Abstract

Extreme disasters such as typhoons pose severe frequency stability challenges to modern power systems with a high penetration of new energy sources. Traditional probabilistic power flow (PPF) methods, which assume constant frequency, are insufficient for accurately capturing these risks. This paper proposes a PPF assessment method for wind-integrated power systems that considers system frequency characteristics under typhoon disasters. First, a probability model of wind power output uncertainty under typhoon disasters is constructed based on the hybrid adaptive kernel density estimation (HAKDE) method. Next, the frequency response characteristics are explicitly introduced, with the steady-state frequency deviation utilized as the state variable for the PPF solution, and an extended cumulant method PPF model is thus established. This model can concurrently determine the probability distributions and statistical characteristics of nodal voltages, branch power flows, and the steady-state frequency of the system. Case studies on a modified IEEE 39-bus system demonstrate that the proposed method effectively quantifies frequency violation probabilities that are overlooked by traditional models.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the escalating global climate crisis has led to a heightened frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as typhoons and hurricanes, posing unprecedented threats to the secure and stable operation of modern power systems [1]. Typhoon disasters often trigger widespread damage to transmission and distribution infrastructure, resulting in the forced disconnection of generation units (particularly offshore and coastal wind farms) and large-scale load outages, thereby inducing significant power deficits and system imbalances [2]. Concurrently, to achieve global carbon neutrality goals, the penetration of new energy sources, primarily wind and solar power, has been rapidly increasing within power systems. However, while displacing conventional synchronous generators, high penetrations of new energy sources substantially reduce the system’s equivalent inertia and primary frequency response reserves, critically weakening the grid’s resilience against power disturbances and its ability to maintain system frequency stability [3,4]. Under typhoon disasters, the combined effect of high-wind turbine cut-outs due to protection mechanisms and drastic load fluctuations can easily induce severe active power imbalances, exposing the system to an extreme risk of frequency instability. In the extreme cases, these imbalances may cascade into frequency collapse and large-area blackouts [5]. Consequently, traditional steady-state security assessments, which focus exclusively on nodal voltages and branch power flows, are inadequate for evaluating system performance under typhoon disasters. There is a pressing need to develop advanced analytical methodologies capable of quantitatively assessing the probability of steady-state frequency deviations, thereby providing a more comprehensive decision-making basis for pre-disaster preventive control, emergency dispatch, and system planning.

The probabilistic assessment of wind-integrated power systems under typhoon disasters primarily revolves around two core research areas: uncertainty modeling of wind farm output and probabilistic power flow (PPF) computation.

Accurate characterization of the probability distribution of wind farm output during the extreme, non-stationary typhoon events is foundational. Existing modeling approaches can be broadly categorized into parametric and non-parametric methods. Parametric methods assume data conforms to predefined distributions, such as Weibull, Rayleigh [6,7] or Beta distributions [8]. While simple, they often struggle to capture the complex, multi-modal distribution shapes typical of typhoon-influenced data, often leading to significant fitting errors. To address this issue, multi-modal distributions, such as Gaussian mixture model (GMM) [9], offer greater flexibility yet still require pre-specification of the number of components, which limits their adaptability to rapidly evolving wind profiles during typhoon landfall and retreat. Non-parametric approaches, such as kernel density estimation (KDE) [10] and adaptive-bandwidth KDE [11,12], can better preserve distributional irregularities, however, their performance is highly sensitive to bandwidth selection and may deteriorate in mixed low and high wind states typical of typhoon passages. Moreover, capturing spatial correlations among wind farms is crucial. Approaches utilizing Copula theory [13,14,15] and other advanced tools such as Dirichlet process GMM (DPGMM) [16] and graph neural networks (GNNs) [17] have demonstrated effectiveness. However, existing non-parametric methods still face challenges in balancing smoothness and sensitivity when addressing the abrupt, extreme fluctuations associated with typhoon eyewalls.

It is known that the PPF is vital for analyzing the impact of uncertainties on system states. The mainstream methods include simulation-based methods, approximation methods, and analytical methods. Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) [18,19] provides statistical accuracy but becomes computationally prohibitive for high-dimensional uncertainty sets. Approximation methods, such as the point estimate method [20], often struggle to accurately capture the detailed characteristics of complex non-Gaussian distributions, and the computational burden increases with high-dimensional variables. In contrast, analytical methods, such as the cumulant method (CM) with Gram–Charlier expansion [21,22,23], significantly reduce computational burden. However, a fundamental assumption in traditional analytical PPF computation is that any active power imbalance is entirely absorbed by the slack bus, keeping the system frequency constant at its nominal value [24] This assumption becomes invalid in power systems with high new energy sources penetration subjected to large disturbances, as it ignores the inherent frequency response contributed by generator speed governors and load frequency dependencies. To address this issue, recent research has increasingly focused on frequency-aware power flow models. Studies have modified active power balance equations to incorporate generator droop and load damping [25,26,27,28], while others have employed importance sampling [29] and data-driven methods [30] to assess security risks. Some efforts have even utilized neural networks to predict transient frequency nadirs [31,32]. Despite these advancements, a research gap remains: existing frequency-aware frameworks predominantly focus on normal operating conditions or generic disturbances and seldom integrate uncertainty models specifically designed for the spatio-temporal characteristics of typhoons. Consequently, there is a need for a unified framework that combines typhoon uncertainty modeling with an analytical PPF model that considers frequency response to accurately quantify disaster-induced risks.

Bridging the identified research gaps, this paper proposes a comprehensive probabilistic assessment framework for evaluating frequency risk in wind-integrated power systems under typhoon disasters. The main contributions of this paper are threefold:

- (1)

- A novel hybrid adaptive kernel density estimation (HAKDE) method is proposed for uncertainty modeling of wind speed under typhoon scenarios. To address the non-linear and multi-modal characteristics of the wind power probability density function (PDF) during typhoons, a data-driven adaptive KDE technique is introduced to more accurately capture its statistical properties, providing a superior input model for the subsequent PPF computation.

- (2)

- An extended CM based PPF model is developed that explicitly incorporates frequency response characteristics. By reforming the system active power balance equations and the Jacobian matrix to include generator droop and load damping coefficients, the steady-state frequency deviation is introduced as an additional state variable. An analytical framework based on the CM and series expansion is then applied to efficiently compute the probability distributions and statistical characteristics of nodal voltages, branch power flows, and the system steady-state frequency simultaneously.

- (3)

- A complete assessment framework is constructed and validated. Simulation case studies are conducted using a modified IEEE 39-bus system integrated with multiple wind farms. Comparative analyses with traditional methods verify the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed model in assessing frequency risk under typhoon disaster scenarios.

The central hypothesis of this study posits that explicitly incorporating frequency response characteristics into the steady-state PPF framework enables efficient quantification of hidden frequency stability risks, which are typically masked by the swing-bus assumption in traditional models. Consequently, the primary objective is to develop a mathematically efficient assessment tool that integrates HAKDE-based typhoon uncertainty modeling with a frequency-aware PPF model. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the HAKDE-based uncertainty modeling for wind speed under typhoons. Section 3 elaborates on the extended PPF model considering frequency response and its solution framework via the CM. Case studies and results are presented and discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Uncertainty Modeling of Wind Speed Under Typhoon Disasters

2.1. Characteristics of Wind Speed Under Varying Typhoon Intensities

A typhoon, as an intense tropical cyclone, exhibits wind speed characteristics that are intrinsically linked to its intensity category, which shapes the speed patterns of wind farms. Classified according to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale [33] and World Meteorological Organization definitions [34], typhoons (or hurricanes/major tropical cyclones) can be categorized into several levels based on their maximum sustained wind speeds, including tropical depression, tropical storm, severe tropical storm, typhoon, severe typhoon, and super typhoon. Each level presents distinct wind speed distribution features, inducing different uncertainties in wind speed.

Tropical depression and tropical storm categories are characterized by relatively low maximum sustained winds, typically below 24 m/s. Their wind speed distributions are comparatively gentle, with variability higher than under normal weather conditions but generally remaining within the normal operating range of wind turbines. The probability distribution of wind speed often exhibits a unimodal shape, similar to the Weibull distribution for conventional wind speed, but with increased variance.

Regarding the severe tropical storm and typhoon, wind speeds intensify significantly, approximately between 24.3 and 41.4 m/s, accompanied by steeper wind speed gradients between the outer circulation and the core region. Wind speed time series demonstrate stronger non-stationarity and intermittent abrupt changes. While wind turbines can still operate at rated power within this range, frequent wind fluctuations cause drastic output variations. The output probability distribution begins to show slight skewness or even nascent multi-modal tendencies, reflecting the sudden wind shifts associated with the eyewall transition zone.

Severe typhoon and super typhoon, with wind speeds usually exceeding 49.4 m/s, feature complex structures with well-defined eyewalls, leading to highly non-uniform and sharply sheared wind speeds spatially. Temporally, wind speeds may undergo extreme fluctuations characterized by a sharp rise, a plateau during the eyewall passage, a brief calm period within the eye, and subsequent sharp rise. This characteristic induces extreme scenarios in wind farm output: an emergency shutdown (output plunging to zero) due to over-speed, potentially followed by a brief power recovery if the eye passes over, and then another shutdown. These intricate physical phenomena cause the probability distribution of wind speed to be pronouncedly non-Gaussian and multi-modal, with one mode corresponding to the zero-power state post-shutdown, and another mode (or other modes) associated with rated or partial power operation. Traditional parametric distribution models often struggle to accurately capture such complex distribution shapes.

Therefore, developing flexible, non-parametric probability models capable of adapting to distributions from unimodal to highly complex multi-modal forms is crucial for accurately assessing power system risk under typhoon disasters.

2.2. Principles of the HAKDE Method

To accurately capture the non-Gaussian, multi-modal probability distribution of wind speed under typhoon conditions, this study proposes a HAKDE method. KDE is a non-parametric density estimation tool that constructs a smooth PDF estimate by superimposing kernel functions centered on sample points. Given a set of independent and identically distributed samples , the standard KDE estimate of the PDF at point is:

where is the kernel function (typically the Gaussian kernel), is the sample size, and is the bandwidth parameter. The selection of is critical to KDE performance: a bandwidth that is too small leads to an undersmoothed estimate characterized by high variance and sharp oscillations, while an excessively large bandwidth causes oversmoothing, which can obscure the underlying structure of the true distribution.

Classical KDE using a fixed global bandwidth struggles to achieve satisfactory accuracy across all regions when applied to typhoon wind speed data, which exhibits drastically variable variance and contains both high-density and low-density regions. Advanced KDE typically incorporate weighting factors or adaptive bandwidths to improve estimation accuracy. However, each approach has inherent limitations: weighting factors can adjust the contributions of different regions but lack the flexibility of bandwidth adaptation, while adaptive bandwidths can enhance estimation in boundary and sparse regions but may lead to overfitting in high-density areas, where excessively small bandwidths may overfit local fluctuations.

To address these, the proposed HAKDE method integrates an adaptive bandwidth mechanism and a hybrid strategy, significantly enhancing its adaptability to the local characteristics of the data. The proposed HAKDE method begins by constructing an initial smooth density estimate using a global bandwidth , typically determined via rule-of-thumb methods such as Silverman’s rule [35]. For one-dimensional data, it is computed as follows:

where is the sample standard deviation, and is the sample size.

To account for differences in wind speed distributions under various meteorological conditions, a bandwidth adjustment factor is introduced to modify the bandwidth:

where is for normal wind data with small variance to increase smoothness, and is for typhoon data with larger variance and complex structures to enhance sensitivity to local variations.

Subsequently, the proposed HAKDE method incorporates locally adaptive bandwidths to meticulously capture distributional details. The Abramson method [36] is one of the classical approaches for this purpose. Based on an initial bandwidth and a given pilot density estimate , the locally adaptive bandwidth is defined as follows:

where is a sensitivity parameter, is the geometric mean of the sample densities, . This approach employs larger bandwidths in sparse data regions (e.g., clusters of zero-power points during typhoons) to avoid noisy estimates and smaller bandwidths in dense regions (e.g., clusters of rated-power points) to resolve fine structure, yielding the local density estimate .

However, relying solely on the local estimate can make it susceptible to errors in the initial pilot density and data noise. To mitigate this, this study proposes a hybrid strategy based on gradient consistency. The gradient consistency weighting is theoretically motivated by the bias-variance trade-off principle [35]. In KDE, the global estimate serves as a high-bias, low-variance reference, while the local estimate acts as a low-bias, high-variance refinement. The weighting strategy utilizes the consistency of gradients as a proxy for structural stability to optimize the local mean squared error (MSE):

This strategy evaluates the consistency between the global estimate and the local estimate at point by comparing their gradients (in 1D) or gradient directions (in multi-D).

In one-dimensional space, a stability index is defined as follows:

where and represent the smoothing gradients of the global and local estimates at location , respectively. A larger value indicates stronger consistency in the local trend between the two estimates. Based on this metric, the weights are determined as follows:

where is a very small positive number, denotes the weight assigned to the local density estimate, and represents the weight assigned to the global density estimate. The final HAKDE is given by:

This fusion ensures that greater trust is placed in the sensitive local model in regions where the estimates agree highly, while the stability of the global model is retained in regions of significant discrepancy, thus achieving an optimal balance between smoothness and sensitivity overall.

The method can be naturally extended to multi-dimensional cases (e.g., considering the outputs from multiple wind farms simultaneously). For d-dimensional data, the bandwidth becomes a bandwidth matrix , and a multivariate Gaussian kernel is typically used [37]:

where is a symmetric positive definite bandwidth matrix. The local bandwidth matrix in HAKDE method can be expressed as:

where is a local scaling factor, denotes the initial bandwidth matrix, and serves as a regularization term to ensure numerical stability.

The core of the hybrid strategy remains evaluating consistency via the cosine of the angle between multidimensional gradient vectors:

where is the gradient vector of the local density estimate at point , is a small positive constant ensuring numerical stability.

To guarantee non-negative weighting, we take:

In summary, the key advantage of the HAKDE method lies in its ability to model complex distributions without assuming specific distributional forms. By employing dual adaptive mechanisms (bandwidth adaptation and estimate fusion adaptation), the HAKDE method effectively captures the complex, multi-modal, and heavy-tailed probability distributions of wind speed under extreme events such as typhoons, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent high-precision PPF calculations.

3. PPF Model Incorporating Frequency Characteristics Using CM

3.1. Traditional Cumulant-Based PPF Model

The CM, as an efficient analytical approach within PPF models, leverages the logarithmic properties of the moment generating function and the additivity of cumulants. This allows it to effectively avoid complex multi-dimensional convolution operations, achieving a favorable balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. Consequently, the CM is particularly suitable for probabilistic analysis of large-scale systems.

Traditional PPF model is built upon the foundation of deterministic power flow calculations. For a n-bus system, the nodal power balance equations are:

where and represent the active and reactive power generation at bus i, while and denote the active and reactive power loads at bus ; and are the voltage magnitude and phase angle at bus ; ; and and are the real and imaginary parts of the element in the nodal admittance matrix.

Aggregating the active and reactive power injections of PQ buses and the active powers of PV buses into an input power vector , and the voltage magnitudes of PQ buses and the phase angles of all PQ and PV buses into a state variable vector , the power flow equations can be compactly expressed as:

Linearizing this set of nonlinear equations around a given base operating point yields:

where , , and is the Jacobian matrix at the operating point. The increments of the state variables can be determined as follows:

where is the sensitivity matrix. Similarly, the relationship between branch power flow perturbations and state variables is , where is the derivative matrix of branch powers with respect to state variables. Consequently, the relationship between and is:

where .

The essence of the CM lies in utilizing the additivity of cumulants under linear transformation. Assuming that the cumulants of the input random variables () of various orders , denoted as , are known, the cumulants of the output state variables and branch powers can be derived through the following linear transformations:

where the symbol denotes a generalized product between matrix and vector. After obtaining the cumulants of the output quantities, the PDF and cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the nodal voltages, phase angles, and branch powers can be reconstructed using Gram-Charlier expansion [38].

However, the traditional cumulant-based PPF relies on a critical assumption: any active power imbalance in the system is entirely absorbed by the designated slack bus, and the system frequency remains constant at its nominal value . This assumption becomes invalid in modern power systems with high penetration of new energy and susceptibility to large disturbances.

3.2. Incorporation of Frequency Response Characteristics and Model Extension

Large-scale wind turbine cut-offs and load fluctuations triggered by extreme disasters such as typhoons can cause significant active power deficits. The traditional model fails to capture the primary frequency regulation characteristics of synchronous generators and the self-regulating effect of loads during such events. This leads to an inability to assess system frequency stability and potentially severely overestimates the imbalance power that the slack bus must accommodate, rendering the results physically implausible.

To address this limitation, this paper incorporates system frequency response characteristics to extend the traditional power flow model. The core of this extension involves introducing the system steady-state frequency deviation as a new state variable within the power flow equations, thereby explicitly capturing the frequency regulation effects of both generators and loads.

When a power disturbance causes the frequency to deviate from its nominal value, the active power outputs of generators and the load demands adjust accordingly. The active power output adjustment characteristic of a generator can be described by its droop coefficient (or its inverse the frequency-sensitivity of the generator i ):

where is the initial setpoint power of generator at nominal frequency. Similarly, the active power of a load typically decreases with frequency drop, and its frequency-dependent effect can be expressed as:

where is the active power of load at nominal frequency, and denotes the frequency-sensitivity of the load j. Therefore, the net active power injection at bus can be revised as:

where is the net injection at nominal frequency, and is the network transfer power. The total active power imbalance is shared by all generators and loads in the system:

where denotes the system’s equivalent frequency regulation effect coefficient.

Based on the above principles, the traditional power flow model is extended. The new state variable vector incorporates the system frequency (or ) in addition to the original voltage magnitudes and phase angles :

Correspondingly, the power balance equations are extended to . Linearizing around the new equilibrium point yields the following extended linearized equation:

where is the extended Jacobian matrix, which has increased dimensions and includes new elements related to the frequency variable. The extended sensitivity matrix is . During the computation, a condition number check is performed for the extended Jacobian matrix in each iteration to ensure numerical robustness under high renewable penetration. If the reciprocal condition number falls below a threshold of , the matrix is identified as singular, indicating potential voltage collapse or numerical instability, and the solver terminates for that specific sample. Thus, the linear relationship between state variable perturbations and injection power perturbations is given by:

The relationship between branch power perturbations and injection perturbations is similarly extended to , where , and is the extended branch power derivative matrix.

The CM can now be applied to this extended model. The cumulants of the input random variables (e.g., wind power output and load fluctuations) are transformed via the linear operators and to obtain the cumulants of various orders for the extended state variables (including ) and branch powers:

The probability distributions of the nodal voltages, phase angles, branch powers, and can be obtained simultaneously through series expansion.

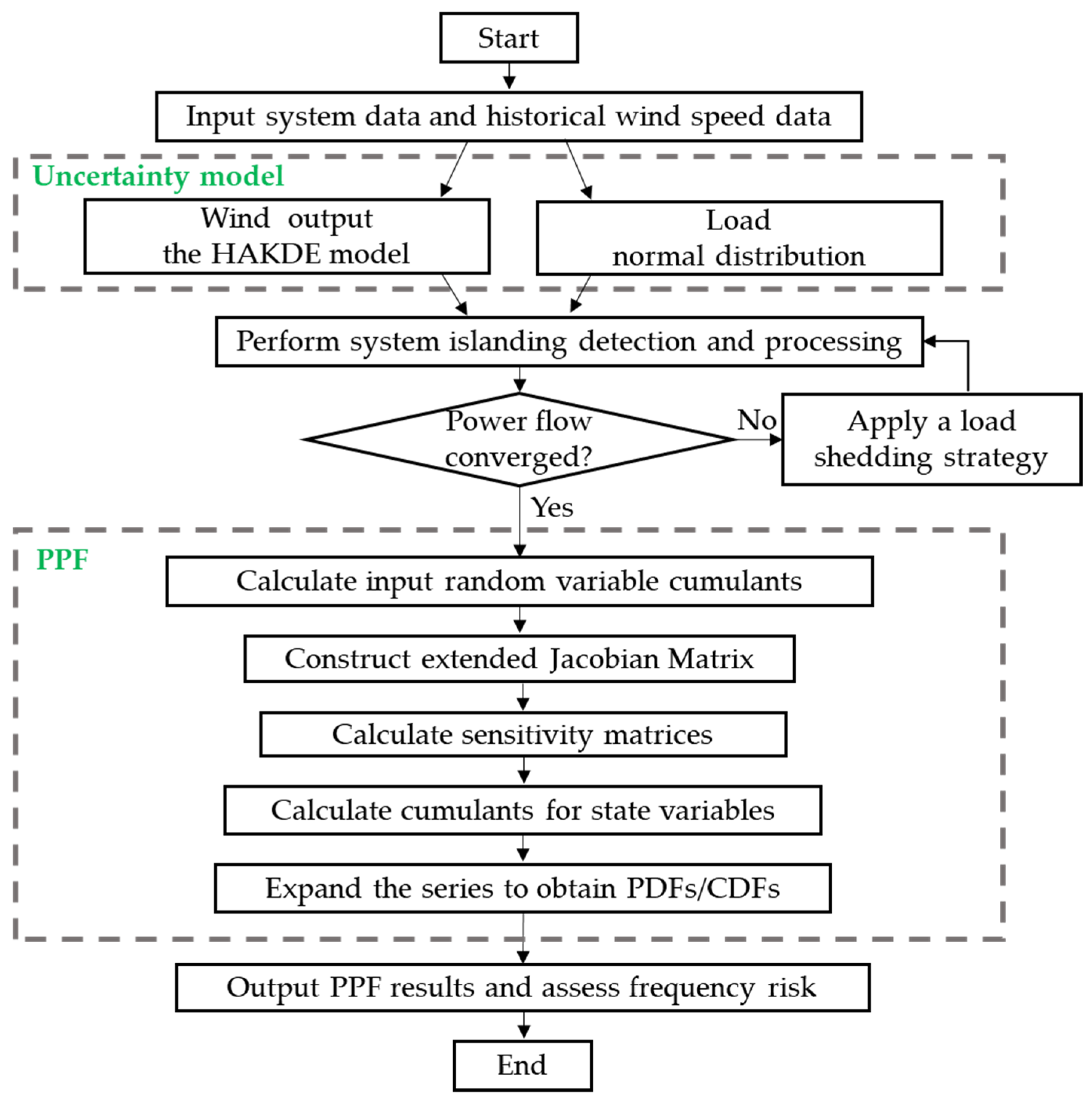

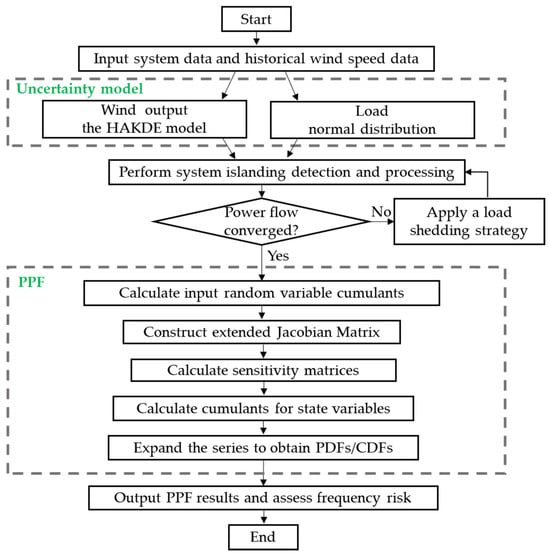

The computational procedure of the proposed frequency-aware PPF based on the CM is illustrated in Figure 1, and can be summarized in the following steps:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed frequency-aware PPF based on the CM.

- Input system data, including network topology, generator parameters, load profiles, and historical wind speed data.

- Wind power uncertainty is modeled using the HAKDE model, while load uncertainty is modeled using a normal distribution.

- Detect any network islanding caused by line outages. If islands exist, reconfigure the subsystems and assign a new slack bus for each island.

- If the power flow fails to converge, proceed to load shedding (Step 5); otherwise, continue to Step 6.

- Apply a load shedding strategy to restore solvability and return to Step 3.

- Calculate the cumulants of input random variables using their probabilistic models.

- Construct the extended Jacobian matrix.

- Calculate the sensitivity matrices that link input uncertainties to output variables.

- Calculate the cumulants of all output variables (voltages, branch flows, and ) using the sensitivity matrices and the additivity property of cumulants.

- Reconstruct the PDFs and CDFs of the output variables using the Gram-Charlier expansion.

- Analyze the probabilistic results and evaluate frequency risk, including calculating the probability of frequency limit violations.

4. Case Studies

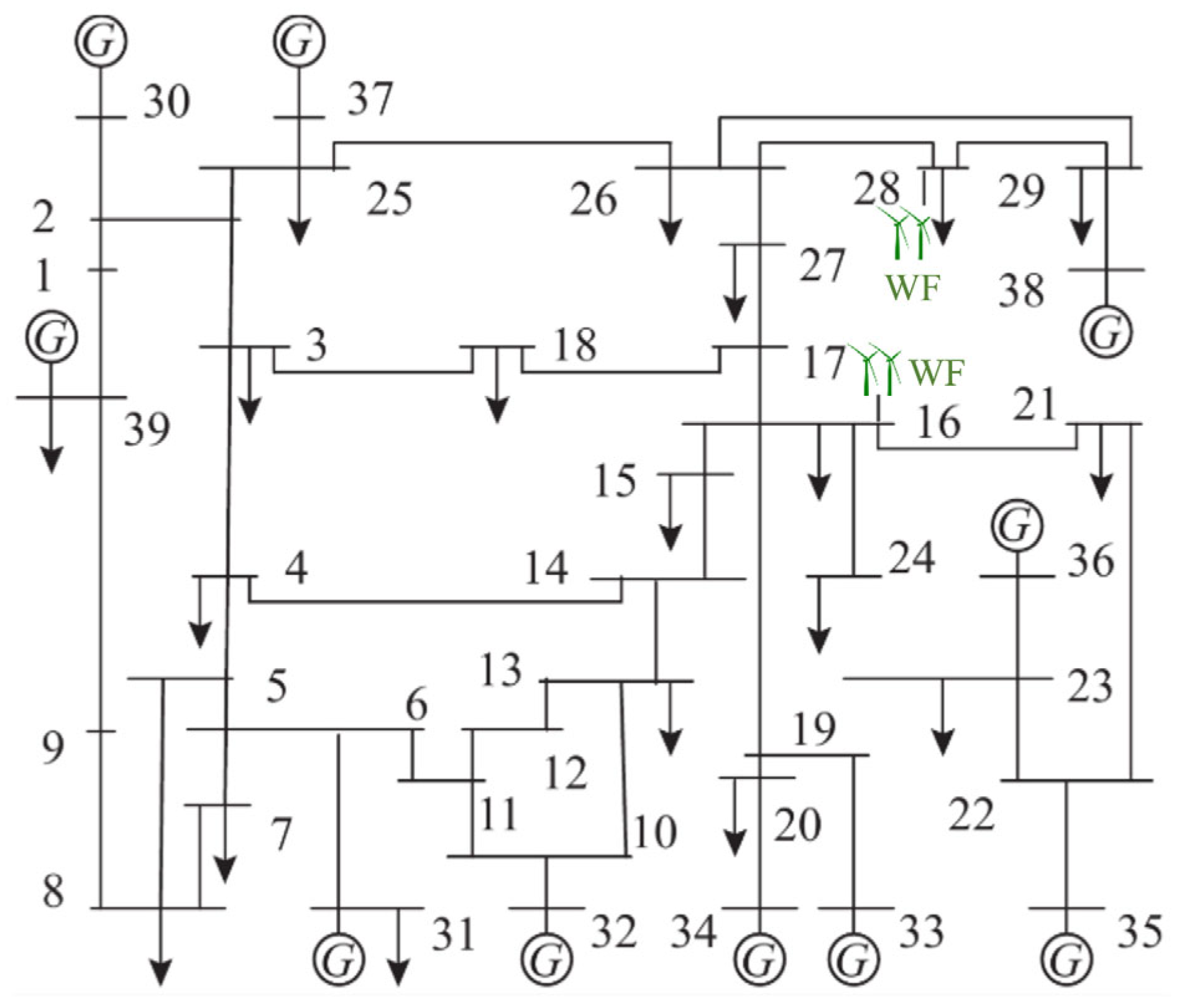

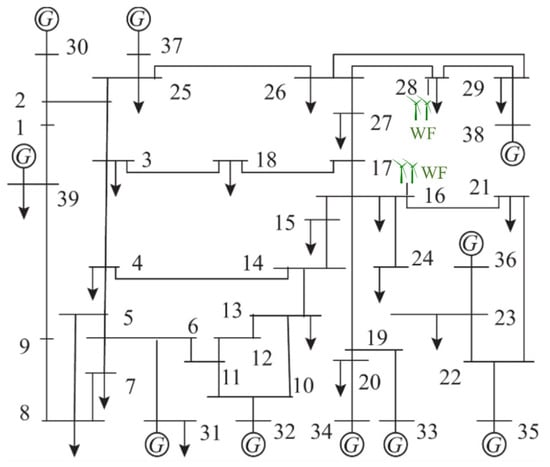

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed probabilistic assessment framework, simulation analyses are conducted based on a modified IEEE 39-bus system whose topology and component parameters can be found in [39], as shown in Figure 2. The original conventional generators at bus 16 and bus 28 are replaced with two wind farms (labeled as ‘WF’) with capacities of 573 MW and 650 MW, respectively, resulting in a wind power penetration level of approximately 20%. The cut-in, cut-out, and rated wind speeds for the turbines are set to 4 m/s, 25 m/s, and 9.8 m/s [40], respectively. Load demand is treated as a random variable following a normal distribution with a standard deviation equal to 10% of its mean. For frequency response modeling, wind farms are assumed to provide no frequency support, while all other synchronous generators participate in primary frequency regulation with a unified set to 25 p.u. The value of describing the frequency sensitivity of load is set to 1.5 p.u. [41].

Figure 2.

Single-line diagram of the modified IEEE-39 bus system with wind farms.

4.1. Validation of the HAKDE Model

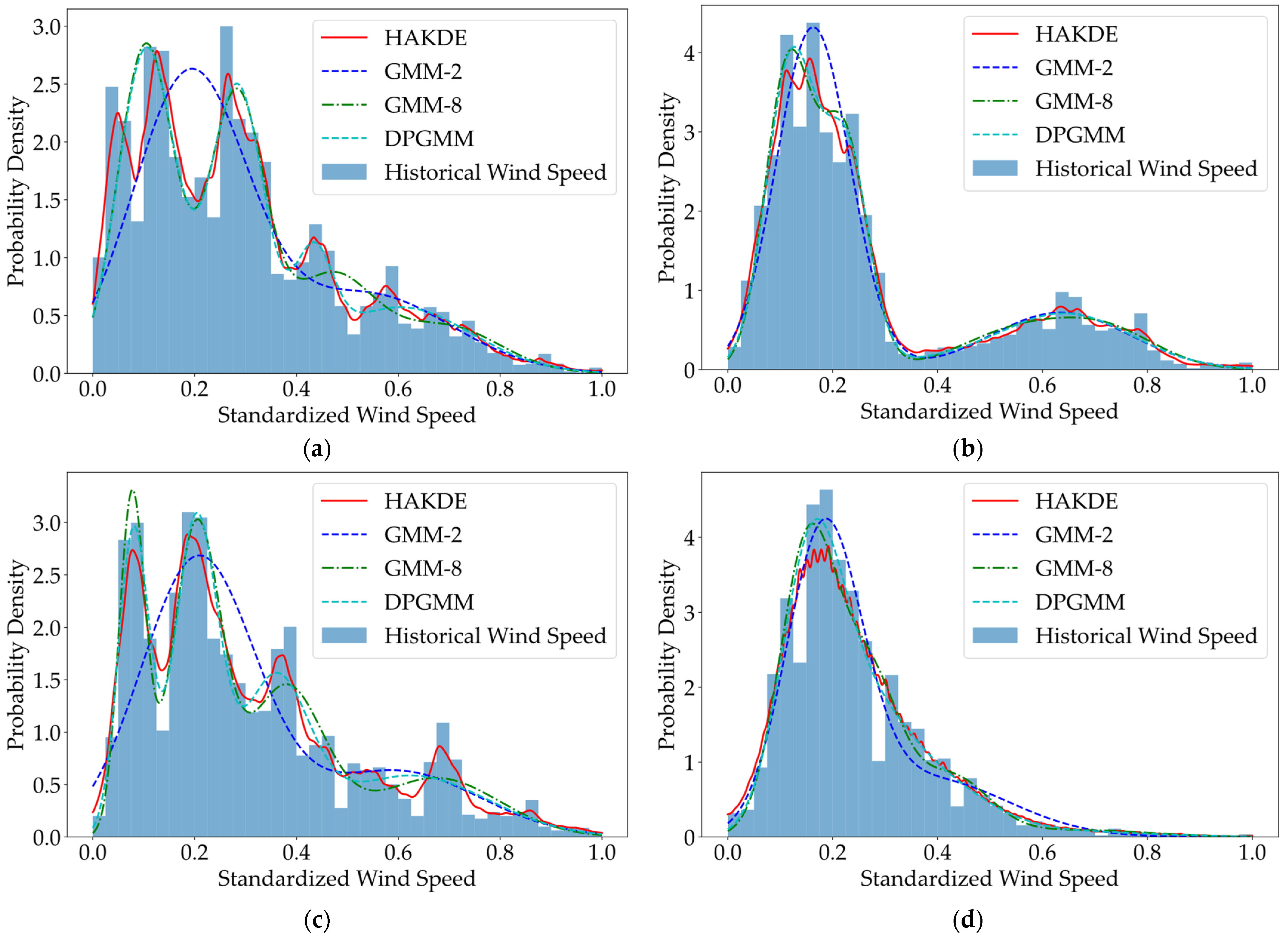

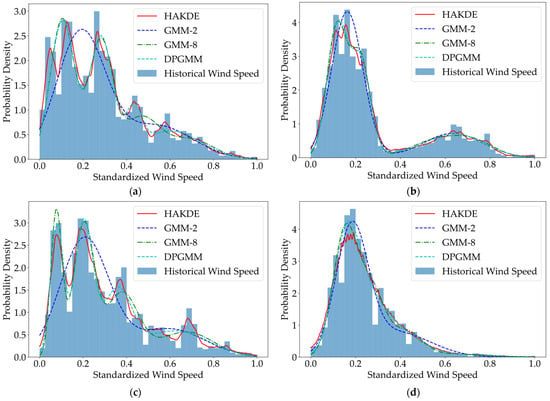

This section aims to validate the superiority of the proposed HAKDE method in characterizing wind power uncertainty under typhoon disasters. Wind speed data set from a meteorological station in Southern China, encompassing Typhoon Mangkhut (Super Typhoon), Typhoon Nida (Strong Typhoon), Typhoon Merbok (Severe Tropical Storm), and a normal wind period, is used as samples. For comparison, the second-order GMM (GMM-2), the eighth-order GMM (GMM-8), and DPGMM are also employed. As mentioned before, the DPGMM, as a non-parametric Bayesian method, automatically determines the optimal number of mixture components from the data, giving it an inherent advantage in handling complex distributions.

The fitting results of the four methods under different wind conditions are compared in Figure 3. To quantitatively evaluate the goodness-of-fit, two statistical metrics are used: the average log-likelihood (higher is better, indicating better overall fit) and the chi-square goodness-of-fit (lower is better, indicating smaller discrepancy from the empirical distribution). The results are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Performance comparison of the four methods for typhoon Mangkhut; (b) Performance comparison of the four methods for typhoon Nida; (c) Performance comparison of the four methods for typhoon Merbok; (d) Performance comparison of the four methods for normal wind.

Table 1.

Average log-likelihood comparison of different methods.

Table 2.

Chi-square goodness-of-fit comparison of different methods.

As evidenced by Figure 3 and Table 1 and Table 2, the HAKDE model demonstrates the best fitting performance in most scenarios. Particularly, under typhoon conditions, the HAKDE model accurately captures the multi-modal and tail characteristics of the wind speed distribution, whereas the GMM methods tend to over-smooth or underfit. Statistically, the HAKDE model achieves the highest average log-likelihood across all scenarios; its chi-square goodness-of-fit value is the lowest for the three typhoon scenarios, only slightly higher than the DPGMM for the normal wind case. These results robustly demonstrate HAKDE’s strong capability in handling the complex, non-Gaussian wind speed distributions induced by typhoons. In the tables, the values corresponding to the highest average log-likelihood and the lowest chi-square goodness-of-fit are bolded to indicate superior fitting performance. Additionally, the entries with shorter computation times are also bolded to highlight higher computational efficiency. This bolding convention is applied to all subsequent tables.

Table 3 further compares the computational efficiency of the HAKDE model and DPGMM. The results show that the HAKDE model is generally faster than the DPGMM, with a more pronounced advantage under normal wind and Typhoon Merbok conditions, highlighting its ability to combine high modeling accuracy with superior computational efficiency.

Table 3.

Comparison of computational efficiency for different methods (s).

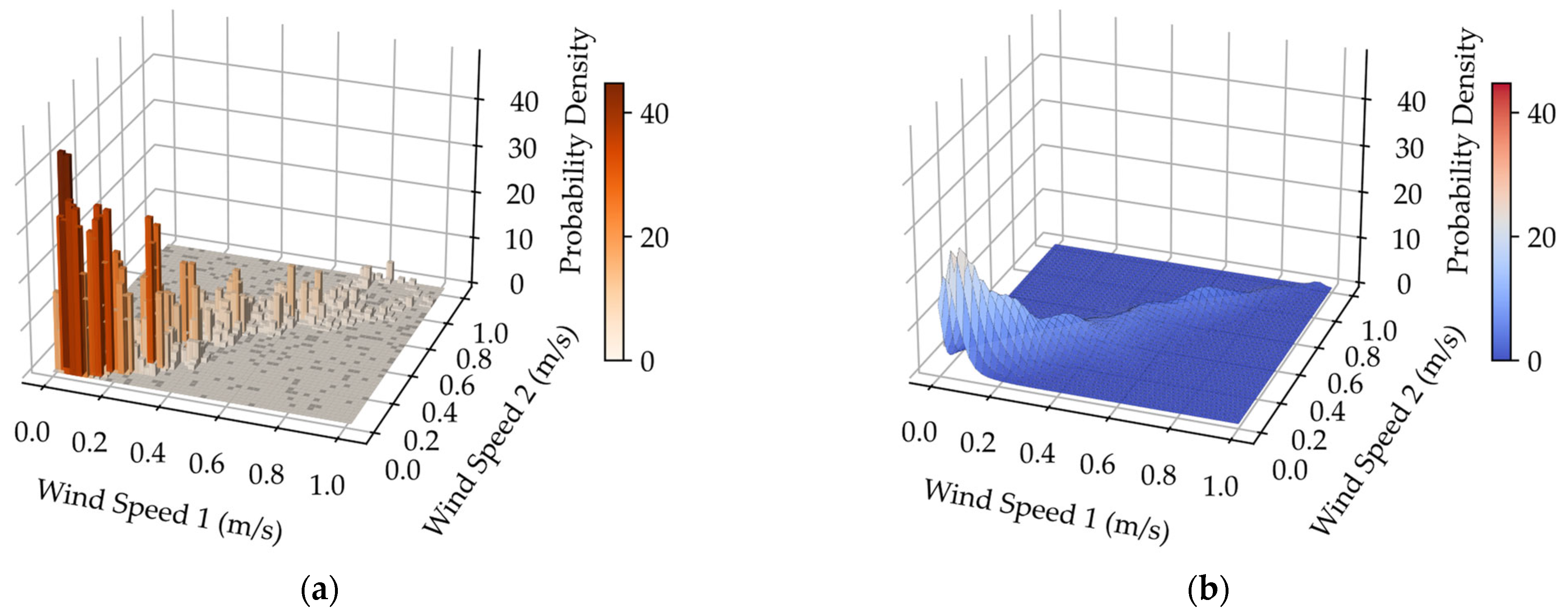

4.2. Joint Probability Density Modeling of Outputs of Multiple Wind Farms

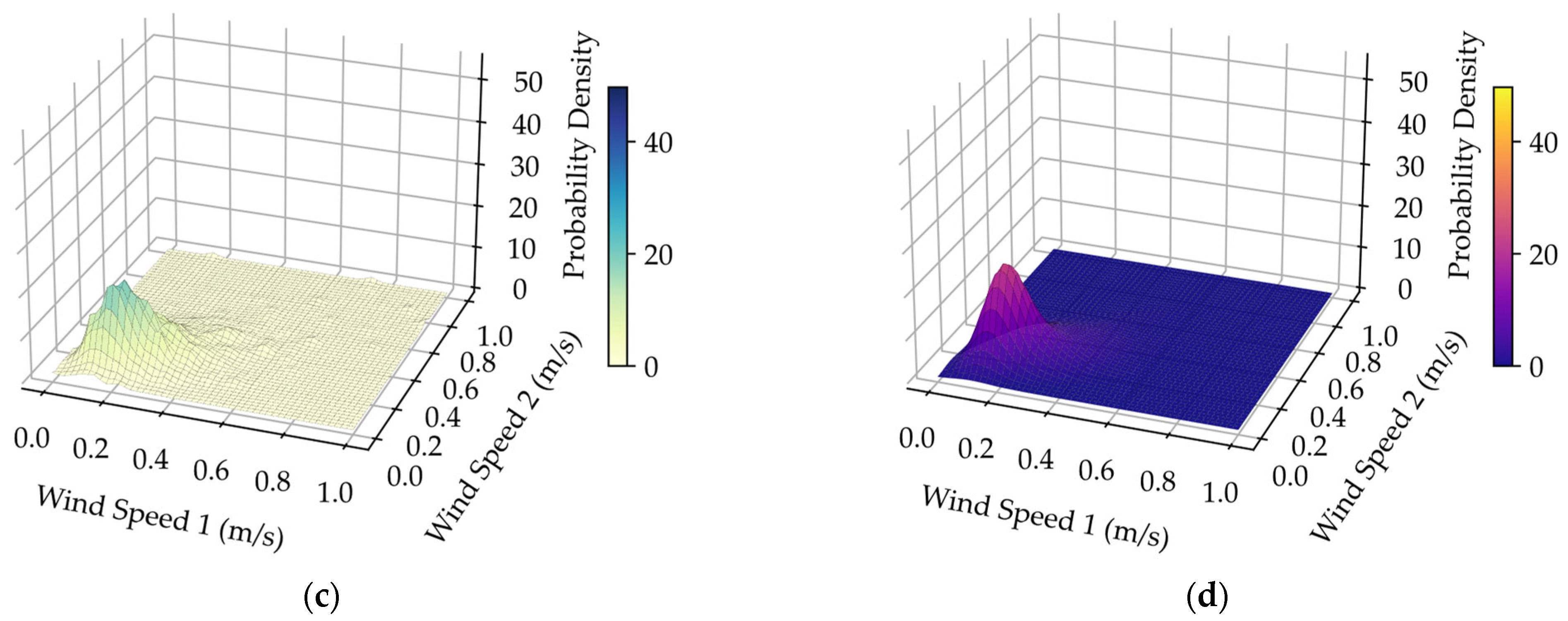

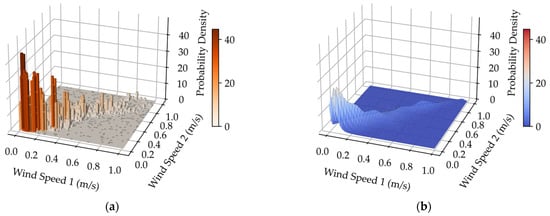

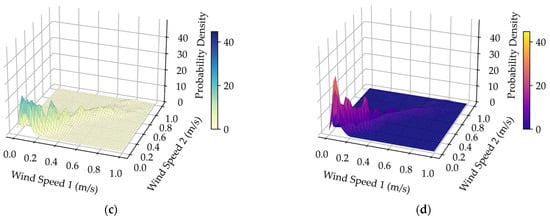

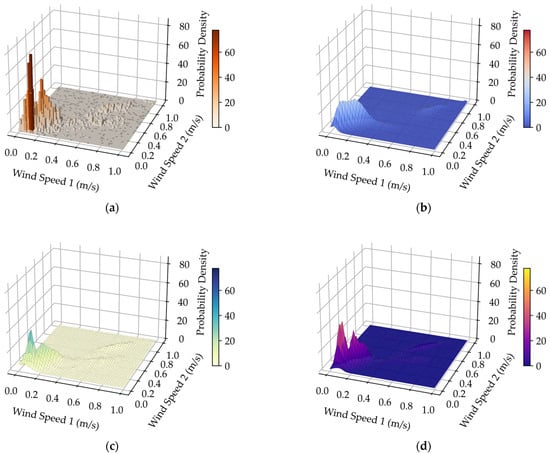

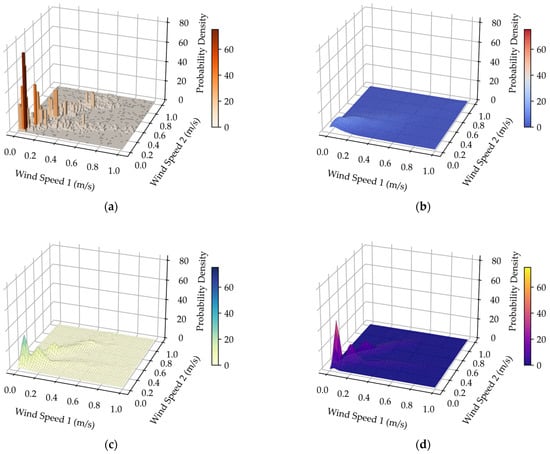

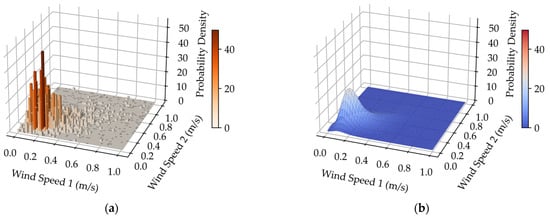

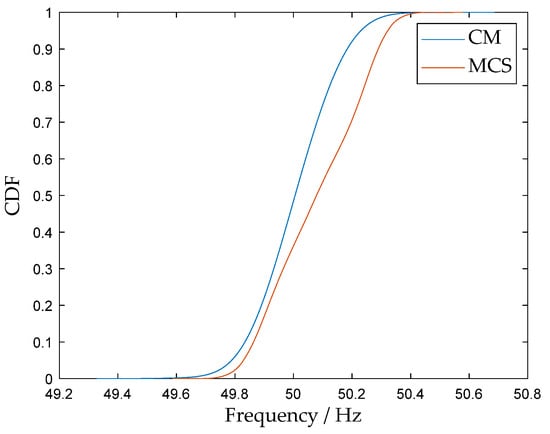

In practical systems, speeds of geographically close wind farms are correlated. This section uses synchronized wind speed data from two neighboring meteorological stations to validate the performance of the HAKDE model in multi-dimensional joint probability density modeling, comparing it against the optimal Copula function [42] (selected based on the minimum Euclidean distance criterion) and DPGMM. The 3D joint probability density fitting results under different wind conditions are depicted in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 4.

(a) Joint frequency histogram for typhoon Mangkhut; (b) Joint probability density fitting performance of the Copula method for typhoon Mangkhut; (c) Joint probability density fitting performance of the HAKDE model for typhoon Mangkhut; (d) Joint probability density fitting performance of DPGMM method for typhoon Mangkhut.

Figure 5.

(a) Joint frequency histogram for typhoon Nida; (b) Joint probability density fitting performance of the Copula method for typhoon Nida; (c) Joint probability density fitting performance of the HAKDE model for typhoon Nida; (d) Joint probability density fitting performance of DPGMM method for typhoon Nida.

Figure 6.

(a) Joint frequency histogram for typhoon Merbok; (b) Joint probability density fitting performance of the Copula method for typhoon Merbok; (c) Joint probability density fitting performance of the HAKDE model for typhoon Merbok; (d) Joint probability density fitting performance of DPGMM method for typhoon Merbok.

Figure 7.

(a) Joint frequency histogram for normal wind; (b) Joint probability density fitting performance of the Copula method for normal wind; (c) Joint probability density fitting performance of the HAKDE model for normal wind; (d) Joint probability density fitting performance of DPGMM method for normal wind.

Visually, both the HAKDE model and DPGMM produce distribution surfaces that closely match the histogram of the data, outperforming the Copula method. Table 4 lists the average log-likelihood values for each method, with the HAKDE model achieving the highest likelihood values across all typhoon scenarios except under normal wind. This indicates HAKDE’s superior ability to accurately model the complex dependency structures between wind farms. The comparatively lower performance of the Copula method highlights its limitations in capturing nonlinear and asymmetric correlations.

Table 4.

Comparison of average log-likelihood for multi-wind-farm modeling.

The comparison of computational efficiency given in Table 5 shows that, for the 2D case, the HAKDE’s efficiency is slightly lower than that of the DPGMM under typhoon conditions but higher under normal wind conditions. To further investigate high-dimensional performance, the analysis is extended to 3 and 4 dimensions using Typhoon Mangkhut data, with results shown in Table 6. The HAKDE model maintains significantly better fitting accuracy (higher log-likelihood) than DPGMM in these higher dimensional scenarios. Although the computation time increases, it remains within acceptable limits. These findings demonstrate the HAKDE’s potential and advantage in handling high-dimensional, complex correlation structures.

Table 5.

Comparison of computational efficiency for 2D modeling (s).

Table 6.

Comparison of high-dimensional modeling performance for typhoon Mangkhut.

4.3. Probabilistic Power Flow Results and Model Validation

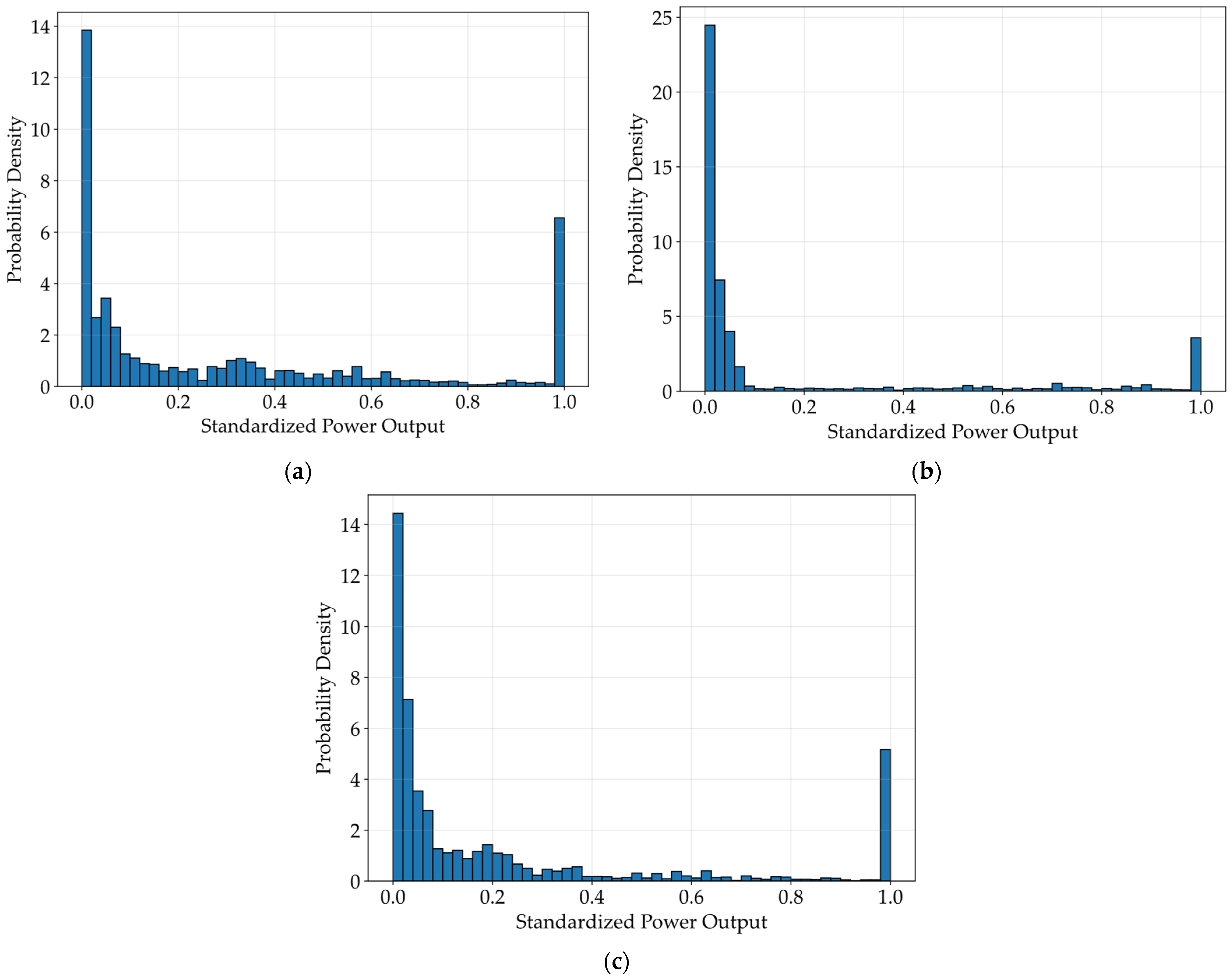

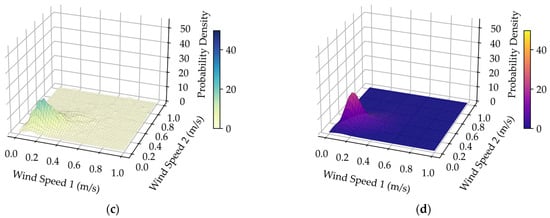

As illustrated in Figure 8, wind power output under typhoons typically follows a bi-modal mixed distribution. This distribution is characterized by significant probability mass at both zero output, resulting from cut-out wind speed, and at the rated power (Pr), with a continuous distribution spanning the operational range between these modes. This mixed distribution characteristic is modeled for calculating the cumulants of wind power when applying the CM.

Figure 8.

(a) The wind power output distribution histogram of typhoon Mangkhut; (b) The wind power output distribution histogram of typhoon Nida; (c) The wind power output distribution histogram of typhoon Merbok.

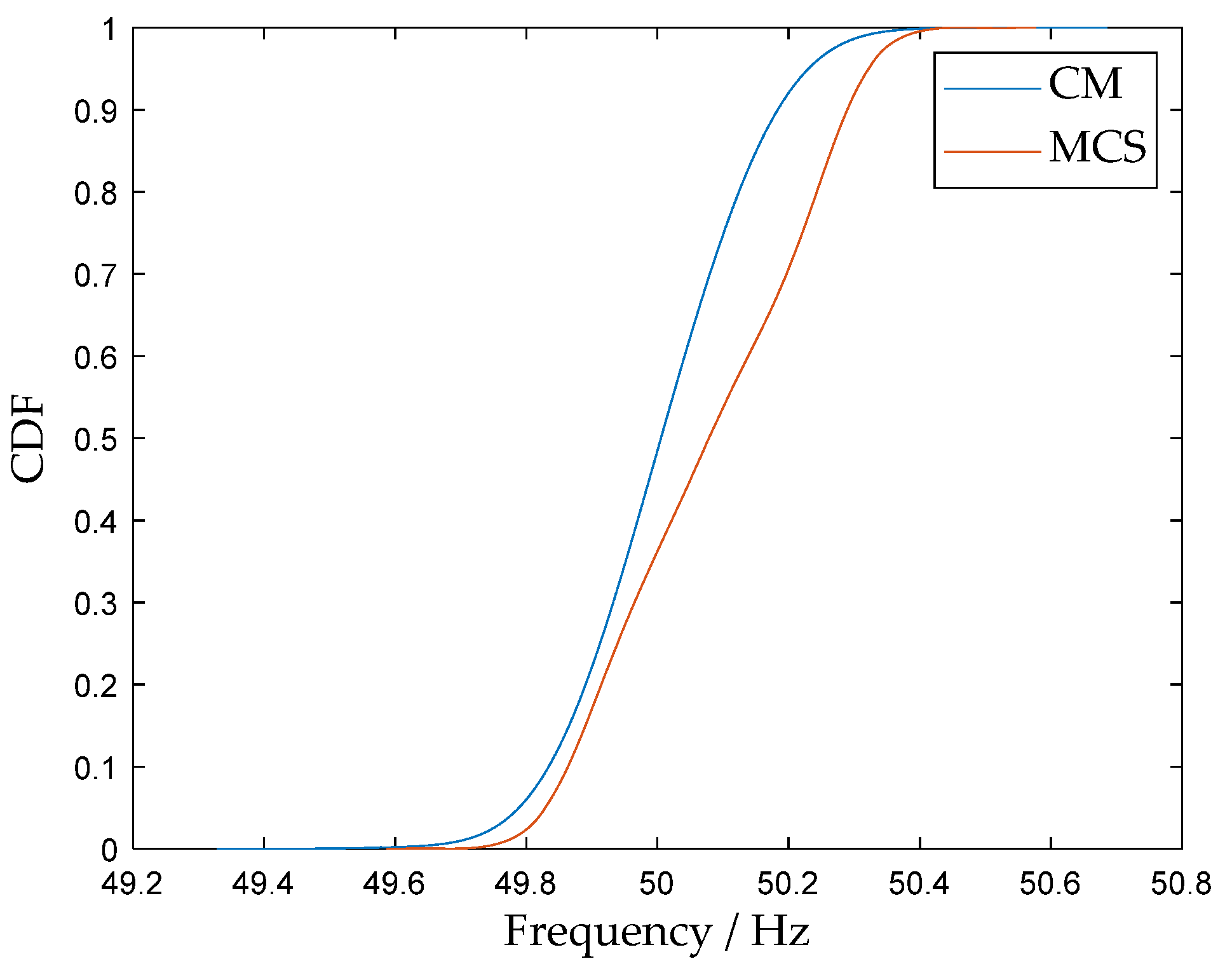

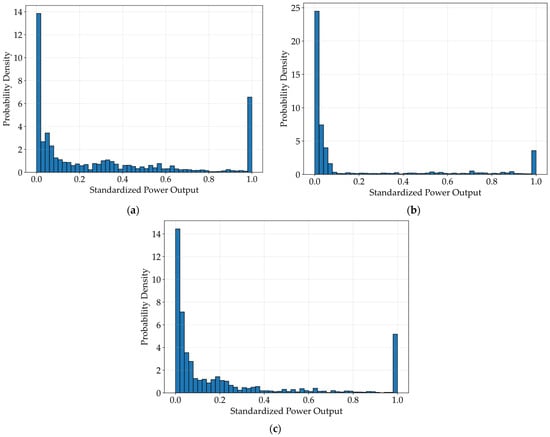

To validate the correctness of the proposed frequency-aware CM, results from 20,000 MCS are used as a benchmark.

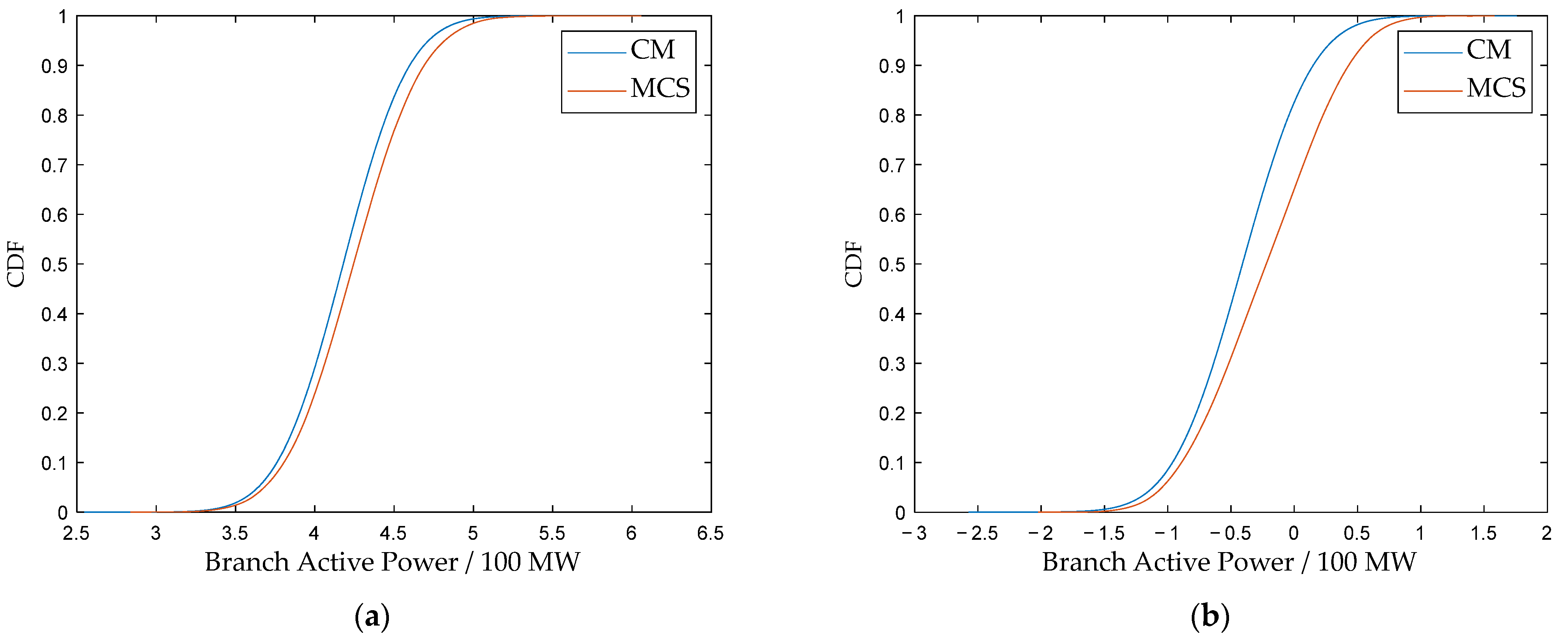

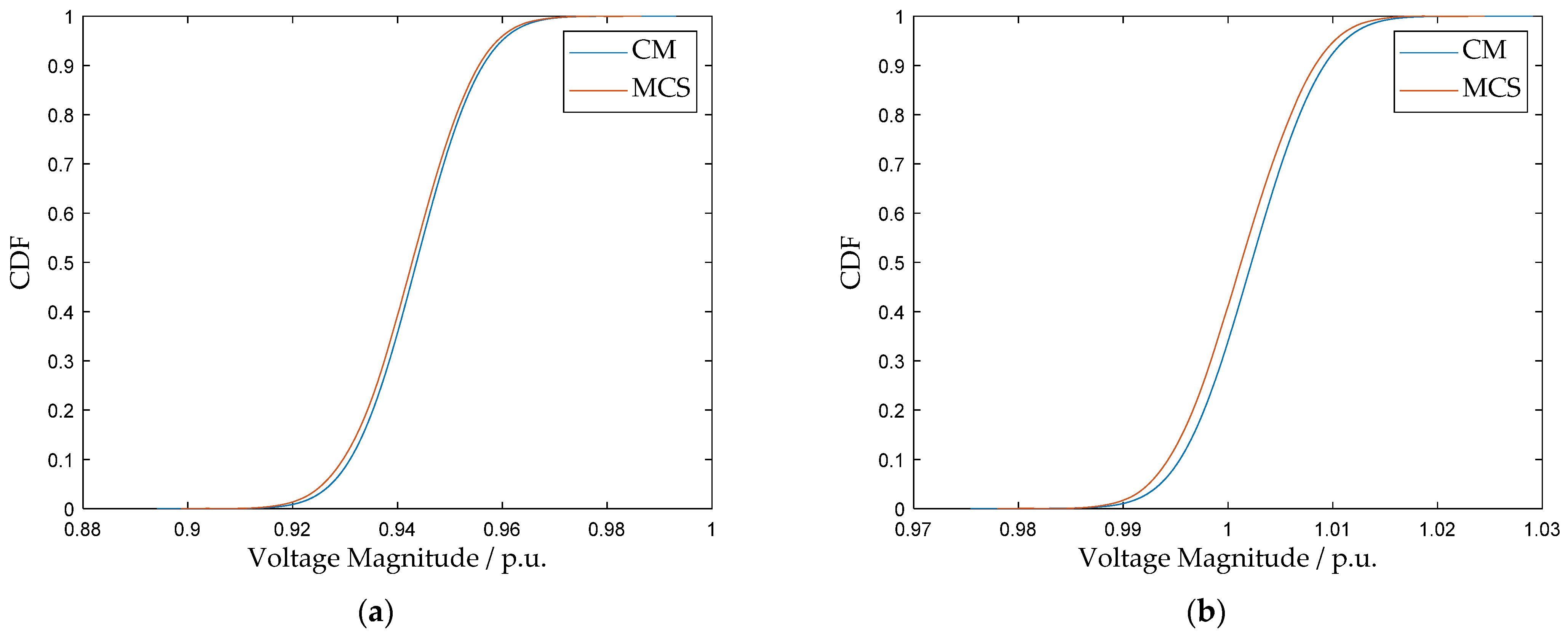

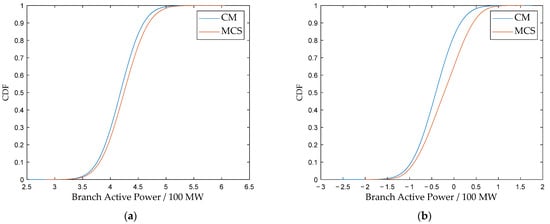

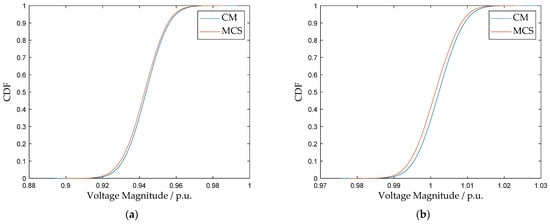

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the CDFs of the system frequency, selected branch active power flows, and nodal voltage magnitude, respectively. For quantitative accuracy assessment, the average root mean square () is adopted as the metric. Assuming comparison points, with the CDF values from the CM and MCS at the l-th point denoted as and , respectively, the is calculated as [43]:

Figure 9.

CDF comparison of system frequency: CM vs. MCS.

Figure 10.

(a) CDF comparison of active power in branch 6–7: CM vs. MCS; (b) CDF comparison of active power in branch 16–24: CM vs. MCS.

Figure 11.

(a) CDF comparison of voltage magnitude at bus 7: CM vs. MCS; (b) CDF comparison of voltage magnitude at bus 16: CM vs. MCS.

The values for the normal scenario are summarized in Table 7. All values are at a low level, indicating a high degree of consistency between the CM and the MCS benchmark. Although a minor deviation exists in the frequency CDF ( of 1.15 × 10−2), this error is considered acceptable for engineering applications, given the inherent significant uncertainty associated with typhoon disaster forecasting. Regarding the computational efficiency, the CM method demonstrates a substantial advantage: with 20,000 random samples, MCS requires an average of 55.09 s, whereas CM completes the calculation in only 0.38 s, achieving over two orders of magnitude improvement in computational efficiency. These results verify the potential of the proposed model to support online or rapid risk assessments while maintaining high accuracy.

Table 7.

Comparison of ARMS values between CM and MCS under normal scenario.

4.4. Contingency Analysis and Impact of Wind Power Penetration Level on System Frequency

4.4.1. Contingency Analysis

Based on the base case, the N-1 line outage contingencies are simulated for all transmission lines to assess system vulnerability under disturbance conditions. To focus on critical risks, Table 8 summarizes the scenarios where the line outage resulted in a higher frequency violation probability compared to the intact system. Outages with negligible impact on frequency risk are omitted for brevity.

Table 8.

Impact of line outages on system frequency.

The results indicate that different line failures affect the system frequency to different degrees. Some line outages cause an increase in its standard deviation, leading to a substantial rise in the frequency violation probability. For instance, the outages of lines 28–29 and 16–19 both result in significant frequency drops below 50 Hz, with violation probabilities rising to 70.0% and 42.1%, respectively. This reveals the severe frequency stability risk faced by the system under typhoon disasters due to a weakened network structure. Concurrently, the PPF results also show that these disturbances lead to increased nodal voltage fluctuations and branch power flow redistribution, heightening the risk of local voltage violations and line overloads.

4.4.2. Impact of Wind Power Penetration Level on System Frequency

The impact of wind power penetration level on system frequency security is analyzed by adjusting the installed capacity of wind farms, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

System frequency metrics under different wind power penetration levels.

As wind penetration level increases from 20% to 40%, the system inertia and primary frequency regulation capacity provided by synchronous generators decrease comparatively. This reduction impairs the system’s ability to withstand power disturbances, as evidenced by the frequency standard deviation nearly doubling from 0.1358 to 0.2515. Consequently, the system frequency violation probability rises sharply from 13.94% to 44.40%. Physically, this degradation in frequency stability can be attributed to the reduction in the system’s equivalent frequency response constant, . As synchronous generators are displaced by wind farms (which are assumed not to participate in regulation), the total decreases. According to the steady-state frequency relationship , a smaller results in a larger frequency deviation for the same magnitude of active power imbalance. These results clearly indicate that power disturbances triggered by typhoons in systems with high wind penetration level pose an extremely high risk of frequency instability, which must be carefully addressed in system planning and operation.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the critical challenge of security assessment for power systems with high wind power penetration under typhoon disasters, particularly focusing on the risk of frequency instability. A probabilistic assessment framework integrating the HAKDE uncertainty model and an extended probabilistic power flow model incorporating frequency characteristics is proposed and validated. Building on the case studies, the primary conclusions are summarized as follows:

- The proposed HAKDE method demonstrates a superior capability to capture the complex, non-Gaussian, and multi-modal probability distribution of wind power output under the influence of typhoons with different intensities. Its dual adaptive mechanism (bandwidth and fusion) provides a data-driven and robust foundation for the subsequent probabilistic analysis, overcoming the limitations of traditional parametric methods.

- The results quantitatively reveal the probabilistic characteristics of under various typhoon scenarios. The key findings are that the risk of frequency limit violations escalates significantly with increasing wind power penetration level and the severity of the disturbance.

The proposed framework provides an efficient analytical tool for assessing system frequency security risks in extreme weather events, enabling a more comprehensive security evaluation perspective.

It should be noted that this study primarily focuses on steady-state frequency deviations governed by primary frequency regulation. Investigating transient frequency metrics under large disturbances requires time-domain simulations, which will be the focus of our future work. Future research could build on this foundation by integrating the quantified frequency risk into preventive scheduling and reserve optimization models. This could involve the development of risk-based stochastic optimization frameworks to co-optimize energy dispatch, spinning reserve, and frequency regulation resources prior to a typhoon making landfall, ultimately enhancing system preparedness and resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and L.S.; methodology, A.H. and L.S.; software, A.H.; validation, A.H. and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tu Liang and his colleagues from China Southern Power Grid Electric Power Research Institute for their valuable comments and strong support in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P. The grid: Stronger, bigger, smarter?: Presenting a conceptual framework of power system resilience. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2015, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, D.; Zhang, H. Frequency-constrained unit commitment considering typhoon-induced wind farm cutoff and grid islanding events. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1760–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbig, A.; Borsche, T.S.; Andersson, G. Impact of low rotational inertia on power system stability and operation. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 7290–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Geng, H.; Rajashekara, K.; Chandra, A. Analysis and control of frequency stability in low-inertia power systems: A review. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 2024, 11, 2363–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Pre-disaster and mid-disaster resilience improvement strategy of high proportion renewable energy system considering frequency stability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 151, 109135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.I.; Cook, N.J. The parent wind speed distribution: Why Weibull? J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 131, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.H.; Keyhani, A.; Sefeedpari, P. Wind speed and power density analysis based on Weibull and Rayleigh distributions (a case study: Firouzkooh county of Iran). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, L.A.; Monteiro, C.; Ramirez-Rosado, I.J. Short-term probabilistic forecasting models using Beta distributions for photovoltaic plants. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D. Gaussian mixture models. In Encyclopedia of Biometrics, 2nd ed.; Li, S.Z., Jain, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C. A tutorial on kernel density estimation and recent advances. Biostat. Epidemiol. 2017, 1, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Nanda, P.K. Adaptive feature fusion and spatio-temporal background modeling in KDE framework for object detection and shadow removal. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Tang, Y. Clustered Hybrid Wind Power Prediction Model Based on ARMA, PSO-SVM, and Clustering Methods. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 17071–17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthymiou, G.; Kurowicka, D. Using copulas for modeling stochastic dependence in power system uncertainty analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2008, 24, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. Research of wind power correlation with three different data types based on mixed copula. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 77986–77995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z.; Hu, W.; Huang, Q. Improved probabilistic load flow method based on D-vine copulas and Latin hypercube sampling in distribution network with multiple wind generators. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zamani, M.; Hesamzadeh, M.R.; Zhang, H.T. Data-driven probabilistic optimal power flow with nonparametric Bayesian modeling and inference. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 11, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Xu, F.; Wang, F.; Mi, Z. Spatio-temporal graph neural network and pattern prediction based ultra-short-term power forecasting of wind farm cluster. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 60, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constante-Flores, G.E.; Illindala, M.S. Data-driven probabilistic power flow analysis for a distribution system with renewable energy sources using Monte Carlo simulation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 55, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Huang, S.; Geng, L.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Che, X. Data Driven Analytics for Distribution Network Power Supply Reliability Assessment Method Considering Frequency Regulating Scenario. Electronics 2025, 14, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, L.A.; Franco, J.F.; Cordero, L.G. A fast-specialized point estimate method for the probabilistic optimal power flow in distribution systems with renewable distributed generation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 131, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usaola, J. Probabilistic load flow with correlated wind power injections. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2010, 80, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Bie, Z.; Pan, C.; Liu, S. Fast cumulant method for probabilistic power flow considering the nonlinear relationship of wind power generation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 2537–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Y.; Lin, G. An analytic approach to probabilistic load flow incorporating correlation between non-gaussian random variables. Elektron. Ir Elektrotechnika 2018, 24, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, P. Probabilistic analysis for optimal power flow under uncertainty. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2010, 4, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Sun, K.; Yao, R. Simulation of cascading outages using a power-flow model considering frequency. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 37784–37795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Almasabi, S.; Bera, A.; Mitra, J. Optimal power flow incorporating frequency security constraint. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 6508–6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, B. Security risk assessment using fast probabilistic power flow considering static power-frequency characteristics of power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 60, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Cao, Q.; Shen, C.; Hug, G. Frequency-control-aware probabilistic load flow: An analytical method. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 5170–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Abedi, S.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, X.; Lin, G. Stochastic security assessment for power systems with high renewable energy penetration considering frequency regulation. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 6450–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, W.; Lan, Y.; Shuai, H.; Wei, S.; Gan, W.; Cheng, S. Data-Knowledge Fusion Driven Frequency Security Assessment: A Robust Framework for Renewable-Dominated Power Grids. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, H.R.; Orjuela-Cañón, A.D.; Ganger, D.; Persson, M.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F.; Sood, V.K.; Martinez, W. Nadir frequency estimation in low-inertia power systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 29th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Delft, The Netherlands, 17–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, X.; Gao, N.; Yuan, H.; Hoke, A.; Wu, H.; Tan, J. Frequency nadir constrained unit commitment for high renewable penetration island power systems. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2024, 11, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P.J.; Bell, M.M.; Bowen, S.G.; Gibney, E.J.; Knapp, K.R.; Schreck, C.J. Surface pressure a more skillful predictor of normalized hurricane damage than maximum sustained wind. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101, E830–E846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Classification of Tropical Cyclones. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/informtc/class.htm (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, I.S. On bandwidth variation in kernel estimates—A square root law. Ann. Stat. 1982, 10, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epanechnikov, V.A. Non-parametric estimation of a multivariate probability density. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 1969, 14, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ju, P.; Feuchtwang, J. Probabilistic load flow computation of a power system containing wind farms using the method of combined cumulants and Gram–Charlier expansion. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2011, 5, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athay, T.; Podmore, R.; Virmani, S. A practical method for the direct analysis of transient stability. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 2007, 2, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, P.; Tarr, H.C.; Dykes, K.; Merz, K.; Sethuraman, L.; Verelst, D.; Zahle, F. IEA Wind Task 37 on Systems Engineering in Wind Energy–WP2.1 Reference Wind Turbines; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/73492.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Kundur, P. Power System Stability and Control; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 422–431+581–600. [Google Scholar]

- Michiels, F.; De Schepper, A. A new graphical tool for copula selection. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2013, 22, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.; Ramchandani, H.; Sackett, S.A. Dynamic load flow technique for power system simulators. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2007, 1, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).