/NPC), where reported in the primary sources, are summarized in Table 3 for transparency and cross-case comparability. These findings suggest that while technical feasibility is no longer in question, the decisive factor is whether systems can balance reliability, affordability and sustainability ensuring at the same time a dynamic equilibrium between energy supply and demand through demand-side management and adaptive consumption strategies across diverse socio-economic contexts.

6.3. Integration of Technological and Social Dimensions

One of the most salient findings is that technological innovation alone is insufficient to guarantee successful energy transitions. Social acceptance, community participation and institutional support are equally critical. As highlighted in Section 5, citizens’ perceptions of fairness, transparency and procedural justice strongly shape the acceptance of renewable projects [9,10,40]. In island contexts, where communities are small, interconnected and often highly dependent on natural resources, social opposition can delay or derail even technically and economically viable projects.

Participatory planning models, such RECs, provide promising avenues for bridging this gap. Evidence suggests that co-ownership, trust-building and transparent decision-making significantly enhance project legitimacy [40]. This aligns with the broader observation that energy transitions on islands cannot be approached as purely technical exercises; they must also be treated as social innovations. Across the six case-study communities, the governance message is consistent even if the institutional instruments differ. Tumbatu (grid-connected) highlights the importance of financing capacity and enabling policy conditions; Koh Samui illustrates how tourism-driven seasonality makes demand-side participation and clear benefit-sharing particularly salient; Pulau Perhentian emphasizes that advanced control can improve performance but still requires local capacity for operation and ownership/role clarity; Galápagos and Graciosa underline that scaling to high renewable shares often depends on coordinated infrastructure upgrades, credible investment frameworks and stakeholder legitimacy; and Nisyros demonstrates that even when techno-economic autonomy appears feasible, durable implementation still hinges on community anchoring and policy support. Taken together, these cases motivate participatory models (including RECs where legally feasible) as practical delivery mechanisms for trust, benefit-sharing and long-term operability—rather than as one-size-fits-all institutional prescriptions.

6.4. Policy and Governance Implications

The transition to next-generation hybrid systems requires enabling policy frameworks. Regulatory reforms are needed to accommodate decentralized, community-driven models, which are often hindered by outdated financial and legal frameworks [10]. Stable investment environments, targeted subsidies and innovative financing mechanisms are necessary to overcome the high upfront costs of advanced hybrid systems, particularly in regions with limited access to capital.

International cooperation and knowledge transfer play a decisive role. Programs such as the European Green Deal and the UN Sustainable Development Goals explicitly identify islands as laboratories for sustainable transitions [1,2]. Yet, realizing these ambitions requires tailoring support to local contexts, ensuring that technical designs align with socio-economic realities and governance structures. The case studies show that while technical designs are transferable, social and institutional dynamics vary significantly across regions.

In this respect, islands such as Nisyros, Galápagos and Graciosa highlight the need for integrated approaches that combine infrastructure investment with participatory governance. Importantly, cultural context can materially shape ‘social buy-in’: place-based identities and connections to land/sea (including Indigenous or traditional communities where present) often influence perceptions of environmental risk, fairness and what counts as an acceptable intervention in nature. Without social buy-in and institutional support, the adoption of next-generation technologies such as green hydrogen storage or AI-enabled energy management will likely face delays and resistance, regardless of their technical potential.

6.5. Outlook: Scientific Contributions, Research Gaps and a Roadmap

To keep the conclusion concise, we summarize the forward-looking implications of this Perspective in the following Outlook, combining research gaps with a practical roadmap.

6.5.1. Scientific Contributions and Research Gaps

This Perspective provides a structured synthesis of recent technical and social insights on island HRES and identifies priority research and deployment gaps. First, it synthesizes technical and social insights from a geographically diverse set of case studies, providing a global overview of hybrid microgrid performance under real-world conditions. Second, it highlights the limitations of current PV–wind–BESS configurations, particularly their reliance on battery oversizing and fossil backup. Third, it emphasizes the importance of social acceptance and participatory planning as integral components of successful transitions.

At the same time, the review identifies several research gaps. These include:

- Seasonal and multi-day storage solutions: While hydrogen integration shows promise, more empirical field-based and data-driven rather than purely model-based research is needed to evaluate its techno-economic feasibility in small-scale island contexts [11,12].

- AI-enabled energy management: Although simulation studies show substantial potential for predictive optimization [16], real-world pilot projects remain limited.

- Socio-technical integration: Further research is required to operationalize participatory planning frameworks, evaluating how trust, fairness and co-ownership influence long-term system performance [9,41].

- Environmental trade-offs: Life cycle assessments of storage technologies (batteries, hydrogen systems) must be systematically integrated into techno-economic analyses to avoid unintended consequences. In the case of hydrogen, such evaluations should also account for specific technological constraints, including high-pressure or cryogenic storage requirements, energy losses in conversion cycles and potential safety and material handling challenges.

6.5.2. Toward a Roadmap for Resilient Island Transitions

Taken together, these insights suggest a roadmap for advancing hybrid off-grid systems in remote islands. The transition involves a threefold integration:

- Technological innovation—scaling up hybrid systems with long-term storage, AI-enabled optimization and sector coupling.

- Institutional reform—adapting regulatory and financial frameworks to support decentralized and participatory models.

- Social engagement—embedding communities in the planning and governance of energy projects to ensure legitimacy and long-term viability.

By addressing these dimensions in tandem, islands can move from transitional hybrid microgrids toward fully autonomous, resilient and socially embedded energy systems. Such progress would not only secure sustainable futures for island communities but also provide transferable models for broader applications in remote or resource-constrained regions worldwide.

7. Conclusions

This Perspective synthesized recent technical and socio-institutional evidence on hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) for remote and island (-like) power systems, drawing on six published case studies across diverse geographies. Across contexts, high renewable shares are increasingly achievable, yet most deployments remain constrained by intermittency, limited long-duration storage and the operational limits of rule-based control—often resulting in continued reliance on diesel backup and/or costly oversizing. The primary conclusion is that successful island transitions require integrated solutions: technological advances (longer-duration storage, improved energy management/dispatch and sector coupling where appropriate) must be matched by enabling regulation, bankable financing and genuinely participatory governance that makes benefits visible and fairly shared. Together, these elements determine whether techno-economic feasibility translates into durable, resilient and socially accepted real-world implementation.

Author Contributions

All authors, E.T. and F.A.C. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ochoa-Correa, D.; Arévalo, P.; Martinez, S. Pathways to 100% renewable energy in island systems: A systematic review of challenges, solutions strategies and success cases. Technologies 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.F.; Pires, A.; Cordeiro, A. DC microgrids: Benefits, architectures, perspectives and challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedraityte, A.; Rimkus, A.; Kliaugaite, D. Hybrid renewable energy systems: A review of optimization approaches and future challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehallou, A.; M’hamdi, B.; Amari, A.; Teguar, M.; Rabehi, A.; Guermoui, M.; Alharbi, A.H.; El-kenawy, E.-S.M.; Khafaga, D.S. Optimal multiobjective design of an autonomous hybrid renewable energy system in the Adrar Region, Algeria. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Shankar, A. Optimizing wind-PV-battery microgrids for sustainable and resilient residential communities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punitha, S.; Subramaniam, N.P.; Vimal Raj, P.A.D. A comprehensive review of microgrid challenges in architectures, mitigation approaches and future directions. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2024, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wei, W.; Bai, J.; Mei, S. Long-term operation of isolated microgrids with renewables and hybrid seasonal-battery storage. Appl. Energy 2023, 349, 121628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.; Schneider, N.; Wüstenhagen, R. Dynamics of social acceptance of renewable energy: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2023, 181, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegatto, M.; Bobbio, A.; Freschi, G.; Zamperini, A. The social acceptance of renewable energy communities: The role of socio-political control and impure altruism. Climate 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Liu, C.-W.; Hsu, Y.-C. Assessing the public’s social acceptance of renewable energy management in Taiwan. Land 2025, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of islands considering offshore hydrogen production. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, A.A.; Khosravi, A.; Alqahtani, A.; Alshammari, F. Optimal design for a hybrid microgrid–hydrogen storage facility in Saudi Arabia. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, Y.; Qiqieh, I.; Alzubi, J.; Alzubi, O.; Allahham, A.; Giaouris, D. Design of cost-based sizing and energy management framework for standalone microgrid using reinforcement learning. Sol. Energy 2023, 251, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, H.M.; Chehimi, M.; Khalaf, A. Photovoltaic sizing using machine learning. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yang, K.; Song, Z.; Ma, Y.; Meng, J. Inner-outer layer co-optimization of sizing and energy management for renewable energy microgrid with storage. Appl. Energy 2024, 363, 123066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, F.; Pavón, W.; Minchala, L.I. Forecast-Based Energy Management for Optimal Energy Dispatch in a Microgrid. Energies 2024, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, H. Sector Coupling and Migration towards Carbon-Neutral Power Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Benavides, D.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Ríos, A.; Torres, D.; Villanueva-Machado, C.W. Smart Microgrid Management and Optimization: A Systematic Review Towards the Proposal of Smart Management Models. Algorithms 2025, 18, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopetou, N.; Zestanakis, P.A.; Rotas, R.; Iliadis, P.; Papadopoulos, C.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Sfakianakis, A.; Koroneos, C. Energy analysis and environmental impact assessment for self-sufficient non-interconnected islands: The case of Nisyros Island. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiaras, E.; Andreosatou, Z.; Kouveli, A.; Tampekis, S.; Coutelieris, F.A. Off-Grid methodology for sustainable electricity in medium-sized settlements: The case of Nisyros Island. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschede, H.; Bertheau, P.; Khalili, S.; Breyer, C. A review of 100% renewable energy scenarios on islands. WIREs Energy Environ. 2022, 11, e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouederni, R.; Davidson, I.E. Co-Optimized Design of Islanded Hybrid Microgrids Using Synergistic AI Techniques: A Case Study for Remote Electrification. Energies 2025, 18, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, T.R.; Kichonge, B.; Kivevele, T. Optimal design and analysis of a grid-connected hybrid renewable energy system using HOMER Pro: A case study of Tumbatu Island, Zanzibar. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamharnphol, R.; Kamdar, I.; Waewsak, J.; Chaichan, W.; Khunpetch, S.; Chiwamongkhonkarn, S.; Kongruang, C.; Gagnon, Y. Microgrid hybrid solar/wind/diesel and battery energy storage power generation system: Application to Koh Samui, Southern Thailand. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2023, 12, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, B.; Posch, S.; Wimmer, A.; Pirker, G. Hybrid model predictive control of renewable microgrids and seasonal hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31677–31692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shezan Sk, A.; Ishraque, M.F.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Kamwa, I.; Paul, L.C.; Muyeen, S.M.; Nss, R.; Saleheen, M.Z.; Kumar, P.P. Optimization and Control of Solar–Wind Islanded Hybrid Microgrid Using Heuristic and Deterministic Optimization Algorithms and a Fuzzy Logic Controller. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 3272–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Cuesta, A.; Zakaria, A.; Herrera-Perez, V.; Djokic, S.Z. Transition to a 100% renewable power supply in Galápagos Islands: Long-term and short-term analysis for optimal operation and sizing of grid upgrades. Renew. Energy 2024, 234, 121207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, T.; Jesus, J.; Magano, J. Graciosa Island’s hybrid energy system expansion scenarios: A technical and economic analysis. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superchi, F.; Bianchini, A.; Moustakis, A.; Pechlivanoglou, G. Toward sustainable energy independence: A case study of green hydrogen as seasonal storage integration in a small island. Renew. Energy 2025, 245, 122813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, D.; Heggedal, A.M.; Løvås, T. The potential of hydrogen–battery storage systems for a sustainable renewable-based electrification of remote islands in Norway. J. Energy Storage 2024, 75, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Lee, H.-B.; Kim, N.; Park, S.; Joshua, S.R. Integrated battery and hydrogen energy storage for enhanced grid power savings and green hydrogen utilization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.R.; Kumar, R.S.; Bajaj, M.; Khadse, C.B.; Zaitsev, I. Machine learning-based energy management and power forecasting in grid-connected microgrids with multiple distributed energy sources. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S. Model predictive control-based energy management system for cooperative optimization of grid-connected microgrids. Energies 2025, 18, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Khan, M.; Rehman, S. A review of hybrid renewable and sustainable power systems: Sizing, optimization, control and energy management. Energies 2024, 17, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Rezaei, M. Enhancing microgrid performance with AI-based predictive control. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.A.; Eltamaly, A.M. Upgrading Conventional Power System for Accommodating Electric Vehicle through Demand Side Management and V2G Concepts. Energies 2022, 15, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltamaly, A.M. Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Electric Vehicles in V2G Applications. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 3161–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholidis, D.; Sifakis, N.; Chachalis, A.; Savvakis, N.; Arampatzis, G. Energy transition framework for nearly zero-energy ports: HRES planning, storage integration and implementation roadmap. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]