Abstract

Heat pipe (HP) performance depends on several interacting physical phenomena, such as phase change and liquid transport within the wick. The latter is strongly affected by the permeability of the porous material, whose accurate evaluation is essential for a reliable prediction of the heat transfer capability. This work investigates the permeability of an additively manufactured aluminum wick by comparing two experimental and two numerical methods, using acetone and ethanol as working fluids. In the first experimental approach, the analytical capillary rise curve was fitted to data obtained through infrared thermography and by monitoring the fluid level decrease in an input reservoir. In the second, the mass flow rate through the samples was directly measured under an imposed pressure difference. Numerical simulations were performed using the Finite Volume Method in OpenFOAM and the Lattice Boltzmann Method in Palabos on computational domains reconstructed from microtomographic scans of a real wick. The permeability values, determined through the Darcy–Forchheimer formulation, were then used to estimate the maximum heat transport capability based on the capillary limit model for representative HP geometries. The results show that all four methods provide consistent permeability estimates, with deviations below in the porosity range relevant to real HPs.

1. Introduction

Heat pipes (HPs) are able to efficiently transport heat with very high effective thermal conductivity and without the need of external power. From their invention and first applications in the first half of the last century [1], their adoption has become widespread. Nowadays, HPs are used in consumer electronics such as personal computers and mobile phones, in military and space systems, in energy collection and storage, and in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems for civil and industrial buildings. A collection of significant references on these applications is available in [2], which also points to focused reviews on specific HP types and uses.

Among the available HP designs, the capillary type is widely used. In a capillary HP, the working fluid absorbs heat at the evaporator and vaporizes. Then, the vapor flows through the hollow core to the condenser, where it releases heat and condenses to liquid. Finally, the porous wick returns the liquid to the evaporator by capillary action. The outer boundary of the wick is sealed by an impermeable wall to prevent leakage. Despite their conceptual simplicity, the HP performance strongly depends on coupled physical phenomena, involving evaporation, condensation, and liquid transport in the wick. The thermophysical and capillary properties of the fluid, the solid material properties, their interfacial behavior, and the geometry govern the heat transfer. Once the working fluid, solid material, and operating conditions are defined, geometry remains the main degree of freedom, both in shape and size, and in other properties such as porosity, tortuosity, and permeability [3].

The solid material constituting an HP must be highly conductive, so copper, aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel are commonly used in conventional capillary HPs. However, the choice must also account for the operating range and compatibility with the working fluid, which spans from water to molten metals [4], and model development should reflect these constraints [5].

Porous structures are increasingly adopted in heat transfer applications [6,7,8,9], but they are also relevant in biomedical engineering [10] and chemical processing [11]. Multiple fabrication techniques are available, and recent efforts have focused on additive manufacturing (AM) [9,12]. Among all the AM techniques, powder bed fusion (PBF) enables the direct integration of porous regions in metallic components.

A key challenge when producing HP wicks with PBF is to match the porous properties of conventionally sintered wicks with a sufficiently small equivalent pore radius and suitable porosity, tortuosity, and permeability. In fact, PBF tends to produce larger and less uniform pores than sintering, which limits the ability to achieve the morphological characteristics required in many wick designs [13].

HPs operate correctly only if specific physical conditions are satisfied, including capillary action, vapor and liquid flow through a complex porous medium, and phase change. These conditions are commonly known as working limits, namely the capillary or circulation limit, the sonic limit, the entrainment limit, the viscous limit, and the boiling limit [2,14]. In many cases, during HP operation, the circulation limit is the first that intervenes to constrain performance.

The circulation limit follows from a pressure balance: the capillary pressure difference that drives the liquid in the wick, , must overcome the frictional pressure drop due to liquid, , and vapor, , motion, as well as the gravitational component along the HP longitudinal axis, . The latter depends on the HP orientation, so it can also assist operation when favorable. This pressure balance can be expressed as:

where:

In these equations, g is the gravity acceleration, is the liquid–vapor surface tension, and are the liquid and vapor densities, respectively, is the liquid dynamic viscosity, is the contact angle, is the average pore radius, K is the porous material permeability, F is the empirical Forchheimer inertial coefficient [15], is the vapor velocity, is the fluid superficial velocity, is the diameter of the HP core, and is the vapor friction factor.

In the gravitational term, is the effective HP length, representing the average distance traveled by the fluid, and is the angle with respect to the horizontal, within the range –90°. Negative values correspond to configurations where the evaporator is located above the condenser, meaning that the HP must operate in conditions adverse to gravity. Positive values indicate that the evaporator is below the condenser, meaning that the HP operation is gravity-assisted.

Equation (1) expresses the classical capillary limit condition for HPs, where the capillary pressure generated at the liquid–vapor interface balances the sum of gravitational, liquid, and vapor flow losses [3,16,17]. A Darcy–Forchheimer approach was applied to model the liquid pressure drop in the wick [15], while the vapor pressure drop was assumed negligible, as it is much smaller than the liquid and gravitational contributions under the operating conditions considered. In this study, the flow through the wick is fully laminar, so the inertial contribution in the Darcy–Forchheimer formulation is negligible, yielding permeability values practically identical to those from the classical Darcy law.

By setting the pressure balance in Equation (1) equal to zero and solving for the liquid superficial velocity, the maximum theoretical value of this velocity can be estimated. From it, the theoretical volume and mass flow rates during stable operation can be derived to calculate the maximum heat transfer rate that the HP can sustain. In actual operation, the HP carries only a fraction of this value, depending on fluid circulation and consequently on wick permeability.

Accurate information on the capillary pressure difference and permeability is therefore essential to estimate the potential HP performance. The first parameter can be determined from the equivalent pore radius and the contact angle formed among the liquid, solid, and vapor phases. The second parameter, which quantifies the overall resistance offered by the porous medium to fluid flow, can be measured experimentally or estimated numerically.

2. State of the Art

The accurate measurement of permeability is a key issue in a wide range of disciplines, as it determines the ability of porous materials to sustain fluid flow.

In the geoscience and oil&gas sectors, Krakowska and Madejski [18] combined laboratory testing with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to quantify flow through low-porosity rock samples, while Yang et al. [19] integrated computer-aided tomography (CT) imaging and numerical simulations to evaluate the evolution of permeability in early-age well cements under downhole conditions. More recently, Zhang et al. [20] employed pore-scale CFD to investigate the influence of hydrate saturation on sediment permeability, and Boumedjane et al. [21] used microfluidic chips to visualize flow and permeability variations caused by structural heterogeneity.

In engineered ceramics, Nickerson et al. [22] evaluated the permeability of sintered materials using 3D image-based modeling, whereas Song et al. [23] analyzed fluid flow through asymmetric microfiltration membranes via pore-scale simulations. These studies demonstrated how digital reconstruction and numerical flow modeling can link pore morphology to intrinsic permeability.

In the biomedical field, Chao et al. [24] investigated additively manufactured porous scaffolds, relating permeability to their mechanical properties, and Yuan et al. [25] analyzed anisotropic transport in fibrous biomaterials using tensor-based models. Gabrieli et al. [26] provided a methodological overview of permeability measurement techniques for bioceramic scaffolds, and Xu et al. [27] designed scaffolds with tailored pore architectures to achieve tunable permeability and mechanical strength.

Altogether, these works highlight how the control of pore geometry and connectivity is essential across different fields, from natural porous formations to synthetic scaffolds.

Therefore, permeability has been investigated through a wide variety of approaches, ranging from analytical correlations to advanced numerical and data-driven techniques. Tang and McDonough [28] proposed a theoretical model linking porosity and permeability by accounting for flow tortuosity and pore-size effects, while Lv et al. [29] experimentally characterized the transition between Darcy and Darcy–Forchheimer regimes in metallic foams with high pore density, showing the influence of pore-scale inertia. These works illustrate the complementary roles of theoretical modeling and laboratory measurements in interpreting transport mechanisms within porous media.

In recent years, CFD and Lattice Boltzmann methods (LBM) have become powerful tools to analyze pore-scale flow behavior and estimate permeability numerically. For instance, Otaru and Samuel [30] used CFD to resolve velocity and pressure fields inside microcellular structures, and Narváez et al. [31] performed one of the earliest quantitative validations of LBM-based permeability predictions. Eshghinejadfard et al. [32] applied the LBM to evaluate viscous flow in digitized porous samples, whereas Fu et al. [33] introduced a correction model to account for resolution effects in LBM-based permeability estimation. Feng et al. [34] combined microtomography and LBM simulations to assess the permeability of filter cakes, further demonstrating the synergy between imaging and numerical modeling.

In parallel, data-driven methods have recently been integrated with traditional numerical simulations to improve permeability prediction. Tian et al. [35] combined CFD results with machine learning algorithms to predict permeability from pore-structure descriptors, achieving good agreement with simulation data. Li et al. [36] developed a Discrete Element Method (DEM)–CFD coupling framework to determine anisotropic permeability in hydrate-bearing reservoirs, while Elrahmani et al. [37] used machine learning to describe permeability-impairment dynamics in evolving porous media. Shi et al. [38] applied convolutional neural networks to predict permeability in deformable materials, and Fogouang et al. [39] extended hybrid DEM–CFD approaches to investigate particle transport at the pore scale.

A comprehensive review of these experimental, numerical, and hybrid approaches was recently presented by Ranjbarzadeh and Sappa [40], who compared pore-scale imaging, CFD and LBM simulations, and data-driven correlations, highlighting current challenges in upscaling and the need for standardized permeability-assessment methodologies.

Despite the extensive research effort, accurately predicting permeability remains a challenging task due to the multiscale nature of the phenomenon and its dependence on additional structural properties such as tortuosity [41,42].

Among the different possible approaches reported in the literature, a classic way to evaluate the permeability of a porous medium for a given liquid is to solve the Darcy law (Equation (6)) or the Darcy–Forchheimer law (Equation (7)) [43], where is the pressure drop across the sample of length .

These relations connect the imposed pressure gradient to the measured mass flow rate of a fluid with known thermophysical properties across a sample of known dimensions [44]. Originally developed for flow in packed beds and porous rocks, this approach remains widely used for metallic and additively manufactured structures because of its simplicity and general applicability. It can be applied both experimentally, by measuring the mass flow rate through a real sample, and numerically, by imposing a flow rate and computing the corresponding pressure drop along the simulated domain. The first formulation (Darcy) considers only viscous effects, while the second (Darcy–Forchheimer) includes inertial contributions that become relevant when flow velocities increase or pore sizes are relatively large. For the low velocities typical of this work, the inertial term is negligible, and the two approaches return practically identical results.

This methodology has been widely employed in the literature to characterize different types of wicks and porous media. For instance, Zhang et al. [45] evaluated the permeability of sintered copper wicks used in cylindrical HPs through both capillary rise experiments and CFD simulations, while Deng et al. [46] analyzed sintered nickel and copper wicks for loop HPs under various pressure gradients to assess their capillary performance. Additionally, Jeon and Byon [47] used numerical simulations to study wicks with dual-height micro-post structures, highlighting the influence of meniscus curvature on the effective permeability. These studies demonstrate how CFD and related approaches can provide accurate permeability estimates and offer valuable insight into the flow behavior within complex porous geometries.

Nevertheless, only a limited number of studies have directly compared different experimental and numerical techniques for the same material, thus increasing the challenge of assessing consistency among methods. For instance, Agarwal et al. [48] proposed a two-step image-based approach to estimate permeability from 3D microstructural data, focusing on computational efficiency rather than direct comparison among methods, while Wagner et al. [49] conducted a systematic benchmark of several numerical techniques on regular porous structures, providing valuable insights but still limited to idealized geometries. A preliminary attempt in this direction was also carried out by the present authors [50], where a first comparison between experimental and numerical approaches was performed on a 3D-printed AlSi10 Mg porous medium. Building on that foundation, the present study provides a more comprehensive analysis, supported by a refined numerical approach and a broader dataset.

The scope and main element of novelty of the present work is therefore to evaluate the permeability of an aluminum porous wick, additively manufactured with PBF, by combining four complementary techniques: two experimental and two numerical. The experimental analyses include a capillary rise test and a direct mass flow rate measurement under imposed pressure gradients, while the numerical simulations are based on the Finite Volume Method (FVM) and LBM. The permeability values obtained from the different approaches are finally used to estimate the maximum heat transfer capability of representative HPs according to the capillary limit model, thereby highlighting the importance of a reliable permeability evaluation for accurate prediction of HP performance.

3. Physical and Virtual Samples of HP Wicks

The porous materials analyzed in this work, suitable for use as HP wicks, were additively manufactured by BEAMIT S.p.A (Fornovo di Taro, PR, Italy). The goal was to produce mechanically resistant porous structures with characteristics such as pore diameter distribution, permeability, tortuosity, and capillary performance as close as possible to those of conventional sintered materials. The selected alloy was AlSi10Mg, which is suitable for additive manufacturing and compatible with working fluids such as ammonia and acetone, typically used in HPs for space applications. The samples were printed with a GE Additive M2 Series 5 printer, with the printing direction orthogonal to the longitudinal axis. All samples were produced on a preheated build plate at and subjected to a stress-relief heat treatment at for after printing.

After a design-of-experiment analysis, the final printing parameters were those listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters used for the additive manufacturing of the AlSi10Mg wick samples.

Three types of physical samples were prepared for the experimental and numerical analyses:

- Samples for capillary rise tests were shaped as half-pipes, with height and wick thickness .

- Samples for mass flow rate tests were cylindrical, with height and diameter , including an external fillet for connection to the pipe of the experimental setup.

- The sample used to extract the domains for numerical simulations was a cylindrical HP, with length , internal diameter , and wick thickness .

Although identical printing parameters were applied, the different geometries caused slight porosity non-uniformities in the HP sample. These variations also introduced small differences among samples. In particular, the porosity was lower in regions close to the walls, where the wick structure was affected by the printing of the surrounding bulk regions. This non-uniformity is directly considered in the experimental tests, since the results derive from the analysis of the entire sample. For the numerical simulations, the same effect was exploited to extract virtual samples with different porosities. All estimated porosity values were between and .

The virtual samples used for the numerical analyses were extracted from the real HP sample by computer-aided microtomography (µCT) using a Phoenix-X-ray system (Waygate Technologies: Baker Hughes Digital Solutions GmbH, Hürth, Germany) operating at and . The µCT scan covered the entire HP section for a height of , with a voxel resolution of . From this scan, representative volume elements of were extracted.

These dimensions and resolution were chosen as an optimal compromise between having a sample statistically representative of of each region of the porous material, with dimensions at least 20 times larger than the average pore size in all directions, and keeping the computational cost of the simulations manageable.

The tomographic reconstruction was segmented into solid and void regions. The threshold for segmentation was finely adjusted to obtain a first virtual sample with a porosity of , consistent with the value experimentally measured for the corresponding part of the physical sample. Different regions within the HP cross-section were then identified to evaluate variations in porosity in the range –, in order to analyze the influence of porosity on the permeability estimated from the numerical simulations. An additional virtual sample with a porosity of was also generated by adjusting the binarization threshold, as this porosity value was not observed in the physical HP.

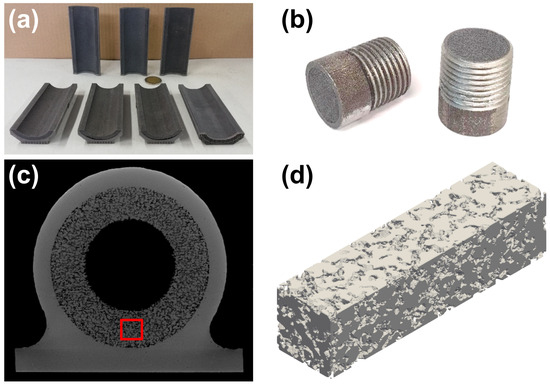

Figure 1 shows the samples manufactured for the capillary rise tests, the samples prepared for the mass flow rate tests, the section of the HP from which the µCT reconstruction with porosity was extracted, and the isosurface describing the solid boundary in the reconstructed domain for the same virtual sample.

Figure 1.

Samples and reconstructed domains analyzed in this study: (a) samples manufactured for the capillary rise tests; (b) samples prepared for the mass flow rate tests; (c) section of the HP from which the µCT reconstruction with porosity (highlighted in red) was extracted; (d) isosurface describing the solid boundary in the µCT reconstruction for the virtual sample with porosity .

4. Experimental Tests

This section describes the two experimental tests performed to determine the permeability from physical measurements: estimation from capillary rise tests and direct determination from flow rate tests. In the capillary rise tests, ethanol at ambient laboratory temperature, approximately , was used as the working fluid, while in the direct flow rate measurements, acetone at the same ambient conditions was employed. The thermophysical properties of both liquids were obtained from the NIST REFPROP database [51] at the corresponding test temperature. The overall uncertainty of the experimental methods was estimated at approximately .

4.1. Capillary Rise Test

The capillary rise test allows the determination of the capillary performance parameters of a wick structure [45]. In a dynamic capillary rise condition, a pressure equilibrium can be assumed at any time, where the capillary pressure is balanced by the sum of the hydrostatic and the frictional pressure drop contributions. This balance corresponds to a dynamic version of Equation (1) without the vapor frictional pressure drop. In this case, the three contributions can be expressed as:

where is the porosity, defined as the ratio between the void and total volume of the sample, is the liquid height as a function of time, and is the liquid rise rate. The surface tension acts between the liquid and the surrounding air, but its value is practically the same as for the liquid–vapor interface.

Equation (11) shows that the time evolution of the liquid height depends on the thermophysical and capillary properties of the liquid and on the porous medium characteristics.

During the test, the total porosity was measured by weighing the samples first after drying at for in a ventilated oven, and then after full saturation with ethanol, following the procedure by Jafari et al. [52]. The dry and saturated masses were measured with a digital laboratory scale with a resolution of . Each measurement was repeated three times. This procedure led to negligible differences in the obtained porosity values among the three repetitions.

Therefore, the only two remaining unknowns in Equation (11) were and K, whose optimal values were determined by numerical fitting of the experimental capillary rise curve, . Different techniques can be used for this purpose, producing different results depending on the selected method. Several of the methods described by Elkholy et al. [53] were preliminarily tested in this work. The final approach consisted of numerically integrating Equation (11) with a Finite Difference (FD) scheme and using the MATLAB R2022a [54] function fminsearch, based on the Nelder–Mead algorithm, to identify the values of and K that provided the best agreement between the analytical and experimental curves. This method yielded more consistent results than the alternatives.

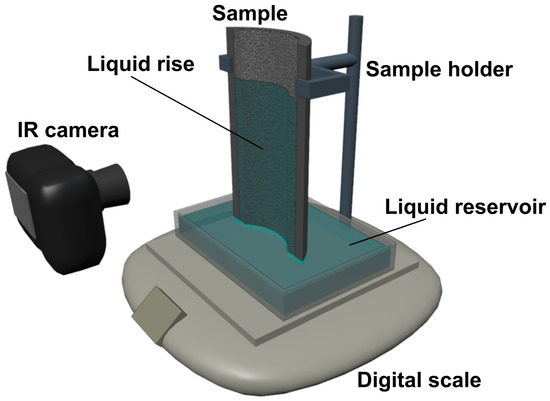

The setup used to analyze the time evolution of the capillary rise is shown in Figure 2. This setup enables the simultaneous use of two independent measurement methods, allowing cross-validation of the results.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup used for the capillary rise tests, showing the sample partially immersed in the liquid reservoir, the supporting frame, the infrared camera used to monitor the liquid front, and the digital scale used to record the absorbed mass over time.

In the first method, the height reached by the liquid within the wick was recorded using a FLIR T450sc infrared camera (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR, USA), which was used solely to track the liquid–vapor interface from the contrast between wet and dry regions, without requiring emissivity calibration. The wet region of the sample exhibited different emissivity from the dry aluminum and a cooling effect due to liquid evaporation. From the recorded height, the mass rise was calculated as the product of the liquid height, sample cross-section, porosity, and fluid density.

In the second method, the liquid level decrease in an input reservoir was recorded, with one end of the sample immersed in it. All tests were performed under stable laboratory conditions, with an ambient temperature of approximately , and a correction was applied to account for liquid evaporation from both the reservoir and the sample surface. The evaporation from the reservoir was measured before the tests, while the additional evaporation from the wetted sample was quantified by calibration, comparing the evaporation rate with and without the sample fully imbibed and then linearizing the contribution associated with the exposed sample surface.

4.2. Flow Rate Based Measurement

Since permeability is related to the resistance that a fluid experiences when flowing through a porous medium, a second approach to determine it consists in imposing a known pressure difference across a sample of known dimensions and measuring the resulting mass flow rate.

From the measured mass flow rate, together with the fluid density and the sample cross-section, the fluid superficial velocity can be determined, and Equation (6) can be solved to obtain the permeability.

Experimentally, the measurement of K was performed by placing a liquid reservoir at fixed heights, H, above the porous sample, specifically at , , and . The reservoir dimensions were selected to limit variations in the liquid free-surface level. After pseudo-steady conditions were reached, the liquid flow rate through the sample was measured.

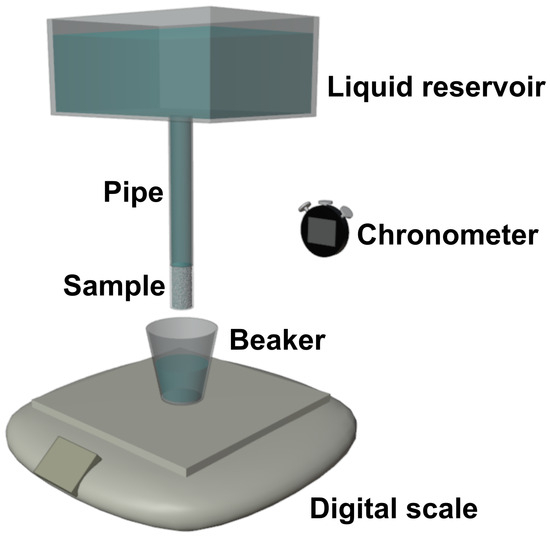

A schematic of the setup used for these measurements is shown in Figure 3. The reservoir and the sample were connected by a sealed pipe made of polyurethane, with an internal diameter of and a length of . As the flow was expected to remain laminar, a correction term was included in the calculations to account for the frictional pressure drop in the pipe, , which was computed as:

where and are the pipe diameter and length, respectively, and are the liquid density and velocity, respectively, and is the liquid friction factor, calculated as:

where is the Reynolds number.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup used for the direct flow rate measurement tests, showing the liquid reservoir connected to the porous sample through a vertical pipe, the beaker placed on a digital scale to collect the discharged liquid, and the chronometer used to record the measurement time.

5. Numerical Simulations

The numerical simulations aimed at estimating the wick permeability were performed with two different techniques: a FVM, using OpenFOAM version 11 [55], and a LBM, using Palabos version 2.3 [56,57]. For both numerical approaches, acetone at was selected as the working fluid, consistent with typical operating conditions of HPs. The thermophysical properties of acetone at were taken from the NIST REFPROP database [51].

5.1. Finite Volume Simulations

When using the FVM, the balance or conservation equations that include the variables of interest are written in differential form and then discretized. This process converts the differential equations in a continuous domain into systems of algebraic equations defined over a discretized domain composed of cells. For fluid dynamic applications, the governing equations are the Navier–Stokes equations, expressing the conservation of momentum, complemented by the continuity equation, expressing the conservation of mass [58].

5.1.1. Software Tool

Several numerical schemes, solution algorithms, and software tools are available to solve fluid dynamics problems. OpenFOAM was chosen for this study. In addition to being open source, it has provided excellent results in many research fields, including studies on porous media and on domains with complex geometries similar to that analyzed in this work [59,60,61,62,63,64]. Among the solvers included in OpenFOAM, simpleFoam was selected, as it is designed for steady-state calculations involving incompressible fluids.

5.1.2. Geometry, Mesh, Discretization Schemes, and Solution Algorithms

The geometry used for the FVM simulations was created by extracting the isosurface describing the solid–air interface from the binarized µCT reconstruction and exporting it as a stereolithography (STL) file. Two small reservoirs were added at the domain ends along the longitudinal direction to simplify the definition of the inlet and outlet boundary conditions and to facilitate permeability calculation during post-processing.

The domain was meshed using the OpenFOAM utilities blockMesh and snappyHexMesh. The first tool generated a structured background mesh, while the second selected all the cells enclosed by a specified 3D surface, namely the solid region described by the STL file, and adjusted the positions of the cell vertices so that the cell faces accurately followed the STL surface shape. The STL surface was imported without geometric smoothing or feature removal, and the mesh resolution was selected to ensure that all geometric features resolved by the µCT scan were preserved in the computational mesh. Since no local refinement regions were defined, the final mesh maintained good uniformity in the porous region. Only limited cell size variations appeared near the solid–fluid interface due to the snapping procedure, and the cells located close to the inlet and outlet boundaries were slightly larger.

Mesh independence was assessed by performing simulations with up to 18 M cells, and the difference in terms of permeability between the mesh with M cells and the finest mesh was around . Since this difference is close to the overall experimental uncertainty, the mesh with M cells was selected as the optimal compromise between accuracy and computational cost.

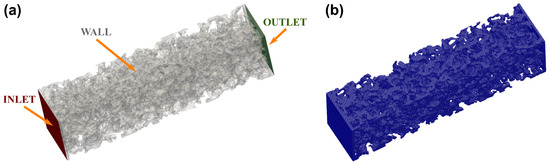

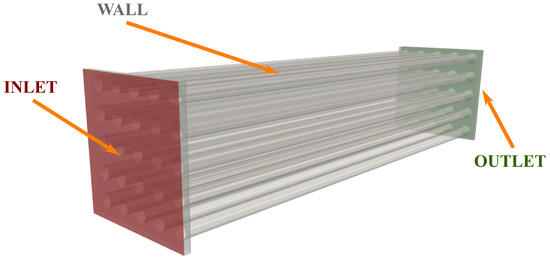

Figure 4 shows a representative example of the computational domain, boundaries, and final mesh used for the OpenFOAM simulations.

Figure 4.

Computational domain used for the CFD simulation for the case with porosity : (a) boundaries of the porous sample showing the inlet, outlet, and wall surfaces; (b) discretized mesh of the computational domain.

The main settings adopted for the discretization and solution of the equations are summarized below:

- Steady-state simulations were performed.

- The SIMPLE algorithm was applied to couple pressure and velocity, with one non-orthogonal corrector.

- The flow velocities involved were very low, as required for permeability estimation, so laminar flow was assumed.

- Second-order Gauss linear discretization schemes were used for all the terms.

- Pressure and velocity were relaxed with factors of .

- Residuals threshold for convergence was set to for both pressure and velocity.

- The geometric–algebraic multigrid solver (GAMG) was used for pressure.

- The stabilized preconditioned bi-conjugate gradient solver (PBiCGStab) was adopted for velocity.

5.1.3. Preliminary Simulations for Validation

Before simulating the domain of interest, the numerical setup was validated by simulating the flow in a single circular channel and in a bundle of parallel mini-channels. For the single channel, two sizes were tested: (1) diameter and length , and (2) diameter and length . For the bundle of mini-channels, each mini-channel had a diameter of , and the entire bundle was enclosed in a bounding box of . Figure 5 shows the computational domain for this configuration.

Figure 5.

Computational domain used for the FVM simulation of the mini-channels, showing the inlet, outlet, and wall surfaces of the modeled geometry.

These preliminary simulations were performed to compare the numerical results with the pressure-drop values predicted by the analytical models for straight circular channels, thereby assessing the validity of the simulation setup.

5.1.4. Boundary Conditions

A no-slip boundary condition, corresponding to zero relative velocity and zero pressure gradient, was applied to all solid–liquid interfaces, including the sides of the inlet and outlet reservoirs and the channel walls. At the outlet, a fixed pressure was imposed in all simulations, set to zero because incompressible flow was assumed. At the inlet, a velocity-based boundary condition was applied by prescribing a fixed uniform velocity, which was set in the range – in both the validation cases and the final simulations of the porous structures.

Since the inlet cross-sectional area was equivalent to the total cross-sectional area of the porous region, the inlet velocity was equal to the superficial velocity in the simulated wick.

Convergence was easily achieved in all configurations, with residuals below in less than 1000 iterations.

5.2. Lattice Boltzmann Simulations

This section provides an introduction to the LBM, the selected software and modeling choices, and the algorithm used to estimate the permeability from the simulation results.

5.2.1. Lattice Boltzmann Equations and Selected Software

The LBM is a mesoscale numerical approach based on the evolution of a discretized particle distribution function , which represents the probability of finding at time t a particle with velocity at location . The method solves a discrete Boltzmann equation on a regular lattice, where simulated particles move to neighboring nodes according to prescribed velocity directions and interact through elastic collisions that conserve momentum [32]. The discrete Boltzmann equation can therefore be written as:

where is the particle distribution function at location and time t along the ith lattice direction, is the collision operator, and is the local particle velocity. One of the simplest formulations of the collision operator in Equation (14) is the Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook (BGK) operator [31]:

where is the relaxation time and is the local equilibrium state.

The relaxation time in Equation (15) is related to the lattice kinematic viscosity, , as:

where the subscript indicates quantities expressed in lattice units, is the lattice sound speed, and is the lattice speed. To ensure numerical stability, must be greater than . In all simulations, was set to 1 to maintain stability and avoid nonphysical effects caused by higher relaxation frequencies, thus resulting in a lattice kinematic viscosity, , equal to .

The equilibrium distribution function in Equation (15) is expressed as:

where are the weights associated with the chosen lattice scheme.

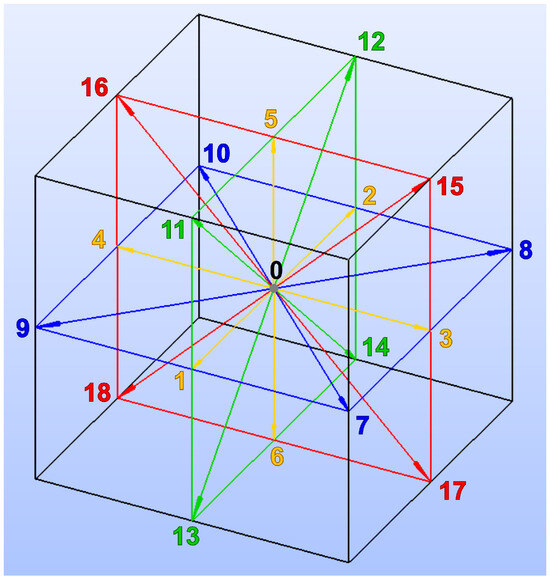

In this work, a standard D3Q19 LBM scheme was used, suitable for 3D simulations, with 19 discrete velocity directions (18 active and one zero), as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

D3Q19 lattice scheme used in the LBM simulations, showing the 19 velocity directions and their numbering convention.

At each time step, the macroscopic flow properties were reconstructed from the particle distribution function as follows:

The described equations, combined with suitable boundary conditions, form the lattice–BGK framework used to simulate fluid flow.

The open-source code Palabos was selected to perform the simulations.

5.2.2. Setup of the Lattice Boltzmann Simulations

The µCT reconstruction of the porous material was processed following common guidelines for µCT segmentation in porous materials, including threshold selection and the treatment of partial-volume effects [65,66]. In particular, the dataset was first binarized using ImageJ version 1.54 [67], with the threshold adjusted to match the experimentally measured porosity. Each voxel in the domain was therefore labeled as either pore or solid material. A MATLAB script was then used to convert the binarized 3D voxel matrix into a .dat file, where zeros represented fluid voxels corresponding to pores, ones denoted interface or bounce-back voxels corresponding to solid regions adjacent to one or more pores, and twos indicated voxels belonging to the bulk solid. More specifically, a voxel completely surrounded by fluid voxels in all eighteen lattice directions was classified as a pure fluid voxel, while a solid voxel surrounded only by solid voxels was a pure solid. If a solid voxel had at least one neighboring fluid voxel in the eighteen lattice directions, it was identified as a bounce-back voxel. A standard full-way bounce-back scheme was used to impose the no-slip condition at these solid boundaries. As the geometry derives directly from the voxelized µCT data, the resulting staircased pore walls are acknowledged as a known source of uncertainty, likely leading to slightly larger virtual pores and thus to higher permeability. The stream and collision dynamics described above applied to fluid voxels, while a no-dynamics condition was imposed for solid voxels. In bounce-back voxels, the particle distributions reversed their momentum, providing a simple and numerically robust boundary condition [68]. A pressure gradient between two opposite domain faces was imposed to drive the flow.

The permeability in lattice units was again calculated from the simulation results using Darcy’s law for single-phase 1D flow:

where is the average fluid velocity and is the pressure gradient over the length . The subscript indicates quantities expressed in lattice units, as opposed to the corresponding physical variables.

Palabos operates in dimensionless units; therefore, conversion coefficients are required to relate the lattice-unit results to physical quantities. The spatial conversion coefficient corresponds to the voxel size from the µCT scans, equal to , while the time conversion coefficient, , is computed as:

where is the physical kinematic viscosity.

For the pressure boundary condition, the physical pressure difference is scaled by the fluid density. The coefficients and are then used to convert it into lattice units. The physical velocity field is recovered by multiplying the lattice velocity by , and the permeability in physical units is obtained by multiplying the lattice result by .

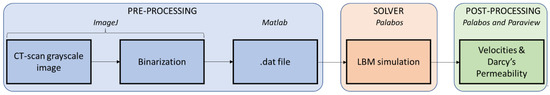

The workflow for an LBM simulation, conceptually similar to that used for the FVM simulations, is summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Workflow adopted for the LBM simulations, showing the pre-processing of the µCT-scan images in ImageJ and MATLAB, the LBM computation performed in Palabos, and the post-processing in Palabos and ParaView for the extraction of velocity fields and Darcy’s permeability.

5.2.3. Preliminary Simulations for Validation

As for the FVM, preliminary simulations were performed on the same domains to validate this second numerical setup. First, the permeability of a single channel with a diameter of was computed and compared with the analytical results. Then, a tube-bundle configuration was simulated, and the obtained results were compared with the FVM predictions. For all cases, different pressure gradients were applied to verify that the resulting permeability value was independent of the pressure magnitude.

6. Results and Discussion

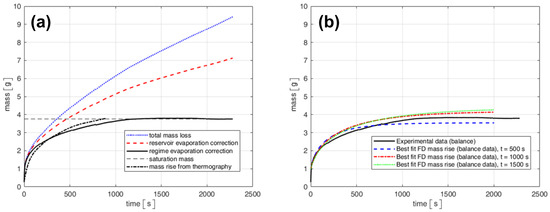

Figure 8 summarizes the main outcomes of the experimental analyses. In particular, panel (a) shows the capillary mass rise curves obtained with the two experimental approaches, highlighting the effect of the correction steps and the differences between the infrared thermography and the scale measurements. Panel (b) reports the experimental mass rise transient together with the curve resulting from the FD integration of Equation (11), using the optimal values of and K obtained from the fitting procedure. To better illustrate the sensitivity of the fitting, three FD curves are displayed, since the best-fit values differ depending on the fitting time interval. When using , , and of the capillary-rise curve, the estimated values are , , and for , and , , and for K, respectively. The fitted values reach stability with respect to the fitting duration, since the difference between and is much smaller than that between and . Furthermore, the mass rise at the end of the transient, estimated from the fitted curves, differs by 5– from the corrected experimental value. However, as the fitting interval increases, the influence of spurious effects such as evaporation becomes larger, altering the slope of the mass rise curve and leading to an underestimation of the permeability. In contrast, the first are dominated by capillary driven dynamics and are therefore much less affected by evaporation and temperature fluctuations. Consequently, the capillary rise results alone do not allow identifying a single most reliable value. Nevertheless, as discussed later, comparisons with the other techniques indicate that the results obtained with the interval are the most accurate. In all cases, the estimated permeability has the same order of magnitude, allowing at least preliminary considerations about the potential heat transfer performance of the heat pipe.

Figure 8.

Experimental results of the capillary-rise tests. (a) Mass–time curves obtained with the two experimental approaches, showing the total mass loss (blue dotted line), the mass loss after correction for the reservoir evaporation (red dashed line), the mass loss after taking into account also the regime evaporation correction (black solid line), the saturation mass (black dashed line), and the mass rise derived from thermography (black dash-dotted line). (b) Comparison between the experimental mass rise data measured by the balance (black solid line) and the FD solutions of Equation (11), obtained using different fitting intervals: (blue dashed line), (red dash-dotted line), and (green dotted line).

For the direct flow rate measurement tests, Table 2 summarizes the results obtained by applying three different pressure differences across the sample, calculated as the difference between outlet and inlet pressures. The estimated permeability shows a negligible dependence on the imposed pressure difference, with an average value of . This value is in very good agreement with that obtained from the capillary rise tests using the fitting interval.

Table 2.

Permeability values obtained with the direct flow rate measurement tests.

The permeability values obtained in the experimental tests are also consistent with the range reported by Gotoh et al. [69].

Switching to the numerical analyses, the preliminary validation simulations returned results in excellent agreement with the analytical correlations for the pressure drop across both the single channel and the tube bundle under laminar flow conditions. In the FVM simulations, when varying the inlet velocity, the average deviation from the analytical solution was for the single channel and for the array of mini-channels. In the LBM simulations, the deviation was for the single channel and for the tube bundle, confirming the overall reliability of both numerical setups.

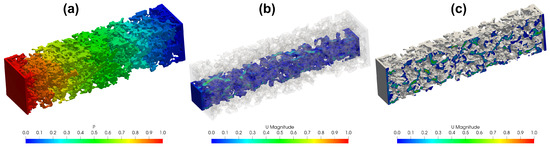

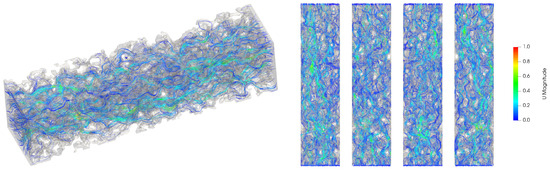

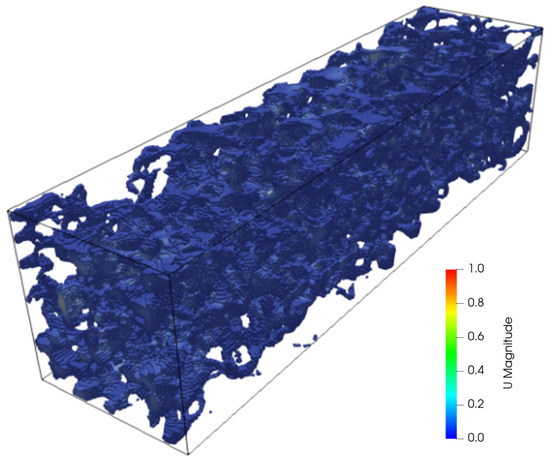

Focusing on the virtual samples of interest, the pressure and velocity fields within the porous domain were computed, and the corresponding permeability was evaluated as described in the previous sections. Examples of these results are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 for the FVM simulations (pressure, velocity, and streamlines) and in Figure 11 for the LBM simulations. The color bars in the figures are normalized with respect to the maximum value of each variable, emphasizing the qualitative flow behavior, which remains consistent across all simulated cases.

Figure 9.

Examples of the FVM simulation results: (a) normalized pressure field in the porous domain; (b) normalized velocity magnitude field in a portion of the domain; (c) normalized velocity magnitude field on an internal slice of the domain. Both pressure and velocity fields are normalized by their respective maximum values.

Figure 10.

Flow streamlines obtained from the FVM simulations, colored according to the velocity magnitude within the porous domain, normalized by its maximum value. The left image displays a 3D view of the flow field, while the right panel presents side views of the velocity distribution.

Figure 11.

Example of the LBM simulation results, showing the velocity magnitude within the porous domain normalized by its maximum value.

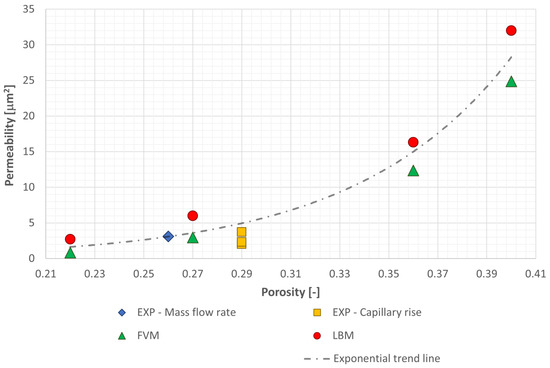

As shown in Figure 9a, the pressure distribution along the longitudinal direction of the domain is uniform, without regions of abrupt variation. This confirms the structural homogeneity of the sample. The velocity fields in panels (b) and (c) of the same figure, and in Figure 11, highlight the internal geometric complexity of the domain and, consequently, of the flow field. This behavior is even clearer in the streamlines plotted in Figure 10, which reveal winding and tortuous fluid paths. Such flow complexity results in significant domain tortuosity. This, in turn, directly influences the permeability. However, the streamline patterns remain uniform throughout the domain, confirming the structural homogeneity and representativeness of the virtual sample. Focusing on the permeability values, Table 3 summarizes all the experimental and numerical results, ordered by sample porosity. The same data are plotted in Figure 12, where an exponential trend curve is fitted to the FVM, LBM, and experimental mass flow rate results.

Table 3.

Permeability values from all the different measurement and numerical estimations.

Figure 12.

Permeability values as a function of porosity obtained from the experimental and numerical analyses. Blue diamonds represent the experimental results from the mass flow rate tests, yellow squares those from the capillary rise tests, green triangles the numerical results from the FVM simulations, and red circles the results from the LBM simulations. The dashed gray line indicates an exponential trend highlighting the overall correlation between permeability and porosity.

For the virtual sample with , the permeability obtained from the FVM simulations is (standard deviation ) when using the Darcy approach at different inlet velocities, and when applying the Darcy–Forchheimer formulation, obtained by quadratic fitting of the pressure drop versus superficial velocity. The difference between the two values is , which falls within the experimental uncertainty. For the same virtual sample, the LBM simulations yield a permeability of .

For porosity values in the range –, the permeability ranges between – in the FVM simulations and – in the LBM simulations. The results from both methods align well with an exponential trend curve, confirming the expected dependence of permeability on porosity.

The permeability from the FVM for is is in excellent agreement with the experimental results obtained at similar porosities. Conversely, the LBM values are higher than those from the FVM at low porosity, while the difference decreases below at higher porosity. This discrepancy may arise from the different geometric representations: in the FVM, the external faces of the fluid cells adapt to the isosurface extracted from the µCT data, whereas in the LBM the cubic lattice produces a jagged boundary, slightly altering the effective channel dimensions and leading to higher permeability estimates.

Overall, in the permeability range of interest for real HP wicks, all methods provide consistent results with comparable values. It is also noteworthy that the numerical simulations are computationally efficient, requiring only 2– on a standard laptop, with file sizes around for both the LBM and the FVM.

Given that, as previously discussed, all results align closely with exponential trends, an exponential fit was derived from the experimental (mass flow rate) and numerical data to express the permeability as a function of the porosity. This correlation was obtained directly from the present dataset, resulting in Equation (22):

The resulting coefficient of determination is , confirming the reliability of the fitting over the porosity range presented in Table 3, namely –.

Based on this correlation, the maximum heat transfer rate according to the capillary limit [14] was estimated for representative HP configurations. The permeability values were calculated using Equation (22) to predict K as a function of . The selected HPs, characterized by the parameters summarized in Table 4, were analyzed to evaluate the separate effects of wick cross sectional area, HP length, and orientation angle, while all other parameters were kept constant. In particular, the fluid thermophysical properties considered for the evaluation of the maximum heat transfer rate were those of acetone at , obtained from the NIST REFPROP database.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the HPs used to investigate the effect of the permeability on the maximum heat transfer rate.

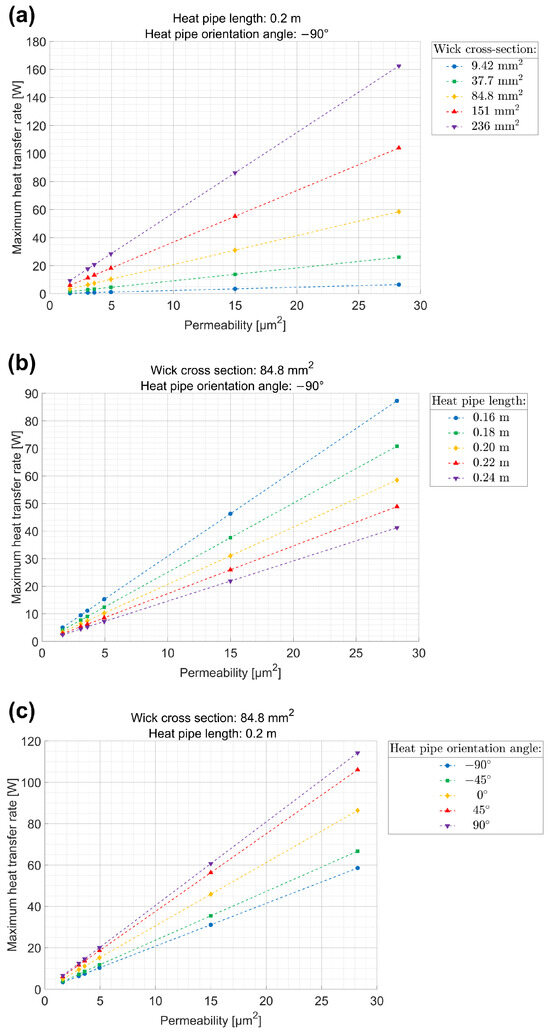

The obtained results are presented in Figure 13, which shows the maximum heat transfer rate as a function of permeability for the representative HPs described in Table 4. Panel (a) refers to varying wick cross sectional area at fixed HP length and orientation angle, panel (b) to varying HP length at fixed wick cross section and orientation angle, and panel (c) to varying orientation angle at fixed wick cross section and HP length.

Figure 13.

Maximum heat transfer rate as a function of permeability for the representative HPs described in Table 4: (a) Effect of the wick cross sectional area for a fixed HP length of and an orientation angle of . (b) Effect of the HP length for a fixed wick cross section of and an orientation angle of . (c) Effect of the HP orientation angle for a fixed wick cross section of and a fixed length of . The dashed lines connect the data points corresponding to the same geometric or operating condition indicated in each legend.

Figure 13a shows that the maximum heat transfer rate increases markedly with permeability, and the effect is stronger for larger wick cross-sectional areas. This indicates that for designs with larger wick cross sections, the uncertainty in permeability estimation has a greater influence on performance prediction. Figure 13b shows that shorter HPs achieve higher maximum heat transfer rates, while longer ones are more limited by capillary pumping. Nonetheless, in all configurations, the sensitivity to permeability remains significant, confirming the importance of reliable permeability data, particularly for compact devices. Figure 13c illustrates that the HP orientation angle also plays a dominant role: the maximum heat transfer rate is lowest in the unfavorable vertical orientation () and highest in the favorable one (90). However, the dependence on wick permeability persists across all inclinations, highlighting that permeability estimation remains a key factor under different operating orientations.

Overall, these results clearly demonstrate that an accurate estimation of wick permeability is essential for a correct prediction of the capillary limit and, consequently, of the HP performance.

7. Conclusions

In this work, four different methods, two experimental and two numerical, were used to determine the permeability of a metallic porous medium additively manufactured by PBF and designed for use as a wick in capillary HPs.

The two experimental techniques were based on the direct measurement of the liquid mass flow rate through the sample and on the analysis of the capillary rise curve obtained by infrared thermography. The permeability measured from the flow rate proved to be robust, also with respect to variations in the imposed pressure difference. The capillary rise test, instead, was more sensitive to the experimental conditions, mainly due to the volatility of the working fluid. Therefore, in this case, accurate modeling of evaporation was required to obtain reliable quantitative results. Nevertheless, both techniques provided consistent and realistic estimates.

The numerical simulations, performed with the FVM and LBM, were first validated against benchmark cases with known analytical solutions and then applied to the real wick geometry. The permeability values obtained with the FVM were in very good agreement with the experimental ones, while those from the LBM were slightly higher but still within a difference for the porosity values relevant to real wicks.

The experimental and numerical results were then combined to derive an exponential permeability–porosity correlation, covering the porosity range relevant to the additively manufactured wicks investigated in this study. This correlation was used to estimate the maximum heat transfer rate according to the capillary limit model for representative HP configurations, further highlighting the importance of an accurate permeability estimation in the wick design process.

Therefore, all experimental and numerical approaches provided permeability values consistent with each other and reliable for the preliminary analysis and modeling of HPs, particularly for evaluating the capillary limit. The numerical techniques, especially the FVM, offered results in good agreement with the experiments, thus representing a useful complement to support the characterization of existing wicks and assist in the design of new structures with specific properties, although their broader validation would require the analysis of additional materials and geometries.

In conclusion, numerical modeling proved to be a suitable approach for exploring different wick geometries and assessing their performance before manufacturing real samples, and the permeability–porosity correlation derived in this work provides additional support for the selection and optimization of porous wicks in different HP applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., L.V., G.B., R.C. and S.F.; data curation, M.G., L.V., G.B. and R.C.; formal analysis: M.G., L.V. and G.B.; funding acquisition: M.G. and S.F.; investigation: M.G., L.V. and G.B.; project administration: M.G., E.C. and S.F.; software: M.G., L.V., G.B. and R.C.; supervision: M.G., E.C. and S.F.; validation: M.G., L.V. and G.B.; visualization: M.G., L.V., G.B. and R.C.; writing—original draft, M.G., L.V., G.B. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, M.G., L.V., G.B., R.C., E.C. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Space Agency through contract agreement No. 4000134448/21/NL/FGL (ARTES Advanced Technology—Activity Reference 4D.069—Thermally Enhanced Power Unit Housing using Embedded Two-Phase Technology) for the project “Heat Pipe Solutions for High Power Systems” (HPS2).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank the late Alfonso Niro, whose activity as a professor and an engineer provided essential guidance and inspiration throughout the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zohuri, B. Basic principles of heat pipes and history. In Heat Pipe Design and Technology: Modern Applications for Practical Thermal Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R.; Guilizzoni, M. Modeling of Conventional Heat Pipes with Capillary Wicks: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhara, H.; Reay, D.; McGlen, R.; Kew, P.; McDonough, J. Heat Pipes: Theory, Design and Applications; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, K. Heat pipe for aerospace applications—An overview. J. Electron. Cool. Therm. Control 2015, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Gallazzi, L.; Iazurlo, R.; Marcovati, M.; Guilizzoni, M. A multi-node lumped parameter model including gravity and real gas effects for steady and transient analysis of heat pipes. Fluids 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, P. Multiphase flow and heat transfer in porous media. In Advances in Heat Transfer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; Volume 30, pp. 93–196. [Google Scholar]

- Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.Y.; Baig, M.A.A. Heat transfer in porous media: A mini review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 24, 1318–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wan, Z. Heat transfer performance of a heat pipe with sintered stainless-steel fiber wick. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 45, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambati, G.; Vitali, L.; Guilizzoni, M.; Caplanne, E.; Niro, A.; Foletti, S. Comparative thermal analysis, design, and structural assessment of lattice-based additively manufactured heat pipes for space applications. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 8221–8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanafer, K.; Vafai, K. The role of porous media in biomedical engineering as related to magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery. Heat Mass Transf. 2006, 42, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Peyvandi, K. Role of metallic porous media and surfactant on kinetics of methane hydrate formation and capacity of gas storage. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 181, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Gain, A.K.; Ding, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Fu, Y. A review on metallic porous materials: Pore formation, mechanical properties, and their applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 95, 2641–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, P.; Mikielewicz, D. Additive manufacturing as a solution to challenges associated with heat pipe production. Materials 2022, 15, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, P.; Čaja, A.; Malcho, M. Mathematical model for heat transfer limitations of heat pipe. Math. Comput. Model. 2013, 57, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, W. Darcy, Forchheimer, Brinkman and Richards: Classical hydromechanical equations and their significance in the light of the TPM. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2022, 92, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.P. An Introduction to Heat Pipes. Modeling, Testing, and Applications; Wiley Series in Thermal Management of Microelectronic and Electronic Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Faghri, A. Heat Pipe Science and Technology; Global Digital Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowska, P.; Madejski, P. Research on fluid flow and permeability in low porous rock sample using laboratory and computational techniques. Energies 2019, 12, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Kuru, E.; Gingras, M.; Iremonger, S. CT-CFD integrated investigation into porosity and permeability of neat early-age well cement at downhole condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 205, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Yin, Z. An investigation on the permeability of hydrate-bearing sediments based on pore-scale CFD simulation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 192, 122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumedjane, M.; Al-Maamari, R.S.; Rabbani, A.; Karimi, M. Real-time pore-scale investigation of the effects of uniform, random, and heterogenous porous structures on intrinsic permeability using two-dimensional microfluidic chips. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 5700–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, S.; Shu, Y.; Zhong, D.; Könke, C.; Tandia, A. Permeability of porous ceramics by X-ray CT image analysis. Acta Mater. 2019, 172, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Rong, L.; Dong, K.; Liu, X.; Le-Clech, P.; Shen, Y. Pore-scale numerical study of intrinsic permeability for fluid flow through asymmetric ceramic microfiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 642, 119920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Jiao, C.; Liang, H.; Xie, D.; Shen, L.; Liu, Z. Analysis of mechanical properties and permeability of trabecular-like porous scaffold by additive manufacturing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 779854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Shen, L.; Dini, D. Porosity-permeability tensor relationship of closely and randomly packed fibrous biomaterials and biological tissues: Application to the brain white matter. Acta Biomater. 2024, 173, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrieli, R.; Schiavi, A.; Baino, F. Determining the permeability of porous bioceramic scaffolds: Significance, overview of current methods and challenges ahead. Materials 2024, 17, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Ren, L. Tailored Pore Architectures in Ti6Al4V Bone Scaffolds for Tunable Permeability and Mechanical Performance. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2500070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; McDonough, J. A theoretical model for the porosity-permeability relationship. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 103, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Li, W.; Du, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, B. Experimental investigation of permeability and Darcy-Forchheimer flow transition in metal foam with high pore density. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2024, 154, 111149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaru, A.; Samuel, M. Pore-level CFD investigation of velocity and pressure dispositions in microcellular structures. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 046516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, A.; Zauner, T.; Raischel, F.; Hilfer, R.; Harting, J. Quantitative analysis of numerical estimates for the permeability of porous media fromlattice-Boltzmann simulations. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2010, 2010, P11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghinejadfard, A.; Daróczy, L.; Janiga, G.; Thévenin, D. Calculation of the permeability in porous media using the lattice Boltzmann method. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2016, 62, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Owen, D.R.J.; Li, C. Resolution effect: An error correction model for intrinsic permeability of porous media estimated from lattice boltzmann method. Transp. Porous Media 2020, 132, 627–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Fan, Y.; Dong, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, R. Permeability estimation in filter cake based on X-ray microtomography and Lattice Boltzmann method. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Qi, C.; Sun, Y.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Pham, B.T. Permeability prediction of porous media using a combination of computational fluid dynamics and hybrid machine learning methods. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 3455–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Han, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Huang, F. Numerical Determination of Anisotropic Permeability for Unconsolidated Hydrate Reservoir: A DEM–CFD Coupling Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrahmani, A.; Al-Raoush, R.I.; Ayari, M.A. Modeling of permeability impairment dynamics in porous media: A machine learning approach. Powder Technol. 2024, 433, 119272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Jin, G.; Yan, W.; Xing, H. Permeability estimation for deformable porous media with convolutional neural network. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2024, 34, 2943–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogouang, L.M.; André, L.; Soulaine, C. Particulate transport in porous media at pore-scale. Part 1: Unresolved-resolved four-way coupling CFD-DEM. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 521, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbarzadeh, R.; Sappa, G. Numerical and experimental study of fluid flow and heat transfer in porous media: A review article. Energies 2025, 18, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, H.P.; Maes, J.; Geiger, S. Upscaling the porosity–permeability relationship of a microporous carbonate for Darcy-scale flow with machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakoso, A.T.; Basri, H.; Adanta, D.; Yani, I.; Ammarullah, M.I.; Akbar, I.; Ghazali, F.A.; Syahrom, A.; Kamarul, T. The effect of tortuosity on permeability of porous scaffold. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, R.; Pillai, K.M.; Varanasi, P.P. Darcy’s law-based models for liquid absorption in polymer wicks. AIChE J. 2007, 53, 2769–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Tang, Y.; Huang, G.; Lu, L.; Yuan, D. Characterization of capillary performance of composite wicks for two-phase heat transfer devices. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 56, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lian, L.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.Q. The heat transfer capability prediction of heat pipes based on capillary rise test of wicks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 164, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Liang, D.; Tang, Y.; Peng, J.; Han, X.; Pan, M. Evaluation of capillary performance of sintered porous wicks for loop heat pipe. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2013, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Byon, C. Permeability of dual-height micro-post wicks for heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 115, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.; Alpak, F.O.; Koelman, J.V.A. Permeability from 3D porous media images: A fast two-step approach. Transp. Porous Media 2018, 124, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Eggenweiler, E.; Weinhardt, F.; Trivedi, Z.; Krach, D.; Lohrmann, C.; Jain, K.; Karadimitriou, N.; Bringedal, C.; Voland, P.; et al. Permeability estimation of regular porous structures: A benchmark for comparison of methods. Transp. Porous Media 2021, 138, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, L.; Brambati, G.; Caruana, R.; Foletti, S.; Guilizzoni, M.; Niro, A. Permeability measurement of a 3D-printed AlSi10Mg porous medium: Comparisons between first results with different experimental and numerical techniques. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2685, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Database (REFPROP); National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/srd/refprop/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Jafari, D.; Wits, W.W.; Geurts, B.J. Metal 3D-printed wick structures for heat pipe application: Capillary performance analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 143, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, A.; Durfee, J.; Mooney, J.; Robinson, A.; Kempers, R. A rate-of-rise facility for measuring properties of wick structures. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 045301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATLAB. MathWorks. 2025. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- OpenFOAM. The OpenFOAM Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://openfoam.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Latt, J.; Malaspinas, O.; Kontaxakis, D.; Parmigiani, A.; Lagrava, D.; Brogi, F.; Belgacem, M.B.; Thorimbert, Y.; Leclaire, S.; Li, S.; et al. Palabos: Parallel lattice Boltzmann solver. Comput. Math. Appl. 2021, 81, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palabos. Université de Géneve. 2025. Available online: https://palabos.unige.ch/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M.; Street, R.L. Finite volume methods. In Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Guilizzoni, M.; Santini, M.; Lorenzi, M.; Knisel, V.; Fest-Santini, S. Micro computed tomography and CFD simulation of drop deposition on gas diffusion layers. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 547, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, A.; Montenegro, G.; Tabor, G.; Wears, M. CFD characterization of flow regimes inside open cell foam substrates. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2014, 50, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, A.; Montenegro, G.; Onorati, A.; Tabor, G. CFD characterization of pressure drop and heat transfer inside porous substrates. Energy Procedia 2015, 81, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.P.; Tomenchok, K.; Olson, T.; Ellis, B.R. Reducing user bias in X-ray computed tomography-derived rock parameters through image filtering. Transp. Porous Media 2021, 140, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Marocco, L.; De Antonellis, S.; Guilizzoni, M. Effect of the plates geometry on the performance of a cross-flow recuperator for indirect evaporative cooling systems. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2766, 012177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, M.; Caruana, R.; Di Caterino, A.; Fustinoni, D.; Gramazio, P.; Vitali, L.; Guilizzoni, M. Morphology and Solidity Optimization of Freeform Surface Turbulators for Heat Exchangers Equipped with Narrow Channels. Energies 2025, 18, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenschild, D.; Sheppard, A.P. X-ray imaging and analysis techniques for quantifying pore-scale structure and processes in subsurface porous medium systems. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, S.; Sheppard, A.; Brown, K.; Wildenschild, D. Image processing of multiphase images obtained via X-ray microtomography: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 3615–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Image Processing and Analysis in Java (IMAGEJ). 2025. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Zou, Q.; He, X. On pressure and velocity boundary conditions for the lattice Boltzmann BGK model. Phys. Fluids 1997, 9, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, R.; Furst, B.I.; Roberts, S.N.; Cappucci, S.; Daimaru, T.; Sunada, E.T. Experimental and analytical investigations of AlSi10Mg, stainless steel, Inconel 625 and Ti-6Al-4V porous materials printed via powder bed fusion. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).