Abstract

The urgent pursuit of climate-resilient agriculture and clean energy systems, central to the Energy–Agriculture Nexus and the UN Sustainable Development Goals, has accelerated global interest in agrivoltaic (Agri-PV) technologies. This paper presents a global systematic review and meta-analysis of 160 peer-reviewed studies, structured through a five-stage thematic synthesis: (1) mapping global and regional Agri-PV deployment and potential, (2) analyzing system design and modeling methodologies, (3) evaluating crop suitability under partial shading, (4) reviewing enabling policies and regulatory frameworks, and (5) assessing techno-economic feasibility and investment barriers. Results reveal that Europe and Asia lead Agri-PV development, driven by incentive-based policies and national tenders, while limited regulatory clarity and high capital costs constrain wider adoption. Despite technological progress, no integrated model fully captures the coupled energy, water, and crop dynamics essential for holistic assessment. Strengthening economic valuation, policy coherence, and standardized modeling approaches will be critical to scale Agri-PV systems as a cornerstone of sustainable and climate-resilient land use.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

Solar photovoltaic (PV) technology has grown as a key renewable energy resource for electricity generation. By the end of 2023, global PV installed capacity reached 450 gigawatts (GW) [1]. Ground-mounted PV systems are the most common type for renewable power generation [2]. Climate change and a growing global population are putting food security at risk, increasing competition for limited land resources [3]. Ground-mounted PV systems occupy valuable farmland, leading to potential conflicts between using land for food production or electricity generation [4]. This issue is particularly crucial in developing countries, where population growth aggravates demand for water, energy, and food, stretching the delicate balance of the water–energy–food nexus [5]. This is intensified by climate change, leading to severe negative impacts [6]. Water scarcity limits irrigation, reduces crop yields, and poses a direct threat to food security [7,8]. Furthermore, the reduced availability of water affects energy production, particularly in hydropower-dependent regions [9]. While population growth aggravates the energy demand in developing countries [10]. This leads to increased costs, a lack of economic stability, and higher vulnerability to climate change. To tackle these integrated challenges (Water–Energy–Food Nexus), there is a need for an integrated solution [11,12].

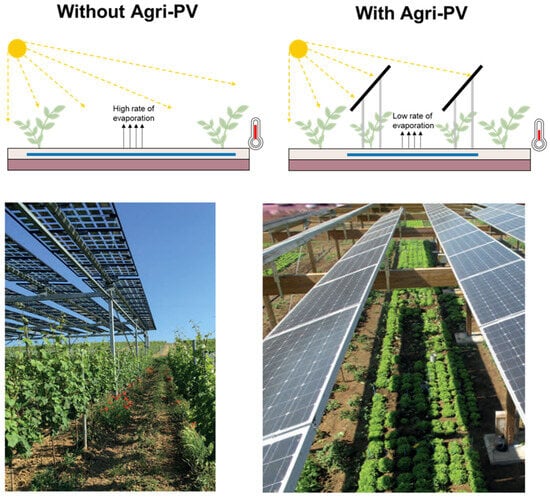

Scientists have developed Agri-PV, an innovative technology that combines agriculture (land use) with PV systems [13]. By placing PV panels over the crops, Agri-PV makes it possible to use land for dual energy generation as well as agricultural activities. The latter synergy maximizes land productivity and offers more streams of income to the farmers via the production of renewable energy. More than three decades ago, Goetzberger and Zastrow (1982) introduced the concept of Agri-PV [14]. Agri-PV is gaining attention for its potential to tackle climate change and resource scarcity. Research shows that PV panels can reduce plant heat stress and water loss, boosting crop yields—especially in arid regions [15]. Furthermore, Agri-PV systems can contribute to enhancing energy security in rural/remote areas where farms are not connected to the national grid [16]. Figure 1 showcases the illustration of Agri-PV technology and real-life installation.

Figure 1.

Concept of Agri-PV and real-life installation example based on [14,17].

1.2. Academic Perspective and Need for Research

The growing academic attention to Agri-PV reflects its potential as an interdisciplinary solution that integrates sustainable farming with renewable energy generation. Recent studies increasingly address not only the technical and agronomic aspects but also the economic, social, and policy dimensions of Agri-PV implementation across diverse regions. Positioned at the intersection of the water–energy–food nexus, Agri-PV is emerging as a next-generation approach that supports climate-resilient agriculture and advances global sustainability goals.

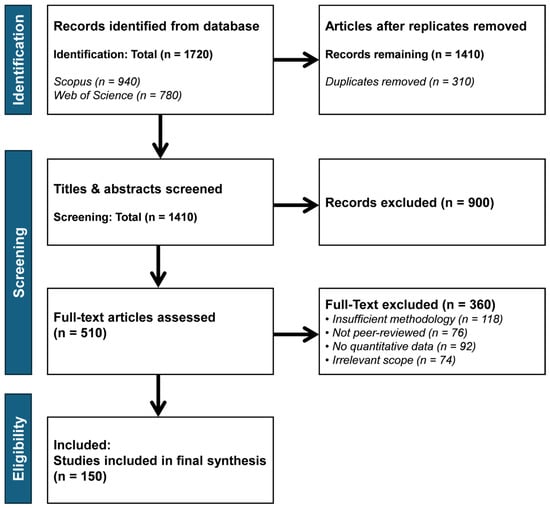

Studies were considered eligible if they focused on Agri-PV or the dual use of agricultural land for energy generation and food production, and if they presented empirical findings, simulation outcomes, techno-economic assessments, or systematic syntheses relevant to crop, energy, or environmental performance. Only peer-reviewed journal articles were retained. Publications were excluded if they did not explicitly address Agri-PV, contained insufficient or non-extractable data, or lacked methodological transparency. Non-peer-reviewed materials such as conference abstracts, editorials, and reports were excluded. In cases of duplication or overlap, the most comprehensive and methodologically sound version was retained. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a total of 1720 records were initially identified across the two databases: 940 from Scopus and 780 from Web of Science. After removing 310 duplicates, 1410 unique records remained for screening. Title and abstract screening excluded 900 papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The full text of the remaining 510 studies was then assessed for eligibility. Of these, 360 were excluded due to insufficient methodological detail (n = 118), lack of peer review (n = 76), absence of quantitative or simulation data (n = 92), or irrelevance to Agri-PV scope (n = 74). Ultimately, 150 studies met all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the final qualitative synthesis and meta-analysis. The entire selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 2), which outlines the four sequential stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. This systematic approach ensures methodological transparency, reproducibility, and a robust evidence base for evaluating the technological, policy, and economic dimensions of Agri-PV systems worldwide.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram of the articles for the presented review work.

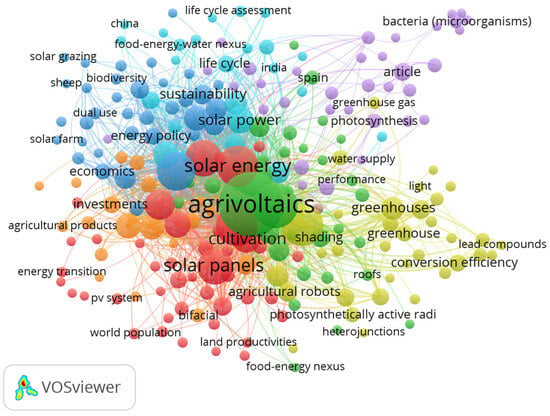

Using the analyzed data, a bibliographic map was created with VOS Viewer [18] and is presented in Figure 3. This analysis identified a total of 226 keywords, which are organized into 5 different clusters (Cluster 1 (red): System design and micro-climate, Cluster 2 (green): Agronomic performance, Cluster 3 (blue): Energy optimization, Cluster 4 (yellow): Economics and policy and Cluster 5 (purple): Environmental impacts). These clusters represent key research themes and highlight the connections between different topics in the field. The visualization provides a clear view of the research landscape and illustrates how various topics/concepts and studies are interrelated on the topic of Agri-PV.

Figure 3.

Bibliometric network of frequently used keywords, where circle size and label reflect keyword frequency, and link width indicates co-occurrence strength between terms. Node size = keyword frequency; edge width = co-occurrence strength. Colors: design (red), agronomy (green), energy (blue), economics (yellow), environment (purple), socio-economic/policy (orange).

The hub of Agri-PV, crop yield, PV appears in >40% of records, confirming that yield questions still dominate the field. The five color-coded clusters unveil more nuance: (1) design and micro-climate terms (shading, tilt-angle, spectral management); (2) agronomy (biomass, lettuce, photosynthesis); (3) energy optimization (power-output, bifacial, MPPT); (4) economics and policy (land-use efficiency, LCOE, subsidy); (5) environmental impacts (carbon footprint, soil moisture, biodiversity). Bridge keywords such as land-use efficiency and micro-climate connect the technical and policy clusters, whereas the sparse links between clusters 3 and 5 expose a gap in life-cycle studies that assess carbon, yield and micro-climate together. Overall, the map shows the literature shifting from proof-of-concept agronomy toward integrated techno-economic–ecological optimization.

1.3. Gap in the Research and Novelty of the Presented Work

Agri-PV is still an emerging technology, and research on its modeling, impact on different crops, and potential for water conservation is quite limited. So far, most scientific understanding of Agri-PV comes from a small number of installations. Globally, there are around 2000 Agri-PV systems in place, with the majority located in Europe, China, and the United States. As a result, the current body of knowledge remains in its early stages, relying heavily on theoretical data and initial case studies [19,20,21]. This highlights a significant gap in comprehensive, hands-on research in the field. With few studies available, the findings on how PV panel shading affects crop yields have been mixed and inconsistent. To date, most Agri-PV simulations have focused on a limited range of crops, including tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, kiwifruit, lettuce, and corn, to assess their compatibility. However, the effects of Agri-PV on many other widely grown and essential crops are still largely unknown [20,22]. Much of the existing research on Agri-PV has been concentrated in a handful of countries, leaving many developing regions largely unexplored. This lack of geographical diversity limits the understanding of how Agri-PV might perform in different climates and agricultural settings. Additionally, while the shading from PV panels is believed to contribute to water conservation, there is still little in-depth research examining this aspect in detail. A broader, more comprehensive investigation is needed to fully grasp the potential benefits of Agri-PV, particularly in water-scarce regions [22,23].

Economically, the field suffers from a lack of standardized techno-economic assessment frameworks. Most studies assess system performance from an engineering perspective without integrating life-cycle cost analysis, farm revenue models, or sensitivity to policy incentives. As a result, comparative evaluations of Agri-PV versus conventional PV or traditional farming are rare, and uncertainty remains regarding payback periods, investment risks, and market competitiveness. While evidence from Europe and Japan indicates that Agri-PV systems are 15–30% more expensive to install than standard ground-mounted PV, these costs are often offset by dual-income streams from energy and crop production. However, without supportive fiscal instruments such as feed-in tariffs, tax reliefs, or capital grants, Agri-PV adoption remains economically unattractive in most regions.

From a policy perspective, Agri-PV governance is fragmented and heterogeneous across countries. Although France, Germany, Japan, and China have introduced dedicated policy instruments, including differentiated auction schemes, regulatory definitions, and performance-based incentives, most nations still treat Agri-PV within the broader solar PV framework. The absence of clear land-use regulations, eligibility criteria for agricultural subsidies, and standardized technical guidelines (e.g., mounting height, transparency ratio, or land productivity thresholds) has led to regulatory uncertainty and limited farmer participation. Furthermore, developing countries, despite high solar potential, lack institutional frameworks, pilot programs, and financing models that could stimulate local Agri-PV adoption. This policy vacuum contributes to uneven deployment and reinforces regional disparities in technological diffusion. Existing literature predominantly focuses on either the agronomic or PV aspects of Agri-PV, rarely integrating them with economic feasibility or policy enablers. Consequently, there is a critical need for interdisciplinary frameworks that unify energy yield modeling, crop productivity analysis, economic assessment, and governance dimensions. Addressing these interconnections is essential for identifying viable pathways toward commercial scalability and sustainable rural transitions. A comparison of this work with other review articles in the literature is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative assessment of the presented work with the existing review articles to outline the research gap (✓ indicates that the topic is fully covered, while (✓) denotes partial coverage).

- Novel contribution of this review—four interrelated aspects pivotal for global Agri-PV deployment: Global and Country-Specific Deployment Assessment: Providing the most recent insights into international Agri-PV potential and implementation status, with a comparative analysis of enabling policy frameworks in leading countries such as Germany, France, Japan, China, and Italy. Lessons are drawn on regulatory instruments like DIN-SPEC 91434 [29], dedicated Agri-PV tenders, and 20-year feed-in tariffs, offering actionable guidance for policymakers and investors.

- Modeling and Simulation Techniques: Mapping and evaluating interdisciplinary simulation tools that integrate agronomic, PV, and economic factors. These tools are vital for optimizing Agri-PV performance across varying climatic and market conditions, and for conducting cost–benefit analyses that support decision-making.

- Crop Suitability insight: Data-driven insights that evaluate crop compatibility based on shading tolerance, water demand, and yield potential, bridging the knowledge gap between agricultural and energy planning.

- Policy–Economy–Agronomy Interface: Positioning Agri-PV as a systemic innovation within the Energy–Agriculture Nexus, where technological advancement, farmer engagement, and policy coherence converge. The review emphasizes that successful scaling requires coordinated governance, long-term financing mechanisms, and the alignment of agricultural and renewable energy policies to ensure equitable and climate-resilient land use.

2. Research Methodology

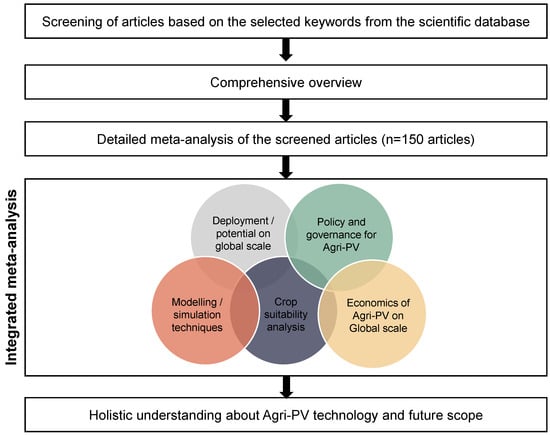

As discussed in the previous section, this study adopts a systematic review and meta-analysis approach to examine Agri-PV systems across five interlinked stages, each addressing a critical dimension of this emerging technology. The objective is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current research and policy evidence, supported by robust analytical interpretation. The approach integrates technological, agronomic, and policy perspectives to capture Agri-PV’s full potential as a driver of sustainable land use. Figure 4 presents the overall research framework. The methodology is intentionally interdisciplinary, bridging energy engineering, agricultural science, and policy analysis. It overcomes the fragmentation in existing literature by linking empirical and modeling-based evidence with an assessment of enabling and constraining regulatory environments. This holistic design supports a deeper understanding of the technical, economic, and institutional drivers shaping Agri-PV adoption worldwide.

Figure 4.

The research design of the presented article.

- Stage 1: Literature Identification and Selection

A systematic search was conducted in Scopus and Web of Science, using predefined keywords such as “Agri-PV”, “agrivoltaics”, “agriculture photovoltaic systems”, and “dual land use”. The search, updated in October 2025, followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Studies were included if they focused explicitly on Agri-PV technologies—whether experimental, simulation-based, or review-oriented—and published in peer-reviewed journals. After removing duplicates and non-relevant records, a total of 150 studies published during 2015–2025 were selected for synthesis, ensuring methodological transparency and reproducibility.

- Stage 2: Global and Regional Perspective

This stage analyzed Agri-PV deployment trends, installed capacities, and spatial distribution across regions. Comparative insights were drawn from leading markets such as Germany, France, Japan, China, Italy, and the United States. The review also assessed the theoretical and technical potential of Agri-PV at national and global scales, linking land-use efficiency with renewable energy and food security goals.

- Stage 3: Modeling and Simulation Techniques

A detailed review of interdisciplinary modeling approaches was conducted, categorizing tools into (i) PV performance models (e.g., PVSyst, PV*SOL), (ii) crop and microclimate models (e.g., AquaCrop, DSSAT), and (iii) hybrid frameworks integrating energy yield, shading effects, and water-use efficiency. These modeling techniques were compared to highlight methodological innovations that enable integrated assessment of crop productivity and energy generation.

- Stage 4: Crop Suitability Assessment

Empirical studies evaluating crop performance under Agri-PV installations were systematically examined to understand yield responses, water requirements, and shading tolerance. Based on this synthesis, a novel Crop Suitability insight was provided, integrating agronomic indicators—such as water demand, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) utilization, and yield stability—to guide evidence-based crop–PV pairing for different agro-climatic zones.

- Stage 5: Policy and Economic Analysis

Finally, the review synthesized insights on policy frameworks and economic instruments that influence Agri-PV adoption. Case studies from Germany (DIN-SPEC 91434), France (Agri-PV tenders), and Japan (MAFF directives) were analyzed to identify effective policy tools such as feed-in tariffs, auction mechanisms, and land-use regulations. Economic assessments were also reviewed to compare Agri-PV and conventional PV cost structures, highlighting factors such as higher initial investment (typically 15–30%), potential for dual-income streams, and dependency on supportive incentive schemes. Key barriers—including regulatory ambiguity, financing limitations, and limited farmer engagement—were contrasted with enablers such as clear definitions, standardization, and cross-sectoral governance. Together, these stages ensure a comprehensive understanding of Agri-PV as both a technological and policy innovation, supporting its integration into future sustainable, climate-resilient agricultural and energy systems.

3. Global Potential and Installation of Agri-PV

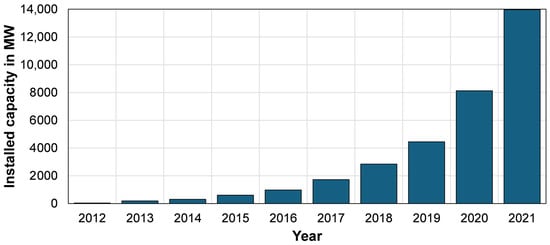

According to data from the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (ISE), the capacity of installed Agri-PV has increased significantly, from 5 megawatts (MW) in 2012 to approximately 2.9 GW in 2018, and over 14 GW in 2021 (c.f. Figure 5). This growth has been supported by national funding programs in countries such as Japan, China, France, the United States, and South Korea. The report titled “Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition—A Guideline for Germany” estimates that global Agri-PV capacity grew to over 2.8 GW by 2020, with China contributing about 1.9 GW of this total [14].

Figure 5.

Installed Agri-PV capacity worldwide in MW based on [14].

Yeligeti et al. [30] undertook a comprehensive global study to assess the potential of Agri-PV. In the study, the suitability of land is determined through a systematic review of literature focusing on the feasibility and profitability of PV systems for 18 major crop types worldwide. The study specifically evaluated the suitability of various crops for Agri-PV applications using geospatial data at a fine resolution of 10 × 10 km2. To achieve this, geodata from EarthStat and Copernicus Land Cover were employed to identify arable lands across the globe, focusing on 18 different crop types. These crops were then categorized into two groups, “Low” and “High,” based on their compatibility with Agri-PV systems. By modeling three potential scenarios, the study estimated that the global Agri-PV capacity could range from 48 terawatts (TWp) to 217 TWp. It is crucial to note that the crop suitability analysis was conducted on a global scale, without adjustments for specific regional climatic conditions.

By 2021, Fraunhofer ISE reported that the installed capacity of Agri-PV had reached 14 GW, in contrast to 1 terawatt (TW) of total installed solar capacity worldwide. China had the largest share, with 1900 MW dedicated to Agri-PV systems, including 700 MW installed over goji berry plantations near the Gobi Desert. Agri-PV has also gained prominence in European and Asian countries, particularly Japan, which hosts nearly 2000 Agri-PV installations generating more than 200 MW of electricity and supporting over 120 types of crops [14]. However, there are very limited sources of information that provide precise numbers on Agri-PV installations, indicating a significant data gap. For example, according to Chalgynbayeva et al. [20] until 2020, approximately 2200 Agri-PV systems have been installed worldwide since 2014. While, Tajima and Iida [31] as well as Doedt et al. [32] mentioned that Japan only has 2000 Agri-PV systems.

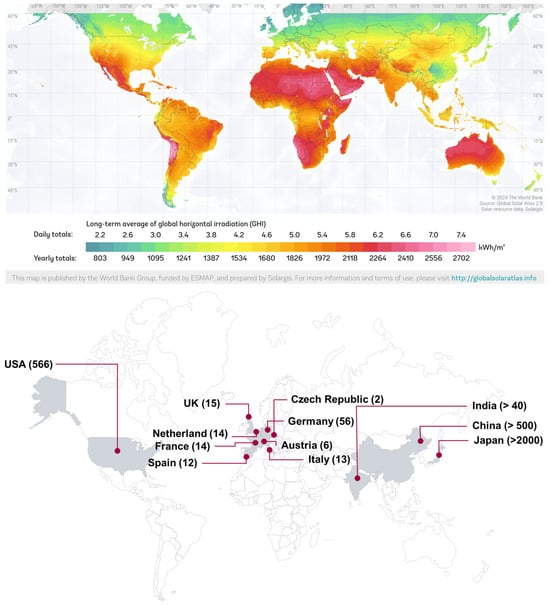

Figure 6 presents a comprehensive global analysis of existing Agri-PV installations across various regions. This graph not only shows the distribution of these installations but also overlays global solar irradiation data. It becomes evident that many sun-belt regions, characterized by high solar irradiation and significant agricultural activity contributing to GDP and livelihoods, have not yet fully explored Agri-PV technology. These regions, with their optimal conditions for both solar energy production and agriculture, represent a significant opportunity for future Agri-PV deployment.

Figure 6.

Global analysis of Agri-PV; Global solar irradiation (top) and number of Agri-PV installations based on the literature review (bottom).

Currently, notable Agri-PV installations are primarily concentrated in a few countries such as France, Italy, Germany, the USA, China, Japan, and India [20,33,34]. This analysis highlights the geographical and technological disparity in the adoption of Agri-PV systems. The details in the figure were compiled through an extensive literature review and reflect the best knowledge available to the authors. This gap in detailed, precise data on Agri-PV installations points to the necessity for more targeted research and comprehensive reporting mechanisms to better understand and optimize the integration of PV systems with agricultural practices globally. The following section presents a regional analysis of Agri-PV installations and potential in selected countries, based on insights gathered from the literature review.

3.1. Regional Analysis of Selected Countries

3.1.1. Germany

Germany has established Agri-PV systems within its legal framework, significantly propelled by the 2021 amendment to the German Renewable Energy Act [35]. The legislation launched 50 MW project bids for onshore wind, solar PV, biomass, storage, Agri-PV, and floating PV. Since 2014, the Fraunhofer ISE has led Agri-PV crop trials. In 2021, BayWa r.e., partnering with Fraunhofer ISE, began a five-year project in Gelsdorf, Germany, to study apple production using different crop protection systems, including Agri-PV [14]. German companies are driving Agri-PV innovation. In 2021, Ideematec, Inc. secured a 100 MW order for custom tracking systems in France, adapting its Horizon L:TEC® tracker for agricultural use. BayWa r.e. aims to develop 250 MWp of Agri-PV by 2025, having already completed a 1.2 MW project in the Netherlands, with more fruit-focused projects across Europe. Steag GmbH is planning three solar parks in Italy’s Apulia region, totaling 244 MW, on farmland producing olives, almonds, figs, and tomatoes [36]. Germany has made significant strides in Agri-PV by developing the first technical norm (DIN-SPEC 91434) in 2021, establishing clear rules for defining Agri-PV systems. The country also held its first Agri-PV solar tenders (competitive bidding process) in 2022.

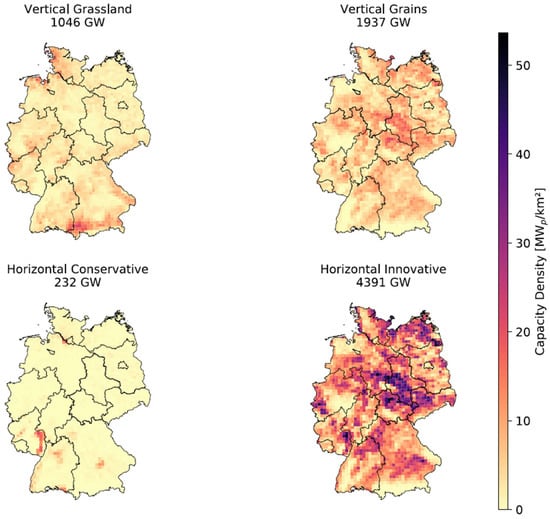

Maier et al. [37] found that the technical potential of Agri-PV varies significantly, ranging from 232 GWp in the Horizontal Conservative scenario (low performance) to 4391 GWp in the Horizontal Innovative scenario (high performance). Maier et al. [37] also noted that other studies estimate a potential of 1700 GWp for highly mounted Agri-PV in Germany, based on arable land for shade-tolerant crops and a capacity density of 60 MWp/km2. Some studies focus on crops either positively affected by Agri-PV [37,38], such as potatoes, lettuce, and spinach, or those unaffected, like rapeseed, rye, and oats. This research estimates a technical potential of 533 GWp across 12,400 km2 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Capacity density of the technical Agri-PV potential in Germany according to Maier et al. [37]. Scenarios include: Vertical Grassland (for vertical Agri-PV on grasslands), Vertical Grain (for wheat, barley, and rye with current machinery), Horizontal Conservative (for crops like lupine, soy, grapevine, hops, and orchards), and Horizontal Innovative (expanding to grains, oats, potatoes, and vegetables with adapted machinery).

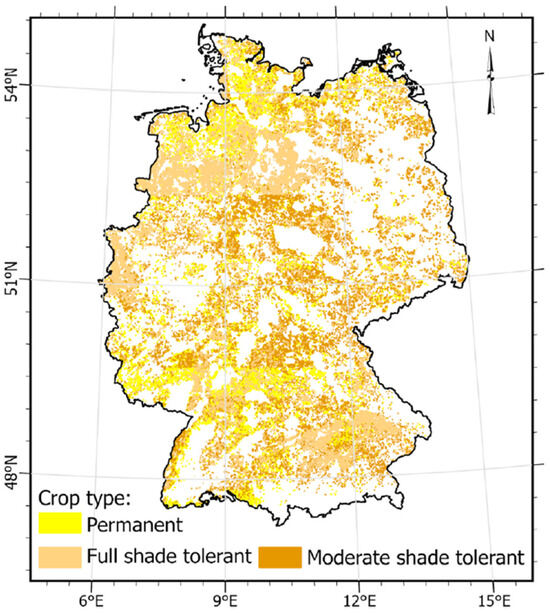

Rösch and Fakharizadehshirazi [39] assessed the spatial socio-technical potential of Agri-PV in Germany using a GIS model that combines land suitability with socio-technical constraints. Areas such as biodiversity zones, water protection zones, floodplains, and regions within 200 meters of residential and commercial areas were excluded to ensure public acceptance. The model uses crop distribution data to identify cropland that supports both food production and solar energy. Permanent crops like orchards, vineyards, and hops are particularly suited for Agri-PV, offering benefits like weather protection and cost savings. Shade-tolerant crops also experience reduced climate-related yield impacts. The study found that 17% of permanent crops, 36% of moderate shade-tolerant crops, and about 36% of full shade-tolerant crops are suitable for Agri-PV. However, crops like wheat yield less under Agri-PV systems. Moderate shade-tolerant crops, such as legumes, carrots, and onions, can handle 15–40% shading, but struggle with more than 50%. Full shade-tolerant crops include potatoes, forage, and leafy vegetables like cabbage, lettuce, parsley, and spinach (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Germany’s spatial Agri-PV potential on permanent, moderate and full shade-tolerant cropland according to Rösch and Fakharizadehshirazi [39].

3.1.2. France

France is currently the largest Agri-PV market in Europe and is considered the cradle of Agri-PV on the continent. The country has been developing Agri-PV systems since 2011, with large-scale installations of 10 hectares or more implemented from 2015 onwards [27,40,41]. In France, Agri-PV has been supported through dedicated tender rounds since 2017, aiming for 15 MWp of installed capacity annually [14]. Projects are evaluated based on price competitiveness and innovation, with a maximum project size of 3 MWp. Initially, only greenhouse projects won tenders, but subsequent rounds expanded eligibility to systems ranging from 100 kWp to 3 MWp, totaling 140 MWp per round. Successful projects secure a feed-in tariff over 20 years, with notable developments including a 40 MWp allocation in March 2020, emphasizing solar tracking PV modules. The largest European facility with such modules was established in Tresserre in 2018 [42].

Hrabanski et al. [43] investigated the political dynamics of regulating decarbonised energy technologies, specifically Agri-PV, by examining multi-level and multi-sector regulations. At the national level, the framework relies on incentive instruments, like guaranteed feed-in tariffs, to develop the market for Agri-PV and achieve decarbonisation goals. However, this framework is somewhat vague, allowing local authorities significant autonomy in regulating projects, which enables diverse local implementations. The study also highlights how Agri-PV challenges traditional boundaries between the agriculture and energy sectors, necessitating a re-evaluation of established institutions and sectoral divisions.

The French experience also highlights important political and socio-economic dynamics. Agri-PV has challenged traditional boundaries between agriculture and energy sectors, requiring new forms of collaboration between the Ministry of Agriculture, energy regulators, and local cooperatives. This has triggered debates around land use prioritization, farmer participation, and food security, particularly in regions with strong viticulture and horticultural traditions. Concerns about “greenwashing”—using the agricultural label to justify otherwise conventional solar parks—have led to calls for stricter definitions and monitoring of agricultural activity under Agri-PV frameworks. The introduction of technical guidelines specifying minimum agricultural yield retention, panel height clearances, and maximum land-use thresholds reflects attempts to safeguard the agricultural function and ensure that dual land-use remains genuine. Finally, France has also positioned itself as a knowledge hub for Agri-PV in Europe, with research programs such as Sun’Agri pioneering dynamic shading control for vineyards and orchards. These initiatives have produced valuable data on microclimatic regulation, crop yield stability, and water savings, reinforcing the case for Agri-PV as a climate adaptation strategy in southern Europe. The combination of policy instruments, local experimentation, and research-led innovation has placed France at the forefront of Agri-PV development, offering lessons for both developed and emerging economies.

3.1.3. Italy

In Italy, Agri-PV technology plays a crucial role in meeting national PV and decarbonization goals, driving agricultural innovation, and helping reduce energy costs for farms [44]. They also address land and landscape preservation issues that complicate the permitting process for PV installations in agricultural areas. Despite these advantages, Agri-PV faces economic challenges due to higher installation costs compared to standard ground-mounted PV plants. Even in high-revenue cropland areas, Agri-PV systems are rarely more economically advantageous, and their feasibility is highly dependent on location-specific agricultural revenues. PV energy from ground-mounted PV plants is generally cheaper, making Agri-PV less appealing without substantial financial incentives [45,46].

The National Plan for Recovery and Resilience (NRRP) supports the development of innovative Agri-PV systems with an investment of €1.1 billion for 1.04 GWp, highlighting Agri-PV’s potential to combine decarbonization with agricultural preservation [44]. State aids should consider not only PV electricity production but also the agricultural revenue of the land used for Agri-PV, focusing on lower-revenue croplands at risk of abandonment. This dual approach could address land abandonment while providing environmental benefits and reducing the agricultural sector’s electricity consumption [44,47]. A key policy innovation in Italy is the proposal to prioritize Agri-PV on marginal and abandoned lands. This reflects a broader strategy to counteract land abandonment in rural areas, particularly in southern regions, where declining agricultural profitability has led to socio-economic fragility. By directing Agri-PV investments to these lands, policymakers aim to revitalize rural economies, reduce dependence on imported energy, and integrate climate adaptation measures into agricultural landscapes. Recent studies also highlight the potential of Agri-PV to support water-efficient crops in drought-prone areas of southern Italy, where shading can reduce evapotranspiration and improve resilience to climate extremes. Italian research consortia such as ENEA, ENEL Green Power, and several agricultural universities have been actively piloting Agri-PV solutions since 2020, focusing on vineyards, olive groves, and other horticultural crops. These projects have generated early data on yield stability, microclimatic benefits, and biodiversity co-benefits, positioning Italy as a laboratory for Mediterranean Agri-PV applications. For instance, pilot projects in Apulia and Sicily demonstrate that elevated bifacial systems can reduce water demand by up to 20% while maintaining grape and olive yields. Despite this progress, Agri-PV in Italy continues to face permitting delays, farmer hesitancy, and social opposition in certain regions, reflecting broader debates around landscape preservation and food security. Critics caution against “pseudo-Agri-PV” projects that prioritize energy generation while neglecting agricultural output, emphasizing the need for rigorous monitoring and certification schemes. Thus, while the Italian framework recognizes Agri-PV as a dual-use innovation pathway, its success will ultimately depend on aligning financial incentives, farmer engagement, and monitoring mechanisms to ensure genuine integration of agriculture and energy.

3.1.4. Austria

In Austria, Agri-PV systems offer a promising solution for balancing renewable energy needs with agricultural production and land use. The transition to a renewable energy system over the next two decades requires the expansion of PV technology, which can conflict with open-space farming and other land uses [48,49]. As agriculture faces new challenges in energy management and climate change adaptation, Agri-PV provides a way to mitigate land-use competition and ecosystem impacts. However, the adoption of Agri-PV in Austria is limited by a lack of reliable data on its potential. To advance Agri-PV in Austria, Ressar et al. [49] suggest increasing research, improving stakeholder communication, and creating clear legal frameworks for Agri-PV implementation. This will help close the knowledge gap and support a more sustainable energy and agricultural future in Austria [48,49]. However, there are only a few documents/literature available that outline the potential of Agri-PV in Austria. Krexner [50] mentioned that by 2030, Austria aims to utilize 4700 km2 of suitable area for APV to meet its renewable energy targets. This includes achieving approximately 2.5–3% coverage with S-APV (Standard Agri-PV), where solar panels are integrated with agricultural activities, and 4–5% with VB-APV (Vertical Bifacial Agri-PV), which uses vertically mounted bifacial panels to maximize energy capture with minimal land shading.

3.1.5. United Kingdom

Garrod et al. [51] conducted the first study mapping the technical and economic potential of crop-based Agri-PV in the UK through simulations. Based on data from the UK government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) report on crop areas and yields from June 2021, the study highlighted that wheat (1,788,000 hectares) and barley (1,149,000 hectares) are the most common crops but were not considered suitable for Agri-PV due to the large machinery required for sowing and harvesting. Instead, the focus shifted to smaller-scale crops, with potatoes being identified as a suitable candidate. In 2021, 137,000 hectares were dedicated to potatoes, which are shade-tolerant, making them ideal for Agri-PV systems. The study showed significant technical and economic potential for Agri-PV across the UK, noting higher land-use efficiency, demonstrated by a higher Land Equivalent Ratio for Agri-PV systems compared to standalone PV or crop systems. However, the study also acknowledged a slight decrease in crop yields under Agri-PV systems due to the use of relatively shade-intolerant crops. Future research, the paper suggests, could focus on improving crop yields under shaded conditions to maximize the benefits of Agri-PV systems. While, Neesham-McTiernan et al. [52] estimated that Agri-PV deployment in Great Britain could theoretically generate 338 TWh/year of electricity while preserving 20,272 km2 of high-grade farmland. Their spatial analysis shows that about 92% of land with the highest PV suitability overlaps existing agricultural lands. Importantly, they find that 79.5% of existing solar parks rest on agricultural land classified as Grades 1–3, and 19.3% occupy “Best and Most Versatile” (BMV) land.

3.1.6. China

As the world’s largest PV manufacturer and a major agricultural nation with abundant solar energy resources, China has tremendous potential for PV agriculture [53]. In China, Agri-PV systems have gained significant traction due to robust government support aimed at transforming economic growth modes and fulfilling emission reduction commitments. This support began with initiatives like the Golden Sun project and the PV tariff policy, leading to a rapid increase in the domestic PV market and an improved policy environment for PV industrial development [54]. The Agri-PV industry in China is substantial, though official macro statistics are unavailable. According to Fan et al. [55] by the end of 2021, PV installations integrated with agricultural land in China surpassed 64 GW, with the share of Agri-PV steadily growing each year. In 2015, the Chinese government advanced this initiative by introducing measures to accelerate PV poverty alleviation, support PV integration into the power grid, and promote PV agriculture [54]. This clear national determination underscores the strategic importance of promoting PV agriculture as part of China’s broader goals for renewable energy expansion and sustainable development.

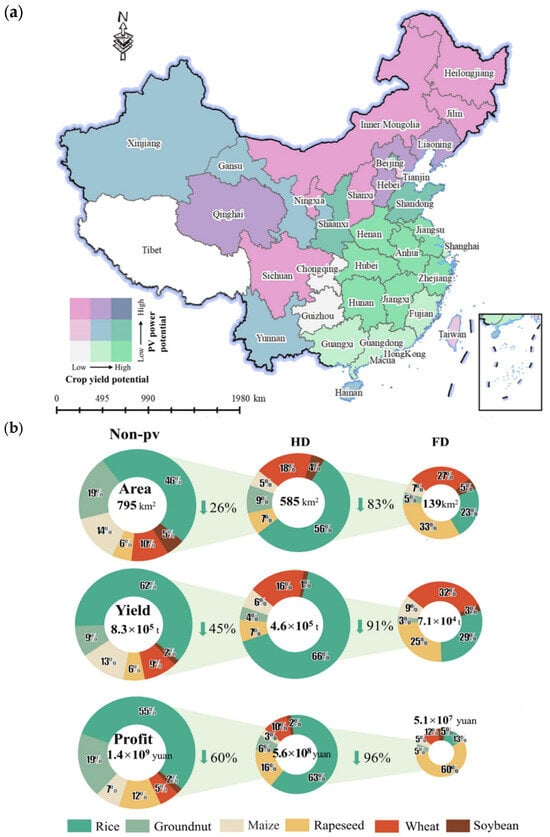

Xia et al. [56] addressed the impact of expanding utility-scale PV installations on agricultural land in China by integrating spatial data on PV systems with agricultural productivity metrics. They analyzed how different PV density scenarios—half-density and full-density—affect cropland use and crop yields. By comparing the outcomes with a no-PV baseline, they quantified how Agri-PV could mitigate land-use conflicts. Their findings reveal that while full-density PV systems could preserve 139 km2 of cropland with 9% of the original crop yield, half-density systems could conserve 585 km2 with 55% of the yield. They also noted regional differences, with northern areas showing greater Agri-PV potential. This research provides insights for optimizing the coexistence of PV installations and agricultural production. Nationally, the average crop yield and PV power potential of cropland in China are 503 t/km2 and 3.46 kWh/kWp, respectively, with significant regional variations (Figure 9a). High crop yield potential is concentrated in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, particularly in Hubei (678 t/km2), Shandong (646 t/km2), and Henan (631 t/km2). PV power potential is higher in northern provinces, with Inner Mongolia leading at 4.66 kWh/kWp, followed by Heilongjiang (4.47 kWh/kWp) and Ningxia (4.39 kWh/kWp). In a no-PV scenario, 795 km2 of cropland produced 830,000 tons of crops and 1.4 billion yuan in profits, primarily from rice, groundnut, and maize. Under half-density PV, the cultivated area shrank by 26%, with yields and profits dropping by 45% and 60%, respectively. The crop mix shifted towards more rice and wheat. With full-density PV, the area decreased by 83%, yields fell by 91%, and profits by 96%. Rice, groundnut, and maize decreased, while wheat and rapeseed increased, with wheat becoming the second-largest crop and rapeseed the top income source (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

Agri-PV potential in China (a) Spatial patterns of the crop yield potential (a) and PV power potential and (b) The cultivated area, yield, and profits of China’s occupied croplands under three scenarios: No-PV, half-density PV system (HD), and full-density PV system (FD) according to Xia et al. [56].

3.1.7. USA

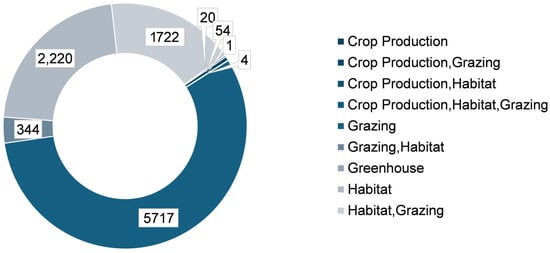

The Agri-PV approach has gained increasing attention in the USA in the context of decarbonizing the electricity sector by 2035, with solar energy anticipated to contribute up to 40% of the nation’s electricity supply. Large-scale solar installations are projected to require approximately 5.7 million acres of land, raising concerns about the displacement of agricultural activities. Currently, over 2.8 GW of Agri-PV capacity exists in the USA, with the majority involving livestock grazing or pollinator-friendly habitats, and an emerging focus on crop cultivation under solar arrays [57]. States such as Massachusetts and Colorado have implemented incentives and research programs to advance Agri-PV, highlighting its potential to reduce water use, enhance crop resilience in extreme weather, and sustain rural economies. Despite its promise, Agri-PV faces barriers, including higher initial costs, complex system designs, and uncertainties regarding crop compatibility under shaded conditions. Furthermore, community acceptance and integration into existing agricultural frameworks remain critical areas of inquiry [58]. According to the InSPIRE [59] Agri-PV map, there are a total of 589 sites in the USA, covering over 62,000 hectares and generating more than 10,000 MW of energy. As previously noted, most of these sites are associated with pastureland, with some projects having an installed capacity of up to 1 GW. For crop production, 35 sites are operational, with a combined installed capacity of 80 MW, primarily located in the central region of the USA. Figure 10 represents the system size in MW by Agri-PV projects in the USA.

Figure 10.

Agri-PV system size in MW by projects in the USA. Own illustration based on InSPIRE [59].

3.1.8. India

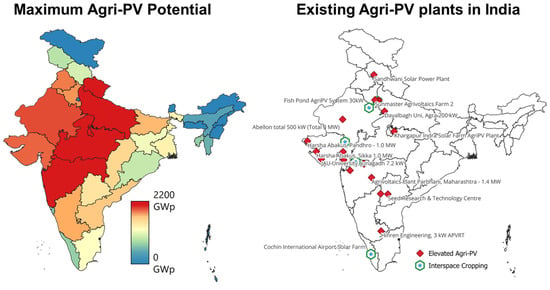

India is set to be a leader in Agri-PV technology due to its extensive agriculture, diverse crops, and high solar irradiation. With an average solar irradiation of about 5.5 kWh/m2/day and over 300 sunny days annually, India is highly suitable for solar power [60]. India’s varied agricultural sector—from cereals to cash crops—offers numerous opportunities to tailor Agri-PV systems for different crops, including shade-tolerant varieties that may benefit from partial shading [61]. Scientific studies on Agri-PV in India are currently exploring various configurations and their effects on crop yield, soil health, and overall farm productivity [62,63]. Preliminary research indicates that some crops grown under Agri-PV systems may experience comparable or even enhanced growth relative to traditional farming methods [64]. Experimental projects, such as the Indo-German collaboration on Agri-PV in Maharashtra, are instrumental in refining the technology by investigating different panel heights, angles, and crop varieties [65]. However, there is a notable gap in comprehensive scientific studies that clearly communicate the full potential of Agri-PV in India. While several reports provide insights into the technology’s feasibility, there is a need for more detailed research to quantify its benefits and guide large-scale implementation [66]. Addressing this gap will be crucial for developing effective policies and strategies to harness the potential of Agri-PV in India [65].

The report by the Indo-German Energy Forum Support Office (IGEF-SO) and the National Solar Energy Federation of India (NSEFI) offers a detailed overview of solar energy projects combined with agriculture in India. It highlights that, since January 2021, 13 solar projects on agricultural plots have been operational, collectively generating 48.4 MW of electricity [65]. Research presented in the report includes studies on the effects of solar panel shading on crop yield in Jodhpur and grape cultivation, with potential for generating up to 16,000 GWh of electricity if similar systems are widely adopted. Additionally, the report features a case study from Charanka Solar Park in Gujarat, where solar panels transformed barren land into fertile ground for tomato cultivation and enabled the export of 1.68 million kWh of electricity to the grid [60,67]. The Government must define a specific target for Agri-PV plants in India, including a year-by-year trajectory for the next 10 years. To estimate the potential of Agri-PV in the country, a conservative approach involves assuming that 1% of each category of land—agricultural, barren, and other uncultivated lands—is utilized for Agri-PV systems. Given that approximately 5.5 acres of land is needed for generating 1 MW of Agri-PV power, the total potential from agricultural lands alone is estimated at 629.69 GW. For fallow and other uncultivated lands, the potential reaches 117.74 GW. Although these estimates indicate substantial potential, the Government may opt for a more gradual approach. A reasonable initial target could be between 20 and 30 MW in the first year, with a planned increase over the subsequent years [65]. To align with this, a target of around 15 GW of Agri-PV capacity over the next decade is proposed, following the suggested growth trajectory illustrated in the accompanying figure. Nearly half of the Agri-PV plants in India are located in Gujarat, which is recognized as the first state to explore Agri-PV on a large scale [65]. Figure 11 represents the location of Agri-PV plants in India as of 2024. One of the earliest documented Agri-PV pilot sites in this state was commissioned by Abellon Energy in 2012. Alongside Abellon, Jain Irrigation Systems Limited (JISL) from Maharashtra is also credited with being a trailblazer in the field, having initiated its first pilot projects in 2012 as well, and incorporating crop cultivation beneath solar structures [65]. Since these early developments, India’s Agri-PV sector has expanded, with contributions from various stakeholders. Currently, three types of Agri-PV projects are operational in India: research and development (R&D) projects, government-supported initiatives, and commercial projects led by private entities [65].

Figure 11.

Maximum Agri-PV potential of India based on [61] and location of Agri-PV plants in India based on [68].

3.1.9. Japan

Japan has made notable strides in Agri-PV, starting with early development in Chiba Prefecture in 2004. Currently, there are 1992 Agri-PV farms across the country, covering about 560 hectares, though most are small-scale, under 0.1 hectare. These systems collectively generate between 500,000 and 600,000 MWh annually, contributing roughly 0.8% of Japan’s PV electricity output as of 2019 [31,69,70]. Doedt et al. [71] While, mentioned that Japan has over twenty years of experience in Agri-PV and had 3474 permitted projects by 2020. By May 2018, out of 755 established Agri-PV farms, 65% (490 farms) were under 0.1 hectare, followed by 24% (178 farms) ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 hectares, 4% (27 farms) from 0.3 to 0.5 hectares, 5% (34 farms) from 0.5 to 1 hectare, and 3% (26 farms) exceeding 1 hectare. This trend reflects the generally small size of farms in Japan, where 52% of the 1,188,800 agricultural management entities operate on less than 1 hectare. The remaining farm sizes include 38% (457,400 farms) between 1 and 5 hectares, 4% (49,800 farms) between 5 and 10 hectares, 1% (11,500 farms) between 10 and 20 hectares, and 2% (18,800 farms) over 30 hectares.

Doedt et al. [32] on Agri-PV provide a detailed analysis of the regulatory and policy landscape in Japan. Agri-PV in Japan benefits from a supportive regulatory framework established by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). A 2013 directive allowed Agri-PV systems on all farmland categories, subject to conditions such as temporary mounting structures and ensuring minimal impact on agricultural productivity. Subsequent directives in 2018 and 2021 introduced provisions for longer permits and exceptions for devastated farmland, with the latest directive removing height requirements and certain land-use conversion rules for specific cases. For large-scale solar projects, including Agri-PV, an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is required if the capacity exceeds 30–40 MW, following an amendment to the EIA Act in April 2020. Although current Agri-PV projects are generally smaller, local ordinances may impose stricter regulations. Agri-PV systems are exempt from the Building Standard Act as long as they meet temporary land-use conversion criteria.

The Feed-In-Tariff (FIT) Act, introduced in 2012, has been instrumental in supporting Agri-PV by guaranteeing stable income for 20 years. The 2022 amendment offers preferential treatment for small-scale systems, with exemptions for certain regional electricity distribution requirements if the systems hold long-term land-use permits. Recent national policies, including the Basic Energy Plan and the Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture, and Rural Areas, highlight Agri-PV as key to achieving energy transition and sustainable agriculture goals. The Green Growth Strategy for 2050 further underscores Agri-PV as a tool for rural decarbonization. The integration of Agri-PV into national and local policies reflects a growing recognition of its potential. However, effective implementation also requires supportive measures at the prefectural and local levels, including subsidies for necessary equipment. This horizontal and vertical policy integration is crucial for the expansion and success of Agri-PV in Japan.

4. Agri-PV Design/Modeling Technique

4.1. Agri-PV Typology/Classification

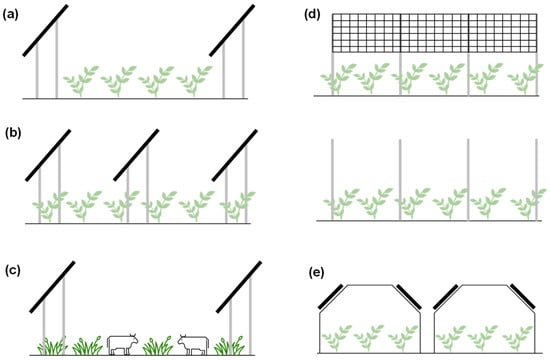

Designing Agri PV is complex, requiring joint expertise from farmers and PV developers and a standardized design format to address technology, construction, safety, and economics. Key tasks are matching crops and PV technology to site conditions, modeling shading on crops and between modules, and using sustainable mounting solutions typically aluminum frames while minimizing several impacts on fields. Designs must also withstand snow and wind loads and account for variable soil conditions and textures (moist, wet, or dry), where solid bases may not always be feasible. In Germany, the German Institute for Standardization has developed influential guidelines for similar climatic conditions, which include maintaining agricultural usability of the area, ensuring land loss does not exceed 10% for panels above 2.1 meters and15% for panels below 2.1 meters, providing adequate solar radiation and water, preventing soil erosion, and achieving an agricultural yield of at least 66% compared to the reference yield based on the past three years’ average data. Standard Agri-PV setups, as illustrated in Figure 12, generally include various configurations based on literature reviews, such as crops grown between PV rows, grazing areas between and underneath panels, vertically mounted solar panels, crops grown between and beneath panels, and greenhouse-integrated solar systems.

Figure 12.

Agri-PV installation typology. (a) Crops Grown Between PV Rows, (b) Crops Grown Between and Underneath PV Panels (c) Grazing Areas Between and Beneath PV Panels (d) Vertically Mounted Agri-PV and (e) Greenhouse-Integrated Agri-PV Systems. Own illustration based on [72,73,74].

In crops grown between PV setups, crops are cultivated in the spaces between rows of solar panels. The panels are usually elevated to ensure solar radiation reaches the crops in between. This configuration aims to strike a balance between power generation and crop yield, as the spaced-out PV rows allow for sufficient PAR exposure, supporting healthy crop growth. Hickey et al. [75] illustrated the example of fruits/vegetables grown between PV rows. While crops grown between and underneath PV design involve cultivating crops both between and underneath the solar panels. By providing partial shade, this configuration can be suitable for crops that benefit from moderated solar radiation, including situations where high irradiance levels could otherwise induce plant stress—whether due to high temperature or simply high light intensity. This setup maximizes land use but requires careful crop selection to ensure compatibility with the shading [76]. In grazing areas between and beneath PV panels configuration allocates grazing areas for livestock, such as sheep, between and under the solar panels. The animals graze on the vegetation growing in these spaces, naturally controlling plant growth and reducing the need for manual maintenance. This setup supports dual land use by integrating small-scale vegetation or grass, which complements the solar installations without interfering with power generation [77]. In vertically mounted Agri-PV system arrangement, solar panels are mounted vertically, allowing solar radiation to reach crops on both sides of the panels. This setup is effective in regions where vertical alignment can capture adequate solar radiation, and it minimizes shading on crops. While vertical installations may produce slightly less energy, this configuration enables simultaneous agricultural use of the land with minimal impact on crop solar radiation exposure [78,79]. In greenhouse-integrated Agri-PV configuration, solar panels are integrated into greenhouse structures, providing a controlled environment for year-round crop production while sheltering the PV modules. Semi-transparent panels are often used to ensure plants receive adequate solar radiation. This design allows for optimized control of PAR, temperature, and humidity, benefiting both crop growth and energy production [80,81].

4.2. Basic Equations for Agri-PV Modeling

Modeling approaches in Agri-PV systems vary widely depending on the specific aspects being studied, such as system design, technical and economic feasibility, irradiance and shading losses, and layout optimization. Some software packages offer comprehensive toolsets for multiple tasks, while others focus on specific technical details. Agri-PV modeling typically uses equations to assess the balance between PV energy production and agricultural productivity across different system configurations. This section provides an overview of the equations commonly used in Agri-PV modeling, as discussed in existing literature [82]. To assess the overall productivity of Agri-PV systems, Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) is commonly used factor [83]. LER is used to assess the overall productivity of Agri-PV systems compared to traditional agriculture or PV systems alone [33].

where

is the crop yield under the Agri-PV system,

is the crop yield in a conventional agriculture-only system,

is the electrical yield under the Agri-PV system,

is the electricity generated if the land were solely dedicated to PV panels.

An LER greater than 1 indicates that the Agri-PV design is more efficient than producing only energy or only crops from the land. Conversely, an LER less than 1 suggests that energy–food production is less productive than single-purpose production. Additionally, potential land losses should be considered in the analysis, as in some installations the area directly beneath the PV structure is not used for cultivation, although in other systems it remains in productive use (e.g., grazing or shade-tolerant crops) [84]. To calculate the electricity generated by PV panels, the following equation is suggested by Okhotkin et al. [85]. However, this equation does not provide any information about crops or the impact of Agri-PV on agricultural production. It is solely focused on energy generation through solar panels.

is the electricity output from the PV panels in watts,

is solar radiation intercepted by the PV panels in W/m2,

is the surface area of the PV panels in m2,

ηPV is the efficiency of the PV modules, which converts the intercepted solar energy into electrical energy.

When considering the effect of irradiation on crops, Mehta et al. [17] noted that crops utilize only a portion of the solar spectrum, specifically the PAR, which ranges from 400 to 700 nm.

This equation helps estimate the amount of usable radiation for crop growth:

where

is the amount of photosynthetically active radiation reaching the crops,

is the solar radiation intercepted by the crops in W/m2,

is the fraction of total solar radiation that is usable for photosynthesis, generally assumed to be 0.5.

This equation is crucial for understanding how shading affects crop growth, as only PAR contributes to photosynthesis. Equations in Agri-PV modeling are often imprecise due to simplified assumptions, like uniform radiation, constant crop growth, and fixed efficiencies. As a result, researchers are turning to more advanced tools and software for more accurate analysis [86]. In reality, these factors fluctuate over time and across environments, making simple equations less reliable for complex, dynamic systems [87]. For example, shading from PV panels affects crops based on factors like time of day, season, weather, and crop type, all of which vary and are hard to capture with static equations. Agri-PV systems also involve complex interactions between solar radiation, crop growth, PV panel performance, microclimates, and soil conditions [17,33]. Modeling these interactions with equations alone is difficult because they require continuous, detailed data that cannot be captured in simple formulas. Additionally, equations often overlook non-linear interactions, feedback loops (like how shading impacts soil moisture and crop health), and spatial variations (such as uneven shading across a field due to panel layout) [88,89]. The following section offers a comprehensive comparative overview of the tools currently used in Agri-PV modeling.

4.3. Software Used for Agri-PV Modeling

Theoretical analysis of Agri-PV systems requires specialized tools to predict performance before real-world application. Given the integration of agriculture with PV energy generation, either a combined tool or separate tools for each aspect are essential. These tools enable accurate simulations of crop growth and energy production interactions, supporting evaluations of system viability and efficiency. Although various tools exist for modeling crop yield under different conditions, a comprehensive tool that fully analyzes Agri-PV performance, including crop suitability, is still lacking [42].

Table 2 and Table 3 present a comprehensive overview of the main software and tools used for Agri-PV system modeling and design in current research. AGRIPV TOOL (https://iiw.kuleuven.be/apps/agrivoltaics/tool.html (accessed on 30 September 2025)) [90] is developed by KU Leuven University as part of the Horizon 2020-funded HyPErFarm project, this Agri-PV tool is designed to evaluate system configurations by balancing both energy production and agricultural yield. The tool requires input parameters such as location, system structure (e.g., panel height and tilt angle), and crop specifications regarding shade tolerance. Using these inputs, it provides detailed outputs including installed power, energy yield, relative crop yield, and the levelized cost of electricity (LCoE), among other performance metrics, allowing for an optimized analysis of Agri-PV setups that accommodate both PV energy generation and crop productivity. SPADE (Solar Panel Agrivoltaic Design and Evaluation) is developed by SANDBOX Solar (https://sandboxsolar.com/services/agrivoltaics-modeling/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)) [91], is a comprehensive tool for designing and modeling Agri-PV systems. It allows users to select a geographic location and tailor performance analysis based on local solar radiation and climate conditions. The SPADE (https://spadesolar.com/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)) and nanoHUB (https://nanohub.org/resources/agpvsim (accessed on 30 September 2025)) Agri-PV Simulation tools enable users to design and optimize Agri-PV systems by adjusting parameters such as panel height, tilt, spacing, and layout to balance crop growth and energy generation. SPADE focuses on optimizing PAR distribution for sustainable system performance, while nanoHUB, developed by Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN, USA), offers flexible simulation modes for both general and customized farm designs. By integrating PV system specifications, site location, and climatic conditions, these tools generate key outputs such as irradiance distribution and power density, supporting data-driven decisions for efficient and productive Agri-PV configurations.

Table 2.

Software used in Agri-PV modeling based on the literature review.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of software used in Agri-PV modeling where ✓ indicates that the study addresses the respective topic.

5. Crop Suitability with Agri-PV

Crop suitability is crucial in Agri-PV systems, as different crops have specific needs for solar radiation in terms of wavelength and intensity to thrive and maximize yield. The shading effect from PV panels can modify the light environment, either hindering or benefiting crop productivity depending on the species. Research has shown that some crops adapt well to partial shading, benefiting from reduced heat stress and water loss, while others require full solar radiation for optimal growth [111,112]. In recent years, extensive research has been conducted to assess the compatibility of Agri-PV systems with various crop types, taking into account factors such as regional climate, crop-specific PAR needs, and the spatial configuration of PV panels [113,114]. The growing body of literature highlights how strategic crop-PV combinations can optimize land use, balancing energy and food production. This section summarizes global studies, offering an overview of crop compatibility within Agri-PV systems and outlining best practices for integrating PV technology with agriculture to enhance sustainability and productivity.

To avoid shading issues with Agri-PV installation, several design strategies are employed, such as Agri-PV with full density and Agri-PV with half density [115]. In the full-density design, PV panels are installed closely together to maximize energy production, potentially providing more shading for crops. However, this can limit crop growth if the shading is too intense for crops that require high solar radiation [24]. The half-density design places the panels further apart, allowing more solar radiation to reach the crops and reducing shading, but it may generate less energy compared to the full-density design. These configurations seek to balance the trade-off between energy production and crop yield, optimizing the system’s overall effectiveness [22]. Other design variations may also include adjusting the height and tilt angle of panels to optimize both solar irradiance and crop health, depending on the specific agricultural and environmental conditions [17]. Table 4 offers an overview of different crop types and how they integrate with Agri-PV systems, with a focus on crop yield. Yield variations are influenced by factors like location, weather, and season, which can significantly impact the performance of the Agri-PV system.

Table 4.

Crop suitability with Agri-PV with key crop types where ↓ represents decreasing yield,  represents moderate/stable impact on yield and ↑ represents the increased yield with Athe gri-PV system based on the real-life examples.

represents moderate/stable impact on yield and ↑ represents the increased yield with Athe gri-PV system based on the real-life examples.

represents moderate/stable impact on yield and ↑ represents the increased yield with Athe gri-PV system based on the real-life examples.

represents moderate/stable impact on yield and ↑ represents the increased yield with Athe gri-PV system based on the real-life examples.

For detailed analysis, Mehta and Zörner [152] conducted an international review to identify the key parameters influencing crop selection in Agri-PV systems. The study systematically analyzed global literature on crop–solar coexistence, focusing on how shading intensity, panel geometry, radiation distribution, and local climatic conditions affect plant growth and yield. The authors compiled experimental data on crop responses to partial shading for major crop categories—including cereals, vegetables, legumes, and forage species—and assessed their compatibility with different Agri-PV configurations. Building on this synthesis, the paper developed a strategic decision-making model that links agronomic variables (such as shade tolerance, photosynthetic efficiency, and water demand) with system design factors (such as panel tilt, height, and ground coverage ratio). The model provides a structured method for ranking and selecting crops suited to site-specific Agri-PV conditions, offering guidance for planners and farmers when designing dual-use systems. The authors emphasize that the framework serves as a practical tool for pre-feasibility assessment, enabling the alignment of agricultural productivity goals with renewable energy generation potential.

6. Policy and Economic Aspects of Agri-PV Worldwide

6.1. Economics of Agri-PV

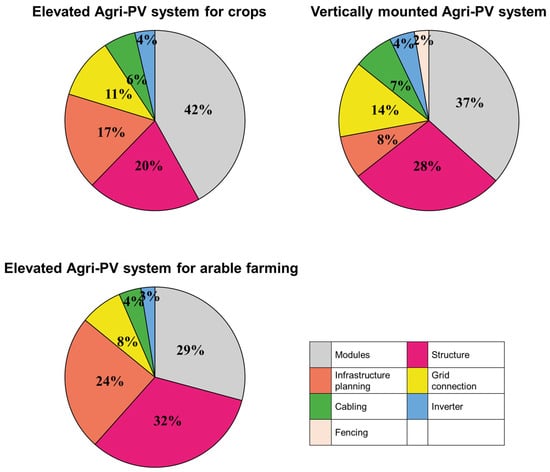

Recent studies have increasingly emphasized the economic dimension of Agri-PV, underscoring that long-term viability depends not only on technical optimization but also on cost competitiveness and revenue diversification. Drawing on a synthesis of global case data, Mehta et al. [153] highlight that investment costs constitute the largest share of total system expenditure—typically 29–42%, with elevated and crop-specific designs being the most capital-intensive. The reported Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) values for Agri-PV systems range between €0.07 and €0.12/kWh in Europe, €0.09/kWh in Niger [154], and approximately €0.10/kWh–€0.20/kWh Asia [155,156], placing Agri-PV within the same economic range as conventional PV when agricultural co-benefits are considered.

Empirical evidence from pilot projects in Botswana [144], Bangladesh [157], and Canada [158] demonstrates that Agri-PV can achieve payback periods of 3–4 years and returns on investment (ROI) of 16–43%, particularly where integrated land use, such as sheep grazing or high-value crop cultivation, is applied. These findings reinforce the potential of Agri-PV to enhance farm income stability while delivering renewable energy and ecosystem services. Moreover, the study confirms that Agri-PV capital costs follow a 20% learning curve, implying substantial cost reductions as cumulative global capacity doubles. Overall, the economic outlook for Agri-PV suggests a transition from an experimental to an investable technology class. Declining module prices, standardized mounting designs, and policy-driven incentives such as feed-in tariffs, dual-use subsidies, and carbon credits are expected to improve financial feasibility further. Integrating these economic insights into Agri-PV planning frameworks is therefore essential to support evidence-based policymaking, promote rural energy transitions, and ensure that the dual benefits of energy and agriculture are captured within national sustainability strategies. Figure 13 represents the cost breakdown of the various Agri-PV system based on the literature review.

Figure 13.

Cost distribution of different Agri-PV installation types based on [153].

6.2. Global Policy Landscape for Agri-PV: Status Quo and Rationale

The rapid global expansion of PV energy has intensified competition for arable land, making clear and coordinated Agri-PV policy frameworks increasingly vital. Effective policy intervention is essential to balance renewable energy goals with food security, rural development, and environmental protection. Without defined regulations, Agri-PV deployment risks becoming fragmented, hindered by unclear land-use classifications, inconsistent permitting procedures, and limited financial incentives for farmers [159]. Therefore, national and regional policies play a decisive role in translating pilot projects into scalable and commercially viable systems. Globally, Agri-PV policy adoption remains uneven. Countries such as Germany, France, Japan, and China have developed formal frameworks that define agricultural usability, establish feed-in tariffs or auction schemes, and integrate Agri-PV within national renewable energy strategies [160]. Germany’s DIN-SPEC 91434, published in 2021, and the Renewable Energy Act explicitly recognize dual-use agriculture, while France’s Agri-PV tenders have supported over 200 MW of installed capacity. Japan, through the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries directive and the Feed-in Tariff program, now hosts nearly 2000 Agri-PV farms producing up to 600 GWh annually, demonstrating policy coherence between energy and agricultural sectors. China has embedded Agri-PV within its large-scale renewable and poverty-alleviation programs, resulting in more than 64 GW of Agri-PV capacity, by far the world’s largest.

In contrast, emerging markets such as India, South Korea, and the United Kingdom remain at exploratory or pilot stages, with fragmented regulatory frameworks and limited economic incentives. Italy and Austria are developing national guidelines under their recovery and resilience programs, while the United States shows strong sub-national activity, particularly in Massachusetts, but lacks a unified federal policy. Across these regions, recurring challenges include high upfront capital costs, complex permitting procedures, and the absence of standardized definitions for agricultural co-use.

Synthesizing global best practices indicates that successful Agri-PV policies share four core characteristics: clear definitions and technical standards for agricultural productivity thresholds; targeted financial incentives such as feed-in tariffs, tenders, or tax relief; cross-sectoral coordination between energy, environment, and agriculture ministries; and the use of spatial planning tools such as GIS-based zoning to optimize land allocation. Countries that have adopted these elements, notably Germany, France, and Japan, demonstrate higher deployment rates and stronger farmer participation. Moving forward, a harmonized global policy approach anchored in land-use efficiency, climate resilience, and rural socio-economic benefits will be essential to scale Agri-PV from demonstration projects to mainstream agricultural infrastructure. Table 5 represents the overview of Agri-PV policy in different countries while Table 6 descibes enabling policy conditions and barriers idnetified from the literatur review.

Table 5.

Overview of Agri-PV Policy on global landscape.

Table 6.

Synthesizes the key enabling policy conditions and barriers identified across the global Agri-PV literature reviewed.

7. Discussion and Future Perspectives

The global review highlights that Agri-PV has emerged as a transformative approach for integrating renewable energy generation with agricultural production, aligning with the goals of climate resilience, food security, and sustainable land management. Evidence from global case studies demonstrates that well-designed Agri-PV systems can simultaneously enhance land-use efficiency and diversify rural income sources while maintaining acceptable agricultural productivity. Average crop yield reductions of 7 to 10 percent are offset by gains in PV output of around 10 to 15 percent under optimized configurations, underscoring the potential for co-beneficial performance when system design aligns with crop physiology requirements and local climate. Moreover, microclimatic benefits such as reduced evapotranspiration, improved soil moisture retention, and lower crop stress further reinforce Agri-PV’s adaptive value in water-scarce regions.

Despite these advantages, the current landscape reveals considerable heterogeneity in research focus, scale, and regional adoption. Most Agri-PV studies remain site-specific or pilot-scale, with limited integration across engineering, agronomy, and economic dimensions. The lack of harmonized performance metrics and standardized assessment methods constrains comparability across studies and hinders replication in diverse agro-climatic zones. Moreover, no comprehensive model currently integrates the dynamic interactions among energy generation, crop growth, and water use, indicating a pressing need for multi-objective modeling frameworks. Developing such integrated models will be essential for quantifying trade-offs, optimizing design parameters, and ensuring that energy generation complements rather than competes with agricultural productivity.

Economically, Agri-PV systems continue to face higher upfront investment costs compared to ground-mounted PV, largely due to elevated structures and crop-compatible mounting systems. However, learning curve effects and growing standardization are expected to reduce costs significantly in the coming decade. Economic viability improves further when co-benefits—such as water savings, biodiversity gains, and carbon reduction—are incorporated into valuation frameworks. From a policy perspective, countries with well-defined regulatory frameworks, such as Germany, France, Japan, and China, demonstrate that clear definitions, performance-based incentives, and cross-sectoral coordination can accelerate deployment and farmer participation. Conversely, the absence of targeted policy instruments in developing economies limits large-scale implementation despite favorable solar and agricultural potential.

Across this review, the five analytical strands assessed here, global technical potential, modeling approaches, crop suitability evidence, policy/economic mechanisms, and implementation governance are structurally interconnected rather than independent. Evidence suggests that harmonized performance reporting and standardized modeling assumptions are foundational prerequisites for economically credible crop–PV pairing at scale; likewise, techno-economic viability cannot be robustly determined without transparent definition of agricultural performance thresholds. Accordingly, the emerging global consensus is converging around five priority areas for the next research cycle: (i) methodological harmonization and metadata standards, (ii) reproducible modeling assumptions and open datasets, (iii) crop–PV matching frameworks anchored in agro-ecological specificity, (iv) valuation of agricultural and ecosystem co-benefits, and (v) governance architectures that correctly internalize these co-benefits within investment and policy instruments. While global food insecurity is rarely caused by insufficient total production, Agri-PV remains relevant as a strategy to enhance climate resilience and optimize land use without reducing agricultural output.

For future research, Agri-PV must be recognized as a genuinely interdisciplinary system operating at the Energy–Agriculture nexus, requiring collaboration among engineers, agronomists, economists, and policymakers. Future research should focus on integrating techno-economic, agronomic, and environmental dimensions within unified simulation and life-cycle assessment tools. Expanding empirical evidence through long-term field trials in tropical and arid regions will help refine models and validate system performance under real-world conditions. At the policy level, establishing global standards for Agri-PV classification, land-use criteria, and agricultural performance thresholds will be vital for scaling deployment. Ultimately, Agri-PV offers a strategic pathway toward sustainable land-use intensification—one that balances food and energy production while advancing the global transition toward climate-resilient, low-carbon rural economies. Furthermore, intelligent technologies including artificial intelligence, digital twins, and IoT-based monitoring are expected to accelerate interdisciplinary integration and real-time optimization in Agri-PV systems. These tools will enable predictive modeling, adaptive management of energy-crop-water interactions, and continuous improvement in operational efficiency, signaling a new era of “smart” agrivoltaics that aligns with emerging priorities for climate resilience and sustainable rural development.

8. Conclusions

This review provides a comprehensive global synthesis of the technological, agronomic, economic, and policy dimensions of Agri-PV systems, emphasizing their growing significance at the intersection of renewable energy generation and sustainable agriculture. The findings confirm that Agri-PV enables dual land use by combining food and energy production, improving land productivity and resource efficiency. Empirical evidence indicates that while average crop yields decrease modestly by 7 to 10 percent, optimized Agri-PV configurations can increase PV energy output by 10 to 15 percent, contributing to both energy transition goals and agricultural resilience. Despite this promise, large-scale Agri-PV deployment remains geographically concentrated, with Europe and Asia leading implementation through supportive policy frameworks such as Germany’s Renewable Energy Act, France’s national tenders, and Japan’s MAFF directives.

In contrast, emerging economies with high solar potential often lack clear regulatory definitions, financial incentives, or technical standards, resulting in limited adoption. Addressing these institutional and financial barriers will be critical for achieving equitable global diffusion. Strengthening collaboration between agricultural and energy sectors will be essential to operationalise the Energy–Agriculture nexus, and future policy frameworks should incorporate carbon accounting, ecosystem services, and co-benefit valuation to capture the full societal value of Agri-PV.

The review also identifies an urgent need for integrated energy, water, and crop modeling, standardized performance metrics, and comprehensive techno-economic and environmental assessments to guide evidence-based system design. Strengthening collaboration between agricultural and energy sectors will be essential to operationalize the Energy–Agriculture nexus and promote sustainable dual land use. Future policy frameworks should incorporate carbon accounting, ecosystem services, and co-benefit valuation to capture the full societal value of Agri-PV.

Ultimately, Agri-PV represents more than a technological innovation; it is a systemic solution that aligns renewable energy expansion with agricultural sustainability, rural development, and climate adaptation. Its successful integration into national energy and agricultural strategies could redefine global land-use paradigms, supporting the transition toward resilient, low-carbon, and resource-efficient food and energy systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and W.Z.; methodology, K.M.; software, K.M.; validation, K.M., W.Z. and R.J.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, K.M. and R.J.; resources, W.Z.; data curation, K.M. and R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and R.J.; visualization, K.M.; supervision, W.Z.; project administration, W.Z.; funding acquisition, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work was funded by the Bavarian State Chancellery under the project “Dig-e-Farm—Digitalisation of Tunisian farms through AI-based Agri-PV energy systems for optimal management of the water–energy nexus” (Project ID C I 4-1162-106-254-1). Also, it was supported by the DAAD funded project Renewable Energy Action: A Sustainable water-energy nexus Partnership for Higher Education in Central Asia (RE.Act) (Project ID: 57703798).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest