Abstract

The integration of molten salt thermal energy storage (TES) into coal-fired power units offers a viable strategy to improve operational flexibility. However, existing studies have predominantly employed steady-state models to quantify the extension of the unit’s load range, while failing to adequately capture dynamic performance. To address this gap, this study utilizes a validated dynamic model of a molten salt TES-integrated power unit to investigate its dynamic characteristics during frequency regulation. The results indicate that molten salt TES exhibits significant asymmetry between its charging and discharging processes in terms of both the speed and magnitude of the power response. Moreover, under load step scenarios, the TES-integrated unit increases its ramp rate from 1.5% to 8.6% PN/min during load decrease, and from 1.5% to 6.3% PN/min during load increase. Under load ramping scenarios, molten salt TES reduces the integral of absolute error (IAE) to 0.15–0.25 MWh, significantly lower than the 3.21–4.59 MWh of the standalone unit. Additionally, in response to actual AGC commands, molten salt TES reduces non-compliant operation time from 729 s to 256 s and decreases the average power deviation by 33.6%. These improvements also increase the ancillary service revenue by 37.7%, from CNY 3364 to CNY 4632 per hour.

1. Introduction

Growing climate concerns and carbon reduction targets are driving a significant transformation in the global energy sector. This energy transition is fundamentally altering the traditional role of coal-fired power plants. Originally designed as stable base-load suppliers, they must now cope with the variability and intermittency of renewable sources such as wind and solar power [1,2]. To accommodate the higher penetration of renewables in the grid, these plants need to demonstrate enhanced operational flexibility, characterized by sustained low-load operation, frequent power adjustments, and faster start-up and shut-down capabilities [3].

While integrating energy storage with coal-fired power plants is considered viable for enhancing flexibility, most large-scale technologies face practical limitations. Pumped hydro storage requires specific geographic conditions [4], compressed air energy storage (CAES) systems remain theoretical concepts rather than proven engineering solutions [5,6], and electrochemical energy storage remains costly while raising safety concerns [7]. In comparison, thermal energy storage (TES) represents a more economically viable solution for improving coal plant flexibility [8]. Among various TES technologies, molten salt TES stands out due to its cost-effectiveness, long service life, broad scalability, and well-matched operating temperature range with coal-fired power units [9].

Among these salts, nitrates, such as Solar Salt and Hitec salt, exhibit lower melting points and reduced corrosivity compared to carbonates and fluorides [10]. These advantages led to their commercial establishment in the 2000s, and they are now broadly adopted in concentrated solar power (CSP) plants [11]. In contrast, high-purity chlorides demonstrate superior high-temperature stability, with their corrosive effects being manageable under inert conditions. Consequently, Hitec salt and Solar Salt are currently the preferred choices in engineering applications. Meanwhile, numerous research efforts have been dedicated to developing enhanced molten salt materials, as evidenced by recent studies [12,13]. A conceptual study in 2017 first introduced molten salt for enhancing the operational flexibility of coal-fired power plants [14], which has since stimulated growing research interest in applying molten salt TES to improve the flexibility of coal-fired units.

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on how molten salt TES enlarges the load ranges of coal-fired power plants. Overall, the integration modes of molten salt TES fall into two categories: steam heating mode and electric heating mode. For steam heating mode, Li et al. [15] reported a reduction in the minimum load from 30% to 19.4% using main steam, while Ma et al. [16] achieved a further decrease in the minimum load of a 1000MW coal-fired power unit to 9% through a three-tank system utilizing both main and reheat steam. Zhang et al. [17] implemented a system where molten salt is heated by superheated steam combined with flue gas, reducing the plant’s minimum power output from 30% to 14.5% of its design load. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [18] increased the output of a 600 MW subcritical plant from 75% to 83.8% of its capacity by using molten salt to replace low-pressure heaters. Electric heating mode, in contrast, offers superior operational flexibility, capable of achieving true zero-power output by redirecting all generated electricity to charge molten salt TES [19]. This configuration, however, incurs higher exergy losses. To address this limitation while harnessing the distinct benefits of both modes, the high flexibility of electric heating and the relatively low exergy loss of steam heating, Miao et al. [20,21] developed innovative hybrid schemes founded on their synergistic integration. Moreover, Refs. [22,23,24] compared various TES integration configurations within power plants, offering important insights into the co-improvement in flexibility and efficiency.

Beyond extending the operational load range, the assistance of molten salt TES in enhancing dynamic performance, particularly in improving ramp rates, has drawn growing interest. Utilizing the internal thermal energy storage of coal-fired units represents an effective approach to enhance their ramp rates. Ref. [25] proposed a modified water–fuel ratio control strategy that accounts for boiler energy storage, increasing the ramp rate of a 660 MW unit from 1.5% to 3.5% PN/min. In addition, condensate throttling [26] and extraction throttling of high-pressure heaters (via feed water bypass) [27] are two typical methods that leverage the thermal storage of the deaerator and high-pressure heaters, respectively, to improve ramp-up performance. However, the internal thermal storage of power units is limited, and its excessive utilization may raise safety concerns. In contrast, molten salt TES, as an external storage solution, offers substantial capacity and minimal impact on unit security, demonstrating significant potential for enhancing dynamic response performance. To achieve this goal, studies such as [28,29] have conducted dynamic modeling of molten salt TES units, while [30,31] have preliminarily quantified the potential of molten salt TES to improve ramp rates. However, limited studies have addressed detailed control strategies for molten salt TES-assisted frequency regulation and its dynamic performance during specific automatic generation control (AGC) scenarios.

To address this gap, this study utilizes a validated system-level dynamic model of a molten salt TES-integrated coal-fired unit to investigate its dynamic characteristics during frequency regulation. The impact of TES charging and discharging operations on the unit’s transient power output is studied. The asymmetry between TES charging and discharging is revealed in terms of both response speed and power capability. Then, the system’s dynamic characteristics under the step and ramp scenarios are simulated. Finally, using actual AGC signals, this study also quantifies the enhancement provided by molten salt TES in the unit’s frequency regulation performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 includes a description of the system, dynamic model, and control strategy of the molten salt TES-integrated coal-fired power unit. Section 3 first investigates the dynamic characteristics of molten salt TES during charging and discharging processes. Then, the system’s dynamic response under two types of frequency regulation instructions, i.e., step and ramp signals, are simulated. Finally, the enhancement in the unit’s frequency regulation performance enabled by molten salt TES is quantified using actual AGC signals. Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions of this study.

2. Methodology

2.1. System Description

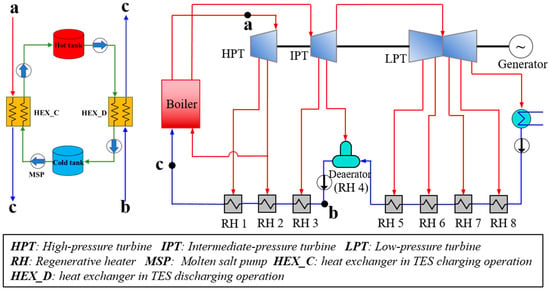

This study investigates the dynamics of a 330 MW subcritical coal-fired power unit integrated with molten salt TES. The coal-fired unit features a drum boiler with a single-reheat section and a regenerative system consisting of three high-pressure (HP) heaters, four low-pressure (LP) heaters, and one deaerator. The system layout is shown in Figure 1, and its key design parameters are listed in Table 1. Molten salt TES with a capacity of 50 MW/100 MWh is integrated into the case power plant.

Figure 1.

System layout of coal-fired power unit.

Table 1.

Key design parameters.

During the molten salt TES charging process, main steam serves as the heat source. After transferring heat, it condenses into water and returns as part of the feedwater to the boiler. Since a portion of the main steam is diverted to the molten salt TES system instead of expanding in the turbine, the unit’s output power decreases rapidly.

During the molten salt TES discharging process, feedwater from the pump outlet absorbs heat released by the molten salt. The heated water then enters the boiler as part of the feedwater, completing the thermodynamic cycle. As the amount of feedwater entering the HP heaters decreases, the extraction steam for the first to third-stage HP heaters is reduced according to the heaters’ self-adaptive balance characteristics. This increases the steam available for power generation, thereby raising the unit’s output power.

In addition, Hitec salt is used in this study, with the thermophysical parameter taken from Ref. [32].

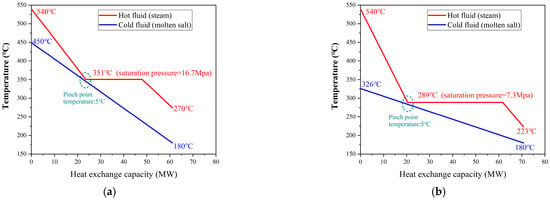

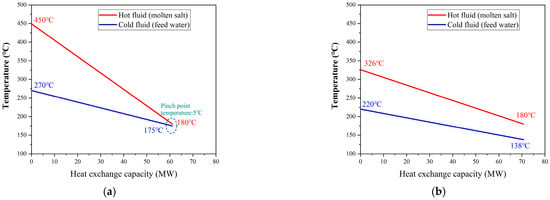

During the regulation process of molten salt TES, not only will the temperatures of the coal-fired power plant system change, but so will the hot and cold storage tanks of molten salt TES. Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the T-Q diagrams characterizing the heat exchange between TES and the working fluid of the coal-fired unit during the charging and discharging phases, respectively. To provide a clearer representation of the molten salt’s temperature span, the T-Q diagrams for both the full-load (100% THA) condition and the minimum-load condition (40%THA) are provided here, with a pinch point temperature set at 5 °C.

Figure 2.

T-Q diagram during TES charging process. (a) THA condition. (b) 40% THA condition.

Figure 3.

T-Q diagram during TES discharging process. (a) THA condition. (b) 40% THA condition.

As shown in Figure 2, under the 100% THA condition, steam at 540 °C and 16.7 MPa can heat the molten salt from 180 °C to 450 °C. Under the 40% THA condition, however, the main steam pressure drops to 7.3 MPa, resulting in a lower saturation temperature and thus limiting the heating capacity. Consequently, the molten salt can only be heated from 180 °C to 326 °C. Therefore, when the unit operates under off-design conditions, the maximum heating temperature of the molten salt varies between 326 °C and 450 °C. In addition, the heat transfer rate also varies between 61 MW and 71 MW. Figure 3 illustrates the discharging phase where molten salt cools from 450–326 °C (determined by the unit load at charging) down to 180 °C, while simultaneously heating the boiler feedwater to a suitable temperature for boiler entry.

2.2. Dynamic Model Development

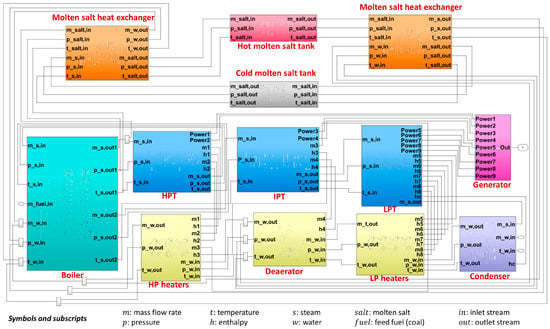

This study is based on a dynamic model previously developed by our research team using MATLAB R2020a Simulink. Due to space limitations, only the main formulas for dynamic modeling are listed in Table 2; more information, including the modeling details of each component, parameter specification, and model validation can be found in our previous work [32]. In addition, the dynamic model has been validated by comparing the simulation results of the main system parameters with experimentally measured data. The results indicate that all the mean absolute percentage errors (MAPEs) are less than 4%, thereby demonstrating the accuracy of the model. The details are also available in Ref. [32].

Table 2.

Main formulas for dynamic modeling.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the power plant subsystems and molten salt TES unit were individually modeled in accordance with the laws of mass conservation and energy conservation, and subsequently integrated into a complete system. For the power plant, dynamic models were incorporated for key components, including the combustion furnace, economizer, steam drum, water wall, reheaters, superheaters, turbines, HP and LP heaters, condenser, and deaerator. For molten salt TES, the primary focus was placed on the dynamic characteristics of heat exchangers and storage tanks.

Figure 4.

Dynamic model developed in MATLAB Simulink.

The meanings of the subscripts are as follows: and denote the hot fluid and cold fluid; and denote the inlet and outlet stream; is the metal; is the heat from the hot fluid to the metal; is the heat from the metal to the cold fluid; is the economizer; is the water wall; is the down pipe; is the steam; is the superheater; is the flue gas; is the water; is the turbine; is the No. i stage group; is the design condition; is the maintained steam flow rate through the No. i stage group; is the molten salt. The superscripts of and denote the liquid phase and gas phase.

Moreover, is the environment temperature, which is taken as 20 °C; and is the melting temperature of the molten salt, which is taken as 142 °C for Hitec salt; represents the heat transfer area, m2; is the heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2·K).

More details are provided in Refs. [2,32].

2.3. Control Strategy

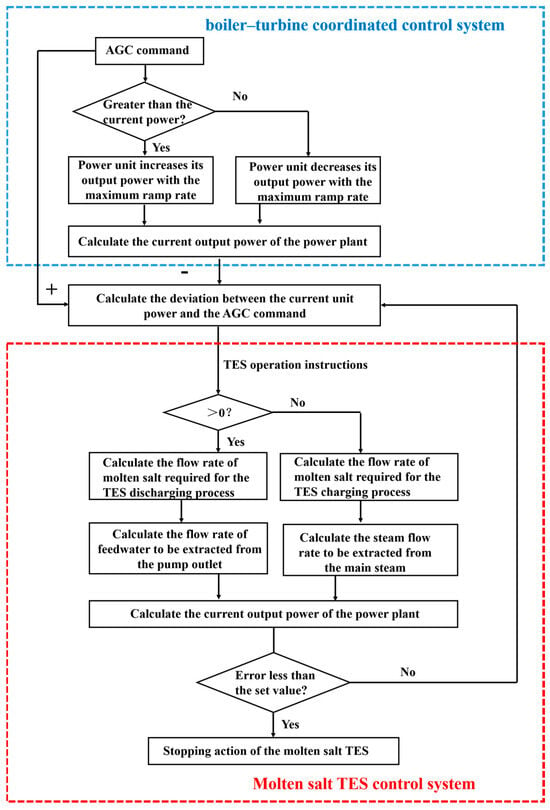

Figure 5 illustrates the load-following control strategy implemented in the molten salt TES-integrated power unit, which integrates a boiler–turbine coordinated control system [33] and a molten salt TES control system.

Figure 5.

Control strategy of molten salt TES-integrated power unit.

Upon receiving an AGC command, the boiler–turbine coordinated control system first adjusts the unit power at the maximum ramp rate. Subsequently, the current output power of the power plant is calculated, and the power deviation between this current power and the AGC command is determined, which is then fed into the molten salt TES control system as input to generate TES operation instructions.

Based on these instructions, the molten salt TES control system differentiates between load increase and load decrease scenarios. For a load increase requirement (when the current power falls short of the AGC command), it calculates the molten salt flow rate needed for discharging, along with the flow rate of feedwater to be extracted from the pump outlet. In contrast, for a load decrease requirement (when the current power surpasses the AGC command), it determines the molten salt flow rate for charging and the steam flow rate to be extracted from the main steam. After dynamically adjusting these parameters, it recalculates the current output power of the power plant and checks whether it meets the set value. If the set value is achieved, the stopping action of molten salt TES is executed; otherwise, the aforementioned process is repeated to achieve accurate power tracking.

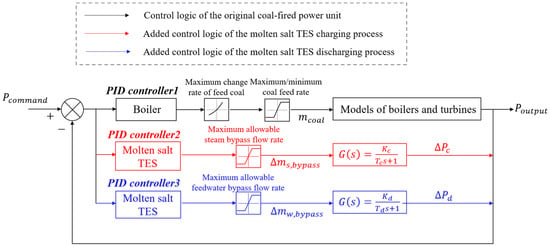

The above control process is achieved via Proportion–Integration–Differentiation (PID) controllers, as shown in Figure 6. PID controller 1 regulates the boiler’s coal feed rate so that it follows AGC commands while adhering to two operational safety constraints: the maximum/minimum coal feed rate that limits the unit’s safe operating load range, and the maximum rate of change in the coal feed that ensures the unit’s ramp rate remains within a safe margin. PID controller 2 compensates for power deviation during the molten salt TES charging process, operating within the limit of the maximum allowable steam bypass flow rate. Similarly, PID controller 3 compensates for power deviation during the molten salt TES discharging process, constrained by the maximum allowable feedwater bypass flow rate.

Figure 6.

Control process and PID controller implementation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dynamic Characteristics of Molten Salt TES Operation

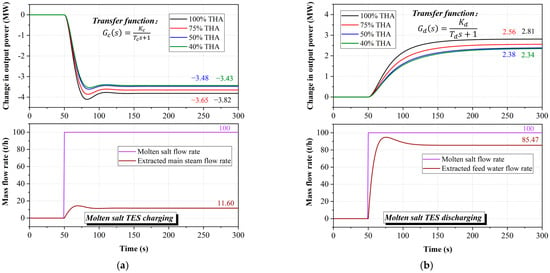

When molten salt TES assists in load regulation of coal-fired units, the molten salt flow rate changes frequently. Therefore, this section studies the dynamic response characteristics of the unit’s power when the molten salt flow is disturbed. The load decrease and load increase processes of the coal-fired unit correspond to the charging and discharging processes of molten salt TES, respectively. The power response characteristics under 100% turbine heat acceptance (THA), 75% THA, 50% THA, and 40% THA conditions are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Power response characteristics during molten salt TES operation. (a) Molten salt TES charging process. (b) Molten salt TES discharging process.

As shown in Figure 7a, during the molten salt TES charging process, the molten salt flow rate steps from 0 to 100 t/h at the 50th second. Subsequently, the main steam flow extracted to heat the molten salt stabilizes at approximately 11.60 t/h by around the 100th second. Following this change, the unit’s power drops rapidly, with the power deviation stabilizing around the 125th second. Furthermore, the power variation induced by the same molten salt flow rate increases with a higher unit load. Under the 100% THA condition, the introduction of 100 t/h molten salt flow reduces the power output by 3.82 MW, while under the 40% THA condition, the power reduction is 3.43 MW. This difference arises because main steam at higher loads possesses greater work capacity than at lower loads, leading to more pronounced effects on power output during TES operation.

As shown in Figure 7b, during the molten salt TES discharging process, the molten salt flow rate steps from 0 to 100 t/h at the 50th second. The extracted feedwater flow subsequently stabilizes at approximately 85.47 t/h by around the 150th second. Following this change, the unit’s power increases rapidly and stabilizes around the 250th second. Similarly to the TES charging process, the power variation induced by the same molten salt flow rate increases with a higher unit load. The power increases resulting from the 100 t/h molten salt flow are 2.81 MW under the 100% THA condition and 2.34 MW under the 40% THA condition, respectively.

To further quantitatively characterize the dynamic influence of molten salt TES on the unit’s power output, a transfer function model is introduced to describe these dynamic characteristics. As reported in reference [34,35,36], when the steam flow through the turbine changes, the resulting response curve of the generated power closely resembles the step response of a first-order inertial element, which can be represented by the following transfer function:

where is the change in unit power output, MW; is the working fluid flow rate for heat exchange with molten salt, t/h; is the open-loop gain, reflecting the static correspondence between input and output; is the time constant, indicating the speed of dynamic response.

The open-loop gain and the time constant values for the molten salt TES charging and discharging processes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

and for molten salt TES charging and discharging processes *.

The results reveal an asymmetry between the charging and discharging phases of molten salt TES. Compared to the charging phase, the open-loop gain during discharging is significantly smaller, indicating that a greater mass flow rate of working fluid is required to achieve the same power variation. Quantitatively, the open-loop gain ranges from −0.329 to −0.296 during charging, but only from 0.033 to 0.027 during discharging across different conditions. This difference arises because the working fluid during charging is main steam, which undergoes phase change from vapor to liquid, releasing substantial latent heat from vaporization. In contrast, during discharging, the working fluid is boiler feedwater, which only experiences sensible heat transfers through temperature rise. The limited temperature increase necessitates a higher flow rate to compensate for the difference in heat transfer capacity.

Moreover, the discharging process exhibits a significantly larger time constant compared to charging, resulting in a slower power increase response compared to the power decrease during charging. Specifically, the time constant varies between 10.3 s and 12.6 s during charging, while it ranges from 38.8 s to 46.5 s during discharging, indicating that the discharging process is approximately 3–4 times slower than charging. The rapid power reduction during charging is attributed to the immediate diversion of main steam away from the turbine. The turbine’s low thermal inertia allows for a fast response. Conversely, power increase during discharging is achieved indirectly by reducing feedwater flow to the HP heaters, which, due to their self-balancing nature, reduce extraction steam and increase steam flow to the high-pressure turbine. The substantial thermal inertia of the HP heaters introduces a much longer delay in the overall response from the initial flow change to the final power adjustment.

Furthermore, despite the identical molten salt flow rate involved in heat transfer, the magnitude of power decrease during TES charging (3.82 MW) exceeds the power increase during discharging (2.81 MW). This discrepancy stems from the difference in energy quality: during load reduction, high-grade main steam is utilized to heat the molten salt, whereas during load increases, the energy is returned to the system via low-grade boiler feedwater. In summary, the thermal inertia of HP heaters is identified as the primary cause for the asymmetric response rates between TES charging and discharging processes, while the disparity in energy quality between the working fluids entering and exiting the thermal cycle constitutes the key factor responsible for the asymmetric magnitude of the power response.

In practical operation, different working fluid flow rates must be employed during load increase and load decrease phases to compensate for this asymmetry. For instance, because the power output during load reduction is highly sensitive to the bypassed steam flow, a relatively smaller adjustment in steam extraction is required. Conversely, during load increase, the power output is less sensitive to changes in feedwater flow, necessitating a proportionally larger adjustment in feedwater flow rate to achieve the same power variation. Furthermore, the application of advanced control strategies is also beneficial for mitigating this asymmetry.

3.2. Dynamic Characteristics Under Various Load-Following Scenarios

3.2.1. Load Step Scenario

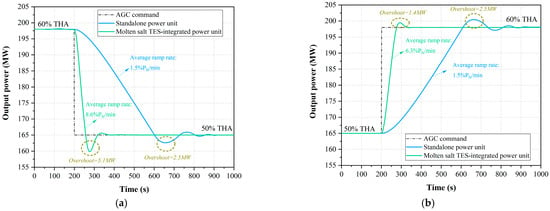

Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of the response to step load changes between the standalone and molten salt TES-integrated power units, with load transitions between 50% and 60% THA.

Figure 8.

Power response of step command. (a) Load decrease process. (b) Load increase process.

As illustrated in Figure 8a, the incorporation of molten salt TES enhances the ramp rate from 1.5% PN/min to 8.6% PN/min during the load decrease process. However, the inherent thermal inertia of TES and the high sensitivity of the power output to steam extraction result in an increased overshoot from 2.5 MW to 5.1 MW during this process. These findings demonstrate that while molten salt TES notably amplifies the load decrease speed, the accompanying overshoot requires careful consideration, suggesting the need for optimizing the control strategies to mitigate this effect. Specifically, the feedforward–feedback strategy could be employed to compensate for the thermal inertia-induced delay by pre-calculating the required adjustment in steam extraction rate or in valve opening of the molten salt system. Additionally, advanced control methods such as model predictive control (MPC) [37], adaptive control [38], and robust control [39] are also expected to be effective.

As shown in Figure 8b, the ramp rate during the load increase process is improved from 1.5% PN/min to 6.3% PN/min. Although the improvement in ramp rate is smaller than that during the load decrease process, the overshoot is significantly reduced, decreasing from 2.5 MW to 1.4 MW. This distinction can be attributed to the indirect nature of power adjustment through feedwater flow modification, which provides the system with adequate time to accommodate the thermal inertia associated with the operation of molten salt TES.

Furthermore, the unit’s dynamic responses to different load step magnitudes are also simulated. Key results, including the average ramp rate and overshoot, are summarized in Table 4. The results indicate that when responding to load decrease step commands with magnitudes of −5%PN to −15%PN, the average ramp rate remains consistently high, exceeding 8%PN/min. Meanwhile, the overshoot shows a slight increase with larger step magnitudes. In contrast, during load increase scenarios, the average ramp rate decreases when the step magnitude reaches +15%PN. This reduction occurs due to the system reaching the maximum allowable feedwater bypass flow rate (see Figure 6), which prevents further power increase by extracting additional heat from molten salt TES through the feedwater bypass.

Table 4.

Dynamic response results under different load step magnitudes.

3.2.2. Load Ramping Scenario

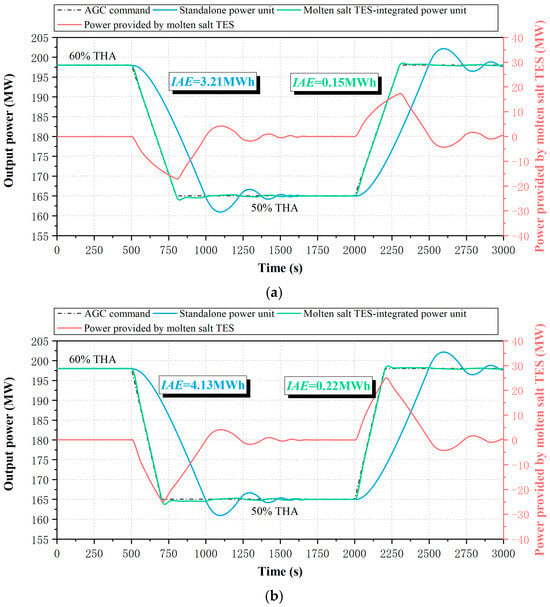

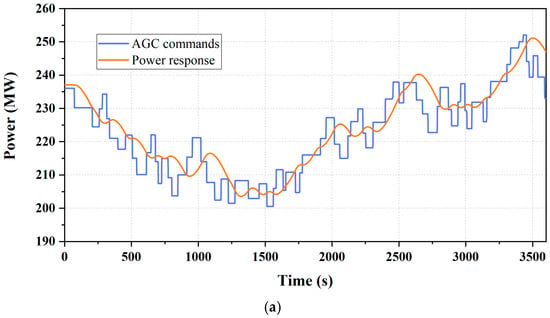

The power unit’s response to load ramping commands with different target ramp rates is shown in Figure 9. The unit is subjected to load variations between 50% and 60% THA, with ramp rates varying from 2% PN/min to 4% PN/min. To quantify the performance in tracking ramp commands, the integral of absolute error (IAE) is adopted as an evaluation metric, defined as follows [40]:

where and are the actual output power and the power command, MW, respectively.

Figure 9.

Power response of ramping command. (a) Target ramp rate: 2%PN/min. (b) Target ramp rate: 3%PN/min. (c) Target ramp rate: 4%PN/min.

It is observed that the IAE of the standalone unit increases from 3.21 MWh to 4.59 MWh as the ramp rate rises from 2% PN/min to 4% PN/min. In contrast, the IAE of the molten salt TES-integrated power unit remains consistently low, between 0.15 MWh and 0.25 MWh, confirming the effectiveness of TES in enhancing the ramping capability of coal-fired units. The light-red curve further illustrates the real-time power contribution from molten salt TES. Analysis shows that steeper ramp commands demand more rapid and substantial power variations from TES, necessitating greater molten salt utilization for effective load-following operation. These findings provide guidance for the design of molten salt TES, particularly regarding capacity selection of heat exchangers and pumps.

3.3. Dynamic Performance in Responding to Actual AGC Commands

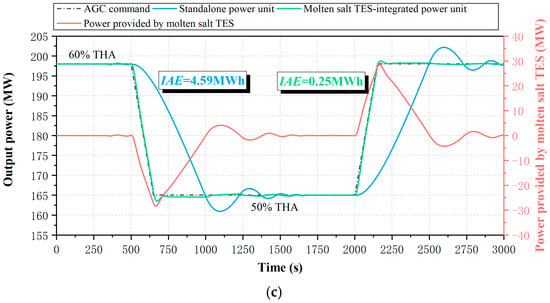

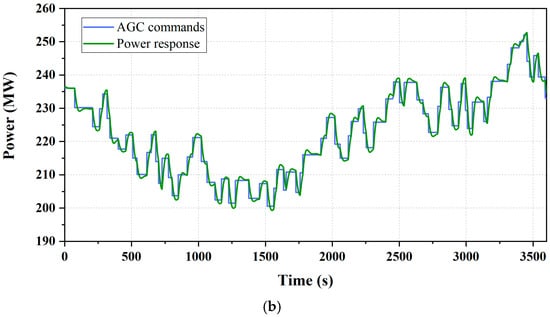

This section further quantifies the dynamic performance of the molten salt TES-integrated power unit in responding to actual AGC commands, as shown in Figure 10. Figure 10a reveals limitations in the standalone power unit’s dynamic performance, including inadequate ramp rates, recurrent overshoot, reverse regulation during AGC tracking. In contrast, with molten salt TES integration, Figure 10b shows notable enhancements in response quality, where these undesirable phenomena are substantially suppressed.

Figure 10.

Power response to actual AGC commands. (a) Standalone power unit. (b) Molten salt TES-integrated power unit.

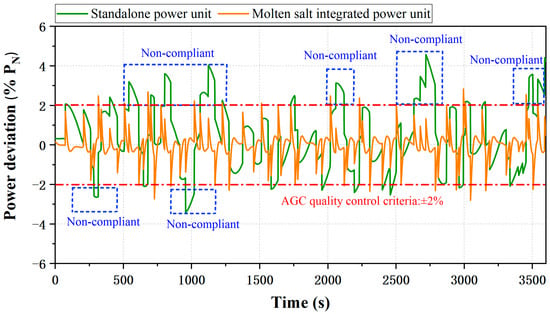

China’s AGC market regulations stipulate that power deviation should not exceed ±2% of the unit’s design load [41]. As depicted in Figure 11, compared to the standalone power unit, the TES-integrated system maintains power deviation within this threshold during AGC operation, demonstrating the practical value of TES in meeting grid code requirements.

Figure 11.

Power deviation in response to actual AGC commands.

The results indicate a significant reduction in the number of non-compliant responses. During the one-hour response period, the cumulative duration of non-compliant operation decreases substantially from 729 s to 256 s. Moreover, the average power deviation decreases from 1.25%PN to 0.83%PN, corresponding to a 33.6% improvement.

Building upon the improved tracking performance, the integration of molten salt TES also enhances economic returns in the AGC ancillary service market. During the response to AGC signals, the associated profit is calculated as follows [42]:

where is the regulation magnitude of the unit’s power, MW; and denotes the compensatory price of the AGC ancillary service, taken as 5 CNY/MW [42].

According to the calculation method shown in Ref. [32], the comprehensive performance indicator () in response to AGC commands is improved from 1.71 to 3.05. Then, it can be calculated that economic returns obtained from responding to the above one-hour AGC ancillary service increases from CNY 3364 to CNY 4632, representing a 37.7% improvement. This demonstrates that the benefits of molten salt TES extend beyond ramp rate and power deviation to include tangible economic gains in market operations.

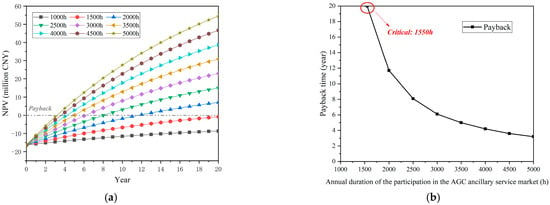

Furthermore, the economic performance of molten salt TES over its lifespan has been evaluated, with Net present value (NPV) selected as the key metric, as shown in Equation (25). In this study, the inlet cash flow is estimated based on the AGC ancillary service earnings described previously. The outlet cash flow account for both the capital investment and the annual operational expenses. The calculation method for the capital cost is detailed in Ref. [30], and the annual operational cost is assumed to be a fixed 4% of the capital investment. The NPV and payback period have been calculated for various annual participation durations in the AGC ancillary service market, as illustrated in Figure 12.

where and are the inlet and outlet cash flow; is the service life, which is assumed to be 20 years [43]; and denotes the discount rate, which is assumed to be 5% [43].

Figure 12.

NPV and payback time. (a) NPV under various annual participation durations in AGC ancillary service market. (b) Payback time under various annual participation durations in AGC ancillary service market.

As shown in Figure 12a, as the annual participation duration in the AGC ancillary service market increases from 1000 h to 5000 h, the NPV rises from CNY −8.7 million to CNY 54.5 million. Furthermore, Figure 12b indicates that the revenue over TES’s lifespan can cover the investment and operational costs (i.e., NPV > 0) only when the annual participation duration exceeds 1550 h. Additionally, the payback time decreases nonlinearly with longer participation durations. The rate of decrease is initially rapid and then slows; when the duration reaches 5000 h, the payback time is only 3.2 years, demonstrating the potential of molten salt TES in the ancillary service market.

3.4. Dynamic Performance in Ultra-Low Load Scenarios

Previous sections of this paper have investigated the system’s dynamics within the normal load range (50%PN~60%PN). However, real-world power plants sometimes operate under boundary conditions, such as ultra-low load operation (below 30%PN). Therefore, this section further investigates the dynamics under the ultra-low load interval from 30%PN to 20%PN as an extension to the main findings.

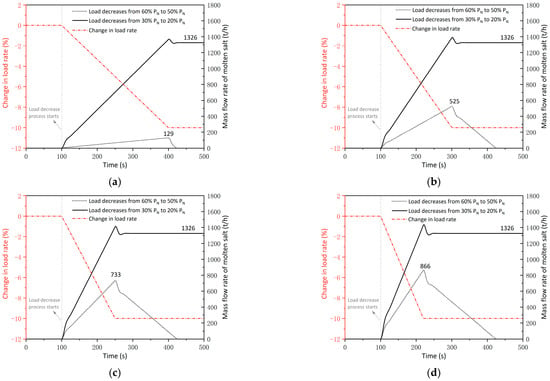

Two load decrease processes with equal magnitude were simulated for the integrated system: (1) from 60%PN to 50%PN, and (2) from 30%PN to 20%PN. As shown in Figure 13, the real-time required mass flow rate of molten salt was compared during these processes, revealing distinctive system dynamics under ultra-low load conditions.

Figure 13.

Dynamic comparison of normal load interval (from 60%PN to 50%PN) and ultra-low load interval (from 30%PN to 20%PN). (a) Target ramp rate: 2%PN/min. (b) Target ramp rate: 3%PN/min (c) Target ramp rate: 4%PN/min. (d) Target ramp rate: 5%PN/min.

The results indicate that a greater mass flow rate of molten salt is required for load reduction from 30%PN to 20%PN, compared to the case from 60%PN to 50%PN. This is because the standalone power plant can only reduce its load rate to 30% due to the boiler’s stable combustion constraints. Consequently, all additional load reduction flexibility of the integrated system between 30%PN and 20%PN must be exclusively provided by molten salt TES. This indicates that achieving the system’s ultra-low load operation (i.e., below 30% load rate) requires molten salt TES with larger-capacity heat exchangers and molten salt pumps.

Another crucial difference lies in the action of molten salt TES after the system load reduces to its target value. After the system load decreases from 60%PN to 50%PN, the mass flow rate of molten salt gradually declines to zero as the load rate of the standalone power plant progressively decreases to 50%. In contrast, when the system load drops from 30%PN to 20%PN, the mass flow rate of molten salt TES increases to a constant value (1326 t/h) for sustained operation. This reveals that to maintain ultra-low load operation (i.e., below 30% PN), continuous charging of molten salt TES is necessary, which imposes higher capacity requirements on molten salt storage tanks.

4. Conclusions

This study employed a validated dynamic model of a molten salt TES-integrated power unit to examine its dynamic characteristics during frequency regulation. The major conclusions are listed below.

(a) The integration of molten salt TES introduces significant asymmetry in both the speed and magnitude of power response between charging and discharging processes. Quantitatively, the time constant of discharging (38.8–46.5 s) is approximately 3–4 times larger than that of charging (10.3–12.6 s), while the open-loop gain of discharging (0.027–0.033) is only about one-tenth of the charging gain (0.296–0.329) in absolute terms.

(b) Simulations under both load step and load ramping scenarios demonstrate that molten salt TES significantly enhances the load-following capability of coal-fired units. In the load step scenario, TES integration increases the ramp rate from 1.5% to 8.6% PN/min during load reduction, and from 1.5% to 6.3% PN/min during load increase. Under ramp commands, the TES-integrated system maintains an IAE within 0.15–0.25 MWh, markedly lower than the 3.21–4.59 MWh of the standalone power unit.

(c) The molten salt TES-integrated power unit demonstrates superior regulation performance in AGC response compared to the standalone unit. The revenue within an hour is increased by 37.7%, from CNY 3364 to CNY 4632. As the annual participation duration in the AGC ancillary service market increases up to 5000 h, the payback time of molten salt TES is only 3.2 years.

(d) Compared to operation within the normal load range, the system dynamics under ultra-low load conditions (below 30%PN) exhibit two distinct characteristics. First, a greater mass flow rate of molten salt is required below 30%PN. Second, to maintain ultra-low load operation (i.e., below 30% PN), continuous charging of molten salt TES is necessary, which imposes higher capacity requirements on molten salt storage tanks.

This work advances the understanding of the dynamic response characteristics of molten salt TES-integrated power units during frequency regulation. Future work should systematically compare the dynamic performance of different TES integration configurations to establish comprehensive design guidelines. Moreover, advanced control methods will be introduced in the future to eliminate the overshoot during load reduction.

Author Contributions

L.L.: Writing—original draft. J.Y.: Writing—review and editing. W.S.: Writing—review and editing. L.W.: Resources, validation. J.L.: Writing—review and editing. C.M.: Software. C.W.: Methodology, conceptualization, review and editing, supervision. X.R.: Funding acquisition, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is financially supported by the Key Science and Technology Projects of Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute CORP., LTD: 37-K2024-025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Lin Li, Junbo Yang, Wei Su were employed by the company Shandong Electric Power Engineering Consulting Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, R.; Sun, F.; Wei, W. Co-enhancement of flexibility and efficiency for combined heat and power units via a novel steam ejector and networked thermal recovery system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2026, 348, 120684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Xu, P.; Cao, H.; Wang, W.; Sun, Q. Dynamic simulation of a subcritical coal-fired power plant with the emphasis on flexibility. Appl. Energy 2025, 392, 125976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, C.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Yan, J. Improve the flexibility provided by combined heat and power plants (CHPs)—A review of potential technologies. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Q.; Tian, Y.; Qian, X.; Li, X. Retrofitting coal-fired power plants for grid energy storage by coupling with thermal energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 119048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Feng, Z.; Fan, Y.; Yao, Z.; Cui, S. Enhancing flexibility of coal-fired power plants via compressed air energy storage integration: A 4E (Energy, Exergy, Economic, Environmental) and operational performance analysis. Energy 2025, 332, 137124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the peak shaving performance of coupled system of compressed air energy storage and coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, B.; Sun, Q.; Wennersten, R. Application of energy storage in integrated energy systems—A solution to fluctuation and uncertainty of renewable energy. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Oeljeklaus, G.; Görner, K. Improving the load flexibility of coal-fired power plants by the integration of a thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Li, Z.; Lv, K.; Chang, D.; Hu, W.; Zou, Y. Design and performance analysis of deep peak shaving scheme for thermal power units based on high-temperature molten salt heat storage system. Energy 2024, 288, 129557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Bauer, T. Progress in Research and Development of Molten Chloride Salt Technology for Next Generation Concentrated Solar Power Plants. Engineering 2021, 7, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.; Sarvghad, M.; Bell, S. Review on the challenges of salt phase change materials for energy storage in concentrated solar power facilities. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 238, 122034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sang, L.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y. Molecular dynamics simulation of the effects of nitrite/nitrate equilibrium on the structure and properties of KNO2-KNO3-K2CO3 molten salt systems. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Shi, H.; Chai, Y.; Yu, R.; Weisenburger, A.; Wang, D.; Bonk, A.; Bauer, T.; Ding, W. Molten chloride salt technology for next-generation CSP plants: Compatibility of Fe-based alloys with purified molten MgCl2-KCl-NaCl salt at 700 °C. Appl. Energy 2022, 324, 119708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbrecht, O.; Bieber, M.; Kneer, R. Increasing fossil power plant flexibility by integrating molten-salt thermal storage. Energy 2017, 118, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cao, Y.; He, T.; Si, F. Thermodynamic analysis and operation strategy optimization of coupled molten salt energy storage system for coal-fired power plant. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Si, F. Multi-objective optimization design of hybrid molten salt-phase change salt thermal energy storage system: An enhanced peak shaving scheme of ultra-supercritical coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2025, 127, 117145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, H.; Yan, J. Design and performance evaluation of a new thermal energy storage system integrated within a coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y. Peak shaving performance analysis of a coal-fired power plant integrated with molten salt thermal energy storage system based on energy-potential matching principle. J. Energy Storage 2025, 124, 116956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Ma, S.; Zhao, G.; Gu, Y. Comparative investigation on the thermodynamic performance of coal-fired power plant integrating with the molten salt thermal storage system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, K.; Yan, J. Design and performance evaluation of thermal energy storage system with hybrid heat sources integrated within a coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2024, 82, 110611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, J. Energy, exergy, and economic analyses on coal-fired power plants integrated with the power-to-heat thermal energy storage system. Energy 2023, 284, 129236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Miao, L.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J. Design and thermo-economic analysis on molten salt thermal energy storage system integrated within coal-fired power plant: Co-storing energy from live and reheat steam. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 117637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, H.; Ren, S.; Si, F. Effects of integration mode of the molten salt heat storage system and its hot storage temperature on the flexibility of a subcritical coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, D.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, K.; Yan, J. Design and performance comparison of stepwise and staged molten salt thermal storage systems integrated within a coal-fired power plant. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 117574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, J. Flexibility and efficiency co-enhancement of thermal power plant by control strategy improvement considering time varying and detailed boiler heat storage characteristics. Energy 2021, 232, 121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zeng, D.; Niu, Y.; Cui, C. Modeling for condensate throttling and its application on the flexible load control of power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 95, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Chong, D.; Yan, J. Improving operational flexibility by regulating extraction steam of high-pressure heaters on a 660 MW supercritical coal-fired power plant: A dynamic simulation. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, M.; Liu, J. Dynamic modeling and performance analysis of a coal-fired power plant integrated with flue gas-molten salt thermal energy storage system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Liu, J. Dynamic characteristics and real-time control of flue gas-molten salt heat exchanger for flexibility transformation of coal-fired power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Dong, J.; Chen, H.; Feng, F.; Xu, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, T. Dynamic characteristics and economic analysis of a coal-fired power plant integrated with molten salt thermal energy storage for improving peaking capacity. Energy 2024, 290, 130132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, F. Dynamic performance of a power plant integrating with molten salt thermal energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 262, 125223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Gao, L.; Tian, S.; Wang, W.; Sun, Q. The flexibility of a molten salt thermal energy storage (TES)-integrated coal-fired power plant. Appl. Energy 2025, 402, 126876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Yan, J. Dynamic performance and control strategy modification for coal-fired power unit under coal quality variation. Energy 2021, 223, 120077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jing, S.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Niu, Y.; Zeng, D.; Cui, C. Combined heat and power control considering thermal inertia of district heating network for flexible electric power regulation. Energy 2019, 169, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Jing, S. Load-change Control Strategy for Combined Heat and Power Units Adapted to Rapid Frequency Regulation of Power Grid. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2018, 42, 63–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Xiang, P. Modeling condensate throttling to improve the load change performance of cogeneration units. Energy 2020, 192, 116684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatkovikj, M.; Li, H.; Zaccaria, V.; Aslanidou, I. Development of feed-forward model predictive control for applications in biomass bubbling fluidized bed boilers. J. Process Control 2022, 115, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plankenbühler, T.; Müller, D.; Kalr, J. An adaptive and flexible biomass power plant control system based on on-line fuel image analysis. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 40, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yu, X. Robust model predictive control of condensate throttling in an ultra-supercritical plant for frequency supports of power systems with high renewable share. Energy 2025, 332, 136989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cui, C.; Meng, Q.; Shen, Y.; Fang, F. IAE performance based signal complexity measure. Measurement 2015, 75, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard DLT 657-2015; Code for Acceptance Test of Modulating Control System in Fossil Fuel Power Plant. National Energy Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.; Kong, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lao, J.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, L.; Song, J. Improving the Flexibility of Coal-Fired Power Units by Dynamic Cold-End Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Du, X.; Shi, Y.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F. A novel system for reducing power plant electricity consumption and enhancing deep peak-load capability. Energy 2024, 295, 131031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).