1. Introduction

The accelerating global urgency to mitigate climate change, ensure energy security, and achieve climate-neutral cities by 2050 has intensified the interest in Positive Energy Districts (PEDs) as a strategic solution at the urban scale. Actions related to the transition of urban energy systems need to be based on solid decision-making foundations, which require robust concepts, methods and modeling tools to represent cities’ energy systems and to support the low-impact design process and the development of decarbonization strategies [

1,

2].

PEDs are defined as urban districts that have an annual net-positive energy balance, meaning they produce more renewable energy than they consume through the integration of local energy production, storage, demand-side flexibility, and smart energy management systems [

3]. They are not merely technical constructs but complex socio-technical ecosystems where energy, governance, and spatial planning intersect [

4]. In the European context, PEDs are at the forefront of the EU’s long-term strategy for sustainable urban transformation, as promoted through initiatives such as Horizon Europe, SET Plan, and the 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030 Mission. These initiatives underscore the need for systemic, technical, institutional, and behavioral innovation across multiple levels of governance [

5,

6]. PEDs are no longer considered pilot experiments; they are being institutionalized as essential infrastructure for next-generation cities [

4]. From a technical standpoint, achieving energy positivity requires not only maximizing local renewable generation, typically from photovoltaic (PV) systems, solar thermal, and biomass, but also addressing challenges related to building performance, heating and cooling systems, district heating networks, and thermal storage.

Based on these premises, Yang et al. [

3] present a transformation roadmap that emphasizes two main phases: first, optimizing endogenous resources and digital infrastructures; second, reconfiguring financial models and participatory planning processes to align local stakeholders. However, despite these frameworks, real-world implementation is often constrained by fragmented urban infrastructures, rigid regulatory frameworks, and insufficient data integration [

7,

8,

9]. Recent reviews, such as that by Rehman and Hasan [

10], demonstrate that PED research is rapidly evolving, with growing interest in advanced technologies like hybrid PV-thermal systems, smart forecasting, multi-energy hubs, and real-time control algorithms. These systems require robust simulation environments and comprehensive energy modeling tools. A notable example is the study by Kayayan et al. in the Swedish context [

11], where a bottom-up urban energy model based on EnergyPlus was used to simulate district-wide energy demand and evaluate the contribution of heat pumps, solar PV, and district heating return-flow recovery. Their findings reveal that, even under optimized conditions, it is difficult to meet PED energy balance goals due to climate-related constraints and system inefficiencies [

11,

12,

13]. In parallel, there is growing recognition that environmental and social dimensions must be structurally integrated into PED design. Volpe et al. [

4] argue that traditional energy performance metrics are insufficient without a complementary Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) that considers land use, material cycles, emissions, and biodiversity impacts. Moreover, emerging frameworks such as that by Natanian et al. [

6] propose a holistic evaluation approach that goes beyond kilowatt-hours and CO

2 savings, incorporating factors like social equity, citizen engagement, and adaptive governance. Furthermore, issues such as energy poverty, urban inequality, and citizen participation are increasingly central to the PED discourse [

5]. PEDs must evolve from technology-driven experiments to community-oriented systems, promoting inclusive and just transitions. Finally, the scalability and replicability of PEDs across diverse urban contexts require the development of common standards, open datasets, and multi-level governance mechanisms. The literature shows that no universal solution exists; instead, PEDs must be context-sensitive, adapting to local climatic, infrastructural, regulatory, and socio-economic conditions [

11]. In summary, the transition toward PEDs is not merely a technical challenge, but a multidimensional process that intertwines engineering innovation with environmental ethics and participatory urban planning. Achieving widespread adoption of PEDs will require a profound integration of multi-vector energy systems, including electricity, heat, mobility, and storage, alongside the deployment of high-fidelity simulation tools capable of assessing both real-time and long-term performance. Furthermore, it demands the systematic inclusion of environmental and social impact indicators in the planning process, as well as strong collaboration among municipalities, urban planners, utility companies, citizens, and technology providers. Only through this comprehensive and integrated approach can PEDs emerge as a truly transformative force, shaping the sustainable, resilient, and climate-neutral cities of the future.

Early research on energy efficiency mainly focused on the scale of individual buildings, particularly Net or Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB or nZEB). However, in 2015, the European FP7 project “Next Buildings under the Smart Cities Marketplace” introduced the concept of the Positive Energy Block (PEB), initially defined to describe net-zero energy buildings [

14,

15]. Over time, attention shifted from single buildings to a more integrated approach that includes urban planning and the built environment PEDs emerged by overcoming the limitations of the original PEB concept, expanding the focus to the district scale. This broader perspective enables the assessment of energy efficiency and emissions across an entire district rather than isolated buildings, promoting more comprehensive and sustainable solutions [

16]. A key tool in the design and evaluation of PEDs is Urban Building Energy Modeling (UBEM), highlighted by Wang et al. (2025) [

17] as essential for developing low-carbon, green cities. Morales et al. and Li et al. [

18,

19]. further explored how integrating urban and environmental factors into PEDs enhances this approach. By incorporating microclimate data and climate change scenarios, UBEM significantly improves performance analysis, enabling new thermal comfort indicators and advanced models for multi-zone buildings, vegetation, and longwave radiation. This leads to improved indoor comfort and climate adaptability. Despite these advances, defining PED boundaries remains a practical challenge. Various studies have proposed operational definitions, categorizing system boundaries as geographic, functional, and virtual. Indeed, it is demonstrated that specific geographical, climatic and economic conditions, and particularly the energy mix, vary significantly from country to country, influencing the procedures for determining a PED [

20,

21]

Based on these classifications, four PED types—Diamond, Platinum, Gold, and Silver—were initially proposed, primarily in internal documents until 2019 [

22]. From May 2019, however, the terminology was revised to adopt clearer categories: autonomous PEDs, dynamic PEDs, and virtual PEDs, with Pre-PEDs mentioned less frequently [

23]. These practical definitions were further refined by Guarino et al. (2023) [

24] and Lindholm et al. (2021) [

25], contributing to ongoing debates. In summary, autonomous PEDs are districts generating all their energy from on-site renewable sources without importing energy, though they may export surplus. Dynamic PEDs produce more renewable energy locally than their annual demand and can connect to external grids, collaborating with other PEDs [

25]. Virtual PEDs combine on-site and off-site renewable systems, with total energy production exceeding annual consumption. The key difference between autonomous and dynamic PEDs lies in their energy boundaries: autonomous PEDs are fully self-sufficient and confined, while dynamic PEDs may import energy as long as the annual balance remains positive. Virtual PEDs transcend physical boundaries by blending multiple sources for greater energy use and storage flexibility. Achieving PED status is complex, requiring attention to energy efficiency, flexibility, environmental and social sustainability, and economic feasibility [

26].

Given the multidimensional nature of these criteria, an integrated, multidisciplinary approach is essential. Multi-Attribute Decision-Making (MADM) methods provide an effective framework to evaluate these diverse factors and their interactions [

27]. For example, Laguna et al. (2022) [

28] applied the Weighted Sum Method (WSM) to evaluate renovation strategies aimed at transforming a rural building into a nearly zero-energy building. Alternatives were assessed based on greenhouse gas emission reductions, economic profitability, occupant comfort, resource depletion, and human health; for example, Chacón et al. (2022) [

29] evaluated and compared different renovation strategies with dynamic simulation for urbanization in the Herrera province of Panama to achieve a Net Zero Energy District (NZED).

Similarly, Szulgowska-Zgrzywa et al. (2022) [

30] used WSM to perform a multi-criteria assessment of fifteen Polish homes, considering environmental, energy, indoor environment, and economic attributes. Finally, Shi et al. (2023) [

31] conducted a comparative evaluation of retrofit strategies for a hospital ward in China using the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method. Their analysis covered technical, economic, and thermal comfort factors, identifying external wall insulation, green roofs, and window replacement as the most effective interventions.

Decision-making must consider spatial constraints, heterogeneity, and uncertainty in socioeconomic and technological development trajectories. Few modeling approaches are holistic enough to support such complex planning needs on their own, and combinations of modeling tools are often applied on a case-by-case basis. For example, the Urban Energy System Modeling Framework (UESMF) combines City Energy Analyst (CEA), MAED-City, and MESSAGEix, leveraging their respective strengths. However, the framework has several limitations and potential shortcomings, such as the definition of generalizable and replicable clustering criteria [

32].

The study proposes the energy analysis of two urban areas in Italy and their potential transformation into PEDs. In particular, the energy performance of two neighborhoods in the city of Rome is analyzed: Testaccio and Valco San Paolo. Thanks to a careful census of the thermophysical and energy data of these two areas, it was possible to analyze both real scenarios that represent the current state of the two Roman neighborhoods and optimized scenarios in the perspective of PED and therefore evaluate the potential transformation of real urban areas into PED, the efforts and weaknesses to overcome. Furthermore, the possible replicability of the actions, in similar contexts, has allowed us to identify a procedure that, in the preliminary phase, can be followed by an energy planner.

To develop this analysis, the CEA tool [

33] was adopted; it is an open-source urban building energy modeling (UBEM) platform for designing low-carbon, high-efficiency cities; simulates urban design and energy systems engineering knowledge, allowing for the study of the effects and synergies of urban design scenarios and energy infrastructure plans. As indicated in [

34,

35,

36], this tool has been considered suitable for assisting urban planning authorities in identifying design and engineering options to enhance the performance of their neighborhoods and urban districts. Finally, a SWOT analysis validates the methodology’s replicability while emphasizing challenges such as data accessibility and interpretation.

4. Energy Simulation Model

The models for the Testaccio and Valco San Paolo districts were constructed with detailed input data reflecting building characteristics, occupancy patterns, and local climatic conditions. However, to ensure that these models provide meaningful and accurate insights, a rigorous validation and calibration process is essential. This process involves comparing simulated outputs with real-world data to identify and correct any discrepancies, thereby improving the fidelity of the models.

The validation and calibration were conducted using a combination of thermophysical parameters and actual consumption data retrieved from utility bills. This dual approach allowed for a comprehensive verification of the models, covering both the physical properties of the building stock and the real energy usage patterns within the neighborhoods. By calibrating the models to reflect observed electricity consumption and production, the simulations can reliably reproduce the temporal dynamics of energy flows, enhancing their predictive power for scenario analysis. Moreover, the calibration process took into account the existing energy generation technologies and their deployment within the districts, ensuring that both the ante opera (pre-intervention) and the final (post-intervention) states are realistically represented. More in detail, the electricity consumption data were collected over a two-year period and aggregated by end-use category. Building geometry and stratigraphy were derived from previous studies and from the TABULA project database [

18], which provides typological information on the Italian residential stock. System data were completed using standardized assumptions where specific technical details were missing. The integration of heterogeneous data sources allowed the creation of a reliable and representative digital model for both districts. Thanks to the use of the CEA platform [

27], the study conducted detailed simulations of the Testaccio and Valco San Paolo neighborhoods. The following section presents in detail the model validation and calibration procedure specifically applied to the Testaccio district, highlighting the methodologies used and the main findings.

4.1. Model Validation and Calibration—Testaccio District

Model validation was performed by comparing the electricity demand obtained from the simulation with the actual data derived from the utility bills of the neighborhood with data obtained from the buildings’ energy performance certificates. This comparison allowed a precise calibration of the model, ensuring a realistic representation of the energy behavior of the neighborhood. The validity of the data was ensured by comparing the producibility data with those of PV systems located in Rome, but outside the Testaccio district. This condition allows us to extend the results obtained to similar contexts, guaranteeing the validity of the methodological proposal.

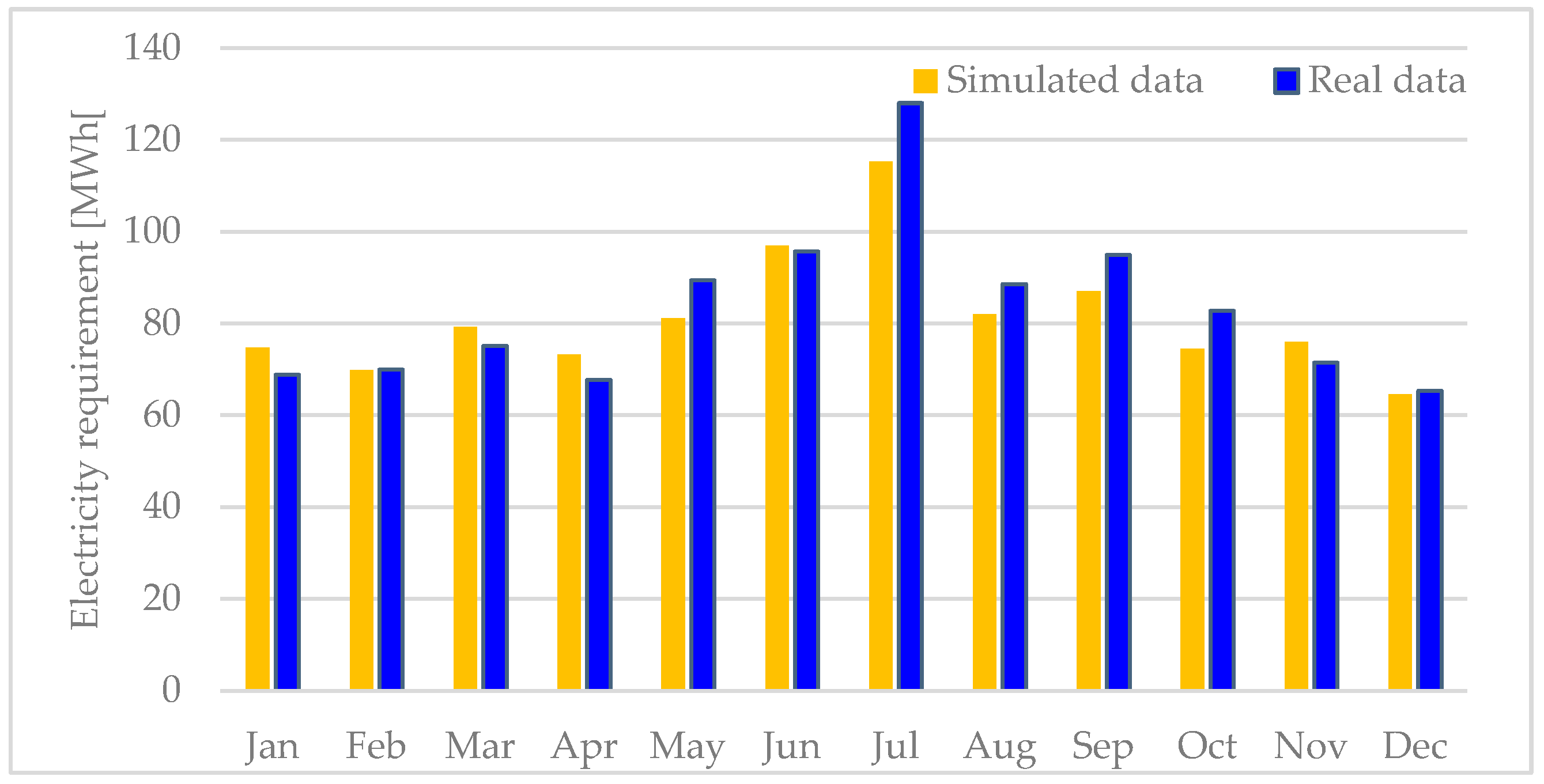

Figure 4 illustrates the monthly trend of electricity demand, comparing the values obtained from the dynamic simulation with the actual data derived from the district’s utility bills. The analysis shows that for each month, the percentage difference between the two values is less than the limit value of ±10% [

44]. The highest percentage differences are observed in the months of December and February, during which the actual consumption is lower than the simulated values. In the residential buildings, calibration was carried out by comparing the simulated Energy Performance values (EP) with reference values derived from scientific publications related to the TABULA project [

33]. For each building typology within the district, the TABULA archetype with the most similar envelope and system characteristics was selected as the reference model. Since TABULA data refer to buildings located in Turin, the values were normalized to account for the HDD of Rome. Additional adjustments were made based on the system efficiency (where different from the TABULA reference) and the surface-to-volume (S/V) ratio.

Table 5 presents all data used to normalize the Heating Energy needs in Rome for two residential Archetypes.

Figure 5 shows the thermal energy needs trends of Archetypes 1 and 5, respectively, distinct for monthly requirements for heating and DHW services.

Archetype 1 is characterized by 39.71 kWh/m2year of energy needs for heating and 8.68 kWh/m2year for DHW production, for a total energy consumption of 48.39 kWh/m2year. Archetype 1 is characterized by 39.71 kWh/m2year of energy needs for heating and 8.68 kWh/m2year for DHW production, for a total energy consumption of 48.39 kWh/m2year, while Archetype 5 has energy needs of 44.16 kWh/m2year for heating and 8.67 kWh/m2year for DHW production, for a total energy consumption of 52.81 kWh/m2year. This calibration process ensured that the percentage deviation between the simulated and reference EP values remained below 10%. Indeed, for the residential buildings in the Testaccio district, the thermal energy calibration shows percentage differences of −9.68% for Archetype 1 and −6.87% for Archetype

Based on the same approach it was possible to validate the simulation models of the residential archetype of Valco San Paolo. In the following

Table 6 all are collected normalized (considering the TABULA data in Tourin and normalized for Rome) and simulated data related to the total energy needs in the heating period.

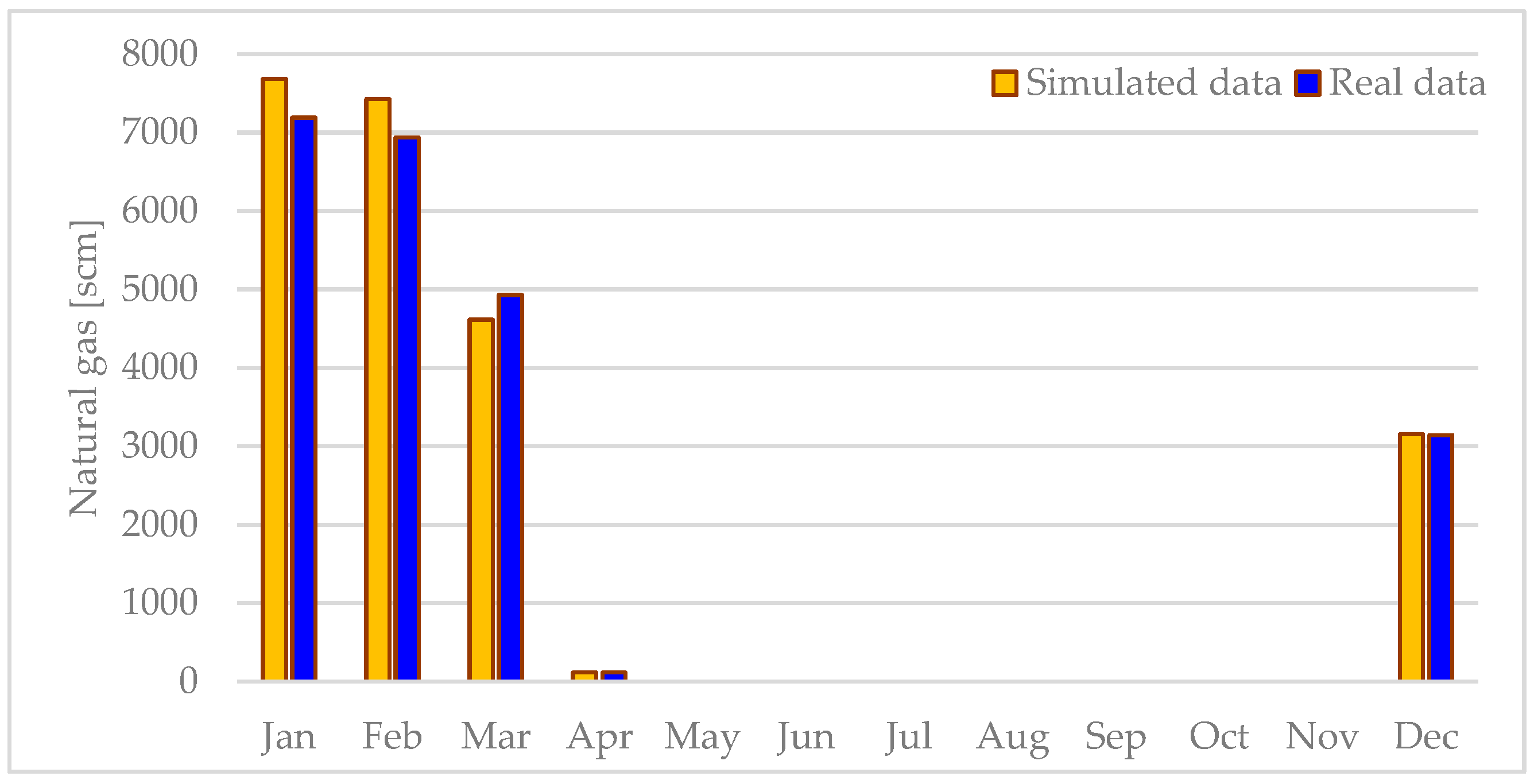

In this case the thermal energy calibration for the residential archetypes exhibits percentage differences ranging from 13% to 0.04%; most archetypes show deviations within ±5%. Furthermore, for university buildings, based on electricity and natural gas consumption data collected from utility bills, calibration was performed for all buildings monthly. In this case, the percentage deviation between simulated and actual values, for both thermal and electrical energy, remained less than 10%. As an example, the calibration results of the MAR446 building in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are shown.

The monthly percentage variations between simulated and actual electricity consumption for building MAR446 range from −9.90% (July and October) to 8.94% (April). Negative variations indicate months where the simulation overestimates consumption, while positive values correspond to underestimations. The smallest deviations occur in February (−0.09%) and December (−1.04%), showing excellent model accuracy during these periods. The largest discrepancies are observed in July (−9.90%) and October (−9.90%), both nearing the ±10% tolerance limit. The total annual variation of −2.23% reflects a slight overestimation by the model but confirms the overall reliability of the calibration. The percentage variations between simulated and actual natural gas consumption for building MAR446 range from a maximum of 7.08% (February) to a minimum of −6.40% (March). Overall, the total annual variation is 1.49%, demonstrating good agreement between simulated and measured data and confirming the reliability of the thermal calibration.

4.2. Existing District Performance Assessment

The results of the existing district performance assessment for both Testaccio and Valco San Paolo are presented in

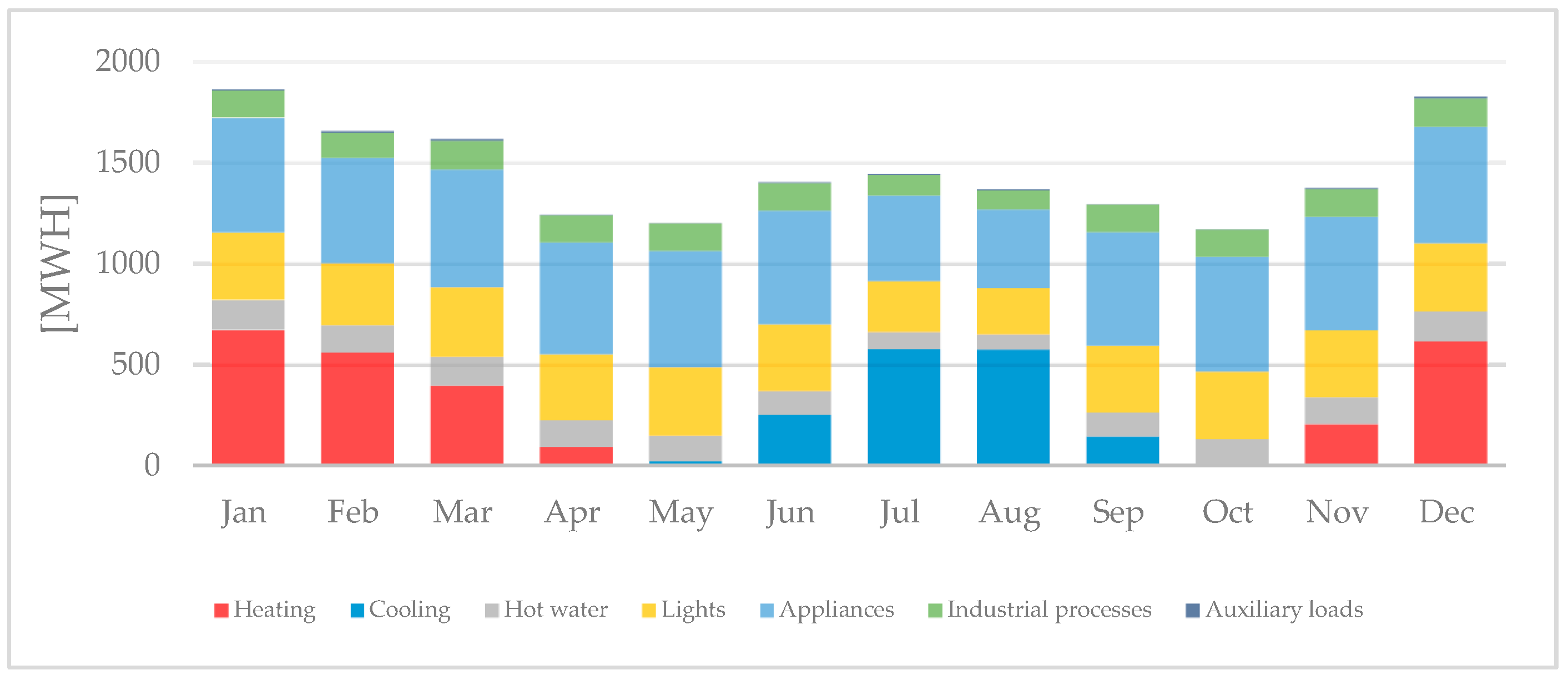

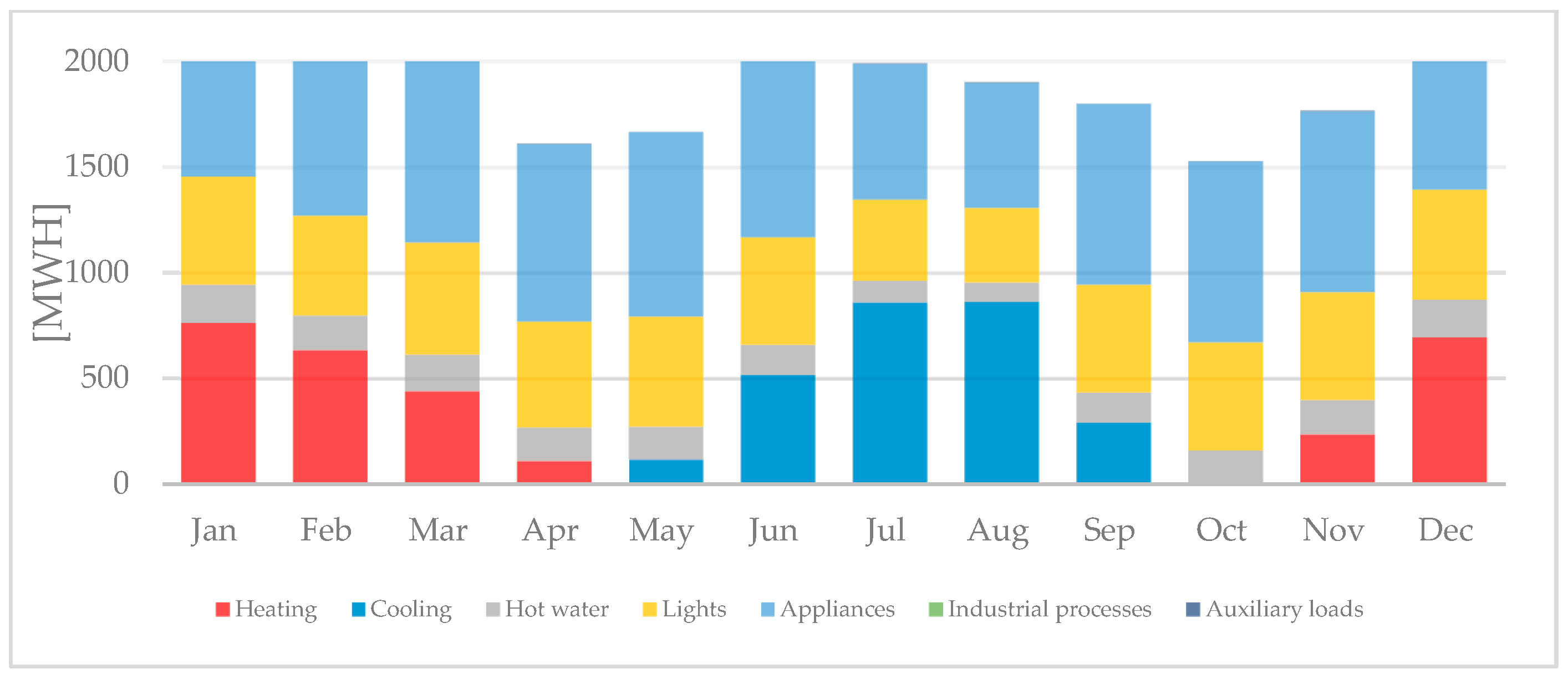

Figure 8 showing the electricity demand of each district, broken down by load type.

In Testaccio, electricity demand exhibits a clear seasonal pattern, with a pronounced winter peak. This is primarily driven by electric heating requirements, which are particularly high in January, February, and December. While residential buildings in the district do not use electricity for space heating, non-residential buildings do. Out of the 150 buildings analyzed, 59 are non-residential and rely on electric heating systems. This relatively large share significantly contributes to the elevated winter consumption. Cooling demand, by contrast, becomes relevant during the summer, especially in July and August, but remains lower than heating throughout the year. Other end uses, including hot water production, lighting, and appliances, show relatively stable consumption across all months. The total annual electricity demand in Testaccio amounts to 23,187.32 MWh. In Valco San Paolo (

Figure 6), a markedly different consumption pattern is observed. Although the district comprises a larger number of buildings (273 in total), only 31 are non-residential and equipped with electric heating. As a result, the winter peak is considerably less pronounced than in Testaccio. Instead, cooling loads dominate the profile, with a distinct peak occurring in July and August. This summer demand surge drives the total annual electricity consumption to 29,672.38 MWh. Like Testaccio, base loads such as hot water, lighting, and appliances remain relatively constant over the year, though their relative share decreases during summer months due to the prominence of cooling.

This comparison underscores the influence of building typology and heating system configuration on district-level energy demand profiles. In Testaccio, the higher proportion of non-residential buildings using electric heating results in a winter-dominated load profile. Conversely, in Valco San Paolo, the reduced presence of such buildings and the larger building stock overall shift the dominant demand toward the summer, mainly due to cooling needs. Both districts currently rely on natural gas for heating residential buildings. The simulations estimate a thermal energy demand of approximately 2,837,500 Sm3 of natural gas per year for Testaccio and 3,885,301 Sm3 per year for Valco San Paolo. In both districts, significant contributors to electricity demand include hot water production, cooling, and lighting. Although electricity demand for heating appears modest, it remains notable and refers exclusively to non-residential buildings within the districts. These elevated energy demands are mainly due to the poor thermal performance of the buildings’ opaque envelope, with Testaccio buildings having an average U-value of 1.89 W/(m2K), and to the low efficiency of existing heating and hot water systems.

5. PED Renovation and Renewable Energy Integration

Considering the critical issues identified in

Section 4.2, a set of renovation scenarios has been developed and simulated to improve the energy performance of the districts and support their transformation into PEDs. This scenario-based approach enables a stepwise evaluation of the effects of both individual and combined interventions on district-level energy performance.

The renovation measures comply with the thresholds established by the Minimum Requirements Decree [

45] and include

Insulation of vertical opaque structures and roofs by installing a layer of thermal insulation, achieving an average thermal transmittance value of 0.26 W/(m2K);

Replacement of existing windows with those featuring PVC frames and low-emissivity double glazing, achieving a thermal transmittance of 1.147 W/(m2K);

Replacement of traditional boilers with appropriately sized hydronic heat pumps with a coefficient of performance of 3.8;

Replacement of electric boilers with appropriately sized hydronic heat pumps with a coefficient of performance of 3.5;

Replacement of existing air-to-air heat pumps with more efficient ones, with a coefficient performance of 3 (higher than the limit for climate zone D);

Re-lamping of the lighting systems by replacing traditional light sources with high-efficiency LED systems to reduce electricity consumption.

Additionally, as PEDs focus on urban energy systems powered primarily by renewable energy sources (RES) to provide stability and flexibility in energy supply [

46,

47], in the final stage of the renovation strategy, on-site renewable energy generation is introduced through the installation of PV systems:

In the Testaccio District, monocrystalline PV panels with an efficiency of 21.9% are installed on rooftops, covering 111,665.20 m2, about 55% of total available roof area. With a tilt angle of 36°, the estimated peak capacity is 14.2 MW.

In the Valco San Paolo District, PV coverage reaches 124,873.03 m2 (approx. 61.11% of rooftop area), installed at a 30° tilt, with a peak power of 14.8 MW.

The renovation pathway is structured into five scenarios for each neighborhood, with each scenario progressively integrating additional efficiency measures:

Scenario 0—Baseline: Existing conditions, with no retrofit actions.

Scenario 1—Opaque Envelope Renovation: Application of thermal insulation to vertical opaque structures and roofs, reducing the average thermal transmittance to 0.26 W/(m2·K).

Scenario 2—Transparent Envelope Renovation: Replacement of windows with double-glazed low-emissivity units with PVC frames, achieving a thermal transmittance of 1.147 W/(m2·K).

Scenario 3—System Renovation: Replacement of

Traditional gas boilers with appropriately sized hydronic heat pumps (COP 3.8);

Electric boilers with hydronic heat pumps (COP 3.5);

Existing air-to-air heat pumps with more efficient units (COP 3.0), exceeding the requirements for climate zone D.

Scenario 4—Integrated Renovation and re-lamping: Combination of the three interventions above, plus re-lamping of lighting systems, with the replacement of conventional light sources with high-efficiency LED systems, resulting in an estimated 30% reduction in lighting electricity demand.

Through this structured approach, the impact of each intervention on the energy demand and performance of the districts can be clearly assessed. The final integrated renovation scenario (Scenario 4) also lays the foundation for evaluating the potential of the districts to achieve positive energy balance through the integration of renewable energy sources.

5.1. Renovation Scenario Performance Assessment—Testaccio District

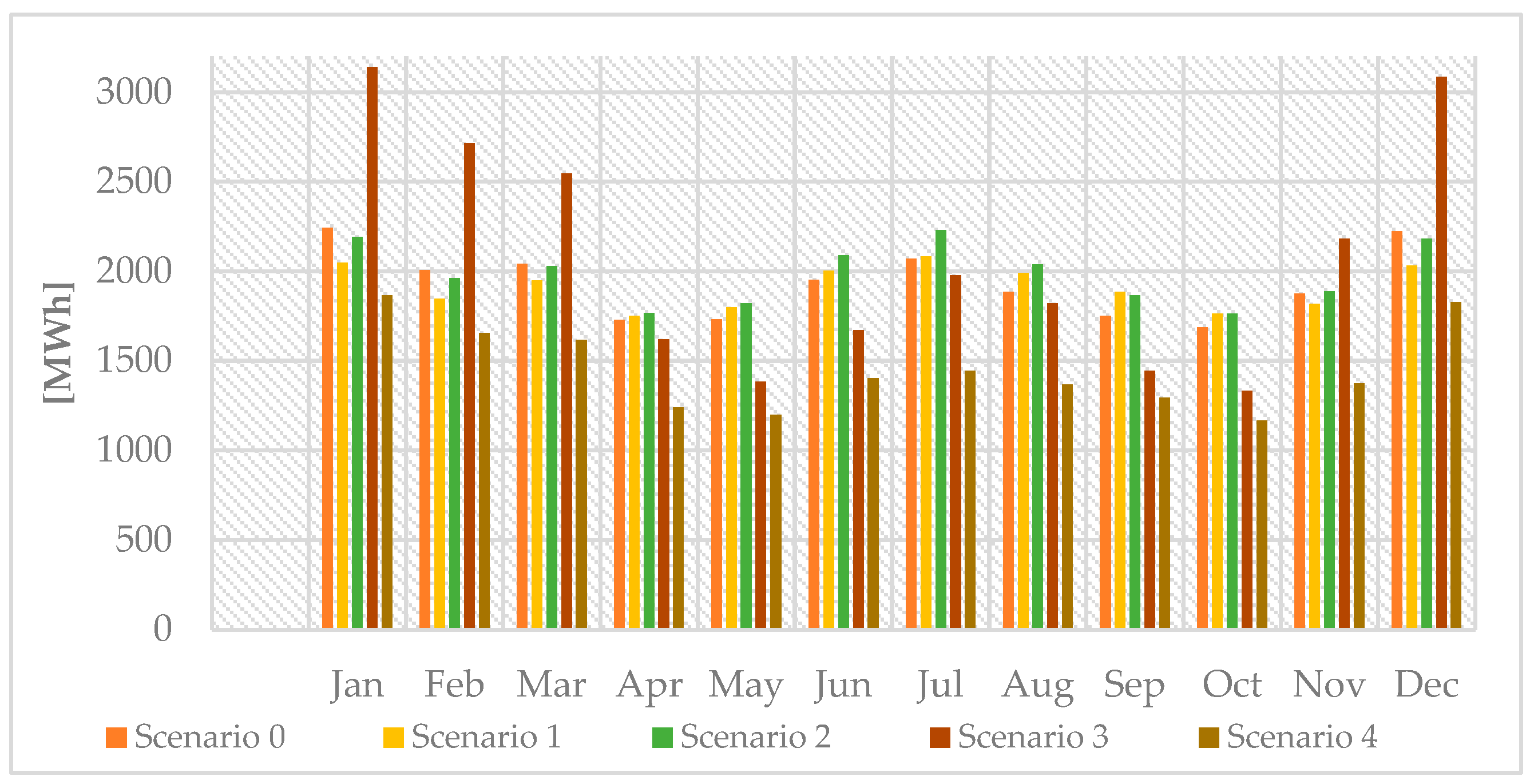

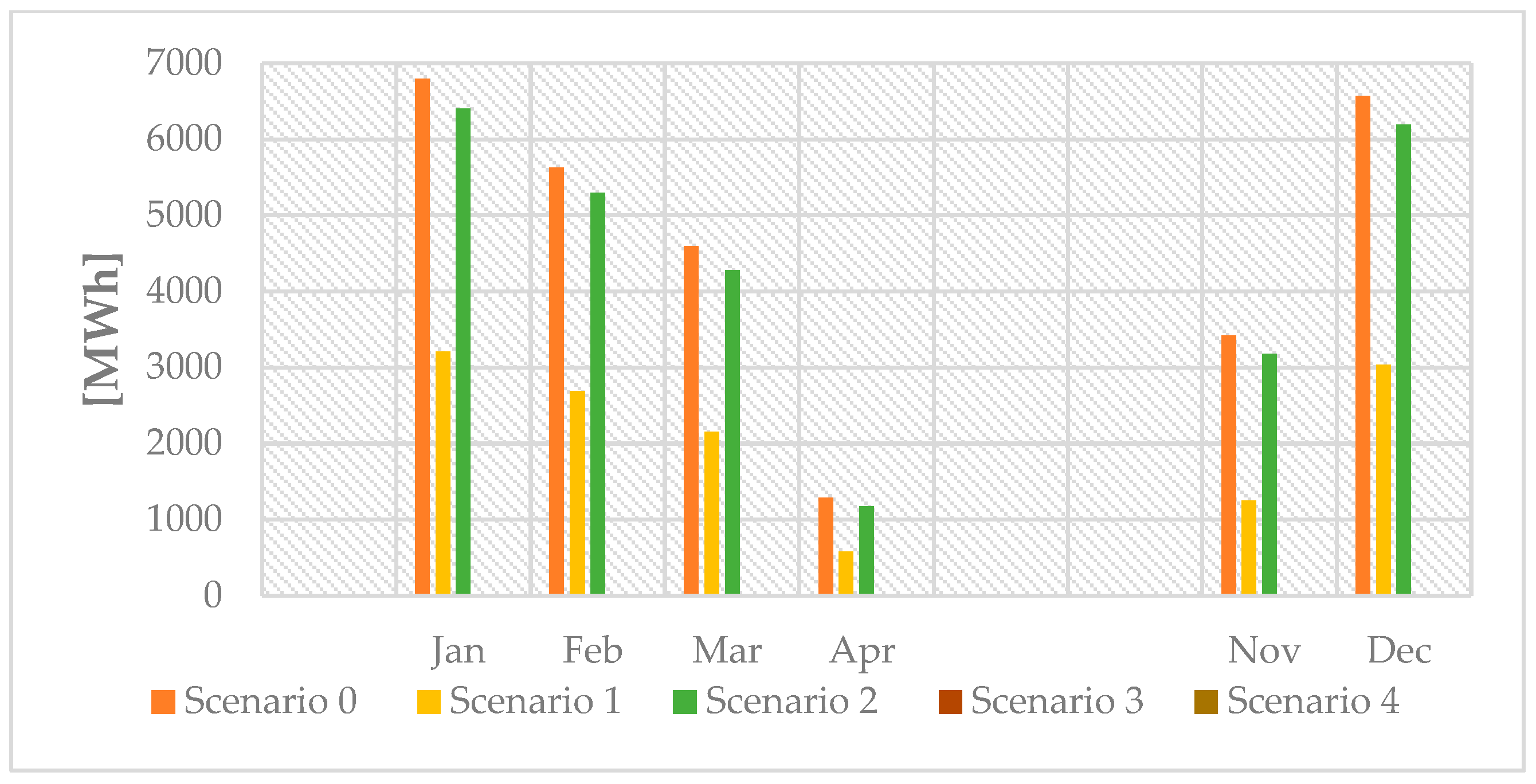

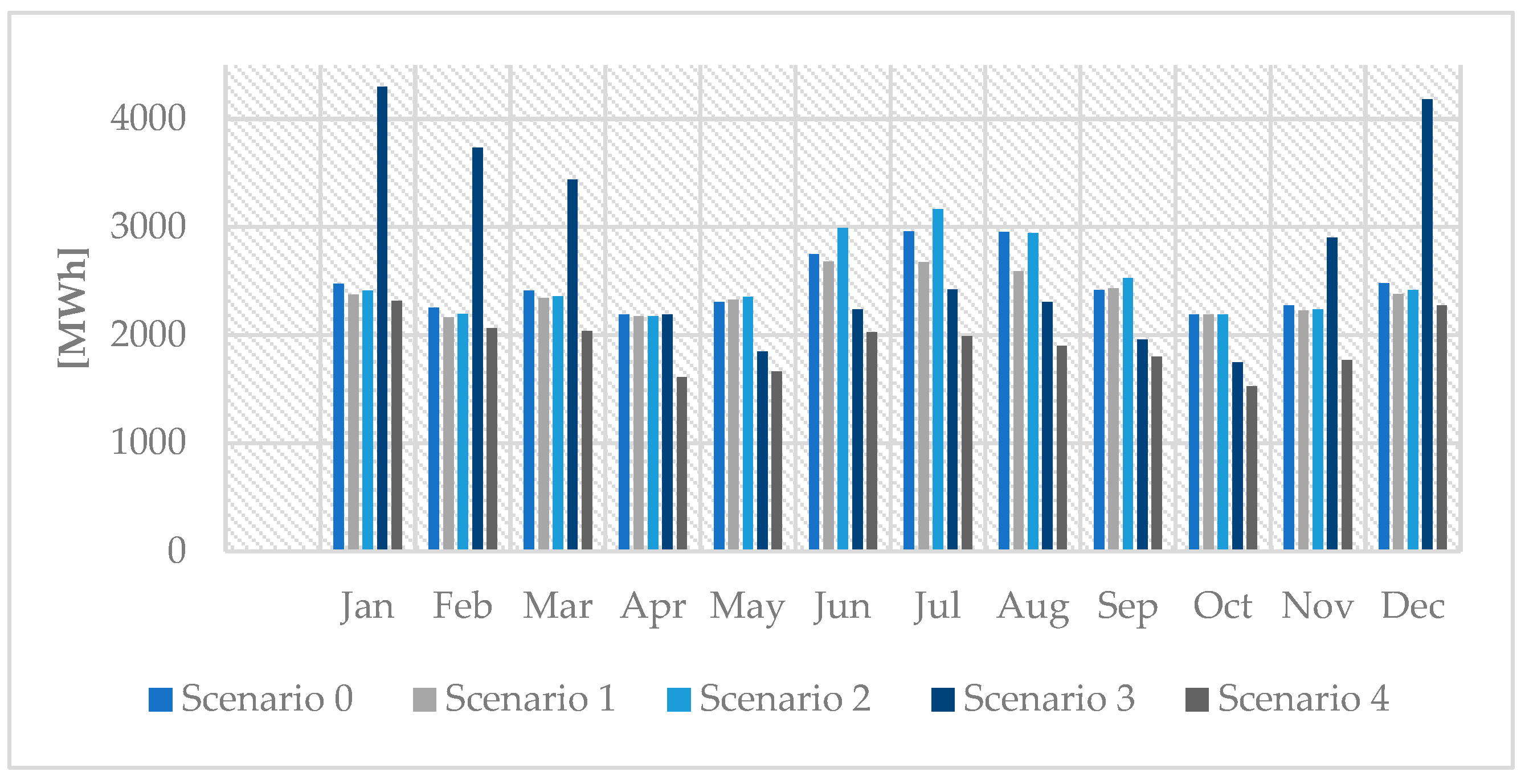

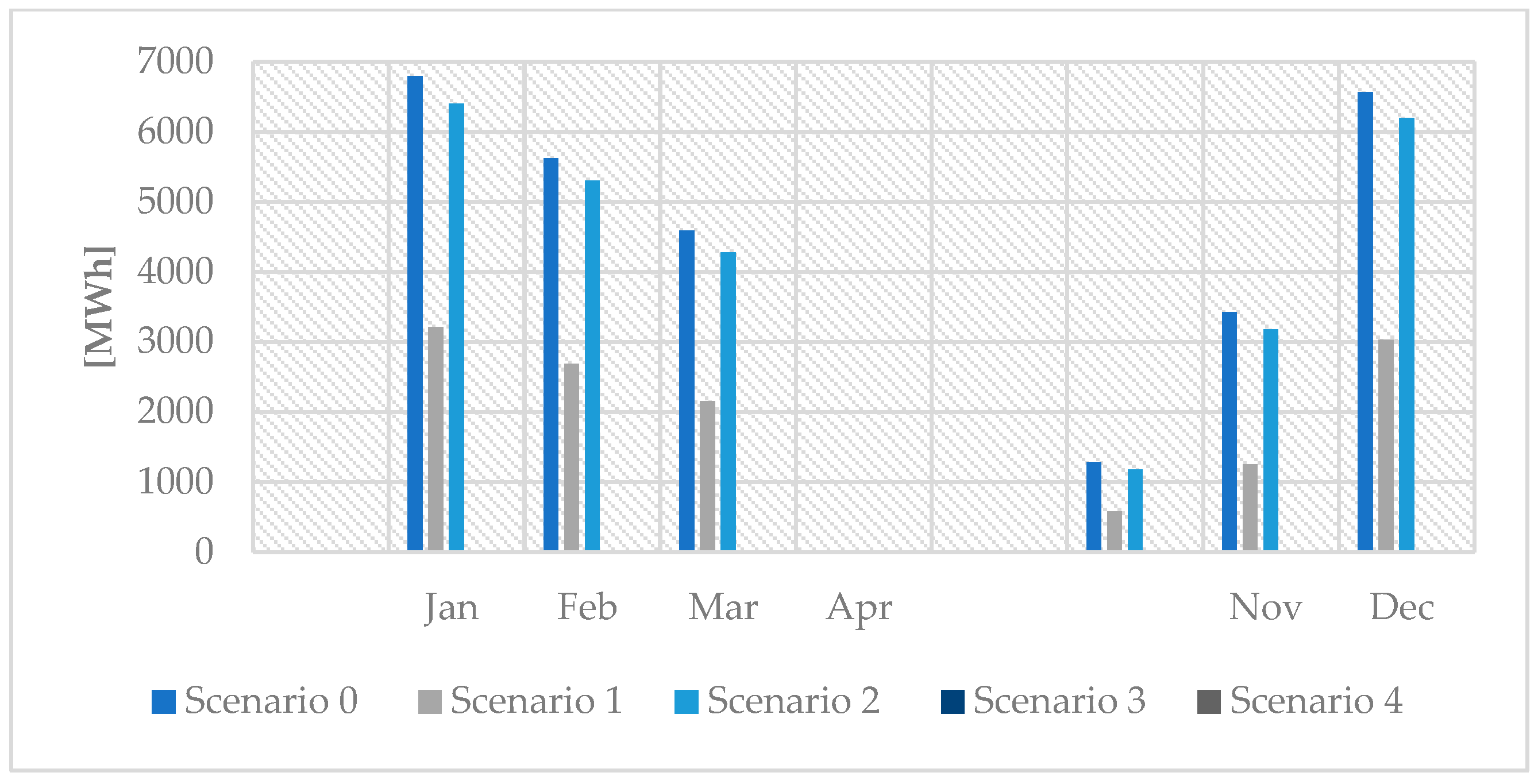

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the simulated electricity consumption and natural gas consumption demand for the Testaccio district across the defined scenarios (Scenario 0 to Scenario 4). These results illustrate the progressive impact of the renovation interventions on the district’s energy performance.

In Scenario 1, which includes insulation of vertical opaque surfaces and roofs, electricity consumption decreases significantly during the winter months and increases modestly during the summer, likely due to reduced passive thermal inertia and the increased need for cooling. Overall, electricity consumption decreases by only 0.99% annually. Natural gas consumption shows a significant reduction, exceeding 50% in most months, with the largest decline recorded in November (−63.41%). Scenario 2, which includes improvements to the transparent envelope, follows a similar trend to Scenario 1, but with less pronounced effects. Electricity consumption shows a slight overall increase (+2.75%), likely due to reduced natural ventilation resulting from more airtight windows, which leads to a greater reliance on active cooling systems during the summer months. Nonetheless, annual natural gas demand continues to decline, albeit more modestly (6.24%).

Scenario 3, which envisages system replacement, leads to the complete electrification of heating and DHW production. Consequently, electricity consumption increases significantly in winter, peaking at +40.06% in January. On an annual basis, consumption increases by 7.45%. However, this figure must be interpreted considering the complete elimination of natural gas consumption (−100%).

Scenario 4, which envisages efficiency improvements across the entire building-system, shows that total annual electricity consumption is reduced by almost 25% compared to the baseline scenario. At the same time, natural gas consumption is eliminated (100%). Electricity savings are observed consistently throughout the year, with monthly reductions ranging from 17% in January to more than 30% in October. In absolute terms, there are savings of 5733.68 MWh, clearly highlighting the effectiveness of the Scenario 4 strategy in achieving substantial reductions in electricity and natural gas consumption and in promoting the achievement of the district’s decarbonization and energy efficiency objectives.

Table 7 presents the monthly primary energy demand for the Testaccio district across all scenarios, including the percentage variations relative to the baseline Scenario 0. The analysis of primary energy demand allows us to capture the combined effect of reductions in electricity and natural gas consumption, as well as the shift in energy carriers resulting from electrification and efficiency improvements.

In line with what was previously observed, it can be seen that

In Scenario 1, a significant reduction in primary energy demand is observed between December and February, with decreases exceeding 30% and a total annual reduction of approximately 25% compared to the baseline scenario.

Scenario 2 involves marginal variations compared to Scenario 1, with annual primary energy savings falling to approximately 2%.

Scenario 3 predicts an overall reduction in consumption from 20% to almost 40% and a reduction in total annual primary energy demand of 33.62%.

Scenario 4, combining all interventions, allows for a reduction in primary energy demand of over 60% during the coldest months and approximately 25–35% in the summer months, with total annual primary energy demand more than half that of Scenario 0, corresponding to an impressive reduction of 54.31%.

This clearly demonstrates the synergistic effect of comprehensive renovation strategies in significantly reducing the district’s overall energy consumption.

Considering the application of the technical solutions included in the previous, the results reported in

Figure 11 provide a detailed breakdown of the electricity energy demand components for Scenario 4. This allows for an in-depth assessment of the renovation impacts on different end-uses such as heating, cooling, DHW, electricity for appliances, lighting, industrial process and auxiliary loads.

While the overall electricity demand decreases as a result of the retrofit interventions, the distribution of consumption across end uses changes significantly, most notably in relation to heating. In the existing scenario (

Figure 5), electricity demand is characterized by a marked winter peak, primarily driven by electric heating in non-residential buildings. Out of the 150 buildings analyzed, 59 are non-residential and rely on electric heating systems, while the residential stock is predominantly heated using natural gas. This limited use of electricity for heating keeps winter loads relatively moderate, despite their seasonal concentration in January, February, and December. Throughout the year, hot water production, lighting, and appliances represent consistent electricity end uses, while cooling demand is most evident in the summer months, particularly in July and August.

In scenario 4 (

Figure 8), the electrification of heating across the entire district, including the residential sector, results in a significant increase in electric heating demand during winter. This shift leads to a higher winter peak in electricity consumption, even though energy efficiency measures, such as improved thermal insulation and the adoption of high-performance heating systems, have been implemented. The replacement of fossil fuel-based systems with electric ones in residential buildings contributes substantially to this change. Consequently, despite reductions in several other end uses, the overall winter electricity load remains high, or even slightly increases. One of the most notable reductions observed in the final scenario concerns DHW demand. This is largely due to the replacement of electric boilers with heat pump water heaters, which significantly improve energy efficiency. Similarly, lighting demand decreases by approximately 30%, mainly as a result of the widespread adoption of high-efficiency lighting technologies. Cooling demand also declines slightly during the summer months, indicating improved passive performance and better-performing cooling systems. Nevertheless, this reduction is less significant than the winter increase in heating demand. Meanwhile, energy consumption for appliances, auxiliary systems, and industrial processes remains essentially unchanged, since no specific measures were targeted at these categories.

Overall, the retrofit strategy implemented in the Testaccio district proves effective in reducing total electricity demand and improving efficiency in key areas such as space conditioning, hot water, and lighting. At the same time, baseline consumption levels are maintained in end uses not directly addressed by the interventions. The electrification of residential heating, while crucial for decarbonization, leads to a pronounced shift in seasonal demand patterns, underscoring the importance of considering fuel-switching effects in future energy planning.

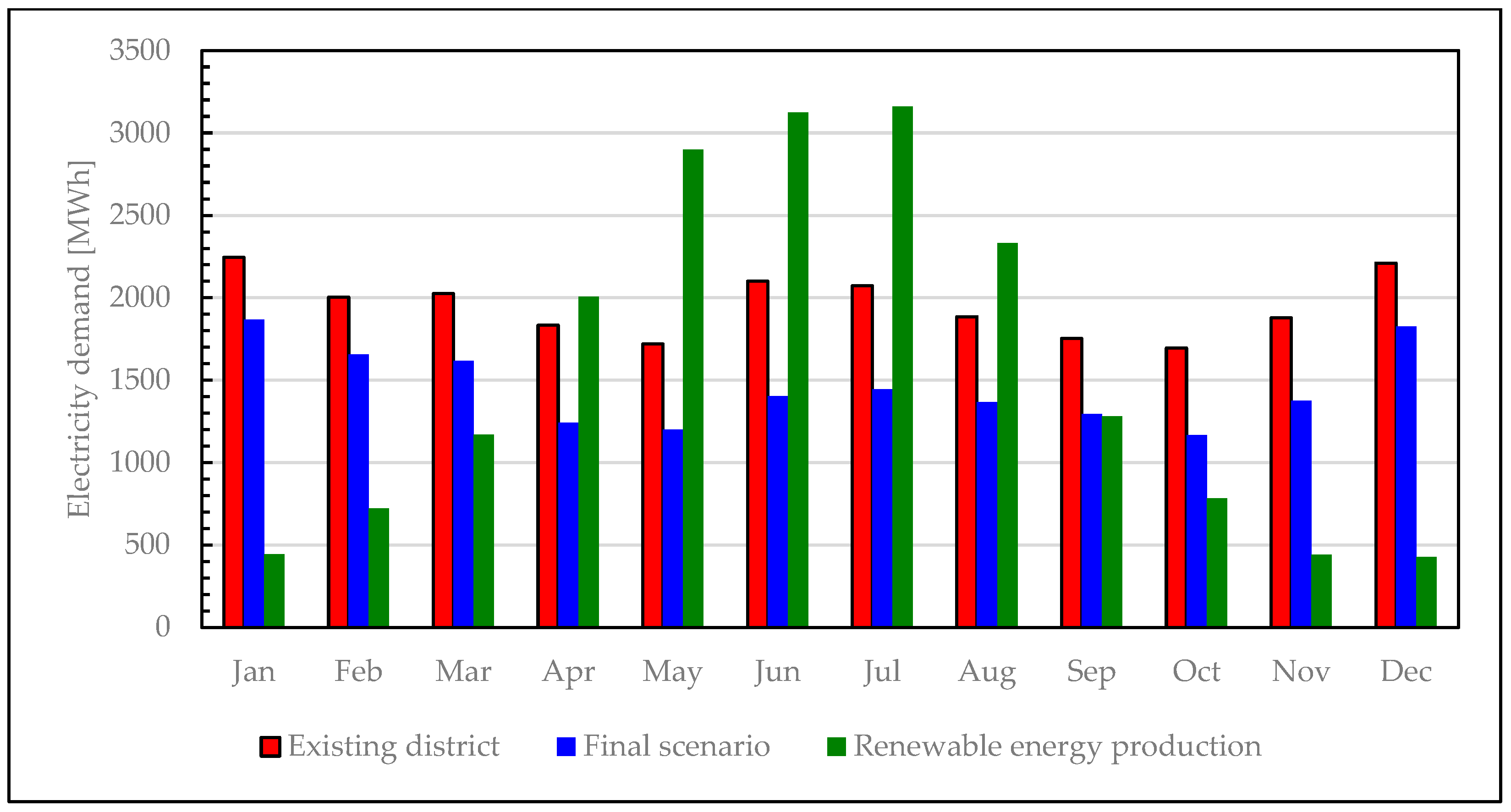

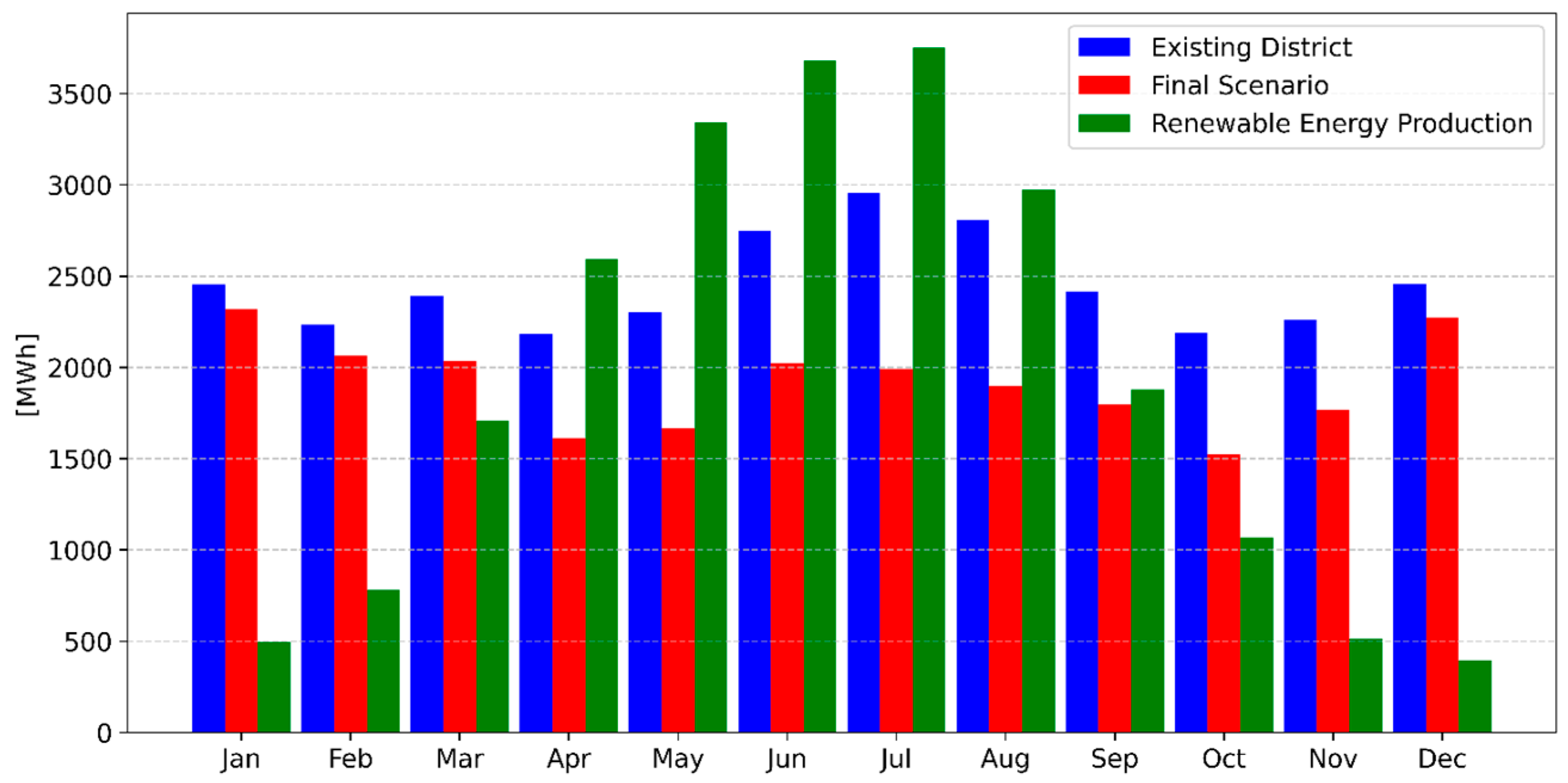

Figure 12 highlights the comparison between electricity demand in the existing and final scenarios, alongside the contribution of renewable energy production. The PV system is estimated to generate approximately 18,793.09 MWh per year, which exceeds the district’s total electricity demand in the final scenario.

The graph clearly shows that from April to August, the monthly renewable energy production surpasses the district’s electricity consumption, allowing for a surplus of locally generated energy. In September, production is slightly lower than demand, while from October to March, renewable generation drops significantly and remains well below the district’s consumption levels. Despite the seasonal imbalance between generation and consumption, the annual energy balance remains positive. This outcome is particularly significant when assessing the district’s transition toward sustainability. The fact that the total yearly electricity production from the PV system exceeds the annual demand confirms that the Testaccio district can be classified as a PED.

This classification is not merely a numerical threshold, but a strategic milestone in the context of urban energy transition. It implies that the district, as a whole, has the potential to not only cover its own energy needs through on-site renewable sources but also contribute surplus energy to the grid during certain periods of the year. Such a configuration supports the decentralization of energy systems, enhances local energy autonomy, and reduces dependence on fossil fuels. Moreover, achieving PED status entails substantial environmental and systemic benefits, including lower greenhouse gas emissions, increased resilience to energy price volatility, and a more balanced load on centralized infrastructure. These characteristics position the Testaccio district as a replicable model for other urban areas aiming to meet EU climate and energy goals, while promoting energy democracy and community engagement in the energy transition.

5.2. Renovate Scenario Performance Assessment—Valco San Paolo District

After assessing the effects of the proposed renovation strategies on the Testaccio district, the same methodological approach is now applied to the Valco San Paolo district. This allows for a comparative understanding of how different urban and morphological features influence the effectiveness of energy retrofit interventions.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 report the simulated monthly electricity and natural gas consumption under Scenarios 0 through 4, along with their percentage variations relative to the baseline. This enables a comparative evaluation of the renovation strategies in a different urban context.

In Scenario 1, the impact on thermal energy demand was particularly noticeable during the heating season, with a reduction of approximately 41%. Electricity consumption also decreased, albeit less dramatically, with an overall reduction of 3.78% over the course of the year. The largest savings occurred in the summer months of July and August, reaching reductions of up to 12.4%. This is likely due to lower cooling demand resulting from improved insulation. In Scenario 2, annual natural gas consumption decreased by approximately 30%. The most significant savings occurred during the heating season, while electricity consumption remained almost unchanged throughout the year.

In Scenario 3, natural gas consumption for heating was eliminated, with a simultaneous increase in electricity consumption of approximately 12%. The complete transition to electric heating represents an important step towards decarbonization. Indeed, despite the increase in electricity consumption, eliminating fossil fuel consumption brings clear environmental benefits. The overall effect on primary energy demand will depend on the electricity generation mix, but electrification is essential to achieving significant greenhouse gas reductions in the building sector. For this reason, in the following sections, the additional electricity demand generated by these electrical systems will be addressed by increasing renewable energy production through PV systems. In Scenario 4, total electricity demand decreased by approximately 23% and natural gas demand by 100%. On a monthly basis, a minimum variation of approximately 6% was recorded in January and a maximum of 36% in August. Similarly to what was seen in the Testaccio district, in Valco San Paolo, the maximum decrease of approximately 31% was also recorded in October. It is therefore clear that each renovation intervention contributes differently: insulating the building envelope produces the greatest reductions in heating and cooling loads; modernizing windows offers moderate savings on heating costs but may slightly increase cooling demand; replacing the HVAC system completely decarbonizes heating but increases electricity consumption. In Valco San Paolo, as in Testaccio, to jointly evaluate changes in electricity and natural gas demand, the neighborhood’s primary energy consumption was analyzed under different scenarios, and the results are presented in

Table 8.

The analysis of primary energy consumption across the scenarios highlights significant improvements compared to the baseline (Scenario 0). Overall, Scenario 4 achieves the greatest reduction, with total annual primary energy demand decreasing by 56.84%, dropping from approximately 92,924 MWh to 40,109 MWh. This substantial reduction is consistent across all months, with the largest monthly savings observed in winter, particularly in January and December, where reductions exceed 65%. These results reflect the full electrification and optimization measures implemented in this scenario. Scenario 3 also shows a marked decrease of about 32.5% in annual primary energy demand, with notable savings during the heating season. The reductions in the colder months range from roughly 27% to 37%, confirming the effectiveness of replacing gas boilers with electric heating systems, despite the associated increase in electricity use.

Scenario 1, focusing on insulation, reduces annual primary energy consumption by about 20.7%. The greatest monthly improvements occur in the cold months (January to March and December), with reductions between 22% and 27%. Summer months show smaller or negligible changes, which aligns with the insulation primarily reducing heating demand. Scenario 2, which involves window replacement, yields a more moderate overall reduction of approximately 13.5%. Monthly savings during the heating season range between 11% and 18%, but some months in summer show slight increases or very limited reductions, likely because of cooling loads and ventilation.

In summary, the progressive implementation of renovation measures results in increasingly significant reductions in primary energy consumption. Scenario 4 stands out as the most effective, demonstrating the benefits of combining insulation, window upgrades, HVAC electrification, and likely renewable energy integration. This comprehensive approach is essential for achieving deep energy savings and supporting the district’s decarbonization goals. Therefore, while each intervention offers specific benefits, their combined implementation, as examined in previous, represents the most balanced and effective approach to lowering energy consumption and carbon emissions across the district.

The application of all the technical solutions for energy improvement to district Valco San Paolo is represented in

Figure 15.

In the Valco San Paolo district, the current scenario shows an almost negligible electricity demand for space heating. Out of the 273 buildings analyzed, only 31 use electric heating systems, while the vast majority, both residential and non-residential, are equipped with natural gas-based systems. As a result, winter electricity loads remain very low, especially when compared to the Testaccio district, where a larger share of non-residential buildings already rely on electric heating. In scenario 4, following the complete electrification of heating, a substantial increase in winter electricity demand is observed. This rise is primarily due to the replacement of all gas-based heating systems with heat pumps across the entire building stock. Despite the implementation of energy efficiency measures, such as improved building envelopes and the adoption of high-performance systems, the full transition from gas to electricity results in a significant rise in electric heating loads compared to the baseline.

Similarly to what was observed in Testaccio, Valco San Paolo also shows notable reductions in electricity demand for DHW and lighting. The replacement of electric boilers with heat pump water heaters leads to considerable savings in hot water energy use. In addition, lighting demand decreases by approximately 30 percent due to the widespread adoption of energy-efficient lighting technologies. Cooling demand shows a slight decline during the summer months, reflecting improved passive performance and the use of more efficient cooling systems. However, as in Testaccio, this reduction in the summer is less pronounced than the winter increase in heating demand.

Electricity consumption associated with appliances, auxiliary systems, and industrial processes remains essentially unchanged, as these end uses were not specifically targeted by the retrofit strategy. Overall, the Valco San Paolo case confirms that full electrification of space conditioning, even when combined with efficiency improvements, can lead to a marked increase in seasonal electricity demand, particularly in areas that were previously heavily reliant on fossil fuels. This highlights the importance of accounting for fuel-switching effects and ensuring that grid infrastructure is adequately prepared to support the energy transition.

Figure 16 shows the electricity demand comparison between existing and final scenarios and renewable energy production. Energy production exceeds electricity demand. As a result, in this scenario, the Valco San Paolo district can be considered a PED.

The installation of the PV system estimates an energy production of 23,193.87 MWh/year. As shown in

Figure 11, from October to March, renewable energy production is lower than electricity consumption, while from April to September, production exceeds consumption. This trend is also observed in the Testaccio district, except for September, when production was slightly lower than consumption.

6. Performance Indicators

To evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented measures and quantify the resulting improvements, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are employed. In general, assessments focus on key performance indicators (KPIs) of renewable energy systems, as well as on measuring energy consumption and carbon emissions of major energy systems [

48,

49]. KPIs quantify performance parameters such as self-sufficiency, peak shaving and renewable energy share [

50].

These quantitative metrics assess the energy retrofit strategy applied to the district by providing a clear and standardized means of measuring gains in energy efficiency, renewable energy integration, and environmental impact. KPIs enable a thorough comparison between the existing and final scenarios, supporting informed, data-driven decisions for future district-scale energy planning.

The study emphasizes two main KPIs:

The load cover factor (LCF) is used in the final evaluation as a quantitative measure of the ability of local renewable energy sources to meet the district’s energy needs. As shown in Equation (1) it is defined as a function of on-site generation

g(

t), load

l(

t), energy losses

ζ(

t), and storage balance

S(

t):

The interaction index provides an indication of what happens instant by instant regarding the interaction with the grid. As shown in Equation (2), it is defined as

where

is the net exported energy, calculated as the difference between the energy exported from the building to the grid and the delivered energy .

is the maximum value that can assume.

These metrics, in conjunction with energy balance assessment, are crucial in determining the feasibility of achieving PED status for each district.

6.1. Load Cover Factor (LCF)

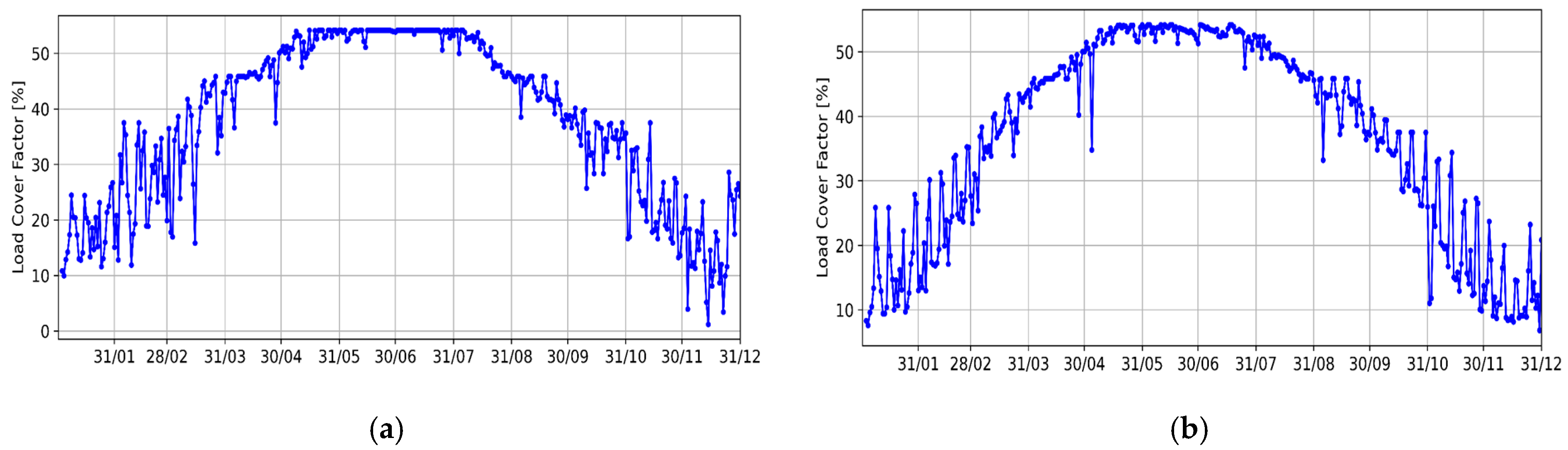

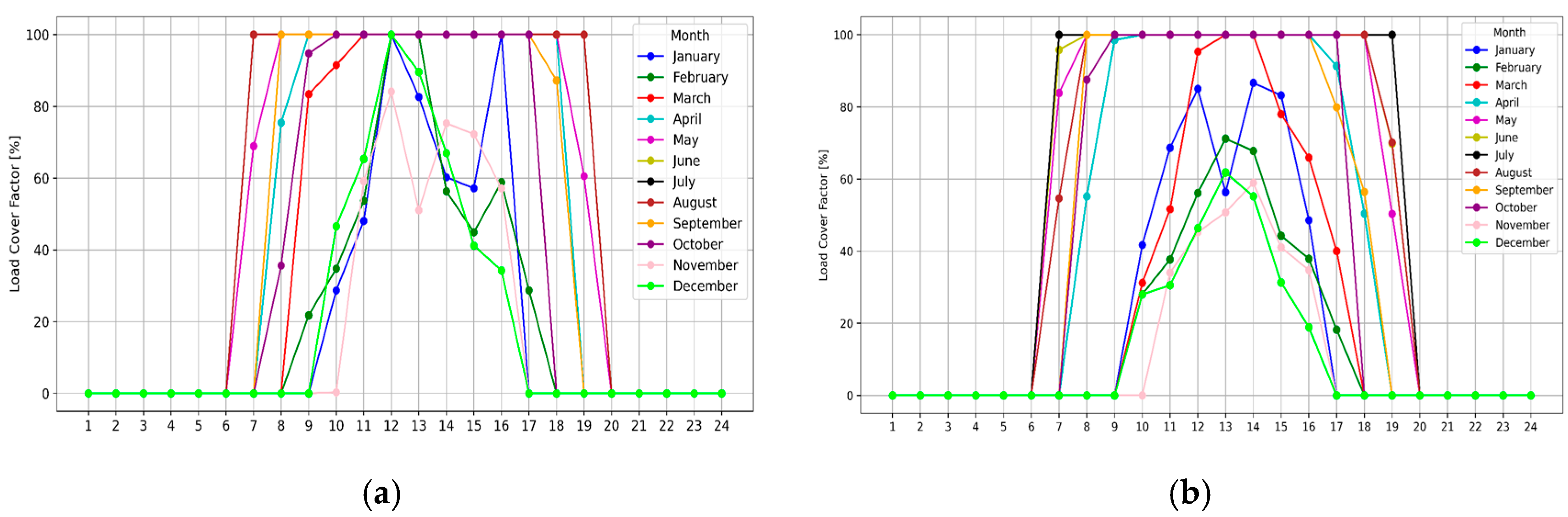

Considering simultaneity of production and consumption, the LCF was calculated on an hourly time step, and the daily average of the hourly values is shown in

Figure 17.

By analyzing the daily LCF trends, similar patterns emerge in both cases. Both show the lowest values during the winter period and reach peak values in the summer. However, even during summer, the maximum average daily value only reaches around 55%, due to nighttime hours when the LCF is zero, which lowers the overall daily average. For this reason,

Figure 18 depicts the hourly LCF over 24 h for a representative day of each month.

These charts show that during the summer months, the LCF consistently reaches 100%, with only occasional exceptions. Although the district generates an annual amount of electricity that exceeds its total consumption, the LCF reaches an average annual value of 37.76% in Testaccio and 36.5% in Valco San Paolo. This indicates that, despite the overall renewable energy production being higher than the electricity demand, only a limited portion of the consumption is directly met by local production. This is primarily due to temporal mismatches between energy generation and demand throughout the day and year.

6.2. Grid Interaction Index

The main physical parameter in the interaction with the distribution grid is the magnitude of the power injected or consumed by a building or group of customers. This parameter will determine the power flow through the grid components and, consequently, currents and voltage levels [

51]. This indicator is defined as the ratio between the net exported energy (the difference between exported energy and imported energy) and the maximum net exported energy in absolute value.

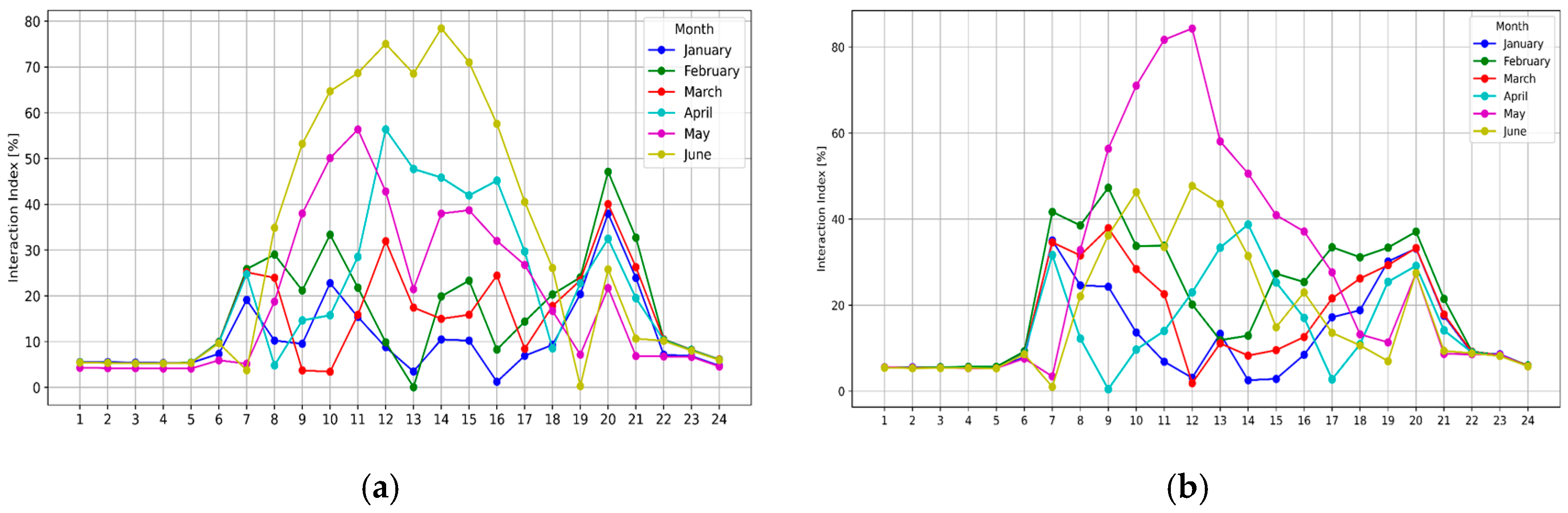

Figure 19 illustrates how the grid is much more stressed in summer than in winter due to the energy production from PV systems, which puts the grid under strain.

The graphs show that the Interaction Index reaches its peak values in June for Testaccio and in May for Valco San Paolo. In both cases, this corresponds to a period when solar energy production becomes substantial while electricity demand, particularly for cooling, is still relatively low.

6.3. Scenario with Energy Storage Integration

Given the significant amount of locally produced renewable electricity, in order to further increase the amount of self-consumed electricity and reduce dependence on the grid, a second scenario has been implemented, which envisions the integration of an energy storage system. The objective is to evaluate the impact of storage on the district’s energy balance and identify the optimal size of the battery system, maximizing self-consumption while considering the environmental impact associated with the production and disposal of the batteries in the sizing process.

The analyzed storage system consists of lithium-ion batteries, characterized by

Charge/discharge efficiency of 90%;

Depth of Discharge (DoD) of 80%;

Initial state of charge (SOC) of 100%;

Maximum SOC of 100%;

Minimum SOC of 20%.

The battery capacity was progressively varied until reaching a saturation point, beyond which further increases in capacity did not result in significant benefits in terms of self-consuming energy.

The results of the analysis conducted for the two districts reveal a similar overall behavior in terms of LCF improvement with increasing storage capacity. However, a more detailed analysis highlights subtle but significant differences that influence the optimal sizing decision. For zero storage capacity, the LCF starts at approximately 37.75% for Testaccio and 36.51% for Valco San Paolo, representing the baseline scenario without storage. Increasing storage capacity to 50 kWh results in a significant increase in LCF for both districts, reaching 68.23% for Testaccio and 67.01% for Valco San Paolo, almost doubling the load coverage compared to the no-storage scenario. The increase in LCF tends to stabilize for capacities above 30,000 kWh, with only marginal gains at very high capacities (100,000 kWh and 200,000 kWh), where Testaccio reaches LCF values of 69.10% and 70.09%, respectively, while Valco San Paolo reaches 68.35% and 69.34%. This suggests a saturation effect, in which adding storage capacity beyond a certain threshold produces diminishing returns. The Testaccio district consistently shows slightly higher LCF values than Valco San Paolo across all storage sizes considered. While this difference is minimal, it can be attributed to the different types of electricity loads and the temporal variation in load demand between the two districts. For example, in Testaccio, a 5000 kWh battery results in a 4.51% increase in LCF compared to the no-storage scenario, while Valco San Paolo records a slightly smaller improvement of 3.58%. In Testaccio, the LCF reaches 66.87% at 25,000 kWh, an overall improvement of 29.11% compared to the no-storage scenario. Beyond this point, the marginal gains decrease dramatically, with variations between consecutive scenarios of less than 0.5%, suggesting a saturation effect. For example, doubling the storage capacity from 50,000 to 100,000 kWh results in an additional gain of only 0.87%. Conversely, in Valco San Paolo, the maximum marginal benefit occurs first, at 20,000 kWh, where the LCF reaches 63.73% (27.22% higher than the baseline). Increasing capacity beyond this value yields incremental improvements of less than 0.5%, and in some cases less than 0.15%, confirming faster saturation compared to Testaccio. Even doubling capacity from 50,000 to 100,000 kWh yields a modest gain of 1.35%. This comparison suggests that optimal storage system sizing should be context-specific, based on energy demand profiles, local generation variability, and the saturation behavior of each district. Based on the trade-off between improved performance and cost-effectiveness, a storage capacity of approximately 25,000 kWh appears optimal for Testaccio, while 20,000 kWh is more suitable for Valco San Paolo. In conclusion, the analysis highlights that integrating storage systems is an effective strategy for improving electricity load coverage, with a significant impact already observed at moderate storage capacities. However, when planning investments, the marginal effectiveness of increasing storage capacity beyond high thresholds should be carefully assessed.

6.4. Loss of Load Probability

Loss of Probability refers to the estimated likelihood that a specific threat will successfully exploit a vulnerability, resulting in a tangible loss or damage. It is a key component in risk assessment methodologies, particularly within the fields of cybersecurity, safety engineering, and disaster management. This factor helps quantify the potential impact of adverse events by combining the probability of occurrence with the severity of the outcome, thereby supporting informed decision-making in risk mitigation strategies.

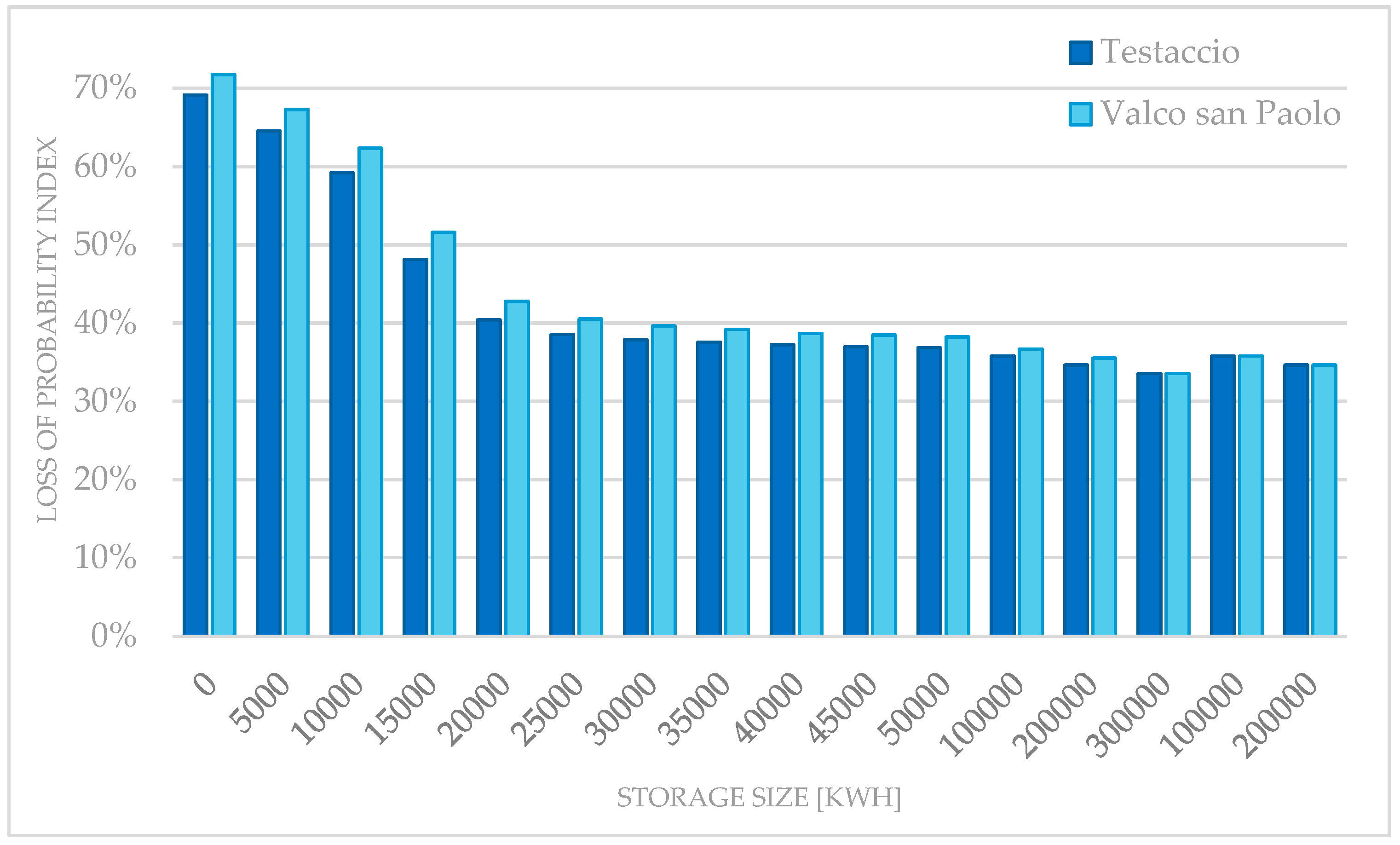

Figure 20 illustrates the variation in the loss of load probability as a function of the selected battery storage size, highlighting the relationship between storage capacity and associated risk levels in the Testaccio and Valco San Paolo districts, respectively.

At the beginning of the series, the Loss of Probability Index is quite high in both areas, with Testaccio starting at around 69.14% and Valco San Paolo slightly higher at approximately 71.76%. This indicates that, without a significant storage capacity, the probabilities of loss or inefficiency are fairly elevated. As the battery size increases, there is a steady and significant decrease in these values. For instance, in the first half of the data, Testaccio drops rapidly to about 40.41%, while Valco San Paolo follows a similar trend, reaching around 42.76%. Moving to the intermediate values, the two series stabilize around 37–38% for Testaccio and around 39–40% for Valco San Paolo, reflecting a substantial improvement but with losses still noticeable. In the final part of the series, there is a further decline, with Testaccio reaching approximately 34.65% and Valco San Paolo 35.53%. The difference between the two sites narrows significantly at this stage, suggesting that as storage capacity increases, the performances tend to converge. Overall, Valco San Paolo consistently shows slightly higher Loss of Probability Index values compared to Testaccio, with a difference of about 2–3 percentage points, likely due to specific local characteristics or conditions. Finally, towards the higher end of the storage sizes, the reduction in values slows down, indicating that increasing storage capacity yields diminishing improvements beyond a certain point. This suggests a saturation effect, where further capacity increases continue to bring benefits but to a lesser extent.

6.5. Coverage of the Electricity Energy Needs of the Districts

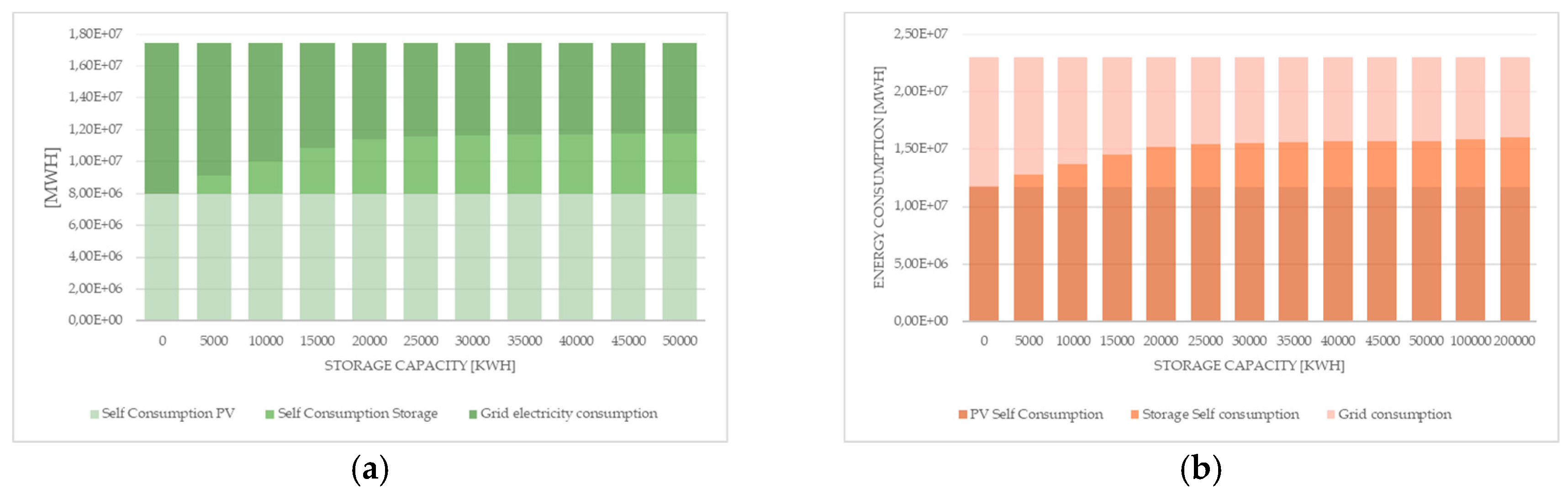

Figure 21 illustrates how the electricity demand of the Testaccio and Valco San Paolo districts is met through PV generation and battery storage, under varying battery capacities:

The energy directly consumed by the PV system (in red) remains constant, representing the surplus energy.

The surplus electrical energy is stored in the battery storage system (in blue) according to the battery’s capacity and clearly increases as the battery size increases.

The green section represents the surplus electrical energy that cannot be stored in the battery system because it is saturated, and consequently, must be fed into the grid. This, being complementary to the surplus stored in the battery, decreases as the battery size increases.

Figure 22 depicts the distribution and management of energy generated by the PV system under different battery storage capacity scenarios:

The orange bar represents the energy directly consumed by the user and remains constant across the different scenarios.

The yellow bar represents the energy fed into the grid and decreases as the storage capacity increases.

The green bar represents the energy stored in the battery system and increases as the storage capacity increases.

6.6. Discussions

A comparative analysis of the two PEDs, Testaccio and Valco San Paolo, highlights distinct urban configurations that influence energy profiles, energy retrofit strategies, and the effectiveness of technological interventions. Testaccio, with its compact urban layout and high presence of non-residential buildings, experiences pronounced peaks in winter electricity demand, largely due to electric heating in public services and facilities. Following renovation projects involving the entire building-system, its annual electricity demand has decreased by approximately 25%, and the installation of a 14.2 MW PV system guarantees annual production of 18,793 MW. Valco San Paolo, on the other hand, comprises a more fragmented building stock, of which only 11% is non-residential, highlighting a significant demand for cooling loads. Its initial energy demand was reduced by 23% through comprehensive efficiency measures, while its slightly larger 14.8 MW PV system generates 23,193 MWh/year. While meeting the PED criterion, the district exhibits greater seasonality due to a higher window-to-wall ratio (0.35 compared to 0.15) and a dispersed building morphology, making the energy balance more complex. In both districts, the integration of lithium-ion battery storage leads to a substantial increase in LCF, underscoring the essential role of storage in improving self-consumption and minimizing grid dependence. Testaccio achieves its optimal balance at 25,000 kWh, achieving an LCF of 66.87%, representing a 29.11% improvement compared to the scenario without storage. Valco San Paolo reaches its saturation point at 20,000 kWh, achieving an LCF of 63.73% and a gain of 27.22%. This divergence reflects the influence of local load patterns and generation profiles on the scalability of storage systems. The results highlight the importance of adapting battery sizes to the specific characteristics of each district, as a uniform sizing strategy would likely lead to suboptimal performance and unnecessary environmental costs. From a resilience perspective, Testaccio’s density facilitates centralized energy sharing schemes and collective self-consumption models, potentially supporting the development of microgrids. In contrast, Valco San Paolo’s more distributed configuration requires modular and decentralized approaches but may offer greater potential for flexible load management during summer peak demand. These morphological differences also influence the replicability of solutions: Testaccio supports the simplified implementation of large-scale interventions, while Valco San Paolo requires customized and context-sensitive strategies. Ultimately, while both districts achieve annual energy self-sufficiency and benefit from integrated storage systems, their contrasting urban and functional structures require differentiated planning approaches. Testaccio demonstrates greater efficiency in terms of responsiveness of interventions and energy balance. Valco San Paolo, despite its complexity, reveals significant transformational potential when retrofit, generation, and storage measures are coherently designed and spatially integrated.

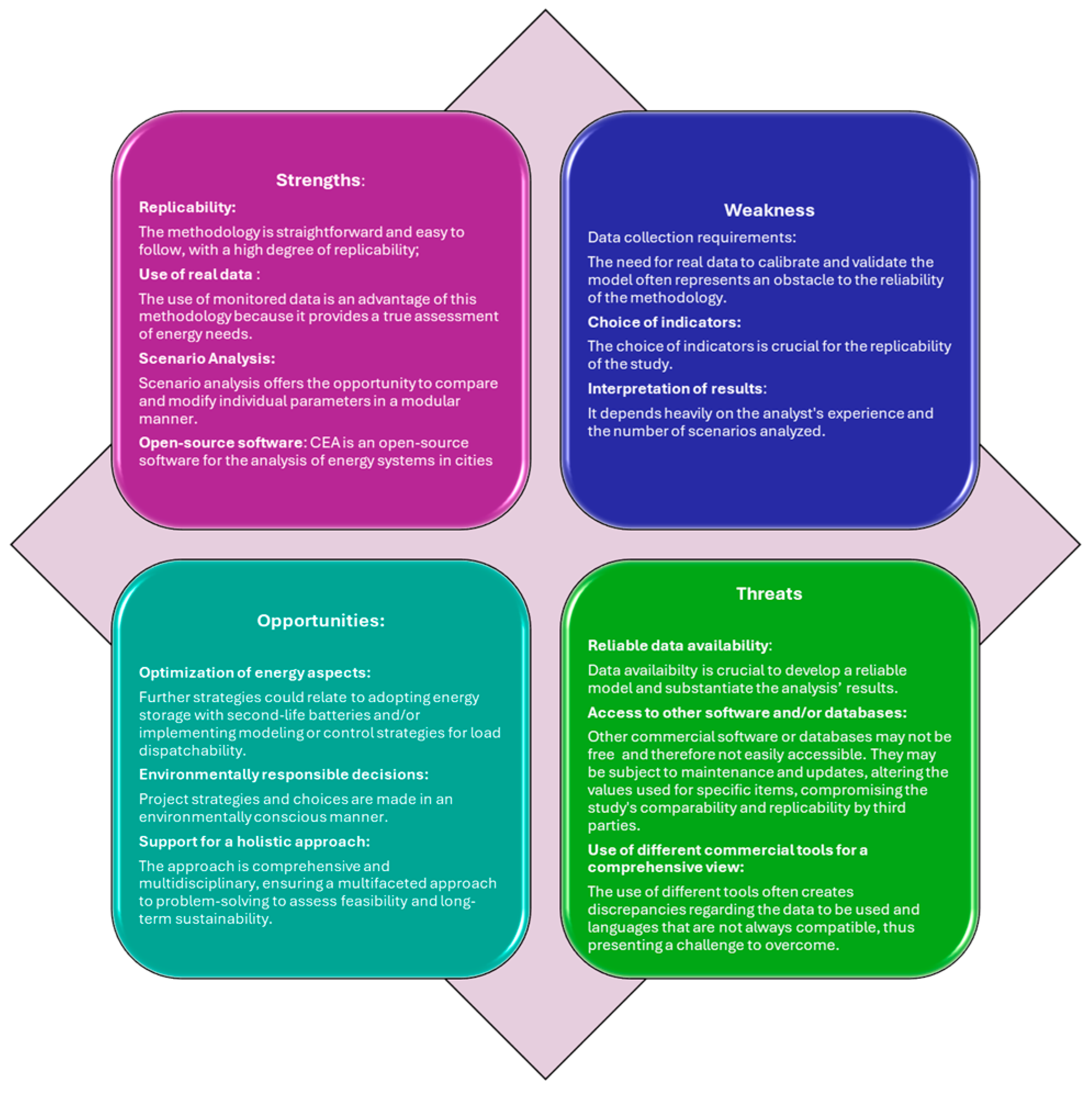

Finally, a SWOT analysis is a planning tool that aims to identify the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of a project or organization. It is a framework for adapting an organization’s goals, programs, and capabilities to the context in which it operates. The SWOT analysis shown in

Figure 23 reveals that while modular and replicable scenario-based assessments improve methodological robustness, persistent issues such as limited data availability, reliance on commercial software, and time-consuming analysis processes pose significant barriers. A holistic assessment must balance technical accuracy with stakeholders’ engagement and social acceptability.

7. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that the PED approach can be successfully applied to existing urban contexts, even those characterized by significant morphological and functional heterogeneity. The case studies of the Testaccio and Valco San Paolo districts provided the foundation for a rigorous technical-scientific evaluation, focused on the dynamic simulation of district energy behavior, the assessment of retrofit scenarios, and the verification of the technical and economic sustainability of proposed solutions. In both districts, the integrated implementation of a comprehensive set of interventions, including building envelope insulation, replacement of windows, upgrade of HVAC systems, lighting retrofitting, and large-scale deployment of PV systems, resulted in significant energy performance improvements. Specifically, electricity demand was reduced by 24.73% in Testaccio and 23% in Valco San Paolo, alongside the complete elimination of natural gas use for space heating. In both cases, annual PV electricity production exceeded the post-retrofit electricity demand, enabling the classification of both districts as PEDs.

District-level dynamic modeling played a critical role in designing and validating retrofit strategies, allowing for a detailed analysis of the interactions between energy demand and renewable energy supply. The calibration of simulation models using real consumption data and building thermo-physical characteristics ensured the robustness and reliability of the results, thereby making the proposed methodology highly replicable in other urban contexts with similar baseline conditions and sustainability goals. The integration of lithium-ion battery energy storage systems further enhanced PED performance by increasing the LCF and reducing reliance on the electrical grid. However, the analysis revealed the presence of an optimal storage capacity threshold beyond which marginal benefits decline sharply. For Testaccio, this threshold was identified at approximately 25,000 kWh, while in Valco San Paolo it was around 20,000 kWh. Proper sizing of storage systems is thus essential to maximize self-consumption without incurring excessive costs or environmental burdens.

Energy performance indicators such as the LCF and Grid Interaction Index provided valuable insights into the districts’ operational behavior over time, emphasizing critical issues related to the temporal mismatch between renewable energy production and consumption. Particular attention was paid to the management of surplus generation during summer months and the mitigation of peak energy exchanges with the grid, especially when solar generation significantly exceeds local demand. Despite structural differences between the two districts, such as building density, functional mix, rooftop PV potential, and seasonal load distribution, both demonstrated strong potential for PED conversion, provided that a context-specific and adaptive strategy was applied. This underscores the importance of tailored interventions that account for the distinct energy profiles and architectural typologies of each district. The successful transition toward PED status does not rely solely on the deployment of advanced technologies but also requires a robust regulatory and institutional framework, effective financial incentives, and inclusive governance models. Major challenges include high upfront investment costs, administrative complexity, and the need for coordinated action among multiple stakeholders [

52]. Nevertheless, the benefits offered by PEDs are substantial, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions, enhanced energy autonomy and security, and the development of new economic paradigms based on self-consumption, energy sharing, and community participation. This work provides a solid and transferable methodology that can serve as a reference for local authorities, urban planners, energy consultants, and policymakers engaged in the ecological transition of cities. The successful application of the PED model in the two Roman districts serves as concrete evidence of its scalability, offering a replicable framework to accelerate the urban energy transition at a metropolitan level and contributing meaningfully to climate neutrality targets, urban resilience, and energy justice.

However, the following work represents only an initial analysis of the potential of an existing and complex urban center like Rome and highlights the need for access to a range of data that is not always readily available. Future research should focus on optimizing energy storage management strategies, potentially incorporating second-life battery applications, assessing environmental impacts across the battery lifecycle, and integrating PEDs into broader urban energy ecosystems. Furthermore, photovoltaic system integration should be explored further, considering solar intermittency, the mismatch between generation and load curves, and real-time grid responsiveness. This should also include modeling or control strategies for load dispatchability.

Economic and environmental aspects, which are essential considerations for assessing long-term feasibility and sustainability, should also be explored, and a comparative interpretation of the results could guide a planner in planning the actions to be implemented. These considerations should include electric mobility, smart infrastructure, and shared energy services, with the aim of maximizing systemic impact and supporting the emergence of decentralized, sustainable, and participatory energy models.