Abstract

Hydrogen energy, with its high calorific value and zero carbon emissions, serves as a crucial solution for addressing global energy and environmental challenges while achieving carbon neutrality. The ocean offers abundant renewable energy resources including offshore wind, solar, and marine energy, along with vast seawater reserves, making it an ideal platform for green hydrogen production. This review systematically examines recent research progress in several key marine hydrogen production approaches: seawater electrolysis through both desalination-coupled and direct methods, photocatalytic seawater splitting, biological hydrogen production via algae and bacteria, and hybrid renewable energy systems, each demonstrating varying levels of technological development and industrial readiness. Despite significant advancements, challenges remain, such as reduced electrolysis efficiency caused by seawater impurities, high costs of catalysts and corrosion-resistant materials, and the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources. Future improvements require innovations in catalyst design, membrane technology, and system integration to enhance efficiency, durability, and economic feasibility. The review concludes by outlining the technological development directions for marine hydrogen energy, highlighting how hydrogen production from marine renewable energy can facilitate a sustainable blue economy through large-scale renewable energy storage and utilization.

1. Introduction

1.1. Significance of Marine Renewable Hydrogen Energy

For over two centuries since the Industrial Revolution began, the extensive use of fossil fuels has resulted in excessive greenhouse gas emissions, driving a nearly 1.5 °C increase in atmospheric temperature. This anthropogenic warming has significantly intensified global climate change, progressively threatening human survival and development. The Paris Agreement established the critical mitigation target of maintaining atmospheric CO2 concentrations below 450 ppm by the end of the 21st century [1]. In parallel, China committed in 2020 to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 [2]. Attaining these ambitious goals necessitates urgent global restructuring of energy systems toward cleaner renewable alternatives. Hydrogen stands out as the cleanest energy carrier, producing only water as an emission byproduct during energy generation. Within the global transition toward climate change mitigation and energy system transformation, hydrogen energy—characterized by its inherent cleanliness, high energy density and zero carbon emissions—has emerged as a strategically vital secondary energy source for achieving carbon neutrality. Consequently, advancing clean hydrogen technologies, particularly “green hydrogen,” carries strategic significance for sustainable development.

Green hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced through renewable energy conversion, serving as a stable energy carrier for abundant yet intermittent natural renewable resources. Its production and utilization enable net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases and pollutants throughout the entire lifecycle, making it the most attractive hydrogen pathway compared to gray or blue hydrogen. The ocean represents Earth’s largest renewable energy reservoir, containing vast, clean, and sustainable resources including offshore wind, solar, tidal, and wave energy [3]. For instance, global offshore wind power boasts a technical potential of 27.3 TW and 66,200 TWh [4], while offshore solar energy has an annual theoretical reserve of 14 × 109 GWh [5]. Marine renewable energy offers an emerging and sustainable approach for green hydrogen production at sea. These resources can provide continuous energy for hydrogen generation, while seawater serves as an inexhaustible feedstock. This unique combination of resources positions the ocean as an ideal platform for hydrogen industry and blue economy development. The blue economy refers to the concept of sustainable utilization and management of marine resources to promote economic growth and protect the marine environment. Hydrogen production simultaneously enables flexible energy storage conversion for offshore renewables, facilitating local consumption of intermittent power supply. This approach achieves seasonal energy storage and efficient utilization, improves overall energy efficiency, and reduces costs and transmission losses associated with offshore power cables [6].

Given the promising development prospects of marine hydrogen energy, major global economies are actively advancing integrated projects focusing on offshore hydrogen production, storage, transportation and utilization. Europe currently dominates this emerging sector, accounting for 85% of existing offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects worldwide, benefiting from its stable maritime wind patterns and high-quality wind resources. France’s Sealhyfe project represents the world’s first offshore wind-powered hydrogen pilot, with a daily production capacity of 400 kg H2 [7]. The UK-led North Sea Wind Power Hub project, scheduled for commissioning in 2025 and connected to the 1.4 GW Hornsea Two wind farm (currently the world’s largest offshore wind facility), is projected to annually produce approximately 20,000 tonnes of green hydrogen. This output will supply zero-carbon hydrogen to Phillips 66’s Humber refinery, enabling annual carbon reductions exceeding 200,000 tonnes in refining processes [8]. The UK has established ambitious targets including 50 GW of offshore wind capacity with 5 GW dedicated to hydrogen production by 2030 while improving curtailment utilization for green hydrogen conversion to reach 455,000 tonnes by 2029. Concurrently, floating wind turbine-direct hydrogen production technology is being validated to achieve 82% energy conversion efficiency, paving the way for large-scale hydrogen production in deeper offshore areas with greater energy potential.

The Netherlands’ NortH2 project, currently Europe’s largest offshore wind-to-hydrogen initiative, aims to deploy 4 GW of offshore wind capacity dedicated entirely to electrolytic hydrogen production by 2030, with an annual output target of 400,000 tonnes of green hydrogen. This development will significantly contribute to the Dutch national goal of allocating one-third of its 11.5 GW offshore wind capacity for hydrogen production by 2030 [9]. The project strategically utilizes existing natural gas infrastructure in northern Netherlands, including pipeline networks and underground salt caverns for hydrogen storage, thereby minimizing new infrastructure investments. In parallel, the pioneering PosHYdon (Neptune Energy, Hague, The Netherlands) project represents the world’s first conversion of a decommissioned oil/gas platform into a green hydrogen hub, demonstrating the integration of offshore wind, legacy hydrocarbon infrastructure, and hydrogen systems [10]. This innovative approach employs offshore wind power for platform-based electrolysis, with the produced hydrogen being blended into natural gas and transported ashore via repurposed subsea pipelines. Germany has concurrently launched multiple demonstration projects encompassing offshore green hydrogen production, subsea hydrogen pipeline networks, and million-tonne-scale salt cavern storage. These initiatives include rigorous testing of critical equipment like PEM electrolyzers under simulated extreme offshore conditions (including 12-level sea states and salt spray corrosion), primarily targeting decarbonization of heavy industries (steel and chemicals) in the Ruhr region and maritime transport sectors.

Australia’s southern waters possess exceptional offshore wind potential estimated at 5000 GW, creating ideal conditions for hydrogen production. This has led the Australian government to establish ambitious targets for renewable hydrogen production and export, aiming to ship at least 200,000 tonnes annually by 2030 [11]. The Cape Hardy project in South Australia, now underway, is designed to produce over 500,000 tonnes of green hydrogen per year. Japan has initiated plans for centralized offshore hydrogen production platforms that will aggregate electricity from wind farms to semi-submersible hydrogen production units, with the produced hydrogen stored in onboard tanks and transported via specialized hydrogen carriers. This project, located off Hokkaido’s coast, targets commercialization before 2030 [12]. Japan has demonstrated leadership in maritime hydrogen infrastructure through the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier, Suiso Frontier, while also advancing marine applications of marine hydrogen through innovations like the Hydro Bingo, the inaugural hydrogen-powered ferry launched in 2021 [13]. China, possessing the world’s largest manufacturing capacity for offshore wind equipment and electrolyzers along with record-breaking annual installations, has established favorable industrial conditions for offshore hydrogen development, including several pilot-scale offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects [14]. Notably, China has pioneered the world’s first demonstration of direct seawater electrolysis (producing green hydrogen using untreated seawater) technology integrated with offshore wind turbines, successfully validating the system’s reliability under challenging marine conditions with wind speeds of 3–8 beaufort scale and wave heights of 0.3–0.9 m [15].

The development of hydrogen production from marine renewable sources shows considerable promise with notable economic and environmental benefits, although current technologies and applications remain at an early stage with persistent challenges. The key lies in addressing a series of specific technical issues across critical segments of the marine hydrogen value chain. These essential segments include (a) efficient conversion of marine renewable energy to hydrogen, (b) safe and reliable offshore hydrogen storage and transportation, and (c) utilization pathways and efficiency of marine hydrogen. The technical challenges encountered in these production, storage, transportation and utilization processes stem not only from inherent difficulties in hydrogen production methods, the intrinsic properties of hydrogen, and fundamental hydrogen technologies, but also from the compounded effects of unique marine environmental conditions and application scenarios.

In hydrogen production, the inherent efficiency limitations of electrolysis are exacerbated by marine conditions, where chloride-induced corrosion and biofouling significantly reduce electrolyzer lifespan, while the intermittent nature of offshore renewables further destabilizes system operation. Space constraints on turbine platforms, heavy reliance on subsea pipelines, and exposure to harsh marine weather contribute to higher failure rates. Additional investment costs arise from seawater pretreatment and hydrogen purification systems. Storage and transportation face dual challenges: hydrogen’s intrinsic low energy density (0.0899 kg/m3 at standard conditions) and marine-specific difficulties. Mechanical impacts and entrainment pose threats to desalination equipment [16]. High-pressure hydrogen storage risks material fatigue from wave impacts, cryogenic storage conflicts with humid/salty conditions due to insulation requirements, while chemical storage materials suffer performance degradation in marine climates. Utilization challenges include heightened sensitivity of fuel cell systems to vessel vibrations and tilt conditions, with hydrogen embrittlement particularly compromising equipment reliability in high-humidity, high-salinity environments. Operational constraints like limited space and difficult maintenance render land-based solutions (e.g., frequent servicing) impractical offshore. This compounding of “hydrogen characteristics” and “marine conditions” creates critical challenges across efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and safety dimensions, demanding integrated, marine-adapted solutions throughout the value chain.

1.2. Technical Framework of Marine Hydrogen Energy Systems

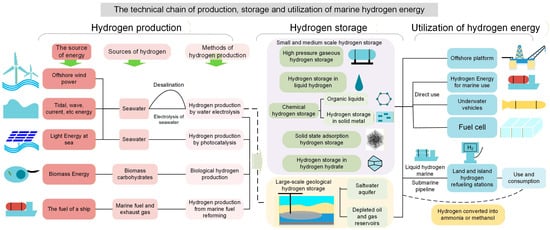

We have systematically outlined the technical framework of marine hydrogen energy systems, encompassing the complete technological chain from production to storage and end-use applications, along with detailed technical approaches as illustrated in Figure 1. For hydrogen production, four primary technological pathways are identified: renewable electricity-based hydrogen production, photocatalytic hydrogen production, biomass-derived hydrogen production, and ship fuel reforming. Renewable electricity-based hydrogen production involves converting offshore renewable energy into electricity to power electrolysis of either desalinated or untreated seawater. Among these approaches, offshore wind-to-hydrogen has emerged as the most mature and scalable solution, as previously discussed. Complementary to wind power, other marine energy sources including tidal, wave, and current energy can also generate electricity for electrolysis, while floating photovoltaic systems offer additional means to mitigate the intermittency of wind-based generation. Photocatalytic hydrogen production similarly utilizes solar energy and seawater as hydrogen sources, employing TiO2-based (titanium dioxide) or other catalysts to decompose seawater or surface vapor [17]. Biomass-derived hydrogen production harnesses marine microorganisms to convert seawater or biomass carbohydrates into hydrogen through controlled cultivation systems. The ship fuel reforming approach represents a transitional marine hydrogen solution, where onboard reformers catalytically process ship fuels and engine exhaust to produce hydrogen-rich gas for direct fuel use, simultaneously improving combustion efficiency and reducing maritime emissions.

Figure 1.

The technical chain of production, storage and utilization of marine hydrogen energy.

The hydrogen storage sector primarily adopts two technical pathways: small-to-medium scale storage and large-scale geological storage. Currently, high-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage (70–80 MPa) dominates the market, despite its relatively low energy density and stringent tank requirements. Cryogenic liquid hydrogen storage, while energy-intensive, remains the preferred method for large-scale marine hydrogen transport [13]. Chemical storage approaches encompass reversible reactions using organic liquid carriers and metal hydrides for liquid-phase and solid-phase hydrogen storage/release, respectively [18]. Organic liquid carriers show promise for marine hydrogen transportation, whereas metal hydrides are better suited for modular fuel systems in hydrogen-powered vessels. H2 hydrate storage represents an emerging safe storage technology, enabling solid-state hydrogen storage under moderate temperature and pressure conditions (below 20 MPa) [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Both chemical and hydrate storage methods remain in experimental development stages. For large-scale applications, subsea geological storage leverages existing salt cavern storage and CO2 sequestration technologies, utilizing offshore saline aquifers and depleted oil/gas reservoirs with existing pipeline infrastructure. Individual storage sites can accommodate tens of thousands of metric tons of hydrogen, with stability and safety validated by petroleum industry practices [25]. This geological storage approach will serve as a primary solution for offshore wind power utilization and energy peak-shaving applications.

In the hydrogen utilization phase, offshore platforms, small islands, and marine applications including ship fuel cell systems, hydrogen-powered vessels, ROVs (remotely operated vehicle), and AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicle) can be refueled through on-site hydrogen production and storage systems. For larger islands and mainland applications, hydrogen is typically transported via subsea pipeline networks or specialized hydrogen carriers, then distributed through refueling stations before final consumption in industrial sectors such as steel manufacturing, chemical production, energy generation, and transportation [26,27]. An alternative transportation-utilization pathway involves converting the produced hydrogen into more stable liquid hydrogen carriers like ammonia or alcohols, which offer easier maritime transportation and subsequent utilization [28].

This study primarily focuses on offshore hydrogen production, systematically reviewing the latest marine renewable energy-based hydrogen generation methods and maritime-specific technologies documented in the current literature. Our comprehensive analysis encompasses direct seawater electrolysis, desalination-coupled hydrogen production, coordinated operation of intermittent renewable power with electrolysis systems, photocatalytic seawater splitting, and marine biological hydrogen production. By synthesizing cutting-edge multidisciplinary advancements, we elucidate the fundamental challenges underlying these technological bottlenecks: (1) Chloride corrosion and ion deposition in seawater electrolysis. (2) Energy consumption optimization and thermal integration requirements in desalination-coupled systems. (3) Power fluctuation management and start-stop cycling losses in renewable energy-electrolyzer coordination. (4) Charge carrier recombination limitations in photocatalysis. (5) Microbial metabolic efficiency constraints in biological approaches. Through comparative assessment of technical challenges, economic feasibility, and environmental compatibility, this review summarized and looked forward to future material innovations and system integration strategies in marine renewable hydrogen production.

The organization of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 examines marine electrolytic hydrogen production technologies, providing a detailed analysis of the principles, characteristics, and research advancements in various marine renewable energy-to-hydrogen conversion methods. This includes electrolysis using desalinated seawater (Section 2.1), direct seawater electrolysis (Section 2.2), and the integration of renewable power generation with hydrogen production systems (Section 2.3). Section 3 focuses on photocatalytic seawater splitting. Section 4 presents marine biological hydrogen production technologies. Section 5 provides a comprehensive discussion and outlook, synthesizing the challenges across different marine renewable hydrogen production approaches and outlining future research directions. By systematically reviewing technological progress in marine renewable hydrogen production and evaluating the current status and development trajectories of various technical pathways, this study aims to offer both theoretical frameworks and practical technical insights to advance the marine hydrogen energy industry, thereby supporting global energy transition and carbon neutrality objectives.

2. Seawater Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production

2.1. Direct Hydrogen Production via Electrolysis of Desalinated Seawater

Electrochemical water splitting for hydrogen production utilizes direct current to decompose water into hydrogen and oxygen through cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER). Catalysts are used to accelerate the two most energy-intensive reactions in water electrolysis, OER and HER, thereby increasing hydrogen production efficiency and reducing energy consumption [29]. Based on electrolyte types, the technology can be categorized into four main systems: alkaline water electrolysis (AWE), proton exchange membrane electrolysis (PEM) [30], anion exchange membrane electrolysis (AEM), and solid oxide electrolysis (SOE), with the first two currently achieving commercial viability [31]. However, in offshore applications, the additional energy conversion steps—transforming wind, solar, tidal or wave energy into electricity, then using part of this electricity for seawater desalination to obtain high-purity water before electrolysis—significantly increase production costs. Projections indicate hydrogen demand by 2030 will require approximately 21 billion cubic meters of freshwater annually [32]. Large-scale green hydrogen production still depends on sustainable and reliable freshwater supplies due to multiple adverse effects of seawater chloride content on electrolysis: competitive chlorine evolution reaction at the anode alongside OER; corrosive dissolution of non-noble metals forming metal chlorides under anodic potentials; and membrane/electrode fouling by microorganisms, minerals and contaminants, with seawater cations particularly reducing AEM conductivity [33]. Consequently, desalination remains a critical preprocessing stage for electrolytic hydrogen production from seawater.

2.1.1. Desalination

Seawater desalination technologies primarily comprise membrane-based, thermal-based, and electrical-based approaches. Among membrane processes, reverse osmosis (RO) and forward osmosis (FO) represent the most prevalent methods [34]. RO operates by selectively permitting specific solute components to pass through a semi-permeable membrane under applied pressure (make water flow from the concentrated solution side to the dilute solution side), effectively removing salts and contaminants from water. As the dominant desalination technology, RO accounts for over 70% of global desalination capacity due to its superior cost-effectiveness and lower energy requirements compared to alternative methods. Membrane-based technologies generally demonstrate significant advantages over thermal distillation systems, including reduced energy consumption, compact system design, and high modularity. Continuous advancements in membrane materials, energy recovery devices, and high-efficiency pumps have further enhanced the low-energy and operational advantages of membrane desalination. However, membrane fouling remains a critical challenge for RO systems, necessitating additional operational costs for membrane cleaning and feedwater pretreatment [35]. Thermal desalination methods fundamentally rely on multi-stage evaporation of saline water through heating or pressure reduction, followed by vapor condensation to produce fresh water. Current mainstream thermal technologies include multi-stage flash (MSF), multi-effect distillation (MED), vapor compression distillation (VC), membrane distillation (MD), and solar-powered (thermal or photovoltaic) systems [36].

Among electrical-based methods, electrodialysis (ED) employs ion-exchange membranes under an applied DC electric field to selectively transport anions and cations through respective membranes, achieving desalination or concentration. Despite its notable cost advantages [37] and direct electricity utilization benefits, ED is limited to brackish water with salinity below 3.5 wt%, making it unsuitable for direct large-scale seawater desalination and hydrogen production applications [38]. Capacitive deionization (CDI), another electrical desalination technology, typically consists of two carbon electrodes sandwiching a saline flow, operating through an electrical double-layer capacitive mechanism where salt ions are transported and adsorbed onto the electrode surfaces under an applied electric field. Both ED and CDI are restricted to low-salinity water treatment, though they may serve as secondary desalination steps for brackish water produced by mainstream RO and mechanical vapor compression (MVC) systems in marine renewable energy scenarios [39,40]. Several emerging but less mature desalination technologies are under development, including marine microalgae-based systems, freeze desalination, gas hydrate processes, and ion-exchange methods [19,37,41,42,43,44].

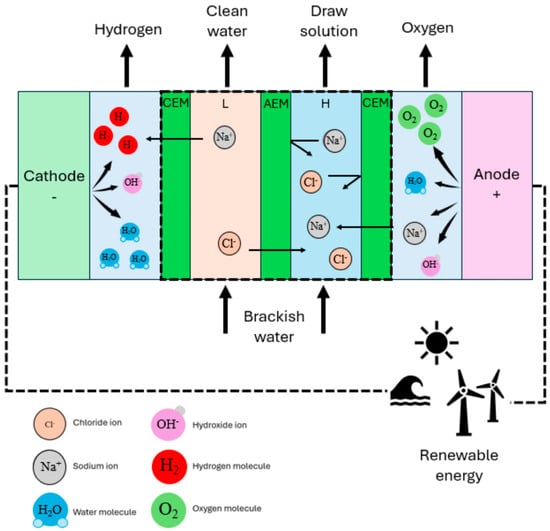

Notably, ED offers the distinct advantage of simultaneous seawater desalination and hydrogen production [34]. In conventional ED systems, ion migration occurs concurrently with chloride oxidation at the anode to form chlorine compounds, while water reduction at the cathode generates small amounts of hydrogen, as illustrated in Figure 2 [45]. This integrated process enables partial hydrogen production prior to electrolysis using the desalinated water, thereby enhancing overall hydrogen production efficiency and making the technology particularly suitable for offshore applications [46]. Researchers have developed various approaches to improve hydrogen yield while maintaining desalination efficiency, including reverse electrodialysis (RED), short-circuited RED (REDSC), assisted RED (ARED), and multi-stage RED systems that leverage salinity gradients for green hydrogen production, effectively reducing the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) [47,48].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of green hydrogen production via ED membrane process [45].

Campisi et al. developed a novel hydrogen-electrodialysis (HED) technology by incorporating additional shared electrodes into the cell stack, enhancing hydrogen production rates without compromising freshwater output. Preliminary results demonstrated a competitive LCOH at 3.43 €/kg·H2, indicating the economic viability of upgrading conventional ED to HED systems [49]. Pellegrino et al. introduced a bipolar membrane electrodialysis (H-EDBM) approach capable of operating at current densities one order of magnitude higher than standard ED and RED processes, achieving remarkable hydrogen production efficiency (98%) and rates (18.4 mol/hm2). This configuration additionally coproduces sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for subsequent electrolysis applications [50]. Alshebli et al. investigated hydrogen recovery during Na2SO4 solution desalination via ED, where ion-exchange resin incorporation reduced system resistance, improving conductivity removal ratios beyond 95.7% and enabling maximum hydrogen evolution rates of 76.8 mg H2/h·kg Na2SO4 solution [51].

Offshore desalination systems differ significantly from coastal large-scale plants in their technological configurations and operational preferences. Marine-based units prioritize modular designs and compact footprints, while their energy-intensive nature necessitates reliance on offshore renewable energy sources [52]. Wind and marine energy (tidal and current) can power pressure-driven membrane processes like FO and RO, whereas solar energy and waste heat from hydrogen electrolysis may supply thermal-based methods including MED, MD, and MSF. Electrically powered systems such as RO, ED, and MVC can utilize offshore wind or solar generation. Currently, wind/solar-RO hybrid configurations dominate renewable-powered desalination, accounting for over 50% of such installations [53].

Researchers have investigated various configurations including displacement hydraulic wind turbines, vertical-axis wind turbine-high pressure pump systems, and direct/indirect mechanical drive systems to examine the effects of feedwater salinity, loading conditions, wind speed variations on RO desalination performance [54,55,56,57]. Amin et al. integrated wind turbines with floating desalination plant (FDP) platforms, conducting comprehensive dynamic response analyses of combined turbine-platform systems under historical Red Sea conditions through frequency-domain and time-domain motion studies [58]. Miao et al. demonstrated the feasibility of floating solar-thermal driven MD modules, where natural wave action enhanced feedwater circulation and mass transfer by agitating both the heating bags and MD units at the sea surface [36]. For island and offshore applications characterized by wind/solar intermittency, hybrid PV-wind-RO systems exhibit superior robustness against environmental variability [59,60]. Zhang et al. confirmed the technical viability of current energy-RO coupling, maintaining specific energy consumption below 3.35 kWh/m3 [61].

As mentioned in Section 1.1, all operational offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects currently employ coupled desalination-electrolyzer systems, predominantly utilizing RO technology (e.g., the UK’s Dolphyn Hydrogen project). Given RO’s dominance in offshore applications, we briefly summarize its persistent challenges and recent developments. Despite being the fastest-growing desalination sector, RO systems still exhibit relatively high energy consumption (2–5 kWh/m3) [35], particularly problematic for energy-intensive hydrogen production. The process becomes increasingly energy-demanding with higher feedwater salinity. The semipermeable membranes—RO’s core components—face limitations including short service life, mechanical fatigue from frequent start-ups under renewable power fluctuations, and permeate flux decline due to variable pressure/flow conditions [62]. Common scaling compounds like CaSO4 and CaCO3 exhibit distinct deposition patterns: particulate/organic fouling and biofilm formation primarily occur in membrane elements, while metal salt scaling concentrates in terminal elements. These accumulating deposits induce concentration polarization and progressively degrade membrane performance [63]. Such issues may be exacerbated in marine environments, necessitating novel solutions to reduce both operational costs and energy demands.

Yao et al. synthesized polymer membranes through polymerization of 3,5-dihydroxy-4-methylbenzoic acid with methanesulfonyl chloride, demonstrating remarkable resistance to hydrolytic degradation under both acidic and alkaline conditions, along with complete chlorine tolerance [64]. Wang et al. fabricated ultrathin COF membranes exhibiting exceptional desalination performance (92 kg/m2h1) through synergistic longitudinal self-healing and self-inhibition effects [65]. Liu et al. employed interfacial catalytic polymerization to produce robust polyester thin films with enhanced reaction kinetics that overcome the limited reactivity of natural monomers, achieving superior desalination performance [66]. Additional advancements include supramolecular nanocrystalline membranes [67], biomimetic artificial water channel membranes [68,69], MOF-based membranes [70,71], polymeric hollow fiber membranes, and layered carbon nitride membranes, all contributing to improved RO desalination efficiency and energy savings.

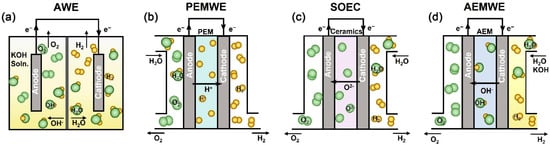

2.1.2. Electrolytic Hydrogen Production from Desalinated Water

Table 1 compares the advantages and disadvantages of electrochemical water splitting technology. AWE represents the earliest industrialized water electrolysis technology with decades of operational experience [72]. The core components of AWE electrolyzers include cathode and anode electrodes, a membrane separator, flow field plates, gas diffusion layers, and bipolar plates [73]. These systems employ highly concentrated (20–40%) KOH or NaOH aqueous solutions as electrolytes to enhance ionic conductivity. Utilizing asbestos membranes to separate hydrogen and oxygen production, AWE typically achieves 70–80% efficiency. Under direct current, water molecules undergo reduction at the cathode to produce hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions (OH−), which then migrate through the membrane to the anode where oxygen evolution occurs.

Table 1.

Comparison of electrochemical water splitting technology.

AWE offers several advantages: mature technology, relatively low capital costs, long-term operational stability, and compatibility with inexpensive non-precious metal catalysts (Ni, Co, Mn) [74]. However, limitations include the corrosive and polluting nature of strong alkaline electrolytes requiring complex maintenance, the necessity for product gas dealkalization, and environmental concerns associated with asbestos membranes. The membranes’ incomplete gas separation results in lower hydrogen purity (approximately 99.8%) [75]. Additional drawbacks comprise slow response times during startup/shutdown or load variations, poor compatibility with highly intermittent renewable power sources, relatively low current densities (0.2–0.6 A/cm2), and low output gas pressure (0.1–1.0 MPa) necessitating additional compression for storage/transport.

PEM electrolysis has experienced rapid industrial development in recent years, achieving preliminary commercialization and becoming the preferred electrolyzer technology for several operational and planned offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects worldwide [76,77]. The European Union has established a development roadmap for PEM electrolysis to progressively replace AWE. PEM electrolyzers typically employ a bipolar structure, as illustrated in Figure 3 [78], with each cell comprising seven key components: cathode/anode bipolar plates, cathode/anode gas diffusion layers, cathode/anode catalyst layers, and a proton exchange membrane [79]. The anode side utilizes pure water as the reactant, where oxidation generates oxygen and protons (H+); these H+ migrate through the membrane under the applied electric field to the cathode, undergoing reduction to form hydrogen gas [72]. The proton exchange membrane serves as a critical component of the membrane electrode assembly, exhibiting high proton conductivity, excellent gas impermeability, chemical stability, and hydrophilicity, while also providing structural support for catalyst coatings. Its performance directly determines the operational efficiency and lifespan of PEM electrolyzers. Major PEM types include sulfonated polymer membranes, composite membranes, and inorganic acid-doped membranes.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustrations of (a) AWE, (b) PEM, (c) SOE, and (d) AEM [78].

The PEM effectively isolates gases on both electrodes while facilitating proton conduction, eliminating the risk of H2 contamination by alkaline electrolytes characteristic of AWE systems. This configuration ensures hydrogen purity exceeding 99.99% and prevents formation of explosive gas mixtures. PEM electrolyzers demonstrate superior performance metrics, including higher current densities (1–4 A/cm2), broader output pressure ranges (0.1–7.0 MPa), lower operating temperatures (30–80 °C), and improved overall efficiency compared to AWE. The zero-gap cell design reduces ohmic resistance significantly while achieving more compact dimensions (approximately one-third of AWE volume) and lighter weight (Figure 3), making PEM particularly suitable for space-constrained offshore applications. These systems feature rapid response capabilities, with cold start times under 5 min and shutdown within seconds [80], enabling effective integration with highly variable wind and solar power inputs. Despite these advantages, PEM technology faces limitations including smaller single-stack production capacity compared to AWE, high material costs associated with Iridium/Ruthenium (Ir/Ru) oxides and platinum (Pt) nanoparticle catalysts [81], susceptibility to metal ion poisoning in seawater environments, and relatively shorter membrane lifespans.

SOE, also termed high-temperature steam electrolysis, remains at the preliminary demonstration stage. As the reverse process of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC), oxygen-ion conducting SOE cells comprise dense electrolytes sandwiched between porous electrodes. High-temperature steam introduced at the cathode undergoes reduction to hydrogen and oxide ions, with the latter migrating through the electrolyte to the anode where oxygen evolution occurs. Proton-conducting SOE variants instead feed steam at the anode. These systems employ cost-effective perovskite and zirconia-based materials for both electrolytes and catalysts. Operating at 600–1000 °C, SOE benefits from accelerated reaction kinetics, substantially reducing the electrical energy requirement for water splitting while achieving superior energy efficiency (>90%) compared to AWE and PEM technologies. However, the elevated operating temperature increases thermal energy demand [82]. For offshore applications utilizing wind or solar power, this necessitates additional energy conversion from electricity to heat, while the substantial waste heat generated lacks effective utilization pathways—factors that collectively reduce overall system efficiency. Furthermore, SOE systems require specialized materials to withstand high-temperature degradation, increasing capital costs. Additional limitations include relatively short lifespans, slow start-stop cycles, operational instability, and low hydrogen output pressure (0.1 MPa).

AEM electrolysis represents an emerging water-splitting technology currently in early research stages [83]. In AEM electrolyzers, water introduced at the cathode undergoes reduction to produce OH− and hydrogen gas, with OH− migrating through the polymeric AEM to the anode where oxidation generates water and oxygen [84]. The feedwater sometimes contains low-concentration KOH as supporting electrolyte. AEM technology combines advantages of both AWE and PEM systems, achieving higher current densities, faster start-stop response times, lower catalyst costs [85], and improved energy conversion efficiency. However, the limited alkaline stability of anion exchange membranes poses a major development challenge, as localized high-pH conditions at the membrane surface during operation lead to OH−-induced degradation. This fundamental trade-off between ionic conductivity and membrane stability currently hinders practical implementation. Both SOE and AEM electrolysis technologies require breakthroughs in membrane materials, catalysts, and electrolytes before becoming viable for offshore wind and renewable energy applications, with near-term deployment remaining unlikely.

In summary, PEM technology demonstrates superior performance for marine renewable hydrogen production when considering key offshore operational metrics including compactness, startup speed, electrolysis efficiency, hydrogen output pressure and purity. To address challenges associated with PEM membrane durability, stability and high material costs, while further enhancing electrolysis efficiency, significant research efforts have been devoted to catalyst development [75,86]. Li et al. designed a Ni0.1Co0.9Se2 catalyst as a cost-effective alternative to Pt-based materials, achieving high current density (1.83 V@500 mA/cm2) and remarkable stability (500 mA/cm2@100 h) [81]. Zhang et al. employed sulfur doping to induce structural modifications in pyrite-type CoSe2, improving hydrogen diffusion and electrocatalytic performance [87]. Zeng et al. developed Mo2TiC2-MXene supported Pt nanoclusters that maintain high activity and stability while minimizing Pt loading (36 μg/cm2) [88]. Deng et al. synthesized ternary PtNiP amorphous nanoparticles (PtNiP-ANP) with optimized hydrogen adsorption Gibbs free energy (0.02 eV), surpassing crystalline Pt catalysts and demonstrating the unique electronic properties of amorphous materials [89].

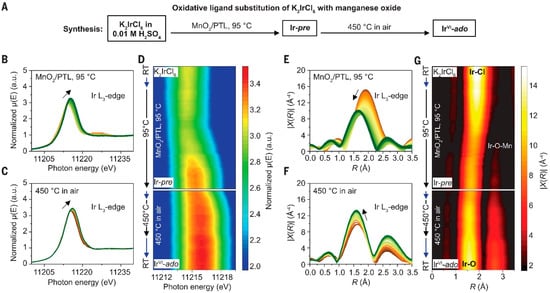

Li et al. successfully oxidized Ir catalysts to the hexavalent state (IrVI) using MnO as oxidant, achieving optimal activity and stability (Figure 4). The resulting catalyst maintained a high current density of 2.3 A/cm2 over several months of operation [90]. Tran et al. developed TiO2-supported Ir@IrO(OH)x core–shell nanoparticles as a cost-effective alternative to commercial IrO2 anodes, reducing Ir usage by over 50% [89]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that tantalum (Ta) doping in RuO2 effectively mitigates dissolution during oxygen evolution, enabling its potential substitution for IrO2 while simultaneously enhancing corrosion resistance and catalytic activity. Xu et al. incorporated lattice water into IrOx·nH2O, creating a short-range ordered hollandite-like framework that exhibited both improved activity and exceptional stability (~8 months) without structural degradation [91]. Kong et al. enhanced manganese oxide catalyst durability by replacing pyramidal oxygen with planar oxygen configurations featuring stronger Mn-O bonds, suppressing Mn (manganese) dissolution and expanding the potential of earth-abundant PEM electrolysis catalysts to reduce Ir dependence [92].

Figure 4.

In situ XAS analysis of IrVI formation: (A) Synthetic preparation of IrVI (B,C) XANES spectra for the iridium L3-edge, (E,F) EXAFS spectra for the iridium L3-edge, and (D,G) two-dimensional color maps showing the shift in the absorption edge and the coordination shell [90].

Hu et al. synthesized a high-entropy Ru-Ir oxide (M-RuIrFeCoNiO2) catalyst, where the multi-component design strategy effectively addressed the poor stability and limited activity of RuO2 under acidic oxygen evolution conditions [93]. To mitigate the continuous dissolution and oxidation of Ru-based electrocatalysts during electrolysis, Sun et al. identified ZnRuOx as exhibiting exceptional stability for acidic oxygen evolution reactions through transition metal screening [94]. Yuan et al. developed a synergistic doping approach incorporating earth-abundant Mn and Nb (Niobium) into RuO2, creating Nb0.1Mn0.1Ru0.8O2 nanoparticles that simultaneously stabilize lattice oxygen and reduce valence fluctuations at Ru sites, thereby enhancing catalytic stability [95]. Shi et al. elucidated the critical role of catalytic mechanisms and intermediate binding strength in determining the operational stability of Ru-based catalysts, leading to the development of SnRuOx solid solutions with order-of-magnitude lifespan extension [96]. Liu et al. employed a molten salt-assisted quenching strategy to induce tensile strain in Sr/Ta co-doped RuO2 nanocatalysts, spatially elongating Ru-O bonds and reducing covalency to suppress lattice oxygen participation and structural degradation, resulting in comparable stability and lower degradation rates than pristine catalysts [97].

Significant advancements in electrolyzer design have been achieved through innovative engineering approaches. Carrillo et al. integrated electrocatalytic reactions with capacitive storage mechanisms, enabling spatiotemporal separation of H2 and O2 evolution. Their system employed CoFe-EP/NF bifunctional catalysts to achieve 99% Faradaic efficiency at 100 mA/cm2, with a lower heating value efficiency of 69% [98]. Wang et al. developed a PEM electrolyzer capable of operating with impure water (containing cationic impurities) through microenvironment pH modulation, which reduced maintenance requirements while maintaining performance comparable to state-of-the-art systems using purified water [99]. Hodges et al. designed a novel electrolyzer architecture utilizing capillary-induced water transport through porous electrode separators to both hydrogen and oxygen evolution electrodes, demonstrating performance superior to conventional commercial electrolyzers [100].

2.2. Direct Seawater Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production

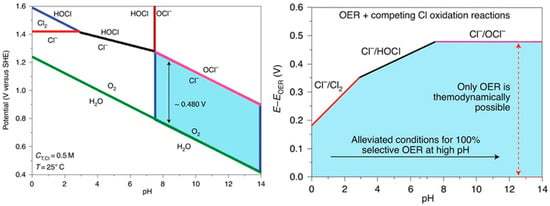

Direct seawater electrolysis offers significant advantages by eliminating the desalination step, thereby reducing space requirements, energy consumption, and capital costs while improving the utilization efficiency of offshore renewable electricity. This approach has emerged as a critical technology for large-scale commercialization of offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems. However, compared to conventional desalination-coupled electrolysis, direct seawater electrolysis faces substantial challenges including complex seawater composition, competitive chlorine evolution reactions, precipitate formation, electrolyzer corrosion, and catalyst deactivation. Addressing these issues requires innovations in membrane materials, catalysts, and electrolyzer design [101]. Figure 5 presents the Pourbaix diagram for OER electrodes in saline electrolytes [102], demonstrating how chloride ions (the most abundant anions in seawater) are readily oxidized to chlorine gas or hypochlorite at the anode. This process not only corrodes electrolyzer components and deactivates catalysts, but also introduces safety hazards [103]. Furthermore, cathodically generated OH− react with Mg2+ and Ca2+ in seawater to form insoluble Mg(OH)2 and Ca(OH)2 deposits that foul catalysts, membranes, and electrolyzer surfaces. These deposits increase energy consumption, impede ion transport, and degrade catalyst performance [104]. Additional operational challenges include membrane fouling, electrode deactivation, and biofouling caused by marine microorganisms and organic pollutants from domestic/industrial wastewater [33].

Figure 5.

Pourbaix diagram of OER electrodes in saline electrolytes with chloride species [102].

These challenges currently confine direct seawater electrolysis to laboratory-scale research. Critical solutions involve (1) developing corrosion-resistant catalysts with high activity and selectivity, (2) establishing protective strategies for electrode materials to mitigate seawater ion interference [105], and (3) designing novel ion-exchange membranes and electrolyzer configurations specifically for seawater electrolytes. Such innovations must address competitive oxidation reactions at both electrodes while overcoming corrosion and chlorine-induced degradation of catalysts, membranes, and reactor components to meet offshore hydrogen production requirements. The following discussion of recent advances follows this systematic solution framework.

Researchers have established multiple design strategies for selective OER catalysts in low-grade or seawater electrolytes. The primary approach involves incorporating highly active OER catalysts for alkaline seawater oxidation. Alternative methods include (1) selective OER catalysts with surface active sites for neutral saline electrolytes, predominantly utilizing Co- based (Cobalt) or Ru-based nanoparticles [106]; (2) chloride-blocking layers (e.g., MnO, NiFeOx, or NiCoS) at the anode periphery to prevent Cl− diffusion to active sites. Sun et al. developed a scalable hydrothermal method to synthesize spin-polarized Ni1/MoS2 single-atom catalysts, achieving 2880% OER current enhancement under 0.5 T magnetic fields with exceptional seawater electrolysis stability [107]. Xu et al. designed a Ru0.1Mn0.9Ox non-precious catalyst where Cl− adsorption on Ru sites shifts active centers to Mn, simultaneously avoiding Ru lattice oxygen consumption while creating OH−-rich local environments for OER [108]. Liu et al. demonstrated that asymmetric Fe doping in NiPS3 tunes local metal spin states, with medium-spin FeIII sites and P/S coordination synergistically enhancing OER activity and Cl− corrosion resistance [109]. Another Xu group study constructed NiMo/NiMoP (Nickel-Molybdenum-Phosphide) heterointerfaces with strong built-in electric fields that simultaneously optimize hydrogen adsorption and provide spatial shielding against Cl− attack [110].

Liu et al. revealed that Cl− specifically adsorbed at Fe sites in NiFe layered double hydroxides (NiFe-LDH) unexpectedly enhances performance by inhibiting Fe dissolution while activating additional Ni active sites, achieving 20.7% energy savings compared to conventional alkaline water electrolyzers [111]. He et al. selectively anchored phosphotungstic acid-polyoxometalates (PW12-POM) to Fe sites in CoFe hydroxides, effectively modulating the electronic structure of adjacent Co active centers and optimizing Cl−/OH− adsorption for efficient alkaline seawater oxidation [112]. Hu et al. developed a phosphate (PO43−)-induced rapid surface reconstruction strategy to fabricate Ni3FeN-based catalysts featuring conductive nitride cores and chloride-resistant hydroxide shells [113]. Dang et al. synthesized Ti3C2Tx-MXene-supported high-entropy (FeCoNiCuMn)2O3 nanoparticles that operate via an “adsorption-migration” mechanism, where strong MXene-oxygen intermediate interactions combined with coulombic repulsion of Cl− effectively prevent chloride adsorption and penetration [114].

For cathodic hydrogen evolution, preventing hydroxide deposition of seawater cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+) is critical. Pt-based alloys and transition metal catalysts demonstrate improved corrosion resistance and reduced ion deposition, enabling higher current densities and long-term stability in seawater electrolysis [115]. While Pt-group metals enhance reaction kinetics, their high cost and instability in non-acidic seawater have motivated development of non-precious catalysts based on C, S, P, and N compounds [116]. Transition metal phosphides (TMPs) and nitrides (TMNs), with their intrinsic conductivity and corrosion resistance, show particular promise as stable HER catalysts in seawater [29]. Porous carbon nanostructures and Ni-Fe LDH-based systems also demonstrate consistent efficiency improvements [117]. Sha et al. elucidated the dynamic degradation mechanisms of cathodes under intermittent renewable power input, showing that in situ phosphate passivation layers on NiCoP-Cr2O3 surfaces effectively isolate halide corrosion and prevent active site oxidation during frequent cycling [118]. Hu et al. introduced vanadium trioxide (V2O3) protective interlayers in AEM systems to modulate local catalytic environments, where OH− trapping simultaneously inhibits Cl− corrosion and hydroxide deposition while enabling low-loading Pt/Ni3N bifunctional catalysts [119].

Gao et al. developed a two-dimensional graphdiyne-supported monolayer osmium (Os) nanosystem, where strong interfacial interactions generated high-density charge distributions that optimized the hydrogen adsorption Gibbs free energy through incomplete charge transfer effects [120]. Shao et al. designed an Ir/HfO2@C (HfO2, Hafnium(IV) oxide) catalyst exhibiting bidirectional hydrogen spillover: HfO2-mediated reverse spillover under alkaline conditions and Ir-forwarded spillover in acidic media, achieving ultralow overpotentials for seawater electrolysis [121]. Liu et al. employed yttrium (Y) doping to engineer NiMo-MoO2 heterojunctions, simultaneously inducing lattice expansion in NiMo alloys (optimizing d-band centers for hydrogen desorption) while increasing oxygen vacancy concentrations in MoO2-x (accelerating OH intermediate desorption) [122]. Li et al. constructed N-doped C-encapsulated NiCoS heterostructures (CN@NiCoS), demonstrating that dynamic S migration creates paired S-doped CN shells and S vacancies that significantly enhance HER activity [123]. Jun et al. developed Ru-nanocluster-mediated Ru-MoO2-Ni4Mo catalysts, where Ru’s high hydroxyl affinity establishes local hydroxyl-deficient environments that effectively suppress MoO2 dissolution in alkaline conditions [124].

Novel Membrane and Electrolyte Systems. Fang et al. demonstrated effective impurity ion blocking in direct seawater electrolysis through combined anion/cation exchange membrane (AEM/CEM) designs, with minimal Mg/Ca deposition observed on electrodes after 5 days of continuous operation [125]. Deng et al. synthesized robust AEM featuring poly (biphenyl piperidinium) networks, exhibiting exceptional mechanical strength (79.4 MPa), low swelling ratio (19.2%), high hydroxide conductivity (247.2 mS/cm), and stable performance over 5000 h [126]. Ren et al. developed a zero-gap electrolyzer incorporating cation exchange-bipolar membrane assemblies, utilizing in situ water dissociation to create asymmetric pH environments for direct seawater electrolysis without supporting electrolytes [127]. Wang et al. identified localized heat accumulation as the primary degradation mechanism in hydroxide exchange membranes and engineered three-dimensional thermal-conductive networks that increased membrane thermal conductivity 32-fold while reducing degradation rates by 6 times [128].

Tang et al. developed a flexible gel electrolyte with exceptional ionic conductivity and water-trapping capacity, whose concentration-gradient-driven moisture migration mechanism enables hydrogen production from seawater or even humid air while accommodating marine environmental fluctuations [129]. Chen et al. achieved 10,000 h stable seawater electrolysis by incorporating SO42− additives with NiFeBa-LDH catalysts, forming dense sulfate protective layers on anode surfaces [130]. Zhao et al. optimized proton transfer pathways at Pt electrode interfaces using theophylline derivatives to create weakly hydrogen-bonded water networks, enhancing HER activity threefold while maintaining double-layer structures [131]. Liang et al. designed a PRT ternary anode system that drives efficient chlorine oxidation while completely suppressing oxygen evolution, which combined with MnOx cathodes in membrane-free electrolyzers produced ultra-high-purity hydrogen without O2 co-production [132]. Feng et al. engineered Os-O-Co bifunctional catalysts through in situ Os single-atom modification, achieving both minimal N-H bond cleavage barriers (for hydrazine oxidation) and optimal hydrogen adsorption energies (for HER) in membrane-free flow electrolyzers, reducing energy consumption by 70.7% compared to conventional seawater electrolysis [133].

The novel electrolyzer system. As described in Section 2.1.2, while PEM electrolysis demonstrates optimal potential for offshore applications under freshwater conditions, its stringent water purity requirements pose significant challenges for direct seawater utilization, leading to rapid membrane contamination and deactivation due to seawater’s corrosive and polluting nature. Addressing these issues inevitably increases technical complexity and cost. Guo et al. proposed an effective solution by introducing a Cr2O3 Lewis acid protective layer on CoOx to create localized alkaline conditions in situ, effectively preventing chlorine corrosion and electrode precipitation while maintaining performance comparable to conventional pure-water PEM electrolyzers [134]. In contrast to PEM, AEM systems, despite being prone to hydroxide precipitation-induced blockage at the cathode, offer distinct advantages for seawater electrolysis: their anion exchange membranes are generally more cost-effective and demonstrate superior corrosion resistance. The lower operating temperatures of AEM systems additionally mitigate seawater component deposition and corrosion. Furthermore, AEM’s elimination of precious metal catalyst requirements significantly reduces material replacement costs. These combined advantages make AEM technology particularly suitable for seawater environments.

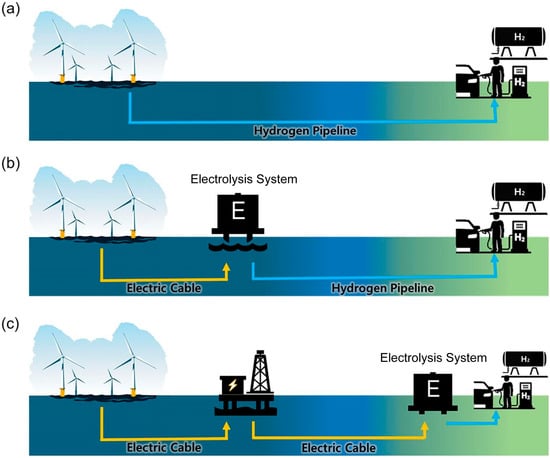

Xie et al. developed a novel in situ desalination-coupled electrolysis approach, utilizing the natural vapor pressure difference between a self-humidifying electrolyte (SDE, 30 wt% KOH) and seawater as the mass transfer driving force. This design enables spontaneous phase-change migration, where water evaporates from the seawater side, diffuses through a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane, and condenses into the electrolyte [135]. The porous structure of the PTFE membrane facilitates micron-scale gas diffusion for directional vapor transport while completely blocking liquid permeation and effectively suppressing seawater ion migration. The system demonstrated high efficiency, low energy consumption, and robust stability, operating continuously for over 3200 h at 250 mA/cm2 under ambient conditions. Furthermore, Xie et al. successfully implemented a wind-powered floating seawater electrolysis system (Figure 6) under dynamic marine environments (wave height: 0–0.9 m, wind speed: 0–15 m/s), achieving stable 240 h operation of a 1.2 Nm3/h hydrogen production unit, with stable impurity ion concentrations in the electrolyte over extended periods [15].

Figure 6.

Overview of the seawater direct electrolysis hydrogen production platform: (a) UPS module, current conversion module, seawater electrolysis module, H2 detection module and transportation module, (b) process diagram of the device [15].

Shen et al. proposed an anti-corrosion strategy of rare earth for kilowatt-scale alkaline seawater electrolyzers, where Eu2O3 (Europium(III) oxide) selectively adsorbs OH− to maintain a high pH anode environment while suppressing Cl− adsorption and oxidation [136]. Shi et al. designed a pH-asymmetric electrolyzer employing a Na+-exchange membrane, which leverages the chemical potential difference between different electrolytes and utilizes atomic-level dispersed Pt-anchored Ni-Fe-P nanowire catalysts to reduce voltage requirements and accelerate hydrogen evolution while simultaneously avoiding Cl− corrosion and Ca2+/Mg2+ precipitation [137]. Li et al. developed a thermodynamically favorable hybrid seawater electrolysis system featuring needle-like Co3S4 bifunctional catalysts that generate tip-enhanced electric field effects to promote sulfide ion oxidation reactions instead of chlorine evolution, achieving both energy-efficient hydrogen production and environmental remediation [138].

2.3. Coupling of Renewable Energy Generation with Hydrogen Production Systems

2.3.1. Integration of Offshore Wind Power with Hydrogen Production Systems

Offshore wind power coupled with water electrolysis presents an effective solution for renewable energy utilization by converting surplus wind electricity into storable green hydrogen during periods of low electricity prices or curtailment, simultaneously addressing wind power curtailment issues and enabling energy storage. This approach significantly reduces infrastructure costs associated with offshore power transmission while enabling large-scale green hydrogen production, as demonstrated by projects like the PosHYdon initiative. The key advantages of this integrated system include enhanced wind power utilization efficiency, improved grid flexibility, and the production of versatile clean energy carriers. Current technical challenges encompass offshore adaptability of electrolyzers (including corrosion and wave resistance), dynamic system response capabilities, offshore distance limitations, and costs related to equipment and hydrogen storage/transportation [31]. Compared to other offshore renewable energy sources, offshore wind benefits from over a century of onshore wind development experience, exhibiting the highest technological maturity, most established commercialization frameworks and policy systems, and the lowest LCOH [139], making wind-to-hydrogen integration the most extensively researched and implemented approach. Offshore wind resources offer superior quality with more stable and higher wind speeds compared to their onshore counterparts [140]. The electrolysis systems can be powered by either individual distributed or multiple centralized wind turbines, supporting simultaneous operations including system maintenance, seawater desalination, and hydrogen production.

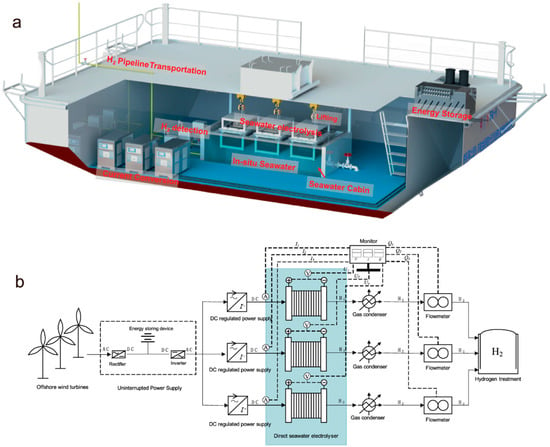

The integration of offshore wind power with water electrolysis primarily involves two scenarios: offshore and onshore electrolysis. Currently, three typical configurations for offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems exist as illustrated in Figure 7. (a) Distributed hydrogen production employs small-scale offshore electrolyzers (installed at the base of individual wind turbines) powered by single turbines, with hydrogen subsequently collected and transported to shore via ships or pipelines, offering lower energy transmission losses. This configuration maintains continuous large-scale hydrogen production even if individual electrolyzers or turbines fail, though maintenance costs increase. (b) Centralized production utilizes larger offshore electrolyzers (mounted on dedicated platforms or repurposed oil/gas structures) powered by multiple wind turbines within a farm, requiring hydrogen transportation via ships or subsea pipelines (including repurposed oil/gas pipelines) alongside power cables. However, high-power centralized electrolyzers demonstrate inferior performance when handling frequent start-stop cycles caused by wind power fluctuations, leading to accelerated electrolyzer degradation and bubble dynamics instability [141,142]. (c) Onshore electrolysis still relies on conventional offshore substations and subsea power cables, consuming terrestrial or coastal freshwater resources, but benefits from lower capital and maintenance costs compared to offshore installations. Notably, long-distance high-voltage power transmission may incur significant energy and hydrogen losses [143]. Among these approaches, distributed hydrogen production integrating single wind turbines with individual electrolyzers demonstrates the highest efficiency and lowest costs [139,143]. Representative projects include Europe’s HOPE project featuring a 10 MW PEM electrolyzer coupled with subsea hydrogen pipelines in a single-unit distributed configuration, the UK’s Dolphyn project incorporating PEM electrolysis and desalination equipment on each floating platform for hydrogen production and subsea pipeline transportation, and the Dutch PosHYdon project utilizing a 1.25 MW PEM electrolyzer with existing oil/gas pipelines for hydrogen delivery [7].

Figure 7.

Three configurations for offshore wind-powered hydrogen production are identified: (a) decentralized hydrogen production; (b) centralized hydrogen production; and (c) onshore hydrogen production [139].

Recent advances in offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems optimization demonstrate significant improvements in system configuration and operational efficiency. Gallo et al. developed a dynamic power regulation strategy for electrolyzers, revealing that variable power operation enables 168% higher optimal capacity compared to fixed-mode operation, with the key finding that switching to this mode when wind power meets minimum operational thresholds maximizes capacity utilization [144]. Castillo et al. conducted integrated simulations of a semi-submersible platform combining 15 MW wind turbines with electrolysis equipment, demonstrating negligible impacts on power generation and hydrogen production performance despite maximum pitch responses of 1° in floating platforms, while quantifying critical motion parameters for electrolyzers under typical operating conditions [145]. Dinh et al. established a differential evolution algorithm-based optimization method determining optimal electrolyzer capacity ratios, identifying 91.41% of installed wind power capacity as the ideal configuration for offshore systems [146]. Haqiqi et al. proposed coupling MED desalination with PEM electrolysis, demonstrating that waste heat from 1GW PEM systems (up to 94.12 MW) can power MED units to meet process water demands (except below 5% load conditions), thereby enhancing overall system efficiency [147]. Jiang et al. developed a Chance-Constrained Programming model incorporating electrolyzer degradation, wind power fluctuations, and stochastic equipment replacement costs for far-offshore projects, optimizing electrolyzer capacity to 336.1 MW (16.7% NPV improvement over conventional 360 MW designs) [148].

Economic analyses of offshore wind-hydrogen integration reveal critical cost determinants. Pegler et al. developed a techno-economic model for the Celtic Sea scenario incorporating eight 510 MW floating wind farms with integrated electrolyzers, demonstrating a LCOH of £ 7.25/kg·H2 (3–5 times higher than gray hydrogen), with particular sensitivity to electrolyzer efficiency and floating substructure costs, where wind power contributes 70–90% of LCOH [149]. Jin et al. proposed a co-optimization methodology for cable routing, hydrogen platform siting, and capacity allocation in offshore wind arrays, achieving total system cost minimization through efficiency improvements (1% efficiency gain reduces costs by 1.01%), highlighting the crucial role of electrolyzer efficiency and cable unit costs in economic optimization [150].

2.3.2. Integration of Marine and Solar Energy with Hydrogen Production Systems

Marine energy represents a significant renewable resource with an estimated global potential of 9.16 × 104 TWh, ranking third in generation capacity after wind and solar power [151,152]. This energy category encompasses tidal, wave, thermal gradient, and current energy (including tidal streams and ocean currents). Turbines can be deployed either as seabed-mounted installations or floating structures, typically anchored at depths of 40–100 m to harness underwater currents. While tidal energy has achieved commercial viability and tidal current energy has reached pre-commercial status, wave energy conversion remains in the research and demonstration phase. The technical approach for marine energy-based hydrogen production mirrors wind-to-hydrogen systems, utilizing tidal turbines to power electrolyzers and desalination units. However, current tidal power systems are limited to hundred-kilowatt scale generation capacity and exhibit considerable intermittency. Consequently, tidal-powered hydrogen production primarily serves offshore islands and platforms, providing sustainable hydrogen and freshwater supplies for remote communities [153].

Recent advances in marine energy-based hydrogen production systems demonstrate significant technological progress. Zhang et al. developed the first 4 kW integrated current energy-driven desalination-hydrogen production prototype, achieving stable PEM electrolyzer efficiency below 5.78 kWh/Nm3H2, while solving critical hardware integration challenges for direct-drive current turbines in multi-energy systems [61]. Driscoll et al. proposed a novel tidal phase-difference optimization method for green ammonia production around UK coastal areas, utilizing complementary tidal phases among islands to minimize low/zero-power periods through strategic turbine placement [154]. Omar et al. evaluated the performance and economics of a 10 MW hybrid ocean thermal energy conversion system coupled with alkaline/PEM electrolyzers, demonstrating a novel carbon-neutral approach for island regions through simultaneous energy-freshwater-hydrogen production without external water supply [155]. Ren et al. designed an integrated current energy-driven desalination-hydrogen production system featuring direct-drive transmission from turbine to seawater pump and permanent magnet synchronous generator, achieving 91% water-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency and implementing start-stop/MPPT cooperative control based on sinusoidal current characteristics to prevent frequent cycling [156].

Solar energy, despite its abundance and cleanliness, presents several challenges for hydrogen production applications. Although land-based photovoltaic (PV) technology has reached maturity, its conversion efficiency typically remains around 20% (lower than wind energy) and is susceptible to weather conditions, diurnal cycles, shading, soiling, and temperature variations [157]. Offshore PV systems face additional operational challenges including high humidity, saltwater corrosion, and wave impacts, without demonstrating the same offshore resource quality advantage observed in wind energy, and currently remain in the research and demonstration phase [157]. While promising for hydrogen production in arid coastal regions like the Middle East [158], offshore PV systems for water electrolysis—whether in centralized or distributed configurations—suffer from high equipment costs and significantly lower efficiency compared to offshore wind-to-hydrogen systems. The inherent intermittency and diurnal variability of solar radiation further limit its practical application. Current systems predominantly combine PV with PEM electrolyzers due to their compatible response times with solar fluctuations, though the resulting frequent start-stop cycles accelerate catalyst layer delamination and membrane thinning, ultimately reducing electrolyzer lifespan [159].

To effectively utilize offshore PV-generated electricity for hydrogen production, photovoltaic systems typically require integration with hybrid energy systems or energy storage technologies to compensate for intermittency. This approach not only enhances overall efficiency but also extends operational duration, thereby reducing curtailment losses [160]. The commercialization of offshore PV may benefit from existing offshore wind and marine energy infrastructure [161]. Hybrid energy systems offer distinct advantages by enabling complementary operation with other renewable sources, which helps mitigate output fluctuations from any single source while improving both power stability and generation capacity. Such systems allow shared utilization of electrical infrastructure, platform facilities, and maintenance resources. For offshore hydrogen production, hybrid energy systems can improve the economic viability of offshore power plants by further smoothing renewable power output fluctuations and minimizing electricity curtailment.

Recent studies have demonstrated significant advancements in optimizing hybrid marine renewable energy systems for hydrogen production. Rehman et al. applied a novel Dung Beetle Optimizer algorithm to co-design offshore wind-floating photovoltaic (FPV) hydrogen production systems, achieving a 29.2% reduction in LCOH compared to wind-only systems, with wind power equipment accounting for 45.96% of total investment [162]. Alex et al. developed a tidal-wind-grid coupled hydrogen production optimization method that eliminates 27.2 MWh/year of additional energy consumption through dynamic electrolyzer operation mode optimization and over-rating power strategies [163]. Ma et al. proposed a Hybrid Offshore Renewable Energy Harvesting System design integrating wave energy devices with monopile-steel plate composite foundations for offshore wind turbines [164]. Varotto et al. established an energy delivery and storage optimization model for hybrid wind-wave systems, demonstrating that combined cable expansion with subsea hydrogen pipelines yields optimal profitability, while ship-based hydrogen transport serves as a viable alternative when grid expansion is unfeasible [165]. Liu et al. developed a GIS-based multi-criteria evaluation framework incorporating geographical conditions, resource endowment, economics, risks, and sustainability to optimize siting of Hybrid Offshore Wind-PV-Wave-Hydrogen systems [166]. Hossain constructed a grid coordination analysis model for offshore wind-PV hydrogen systems, implementing intelligent optimization through dynamic power allocation strategies based on market prices and generation capacity [167]. Taroual employed RNN to assess Morocco’s wind-wave hybrid hydrogen potential, identifying an optimal 80% wave-20% wind energy mix [168].

3. Photocatalytic Seawater Splitting for Hydrogen Production

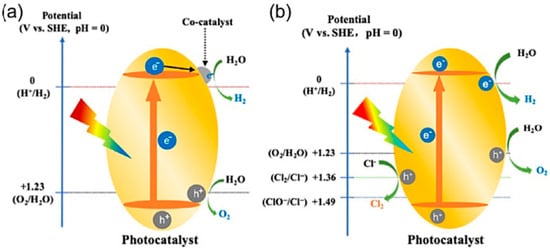

Photocatalytic seawater splitting represents a promising approach for direct solar-to-hydrogen conversion without requiring electricity generation. This technology utilizes transparent TiO2 photocatalytic films to decompose either seawater or atmospheric water vapor (at 70–95% relative humidity) under ambient temperature conditions when exposed to sunlight [169]. According to solid-state band theory, photon energy exceeding the semiconductor bandgap excites valence electrons to the conduction band, generating oxidative holes (h+) and reductive electrons (e−), as illustrated in Figure 8 [170]. The holes oxidize adsorbed water molecules or OH− to produce O2, while the electrons reduce H+ to form H2 [17]. The overall water splitting efficiency depends on three key factors: light absorption efficiency, charge separation capability, and surface reaction kinetics.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of photocatalytic water splitting systems: (a) pure water and (b) seawater [170].

While narrow-bandgap semiconductors (e.g., CdS (cadmium sulfide), ZnO) exhibit enhanced solar spectrum responsiveness, they suffer from photocorrosion and reduced reaction driving force. Conversely, wide-bandgap materials like TiO2 primarily absorb short-wavelength solar radiation, showing limited sensitivity to visible light and resulting in low solar-to-hydrogen efficiency (<10%) [171]. A more fundamental challenge lies in the significant timescale mismatch between nanosecond-scale charge carrier lifetimes and millisecond-scale water splitting reactions, causing substantial electron-hole recombination before they reach reaction sites. Common strategies to address this include (1) employing sacrificial agents (Na2SO3, Na2S, methanol, glycerol, or lactic acid) to rapidly consume holes and enhance charge separation and (2) utilizing cocatalysts (Pt, CuO, RhO2 (rhodium dioxide)) to selectively capture holes and improve reaction kinetics [171].

The advancement of photocatalytic seawater splitting technology primarily relies on the development and optimization of novel catalytic materials, currently dominated by TiO2-based, g-C3N4-based [172], and other oxide-type (WOx, ZnO) catalysts [173]. Current research focuses on several efficiency-enhancing approaches: (1) developing broadband photocatalysts to extend light absorption from UV to visible spectrum. (2) Employing advanced modification techniques like atomic doping and quantum dot decoration to improve both light harvesting efficiency and quantum yield. (3) Engineering nanostructured catalysts with increased surface area for enhanced hydrogen evolution rates. (4) Implementing photothermal synergistic catalysis [174]. Incorporating Ag and SiO2 nanoparticles into TiO2 photocatalysts creates nanocomposites capable of significant localized thermal energy conversion, which promotes both photocatalytic and desalination processes at the interface, resulting in a 5.2-fold hydrogen production increase compared to conventional TiO2 systems [175]. Porous Mo- or B-doped BiVO4 photoanodes demonstrate substantially improved photocurrent density and seawater stability through enhanced conductivity and hole diffusion length, while exhibiting remarkable resistance to photocorrosion [176].

Barrera et al. developed a novel equivalent circuit detailed balance model framework incorporating target and competing reactions’ electrochemical load curves, enabling the first load-line analysis for reaction selectivity prediction. Their study revealed that systems with semi-transparent light absorption layers outperform single absorbers under mass-transfer-limited conditions, with selective hydrogen production achieved by regulating mass-transfer asymmetry of redox mediators (e.g., Fe-based mediators) [177]. Wang et al. significantly enhanced g-C3N4 photocatalytic performance through thermochemical treatment and phosphorus intercalation doping, achieving a hydrogen evolution rate of 6323 μmol g−1h−1 and 5.08% quantum efficiency at 420 nm [178]. Zhang et al. engineered segregated charge centers in COFs comprising cationic frameworks and iodide anions, where the ionic polarization strategy created a strong built-in electric field enabling the CH3I-TpPa-1 material to reach 9.21 mmol g−1h−1 hydrogen production rate (42-fold enhancement) without cocatalysts [179]. Zhou et al. utilized hydrophilic 1D microporous channels in hydrogen-bonded organic framework HOF-H4TBAPy to reduce exciton transport distance to 1.88 nm, achieving exceptional hydrogen production (358 mmol g−1h−1) in sacrificial systems when microchannel length was ≤0.59 μm [180].

Recent advances in photocatalytic systems have demonstrated innovative designs for efficient hydrogen production. Collins et al. developed a Z-scheme photocatalytic reactor incorporating layered semiconductor nanoparticles to form dual light-absorption layers, which coupled hydrogen and oxygen evolution half-reactions through solution-phase redox mediators, significantly reducing both production costs and carbon emissions [181]. Lee et al. engineered a floating photocatalytic platform based on porous elastomer-hydrogel nanocomposites (featuring single-atom Cu/TiO2 systems) that achieves efficient light transmission, rapid water supply, and immediate gas separation through its unique air-water interface structure [182]. Pornrungroj et al. integrated UV-responsive RhCrOx–Al:SrTiO3 photocatalysts with visible-infrared absorbing floating porous carbon-based solar vapor generators to create an off-grid system capable of simultaneous hydrogen production and water purification [183].

Photocatalytic seawater splitting faces significant challenges due to seawater’s complex composition [184]. While low chloride concentrations can suppress electron-hole recombination (Figure 8), high ionic concentrations induce catalyst poisoning (accelerating photocorrosion) and even cause lattice distortion [185]. Cations (Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+) adsorb onto catalyst surfaces, blocking active sites and forming precipitates, while SO42− competes with H+ reduction, wasting 30% of photogenerated electrons and reducing hydrogen selectivity [186]. Several innovative solutions have emerged: Yuan et al. developed CoOx nanocages with dynamic Co2+/Co3+ reconstruction to consume holes while Pt single atoms trapped electrons, achieving 23.88 mmol g−1 h−1 hydrogen production with remarkable corrosion resistance [187]. Li et al. employed electrolyte-assisted charge polarization on N-doped TiO2, where selective ion adsorption extended carrier lifetimes 5-fold, enabling 15.9% energy conversion efficiency at 270 °C [188]. Zhang et al. fabricated ZIS/PAN nanofiber membranes via electrospinning, where surface cyano groups captured ions, boosting activity 20% over aqueous solutions while solving catalyst recovery issues [189]. Nasir et al. integrated Pd nanoparticles (as hole extractors) with GaN (gallium nitride) nanowires on silicon, simultaneously producing hydrogen and H2O2 from seawater [190]. Zhao et al. designed stainless steel-TiO2 bilayer structures where chromium-doped NiFe(oxy)hydroxides served as dual-functional protective cocatalysts for oxygen evolution and corrosion prevention [191]. Zhu et al. created self-suspending organic photocatalysts with superwetting interfaces and gradient heterojunctions for efficient solar seawater splitting [192].

4. Biological Hydrogen Production from Marine Resources

Marine biohydrogen production has emerged as a promising approach in renewable energy research, utilizing specific algae and bacteria to convert seawater and organic substrates into clean hydrogen through their inherent metabolic activities. This technology offers dual advantages by harnessing Earth’s most extensive ecosystem while combining environmental remediation with renewable energy generation. Notably, the process eliminates freshwater pretreatment requirements and can utilize various marine substrates including aquaculture sludge, carbohydrates, and algae, thereby reducing cultivation costs while enabling sustainable conversion of marine resources into green energy.

Photobiological hydrogen production in algae involves sunlight-driven water splitting catalyzed by endogenous enzymes. Hydrogenase is a key microbial enzyme that efficiently catalyzes the reversible reduction in H+ to molecular H2, serving as a central catalyst in both photobiological and fermentative marine biohydrogen production pathways. However, oxygen evolution during photosynthesis inactivates hydrogenase enzymes, thereby terminating hydrogen production [193]. Current strategies focus on suppressing oxygen evolution or creating anaerobic conditions to maintain hydrogenase activity. Two key enzyme systems facilitate algal hydrogen production: nitrogenases and reversible hydrogenases. In cyanobacteria, H+ generated from water photolysis are primarily consumed by nitrogenases for ammonia synthesis rather than hydrogen production, resulting in low hydrogen yields [194]. Notable hydrogen-producing marine cyanobacteria include Oscillatoria brevis, Oscillatoria sp. Miami BG7, and Calothrix scopulorum. In contrast, green algae employing reversible hydrogenase systems demonstrate superior catalytic efficiency and hydrogen production rates [195], with representative species including Tetraselmis, Platymonas subcordiformis, and Chlorella [196,197,198].