1. Introduction

The current global energy system faces multiple challenges, including excessive consumption of traditional energy sources, environmental pollution, and rising carbon emissions. To address these issues, numerous countries and regions have reached a consensus in recent years, committing to achieving net zero targets [

1]. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2025 report, the growth rate of energy sources represented by renewables has risen to 38%, making it the world’s fastest growing energy category [

2]. This indicates that modern power systems are gradually shifting from centralized supply architectures towards more environmentally friendly and sustainable distributed energy frameworks. Within this context of energy transition, microgrids are one of the key developmental trends.

A microgrid is a small-scale power system that typically comprises energy sources, loads, energy storage systems, distribution networks, protective equipment, and control systems. Its primary objective is to ensure stable power, voltage, and frequency within the system [

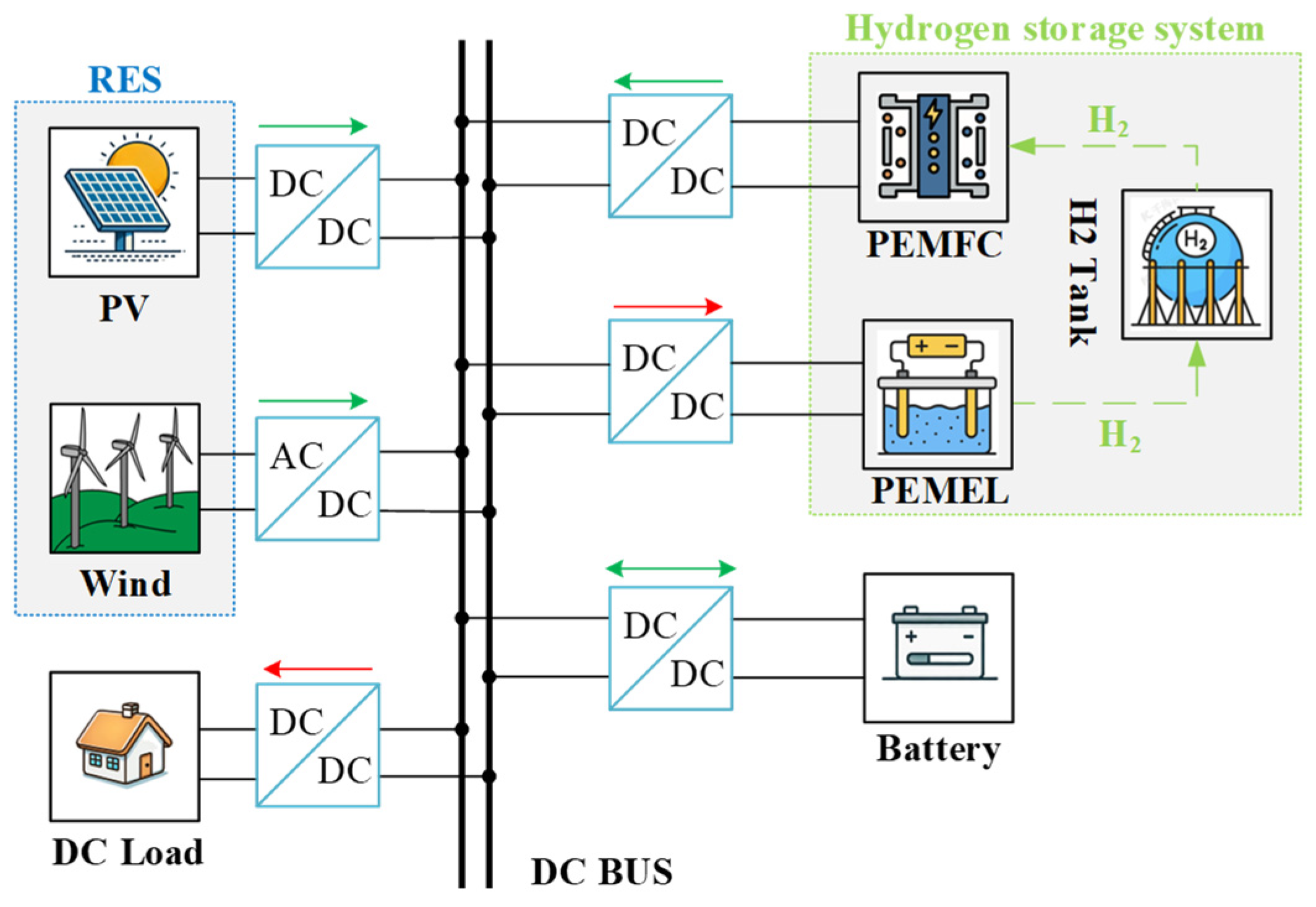

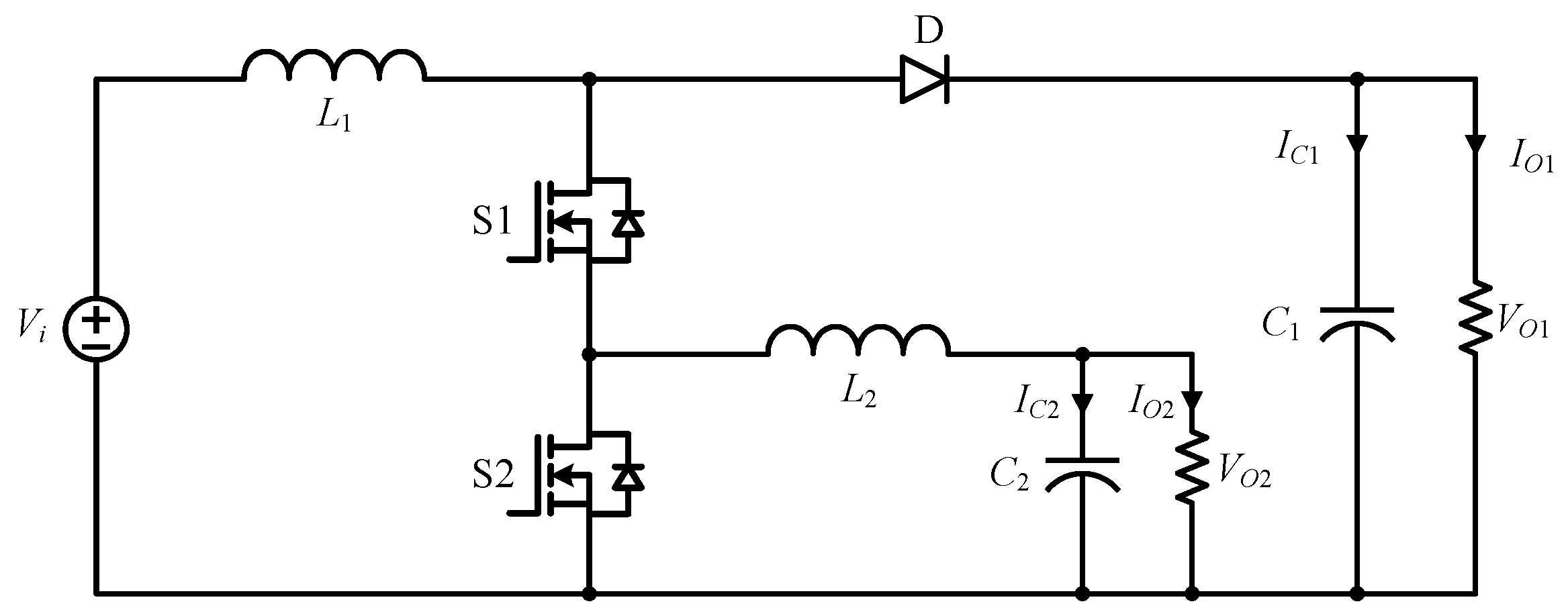

3]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, certain microgrids may connect to the main grid via a static transfer switch (STS) at a public coupling point (PCC). From the perspective of the main grid, a microgrid can be regarded as a single controllable unit. It exports power to the main grid during generation surpluses and imports power from the main grid during generation shortfalls. Furthermore, the microgrid can actively disconnect from the main grid to achieve independent operation in the event of power quality deterioration or if faults occur. Currently, microgrids possessing independent operation capabilities are attracting increasing attention and are commonly referred to as island, standalone, or self-sufficient microgrids.

Many mainstream renewable energy technologies, such as PV and FC, inherently generate direct current (DC) power. Additionally, modern electrical devices, including electric vehicles, computing equipment, and LED lighting systems, typically require DC input [

4]. This inherent alignment between generation and consumption has led to increasing interest in DC microgrids, which feature simpler architectures and eliminate the need for complex synchronization controls. Furthermore, the adoption of DC microgrids substantially reduces the number of energy conversion stages relative to conventional AC microgrids [

5]. This simplification lowers system energy losses and enhances overall energy efficiency.

However, due to the inherent intermittency and randomness of renewable energy sources (RES), their output alone is insufficient to consistently and reliably meet load demands. Consequently, energy storage systems have become essential components in DC microgrids. Of current technologies, chemical batteries represented by lithium-ion types have been widely adopted for short- and medium-term energy storage scenarios, benefiting from their high energy density and rapid response capability [

6]. Nevertheless, the suitability of these batteries is constrained by factors including self-discharge characteristics, substantial initial investments, and ongoing maintenance expenses when meeting seasonal and long-term storage demands [

7].

Against the backdrop of growing demand for long-term energy storage, hydrogen storage technologies have attracted considerable attention in recent years. Hydrogen features high energy density, zero emissions, long-term economic storage capability, and low maintenance costs, effectively addressing the shortcomings of existing long-duration storage technologies [

8]. In hydrogen-based DC microgrid energy storage systems, surplus renewable electricity is converted into hydrogen gas through proton exchange membrane electrolyzers (PEMEL), subsequently reconverted into electrical energy via FC as required. This process facilitates efficient, clean, and long-term energy storage and supply.

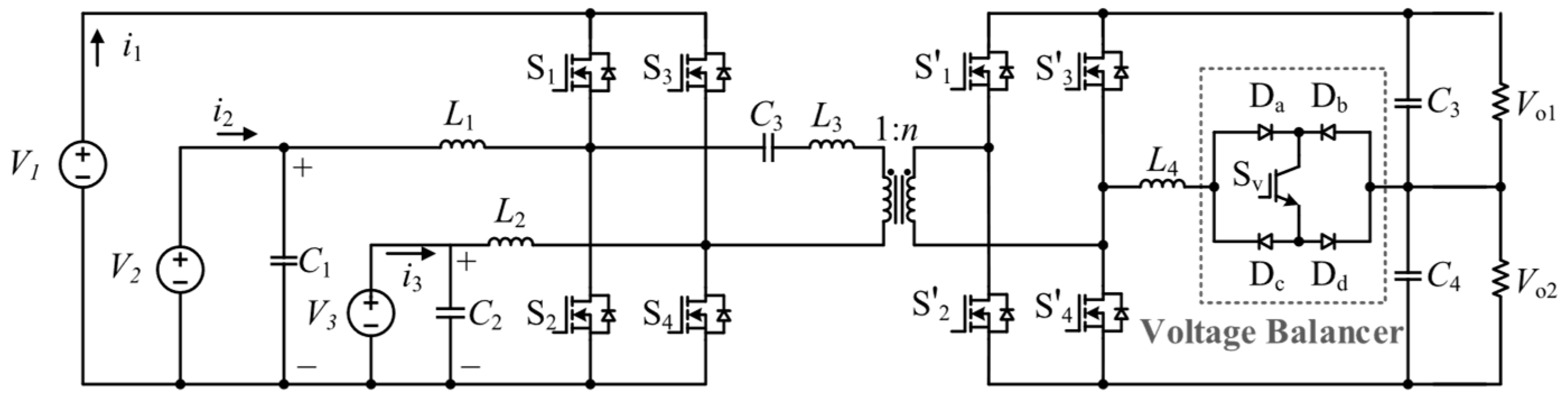

Figure 2 illustrates a representative hydrogen-based DC microgrid architecture that integrates generation units, storage units, and loads. These components are controlled via individual power converters and connected to a common DC bus for energy distribution and transmission. This approach has garnered attention for its plug-and-play functionality and strong scalability. However, as the number of integrated units increases, employing multiple individual converters significantly increases the structural complexity of the overall system, thereby posing considerable control challenges and reducing operational efficiency.

To achieve more efficient coordinated control and flexible integration of diverse energy sources and energy storage devices within DC microgrids, the development of novel power electronics interface technologies has emerged as a research priority. As illustrated in

Figure 3, multi-port converters (MPC) have garnered significant attention from both academia and industry in recent years. This is due to their ability to simultaneously integrate renewable energy generation units and energy storage units, flexibly control power flow between ports, and enable modular system design.

Compared with conventional architectures that employ multiple individual converters, multi-port converter-based microgrids offer a more compact and integrated system design. This configuration effectively reduces the number of voltage conversion stages in renewable energy systems, leading to lower system complexity, smaller physical scale, and reduced construction costs [

9]. In addition, certain multi-port converter topologies can provide electrical isolation between ports when required, thereby enhancing the operational safety of distributed energy systems.

The primary objective of this paper is to review the characteristics of mainstream distributed energy sources (DER) within a hydrogen-based DC microgrid, the requirements they impose on multi-port converters, and the predominant topologies of multi-port converters in current research. Specifically, it covers the technical features, advantages, and application challenges of both isolated and non-isolated architectures, whilst analyzing their applicable scenarios to clarify future research directions and technological development opportunities.

2. Classification of DER Types

In hydrogen-based DC microgrids, typical DERs include renewable generation units such as PV, WT, and FC. DERs also comprise energy storage subsystems, including BESS and PEMEL. Since these DERs differ in their operation characteristics, it is necessary to examine their power flow pathways, dynamic response behaviors, and power quality requirements in order to define the functional specifications that multi-port power converters must satisfy. This section classifies DERs according to their functional roles within the microgrid and reviews the characteristics of each category.

2.1. Photovoltaic Generation Unit

As shown in

Figure 4, the PV port exhibits stochastic power variability and strong I-V nonlinearity, which complicate DC bus regulation and multi-port power coordination [

10]. Operating the array consistently at its maximum power point is essential; however, converter-induced current/voltage ripple and transient disturbances can displace the operating point from the MPP, degrading energy capture [

11]. A pronounced voltage-level mismatch also exists: PV modules provide low and variable DC (often <60 V), whereas building/campus DC buses commonly run at ~380–400 V, necessitating high and controllable step-up conversion with good efficiency over a wide input range [

12]. Consequently, stand-alone PV rarely satisfies the load alone and is typically coordinated with BESS/FC/SC to stabilize net power and bus voltage within multi-port architectures.

Accordingly, the PV interface within MPC-based microgrids should meet the following standards:

- (1)

High-gain step-up with wide input operability: It should deliver a sufficient conversion ratio and efficiency across irradiance/temperature-driven voltage spread to match the DC bus; isolation may be adopted when voltage matching and safety margins require it;

- (2)

Low input-current ripple: Maintaining low input-current ripple effectively suppresses ripple-induced deviations from the maximum power point (MPP), thus stabilizing power extraction efficiency from the PV port;

- (3)

Fast dynamic response: A fast, well-damped transient response limits disturbances propagated to the DC bus during multi-port coordination, preventing PV-side dynamic interactions from exacerbating DC bus voltage fluctuations.

2.2. Wind Generation Unit

Wind turbine (WT) generation units, commonly integrated within hydrogen-based DC microgrids, produce variable-frequency AC voltage that requires rectification and voltage step-up before feeding into the DC bus. However, the inherent stochastic nature of wind introduces unpredictable dynamics, leading to frequent DC link voltage fluctuations and degraded power quality. Although the mechanical inertia of turbines slightly buffers transient power variations, this natural damping alone cannot fully mitigate the rapid electrical fluctuations induced by wind speed changes [

13]. Consequently, these residual electrical disturbances require precise converter controls to maintain stable DC bus operation and suppress voltage deviations. Additionally, the type of rectifier employed influences ripple characteristics. Multi-pulse diode or thyristor rectifiers generate low-frequency ripple components related to pulse number, while PWM active rectifiers shift the ripple into the switching frequency band [

14]. Furthermore, converter topologies capable of extracting maximum power over a broad operating range are essential to achieve efficient power transfer and voltage-level matching.

Accordingly, the WT interface within MPC-based microgrids should meet the following standards:

- (1)

AC/DC–DC/DC interface conversion: The WT port should include an AC–DC rectifier followed by a regulated DC–DC stage that converts the variable-frequency low-voltage output of the generator to the specified DC bus voltage level. Topology selection should cover the full generator voltage range and meet the bus regulation target.

- (2)

Maximum power extraction and power smoothing: The WT port should implement MPPT and coordinate with energy storage units to limit DC bus deviation and meet dynamic performance criteria during wind variations.

- (3)

High gain and wide operating range: The WT port should provide a high, controllable step-up ratio across a wide input voltage range to achieve the required gain at moderate duty cycle while constraining device voltage stress and input current ripple.

2.3. Fuel Cell Generation Unit

Fuel cells (FC) convert stored hydrogen into electrical energy and serve as critical generation units in hydrogen-based DC microgrids. However, they exhibit slow dynamic response and pronounced V–I nonlinearity owing to inherent electrochemical polarization effects [

15]. Therefore, FC faces challenges in providing instantaneous high-power support. PEMFCs behave as low-voltage sources with voltage droop under a rising current. Because a single cell typically operates at around 0.6–0.7 V, stacks deliver only tens of volts, necessitating high step-up DC–DC conversion to meet typical DC bus requirements [

16]. Achieving this with a conventional boost converter requires operation at high-duty cycles, which significantly elevates device stress and switching/conduction losses. Simultaneously, the FC-side input current must increase to maintain bus power, exacerbating ripples, EMI, and thermal management burdens. To sustain this higher power, the front-end step-up stage necessarily draws a more pulsating input current under finite inductance and high-duty cycles. This amplifies both low-frequency and switching band components, which raise FC losses, hasten degradation at high currents, and couple onto the DC bus to impair power quality [

17].

Accordingly, FC port design within MPC architectures should ensure the following:

- (1)

Unidirectional energy flow design: As PEMFCs function as energy-supplying sources, their interface converters should exhibit unidirectional power flow characteristics, delivering energy from the fuel cell to the DC bus;

- (2)

High-gain, high-current conversion design: As PEMFCs operate under voltage depression and large average current conditions, their interface converters should feature high-gain and high-current capability with low input-current ripple, maintaining efficiency and operational safety;

- (3)

Ripple mitigation and EMI control design: As PEMFCs are sensitive to harmonics and ripple currents, their interface converters should include effective filtering, modulation schemes, and operating mode selection to minimize ripple-induced losses and prevent DC bus contamination;

- (4)

Transient buffering and coordinated control design: As PEMFCs exhibit slow dynamic response, their interface converters should incorporate transient buffering mechanisms and coordinated control with energy storage units to limit direct load impact on the stack and reduce DC bus regulation burdens.

2.4. Battery Storage Unit

In hydrogen-based DC microgrids, battery energy storage (BESS) provides bidirectional buffering that stabilizes the DC bus and smooths renewable variability. However, characteristics of BESS impose fundamental limits. Self-discharge undermines long-duration large-scale storage, while repeated cycling causes capacity fade and increases internal resistance; moreover, terminal voltage and impedance vary with state of charge and temperature [

18]. These behaviors impose stringent requirements for the converter port. First, the BESS terminal voltage varies widely with SOC, temperature, and aging, while the DC bus voltage of the microgrid is maintained around a nominal setpoint. Consequently, the interface must furnish efficient wide-range buck–boost regulation to manage voltage mismatch across operating conditions [

19]. Second, BESSs are sensitive to superimposed current ripple originating from source/load fluctuations (low frequency) and switching actions (high frequency); without proper mitigation, this ripple elevates internal heating, accelerates capacity fades and increases impedance. These effects propagate disturbances to the DC bus, degrading overall power quality [

20]. Third, parallel packs exhibit module heterogeneity (capacity, impedance, temperature, aging); without robust current sharing, current limiting, and SOC balancing, circulating currents and uneven distribution arise, causing localized hot spots, reduced usable capacity, and accelerated degradation [

21].

Accordingly, the BESS interface within MPC-based microgrids should meet the following standards:

- (1)

Bidirectional power flow and DC-link stabilization: The BESS interface should support bidirectional energy exchange, enabling charge and discharge coordination to buffer renewable and load fluctuations while maintaining fast, well-damped DC bus voltage regulation;

- (2)

High-efficiency wide-range power conversion: The converter must sustain high efficiency across a broad input–output voltage span, accommodating variations in battery SOC and temperature while matching the fixed high DC bus voltage level;

- (3)

Ripple suppression and lifetime enhancement: Effective ripple reduction is required to minimize battery current ripple, thereby mitigating thermal stress and aging effects while preserving DC bus power quality.

2.5. Electrolyzer Unit

PEMEL is an energy consumption unit in the hydrogen DC microgrid, functioning as a load that draws electrical energy from the microgrid and outputs hydrogen energy. The hydrogen production rate of a PEMEL is approximately linearly proportional to its input DC, making current become the primary control variable [

22]. PEMEL features rapid start-up and ramping capabilities, enabling power adjustments within seconds to minutes. While this flexibility aids in matching renewable energy fluctuations, it also introduces reliability concerns. Frequent dynamic loading accelerates membrane and electrode degradation, and sudden pressure fluctuations impose mechanical stresses that impair performance [

23]. These operational characteristics influence the design of interface converters. Since a single PEMEL stack typically operates around 30 V, a step-down from the DC bus voltage is required [

24]. Consequently, conventional single-stage buck converters operate at very small duty ratios, which results in narrow control margins, higher switching and conduction losses, and increased inductor and bus current ripple [

25]. Therefore, due to the nonlinear I–V characteristics of the electrolyzer stack and its sensitivity to current ripple, superimposition can shift the operating point and reduce efficiency. Furthermore, long-term ripple exposure increases both contact resistance and high-frequency resistance, so the ripple must be tightly limited [

26]. Rapid tracking of dispatch commands remains essential. To safely achieve this rapid response, ramp rates and operational constraints must be explicitly defined. Otherwise, renewable power fluctuations may propagate into the stack, reducing hydrogen production during transient periods and increasing safety risks.

Considering the operational characteristics and limitations of PEMEL units, the following specific requirements should be addressed when designing the associated interface converters:

- (1)

Wide voltage range and high step-down capability: The PEMEL interface converter must accommodate wide input voltages and achieve a high step-down ratio, often requiring multi-stage or specialized topologies due to efficiency constraints of traditional single-stage buck converters;

- (2)

Current ripple control: The PEMEL interface should minimize output current ripple using advanced filtering, interleaved structures, or multiphase techniques to enhance electrolysis efficiency and extend component lifetime;

- (3)

Appropriate dynamic response control: The PEMEL interface converter requires suitable dynamic responsiveness to rapidly implement system energy scheduling instructions, effectively stabilizing current variations without compromising hydrogen production efficiency or component lifespan.

2.6. Supercapacitor Storage Unit

Supercapacitors provide millisecond-level response and low ESR, which enables short-term buffering to smooth power and voltage in DC microgrids. They compensate for the slower dynamics of distributed energy resources, improving transient ride-through and system stability [

27]. These benefits also introduce converter design burdens that arise from the device’s dynamics. The terminal voltage varies widely with state of charge. The interface must operate across a broad input range and maintain an adequate conversion ratio. Operation near extreme duty cycles can reduce efficiency and narrow control stability margins [

28]. Because the ESR of the SC is very low, the SC behaves almost like a short circuit at a low SOC (near-zero terminal voltage) when connected to the DC bus. A similar condition occurs when the converter’s voltage or current setpoint is stepped upward. In both cases, the resulting surge current and high di/dt elevate stress on semiconductors and the DC bus, potentially causing fluctuations or instability in the DC bus voltage. Frequent high-current cycling further increases current stress and complicates thermal management, and inadequate regulation can aggravate transient bus deviations and degrade power quality. In practice, these effects appear as bus voltage ripple and as nonlinear V–I deviations linked to SOC-dependent voltage and controller saturation near operating limits [

29].

Therefore, when connecting SC to a hydrogen-based DC microgrid, the design of the interface converter needs to focus on meeting the following performance requirements:

- (1)

Bidirectional power flow capability: Supercapacitors can both absorb energy from the DC bus for charging and release energy to the bus for discharging. Therefore, the interface converter must support the bidirectional flow of energy between the bus and the supercapacitor;

- (2)

Wide range of voltage: The terminal voltage of the SC varies significantly with SOC; therefore, the interface converter should possess the capability to operate across a wide input voltage range to ensure effective voltage boosting and stable operation under low-voltage SC conditions;

- (3)

High surge current tolerance: SC can instantly provide/absorb large currents, so their interface converters must have corresponding high surge current carrying capacity. Topologies such as multi-phase interleaved parallel connection can be used to reduce current ripple and device stress, ensuring operational stability during charging and discharging;

- (4)

High efficiency and fast dynamic response: The interface converter needs to have high efficiency to reduce energy loss caused by frequent charging and discharging. At the same time, it should achieve fast dynamic response to effectively suppress transient power fluctuations and improve the overall operational stability of the microgrid.

Based on the above analysis,

Table 1 summarizes the power flow characteristics, critical operational issues, and corresponding interface design requirements of various distributed energy resources in hydrogen-based DC microgrids.

The diversity of the above-mentioned distributed energy resources places demands on power electronic interfaces in terms of multi-port connectivity and flexible power allocation. From the perspective of power flow, the microgrid incorporates unidirectional generation-only sources (e.g., PV, WT, and FC), load-only or energy-consuming units (e.g., PEMEL), and bidirectional storage units capable of charging and discharging (e.g., BESS and SC). In particular, the hydrogen-based energy system integrates PEMFC generation units and PEMEL electrolysis units to achieve energy storage and utilization. It is noteworthy that PEMEL differs from other common distributed energy generation units by typically employing buck converters for its interface, whereas common generation units usually require boost converters. Consequently, the design of multi-port converters must address both the diversity of interfacing ports and the complexity inherent in system integration. Detailed converter topologies and corresponding design considerations will be comprehensively discussed in the architecture review of multi-port converters.

3. Multi-Port Converter Architecture

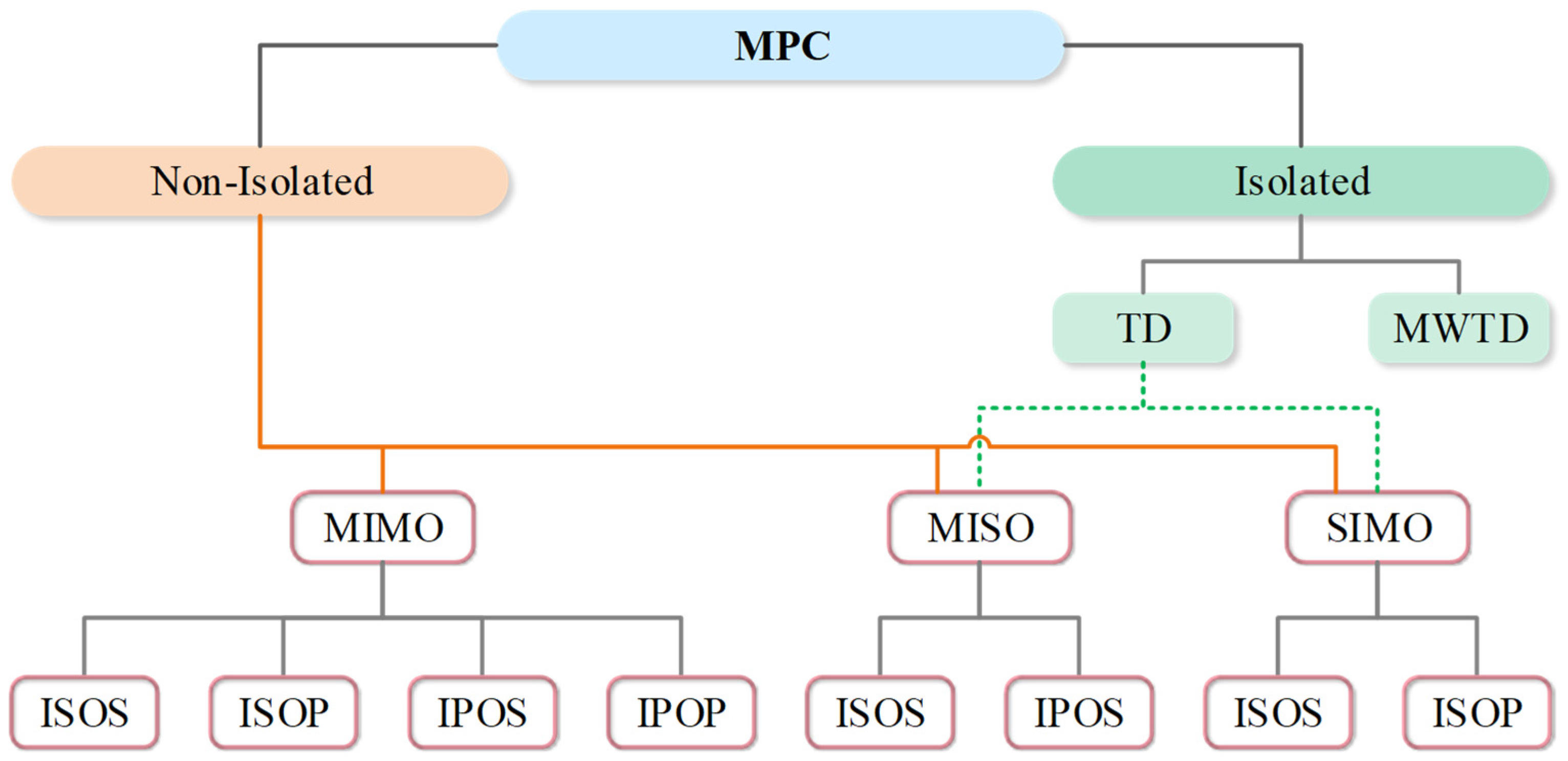

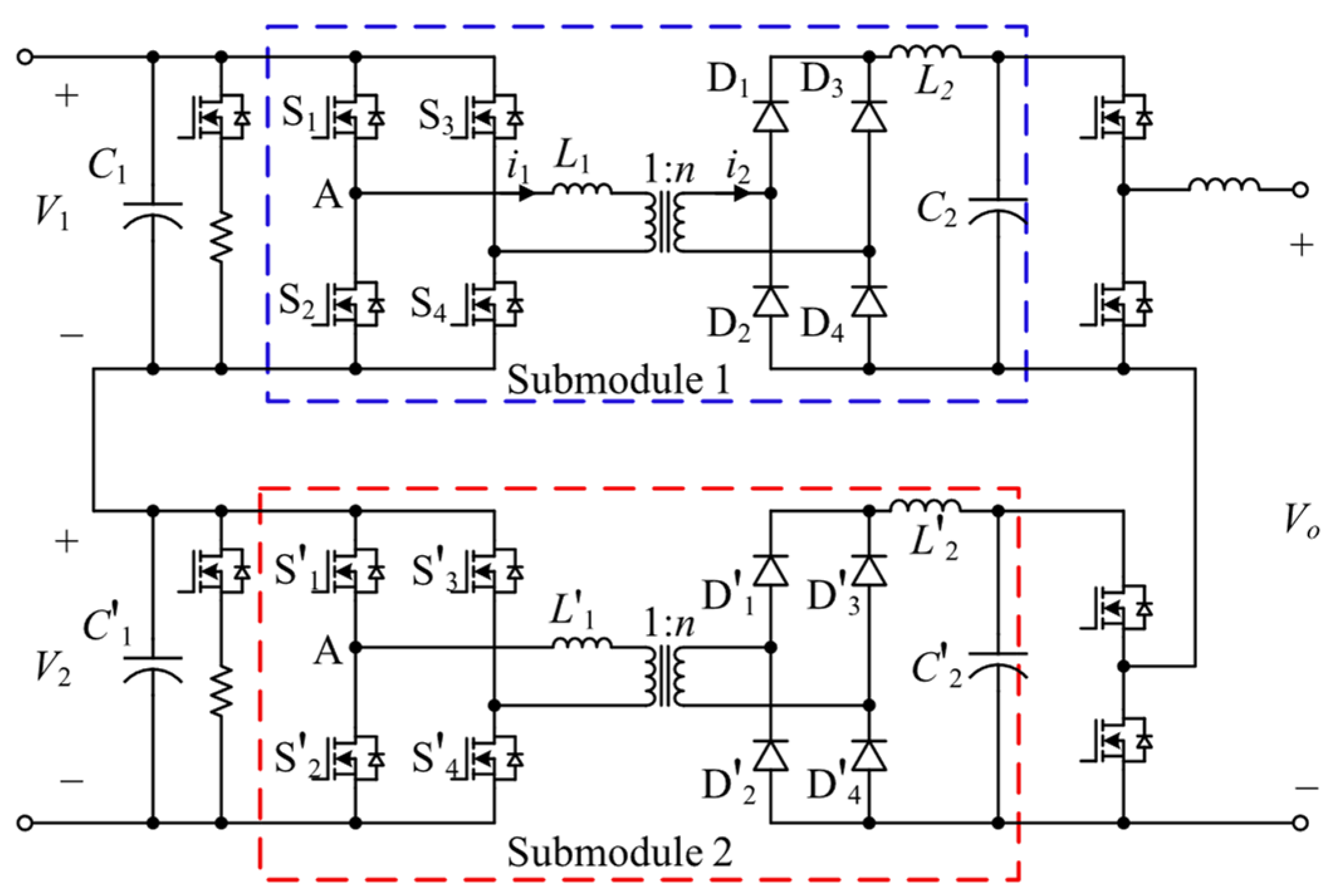

In this section, the MPCs are systematically classified according to the structure presented in

Figure 5. MPCs are first categorized into non-isolated and isolated types based on the presence of galvanic isolation. Non-isolated MPCs are further subdivided into three groups according to their port configurations: multi-input multi-output (MIMO), multi-input single-output (MISO), and single-input multi-output (SIMO). These groups can also be categorized according to their circuit characteristics into configurations such as input-series output-parallel (ISOP), input-parallel output-series (IPOS), input-parallel output-parallel (IPOP), input-series output-series (ISOS). Isolated MPCs are divided into two groups based on transformer implementations: multi-winding transformer-derived (MWTD) architectures, which inherently increase the number of ports by adding transformer windings; and topology-derived (TD) architectures, which utilize transformers with a fixed winding configuration. It is notable that TD architectures offer extensive composability by integrating non-isolated stages. Specifically, various non-isolated MISO topologies can be flexibly connected to the transformer’s primary side, while multiple SIMO topologies can be attached to its secondary side. This configurational flexibility of TD is indicated by dashed connections in

Figure 5. Subsequent sections provide a detailed discussion of representative circuits, their key characteristics, and specific application scenarios based on this classification framework.

3.1. Non-Isolated Multi-Port Converter Architecture

3.1.1. Multi-Input Single-Output

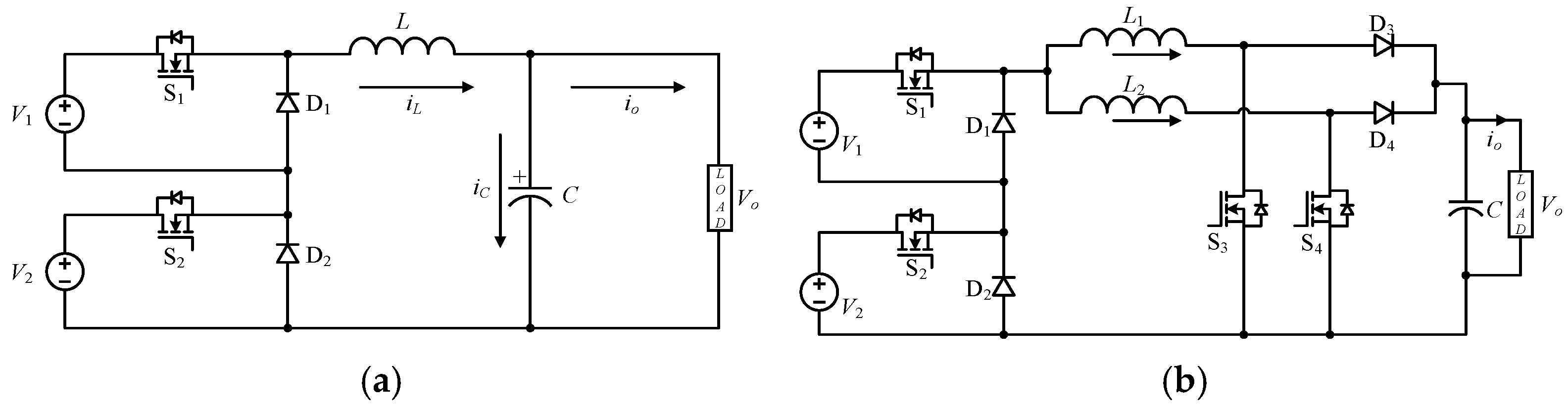

The fundamental design concept of the non-isolated “Series expansion” multi-input single-output (MISO) converter is to series-connect multiple DC sources through individual unidirectional diodes ahead of a common power stage. The shared post-stage then performs energy processing and voltage regulation. The topology can be directly obtained by extending classical single-input converters:

Figure 6a shows the buck-derived multi-port converter [

30], and

Figure 6b shows the boost-derived multi-port converter [

31]. The series diode network decouples the sources and suppresses reverse currents, while the back end shares the magnetic and filtering components, keeping the hardware scale and control organization within practical bounds. Consequently, this architecture is suitable for source-side voltage stacking with centralized post-stage regulation.

For non-isolated “diode-series-extended” MISO MPCs, current key research focuses primarily on optimizing devices and operating modes for higher efficiency and lower ripple, including introducing continuous input/output current paths and phase management in boost-type MISO to reduce source-side current ripple and improve static/dynamic performance metrics [

32,

33]; and small-signal modeling and multi-switch coordination control in buck-type MISOs to mitigate stability and dynamic performance issues arising from multiple input duty cycle coupling [

34,

35]. To accommodate high-gain and wide-range bus requirements, multi-stage MISO boost/buck configurations have emerged, embedding high-gain switching networks within conventional boost/buck power stages to enhance boost/buck ratios while limiting device stress [

36,

37]. To further reduce device stress and input-side ripple, some implementations employ multi-phase interleaving at each input port alongside common-source coupling inductors, canceling ripple and sharing current [

38,

39]. Throughout these evolutions, the core characteristic of “front-end diode-based input decoupling together with a single shared output power stage” has been maintained at the circuit level.

The concept of parallel-expanded MISO multi-port converters involves the establishment of multiple independent input ports by configuring the input stages in parallel at the front end of the primary power stage. Each port employs its intrinsic power conversion unit to feed into a common filtering network or DC bus, which is regulated by a centralized voltage controller.

Figure 7a illustrates a typical parallel-type multi-port converter topology derived from boost converters, in which currents from multiple input ports converge at the common output capacitor [

40].

Figure 7b demonstrates another parallel-type multi-port configuration evolved from Ćuk converters [

41]; each parallel input port independently couples to a shared output stage through its dedicated Ćuk power stage, utilizing energy transfer capacitors and inductors to achieve port decoupling while concurrently sharing the post-stage filtering network. Such parallel integration approaches offer distinct advantages in terms of reduced component count, compact size, and enhanced energy integration capability.

Current research on non-isolated “parallel expansion type” MISO MPCs is described in the following. At the circuit level, studies aim to enhance the voltage gain and efficiency of parallel connected systems through high-gain and high-power density designs. Typical approaches include combining parallel MISO-Boost topologies with multiple boost stages and coupled inductors to achieve higher voltage gains. Using soft switching technologies such as ZVS can reduce switching losses and device stress, improving power density while maintaining multi-port parallel integration [

42,

43]. For sources sensitive to current ripple, such as fuel cells, research has been conducted on reducing source-side ripple through phase-interleaved parallel connection and superimposing ripple compensation networks. At the same time, the structural advantages of continuous input current in Ćuk/SEPIC/modified ZSI and other similar topologies are utilized to further reduce ripple and EMI [

44,

45,

46]. Some studies have explored the integration of passive resonant components into parallel-extended MISO MPC topologies. This technique broadens the ZVS operating range and effectively reduces input/output ripple currents without introducing additional active auxiliary switches, thereby improving the overall operational efficiency and reliability of the MPC [

47,

48]. In summary, current research for non-isolated parallel-extended MISO MPCs focuses on improving overall boosting performance and efficiency through advanced high-gain, high-power density designs, and reducing input ripple and EMI by means of phase interleaving and ripple compensation networks. The soft-switching operational range can be extended further by passive resonant elements to further enhance system efficiency and reliability.

In the application of a hydrogen-based DC microgrid, the MISO architecture effectively integrates various distributed energy sources such as FC, PV, BESS, and SC, and uniformly connects them to a common DC bus. Of these, the interleaved boost topology has been applied to fuel cell applications, using ripple compensation and phase interleaving techniques to reduce the current ripple at the FC port, thereby improving the operating efficiency and stability of the fuel cell [

33,

46]. Furthermore, novel three-input boost topologies have been developed for hybrid scenarios involving PV, FC and BESS, facilitating flexible power allocation and coordinated control among multiple input ports through a unified voltage boost stage. This approach effectively addresses the demands of multi-source integration and dynamic power management within hydrogen-based DC microgrids [

49,

50]. Additionally, continuous current topologies such as Ćuk, SEPIC, and modified ZSI have been investigated due to their inherent smooth and continuous input–output current characteristics. These topologies effectively mitigate current ripple impacts on electrolyzers and fuel cells, thereby extending equipment lifespan and enhancing overall system efficiency [

51,

52].

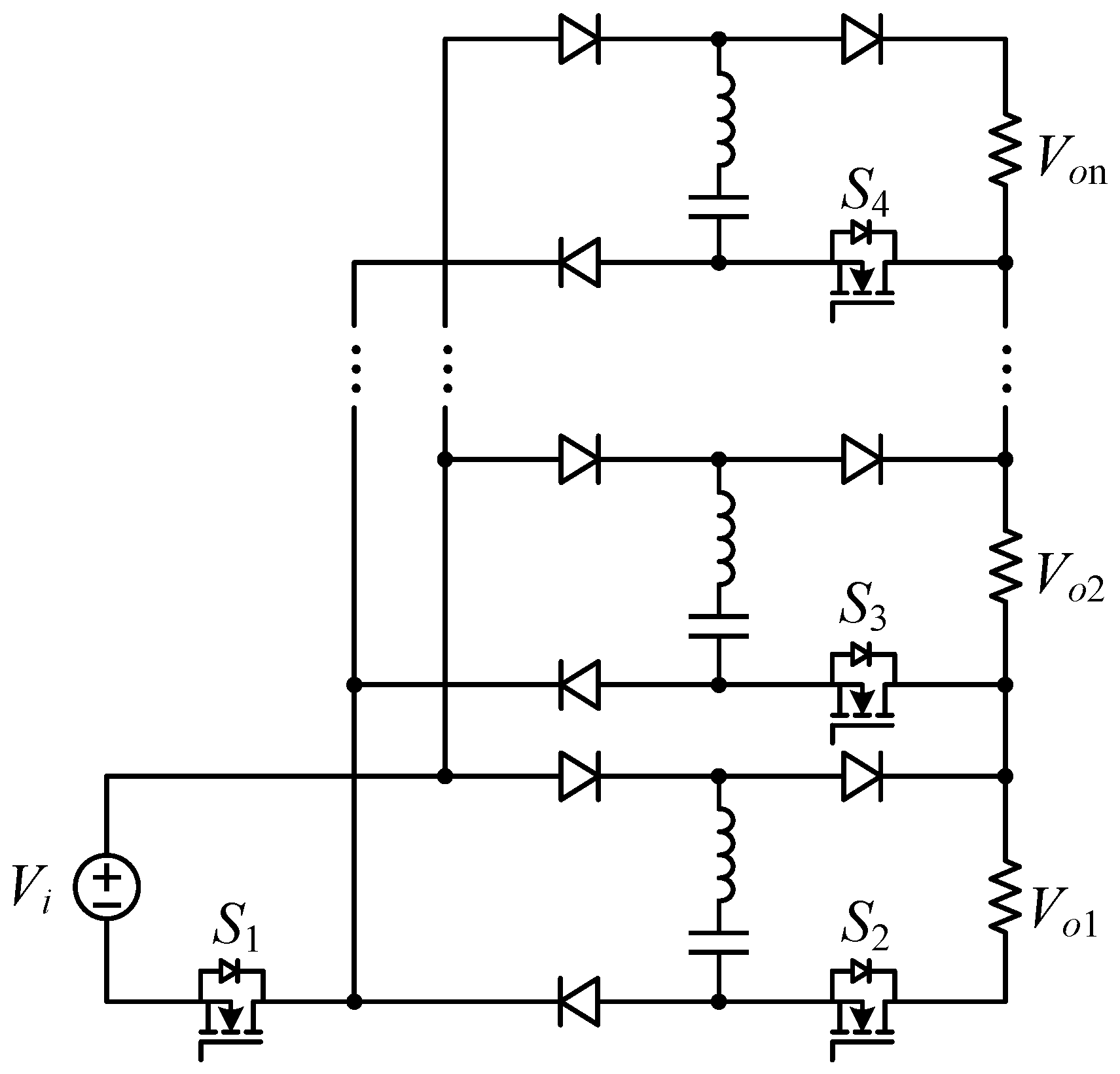

3.1.2. Single-Input Multi-Output

The fundamental concept of the non-isolated “series-expanded” MPC topology is to connect multiple output stages in series on the DC side after the primary power stage, with energy transfer units following a single input source. Each stage is independently regulated, and its outputs are added in series on the DC side to form an expandable high-level bus.

Figure 8 shows a non-isolated “back-end series expansion type” SIMO DC/DC converter topology based on a switched-capacitor-integrated boost architecture [

53]. The input voltage

is uniformly switched by a common main switch

, and the back end consists of several repeated port power units that supply energy to corresponding output ports

. The ground potential of each port equals the cumulative voltages of all preceding lower stages. The voltage at each port is sustained by local energy storage components and regulated individually via timing control. This topology embodies the characteristics of “shared front-end and back-end series expansion”, addressing both multiple outputs and device multiplexing capability.

Current research on the non-isolated “series expansion type” SIMO MPC focuses on the following points. (1) Series cascaded structures based on voltage multipliers/switched capacitors: Recent studies integrate multi-stage voltage multipliers into conventional boost-type converters, forming non-isolated multi-output architectures characterized by multi-stage cascading and multi-port outputs. Such topologies achieve high voltage gain and port scalability while distributing device voltage stress across multiple stages [

54,

55]. However, critical challenges involve balancing the number of multiplier stages against efficiency, ripple, capacitor RMS currents, and energy redistribution losses among stages. (2) Hybrid inductor–capacitor structures with fewer active switches: Mixed “switched capacitor and switched inductor” structures generate multiple series outputs using a reduced number of active devices. Certain designs achieve multi-stage voltage stacking using a single PWM or single-switch driver, thereby reducing drive complexity and cost, while constraining the main switch voltage stress to a single-stage level [

54]. However, Limitations of this approach include diode conduction losses and capacitor stresses arising from charge–discharge processes in voltage multiplier stages, necessitating careful consideration of device selection and thermal management. (3) Symmetrical multi-port topologies for bipolar DC buses: A “single-input/multi-output” configuration has emerged to serve bipolar low-voltage DC buses. Such structures inherently facilitate voltage self-balancing or simplify the balancing between positive and negative poles, thereby reducing the need for additional balancing converters [

56].

The fundamental concept of the non-isolated “parallel-expanded” SIMO multi-port converter involves connecting multiple independent rectification and filtering branches in parallel at the output side after a single input power stage. Each branch takes energy from shared switches and rectification nodes, establishing the required DC voltage on its own branch to form multiple outputs. This structure reuses front-end devices, facilitates port expansion, and decouples each output through its own filtering network, allowing independent voltage levels to be set for each port.

Figure 9 illustrates a boost-based non-isolated “parallel-expanded” SIMO multi-port converter topology [

57]. A single input source

transfers energy through the input inductor

, which is centrally modulated by the main switching network. The output side consists of two parallel branches. The upper branch charges the capacitor

through the diode

to form the first output

. The lower branch extracts energy directly from the switching node and is filtered by

and

to yield the second output

. The two outputs share the front stage but are not connected in series, reflecting the structural feature of “front stage sharing and back-end parallel expansion”.

Existing research mainly focuses on three technical paths. (1) Incorporation of Coupled Inductor and SC/SL Units: To achieve a broader output range, recent studies integrate coupled inductors and switched capacitor/switched inductor units into the SIMO back-end branches, enabling multiple buck–boost outputs simultaneously at relatively low-duty cycles [

58,

59]. However, trade-offs must be carefully managed regarding device stress and circulating currents. (2) Multiphase interleaving and soft-switching/resonant techniques: Recent studies have employed phase interleaving to reduce source side/bus ripple and improve transient performance under multi-phase superposition [

57,

60]. Meanwhile, introducing soft switching paths such as LLC and active clamping to achieve ZVS/ZCS can simultaneously reduce commutation loss and device stress, as well as improve efficiency [

61,

62]. (3) Energy buffering and decoupling strategies: As the number of output ports increases, the conduction time slot allocated to each individual port becomes restricted, exacerbating the trade-offs between transient and steady-state performance. The inherent “duty-cycle and inductor-charging sequence constraint” represents a structural limitation in SIMO converters. Recent studies have addressed this issue by integrating intermediate energy storage stages, energy-holding paths, or equivalent buffering units within the converter topology [

63,

64]. These methods effectively alleviate structural constraints, enhance each port’s energy self-regulation capability, reduce cross-port interference, and significantly improve transient load response performance.

In hydrogen-based DC microgrid applications, non-isolated SIMO MPC architecture has been utilized to couple PV sources, DC buses, and electrolyzers. A non-isolated multi-port buck–boost architecture employs a two-phase interleaved boost mode to feed PV-generated power into the DC bus and utilizes a two-phase interleaved buck mode during the inductor energy release phase to supply power to the PEMEL, achieving coordinated allocation between PV-powered hydrogen production and bus power supply [

65,

66]. Additionally, a phase-interleaved SEPIC–Ćuk combined SIMO topology integrates bipolar bus outputs using a single switch, significantly reducing device count while balancing power distribution between positive and negative buses, which is particularly suited for low-voltage, compact hydrogen microgrid deployments [

56]. A multi-port buck-based SIMO topology tailored for electric vehicles has also been investigated, achieving flexible multi-port power distribution with a single inductor and a minimal number of switches [

67,

68]. These advancements indicate significant advantages and broad engineering application potential for non-isolated SIMO topologies in hydrogen microgrids.

3.1.3. Multi-Input Multi-Output

Non-isolated MIMO DC–DC converters can achieve energy routing and voltage regulation for multiple-source and multiple-load scenarios within single-stage or reduced-stage power conversion structures. By deploying scalable energy transfer units (comprising inductors/capacitors combined with switches/diodes) at both the input and output sides, these converters enable independent or semi-independent regulation for each port while sharing magnetic and filtering components. Fundamentally, the design seeks a balance between port-decoupling capability and device/control complexity. Regardless of whether the input and output ports adopt series or parallel expansion methods, the system essentially forms a modulated energy channel matrix. Therefore, cross-regulation suppression, dynamic response, efficiency, and device stress must be cohesively addressed in design and control. Based on the modular interconnection methods (series or parallel) at the input and output sides, these topologies can be classified into four categories: ISOS, ISOP, IPOP, and IPOS.

Figure 10a shows the energy convergence and current sharing of various DC sources at the front end of IPOS through diodes/switches connected to a common inductor. The back end uses cascaded switch capacitor units/stacked voltage outputs, allowing multiple output terminals to be connected in series in voltage to achieve high boost ratios and multiple voltage levels, while the device voltage stress is shared by cascading. This structure is particularly suitable for scenarios where low-voltage high-current sources are paralleled and converged, and the load side requires high bus voltage or multiple voltage levels [

69]. However, it requires addressing voltage balance and dynamic sharing among cascaded capacitors/modules.

Figure 10b can be equivalently regarded as an ISOS/bipolar DC bus implementation, where multiple power units are series-connected at the input side to withstand high voltage, while their outputs are series-connected between the positive and negative poles to form a ± bipolar DC bus (with the midpoint stabilized by DC link capacitors). This configuration facilitates the use of lower-voltage-rated devices under high-voltage input/output conditions and increases power density [

70]. However, it requires simultaneous management of input voltage balancing and output voltage balancing constraints.

Recent research on multi-input multi-output (MIMO) DC–DC converters primarily focuses on the following themes. (1) Multi-port power/voltage/current balancing and decoupling control: Input voltage sharing (IVS) and output current/voltage sharing (OCS/OVS) within series parallel topologies (such as ISOP, ISOS, and IPOS) involve strong coupling and multiple interdependent links. Existing research has developed generalized control methods and stability designs for IVS and OCS/OVS [

71]. However, when the system scales with increased ports or stages, coupled with device aging-induced parameter drift and asymmetric loading conditions, a unified and verifiable process for ensuring consistency in current/voltage sharing and fault-tolerant operation remains to be established. (2) High voltage gain combined with low device stress: To accommodate high-voltage DC buses or multi-level loads, existing research on non-isolated MIMO topologies has introduced voltage multiplier cells, coupled inductors, and phase-shifted or interleaved structures to achieve high voltage gain under low-duty cycles while effectively reducing device stress and conduction losses [

72]. (3) Cross-port coupling and multi-objective control: Multi-input multi-output topologies inherently lead to energy interactions between sources and sources, sources and loads, as well as among loads, requiring power management to balance system efficiency, dynamic performance, and storage lifetime. Some studies have addressed this issue by adopting model predictive control (MPC) and hierarchical control strategies, achieving notable progress [

73]. However, a scalable control framework remains insufficiently developed.

In the hydrogen DC microgrid, the non-isolated MIMO multi-port topology can connect the DER to the unipolar or ±bus uniformly to reduce cascading transformation and facilitate centralized energy management. For example, a PV–FC four-port DIDO interface designed for a 48 V bipolar bus employs a single inductor and two switches to achieve polarity voltage regulation and MPPT for PV. This configuration significantly reduces the component count and control complexity, with its performance validated through prototype experiments [

72]. Recent engineering-oriented MIMO solutions have further achieved high-gain capability and low component stress through independent port duty-cycle control, improving energy transfer from low-voltage sources to high-voltage buses and enhancing decoupling and controllability of critical ports like FCs and electrolyzers [

74]. Furthermore, a 250 W MIMO prototype has demonstrated practical utility in isolated and remote microgrid applications, effectively mitigating cross-regulation issues and maintaining high efficiency with fewer components [

71]. Additionally, continuous-current topologies such as Ćuk, SEPIC, and their combined multi-output variants have been extensively investigated. These topologies demonstrate effective ripple suppression that slows FC and electrolyzer aging while facilitating flexible bipolar or multi-level DC bus architectures [

75]. Similar non-isolated multi-port structures have been experimentally validated in electric vehicles, highlighting their promising application potential in hydrogen-integrated EV scenarios [

76].

3.2. Isolated Multi-Port Converter Architecture

Isolated multiport converters are built around a transformer that provides galvanic isolation and thereby electrically decouples the ports. Based on current trends in topology evolution, the isolated MPC architecture can be broadly classified into two categories. The first is the topology-derived type, where the transformer retains a fixed number of windings, and multiple DC ports are obtained by flexibly combining or reconfiguring these windings with an external power stage. The primary advantages of this category of converter are the scalability and flexibility of the power stage topology. Research in this field typically focuses on achieving efficient multi-port power conversion, enhancing energy density, and optimizing component sharing. The second category is the multi-winding transformer-derived type, which increases the number of transformer windings to expand the number of ports. Typical examples of this category include the Triple Active Bridge (TAB) and Multi-Active Bridge (MAB) topologies. Research on this type of topology primarily focuses on transformer design, optimization of coupling effects between windings, and improvements in energy transfer efficiency.

3.2.1. Topology-Derived Type

In the isolated “topology-derived” MPC, DC ports are expanded by flexibly reconfiguring the power stage at the transformer port without altering the number of windings in the isolation transformer. Currently, there are two representative approaches in hydrogen-based DC microgrids. The first employs a single two-winding isolation transformer as the sole isolation path, with multiple power stages (such as full-bridge/half-bridge, resonant, or current-source units) interfaced around the same high-frequency link. This approach creates multiple branch ports on both sides of the transformer, thus facilitating port decoupling and high design portability.

Figure 11 illustrates a topology-derived isolated DC–DC converter that implements primary-side parallel aggregation, single-transformer isolation, and a post-stage bipolar DC bus [

77]. Three generic sources are interfaced through input capacitors and inductors to function as independently dispatchable current-type ports, with their currents aggregated at a common node. The combined current excites a primary full bridge

via a DC-blocking/energy transfer branch (

) and a single transformer, providing high-frequency galvanic isolation, voltage scaling, and a wide soft-switching window. In the second approach, a synchronous full bridge

followed by

forms a bipolar DC bus. An active midpoint balancer (switch

with diodes

) equalizes the two rails so that the output voltages

and

remain under load asymmetry.

Another approach adopts a modular structure composed of standardized submodules with high-frequency isolation as basic building blocks. Each submodule comprises a primary-side power stage (full bridge/half bridge, resonant, or DAB), a dual-winding high-frequency transformer (MFT), and a secondary-side rectifier/active bridge with a filter network. Multi-port expansion is achieved by adding or reconfiguring submodules and interconnecting their inputs or outputs through series or parallel arrangements to form multiple DC ports.

Figure 12 illustrates a typical topology for this configuration, employing the ISOS modular structure paradigm, where identical isolated submodules are series-stacked on both the input and the output to increase the voltage rating [

78]. In each submodule, there features a voltage-source full bridge on the primary side, driving the isolation transformer via leakage/resonant inductors

L1 and

L′

1. Phase-shift modulation achieves voltage matching while extending the ZVS operating range of primary-side components. On the secondary side, the full-bridge diodes rectify the high-frequency voltage into pulsating DC. This can be combined with phase-interleaved rectification to further suppress ripple and reduce filter size, thereby allowing linear scaling of the number of ports and the rated voltage with the module count.

Within the family of single-transformer, two-winding high-frequency-link architectures, research has progressed from early three-port/multi-port full-bridge structures to derivative designs that incorporate buck/boost branches, voltage-multiplying or rectification networks, and resonant elements on the primary/secondary sides [

79,

80]. Furthermore, some designs extend the port and broaden the soft-switching operating range without adding windings, thereby reducing the voltage/current stress of the component and backflow power [

81,

82]. Typical approaches include introducing LCL/LLC resonant branches or voltage-doubling rectification within dual-winding structures to suppress voltage/current stresses and broaden the soft-switching range, whilst mitigating port coupling and circulating current issues arising from shared magnetic flux [

83,

84]. However, the inherent challenges remain in cross-port power decoupling, leakage inductance selection, and magnetic–electrical co-design to balance efficiency and power density.

Along with the modular architecture, research converges on a multi-module structure with series/parallel networking. ISOS, ISOP, IPOS, and IPOP arrangements enable scalable voltage and current ratings while distributing device voltage stress [

85,

86]. However, this introduces challenges of input voltage sharing, output current sharing, and dynamic consistency. To address these issues, voltage- and current-balancing circuits and decoupling networks should be integrated at the topology level, alongside optimization of equivalent loop and parasitic parameters [

85]. Overall, the “two-winding transformer with power-stage combination” emphasizes the coordinated design of magnetic flux utilization and device/parameter decoupling among ports, while the “multi-module with series/parallel networking” approach focuses more on cross-module consistency and reliability design.

In hydrogen-based DC microgrids, the two aforementioned categories of “topology-derived isolated converters” each possess distinct application scenarios. The single-transformer, two-winding architecture, characterized by its compact structure and efficient reuse of power devices, is suitable for coupling multiple sources such as PV, FC, and BESS to either unipolar or bipolar DC buses via a centralized high-frequency link. This topology can be integrated with voltage balancers or polarity balancing networks to maintain midpoint voltage and mitigate imbalance in bipolar DC buses. This approach has already found engineering applications in hybrid energy microgrids and electric vehicle systems, serving as a multi-port interface and for power routing, benefiting from its high power density and reduced number of magnetic components [

87,

88]. For applications requiring high bus voltage, long feeder lines, or N + 1 redundancy and online capacity expansion, the modular architecture can meet voltage and insulation requirements through the free combination of output series/parallel and input series/parallel configurations, while facilitating power level standardization and reliability design [

78,

85,

86]. This design concept has also been validated in DC systems incorporating hydrogen storage and electrolyzers, as well as in bipolar DC microgrids, demonstrating its feasibility and scalability [

89,

90].

3.2.2. Multi-Winding Transformer-Derived Type

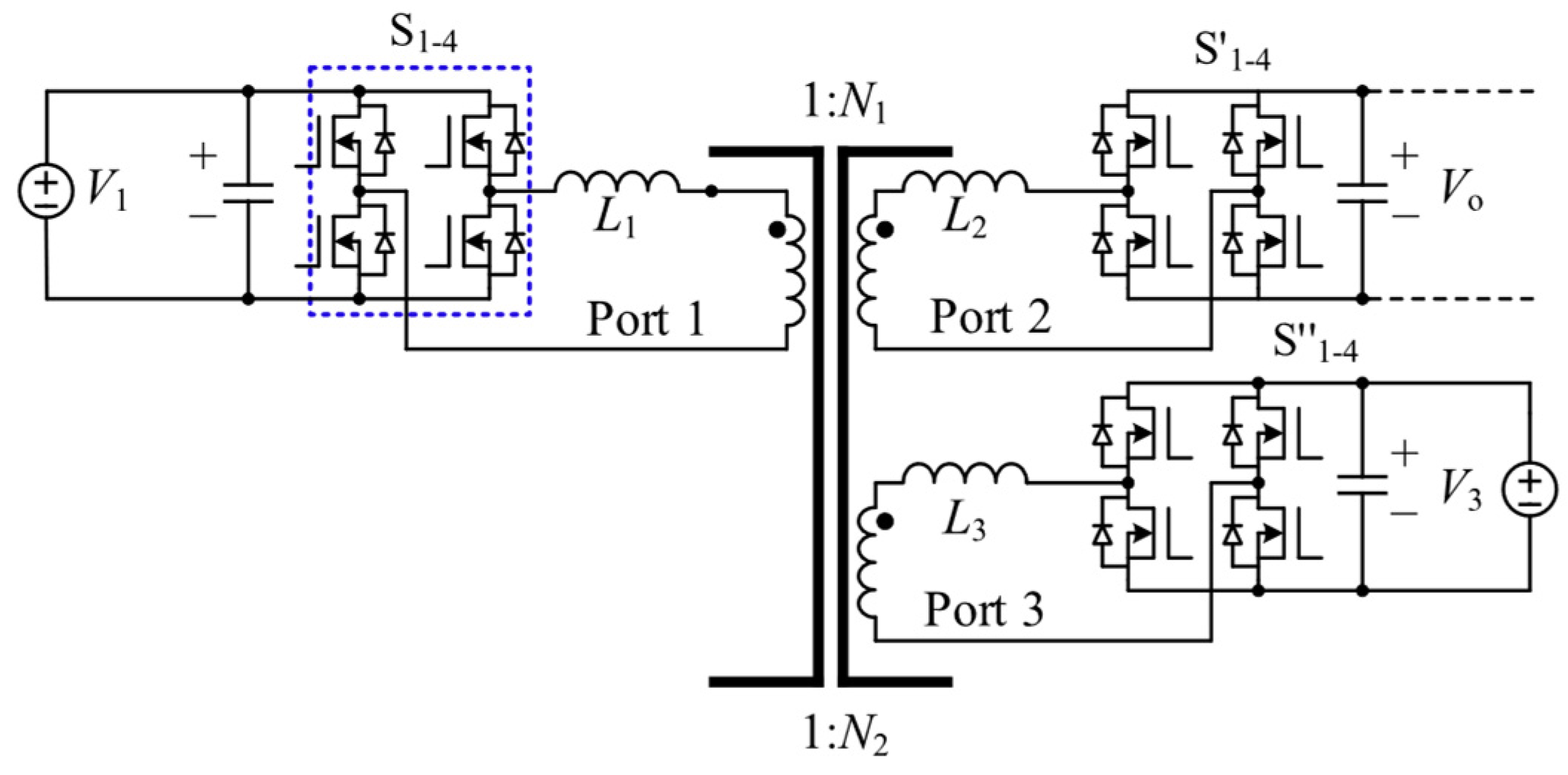

The isolated “Multi-Winding Transformer Derived Type” multi-port converter linearly expands DC ports by increasing the number of windings on the common high-frequency magnetic link. Each port is typically coupled via an active full-bridge circuit to a multi-winding high-frequency transformer. Therefore, power transmission between ports can be achieved through phase-shift control, along with the coupling inductance provided by transformer leakage or an external series inductor. This design inherently supports bidirectional power flow, fixed-frequency operation, and electrical isolation.

Figure 13 illustrates a representative three-port configuration. Port 1 interfaces the primary through a full bridge, while two secondary windings (1:N

1 and 1:N

2) transfer power to Ports 2 and 3 via their respective full bridges and filters. Power sharing among ports is governed by phase-shift control, which allows the energy storage system to operate bidirectionally, enabling charge and discharge [

91].

Current research on isolated multi-winding transformer-derived multi-port converters concentrates on four themes. (1) Power–flow decoupling: the power transfer matrix of the multi-winding transformer-derived type is inherently coupled, so port voltages and phase-shift variables are mutually dependent [

92]. To address this, control frameworks based on continuous time averaged (state-space) models, look-up table decoupling matrices, and model–reference decoupling have been proposed to enhance independent port regulation and dynamic stability [

93]. (2) Multi-winding transformer design: The allocability of inter-winding leakage inductance and coupling coefficients determines soft-switching boundaries and transmissible power. Recent work has proposed collaborative design/calculation methods and equivalent modeling for multi-port leakage inductance, enhancing design prediction accuracy [

94,

95,

96]. (3) Zero-sequence circulating current: Three-winding configurations or those incorporating delta/center-tap structures may generate zero-sequence paths and circulating currents, introducing additional losses and port recoupling. Comprehensive suppression measures are required through winding connections and shielding, equivalent modeling, and control strategies [

96,

97]. (4) High efficiency and wide ZVS range: In transformers with three or more windings, connection arrangements such as star (Y), delta (Δ), or stabilizing windings introduce zero-sequence paths and circulating currents, resulting in undesirable coupling between ports. Current research addresses this issue through careful design of magnetizing inductances, multi-phase modulation strategies, and phase-shift optimization techniques to extend full-port ZVS, thereby reducing RMS currents and conduction losses [

98,

99]. Although notable progress has been made in this direction, a systematic and unified design and validation approach balancing the three-dimensional trade-off among high port-count, high power-density, and manufacturability remains an open research gap.

In hydrogen-based microgrids and hydrogen-coupled systems, the multi-winding transformer-derived (MWTD) architecture has been employed to simultaneously couple multiple ports, including FC, EL, and BESS, within a common high-frequency magnetic link to achieve single-stage energy aggregation and flexible power distribution [

91]. Specifically, this topology utilizes a single multi-winding high-frequency transformer to realize electrical isolation and flexible power exchange among different ports, making it particularly suitable for scenarios requiring frequent bidirectional power flows between electrochemical storage devices and renewable energy units. Furthermore, MWTD topologies also show promising application prospects in renewable energy electric vehicle charging stations and onboard vehicle charging and discharging systems [

100,

101].

4. Comparative Analysis and Considerations

Building upon the classification and detailed analysis of isolated and non-isolated MPC topologies presented above, this section presents a comparative evaluation highlighting their key performance characteristics, structural complexities, and suitability for hydrogen-based DC microgrid applications. Furthermore, considerations are presented regarding the impacts of current ripple and ramp rate on hydrogen-based distributed energy resources, the selection of optimal control strategies, and the impact of emerging semiconductor technologies on MPC topologies. Moreover, existing challenges and targeted recommendations for future research directions are discussed within each of these subsections.

4.1. Comparative Analysis of MPCs

Table 2 summarizes the key parameters of typical multi-port converters (MPCs) within the previously discussed non-isolated and isolated architectures, including output voltage expressions, topological complexity, typical efficiency, estimated power density, and bidirectional power-flow capability. In general, non-isolated topologies feature simpler structures and fewer components than isolated counterparts, which makes them attractive in applications that are sensitive to cost or require high power density. Owing to the absence of isolation windings, non-isolated MPCs usually achieve a relatively higher estimated power density. By contrast, isolated topologies tend to exhibit slightly lower power density because transformers or multi-winding magnetic components increase both volume and structural complexity. Both categories can reach high efficiency, although the exact values depend on device ratings, control strategy, and operating conditions. The lack of galvanic isolation in non-isolated configurations, however, limits system-level safety and scalability. Isolated MPCs, on the other hand, provide electrical isolation and modular expansion through transformers or multi-winding structures, at the expense of higher device count and more intricate control. Moreover, isolated topologies often rely on more complex modulation schemes, such as phase-shift modulation, whereas non-isolated MPCs typically employ simpler PWM-based control. Finally, while bidirectional power-flow capability significantly enhances system flexibility, it also increases control and design complexity; this trade-off should be carefully evaluated in practical engineering applications, motivating future research into hybrid structures that combine the advantages of both isolated and non-isolated MPCs.

According to the topology structure analysis shown in

Table 3, non-isolated multi-port converters (MISO, SIMO, MIMO) generally exhibit characteristics such as low current ripple and high power density. However, as the number of ports increases, their control complexity and component count also rise accordingly. For example, MISO topologies like ISOS-Buck offer the advantages of simple circuitry and low cost, making them more suitable for unidirectional step-down applications such as PEMEL. The SIMO structure (e.g., ISOS-Boost) employs independent rectification outputs for each port, making it suitable for PV, WT, and FC interfaces, but it faces challenges such as cross-regulation between ports and current sharing, alongside increased switching components. MIMO structures (e.g., IPOS-Boost) possess multi-level output capability, suitable for various energy storage devices such as BESS and SC, but with further increased control complexity. In contrast, isolated multi-port converters (TD and MWTD) demonstrate outstanding performance in galvanic isolation, safety, and reliability. These topologies typically employ phase-shift modulation (PSM) to achieve soft-switching and reduce switching losses. For instance, hybrid topologies feature DC bus voltage adaptive balancing capability, suitable for most distributed energy interfaces, albeit accompanied by complex control strategies and high costs. Additionally, TAB structures can achieve bidirectional power flow between arbitrary ports and are suitable for soft-switching operation, particularly appropriate for applications requiring flexible configuration and high safety. However, these structures are constrained by magnetic component dependency and control strategy complexity, increasing the difficulty of design and application.

In summary, non-isolated topologies are more suitable for low-voltage applications or scenarios with cost and space constraints, while isolated topologies are better suited for high-voltage levels, bidirectional power transfer, or complex energy systems with higher safety requirements. However, each category faces specific challenges in practical engineering. The key challenge for non-isolated topologies lies in dynamic cross-regulation issues, where mutual interference between ports affects stable system operation. This challenge can be addressed by introducing optimized control strategies such as dual-loop control, distributed coordinated control, or model predictive control to achieve precise coordination and effective decoupling of power between ports. Isolated topologies primarily face challenges in high-frequency transformer design complexity and soft-switching technology implementation. Although galvanic isolation enhances system safety and reliability, challenges such as precise control of transformer leakage inductance, thermal management of magnetic components, and extending the operational range of soft-switching techniques remain critical and require further investigation. Therefore, future research should focus on the collaborative optimization of magnetic integration design and soft-switching control strategies and further explore novel transformer structures and materials to reduce transformer design difficulty and cost, thereby promoting broader practical applications of isolated multi-port converters.

4.2. Discussion and Consideration

4.2.1. Impact of Current Ripple and Ramp on Electrochemical DER

Current ripple, an inherent dynamic characteristic of power electronic converters, significantly impacts the performance and longevity of PEMFC and PEMEL in hydrogen-based distributed energy systems. During PEMFC operation, ripple superimposed on DC current induces periodic charge accumulation and fluctuations in reactant concentrations at the membrane electrode assembly (MEA) interface. Specifically, low-frequency ripple (approximately 100–300 Hz) disrupts the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) at the cathode catalyst layer, resulting in cyclic increases in interfacial charge transfer impedance and reductions in double-layer capacitance [

102]. These dynamic electrochemical disturbances manifest as pronounced I–V hysteresis in the MEA polarization curves, causing delays in operating voltage response to current changes and consequently introducing additional activation polarization losses. Furthermore, frequent load fluctuations compel the fuel supply system to operate at elevated hydrogen flow rates to meet instantaneous peak current demands, decreasing hydrogen utilization efficiency and indirectly increasing overall fuel consumption. High-frequency ripple (>10 kHz), although too rapid for complete electrochemical reaction responses within the MEA, generates additional internal ohmic losses within the membrane and electrode structure [

103]. These losses elevate local temperatures within the MEA, accelerating thermal aging effects on catalyst layers and membrane materials and thus negatively affecting the long-term performance of fuel cells.

Proton exchange membrane electrolyzers exhibit operational characteristics similar to PEMFCs; however, ripple-induced mechanisms differ distinctly. In PEMEL systems, low-frequency current ripple typically exerts negligible short-term effects on hydrogen production since the hydrogen yield primarily depends on the average current. Conversely, high-frequency current ripple adversely affects long-term PEMEL operation by inducing rapid potential fluctuations at the anode, causing frequent oxidation-reduction cycles on electrode materials. This phenomenon accelerates passivation processes in critical components such as titanium-based electrode meshes, incrementally raising the electrolyzer’s internal high-frequency resistance (HFR). Additionally, increased HFR restricts gas bubble detachment and water mass transport, further diminishing the electrolyzer’s operational stability and durability over extended operation periods [

104].

Specifically, the impact of current ripple on hydrogen-based distributed energy performance has been validated in multiple experimental studies. In an experimental investigation of a prototype 300 W fuel cell UPS system, when continuous 100–120 Hz low-frequency ripple with approximately 24.3% amplitude was present, the MEA electrochemical characteristics underwent periodic disturbances, resulting in significant voltage output lag effects, ultimately leading to reduced system operating efficiency and accelerated fuel cell lifespan degradation [

105]. Another study on high-frequency ripple effects on a 1100 W rated fuel cell stack demonstrated that at a 10 kHz frequency, even a 2% current ripple could reduce stack output voltage by approximately 2 V, with voltage drop further intensifying to over 4 V when ripple amplitude increased to 20% [

103]. This voltage drop forces the fuel cell to increase hydrogen supply to maintain the same power output, increasing fuel consumption. Additionally, durability experiments on long-term PEMEL operation indicate that while high-frequency (10 kHz) ripple does not significantly reduce hydrogen production efficiency in the short term, over 3000 h of testing it increased internal high-frequency resistance to more than twice that of low-frequency and ripple-free conditions, while exacerbating titanium mesh electrode passivation [

106]. This demonstrates the negative impact of high-frequency ripples on PEMEL system long-term operational lifespan.

To address current ripple effects in PEMFC and PEMEL-based distributed energy systems, the specific constraints inherent to hydrogen applications should be carefully considered during converter selection and design. Because of the pronounced ripple sensitivity and relatively slow dynamic response of hydrogen-based electrochemical devices, converters should provide highly continuous input current and effective transient buffering capability. Continuous-current topologies, such as Ćuk and SEPIC converters, inherently possess advantages in this respect, as inductors placed on both the input and output sides naturally smooth the currents, significantly reducing ripple propagation toward hydrogen equipment and thus protecting the electrochemical interface. However, these topologies require separate inductors for each port or additional coupling capacitors (such as in the Ćuk topology), resulting in reduced power density and increased magnetic complexity in high-power scenarios. In comparison, conventional single-inductor topologies, such as boost or buck converters, offer simpler circuits, fewer magnetic components, and higher power density. Nevertheless, these topologies typically produce pulsating currents on one side, necessitating large filtering capacitors to suppress ripple, which increases losses and the risk of parasitic resonances and may affect the long-term reliability and stability of the system. For MPC topology selection in hydrogen-based applications, the trade-off among topology complexity, component count, power density, and ripple performance should therefore be carefully assessed and optimized. It is noteworthy that, at the present stage, requirements on admissible current-ripple levels at PEMFC and PEMEL interfaces are predominantly formulated as device or stack-level operating guidelines and optimization targets reported in the literature, rather than as universally harmonized standards. A technology-wide standard defining admissible ripple thresholds across hydrogen-based electrochemical applications has not yet been established. Therefore, future research could focus on developing unified ripple metrics and interface specifications for hydrogen-based MPC systems. Such standardized criteria would explicitly relate the electrochemical ripple sensitivity inherent to PEM devices to the ripple characteristics associated with different multi-port converter topologies, thereby supporting converter designs that preserve high operational efficiency and enhance the durability of hydrogen-based electrochemical systems.

Additionally, interleaving technology utilizes multiple parallel phases whose ripple components partially cancel each other, effectively reducing the ripple seen by hydrogen-based equipment without significantly increasing the number of magnetic components. Consequently, this enhances the practical applicability of interface converters. Furthermore, the applicability of active power-decoupling circuits and active filtering techniques for handling low-frequency current ripple should be more thoroughly evaluated. These methods, through coordination of circuit topology and control algorithms, can achieve a more stable system input current, thereby reducing dynamic disturbances at the MEA interface. In summary, establishing unified ripple standards for hydrogen-based electrochemical devices and minimizing current ripple through optimized converter topologies and advanced control strategies represent key future research directions in hydrogen-based distributed energy systems.

4.2.2. Effect of Current Ramp on Electrochemical

Elevated current slew rate, as a critical variable in the dynamic operation of electrochemical devices, affects the performance and lifespan of PEMFC and PEMEL in hydrogen-based distributed energy systems. From a fundamental perspective, both types of device contain electrode double-layer capacitance that can provide instantaneous response during current transients; however, the lag in reactant supply and product removal typically induces transient voltage overshoot or undershoot phenomena. Specifically, when current slew rate rises rapidly, the cathode ORR rate in PEMFC increases instantaneously, but the required oxygen supply often cannot meet the demand in time, leading to local oxygen concentration depletion at the cathode catalyst layer, increased charge transfer impedance, and resulting instantaneous voltage undershoot. Meanwhile, temporary hydrogen insufficiency at the anode may trigger side reactions such as carbon support oxidation, accelerating catalyst and membrane degradation [

107]. Similarly, in PEMEL systems, rapid current increase causes the anode oxygen evolution reaction (OER) to intensify rapidly, generating substantial oxygen bubbles that accumulate on the electrode surface, impeding timely water reactant transport and bubble detachment, reducing the effective catalytic area, thus manifesting as voltage overshoot phenomena [

108]. Furthermore, the response characteristics of both types of devices differ during rapid current slew rate decrease. In PEMFC, when current decreases rapidly, the abrupt reduction in water production combined with gas supply inertia may cause temporary drying at the membrane–electrode interface, resulting in reduced membrane conductivity and voltage fluctuations. In PEMEL systems, rapid current decrease leads to swift reduction in anode reaction rate, with corresponding decrease in bubble generation at the electrode surface, causing drastic changes in water content at the membrane–electrode interface, potentially inducing periodic fluctuations in mechanical stress and accelerating material aging.

Current research has experimentally validated the adverse effects of high current slew rates on PEM systems. Dynamic load cycling experiments conducted on a PEMFC prototype single cell with an active area of 25 cm

2 and rated power of 250 W demonstrated that, after 2000 cycles at a high current slew rate of 1.0 A/cm

2/s, cell output performance decreased by approximately 20.67%, roughly twice the performance loss observed with low slew rate cycling at 0.3 A/cm

2/s [

107]. Additionally, in a PEMEL electrolyzer prototype with an active area of 5 cm

2, after 700 cycles at a high current slew rate of approximately 2.9 A/cm

2/s, the internal HFR increased to approximately 1.6 times its initial value [

109]. This confirms the direct negative impact of severe current slew rate fluctuations on the internal electrical performance of PEMEL.

To mitigate the adverse effects of excessive current slew rates, improvements can be implemented through power electronic converter control strategies. First, current slew rate limiting functionality can be incorporated into the converter controller by setting maximum allowable current change rates (di/dt limiting), preventing transient issues in hydrogen-based distributed energy sources through gradual regulation of current change rates. Second, introducing advanced control strategies such as feedforward control and model predictive control to optimize current rise and fall trajectories can avoid abrupt changes, smoothing current transitions and reducing the impact of transient overshoot/undershoot on the system.

4.2.3. Selection of Optimal Control Strategies

Control strategies for multi-port converters also have a direct impact on the performance and equipment lifespan in hydrogen-based DC microgrids. From a control complexity perspective, basic control strategies such as conventional PI and droop control are suitable for remote areas or cost-constrained scenarios due to their simple structure and good economic feasibility. However, these control methods are limited by fixed parameter settings and exhibit limited dynamic response speed and control accuracy under severe load variations or significant nonlinearity, making it difficult to effectively suppress current ripple and current slew rate in PEMEL and PEMFC, potentially leading to reduced equipment lifespan during long-term operation.

To address these shortcomings, several improved control strategies such as dual-loop PI control, hierarchical coordinated control, sliding mode control, and active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) have increasingly been applied to multi-port converters in recent years [

110]. These control strategies can significantly improve DC bus voltage stability and load disturbance adaptability while maintaining moderate costs by enhancing local control and system anti-disturbance capability. For instance, sliding mode control, with its robustness to parameter uncertainties and fast dynamic response, can effectively reduce DC bus voltage fluctuations and current ripple caused by inter-port power interactions, alleviating transient impacts on PEMEL and PEMFC ports. These control strategies have a moderate cost and control complexity, and are suitable for small industrial parks or hydrogen systems requiring frequent switching of operating modes.

In scenarios demanding extremely high control accuracy and dynamic performance, advanced intelligent control strategies such as MPC, neural networks, and meta-heuristic optimization algorithms have been extensively studied and applied. These strategies can effectively reduce the current ripple and current slew rate in PEMEL and PEMFC through real-time optimization of control variables and system prediction models, thereby avoiding the MEA degradation and electrolyzer efficiency decline caused by severe current variations. For example, recent research has demonstrated that combining MPC control with multi-phase interleaved topology can maintain PEM electrolyzer current ripple below 0.5%, significantly improving hydrogen system operational stability and equipment lifespan [

111]. However, these control techniques involve high computational complexity and hardware costs, making them more suitable for high-precision applications such as large-scale hydrogen production facilities or grid-side DC microgrids.

Currently, reducing the computational complexity and implementation costs of advanced control strategies to promote their application in cost-constrained regions for hydrogen microgrids remains an important research topic. Additionally, to further ensure the lifespan of hydrogen-based distributed energy equipment, future control strategy design should incorporate equipment aging status and prognostics and health management (PHM) techniques into control strategies, achieving synergistic optimization of control performance and equipment durability.

4.2.4. Impact of Emerging Semiconductor Technologies on MPC Topologies

Emerging semiconductor technologies such as silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) devices offer significant advantages over traditional silicon devices, owing to their wide bandgap, low conduction losses, and fast switching characteristics. Furthermore, in terms of switching frequency and power density, wide bandgap semiconductor devices support higher switching frequencies, enabling MPC to substantially reduce the size of passive components such as filter inductors and transformers, thereby increasing power density.

The application of these novel devices has positively impacted multi-port converter performance. A study on a hybrid multimodule DC–DC converter demonstrated that using GaN transistors could achieve a peak efficiency of 99.25% at a high switching frequency of 100 kHz in simulation. In another research case, a three-port boost–buck converter employing SiC MOSFETs achieved 94.3% efficiency [

112]. These experiments demonstrate the application prospects of novel semiconductor devices in hydrogen-based DC microgrids. However, the high manufacturing costs and process complexity of these novel devices remain key factors constraining their large-scale deployment. Therefore, future research should focus on exploring the design of multi-port DC converters that leverage advanced semiconductor devices to achieve high efficiency and high power density, balancing technical performance with economic feasibility to promote the practical application of hydrogen microgrids.