1. Introduction

The transition to a sustainable energy system is one of the most urgent challenges facing society today. Although renewables have driven much of the recent growth in global energy supply, fossil fuels still dominate [

1]. This underscores the necessity for continued technological innovation to ensure renewable resources are available when and where required. Political initiatives admit both the ambition and complexity of moving toward carbon neutrality. Intersectoral energy use demands advanced solutions that couple electricity with heating and cooling. In sectors such as aviation and shipping, where direct electrification is technically challenging, decarbonization will rely on the development and deployment of renewable fuels, including clean hydrogen and its alternatives. Achieving energy efficiency and facilitating sector coupling are therefore central to a successful transition. Importantly, addressing the technological complexity of advanced energy systems fosters specialized expertise and technical competence, which in turn strengthens competitiveness and innovation capacity [

2,

3].

Solid oxide cells (SOCs), functioning either as fuel cells (SOFCs) or electrolysis cells (SOECs), are among the most promising technologies for meeting the diverse demands of a sustainable energy system. Based on oxygen-ion-conducting ceramic electrolytes, SOFCs and SOECs operate at high temperatures, enabling efficient integration of electricity and heat supply in both industrial and residential settings. Their fuel flexibility further supports the shift from fossil to renewable energy, as they can operate on hydrogen, carbon-based fuels, or ammonia [

4]. SOFCs offer several advantages over other energy converters: high energy conversion efficiency (enhanced by the use of waste heat), high power output, low acoustic emissions, and minimal environmental impact under renewable operation—making them particularly suited for stationary energy generation [

5]. SOECs share these benefits, delivering high efficiency by exploiting industrial waste heat and offering superiority over competing options for hydrogen production. Consequently, their integration into future energy systems will be essential for ensuring efficient, reliable use of intermittent renewable resources. Their applicability in renewable ammonia synthesis and in co-electrolysis of steam and CO

2 to syngas further demonstrates their versatility. Such integration of renewable energy generation with chemical industry processes promotes further sector coupling. Another advantage is offered by reversible solid oxide cells (rSOCs), which combine hydrogen and electricity production in a single system, helping to lower the cost of the energy transition [

6].

An emerging technology variant is the use of proton-conducting ceramic electrolyte cells (PCCs), which has attracted increasing research interest in recent years. Incorporation of PCCs allows proton-conducting ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) and electrolysis cells (PCECs) to operate at 400–650 °C rather than the conventional 700–900 °C. Operating at lower temperatures reduces material requirements and wear, while in electrolysis, it enables the production of pure hydrogen, eliminating the need for purification equipment. Overall, these factors contribute to reduced costs and broader applicability. However, large-scale adoption of proton-conducting ceramic cells is still hindered by manufacturing challenges, primarily the chemical instability of the electrolyte material [

7,

8].

Despite their versatility and advantages over other technologies, SOCs still face barriers. In addition to high operating temperatures, these include the complexity of multi-step production chains and the scalability of performance-enhancing modifications. These constraints form the core of the performance optimization problem in SOC design that we focus on in our review: minimizing operating temperature while ensuring sufficient electrochemical performance and robustness.

While the development of new materials offers significant opportunities, cell architecture and component design are equally critical to achieving cost-effective and high-performance systems.

The cell design consists of a multilayer structure incorporating ceramic or metal-ceramic components. At its center is a ceramic electrolyte, which facilitates the movement of ions and separates the cell into two compartments: one for fuel and one for oxygen/air supply and removal. The most common material for oxygen ion-conducting cells is yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ). Durability depends on the structural stability of the materials under thermal cycles during fabrication and operation. At high temperatures, detrimental material phases may form between components, necessitating strict control of thermal expansion compatibility and chemical stability. A common mitigation strategy is to insert a barrier layer, mostly gadolinium-doped ceria (GDC), between the electrolyte and the electrodes to prevent adverse chemical interactions. Equally important is the maximization of the active cell area at the electrolyte-electrode interfaces [

6].

Further design considerations apply to the individual cell components. For the ceramic electrolyte, complete densification is essential. Since ion conductivity is thermally activated, reduced layer thickness and optimized electrolyte/barrier layer structures are required to minimize cell resistance and lower operating temperature [

5].

Conversely, electrode layers must be porous to ensure efficient reactant supply and removal. At the electrode–electrolyte interface, the microstructure must balance ion-conducting and electron-conducting phases with suitable porosity to maximize the triple-phase boundary (TPB). Accordingly, a functional interlayer is frequently employed between the outer electrode component and the electrolyte [

9,

10]. Oxygen electrodes typically consist of lanthanum manganite-, cobaltite-, and ferrite-based perovskites, including Ruddlesden–Popper phases, many of which act as mixed ionic-electronic conductors (MIEC), serving to increase TPB length. Fuel electrodes are most commonly nickel and yttrium stabilized zirconia (Ni-YSZ) composites, though Ni-fluorite ceramics and perovskites are also used. When alternative fuels are internally reformed, or syngas is produced by co-electrolysis, stricter requirements for chemical stability apply for fuel electrodes [

5,

6].

Overall, these aspects of cell design offer a wide range of optimization opportunities across different components and properties. However, implementing these enhancements requires understanding not only the desirable attributes but also the manufacturing methods by which they can be realized, underscoring a strong connection between design and fabrication.

The literature already contains a wide range of SOC design reviews. As this review focuses on the flat cell design, an overview of geometric variants—including planar, flat-tube, tubular, and cone-shaped designs—is available in [

11], together with their respective advantages and disadvantages. Structural property modifications within individual cell components are also summarized. Challenges specific to electrolysis, including co-electrolysis and rSOC, as well as common fabrication techniques, are reported in [

12]. A comprehensive evaluation of the potential of oxygen-ion- and proton-conducting cells, for both fuel cell and electrolysis modes, is also provided, along with selected options for component-level design improvements. An overview of manufacturing methods and materials can be found in [

10].

With respect to SOC manufacturing, ref. [

9] provides a general overview of available materials and fabrication techniques, including an initial evaluation of their applicability and limitations. Conventional ceramic processes and the specific challenges of planar SOFC fabrication are discussed in ref. [

13], while ref. [

14] considers alternative fabrication options for lowering operating temperature, noting the pros and cons of each. For proton-conducting solid oxide cells, which are not yet scalable and manufacturable, ref. [

15] outlines possible manufacturing approaches and associated challenges. Design and material-related issues in PCC electrolytes and electrodes are discussed in ref. [

16], though without direct connection to manufacturing strategies.

Materials development itself is beyond the scope of this review. For an in-depth coverage of this area, readers may consult refs. [

17,

18] for fuel cell operation and refs. [

19,

20] for electrolysis.

A literature survey of SOFC optimization strategies is presented in ref. [

21], covering material compositions, cell geometries, and their relation to efficiency, performance density, and cost. From this work, a set of optimization tools was derived, ranging from mathematical modeling and simulation to algorithmic approaches.

This review delivers a comprehensive overview of distinct optimization approaches and manufacturing, considering them with respect to their distinct characteristics and implications for scalable SOC production. Manufacturing methods play a decisive role in determining cell architecture and properties. Accordingly, this review establishes their correlation with design improvements. To address the breadth of the available literature, a PRISMA-ScR-based methodology was employed, ensuring systematic identification and categorization of relevant studies. By distinguishing optimization strategies from manufacturing methods, the reviews aim to provide clarity and to facilitate the derivation of new concepts for SOC design and manufacturing.

The following research questions were formulated to guide the identification and reporting of these aspects:

Which design approaches can be used to improve solid oxide cells?

Which manufacturing methods are suitable for implementing these approaches?

To what extent does the applied method fit in terms of design optimizations with the aspects of costs, scalability, and process control?

The subsequent discussion evaluates established developments reported in the literature with respect to their applicability to future SOC production chains, while also addressing emerging approaches and alternative manufacturing processes for optimized design.

3. Results

In this section, we first present the quantitative outcomes of the literature search, including the reasons and stages at which studies were excluded. Subsequent subsections address the first two research questions by presenting manufacturing methods and design optimization strategies identified in the literature.

3.1. Search Results

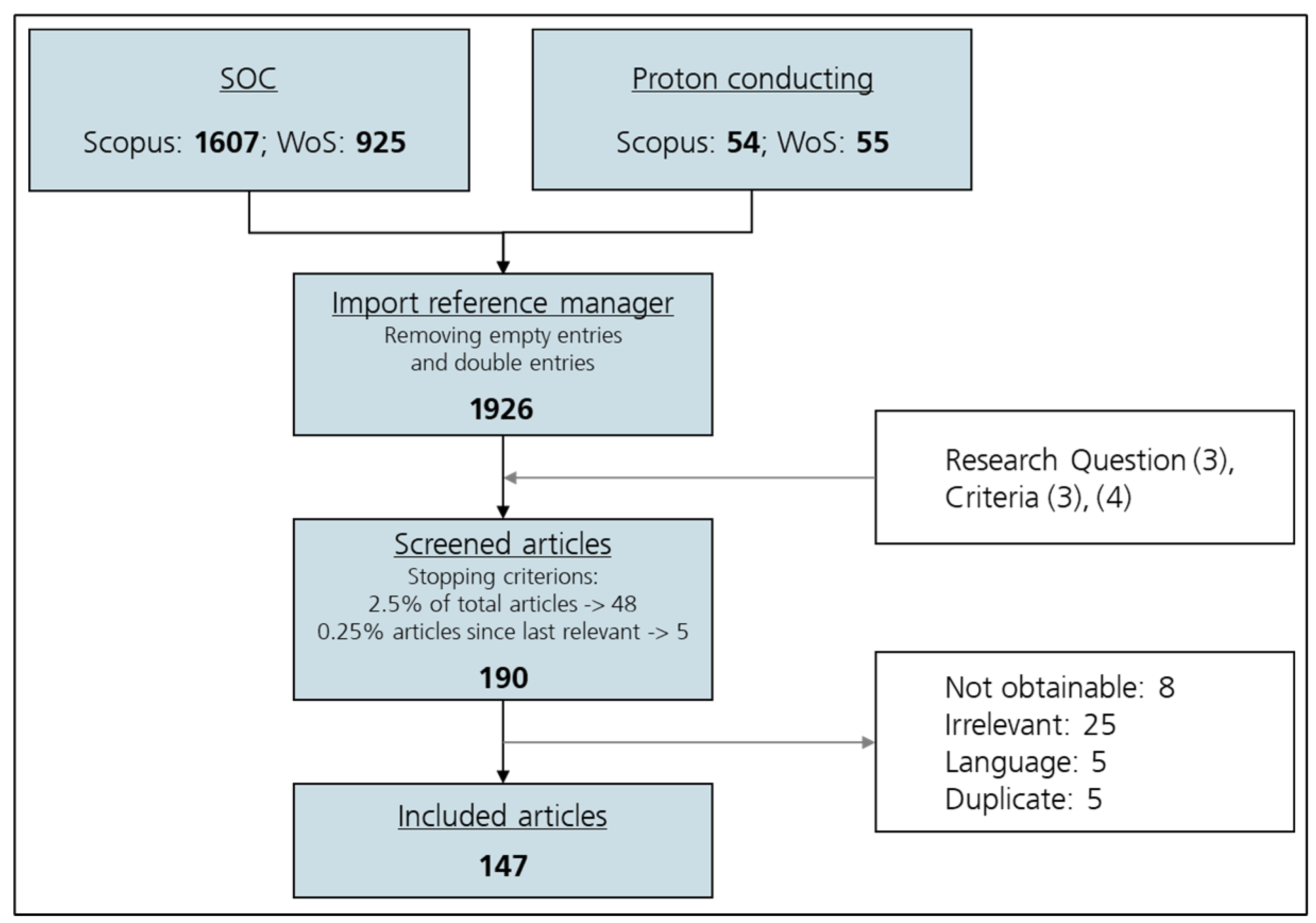

Scopus and Web of Science searches were combined using a reference manager. After removal of non-article records and duplicates, just under 2000 items remained. Titles and abstracts were screened for alignment with the predefined scope (fabrication and optimization of SOC components), and only those clearly relevant advanced to full-text review.

At the full-text stage, exclusions occurred for four reasons: (i) article unavailable, (ii) content outside the review scope, (iii) language not meeting inclusion criteria, or (iv) residual duplication. This stepwise process yielded a final evidence base of 147 studies from an initial pool of nearly 2000. All criteria applied during the screening process are depicted in

Table 3.

The workflow is depicted in

Figure 1, tracing the two search streams through de-duplication, sequential screening, and the application of exclusion criteria. The arrows and boxes in the diagram indicate decision points and the progression of records between stages.

Numerical evaluation of the 147 selected studies highlights several focal areas of SOC research. Most studies addressed electrolyte optimization, followed by work on electrode functional layers. Some examined multiple components simultaneously, while very few considered optimization of entire cells using a single manufacturing method.

Five primary optimization objectives were identified. The largest share of studies focused on reducing operating temperature. Others emphasized lowering manufacturing temperatures, particularly sintering, to prevent adverse chemical interactions between component materials. Additional objectives included improving robustness under demanding operating conditions, enhancing electrochemical performance, and simplifying the multi-step SOCs production chain. Several studies pursued multiple objectives simultaneously.

With respect to operating modes, most studies focused on fuel cells with an oxide-ion-conducting electrolyte (SOFCs). Only a single study addressed oxide-ion-conducting electrolysis cells (SOECs). Several publications examined oxide-ion-conducting solid oxide cells more generally, reporting optimizations applicable to both operating modes (SOCs). For proton-conducting electrolytes, five studies investigated fuel cells (PCFCs), while none addressed electrolysis (PCECs) or optimizations valid across both operating modes (PCCs).

Table 4 provides the exact breakdown by component, governing primary optimization objective, and cell operating mode.

Most studies addressed electrolyte optimization, followed by work on electrode functional layers. Some examined multiple components simultaneously, while very few considered optimization of entire cells using a single manufacturing method.

3.2. Applied Fabrication Methods

The final collection of studies yielded a variety of fabrication methods, which are summarized in this section. Their application to specific optimization strategies was motivated by different considerations. In many cases, researchers selected methods that enable design modifications beyond the reach of conventional processing, despite potential drawbacks in terms of scalability and cost. Certain methods were selected for unique capabilities not available elsewhere, while in other cases, comparable optimizations might also have been achieved with alternative techniques. Thus, it is important to consider the specific characteristics of each manufacturing method when evaluating the feasibility of reported component or cell design optimizations. The following outlines are provided to support this evaluation. A complete overview of all manufacturing methods exploited to apply the optimization approaches in the identified literature sources is shown in

Figure 2.

3.2.1. Conventional

In the sources reviewed, a group of manufacturing methods was identified that are based on the direct processing of liquid preparations of the materials for electrodes and electrolytes. The materials were dispersed in the preparations either as molar components or as particles ranging in size from micrometers to nanometers.

Although tape casting and screen printing are widely used for large-scale SOC production, only three studies applied these conventional methods specifically for optimization, with one particularly sophisticated version of co-casting, shown in

Figure 3, to print thinner layers and promote better adhesion [

24,

25,

26]. Both techniques employ a slurry of ceramic powder, organic binder, and plasticizers. Tape casting enables continuous roll-to-roll production of large-area green tapes, whereas screen printing applies the slurry through a mesh screen. These processes typically produce thicker layers (10 µm to several hundred micrometers) for porous electrodes or dense electrolytes, generally limiting thin-film applications [

27,

28,

29]. In addition, their use on three-dimensional surfaces is restricted [

30].

To achieve thinner electrolyte and electrode coatings, some studies employed spin [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] and dip coating [

35,

36,

37]. Spin coating involves rotating a substrate at high speed, with excess material removed by centrifugal force to leave a thin film. Dip coating relies on surface wetting after immersion in the liquid. Both techniques can produce submicrometer layers, though they are limited by their discontinuous process nature.

Two additional wet-chemical processing techniques are gel casting [

38] and vacuum slurry deposition [

39]. Gel casting enables the molding of complex components, though it remains discontinuous. In the reviewed literature, this method was applied in a single study to produce a relatively thick electrolyte. In contrast, vacuum slurry deposition was used to achieve thinner, denser electrolytes through drop coating. As with all wet-chemical solution techniques, subsequent heat treatment and sintering are required to achieve densification and mechanical properties [

5,

30]. For ultrathin layers, these steps can induce strain due to repeated thermal cycling [

29].

3.2.2. Additive Manufacturing

Several sources report on the application of additive manufacturing methods. Inkjet printing has been widely investigated for fabricating electrode and electrolyte layers [

28,

29,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. Overall, these methods are predestined for the creation of structured layers with intrinsic material gradients and/or defined surface structures. Two variants are distinguished: thermal inkjet, in which a heating element generates vaporization and pressure to eject droplets, and piezoelectric inkjet, in which a piezoelectric actuator expels ink via short electrical pulses [

28]. These approaches enable precise coating of nanoscale-loaded droplets, supporting both thin-film formation and 3D structuring over large areas [

47,

57,

59]. A further development, electrohydrodynamic inkjet printing, uses electrostatic fields to overcome surface tension, producing even finer droplets [

48]. A straightforward experimental layout with an industrial printer setup is shown in

Figure 4a.

Digital Light Processing (DLP), also known as stereolithography or vat photopolymerization, is a batch-based additive process. It has been investigated and found to be particularly suitable for producing three-dimensional structures between electrodes and electrolytes with thicknesses of 10 µm and above, as shown in

Figure 4b [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. The functional principle of this process is based on the use of a photocurable slurry loaded with particles of component material, which is solidified by exposure to a UV light source [

60]. In one study, both electrodes and the electrolyte were successfully manufactured in a single process step [

64].

Figure 4.

(

a) Electrode production process by industrial inkjet printing, adapted from [

57] with AI support; (

b) fabrication of a 3D structured electrolyte by DLP [

61].

Figure 4.

(

a) Electrode production process by industrial inkjet printing, adapted from [

57] with AI support; (

b) fabrication of a 3D structured electrolyte by DLP [

61].

The feasibility of achieving thin layers of 10 µm was also proven by using selective laser sintering (SLS). The sintering process was successfully carried out using a pulsed CO

2 laser at particularly low temperatures of 500 to 600 °C. The electrolyte layer was produced in a flat form, although SLS also enables the production of three-dimensional structures [

30]. The main difficulties with SLS are achieving dense layers and achieving good dimensional precision [

60]. Besides this, and in general, by the use of laser sintering on thin or structured layers of temperature-sensitive materials, the risk of material degradation exists.

3.2.3. Spraying

To obtain uniform microstructures with well-dispersed nanoparticles and reproducible pore distribution, several spraying processes have been applied for large-area coatings.

Spray drying deposits a slurry containing electrode, electrolyte, and pore-forming material into a hot medium, yielding reproducible distributions of material and pores. The method is characterized by a high production rate, and a subsequent sintering step is required [

65]. Granule spraying in vacuum (GSV) first agglomerates fine particles into larger granules via a nozzle system, which are then sprayed at high velocity in vacuum onto substrates. This achieves direct compaction without sintering, enabling deposition of both nanoporous electrodes and dense electrolytes [

66]. Similar sintering-free approaches include aerosol deposition and vacuum cold spraying [

67,

68].

In two approaches, electrostatic spray deposition (ESD) was carried out, in which a particle-loaded precursor solution is atomized and accelerated by an applied electric field between the nozzle and substrate. ESD also enables processability of small particle sizes and comes with the need for a subsequent sintering step [

69,

70]. Another proven option for spray coating fine particles and achieving uniformly porous and dense layers is wet powder spraying, alternatively known as suspension spraying. This process also requires high-heat after-treatment [

71,

72].

3.2.4. Solution Aerosol Thermolysis

The possibility of achieving a high degree of control over the porosity parameters and material composition is being exploited in several studies using spray pyrolysis, otherwise known as solution aerosol thermolysis (SAT). The option of precise control in particle size, shape, morphologies, composition, as well as uniform pore size and distribution derives from the ease of adjustment of the aerosol deposition parameter, e.g., substrate heating, temperature field within aerosol phase, nozzle to substrate distance, flow rate, and stochiometric ratios in precursor solutions [

73,

74,

75]. As explained in

Section 3.2.11, SAT can also be exploited by increasing to substrate distance for powder preparation. An explanation of these options is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The SAT can be described concretely in the following steps: solvent evaporation, precipitation of solute substances, decomposition of solutes into the inorganic phase directly onto the substrate surface [

73,

76]. This allows uniform application of layers over large areas to be achieved at high deposition rates and low-cost equipment, but with the need for heat treatment after deposition [

75,

77]. Accordingly, this coating method has been exploited by many authors for the production of electrode layers [

73,

74,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85].

An even more uniform film with uniform particle sizes can be achieved by supersonic spray pyrolysis, in which the precursor solution is atomized prior to the nozzle [

75,

77,

85]. While electrolyte layers have been successfully deposited, achieving adequate thickness necessitated multiple sequential depositions [

74,

81].

3.2.5. Thermal Spraying

Thermal or plasma spraying is another manufacturing method used in SOC research for processing both electrode and electrolyte material. In this technique, powder is accelerated and heated in a plasma jet, impacting the substrate at high velocity, where it flattens and solidifies into lamellar “splats” [

86,

87]. Four variants of plasma spraying were identified to be applied: (i) conventional atmospheric plasma spraying (APS) [

86,

88,

89,

90], (ii) low-pressure plasma spraying (LPPS) [

91,

92], (iii) suspension plasma spraying (SPS) [

87,

93], and (iv) solution precursor plasma spraying (SPPS) [

87,

94].

APS tends to produce porous structures due to splat formation, which has been exploited in electrode production [

86,

89]. Increasing plasma power enhances melting, enabling dense electrolyte deposition by APS [

88,

90]. LPPS, by contrast, enhances mass and heat transfer and can suppress lamellar morphology, facilitating dense coatings [

91,

92]. SPS employs nanoparticle dispersion, whereas SPPS generates particles from precursor solutions in the plasma flame, followed by a reaction and calcination. Both are suited to produce fine-particle coatings with well-defined microstructures for both electrodes and electrolytes [

87,

93,

94]. A further advantage of APS, LPPS, and SPS is that no subsequent sintering step is required [

90,

92,

93].

3.2.6. Physical Vapor Deposition

Physical vapor deposition (PVD) is widely applied in SOC research. It is conducted in a vacuum chamber between a cathode and an anode, where a target material is vaporized by physical processes and condenses onto a substrate [

9,

14]. The reviewed studies employed sputtering, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and electron-beam PVD.

Sputtering involves ion bombardment of the target, generating a vapor that deposits as a film. It is a common coating method to manufacture sliding surfaces, materials, and components with hard and wear-resistant layers. However, this method comes with the drawbacks of high costs, caused by the application of the vacuum itself. The vacuum chamber requirement and minimum deposition rates establish it as a time-consuming technique [

95]. Consequently, in the research studies considered here, it is applied to create especially thin layers from hundreds of nanometers to several microns [

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123].

One characteristic feature of sputtering is columnar grain growth in the deposited layer, particularly on rough or porous substrates. This morphology results in vertical pores, with voids between columns but no internal grain boundaries [

97,

102,

107,

113,

114,

120,

121]. This also results in low tortuosity between these columnar grains [

97,

100,

113,

114,

120]. Importantly, grain growth can be controlled by process parameters such as power, voltage, and coating temperature, enabling fabrication of grain-controlled layers (GLCs) [

96,

102,

103,

107,

114,

115,

119]. Co-sputtering enables deposition of two or more materials simultaneously by using multiple target materials, allowing precise adjustment of composition [

97,

114,

120].

In contrast, PLD employs high-energy laser ablation of a target material. However, its underlying molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood, limiting its use largely to experimental contexts [

95]. The advantages exploited in the research, in addition to thin layer deposition, are easy control of the microstructure from very dense to defined porosity, also of columnar grains, and the variation in the composition from more than one material [

27,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138]. Another advantage is the elimination of the subsequent sintering step [

132,

135,

136,

137,

139].

A further PVD method was applied in a single study with electron beam PVD to manufacture both electrodes and a thin, dense electrolyte. This process enables higher deposition rates up to several µm/s [

140].

3.2.7. Chemical Vapor Deposition

In chemical vapor deposition (CVD), precursor gases are transported through a heated chamber and directed onto a substrate surface, where a chemical reaction deposits the target material. Reaction byproducts are simultaneously removed by the gas flow to the exhaust of the chamber [

141].

Three studies applied aerosol-assisted CVD (AACVD) to deposit thin, dense electrolyte layers or to uniformly coat porous electrode structures with ultrathin electrolyte films [

142,

143,

144]. This technique uses an ultrasonic nebulizer to evaporate a precursor solution and deliver the resulting aerosol into the carrier gas under atmospheric conditions [

142,

143].

Laser CVD was applied in one study to achieve rapid electrolyte deposition under vacuum conditions. A layer thickness of 15 µm was achieved within 20 min, but subsequent sintering caused crack formation, likely due to excessively fine grains [

145].

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) enables the fabrication of uniform thin films, ranging from a few to several hundred nanometers, on rough or three-dimensional substrates. ALD operates by alternating injection of gaseous precursors, which undergo self-limiting surface reactions, forming single-atom layers that can be repeated to increase thickness [

95,

141]. Accordingly, ALD has been tested for the fabrication of thin electrolyte films and porous electrode structures [

104,

105,

146,

147,

148,

149].

A step further comes from using plasma in what is called plasma-enhanced ALD (PEALD) to excite the reactants already deposited so that they react more easily [

98,

150,

151].

Although CVD processes generally exhibit low coating rates, a study on oxygen electrode fabrication demonstrated an increase to 25 µm/min by employing plasma and aqueous solutions [

87].

3.2.8. Electrophoretic Deposition

Electrophoretic deposition (EPD) is a viable method for coating substrates, including porous and three-dimensional surfaces, with a dense material layer. In the reviewed studies, EPD was applied to deposit diverse electrolyte materials on electrode layers, achieving thicknesses from submicrometers to several tens of micrometers. The depositions can be realized within a scale of several minutes, but a subsequent sintering step at high temperatures is necessary afterwards [

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161].

The method is applied in a bath containing a stable dispersion of charged particles. An electric field is applied to the dispersion, and the particles are deposited on the oppositely charged electrode. As soon as the particles reach the substrate surface, neutralization happens, and a uniform, thick, and dense layer is formed [

155,

158].

3.2.9. Electrospinning

In one study, electrospinning was applied to fabricate highly porous electrode structures. This method generates ceramic nanofibers that can be deposited as gas-permeable layers. In the identified work, the spun material was suspended in a liquid solution and applied as a wet film (e.g., by brush painting) before sintering. The primary economic limitation is the low throughput of the spinning step, which converts only a few microliters of material into nanofibers per minute [

162].

3.2.10. Post-Deposition Methods

Beyond the fabrication of single-component layers, the reviewed studies also reported post-deposition methods aimed at tailoring geometrical and material properties.

One method to enhance the conductivity properties of electrodes involves impregnating nanomaterials into porous electrode or electrolyte scaffolds using simple deposition techniques such as dip or drop coating. Multiple impregnation cycles with intermediate heat treatment are often required to achieve sufficient nanoparticle loading [

163,

164,

165]. Inkjet deposition further enables precise droplet placement and the possibility of incorporating nanocomposite loading within processable inks [

41,

42,

44,

54,

59].

For fabrication methods such as sputtering, dense and uniform electrolyte layers require flat electrode substrates. In one study, the surface of a porous electrode was pre-treated with electron beams in order to smooth it. This process affects only the surface layer, thereby avoiding densification of the bulk structure and maintaining the gas diffusivity, which is essential for electrode performance [

110].

Nano-pulsed laser machining was applied to pre-sintered electrolyte plates to thin the center region while leaving a thicker ring at the edge, which improved structural stability. The laser process evaporated YSZ, generating nanoparticles that redeposited onto the electrolyte surface, producing a corrugated texture beneficial for electrolyte–electrode contact. The reported material removal rate was 0.2 µm/s [

166]. For three-dimensional electrode–electrolyte interfaces, one study pressed a mesh into the green electrolyte layer before sintering [

167].

To enhance gas permeability, another work applied freeze-drying to tape-cast green electrode layers. After freezing, particles precipitated within the solidified aqueous medium, and subsequent sublimation of ice created vertically aligned pores. The freeze-drying step took 12 h [

168].

3.2.11. Powder Preparation

A crucial step preceding all deposition processes is powder synthesis, where some approaches have been investigated to optimize SOC component properties. The Pechini route was applied in two studies to generate nanocomposite particles comprising electrode and electrolyte material surrounding an electrolyte core [

37,

169].

Several works used SAT for powder production [

76,

170,

171]. With increased nozzle-to-substrate distance, as presented in

Figure 5, in-flight sintering of decomposed inorganic phases occurred, producing fine powders with controllable properties [

76,

171]. The method yielded nano- to submicrometer crystalline fragments with high specific surface areas [

170].

In one case, powder ALD was utilized to load nanoparticles onto coarse oxygen-electrode particles, which were subsequently processed via screen printing onto electrolyte layers [

172]. The process of powder-ALD in comparison to conventional ALD is presented in

Figure 6.

The optimization approaches applied in the powder production step are especially valuable due to their upstream position in the process chain for solid oxide cell production, which can be easily applied as a detached step. Furthermore, it is a process engineering task allowing a pre-structuring and a positive impact on the resulting cell performance and quality, so obstacles in terms of costs and production rates can be overcome via scaling.

3.3. Applied Optimization Approaches

Optimization strategies can be grouped into four main fields. The first concerns geometric properties, particularly layer thicknesses, but also relates to material microstructure within dense components. Indeed, the optimization of the pore structure is also undoubtedly related to the microstructural properties of the components. However, enhancing the properties of the porous materials is also closely linked to gas permeability and is therefore listed as a separate approach. The third field of studies raised options for enhancing the reactivity using various methods. Furthermore, in the fourth field, some other approaches have been proposed with the aim of achieving improved structural stability of the cell structure.

Thus, this section summarizes the various means by which cell design can be improved at different points, initially without distinctive consideration of an applied manufacturing method. An overview of identified options to optimize SOC design is shown in

Figure 7.

3.3.1. Enhancement of Geometrical and Microstructural Properties

A fundamental approach to enhancing the cell’s performance is reducing electrolyte thickness. Since ohmic resistance in this layer directly governs ion conduction, thinner electrolytes can compensate for the lower conductivity of conventional materials, particularly at lower operating temperatures. This has significant potential, particularly given that conventional cell designs rely on a thick electrolyte layer of several hundred micrometers to provide the cell with the necessary structural stability. Consequently, this approach, which exclusively focused on electrolyte thickness, has been implemented in a number of studies for both oxygen ion and proton-conducting electrolytes [

25,

28,

29,

43,

45,

81,

98,

123,

140,

145,

148,

157,

166]. Further works particularly investigated the fabrication of a dense electrolyte, as this is another significant property, to separate the gas from the fuel and oxygen electrode sides [

66,

71,

88,

90,

91,

92,

106,

153,

154,

158,

159,

161]. A number of assessments have highlighted strategies that incorporate both thinner and denser electrolytes [

27,

30,

32,

36,

58,

93,

104,

110,

118,

119,

122,

146,

156]. In view of the significance of the density requirement, a number of specific strategies have been identified.

The first strategy involves high-temperature deposition, where increased deposition energy or power intensity promotes particle melting or higher-impact collisions, thereby yielding denser coatings [

66,

88,

90,

118,

119,

158].

The second strategy addresses porous or rough substrates. One approach that has been employed is the grounding of the substrate surface onto which the electrolyte is to be deposited [

86]. This is to obtain optimal conditions for downstream deposition methods, which result in non-uniform coating when applied to complex surfaces [

27,

71,

106,

110]. Alternatively, conformal deposition methods can be applied to coat finely structured or rough surfaces, reducing unevenness and enabling subsequent dense-layer formation [

104,

146,

154,

161].

Strategy three involves the use of finer particles or the deposition of small amounts of material. The aim is to achieve optimal grain growth and to prevent the formation of voids between larger grains [

55,

58,

93,

122,

156].

The same considerations apply to barrier layers, which not only provide ionic conductivity but also inhibit undesirable element diffusion between the electrolyte and electrode. Furthermore, it is important to note that layer thicknesses are applied within this context, always representing a fraction of the electrolyte layer [

28,

34,

47,

67,

70,

73,

80,

128,

155].

The approach of multi-layered electrolytes involves the application of specific electrolyte materials that exhibit superior oxygen ion conductivity at intermediate temperatures. However, it should be noted that all these materials inherently possess electron conductivity, thereby necessitating the incorporation of an electron-blocking layer, most commonly YSZ. Consequently, the requirement for this blocking layer is that it should be particularly thin. It has been indicated that research has been conducted on the exploitation of enhanced ion conductivity in gadolinium-doped ceria (GDC), as presented in

Figure 8 [

37,

73,

117,

125,

130,

149,

151]. Furthermore, the research demonstrates the potential of multilayer electrolytes in leveraging the advantages of SDC [

72,

126,

135,

137].

Design advancements have been achieved through tailoring the morphologies and microstructures of the materials themselves. On electrolyte surfaces, small grains provide more reaction sites, as reactions often occur at grain boundaries. Grain tailoring can be achieved by controlled grain growth [

102,

103,

115,

116,

121,

142,

147,

148] or by depositing smaller particles [

93].

In terms of the material’s bulk structure, there is a correlation between increased grain size and reduced grain boundary density, linked with higher ion conductivity observed throughout the bulk [

35,

88].

The incorporation of tensile stresses into electrolyte materials is proposed once, with the objective of increasing ionic conductivity. This phenomenon can be attributed to the facilitation of oxygen ion migration by intrinsic tensile stress [

116].

In addition, specific investigations into the optimization of thickness and adequate density have been conducted in the context of electrode layers. In the case of seven works, a completely dense functional electrode layer was applied at the interface to the electrolyte. The layer thicknesses were especially thin in the submicron range, thus ensuring that the exclusion of the gas phase did not become a disadvantage. In consideration of the composition of these layers, which consists of both electrode and electrolyte materials, or indeed mixed ionic electronic conducting (MIEC) materials, it is feasible to achieve an enlargement of triple-phase boundaries [

79,

82,

84,

109,

111,

138,

139].

Another crucial property is the in-plane conductivity of electrode functional layers. As the region at the electrolyte electrode interface may contain all three important phases (i.e., ionic, electronic conductivity, and gas diffusivity), the existence of a percolating path for electron transport is nevertheless important to achieve conduction to the outer, coarse, porous electrode layer. Otherwise, the formation of dead zones in the electrochemically active region could occur. Consequently, ensuring in-plane conductivity is an important factor in the design of electrode functional layers to achieve sufficient performance across the entire cell surface. Investigations considered this optimization aspect of film deposition by vapor condensation methods, with the objective of ensuring adequate gas permeability. The reason is the columnar grain growth by this fabrication technique, which counteracts in-plane conductivity [

99,

107,

132]. One way to counteract this is to increase the thickness of the layers, as shown in

Figure 9a,b. Another specific technique was presented, involving the placement of thin, porous interlayers of MIEC material into the electrode bulk, see

Figure 9c,d [

26].

3.3.2. Permeability

Various methods are being investigated to optimize the porous electrode structures in order to enhance gas diffusivity from the outer electrode side to the electrode–electrolyte interface, thereby ensuring a sufficient supply of reactive species at the reaction site.

An important parameter is the control of the porosity. On the one hand, the porosity must be high enough to ensure sufficient gas permeability. On the other hand, excessive porosity is detrimental to the electrical conductivity or structural integrity of the electrode. Specifically, two strategies were identified. The first involves adjusting the porosity by varying the concentration of powder material in precursor solutions in the case of wet coating and spray deposition [

57,

77,

85]. The second involves using process characteristics and parameters to achieve a specific porosity, as shown in

Figure 10a,b [

89,

132,

162].

Another property of permeable layers is the size of the particles within them. While smaller particles in the electrode can increase porosity, particles that are too small can be detrimental. Therefore, control over particle size is important for achieving good porosity control. Additionally, smaller particles directly increase TPB. The identified approaches achieved this control by adapting the process parameters. Direct control is important because the final particle size of the finished microstructure, after coating and subsequent treatments, is what ultimately matters. Especially given the highly complex nature of the particle formation process across these steps [

68,

77,

85,

87].

Three studies emphasized the importance of uniform pore distribution in ensuring sufficient permeability and conduction paths, without the creation of voids in between. The important aspects here are first, the stable deposition, which is thanks to the stable dispersion of pore formers in individual layers during component build-up [

60,

65]. A comparison between a detrimental porous structure and well-distributed pores can be found in

Figure 11a,b. Secondly, the uniform formation of pores across the entire surface during layer formation, while ensuring they are not covered by subsequently deposited particles [

171].

The size of the pores is also a relevant factor that significantly determines the properties of a coating. Precise control of the pore size was mainly achieved by adding pore formers, like starch or polymeric microspheres. These are dissolved particles that determine the desired diameter in the precursor solution, which are not very temperature stable. These pore formers are then removed by burning them out in subsequent heat treatments, see

Figure 11c–f [

40,

60,

83]. Another method of optimizing pore size involved removing pore-forming material phases by an etching technique, presented in

Figure 11g [

96].

Two publications have shown that gas permeability can be optimized by grading the pore sizes. The requirement that the outer layers of the electrode must predominantly exhibit electrical conductivity and higher gas permeability is addressed. When it comes to electrode areas at the interface with the electrolyte, though, smaller pore sizes are better because they lead to an increase in TPB. Grading the pore sizes, therefore, helps improve the supply and removal of the gases that feed the reaction. In both works, the pore sizes in the individual interlayers were controlled by adjusting the process parameters of the coating process, presented in

Figure 12 [

75,

130].

As indicated in the relevant literature, a selection of approaches to pore optimization can also be summarized under the aspect of pore orientation. The primary objective in this instance is to attain vertical permeability perpendicular to the layer plane. This is an approach to enhance the functionality of pores with regard to gas transportation. The vertical alignment of the pores results in low tortuosity, thereby enabling reactants to reach the electrochemically active zone in a direct and efficient manner. This is especially advantageous when compared to conventional electrode layers, in which the randomly distributed pore structure forces gases to travel along convoluted paths. The research presented herein proposes methodologies for the fabrication of coarser-pored outer electrode layers [

87,

168], or for the fabrication of thinner electrode functional layers with a fine-pored structure [

107,

113,

120,

130,

131,

133]. Examples of vertical pore orientations realized by different manufacturing methods are presented in

Figure 13.

The existing literature indicates that a potential method for enhancing gas transport to reaction sites is the creation of pore branching. The term “branching” is employed to denote the phenomenon of the paths of gas migration diverging from larger pores into smaller ones, thereby facilitating transport also in a horizontal direction towards reaction sites. One option is to realize fibrous structures on an electrode scaffold, presented in

Figure 14a [

113]. Other terms are utilized within the related literature, including but not limited to “coral microstructure”, which is employed in associated research that results from coating by means of fine spraying, thereby producing fine particles in the final layer,

Figure 14c [

69]. Another study described the production of a cauliflower microstructure achieved through controlled grain growth,

Figure 14b [

87].

3.3.3. Enhancement of Reactivity

The application of certain optimization methodologies has been demonstrated to result in an enhancement of the electrochemically active zone. This process entails a favorable interplay between the phases of electrical and ionic conduction, in conjunction with the gas phase. The objective is to facilitate the optimal supply and removal of the electrons, ions, and gases involved in the reaction.

In this regard, it is also important to reiterate the finding of an increase in grain boundary density in

Section 3.3.1. on the surface of an ionically conducting material, which possesses a greater number of reaction sites in comparison to the bulk of electrolyte grains.

A frequently studied concept involves the creation of a three-dimensional contact surface between the electrolyte and the electrode. At this interface, all three phases meet: the ion-conducting electrolyte, the electrically conductive electrode material, and the gas phase in the electrode’s pores converge in the TPBs. Consequently, an increase in contact surface area through a three-dimensional design of the interface leads to an extension of the active cell surface area. The structuring of the three-dimensional interface was conducted by fabricating different features in the literature, involving pillars, pyramids, parallel walls, crossing lattice walls like waffle or honeycomb structures, and also creating pits into one component, as presented within

Figure 15a–f. The presented heights in the literature can be distinguished into two scale categories. One group of heights ranges from 100 µm to 1000 µm [

38,

52,

61,

167]. Consequently, the interface extends into the outer electrode layers. In other projects, heights ranging from 5 to 100 µm were achieved [

30,

49,

50,

51,

53,

63]. Therefore, the introduction of a structured interface could be implemented within the functional layer of the electrode. Different architectures to achieve the interface structuring, by electrolyte or by electrode patterning, can be seen in

Figure 15g. In addition to the creation of different structured interfaces on one component, it is imperative to achieve a uniform coating by the other component, particularly in light of the resulting unevenness and perpendicular surfaces [

56,

152,

157].

A solitary investigation examined the methodology of patterning the electrode functional layer. In this instance, the electrode material was applied in the form of strips in each layer, with the individual layers oriented perpendicularly to each other. In addition to complete coverage, it is hypothesized that there will be an improvement due to an increase in TPB. This is expected to result from an increase in the number of pores between the strips, thereby achieving a higher active surface area from an increase in the number of reaction sites [

48].

An enhancement can also be achieved by structuring the interface at the nanoscale. Hereby, the roughness of the contact area between electrolyte and electrode is tuned, which can be separated roughly into two types. One regime that has been deduced from the evidence presented is within a range of the size of deposited nanoparticle, i.e., down to 3 nm, up to about 1 µm. In two studies, fine electrolyte particles were deposited into the pores of the electrode material [

54,

153,

159]. By another study, the deposition of electrolyte particles on the electrolyte surface was achieved, which was also assumed to result in an improvement by increasing the contact between the electrolyte and the electrode [

166]. In a similar manner, layers of electrolyte or electrode material with thicknesses ranging from 50 nm to several hundred nanometers were applied, with one example shown in

Figure 16 for nanoweb structured interface roughness [

31,

32,

33,

112].

In order to achieve an optimal build-up of ionic and electronic-conducting phases in the material bulk, with a view to increasing the three-phase boundaries, the literature has indicated different ways of enhancing the composition at the nanoscale. One field of study involves the control of composition at the level of individual grains. This was realized directly during the layer fabrication by process parameters [

97,

114,

120,

138,

139]. One study attained control prior to the coating process by employing molecular precursor solutions, which comprised immiscible phases of two materials and suppressed grain growth [

78]. Alternatively, the deposition of nanocomposite particles within porous electrode structures is a possible method of achieving the desired outcome. Also, in this instance, the establishment of a defined nano-composition can occur during the coating process or during the synthesis of the powder. Hereby, the production of simple composite particles with an undefined microstructure is one possible option [

76,

94,

170]. Otherwise, core–shell particles are characterized by the surrounding of the electrolyte material by the electrode material, or vice versa [

37,

46,

169].

The approach of depositing nano-film coatings on electrolytic material over finely structured, porous layers of electrode material is intended to achieve a large surface area of TPB, with the material in the core serving as an electronic conductor. The film thicknesses of electrolyte materials ranged from 2 nm to 150 nm. The various studies have indicated that the mechanism for achieving enhanced TPB may differ. One investigation involved the fabrication of thin coatings ranging from 2 nm to 9 nm on nano-rods of Ni. Although complete coverage was not achieved at low thicknesses, the coatings still provided sufficient coverage for substantial performance enhancements. It was hypothesized that electrolyte nanofilms with reduced thickness would impede detrimental isolation, thereby facilitating simultaneous electron and ionic conduction [

105]. The application of a coating of mixed ionic and electronic conducting material was further demonstrated to be a feasible option [

160]. Another option is the creation of an enlarged interface of electrolyte and electrode by means of the deposition of electrolyte material in the form of a nano-film electrolyte layer. The process of deposition of small material quantities onto porous electrode material results in the subsequent filling of the surface pores with electrolyte [

150].

The enhancement of the electrochemically active zone of the electrolyte and electrode can also be achieved through electrode nanoparticle deposition into porous structures of electrolyte scaffolds near the interface of both components [

59,

83,

134,

164]. An alternative architecture is given by the loading of electrode porous scaffolds with nanoparticles of ionic conductive materials [

41,

42,

44,

163,

165]. Both options are presented in

Figure 17.

The objective of creating pores at the nanometer scale is to enhance gas accessibility to reaction sites. An increase in the number of nanopores directly corresponds to an increase in the number of points at which the gas phase meets the conducting material for ions and electrons. This, in turn, results in a direct extension of the TPB. Three distinct works sought to achieve this objective through the incorporation of nanosized pores with a vertical orientation, thereby facilitating unrestricted flow. One possibility, as presented in

Figure 18a, achieved distinct vertical nanopores by an interface-engineered layer [

101,

112,

133]. Furthermore, the integration of nanopores in the lateral direction of the component resulted in an enhancement of the surface-to-volume ratio, thereby leading to a further expansion of the electrochemical zone [

94,

108]. Two works attempted to enhance performance by incorporating nanopores into the thin electrode functional layer. One example is shown in

Figure 18b,c. However, they acknowledged that more significant enhancements could be achieved by increasing the depth of the porous microstructure within the layer [

124,

127].

3.3.4. Enhancement of Robustness of Reactivity and Structure

An essential requirement for ensuring the sustained performance of cells is the ability to withstand mechanical and thermal loads. It is evident that specific optimizations in cell design have the potential to enhance reactivity. However, it should be noted that these optimizations are susceptible to deterioration due to detrimental influences that may arise during operation. The prevailing effect of performance degradation is attributable to thermal cycling of the cell. Elevated temperatures result in the extension of the component layers, thereby leading to the potential for interlaminar cracking. Increased thermal loads have also been demonstrated to induce coarsening of particles, which can result in the loss of beneficial properties, i.e., TPB length, within the pore structure or improved component interfaces.

In order to mitigate the impact of differing thermal expansion coefficients (TEC) in the electrode and electrolyte materials, two investigations have been conducted with similar design concepts. These investigations involved the implementation of material-graded electrode layers, characterized by a higher proportion of material exhibiting a TEC that is comparable to that of the electrolyte close to the interface [

69,

129].

One study raised the possibility of developing more flexible electrode structures to reduce stress between the two components. Specifically, a structure was created in which a grid pattern was formed by printing perpendicular strips of electrode material from one sub-layer to another [

48].

Dense interlayers of electrode materials have also been shown to increase the contact area between the electrode and electrolyte, thereby enhancing the adhesion between these components. In the three studies, layers with a thickness not exceeding 1 µm were fabricated. There is a need to preserve the effect of the interaction of all three phases for the electrochemical reaction, and thereby layer thicknesses have to be maintained at a minimum [

109,

111,

131]. An Example is illustrated in

Figure 19a.

In some cases, an enhancement in layer adhesion was observed, which was attributed to an increase in the roughness of the contact surface between the two components. On the one hand, the nanostructured surface of the electrolyte layer made a significant contribution [

31,

33,

153]. Furthermore, the deposition of electrolyte material into the open pores of the electrode was also a technique for increasing the roughness [

152,

168]. The existence of particular parameters and conditions during the coating process may also result in enhanced adhesion between the layers. Specifically, the sources cited examples of increased temperatures or pressures during deposition, which led to a stronger bond between the electrode and electrolyte materials [

39,

101]. As certain fabrication methodologies for electrolyte layers are sensitive to imperfections and porous substrates, in order to achieve dense microstructures, it has been demonstrated that a flattening of the electrode surface, as shown in

Figure 19b–e, can assist in increasing the contact area and layer bonding. Nevertheless, this results in an inherent constraint on the potential for further enhancement of adhesion, as previously discussed in relation to methods that involve increased roughness above [

86]. Therefore, caution is required by this optimization approach.

For the purpose of realizing the potential of the aforementioned design approaches for the optimization of microstructures in porous materials, in conjunction with high-temperature post-treatments and operating conditions, the implementation of comprehensive strategies to stabilize these is beneficial. Consequently, a number of sources have proposed strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of these circumstances. These assist in the suppression of undesired grain growth, the prevention of particle agglomeration, and the maintenance of a high surface area and TPB density. One potential solution involves the incorporation of additional materials that impede the growth and agglomeration of particles. The execution of this process may be undertaken during the coating process itself, as shown in

Figure 20a, or by means of formulating the appropriate composition of the materials required. In a wet precursor solution, this enhancement can be promoted by creating immiscible phases of the electrode material and the stabilizing materials [

78,

114]. A more sophisticated approach involves loading electrode powder material with nanoparticles, which aid stabilization through the entire electrode structure, as shown in

Figure 20b for powder-ALD [

172]. An alternative approach is also seen in the coating of already fabricated porous layers with thin coatings of electrode materials, with the objective of encapsulating the particles in the structure, as presented in

Figure 20c [

105,

144,

160].

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The PRISMA-ScR methodology approach proved effective in this review, identifying optimization approaches alongside suitable manufacturing methods. Critical assessment highlighted both scalability challenges and potential alternatives for the fabrication or modification of SOC components. Overall, the analysis shows substantial overlap between manufacturing methods and design strategies for SOC architectures.

By combining effective optimization approaches with the available manufacturing methods, the PRISMA-ScR methodology provided a solid foundation for identifying research gaps and developing targeted recommendations, which are presented in the outlook of this section.

Addressing research question 1, the evidence converges on the following SOC design measures as the most effective levers for performance, durability, and lower-temperature operation: Effective approaches to the design of solid oxide cells (SOCs) include thinning and densifying electrolytes (including multilayer ceria–yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) blocking concepts) in order to reduce ohmic losses and enable operation at lower temperatures. At the electrodes, ultrathin, dense functional interlayers of mixed ionic-electronic conductors (MIECs) with assured in-plane conductivity, together with engineered porosity (graded, vertical, or branched) and three-dimensional or nano-roughened interfaces, increase the TPB and improve gas transport, adhesion, robustness, as well as electrochemical performance.

Regarding research question 2, the literature converges on a set of scalable manufacturing methods capable of implementing these design measures with precise control over thickness, porosity, composition, and 3D interfacial architecture.

Research question 3 can be addressed through a component-wise analysis, examining how each fabrication method enables the intended design optimizations under practical constraints (scalability, cost, and process control) across electrolytes, electrodes, and their interface.

High SOC performance relies heavily on careful electrolyte and barrier layer design combined with an appropriate choice of fabrication method. The central challenge is producing layers that are simultaneously thin and dense, while using methods that are both scalable and cost-effective. Modern approaches such as inkjet printing, solution aerosol thermolysis (SAT), and electrophoretic deposition (EPD) have proven effective in addressing these demands across multiple studies. While most investigations concentrated on achieving simultaneously reduced thickness and increased density, alternative concepts have been proposed. These include multilayer electrolytes employing composite materials and targeted microstructural engineering, particularly grain-size control. Conventional processes such as tape casting, screen printing, and dip and spin coating were used sparingly. This is largely due to their limitations: tape casting and screen printing cannot easily yield thin layers, while dip and spin coating are discontinuous. In contrast, methods such as spraying, plasma spraying, and pulsed laser deposition offer further advantages by eliminating the need for subsequent sintering.

Optimization strategies for SOC electrodes have targeted a wide range of design parameters, from pore formation to the development of fine material composites. In electrode functional layers, optimization was primarily directed toward achieving suitable layer thickness and density to improve performance and stability. Many studies applied downstream processing methods such as impregnation or surface modification, thereby increasing process-chain complexity. In contrast, relatively few approaches addressed upstream optimization, such as tailoring during slurry or solution preparation. In such cases, the approach referred to the Pechini method at best. In the context of electrode fabrication, nearly all reviewed techniques were identified as suitable, with the exception of EPD and thin-film approaches such as sputtering or atomic layer deposition.

At the electrode–electrolyte interface, optimization has focused on creating three-dimensional contact geometries or controlled roughness. Among the reviewed methods, electrophoretic deposition (EPD) and inkjet printing demonstrated clear advantages. The strength of EPD lies in its ability to uniformly coat porous, rough electrode surfaces, whereas inkjet printing affords fine control over the roughness of deposited films and further enables the fabrication of three-dimensional interfacial architectures.

In view of the findings, it is intended that our own deliberations on several aspects of the SOC research area and our own conceptualisations be formulated. The development of precursor materials, particularly wet pastes and inks, which are processed through a variety of manufacturing methods for the production of cell components, holds immense potential. This would facilitate the enhancement of porous fine-structured material compositions, which have typically been accomplished through complex or multi-step downstream methodologies such as wet etching, burning out pore formers, or impregnation so far. Consequently, we propose close collaboration with experts in surface chemistry and colloid science for future development in the field of SOC.

It is evident that certain manufacturing methods, such as PVD, CVD, and electrospinning, offer unique opportunities for SOC design enhancements, yet their elevated equipment costs and limited production rates currently set a high barrier to economic feasibility. To support the future ramp-up of SOC technology, robust techno-economic analyses will be required to identify when these methods might become cost-effective. While their rational application under present production scales is doubtful, their adoption in large-scale, high-volume manufacturing may become realistic.

Achieving intended design improvements further depends on the integration of complementary manufacturing methods across the various cell components. This is particularly evident in the fabrication of 3D interfaces, where, despite the diversity of achievable geometries, subsequent coating steps remain decisive for layer adhesion and mechanical stability. Further research is therefore needed to assess the related issues of uniform subsequent coating, structural strength, and crack formation. Additionally, little attention has been devoted to optimizing the relative surface-area ratios of electrochemically active regions across the fuel electrode, oxygen electrode, and electrolyte. Simulation-based studies could provide an effective starting point for addressing this gap.

Despite the scarcity of studies on proton-conducting SOCs, the findings of this review provide a promising basis for transferring design improvements to this cell type. One such approach is the use of graded electrolyte materials within electrodes, which can alleviate the problem of TEC mismatch—an issue more severe in PCCs than in oxide-ion-conducting systems. Similarly, the concept of multilayer electrolytes holds significant potential, where unstable proton-conducting electrolyte layers are reinforced by structurally supportive layers with complementary conductivity properties. The role of colloid science is equally evident here. By tailoring electrode materials to deliver electron, oxygen-ion, and proton conductivity simultaneously, it is possible to predefine material structure before sintering, thereby offering greater stability compared with post-synthesis impregnation approaches. With these self-formulated approaches, the strength of this review should be emphasized, as it is based on the broad presentation and discussion of various optimization approaches coupled with manufacturing methods. This facilitates rapid familiarization with the subject matter for developers and scientists interested in the field of SOCs and their possibilities. This should facilitate the initiation and implementation of their own developments, as well as the identification of their potential, including in the emerging field of proton-conducting cells.