Abstract

Oxy-fuel combustion technology is a critical pathway for carbon capture in the cement industry. However, the high-concentration CO2 atmosphere significantly alters multiphysics coupling in the calciner and systematic studies on its comprehensive effects remain limited. To address this, a Computational Particle Fluid Dynamics (CPFD) model using the MP-PIC method was implemented using the commercial software Barracuda Virtual Reactor 22.1.2 to simulate an industrial-scale oxy-fuel cement calciner and validated against industrial data. Under oxy-fuel combustion with 50% oxygen concentration in the tertiary air, simulations showed a 38.4% increase in the solid–gas mass ratio compared to conventional air combustion, resulting in a corresponding 37.7% increase in total pressure drop. Flow resistance was concentrated primarily in the constriction structures. Local temperatures exceeded 1200 °C in high-oxygen regions. The study reveals a competition between the inhibitory effect of high CO2 partial pressure on limestone decomposition and the promoting effect of elevated overall temperature. Although the CO2-rich atmosphere thermodynamically suppresses calcination, the higher operating temperature under oxy-fuel combustion effectively compensates, achieving a raw meal decomposition rate of 92.7%, which meets kiln feed requirements. This research elucidates the complex coupling mechanisms among flow, temperature, and reactions in a full-scale oxy-fuel calciner, providing valuable insights for technology design and optimization.

1. Introduction

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) technology is considered essential for global climate change mitigation [1,2]. The decarbonization of cement manufacturing is distinctive. Unlike sectors like the power plant and steel industry, about 60% of its CO2 emissions are process emissions from limestone calcination, with the subsequent 35% stemming from fossil fuel combustion in the calciner and rotary kiln [3,4]. The European Cement Association’s 2050 Carbon Neutrality Roadmap sets a target of 227 kg CO2 per ton of clinker [4]. CCUS, alongside other innovative technologies, is expected to deliver roughly 48% of the necessary abatement [5].

Carbon capture technologies in the cement industry are generally divided into two pathways: in-process capture during combustion and post-combustion capture. The in-process route, which includes oxy-fuel combustion [6,7,8], indirect calcination [9], and calcium looping [10,11,12], aims to concentrate CO2 within the core industrial process. The cement industry holds a distinctive advantage for in-process capture, particularly oxy-fuel combustion, due to its flue gas composition. The CO2 concentration from a conventional cement plant is 20–30 vol% [13], a significantly higher baseline compared to the 12–15% [14,15] from coal-fired power plants. This elevated level stems from the inherent process emissions of limestone decomposition. Oxy-fuel combustion leverages this advantage, producing flue gas with over 80% CO2 that significantly facilitates the subsequent purification process [16]. As a result, integrated systems employing oxy-fuel combustion for primary enrichment, followed by energy-efficient cryogenic separation, have been demonstrated to yield lower specific energy consumption than applying post-combustion capture to the dilute flue gas of conventional cement production [17,18].

The cement clinker production process has evolved through several stages, including wet-process kilns, dry-process hollow kilns, shaft kilns, and finally the precalciner kiln, which is the current industry standard. The calciner, a core component of this system, requires that raw meal be calcined to a decomposition rate exceeding 90% before entering the rotary kiln to ensure clinker quality. The emerging oxy-fuel combustion calciner integrates the advantages of external calcination with oxy-fuel technology, offering benefits such as wide fuel adaptability, high combustion efficiency, and reduced flue gas volume. However, the high CO2 concentration inherent to oxy-fuel combustion thermodynamically suppresses the calcination reaction, complicating the achievement of the required decomposition rate.

Current understanding of raw meal decomposition under high CO2 concentrations relies predominantly on laboratory-scale studies. Thermogravimetric analysis is commonly used to determine decomposition kinetics from mass loss curves, but its small sample mass and slow heating rates poorly represent industrial conditions [19,20,21,22]. Tubular furnaces allow for larger samples and faster heating, but the agglomerated state sample configuration fails to mimic the suspension state in a real calciner [23,24,25,26,27]. Gas–solid suspension reactors can achieve a suspended state, but typically operate in batch mode, unlike continuous industrial processes [24,28,29]. Drop-tube reactors feature continuous feeding and co-current gas–solid flow, closely approximating the suspension state; nonetheless, their simplified heat source and flow fields remain significant deviations from industrial reality [30]. The complex coupling of flow, combustion, and reaction under the O2/CO2 atmosphere in the calciner is not yet well understood, posing a major challenge to the development and industrial application of this technology.

CPFD provides an effective approach for simulating gas–solid two-phase dynamics in calciners. This method is particularly valuable under high temperature conditions exceeding 850 °C and complex flow patterns that combine swirling and spouting motions, where direct experimental measurements are difficult to obtain. Its application is especially relevant for oxy-fuel combustion calciners, which have rarely been implemented at an industrial scale and consequently lack operational data. Through numerical simulation, key parameters including particle distribution, temperature profiles, and gas composition can be predicted, offering crucial guidance for system design and operation. While studies specifically focusing on cement oxy-fuel calciners using CPFD remain limited, relevant research has been conducted in the power generation sector. Krzywanski et al. [31,32] developed a one-dimensional Eulerian–Eulerian model for circulating fluidized bed boilers. Zhou et al. [33,34] established a two-dimensional simulation of CFB oxy-fuel combustion that accounted for gas–solid flow characteristics. Wu et al. [35] investigated three-dimensional flow patterns and pollutant emissions in an oxy-fuel furnace with flue gas recirculation. However, these previous studies have not addressed the critical interaction between fuel combustion and raw meal decomposition, which is fundamental to cement production. Therefore, developing a comprehensive model that simultaneously describes gas–solid flow, combustion processes, and calcination kinetics under oxy-fuel conditions represents an important step toward the industrial application of this technology.

This work establishes a three-dimensional computational model for gas–solid two-phase flow in a typical inline calciner based on the Eulerian–Lagrangian framework, using the commercial software Barracuda Virtual Reactor 22.1.2. The Large Eddy Simulation (LES) method was employed to resolve the fluid field, while the Multiphase Particle-in-Cell (MP-PIC) approach was used to simulate particle motion. The model incorporates chemical reactions for fuel combustion and raw meal decomposition, and was validated against hot-state industrial data. An industrial-scale oxy-fuel combustion calciner was simulated using the MP-PIC method to investigate material flow patterns, fuel combustion characteristics, raw meal decomposition behavior, and the CO2 enrichment process in flue gas. To the best of our knowledge, such an application of the MP-PIC approach under oxy-fuel conditions has not been reported in prior literature for industrial-scale calciners. The findings provide valuable insights for the structural design and operational optimization of oxy-fuel combustion systems in the cement industry.

2. Simulation Method

An oxy-fuel combustion calciner functions as a gas–solid reactor, where the gas phase comprises flue gas from the rotary kiln and combustion air, while the solid phase consists of raw meal and fuel particles. Simulating such a system is challenging due to the complex flow field, strongly exothermic combustion, and endothermic calcination reactions. Therefore, an accurate computational model must address three key aspects: the description of gas and particle flow, the modeling of chemical reactions, and the coupling between gas–solid dynamics and reaction processes.

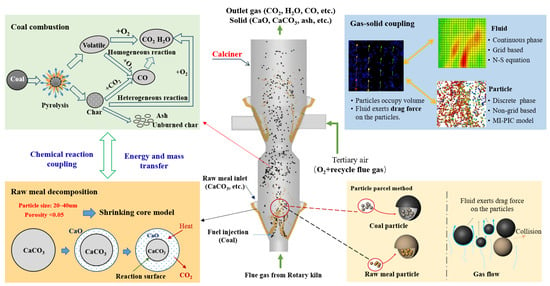

In a typical cement calciner, raw meal particles have an average diameter of 20–40 μm. This fine granulometry, combined with the large scale of industrial production, leads to an extremely high number of particles in the reactor. For instance, in a 4000 t/d production line, the total particle count can reach approximately 500 billion, resulting in a complex and extensive gas–solid system. To overcome this, the Eulerian–Lagrangian approach was adopted in this study. In this framework, the fluid phase is treated as a continuum and solved using the Navier–Stokes equations, while the particle phase is described by the MP-PIC method (Figure 1). Both phases are computed within the same solver. To improve computational efficiency, parcels representing groups of particles with identical properties are used. These computational particles dynamically transition between the Eulerian and Lagrangian representations, with particle stresses calculated on the Eulerian grid to efficiently handle particle–particle interactions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the computational framework based on the MP-PIC method for cement calciner simulation.

2.1. Governing Equations of the Gas Phase

The cement calciner operates as a gas–solid two-phase flow system where the average gas velocity through the calciner cross-section generally ranges from 6 to 12 m/s, with local velocities exceeding 40 m/s in certain regions. Under these conditions, the flow exhibits high Reynolds numbers and strong turbulence that significantly influence phase interactions. This study employs the LES approach for turbulence modeling. The LES methodology applies a spatial filter to the Navier–Stokes equations, directly resolving large-scale turbulent structures while modeling subgrid-scale motions through appropriate closures. This formulation is particularly advantageous for simulating the high-Reynolds-number flows encountered in industrial-scale calciners with complex geometries. Within the MP-PIC framework, the gas-phase governing equations are established in the Eulerian reference frame as presented in Equations (1)–(6) [36,37,38].

The mass conservation equation of the gas phase is:

The momentum equation of the gas phase is:

The species transport equation for the gas composition is solved by:

The gas turbulence is molded by the LES model [39], where

in which = 0.01.

The energy conservation equation of the gas phase is [40]:

2.2. Governing Equations of the Particle Phase

Since the calciner system involves both homogeneous and heterogeneous reaction processes, momentum, energy, mass, and species exchange occur between the gas and particle phases. The governing equation of the particle phase is based on the Lagrangian algorithm, as shown in Equations (7)–(9). The MP-PIC method solves the particle distribution function equation to obtain the spatial distribution of the particle phase. The coupling of gas–solid flow and chemical reactions is achieved by defining source terms in the governing equations for both phases.

The particle acceleration is calculated as [41,42]:

The particle motion equation is:

For the energy equation of a particle, based on the surface reaction model, the reaction only occurs on the surface of the particle, assuming that the temperature inside the particle is uniform. The energy equation of a particle is:

2.3. Governing Equation of Interphase Interaction

The governing equations of interphase interaction are given in Equations (10)–(18) [43,44]. For drag force calculation, the Wen-Yu model is generally applied to dilute phase flows with solid volume fractions below 0.6, while the Ergun model is recommended for dense phase conditions where the solid volume fraction ranges from 0.47 to 0.7. The cement calciner system investigated in this work exhibits clear dilute phase characteristics. Raw meal enters the furnace chamber through a feed pipe under gravitational force, and fuel particles are injected via pneumatic conveying. An upward gas flow from the chamber bottom serves to fluidize and transport the solid particles. The resulting average solid volume fraction remains approximately 0.001, indicating a nearly infinitely diluted state. In this study, although local particle volume fractions exceed 0.1 in certain regions (such as the raw meal inlet and bottom walls), these zones account for less than 1% of the total calciner volume. Based on these conditions, the Wen-Yu model provides an appropriate framework for drag force calculation throughout the system.

The particle volume fraction is calculated as:

The equation of interphase mass source term is:

The interphase force is modeled as:

The equation of interphase heat transfer is:

The interphase drag coefficient is modeled as:

in which is determined by the Wen-Yu model.

When Re < 1000, is calculated as:

When Re ≥ 1000, is calculated as:

2.4. Kinetics of Chemical Reaction

The chemical reactions implemented in this study comprise devolatilization, homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions, and catalytic processes, with corresponding kinetic rate equations summarized in Table 1. Pulverized coal combustion and raw meal decomposition represent the two dominant processes in the calciner. The coal is modeled as a mixture of ash, fixed carbon, and volatiles, undergoing devolatilization and char oxidation. Devolatilization is represented by a single-step first-order reaction yielding CH4, C2H4, and HCN, with volatile composition determined via mass balance, while moisture evaporation is integrated into this step. Char oxidation involves reactions with both O2 and CO2, governed by external diffusion of these gases through the particle boundary layer. For raw meal, the calcination reaction is considered and incorporates inhibition due to CO2 in the gas phase. The decomposition of CaCO3, simulated via the heterogeneous reaction model, proceeds with a standard reaction enthalpy of +178.3 kJ/mol.

Table 1.

Reaction mechanisms implemented in the CPFD simulation [24,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

The present model is specifically developed for pulverized coal-fired calciner with particle sizes in the micrometer range. For applications involving alternative fuels such as refuse-derived fuel (RDF) or biomass with particle sizes in the millimeter range or larger, modifications to the drag model and combustion kinetics would be required.

3. Simulation Conditions

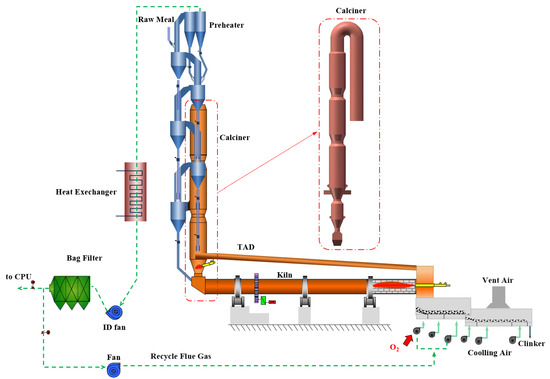

This study models an oxy-fuel combustion calciner integrated into a cement precalciner kiln system, as illustrated in Figure 2. Industrial-grade oxygen exchanges heat with hot clinker on the first grate bed of the cooler, producing high-temperature secondary and tertiary air streams. The secondary air supports combustion in the rotary kiln, while the tertiary air is introduced into the calciner. To regulate oxygen concentrations in these air streams, a flue gas recirculation duct routes exhaust gas from the preheater outlet back to the first grate bed of the cooler. Except for unavoidable air leakage, the entire pyroprocessing system operates without introducing external air. This configuration reduces total flue gas volume and increases CO2 concentration in the exhaust stream.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the oxy-fuel combustion clinker production system.

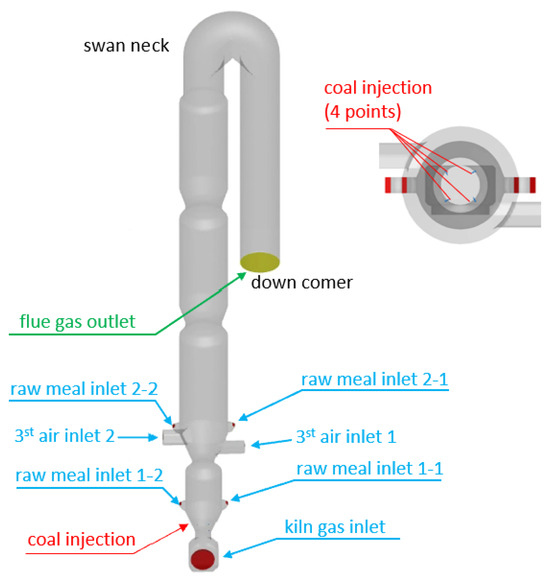

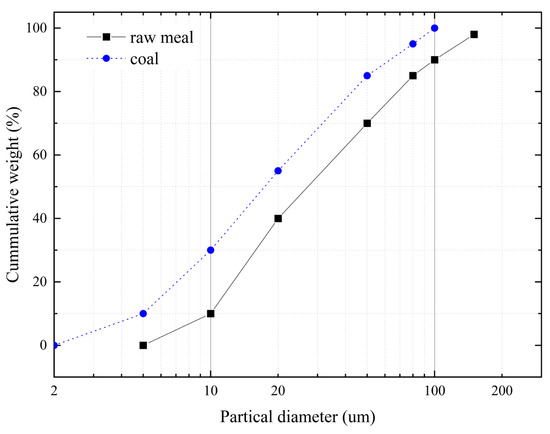

The current study focuses on a calciner with a production capacity of 4000 t/d. As cement kilns typically operate in the range of 1000–10,000 t/d, and given the fundamental similarities in airflow, material feeding, and coal injection across different scales, the conclusions derived from this model are expected to provide valuable references for kilns of varying capacities. The calciner structure comprised several components: bottom throat, lower cone, reducing furnace, main furnace, gooseneck pipe, and downward pipeline. The main furnace featured a diameter of 6.0 m and extended 101 m along the process flow. As illustrated in Figure 3, pulverized coal was injected through four symmetrically arranged feed points in the lower cone region. Raw meal was introduced through two vertically separated layers: an upper layer positioned above the tertiary air duct and a lower layer located above the lower cone, with each layer fed symmetrically through left and right injection points. The chemical composition of the raw meal and the proximate analysis of the coal are provided in Table 2 and Table 3. The particle size distribution of the raw meal and coal was shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the calciner geometry with inlet configurations for gas, coal, and raw meal.

Table 2.

Industrial analysis and ultimate analysis of pulverized coal.

Table 3.

The chemical composition of the raw meal.

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution of raw meal and pulverized coal.

The gas phase enters the calciner through two streams: kiln exhaust gas and tertiary air. To evaluate differences between conventional and oxy-fuel conditions, two representative cases were defined. Case 1 represents air combustion, where the tertiary air consists of ambient air. Case 2 corresponds to oxy-fuel combustion with 50 vol% oxygen concentration in the tertiary air, achieved by blending O2 and recycling CO2 at equal volume ratios. The corresponding gas inlet boundary conditions are summarized in Table 4. While the feed rates of raw meal and pulverized coal were held constant during each simulation, their values differed between cases. Under oxy-fuel conditions, the pulverized coal and raw meal feed rates were set at 5.15 kg/s and 98.0 kg/s, respectively, compared to 3.80 kg/s and 74.5 kg/s in the air combustion case.

Table 4.

Gas inlet boundary conditions.

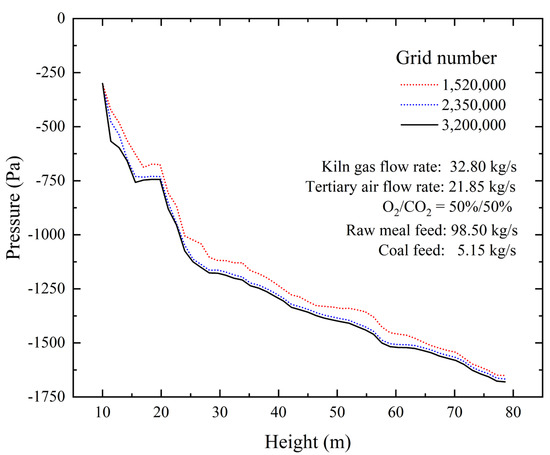

A grid sensitivity analysis was conducted using three mesh configurations containing 1.52 million, 2.35 million, and 3.20 million cells, respectively. As shown in Figure 5, the results obtained with the 2.35 million cell and 3.20 million cell meshes showed strong agreement, whereas the 1.52 million cell mesh exhibited noticeable deviations. To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, the mesh with 2.35 million cells was selected for all subsequent simulations. The computation utilized a hybrid approach combining CPU serial processing and GPU parallel acceleration to reduce simulation time. The time step was dynamically adjusted between 1 × 10−5 s and 5 × 10−4 s under the control of the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) condition to ensure numerical stability and solution accuracy. The simulations were considered converged when the normalized residuals fell below the following thresholds: 1 × 10−7 for volume, 1 × 10−6 for pressure, 1 × 10−7 for velocity, 1 × 10−6 for energy, and 1 × 10−9 for radiation.

Figure 5.

Axial pressure drop distribution in the calciner with different grid numbers.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Model Verification

To validate the model accuracy, operational data were collected from a full-scale industrial oxy-fuel combustion production line with an annual CO2 capture capacity of 200,000 tons located in Shandong Province, China. It should be noted that although the calciner used for model validation has a smaller capacity than the one simulated in this work, both operate under oxy-fuel combustion conditions with high CO2 concentrations. The validation case shares fundamental similarities with the simulated calciner in: (1) identical raw meal and fuel compositions; (2) a consistent two-stage feeding system with coal injection below raw meal dispersion boxes; (3) comparable operating conditions, including similar cross-section average gas velocity in the calciner and CO2 concentration levels. This ensures that their fundamental characteristics are consistent, thereby supporting the validation of the model under high CO2 atmospheres. The structure of the oxy-fuel calciner is shown in Figure 6. As summarized in Table 5, simulated results are compared with measured parameters at the calciner outlet, including temperature, pressure, CO2 and CO concentrations, and raw meal decomposition rate. The comparison demonstrates strong consistency between the simulated and experimental values, confirming the model’s reliability in predicting combustion characteristics and raw meal conversion behavior under actual operating conditions.

Figure 6.

Diagram of the oxy-fuel calciner used for model verification.

Table 5.

Comparison of simulation and operational data at the calciner outlet.

4.2. Gas–Solid Flow Characteristics

In industrial calciners, the gas–solid flow field serves as the macroscopic manifestation of particle motion, with well-developed flow patterns being essential for optimal operational performance. This study examines the complex coupling of gas–solid flow with heat/mass transfer and chemical reactions under oxy-fuel combustion conditions.

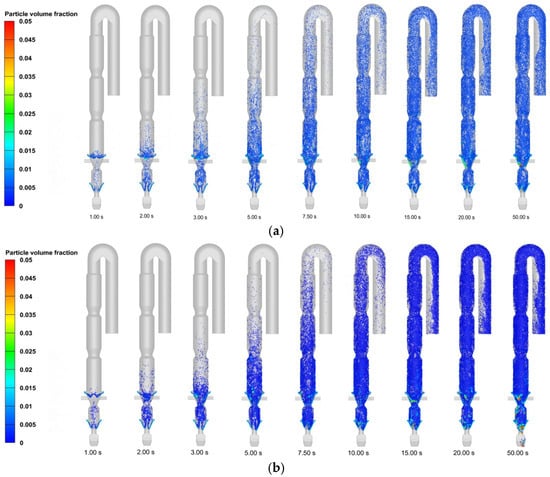

Figure 7 illustrates the temporal evolution of particle motion in the calciner. During the initial 0–10 s period, raw meal introduced through the suspension duct exhibits downward movement followed by upward countercurrent motion along the gas flow direction. This flow reversal results from fluid resistance effects generated by the concurrent introduction of kiln exhaust gas and tertiary air. The system achieves progressive stabilization after 15 s, with both hydrodynamic patterns and particle dynamics reaching steady-state conditions. The flow regime demonstrates distinct spatial characteristics: turbulent fluidization predominates in the constricted section beneath the raw meal feeding point, where high-speed jet airflow promotes effective particle dispersion. Above this region, the columnar section functions as a dilute phase zone, with particles being transported upward by the gas stream. The particles complete their trajectory through the system by passing sequentially through the gooseneck and downward pipeline before ultimately exiting the calciner.

Figure 7.

Temporal evolution of particle volume fraction in the calciner following raw meal feeding: (a) air combustion; (b) oxy-fuel combustion.

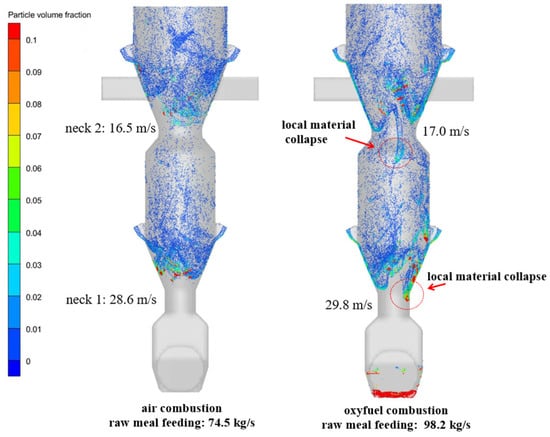

Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of particle distribution within the raw meal feeding section under air and oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Simulation results for the calciner show the bottom throat maintains average gas velocities between 28 and 30 m/s. Specifically, air combustion conditions yield a velocity of 28.6 m/s with a solid-to-gas mass ratio of 1.25, while oxy-fuel combustion produces 29.8 m/s with a corresponding ratio of 1.73. This represents a 38.4% increase in solid loading under oxy-fuel operation. The simulated flow patterns reveal distinct behavioral differences: air combustion enables complete raw meal dispersion without material accumulation, while oxy-fuel combustion with its higher feeding rates and solid loading leads to localized material collapse in the bottom throat region.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of particle distribution under air combustion and oxy-fuel combustion conditions.

4.3. Pressure Distribution Characteristics

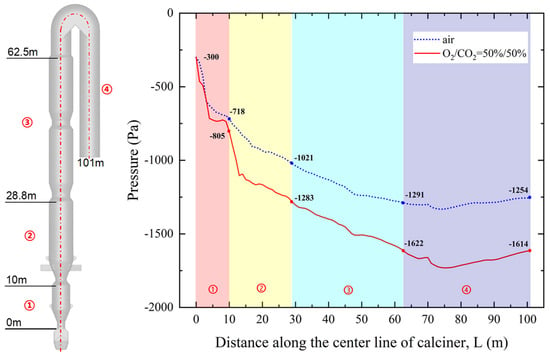

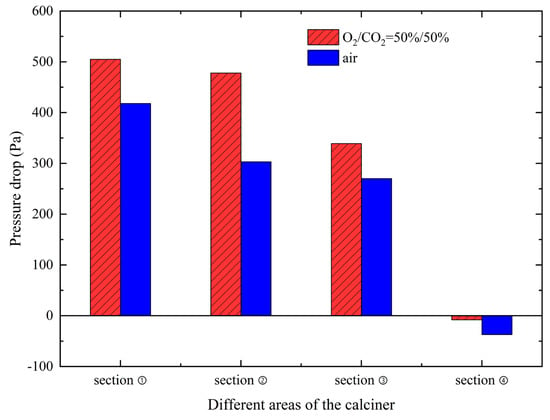

Pressure distribution analysis reveals significant differences between air and oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Under the same inlet pressure conditions, air combustion produces an outlet pressure of −1254 Pa with a total pressure drop of 954 Pa, while oxy-fuel combustion results in a lower outlet pressure of −1614 Pa and a corresponding pressure drop of 1314 Pa. This represents a 37.7% increase in pressure drop under oxy-fuel operation.

To localize the source of this increased pressure drop, the calciner was divided into four distinct zones along its length: the Reducing Zone (0–10 m) between the bottom throat and first column section; Combustion Zone 1 (10–28.8 m) between the second throat and second column section; Combustion Zone 2 (28.8–62.5 m) encompassing the third and fourth throats with their column sections; and the Reverse Downflow Zone (62.5–101 m) connecting the top gooseneck to the downward pipeline. Analysis shows that approximately 69% of the additional pressure drop in oxy-fuel combustion occurs in the Reducing Zone and Combustion Zone 1.

This phenomenon is attributed to the increased solid-to-gas mass ratio under oxy-fuel conditions. The higher solid loading impedes effective dispersion of raw meal upon entry into the calciner, leading to increased material accumulation in the throat sections and consequently higher flow resistance. These findings are visually supported by the pressure distribution comparison presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of pressure distribution along the calciner between oxy-fuel combustion and air combustion.

Further analysis in Figure 10 confirms that all four sections experience increased pressure drops under oxy-fuel conditions. A notable observation is the negative pressure drop in the reverse downflow section under both combustion modes. This phenomenon arises because the gravitational force on the particles acts in the same direction as the flow in the downward pipeline, and its magnitude surpasses the inherent flow resistance. The overall pressure increase across the calciner is primarily due to the elevated solid-to-gas mass ratio under oxy-fuel operation. This higher solid loading hinders the effective dispersion of the raw meal, causing material to accumulate in the constrictive throat sections and thereby increasing the flow resistance.

Figure 10.

Comparison of pressure drop in different areas of the calciner between oxy-fuel combustion and air combustion.

4.4. Temperature Distribution Characteristic

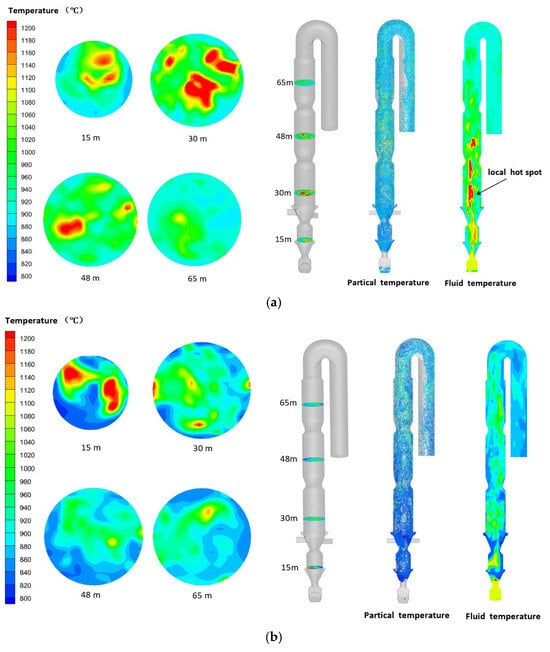

The thermal energy within the calciner originates primarily from the combustion of pulverized coal volatiles and char. The gas–solid temperature distribution directly reflects the combustion status, as illustrated in Figure 11 for both air and oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Due to the endothermic nature of raw meal decomposition, the temperature rise in solid particles depends mainly on the heat released from fuel combustion and interphase heat transfer. Consequently, raw meal particles consistently exhibit lower temperatures than the surrounding gas phase.

Figure 11.

Temperature distribution of particles and fluid phases in the calciner: (a) oxy-fuel combustion and (b) air combustion.

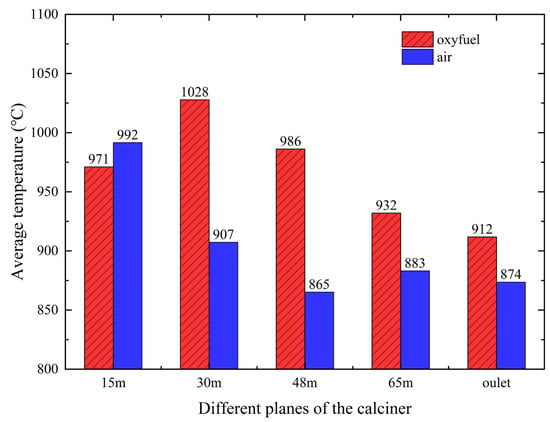

To analyze the temperature distribution under different combustion conditions, four horizontal planes were selected at heights of 15 m, 30 m, 48 m, and 65 m. These correspond to key regions within the calciner: the 15 m plane in the middle of the reducing zone, the 30 m plane in combustion zone 1, and the 48 m and 65 m planes within the two column sections of combustion zone 2. As shown in Figure 12, localized high-temperature zones appear at the 15 m and 30 m planes under both combustion conditions, resulting from concentrated heat release during coal combustion. When pulverized coal enters the reducing zone at the calciner cone, it undergoes thermal decomposition by the 1100 °C flue gas from the kiln inlet chamber, releasing volatiles that undergo partial combustion. The subsequent convergence of coal with tertiary air in combustion zone 1 establishes this region as the primary combustion area. Under oxy-fuel conditions, the elevated oxygen concentration in tertiary air accelerates combustion rates, while the localized high-oxygen zone above the tertiary air inlet promotes high-temperature region expansion through enhanced combustion intensity.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the average temperature in different planes of the calciner between the oxy-fuel combustion and air combustion.

The observed high-temperature zones under oxy-fuel conditions may pose operational challenges. When temperatures exceed 1200 °C, raw meal components can start to melt and adhere to the refractory walls, potentially causing buildups and material damage over time. While this study focuses on the combustion and decomposition processes, these findings highlight the need for proper material selection and temperature management in practical applications to ensure long-term operational stability.

Figure 12 further compares the average temperatures across different calciner planes between oxy-fuel and air combustion. The increased raw meal feeding rate under oxy-fuel operation enhances heat absorption in the reducing zone, lowering the raw material temperature by 21 °C compared to air combustion. However, upon entering the combustion zone, the elevated decomposition temperature under high CO2 concentration leads to significantly higher gas and particle temperatures in oxy-fuel operation. Specifically, temperatures in combustion zone 1 and at the calciner outlet exceed those under air combustion by 121 °C and 38 °C, respectively.

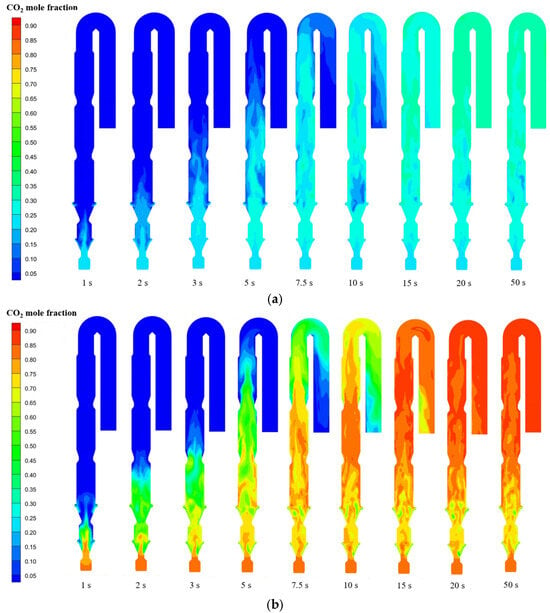

4.5. CO2 Concentration and Distribution Characteristics

Oxy-fuel combustion technology replaces conventional air (O2/N2) with industrial oxygen, significantly increasing CO2 concentration in the flue gas to facilitate subsequent carbon capture, utilization, and storage. The enrichment of CO2 during combustion thus represents a key feature of this technology. Figure 13 illustrates the dynamic evolution of CO2 formation under oxy-fuel combustion conditions. Initially filled with air, the calciner undergoes a transition as gas streams with specified CO2 concentrations are introduced. The inlet gases reach the outlet within 10 s, while the CO2 distribution stabilizes after approximately 20 s. From combustion zone 1 upward, the CO2 concentration gradually increases, stabilizing at approximately 87% upon entering the top reverse downward duct. In contrast, the reducing zone and combustion zone 1 maintain relatively low CO2 concentrations around 50%. This reduction arises from two primary mechanisms: dilution by oxygen in the tertiary air stream and consumption of CO2 through reverse synthesis reactions with residual CaO in the raw meal. During the initial stage after the raw meal is fed into the calciner, the material temperature remains relatively low. Upon contact with the flue gas characterized by high CO2 concentration, a portion of the previously decomposed CaO may undergo re-carbonation, forming CaCO3 again. These carbonation reactions occur preferentially in the low-temperature, high-CO2 environment near the feeding point, locally reducing CO2 concentration.

Figure 13.

Temporal evolution of CO2 mole fraction in calciner: (a) air combustion; (b) oxy-fuel combustion.

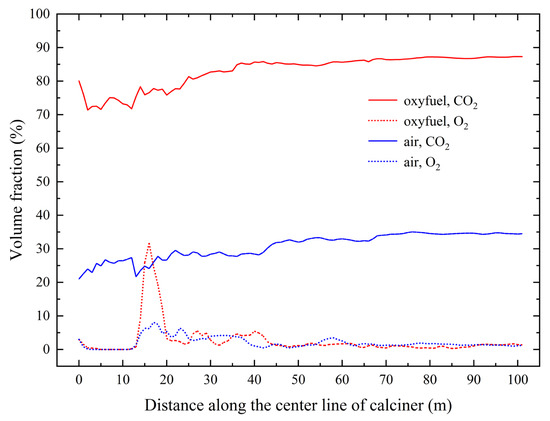

Figure 14 compares the axial distributions of CO2 and O2 concentrations under oxy-fuel and air combustion. Under oxy-fuel conditions, the average CO2 concentration reaches 83.1% throughout the calciner, with the outlet concentration attaining 87.3%. In contrast, conventional air combustion produces an average concentration of 31.0% and an outlet value of 34.4%, confirming the substantial enhancement in CO2 concentration achieved through oxy-fuel operation. The O2 distribution patterns remain generally similar between the two combustion modes, with notable differences confined to the region approximately 10 m downstream of the tertiary air inlet. This similarity indicates that pulverized coal combustion occurs primarily in combustion zone 1 under both conditions. With comparable excess air coefficients, the outlet O2 concentrations remain similar for both combustion modes.

Figure 14.

Distribution of CO2 and O2 concentrations along the axis of the calciner.

The present simulation was conducted under a typical oxy-fuel condition with 50% oxygen concentration in the tertiary air. This condition resulted in a 38.4% increase in the solid-to-gas ratio compared to conventional air combustion. It should be noted that the oxygen concentration is intrinsically linked to the CO2 flue gas recirculation ratio. A decrease in recirculated CO2 leads to higher oxygen concentration, while an increase in CO2 recirculation results in correspondingly lower oxygen levels. The 50% O2 condition was selected as the optimal operating point after comparative analysis of multiple simulation cases. Further sensitivity analysis reveals that elevated oxygen concentrations with reduced CO2 recirculation would lead to lower gas flow rates. This would further increase the solid-to-gas ratio and consequently raise the risk of material collapse within the calciner. Conversely, lower oxygen concentrations with increased CO2 recirculation would result in higher flue gas volumes, leading to greater heat loss and adversely affecting energy efficiency.

The findings of this study provide important insights into downstream CO2 capture and system energy efficiency. The observed high concentration of CO2 in the flue gas can significantly reduce the energy consumption required for subsequent purification and compression processes in the CO2 capture unit, in contrast to post-combustion capture, which typically deals with dilute CO2 streams and thus demands higher energy input for separation. Furthermore, the substantial reduction in flue gas volume after oxy-fuel combustion decreases the heat loss carried away by the exhaust gases, thereby contributing to lower energy consumption per ton of clinker produced.

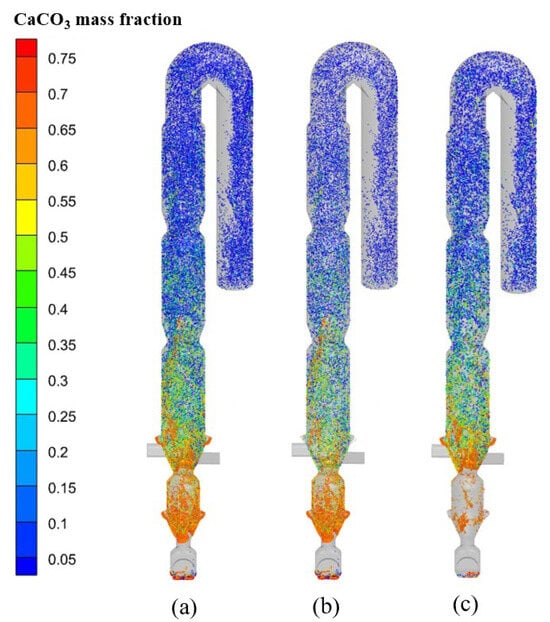

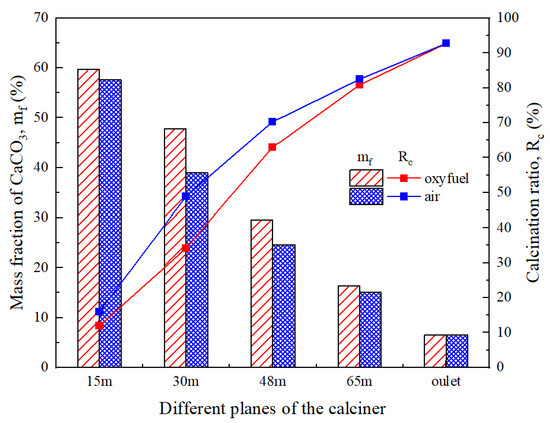

4.6. Raw Meal Decomposition Characteristics

The CO2 in flue gas originates predominantly from calcium carbonate decomposition. Figure 15 displays the CaCO3 mass fraction distribution in raw meal under oxy-fuel combustion conditions. The primary decomposition occurs in combustion zone 1, where endothermic calcination and exothermic fuel combustion proceed simultaneously. Additionally, the CaCO3 content in raw meal fed through the upper spreader slightly exceeds that introduced via the lower spreader. Figure 16 compares the progression of calcium carbonate decomposition under oxy-fuel versus air combustion. The decomposition rate under oxy-fuel conditions initially lags behind air combustion due to the elevated CO2 concentration within the calciner, which thermodynamically suppresses calcination. However, with the higher operating temperatures characteristic of oxy-fuel combustion, the decomposition rate accelerates markedly beyond the 30 m plane. Ultimately, the calciner outlet achieves a decomposition rate of 92.7% under oxy-fuel operation, demonstrating performance parity with conventional air combustion and meeting the material preparation requirements for the rotary kiln.

Figure 15.

Mass fraction distribution of CaCO3 in the raw meal under oxy-fuel combustion: (a) all raw meal; (b) raw meal fed into the lower spreader, and (c) raw meal fed into the upper spreader.

Figure 16.

Comparison of CaCO3 mass fraction and decomposition rate of raw meal in different planes of the calciner.

This study reveals the competitive relationship between the inhibitory effect of CO2 concentration and the promoting effect of elevated overall temperature on calcination under oxy-fuel conditions. This balance can be quantitatively analyzed from the perspective of the thermodynamic equilibrium of the limestone decomposition reaction. The equilibrium CO2 partial pressure , which determines the driving force for decomposition, can be calculated using the established empirical formula [50]:

where is the particle temperature (K).

Calcination of CaCO3 proceeds only when the local CO2 partial pressure is below . The exponential relationship in Equation (19) indicates that higher CO2 concentrations require increased equilibrium temperatures, thereby intensifying the inhibitory effect on raw meal calcination. However, our simulations demonstrate that the temperature rise under oxy-fuel conditions sufficiently elevates to exceed the actual , overcoming this limitation and achieving a high calcination rate despite the high CO2 environment.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the multiphysics processes in an industrial-scale oxy-fuel cement calciner operating with 50% oxygen concentration in the tertiary air using a validated CPFD model. The main findings are summarized as follows:

- Oxy-fuel combustion significantly altered the hydrodynamics inside the calciner, increasing the solid–gas mass ratio by 38.4% and the total system pressure drop by 37.7%, with the most pronounced flow resistance occurring in the constriction zones of the reduction and main combustion zones.

- The elevated oxygen concentration intensified combustion characteristics, resulting in localized temperatures exceeding 1200 °C above the tertiary air inlet, which requires careful thermal management to maintain operational stability.

- A competitive mechanism was identified between the inhibitory effect of high CO2 partial pressure on calcination kinetics and the promoting effect of elevated operating temperature, ultimately enabling a raw meal decomposition rate of 92.7% that meets industrial requirements for kiln feed.

- The results demonstrate the technical feasibility of oxy-fuel combustion in cement calciners under the specified operating conditions.

The insights gained into the mechanisms governing gas–solid flow, combustion behavior, and the calcination process under high CO2 concentration provide valuable references for the design and operational optimization of industrial oxy-fuel cement calciners. Future work will focus on NOx formation and emission characteristics under oxy-fuel conditions, along with the combustion compatibility of alternative fuels in the oxy-fuel calciner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; methodology, M.L.; formal analysis, Z.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; supervision, C.Z. and X.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFE0208200), the Major Science and Technology Research Project of the National Building Materials Industry (202201JBGS07-03), and the Key Core Technology Research Project of the China National Building Material Group (2021HX0101).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Changhua Chen, Minyan Lin, Zhouzheng Jin, Xueping Peng were employed by the company Tianjin Cement Industry Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Cv | Specific heat capacity (J/(kg·K)) | Sh | Interphase heat transfer (J/m3) |

| dp | Particle diameter (m) | Enthalpy diffusion term (J/m3) | |

| Cd | Fluid drag coefficient | q | Gas phase heat flux (J/m3) |

| Dp | Phase drag coefficient | Qnet | Lower heat value of the fuel (kJ/kg) |

| Cs | Turbulent coefficient | Greek symbols | |

| D | Turbulent diffusivity (m2/s) | θ | Volume fraction |

| g | Gravitational acceleration vector(m/s2) | ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| h | Enthalpy (J/kg) | τf | Fluid stress tensor |

| m | Mass (kg) | τP | Particle contact stress (Pa) |

| p | Gas pressure (Pa) | τD | Particle impact damping time (s) |

| T | Temperature (K) | μt | Turbulent viscosity (Pa·s) |

| u | Velocity vector (m/s) | μf | Fluid viscosity (Pa·s) |

| F | Interphase force (Pa) | λf | Gas thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)) |

| Nusselt number | Δ | LES filter width (m) | |

| xp | Particle position vector (m) | Φ | Viscous dissipation (J/m3) |

| Yf,i | Mass fraction of gas species i | ||

| f | Probability density function | Subscripts | |

| Re | Reynolds number | i | Species i |

| Energy source term (J/m3) | f | Gas phase | |

| Mass source term (kg·m−3·s−1) | p | Particle phase | |

| t | Time (s) | ||

| Sij | Strain rate tensor (s−1) | Symbols | |

| A | Surface area (m2) | [ ] | Fluid concentration (mol·m−3) |

| rp | Particle radius (m) | ||

References

- IEA CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Gong, P.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Mei, K.; Gao, Q.; Cheng, X. Study on the effect of CaCO3 whiskers on carbonized self-healing cracks of cement paste: Application in CCUS cementing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 321, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Cement. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/cement (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Benhelal, E.; Shamsaei, E.; Rashid, M.I. Challenges against CO2 abatement strategies in cement industry: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 104, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECRA CCS-Carbon Capture and Storage. Available online: https://ecra-online.org/research/ccs/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, S. Numerical Simulation of Oxy-fuel Combustion with Different O2/CO2 fractions in Large Cement Precalciner. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4949–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toftegaard, M.B.; Brix, J.; Jensen, P.A.; Glarborg, P.; Jensen, A.D. Oxy-fuel combustion of solid fuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 581–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Yan, J. Oxy-fuel combustion of pulverized fuels: Combustion fundamentals and modeling. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 742–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calic LEILAC: Capturing CO2 in Cement Precalciners. Available online: https://calix.global/news/leilac-capturing-co2-in-cement-precalciners/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Fantini, M.; Spinelli, M.; Magli, F.; Consonni, S. Calcium Looping technology demonstration in industrial environment: The CLEANKER project and status of the CLEANKER pilot plant. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cormos, C.C. Techno-economic assessment of calcium and magnesium-based sorbents for post-combustion CO2 capture applied in fossil-fueled power plants. Fuel 2021, 298, 120794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.C.; Spinelli, M.; Campanari, S.; Consonni, S.; Marchi, M.; Pimpinelli, N.; Cinti, G. The Calcium Looping Process for Low CO2 Emission Cement Plants. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; He, X.; Peng, X.; Chen, C.; Li, Z. Experimental study and CFD modeling of NOx reduction and reductive gas formation in deep reburning of cement precalciner. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 229, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffknecht, G.; Al-Makhadmeh, L.; Schnell, U.; Maier, J. Oxy-fuel coal combustion—A review of the current state-of-the-art. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, S16–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Maldonado, F.; Spörl, R.; Fleiger, K.; Hoenig, V.; Maier, J.; Scheffknecht, G. Oxy-fuel combustion technology for cement production−State of the art research and technology development. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 45, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronaki, I.; Prentza, L.; Papaefthimiou, V. Modeling of CO2 capture via chemical absorption processes An extensive literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardarsdottir, S.; Lena, E.D.; Romano, M.; Roussanaly, S.; Cinti, G. Comparison of Technologies for CO2 Capture from Cement Production—Part 2: Cost Analysis. Energies 2019, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magli, F.; Spinelli, M.; Fantini, M.; Romano, M.; Gatti, M. Techno-Economic and Off-Design Analysis of Two CO2 Purification Units for Low-Carbon Cement Plants with Oxy-Fuel Calcination. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies GHGT-15, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 15–18 March 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham, T.R.; Marier, P. Kinetic studies on the thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1963, 41, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, E.P.; Cutler, I.B.; Wadsworth, M.E. Calcium Carbonate Decomposition in Carbon Dioxide Atmosphere. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1958, 41, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khinast, J.; Krammer, G.F.; Brunner, C.; Staudinger, G. Decomposition of limestone: The influence of CO2 and particle size on the reaction rate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996, 51, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Labiano, F.; Abad Secades, A.; Diego Poza, L.F.D.; Gayán Sanz, P.; Adánez Elorza, J. Calcination of calcium-based sorbents at pressure in a broad range of CO2 concentrations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 2381–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.W.D. The mechanism of the thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1968, 23, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgwardt, R.H. Calcination kinetics and surface area of dispersed limestone particles. Aiche J. 1985, 31, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escardino, A.; Garcia-Ten, J.; Feliu, C. Kinetic study of calcite particle (powder) thermal decomposition: Part I. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinggang, L.; Lihui, Z.; Feng, D. Effect of the Dried and Hydrothermal Sludge Combustion on Calcium Carbonate Decomposition in a Simulated Regeneration Reactor of Calcium Looping. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4745–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammaria, G.L. Leon, Catalytic effect of water on calcium carbonate decomposition. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 33, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisha, Y.H.; Dugwell, D.R. Coal combustion and limestone calcination in a suspension reactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1992, 47, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, L.; Jidong, L.; Lvqing, C.; Xinhua, X.; Zhixiang, L. Experimental Study on the Dynamic Process of NO Reduction in a Precalciner. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 4366–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.R.; Turrado, S.; Abanades, J.C. Calcination kinetics of cement raw meals under varied CO2 concentrations. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 2129–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywanski, J.; Czakiert, T.; Muskala, W.; Sekret, R.; Nowak, W. Modeling of solid fuels combustion in oxygen-enriched atmosphere in circulating fluidized bed boiler: Part 1. The mathematical model of fuel combustion in oxygen-enriched CFB environment. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywanski, J.; Czakiert, T.; Muskala, W.; Sekret, R.; Nowak, W. Modeling of solid fuel combustion in oxygen-enriched atmosphere in circulating fluidized bed boiler: Part 2. Numerical simulations of heat transfer and gaseous pollutant emissions associated with coal combustion in O2/CO2 and O2/N2 atmospheres enriched wit. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, C.; Duan, L.; Liu, D.; Chen, X. CFD modeling of oxy-coal combustion in circulating fluidized bed. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, C.; Duan, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, D. A simulation study of coal combustion under O2/CO2 and O2/RFG atmospheres in circulating fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, D.; Duan, L.; Ma, J.; Xiong, J.; Chen, X. Three-dimensional CFD simulation of oxy-fuel combustion in a circulating fluidized bed with warm flue gas recycle. Fuel 2018, 216, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, D.M.; Clark, S.M.; O’Rourke, P.J. Eulerian–Lagrangian method for three-dimensional thermal reacting flow with application to coal gasifiers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.B.; Jackson, R. Fluid Mechanical Description of Fluidized Beds. Equations of Motion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1967, 6, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R. The Dynamics of Fluidized Particles. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963, 91, 99–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, P.J. Collective Drop Effects on Vaporizing Liquid Sprays. Ph. D. Thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Snider, D.M.; O’Rourke, P.J. The Multiphase Particle-in-Cell (MP-PIC) Method for Dense Particle Flow; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.E.; Crighton, D.G. Solitons, solitary waves, and voidage disturbances in gas-fluidized beds. J. Fluid Mech. 1994, 266, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, J.C.; Eikeland, M.S.; Moldestad, B.M.E. In analyzing the effects of particle density, size and size distribution for minimum fluidization velocity with eulerian-lagrangian cfd simulation, Linköping Electronic Conference Proceedings. In Proceedings of the 58th Conference on Simulation and Modelling (SIMS 58), Reykjavik, Iceland, 25–27 September 2017; pp. 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Zhong, W.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, G. Simulation of Combustion of Municipal Solid Waste and Coal in an Industrial-Scale Circulating Fluidized Bed Boiler. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 14248–14261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Rasmussen, C.L.; Giselsson, T.; Glarborg, P. Global Combustion Mechanisms for Use in CFD Modeling under Oxy-Fuel Conditions. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinov, N.M.; Westbrook, C.K.; Pitz, W.J. Detailed and global chemical kinetics model for hydrogen. In Office of Scientific & Technical Information Technical Reports; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Smoot, L.D.; Hill, S.C.; Fletcher, T.H. Global Rate Expression for Nitric Oxide Reburning. Part 2. Energy Fuels 1996, 10, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches-Ducarne, E.; Dolignier, J.C.; Marty, E.; Martin, G.; Delfosse, L. Modelling of gaseous pollutants emissions in circulating fluidized bed combustion of municipal refuse. Fuel 1998, 77, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.S. NOx from Cement Production—Reduction by Primary Measures; DTU Orbit: Lyngby, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, N.; Scaroni, A.W. Calcination of pulverized limestone particles under furnace injection conditions. Fuel 1996, 75, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, M.; Grévain, D.; Jensen, L.S.; Glarborg, P.; Wu, H. NO emission from cement calciners firing coal and petcoke: A CPFD study. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 5, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I. The combustion rates of coal chars: A review. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 1982, 19, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Li, P.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Guo, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z. Evaluation, development, and application of a new skeletal mechanism for fuel-NO formation under air and oxy-fuel combustion. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 199, 106256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Shi, G.; Hu, F.; Liu, Z. Homogeneous Fuel-NO Mitigation during Flameless Oxy-Combustion of CH4/NH3 Mixtures. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 3266–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).