Research on the Mechanical Behavior of Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface in Salt Cavern Gas Storage Under Storage-Release Cycle

Abstract

1. Introduction

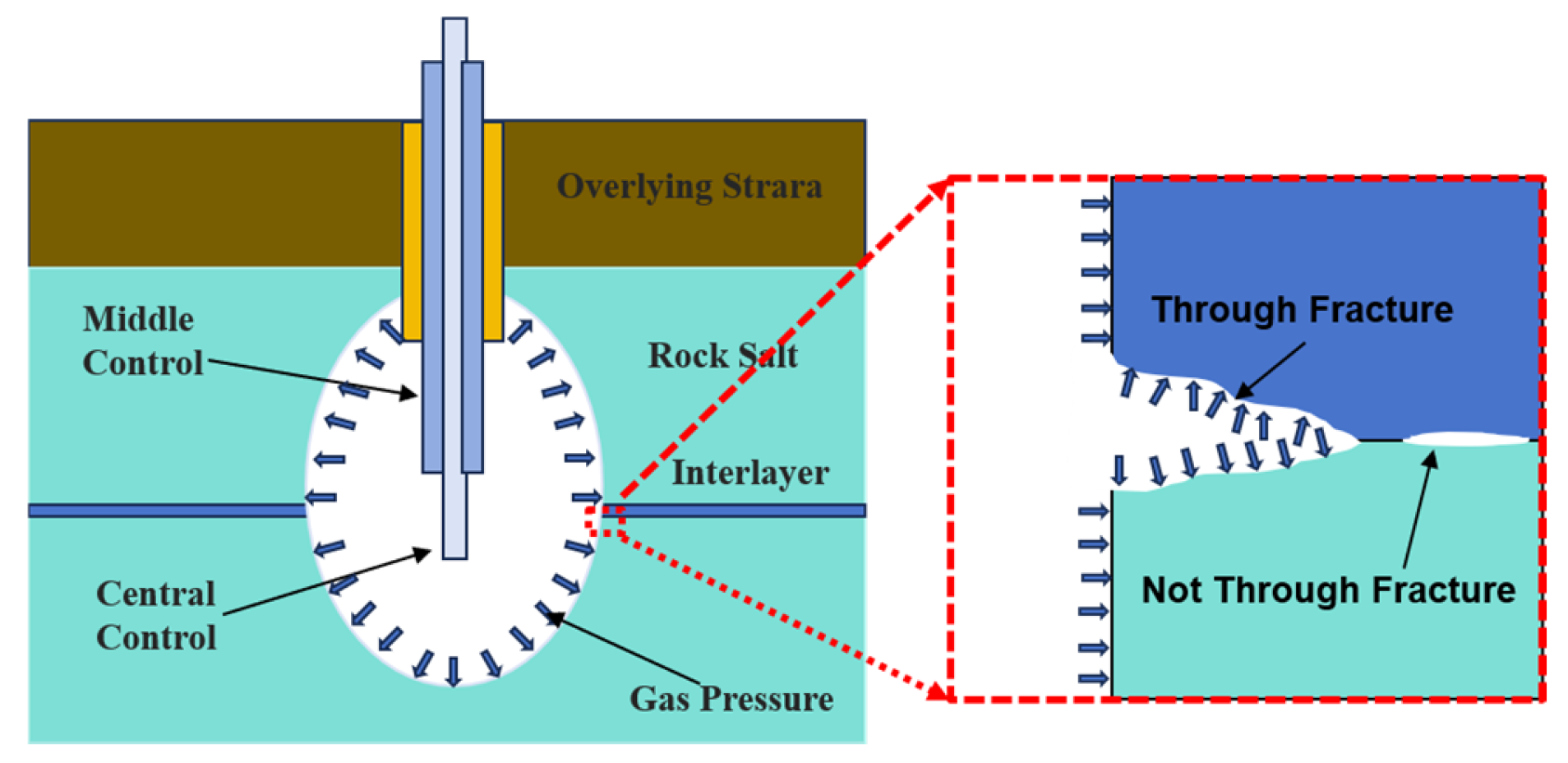

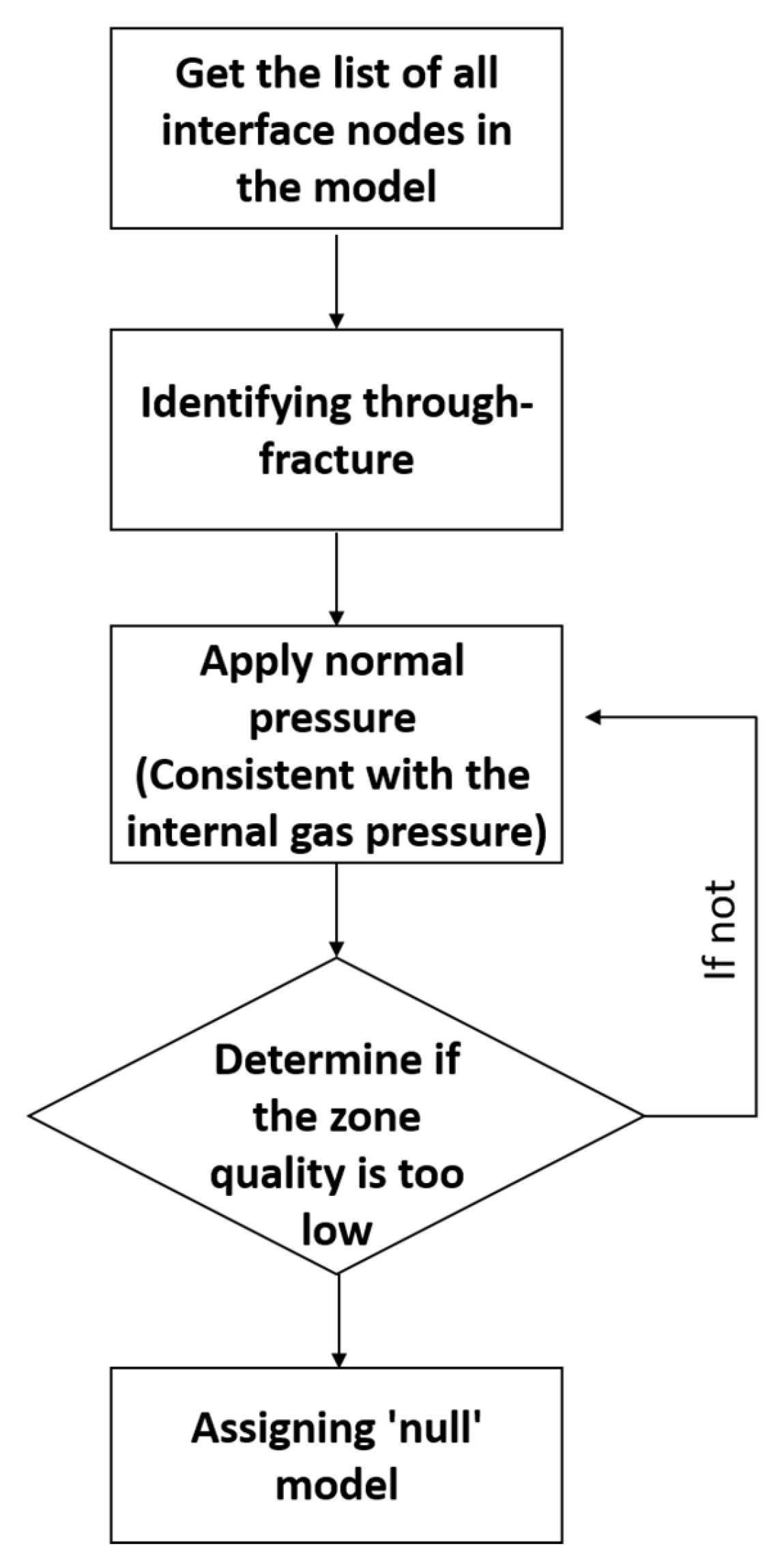

2. Simulation Method

2.1. Simulation Approach

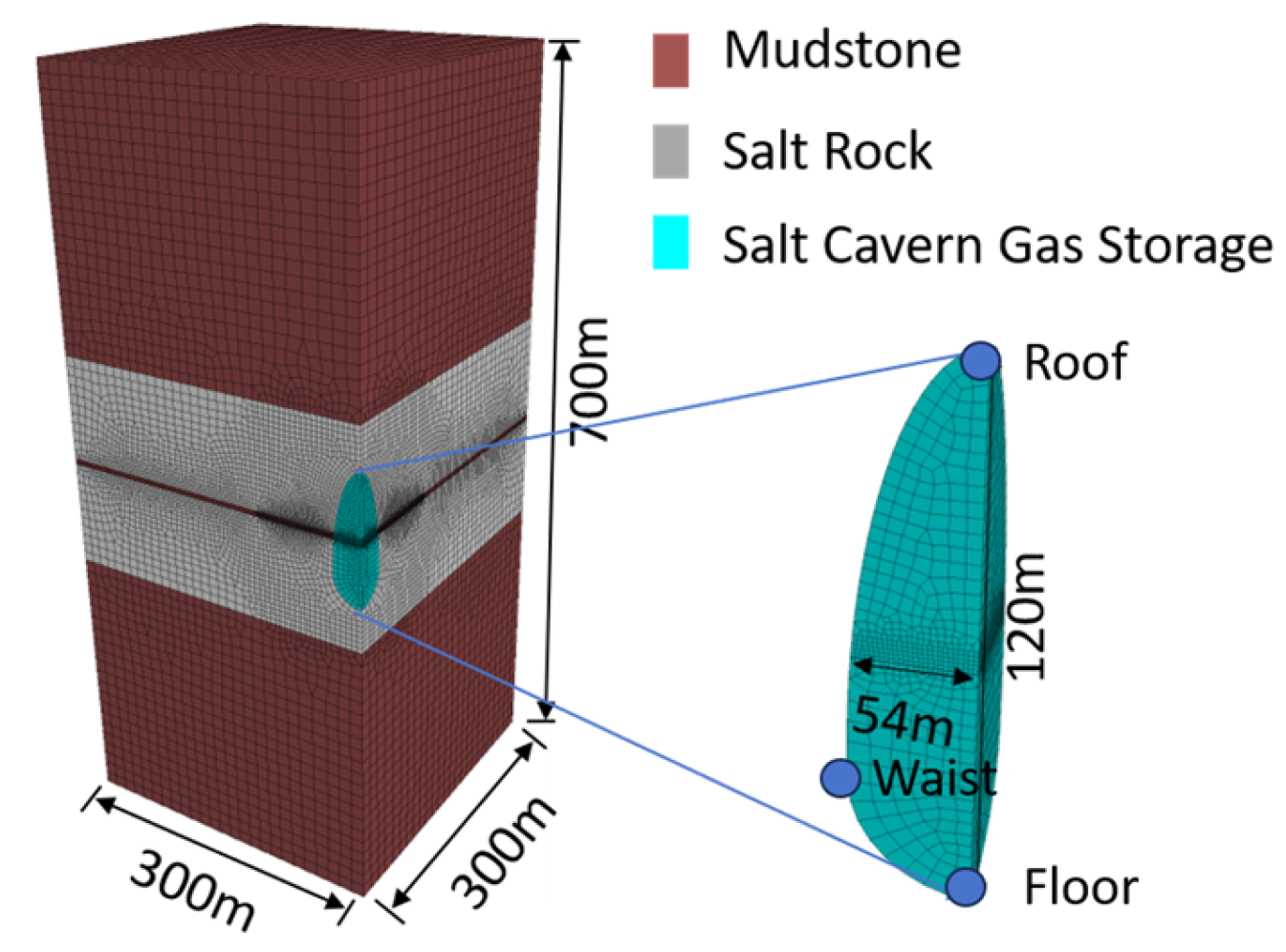

2.2. Geological Model

2.3. Selection of Constitutive Model and Calculation Parameters

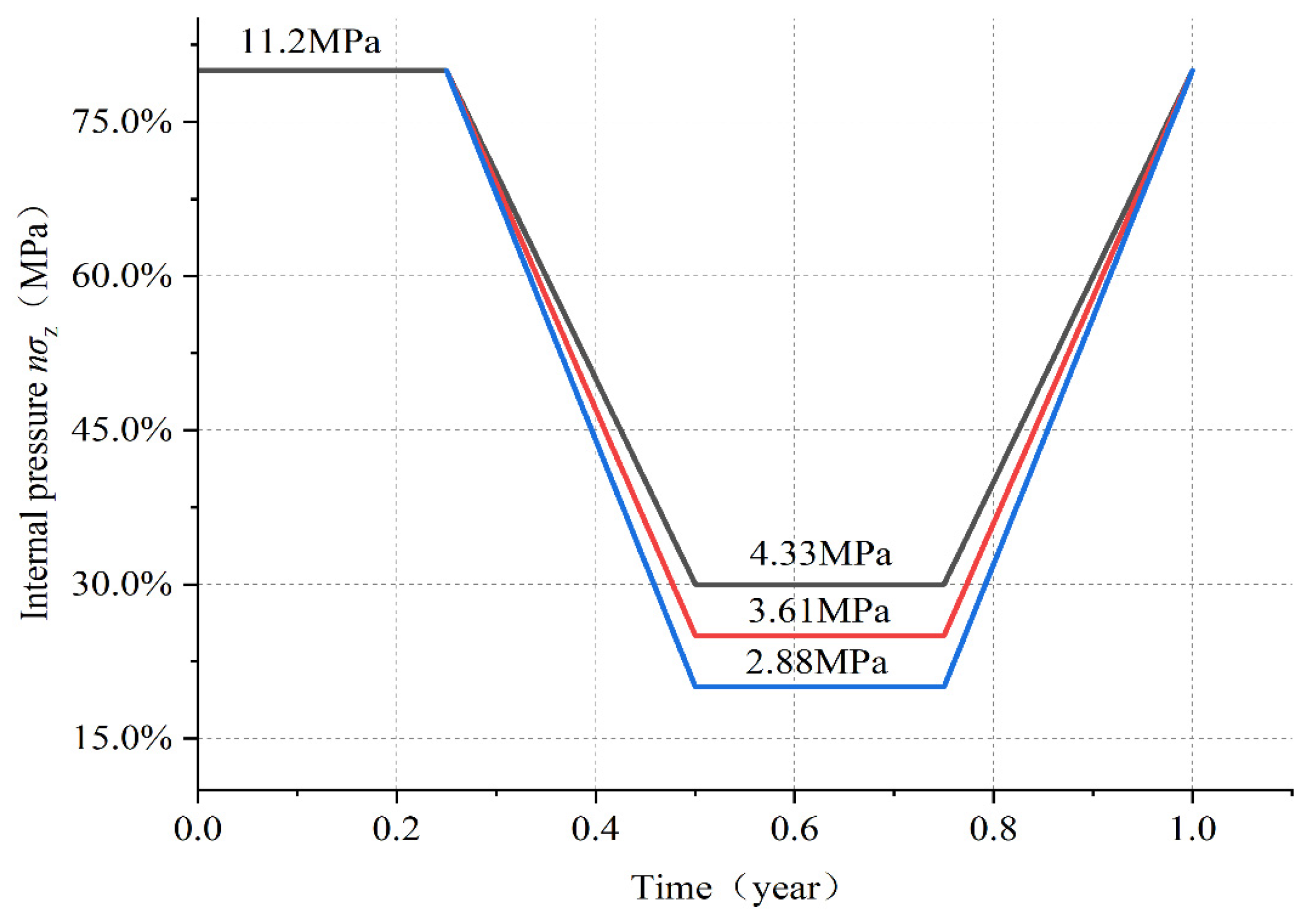

2.4. Operation Condition Design

3. Results and Discussion

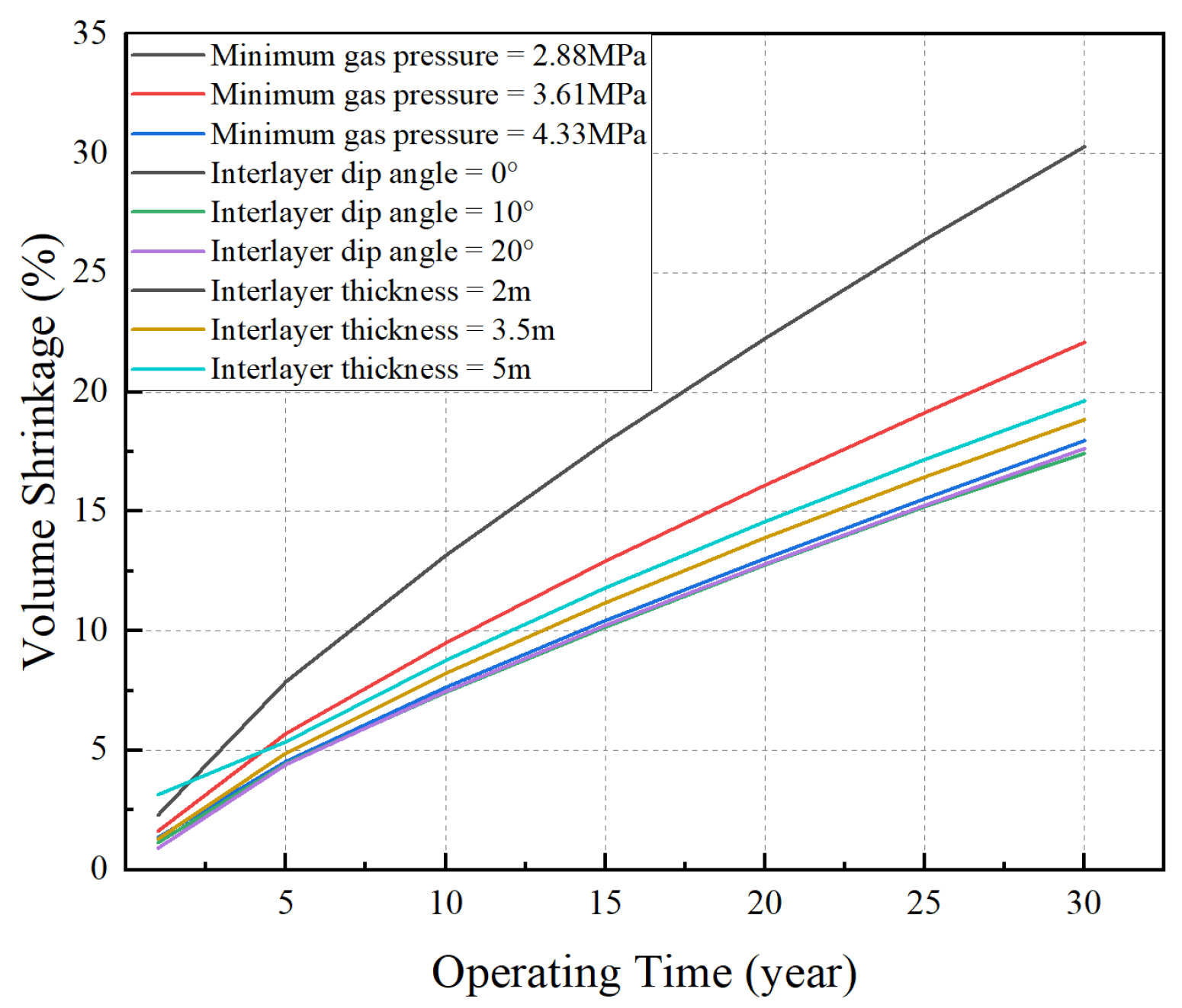

3.1. Volume Shrinkage Rate

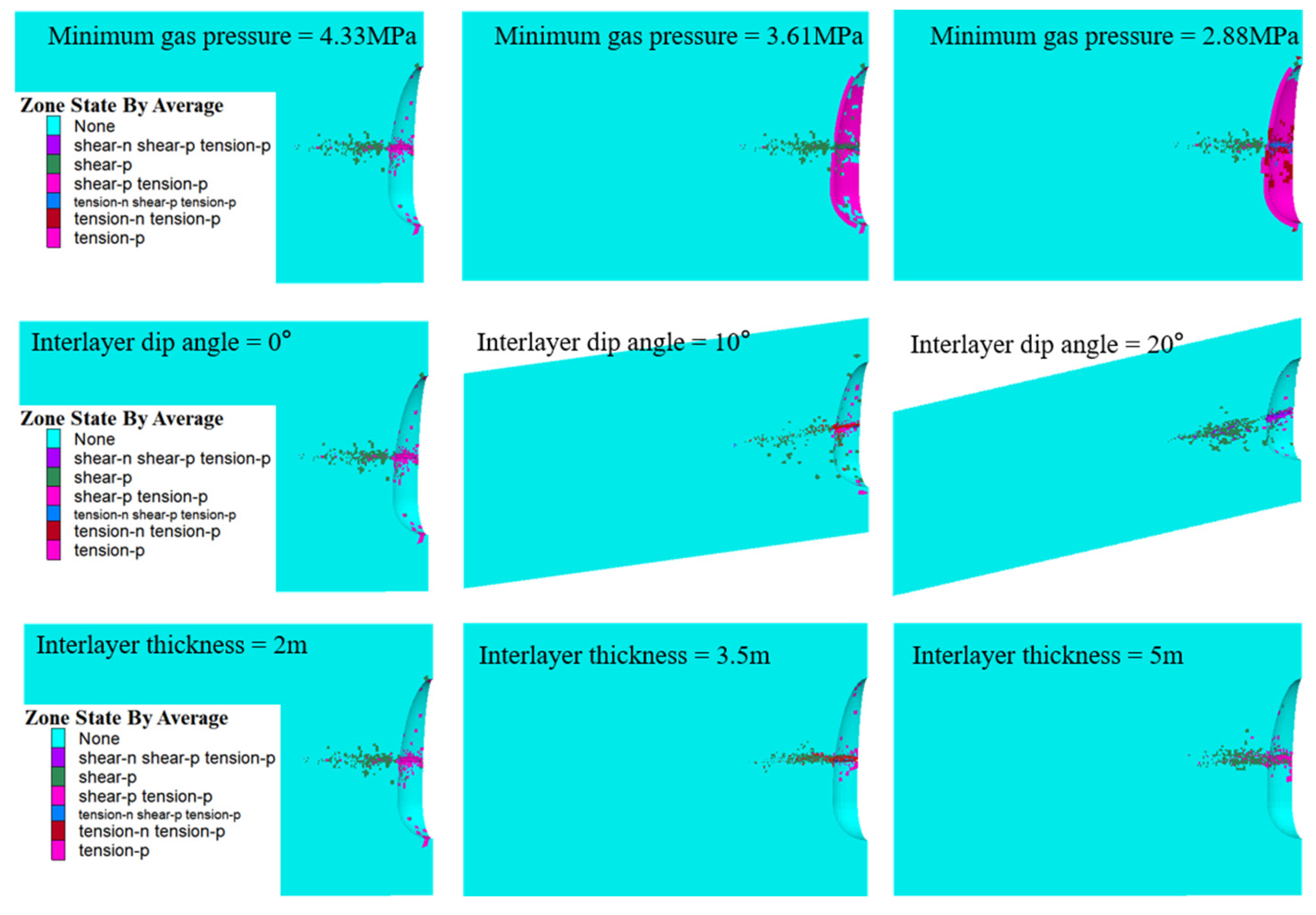

3.2. Volume of the Plastic Zone

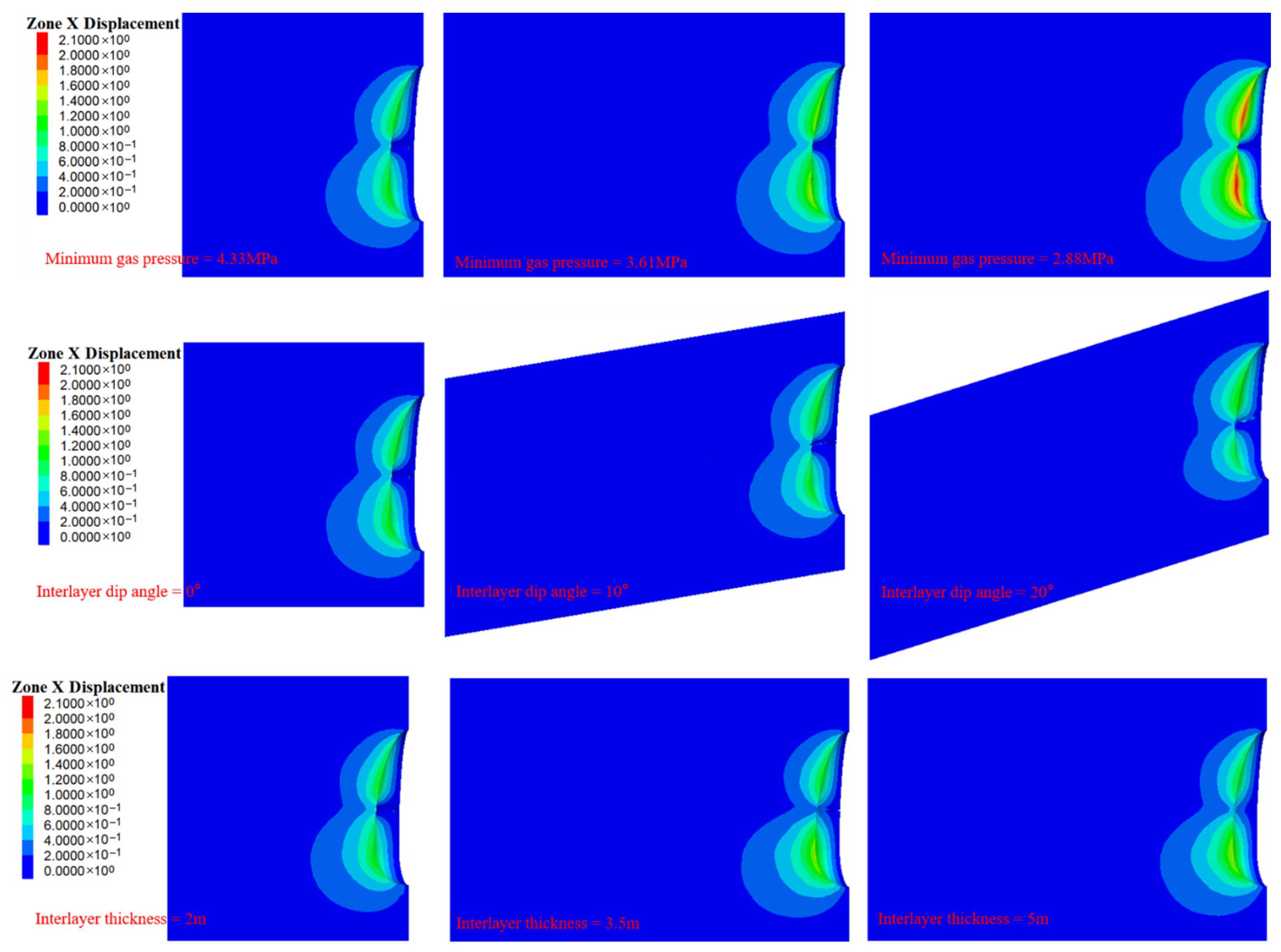

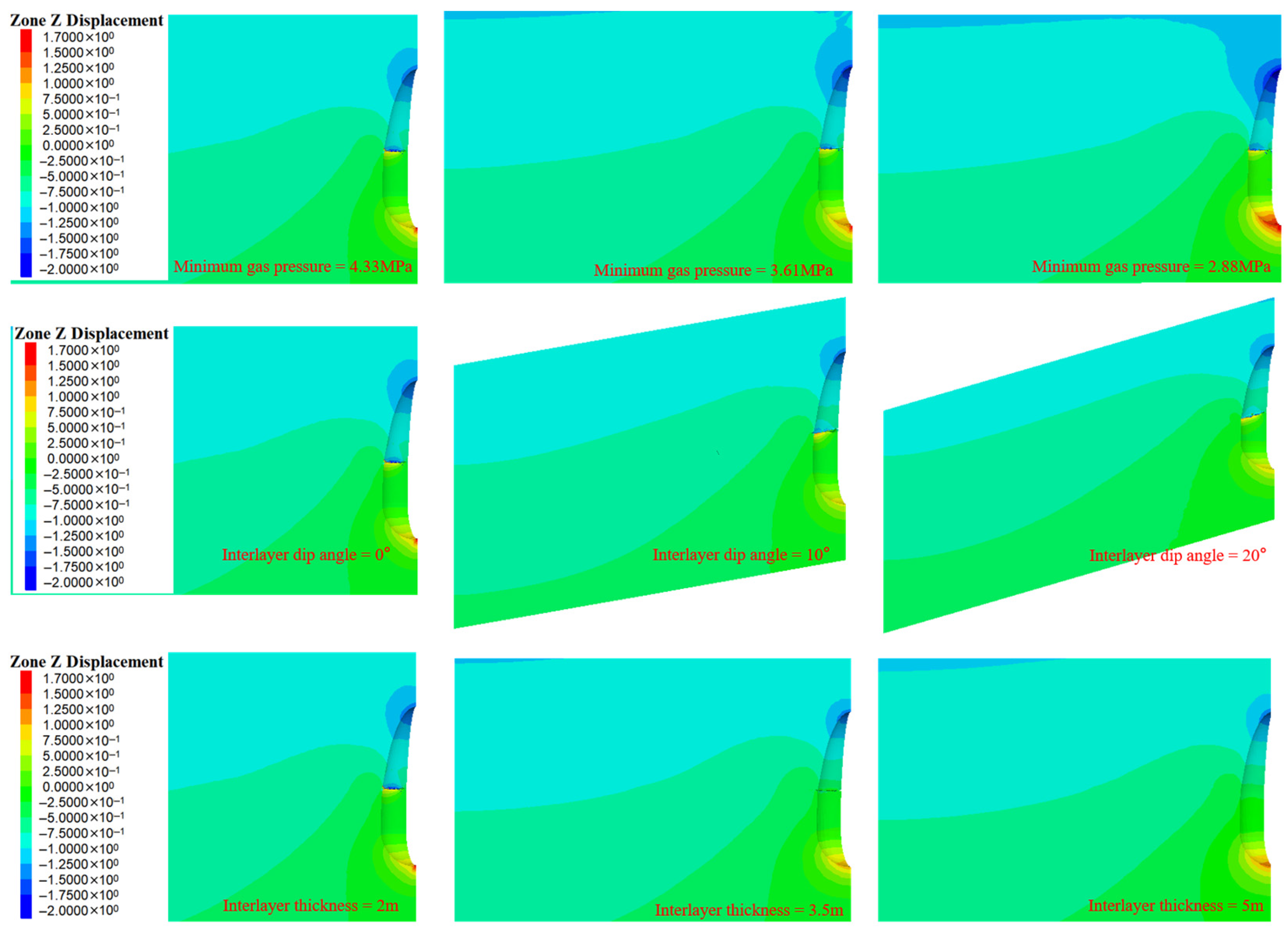

3.3. Maximum Displacement of the Cavity

3.4. Shear Stress at the Interlayer-Salt Interface

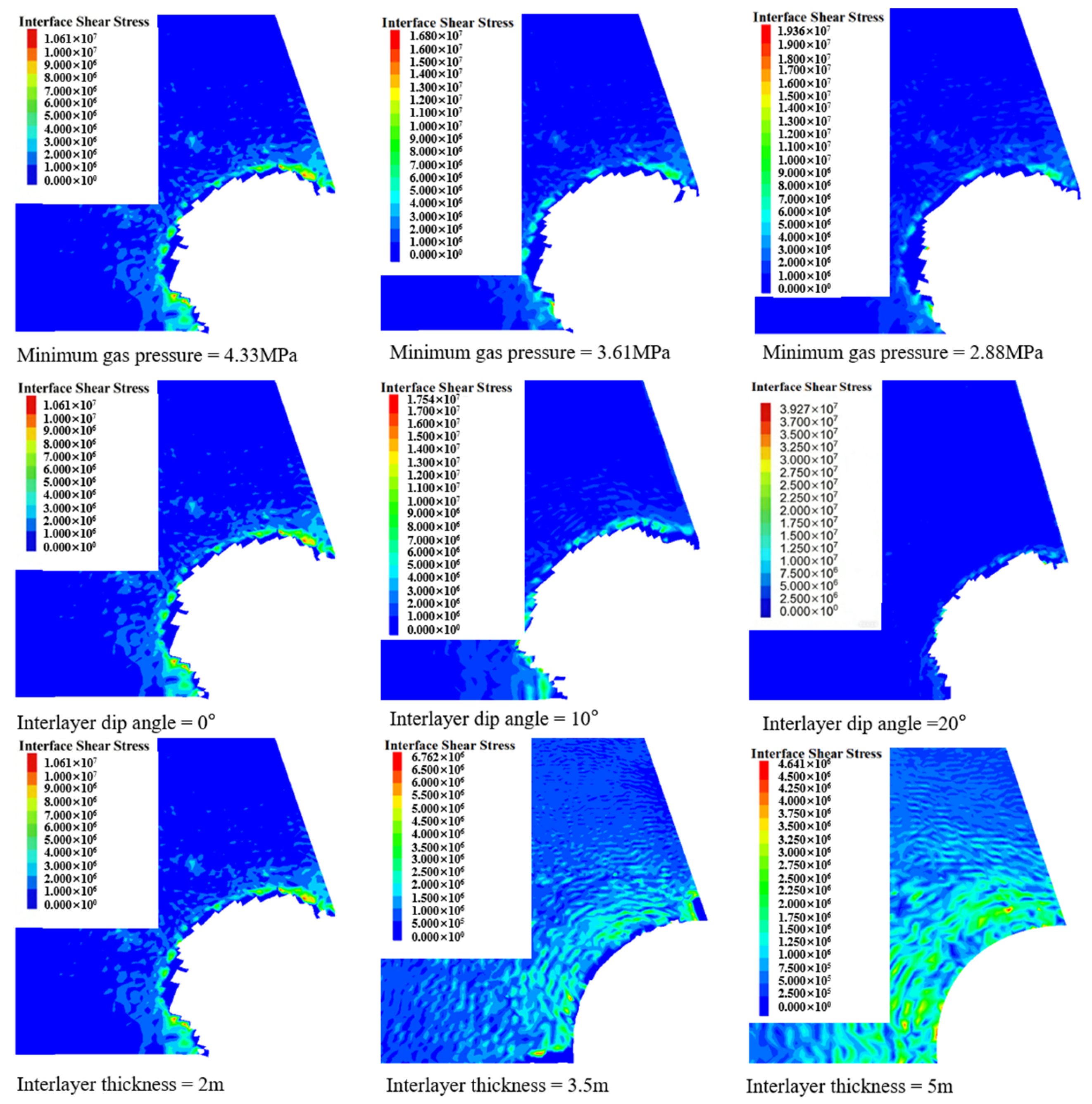

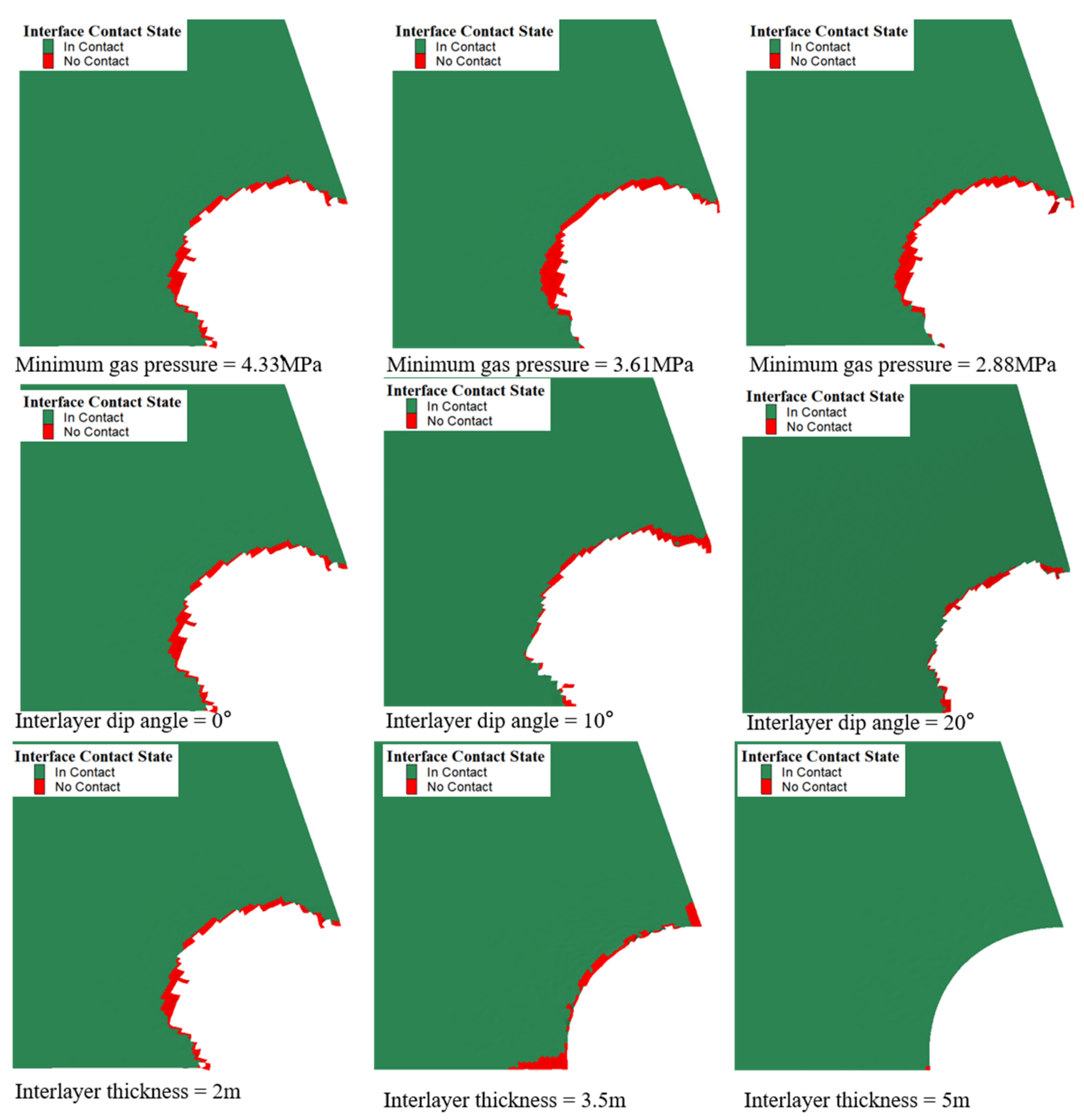

3.5. Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface Contact Condition

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the interface stability evaluation, as the minimum operating pressure decreases, the maximum shear stress at the interface shows a significant upward trend, and the interface fracture area also expands accordingly, exacerbating the risk of gas leakage within the cavity. Therefore, it is recommended to control the minimum operating pressure at more than 20% of the formation pressure to ensure the stable operation of the gas storage facility.

- (2)

- As the dip angle increases from 0° to 20°, the maximum shear stress at the interface increases, while the fracture area decreases. The area of the plastic damage zone at the interlayer increases, increasing the risk of gas leakage within the cavity. When the dip angle is 10°, the distribution of the plastic zone volume of the surrounding rock and the interface fracture area is most reasonable, resulting in the best overall stability of the cavity.

- (3)

- The interlayer thickness mainly regulates the flexibility and deformation coordination of the interface. The interlayer thickness can effectively weaken the maximum shear stress at the interface, and as the thickness increases, the fracture area decreases significantly. When the interlayer thickness is 3.5 m, it has a good inhibitory effect on fractures without increasing gas leakage, which is most beneficial to the sealing and stability of the gas storage facility.

- (4)

- From the perspective of overall cavity stability, operating pressure, interlayer inclination angle, and thickness jointly determine the long-term deformation and failure mode of the cavity, making their comprehensive control crucial. A higher minimum operating pressure can effectively reduce the cavity shrinkage rate (from 30.28% to 17.97%), reduce the tensile failure volume, and inhibit creep deformation; an appropriate inclination angle can optimize the stress on the surrounding rock, minimizing the volume of the plastic zone; and an appropriate interlayer thickness helps to disperse interfacial stress and stabilize the cavity structure. Therefore, in engineering design, the internal pressure level, interlayer geometric parameters, and operating regime should be rationally matched to achieve controllable cavity deformation, controllable interfacial stress, and long-term safe operation of the overall structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omri, A. An international literature survey on energy-economic growth nexus: Evidence from country-specific studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Shi, X. Creep deformation analysis of gas storage in salt caverns. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 139, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Chen, H. Theoretical and Technological Challenges of Deep Underground Energy Storage in China. Engineering 2023, 25, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, D.; Al Sahyouni, F.; Golfier, F.; Moumni, M.; Schoumacker, L. Evolution of Gas Permeability of Rock Salt Under Different Loading Conditions and Implications on the Underground Hydrogen Storage in Salt Caverns. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 691–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, S.R.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Patange, P.; Watson, M. A comprehensive review of the mechanisms and efficiency of underground hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Evaluation of Potential for Salt Cavern Gas Storage and Integration of Brine Extraction: Cavern Utilization, Yangtze River Delta Region. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 3275–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.R.; Pak, A.; Shad, S.; Mehrgini, B.; Razifar, M. Investigation of rock salt layer creep and its effects on casing collapse. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Ma, H.L.; Shi, X.L.; Yang, C.H.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.L.; Ding, S.; Daemen, J. Salt cavern gas storage in an ultra-deep formation in Hubei, China. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 102, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Lyu, C. Stability analysis of Pingdingshan pear-shaped multi-mudstone interbedded salt cavern gas storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ma, H.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X. Stability analysis of CAES salt caverns using a creep-fatigue model in Yunying salt district, China. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, J.; Jiang, D.; Daemen, J.J.K. Research on the Stability and Treatments of Natural Gas Storage Caverns with Different Shapes in Bedded Salt Rocks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 18995–19007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, J.; Daemen, J. Safety evaluation of salt cavern gas storage close to an old cavern. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2016, 83, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Yue, X.; Ba, J.; Ding, S. Study on the deformation and failure laws of surrounding rock under reduced roof thickness in Salt Cavern Gas Storage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, R.; Liang, X.; Huang, S.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Stability Evaluation of Horizontal Salt Caverns for Gas Storage in Two Mining Layers: A Case Study in China. Energies 2023, 16, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Wang, T.; Wang, D.; Xie, D.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, T.; Daemen, J. Integrity analysis of wellbores in the bedded salt cavern for energy storage. Energy 2023, 263, 125841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Wanyan, Q.; Li, K.; Gao, K.; Yue, X. Sensitivity analysis of operation parameters of the salt cavern under long-term gas injection-production. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Jiang, D.; Qiao, W.; Liu, E.; Zhang, N.; Fan, J. Investigation on the influences of interlayer contents on stability and usability of energy storage caverns in bedded rock salt. Energy 2021, 231, 120968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhao, K.; Liang, X.; Ma, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, K. Compaction and restraining effects of insoluble sediments in underground energy storage salt caverns. Energy 2022, 249, 123752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk prediction of gas hydrate formation in the wellbore and subsea gathering system of deep-water turbidite reservoirs: Case analysis from the south China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Huang, J.; Zhou, K.; Su, K.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Shi, X. Research of interlayer dip angle effect on stability of salt cavern energy and carbon storages in bedded salt rock. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, C.; Shi, X.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Daemen, J.J.K. Construction modeling and shape prediction of horizontal salt caverns for gas/oil storage in bedded salt. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 190, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ding, Z.; He, T.; Xie, D.; Liao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, K. Stability of the horizontal salt cavern used for different energy storage under varying geological conditions. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Fan, J.; Jiang, D.; Jjk, D.; Li, Y. Physical simulation of construction and control of two butted-well horizontal cavern energy storage using large molded rock salt specimens. Energy 2019, 185, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Shi, X.; Han, Y. Physical simulation of flow field and construction process of horizontal salt cavern for natural gas storage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 82, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kou, H.; Han, W. Mechanical properties and failure mechanism of sandstone with mudstone interlayer. EDP Sci. 2019, 136, 04048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, C.; Shi, X. Effects of interlayer on stress and failure of horizontal salt cavern. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2017, 36, 3314–3320. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, S. Failure mechanism of bedded salt formations surrounding salt caverns for underground gas storage. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2017, 76, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Shi, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.; Ma, H.; Daemen, J. Stability and availability evaluation of underground strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) caverns in bedded rock salt of Jintan, China. Energy 2017, 134, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Deng, J.; Wanyan, Q.; Feng, Y.; Lenwoue, A.R.K.; Luo, C.; Hui, C. Numerical investigation on shape optimization of small-spacing twin-well for salt cavern gas storage in ultra-deep formation. Energies 2021, 14, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wei, X.; Shi, X.; Liang, X.; Bai, W.; Ge, L. Evaluation methods of salt pillar stability of salt cavern energy storage. Energies 2022, 15, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q. The influence of operation pressure on the long-term stability of salt-cavern gas storage. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 6, 537679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. Tightness and stability evaluation of salt cavern underground storage with a new fluid–solid coupling seepage model. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 202, 108475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhou, J.; Liang, G.; Peng, C.; Hu, C.; Guo, D. Investigation on the long-term stability of multiple salt caverns underground gas storage with interlayers. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2023, 145, 081202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of crosslinking agents and reservoir conditions on the propagation of fractures in coal reservoirs during hydraulic fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (kg/m3) | Elasticity Modulus (GPa) | Poisson | Internal Friction Angle (◦) | Cohesion (MPa) | Tension (MPa) | A (Pa−n·s−1) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mudstone | 2450 | 5.48 | 0.263 | 39.57 | 8.19 | 1.67 | 2.06 × 10−35 | 4.35 |

| Salt Rock | 2200 | 3.99 | 0.240 | 30.51 | 5.70 | 1.04 | 1.56 × 10−34 | 3.52 |

| Interlayer | 2300 | 3.80 | 0.277 | 30.43 | 5.45 | 1.08 | 1.63 × 10−40 | 3.50 |

| Interface | - | - | - | 45.18 | 2.62 | 1.20 | - | - |

| Interlayer Thickness (m) | Dip Angle (°) | Minimum Operating Pressure (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 2 | 0 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 3 | 5 | 0 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 4 | 2 | 0 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 5 | 2 | 10 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 6 | 2 | 20 | 3.61 (26% σz) |

| Case 7 | 2 | 0 | 2.88 (20% σz) |

| Case 8 | 2 | 0 | 3.61 (20% σz) |

| Case 9 | 2 | 0 | 4.33 (20% σz) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Qin, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhang, B.; Feng, S.; Qin, J. Research on the Mechanical Behavior of Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface in Salt Cavern Gas Storage Under Storage-Release Cycle. Energies 2025, 18, 6497. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246497

Yang X, Qin Y, Xu N, Zhang B, Feng S, Qin J. Research on the Mechanical Behavior of Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface in Salt Cavern Gas Storage Under Storage-Release Cycle. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6497. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246497

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaochuan, Yan Qin, Nengxiong Xu, Bin Zhang, Shuangxi Feng, and Jiayu Qin. 2025. "Research on the Mechanical Behavior of Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface in Salt Cavern Gas Storage Under Storage-Release Cycle" Energies 18, no. 24: 6497. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246497

APA StyleYang, X., Qin, Y., Xu, N., Zhang, B., Feng, S., & Qin, J. (2025). Research on the Mechanical Behavior of Interlayer-Salt Rock Interface in Salt Cavern Gas Storage Under Storage-Release Cycle. Energies, 18(24), 6497. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246497