Abstract

This research investigates how blending ethanol with gasoline influences both gaseous and particulate emissions, as well as the toxicological characteristics of particulates emitted from a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle adapted to run on fuel mixtures containing up to 85% ethanol by volume. Testing was conducted on E10, E30, and E83 fuels, while the vehicle was exercised on a chassis dynamometer over three repetitions of the Federal Test Procedure and US06 cycles. Results showed important reductions in nitrogen oxide emissions for E30 and E83 for both cycles, along with reductions in particulate matter mass, black carbon, and solid particle number. Total hydrocarbon emissions demonstrated increases with E30 and E83 and tracked well with increases in benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene isomers. Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde emissions trended in sympathy with higher-ethanol blending. The use of E30 and E83 blends produced more reactive emissions, which subsequently adversely affected the ozone-forming potential for these fuels compared to E10. The toxicological properties exhibited mixed results, with the higher-ethanol blends showing reduced oxidative stress compared to E10, while E83 induced a higher cytotoxic response relative to E30 and E10 fuels.

1. Introduction

The transportation sector in the United States (US) remains the dominant source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, particulate matter (PM), and precursor pollutants to ground-level ozone. Although ozone is not emitted directly during combustion, its formation in the atmosphere is influenced by the presence of nitrogen oxide (NOx) and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions [1]. Both primary and secondary transportation pollutants have been linked to serious health conditions, including cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, lung cancer, and increased mortality [2,3]. Over the years, the monoculture of fossil fuel and traditional internal combustion engine transportation has been shifted to renewable, low-carbon fuels and electrifying powertrains as more sustainable mitigation solutions to decarbonize the transport sector and improve air quality [4]. Decarbonizing light-duty vehicles is especially critical, as it provides an opportunity to achieve lower emissions and carbon intensity while maintaining or extending vehicle range.

Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) have garnered attention as they combine a battery that can be charged from the grid and an internal combustion engine. Many studies have investigated PHEV technologies as a means for lowering tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and other harmful pollutants [5,6,7]. Ehrenberger et al. [5] and Karjalainen et al. [8], in their experiments with PHEVs, found elevated NOx and particle number emissions during accelerations and stop-and-go events. Karjalainen et al. [8] also reported that PHEVs generally produce fewer particles, lower PM mass, and reduced black carbon emissions compared to conventional gasoline-powered vehicles. Other studies have explored the utilization of biomass-derived fuels (i.e., ethanol) that can further amplify the environmental benefits of PHEVs [9,10]. Tan et al. [11] tested neat gasoline and ethanol blends on a PHEV and reported reductions in particle number emissions but higher NOx emissions with increasing ethanol content.

Ethanol is widely used across the US as a transportation fuel in the form of E10 (10% ethanol blend). Studies consistently show that incorporating ethanol into gasoline tends to lower emissions of total hydrocarbon (THC), carbon monoxide (CO), and gaseous air toxic pollutants, while NOx emissions are either reduced or marginally affected [12,13,14,15]. Other studies have also highlighted the benefits of higher-ethanol fueling in reducing secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation [16,17]. Ethanol alters the composition of the gasoline blend by changing the volatility characteristics and the heat of vaporization of the fuel, which, in turn, can influence PM emissions. Most of the published literature agrees that intermediate and high-ethanol blends decisively lead to PM reductions [18,19,20]. However, the impact of lower blends like E10 and E15 remains inconsistent, with some research reporting reductions in PM emissions and others observing increases [12,21,22].

Ethanol fueling has been shown to reduce toxic volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes (BTEX), and 1,3-butadiene [12,15,18,23,24]. Studies have shown that even low ethanol blends can mitigate VOC emissions, decrease the ozone-forming potential (OFP), and reduce the roadside ambient VOC concentrations in urban areas [12,25,26]. This is not the case for acetaldehyde, where studies have overwhelmingly shown that acetaldehyde increases with more ethanol [12,15,18,27]. The mechanisms by which emissions from ethanol-fueled engines impact human health are complicated and not extensively studied. While some studies have focused on the health effects of port-fuel injection (PFI) and gasoline direct injection (GDI) exhausts [28,29,30,31], there has been comparatively less research on how ethanol fuels influence the health effects of exhaust emissions [32,33,34]. For example, both studies by Roth et al. [33] and Bisig et al. [34] have suggested that ethanol fuels can result in reduced cellular toxicity compared to gasoline emissions. Yang et al. [19] tested a Tier 3 E10, an E30, and an E78 blend on a GDI flexible fuel vehicle (FFV) and found that the E78 blend exhibited the least oxidative potential compared to E10, as expressed by the macrophage ROS (reactive oxygen species) and DTT (dithiothreitol) assays. They also found that the E78 blend induced the highest levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNFα) production. Sabbir Ahmed et al. [35] reported that higher-ethanol concentrations were linked to downregulation of IL-6 and more substantial CCL5/NOS2 downregulation. Rossner et al. [36] found that gasoline emissions had significantly higher inflammation-related toxicity than E20, suggesting that ethanol blends could pose a reduced risk to respiratory health.

This study assessed how high-ethanol blends influence emissions from a PHEV that was equipped with an adapted E85 conversion kit. The vehicle underwent triplicate testing using both the Federal Test Procedure (FTP) and US06 cycles. Emissions analyses included measurements of criteria pollutants, mobile air toxics, PM mass, particle number concentrations, and particle size distributions. The oxidative stress, cytotoxicity, and selected inflammatory markers of PM emissions were also evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Fuels and Vehicle

This work employed three different fuels, including a summer-grade E10, an E30, and an E83 blend. The E10 fuel, sourced from four California refineries, as detailed by Tang et al. [12], served as the base for preparing the higher-ethanol blends. E30 and E83 were created by splash-blending denatured ASTM D4806 fuel-grade ethanol with the E10 fuel. Key fuel parameters are listed in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials. The test vehicle was a 2022 model year PHEV equipped with a naturally aspirated sequential multi-port fuel injection (SFI) gasoline engine and a three-way catalyst (TWC), which was fitted with an approved E85 conversion kit. The vehicle was certified to meet California SULEV30 exhaust emissions standards for light-duty vehicles and had an odometer reading of 3060 miles at the start of the campaign. All tests were conducted with the vehicle under the charge sustain mode with a 75% state of charge (SOC).

2.2. Emissions Testing and Measurement Protocol

The vehicle was tested using both the FTP and US06 drive cycles on a chassis dynamometer. The FTP cycle, which serves as the certification standard for light-duty vehicles in the US, consists of three phases (or bags): a cold-start transient phase, a hot-running phase, and a hot-start transient phase. The US06 cycle was introduced to address limitations of the FTP test, particularly its inability to represent aggressive driving, as well as high-speed and high-acceleration conditions. The speed–time profile traces for the FTP and US06 cycles are shown in Figure S1 and Figure S2, respectively, in the Supplementary Materials. For each fuel, the US06 cycles were performed immediately after the corresponding FTP test. A US06 preconditioning cycle was performed before the measurement US06 test.

All emissions testing was carried out at the Light-Duty Vehicle Laboratory (LDL) at CE-CERT. A detailed description of the facility can be found in Tang et al. [12]. In summary, the laboratory is equipped with an AVL CVS i60 generation AMA SL (Slim Line) system, integrated with AVL’s iGEM automation software and a dilution tunnel. Bag emissions of THC, CO, NOx, non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHC), methane (CH4), and CO2 were obtained with the AVL CVS SL system.

Gravimetric measurement of PM mass was conducted in accordance with the procedures specified in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 40, Part 1066, along with applicable references in CFR, Title 40, Part 1065. PM filter samples were collected for each phase of the FTP cycle, as well as across the complete FTP cycle. Additional PM mass sampling was also performed over the full duration of the US06. Black carbon emissions were monitored using an AVL Micro-Soot Sensor (MSS). Solid particle number (SPN) emissions were measured following the European Particle Measurement Programme (PMP) using an AVL Particle Counter (APC plus) with a 23 nm cut-off particle diameter. A TSI condensation particle counter (CPC 3022A) with a 7 nm cut-off diameter was used downstream of the APC to measure SPN smaller than 23 nm. Particle size distributions were obtained with a TSI 3090 Engine Exhaust Particle Sizer (EEPS) spectrometer.

Monoaromatic and other hydrocarbon compounds were sampled from the CVS tunnel using 6 L SUMMA passivated stainless steel canisters. Speciated hydrocarbon analysis was conducted using a Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry/Flame Ionization Detector (GC/MS/FID) analytical system, in accordance with EPA TO-12/PAMS and EPA TO-15A methods. Carbonyl compounds were collected using silica cartridges coated with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA), operated at a flow rate of 1 L/min, regulated by a mass flow controller. After sampling, the DNPH cartridges were eluted with 2 mL of acetonitrile and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Waters 2690 Alliance System equipped with a 996 Photodiode Array Detector, following the US EPA TO-11A method. Both hydrocarbon species and carbonyl compounds were collected only over the full FTP cycle.

2.3. Toxicology Analysis

For the DTT assay, the PM filters were extracted with 20 mL of MeOH and sonicated for 50 min. The assay protocol was adapted from previous studies [35,37]. For the cell exposure experiments, the MeOH in the PM extracts was evaporated with a gentle N2 gas stream, and the samples were reconstituted in LHC-9 cell culture media to reach a concentration of 50 ng/mL for subsequent cell exposures using human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B). Selected biomarkers, including NADPH dehydrogenase [quinone] 1 (NQO1), Cytochrome P450 Family 1 Subfamily A Member 1 (CYP1A1), and hemeoxygenase 1 (HMOX-1), were quantified for all PM samples. Detailed experimental protocols for the DTT assay, cell exposures, and biomarker analyses are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Criteria Emissions (NOx, THC, NMHC, and CO)

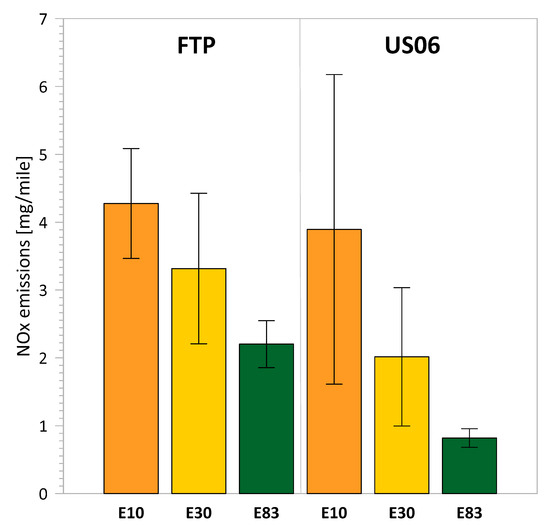

Figure 1 presents the results for NOx emissions over the FTP and US06 cycles. In both cycles, E30 and E83 fuels demonstrated reductions in NOx emissions compared to E10. Using E83 fuel led to a statistically significant reduction of 48% for the FTP cycle and a marginally statistically significant reduction of 79% for the US06 cycle. NOx emissions were also found in very low concentrations for all three fuels and substantially lower than those reported in earlier studies with ethanol blends and older technology FFVs [13,18,38,39], but similar to other studies of FFVs with high-ethanol blends or even to studies with conventional Tier 3 gasoline vehicles [12,19,23]. Previous studies of gasoline vehicles operated on low-level ethanol blends showed statistically insignificant differences in NOx emissions [12,15,23]. Our findings agree with studies that reported NOx reductions with intermediate and high-ethanol blends [13,18,20,24,27,39]. Ethanol has a significantly higher heat of vaporization compared to gasoline, which results in a cooling effect in the combustion chamber, leading to lower in-cylinder peak temperatures for the higher-ethanol blends, thereby suppressing NOx formation.

Figure 1.

NOx emissions for the different fuels over the FTP and US06 driving cycles.

All gasoline vehicles from model year 2025 onward are certified to a combined NOx and non-methane organic gas (NMOG) standard of less than 0.030 g/mile over the FTP cycle. NMOG emissions represent the total mass of oxygenated and non-oxygenated hydrocarbon species, including NMHC, ethanol, formaldehyde, and acetaldehyde. Here, NMOG emissions were calculated using the following EPA formula: NMOGmass = NMHCmass + EtOHmass + Formldehydemass + Acetaldehydemass. The cumulative NMOG + NOx emissions for E10, E30, and E83 were 0.025 g/mile, 0.024 g/mile, and 0.058 g/mile, respectively. Although E83 showed a substantial reduction in NOx emissions, its total NMOG + NOx emissions were nearly double the SULEV 30 standard because of significantly higher ethanol and aldehyde emissions, as will be discussed later in more detail. It should also be noted that weighted NMOG + NOx values are expected to be lower than the cumulative values reported here.

Table 1 presents the emissions data for THC, NMHC, and CO emissions across both the weighted and individual phases of the FTP cycle, as well as the US06 cycle. For the FTP cycle, THC, NMHC, and CO emissions generally increased with higher ethanol content in the fuel. Compared to E10, the weighted THC and NMHC emissions rose by 66% and 53% for E30 (marginally statistically significant) and by 381% and 250% for E83 (statistically significant), respectively. In contrast, THC and NMHC emissions during the US06 cycle were considerably lower, and the influence of fuel ethanol content was less pronounced. Numerous prior studies involving chassis dynamometer testing of gasoline vehicles and ethanol blends have reported decreases in THC and NMHC emissions. Reductions in THC and NMHC emissions are ascribed to the excess oxygen in ethanol fuel, which results in better hydrocarbon oxidation [12,13,14,15,39]. However, other research has observed increases in THC and NMHC emissions when vehicles operate on high-ethanol blends, which is consistent with the trends seen in the present study [23,24,27,40]. Jin et al. [23] claimed that the rise in THC emissions with E85 was due to the excessive production of ethylene via ethanol dehydration during the combustion process. Myung et al. [24] suggested that the lower energy density of higher-ethanol blends resulted in more fuel injected into the cylinder, favoring THC formation. Based on the NOx emissions findings, it is suggested that the elevated heat of vaporization associated with E30 and E83 fuels caused lower combustion temperatures, leading to the rise in THC emissions.

Table 1.

Emissions of THC, NMHC, and CO, expressed in g/mile, for E10, E30, and E83 fuels over the FTP and US06 cycles.

CO emissions showed increases with ethanol blending over the FTP, although not at statistically significant levels. CO emissions also remained well below the 1 g/mile Tier 3 SULEV 30 standard. In the US06 cycle, CO emissions were generally higher than those observed in the weighted FTP cycle. Notably, the E83 fuel resulted in a clear reduction in CO emissions compared to both E10 and E30. The splash blending of ethanol to the E10 fuel raised the anti-knock index (AKI), which is the average value of the research octane number and the motor octane number, which may have affected the vehicle’s control strategy (i.e., by advancing the ignition timing) while operating over the high-speed and load US06 cycle.

3.2. Carbonyl Compounds, Ethanol, Monoaromatic VOCs, and Ozone-Forming Potential

Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, both low-molecular-weight aldehydes, were the dominant compounds detected in the tailpipe emissions for all fuels, as shown in Table 2. Several earlier studies have documented similar findings, with heavier carbonyls largely undetected in modern vehicles [12,15,18,23,38,40]. Both aldehydes showed strong, statistically significant increases with E30 and E83 fuels compared to E10. It should be noted, however, that formaldehyde emissions were measured below the 0.01 g/mile SULEV 30 standard. The rise in formaldehyde and acetaldehyde emissions with increasing ethanol content is well-documented and is primarily attributed to the OH functional group present in the ethanol molecule [41,42,43]. The abstraction of a H atom from ethanol generates hydroxyl (CH3CHOH) and ethoxy (CH3CH2O) radicals, which, in turn, favor the generation of acetaldehyde [42]. Formaldehyde is formed from the β-scission of hydroxyl radicals and also by H-abstraction of methane. Methane, formed from unburned ethanol, is first oxidized to methanol and subsequently to formaldehyde [43]. Tailpipe ethanol emissions tracked well the ethanol content in the fuel and showed strong, statistically significant increases compared to E10. Compared to E10, ethanol emissions were five times higher with E30 and increased by an order of magnitude with E83.

Table 2.

Aldehyde (formaldehyde and acetaldehyde), BTEX, 1,3-butadiene, and tailpipe ethanol emissions, expressed in mg/mile, for E10, E30, and E83 fuels over the FTP cycle.

In general, BTEX emissions mirrored the trend observed for THC emissions, with higher-ethanol blends resulting in increased BTEX levels, as shown in Table 2. This finding contradicts numerous studies on ethanol blends that reported reductions in BTEX emissions with ethanol blends, primarily due to the fuel’s higher oxygen content and lower aromatic content [12,18,19,23,24]. The high-ethanol blends in this study were splash-blended by adding ethanol to E10, leading to the dilution of the aromatic components in gasoline, particularly the heavier aromatic hydrocarbons with lower volatility and higher double bond equivalent (DBE) values. The ethanol cooling effect likely resulted in the suppression or the delay of the evaporation of some of the lighter aromatic hydrocarbons, alkanes, and cycloalkanes, which are more prevalent in gasoline composition, leading to the partial burning of these species in the colder regions of the combustion cylinder (i.e., near the cylinder wall and the exhaust valve). Zhang et al. [44] suggested that ethanol’s evaporative cooling effect delayed the light-off temperature of the TWC, causing reduced conversion efficiencies of hydrocarbon species, such as BTEX. Other studies claimed that ethanol decomposes to methyl radicals, which enhance the formation of benzene and other monoaromatics [15,45]. Emissions of 1,3-butadiene displayed mixed trends, with higher 1,3-butadiene emissions for E30 and lower for E83 compared to E10. Although 1,3-butadiene is not a native component of gasoline, it can be produced during the incomplete combustion of olefinic hydrocarbons [12,15].

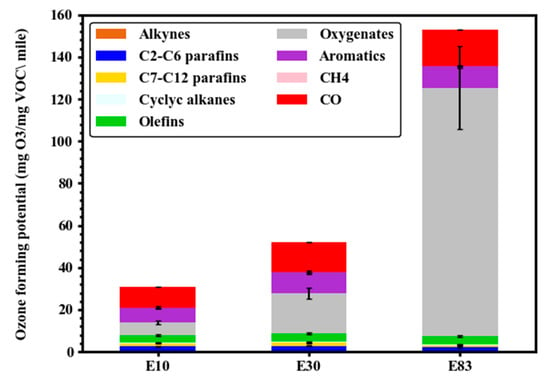

To evaluate the impact of the test fuel blends on air quality, the ozone-forming potential (OFP) was calculated using the Maximum Incremental Reactivity (MIR) scale [46]. Figure 2 shows the calculated total OFP values in units of mg O3/mg VOC/mile, along with the individual contributions of various pollutant groups for each fuel. Apart from CO, oxygenated and aromatic compounds dominated the OFP, followed by olefins, alkanes, cycloalkanes, and alkynes. In general, unsaturated VOCs with double or triple bonds exhibit the highest reactivity. Higher-ethanol blending produced more reactive emissions and subsequently higher tailpipe OFP. The large contribution of the oxygenated VOCs to OFP (constituted 37% and 77% of the total OFP for E30 and E83, respectively) was due to the increased emissions of ethanol, formaldehyde, and acetaldehyde with ethanol blending. Although ethanol has a relatively moderate MIR value of 1.5, lower than those of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, its substantial concentration in tailpipe emissions made it a major contributor to overall OFP.

Figure 2.

Ozone-forming potential (OFP) for E10, E30, and E83 blends over the FTP cycle.

The contribution of monoaromatics was largely due to the BTEX species and other monoaromatic hydrocarbons, such as ethyltoluene isomers, 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene, and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene. Previous studies have also documented increases in OFP associated with increased ethanol content in the fuel [27,47]. In contrast to findings of lower OFP for low concentration ethanol blends [12,15], intermediate and high-ethanol blends can significantly produce highly reactive VOCs, which can generate free radicals that can further react in the atmosphere with NO, converting it to NO2. Upon exposure to sunlight, NO2 undergoes photolysis, a key process driving tropospheric ozone formation.

3.3. Particulate Emissions

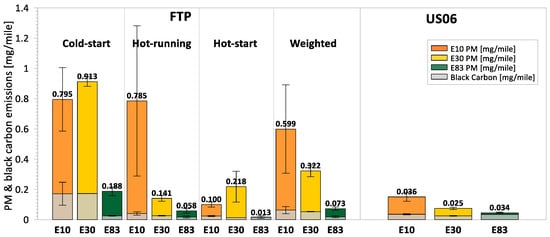

Figure 3 illustrates the PM mass and black carbon emissions measured during the cold-start, hot-running, hot-start, weighted FTP, and the US06 cycles for all test fuels. Across both driving cycles, PM emissions remained below 1 mg/mile, staying well under the PM mass standard applicable to all 2028 model year vehicles sold in California. The highest levels of PM and black carbon emissions were observed during the cold-start phase of the FTP cycle. This increase is primarily due to the fuel-rich mixture that occurs when the engine is cold, and fuel vaporization is limited, leading to incomplete combustion. Emissions of PM and black carbon declined during the hot-running and hot-start phases when the engine was warm, and fuel vaporization was improved.

Figure 3.

Gravimetric PM mass and black carbon emissions for the cold-start, hot-running, hot-start, and weighted FTP, and US06 cycle.

The higher-ethanol blends led to notable PM mass and black carbon emissions reductions across the FTP and US06 driving cycles. E83 showed statistically significant decreases in PM mass of 76% and 70%, respectively, over the FTP and US06 cycles compared to E10. E30 also showed reductions in PM emissions, with a 9% decrease over the FTP and a marginally significant 51% reduction over the US06 cycle. Black carbon emissions trended similarly with PM mass and exhibited strong reductions for E30 and E83 fuels over both cycles. The lower PM and black carbon emissions for E30 and E83 can be attributed to the higher oxygen content of these fuels, which enhanced soot oxidation by promoting the formation of OH radicals. In addition, the dilution of heavier aromatic hydrocarbons with higher boiling points and DBE values, which have a greater propensity to form soot, was another contributing factor for the lower PM and black carbon emissions. Similar results of lower PM and black carbon emissions have been reported in previous studies of low, intermediate, and higher-ethanol blends [12,18,19,20].

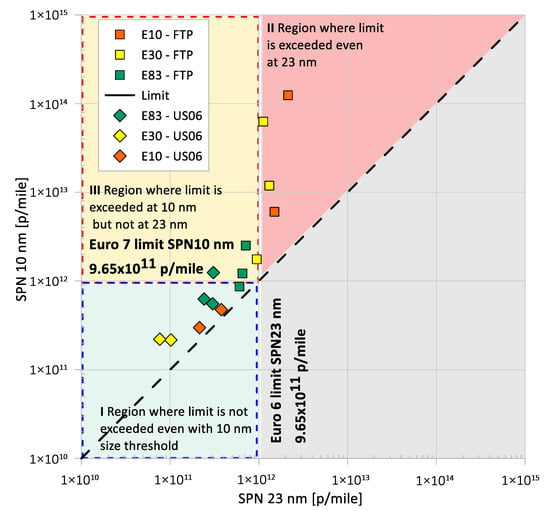

Figure 4 shows the solid particle number above 23 nm (SPN23) and above 10 nm (SPN10) in diameter. Solid particle number emissions are not a regulatory metric in the US, but are regulated in the European Union. It should be noted that the test vehicle was manufactured for and sold in the US market. As such, it was not subject to any emission standards beyond those adopted in the US. However, this section discusses the effect of fuel impact and vehicle technology on solid particle number emissions, as well as any potential restrictions in meeting the Euro 6 and Euro 7 solid particle number standards. Results showed that the driving cycle influence is stronger than the fuel effect. The hot-start US06 pushes almost all ethanol blends into the ‘safe’ zone of Region I, while the cold-start FTP exposes the E10 and E30 blends in Region II, where the E83 blends mostly fall in Region III. Based on this analysis, the Euro 7 standard would likely penalize the use of E83 fuel for exceeding the SPN10 emissions limit, at least for the cold-start FTP. It should be noted that engine technology (charge sustained vs. charge depleting mode) and operating conditions (cold-start FTP vs. hot-start US06) had a profound effect on SPN emissions. This observation is supported by the findings shown in Figure S3 (Supplementary Materials), where the FTP cycle produces about one order of magnitude higher SPN concentration levels than the US06.

Figure 4.

SPN10 versus SPN23 emissions over the FTP and US06 test cycles for E10, E30, and E83 blends; Euro 6 SPN23 and Euro 7 SPN10 emission limits are shown to better illustrate potential differences between fuels and test cycles.

Emissions of SPN10 and SPN23 were reduced with higher-ethanol blends, a finding consistent with previous investigations [12,15,23,24]. During the FTP cycle, SPN23 emissions were reduced by 38% with E30 and by 64% with E83, while SPN10 emissions decreased by 61% and 98%, respectively, for E30 and E83 compared to E10. Particle number concentrations were lower during the US06 cycle compared to the FTP cycle, because the US06 cycle does not include a cold-start phase. For the US06, the use of E30 resulted in SPN23 and SPN10 emissions reductions, but a notable increase in SPN10 emissions for E83. Overall, SPN10 emissions were observed at significantly higher levels than SPN23 emissions, suggesting that ethanol blending promotes the formation of smaller-diameter solid particles. The presence of oxygen in the fuel molecule and the dilution of aromatics for the higher-ethanol blends can generate fewer soot particles. This will cause the volatile (unburnt) hydrocarbons to nucleate into smaller-diameter particles, leading to the higher concentration of sub-23 nm particles, as indicated by Catapano et al. [48]. Recent studies have also shown higher SPN10 emissions compared to SPN23, which are dependent on vehicle technology and test cycle [49].

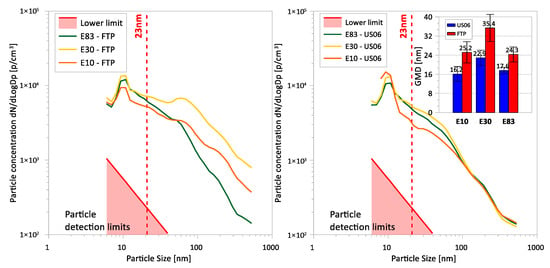

The average particle size distributions for the FTP and US06 cycles are presented in Figure 5. The FTP cycle exhibited a weak bimodal distribution for E10 and E83, and a more distinct bimodal distribution for E30. There was a clear peak of accumulation (soot) mode particles for E30, centered at about 60 nm. While the overall particle size distribution profile for all three fuels did not corroborate the PM mass, E30 showed some increases in PM mass relative to the other fuels over the cold-start and hot-start phases of the FTP, which may explain the elevated concentrations of soot particles. Nucleation-mode particles peaked at 10 nm, with E30 and E83 fuels producing higher populations of nucleation-mode particles. These particles were likely volatile and semi-volatile in nature, originating from the incomplete combustion of fuel and lubricant oil fragments during the cold-start phase of the FTP when the engine was cold, and the TWC was below its light-off temperature.

Figure 5.

Average particle size distributions for E10, E30, and E83 blends for the FTP cycle (left panel) and the US06 cycle (right panel). A snippet graph showing the geometric mean diameter for each fuel/cycle combination is illustrated on the right panel.

For the US06 cycle, the nucleation mode for all test fuels was dominant (centered at 10 nm), exhibiting a unimodal distribution. The dominance of nucleation-mode particles for the more aggressive and higher load US06 was likely due to incomplete combustion from over-fueling and from escaping (unburnt) lubricant oil during the sharp acceleration events. It is theorized that the origin of these particles was from partially combusted fuel and from volatile and semi-volatile organic hydrocarbon species. E30 and E83 fuels resulted in lower concentrations of nucleation-mode particles than E10, which could be due to the higher oxygen content, lower aromatics, and less carbon available to form carbonaceous particles. The US06 yielded lower geometric mean diameters (GMD) for all fuels compared to the FTP, with the difference in GMD between the fuels being roughly the same for both cycles.

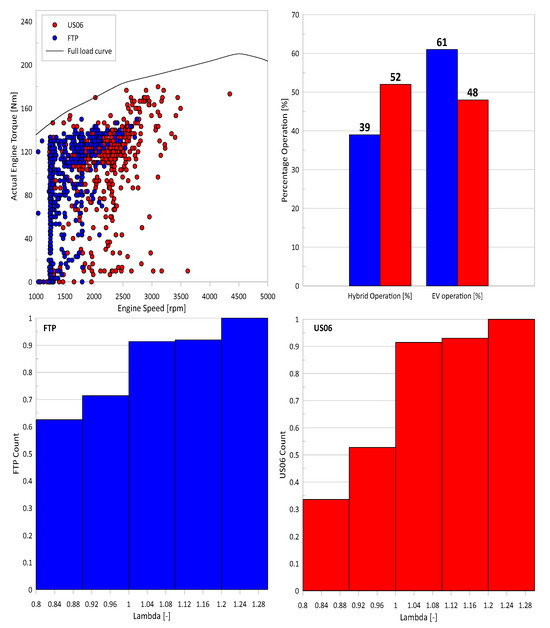

3.4. Effect of Hybridization on Engine Operation

All tests were conducted with the vehicle’s charge-sustaining mode, where the internal combustion engines engaged more frequently and under higher loads to maintain the battery’s 75% SOC target. The influence of the electric motor on engine operation is shown in Figure 6. At first glance, the FTP test cycle produces fewer engine load events than the US06. The percentage operation in hybrid mode over the FTP was 39% compared to 52% over the US06. This observation suggests the PHEV was likely calibrated to operate more frequently on the electric motor over the FTP rather than the US06. However, fewer hybrid engine-on events for the FTP cycle were associated with more frequent fuel enrichments (mainly occurred during the cold-start phase), as indicated by the cumulative lambda distribution plots. The combination of cold-start and more frequent fuel enrichments can potentially negatively affect tailpipe emissions and engine performance, as discussed earlier. In particular, the SPN emissions were primarily attributed to cold- and semi-cold-start events, where enhanced fuel enrichments at cold conditions could lead to improper fuel atomization and poor combustion. NOx emissions can also be affected under these conditions as a result of the delayed TWC light-off due to lower exhaust flow at lower TWC temperatures [11].

Figure 6.

The top panel shows, on the left, the engine operating points for the FTP (blue) and US06 (red), and on the right, the percentage of hybrid and pure electric motor operation of the vehicle on the FTP (blue) and US06 (red). The bottom panel shows the cumulative lambda for the FTP (left) and US06 (right).

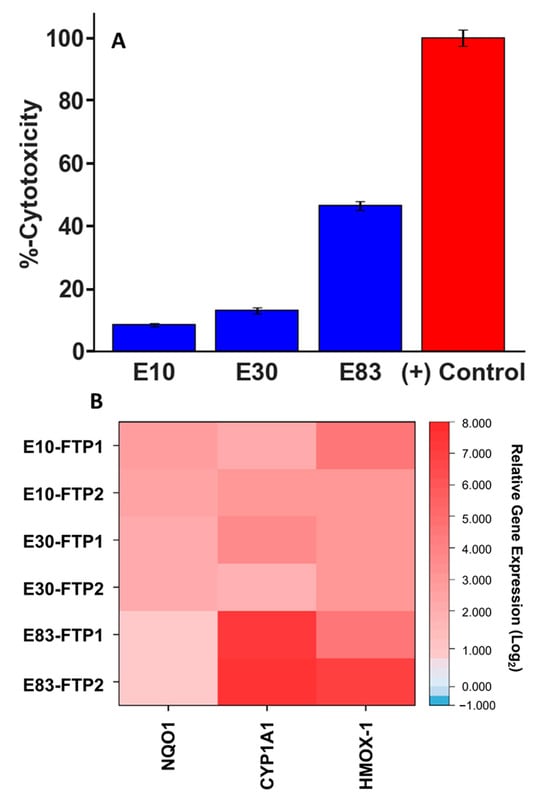

3.5. Toxicological Properties

Toxicological analysis was performed on the PM samples collected only over the FTP cycle. Figure 7A shows the cytotoxicity of the PM emissions, which was assessed using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay to measure membrane permeability of human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) after 24 h exposure to PM extracts. Exposure to PM emissions from the E10 and E30 blends did not result in substantial cytotoxicity (≤30%). The PM extract from the E30 fuel demonstrated slightly greater cytotoxicity compared to E10, but the results are not statistically significant. Our findings agree with earlier studies where they reported no great difference in cytotoxicity between ethanol blends, with their findings, as well as those reported in the current study, suggesting only minor or absent toxic effects of ethanol exhaust [19,33,34,35]. Sabbir Ahmed et al. [35] tested various gasoline fuels with and without ethanol in a GDI vehicle and reported no significant cytotoxicity in cells exposed to PM from these fuels. In contrast, exposure to the PM extract from the E83 fuel resulted in significant cytotoxicity after 24 h. While E83 emissions induced higher cytotoxicity compared to the other blends, the cause for this phenomenon remains unknown. It is theorized that less carbon available in the E83 fuel favored the formation of oxygenated organic species instead, which may be more capable of overly stressing cells.

Figure 7.

(A,B) Cytotoxicity for E10, E30, and E83 PM emissions evaluated by the LDH assay; results are expressed as percentage of LDH release relative to negative controls of unexposed cells maintained in the cell medium (A). Heatmap of gene expression in BEAS-2B cells exposed to PM emissions; results as log change (Log2) over the unexposed control.

The relative gene expression levels of NQO1, CYP1A1, and HMOX-1 after exposure of BEAS-2B cells to PM extracts of the test fuels are shown in Figure 7B. These genes were chosen as biomarkers of oxidative stress response as a result of exposure to exogenous agents [50,51,52]. Gene expression levels are reported as log change (Log2) over the unexposed control and were calculated using the comparative cycle threshold (2−ΔΔCT) method [53]. In agreement with the results from the cytotoxicity assay, E10 and E30 PM extracts resulted in only mild upregulation of the biomarkers, indicating that oxidative stress and injury to cells have occurred after 24 h exposure. E10 and E30 also demonstrated greater induction of NQO1 compared to E83, which is likely to have lower levels of quinone and aromatics emissions compared to the fuels with lower ethanol levels. Interestingly, E83 extracts demonstrated high expression of CYP1A1 and HMOX-1. HMOX-1 is a stress-induced enzyme frequently used as a biomarker of oxidative injury to cells caused by exogenous physicochemical agents that can produce ROS, while CYP1A1 is a phase I metabolic enzyme known to be induced by substrates via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). CYP1A1 has been implicated in the development of various cancers due to its ability to bioactivate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) to carcinogenic epoxide forms [50,54]. Typically, high cytotoxicity combined with upregulation of both HMOX-1 and CYP1A1 would suggest the presence of PAHs in the PM extracts, but with the dilution of aromatics for the splash-blended E83 fuel, it is reasonable to assume that PAHs were not the dominant path for inducing CYP1A1. It should be noted that McCaffery et al. [55] showed substantial increases in PAH emissions when they tested a PFI FFV over the FTP and reductions in PAH emissions for a GDI vehicle. While there is no evidence of elevated PAH formation with E83 for the current study, it is plausible that oxygenated organic species likely induced the CYP1A1 enzyme.

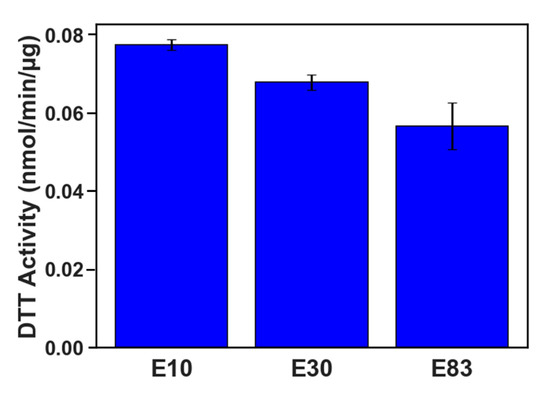

The oxidative potential of PM emissions, expressed by the DTT assay, and their ability to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) are shown in Figure 8. Overall, the DTT activity was reduced with increasing ethanol content and tracked the associated reductions in PM mass emissions for these fuels well. The reductions in DTT activity for E30 and E83 were 12.5% and 26.9%, respectively, compared to E10. Our findings agree with a previous study on a GDI FFV operated with E10, E30, and E78 blends, which also demonstrated that higher-ethanol blends reduce the potential of PM emissions to induce ROS production [19]. Sabbir Ahmed et al. [35] also showed that the high-ethanol blend exhibited the least oxidative potential compared to lower ethanol blends and neat gasoline fuels. The increased DTT activity of E10 and E30 supports the hypothesis that these PM extracts contain greater levels of quinones or quinone-like compounds that are quenched by NQO1 activity compared to E83. However, the lower overall oxidative potential of E83 contrasts with the increased cytotoxicity and CYP1A1/HMOX-1 expression seen in the E83 cell exposure. These results suggest that E83 PM contains fewer electrophilic/redox-active species capable of directly oxidizing DTT, but is capable of inducing oxidative stress in biological systems. One potential explanation is that the shear stress of the cells may be the major cause of high CYP1A1 expression, rather than an abundance of PAHs in the E83 PM. As evidenced by the high cytotoxicity compared to the other blends, E83 may induce cell damage through other mechanisms not measured in this study, promoting the expression of endogenous CYP1A1 activators [54,56,57].

Figure 8.

Oxidative stress for E10, E30, and E83 PM emissions over the FTP cycle measured by the DTT assay.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the emissions and toxicity effects associated with using high-ethanol blends in a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle equipped with an approved E85 conversion kit. The vehicle was tested with E10, E30, and E83 fuels under triplicate FTP and US06 drive cycles using a chassis dynamometer. Emissions measurements included regulated pollutants, mobile-source air toxics, and particulate emissions, along with their toxicological characteristics. The findings revealed consistently low NOx emissions, with notable reductions observed when using E30 and E83 across both test cycles. These decreases were likely attributed to ethanol’s higher heat of vaporization, which can lower combustion chamber temperatures for the higher-ethanol blends and suppress NOx formation. CO emissions increased with ethanol over the FTP, although the trend was not statistically significant. For the US06, CO emissions were seen at higher levels than those of the FTP, with E83 showing CO reductions compared to E10 and E30 fuels. Similarly, THC and NMHC emissions rose with the use of E30 and E83 relative to E10. Some of these increases reached statistical or near-statistical significance in both the FTP and US06 cycles. These higher emissions were likely the result of ethanol’s lower energy density, which requires greater fuel injection volumes, combined with ethanol’s higher heat of vaporization, which reduced the combustion temperature and slowed the oxidation rates of hydrocarbon species.

Low-molecular-weight aldehydes were present at the tailpipe, with formaldehyde and acetaldehyde exhibiting strong increases when E30 and E83 were used compared to E10. Tailpipe ethanol emissions, originating from unburnt ethanol fuel, showed statistically significant increases for E30 and E83 compared to E10. Additionally, BTEX emissions increased with ethanol content. We theorized that ethanol’s cooling effect might have affected the evaporation of lighter aromatic hydrocarbons, alkanes, and cycloalkanes, leading to their partial combustion. The ozone-forming potential (OFP) also rose with E30 and E83 blends due to the increased reactivity of the emitted compounds compared to E10. Oxygenated compounds (aldehydes and ethanol) were the dominant contributors to OFP, followed by aromatic hydrocarbons.

PM mass emissions for all test fuels remained below California’s stringent PM standard of 1 mg/mile. Both PM mass and black carbon emissions decreased with increasing ethanol content, with E83 showing statistically significant reductions during the FTP and US06 cycles. These reductions are likely due to the higher oxygen content and the dilution of aromatic hydrocarbons in the E30 and E83 blends. Solid particle number (SPN) emissions, measured at 10 nm (SPN10) and 23 nm (SPN23), also declined with greater ethanol use. Notably, SPN10 concentrations exceeded those of SPN23, suggesting that higher-ethanol blends may promote the formation of sub-23 nm solid particles. Higher-ethanol blending will reduce the oxidative stress in PM emissions, as measured by the DTT acellular assay. No major differences were found in cytotoxicity between E10 and E30 fuels, while E83 induced a greater cytotoxic response. Results for the oxidative stress biomarkers were mixed across the three fuels.

Overall, this study demonstrated that SULEV 30-certified PHEVs operating on high-content ethanol fuels produce emissions significantly lower than standard regulatory values. The use of ethanol provides additional benefits for most pollutants, especially for NOx and particulates. For California, this is an important finding, as many regions in the state are in non-attainment for ozone and PM emissions. On the other hand, some pollutants exhibited increases with higher-ethanol fuels, as well as increased toxicity. However, these findings are based on a single vehicle, making the conclusion of this work difficult to generalize. Therefore, further research is necessary to confirm and expand upon these results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18246461/s1, Figure S1: Speed–time profile of the FTP cycle; Figure S2: Speed–time profile of the US06 cycle; Figure S3: lReal-time SPN emissions over the cold-start and hot-running FTP phases (top panel) and the US06 cycle (bottom panel) as a function of engine RPM and vehicle speed; Table S1: Fuel properties of E10, E30, and E83 blends.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.; methodology, G.K. and Y.-H.L.; validation, Z.T., T.H., A.C. and G.K.; formal analysis, M.M., A.C. and T.H.; investigation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and G.K.; writing—review and editing, G.K.; supervision, G.K.; project administration, G.K.; funding acquisition, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Renewable Fuels Association (RFA).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics from Air Pollution to Climate Change; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.A.; Adelman, Z.; Fry, M.M.; West, J.J. The impact of individual anthropogenic emissions sectors on the global burden of human mortality due to ambient air pollution Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; LeBlanc, S.; Sandhu, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zheng, M. Decarbonization potential of future sustainable propulsion—A review of road transportation. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberger, S.I.; Konrad, M.; Philipps, F. Pollutant emissions analysis of three plug-in hybrid electric vehicles using different modes of operation and driving conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 234, 117612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansini, A.; Pavlovic, J.; Fontaras, G. Quantifying the real-world CO2 emissions and energy consumption of modern plug-in hybrid vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Song, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Energy Consumption and CO2 Emission from HEV, PHEV and BEV for China in the Past, Present and Future. Energies 2022, 15, 6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, P.; Leinonen, V.; Olin, M.; Vesisenaho, K.; Marjanen, P.; Jarvinen, A.; Simonen, P.; Markkula, L.; Kuuluvainen, H.; Keskinen, J.; et al. Real-world emissions of nanoparticles, particulate mass and black carbon from a plug-in hybrid vehicle compared to conventional gasoline vehicles. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.; Lacava, P.; Curto, P.; Penaranda, A.; Martinez, S.; Weissinger, F.; Martelli, A.; Santos, L. Decarbonizing Light Vehicles with Hydrous Ethanol: Performance Analysis of a Range-Extended PHEV Using Experimental and Simulation Techniques; SAE Technical Paper 2024-01-2161; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, J.R.; Pacca, S.A.; Goldemberg, J. The reduction of CO2e emissions in the transportation sector: Plug-in electric vehicles and biofuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Transit. 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Liu, Z.E.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Shuai, S. Effects of commercial ethanol-blended gasoline on emissions of a blended plug-in hybrid electric vehicle. Fuel 2025, 381, 133439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; McCaffery, C.; Ma, T.; Hao, P.; Durbin, T.D.; Johnson, K.C.; Karavalakis, G. Expanding the ethanol blend wall in California: Emissions comparison between E10 and E15. Fuel 2023, 350, 128836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, C.P.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T.J. Ethanol and air quality: Influence of fuel ethanol content on emissions and fuel economy of flexible fuel vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapano, F.; Sementa, P.; Vaglieco, B.M. Air-fuel mixing and combustion behavior of gasoline-ethanol blends in a GDI wall-guided turbocharged multi-cylinder optical engine. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Roth, P.; Durbin, T.; Karavalakis, G. Impacts of Gasoline Aromatic and Ethanol Levels on the Emissions from GDI Vehicles: Part 1. Influence on Regulated and Gaseous Toxic Pollutants. Fuel 2019, 252, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonen, H.; Karjalainen, P.; Saukko, E.; Saarikoski, S.; Aakko-Saksa, P.; Simonen, P.; Murtonen, T.; Maso, M.D.; Kuuluvainen, H.; Bloss, M.; et al. Influence of fuel ethanol content on primary emissions and secondary aerosol formation potential for a modern flex-fuel gasoline vehicle. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 5311–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Yang, J.; Peng, W.; Cocker, D.R., III; Durbin, T.D.; Asa-Awuku, A.; Karavalakis, G. Intermediate and high ethanol blends reduce secondary organic aerosol formation from gasoline direct injection vehicles. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 220, 117064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Roth, P.; Durbin, T.D.; Johnson, K.C.; Asa-Awuku, A.; Cocker, D.R., III; Karavalakis, G. Investigation of the effect of mid- and high-level ethanol blends on the particulate and the mobile source air toxic emissions from a gasoline direct injection flex fuel vehicle. Energy Fuels 2019, 22, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Roth, P.; Durbin, T.D.; Shafer, M.M.; Hemming, J.; Antkiewicz, D.; Asa-Awuku, A.; Karavalakis, G. Emissions from a flex fuel GDI vehicle operating on ethanol fuels show marked contrasts in chemical, physical and toxicological characteristics as a function of ethanol content. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 683, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maricq, M.M.; Szente, J.J.; Jahr, K. The impact of ethanol fuel blends on PM emissions from a light-duty GDI vehicle. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Roth, P.; Zhu, H.; Durbin, T.D.; Karavalakis, G. Impacts of Gasoline Aromatic and Ethanol Levels on the Emissions from GDI Vehicles: Part 2. Influence on particulate matter, black carbon, and nanoparticle emissions. Fuel 2019, 252, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Stone, R.; Richardson, D. A study of mixture preparation and PM emissions using a direct injection engine with stoichiometric gasoline/ethanol blends. Fuel 2012, 96, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Choi, K.; Myung, C.-L.; Lim, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, S. The impact of various ethanol-gasoline blends on particulates and unregulated gaseous emissions characteristics from a spark ignition direct injection (SIDI) passenger vehicle. Fuel 2017, 209, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, C.L.; Choi, K.; Cho, J.; Kim, K.; Baek, S.; Lim, Y.; Park, S. Evaluation of regulated, particulate, and BTEX emissions inventories from gasoline direct injection passenger car with various ethanol blended fuels under urban and rural driving cycles in Korea. Fuel 2020, 262, 116406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; Anderson, J.E.; Shen, W.; Wallington, T.J.; Wu, Y. Impacts of ethanol blended fuels and cold temperature on VOC emissions from gasoline vehicles in China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Wei, N.; Wu, L.; Mao, H. The characteristics and source analysis of VOCs emissions at roadside: Assess the impact of ethanol-gasoline implementation. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 263, 118670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Zardini, A.A.; Keuken, H.; Astorga, C. Impact of ethanol containing gasoline blends on emissions from a flex-fuel vehicle tested over the Worldwide Harmonized Light Duty Test Cycle (WLTC). Fuel 2015, 143, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisig, C.; Comte, P.; Gudel, M.; Czerwinski, J.; Mayer, A.; Muller, L.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Assessment of lung cell toxicity of various gasoline engine exhaust using a versatile in vitro exposure system. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.K.; Knuckles, T.L.; Akata, C.O.; Shohet, R.; McDonald, J.D.; Gigliotti, A.; Seagrave, J.C.; Campen, M.J. Gasoline exhaust emissions induce vascular remodeling pathways involved in atherosclerosis. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 95, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usemann, J.; Roth, M.; Bisig, C.; Comte, P.; Czerwinski, J.; Mayer, A.C.P.R.; Latzin, P.; Muller, L. Gasoline particle filter reduces oxidative DNA damage in bronchial epithelial cells after whole gasoline exhaust exposure in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Roth, P.; Ruehl, C.; Shafer, M.; Antkiewicz, D.; Durbin, T.; Cocker, D.; Asa-Awuku, A.; Karavalakis, G. Physical, Chemical, and Toxicological Characteristics of Particulate Emissions from Current Technology Gasoline Direct Injection Vehicles. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libalova, H.; Rossner, P., Jr.; Vrbova, K.; Brzicova, T.; Sikorova, J.; Vojtisek-Lom, M.; Beraneek, V.; Klema, J.; Ciganek, M.; Neca, J.; et al. Transcriptional response to organic compounds from diverse gasoline and biogasoline fuel emissions in human lung cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018, 48, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Usemann, J.; Bisig, C.; Comte, P.; Czerwinski, J.; Mayer, A.C.R.; Beier, K.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Latzin, P.; Muller, L. Effects of gasoline and ethanol-gasoline exhaust exposure on human bronchial epithelial and natural killer cells in vitro. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 45, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisig, C.; Roth, M.; Müller, L.; Comte, P.; Heeb, N.; Mayer, A.; Czerwinski, J.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Hazard identification of exhausts from gasoline-ethanol fuel blends using a multi-cellular human lung model. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbir Ahmed, C.M.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.Y.; Jiang, H.; Cullen, C.; Karavalakis, G.; Lin, Y.-H. Toxicological responses in human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) exposed to particulate matter emissions from gasoline fuels with varying aromatic and ethanol levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossner, P.; Cervena, T.; Vojtisek-Lom, M.; Neca, J.; Ciganek, M.; Vrbova, K.; Ambroz, A.; Novakova, Z.; Elzeinova, F.; Sima, M.; et al. Markers of lipid oxidation and inflammation in bronchial cells exposed to complete gasoline emissions and their organic extracts. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Rattanavaraha, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gold, A.; Surratt, J.; Lin, Y. Assessing the oxidative potential of isoprene-derived epoxides and secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 130, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanowitz, J.; McCormick, R.L. Effect of E85 on tailpipe emissions from light-duty vehicles. J. Air Waste Manag. 2009, 59, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassine, M.K.; La Pan, M. Impact of ethanol fuels on regulated tailpipe emissions. In Proceedings of the SAE 2012 World Congress & Exhibition, SAE Technical Paper Series, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–26 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune, J.-F.; Cologon, P.; Hayrault, P.; Heninge, M.; Leprovost, J.; Lemaire, J.; Anselmi, P.; Matrat, M. Impact of fuel ethanol content on regulated and non-regulated emissions monitored by various analytical techniques over flex-fuel and conversion kit applications. Fuel 2023, 334 Pt 2, 126669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, E.; Montagne, X.; Lahaye, J. Emission of alcohols and carbonyl compounds from a spark ignition engine. Emission of alcohols and carbonyl compounds from a spark ignition engine. Influence of fuel and air/fuel equivalence ratio. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2414–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarathy, S.M.; Obwald, P.; Hansen, N.; Kohse-Hoinghaus, K. Alcohol combustion chemistry. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014, 44, 40–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarante, P.H.B.; Sodre, J.R. Comparison of aldehyde emissions simulation with FTIR measurements in the exhaust of a spark ignition engine fuelled by ethanol. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 54, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ge, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Tan, J.; Hao, L.; Xu, H.; Hao, C.; Wang, J.; Qian, L. Effects of ethanol and aromatic contents of fuel on the non-regulated exhaust emissions and their ozone forming potential of E10-fueled China-6 compliant vehicles. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 264, 118688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnally, C.S.; Pfefferle, L.D. The effects of dimethyl ether and ethanol on benzene and soot formation in ethylene nonpremixed flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2007, 31, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, W.P.L. Updated Maximum Incremental Reactivity Scale and Hydrocarbon Bin Reactivities for Regulatory Applications, Prepared for California Air Resources Board Contract 07-339; California Air Resources Board: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009.

- de Melo, T.; Vicentini, P.; Loureiro, L.; Santos, E.; Almeida, J.C. Ozone formation—Reactivity emission factors of light-duty vehicles using gasoline and ethanol. In Proceedings of the 23rd SAE Brasil International Congress and Display, SAE Technical Paper, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 30 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Catapano, F.; Di Iorio, S.; Magno, A.; Sementa, P.; Vaglieco, B.M. Effect of ethanol blends, E10, E25 and E85 on sub-23 nm particle emissions and their volatile fraction at exhaust of a high-performance GDI engine over the WLTC. Fuel 2022, 327, 125184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Vanhanen, J.; Väkevä, M.; Martini, G. Investigation of vehicle exhaust sub-23 nm particle emissions. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzelino, R.; Jeney, V.; Soares, M.P. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stading, R.; Chu, C.; Couroucli, X.; Lingappan, K.; Moorthy, B. Molecular role of cytochrome P4501A enzymes in oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 20–21, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.S.; Berridge, M.V. Evidence for NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1)-mediated quinone-dependent redox cycling via plasma membrane electron transport: A sensitive cellular assay for NQO1. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y. Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carcinogens by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, C.; Durbin, T.D.; Johnson, K.C.; Karvalakis, G. The effect of ethanol and iso-butanol blends on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) emissions from PFI and GDI vehicles. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 2056–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, C.M.; Allen-Hoffmann, B.L. Cytochrome P450IA1 is rapidly induced in normal human keratinocytes in the absence of xenobiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16067–16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, D.E.; Sakurai, Y.; Weiss, D.; Vega, J.D.; Taylor, W.R.; Jo, H.; Eskin, S.G.; Marcus, C.B.; McIntire, L.V. Expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in human endothelial cells: Regulation by fluid shear stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 81, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).