Techno-Economic Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Microgrids with Diesel Backup Generator: A Case Study in Industrial Loads in Germany Comparing Load-Following and Cycle-Charging Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Reliability and Cost Metrics

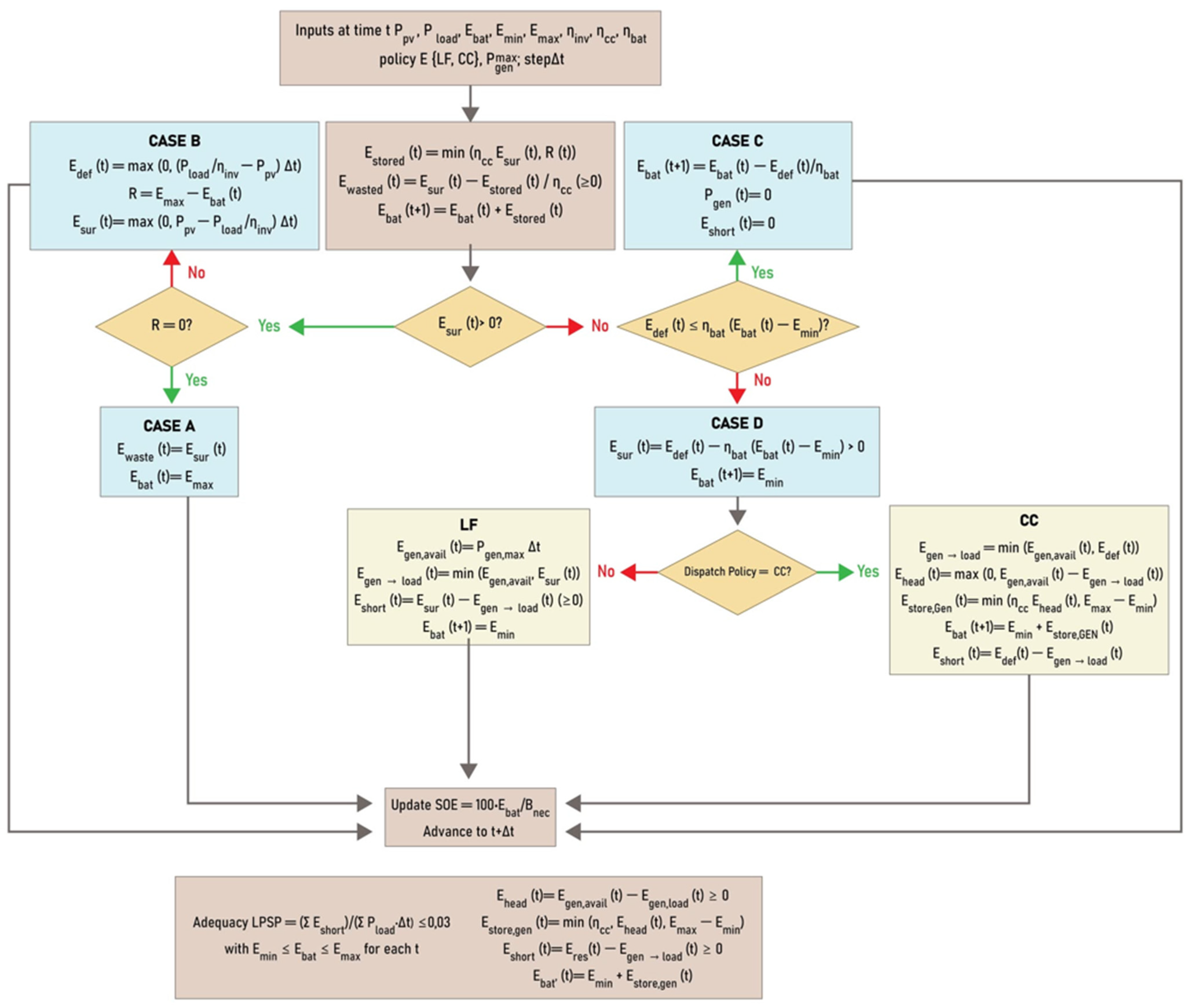

Dispatch Policies (Definitions)

- Load-Following (LF): A deficit-triggered policy in which the diesel generator (GEN) supplies only the residual demand that cannot be met by PV and the admissible battery window. When the usable battery energy is exhausted (i.e., Ebat → Emin), the GEN turns ON and does not charge the battery; it simply follows the residual load.

- Cycle-Charging (CC): A deficit-triggered policy in which, once the GEN is ON, it operates at (near) rated power to both cover the residual demand and charge the battery with any headroom up to Emax.

1.3. Related Work (Thematic Synthesis)

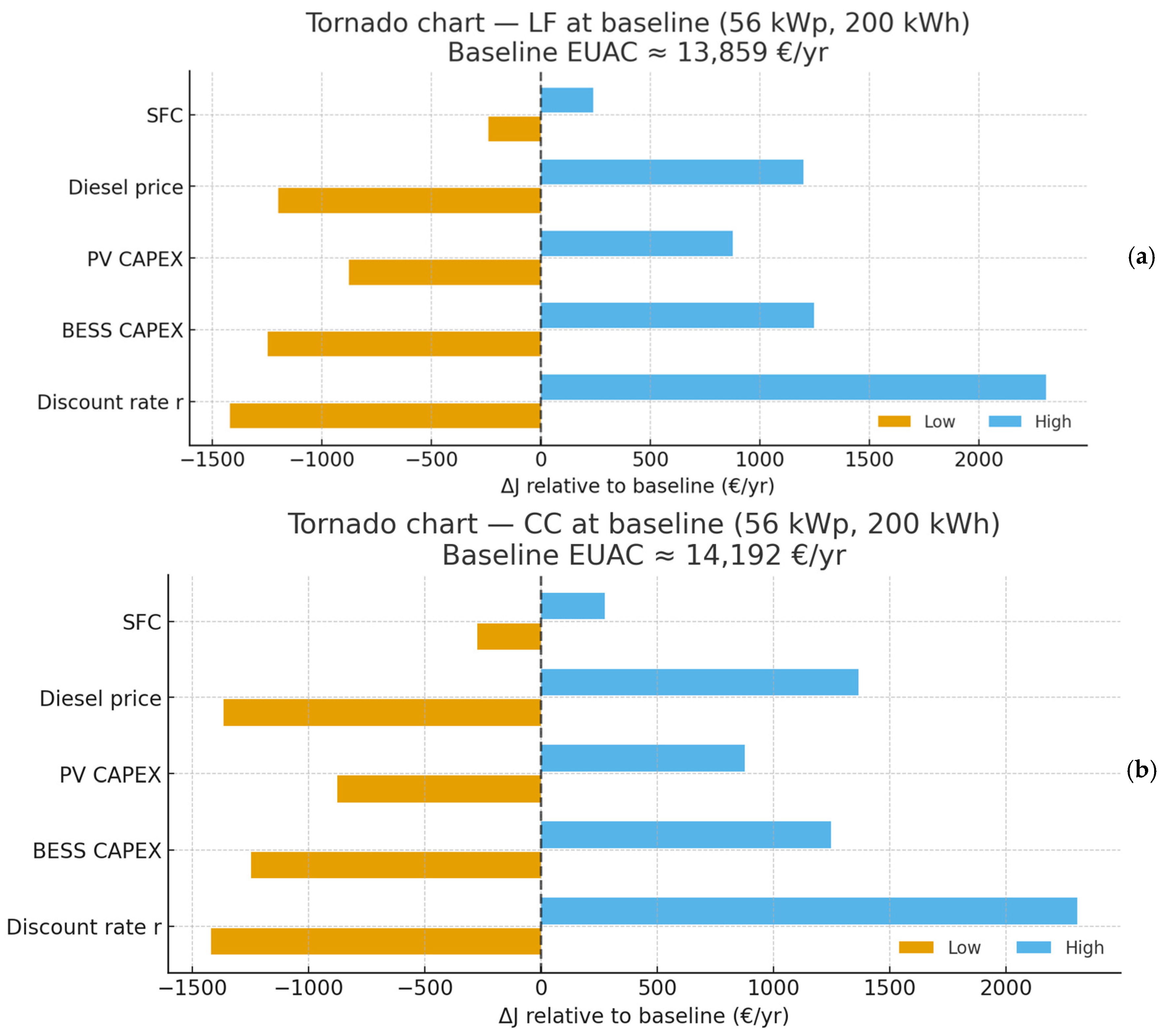

- Optimization practice. Meta-heuristics (e.g., GA/PSO) are widely used for capacity search, but transparent parametric sweeps on real time series remain highly interpretable and reproducible. Evidence across studies shows that battery and fuel cost assumptions are the dominant drivers of EUAC variance—hence our emphasis on battery cost/DoD/cycle life sensitivities [4,17,18,19]. Recent reviews also recommend embedding reliability directly in the objective, e.g., by including the deficit probability (LPSP) during optimization—precisely the stance adopted in our paper [17].

- Policy and sector coupling. Incorporating VOLL/curtailment penalties or carbon pricing moves the cost–reliability frontier and can justify larger PV/storage; flexible sinks (PtH, EV, H2) valorize surplus at fixed LPSP [8,20]. Because our summer curtailment is non-trivial, adding a PEM electrolyzer—well suited to fast RES ramps—would likely shift the EUAC minimum toward higher PV while keeping LPSP unchanged, in line with the synthesis of RES-to-H2 integration challenges in [21].

- Microgrid/DC sharing. Sharing/aggregation in DC microgrids reduces both LPSP and cost compared to isolated systems [22].

- Role separation PV vs. BESS (application evidence). In a stand-alone PV EV-charging use case, more PV primarily depresses daytime LPSP, while larger storage suppresses nighttime LPSP; this separation echoes our A/B/C/D case analysis and supports high-PV/moderate-storage pairings at lowest annualized cost [23].

1.4. Contributions and Novelty of This Work

1.5. Paper Organization

2. Materials and Methods

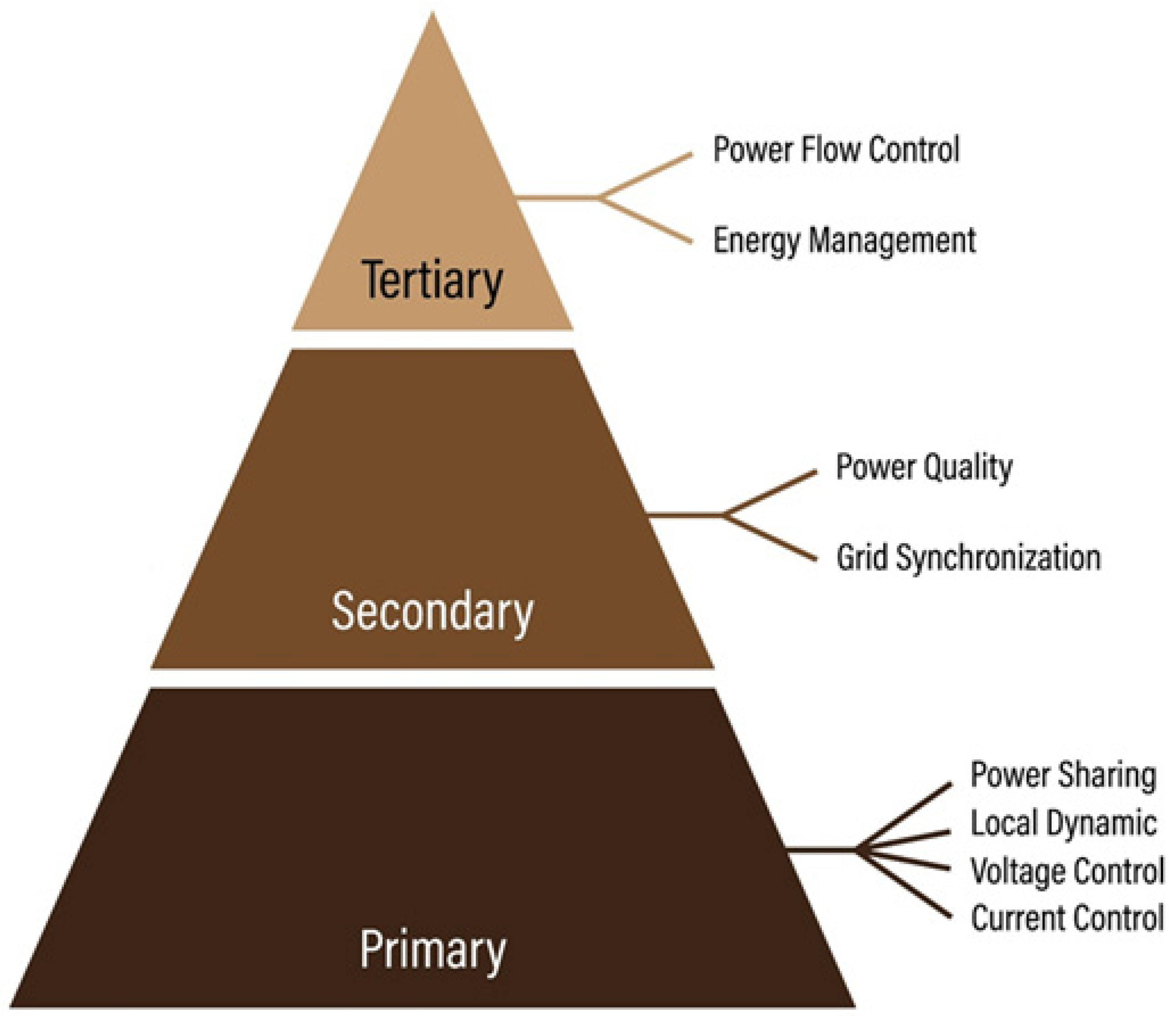

2.1. Microgrid Context and Control Scope

- Primary control (fast, local) governs current/voltage and droop characteristics of the grid-forming inverter and generator.

- Secondary control restores frequency/voltage and handles grid synchronization.

- Tertiary control (EMS) optimizes power flows over minutes–hours, i.e., dispatch and scheduling.

2.2. Analyzing the System’s Flowchart

2.3. Energy Production Estimation

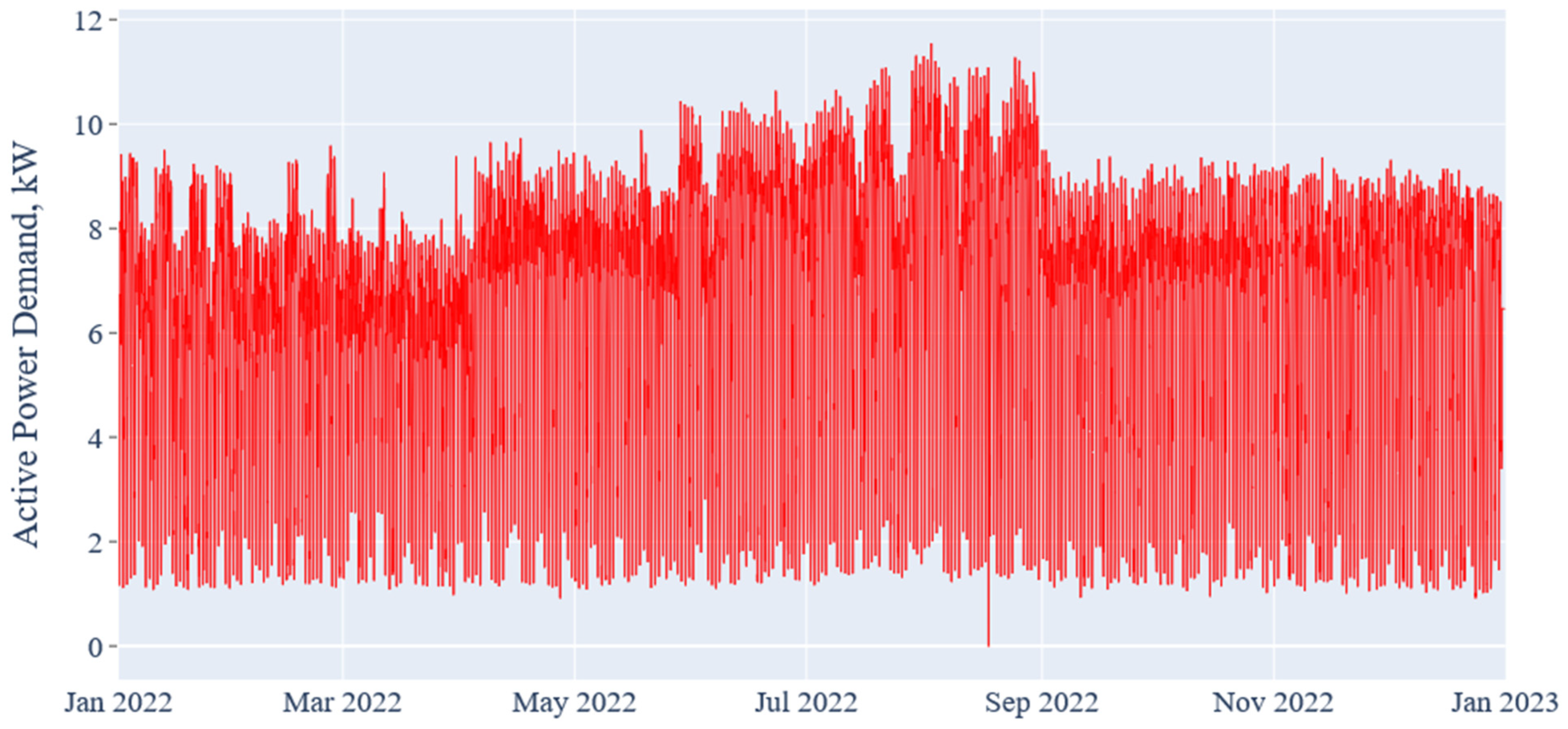

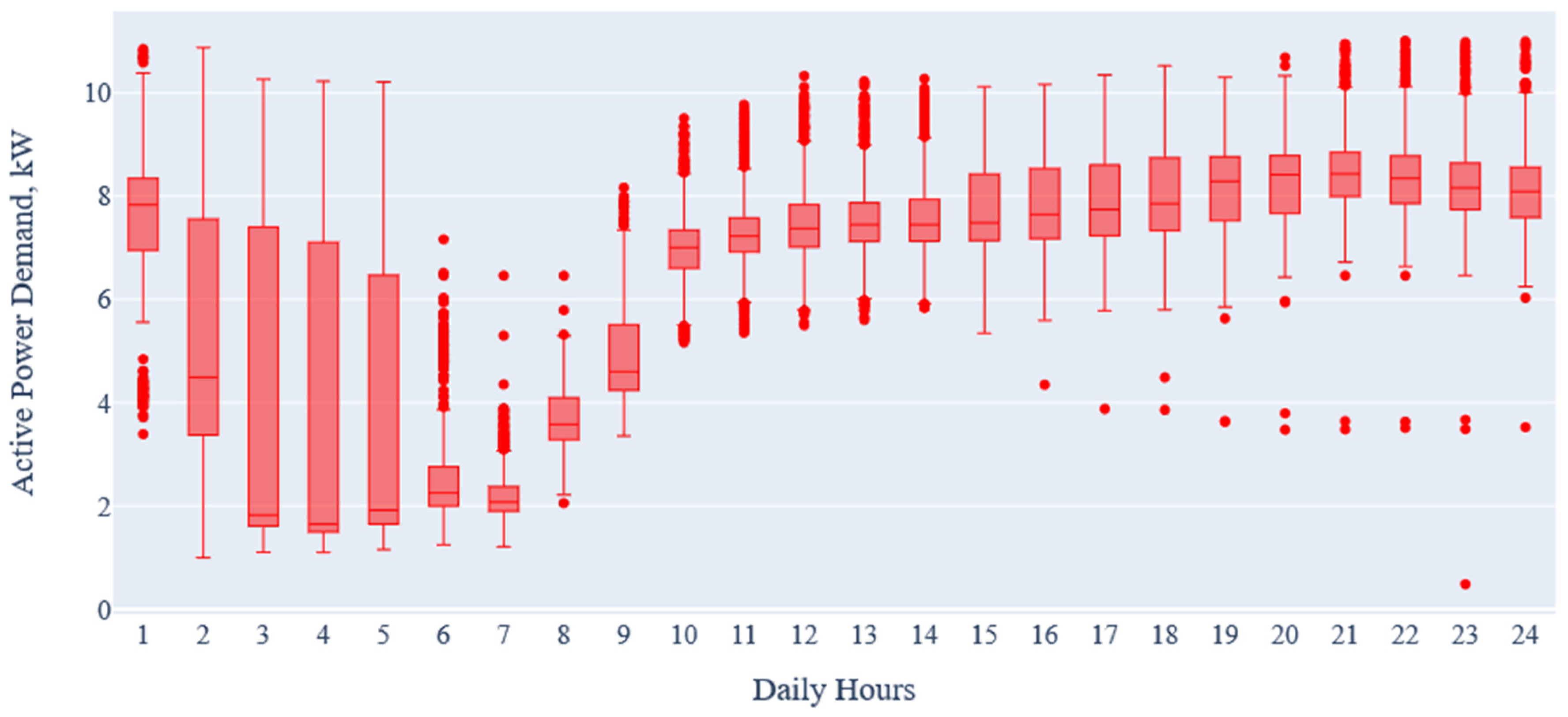

2.4. Analysis of Load Profiles

2.5. System’s Operation Algorithm

- : PV power on the DC bus after MPPT [kW].

- : AC load power [kW].

- : PV/GEN → battery charge efficiency (one-way).

- : battery discharge efficiency (one-way).

- : DC/AC inverter efficiency (one-way).

- : nominal battery energy [kWh].

- DoD∈(0,1]: admissible depth-of-discharge.

- .

- : battery energy state [kWh].

- : diesel generator rated power [kW] (12 kW).

- : Energy demand not met by the system.

- : Total energy demand.

2.6. Model Validation and Parameter Benchmarking

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interpretation of the SOE Profile over the Year

3.2. Seasonal Weekly Operation Under Load-Following and Cycle-Charging (Case A/B/C/D)

3.3. Techno-Economic Objective and Annualization

3.4. Synthesis of Optimization Objectives and Reliability Treatments in Microgrid Planning

3.5. Parametric Sizing Results: LPSP Feasibility and EUAC Minimum (DoD = 20–80%, GEN = 12 kW)

- DoD = 20%: no feasible point with LPSP ≤ 0.03 in the scanned grid, the usable window is too small to bridge deficits.

- DoD = 50%: a feasible band emerges: cost contours show a valley toward high PV and mid storage; increasing PV reduces deficits more “cheaply” than very large storage, while too much storage raises EU AC with limited additional benefit.

- DoD = 80%: the feasible region widens markedly; the larger usable energy window depresses LPSP without necessarily increasing battery EUAC (calendar life-limited). The cost valley shifts toward moderate storage at higher PV.

- The starred point at (Npv = 140 modules ≈ 56 kWp, Bnec = 200 kWh) lies just inside the feasible region—i.e., LPSP ≈ 0.025, comfortably ≤ 0.03. In this study, this starred point (56 kWp PV, 200 kWh BESS, DoD = 80%) is the chosen optimum used in all subsequent techno-economic and SoE analyses.

- The red vertical section at Npv = 140 (the “56 kWp cut”) shows the crossing of the target: at Bnec = 200 kWh we are already below 0.03; any smaller BESS would push the section above the 0.03 line (infeasible), while any larger BESS only reduces LPSP further without improving the constraint.

- Because adequacy is non-binding (LPSP ≈ 0) and generator energy at the optimum is modest, EUAC exhibits a shallow minimum near the smallest feasible capacities. Hence the cost-minimizing design lies close to the LPSP boundary, at Npv = 140 (56 kWp) and Bnec = 200 kWh.

- The LF vs. CC panels confirm this: under CC the 0.03 contour shifts slightly downward (marginal reliability gain), but at Npv = 140 both policies are already below 0.03 around Bnec ≈ 200 kWh. Thus, cost—not reliability—dominates the choice locally, so the same pair remains optimal (and CC merely keeps a slightly higher SoE after GEN-ON, as shown elsewhere).

3.6. Robustness of the Optimum and Generator-Sizing

4. Conclusions

- EV smart charging can be scheduled to align with PV production peaks or to support SoE recovery during low-storage periods. Bidirectional charging, vehicle-to-building (V2B) can also offer short-term peak shaving, effectively turning part of the mobility demand into controllable load.

- Power-to-heat (PtH), such as high-COP heat pumps or electric boilers coupled with thermal storage, can convert midday surplus into usable heat at low marginal cost, displacing fossil fuel-based heating and leading to near-zero curtailment during summer months. In broader applications, PtH concepts can also be integrated into district heating networks, where surplus PV electricity is converted into heat and distributed to multiple consumers via centralized systems. Such integration could further enhance renewable energy utilization, reduce fossil-based heating demand, and support local decarbonization targets.

- Hydrogen production via electrolysis acts as a deeper sink for extended surpluses (“power-to-molecules”), provided part-load and start–stop limitations of the electrolyzer are respected. The produced hydrogen can serve as on-site fuel or an exportable energy carrier.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LF | Load-Following |

| CC | Cycle-Charging |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| MG | Microgrid |

| SoE | State-of-Energy |

| DoD | Depth-of-Discharge |

| LPSP | Loss of Power Supply Probability |

| EUAC | Equivalent Annual Cost |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| VOLL | Value of Lost Load |

| SFC | Specific Fuel Consumption |

| GEN | Generator |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resource |

| LV | Low-Voltage |

| GHI | Global Horizontal Irradiance |

| PVGIS | Photovoltaic Geographical Information System |

| TMY | Typical Meteorological Year |

| PVBAT | Photovoltaic Battery System |

| SMEs | Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| Li | Lithium |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| PNNL | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

| IEA/NEA | International Energy Agency and Nuclear Energy Agency |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| PtH | Power-to-Heat |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| LCC | Life Cycle Cost |

| NPC | Net Present Cost |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| SAPS | Stand-Alone Power Systems |

| HRES | Hybrid Renewable Energy System |

| EENS | Expected Energy Not Served |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| MOEA | Multi Objective Evolutionary Algorithm |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| V2B | Vehicle-to-Building |

| COP | Coefficient of Performance |

Appendix A

References

- Ofry, E.; Braunstein, A. The loss of power supply probability as a technique for designing stand-alone solar electrical (photovoltaic) systems. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1983, 102, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzahr, I.; Ramakumar, R. Loss of Power Supply Probability of Stand-Alone Photovoltaic Systems: A Closed Form Solution Approach. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1991, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayop, R.; Mat Isa, N.; Tan, C.W. Components Sizing of Photovoltaic Stand-Alone System Based on Loss of Power Supply Probability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2731–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould Bilal, B.; Sambou, V.; Ndiaye, P.A.; Kébé, C.M.F.; Ndongo, M. Multi-objective design of PV–wind–batteries hybrid systems by minimizing the annualized cost system and the loss of power supply probability (LPSP). In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Cape Town, South Africa, 25–28 February 2013; pp. 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semassou, G.C.; Dai Tometin, A.D.D.V.; Ahouansou, R.; Chegnimonhan, K.V.; Guidi, T.C. Contribution to the Optimization of Autonomous Photovoltaic Solar Systems with Hybrid Storage for Loads with Peak Power under Volume and Loss-of-Power-Supply-Probability Constraints. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2020, 14, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhayo, B.A.; Al-Kayiem, H.H.; Gilani, S.I.U.; Khan, N.; Kumar, D. Energy management strategy of hybrid solar-hydro system with various probabilities of power supply loss. Sol. Energy 2022, 233, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, D.; Oriti, G. Rightsizing the Design of a Hybrid Microgrid. Energies 2021, 14, 4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Khan, H.A.; Anees, M.; Nasir, M. System Size and Loss of Power Supply Probability Reduction through Peer-to-Peer Power Sharing in DC Microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Houston, TX, USA, 6–8 April 2022; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyele, D.; Belikov, J.; Levron, Y. Challenges of Microgrids in Remote Communities: A STEEP Model Application. Energies 2018, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shezan, S.A.; Hasan, K.N.; Rahman, A.; Datta, M.; Datta, U. Selection of Appropriate Dispatch Strategies for Effective Planning and Operation of a Microgrid. Energies 2021, 14, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbal, M.J.B.; Moussa, S.; Ziani, J.A.; Slama-Belkhodja, I. A comparison study of two DC microgrid controls for a fast and stable DC bus voltage. Math. Comput. Simul. 2021, 184, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banguero, E.; Correcher, A.; Pérez-Navarro, Á.; Morant, F.; Aristizabal, A. A Review on Battery Charging and Discharging Control Strategies: Application to Renewable Energy Systems. Energies 2018, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, T.; Muhsen, D.H. Optimal Sizing of Standalone Photovoltaic System Using Improved Performance Model and Optimization Algorithm. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladigbolu, J.O.; Ramli, M.A.M.; Al-Turki, Y.A. Techno-Economic and Sensitivity Analyses for an Optimal Hybrid Power System Which Is Adaptable and Effective for Rural Electrification: A Case Study of Nigeria. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismail, F.S. DC Microgrid Planning, Operation, and Control: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36154–36172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D.; Illindala, M.S.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Z. Sizing battery storage for islanded microgrid systems to enhance robustness against attacks on energy sources. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2019, 7, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, A.; Blondin, M.; Trovão, J.P.F. A Review of Optimization Strategies for Energy Management in Microgrids. Energies 2025, 18, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazlan, M.; Sulaiman, S.I.; Azmi, A.; Zainuddin, H.; Musirin, I. Optimal sizing of stand-alone photovoltaic system by minimizing the loss of power supply probability using Meerkat optimization algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2025, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri Rad, M.A.; Ghasempour, R.; Rahdan, P.; Mousavi, S.; Arastounia, M. Techno-economic analysis of a hybrid power system based on the cost-effective hydrogen production method for rural electrification: A case study in Iran. Energy 2020, 190, 116421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, W.; Wang, K.; Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, P.; Xiao, G. Multi-objective optimization of operational strategy and capacity configuration for hybrid energy system combined with concentrated solar power plant. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.K.; Azad, A.K.; Rasul, M.G.; Doppalapudi, A.T. Prospect of Green Hydrogen Generation from Hybrid Renewable Energy Sources: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbes, D.; Martinez, A.; Champenois, G. Life Cycle Cost, Embodied Energy and Loss of Power Supply Probability for the Optimal Design of Hybrid Power Systems. Math. Comput. Simul. 2014, 98, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ghosh, A.; Lopez, N.S.A. Optimisation of a standalone photovoltaic electric vehicle charging station using the loss of power supply probability. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamulapati, T.; Cavus, M.; Odigwe, I.; Allahham, A.; Walker, S.; Giaouris, D. A Review of Microgrid Energy Management Strategies from the Energy Trilemma Perspective. Energies 2023, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Nagrial, M.; Rizk, J.; Hellany, A. General Aspects, Islanding Detection, and Energy Management in Microgrids: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, M.F.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Benbouzid, M. Microgrids Energy Management Systems: A Critical Review on Methods, Solutions, and Prospects. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Vera, Y.E.; Dufo-López, R.; Bernal-Agustín, J.L. Energy Management in Microgrids with Renewable Energy Sources: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, C.; Xu, R. A Review on Distributed Energy Resources and MicroGrid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2472–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikalakis, A.G.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Centralized control for optimizing microgrids operation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2008, 23, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-S.; Hassan, M.Y.; Majid, M.S.; Abdul Rahman, H. Optimal Distributed Renewable Generation Planning: A Review of Different Approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Shafiullah, M.; Ahmed, C.B.; Alowaifeer, M. A Review of Microgrid Energy Management and Control Strategies. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 21729–21757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milis, K.; Peremans, H.; Van Passel, S. The Impact of Policy on Microgrid Economics: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 3111–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Jirdehi, M.; Sohrabi Tabar, V.; Ghassemzadeh, S.; Tohidi, S. Different Aspects of Microgrid Management: A Comprehensive Review. J. Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, F.; Bayram, I.S. Planning, Operation, and Protection of Microgrids: An Overview. Energy Procedia 2017, 107, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgholian, G. A Brief Review on Microgrids: Operation, Applications, Modeling, and Control. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, e12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebra, E.I.C.; van der Windt, H.J.; Nhumaio, G.; Faaij, A.P.C. A Review of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems in Mini-Grids for Off-Grid Electrification in Developing Countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 111036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayar, M.E. Rural Electrification and Expansion Planning of Off-Grid Microgrids. Electr. J. 2017, 30, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Ren, Y.; Luan, H.; Dong, R.; Wang, X.; Liao, J.; Fang, S.; Gao, K. A Review of Optimization for System Reliability of Microgrid. Mathematics 2023, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaee, M.; Radzi, M. Multi-objective optimization of a stand-alone hybrid renewable energy system by using evolutionary algorithms: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3364–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G.; Lamb, J.J.; Burheim, O.S.; Austbø, B. Review of Energy Storage and Energy Management System Control Strategies in Microgrids. Energies 2021, 14, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Dimeas, A.; Tsikalakis, A. Centralized and decentralized control of microgrids. Int. J. Distrib. Energy Resour. 2005, 1, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Haider, Z.M.; Malik, F.H.; Almasoudi, F.M.; Alatawi, K.S.S.; Bhutta, M.S. A Comprehensive Review of Microgrid Energy Management Strategies Considering Electric Vehicles, Energy Storage Systems, and AI Techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.E.; Mehrizi-Sani, A.; Etemadi, A.H.; Cañizares, C.A.; Iravani, R.; Kazerani, M.; Hajimiragha, A.H.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O.; Saeedifard, M.; Palma-Behnke, R.; et al. Trends in Microgrid Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Jia, P.; Yue, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, M. Distributed Optimal Control of DC Network Using Convex Relaxation Techniques. Energies 2024, 17, 6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Jin, P.; Hatziargyriou, N.D.; Chang, L. Multiagent-based hybrid energy management system for microgrids. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Miao, H.; Li, J.; Yang, L. Voltage control and power sharing in DC Microgrids based on voltage-shifting and droop slope-adjusting strategy. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 214, 108814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Kamel, R.M.; Andoulsi, R.; Nagasaka, K. Multiobjective intelligent energy management for a microgrid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 60, 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Qin, B.; Guo, L. Coordinated control of wind turbine and hybrid energy storage system based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for wind power smoothing. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmehr, N.; Najafi-Ravadanegh, S. Optimal Operation of Distributed Generations in Micro-Grids under Uncertainties in Load and Renewable Power Generation Using Heuristic Algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2015, 9, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žigman, D.; Tomiša, T.; Osman, K. Methodology Presentation for the Configuration Optimization of Hybrid Electrical Energy Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Bazmohammadi, N.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. Multiple Microgrids: A Review of Architectures and Operation and Control Strategies. Energies 2023, 16, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boche, A.; Foucher, C.; Villa, L.F.L. Understanding Microgrid Sustainability: A Systemic and Comprehensive Review. Energies 2022, 15, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.E.; Canizares, C.A.; Kazerani, M. A Centralized Energy Management System for Isolated Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1864–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Urmee, T.; Calais, M.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Carter, C. Technical challenges of PV deployment into remote Australian electricity networks: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 1309–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ning, X.; Yang, P.; Xu, L. Review of Power Sharing, Voltage Restoration and Stabilization Techniques in Hierarchical Controlled DC Microgrids. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 149202–149223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, R.; Kollimalla, S.K.; Mishra, M.K. Dynamic energy management of micro grids using battery super capacitor combined storage. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual IEEE India Conference (INDICON), Kochi, India, 7–9 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, C.N.; Zountouridou, E.I.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Review of hierarchical control in DC microgrids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2015, 122, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Buitrago, S.F.; Maya-Duque, P.; Villa-Acevedo, W.M.; Muñoz-Galeano, N.; López-Lezama, J.M. Enhancing Energy Microgrid Sizing: A Multiyear Optimization Approach with Uncertainty Considerations for Optimal Design. Algorithms 2025, 18, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragičević, T.; Lu, X.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. DC Microgrids-Part II: A Review of Power Architectures, Applications, and Standardization Issues. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 3528–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.; Coelho, E.A.A.; Guerrero, J.M. MAS-Based Distributed Coordinated Control and Optimization in Microgrid and Microgrid Clusters: A Comprehensive Overview. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 6488–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogou, C.; Ipsakis, D.; Elmasides, C.; Stergiopoulos, F.; Papadopoulou, S.; Seferlis, P.; Voutetakis, S. Automation Infrastructure and Operation Control Strategy in a Stand-Alone Power System Based on Renewable Energy Sources. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 9488–9499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasides, C.; Kosmadakis, I.E.; Athanasiou, C. A Comprehensive Power Management Strategy for the Effective Sizing of a PV Hybrid Renewable Energy System with Battery and H2; Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 106, 114790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentzis, K.; Karapidakis, E.; Tsikalakis, A. Cost Analysis of Demand-Side Generating Assets Contribution to Ancillary Services of Island Power Systems. Inventions 2020, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraeini, M.; Javidi, M.H.; Ghazizadeh, M.S. Comparison between communication infrastructures of centralized and decentralized wide area measurement systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Dragicevic, T.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M.; Perez, J.R. Modeling and sensitivity analysis of consensus algorithm based distributed hierarchical control for DC microgrids. In Proceedings of the IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition-APEC, Charlotte, NC, USA, 15–19 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmadakis, I.E.; Elmasides, C. A Sizing Method for PV–Battery–Generator Systems for Off-Grid Applications Based on the LCOE. Energies 2021, 14, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Mishra, S.; Fazeli, S.M.; Li, F.; Dragičević, T. A Distributed fixed-Time secondary controller for dc microgrid clusters. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 34, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, H.E.; Saied, E.M.; Malik, O.P.; Bendary, F.M.; Ali, A.A. Fuzzy PI controller-based model reference adaptive control for voltage control of two connected microgrids. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolino, G.M.; Fusco, G.; Russo, M. A Distributed Cooperative Anti-Windup Algorithm Improving Voltage Profile in Distribution Systems with DERs’ Reactive Power Saturation. Energies 2025, 18, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamp, F.; Ciufo, P. A Sensitivity analysis toolkit for the simplification of MV distribution network voltage management. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Souza, A.C.M.; Vasconcelos, A.; Rode, A.C.; Filho, R.D.; Marinho, M.H.N. Comparing the Financial and Environmental Impact of Battery Energy Storage Systems and Diesel Generators on Microgrids. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.D.; Silva, J.F.A.; Rocha, L. Virtual Generator to Replace Backup Diesel GenSets Using Backstepping Controlled NPC Multilevel Converter in Islanded Microgrids with Renewable Energy Sources. Electronics 2024, 13, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuer, F. Load profile data of 50 industrial plants in Germany for one year. Zenodo 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuer, F.; Rominger, J.; McKenna, R.; Fichtner, W. Battery Storage Systems: An Economic Model-Based Analysis of Parallel Revenue Streams and General Implications for Industry. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1424–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, A.; Rabeh, A.; Ali, D.M.; Mohamed, J. Multi-objective genetic algorithm based sizing optimization of a stand-alone wind/PV power supply system with enhanced battery/supercapacitor hybrid energy storage. Energy 2018, 163, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaf, S.; Notton, G.; Belhamel, M.; Haddadi, M.; Louche, A. Design and techno-economical optimization for hybrid PV/wind system under various meteorological conditions. Appl. Energy 2008, 85, 968–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamjoo, A.; Maheri, A.; Dizqah, A.M.; Putrus, G. Electrical power and energy systems multi-objective design under uncertainties of hybrid renewable energy system using NSGA-II and chance constrained programming. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 74, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, A.L.; Tan, C.W.; Lau, K.Y. Optimal Sizing of an Autonomous Photovoltaic/Wind/Battery/Diesel Generator Microgrid Using Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wei, Z.; Chengzhi, L. Optimal design and techno-economic analysis of a hybrid solar–wind power generation system. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.-H.; Abunima, H.; Glick, M.B.; Kim, Y.-S. Energy Curtailment Scheduling MILP Formulation for an Islanded Microgrid with High Penetration of Renewable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micangeli, A.; Del Citto, R.; Kiva, I.N.; Santori, S.G.; Gambino, V.; Kiplagat, J.; Viganò, D.; Fioriti, D.; Poli, D. Energy Production Analysis and Optimization of Mini-Grid in Remote Areas: The Case Study of Habaswein, Kenya. Energies 2017, 10, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC135034?mode=full&utm (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Available online: https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/2024/utility-scale_pv-plus-battery (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Friesen, G.; Micheli, L.; Eder, G.; Müller, T.; Ali, J.; Rivera Aguilar, M.; Ascencio-Vasquez, J.; Oreski, G.; Burnham, L.; Baldus-Jeursen, C.; et al. Optimisation of Photovoltaic Systems for Different Climates. In IEA PVPS Task 13: Reliability and Performance of Photovoltaic Systems; IEA PVPS: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongird, K.; Viswanathan, V.; Alam, J.; Vartanian, C.; Sprenkle, V.; Baxter, R. 2020 Grid Energy Storage Technology Cost and Performance Assessment. Energy 2020, 2020, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- PV Magazine USA. NREL Anticipates Rising Utility-Scale Costs, Decreasing Residential Costs. 6 November 2023. Available online: https://pv-magazine-usa.com/2023/11/06/nrel-anticipates-rising-utility-scale-costs-decreasing-residential-costs/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA); Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA). Projected Costs of Generating Electricity—2020 Edition; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) Calculator. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/levelised-cost-of-electricity-calculator?utm_ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Koholé, Y.W.; Ngouleu, C.A.W.; Fohagui, F.C.V.; Tchuen, G. Optimization and Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Sustainable and Clean Energy Production in Rural Cameroon Considering the Loss of Power Supply Probability Concept. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 25, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansa, I.; Villafafila, R.; Bellaaj, N.M. Optimal Sizing Design of an Isolated Microgrid Using Loss of Power Supply Probability. In Proceedings of the 2015 Sixth International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Sousse, Tunisia, 24–26 March 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaf, S.; Diaf, D.; Belhamel, M.; Haddadi, M.; Louche, A. A Methodology for Optimal Sizing of Autonomous Hybrid PV/Wind System. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5708–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroulis, E.; Kolokotsa, D.; Potirakis, A.; Kalaitzakis, K. Methodology for Optimal Sizing of Stand-Alone Photovoltaic/Wind-Generator Systems Using Genetic Algorithms. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lu, L.; Zhou, W. A Novel Optimization Sizing Model for Hybrid Solar–Wind Power Generation System. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patibandla, A.; Kollu, R.; Rayapudi, S.R.; Manyala, R.R. A Multi-Objective Approach for the Optimal Design of a Standalone Hybrid Renewable Energy System. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, e6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafando, J.G.; Yamegueu, D.; Houdji, E.T. Review on Sizing and Management of Stand-Alone PV/Wind Systems with Storage. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapen, P.T. Multi-Objective Optimization of a Wind/Photovoltaic/Battery Hybrid System Using a Novel Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 327, 119533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarso, A.K.; Jin, G.; Ahn, J. Hybrid Genetic Algorithm-Based Optimal Sizing of a PV–Wind–Diesel–Battery Microgrid: A Case Study for the ICT Center, Ethiopia. Mathematics 2025, 13, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, A.; Shahidehpour, M. Microgrid-Based Co-Optimization of Generation and Transmission Planning in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitompul, S.; Fujita, G. Impact of Advanced Load-Frequency Control on Optimal Size of Battery Energy Storage in Islanded Microgrid System. Energies 2021, 14, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufyan, M.; Abd Rahim, N.; Tan, C.K.; Muhammad, M.A.; Sheikh Raihan, S.R. Optimal Sizing and Energy Scheduling of Isolated Microgrid Considering the Battery Lifetime Degradation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M.; Nazari, M.H.; Hosseinian, S.H. Optimal Energy Management of Battery with High Wind Energy Penetration: A Comprehensive Linear Battery Degradation Cost Model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennassiri, Y.; de-Simón-Martín, M.; Bracco, S.; Robba, M. Energy Management System for Polygeneration Microgrids, Including Battery Degradation and Curtailment Costs. Sensors 2024, 24, 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marqusee, J.; Becker, W.; Ericson, S. Resilience and Economics of Microgrids with PV, Battery Storage, and Networked Diesel Generators. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 3, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivelnathan, N.; Arefi, A.; Lund, C.; Mehrizi-Sani, A.; Muyeen, S.M. Cost-Effective Reliability Level in 100% Renewables-Based Standalone Microgrids Considering Investment and Expected Energy Not Served Costs. Energy 2024, 311, 133426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Count | Mean | STD | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35,040 | 6.461 | 2.547 | 0.000 | 4.688 | 7.313 | 8.275 | 11.550 |

| Month | LF—Operation and SoE | CC—Operation and SoE | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | Short days, Case C windows compressed, long B at night, SoE often 20–35%, frequent GEN-ON clusters in overcast spells. | Same starts as LF but with D charging while GEN is ON, SoE exits events at ~40–55%, reducing time near Emin. | CC reduces deep excursions vs. LF, reliability respected. |

| February | Noon PV widens, night minima ~ 30%, GEN still needed but in shorter bursts. | Higher post-GEN SoE due to D, back-to-back starts less likely, trajectories otherwise similar to LF. | Convergence begins; CC gentler overnight posture. |

| March | Shoulder month: regular midday Case C plateaus (~60–80% SoE), gentler evening descents; GEN calls drop. | Fewer, longer starts, brief D segments consolidate charging and raise evening SoE. | CC further reduces cycling frequency. |

| April | Longer days, SoE commonly recovers to 70–90%, GEN sporadic. | Short D patches visible when GEN runs, lifting SoE post-event, policies nearly indistinguishable otherwise. | Weak policy difference under strong PV. |

| May | Abundant PV, noon often near full, night troughs 35–45%, Case A prevalent, GEN rare. | D almost disappears (few GEN starts); SoE high and stable. | PV dominance; dispatch choice immaterial. |

| June | Strong resource, clear saw-tooth, 90–100% plateaus, GEN virtually absent. | Operationally identical to LF, negligible D. | Summer reliability driven by PV. |

| July | Similar to June; occasional clouds deepen B at night but far from Emin. | Rare D after brief starts; negligible impact on monthly posture. | Both policies overlap. |

| August | Days start shortening, midday C persists, troughs deepen modestly, GEN marginal. | A handful of D segments during multi-cloud sequences top SoE and cut future starts. | CC preserves a slightly higher stance. |

| September | Shoulder returns: narrower midday plateaus, minima 30–40% common, short GEN stripes reappear. | Consolidated D episodes keep SoE higher overnight; fewer consecutive starts. | Policy contrast becomes visible again. |

| October | More time at 20–30% SoE; GEN-ON clustering increases; C windows contract. | Prominent D blocks lift SoE after each start, reducing deep excursions and start probability. | CC improves resilience vs. LF. |

| November | Weak irradiance, long nights, extended B and frequent GEN clusters, SoE ~ 25–35% for many mornings. | D common, GEN charging leaves SoE 40–55%, moderating stress. | CC clearly preferable operationally. |

| December | Most demanding month: sparse C, long B, regular GEN; 20% floor never violated (DoD = 80%). | Dense D blocks document active top-ups; LPSP ≤ 0.03 satisfied with less time near Emin than LF. | CC reduces low-SoE residency at same reliability. |

| Block | Parameter | Value/Assumption |

|---|---|---|

| PV | Specific yield (Karlsruhe, PVGIS TMY) | ≈1100 kWh/kWp·yr |

| CAPEX | EUR 800/kWp | |

| Fixed O&M | 1.2% of CAPEX per year | |

| Lifetime (economic) | 25 years | |

| Converter | Inverter efficiency (ηinv) | 0.95 |

| Charge controller efficiency (ηcc) | 0.98 | |

| Battery (Li-ion) | CAPEX | EUR 250/kWh |

| Fixed O&M | 1.5% of CAPEX per year | |

| Calendar life cap | 15 years | |

| One-way discharge efficiency (ηbat) | 0.85 | |

| Depth-of-discharge used (DoD) | 80% (usable window = 0.8·Bnec) | |

| Diesel Generator | Rated power | 12 kW(ac) |

| Specific fuel consumption (SFC) | 0.28 L/kWh | |

| Diesel price (base) | EUR 1.20/L | |

| Generator lifetime | 15 years | |

| Generator CAPEX (CAPEXGen) | EUR 500/kW (→EUR 6000 at 12 kW) | |

| Generator O&M (O&MGen) | 3%/yr of CAPEXGen | |

| Economics | Discount rate (real) | 7% |

| Objective | EUAC + VOLL·ΣEshort + ccurt·ΣEwaste | |

| VOLL | not fixed | |

| Curtailment penalty ccurt | 0 (baseline) | |

| Simulation | Time-step Δt | 15 min |

| Load series | LG-07 (Braeuer 2020 [73]), 35,040 samples | |

| Reliability | Constraint | LPSP ≤ 0.03 |

| Design grid | PV size Npv | 140…320 modules (0.40 kWp each) |

| Battery Bnec | 200…700 kWh | |

| DoD | {20%, 50%, 80%} |

| Reference | Tech Scope | Objective Terms | Reliability Term | Extra Penalties | Optimizer/Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [92] | PV–WT–BESS (islanded) | NPC/LCC (annualized) | LPSP (constraint/target) | – | Parametric/iterative |

| [93] | PV–WT | Cost (sizing) | Reliability index + SoC bounds | Converter modeling | Deterministic search |

| [3] | SAPS/HRES (review) | LCC/EUAC frameworks | LPSP coupled with cost | – | Review/taxonomy |

| [4] | PV–WT– BESS | Annualized cost (Pareto) | LPSP (co-objective) | – | GA (MOEA) |

| [94] | PV–WT– BESS | Cost or LPSP | LPSP as objective/constraint | – | Analytical + sim |

| [95] | Islanded HRES | Cost (NPC/LCOE) | LPSP threshold | – | Heuristic/DE/PSO (typical) |

| [96] | Stand-alone PV/HRES | Cost metrics (LCOE/LCC) | LPSP workflows | – | Review |

| [97] | PV–WT– BESS | NPC/LCOE (Pareto) | LPSP (co-objective) | – | MOEA |

| [98] | PV–WT–BESS–Diesel | Annualized cost | LPSP cap | – | MOEA/deterministic |

| [99] | Microgrid planning | Capex + Opex + VOLL·EENS | EENS (monetized) | – | MILP/decomposition |

| [100] | Islanded MG | Operating cost (+capex in variants) | Reliability via constraints, VOLL variants | – | MILP/control-aware |

| [101] | Islanded MG | Operating cost + battery aging cost | – | DoD/throughput-aware degradation | Firefly/heuristics |

| [102] | MG scheduling | Cost + aging cost (linear) | – | Degradation model | MILP-ready |

| [103] | Poly-generation MG | Cost + aging + curtailment cost | – | Dumping/aging penalties | MILP |

| [80] | Islanded MG | Cost + curtailment penalties | – | Time-varying curtailment weights | MILP |

| [104] | Hybrid MGs (case studies) | LCC + resilience economics | – | Empirical validation | Case study |

| [105] | 100% RES stand-alone MG | Investment + EENS cost (CERL) | LOLP/EENS monetized (no hard cap) | – | Analytical/Monte Carlo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keskinis, S.; Elmasides, C.; Kosmadakis, I.E.; Raptis, I.; Tsikalakis, A. Techno-Economic Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Microgrids with Diesel Backup Generator: A Case Study in Industrial Loads in Germany Comparing Load-Following and Cycle-Charging Control. Energies 2025, 18, 6463. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246463

Keskinis S, Elmasides C, Kosmadakis IE, Raptis I, Tsikalakis A. Techno-Economic Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Microgrids with Diesel Backup Generator: A Case Study in Industrial Loads in Germany Comparing Load-Following and Cycle-Charging Control. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6463. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246463

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeskinis, Stefanos, Costas Elmasides, Ioannis E. Kosmadakis, Iakovos Raptis, and Antonios Tsikalakis. 2025. "Techno-Economic Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Microgrids with Diesel Backup Generator: A Case Study in Industrial Loads in Germany Comparing Load-Following and Cycle-Charging Control" Energies 18, no. 24: 6463. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246463

APA StyleKeskinis, S., Elmasides, C., Kosmadakis, I. E., Raptis, I., & Tsikalakis, A. (2025). Techno-Economic Photovoltaic-Battery Energy Storage System Microgrids with Diesel Backup Generator: A Case Study in Industrial Loads in Germany Comparing Load-Following and Cycle-Charging Control. Energies, 18(24), 6463. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246463