Abstract

The adoption of autonomous-driving rovers represents a feasible solution to improve the sustainability of the agricultural sector, as they are smaller and more efficient compared to traditional machinery. However, endurance and productivity can be critical factors for the adoption of such vehicles. In addition, the autonomous-driving algorithm should guarantee that the rover is able to accomplish tasks without supervision. In this paper, a numerical analysis of an autonomous-driving rover with a hybrid fuel-cell powertrain, specifically designed for orchards and vineyards, is presented. The proposed powertrain presents a first innovative integration of a metal-hydride hydrogen-storage system into an orchard mobile machine. A Li-ion battery pack is the main energy source, while the fuel-cell system operates in a range-extender configuration. A co-simulation model was developed comprising the autonomous-driving algorithm, a multibody model, and a powertrain model. Experimental tests were carried out to characterize the fuel-cell system and the metal-hydride tank, and the obtained data were used to develop and tune their numerical models. A virtual test scenario consisting of a typical rover maneuver, namely a 180-degree turn, performed in different soil and payload conditions, was defined, and simulations were carried out evaluating the rover’s performance. The simulation results showed that the rover completed the mission in loam and hard soil conditions, and with up to 200 kg of payload. Moreover, the fuel-cell range extender significantly enhanced the rover’s endurance, with up to +60% of increase when employing a tank swap technique to replace the metal-hydride tank upon hydrogen depletion. On the contrary, in the case of critical terrain conditions, such as muddy and sandy soils, the rover was not capable of completing the task due to tire slipping.

1. Introduction

Since the dawn of human civilization, agriculture has always played a primary role in the food supply chain. In the upcoming years, it must become more sustainable while maintaining high productivity to meet the demands of a growing global population [1,2]. To improve sustainability, an effective solution is the replacement of traditional machinery with innovative systems. Indeed, traditional diesel-powered vehicles are an important source of emissions and greenhouse gases, which are generated as by-products of the combustion process [3,4]. The consequences are negative effects on human health, the environment, and the economy [5,6,7,8,9]. Consequently, to reduce the environmental impact of agricultural practices, a feasible strategy is the implementation of alternative powertrain systems, including hybrid electric, full electric, and hybrid fuel-cell configurations, which can significantly reduce the use-phase-related emissions [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Going into specifics, if fully electric vehicles may have the issue of guaranteeing a satisfactory productivity, which can be a strong barrier to their diffusion [17], hybrid solutions can ensure high productivity and sustainability at the same time [10]. Another effective strategy to improve the agricultural sector is represented by the implementation of smart farming practices [18,19]. Indeed, those practices, which include advanced technology, digitalization, and data analysis, can increase agricultural productivity while reducing the environmental impact [20].

A promising way to combine the benefits of replacing conventional agricultural machinery with innovative vehicles and implementing smart farming practices is through the deployment of autonomous agricultural rovers [21]. These vehicles can perform different tasks, ranging from low-power field operations, such as weeding, to monitoring missions, including crop-health monitoring and disease detection, thanks to the application of IoT systems, sensors, and machine-vision technology [22]. The advantages of adopting rovers in agriculture are many and include [23]:

- Labor-cost reduction.

- Higher operational efficiency.

- Optimization of resource utilization.

- Improved sustainability.

- Reduction of soil compaction issues.

To operate in the field, agricultural robots require an autonomous-driving algorithm, which must define the ideal trajectory to be followed and the motors and actuators’ control signals to follow that trajectory, and should include the possibility to detect obstacles to avoid them or to stop in case of unavoidability [24,25,26,27,28]. The definition of the trajectory involves the path-planning algorithm, while the control of the vehicle during operation is performed by the path-following and obstacle-avoidance algorithms.

Despite the undeniable advantages represented by the implementation of these rovers in agriculture, there are still challenges that must be faced to guarantee market competitiveness and widespread adoption in the future [29]. In this context, the design stage of the rover is a critical phase as it determines its peak power capabilities and endurance. Most of these rovers feature a fully electric powertrain [30,31,32], which can be a feasible solution in the case of small robots that perform mainly monitoring tasks or very low-power operations, but may be a limitation in case the robot also has to perform field operations that can affect its endurance. To address this issue, an innovative solution is represented by the implementation of a fuel-cell range-extender unit [33]. Indeed, the adoption of a fuel-cell unit could overcome, or at least limit, the problem related to endurance, without producing local emissions [34]. It should be noted that the environmental benefits deriving from the implementation of such systems are strongly related to the hydrogen-production process. At present, most of the hydrogen is produced through steam methane reforming, also known as grey hydrogen; thus, it is far from being without associated emissions [35]. Indeed, the adoption of less impactful hydrogen-production processes, such as water electrolysis, would enhance the environmental performance of fuel-cell-powered vehicles. According to the International Energy Agency, low-emission hydrogen production has been continuously increasing in recent years, indicating that several efforts have been made to promote sustainable hydrogen production [36]. In this context, an agricultural farm can produce hydrogen on its own using an electrolyzer powered with electricity coming from solar photovoltaic panels. Consequently, the adoption of fuel-cell systems is of particular interest in the agricultural sector. In addition, several efforts are carried out from the research community towards the implementation of advanced materials for fuel-cell stacks and electrolyzers; thus, their applicability can significantly increase in the upcoming years [37].

Ghopadpour et al. [38] presented a concept of a fuel-cell hybrid electric light-duty rover for agricultural applications, showing promising results in terms of autonomy compared to the pure battery solution. In the proposed solution, the fuel cell was used as a range extender, and the hydrogen was stored in a pressurized gaseous tank, with a nominal capacity of 150 g of . Going beyond the agricultural sector, another concept of a fuel-cell hybrid robot was presented by Radmanesh et al. [39]. In this case, the fuel cell operated as a primary energy source and had a rated power of 500 W, while an LFP battery was used as an auxiliary power source. Lü et al. [40] developed a fuel-cell hybrid mobile welding robot, powered with a fuel-cell/battery powertrain, and developed an optimized energy-management strategy to improve the power output of the fuel-cell. A concept of a fuel-cell/battery self-guided vehicle for industrial warehouse application was introduced in [41]. Lastly, a concept of an underwater unmanned vehicle featuring a fuel-cell/battery power system was described in [42].

Analyzing the literature, the authors note that there is a lack of studies related to autonomous-driving agricultural rovers, specifically designed for operating in orchards and vineyards, featuring a fuel-cell range-extender unit and a Li-ion battery pack as a primary energy source. Following this premise, the present study focused on a co-simulation analysis of the rover Smilla H2, a prototype presented by the Italian company Ecothea Srl at EIMA 2024, in Bologna, Italy [43]. This vehicle features an open-cathode fuel-cell system and a metal-hydride tank. Compared to the existing literature on fuel-cell-powered autonomous robots, the proposed research presents several innovative aspects. First of all, the adoption of a metal-hydride tank for hydrogen storage. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no other prototypes or design concepts of orchard mobile machines using metal-hydride tanks have been documented. Metal-hydride tanks can be a promising solution due to their high volumetric energy density and low operating pressures, making them a feasible solution for off-road systems. Indeed, compared to highly pressurized Type IV tanks, metal hydrides can reach a volumetric energy density up to five times higher compared to high-pressurized Type IV tanks [44]. Compared to Li-ion batteries, the volumetric energy density can be 10 times higher in the case of highly performing hydrides. Thus, their application is of particular interest where compactness is crucial [45]. On the contrary, compared to highly pressurized tanks, the gravimetric energy density of metal-hydride tanks is lower (usually 1/2–1/3). In the specific case of Smilla H2, the implementation of the range-extender unit increases the on-board energy storage system capacity by +50% (neglecting efficiency). Secondly, the proposed powertrain configuration differs from most of the other studies. Indeed, the only other range-extender configuration was the one proposed by Ghopadpour et al. [38]; however, the power ratio between the motor’s peak power and the fuel cell’s rated power is significantly different, thus the control strategy and the effects on the vehicle are different. Lastly, the application field and prescribed tasks of the robot are orchard and vineyard operations. Indeed, the work cycle is strictly related to it; thus, a dedicated analysis is required.

The aim of this research is to assess the feasibility of extending the operational autonomy of autonomous-driving agricultural rovers by integrating fuel-cell systems in a range-extender configuration. The main goal is to increase the vehicle’s continuous operating hours without modifying its original layout, which was initially designed for a pure battery-propulsion system. Once the main components were defined according to the vehicle constraints, the fuel-cell and hydrogen-storage systems were experimentally characterized and numerically modeled according to the collected data. The autonomous-driving strategy algorithms and the powertrain model were implemented in the MATLAB/Simulink (version R2021b) environment, while a multibody model was developed at Hexagon Adams to consider the dynamic behavior of the rover and account for terrains with different characteristics and properties [46]. A virtual test scenario, consisting of moving between orchard rows and performing a 180-degree turn once reaching the end, was defined. Simulations were carried out considering different, yet representative, soil conditions and payloads. The simulation results in terms of expected endurance were compared with the pure battery version, highlighting the benefits deriving from the implementation of the fuel-cell range-extender unit. The paper is structured as follows: the Material and Methods section (Section 2) briefly describes the rover configuration, the numerical modeling, the autonomous-driving algorithms, and the performed tests; the Results and Discussion section (Section 3) presents and deeply discusses the simulation results; finally, the Conclusions section (Section 4) summarizes the main outcomes of the paper.

2. Material and Methods

In this section, a brief description of the Smilla H2 rover is presented. Next, the autonomous-driving algorithms and the multibody model are described. After that, the numerical modeling of the powertrain and the experimental characterization procedure of the fuel-cell range-extender unit are discussed. Lastly, the virtual test scenarios and their conditions are exposed.

2.1. Case Study: Smilla H2

The vehicle under investigation is a four-wheel agricultural rover specifically designed to operate in orchards and vineyards. The vehicle is designed to perform several tasks, including transportation of loads, field monitoring, and low-power field operations. The rover is powered by four electric motors (EMs) with a rated power of 1.2 kW and a rated torque of 5 Nm, each one connected to one wheel through a right-angle planetary gear reducer with a transmission ratio of 12:1. These motors can be overloaded with a 3× factor with a S3–20% service. The rover does not have a physical steering system; thus, it performs turns using the torque vectoring technique. The main mechanical properties of the vehicle are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Rover mechanical properties. Please note that EM properties are the performance of a single motor.

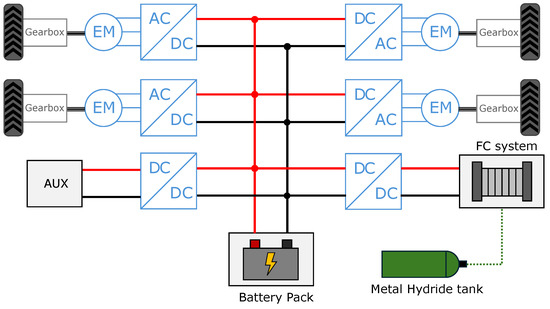

As for the powertrain, its schematic representation is shown in Figure 1. The primary energy source is a Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) battery pack, with a nominal voltage of 51.2 V and a rated capacity of 105 Ah. The battery pack is directly connected to the DC bus. The battery pack was sized considering that its nominal power at 1C of discharge was close to the total rated power of the electric motors. Furthermore, the voltage level was lower than 60 V, which is the threshold value above which the system is considered high voltage in the automotive sector. The battery pack is equipped with a Battery Management System (BMS) whose main roles are to perform cell balancing and monitor the battery pack’s internal temperature. In detail, three thermal transducers are placed within the pack to constantly monitor the temperature. The information on the actual temperature is used to detect thermal runaway or to perform-derating strategies.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Smilla H2 powertrain. Please note that AUX means all the auxiliaries and services of the vehicle (including sensors, cameras, and the FC system BoP), which are powered by a 12 V DC bus generated from the main 48 V DC bus using a DC-DC converter.

The fuel-cell range-extender unit features the FCS-C300 system, developed by Horizon Fuel-Cell Technologies (Singapore). This system is composed of an open-cathode proton-exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) with a rated power of 300 W and a voltage range of 58–30 V. The system is provided with a controller that monitors the stack’s actual voltage, current, and temperature, and controls valves and blowers. The thermal management of low-power stacks is performed by controlling blowers mounted on the stack and is significantly simpler than that of high-power stacks, which requires liquid cooling systems [47]. The fuel cell is connected to the DC bus through a unidirectional Buck-Boost DC-DC converter. The rated power of the fuel cell was chosen considering as critical parameters of compactness and ease of implementation. Low-power fuel-cell systems are characterized by a simplified BoP that strongly reduces the overall volume and simplifies its integration on the chassis. Furthermore, the rated power is close to the power required for traction when moving at low speeds.

As for the hydrogen-storage system, the rover mounts a metal-hydride (MH) tank. The tank has a rated hydrogen capacity of approximately 80 g and a maximum operating pressure of 30 bar. The adoption of an MH tank was motivated mainly by its lower operating pressure [44], which avoids critical safety issues. The capacity of the tank was chosen considering that the range-extender unit should operate at least 8 h straight when providing 80% of its rated power.

Since the rover was initially designed with a purely battery-electric configuration, the space availability for the implementation of the range-extender unit was strongly limited. Indeed, the main idea was to extend to rover autonomy without changing its overall volume, so that the unit can effectively improve the rover’s performance without requiring further mechanical modifications. As a consequence, the choice of the components was limited as a more powerful stack and a bigger MH tank were substantially not implementable without modifying the main chassis. When designing the unit, 8 h of continuous operating time of the range extender was considered as an operational requirement; thus, once the overall volume was fixed according to the constraints, the choice of both the fuel cell and the MH tank was performed considering that the unit should operate 8 h straight. A higher operational time would not be ideal as it would require a less powerful fuel-cell system, which may limit its effectiveness in improving endurance and preventing excessive battery depth of discharge, while a lower operational time would imply that the range-extender unit would not be able to operate for an entire workday.

The main properties of the powertrain elements, apart from the electric motors, are shown in Table 2. The MH tank is connected to the fuel cell through a manual pressure-regulator valve, whose role is to bring the hydrogen pressure to the proper level for the stack anode, and a solenoid valve, which is controlled by the fuel-cell system controller.

Table 2.

Powertrain components main properties.

2.2. Autonomous-Driving Strategy

The autonomous-driving algorithm implemented within the co-simulation model was specifically designed by the authors, based on algorithms available in the literature, for an autonomous rover operating in vineyards and orchards, and consisted of the following main elements:

- Path-planning.

- Path-following.

- Kinematic model.

A detailed description of the algorithm is available in the literature in other works from the same research group [24,48]. The path-planning algorithm defined the ideal trajectory according to the orchard configuration and the specific task. The algorithm was based on Dubins’ geometrical planner [49,50], thus the ideal trajectory was determined by combining segments and circular arcs given the start and arrival point and their relative orientation in the map. The ideal trajectory was defined as a sequence of points called waypoints, which were spaced according to a predefined parameter called the waypoints pitch distribution (WPP).

The path-following algorithm instead defined the strategy that the rover adopted to follow the ideal trajectory defined by the path-planning algorithm. The main outputs were the reference longitudinal and yaw speeds. The algorithm consisted of two stages:

- Local goal point (LGP) identification.

- Determination of longitudinal and yaw speed reference values.

The first stage is performed using an algorithm based on the pure-pursuit controller [51,52]. Thus, the LGP was defined by the intersection between the optimal path and a circumference centered on the rover center of mass with a radius equal to a parameter called the lookahead distance (LD). A waypoint was considered reached when its distance from the rover was below a threshold value, known as the distance threshold . Once the LGP was identified, the yaw angle , corresponding to the difference between the current vehicle orientation and the line connecting the rover center of mass and the LGP, was determined. Then, the algorithm calculates the yaw and longitudinal speeds reference values according to the following equations:

where and v are the yaw and longitudinal speeds, respectively, is the max reference speed of the rover, and corresponds to the maximum steering angle, equal to 360° for the proposed system. Indeed, the proposed configuration can perform a pivot maneuver thanks to torque vectoring.

The last element of the autonomous-driving strategy was the kinematic model. This model had to determine the rotational speeds of the wheels in order to reach the yaw and longitudinal reference speeds. The following equations were adopted [46,53]:

where and are the rotational speeds of left and right wheels, respectively, r is the wheel rolling radius, and l is the halftrack of the rover.

The wheel reference speeds were the final output of the autonomous-driving algorithm and constituted the input of the vehicle control, which instead determined the torque commands to the electric motors.

2.3. Multibody Model

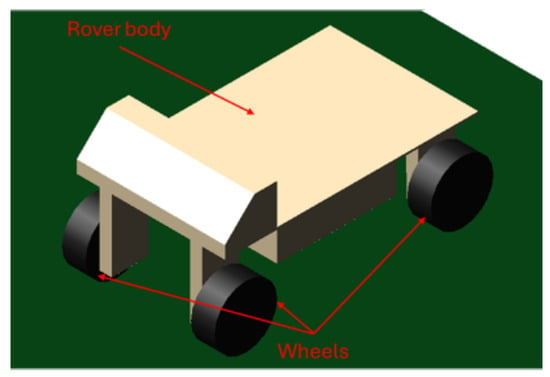

The multibody model of the rover, which was developed using Hexagon Adams (version 2024.1.1, developed by Hexagon AB, Stockholm, Sweden), consisted of a series of rigid bodies with specific geometrical and inertial properties, connected to each other with joints. In detail, two main elements were considered, namely the rover body and the wheels. A representation of the model, and of the real reference vehicle, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Multibody model of the rover.

The wheels were modeled as simple cylinders, while the rover body was modeled by combining different geometric solids. The wheels and the body were linked through revolute joints. A torque element was applied at the wheels to account for the torque coming from the electric motors. Please note that the torque element was applied directly at the wheels, thus representing the torque downstream of the mechanical coupling between the EMs and the wheels. Consequently, the torque value considered both the transmission ratio and the efficiency.

The interaction between the tires and the ground was modeled first using the following equation [46]:

where is the contact force, k represents the contact stiffness, c the contact damping, g is the interpenetration between ground and wheel, and e is an empirical coefficient that takes into account the non-linearity of the system. The values adopted during the numerical modeling are shown in Table 3. The stiffness and damping values were defined according to data available in the literature. In detail, the value of the contact stiffness was coherent with typical values obtained through compression tests on agricultural tires [54]. As for the damping coefficient, the only data that the authors found in the literature reported a coefficient of 0.7 Ns/mm for an agricultural tire with a 16″ (0.406 m) radius and a pressure of 2.2 bar. The rover under investigation featured tires with an 8″ (0.203 m) radius and approximately the same pressure; thus, given that the damping coefficient decreases as the tire radius decreases, the authors opted for considering a coefficient equal to 0.3 Ns/mm [55].

Table 3.

Adopted values for the modeling of the contact force between ground and tires.

The tire-ground interaction must also consider the capability of transmitting traction force according to the friction conditions. To consider this, a friction parameterized model was implemented. This model considered three coefficients: the static and kinetic friction coefficients and the rolling resistance coefficient. The static friction coefficient describes the torque at which the tire begins to slip, while the kinetic coefficient determines the amount of torque the tire can transmit once it begins to slip [11]. Lastly, the rolling resistance coefficient accounts for the force resisting the motion when a body rolls on a surface. Summarizing, the following equations were adopted for the modeling of the tire-ground interaction:

where and represented the traction and normal forces on the i-wheel, the torque at the i-wheel, the wheel radius, and the static and kinetic friction coefficients, respectively, the rover mass, g the acceleration of gravity, the rolling resistance coefficient, and the road slope. The kinetic friction, static friction, and rolling resistance coefficients were defined based on the soil conditions using data available in the literature.

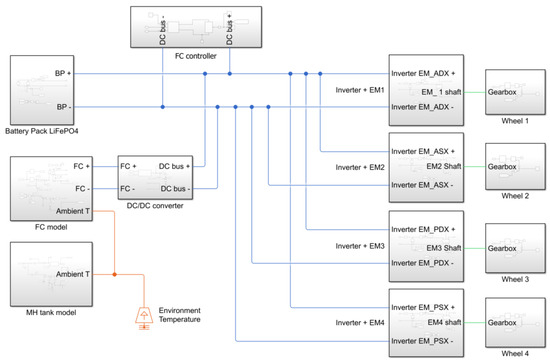

2.4. Powertrain Numerical Modeling

The numerical modeling of the powertrain, developed in the MATLAB/Simulink (version R2021b) environment, is shown in Figure 3. The numerical model included the following elements:

- Electric motors and their mechanical coupling with the wheels.

- Battery pack.

- Fuel-cell system.

- MH tank.

- Power converters.

- Vehicle control strategy.

Figure 3.

Powertrain model.

Starting from the EMs, their electrical losses were modeled as a sum of a torque-dependent term accounting for ohmic losses in the copper windings, and a speed-dependent term that instead considered the iron losses due to eddy currents. As for the mechanical gearbox, it was modeled as a fixed-ratio gear with a load-dependent efficiency. The efficiency at the nominal output torque was set equal to 90%.

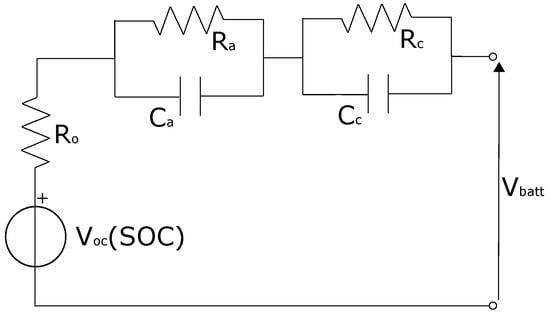

The battery pack was modeled using the equivalent circuit model shown in Figure 4 [56]. This model considered two polarization processes [57], namely activation and concentration, and the ohmic resistance. The open circuit voltage was modeled as a function of the State of Charge (SOC) according to LFP chemistry cells. The numerical model of the battery pack was limited to the electrical behavior and neglected thermal aspects. Indeed, the battery pack was tested on a test bench with a programmable unit composed of an electronic load and a power supply to perform charge and discharge cycles. During those tests, the charging current was set at 0.25C, while the discharging current was set at 0.5C. With a constant ambient temperature of 25 °C, the maximum recorded temperature during those cycles was equal to 35 °C. Consequently, since it was far from the maximum operating temperature of 65 °C declared by the cells’ manufacturer, the thermal model of the battery pack was deemed unnecessary for the proposed analysis.

Figure 4.

Battery pack equivalent circuit model.

The fuel-cell system was modeled as a voltage source using a lookup table that followed the FCS-C300 voltage–current curve. In addition, a thermal model, consisting of a controlled heat-flow-rate source and a convective heat-transfer element, was added to evaluate the thermal behavior. The heat flow was determined according to the actual fuel-cell stack efficiency and power output. As for the hydrogen consumption, the manufacturer of the system provided the hydrogen-consumption curve according to the output current of the stack. The actual polarization curve and the parameters of the thermal model were determined through experimental tests on the system. The experimental setup consisted of the fuel-cell system, a power supply for providing the FC controller’s 12 V, an electronic load (model EA-EL 9080-400 manufactured by Elektro-Automatik GmbH & Co., Viersen, Germany), a thermal camera (model FLIR E4 manufactured by Teledyne FLIR LLC, Wilsonville, OR, USA), and the MH tank. The tests were conducted varying the current absorbed by the electronic load at fixed steps from 0 to 7.5 A. During the tests, the ambient temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The test results will be described in Section 3. This approach was considered valid since this system is an open-cathode system that adopts blowers to feed air at the cathode instead of an air compressor. In high-power stacks that feature the presence of the air compressor, the dynamic behavior is critical as the compressor has a certain dynamics that may be a limiting factor for the system output [58]. Furthermore, given the range-extender configuration, the power output of the fuel-cell system was characterized by smooth and little variations, reducing the relevance of the system dynamics. To account for the power consumption of the system controller, which comprised the power absorbed by the blowers and the valves (substantially, it represented the power absorption of the system balance of plant), a DC load was added on the DC bus in the numerical model.

As for the metal-hydride tank, the reaction that describes its hydrogen desorption/absorption processes can be written as follows [59]:

where M is the metal alloy, H is hydrogen, x is the hydrogen-to-metal ratio, and Q is the heat absorbed/released during the desorption/absorption processes. From a numerical point of view, the tank was modeled considering the main parameters that affected its behavior: temperature, internal pressure, hydrogen content, and hydrogen flow. Indeed, the behavior of a metal-hydride tank can be described through PCT curves, which represent the pressure vs. concentration trend at a given temperature [60,61]. The PCT curve is characterized by a hysteresis behavior; thus, the equilibrium pressure is different for absorption and desorption processes. Furthermore, the curve is characterized by a central zone with a sloped plateau [62]. Since the analysis focused on the co-simulation of the rover during its operation, the authors considered only the desorption process. The equilibrium pressure can be described as a function of the temperature using the Van’t Hoff equation [60,62]:

where is the equilibrium pressure, is the gas constant, is the metal-hydride temperature, is the reference pressure, generally the atmospheric pressure, and and are, respectively, the reaction enthalpy and entropy of the absorption and desorption processes. The enthalpy and entropy of the reaction depend on the metal hydride. In addition, can also be expressed as a function of temperature and the hydrogen content using the following equation [63,64]:

where represents the hydrogen-to-metal atomic ratio and is the equilibrium pressure at the reference temperature . During desorption, heat is absorbed by the tank. The thermal behavior of the tank affects the chemical reaction and the equilibrium pressure; thus, it must be included. In the numerical model, conductive and convective heat-transfer elements were implemented, the first accounting for the tank wall thickness and the latter for the heat exchanged with the ambient air. However, the heat absorbed by the tank during the desorption process must be evaluated. To address this, the following equation was adopted [60]:

where is the heat absorbed, is the hydrogen molar flux and is the enthalpy of the desorption process. This equation allowed for linking the actual hydrogen flow, which was related to the power output of the fuel-cell system, with the heat absorbed. The heat evaluated according to this equation was implemented in the thermal circuit as a controlled heat-flow-rate source. Also in this case, the numerical model parameters were extrapolated through experimental tests. The experimental setup and ambient conditions were the same of the fuel-cell characterization test. The test results will be described in Section 3.

Lastly, the power converters were modeled in terms of efficiency. In detail, the efficiency was considered a function of the converter output current, with a peak equal to 95% for both the DC-DC and the Inverters.

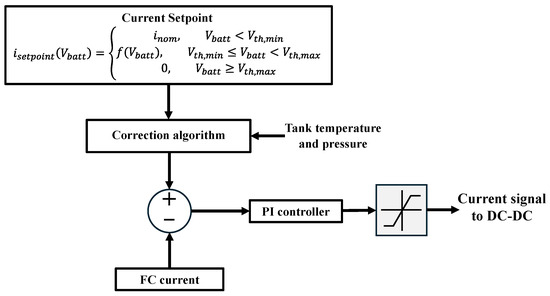

As for the vehicle control strategy, two layers were defined, one determining the EM control signals and the other defining the fuel-cell range-extender control. As for the EM control, a proportional-integral (PI) controller was implemented for each motor. Given the wheels’ reference speeds, calculated by the autonomous-driving algorithm and corresponding to the PI setpoints, the difference between them and the actual speeds determined the torque commands for the EMs. The adopted controller coefficients were = 290 and = 300. As for the range-extender control strategy, the power conditioning unit was represented by the DC-DC converter. This device was controlled in current mode; thus, the control strategy had to determine the current signal. Also in this case, a PI-controlled was implemented [65]. In detail, the PI input signal corresponded to the fuel-cell current upstream the DC-DC converter, while the setpoint was determined considering a reference value, equal to 6 A and corresponding to a fuel-cell power output of approximately 270 W, which was adjusted considering the actual battery voltage and the temperature and pressure of the MH tank. Indeed, if the tank temperature and pressure were lower than certain threshold values, the current setpoint was reduced to avoid possible hydrogen depletion at the stack anode. The adopted PI controller coefficients were = 0.1 and = 0.05. A schematic representation of the range-extender control strategy is shown in Figure 5. The values of and were set to 54.4 V (average BP cell voltage of 3.4 V) and to 56 V (average BP cell voltage of 3.5 V), while was set to 6 A.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the range-extender control strategy.

The control of the range-extender unit was developed considering the trade-off between endurance extension and durability. Considering the first aspect, the power output should be as higher as possible during normal operation. Instead, to consider durability, the authors referred to a typical fuel-cell ageing model that indicated the main factors affecting durability are idling condition, load cycling, high-power condition, and start and stop cycles [66]. Consequently, to extend the fuel-cell lifetime, the power output of the fuel cell should be with very limited variations, while high-power conditions, generally indicated as beyond 90% of the rated power, should be avoided. According to this and considering the endurance improvement as the main goal, the control strategy was defined so that the current setpoint was as constant as possible, but slightly below the threshold value considered for high-power conditions. In this way, both rover endurance and fuel-cell durability can be significantly improved. The adopted ageing model is, however, a simplified model that does not include complex mechanical and chemical degradation mechanisms. Indeed, the adoption of more detailed models and state-of-health monitoring techniques will be the subject of research in future developments [67].

2.5. Co-Simulation Model

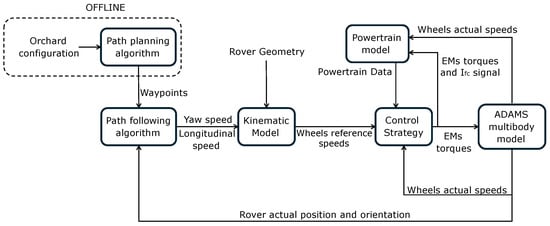

Given the multibody model, the autonomous-driving algorithms, and the powertrain numerical model, the interface between Hexagon Adams and MATLAB/Simulink had to be implemented. The co-simulation model structure is shown in Figure 6. As it can be stated, the variables that are exchanged between Simulink and Hexagon Adams are the rover’s actual position, the wheels’ actual speeds, and EM torques. It should be noted that, since in the multibody model the torque element was applied at the wheels, the EM torque provided by Simulink was multiplied by the transmission ratio and the efficiency.

Figure 6.

Co-simulation model structure.

As it can be stated, the path-planning process was performed offline with respect to the co-simulation, as it evaluated the ideal trajectory. Apart from that process, the co-simulation model included all the following elements:

- Path-following algorithm: evaluates the longitudinal and yaw reference speeds given the waypoints and the rover’s actual position and orientation.

- Kinematic model: determines the wheels’ reference speeds given the longitudinal and yaw reference speeds, and the rover geometry.

- Control strategy: determines the torque commands to the EMs and the current signal to the range extender DC-DC.

- Powertrain model: includes the numerical modeling of all the powertrain components.

- Hexagon Adams multibody model: comprises the rover multibody model.

As for the simulation parameters, the model was configured with a communication interval between MATLAB/Simulink and Hexagon Adams equal to 0.01 s.

Summarizing, the main feature of the proposed co-simulation model is that it integrates all the relevant stages of the autonomous-driving strategy, the rover multibody model, and the powertrain model, including the motors’ control strategy and the fuel-cell hybrid powertrain energy-management algorithm. By combining all these aspects and accounting for their interactions, the model provides a comprehensive representation of the rover under typical work scenarios. Furthermore, the model allows for testing in a virtual environment different operating conditions.

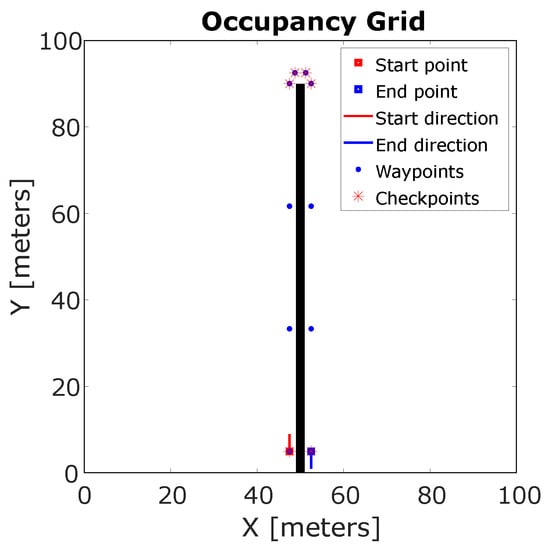

2.6. Test Scenarios

In order to analyze the behavior of the rover in different conditions, a virtual test scenario was developed. The considered rover was specifically designed for orchard operations, thus a bidimensional map with fruit rows was developed. A typical maneuver was considered, consisting of the rover moving within two fruit rows and approaching the end of the field, then performing a 180-degree turn to enter the next row. The row spacing was set a 5 m. Indeed, a typical work scenario of the rover is expected to consist of a repetition of this maneuver. A schematic representation of the proposed maneuver is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Planned trajectory for the considered maneuver.

To consider the effects of different work conditions, simulations were carried out considering different rover payloads and soil conditions.

Starting from the soil conditions, the following terrains were considered:

- Loam soil: loam soil is generally composed of 40% sand, 40% silt, and 20% clay. Loam soil is considered optimal for agricultural activities due to its optimal water management capabilities, fertility, and workability. The rover is expected to operate on loam soil.

- Hard soil: hard soil usually refers to a compacted and dense soil. As opposed to loam soil, hard soil is generally difficult to dig and cultivate; thus, it is not present in agricultural fields. Despite this, in some situations, an agricultural vehicle may encounter hard soil conditions, for example, when approaching the field, the road may be compacted due to frequent vehicle passage.

- Sandy soil: sandy soil is mainly composed of large mineral particles, with a low proportion of silt and clay, thus its structure is significantly looser compared to other soils. It is characterized by an excellent water-drainage capability; however, compared to loam soil, it has worse water-holding properties. In agriculture, sandy soil is used for root vegetables, such as carrots and potatoes, and crops like peanuts and strawberries.

- Muddy soil: muddy soil conditions can occur in case of intense or prolonged rain conditions.

From a numerical point of view, the differences among soils translate into different tire-ground contact coefficients. These coefficients were derived from the literature and are reported in Table 4 [68,69].

Table 4.

Coefficients adopted for the tire-ground interaction in different soil conditions.

As for the rover payload, 0 kg, 50 kg, 100 kg, and 200 kg were considered. In the numerical modeling, the payload was added as an additional mass on the rover.

Considering the different soils and payloads, simulations were performed considering the following cases: loam soil, hard soil, sandy soil, and muddy soil with 0 kg of payload, and 50 kg, 100 kg, and 200 kg of payload with loam soil.

In addition to considering possible errors due to rover initial misalignment and to GPS sensor accuracy, the simulations were carried out, including an initial error of 20 cm on the rover position and, at each time step, an error of 2 cm to simulate GPS accuracy performance. This last error was added as a random error to the rover position provided as input to the path-following algorithm.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, the results of the fuel-cell system and MH tank characterization procedure, and of the co-simulation analysis are exposed and discussed.

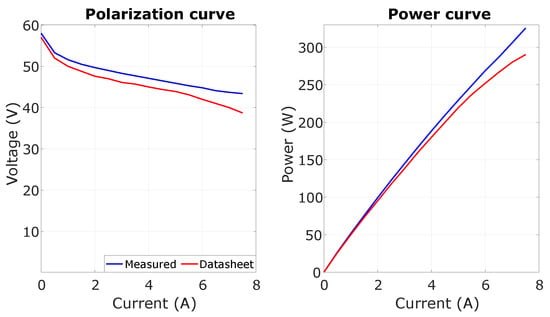

3.1. Fuel-Cell System and MH Tank Characterization

For the characterization procedure, the experimental setup was composed of the fuel-cell system, the MH tank, and a thermal camera to monitor the temperature. Starting from the fuel cell, the polarization curve was determined by monitoring the stack voltage at different current outputs. The results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Experimental results of the FCS-C300 characterization test.

The test was conducted with an environmental temperature equal to 25 °C. It can be stated that the actual polarization curve was higher than the one indicated in the datasheet, especially at high power, with a peak difference of almost 10%. From a thermal point of view, it was noted that at the maximum power output, the stack reached a peak temperature of 48 °C. In the co-simulation, the measured polarization curve was adopted to model the stack, while the thermal data were analyzed to extract the thermal model parameters. Furthermore, the fuel-cell system, to maintain a proper humidity level, has a short-circuit procedure according to which, approximately every 10 s, it brings its voltage to zero for 0.1 s, then brings it back to the normal level [70]. This behavior was implemented in the numerical model. As for the power absorption of the fuel-cell controller, which comprised the power required by the blowers, it was noted that it remained constant around 15 W until the fuel-cell temperature reached 40 °C. When this threshold was exceeded, the power absorption rose to approximately 25 W, as the blower rotational speed increased to limit the temperature rise.

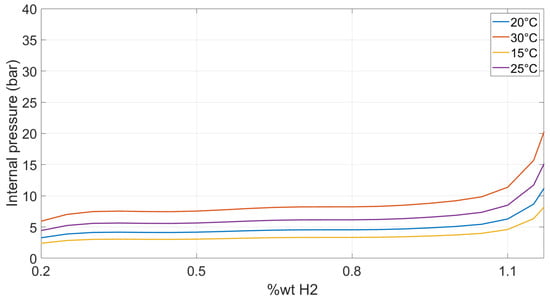

As for the MH tank characterization, the procedure consisted of monitoring the temperature and the internal pressure while discharging [60]. The goal of the test was to determine the main parameters of Equations (8) and (9) for the discharging process. To determine the enthalpy and entropy of the reaction, the value of the internal pressure of the tank was monitored at different temperatures and with the same hydrogen content. To determine the PCT curve, the tank pressure and temperature were monitored during a complete discharge.

The results in terms of enthalpy and entropy of the desorption process are shown in Table 5. Analyzing the results, it was possible to have a full characterization according to Equation (9). In addition, given the enthalpy of the reaction, it was estimated that the heat absorbed by the tank at the maximum fuel-cell power was equal to approximately 100 W.

Table 5.

MH tank characterization results for the discharging process.

The results of the MH tank characterization are shown in Figure 9. The thermal parameters derived from the tests and adopted in the numerical models are summarized in Table 6. The convective heat transfer for the fuel-cell stack might seem high; however, in the simulation, the exchange area was approximated to the surface of the lateral side of the stack, but in reality, that face is characterized by a series of internal channels, thus the exchange area is significantly higher. Consequently, the convective heat transfer derived from the experimental data is high due to the actual exchange area being larger than the one adopted in the model. The obtained models were tested and validated by running a simulation that reproduced the same conditions of the characterization tests. Indeed, the maximum difference between the simulated temperature and the experimental one was below 2 °C.

Figure 9.

Experimental results for the MH tank characterization.

Table 6.

Thermal parameters extrapolated from the characterization tests.

3.2. Co-Simulation Results

In this section, the results of the co-simulation analysis are presented. All the simulations were carried out considering the same initial conditions in terms of tank hydrogen content, batteries’ SoC, and ambient temperature. In detail, the initial hydrogen content was set so that the initial hydrogen pressure at the ambient temperature, set to 298.15 K, was equal to 10 bar. The initial battery’s SoC was set equal to 80%.

Each simulation took approximately 20 s of computational time for a virtual simulation time of around 105 s; thus, the ratio between simulation and computational times was around 5. As a result, it can be asserted that the developed model is suitable for long-term simulations.

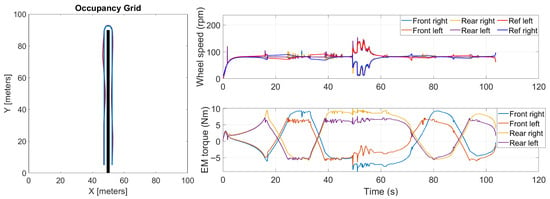

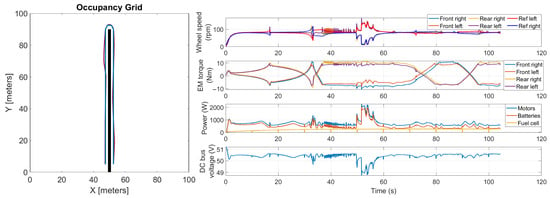

Starting from the case with 0 kg of payload and loam soil, the results of the simulation in terms of actual trajectory, wheel speeds, and EM torques are shown in Figure 10. It can be stated that the rover’s actual trajectory oscillated around the ideal one, and the maximum trajectory deviation was 0.83 m. The average traction power was 689 W, while the overall peak power demand was 2251 W. The oscillation around the ideal trajectory causes the electronic motors to operate regularly both in traction and braking as the rover adopts the torque vectoring technique to turn.

Figure 10.

Co-simulation results for the case of 0 kg of payload and loam soil. Please note that in the left figure, the blue line represents the ideal trajectory defined by the path-planning algorithm, while the red one is the actual trajectory performed by the rover.

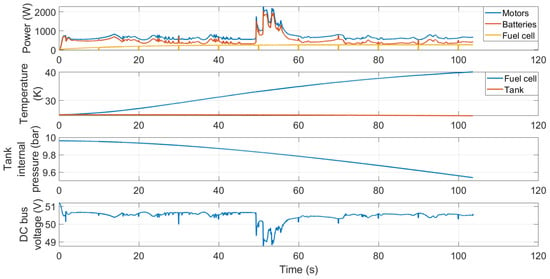

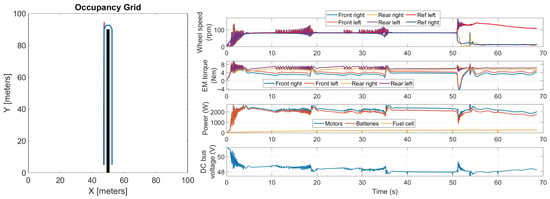

As for the powertrain parameters, the results are shown in Figure 11. As can be noted, the fuel-cell range-extender unit operated as defined by its control algorithm, and its output was not dependent on the load conditions. The fuel-cell temperature increased and was about to reach the regime condition around 40–45 °C. On the contrary, the tank temperature was decreasing; however, the simulation time did not allow for reaching the regime condition. The simulation was carried out considering the tank almost full of hydrogen; thus, the internal pressure of the tank decreased significantly from 10 bar to less than 9.6 bar due to the tank being in the part of the PCT curve with a high slope. Consequently, little variations in the hydrogen content caused a non-negligible reduction in the equilibrium pressure. In addition, the reduction of the tank temperature also caused a decrease in the internal pressure.

Figure 11.

Co-simulation results for the powertrain model for the case of 0 kg of payload and loam soil.

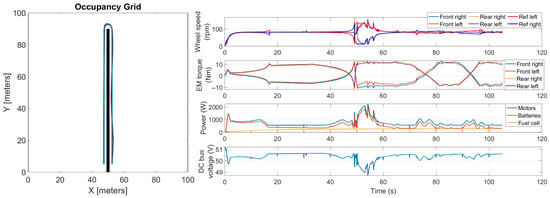

As for the case with 50 kg of payload, the results are shown in Figure 12. For this case, the maximum trajectory deviation was 1 m, while the mean and maximum powers for traction were 708 W and 2437 W, respectively. Thus, it can be stated that an increase in the payload weight caused a worsening of the performance in terms of trajectory deviation. Regarding the behavior of the fuel-cell range-extender unit, the unit operated in the same way as in the previous case, as expected.

Figure 12.

Co-simulation results for the case of 50 kg of payload and loam soil.

Compared to the previous case, an increase in the wheel speed oscillation when approaching the end of the row was noted. These oscillations corresponded to the points where the actual trajectory deviated more from the ideal one. Indeed, the control had to increase the yaw angle and, since the rover adopted a torque vectoring technique, this translated into a loss of grip and an increase in wheel slip.

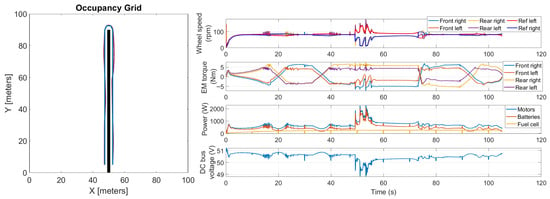

Regarding the case with 100 kg of payload, the results are shown in Figure 13. In this case, the maximum trajectory deviation was approximately 1 m, while the mean and maximum powers for traction were 732 W and 2370 W, respectively. Compared to the case with 50 kg of payload, the trajectory deviation did not increase significantly. Furthermore, the peak power absorption of the electric motors also did not change much. In terms of tire slip, some oscillations on the wheel speed were noted, similarly to the previous case. As a consequence, it can be stated that the rover’s behavior with 100 kg of payload was similar to the case with 50 kg, with the only difference in terms of mean power required for traction.

Figure 13.

Co-simulation results for the case of 100 kg of payload and loam soil.

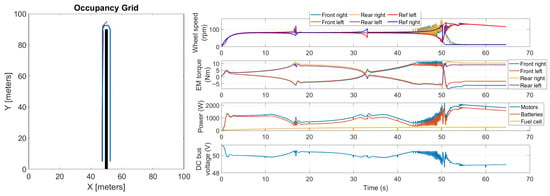

Lastly, the results for the case with 200 kg of payload are shown in Figure 14. In this case, the rover’s performance in terms of actual trajectory was better compared to all the previous cases, with a maximum trajectory deviation of 0.77 m. This can be attributed to the fact that the higher mass might have improved the rover’s stability, reducing wheel speed oscillations due to the higher inertia of the system. Indeed, the higher inertia can mitigate the effects of torque oscillations caused by the continuous corrections coming from the autonomous-driving algorithm. It should be noted that these corrections can be caused by GPS positioning errors and limited resolution, thus corrections on the trajectory can occur even if the rover is on the ideal trajectory. In this scenario, the higher inertia acted similarly to a low-pass filter. In addition, the normal contact force between tires and ground was higher, thus the maximum transmittable torque was higher. At lower payloads (50 and 100 kg), the mass increase had a negative effect as the benefits of the higher inertia were not so relevant as in the case with 200 kg of payload. Indeed, at 50 and 100 kg of payload, the negative effects on the rover controller related to the increased power demand for traction were predominant. In addition, if a higher mass can reduce the trajectory oscillations, on the other hand, it can cause an increased trajectory deviation when performing the turn maneuver. Overall, combining all these factors, the results showed that the negative effects are predominant at lower payloads, while at higher payloads, the positive effects are more relevant. In terms of mean and maximum power for traction, the values were 761 W and 2329 W, respectively.

Figure 14.

Co-simulation results for the case of 200 kg of payload and loam soil.

As for the influence of the soil conditions, the results for the case with 0 kg of payload and hard soil are shown in Figure 15. For this case, the maximum trajectory deviation was 0.85 m, while the mean and maximum powers for traction were 686 W and 2335 W, respectively. Comparing these results with the loam soil case, it can be noted that the rover behaved similarly. Indeed, hard soil conditions are not critical for the rover as friction coefficients allow for enough capability to transmit force to the ground.

Figure 15.

Co-simulation results for the case of 0 kg of payload and hard soil.

Considering the case with sandy soil, the results are shown in Figure 16. As it can be stated, in this case, the rover was not able to perform the maneuver. Indeed, the soil conditions did not allow the rover the have enough yaw speed to perform the turn. Analyzing the figure, several oscillations in the wheel speeds, indicating that they started to slip, can be noted. In detail, the external wheels slipped, and thus the rover did not reach the target yaw angle. In terms of power absorption, the sandy soil also caused an increase in the mean power required by the motors, which was 1120 W (+63% compared to loam soil). On the contrary, the peak power did not significantly differ from the other cases, with a value of 2327 W.

Figure 16.

Co-simulation results for the case of 0 kg of payload and sandy soil.

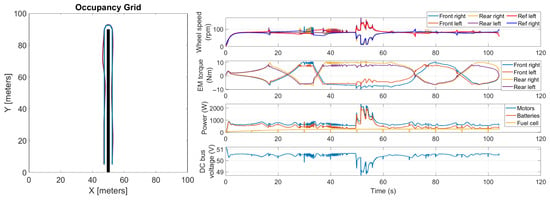

Lastly, the results for the case with muddy soil are shown in Figure 17. Also in this case, the rover was not able to complete the maneuver. As a matter of fact, the rover was absolutely unable to approach the turn due to excessive wheel slip. In addition, significant oscillations in the wheel speeds occurred every time the reference speed changed. Due to the particularly critical conditions, the average power required for traction was significantly higher compared to the other cases, with a value of 2099 W. Also, the peak power was higher, with a value equal to 2799 W.

Figure 17.

Co-simulation results for the case of 0 kg of payload and muddy soil.

Overall, soil conditions can deeply affect the rover’s performance. Specifically, the capability of the rover’s wheels to transmit torque to the ground is crucial for performing curve trajectories. Indeed, in the case of sandy and muddy soil conditions, the rover’s trajectory was clearly closer to a straight line compared to the other cases. This was caused by the absence of a physical steering system; thus, to perform turns, the rover had to increase the external wheels’ speeds and reduce those of the internal ones; however, the constraints imposed by the friction coefficients in terms of transmittable torque limited the rover’s capability of achieving this and caused tire slip. This issue was exacerbated in the case of muddy soil, where the rover was absolutely not capable of performing the turn.

A comparison of the results obtained in the different simulated scenarios is exposed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison among the different simulated scenarios.

3.3. Discussion

Considering the capacity of the battery pack, equal to approximately 5.4 kWh, the expected endurance of the rover, in the case of no payload and of loam and hard soil, is approximately 7 h and 50 min without the fuel-cell range-extender unit.

With the introduction of the range-extender unit, two different scenarios can be considered. In the first one, when the tank is running out of hydrogen and the tank’s internal pressure reaches a lower threshold value, the range-extender unit is turned off. In this case, considering the fuel-cell power output set by the control strategy, its hydrogen-consumption curve, and the hydrogen tank capacity, this situation occurs after approximately 6 h of operation. In this case, the expected endurance, considering the case of no payload and loam or hard soil, is of 10 h and 6 min (+29%).

In the second scenario, when the tank is running out of hydrogen, it can be substituted using a tank swap technique. In this case, the discharged tank is replaced with a full one, so that the fuel-cell range-extender unit can operate almost continuously apart from the stop for the substitution, which requires the system to be turned off. In this case, the expected endurance is 12 h and 30 min (+60%), thus significantly higher compared to the pure battery configuration.

A comparison in terms of expected endurance for the different cases is shown in Table 8. The adoption of the rover to replace the traditional tractor in low-power field operations is expected to significantly reduce the related equivalent emissions. Considering studies in the literature, this reduction can reach up to 50–60% when using an autonomous vehicle with a rated power similar to that of the traditional vehicle, thus when using a lighter vehicle, this value is expected to further increase [71,72]. However, a further analysis is necessary to effectively assess the environmental benefits of the rover.

Table 8.

Expected endurance for the different cases. Please note that the percentage values indicate the improvement compared to the battery-only (no range extender) case in the same scenario.

In the table, the expected endurance for the cases with sandy and muddy soil was evaluated considering the mean power. Even if the rover did not pass the test, the authors deemed that evaluating the expected endurance in the case of high power required for traction would provide useful information for the proposed analysis, as they are indicative of high-power scenarios.

Considering the hydrogen-consumption curve provided by the manufacturer, the consumption when the rated power of the fuel cell is equal to 270 W is of g/s, thus considering the power absorbed by the controller, it can be stated that the fuel-cell system operated at a system efficiency of 48% (also considering the efficiency of the DC-DC at the stack’s output for the connection to the DC bus). Generally, the efficiency of a fuel-cell system presents its peak at around 20–30% of the rated power, and decreases at higher loads. However, for the specific case under investigation, a lower fuel-cell power output would not be acceptable, as it would not be able to effectively extend the endurance.

Analyzing the results and considering the case without a tank swap, it can be stated that the benefits of introducing the range-extender unit can be maximized if the expected endurance is at least 6 h, so that all the hydrogen contained in the MH tank can be exploited. In almost all scenarios where this happened, the endurance improvement was estimated at +29%. On the contrary, in the case of an expected endurance lower than 6 h, the benefit was lower (+14% in the case of muddy soil).

As for the case with tank swap, the benefits were higher for the lowest power-demanding scenarios, ranging from +61% for the hard soil and no payload scenario, to +52% for the loam soil and 200 kg payload scenario. In these cases, the tank swap technique can be useful in providing additional endurance. On the contrary, in the case of more power-demanding conditions, the benefits compared to not performing the tank swap were significantly lower. Indeed, it can be stated that if the expected endurance is lower than or equal to 6 h, the tank swap is pointless, as the remaining battery capacity is zero and the range-extender unit is not capable of providing enough power to solely propel the vehicle. If the expected endurance is higher than 6 h, the higher it is, the more significant the benefits of performing the tank swap are.

The obtained results are valid when considering a new and healthy stack. Over time, due to degradation mechanisms, a reduction in the stack power output and efficiency is expected. Degradation occurs for several reasons, including degradation or loss of materials, mechanical damage, humidity, power fluctuations, and so on. The main effect of the ageing process is a reduction in the stack voltage, which causes a decrease in the power output at a given current density. According to papers available literature, with a fixed stack current, the decrease in the voltage output was estimated to be of 4% in approximately 1200 h, thus a degradation rate of %/h can be expected [73].

Regarding the mechanical performance of the rover, the simulations clearly stated that in critical terrain conditions, the adopted configuration does not allow the performance of maneuvers that require a low turning radius. To overcome this limit, a mechanical modification, including the implementation of a physical steering system, should be made. Otherwise, at the current state, the rover should be used only with good terrain conditions and without rain.

4. Conclusions

The proposed paper presents a co-simulation model to investigate the adoption of an agricultural rover powered with a hybrid fuel-cell powertrain and designed specifically to operate in orchards and vineyards. The powertrain configuration features a primary energy source, consisting of a 5.4 kWh Li-ion battery pack, and a secondary energy source, a fuel-cell range-extender unit with a metal-hydride tank for hydrogen storage.

The co-simulation model features a multibody model of the rover, developed in Hexagon Adams, and a MATLAB/Simulink model consisting of the autonomous-driving strategy and the powertrain model. Given an orchard configuration and a work scenario in which the rover reached the end of the orchard row and then performed a 180-degree turn, simulations were carried out considering different conditions in terms of payload and soil properties. A path-planning algorithm was adopted to establish the ideal trajectory, while a path-following algorithm was used to determine the reference wheel speeds to follow that trajectory. Lastly, a PI controller was used to determine the torque to be applied at the wheels according to the actual difference between the reference and actual speeds. The multibody model was exploited to evaluate the dynamic behavior of the vehicle and consisted of the rover chassis and wheels.

As for the powertrain numerical model, the main elements of the rover powertrain were modeled in MATLAB/Simulink. Focusing on the range-extender unit, experimental tests were carried out to characterize its main elements. Numerical models were specifically developed and tuned using the obtained experimental data to properly emulate the fuel-cell system and the metal-hydride tank.

Once the whole co-simulation numerical model was established, simulations were carried out to evaluate the rover’s behavior under typical work conditions. Analyzing the results, the following considerations were outlined:

- The rover was capable of performing the proposed maneuver considering loam and hard soils, and with a payload from 0 to the maximum considered value of 200 kg; on the contrary, with critical soils such as sandy and muddy terrains, the rover was not capable of performing the 180-degree maneuver.

- Tire slipping was a critical factor with sandy and muddy soils, as the rover was not capable of performing the torque vectoring technique.

- The maximum trajectory deviation with loam and hard soils was estimated to be equal to 1 m.

- The average power for traction, considering loam and hard soils, was in the range 680–760 W, while the peak power was around 2400 W.

- The range-extender unit operated as defined by the control strategy and was capable of extending the autonomy from +14 to +61% depending on the specific case.

Overall, the co-simulation analysis indicated that the autonomous-driving algorithm and the powertrain configuration can ensure satisfactory rover performance, even if in the case of critical terrains, the rover may encounter difficulties in performing maneuvers in tight spaces. The range-extender unit successfully extended the rover’s autonomy without adding significant weight or requiring high space availability. Future work will focus on the experimental testing of the proposed rover configuration and on the development of an intelligent energy-management strategy that considers a more detailed fuel-cell ageing model and a battery-degradation model, in order to optimize and enhance durability. In addition, a life-cycle assessment of the rover and its impact on the overall emissions produced by the farm could be the subject of research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.; methodology, V.M. and S.M.; software, V.M. and S.M.; validation, V.M., S.M. and F.M.; formal analysis, V.M. and S.M.; investigation, V.M. and S.M.; resources, V.M. and S.M.; data curation, V.M. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M., S.M., F.M. and A.S.; visualization, V.M., S.M., F.M. and A.S.; supervision, V.M., S.M., F.M. and A.S.; project administration, V.M., F.M. and A.S.; funding acquisition, F.M. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 4WD | 4 Wheel Drive |

| AUX | Auxiliaries |

| BP | Battery Pack |

| DC | Direct Current |

| FC | Fuel Cell |

| EM | Electric Motor |

| LD | Lookahead Distance |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| LGP | Local Goal Point |

| Li-ion | Lithium Ion |

| MH | Metal Hydride |

| OA | Obstacle Avoidance |

| PCT | Pressure vs. Concentration at given Temperature |

| PEMFC | Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

| PI | Proportional-Integral |

| SOC | State Of Charge |

| WPP | Waypoints Pitch Distribution |

References

- Fróna, D.; Szenderák, J.; Harangi-Rákos, M. The Challenge of Feeding the World. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calicioglu, O.; Flammini, A.; Bracco, S.; Bellù, L.; Sims, R. The Future Challenges of Food and Agriculture: An Integrated Analysis of Trends and Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Xu, P.; Shen, J. Measurement of engine performance and maps-based emission prediction of agricultural tractors under actual operating conditions. Measurement 2023, 222, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buberger, J.; Kersten, A.; Kuder, M.; Eckerle, R.; Weyh, T.; Thiringer, T. Total CO2-equivalent life-cycle emissions from commercially available passenger cars. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.; Hyun, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, H. Increase in household energy consumption due to ambient air pollution. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Qin, X.S.; Zhang, X.L.; Liu, B.J. Study of climate change impact on hydro-climatic extremes in the Hanjiang River basin, China, using CORDEX-EAS data. Weather. Cli. Extrem. 2022, 38, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. The Impacts of Air Pollution on Health and Economy in Southeast Asia. Energies 2020, 13, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anenberg, S.C.; Achakulwisut, P.; Brauer, M.; Moran, D.; Apte, J.S.; Henze, D.K. Particulate matter-attributable mortality and relationships with carbon dioxide in 250 urban areas worldwide. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDuffle, E.E.; Martin, R.V.; Spadaro, J.V.; Burnett, R.; Smith, S.J.; O’Rourke, P.; Hammer, M.S.; van Donkelaar, A.; Bindle, L.; Shah, V.; et al. Source sector and fuel contributions to ambient PM2.5 and attributable mortality across multiple spatial scales. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocera, F.; Martini, V.; Somà, A. Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Electric Architectures for Specialized Agricultural Tractors. Energies 2022, 15, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Carboon Footprint Enhancement of an Agricultural Telehandler through the Application of a Fuel Cell Powertrain. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Soma’, A. Life Cycle Assessment Comparison of Orchard Tractors Powered by Diesel and Hydrogen Fuel Cell. Energies 2024, 17, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascuzzi, S.; Łyp-Wrońska, K.; Gdowska, K.; Paciolla, F. Sustainability Evaluation of Hybrid Agriculture-Tractor Powertrains. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. New Challenges Towards Electrification Sustainability: Environmental Impact Assessment Comparison Between ICE and Hybrid-Electric Orchard Tractor. In Proceedings of the 2023 JSAE/SAE Powertrains, Energy and Lubricants International Meeting, Kyoto, Japan, 29 August–1 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Numerical Investigation of a Fuel Cell-Powered Agricultural Tractor. Energies 2022, 15, 8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, A.; Kivekäs, K.; Freyermuth, V.; Vijayagopal, R.; Kim, N. Simulation-Based Assessment of Energy Consumption of Alternative Powertrains in Agricultural Tractors. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, J.; Hoestra, J. Will farmers go electric? How Dutch environmental regulation affects tractor purchase motivations and preferences. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.B.M.; Le, A.T.; Heo, S.; Chung, Y.S.; Mansoor, S. The Path to Smart Farming: In-novations and Opportunities in Precision Agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alwis, S.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Na, M.H.; Ofoghi, B.; Sajjanhar, A. A survey on smart farming data, applications and techniques. Comput. Ind. 2022, 138, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2022, 3, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, F.; Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Chen, D.; Zhu, Z.; Song, Z. A Review of the Current Status and Common Key Technologies for Agricultural Field Robots. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulpi, F.; Marani, R.; Petitti, A.; Reina, G.; Milella, A. An RGB-D multi-view perspective for autonomous agricultural robots. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Chavez, Z.B.; Porcaro, A.; De Simone, M.C.; Guida, D. Improving Sustainable Viticulture in Developing Countries: A Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Autonomous Driving Strategy for a Specialized Four-Wheel Differential-Drive Agricultural Rover. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, M.; Onsy, A.; Ghanbari, A.; Haikal, A.Y. Path Planning Algorithms in the Autonomous Driving System: A Comprehensive Review. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2024, 174, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, V.; Gokasan, M. A Novel Obstacle Avoidance Algorithm: “Follow the Gap Method”. Rob. Autom. Syst. 2012, 60, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Park, C.H.; Jang, Y.Y.; Gu, J.D.; Kim, C.Y. Performance Evaluation of an Autonomously Driven Agricultural Vehicle in an Orchard Environment. Sensors 2022, 22, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Co-Simulation of a Specialized Tractor for Autonomous Driving in Orchards; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Papantonatou, M.-Z.; uyar, H.; Nychas, K.; Psiroukis, V.; Kasimati, A.; Nieuwenhuizen, A.; Van Evert, F.K.; Fountas, S. Stakeholders’ perspective on smart farming robotic solutions. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Xu, R.; Halloran, H.; Li, C. Development of a Multi-Purpose Autonomous Differential Drive Mobile Robot for Plant Phenotyping and Soil Sensing. Electronics 2020, 9, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantelli, L.; Bonaccorso, F.; Longo, D.; Melita, C.D.; Schillaci, G.; Muscato, G. A Small Versatile Electrical Robot for Autonomous Spraying in Agriculture. AgriEngineering 2019, 1, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, D.; Sehsah, E.-S.; Bumann, O.; Morhard, J.; Griepentrog, H.W. Development of an Autonomous Electric Robot Implement for Intra-Row Weeding in Vineyards. Agriculture 2019, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Z.; Nader, W.B. PEM fuel cell as an auxiliary power unit for range extended hybrid electric vehicles. Energy 2022, 239, 121933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.-T.; Pang, Y.-J.; Wang, W.-W.; Zhen, H.-S.; Wei, Z.-L. A Case Study Using Hydrogen Fuel Cell as Range Extender for Lithium Battery Electric Vehicle. Energies 2024, 17, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Wang, J. Review and comparison of various hydrogen production methods based on costs and life cycle impact assessment indicators. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 38612–38635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Hydrogen Review. 2025. Paris. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2025 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Li, X.; Ye, T.; Meng, X.; He, D.; Lu, L.; Song, K.; Jiang, J.; Sun, C. Advances in the Application of Sulfonated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone) (SPEEK) and Its Organic Composite Membranes for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs). Polymers 2024, 16, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobadpour, A.; Cardenas, A.; Monsalve, G.; Mousazadeh, H. Optimal Design of Energy Sources for a Photovoltaic/Fuel Cell Extended-Range Agricultural Mobile Robot. Robotics 2023, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radmanesh, H.; Farhadi Gharibeh, H. Energy Management of a Fuel Cell Electric Robot Based on Hydrogen Value and Battery Overcharge Control. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Qian, S. Energy management and distribution of fuel cell hybrid power system based on efficient and stable movement of mobile robot. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 94, 1064–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenChikha, K.; Amamou, A.; Kelouwani, S.; Ben Abdelghani, A.B.; Kandidayeni, M.; Agbossou, K. Online Energy Management Strategy for a Fuel Cell Hybrid Self Guided Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Vehicle Power and Propulsion (VPPC), Merced, CA, USA, 1–4 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Yi, H.; Zhuo, F. Design and Energy Management Comparison of Fuel Cell Hybrid Power System for Underwater Unmanned Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Nanjing, China, 23–25 December 2021; pp. 3630–3635. [Google Scholar]

- Ecothea Srl Smilla H2. Available online: https://ecothea.it/attivita-e-progetti/smilla-h2/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Li, Y.; Teliz, E.; Zinola, F.; Díaz, V. Design of a AB5-metal hydride cylindrical tank for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 33889–33898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpati, G.; Frasci, E.; Di Ilio, G.; Jannelli, E. A comprehensive review on metal hydrides-based hydrogen storage systems for mobile applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Soma’, A. Co-Simulation Model of an Autonomous Driving Rover for Agricultural Applications. Robotics 2025, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hou, T.; Jiang, J.; Grigoriev, S.A.; Fan, F.; Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, C. Thermal management of liquid-cooled proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A review. J. Power Sources 2025, 648, 237227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Mocera, F. Experimental Analysis of an Autonomous Driving Strategy for a Four-Wheel Differential Drive Agricultural Rover. In Proceedings of the AIAS 2024, Naples, Italy, 4–7 September 2024; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Shkel, A.M.; Lumelsky, V. Classification of the Dubins Set. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2001, 34, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, D.; Sun, H. 2D Dubins Path in Environments with Obstacle. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macenski, S.; Singh, S.; Martín, F.; Ginés, J. Regulated Pure Pursuit for Robot Path Tracking. Auton. Robots 2023, 47, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, C.R. Implementation of the Pure Pursuit Path Tracking Algorithm; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, J.; Magallanes, J.; Denegri, E.; Canahuire, R. Trajectory Tracking Control of a Differential Wheeled Mobile Robot: A Polar Coordinates Control and LQR Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE XXV International Conference on Electronics, Electrical Engineering and Computing (IN-TERCON), Lima, Peru, 8–10 August 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, H.; Oh, J.; Chung, W.-J.; Han, H.-W.; Kim, J.-T.; Park, Y.-J.; Park, Y. Measurement of Stiffness and Damping Coefficient of Rubber Tractor Tires Using Dynamic Cleat Test Based on Point Contact Model. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, D.M.; Hong, Z.s.; Hùng, D.V.; Ngoc, N.T. Study on the vertical stiffness and damping coefficient of tractor tire using semi-empirical model. Hue Univ. J. Sci. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2013, 83, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, T. A comparative study of different equivalent circuit models for estimating state-of-charge of lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 259, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xiong, R.; Fan, J. Evaluation of Lithium-Ion Battery Equivalent Circuit Models for State of Charge Estimation by an Experimental Approach. Energies 2011, 4, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Rojas, A.; Lopez Lopez, G.; Gomez-Aguilar, J.F.; Alvarado, V.M.; Sandoval Torres, C.L. Control of the Air Supply Subsystem in a PEMFC with Balance of Plant Simulation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Mane, R.; Sharma, P. Heat transfer techniques in metal hydride hydrogen storage: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30661–30682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.H.; Chabane, D.; N’Diaye, A.; Ait-Amirat, Y.; Djerdir, A. Static and Dynamic Characterization of Metal Hydride Tanks for Energy Management Applications. Renew. Energy 2022, 191, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Colbe, J.B.; Ares, J.-R.; Barale, J.; Baricco, M.; Buckley, C.; Capurso, G.; Gallandat, N.; Grant, D.M.; Guzik, M.N.; Jacob, I.; et al. Application of hydrides in hydrogen storage and compression: Achievements, outlook and perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7780–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopčič, N.; Grimmer, I.; Winkler, F.; Sartory, M.; Trattner, A. A review on metal hydride materials for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, D.; Harel, F.; Djerdir, A.; Candusso, D.; Elkedim, O.; Fenineche, N. Energetic modeling, simulation and experimental of hydrogen desorption in a hydride tank. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Webb, C.J.; Gray, E.M. One-dimensional metal-hydride tank model and simulation in Matlab-Simulink. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 5048–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, V.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Design and Experimental Validation of a Scaled Test Bench for the Emulation of a Hybrid Fuel Cell Powertrain for Agricultural Tractors. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, P.; Chang, Q.; Tang, T. A quick evaluating method for automotive fuel cell lifetime. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 3829–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Tang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, C. Polarization loss decomposition-based online health state estimation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelraj, D.; Jaichandar, S.; Rajan, G.; Govindan, S. Coefficient of Friction in Different Road Conditions by Various Control Methods—An Overall Review. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 2018, 8, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Gao, J.; Diao, J.; Song, X. Numerical Simulations of Tire Steering on Sandy Soil Based on Discrete Element Method. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 015015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Zarzycki, M.; Raźniak, A.; Rosół, M. Applying a 2 kW Polymer Membrane Fuel-Cell Stack to Building Hybrid Power Sources for Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]