1. Introduction

Climate change and environmental pollution represent critical global challenges with significant ramifications for human health and quality of life. Scientific evidence indicates that anthropogenic activities, including industrial emissions, deforestation, and urbanization, are the primary drivers of climate change, giving rise to extreme weather events, rising global temperatures, and air pollution [

1,

2,

3]. Many types of adsorbing materials have been developed and characterized in the literature, targeting different applications such gas separation [

4], water decontamination [

5], and thermal energy storage [

6,

7].

CO

2 capture is among the various carbon-management strategies under development [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The technology of adsorption-based separation, and, in particular, pressure swing adsorption (PSA), has emerged as a favorable solution for post-combustion CO

2 capture, owing to its comparatively modest energy requirements and modularity. PSA accounts for approximately 85% of hydrogen purification worldwide, reflecting its entrenched industrial role and continuing process refinements [

12,

13]. In a PSA cycle, a fluid mixture is passed through a packed bed of porous solid sorbent: under elevated pressure, CO

2 tends to bind to the sorbent’s surface during the adsorption stage. When the system is subsequently depressurized, the sorbent releases the CO

2, allowing it to be regenerated and the captured gas to be collected [

14,

15]. Recent

Energies contributions quantify PSA’s techno-economics and process design for steelwork off-gases using dynamic Aspen Adsorption models, reporting high purity/recovery trade-offs and clear energy levers via cycle tailoring [

16].

Alternative swing strategies include temperature swing adsorption (TSA), which regenerates the sorbent by heating and often incurs higher thermal energy penalties, and vacuum swing adsorption (VSA), which uses sub-ambient pressures for desorption. For example, Zhao et al. 2019 [

17] investigated TSA performance and evaluation for post-combustion carbon dioxide capture, while Verougstraete et al. 2025 [

18] discussed the challenges and opportunities of enhanced TSA within electric heating. Hybrid modes such as temperature–vacuum swing adsorption (TVSA) combine moderate heating with reduced pressure to balance energy consumption and cycle time, while vacuum–pressure swing adsorption (VPSA) employs both vacuum and elevated pressures to optimize purity and recovery [

19,

20]. Alongside PSA, thermally driven temperature swing adsorption (TSA), vacuum swing adsorption (VSA), and vacuum–pressure swing adsorption (VPSA) expand the design space to balance purity, recovery, productivity, and energy consumption under diverse feed compositions and regulatory specifications [

21,

22,

23]. The choice among these strategies depends on trade-offs between energy use, cycle throughput, and equipment complexity [

21,

24].

Optimizing PSA performance requires accounting for the coupled effects of mass transfer, adsorption kinetics, and heat transfer within the column [

25,

26,

27,

28] but also for their appropriate scaling [

29]. While one-dimensional process models can capture overall mass balances and cycle performance, they cannot resolve local phenomena such as hot spots, bad flow distributions, or inter-particle concentration gradients that critically affect scale-up and sorbent longevity. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) offers a powerful means to simulate the full three-dimensional Navier–Stokes equations coupled with adsorption and energy balances, providing spatially and temporally resolved predictions of concentration and temperature fields. Such insights guide the design of sorbent geometries, column internals, and operating protocols to enhance CO

2 capture efficiency, though translating high-fidelity CFD to industrial practice remains an active area of research.

At the heart of adsorption processes lies the interplay between equilibrium thermodynamics and transport kinetics within the sorbent porous medium. Equilibrium isotherms describe the maximum CO

2 loading as a function of pressure and temperature,

, encapsulating sorbate–sorbent affinity and site heterogeneity [

30]. However, reaching equilibrium in a dynamic PSA cycle is governed by mass-transfer resistances spanning macropore convective flow, meso- and micropore diffusion, and film resistance at the gas–solid interface. These multi-scale transport phenomena are often lumped into an overall mass-transfer coefficient, which is typically inferred from breakthrough or volumetric uptake experiments. Such bulk measurements obscure the contributions of individual diffusion regimes, making it difficult to pinpoint the true rate-limiting steps under realistic cycle times [

31].

Moreover, adsorption is intrinsically exothermic: the heat of adsorption ( 20–40 kJ/mol) generates local temperature rises that shift equilibrium and slow uptake. Traditional calorimetric and thermal-probe measurements yield only averaged or near-wall temperature data, leaving hot-spot formation and internal thermal gradients unresolved. As a result, scale-up based on bench-scale thermal information can lead to unexpected performance gaps at pilot-plant or industrial scales, where axial and radial heat transfer limitations become pronounced.

Given these experimental limitations, in both measurement uncertainty and spatial resolution, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) emerges as an essential tool for achieving detailed, predictive insights into adsorption-bed performance. By coupling the Navier–Stokes equations with species transport, energy balances, and adsorption kinetics models on a three-dimensional mesh, augmented when necessary, with user-defined functions for rate laws and thermal effects, CFD enables non-intrusive mapping of local concentration fronts, temperature gradients, and flow irregularities. High-fidelity CFD studies have been employed to quantify how wall conduction, distributor geometry, and internal components (e.g., heat exchangers) influence PSA efficiency, and to conduct parametric explorations of particle shape, bed aspect ratio, and cycle timing before undertaking costly experiments or full-scale fabrication [

25,

26].

Three-dimensional CFD of multiphase counter-current flow in packed beds for post-combustion capture has clarified the coupling between hydrodynamics and interfacial area insights transferable to gas–solid contactors [

32,

33]. CFD has likewise been applied to adsorption thermal systems (e.g., chillers) to validate geometry-specific pressure/temperature fields against experiments, closing modeling–measurement loops [

34]. For TSA hardware, coupled experimental–numerical studies of heat transfer in bubbling fluidized beds inform the design of efficient regenerators and guide process heat integration [

35].

All the CFD models discussed in this technical review were applied to physical adsorption processes, assuming laminar flow regimes due to the relatively low gas velocities typical within porous media and the fixed nature of adsorbent particles. These models generally simplify the flow behavior by neglecting turbulence, thus focusing on the laminar flow regime through stationary porous structures. While turbulence is known to significantly influence industrial-scale PSA operations during stages with higher gas velocities, such as purging and vacuuming, this is not our focus in this technical review, which is more focused on laminar flows.

By integrating these insights, the present technical review constructs and sheds light on the fundamental physics of adsorption, which naturally leads to the role of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) in the design and optimization of heat exchangers–adsorbers (HEX-As). The main objective is to provide a critical review on models (1D, 2D, and 3D) from the literature that were developed during the last decade to model and simulate physical adsorption in packed beds of adsorbing porous media. The aim is to address a research gap in 3D CFD modeling of HEX-As for CO

2 capture, gas purification, and gas separation, with a focus on PSA and TSA techniques. This review is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the pressure swing adsorption (PSA) cycle.

Section 3 examines the computational modeling of adsorption phenomena. In

Section 4, we provide a comparative overview of 1D process models and kinetic formulations, followed by a discussion of representative 2D and 3D CFD studies. This includes an analysis of advances in flow characterization enabled by 3D CFD modeling, and the role of CFD in enhancing adsorption bed design and performance. Finally, we outline current modeling challenges, recent trends in hybrid and multi-scale modeling approaches, and future research directions, before concluding.

2. Pressure Swing Adsorption Process

2.1. History and Applications

Scientific research on adsorption started in the 18th century, through Scheele’s early investigations on air adsorption on activated carbon in 1773. Significant advancements occurred with Ostrejko’s patents in 1900, which ultimately facilitated the large-scale production of activated carbon materials.

The inception of PSA processes is typically associated with the early works of Skarstrom and Guerin de Montgareuil and Domme between 1957 and 1958 [

36,

37]. However, it is noteworthy that several elements of this process were even identified much earlier in different previous studies such as the primary investigations by Kahle, as well as in different patents registered between 1927 and 1930 [

38,

39].

With time, PSA has been gaining significant commercial recognition as the preferred technology for hydrogen purification [

40], air separation, and small-scale air drying applications. Furthermore, PSA is utilized in various other processes, including the extraction of methane from landfill gas and the capture and generation of carbon dioxide [

41].

Notable developments include the introduction of large-scale PSA systems for air separation and hydrogen processing [

42]. The adsorption technology is highly efficient and well-established, featuring the benefit of reusable adsorbents. It is also environmentally friendly and relatively straightforward and quick to install. However, it comes with certain limitations: it often requires a prior treatment to eliminate additional impurities such as hydrogen sulfide (

) and water vapor, demands adsorbents with very specific characteristics, and typically involves high energy consumption, especially in the handling of flue gas and during the Thermal Swing Adsorption (TSA) process. Typically, the purity achieves ranges from 50% to 99%, while recovery rates fall between 30% and 90% [

43].

The PSA process is usually applied in natural gas purification, oxygen production, and CO

2 capture. Over the years, this technology has found numerous applications in various domains, such as methane upgrading [

44,

45], carbon dioxide capture [

46], air separation [

47,

48], noble gas purification [

49], and hydrogen purification [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Currently, the main industrial applications of pressure swing adsorption are concentrated on hydrogen purification and air separation, especially in the production of oxygen for medical purposes [

19,

55,

56].

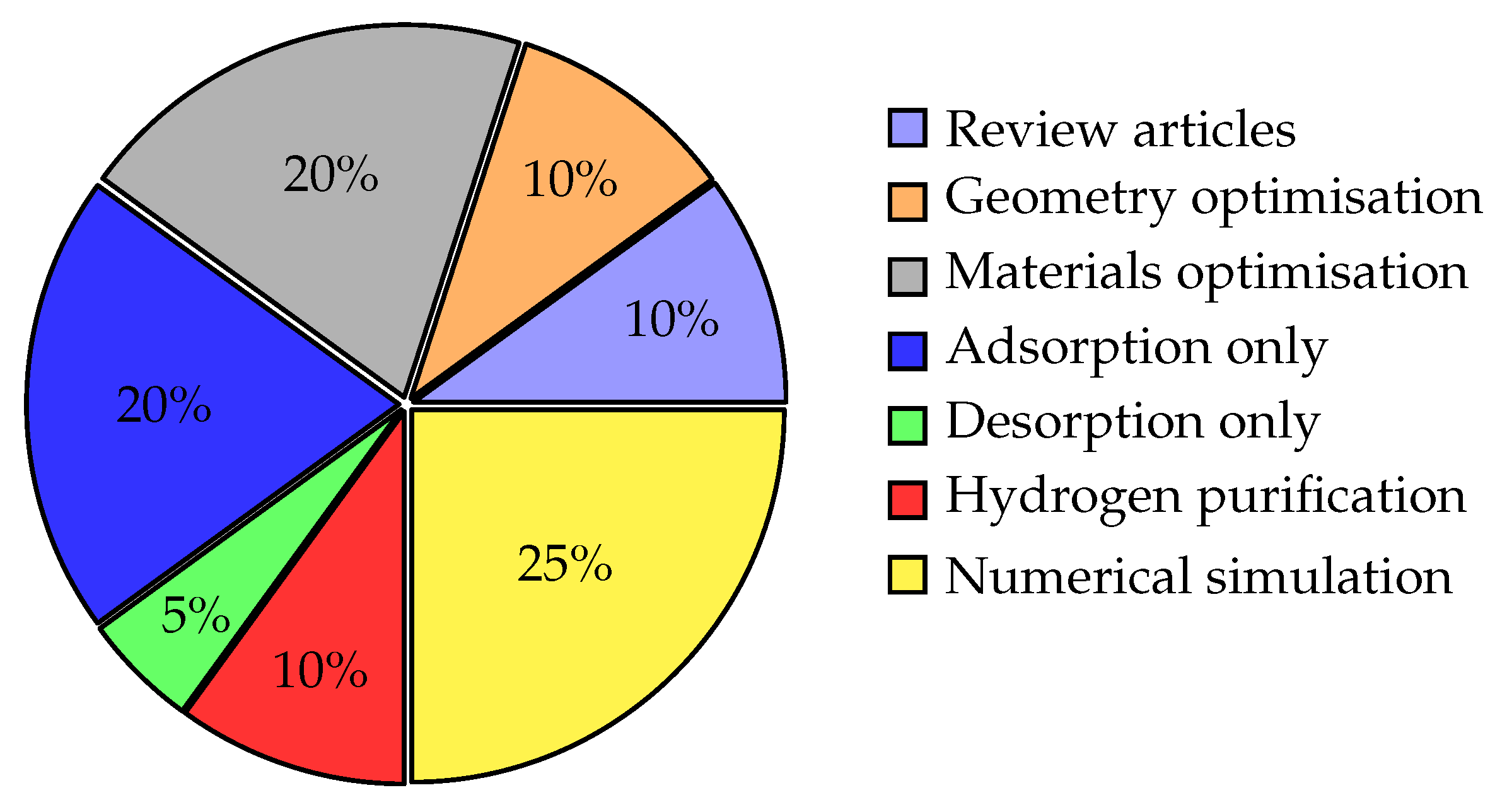

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of publications related to physical adsorption, based on published papers retrieved from Google Scholar, highlighting a predominant focus on computational modeling, with

numerical simulations accounting for the largest portion,

25% of the surveyed articles. This category encompasses a wide range of modeling approaches, including 1D, 2D, and 3D simulations, reflecting the broad integration of numerical methods in process optimization and predictive analysis of adsorption systems.

Notably, this strong presence of simulation-based studies should not be confused with the relatively limited adoption of full-scale 3D CFD modeling. While many works employ simplified 1D or 2D models due to their reduced computational cost, high-fidelity 3D CFD studies remain scarce, despite their potential to capture complex flow and heat and mass transfer phenomena in real geometries with higher spatial resolution.

In parallel, significant attention is directed toward material optimization, 20%, and adsorption behavior, 20%, underscoring the importance of sorbent design and process-specific material characterization in enhancing system performance. These efforts focus on tailoring key adsorbent properties, such as porosity, surface characterization, and selectivity, for applications ranging from carbon capture to gas separation.

Review articles and studies focused on hydrogen purification each account for 10% of the publications, reflecting a steady but secondary interest in general overviews and specific energy applications. Geometry optimization, 10%, and desorption modeling, 5%, are less frequently explored, despite their critical roles in system performance, particularly in regeneration cycles and flow uniformity.

Overall, the literature reveals a technically oriented field with a strong emphasis on numerical modeling and material science, yet also exposes gaps in high-resolution 3D CFD approaches, desorption, and phase modeling, areas that warrant greater research attention to achieve comprehensive adsorption-system optimization.

2.2. PSA Underlying Physical Mechanisms and Skarstrom’s Cycle

Li et al. (2009) [

57] described the underlying major mechanisms of adsorption in gas separation, such as (a) molecular sieving, which selectively filters gas components based on size or shape exclusion; (b) thermodynamic equilibrium, determined by the interactions between the adsorbent surface and adsorbate; and (c) kinetic effects, arising from variations in diffusion rates of the gas mixture components.

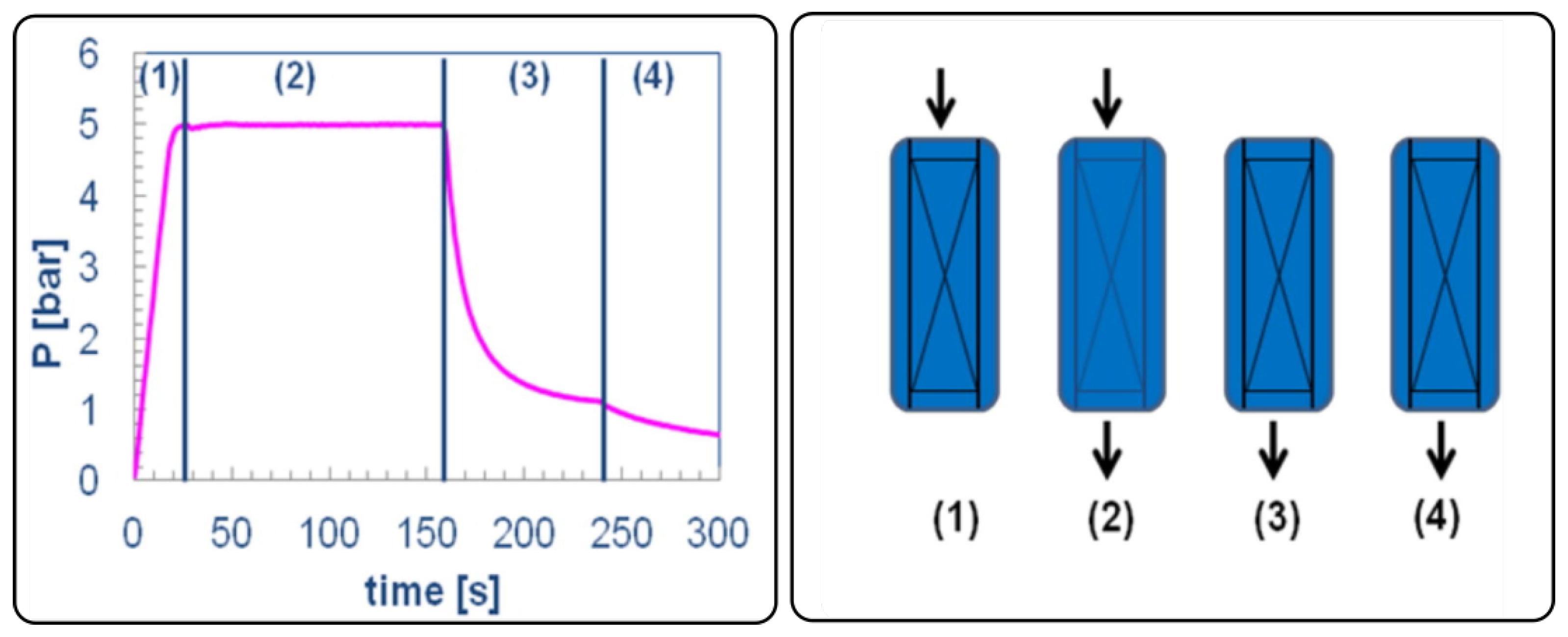

The PSA process is a common way to separate gas components on the basis of cyclic pressure changes, which induce adsorption and desorption steps for specific compounds. The cyclic adsorption process (PSA) was first introduced by Charles Skarstrom in 1932 [

58] through the development of what became known as the Skarstrom cycle. This cycle includes four key steps—(1) pressurization step, (2) adsorption step, (3) blowdown step, and (4) vacuum step (or regeneration)—as shown in

Figure 2 Gautier et al. (2018) [

59]. During the process, once the adsorbent material in the column reaches saturation, the column’s pressure is lowered, triggering a partial desorption of the sorbates accumulated in the bed Grande et al. (2012) [

19]. The key for a proper PSA operation is the variable level of affinity that gas components have between themselves and toward adsorbent material, combined with the ability to reverse adsorption using pressure as a driving force. Multi-bed systems and PSA with pressure equalization between the beds yield higher energy efficiency and gas recovery rates. The sequences are managed to ensure that the system is working at capacity and that purity of the product in question remains high.

3. Computational Modeling of Adsorption Physics

Beyond the transport equations, an accurate computational description of gas-phase adsorption must be informed by the underlying physics of the adsorption phenomenon itself. In porous media, adsorption is governed by inter-molecular interactions, predominantly Van Der Waals forces, that facilitate the adherence of gas molecules to the internal surfaces of the solid adsorbent. This process is typically exothermic, releasing heat upon adsorption, which introduces important thermal effects that must be accounted for in the energy balance. The porous structure of the adsorbent material enhances the available surface area, increasing the adsorption capacity but also introducing complex multi-scale transport behavior. Furthermore, the selectivity of the adsorption process, defined as the preferential uptake of one species over another, is critical in separation applications such as carbon capture. This selectivity arises from differences in molecular size and affinity to the adsorbent surface, and is often modeled through adsorption isotherms and kinetic expressions. Therefore, incorporating these physicochemical interactions into CFD frameworks is essential for capturing the coupled mass, momentum, and energy dynamics that govern the performance of adsorption-based separation systems.

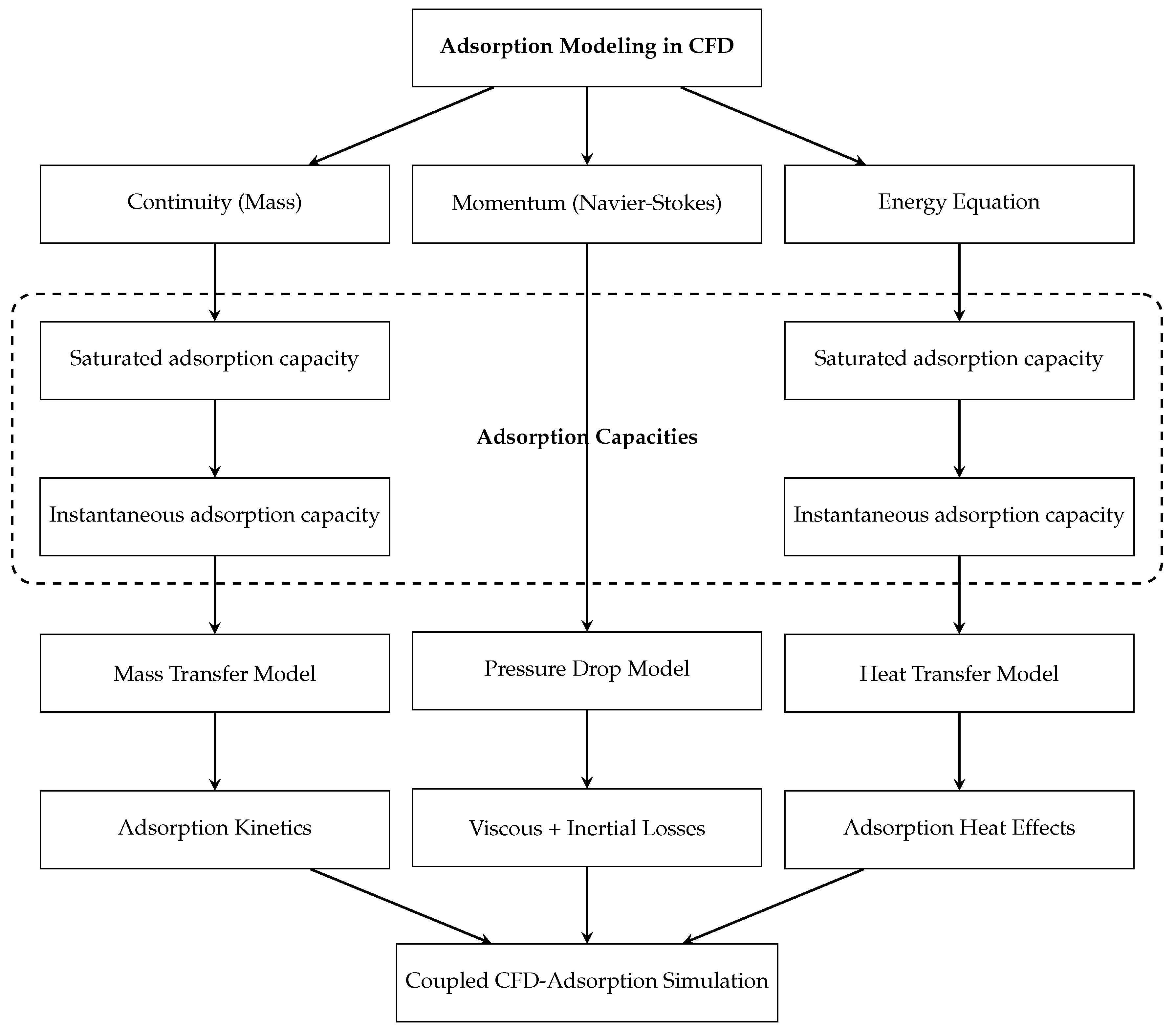

The diagram in

Figure 3 delineates a comprehensive computational framework for modeling gas-phase adsorption processes within the context of computational fluid dynamics (CFD). The modeling approach is grounded in the fundamental conservation equations, the continuity equation for mass conservation, the Navier–Stokes equations for momentum conservation, and the energy equation governing heat transport. These governing equations provide the foundation for capturing the transport phenomena intrinsic to HEX-As.

Subsequent to the application of these conservation laws, adsorption behavior is characterized through two key descriptors: the saturated adsorption capacity, representing the equilibrium uptake limit of the adsorbent, and the instantaneous adsorption capacity, which accounts for the transient mass accumulation on the adsorbent surface. These quantities form the basis for the development of mass transfer models, describing the rate-limiting transport of adsorbate from the bulk phase to the adsorbent surface, and heat transfer models, which resolve the thermal effects associated with the exothermic nature of adsorption.

In parallel, the momentum equations inform the pressure drop model, which incorporates both viscous and inertial losses to quantify flow resistance across the porous medium. The outputs of these submodels, mass transfer, heat transfer, and pressure drop, are further coupled with adsorption kinetics and thermodynamic relationships, thereby enabling an integrated representation of the physicochemical interactions governing adsorption.

The result is a fully coupled CFD adsorption simulation platform capable of resolving the complex interplay between flow dynamics, thermal effects, and adsorption equilibria. This multi-scale, multi-physics approach provides a robust predictive tool for the design, analysis, and optimization of adsorption-based separation systems, enhancing both operational efficiency and process reliability in academic and industrial applications [

60].

Modeling of Adsorption Isotherms

The driving force behind adsorption is an externally induced imbalance, which prompts the system to adjust in order to establish a new state of equilibrium. The experimental data pertaining to the adsorption process is typically presented in the form of adsorption isotherms. This is due to the fact that it is most convenient to study the adsorption process at a constant temperature, particularly in the case of the pressure swing adsorption process [

61]. Adsorption isotherms are models that describe how gas or solute molecules adsorb onto the surface of a porous solid as a function of pressure or concentration. The main adsorption isotherm models used in CFD are presented in chronological order in

Table 1, with each model offering insights into the type of adsorption (monolayer, multilayer, heterogeneous, etc.) and surface characteristics. The references listed in the table correspond to the foundational works that introduced each isotherm model, while the citations provided in this section refer to studies that have analyzed their characteristics or applied them in various gas separation and adsorption systems. While different adsorption isotherms (e.g., Langmuir, Freundlich, Toth) are frequently used in CFD models, there is a lack of guidance on when to use each model.

As illustrated in

Table 2, a comprehensive overview of the utilization of adsorption isotherms across a range of computational models, encompassing 1D, 2D, and 3D frameworks, is provided. The table underscores the prevalence of kinetic models, gas mixtures, and dimensions employed in contemporary studies. Notable mentions are the frequent applications of Langmuir and Toth models, which underscore their remarkable adaptability in delineating adsorption equilibria. A predominant trend observed in most studies is the employment of the linear driving force (LDF) model for the analysis of adsorption kinetics. This approach is notable for its capacity to streamline predictions of mass transfer and maintain efficiency in computational processes. The diversity of gas mixtures studied, including CO

2/N

2, CO

2/CH

4, and CO

2/H

2, demonstrates the applicability of these models to a wide range of industrial applications.

4. Comparative Modeling of Heat Exchangers–Adsorbers (HEX-As)

In this section, various studies on the modeling of the adsorption phenomenon will be presented, with a detailed focus on the conservation equations for mass, energy, and momentum. These studies will be structured along three initial lines based on the dimensionality of the models: 1D, 2D CFD, and 3D CFD.

Increasing the dimensionality of the numerical description does not simply refine the spatial resolution; it qualitatively changes the correspondence between the model and the real fixed bed. In 1D models, the column is reduced to a line of control volumes representing cross-sectionally averaged quantities; the gas inventory and the solid mass are defined per unit cross-section, so convective transport and adsorption heat are interpreted as averaged fluxes along the axis, and any lateral non-uniformity (wall channeling, maldistribution, local hot spots) is irreversibly lost. Introducing a 2D CFD description, typically in an axisymmetric (r,z) domain, explicitly resolves the cross-sectional area and thus radial variations in porosity, interstitial velocity, temperature, and loading. This allows one to capture phenomena such as wall-to-core temperature differences, radial distortion of the adsorption front, and the shielding effect of the wall acting as a heat sink, all of which strongly influence the local adsorption rate in an exothermic process. In a full 3D CFD model of the real geometry, the numerical volume coincides with the experimental bed volume, so that the total amount of gas in the domain corresponds to the true number of moles present, and the distribution of the void fraction and solid surface follows the actual packing and internals. As a result, the convective transport of energy by the gas phase, the amount of heat released by adsorption and subsequently carried away by the flowing gas, and the local cooling and reheating cycles along tortuous flow paths become quantitatively and qualitatively consistent with the physical system. Three-dimensional simulations further resolve azimuthal asymmetries induced by non-ideal distributors, imperfect packing, and structural elements (inlet nozzles, supports, baffles), revealing channeling, bypass regions, stagnation zones, and localized hot or cold spots that cannot be represented in 1D or even in idealized 2D axisymmetric configurations. In this sense, going from 1D to 2D, and from 2D to 3D, progressively transforms an axially averaged view of heat and mass transfer into a physically meaningful representation where gas inventory, convective enthalpy flux, and adsorption-induced thermal effects are intrinsically linked to the true three-dimensional structure of the porous bed.

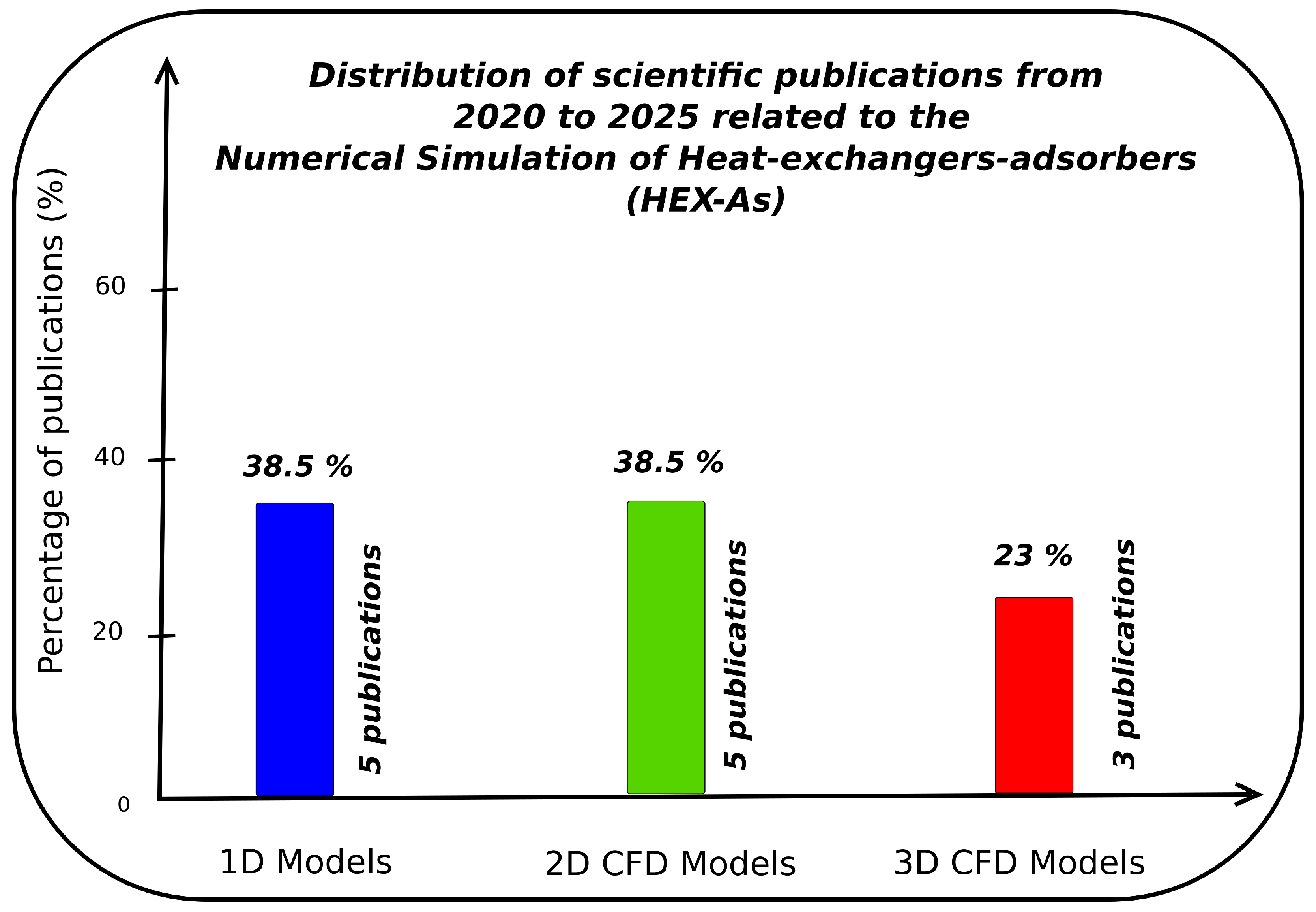

Figure 4 illustrates a summary of the scientific publications appearing between 2020 and 2025 related to the numerical modeling and simulation of HEX-As, categorized into three modeling approaches—3D CFD, 2D CFD (including axisymmetric), and 1D (non-CFD)—to compare modeling dimensionality and the adoption of computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Among these 13 published papers, approximately

38.5% employed

1D models, and

38.5% utilized

2D models (some of which are CFD-based), but only

23% focused on

3D CFD models. This highlights that, although lower-dimensional models continue to dominate, fully three-dimensional CFD modeling constitutes a clear research gap in the literature. It is worth noting that representative 1D studies remain valuable for kinetic analysis and process screening, yet they lack spatial fidelity [

83]. In contrast, 2D (often axisymmetric) CFD models can reproduce global trends under symmetry and simplified radial assumptions but rapidly reach their limits when addressing non-symmetric features (e.g., inlet maldistribution, internals) or exploring design variants [

80]. With the rapid progress of high-performance computing and parallel simulation frameworks, the need for fully three-dimensional simulations is becoming increasingly important. Unlike 1D and 2D approaches—which rely on spatial averaging—a 3D approach enables detailed resolution of the flow in complete designs. It can better illustrate the temperature gradients and local adsorption dynamics, particularly in geometrically complex or heterogeneous systems or designs. Despite these advantages, the 3D literature remains strikingly rare and sparse. Our present review survey identified only three publications, underscoring the need for further 3D CFD studies on HEX-As to deepen our physical understanding of phenomena and enhance the designs by optimization [

84]. In very recent work by Nadamani et al. (2025) [

85], the authors developed and validated a macroscopic 3D multiphase CFD framework with new source terms that can account for pore-site occupation effects, subsequently applying it to assess the design of asymmetric HEX-As. As the adsorption field advances toward more predictive and scalable modeling approaches, 3D CFD is expected to become an indispensable tool for research and industrial design, offering high levels of insight and reliability.

4.1. One-Dimensional Models

One-dimensional (1D) models are widely used in adsorption column modeling due to their simplicity and efficiency in simulating continuous processes. In many cases, gas component concentration, temperature, and pressure profiles primarily vary along the length of the adsorbent bed, allowing for simplified calculations while achieving reasonably accurate predictions for industrial applications. The 1D approach provides a quick and useful estimate for initial design and optimization of adsorption systems, though it has limitations in capturing spatial variations and more complex three-dimensional effects.

Table 3 summarizes various studies from the literature that applied one-dimensional PSA models for gas separation, focusing on the processes, adsorbents, and major outcomes.

4.1.1. Mass Conservation

Casas et al.’s (2012) [

74] species mass conservation equation is as follows:

where

and

denote the concentrations of species

i in the fluid phase and the adsorbed phase, respectively. The term

u refers to the superficial gas velocity. The symbols

and

represent the total void fraction and the bed void fraction. The bulk density of the packed bed,

, corresponds to the mass of adsorbent contained in the column divided by the volume of the bed. The axial dispersion coefficient,

, is taken to be identical for all components. The variable

indicates the mole fraction of species

i in the gas phase, while

t and

z denote the temporal and spatial coordinates, respectively. The mass conservation equation, Equation (

1), of Casas et al. (2012) [

74] incorporates axial dispersion (

) and interphase mass transfer through the

term, emphasizing the diffusive and convective transport of species.

Streb et al.’s (2021) [

75] species mass conservation equation is as follows:

The mass conservation equation, Equation (

2), of Streb et al. (2021) [

75] solves convective transport and adsorption kinetics but neglects axial dispersion, which is usually applicable in systems where dispersion effects are minimal.

Zhang et al.’s (2022) [

76] species mass conservation equation is as follows:

In this formulation by Zhang et al. (2022) [

76], the bed void fraction

is applied consistently throughout the equation, and axial dispersion is neglected. However, in the equation by Streb et al. (2021) [

75],

did not appear in front of the term

.

4.1.2. Mass Conservation: Comparative Analysis

The reviewed equations highlight diverse modeling approaches for mass conservation in adsorption systems. The general equation provides a foundation, while individual authors adapt terms to suit specific applications. Casas et al. (2012) [

74] emphasize dispersion effects, while Streb et al. (2021) [

75] adopt a simpler form for cases with negligible dispersion.

Zhang et al. (2022) [

76] extend the formulation by integrating solid-phase adsorption dynamics. Collectively, these equations demonstrate the trade-off between complexity and computational efficiency in adsorption modeling.

4.1.3. Momentum Conservation

Fluid motion through a porous medium can be modeled using Darcy’s law for linear flow, which was originally formulated by Henry Darcy in 1856 in his work titled

Les Fontaines Publiques de la Ville de Dijon [

86]. For non-linear flow effects, corrections such as the Forchheimer term and the Ergun equation are applied. The theoretical development of the Forchheimer equation is detailed in [

87]. The Ergun equation, introduced by Sabri Ergun, provides a comprehensive approach to account for both viscous and inertial effects in packed columns [

88].

The gas flow velocity within the column is obtained by applying Ergun’s equation, using the specified pressure drop across the packed bed to determine the corresponding velocity profile; different authors, Casas et al. (2012) [

74], Streb et al. (2021) [

75], and Zhang et al. (2022) [

76], use the same equation, Equation (

4):

4.1.4. Energy Conservation

Casas et al.’s (2012) [

74] energy conservation equation is as follows:

In this expression, T denotes the temperature inside the column, while represents the temperature at the column wall. The terms , , and correspond to the heat capacities of the gas phase, the solid adsorbent, and the adsorbed phase, respectively. The quantity is the isosteric heat associated with the adsorption of species j. The parameter represents the heat transfer coefficient between the column interior and its wall. Additionally, is the inner radius of the column and denotes the axial thermal conductivity.

The energy conservation formulation in Equation (

5) considers the contributions of convective heat transfer; adsorption heat release (

) used as an average value, which, in reality, depends on the amount adsorbed, according to Schell et al. 2012 [

89]; and thermal diffusion through the packed bed using the thermal conductivity term

.

Streb et al. (2021) [

75] describe the energy balance for the column as follows:

and the energy balance for the wall as follows:

Here, represents the overall void fraction, and u is the superficial gas velocity. The symbols T and refer to the temperatures within the column and at the wall, respectively. Heat transfer from the gas–solid mixture to the wall is described by the coefficient , while characterizes the heat exchange from the wall to the surrounding thermal fluid.

In Equation (

6), the effective radial thermal conductivity,

, and the wall heat transfer term,

, are combined into a single composite parameter,

, for simplicity. Both

and

account for static and convective contributions. Additionally, note that the term

is not the appropriate form for the convective energy transport in the energy balance, as its units and structure do not match the standard formulation used in energy conservation equations.

Zhang et al.’s (2022) [

76] energy conservation equation is as follows:

In Equation (

8), Zhang et al. (2022) [

76] divide the domain into two phases: fluid and solid. The fluid phase accounts for the void volume by multiplying by the bed void fraction

, while the solid phase represents the total solid particles in the bed. Here,

denotes the effective thermal conductivity.

4.1.5. Energy Conservation: Comparative Analysis

The energy equations employed by various authors are clearly different. Casas et al. (2012) [

74] and Streb et al. (2021) [

75] included a heat capacity for adsorbed phase

, but using different implementations of thermal conductivity. Zhang et al. (2022) [

76] applied a holistic approach, incorporating wall heat loss and axial conduction. All these different formulations of the energy conservation equation reveal a significant question: how can conjugated heat transfer in adsorption beds be precisely modeled using 1D models and at what cost of accuracy versus computational time?

4.2. Two-Dimensional CFD Models

Two-dimensional CFD models can provide a better insight into the radial variations inside the adsorption column.

Table 4 shows various studies employing CFD for modeling adsorption processes, focusing on different gas mixtures, adsorbent types, and the employed methodology. Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] focused on multi-dimensional CFD modeling of CO

2 separation using activated carbon and MOF-177 for CO

2/N

2 and CO

2/H

2 mixtures, demonstrating that aspect ratios have minimal effect on adsorption performance. In a related study, Chen et al. (2017) [

78] utilized CFD and experimental validation to optimize offshore gas purification with 13X zeolite, concluding that quiescent adsorption with a voidage of 0.35 offers the most energy-efficient performance. In a related study, Khan et al. (2024) [

79] developed multi-scale CFD models with silicate adsorbents for CO

2/CH

4 systems. These models employed user-defined functions (UDFs) in ANSYS (Workbench 16) to predict adsorption and hydrodynamics accurately under varying conditions. Finally, Ramos et al. (2024) [

80] validated two-dimensional CFD modeling of CO

2/N

2 HEX-As using 13X zeolite, showing that CFD provides valuable insights into spatial gradients, enabling column design optimization. The collective significance of these studies lies in their demonstration of the versatility of CFD modeling techniques, the necessity of validating simulation results with experimental data, and the expanding potential of CFD for enhancing the design and efficiency of adsorption processes.

Table 4 summarizes various studies from the literature that applied two-dimensional PSA models for gas separation, focusing on the processes, adsorbents, and major outcomes.

Ramos et al. (2020) [

80] and Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] applied 2D CFD simulations to demonstrate detailed spatial variations in CO

2 concentration within the packed bed of HEX-As. Unlike 1D models, which assume uniform radial distribution, 2D CFD models can capture both axial and radial concentration gradients, providing insights into local phenomena such as flow distribution, bypass zones, and underutilized regions of the flow. Ramos et al. (2024) [

80] showed clear radial and axial variations in CO

2 concentrations inside the bed that would be averaged out in 1D modeling approaches, while Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] highlighted the impact of column design on the local concentration profiles. These insights are critical for optimizing adsorption column performance, as 2D CFD models strike a balance between capturing local phenomena and computational efficiency, offering improved accuracy over 1D models without the complexity of full 3D simulations.

4.2.1. Mass Conservation

The following equations represent the mass conservation equations used in various 2D CFD studies to model adsorption processes in packed beds:

Ben-Mansour et al.’s (2017) [

77] species mass conservation equation in 2D CFD is

where

is the void fraction,

is the species concentration,

w is the velocity in the radial direction, and

represents axial diffusion terms. Equation (

9) models the transport of species

i in a cylindrical packed bed, considering axial and radial diffusion along with adsorption and desorption. It includes terms for convective flux, dispersion, and interaction between the gas and adsorbent phases, making it suitable for capturing radial effects.

Chen et al.’s (2017) [

78] species mass conservation equation in 2D CFD is

In this context,

denotes the void fraction of the adsorber, and

is the density of the adsorbent particles. The molar mass of species

i appears in the formulation to represent how the fluid phase interacts with the solid adsorbent. Equation (

10) describes the interaction between the fluid and solid phases. It includes the mass fraction

, convective and diffusive terms, and the adsorption rate, making it ideal for cases where the interaction between phases is crucial.

Khan et al.’s (2024) [

79] species mass conservation equation in 2D CFD is

where

is the particle density,

is the gas concentration, and

is the column dispersion coefficient. Equation (

11) includes diffusion and convection in both axial and radial directions and considers adsorption within the packed bed through the column dispersion coefficient

.

Ramos et al.’s (2024) [

80] species mass conservation equation in 2D CFD is

In this formulation,

represents the density of the gas mixture, and

denotes the velocity vector of the flowing fluid. The parameter

refers to the density of the adsorbent particles, while

indicates the void fraction of the packed bed. The molar mass of the adsorbed species

i is given by

, and the term

corresponds to the rate at which species

i accumulates on the solid phase. Equation (

12) describes gas-phase mass conservation including convective flux and source terms due to adsorption/desorption.

In Equation (

9), Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] explicitly formulate the diffusion in cylindrical coordinates, including the radial term with the

factor, which ensures proper radial spreading in axisymmetric systems. In contrast, Khan et al. (2024) [

79] use Cartesian derivatives without coordinate-dependent corrections, implying a planar 2D model (

11). Additionally, Ben-Mansour et al. apply a fully conservative form for the convective terms and maintain the void fraction within the transient and dispersive terms, while Khan et al. normalize the adsorption source by

and arrange terms in a non-conservative form, which may affect numerical consistency.

In Equation (

10), Chen et al. (2017) [

78] model dispersion using a bulk diffusion coefficient multiplied directly by the local species mass fraction, which results in a source-like term that does not explicitly depend on spatial gradients. In contrast, Ramos et al. (2024) [

80] (

12) adopt a classical Fickian dispersion approach. In this case, the dispersion flux arises due to spatial variations in the mass fraction of the species. This gradient-based formulation provides a more physically consistent representation of axial and radial spreading in porous media and aligns with conventional advection–dispersion–reaction models.

All the above Equations (

9)–(

12) solve mass conservation in HEX-As in 2D CFD but with differences in their mathematical formulation. This opens a question: how can mass conservation of multi-component gaseous adsorption in 2D CFD be accurately modeled?

4.2.2. Momentum Conservation

The porosity model adopted by Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77], Chen et al. (2017) [

78], and Khan et al. (2024) [

79] is as follows:

The porosity model adopted by Ramos et al. (2024) [

80] is as follows:

4.2.3. Energy Conservation

The following equations describe the energy balance for adsorption processes using 2D CFD models:

Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] represent energy balance in the gas phase as

and energy balance in the solid phase as

Here, denotes the specific heat of the gas at constant volume, while represents the specific heat at constant pressure. The parameter is the thermal conductivity of the gas, and corresponds to the specific heat of the adsorbent bed. The term refers to the heat released during adsorption of species i, and is the heat transfer coefficient between the gas phase and the reactor wall.

Equation (

15) accounts for the gas-phase energy conservation in two dimensions, including heat transfer through conduction and convection, and the heat effects due to adsorption/desorption.

Chen et al. (2017) [

78] represent energy conservation in 2D CFD as

The formulation in Equation (

17) describes the local heat transfer by employing the internal energy of the fluid and particles in addition to an effective thermal conductivity model.

Khan et al. (2024) [

79] represent energy conservation in 2D CFD as

Equation (

18) expresses the two-dimensional CFD energy balance for the gas phase, accounting for both convective and conductive heat transfer, along with the thermal effects associated with heat released during adsorption.

Ramos et al. (2024) [

80] represent energy conservation in 2D CFD as

Equation (

19) integrates detailed interactions between phases, including terms for heat transfer, adsorption exothermic effects, and the influence of species-specific heat capacities.

In Equation (

15), Ben-Mansour et al. (2017) [

77] explicitly describe the thermal dynamics of both the gas and solid phases by solving distinct energy balance equations for each: one governing the gas phase and the other for the porous solid matrix. Their approach incorporates heat exchange between the gas and solid phases, interaction with the column wall, and the thermal effects associated with adsorption. In contrast, Khan et al. (2024) [

79], in Equation (

18), simplify the energy conservation by using a single energy equation for the gas phase only, neglecting explicit solid-phase heat accumulation and interphase thermal coupling. Additionally, Ben-Mansour et al. include radial conduction in cylindrical coordinates with detailed source terms for both phases, whereas Khan et al. employ a 2D Cartesian conduction term and represent adsorption heat effects only within the gas-phase equation. In Equation (

17), Chen et al. (2017) [

78] employ a total energy formulation with fluid and solid internal energies (

and

), and include the pressure work and viscous dissipation terms, representing a more general enthalpy transport equation, while using

to denote effective thermal conductivity for the entire porous medium. In contrast, in Equation (

19), Ramos et al. [

80] use a simplified sensible heat formulation based on explicit heat capacities (

and

), neglect the pressure work and viscous terms, apply

, explicitly scaled by the void fraction to represent gas-phase heat conduction only, and add additional correction terms to account for the sensible heat of adsorption (

) and its coupling with the transient adsorption kinetics. This results in Ramos et al.’s model explicitly correcting for the heat stored in the adsorbed phase and its temperature dependence, which Chen et al.’s formulation implicitly combines in the total internal energy terms.

4.3. Three-Dimensional CFD Models

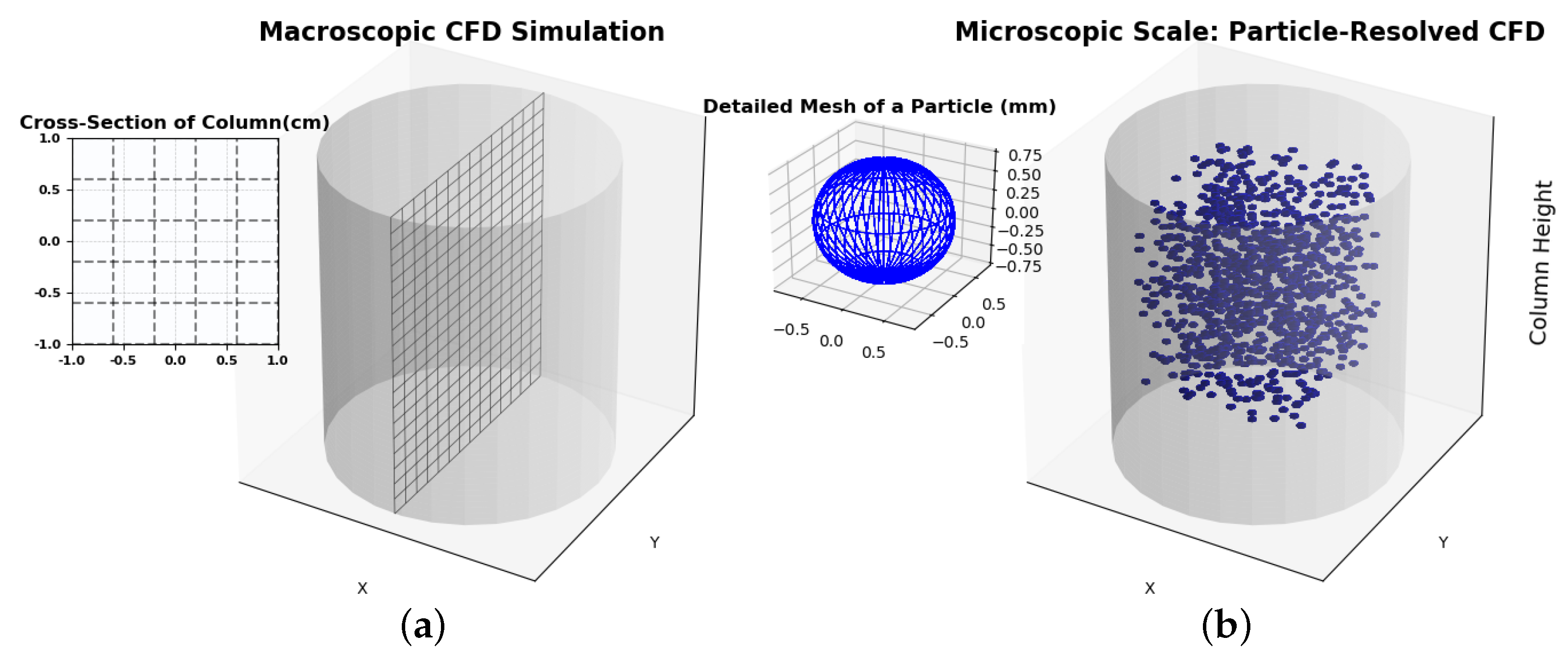

Three-dimensional CFD simulations of HEX-As can be rarely found in the literature compared to two-dimensional CFD simulations. This is very strange given the significant progress in high-performance computing. Three-dimensional CFD models have the advantage of providing a detailed description of the local flow dynamics, temperature, and local gas concentration kinematics inside the bed. Different modeling approaches can be applied depending on the required level of detail and the computational resources available. The choice between macroscopic and microscopic models impacts the precision, computational load, and applicability of the results in real-world scenarios. Due to their need for high-resolution calculations, microscopic models are computationally intensive and are often limited to small-scale studies or specific regions within the adsorption column. These models provide critical insights into fundamental adsorption processes, though scaling them up to simulate entire columns is often infeasible due to resource constraints (

Figure 5b).

Macroscopic models simplify the complex phenomena occurring within the adsorption column by averaging them over a larger, representative elementary volume (REV) (

Figure 5a). This approach allows for the description of the overall behavior of the system without requiring resolution down to the molecular level. Key principles in macroscopic modeling include mass, momentum, and energy conservation laws, often expressed through partial differential equations (PDEs) that describe concentration gradients, pressure drops, and heat transfer along the column [

90,

91,

92].

Macroscopic models assume homogeneity within each REV, allowing for the simplification of variables such as porosity and adsorption capacity. By averaging properties at this level, macroscopic models capture the dominant trends in column performance, such as breakthrough curves and overall separation efficiency, without resolving microscopic details. Macroscopic models are particularly useful for large-scale simulations where the primary interest is the overall column performance, rather than detailed pore-scale interactions. This approach allows for modeling of adsorption under various flow conditions, column configurations, and adsorbate–adsorbent combinations. Macroscopic models are computationally less demanding than microscopic models and are thus suitable for engineering applications and optimization studies where rapid assessments of different column designs or operating conditions are required. However, they may overlook certain molecular-level interactions that could impact adsorption performance under specific conditions, such as non-ideal behavior at high adsorbate concentrations or in highly heterogeneous media. In summary, macroscopic models are ideal for simulating overall column performance in engineering applications, while microscopic models are indispensable for fundamental studies of adsorption mechanisms at the molecular scale. Combining these approaches, or using hybrid models, can sometimes offer a more balanced solution, capturing essential details of adsorption while maintaining computational efficiency for larger-scale simulations [

93,

94].

Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of three different CFD studies focusing on the 3D modeling and numerical simulation of adsorption phenomena. These works evaluate the efficiency and optimization of PSA processes through different models and adsorbent materials. The comparison highlights the methodologies, objectives, and key outcomes of each study, offering insights into advancements in 3D CFD modeling for gas separation and purification processes.

4.3.1. Mass Conservation

The following equations describe the mass conservation in 3D CFD studies applied to HEX-As:

Gautier et al. (2018) [

59] describe species mass conservation in 3D CFD as

Here, denotes the density of the gas mixture, and u is the superficial velocity. The symbol represents the porosity of the packed bed, while is the molar fraction of species i in the gas phase. The molecular weight of species i is given by , and corresponds to the density of the CMS cylinders (adsorbent material).

Equation (

20) represents the mass conservation for species

, incorporating diffusion (

), convection, and source terms for adsorption on the solid phase. It is particularly suited for multi-species adsorption systems.

Qasem and Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81] describe species mass conservation in 3D CFD as

Here,

represents the gas density, and

is the mass fraction of species

i. The vector

denotes the gas velocity, while

is the porosity of the packed bed. The parameter

corresponds to the mass dispersion coefficient,

is the molecular weight of species

i, and

represents the amount of species

i adsorbed on the solid phase. Equation (

21) includes the effects of dispersion (

) and convection for species

. It is particularly focused on describing the influence of the porous medium on mass transport.

Wang et al. (2020) [

82] describe species mass conservation in 3D CFD as

where

is the mass fraction. This species balance accounts for transient accumulation and convection of species

i, along with diffusive transport and a source term due to adsorption.

All three equations, Equations (

20)–(

22), describe species conservation for a gas component in a packed bed, including accumulation, convection, diffusion/dispersion, and a term for adsorption onto the solid phase.

Table 6 presents differences that arise in how porosity is included in the convection term, the type of velocity used (superficial vs. interstitial), the mathematical form of the diffusion or dispersion term, the sign convention for the adsorption source term, and whether mass or molar fractions are used. These distinctions reflect different modeling assumptions and numerical implementations. This opens a question: how can mass conservation of multi-component gaseous adsorption be accurately modeled in 3D CFD?

4.3.2. Momentum Conservation

Gautier et al. (2018) [

59], Qasem and Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81], and Chouikhi et al. (2020) [

95] all incorporate Darcy’s law to describe flow through porous media, with Forchheimer corrections included to account for non-linear flow effects, as follows:

4.3.3. Energy Conservation

The following equations describe the energy conservation equations applied in different 3D CFD studies in the literature:

Gautier et al.’s (2018) [

59] energy conservation equation in 3D CFD is

The energy conservation equation (Equation (

24)) captures the energy transport within the adsorbing column, including convective (

) and conductive (

) heat transfer, mechanical work (

), and the heat of adsorption (

).

Qasem and Ben-Mansour’s (2018) [

81] energy conservation equation in 3D CFD is

This formulation (Equation (

25)) integrates the energy contributions from bulk flow (

), conduction (

), interfacial transport (

), and adsorption heat release (

).

Wang et al. (2020) [

82] describe energy conservation for the gas phase as

and in the solid phase as

The three equations mentioned above (

24)–(

26), describe energy conservation in packed-bed adsorption systems, accounting for heat accumulation in the fluid and solid phases, convective transport, thermal conduction, viscous dissipation, and heat effects due to adsorption. Although all three studies address the same fundamental physical problem, heat transport in a porous adsorber undergoing gas/solid adsorption, their energy conservation equations reveal important differences in mathematical formulation and physical assumptions. Gautier et al. (2018) [

59] and Qasem & Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81] adopt a single, combined energy balance that simultaneously accounts for the thermal energy stored in both the gas and the solid phases within one equation, implicitly assuming thermal equilibrium or very fast interphase heat exchange. In contrast, Wang et al. (2020) [

82] implement a dual-equation approach in which the gas phase and the solid phase each obey a distinct energy balance, enabling explicit modeling of finite-rate interphase heat transfer through a dedicated heat exchange term. This difference affects how accurately local temperature gradients between phases can be resolved, especially under transient or strongly non-equilibrium conditions.

Regarding transport mechanisms, Qasem & Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81] enrich their energy equation with an explicit species enthalpy diffusion term,

, capturing the sensible heat carried by species diffusion, a feature absent from the other two models, which treat heat conduction independently of mass diffusion. For convective heat transport, Gautier and Wang use the superficial gas velocity scaled by porosity in the energy flux, while Qasem & Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81] instead use the interstitial velocity without a porosity factor, implying a different scale of averaging for the gas–solid system.

Moreover, the source terms for adsorption heat release differ slightly in sign convention: Gautier and Wang consistently use

to represent the exothermic nature of adsorption as a sink for gas enthalpy, whereas Qasem & Ben-Mansour (2018) [

81] use

, requiring careful sign handling to ensure that energy conservation aligns with the direction of heat generation. Finally, only Wang’s formulation resolves interphase heat exchange explicitly via a convective heat transfer coefficient and a characteristic particle diameter, allowing the model to distinguish between the gas and solid temperature fields, unlike the lumped or fully equilibrated treatment implied in the other models.

These differences highlight how variations in mathematical structure such as combined vs. separate phase balances, explicit vs. implicit interphase coupling, and inclusion or omission of species enthalpy flux can lead to different numerical behavior and modeling fidelity, even when addressing the same physical scenario of adsorption-driven heat transfer in packed beds.

4.4. Advancing Flow Analysis Through 3D CFD Modeling

Table 7 highlights the essential distinctions between 1D, 2D, and 3D PSA models. One-dimensional models remain the primary choice for cycle optimization because they require minimal computational effort and limited experimental data. Two-dimensional models extend the description by capturing radial gradients and wall effects, which become relevant for large columns or highly exothermic systems. Three-dimensional CFD provides the most detailed representation, resolving full geometry and non-uniform flow features, and is therefore useful for diagnosing maldistribution, channeling, and complex column designs that lower-dimensional models cannot adequately describe.

Although 3D CFD provides detailed insight into PSA operation, its routine use remains limited. The approach is computationally demanding, requiring fine meshes and numerous time steps to resolve full-column geometries over entire PSA cycles. Model development is also more involved, necessitating careful treatment of porous media, boundary conditions, and the coupling of transport equations with adsorption kinetics. Parameter estimation and validation are hindered by the lack of local experimental data, leading to reliance on global measurements. As a result, 3D CFD is typically used selectively for design assessment or hypothesis testing. Publications on CFD cases applied to 3D PSA columns are rare and dispersed.

Haddadi et al. (2016) [

96] studied the pressure drop in randomly packed-bed adsorbers by employing the adsorpFoam solver, which was developed within the OpenFOAM

® framework. Their study emphasized the importance of spatial resolution in packed beds, focusing on bypass streams, void zones, and near-wall effects. The validation results showed a strong agreement between the experimental and simulated pressure drops, demonstrating that adsorpFoam can accurately capture key flow characteristics.

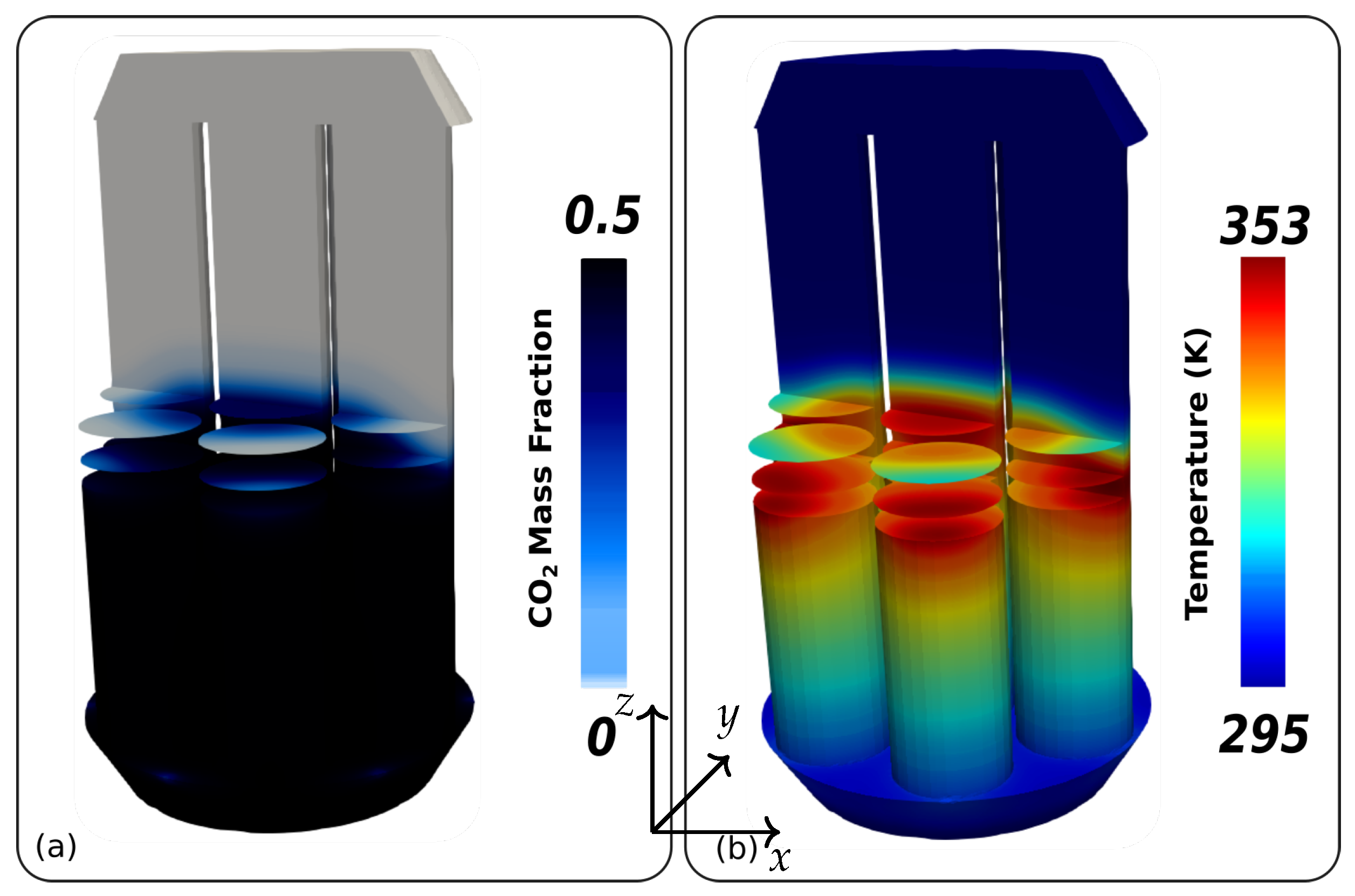

Gautier et al. (2018) [

59] conducted a 3D CFD study in isotropic porous media. Their study included a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of parameters such as thermal conductivity, mass transfer coefficients, and the choice of equilibrium isotherm models. The study underscored the importance of accurate initial conditions for the adsorbed phase and showcased the potential of 3D CFD to predict heat and mass transfer during PSA cycles.

Kasai et al. (2023) [

97] developed a comprehensive CFD model for predicting adsorption rates in granular activated carbon packed beds. Using detailed geometric configurations, their work highlighted the interplay between adsorption kinetics, heat transfer, and flow distribution. Their simulations demonstrated the need for integrating kinetic models with CFD for accurate predictions of adsorption performance.

A comparison of the methodologies and findings from the three 3D CFD studies found in the literature is summarized in

Table 8.

The articles reviewed in this work highlight diverse methodologies in the CFD modeling of adsorption processes. Kasai et al. emphasize the necessity of integrating detailed adsorption kinetics, employing a linear driving force (LDF) model to accurately capture adsorption mechanisms. Gautier et al. focus on the thermal aspects of adsorption, underscoring the significant role of energy effects in heat-driven processes. Meanwhile, Haddadi et al. leverage advanced OpenFOAM solvers to achieve high spatial resolution, enabling detailed insights into flow dynamics and pressure distribution in packed beds. Despite these methodological differences, the utilization of three-dimensional (3D) models, as demonstrated by Haddadi et al., emerges as a pivotal advancement for achieving superior spatial accuracy and capturing complex interactions. This underscores the increasing relevance of 3D CFD modeling in advancing adsorption process simulations.

The adoption of 3D CFD modeling for HEX-As provides unparalleled advantages over traditional 1D or 2D approaches. By delivering detailed spatial resolution, 3D CFD captures intricate phenomena such as local flow distribution, localized heat transfer variations, and non-uniform adsorption rates. These capabilities are particularly essential for addressing non-ideal conditions, such as bypass zones, dead spaces, and irregular packing geometries. The reviewed studies illustrate how 3D CFD contributes to a deeper understanding of adsorption processes and is essential for the optimization of 3D design of HEX-As.

Moreover, 3D CFD enhances the predictive capabilities of adsorption models by incorporating spatial variations in flow, pressure, and thermal profiles. This approach facilitates more accurate simulation of real-world adsorption scenarios, offering a robust framework for tackling complex challenges in packed-column design and operation. Future efforts should aim to harmonize these advanced methodologies into unified, comprehensive models that can reliably simulate diverse adsorption systems under varying operating conditions.