Abstract

Accurate short-term electricity load forecasting (STELF) is essential for grid scheduling and low-carbon smart grids. However, load exhibits multi-timescale periodicity and non-stationary fluctuations, making STELF highly challenging for existing models. To address this challenge, an Autoformer–Transformer residual fusion network (ATRFN) is proposed in this paper. A dynamic weighting mechanism is applied to combine the outputs of Autoformer and Transformer through residual connections. In this way, lightweight result-level fusion is enabled without modifications to either architecture. In experimental validations on real-world load datasets, the proposed ATRFN model achieves notable performance gains over single STELF models. For univariate STELF, the ATRFN model reduces forecasting errors by 11.94% in mean squared error (MSE), 10.51% in mean absolute error (MAE), and 7.99% in mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) compared with the best single model. In multivariate experiments, it further decreases errors by at least 5.22% in MSE, 2.77% in MAE, and 2.85% in MAPE, demonstrating consistent improvements in predictive accuracy.

1. Introduction

Carbon peaking and carbon neutrality have become a global consensus, significantly impacting the power industry and driving a shift from fossil-fuel-dominated systems to those with high renewable energy penetration [1]. However, renewable generation such as wind and photovoltaic exhibits strong intermittency, while diversified load patterns exhibit time-varying characteristics [2]. Therefore, the dual uncertainty on both the generation side and the load side of the power system poses higher requirements and significant challenges for electric system dispatching [3]. Accurate short-term electricity load forecasting (STELF) can provide effective data support for real-time electric system dispatching and resource allocation by utility companies [4]. Consequently, the stability and reliability of the electric system are enhanced, and situations of power shortages or over-supply are avoided [5].

Existing STELF methods can be broadly divided into traditional statistical methods [6] and data-driven approaches [7]. The autoregressive integrated moving average model [8], exponential smoothing [9], and support vector regression (SVR) [10] are representative traditional methods. They are founded on stationarity assumptions. These methods are designed to capture linear or weakly nonlinear patterns, but their effectiveness is constrained by the growing nonlinearity and heterogeneity of modern load data [11].

Data-driven approaches are employed to capture intrinsic structures and patterns in complex, high-dimensional datasets [12]. Feature learning models are one class of da-ta-driven approaches. Extreme gradient boosting [13] and random forest [14] are representative, which are applied to extract key factors from raw data. Nevertheless, these models are constrained by their reliance on feature engineering, thereby ability to capture long-term temporal dependencies is limited [15]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are another class of data-driven approaches [16]. CNNs were initially applied to the processing of image data, but are now increasingly used for non-image data, particularly for extracting local features in time series [17]. However, the receptive field of a CNN may be insufficient to capture long-term temporal dependencies, particularly in shallow networks [18]. Increasing network depth can expand the receptive field, but this also increases computational costs and training complexity [19]. Combining CNNs with gated recurrent units (GRU) [20] or long short-term memory networks (LSTM) [21] has proven to be a highly effective strategy for application in STELF. For instance, hybrid CNN-LSTM models have been proposed for district heating load prediction [22], while CNN-GRU models have been applied to forecast electricity load in residential and commercial buildings [23]. Even so, these hybrid models may still face challenges when adapting to highly complex forecasting environments [6].

The Transformer architecture was introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017 [24] to address the challenge of modeling long-term dependencies in sequential data. It has achieved strong performance in tasks such as load and electricity generation forecasting. Nevertheless, the standard Transformer entails high computational and hardware costs due to redundant matrix operations [25]. To address these limitations, researchers have proposed improved variants of the Transformer to enhance its efficiency and performance. For in-stance, Transformer-XL introduce segment-level recurrence and relative positional encoding, which enable better capture of long-range dependencies in very long sequences [26]. This approach also reduces reliance on fixed-length input windows, thereby im-proving the model’s ability to capture long-distance dependencies. Reformer employs locality-sensitive hashing to approximate the attention weights, significantly lowering memory consumption and computational cost [27]. The Autoformer model was introduced with improvements to the automatic decomposition mechanism and the self-correlation mechanism, and it demonstrates superior performance in handling com-plex time series data [28]. Furthermore, the ITransformer model has been proposed, incorporating a frequency-domain feature extraction module to enhance the accuracy of STELF [29]. Some other example for Autoformer and Transformer in load forecasting: an autoformer variant with frequency enhancement has been applied for loads forecasting [30]; an Autoformer has been combined with CNN-attention-BiGRU for load forecasting [31]; Granularity has been combined with Autoformer for probabilistic load forecasting [4]; transformer has been applied for multienergy load forecasting [32]; CEEMDAN and Transformer has been combined for load forecasting [33]; transformer and domain knowledge has been integrated for load forecasting [34].

Although different Transformer variants have introduced targeted improvements, their strengths are often specialized rather than comprehensive. For example, the Informer enhances efficiency in handling long sequences through probabilistic sparse self-attention [35], the Reformer reduces memory requirements for long-sequence modeling [36], and the Autoformer, with its decomposition mechanism, is effective in trend and periodic com-ponent modeling [37]. However, these advantages remain confined to specific aspects, making it difficult for any single model to consistently achieve superior performance across diverse forecasting scenarios [38]. For example, previous studies, have shown that the synergy between Transformer and GRU architectures can enhance robustness [39], yet how to leverage the strengths of different models and integrate them effectively remains a significant challenge.

In summary, when the prediction accuracy of STELF is insufficient, researchers typically improve performance by adjusting model parameters or by adopting serial or parallel architectural designs. However, repeatedly training a model with different parameter settings still results in a limited accuracy gain, since the underlying network architecture remains unchanged. Serial architectures essentially deepen the network, which inevitably increases training time and memory consumption. Parallel architectures, on the other hand, broaden the network, leading to similar increases in computational cost. Therefore, whether through parameter tuning or through serial and parallel extensions, these approaches fundamentally rely on training a single network, and the upper bound of their predictive performance is inherently constrained. To tackle the challenge of diminishing returns in STELF accuracy with single deep temporal models, an Autoformer-Transformer residual fusion network (ATRFN) is presented to enhance forecasting precision in this study. In this study, the outputs of the two base networks are fed into a third network, which aggregates their complementary features without increasing the overall network depth or width. In this study, the outputs of the two base networks are fed into a third network, which aggregates their complementary features without increasing the overall network depth or width. This design enables the model to maximally integrate the strengths of both preceding networks into the final prediction output. The research innovations are articulated as follows.

- (1)

- Designing sophisticated deep learning architectures often incurs significant computational costs and time investments. Paradoxically, escalating model complexity do not universally translate to superior forecasting precision. This study presents a light-weight ensemble strategy that achieves pre-trained Autoformer and Transformer forecasting outputs fusion through dynamic residual correction. This strategy demonstrates that adaptive fusion of specialized models achieves superior prediction accuracy com-pared to monolithic networks, embodying the principle that collective modeling expertise outperforms individual architectural complexity.

- (2)

- Unlike traditional ensemble learning methods, this study introduces a dynamic residual correction mechanism that explicitly leverages the complementary strengths of specialized models. By a validation-driven model prioritization strategy, the framework assigns the model with minimal validation dataset forecasting error as the primary back-bone and repurposes the other as a prediction error corrector to adaptively correct discrepancies in the backbone’s forecasts.

- (3)

- A data-driven adaptive weight matrix is adopted for result-level fusion, dynamically combining the predictions of Autoformer and Transformer. This matrix outperforms traditional fixed-weight ensembles by prioritizing model strengths and suppressing redundant errors, thus achieving high forecasting accuracy.

- (4)

- Leveraging the inherent differences in feature extraction mechanisms between Transformer and Autoformer, their STELF results may have complementary relationships at certain times. The residual fusion network is employed to fuse the forecasting results of Transformer and Autoformer to achieve error cancellation and accurate prediction of load fluctuation trends, thus improving the forecasting performance of the model. In single-region STELF experiments, Transformer outperformed Autoformer in prediction performance. ATRFN achieved 14.49% lower mean squared error (MSE), 10.51% lower mean absolute error (MAE), and 9.16% lower mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) compared to Transformer. In multi-region STELF experiments, where Autoformer demonstrated bet-ter performance than Transformer, ATRFN still reduced MSE, MAE, and MAPE by 5.22%, 2.77%, and 5.88%, respectively, compared to Autoformer. Experimental results on both datasets consistently demonstrate the effectiveness of ATRFN for STELF tasks. Additionally, ATRFN outperformed all baseline models in predictions, further validating its superiority across different regional scenarios.

2. Methodology

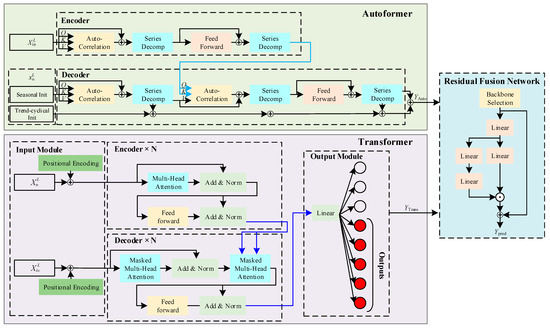

To overcome the challenges in collaborative modeling of cross-week trend patterns and multi-scale periodic components in STELF, this study designs a lightweight model fusion framework (Figure 1). The framework employs a dual-engine parallel architecture that retains the networks structure of Autoformer and Transformer while implementing task-decoupled modeling. The Transformer leverages multi-head self-attention to focus on capturing short-term abrupt features, whereas the Autoformer applies periodic decomposition to explicitly model long-periodic fluctuation components. The forecast results of the two models are dynamically integrated through a residual correction network. The primary model provides baseline predictions, while the secondary model provides directionally adaptive residual correction signals. The primary model is determined mainly by the error of the validation dataset. This non-intrusive fusion strategy not only avoids structural modifications to the pre-trained models but also significantly enhances the framework’s ability to represent complex load variations through a modular design.

Figure 1.

Network structure of residual fusion network for Autoformer and Transformer.

2.1. Autoformer

For time series data exhibiting mixed characteristics of periodic fluctuations and aperiodic trends, Autoformer employs an explicit temporal decomposition framework coupled with an innovative Auto-Correlation module. This architecture enables automatic identification and modeling of periodic correlations across multiple temporal scales. The core modeling process can be summarized as follows.

Component separation of trend and seasonal terms is achieved by moving-average periodic decomposition with frequency-domain filtering, computed as Formula (1).

where represents the input tensor of length , is representing a padding operation, is stand for moving-average operation, is trend component, and is seasonal component.

To address the limitation of point-wise self-attention in identifying in-phase similarities, authors implement an Auto-Correlation mechanism. This approach leverages the Wiener-Khinchin theorem to compute the full-delay autocorrelation function by fast Fourier transform (FFT), which quantitatively evaluates subsequence similarity under time delay factor .

In Formula (2), and denote the FFT operator and the conjugate complex of , respectively, and is inverse FFT. The first delays with the highest autocorrelation values are selected by Formula (3). The alignment of in-phase subsequences via time-lag aggregation is followed by autocorrelation-weighted fusion, as detailed in the formulation of Formula (4).

where is the query matrix, is the key matrix, and is the value matrix. The operations of time-lagged shifting and normalization are denoted by and , respectively. The number of Auto-Correlation mechanism, the overall formulation can be compactly expressed as shown in Formula (5).

where denote the of the i-th Auto-Correlation layer, respectively. is a learnable weight parameter. Unlike traditional self-attention mechanisms, Auto-Correlation mechanism bypasses redundant pairwise computations by leveraging temporal periodicity to directly capture intra-cycle pattern similarities at corresponding positions.

Autoformer adopts the Encoder–Decoder architecture of Transformer. The Encoder takes the historical load sequence as input. The input of the Decoder is divided into two parts, including the trend part and the seasonal part , where is the length of the predicted sequence. Autoformer’s input is expressed as Equation (6).

where is the seasonal part input, which is concatenated by the seasonal component extracted from the historical load sequence and the placeholder . is the trend part input, which is concatenated by the seasonal component in the historical load sequence and the mean placeholder . provides a baseline for trend prediction, helping the model to continue or adjust the future trend direction based on .

The encoder is composed of the Auto-Correlation mechanism, series decomposition, and feedforward network, and its output be calculated as shown in Equation (7).

where is the output of the i-th encoder layer, is the output of first series decomposition of the i-th encoder layer, represents the removed trend part, and is series decomposition which is calculated as shown in Equation (1). The structure of the decoder is similar to that of the encoder, and its calculation process is as Equation (8).

where represents the output of the i-th decoder layer, and are the outputs of the first series decomposition and the second series decomposition of the i-th decoder layer, respectively. represents the input of the i-th decoder layer, and is the trend part output of the j-th series decomposition of the i-th encoder layer. The calculation of the cumulative trend part of the i-th encoder layer is shown in Equation (9).

where is the projection matrices for the trend part. The final prediction result is the sum of the output trend part and seasonal part, as shown in Equation (10).

where is the prediction result, is a projection matrix, whose role is to project the deeply transformed seasonal part to the target dimension. m is the number of encoders, and is the accumulation of the trend terms of encoders.

2.2. Transformer

Transformer achieves innovation by introducing the self-attention mechanism and feedforward neural network structure, which not only enhances the model’s capability to model long-range dependencies but also avoids the sequential dependency issues caused by recurrent structures. The Transformer network architecture comprises an input module, Encoder module, Decoder module, and output module, as shown in Figure 1.

It is important to note that the Transformer model processes input sequences with permutation invariance, lacking explicit awareness of sequential order information. Therefore, a positional encoding mechanism must be introduced to preserve temporal features. In specific implementation, temporal relationships between data points are characterized by adding positional encoding vectors to each input vector. The positional encodings are generated using sine and cosine functions, where even and odd dimensions are encoded with sine and cosine functions, respectively, as shown in Equation (11).

where denotes the positional encoding, represents the absolute position in the sequence, indicates the embedding dimension of the model. The feature input to the encoder of the Transformer is given as follows.

where is the serves as a weighing factor, represents the feature representation after one-dimensional convolution projection. denotes the length of the feature sequence, stands for the global temporal feature encoding, and is the number of temporal features. The input representation of the Transformer decoder is constructed by concatenating the auxiliary output sequence and the target output sequence , as formulated in Formula (13).

The Transformer encoder is composed of multiple identical encoder layers stacked sequentially. Each encoder layer encompasses two primary sub-layers: the multi-head self-attention mechanism and the feedforward neural network. Additionally, residual connections and layer normalization are applied after each sub-layer to enhance the training stability and expressive power of the model. The multi-head self-attention mechanism enables the model to focus on dependencies between different positions when processing the input sequence, thereby achieving global modeling. The formula for single-head attention is expressed as

where denotes the scaling factor. The multi-head mechanism is obtained by concatenating the outputs of single-head attention and integrating them through a linear layer, as shown in Formula (15).

where is the weight matrix and represents the number of attention heads. After applying the residual connection and layer normalization, the output Z can be expressed as:

where denotes layer normalization. After going through a feedforward network, its output can be represented as

where is activation function, and represent the weight and bias of the feedforward network, respectively. After another residual connection and layer normalization, the encoder’s output is given by Formula (18).

The decoder layer is similar to the encoder layer, and its masked self-attention mechanism is expressed as in Formula (19).

where is the mask matrix. The masked multi-head self-attention mechanism can be derived from Equation (15), and the decoder layer output is computed via Equations (11)–(19). Thus, the Transformer’s prediction result is expressed as

2.3. Autoformer-Transformer Residual Fusion Network

The proposed ATRFN primarily achieves deep complementation between Transformer and Autoformer in the time-series feature space via a dynamic weighted residual mechanism across feature dimensions. The core design philosophy involves dynamically selecting the output of the model with smaller prediction errors on the validation set as the feature backbone. Meanwhile, the output of the other model undergoes feature-selective enhancement using adaptive weights, and is ultimately superimposed in a residual-wise manner to generate fused features. The specific modeling process is as follows:

The average absolute prediction errors (ABPE) of Autoformer and Transformer over the validation dataset are first derived, as specified in Formula (21).

where is the actual load value, and represent the ABPE of Autoformer and Transformer on the validation set, respectively. The raw output of the model with smaller error is selected as the basic feature backbone of the model, and the raw output of the other model is applied as the input to the adaptive residual corrector, as shown in Formula (22).

To ensure the compatibility of with the features of the backbone in the semantic space, nonlinear transformation and dimensionality reduction are applied to . The output is:

where and are the weights and biases of the first time-distributed fully connected layer, respectively. To measure the supplementary value of the correction term to the backbone in each dimension and each time step, a dimension-adaptive weight matrix is designed.

where and are the linear transformation matrix and bias, respectively. Subsequently, the correction term is generated through an element-wise weighted operation.

where represents element-wise multiplication. Finally, the residual mechanism is adopted to realize the stacking of dominant features, obtaining the final prediction result .

ATRNF realizes the intelligent division of labor between Autoformer and Transformer by comparing the prediction errors on the validation set. It performs feature enhancement on the basis of the model with stronger generalization ability, ensuring that the lower limit of the fusion model is not lower than the basic prediction performance of a single model. The weight matrix, serving as a “neural synapse”, can adjust the contribution degrees of the two models in real-time according to the local feature characteristics of the input data, avoiding the blindness of fixed fusion weights.

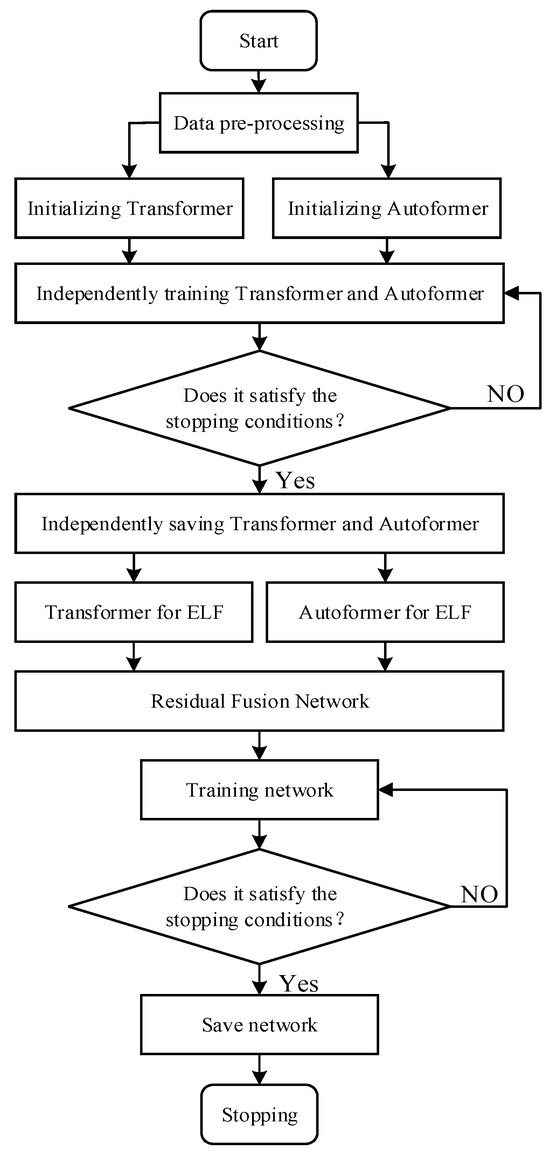

The ELF process of ATRNF is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the ATRFN for ELF.

- (1)

- The original electricity load data was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets, followed by normalization processing.

- (2)

- The Transformer and Autoformer were trained separately and saved independently.

- (3)

- ELF was conducted using Transformer and Autoformer, respectively.

- (4)

- The prediction results were fed into a residual fusion network for training.

- (5)

- The final trained ATRFN was employed as the ultimate ELF model.

3. Results and Discussion

The ELF experiment in this study was conducted on a computer operating Windows 11, with an i5-12600KF CPU and 32 GB of RAM, and an RTX 3080Ti GPU. The development environment was PyCharm 2021.3.1, with Python version 3.7, PyTorch 1.13, and CUDA 11.6.

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the robustness of the ATRNF model proposed in this study, MSE, MAE, and MAPE were employed as evaluation metrics. The calculations for these three metrics are presented in Equations (27), (28) and (29), respectively.

where m is the total sample size.

3.2. Univariate Electricity Load Forecasting

In the univariate STELF experiment, the dataset is sourced from ref. [40], a publicly available benchmark provided by the Electrician Mathematical Contest in Modeling sponsored by the Chinese Society for Electrical Engineering, which has been extensively employed in previous studies on short-term load forecasting. The data are recorded at a 15 min sampling frequency over a multi-year horizon, providing a representative basis for evaluating forecasting accuracy. Prior to the experiment, the data were divided into training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 7:1:2. Specifically, historical 7-day electricity load data were used as input to predict the electricity load on the 8th day.

The feasibility and advantages of the ATRNF for STELF were investigated through a comparative analysis with Autoformer [28], Informer [25], Transformer [24], Reformer [27], LSTM [19], and BiLSTM [41]. MSE, MAE, and MAPE are employed to comprehensively assess the robustness of these predictive models. The selection of parameters for all the models are presented in Table 1. It is worth noting that the input dimensions were set according to the specific problem addressed in this study, ensuring that all algorithms use the same input size. Moreover, the parameters of the compared algorithms are set as consistently as possible to ensure a fair comparison. For example, the batch size and learning rate are set to the same values. Some parameters differ among models to maintain fairness; for instance, models with fewer parameters require a longer number of training epochs, whereas more complex models need fewer training epochs. In this study, the number of training epochs is set to three times the iterations required for the loss function to essentially converge. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters selection for all comparison STELF models.

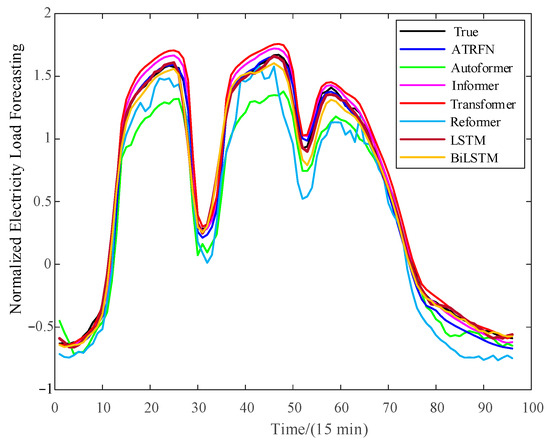

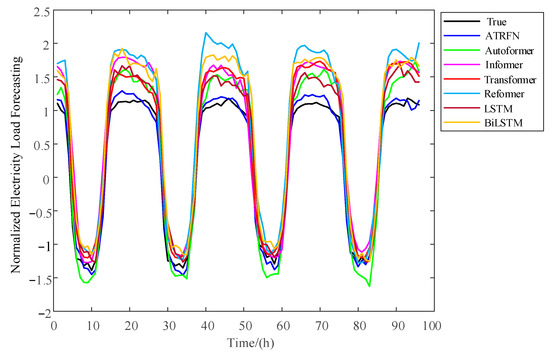

Figure 3 presents the prediction curves of seven different forecasting models for univariate STELF.

Figure 3.

Forecast results of different forecasting models for 24 h.

As shown in Figure 3, compared with the true load curve, the prediction results of Autoformer and Reformer models exhibit the largest deviation and the lowest degree of fitting, with their forecasted load curves showing significant irregular fluctuations and being lower than the true load prediction curve. Next, Transformer and Informer models can reasonably approximate the trend of the true load curve, but their overall predicted values are higher than the true load curve, and the forecasted load curves are overall smooth. The prediction curves of ATRFN, LSTM [19], and BiLSTM [35] fit closely with the actual load curve.

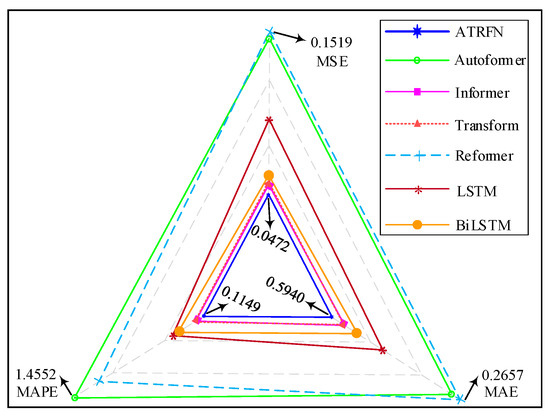

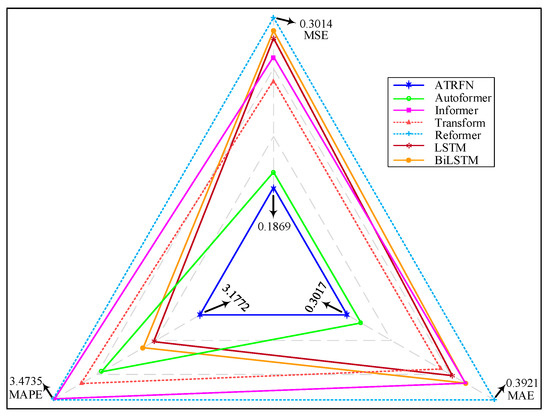

The calculation results of three metrics, MSE, MAE, and MAPE, for the seven STELF models are presented in Table 2. To further illustrate these differences in a more intuitive manner, the results are also visualized in Figure 4, where the relative performance of each model across the three metrics can be clearly observed.

Table 2.

Evaluation metrics results for univariate predictions of all models.

Figure 4.

The univariate prediction visualization results for all model evaluation metrics.

As presented in Table 2 and Figure 4, the proposed ATRFN model delivers the best predictive accuracy among all benchmarks. Its MSE, MAE, and MAPE reach 0.0472, 0.1149, and 0.5940, respectively, representing the lowest values across all models. Com-pared with the Transformer, which records MSE and MAE of 0.0552 and 0.1284, ATRFN achieves further reductions of 14.49% and 10.51%, underscoring its superior capability in minimizing both absolute and relative errors. Informer and BiLSTM also yield competitive results but still exhibit higher MAPE values, indicating weaker control of relative deviations. By contrast, Autoformer and Reformer show the poorest performance, with all three error metrics substantially larger than those of ATRFN, particularly in MAPE, where their errors are more than twice as high. These findings consistently demonstrate that ATRFN offers enhanced accuracy and robustness over existing approaches.

Combining the load forecasting curves in Figure 3 and the metric calculation results in Table 2, the ATRFN prediction model proposed in this paper demonstrates the highest STELF accuracy and can truly reflect the fluctuation trends of power loads. This superior performance may be attributed to ATRFN dynamically fusing the advantages of Transformer and Autoformer through adaptive residual correction. Although Autoformer performs poorly in univariate load forecasting, ATRFN’s dynamic residual fusion mechanism adaptively combines the outputs of Transformer and Autoformer, preferentially selecting the Transformer model with smaller validation errors as the main feature backbone to ensure ATRFN’s baseline performance, while using Autoformer for residual correction to improve prediction accuracy. Additionally, ATRFN’s prediction performance outperforms that of single Transformer and Autoformer models, validating the effectiveness of the model fusion strategy proposed in this paper.

3.3. Multivariate Electricity Load Forecasting

To further verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed ATRFN model, this subsection conducts multivariate STELF experiments. The dataset for the multivariate STELF experiments in this subsection is the Electricity dataset publicly available at https://github.com/thuml/Autoformer (accessed on 10 June 2025) by the authors of Autoformer. The dataset spans from 1 July 2016, to 2 July 2019, with a sampling interval of 1 h, containing load data from 321 customers. The data processing in this subsection is consistent with that in Section 3.2, where the input features are the historical loads of 321 customers, and the target output is the loads of 321 customers—specifically, using the historical 7-day electricity load data of 321 customers to predict their future 4-day electricity loads. In the multivariate prediction experiments, the input sequence length of all models was modified to 168 (7 days), with all other parameters remaining consistent with those in Table 1. In addition, the dataset partitioning strategy in the multivariate experiments follows the same 7:1:2 ratio for training, validation, and test sets as in the univariate experiments. Figure 5 shows the load forecasting curve for the future 96 h (4 days) of a randomly selected customer from the 321 customers.

Figure 5.

Forecast results of different forecasting models for 96 h.

As shown in Figure 5, the load forecasting curve of ATRFN is closest to the true load curve, capable of comprehensively capturing the changing trends of electricity loads. Especially in the trough phase, although ATRFN’s predicted values are lower than the true values, its forecasting curve accurately tracks the inflection points of load decline and rebound, with significantly better trend consistency than other models.

In the peak phase, all models exhibit a common bias where predicted values are higher than true values. The peak curve of Autoformer fluctuates more than that of Transformer, but its overall predicted values are smaller than those of Transformer. Among the seven STELF models, ATRFN’s peak curve is smoother with the smallest peak error, and its predicted waveform has the highest degree of matching with the true load curve in terms of upward slope and duration. This may be because ATRFN balances the sensitivity of Autoformer to short-term fluctuations and the stability of Transformer to long-term trends through its dynamic residual fusion mechanism, effectively avoiding the biases of single models and demonstrating more robust trend-fitting capabilities in load trend forecasting.

Figure 5 in this study presents the results of three highly representative days. During regular working periods, all compared algorithms exhibit relatively low prediction errors. However, for peak and valley periods, many of the baseline algorithms tend to produce larger prediction errors when the actual load exhibits pronounced peaks and valleys. In other words, regarding the overall global trend of STELF, the proposed ATRFN achieves the highest accuracy. This is because ATRFN fuses two networks with distinct characteristics, enabling it to capture both the temporal patterns of working periods and the operational characteristics during rest periods.

Table 3 presents the mean values of three metrics for seven STELF models in the multivariate forecasting experiment. To facilitate a more intuitive comparison across the three metrics, Figure 6 visualizes these results simultaneously. In addition, inference time (milliseconds, ms per batch) and CPU peak memory usage (MB) are reported to assess the computational efficiency of each model in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics results for multivariate predictions of all models.

Figure 6.

The multivariate prediction visualization results for all model evaluation metrics.

From the results presented in Table 3 and Figure 6, it is evident that the proposed ATRFN model achieves the best overall performance across three evaluation metrics. Specifically, ATRFN attains the lowest MSE (0.1869) and MAE (0.3017), significantly outperforming both traditional recurrent models such as LSTM and BiLSTM. Autoformer follows closely, with MSE and MAE values of 0.1972 and 0.3103. Compared to Autoformer, the MSE and MAE of ATRFN are reduced by 5.22% and 2.77%, respectively. From the perspective of MAPE, the proposed ATRFN achieves the optimal value of 3.1772, which is 2.85% lower than the LSTM (3.2704). The dominance of ATRFN across three evaluation metrics further validates the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed residual fusion strategy in STELF tasks.

Interestingly, in Table 3, Autoformer, Transformer, and Informer exhibit lower MSE and MAE but higher MAPE compared to LSTM and BiLSTM. Combined with Figure 6, this discrepancy may arise from their more accurate predictions in data segments with high amplitude and strong correlation, while being sensitive to prediction deviations in low-amplitude data points. This might be due to overlooking subtle fluctuations of low-signal-to-noise variables, leading to larger relative errors. In contrast, LSTM and BiLSTM rely on recurrent gate mechanisms, which prioritize local temporal continuity and stability, making them perform better in low-amplitude scenarios where relative error penalties are less severe.

In Table 3, in terms of computational cost, BiLSTM and Transformer achieve the fastest in inference time (5.34 ms/batch), while ATRFN has the longest inference time (7.30 ms/batch) due to the overhead of running two base models with a residual fusion module. Regarding memory usage, LSTM and BiLSTM consume the largest CPU memory (about 1.2 GB) because of recurrent state storage, whereas ATRFN, Transformer, Autoformer, Informer and Reformer require about 27 MB, representing highly efficient memory usage. Therefore, the experiment results indicate that ATRFN trades slightly longer inference time for significantly improved predictive accuracy while maintaining minimal memory consumption, demonstrating a favorable balance between performance and computational cost.

3.4. Ablation Study on Fusion Methods

A comparative study is conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of ATRFN by means of a comparison with two simpler fusion strategies: simple averaging and fixed linear fusion. In the simple averaging approach, the predictions from the Autoformer and Transformer models are combined with equal weights. In the fixed linear fusion, the contributions of the two models are combined using pre-determined constant weights. The quantitative results on the test set for the Electricity dataset are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Evaluation metrics results for fusion methods.

From Table 4, ATRFN achieves the lowest MSE (0.1869) and MAE (0.3017) among the three approaches, indicating superior absolute prediction accuracy. For relative error, ATRNF records a MAPE of 0.31772, which is slightly smaller than fixed linear fusion (2.9837). This difference may stem from the sensitivity of MAPE to small true values: when the ground-truth load is close to zero, even minor absolute deviations are amplified in percentage form. Since ATRFN focuses on accurately capturing temporal variations and peak behaviors, it may introduce slightly larger percentage errors on low magnitude samples. In contrast, simple averaging performs worse across all metrics, demonstrating the limitations of static equal weighting.

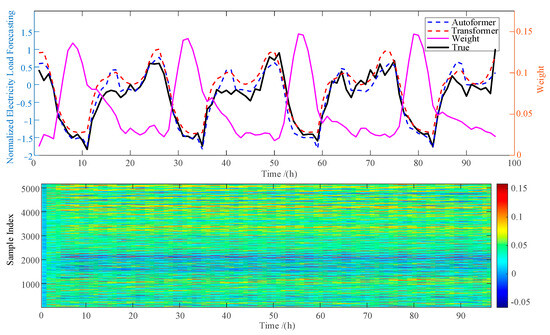

To further illustrate how ATRFN’s adaptive fusion mechanism operates, the adaptive weight matrix corresponding to a randomly selected customer from the Electricity dataset is visualized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The adaptive weight visualization results for ATRNF.

From Figure 7, the upper panel shows the weight matrix of a single test sample, revealing how ATRFN adjusts the contribution of each base model at a specific time step. A clear pattern can be observed that TRFN does not depend on fixed contributions from the Autoformer and Transformer sub-models. Instead, it dynamically adjusts the fusion weights at each time step based on the local behavior of the load series. A notable observation is that during peak-load periods, the model assigns smaller weights to the Transformer branch, suggesting reduced reliance on Transformer predictions when the load series undergoes abrupt surges. In contrast, during low-load or valley periods, the Transformer receives higher weights, reflecting its comparative advantage in modeling smoother or low-amplitude segments.

The lower panel, which aggregates weights over all samples, demonstrates that these adaptation patterns are not incidental. The weight distribution still shows systematic correlations with the typical daily load profile, confirming that ATRFN learns a stable and interpretable fusion strategy across the dataset. This consistency validates the model’s ability to capture the complementary strengths of the two backbone predictors in a data-dependent manner.

Overall, this ablation analysis verifies that the adaptive weighting mechanism in ATRFN plays a crucial role in achieving high prediction accuracy. In contrast, simple averaging or fixed linear fusion fails to capture the nuanced temporal variations and feature-dependent patterns inherent in load data, leading to inferior prediction performance.

3.5. Discussion

Through univariate prediction experiments and multivariate prediction experiments, the ATRFN model proposed in this study is verified to have high prediction accuracy in ELF. The ATRFN model realizes the synergy of prediction results between Transformer and Autoformer through a validation-set error-driven dynamic weighted residual mechanism, and its advantages can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Unlike traditional feature fusion that requires alignment and reconstruction of the internal architectures of Transformer and Autoformer, ATRFN directly acts on the result outputs of the dual models through RFN, achieving fusion in a lightweight manner of “backbone screening and residual correction”.

- (2)

- The ATRFN proposed in this paper deepens the fusion granularity to the feature dimension, dynamically screening the outputs of the dual models through an adaptive weight matrix. This approach retains the long-range trend features of Autoformer while enhancing the local mutation features to which Transformer is sensitive.

- (3)

- The ATRFN model follows the “superior model priority” principle, using the output of the model with smaller validation set errors as the feature backbone, while the output of the other model is used for detail correction in the form of residuals. This design maintains the stability of gradient propagation through the identity mapping property of residual connections and avoids the “redundant information interference” caused by directly concatenating the output features of the dual models, thereby improving the utilization efficiency of the feature space.

Although the ATRFN model proposed in this study can break through the limitations of single models in time-series modeling and improve the prediction accuracy of ELF, the model still has the following limitations:

- (1)

- The model’s selection of the backbone model and weight initialization are highly dependent on validation set errors. If the validation set fails to fully reflect the true distribution of the target data, it may lead to misjudgment of the backbone model and deviations in weight initialization.

- (2)

- The calculation of the weight matrix is based on global feature statistics without incorporating time-step-level contextual information, which may cause a decline in correction gains during certain periods.

- (3)

- The residual correction mechanism implicitly assumes that “dual-model errors are independent of each other,” but in reality, there may be a risk of systematic co-bias. When both Transformer and Autoformer have large prediction errors simultaneously, residual correction may fail due to the lack of effective signals.

Aiming at the above shortcomings of the ATRFN model, future research can be carried out in the following aspects.

(i) A meta-learning framework can be introduced to train the backbone selector, enabling it to learn meta-knowledge about data distribution patterns and model adaptation from historical tasks, thereby mitigating the impact of validation set distribution bias; (ii) Temporal dynamic feature encoders can be embedded into weight calculation to achieve adaptive generation of time-specific weights; (iii) An adversarial learning framework can be constructed to enforce orthogonalization of error outputs from dual models, guiding the models to learn complementary error patterns and enhancing the effectiveness of residual signals; (iv) Deep integration of the internal structures of Transformer and Autoformer can be explored; (v) Organic integration of more ELF prediction models can be considered.

4. Conclusions

This paper proposes a short-term electricity load forecasting model that fuses the outputs of Transformer and Autoformer based on an validation set error driven residual network. Forecasting results on two real-world electricity load datasets show that the proposed forecasting model can accurately capture the fluctuation trends of loads and has smaller forecasting errors than single forecasting models. The characteristics of the proposed model can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The proposed fusion model avoids joint optimization of the internal architectures of the dual models through an independent pretraining and result-layer fusion strategy, reducing joint training overhead and maximizing the retention of the respective advantages of Transformer and Autoformer.

- (2)

- The proposed fusion model employs a dynamic weight matrix as an interaction bridge between Transformer and Autoformer, which can analyze the local feature characteristics of input data and allocate differentiated weights to the feature fusion outputs of the dual models, effectively mitigating the blindness of fixed weights.

- (3)

- By screening the better-performing model from the validation set as the feature backbone and using the other model to supplement and correct local details in the form of residuals, the fusion model provides a baseline performance guarantee. In univariate prediction experiments, the MSE and MAE of the proposed fusion model are 14.49% and 10.51% lower than those of the Transformer model, respectively. In multivariate prediction experiments, the MSE and MAE of the proposed fusion model are 5.22% and 2.77% lower than those of the Autoformer model, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z., K.Z., G.L. and J.Y.; experiments, L.Z. and K.Z.; data analysis, M.W., G.C. and H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z. and G.L.; writing— review and editing, L.Z.; chart, M.W., G.C. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd. (210000KC24060044).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Lukun Zeng, Kaihong Zheng, Guoying Lin, Jingxu Yang, Mingqi Wu, and Guanyu Chen were employed by the CSG Digital Power Grid Group Co., Ltd. Author Haoxia Jiang was employed by the Guangzhou Power Electrical Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABPE | Average absolute prediction errors |

| ATRFN | Autoformer-Transformer residual fusion network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long short-term memory network |

| CNNs | Convolutional neural networks |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory network |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| STELF | Short-term electricity load forecasting |

References

- Islam, U.; Ullah, H.; Khan, N.; Saleem, K.; Ahmad, I. AI-Enhanced Intrusion Detection in Smart Renewable Energy Grids: A Novel Industry 4.0 Cyber Threat Management Approach. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2025, 50, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Srinivasan, C.; Balavignesh, S. Enhancing grid integration of renewable energy sources for micro grid stability using forecasting and optimal dispatch strategies. Energy 2025, 322, 135572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Ding, Y.; Dang, Y.; Ye, L. Forecasting the electric power load based on a novel prediction model coupled with accumulative time-delay effects and periodic fluctuation characteristics. Energy 2025, 317, 134518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, J.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.G. Multi-Granularity Autoformer for long-term deterministic and probabilistic power load forecasting. Neural Netw. 2025, 188, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Nie, X.; Yang, J.; Zha, L.; Li, G.; Li, H. A power load forecasting method in port based on VMD-ICSS-hybrid neural network. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Yang, X. Short-and medium-term power load forecasting model based on a hybrid attention mechanism in the time and frequency domains. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 278, 127329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Heleno, M.; Zhang, W.; Sun, K.; Garcia, L.R.; Hong, T. A Cross-Dimensional Analysis of Data-Driven Short-Term Load Forecasting Methods with Large-scale Smart Meter Data. Energy Build. 2025, 344, 115909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Muhammad, Y.; Jadoon, I.; Awan, S.E.; Raja, M.A.Z. Leveraging LSTM-SMI and ARIMA architecture for robust wind power plant forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyl, S.; Bergmeir, C.; Dokumentov, A.; Long, X.; Wibowo, E.; Schmidt, D. Local and global trend Bayesian exponential smoothing models. Int. J. Forecast. 2025, 41, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guan, L.; Wang, Z.; Yao, R.; Guan, X. A double-layer forecasting model for PV power forecasting based on GRU-Informer-SVR and Blending ensemble learning framework. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 172, 112768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, B.; Li, C. Hybrid short-term load forecasting using CGAN with CNN and semi-supervised regression. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Chen, T.; Ni, H.; Shi, Q. Intra and inter-series pattern representations fusion network for multiple time series forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 175, 113024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, S.G.K.; Ozbay, B.K.; Dal, B. Interpretable building energy performance prediction using xgboost quantile regression. Energy Build. 2025, 344, 115815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Meera, P.S.; Lavanya, V.; Hemamalini, S. Brown bear optimized random forest model for short term solar power forecasting. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, S.; Nie, Y. Multivariate rolling decomposition hybrid learning paradigm for power load forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pu, H.; Sun, D.W. Efficient extraction of deep image features using convolutional neural network (CNN) for applications in detecting and analysing complex food matrices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 113, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Hybrid Multi-Branch Attention–CNN–BiLSTM Forecast Model for Reservoir Capacities of Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant. Energies 2025, 18, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, M.; Rozinaj, G.; Vargic, R. Using crafted features and polar bear optimization algorithm for short-term electric load forecast system. Energy AI 2025, 19, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Su, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Remaining useful life prediction for lithium-ion batteries in highway electromechanical equipment based on feature-encoded LSTM-CNN network. Energy 2025, 323, 135719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, D.; Yang, C.; Wang, B.; Duan, B.; Wang, Y. Model construction and multi-objective performance optimization of a biodiesel-diesel dual-fuel engine based on CNN-GRU. Energy 2024, 301, 131586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zeng, J.; Wang, H.; Ding, H.; Wang, H.; Bi, Y. Using acoustic emission technique for structural health monitoring of laminate composite: A novel CNN-LSTM framework. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 309, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.C.; Hsu, H.W.; Chen, K.S.; Wen, C.Y. A hybrid CNN-GRU based probabilistic model for load forecasting from individual household to commercial building. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.L.; Wen, X.H.; Yan, W.; Ji, H.Z.; Xiao, J.X.; Li, X.G.; Meng, S.L. Ensemble learning based on bi-directional gated recurrent unit and convolutional neural network with word embedding module for bioactive peptide prediction. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ning, X.; He, W.; Cai, W. FefDM-Transformer: Dual-channel multi-stage Transformer-based encoding and fusion mode for infrared–visible images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 277, 127229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Dai, Y.; Ren, T.; Leng, M. Short-time Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Based on Informer Model Integrating Attention Mechanism. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 178, 113345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T. Data-driven modeling of 600 MW supercritical unit under full operating conditions based on Transformer-XL. ISA Trans. 2025, 158, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, Z.; Mu, W. Reformer: Re-parameterized kernel lightweight transformer for grape disease segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 265, 125757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Liu, N.; Shi, J.; Ding, Y. Tackling the duck curve in renewable power system: A multi-task learning model with iTransformer for net-load forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 326, 119442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, H. Multi-step electric vehicles charging loads forecasting: An autoformer variant with feature extraction, frequency enhancement, and error correction blocks. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, R.; Li, M.; Zhou, C.; Ding, N. Research on the application of an improved Autoformer model integrating CNN-attention-BiGRU in short-term power load forecasting. Evol. Syst. 2025, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zheng, T.; Hu, J.; Zhang, K. A transformer-based method of multienergy load forecasting in integrated energy system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Dong, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Short-term load forecasting based on CEEMDAN and Transformer. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 214, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhang, D. An adaptive deep-learning load forecasting framework by integrating transformer and domain knowledge. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 10, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ye, N.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Mumtaz, S.; Li, X. Meta-lstr: Meta-learning with long short-term transformer for futures volatility prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 265, 125926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; He, J.; He, J.; Feng, Q.; Bi, Y. Forecasting air quality index in yan’an using temporal encoded informer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommidi, B.S.; Teeparthi, K. A hybrid wind speed prediction model using improved ceemdan and autoformer model with auto-correlation mechanism. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 64, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Y.; Kucukdemiral, I. A comprehensive review on deep learning approaches for short-term load forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 114031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yuan, H.; Guo, F. Lithium-Ion Battery State of Health Estimation Based on Feature Recon-struction and Transformer-GRU Parallel Architecture. Energies 2025, 18, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Kong, X.; Su, J. A multi-strategy improved sparrow search algorithm and its application. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 55, 12309–12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Hou, D.; Sun, W.; Li, S. A short-term load forecasting method considering multiple factors based on VAR and CEEMDAN-CNN-BILSTM. Energies 2025, 18, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).