Abstract

Coastal ecosystems represent a complex and dynamic interface for renewable energy development, combining solar radiation, coastal winds, and marine biomass. In regions such as La Guajira (Colombia), these resources create a unique opportunity to design hybrid systems that integrate solar, wind, and bio-based energy generation. This study applied a multicriteria assessment encompassing technical, economic, environmental, and social dimensions to evaluate the feasibility of this integration. The study adopts a narrative review approach supported by peer-reviewed literature, satellite-derived environmental datasets, and regional technical reports. Three criteria were used to assess the potential of these bioresources: (i) availability and spatiotemporal variability, (ii) physicochemical and energetic characteristics, and (iii) suitability for thermochemical and biochemical valorisation routes. Reported data indicate that pelagic Sargassum reaching the wider Caribbean contains 20–30% ash, 25–35% carbohydrates, and lower heating values between 8 and 12 MJ kg−1, while cactus biomass in arid environments can reach LHV of 13–16 MJ kg−1 and moisture contents below 15%. The coastal region of La Guajira also receives solar irradiation levels exceeding 6 kWh m−2 day−1 and wind speeds above 8 m s−1, creating favourable conditions for hybrid bioenergy–renewable systems. Finally, the multicriteria analysis reveals that integrating coastal renewable resources could drive the transition towards a circular, inclusive, and low-carbon bioeconomy in coastal territories such as La Guajira.

1. Introduction

Oceans cover approximately 75% of the planet’s surface and contain about 97% of the water available on Earth [1]. This huge marine area not only plays a vital role in regulating the climate and the water cycle but also provides multiple ecosystem services that in some cases have not been fully taken advantage of and could contribute greatly to the circular economy and economic development of marine-coastal areas. In the Colombian context, the strategic importance of the ocean is particularly relevant, since almost 50% of the national territory corresponds to maritime area, covering about 892,118 km2 [2]. This vast extension highlights the country’s great potential for the sustainable use of marine and coastal resources. At the global scale, marine biomass valorisation has become a strategic pillar of the blue bioeconomy, promoted by international frameworks such as the European Union’s Blue Growth Strategy [3] and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Ocean Economy Agenda [4]. Coastal nations of Asia and Europe such as Norway, Portugal, Japan, and China have advanced in developing marine-based bioindustries, transforming macroalgae, seagrasses, and other coastal resources into biofuels, bioplastics, and biochemicals. These initiatives demonstrate that the sustainable use of marine resources can simultaneously drive innovation, reduce carbon emissions, and enhance coastal resilience. In Latin America and the Caribbean, countries such as Costa Rica, Brazil, and Barbados have begun to explore similar strategies within their national bioeconomy frameworks [4,5].

Bioeconomy materials such as biomass or natural resources such as water and wind have been used as solutions to various issues related to climate change and dependence on fossil fuels over the years. Today, these resources are mainly used to produce energy and value-added products [6]. However, these transformations require time, support from different stakeholders and a continuous effort in research, development, and innovation. In coastal areas, it is possible to find these resources available, and it is interesting to characterise and identify these raw materials.

In the Caribbean region of Colombia, and particularly in La Guajira, there is a latent problem in terms of access to energy for the population and the sustainable and appropriate use of available waste or biomass [7]. Efforts are being made to identify the potential use of biomass, water, and wind in this area to establish the best strategies for improving the quality of life of the population and ensuring economic, environmental and technological sustainability.

Previous studies have examined the characterisation and potential uses or transformations of these resources into value-added products and energy. In the case of marine biomass, studies focused on seagrasses and macroalgae predominate, and in the case of renewable energies, studies on the use of seawater and coastal winds predominate. For example, macroalgae, in general, have proven to be a rich source of bioactive compounds that can be used in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, or nutraceutical industries. There is also growing interest in the use of this raw material in the production of biofuels and biomaterials, which demonstrates the versatility of seagrasses and their high potential for sustainable use [8]. Similarly, the importance of seagrasses in the aquatic ecosystem has been studied due to their capacity for efficient carbon capture [9]. However, when these pastures become waste, studies have been reported that demonstrate the potential of this raw material in wastewater treatment and also as a source of biomaterials and bioenergy [10].

On the other hand, both water and sea winds have been proposed as unconventional renewable energy sources, and as an encouraging and very favourable solution for coastal areas. Offshore wind energy has recently gained popularity because it is more powerful at sea than on land [11]. According to statistical data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), wind energy accounts for 36% of the total market growth of renewable energies [12]. In the case of seawater, the main reported use has been the production of drinking water through desalination processes (using various clean technologies, such as solar energy) [13]. Furthermore, in the case of sea salt, its potential use in the production of sodium-ion batteries has been studied [1]. This huge marine area not only plays a vital role in climate regularion, but it is a promising alternative for energy storage, such as hydrogen [14].

Therefore, this review aims to (i) synthesise the available evidence on coastal biomass resources in La Guajira, with emphasis on pelagic Sargassum and some coastal residues; (ii) describe their physicochemical and energetic characteristics; and (iii) assess their potential applicability within bioenergy-oriented valorisation pathways. This structure allows linking global biomass dynamics with the regional conditions of La Guajira.

2. Methodology

This review adopts a structured and comprehensive approach to synthesise the current knowledge on the valorisation potential of marine–coastal biomass to produce high-value bioproducts and its energetic use, considering both global and local advancements, with a specific focus on the context of La Guajira, Colombia.

A combination of bibliometric and thematic content analysis methods was employed to identify, analyse and interpret relevant peer-reviewed scientific literature. Articles, theses and book chapters were considered, primarily in English, although a few were included in Spanish, prioritising studies published within the last decade. The study followed a structured literature search based on PRISMA principles, adapted to a narrative review approach. The bibliographic search covered the period from 2010 to 2024 and was conducted in the Scopus and Google Scholar databases using different combinations of keywords and Boolean operators (AND, OR) related to coastal biomass, Sargassum, xerophytic feedstocks, macroalgal valorisation, coastal energy potential and the Caribbean region. Additional institutional sources, such as IDEAM, INVEMAR and satellite-derived environmental datasets, were also consulted to complement the scientific evidence.

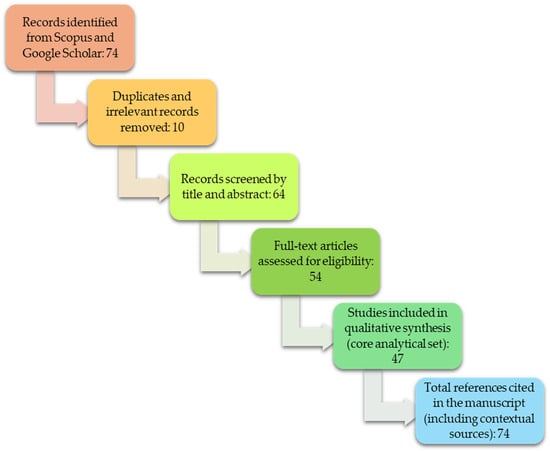

The records obtained were organised in a Microsoft Excel matrix to perform the initial screening, reviewing titles, abstracts, biomass type, study objective, study design, bioproducts produced, results and conclusions. Of the 74 documents initially identified, 10 were removed as duplicates or for irrelevance after title–abstract screening, resulting in 64 documents assessed for eligibility. Subsequently, specific sections or, in some cases, the full text of the selected articles were examined to confirm their relevance. In total, 47 documents were included in the core qualitative synthesis, although 74 sources were ultimately cited in the manuscript when including contextual and institutional documents. The initial search identified 74 records across all topics, of which 22 were related to seagrass biomass (9 included), 20 to Sargassum (10 included), 15 to cactus species (13 included), 13 to seawater energy potential (11 included), and 4 to coastal wind and solar radiation energy potential. Inclusion decisions were guided by two criteria: (i) documented relevance to coastal or arid biomass systems in the Caribbean or comparable environments, and (ii) availability of quantitative or qualitative information useful for assessing physicochemical properties, resource availability or bioenergy potential. The overall process of literature identification, screening, and inclusion is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature screening and inclusion process, adapted from PRISMA 2020.

The most relevant information was extracted and analysed qualitatively, focusing on the type of marine–coastal biomass and its potential for bioproduct and bioenergy generation. Additionally, the energy potential of seawater salinity and coastal wind was broadly examined. A comparative analysis was also conducted among the three types of biomasses studied (cactus, sargassum, and seagrass), considering their potential within the framework of coastal and offshore renewable energy systems.

To support this comparative assessment, a Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA) was implemented using the software DEFINITE 3.1. The MCA served as a complementary decision-support tool to integrate the quantitative and qualitative findings and to evaluate the sustainability of each biomass alternative under environmental, technical, economic, and social dimensions.

The input data for the MCA were derived from the quantitative energy potential estimations and the qualitative evaluation of sustainability parameters described throughout the study. Seven criteria were established to represent key aspects of biomass valorisation: energy potential, Technological Readiness Level (TRL), economic feasibility, environmental sustainability, social benefit and local integration, availability and logistic viability, and circular bioeconomy potential.

Quantitative variables were introduced as ratio data (e.g., GWh·yr−1), while qualitative criteria were normalised on ordinal scales (1–5) to ensure comparability. The normalisation was performed using the maximum method, and aggregation followed the Weighted Linear Combination (WLC) technique, which allows assigning relative importance values to each criterion based on literature support and expert judgement. This approach ensures transparency and consistency with the sustainability framework adopted for evaluating marine–coastal biomass in La Guajira.

3. Global Overview

3.1. Raw Materials

3.1.1. Seagrases

Seagrass beds are distributed along the narrow coastal strips of almost every continent except Antarctica. These ecosystems play a key role in mitigating climate change due to their high capacity for CO2 sequestration and storage [15]. Although they represent only 2% of global vegetation cover, their carbon sequestration efficiency is superior, as they are capable of capturing up to ten times more carbon than terrestrial biological ecosystems, making them one of the most important carbon sinks in the world’s coastal areas. It is estimated that they contribute between 10 and 18% of the total carbon captured globally. This efficiency in carbon capture stems from their ability to produce large amounts of plant biomass, which stores anoxic sediments. Therefore, the larger the area and the longer the seagrass beds, the greater the carbon sequestration [9].

Coastal biomass is carried by ocean currents to the shores, where it accumulates in large quantities. It usually serves as food for various species, while another portion tends to decompose or even be burned [16]. For this reason, several coastal regions around the world have found ways to utilise marine biomass, specifically seagrass, in various sectors such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, food, bioenergy, construction materials and water treatment [10]. For example, in the Mediterranean Sea area, it is common to find building materials made from seagrass biomass used for thermal insulation, as well as plant substrate substitutes to promote rooting and growth of flora. In Norway, Scotland, and the Baltic Sea region, sargassum biomass has been found to be valuable for: essential macro and microelements used in biofertilisers or soil amendments and for biosorbents applied to biosorption used for the removal of various aquatic, organic and inorganic pollutants. In the Baltic Sea area of the Netherlands and Sweden, seagrass biomass is valued to produce bio-based compost applied to fertilisers for crop substrates and energy production. In Limassol, Cyprus, seagrass biomass is transformed into adsorbent materials for use in phosphate removal in wastewater treatment [10]. In India, Arya et al. evaluated seagrasses of the species Halodule uninervis, Thalassia hemprichii, Enhalus acoroides, Cymodocea serrulata, and Syringodium isoetifolium [17] for the extraction of proteins and peptides, where the filtrate is used to manufacture various products, such as peptide-based products for the pharmaceutical industry. In Spain, seagrass leaves were used to make bricks, replacing sawdust with fibres from the leaves of the Mediterranean Sea endemic species Posidonia oceanica [18].

3.1.2. Algae and Sargassum

First-generation biomass refers to conventional feedstocks derived from food crops such as sugarcane or maize, whereas second-generation biomass encompasses non-food lignocellulosic residues including agricultural by-products and forestry waste. Third-generation biomass, by contrast, comprises high-productivity autotrophic organisms such as algae and macroalgae, which do not compete with agricultural land and exhibit rapid growth rates. These distinctions are relevant, as the valorisation strategies explored in this review are aligned with third-generation resources.

Among the biomass belonging to third-generation sources are algae, which reproduce rapidly and have a simple structure compared to second- and first-generation biomass [19]. The use of this type of biomass provides a viable opportunity for obtaining high value-added products, especially biofuels. To access useful platforms for the transformation of this type of biomass, there are currently multiple technologies for different transformation routes, and much research is aimed at proposing various processes such as biorefineries [20,21,22]. These systems are useful and applicable at different scales, and fractions of this biomass such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, proteins, among other compounds, can be valorised [23]. Table 1 shows the cases in which proposals for transformation processes by third-generation biorefineries have been designed, and the trending products to be obtained.

Table 1.

Examples of trending products obtained from the use of third-generation biomass in biorefinery systems.

However, one of the most important and studied seaweeds around the world is Sargassum, which is present in all ocean basins, with more than 350 species. Specifically, in the Atlantic Ocean, there are several species, among which Sargassum fluitans and Sargassum natans stand out, forming what is called the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB) [27]. Sargassum is mainly found in tropical and subtropical marine environments and grows on reefs. Sargassum is one of the main types of ‘brown’ algae and is characterised by being an excellent biosorbent of multiple metal ions [28].

Most species of sargassum, after their reproductive life cycle, detach from the seabed and form floating algae mats. Some other species directly reproduce as floating biomass in the sea [29]. In the long term, these phenomena cause problems on the coast, as the current accumulates them on the shores of beaches. This generates multiple environmental, social and even economic problems [30]. In social and economic terms, the accumulation of sargassum on the coast affects tourism and the work of fishing boats, which are the economic livelihood of the inhabitants of the area. Furthermore, in environmental terms, the negative impact lies in the accumulation of this seaweed on the coast and its limited use as a raw material for obtaining new bioproducts. In 2019, more than 1 million metric tonnes of sargassum accumulated on Caribbean beaches (especially in tourist areas), which clearly demonstrates the problems this can cause on the coast [31].

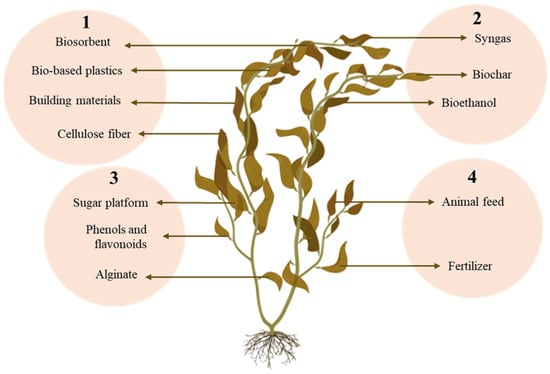

As a result, research has demonstrated the high potential of using sargassum to obtain various bioproducts (see Figure 2). These range from biomaterials such as biosorbents, plastics, construction materials and cellulose fibres for paper, energy products such as synthesis gas, biochar and biofuels such as ethanol, to compounds such as sugars, phenols, flavonoids, polysaccharides, animal feed and fertilisers.

Figure 2.

Group of bioproducts that have been studied for production from Sargassum. (1) biomaterials; (2) energy carriers; (3) biocomposites; and (4) other products. Source: Authors.

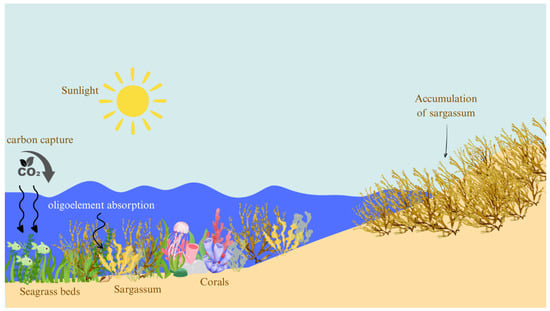

This biomass tends to accumulate, and this phenomenon can be beneficial at moderate densities, as it provides food and shelter for various marine species and strengthens beaches by preventing erosion, as well as providing nutrients to coastal habitats [32]. However, when this accumulation is very high, it can have negative effects on two levels: accumulation on the surface and accumulation on beaches. In the case of surface accumulation, the accumulation of sargassum can prevent light penetration, affecting corals and marine life in general. In the case of accumulation on beaches, sargassum can become a problem for animal life such as turtles that reach the shores, and a problem as waste, being a source of bad odours and the spread of disease, among other effects [32]. Figure 3 illustrates the dynamics of the ecosystem where algae live and interact, which can be disrupted in the event of excessive accumulation.

Figure 3.

General ecological interactions of benthic Sargassum within coastal–marine environments. Source: Adapted from [33]. Although pelagic S. natans and S. fluitans are the focus of this review, their broader ecological context shares several of the interactions illustrated here.

In this review, the term “Sargassum” refers specifically to the pelagic holopelagic species Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans, which form floating mats in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean. Although Figure 3 illustrates the general ecological dynamics of benthic Sargassum, the bioproduct applications discussed in this study are based exclusively on pelagic biomass, which is the type that accumulates on Caribbean coasts and is harvested for valorisation.

3.1.3. Cacti

Cacti are xerophytic plants belonging to the Cactaceae family, widely distributed in arid and dry ecosystems worldwide. They are distinguished by their ability to store water in their leaves, stems and roots for long periods, allowing them to survive under extreme climatic conditions [34]. Among them, the Agave and Opuntia species stand out for their high water use efficiency and remarkable resistance to water scarcity, thanks to their photosynthetic system of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM). This mechanism allows them to open their stomata at night to fix CO2, taking advantage of hours of lower water loss through evaporation. In contrast, during the day they keep their stomata closed, thus reducing transpiration and limiting the net entry of CO2 [35]. In addition, cacti are part of second-generation biomass, as they are non-food lignocellulosic plants, making them a sustainable alternative for obtaining bioenergy and other bioproducts.

A wide variety of cactus species are distributed around the world, which has favoured their availability for use in the production of various bioproducts (see Table 2). In different regions of Italy, the biomass of species such as Opuntia ficus-indica, particularly the Sanguigna and Surfarina varieties, has been used to obtain various high-value products. These include seed oils, rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic and oleic acids, as well as γ-tocopherol and carotenoids, with great nutritional potential [36]. Processes have also been developed to obtain pectins for the food and cosmetics industries, bioactive extracts (antioxidants and pigments), biogas through anaerobic digestion, and functional juices enriched with betalains [37]. On the other hand, the mucilage extracted from Opuntia ficus-indica has been used as a consolidating agent in paper manufacturing, as well as in restoration treatments for ancient documents and works on paper. This material is considered a reversible, economical, non-toxic and biodegradable alternative, highly effective for fixing and preserving colour in historical media [38]. In Africa, more specifically in Tunisia, the biomass of fibrous layers of the Opuntia ficus-indica species, which has very good mechanical resistance and thermal stability, has been used to produce biocomposites, packaging materials, paper, and other applications of natural fibres [39]. Meanwhile, in Mexico, it has been demonstrated that the cultivation of species such as Opuntia and Agave helps to mitigate soil erosion and combat desertification. These species are also highly valued in the production of food, fodder, and spirits such as tequila and mezcal in crops. According to [35], it is possible to valorise the biomass of these species as mucilage, cladodes, fibres and bagasse in the production of biogas, bio-synthetic natural gas (bio-SNG), biodiesel, and fructans such as insulin, which represents a great alternative for reducing dependence on fossil fuels in Mexico. It should be noted that throughout Mexico, there is a high rate of semi-arid and arid areas, which favours the organic and sustainable cultivation of cacti of these species, without compromising local biodiversity and promoting soil health. In fact, some Mexican biorefineries use biomass from the Opuntia Ficus species grown in experimental gardens at the National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research to produce 99.7% anhydrous bioethanol through enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation [40]. In Ecuador, bioplastics have been produced from the extraction and gelation of the mucilage of Opuntia ficus-indica, and it has been discovered that the greater the drought to which the cacti are subjected, the greater the amount of mucilage they can contain, and therefore the greater the amount of bioplastics that can be produced [41].

Table 2.

Applications of cactus biomass in different countries.

On the other hand, cacti of the genus Stenocereus (Berger) Riccob are distributed throughout the American continent, from the arid areas of southern Arizona to northern Colombia and Venezuela. Among its most common species are plants known as pitayas, whose fruits are used for human consumption. In countries such as Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, they are used in food products such as jams, jellies, and pickles [42].

3.1.4. Saltwater Energy Potential

Marine water resources are key to regulating the global climate, the carbon cycle and cloud formation, and constitute one of the largest sources of renewable energy globally. There is great energy potential in the use of marine water resources. There are currently five types of water-to-energy conversion: tidal energy derived from the periodic movement of the tides, wave energy that harnesses the kinetic and potential energy of surface waves, ocean current energy, ocean thermal energy based on the temperature gradient between surface and deep waters, and salinity gradient energy, also known as osmotic energy [43]. These mechanisms have been the subject of growing interest due to their high energy potential, particularly in coastal regions and archipelagos where the availability of other renewable sources is limited. Research has shown that osmotic energy is released when solutions of different salinity, such as seawater and freshwater, are mixed. In areas where there are hypersaline basins on the ocean floor, the controlled mixing of these waters can release energy continuously, representing a renewable and stable source, albeit with moderate energy density. The magnitude of this potential depends on the size of the basins and the difference in salinity, but it is estimated that it could be comparable to or even greater than other marine technologies such as ocean thermal energy conversion [44]. On the ocean thermal energy side, the temperature difference between surface and deep waters can be exploited to generate electricity thanks to the oceans’ ability to store most of the heat from the Earth’s climate system [45].

Saltwater is also a strategic resource in terms of access to drinking water for coastal communities. In this context, desalination has established itself as a key alternative for ensuring water supply in areas with water stress and easy access to the coast. Technologies such as reverse osmosis, multi-stage distillation and electrodialysis have evolved towards more sustainable schemes, integrating renewable sources such as solar, wind and, more recently, tidal and wave energy, to reduce the high energy consumption of these processes.

3.2. Technologies Applied for Each Raw Material

The use of the identified raw material (seagrass, sargassum algae, cactus, and saline resources from seawater) involves the adoption of different technological routes, each with varying degrees of development and maturity. To assess their viability for bioeconomy and sustainable energy initiatives, the TRL was established for each one, based on a review of documentation and updated technical references. Table 3 summarises the main findings prior to the detailed discussion.

Table 3.

TRL for the main technologies applied for each coastal raw material.

Seagrasses, such as Posidonia oceanica, represent an abundant biomass in temperate and tropical coastal areas, with potential for recovery in circular economy schemes. The main technological routes identified focus on four areas: composting, pollutant adsorption, construction materials, and extraction of bioactive compounds. Composting and biofertiliser formulation are among the most mature applications, with evidence from community and pilot projects in the Baltic and Mediterranean basins demonstrating their agronomic effectiveness and odour control, reaching a TRL of 6–7. In contrast, the use of this biomass as a natural adsorbent for the removal of metals or phosphates in wastewater has shown excellent results in the laboratory and some pilot field tests, reaching intermediate levels (TRL 5–7). The incorporation of Posidonia fibres into lightweight panels and bricks for sustainable construction is at an advanced experimental stage (TRL 5–6), while the extraction of proteins and peptides for cosmetic or pharmaceutical purposes remains at the laboratory scale (TRL 4–5). In general, the routes associated with composting and adsorption are the most mature and have the lowest technological risk, although industrial applications of composite materials could offer greater added value in the medium term. The main limitations to scaling up include collection logistics, compositional variability of the material, the presence of salts, and the lack of specific regulations for its industrial recovery [18,44,46].

On the other hand, HTL is currently the most advanced technology for energy recovery from algae, with TRL between 7 and 8, thanks to recent industrial developments in continuous reactors and demonstration plants (e.g., PNNL and VITO EnergyVille). Anaerobic digestion, applied to both fresh sargassum and mixtures with agricultural waste, is also highly mature (TRL 6–7) and constitutes a well-established route for biogas production. Pyrolysis aimed at obtaining biochar or bio-oil is in the pilot stages (TRL 5–7), while fractionation for high-value bioproducts—such as pigments, antioxidants, or cosmetic compounds—remains in the research phase (TRL 4–6). Overall, thermochemical routes exhibit a higher degree of maturity, although there are technical challenges associated with high salt content, biomass variability, and drying and transport costs. Recent initiatives for integrated biorefineries for sargassum in the Caribbean demonstrate the growing interest in its sustainable use, combining the removal of coastal waste with the generation of economic value [21,22,23].

In the case of cactus, enzymatic fermentation for bioethanol is in a consolidated pilot phase (TRL 6–7), with reports of experimental plants in Mexico achieving yields and purities comparable to first-generation biofuels. Similarly, the anaerobic digestion of cactus and its agro-industrial residues have been validated at the pilot scale (TRL 6–7), standing out for its high efficiency in regions with water constraints. Mucilage extraction and bioplastic or biodegradable film formulation lines are still experimental (TRL 4–6), although they are evolving rapidly, driven by demand for alternatives to petroleum-based plastics. Finally, the recovery of oils, pectins, and pigments represents an additional opportunity for product diversification within small-scale biorefineries. The main technological challenge lies in standardising the raw material, optimising enzymatic pretreatments and defining viable business models for rural or semi-arid regions [39,40,41].

Among ocean resources, such as sea salt, reverse osmosis is the only fully commercial technology, with a TRL of 9 and widespread implementation worldwide. Tidal energy, based on current turbines and wave converters, has devices in commercial operation or advanced demonstration (TRL 7–9), especially in countries with high tidal resources. Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC), which exploits the thermal gradient between surface and deep waters, is in the technical demonstration phase (TRL 5–7), with pilot projects in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Finally, osmotic energy combines the difference in salinity between fresh and salt water to generate electricity; although its technical viability has been proven in a pilot plant, the high costs of membranes and their durability limit its scaling up (TRL 5–6). The integration of these technologies into hybrid systems, for example, OTEC + desalination or osmotic energy + reverse osmosis desalination, represents an interesting opportunity for coastal regions [44,45].

4. Case of Study: La Guajira, Colombia

4.1. Seagrasses Locally

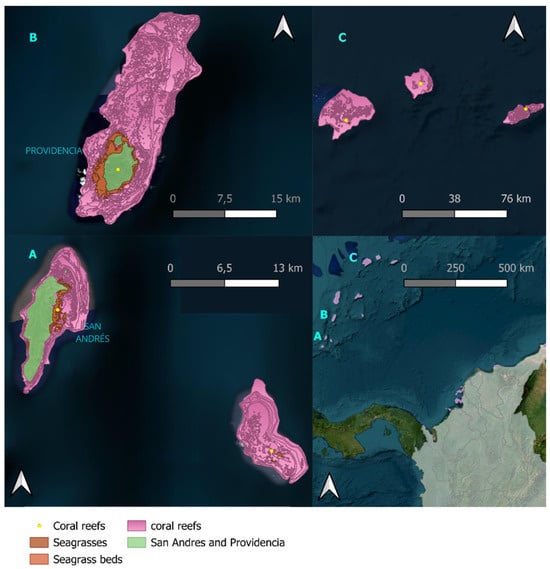

In Colombia, more than 80% of seagrass beds are found in the continental Caribbean, mainly in the department of La Guajira, and in the western island region, on the island of San Andrés, which has been part of the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve since 2000 and the Marine Protected Area (MPA) since 2005 [9]. Both regions are home to ecosystems that are fundamental to the conservation of marine biodiversity and its ecological functions. In the insular zone, there is a basin with a high presence of corals, sea urchins, calcareous macroalgae, and seagrasses covering an area of approximately 399 ha, as shown in Figure 4. The coral area is larger than the territorial area of the islands.

Figure 4.

Seagrass beds in the Colombian insular zone. The distribution of seagrasses in the island zone extends from the islands of (A) San Andrés, (B) Providencia to (C) Coral reefs and protected areas to the north. Source: Authors.

La Guajira has approximately 56,386 ha of seagrass composed of species such as Thalassia testudinum and Syringofium filiforme, also known as “manatee grass”, distributed between 0 and 15 m deep [9,47]. Based on a georeferencing analysis performed using QGIS 3.44 software, it was determined that the total seagrass coverage in the country is approximately 64,736 ha. Table 4 shows the distribution by department.

Table 4.

Area of Colombian seagrass beds by department.

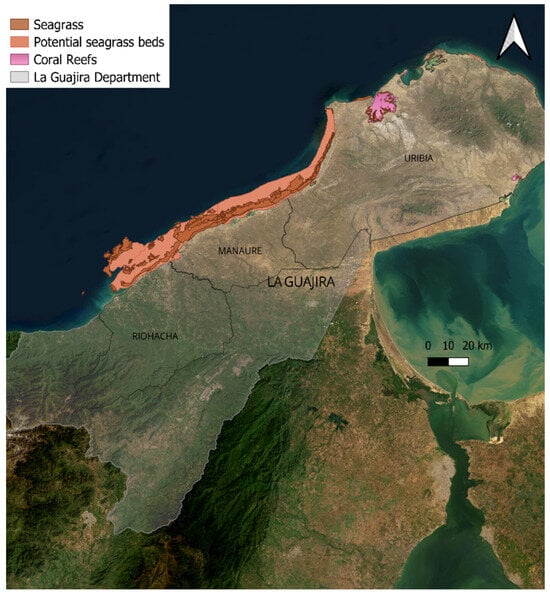

Of these departments, the area of interest for study is the department of La Guajira. To understand its geographical location, the map in Figure 5 was developed, which explicitly indicates the location of seagrass beds (represented in brown on the map) and potential areas where seagrass beds are likely to exist but have not yet been characterised. In addition, some seagrasses are found in coral areas, which should be conserved and protected due to their importance in marine and ecosystem biodiversity conservation. The seagrasses are located on the coasts of the municipalities of Riohacha, Manaure, and Uribia.

Figure 5.

Seagrass beds distributed throughout La Guajira, Colombia. Source: Authors.

Potential areas with seagrass presence have also been identified, which are shown in light red on the map in Figure 5. The area corresponding to these zones in Colombia is detailed in Table 5, which shows the total extent of each one.

Table 5.

Areas of potential seagrass meadows.

La Guajira has the largest amount of seagrass and potential seagrass meadows in Colombia, most of which are located near the central west coast of the department. This offers great potential for traditional communities to take advantage of seagrass biomass to produce bioproducts, thereby boosting their economy and trade.

The seagrasses of the Colombian Caribbean are key ecosystems in terms of biodiversity, not only because of their carbon capture capacity, which in areas such as the Seaflower Biosphere Reserve and the Marine Protected Area makes them carbon sinks [9], but also because of their other ecosystem services such as coastal protection, support for marine and terrestrial food webs, shelter and food for different marine species, and are perfect areas for the reproduction of different species of molluscs, fish, and crustaceans. They have high potential for connecting breeding habitats and coral reefs; in short, they are the lifeblood of marine biodiversity [19,48,49]. In addition, they are bioindicators of marine quality, as species such as Thalassia testudinum, which is identified as the most abundant in the region, are capable of absorbing and accumulating essential, heavy, and highly toxic metals and trace elements in their tissues rich in functional groups such as hydroxyls, sulphates, and carboxyl in the cell walls of polysaccharides, which favour the retention of these compounds. The efficiency of elimination and accumulation of elements by Thalassia testudinum is presented in Table 6, which details the wide variety of chemical elements that this species can absorb, expressed in micrograms of the element per kilogram of dry tissue; these concentrations were determined by the study of [19] using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis.

Table 6.

Range of trace element concentrations that may be present in 1 kg of dried seaweed.

Quantitatively, the mapped seagrass area in La Guajira covers approximately 56,386.41 hectares. The dry biomass density of these meadows ranges from 200 to 1000 g/m2 (0.2–1 kg·m−2), although values may vary depending on species composition, seasonality, and local environmental conditions [50]. Regarding energy potential, the Lower Heating Value (LHV) of aquatic biomass typically ranges between 15 and 20 MJ·kg−1 of dry weight. Pyrolysis studies of marine macroalgae have reported higher heating values for solid products (19–25 MJ·kg−1), whereas the original biomass exhibits lower energy yields due to its high ash and moisture content [51].

The total standing biomass (M) was calculated by multiplying the total area (A) by the dry biomass density (ρ), while the theoretical energy potential (E) was estimated as

The results for minimum, average and maximum scenarios are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Calculations of the energy potential of seagrasses in La Guajira.

Results indicate that the total dry biomass in La Guajira ranges between approximately 112,773 and 563,864 t, corresponding to a theoretical energy potential of 470–3132 GWh.

These figures represent the order of magnitude of energy stored in seagrass biomass; however, their direct exploitation would have significant ecological implications. Therefore, these values should be interpreted solely as theoretical reference estimates within the broader context of blue bioeconomy potential. However, the seagrasses under consideration are in seagrass beds, which are ecosystems that are strategic for absorbing carbon and thus mitigate the accelerated acidification of the oceans.

4.2. Sargassum Locally

In the Colombian Caribbean, minor sargassum strandings have been reported on islands such as San Andrés and Providencia, and in areas of La Boquilla (Cartagena) and Tayrona Park (Magdalena). Studies by the Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras—INVEMAR have recorded sporadic occurrences in the Colombian Caribbean Sea, especially between July and October, when Caribbean currents transport sargassum aggregates from the east [52,53]. In the coastal area of La Guajira, particularly Cabo de la Vela, Manaure and Puerto Bolívar, sargassum is not abundant, mainly due to the following:

- Caribbean ocean currents flowing westward, but the main flow of the sargassum belt passes further north, skirting the Greater Antilles.

- High wave energy and trade winds that hinder the accumulation of floating biomass.

- Slightly higher temperature and salinity and arid areas with little nutrient runoff (unlike areas further south in the Caribbean).

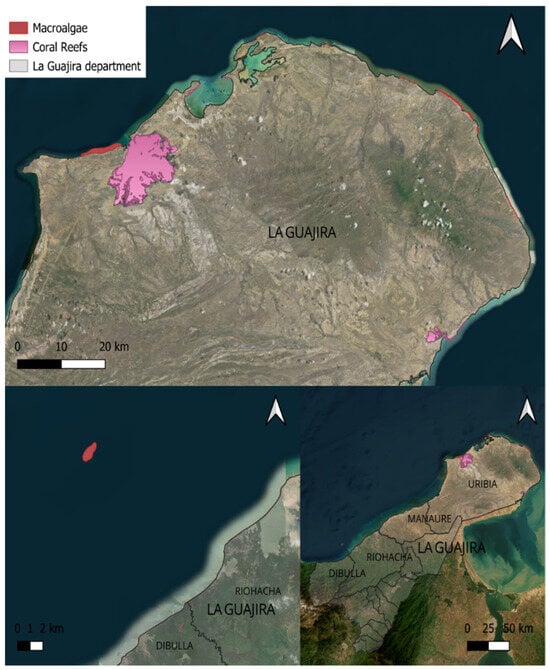

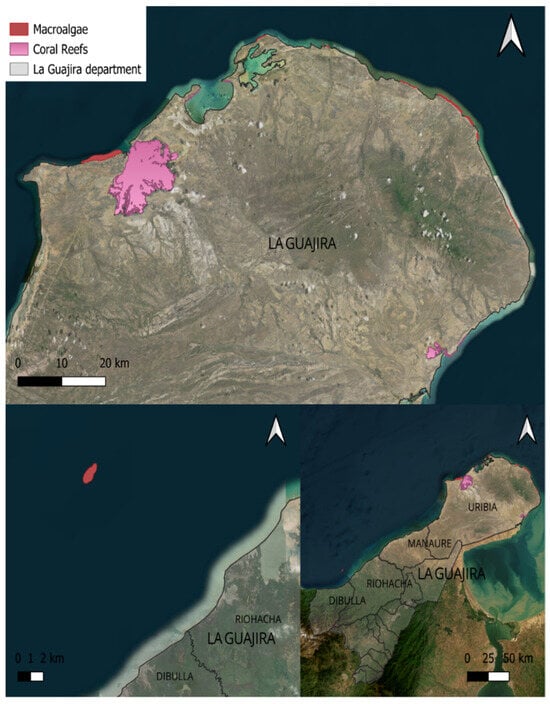

However, fishermen and coastal communities have reported small seasonal accumulations of floating macroalgae (not always Sargassum natans or Sargassum fluitans, but also Dictyota, Gracilaria, or even detached seagrass debris). These local macroalgae could have a similar biochemical composition for energy uses (high polysaccharide content, low lignin). In La Guajira, macroalgae ecosystems have been observed where sargassum growth can be found. Figure 6 shows the areas of La Guajira where these ecosystems are located.

Figure 6.

Macroalgae ecosystems where sargassum species can be present in La Guajira. Source: Authors.

The Caribbean Sea can receive millions of t of floating Sargassum each year, although its spatial and temporal distribution is highly variable, depending on ocean currents, wind patterns, and regional climatic conditions. To date, there are no continuous and up-to-date quantitative records of the exact amount of Sargassum reaching the coasts of La Guajira (Colombia). However, it is estimated that the total biomass of macroalgae reaching the coasts of La Guajira—including Sargassum spp. and other macroalgae—is approximately 1.1 t·km−2, covering the coastal stretch from Riohacha to Punta Gallinas across an estimated 4220 km2, corresponding to about 4640 t of fresh biomass per year [52,53].

Complementarily, the Sargassum Watch System (SaWS) from the University of South Florida has reported, through monthly satellite observations, a significant increase in floating Sargassum biomass in the tropical Atlantic and the western Caribbean, particularly during the past decade. In 2025, critical accumulations were recorded, with a total of 37–38 million t of floating Sargassum detected across the tropical Atlantic, of which around 10% was concentrated in the western Caribbean. Considering the proportion of coastline corresponding to Colombia (approximately 6%) and the fraction that effectively beaches (10–30%), it is estimated that between 23,000 and 68,000 t of fresh Sargassum may reach the Colombian Caribbean annually, with recurrent and significant landings reported in San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina islands, and to a lesser extent along La Guajira, particularly during the months of April, May, and July.

For the quantitative analysis, the SaWS satellite-based projection was considered, for 2025 year. It was assumed that Sargassum biomass contains 80% moisture and has an LHV ranging from 10 to 12 MJ·kg−1 [51].

Thus, the theoretical energy potential was calculated as:

where represents the estimated dry biomass.

Usable energy was obtained by applying an average efficiency of 30% to account for losses in the conversion process of useful energy. The results are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Calculations of the energy potential of sargassum in La Guajira.

The results indicate that the theoretical energy potential of sargassum biomass reaching the Colombian Caribbean and particularly La Guajira ranges from approximately 12.8 to 45.3 GWh·yr−1, depending on the annual biomass influx.

4.3. Cacti Locally

In Colombia, the greatest diversity of Cactaceae is mainly concentrated in the dry inter-Andean valleys and in arid and semi-arid regions, with notable records in the departments of La Guajira, Magdalena, Huila (in the Tatacoa Desert), among others (see Figure 7). By 2013, 42 species had been found in the country [54], and in the Caribbean region, there are 12 genera and 26 species and subspecies [55]. Table 9 presents some of the most common cactus species found in the Colombian Caribbean, along with their scientific names, subspecies, and common names.

Figure 7.

Regions where a variety of cacti are distributed in Colombia. Source: Authors.

Table 9.

Cactus species found in the Colombian Caribbean.

The diversity of cacti in the country is closely related to the environmental conditions of tropical dry forests, which favour the presence of species adapted to aridity and nutrient-poor soils [56], as well as being ecosystems with endemic importance and floristic turnover. In Wayúu culture, Yosú, also known by its scientific name Stenocereus griseus, is valued as an important plant. This species of cactus is distributed in Colombia in departments such as La Guajira, Cesar and Magdalena, as well as in areas such as the Tatacoa Desert, the Chicamocha Canyon, the upper Magdalena River valley and Cúcuta. The Wayúu use the forest biomass of these cacti, derived from the plant’s xylem or ‘Yotojoro,’ as raw material for building homes. They also use this plant as food for both their ranches and their animals [42].

In Colombia, one of the ancestral uses of cacti has been to purify water. This has attracted the attention of researchers, who have found that cacti can serve as coagulants in the water purification process [57]. It has also been shown that the mucilage of different cactus species is rich in polysaccharides and minerals such as Ca (calcium), Mg (magnesium), Na (sodium), C (carbon), H (hydrogen), O (oxygen), N (nitrogen), and S (sulphur), as well as sugars such as arabinose, galactose, rhamnose, and xylose, which increases their potential for use in the manufacture of bioproducts [57].

In Colombia, various studies have shown that it is possible to produce biogas for electricity generation from the Opuntia ficus-indica cactus, using its biomass in anaerobic digestion processes. The use of this species is particularly attractive, as its costs are lower than other types of biomasses due to its high resistance to extreme temperatures, its tolerance to drought and its rapid growth [58].

In the Colombian department of La Guajira, arid and semi-arid ecosystems predominate, where cacti are among the most dominant species, especially in the northern (Alta Guajira) region. According to [58], xerophytic species occupy approximately 7–10% of the departmental territory, corresponding to 160,000–230,000 ha, of which cacti represent on average 15–30% of the total above-ground biomass. The biomass density of cacti varies widely across the department, ranging between 2 and 10 t·ha−1, depending on soil type, rainfall, and altitude [58]; the LHV of cactus biomass ranges from 14 to 18 MJ·kg−1.

Considering environmental sustainability, only 10–15% of the total standing biomass can be feasibly harvested each year without compromising the regeneration of vegetation and soil stability.

The theoretical energy potential was calculated as

where represents the estimated harvestable (sustainable) biomass. Usable energy was obtained by applying an average conversion efficiency of 30%, accounting for transformation losses. The results are summarised in Table 10.

Table 10.

Calculations of the energy potential of cacti in La Guajira.

The results indicate that the standing biomass of cacti may range from 0.32 to 1.6 million t of dry matter, depending on local density and coverage. Assuming a 10% sustainable extraction rate, the usable biomass varies between 32,000 and 160,000 t·yr−1, which corresponds to a theoretical energy potential between 124 and 800 GWh·yr−1. Although cacti represent a reliable renewable biomass source, their exploitation must be limited by ecological constraints, given their essential role in soil protection, erosion control, and biodiversity conservation in arid zones. Therefore, only a small fraction of the total stock should be considered for energy or bioproduct applications, prioritising circular and low-impact uses, such as biogas, biocarbon, and sustainable materials.

4.4. Saltwater: Energy Potential and Access to Water Resources for Communities

Colombia has a vast marine territory that represents approximately 50% of its total area, with nearly 2,070,408 km2 of territorial waters distributed between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean [59]; Ten Colombian departments have direct access to the sea: in the Caribbean, Atlántico, Bolívar, Sucre, Córdoba, Magdalena, La Guajira, and San Andrés y Providencia; in the Pacific, Chocó, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, and Nariño. The Caribbean coast is characterised by warmer waters, lower rainfall and higher population density and tourism development, while the Pacific is known for its high biodiversity, higher rainfall and a predominantly Afro-descendant and indigenous population, with lower economic development and greater isolation. Access to these marine resources provides key benefits such as food, oxygen, medicine, protection against coastal erosion and recreational opportunities, as well as being fundamental to biodiversity conservation and the country’s sustainable development [59].

In terms of energy potential, Colombia’s resources are concentrated in La Guajira, where high solar radiation favours the integration of photovoltaic systems with desalination plants. Research has shown that hybrid energy schemes can significantly reduce energy consumption and improve sustainability, guaranteeing access to drinking water in isolated communities [13]. The optimal sizing of desalination plants powered by renewable energy depends on high-resolution climate information. In this regard, the use of models such as ERA5-Land has made it possible to configure systems with more than 98% renewable energy input, strengthening the territory’s water and energy security [60]. This can symbolise technical and economic opportunities for indigenous communities, where cosmology is integrated and energy and water access models in the region are intensified, which is essential for promoting quality of life and the fulfilment of sustainable development goals such as 6 access to clean water and sanitation and 7 affordable and non-polluting energy in the coastal and rural communities of La Guajira, Colombia, which currently face great pressures regarding access to drinking water and energy [13].

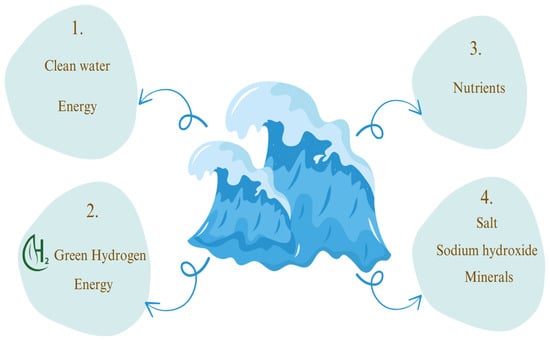

In addition to access to drinking water and energy generation through reverse osmosis processes, it is possible to further enhance the value of marine resources (see Figure 8). When reverse osmosis is integrated with renewable energies such as offshore wind or solar panels, not only is the production of desalinated water facilitated, but the opportunity to obtain green hydrogen from the electrolysis of treated water is also opened up, contributing to the sustainable energy transition [61]. The process also generates concentrated brine, which can be used to produce compounds such as sodium hydroxide and to recover valuable salts and minerals [62]. In addition, reverse osmosis and associated hybrid technologies enable the recovery and concentration of essential nutrients present in seawater, such as nitrates, phosphates, silicates and iron, which are fundamental to agriculture, aquaculture and the chemical industry [63].

Figure 8.

Products obtained from salt water (1) through reverse osmosis, (2) through electrolysis of treated water, temperature gradient, salinity gradient, ocean currents, (3) through hybrid technologies, (4) brine processing. Source: Authors.

4.5. Coastal Winds and Solar Radiation

Air and sunlight are resources available across the entire surface of the Earth. However, there are specific areas of the planet where these resources are much more abundant and have specific properties or behaviours that have shown it is possible to harness them to obtain energy. Solar energy basically refers to harnessing the sun’s radiation to generate electricity (photovoltaic) or heat (solar thermal). In a photovoltaic system, panels convert photons into electrical current using semiconductor materials (e.g., silicon). Efficiency depends on irradiation, angle, temperature, and losses (shading, dirt). On the other hand, wind energy is based on capturing the kinetic energy of the wind with turbines that convert that energy into electricity.

The geographical and climatic conditions in La Guajira have contributed to the region being identified as one of the areas with the highest solar radiation potential in the country. Research based on IDEAM meteorological records and atmospheric transmissibility models has reported average total radiation values of around 6.3 kWh·m−2·d−1, which makes the implementation of photovoltaic and thermal technologies viable [64]. Other analyses of historical series between 1993 and 2013 confirm the high availability of direct, diffuse and global radiation in the region, highlighting La Guajira’s climatic advantage over other departments in the Colombian Caribbean [65]. Similarly, recent geospatial assessments reinforce that La Guajira has one of the highest values of global solar radiation in the entire Caribbean region, making it a strategic location for renewable energy projects [65,66].

Recent initiatives in La Guajira already demonstrate tangible progress in the integration of coastal renewable resources. Solar-powered desalination systems have improved water access in remote Wayúu communities, showing technical feasibility and high social acceptance [13,60]. Likewise, small-scale cactus-based biogas projects have proven economically viable under arid conditions, with reported advantages in operational costs and drought resilience [58]. In terms of marine biomass, community-led clean-up programmes in nearby Caribbean locations have shown that sargassum collection can generate temporary employment and reduce environmental impacts linked to coastal accumulation [52,53]. These early successes illustrate the emerging technical, economic, and social benefits associated with resource valorisation in La Guajira, reinforcing the relevance of the pathways discussed in this review.

5. Comparative Discussion of the Impact on Energy Carrier Products in La Guajira

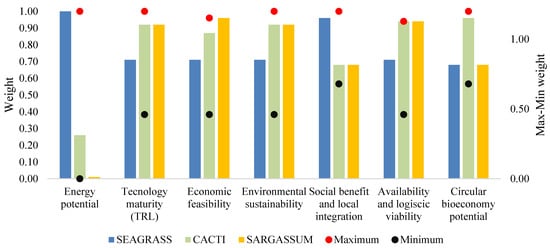

To compare the energy potential and sustainability of the coastal marine biomass analysed (seagrass, sargassum and cactus), a multi-criteria analysis was applied using DEFINITE 3.1 software (demo). Seven criteria were defined, integrating technical, environmental, economic and social dimensions, selected based on the bibliographic analysis and the quantitative results presented in this section. The criteria are detailed in Table 11, where the values assigned to each criterion can be seen by type of biomass. In addition, two options were added, one with the minimum ranges considered and the other with the maximum ranges considered.

Table 11.

Evaluation criteria data, biomass alternatives and ranges to be evaluated in Definite 3.1. The different types of criteria used in the multi-criteria analysis were defined based on the information previously researched and analysed in this article, as well as on complementary references, including [65].

The criterion of “energy potential” was included with the aim of quantitatively comparing the capacity of each biomass to contribute to renewable energy production. It should be noted that for sea ducks, the energy potential was initially calculated considering the area of seagrass beds, as there is no quantified data on how much seagrass biomass arrived on the Guajira coast in a year. The TRL criterion reflects the state of development and applicability of the technologies associated with each biomass, representing the feasibility of implementing future utilisation processes in the region. Economic feasibility was considered based on how easy it is for the region’s inhabitants to collect in terms of cost. This criterion was evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = lowest feasibility, 2 = medium-low feasibility, 3 = medium feasibility, 4 = medium-high feasibility, and 5 = high feasibility. For seagrass, the value of medium feasibility was taken, since fishermen could easily obtain seagrass biomass not only from the amount that reaches the coast, but also in a controlled manner and, to a lesser extent, from some of the seagrass beds. For sargassum, the highest value was taken, since during periods when sargassum arrives, the population could not only collect sargassum from the coast, but fishermen or boatmen could also collect the resource from our Colombian maritime territory in the Caribbean Sea, where it has been shown that immense quantities of sargassum arrive. For cactus, the value of medium-high feasibility was taken, since the population not only has to collect it, but also reforest it with more cactus or grow cactus crops. In addition, as they are distributed throughout the territory, they are easy to access, but it is necessary to take care of the species. Environmental sustainability assessed the degree of ecological impact and the need for conservation of the resource and was evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5, in the same way as economic feasibility. Seagrasses are the most vulnerable species and were given a medium-high value of 4, given their high ecological sensitivity and the need for protective measures. Sargassum was given a score of 3, as it is a highly available but seasonal resource; and cacti were given a value of 3, as they require extraction control to prevent deterioration of the arid ecosystem. The criterion of “social benefit and local integration” was also evaluated from 1 to 5. Seagrass was given a value of 3 due to the ecological restrictions associated with its use; sargassum and cacti achieved the maximum value of 5, as they offer sustainable production opportunities and are linked to local knowledge, coastal tourism and traditional practices. The criterion of “availability and logistical feasibility” was evaluated on a scale of 1 to 5, as in the previous cases. Seagrass was given a value of 2, as it is not widely available or accessible. Sargassum and cacti were given a value of 5, as they are highly feasible and accessible. The criterion of “circular bioeconomy potential” reflected the possibility of diversifying biomass-derived products beyond energy. Seagrass and sargassum were given a value of 5 for their proven ability to produce bioplastics, biofertilisers, and cosmetics, and cacti were given a value of 4 for their proven potential in obtaining biogas, filters and biopolymers, although with less reported technological diversity.

The Energy potential variable was introduced as a ratio (GWh·yr−1) and calculated from the available dry biomass and its LHV, applying a 30% conversion efficiency to represent typical energy recovery losses. The TRL criterion (C2) was coded on the standard 1–9 scale, while the remaining qualitative criteria were established on an ordinal 1–5 scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high). The input values were derived directly from the quantitative results and sustainability assumptions previously described.

All benefit-type criteria were normalised using the maximum method, ensuring that the best-performing option for each criterion received a standardised value of 1 [67]. The aggregation of criteria was performed through the WLC approach, which allows the integration of heterogeneous quantitative and qualitative indicators under a unified decision-making framework.

The assignment of weights was carried out through a combination of expert judgement, literature review, and the sustainability priorities identified for the region of La Guajira. In line with the integrated bioeconomy framework adopted in this study, environmental and social dimensions were prioritised to reflect the ecological sensitivity of coastal ecosystems and the dependence of local livelihoods on sustainable resource management. Consequently, the following weighting scheme was applied:

- Energy potential: 20%—representing the quantitative contribution of each biomass to renewable energy generation.

- Technological readiness level (TRL): 10%—reflecting the current stage of technological maturity for biomass conversion processes.

- Environmental sustainability: 20%—emphasising the ecological integrity and long-term resilience of each biomass resource.

- Economic feasibility: 15%—accounting for cost-efficiency and ease of implementation for local communities.

- Social benefit and local integration: 15%—highlighting the relevance of social inclusion, employment potential, and community well-being.

- Availability and logistic viability: 10%—capturing accessibility, transport feasibility, and resource stability throughout the year.

- Circular bioeconomy potential: 10%—integrating the capacity of each biomass to generate multiple value-added products beyond energy.

This weighting configuration aligns with sustainability-oriented decision-making approaches used in recent MCA studies on bioresource management [65], ensuring a balanced representation of environmental, economic, and social perspectives.

The MCA results are presented in Figure 9, which show the normalised performance radar by criterion and the contribution of each criterion to the final score. The multi-criteria analysis shows that, in terms of potential energy, seagrass has greater energy potential than cactus and sargassum (due to its high capacity to act as a carbon sink), although cactus ranks second in terms of potential. Technological maturity is almost the same for all three options, with seagrass slightly lower. In terms of economic feasibility, sargassum has the greatest potential as it is very easy to access, along with cactus. However, this would require the population to collect sargassum during the arrival season and not only limit themselves to the Guajira coast but also venture out to sea to collect surface sargassum from the Caribbean Sea. In terms of environmental sustainability, seagrass is the most vulnerable species and therefore the one that needs the most care, as it does not always wash up on the coast in large quantities and seagrass meadows are fundamental ecosystems for climate change mitigation. For this reason, it is the least sustainable in terms of environmental sustainability. Cacti and sargassum can be more easily controlled in terms of their ecosystem renewal and collection, which is why they are higher. In terms of social benefits and local integration, all three alternatives could be well accepted if the worldview of the cultures inhabiting the region is respected and integrated. In terms of logistics and access to resources, cactus and sargassum biomass are the most accessible and controllable. In terms of circular economic potential, all three alternatives fulfil this purpose. However, given the large quantities of sargassum that reach the coast and the Caribbean Sea, this has the greatest potential for circular economic use, together with the sargassum that arrives on the Guajira coast. The multi-criteria analysis shows that all three alternatives are good, but the most fragile and vulnerable is seagrass, which, although it is the biomass with the greatest energy potential if the entire area of the meadows is considered, is not as viable for total use. This is followed by cacti, which, as they are distributed throughout the territory and must be cultivated, may be somewhat vulnerable as a species. However, in terms of energy, they could be the best option, followed finally by sargassum, which, although it does not have great energy potential, is the most accessible and least vulnerable.

Figure 9.

Multi-criteria analysis results for each raw material. Source: Authors.

A key limitation of this study is the heterogeneity of the available data, particularly regarding the physicochemical characterisation of pelagic Sargassum and xerophytic biomass in arid environments. Much of the evidence derives from studies conducted in other Caribbean islands or from non-standardised measurements, which restricts direct comparability. Furthermore, the scarcity of long-term monitoring in La Guajira limits the capacity to assess interannual variability and biomass predictability. As a narrative review, the analysis synthesises qualitative and quantitative findings but does not perform a meta-analytical integration, which should be addressed in future research.

Throughout this review, it has been indirectly demonstrated that coastal resources represent enormous energy potential. Coastal areas such as La Guajira can be considered ‘natural energy laboratories,’ representing wealth in biomass and constant energy flow resources (wind, waves, and sun). In terms of biomass, sargassum, microalgae and fishing waste are raw materials that can be used to obtain energy carriers. In the case of seaweed, it has the advantage of not competing with agricultural land or fresh water, but the disadvantage of being costly to cultivate, harvest and dry, which is required to obtain value-added products. On the other hand, sargassum and other macroalgae represent an environmental problem due to their accumulation on beaches, which makes their use interesting. In the case of fishing and aquaculture waste, products such as oils and proteins available there can be key platforms for obtaining biodiesel, biogas, and other bioproducts. Coastal areas such as La Guajira are considered hotspots for photovoltaic and wind energy. Offshore wind power is booming in Europe, and in Colombia, the Caribbean has one of the greatest potentials in Latin America. This indicates the enormous potential of these resources to guarantee the permanent availability of clean energy. Finally, in terms of the saltwater available in the area, several interesting potentials can be identified: (i) the salt gradient, which integrates saltwater and freshwater to release energy, although this technology is still under development; (ii) the movement of the sea generates quite useful and available energy, despite its economic limitations; and (iii) coastal green hydrogen obtained from solar and wind electricity to electrolyse seawater, either desalinated or directly. The latter potential is currently one of the most recent.

From a socioeconomic perspective, the valorisation of coastal biomass offers opportunities to diversify local livelihoods, particularly in rural Wayúu communities where economic activities are limited. Small-scale bioproduct chains could generate decentralised income streams and reduce dependence on external fuels. However, these benefits require reliable biomass collection logistics, labour training and fair value-distribution mechanisms, without which biomass exploitation could reproduce existing inequalities. At the policy level, the findings underscore the need to align coastal biomass utilisation with Colombia’s broader energy-transition agenda. Although the national policy framework recognises bioenergy as a complementary resource, specific regulatory guidelines for marine biomass management, environmental handling and techno-economic feasibility assessments remain limited. Integrating Sargassum and xerophytic biomass into regional energy-planning instruments could foster investment certainty and promote hybrid systems combining bioenergy, solar, and wind resources in La Guajira.

Coastal biomass valorisation also has potential implications for community development. Collecting and pre-processing Sargassum or cactus residues could strengthen local cooperatives, support women-led entrepreneurship, and create educational opportunities linked to environmental stewardship. Ensuring that technology deployment respects Wayúu governance structures and cultural practices is essential to avoid top-down interventions and to promote long-term social acceptance.

The impact of the potential for each of the resources mentioned can be discussed in Table 12. In economic terms, the most mature technologies are solar, wind, the use of organic waste through anaerobic digestion, and waste oil conversions. In turn, the routes and innovations with the most R&D are those involving the use of macroalgae for biofuels, the saline gradient, and direct seawater electrolysis. The latter require full-scale pilots to sustainably assess their impact and applicability. In economic terms, technologies such as offshore wind and large-scale green hydrogen require high initial investments. Although Colombia, and especially the La Guajira region, has favourable resources for the implementation of these technologies, there are still regulatory barriers that somewhat delay progress in the development of these innovations. However, technologies involving the use of sargassum as waste and fishing waste have lower CAPEX and cross-cutting benefits in other areas. In environmental and social terms, integrating solutions to the problem of sargassum accumulation can be environmentally beneficial if dumping is prevented and pollution is controlled. But to truly identify whether these solutions are truly positive, it is necessary to incorporate environmental impact assessments alongside prior consultation processes with coastal communities (which in the case of La Guajira are indigenous).

Table 12.

Main technical, economic, and socio-environmental impacts of coastal resource exploitation.

The use of coastal biomass can contribute to climate-change adaptation strategies in arid coastal regions. Sargassum arrivals, although problematic, represent a recurrent and climate-driven biomass pulse that may be transformed into a resource rather than a waste burden. Similarly, drought-resistant xerophytic species offer resilient biomass options under increasing temperature and water scarcity. Integrating these resources within decentralised energy systems can strengthen energy security, reduce vulnerability to climatic shocks and support local adaptation pathways in La Guajira.

The results obtained for La Guajira are broadly consistent with findings reported in other coastal regions worldwide. For instance, studies in the Mediterranean and the Canary Islands have shown that macroalgal biomasses typically present high ash contents (20–40%) and moderate HHV values (10–15 MJ·kg−1), similar to the ranges observed for Sargassum in the Colombian Caribbean [79,80]. In Australia, research of beach-cast macroalgae along the Queensland coast reported compositional variability linked to salinity and seasonal upwelling, with bioenergy potentials [81] comparable to those found in La Guajira. Likewise, assessments of pelagic Sargassum in the Mexican Caribbean have documented high moisture and mineral content but favourable volatile matter percentages and biogas yields [82], reinforcing the suitability of coastal biomass for pre-treatment-based valorisation. These international comparisons confirm that the physicochemical behaviour of coastal biomass in La Guajira aligns with global patterns, while local environmental conditions—particularly aridity and persistent winds—shape distinctive opportunities for decentralised energy systems.

6. Policy and Research Implications

On the global stage, regulations on the use of coastal and marine resources have gradually advanced. There are international guidelines promoted by organisations such as the FAO and the European Union, which establish sustainability criteria for biofuel production and marine biomass management [3]. These standards not only seek to prevent impacts on biodiversity, but also to promote the responsible and traceable use of ecosystems. However, their application varies according to local contexts, and they often leave gaps when it comes to new technological approaches, such as integrated biorefineries or the use of sargassum and macroalgae for energy. In the case of Colombia, we do not yet have a specific policy regulating the use of marine biomass for energy or biotechnological purposes. However, there are regulatory frameworks that overlap and are applicable at different stages of the process [83]. For example, regulations on biofuels, aquaculture and environmental licences define conditions that all research must consider. This includes everything from scientific collection permits, established by the Ministry of the Environment, to procedures for accessing genetic resources or occupying maritime areas under DIMAR jurisdiction [2]. In other words, although there is no law ‘for algae,’ the regulatory ecosystem already imposes a framework for action for those who research or innovate in this field.

These regulations should not be interpreted as an obstacle, but rather as a compass. They remind us that all research involving natural resources, and especially coastal resources, has an unavoidable ethical and environmental dimension. In the case of marine biomass research, this means planning environmental monitoring protocols, traceability and, where necessary, consultation processes with local communities from the outset. Scientific research in highly ecologically and socially sensitive contexts such as La Guajira cannot be separated from environmental management and territorial dialogue. However, the implications are administrative or ethical.

Policies also guide the direction of science. They determine funding priorities, strategic areas for public funds and sustainability requirements [84]. In fact, Minciencias’ current emphasis on bioeconomy, blue economy, and energy transition shows a clear tendency to articulate research, technology, and regulation. Therefore, understanding the regulatory framework becomes a strategic act, because those who know the policy can anticipate its changes and take advantage of its opportunities.

Although a detailed energetic modelling exercise was beyond the scope of this review, the reported resource potentials can be loosely contextualised against regional energy demand. According to UPME’s statistical bulletin, La Guajira’s electricity consumption in 2023 amounted to 747.8 GWh·yr−1 (regulated) and 248.3 GWh·yr−1 (non-regulated) [85]. When compared with the annual solar irradiation of 2000–2300 kWh·m−2·yr−1 and the average wind power density exceeding 800 W·m−2 along the northern coast, the technical potential for decentralised renewable generation substantially surpasses current local demand. Likewise, seawater temperature gradients and marine currents, although still under-explored in Colombia, present niche opportunities for hybrid systems. These comparisons suggest that the coastal and marine resources assessed in this review could meaningfully contribute to local energy autonomy if supported by suitable infrastructure and governance frameworks.

7. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that La Guajira possesses an exceptional combination of coastal renewable resources whose complementarities strengthen the technical feasibility of hybrid solar–wind–biomass systems. The global overview and the multicriteria analysis consistently indicate that these resources, when strategically integrated, can provide stable energy generation while enabling the development of circular bioeconomy models tailored to arid and coastal territories. From a technical perspective, solar irradiation (>6 kWh·m−2·day−1) and coastal wind speeds (>8 m·s−1) position the region among the most favourable in the Caribbean for variable renewable energy deployment. Marine biomass streams exhibit physicochemical properties compatible with thermochemical and biochemical valorisation, while emerging biorefinery routes show increasing technological maturity (TRL 6–8). These synergies support the design of hybrid configurations capable of reducing intermittency and diversifying local energy portfolios.

Economically, biomass utilisation remains one of the most challenging pathways for energy deployment in La Guajira. Several techno-economic and review studies indicate that cultivation, harvesting, pre-treatment (e.g., drying or hydrothermal processes) and logistics are dominant cost drivers for macroalgal and coastal biomass value chains, often determining overall feasibility [79]. Optimisation studies and techno-economic assessments emphasise that co-processing and co-digestion strategies can improve yields and economics, but the benefits are strongly context-dependent [82]. Reviews of biomass supply costs and transport likewise highlight that feedstock logistics can represent a substantial portion of total production cost, especially for dispersed or beach-cast resources [86]. By contrast, recent IRENA analyses show that utility-scale solar PV and onshore wind have experienced rapid cost declines and, in many favourable locations, present substantially lower levelised costs than many biomass routes. Taken together, these sources suggest that while biomass valorisation offers important environmental and social co-benefits, its large-scale competitiveness as a primary electricity source requires careful site-specific techno-economic assessment, improvements in collection and pre-treatment logistics, and the capture of non-market co-benefits in policy instruments.

From an environmental and social perspective, the use of marine biomass such as Sargassum contributes to mitigating coastal degradation and reducing the negative effects of mass landings. These processes also enable local income generation, community involvement in resource management, and the creation of green jobs aligned with regional development priorities. The analysis shows that biomass options with high social integration achieve the highest scores in local benefit and circularity potential.

To strengthen future implementation, further work should incorporate site-specific techno-economic modelling, detailed cost–benefit assessments, and community-based governance strategies that ensure socially equitable and environmentally responsible development.

Author Contributions

R.F.C.-Q. participated in the review of the resources used, supervised the methodology and participated in the review of the manuscript. L.S.C.-M. and S.P.-R. participated in the construction of the original draft, and all the authors contributed to the overall supervision of the draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the program 948—2024 ORQUÍDEAS MUJERES EN LA CIENCIA, 502 within the research Project: “Estudio de las posibilidades del uso de biomasa endógena colombiana 503 en la producción de bio-productos a través de métodos termo- y electro-catalíticos” Code: 109361. In addition, this research was supported by CANTABRIA COOPERA project “Ciencia, Tecnología, Educación y Cultura hacia una Colombia sostenible e incluyente: biocombustibles a partir de residuos en una zona vulnerable” with UCC ID: INV4019-C.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the financial support given by the program 948—2024 ORQUÍDEAS MUJERES EN LA CIENCIA, within the research Project: “Estudio de las posibilidades del uso de biomasa endógena colombiana en la producción de bio-productos a través de métodos termo- y electro-catalíticos” Code: 109361, and the CANTABRIA COOPERA project “Ciencia, Tecnología, Educación y Cultura hacia una Colombia sostenible e incluyente: biocombustibles a partir de residuos en una zona vulnerable”, with UCC ID: INV4019-C.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Bio-SNG | Bio-Synthetic Natural Gas |

| CAM | Crassulacean Acid Metabolism |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditures |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DIMAR | Dirección de Marina Mercante Colombiana |

| DSWEL | Direct Seawater Electrolysis |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| GASB | Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| HTL | Hydrothermal Liquefaction |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| IDEAM | Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales |

| INVEMAR | Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| MCA | Multi-Criteria Analysis |

| MPA | Marine Protected Area |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OPEX | Operating Expenses |

| OTEC | Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SaWS | Sargassum Watch System |

| TEA | Techno-Economic Assessment |

| TRL | Technological Readiness Level |

| WLC | Weighted Linear Combination |

References

- Naciones Unidas. Objetivo 14: Conservar y Utilizar Sosteniblemente Los Océanos, Los Mares y Los Recursos Marinos. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/oceans/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras—INVEMAR. Lineamientos Técnicos Para el Aprovechamiento Sostenible de Macroalgas Marinas en Colombia. Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. 2022. Available online: https://www.invemar.org.co/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).