Deep Eutectic Solvents and Anaerobic Digestion for Apple Pomace Valorization: A Critical Review of Integration Strategies for Low-Carbon Biofuel Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Component | Typical Range (% Dry wt.) | Bio-Energy Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose) | 10–18% | Rapidly fermentable; enhances hydrolysis and accelerates methane formation. | [7] |

| Cellulose | 20–25% | Hydrolysable to glucose; major contributor to biogas/ethanol yield after pretreatment. | [6] |

| Hemicellulose | 12–20% | Releases pentoses; increases methane yield when solubilized by DES pretreatment. | [9] |

| Pectin | 8–12% | High biodegradability; enhances volatile fatty acid formation in AD. | [2] |

| Lignin | 15–30% | Recalcitrant barrier; removal or depolymerization improves microbial access. | [8] |

| Protein | 3–5% | Provides nitrogen source for methanogenic consortia; improves C:N balance. | [4] |

| Lipids | 2–4% | Minor fraction but contributes long-chain fatty acids, improving biogas calorific value. | [12] |

| Polyphenols & antioxidants | 0.3–1.2% | Can inhibit AD if concentrated; recoverable as high-value co-products. | [1] |

2. Literature Review on Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment

2.1. Conventional and Emerging Pretreatment Technologies

2.1.1. Physical Pretreatments

2.1.2. Chemical Pretreatments

Dilute Acid (DA) Pretreatment

Alkaline Pretreatment

Organosolv Pretreatment

2.1.3. Ionic Liquid (IL) Pretreatment

2.1.4. Ammonia Fiber Expansion (AFEX)

2.2. Advantages and Limitations of DES-Based Pretreatment

2.2.1. Fundamental Advantages

2.2.2. Critical Limitations and Trade-Offs

2.3. Comparative Analysis of Pretreatment Methods

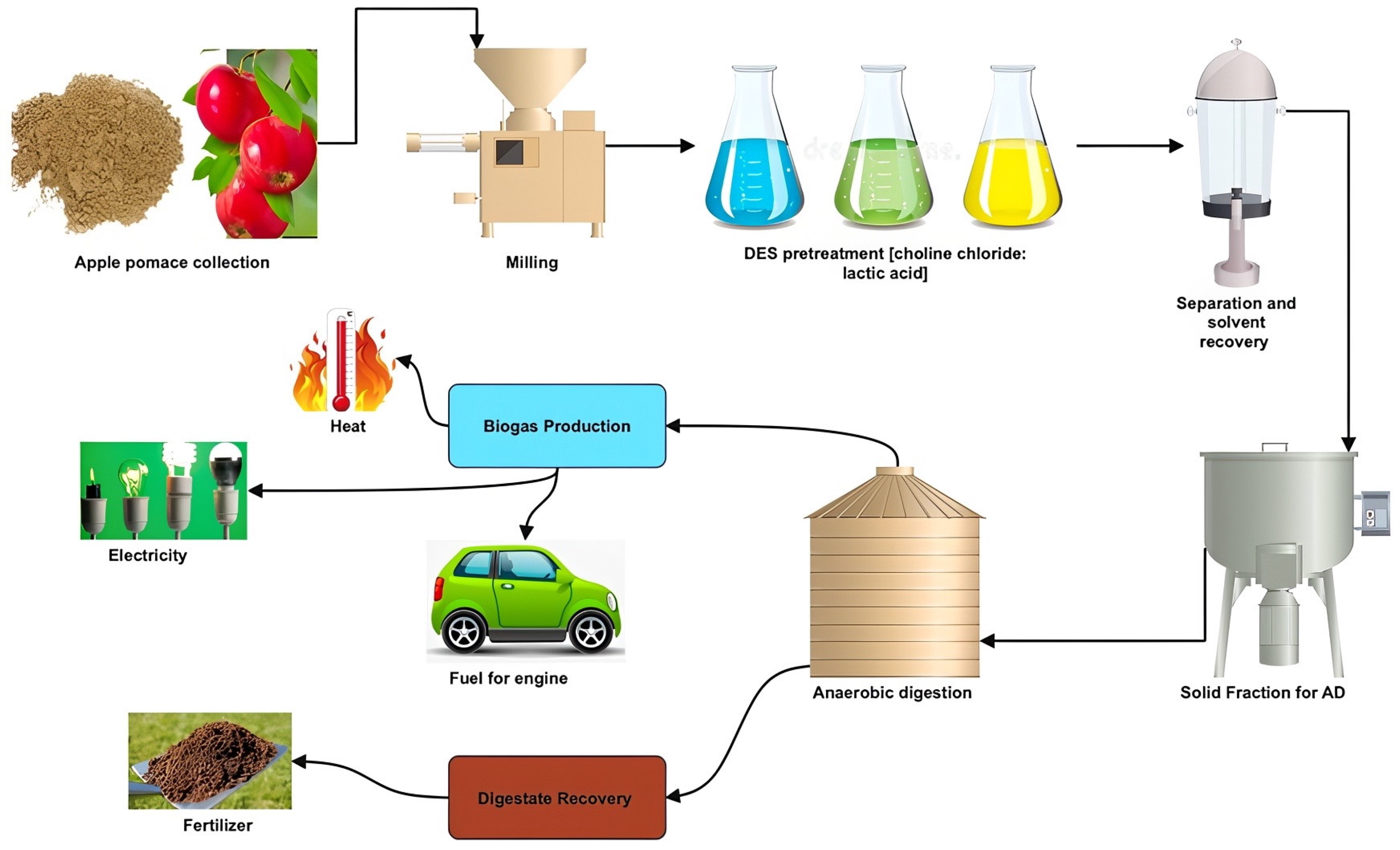

3. DES Pretreatment for Apple Pomace

3.1. Mechanistic Insights of DES Action

- Disruption of Lignin–Carbohydrate Complexes: The solvent mixture penetrates the biomass matrix, selectively breaking the ester and ether bonds, especially the crucial β-O-4 linkages, that connect lignin to hemicellulose or cellulose [18]. This disruption is essential for liberating the polysaccharide components.

- Hydrogen Bonding Interference: The abundant hydrogen-bond network in DES formulations competes with native intermolecular bonds in biomass. For instance, DESs based on choline chloride and lactic acid can form extensive hydrogen bonding, weakening the internal structure of lignocellulose, thereby reducing its crystallinity and enhancing enzyme accessibility [18].

- Selective Lignin Solubilization: DESs are particularly effective in preserving the cellulose fraction while solubilizing lignin and, to some extent, hemicellulose. This selectivity is vital for maintaining the quality of the cellulose residue, which is essential for subsequent biofuel production pathways [18,32].

3.2. Optimization Parameters for DES Pretreatment

3.3. Application to Apple Pomace

- Enhanced Cellulose Accessibility: By effectively removing lignin, DES pretreatment can expose cellulose fibers, rendering them more amenable to microbial or enzymatic attack during anaerobic digestion [18].

- Improved Sugar Yield: The cleavage of lignin and carbohydrate bonds facilitates the release of fermentable sugars, which can subsequently be converted into biofuels. Preliminary studies on other feedstocks suggest that DES pretreatment conditions can be tuned to optimize sugar conversion rates [18].

- Minimized Inhibitor Formation: DES pretreatment allows operation under relatively mild conditions, reducing the formation of degradation products often associated with harsher chemical treatments.

4. Anaerobic Digestion of Apple Pomace

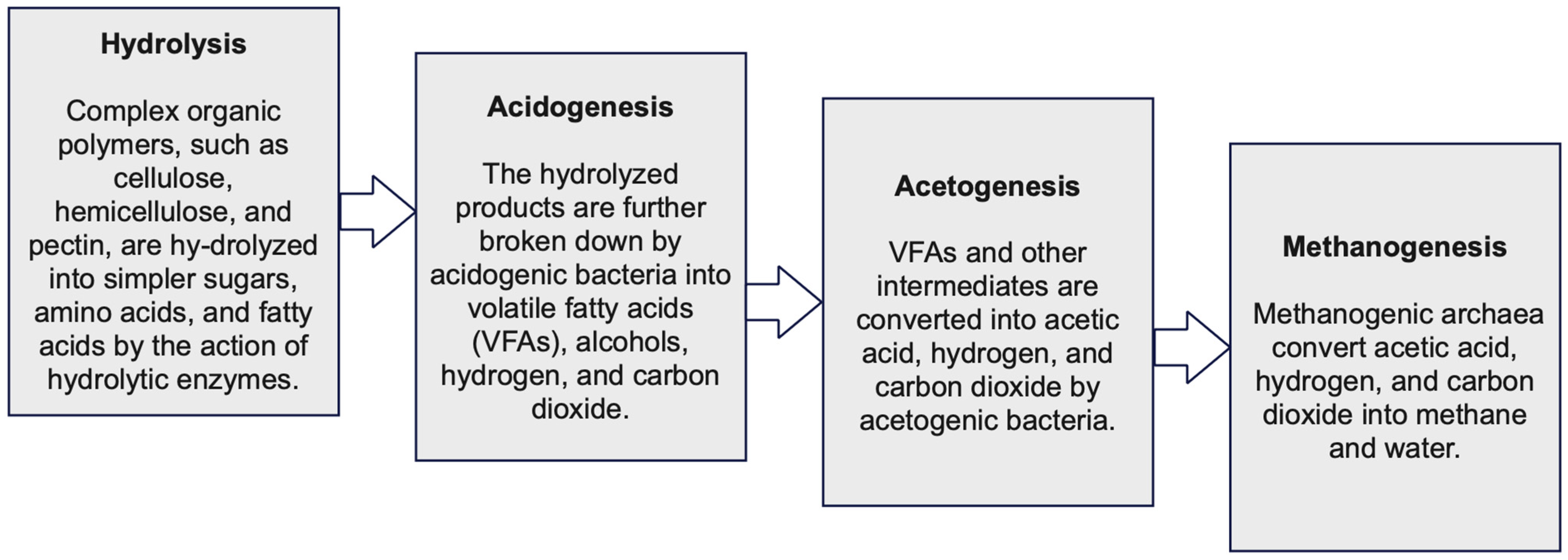

4.1. Process Overview of Anaerobic Digestion

4.2. Enhancing AD Efficiency Through Pretreatment

4.3. Potential Performance of Apple Pomace in AD

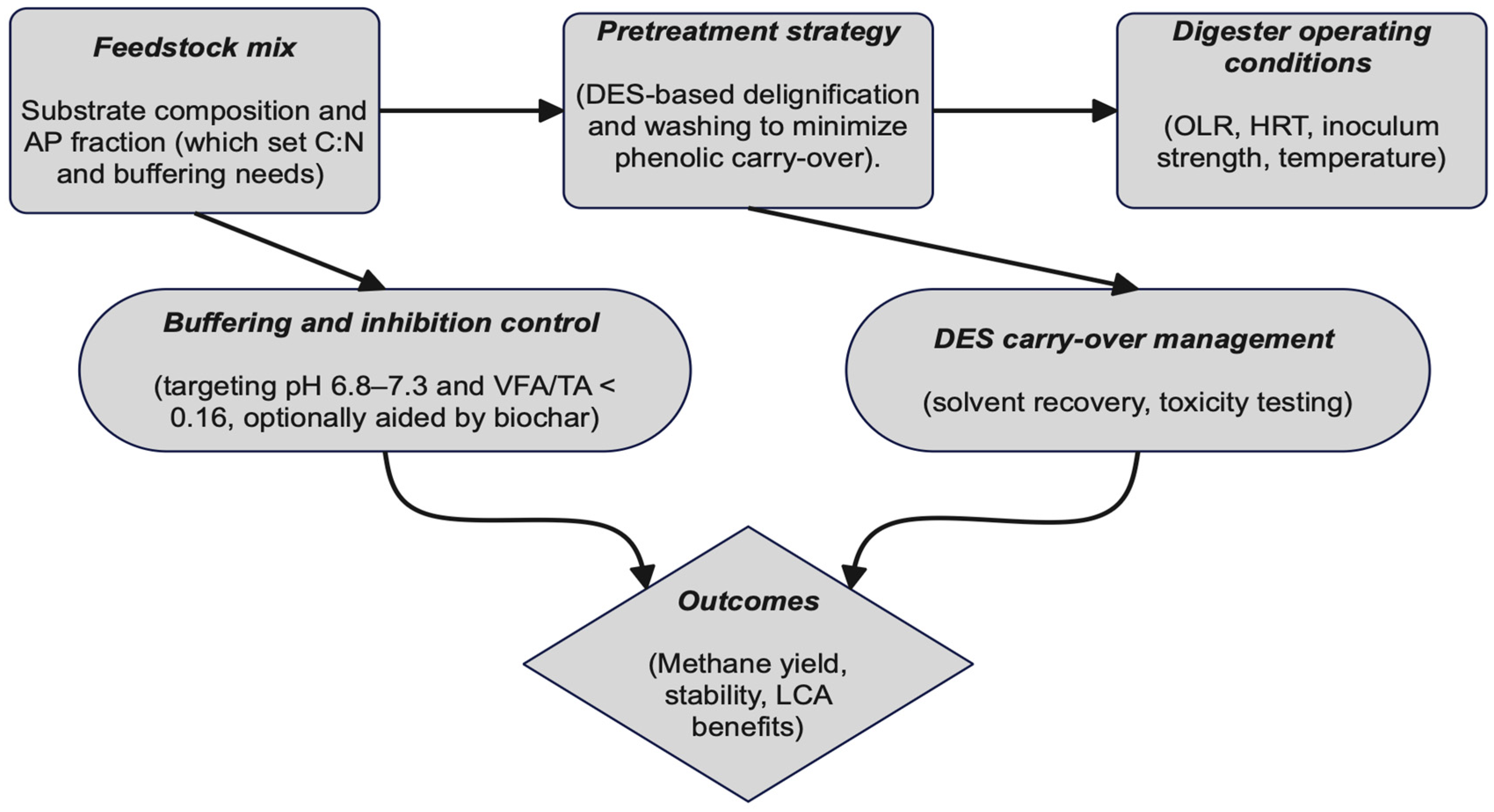

5. Integration of DES Pretreatment with Anaerobic Digestion

5.1. Proposed Process Flow for Integrated System

5.2. Critical Comparison: DES Performance for Apple Pomace vs. Woody Biomass

6. Economic and Environmental Assessment

6.1. Economic Considerations

6.2. Environmental Impact and Life Cycle Assessment

6.3. Sensitivity and Risk Analysis

7. Scaling Up and Industrial Implementation

7.1. Feedstock Logistics and Supply Chain Considerations

7.2. Integration with Existing Industrial Infrastructure

7.3. Process Intensification and Scale-Up of DES Pretreatment

7.4. Regulatory and Permitting Considerations

8. Key Challenges

9. Future Research and Directions

9.1. DES Chemistry, Solvent Recovery and Environmental Safety

9.2. Technical and Operational Challenges

9.3. Microbial Response to Pretreated Substrates

9.4. Reaction Engineering and Solid Handling

9.5. Co-Product Valorisation and Biorefinery Design

9.6. Scale-Up, CAPEX Prediction, and Investment Risk

9.7. Policy, Certification, and Cross-Sector Alignment

9.8. Standardization and Systematic Comparison Gaps

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DES | deep eutectic solvents |

| AP | apple pomace |

| AD | anaerobic digestion |

| IL | ionic liquids |

| DA | dilute acid |

| AFEX | ammonia fiber expansion |

| HBD | hydrogen bond donor |

| HBA | hydrogen bond acceptor |

| VFA | volatile fatty acids |

| BMP | biomethane potential test |

| SMY | specific methane yield |

| GPM | gas-permeable membrane |

| GWP | global warming potential |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred tank reactor |

| WAS | waste activated sludge |

| TA | total alkanity |

| OLR | organic loading rate |

| HRT | hydraulic retention time |

| TEA | techno-economic analysis |

| MESP | minimum energy selling price |

| LCA | life cycle assessment |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| OPEX | operating expenditure |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure |

References

- Gołębiewska, E.; Kalinowska, M. Agricultural Residues as a Source of Bioactive Substances—Waste Management with the Idea of Circular Economy. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zaky, A.A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Turning Apple Pomace into Value: Sustainable Recycling in Food Production—A Narrative Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Basic Path and System Construction of Agricultural Green and Low-Carbon Development with Respect to the Strategic Target of Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 516–526. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Estévez, S.; Hernández, D.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Environmental Insights of Bioethanol Production and Phenolic Compounds Extraction from Apple Pomace-Based Biorefinery. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2024, 9, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Chew, K.W.; Tan, C.H.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Chu, D.-T.; Show, P.-L. Waste to Bioenergy: A Review on the Recent Conversion Technologies. BMC Energy 2019, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millati, R.; Wikandari, R.; Ariyanto, T.; Putri, R.U.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Pretreatment Technologies for Anaerobic Digestion of Lignocelluloses and Toxic Feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 122998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinuevo-Salces, B.; Riaño, B.; Hijosa-Valsero, M.; González-García, I.; Paniagua-García, A.I.; Hernández, D.; Garita-Cambronero, J.; Díez-Antolínez, R.; García-González, M.C. Valorization of Apple Pomaces for Biofuel Production: A Biorefinery Approach. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 142, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalhor, P.; Ghandi, K. Deep Eutectic Solvents for Pretreatment, Extraction, and Catalysis of Biomass and Food Waste. Molecules 2019, 24, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaez, S.; Karimi, K.; Denayer, J.F.M.; Kumar, R. Evaluation of Apple Pomace Biochemical Transformation to Biofuels and Pectin through a Sustainable Biorefinery. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 172, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, K.O.; Ahmed, N.A.; Ogunkunle, O. Optimization of Biogas Yield from Lignocellulosic Materials with Different Pretreatment Methods: A Review. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; Xiao, L.-P.; Song, G. Unraveling the Structural Transformation of Wood Lignin during Deep Eutectic Solvent Treatment. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, I.; Riaño, B.; Molinuevo-Salces, B.; García-González, M.C. Energy and Nutrients from Apple Waste Using Anaerobic Digestion and Membrane Technology. Membranes 2022, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.M.; Ampese, L.C.; Ziero, H.D.D.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Apple Pomace Biorefinery: Integrated Approaches for the Production of Bioenergy, Biochemicals, and Value-Added Products—An Updated Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Ammar, M.; Korai, R.M.; Ahmad, N.; Ali, A.; Khalid, M.S.; Zou, D.; Li, X. Impact of C/N Ratios and Organic Loading Rates of Paper, Cardboard and Tissue Wastes in Batch and Cstr Anaerobic Digestion with Food Waste on Their Biogas Production and Digester Stability. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Optimization of Biomethanation Focusing on High Ammonia Loaded Processes. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, O.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P.; Matsakas, L. Biogas Potential of Organosolv Pretreated Wheat Straw as Mono and Co-Substrate: Substrate Synergy and Microbial Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Cheng, G.; Sathitsuksanoh, N.; Wu, D.; Varanasi, P.; George, A.; Balan, V.; Gao, X.; Kumar, R.; Dale, B.E. Comparison of Different Biomass Pretreatment Techniques and Their Impact on Chemistry and Structure. Front. Energy Res. 2015, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, H.; Raviadaran, R.; Chandran, D. Deep Eutectic Solvents for Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Towards Circular Bioeconomy. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; You, T.; Zhang, X.; Xu, F.; Wu, Y. Short-Time Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment for Enhanced Enzymatic Saccharification and Lignin Valorization. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Qiao, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, C.; Li, X. Deep Eutectic Solvent Cocktail Enhanced the Pretreatment Efficiency of Lignocellulose. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 210, 118040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borujeni, N.E.; Alavijeh, M.K.; Denayer, J.F.M.; Karimi, K. A Novel Integrated Biorefinery Approach for Apple Pomace Valorization with Significant Socioeconomic Benefits. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, P.R.; Goulart, A.K. Pretreatment Processes for Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion to Biofuels and Bioproducts. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2016, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbe, M.; Wallberg, O. Pretreatment for Biorefineries: A Review of Common Methods for Efficient Utilisation of Lignocellulosic Materials. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.R.; Padhi, R.K.; Ghosh, G. A Review on Key Pretreatment Approaches for Lignocellulosic Biomass to Produce Biofuel and Value-Added Products. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 6929–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntunka, M.G.; Khumalo, S.M.; Makhathini, T.P.; Mtsweni, S.; Tshibangu, M.M.; Bwapwa, J.K. Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Biofuel: A Systematic Review. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, W.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Show, P.-L.; Tg Ibrahim, T.N.B.; Chew, K.W.; Culaba, A.; Chang, J.-S. Pretreatment Methods for Lignocellulosic Biofuels Production: Current Advances, Challenges and Future Prospects. Biofuel Res. J. 2020, 7, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, J.; Rangarajan, V.; Rathnasamy, S.; Dey, P. Life Cycle Assessment as a Key Decision Tool for Emerging Pretreatment Technologies of Biomass-to-Biofuel: Unveiling Challenges, Advances, and Future Potential. Bioenergy Res. 2024, 17, 857–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A.; Kuligowski, K.; Świerczek, L.; Cenian, A. Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Using Physical, Thermal and Chemical Methods for Higher Yields in Bioethanol Production. Sustainability 2025, 17, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Jagtap, S.S.; Bedekar, A.A.; Bhatia, R.K.; Patel, A.K.; Pant, D.; Banu, J.R.; Rao, C.V.; Kim, Y.-G.; Yang, Y.-H. Recent Developments in Pretreatment Technologies on Lignocellulosic Biomass: Effect of Key Parameters, Technological Improvements, and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Mayer-Laigle, C.; Solhy, A.; Arancon, R.A.D.; De Vries, H.; Luque, R. Mechanical Pretreatments of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Towards Facile and Environmentally Sound Technologies for Biofuels Production. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48109–48127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y. Peroxyacetic Acid Pretreatment: A Potentially Promising Strategy Towards Lignocellulose Biorefinery. Molecules 2022, 27, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Tarhanli, I.; Owen, G.; Lee, C.S.; Senses, E.; Binner, E. Comparisons of Alkali, Organosolv and Deep Eutectic Solvent Pre-Treatments on the Physiochemical Changes and Lignin Recovery of Oak and Pine Wood. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cheng, K.; Liu, D. Organosolv Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, P.; Huijgen, W.; Bermudez, L.; Bakker, R. Literature Review of Physical and Chemical Pretreatment Processes for Lignocellulosic Biomass. 2010, pp. 1–49. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/150289 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Kumar, A.K.; Sharma, S. Recent Updates on Different Methods of Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Feedstocks: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.; Kumar, D.; Girdhar, M.; Kumar, A.; Goyal, A.; Malik, T.; Mohan, A. Strategies of Pretreatment of Feedstocks for Optimized Bioethanol Production: Distinct and Integrated Approaches. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novia, N.; Melwita, E.; Jannah, A.M.; Selpiana, S.; Yandriani, Y.; Afrah, B.D.; Rendana, M. Current advances in bioethanol synthesis from lignocellulosic biomass: Sustainable methods, technological developments, and challenges. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warade, H.; Mukwane, S.; Ansari, K.; Agrawal, D.; Asaithambi, P.; Eyvaz, M.; Yusuf, M. Enhancing Biogas Generation: A Comprehensive Analysis of Pre-Treatment Strategies for Napier Grass in Anaerobic Digestion. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kululo, W.W.; Habtu, N.G.; Abera, M.K.; Sendekie, Z.B.; Fanta, S.W.; Yemata, T.A. Advances in Various Pretreatment Strategies of Lignocellulosic Substrates for the Production of Bioethanol: A Comprehensive Review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Challenges and Future Perspectives of Promising Biotechnologies for Lignocellulosic Biorefinery. Molecules 2021, 26, 5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sui, H.; Jia, Z.; Yang, Z.; He, L.; Li, X. Recovery and Purification of Ionic Liquids from Solutions: A Review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32832–32864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłak, B.; Owczarek, K.; Namieśnik, J. Selected Issues Related to the Toxicity of Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents—A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 11975–11992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, J.; Flieger, M. Ionic Liquids Toxicity—Benefits and Threats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Reis, C.E.R.; Chandel, A.K. Key Takeaways on the Cost-Effective Production of Cellulosic Sugars at Large Scale. Processes 2024, 12, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chundawat, S.P.S.; Bals, B.; Campbell, T.; Sousa, L.; Gao, D.; Jin, M.; Eranki, P.; Garlock, R.; Teymouri, F.; Balan, V. Primer on Ammonia Fiber Expansion Pretreatment. In Aqueous Pretreatment of Plant Biomass for Biological and Chemical Conversion to Fuels and Chemicals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bals, B.; Wedding, C.; Balan, V.; Sendich, E.; Dale, B. Evaluating the Impact of Ammonia Fiber Expansion (Afex) Pretreatment Conditions on the Cost of Ethanol Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, J.; Nath, B.K.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, S.; Deka, R.C.; Baruah, D.C.; Kalita, E. Recent Trends in the Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Value-Added Products. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, W.; Kong, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, B. Techno-Economic Analysis of Bioethanol Preparation Process Via Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 172, 114036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Jin, Y.; Wu, W. Des: Their Effect on Lignin and Recycling Performance. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3241–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiin, C.L.; Lai, Z.Y.; Chin, B.L.F.; Lock, S.S.M.; Cheah, K.W.; Taylor, M.J.; Al-Gailani, A.; Kolosz, B.W.; Chan, Y.H. Green Pathways for Biomass Transformation: A Holistic Evaluation of Deep Eutectic Solvents through Life Cycle and Techno-Economic Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, P.D.; Mobley, J.K.; Tong, X.; Novak, B.; Stevens, J.; Moldovan, D.; Shi, J.; Boldor, D. Rapid Microwave-Assisted Biomass Delignification and Lignin Depolymerization in Deep Eutectic Solvents. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 196, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Chong, G.; Guo, H. Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment and Green Separation of Lignocellulose. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, S.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Rodrigues, M.; Fernandes, C.; Mendes, C.V.T.; Carvalho, M.G.V.S.; Alves, L.; Medronho, B.; Rasteiro, M.d.G. Enhancing Cellulose and Lignin Fractionation from Acacia Wood: Optimized Parameters Using a Deep Eutectic Solvent System and Solvent Recovery. Molecules 2024, 29, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.-J.; Wen, J.-L.; Mei, Q.-Q.; Chen, X.; Sun, D.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Sun, R.-C. Facile Fractionation of Lignocelluloses by Biomass-Derived Deep Eutectic Solvent (Des) Pretreatment for Cellulose Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Lignin Valorization. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czubaszek, R.; Wysocka-Czubaszek, A.; Tyborowski, R. Methane Production Potential from Apple Pomace, Cabbage Leaves, Pumpkin Residue and Walnut Husks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, B.J.; Nakhate, S.P.; Gupta, R.K.; Chavan, A.R.; Singh, A.K.; Khardenavis, A.A.; Purohit, H.J. A Comprehensive Review on the Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Wastes for Improved Biogas Production by Anaerobic Digestion. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 3429–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, F. An Introduction to Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Wastes. Remade Scotl. 2003, 379, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, A.H.; Tao, L. Economic Perspectives of Biogas Production Via Anaerobic Digestion. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atelge, M.R.; Krisa, D.; Kumar, G.; Eskicioglu, C.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chang, S.W.; Atabani, A.E.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Unalan, S. Biogas Production from Organic Waste: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 1019–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mes, T.Z.D.; Stams, A.J.M.; Reith, J.H.; Zeeman, G. Methane Production by Anaerobic Digestion of Wastewater and Solid Wastes. Bio-Methane Bio-Hydrog. 2003, 2003, 58–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Biogas Production and Applications in the Sustainable Energy Transition. J. Energy 2022, 2022, 8750221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Sallis, P.; Uyanik, S. Anaerobic Treatment Processes. In Handbook of Water and Wastewater Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.M.; Wright, M.M. Anaerobic Digestion Fundamentals, Challenges, and Technological Advances. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 8, 2819–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, K.F.; Okolie, J.A. A Review of Biochemical Process of Anaerobic Digestion. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampese, L.C.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Di Domenico Ziero, H.; Costa, J.M.; Martins, G.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Valorization of Apple Pomace for Biogas Production: A Leading Anaerobic Biorefinery Approach for a Circular Bioeconomy. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 14843–14857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q. Potential of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Acidic Fruit Processing Waste and Waste-Activated Sludge for Biogas Production. Green Process. Synth. 2022, 11, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, H.; He, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, L. A Review of Biochar in Anaerobic Digestion to Improve Biogas Production: Performances, Mechanisms and Economic Assessments. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; John, A.J.; Samuel, M.S.; Ethiraj, S. Recent Developments and Emerging Methodologies in the Pre-Treatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 11, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.; Pinilla, F.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Aburto-Hole, J.; Díaz, J.; Quijano, G.; González-García, S.; Tenreiro, C. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Agro-Industrial Waste Mixtures for Biogas Production: An Energetically Sustainable Solution. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, L.G.; Verma, P. Harnessing Carbon Potential of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Advances in Pretreatments, Applications, and the Transformative Role of Machine Learning in Biorefineries. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampese, L.C.; Di Domenico Ziero, H.; Velasquez-Pinas, J.A.; Martins, G.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Turning Agroindustrial Waste into Energy: Technoeconomic Insights from the Theoretical Anaerobic Digestion of Apple and Orange Byproducts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 8152–8163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. PE/48/2018/REV/1. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2001/oj (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) Program: Standards for 2023–2025. Federal Register 88, No. 133 (July 12, 2023): 44468–44593. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/07/12/2023-13462/renewable-fuel-standard-rfs-program-standards-for-2023-2025-and-other-changes (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Department of Minerals and Energy. Biofuels Industrial Strategy of the Republic of South Africa. Department of Minerals and Energy. 2007. Available online: www.dmre.gov.za (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- ISO 14067; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

| Particle Size | Application | Rationale | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| <2 mm (2000 μm) | General recommendation for DES pretreatment | Balance between surface area, mass transfer, and energy consumption | [18,32] |

| 0.5–2 mm (500–2000 μm) | Optimal for most lignocellulosic biomass | Maximizes DES penetration without excessive energy input | [17] |

| 0.25–0.5 mm (250–500 μm) | Fine milling for enhanced delignification | Provides maximum surface area; used in research studies | [30] |

| <0.18 mm (180 μm) | Ultra-fine milling | Research-scale only; excessive energy consumption at the industrial scale | [30] |

| Pretreatment Method | Lignin Removal Efficiency | Energy Consumption | Process Time | Notable Advantages | Critical Limitations | Economic Viability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA | Moderate to High (30–50%) | Moderate (15–25 MJ/kg) | >1–2 h | Solubilizes hemicellulose effectively; proven at an industrial scale | High inhibitor formation (furfural 1–3 g/L, HMF 0.5–2 g/L); requires corrosion-resistant equipment (+40–60% CAPEX); poor lignin removal; acidic waste disposal | Moderate ($2500–3000/ton product) | [17] |

| IL | High (60–90%) | High (25–40 MJ/kg including recovery) | Variable (1–24 h) | Decreases cellulose crystallinity dramatically; near-complete dissolution is possible | Prohibitive cost ($5–50/kg); significant ecotoxicity (LC50 10–1000 mg/L); residual IL inhibits enzymes/microbes; requires >98% recovery for viability | Poor (>$5000/ton product unless >98% recovery) | [17,41] |

| AFEX | Moderate (10–30%) | Moderate (20–30 MJ/kg) | Variable (5–60 min) | Creates nanoporous structures; no inhibitor formation; effective for low-lignin biomass | Complex NH3 recovery (90–98% needed); limited effectiveness for high-lignin feedstocks; safety risks with anhydrous NH3; high-pressure equipment required | Moderate ($2400–2800/ton product) | [17,46] |

| Alkaline | High (50–80%) | High (30–45 MJ/kg) | Long (hours to days) | Selective lignin removal; minimal carbohydrate degradation | Extended processing times; high chemical consumption (50–200 kg NaOH/ton); costly alkali recovery (25–35% of costs); high-salinity waste | Moderate to Poor ($2400–3200/ton product) | [32,35] |

| DES (acidic) | High (66–79% delignification) | Low (5–10 MJ/kg, 1/5–1/8 of other methods) | Short (<30–60 min) | Low toxicity (LC50 > 1000 mg/L); biodegradable; recyclable (>90% potential); low equipment costs; selective delignification | Moderate inhibitor formation (2–4 g/L phenolics); viscosity management required; solvent recovery validation needed; formulation-dependent performance | Promising ($2100–2500/ton with >90% recovery) | [32,48] |

| DES (neutral) | Moderate (40–55%) | Low (5–10 MJ/kg) | Longer (2–4 h) | Minimal inhibitor formation (0.5–1.5 g/L); cleaner hydrolysates; better enzyme compatibility | Lower delignification efficiency; longer processing times; requires optimization for high-lignin feedstocks | Moderate (requires further validation) | [18,52] |

| Pretreatment Method | Lignin Removal (%) | Experimental Conditions | Methane Yield (mL CH4/g VS or NL CH4/kg VS) | Improvement vs. Untreated | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Apple Pomace | Not Available (N/A) | Baseline | ~230 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | Baseline (0%) | [55] |

| Acidic DES (ChCl:Lactic Acid 1:2) | 66–79% | 120 °C, 30 min | 310–360 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +35–55% | [9,17,32] |

| Neutral DES (ChCl:Glycerol) | 40–55% | 100–120 °C, 1–2 h | 265–290 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +15–25% | [17,18] |

| DES (various mild formulations) | 45–60% | 80–120 °C, variable | >120 mL g−1 VS | ~30–50% | [9,52] |

| Dilute Acid (H2SO4 1–2%) | 30–50% | 160–200 °C, 1–2 h | 250–290 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +10–25% | [17,56] |

| Alkaline (NaOH 2–10%) | 50–80% | 80–120 °C, hours to days | 280–320 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +20–40% | [35,56] |

| Ionic Liquids | 60–90% | 80–120 °C, 1–24 h | 300–350 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +30–50% | [17] |

| AFEX (Liquid NH3) | 10–30% | 60–100 °C, 5–60 min | 260–300 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +15–30% | [17,45] |

| Thermal Pretreatment | 15–35% | 150–200 °C, 30–60 min | 250–280 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +10–20% | [56] |

| Enzymatic Pretreatment | 20–40% | 50 °C, 24–48 h | 270–300 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +15–30% | [56] |

| Organosolv (Ethanol/acid) | 65–95% | 170–200 °C, 1–3 h | 290–340 NL CH4 kg−1 VS | +25–45% | [33] |

| Reference | Reactor Type | Temperature | Substrate Strategy | Pretreatment (If Any) | Methane Yield/Biogas Rate | Stability Indicators (pH, VFA, OLR, C:N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [55] | Batch BMP | Mesophilic (~38 °C) | Apple pomace (mono-digestion) | None | ≈232 NL CH4 kg−1 VS (SMY) | Lag ≈ 4 d; T95 ≈ 20 d; low NH3/H2S; C:N > ~24:1 |

| [12] | Batch; nutrient recovery (GPM) | Mesophilic | Co-digestion: swine manure + AP (0–30% VS) | None | AP 7.5–15%: yields comparable to manure alone; 30% AP reduced stability | Stable at ≤15% AP; nutrient (NH4+) recovered as (NH4)2SO4 |

| [66] | Continuous co-digestion (CSTR) | Mesophilic | Acidic fruit-processing waste + WAS (AP-analogous) | None | ≈350 mL CH4 g−1 VS (typical) | pH 6.8–7.3; VFA/TA < 0.16; buffered with sludge |

| [4] | Scenario/LCA (AD + compost) | — | Apple pomace management (AD vs. composting) | — | AD scenario preferred on GHG footprint (contextual) | Benefits when nutrient/energy recovery is included |

| [9] | Review + experimental notes | — | AP biorefinery (energy + pectin) | Hydrolysis | >120 mL g−1 VS for mild pretreatment cases; severe conditions lower | Emphasizes inhibitor control; staged product recovery |

| [67] | Review (biochar in AD) | — | Lignocellulosic residues (incl. fruit wastes) | Biochar amendment (process aid) | Up to ~10–30% improvements reported across cases | Enhanced buffering, DIET facilitation, VFA mitigation |

| Metric | DES Pretreatment + AD | Conventional Pretreatment | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | Low (1/5–1/8 relative) | Moderate to High | DES operates at a lower energy input | [32] |

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GWP) | Lower (approx. 0.025–0.026 kg CO2-eq/MJ) | Higher (e.g., 0.04786 kg CO2-eq/MJ for alkali) [68] | Lower emissions due to reduced energy and solvent reuse | [68] |

| Minimum Energy Selling Price | Potentially competitive (~$2128.1/ton) | Higher due to extended process time and recovery issues | DES shows promising upfront economic feasibility | [48] |

| Waste Valorization | High (digestate reuse) | Moderate | Integration with AD converts waste to biogas and fertilizer | [48] |

| Model | Opportunity | Limitation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-site bolt-on biorefinery | Heat, utilities and wastewater can be shared with the apple-processing plant | Requires space and CAPEX approval from the food producer | [4] |

| Regional hub | Higher economies of scale via multi-supplier aggregation | Requires logistics contracts and feedstock guarantees | [4] |

| Third-party energy operator | Processor avoids energy-sector risk; income via gate fee | Revenue from energy shared; dependence on policy incentives | [4] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makhathini, T.P.; Ntunka, M.G. Deep Eutectic Solvents and Anaerobic Digestion for Apple Pomace Valorization: A Critical Review of Integration Strategies for Low-Carbon Biofuel Production. Energies 2025, 18, 6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246434

Makhathini TP, Ntunka MG. Deep Eutectic Solvents and Anaerobic Digestion for Apple Pomace Valorization: A Critical Review of Integration Strategies for Low-Carbon Biofuel Production. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246434

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakhathini, Thobeka Pearl, and Mbuyu Germain Ntunka. 2025. "Deep Eutectic Solvents and Anaerobic Digestion for Apple Pomace Valorization: A Critical Review of Integration Strategies for Low-Carbon Biofuel Production" Energies 18, no. 24: 6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246434

APA StyleMakhathini, T. P., & Ntunka, M. G. (2025). Deep Eutectic Solvents and Anaerobic Digestion for Apple Pomace Valorization: A Critical Review of Integration Strategies for Low-Carbon Biofuel Production. Energies, 18(24), 6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246434