The Evolution and Influence of Pore-Fluid Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter in the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation, Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

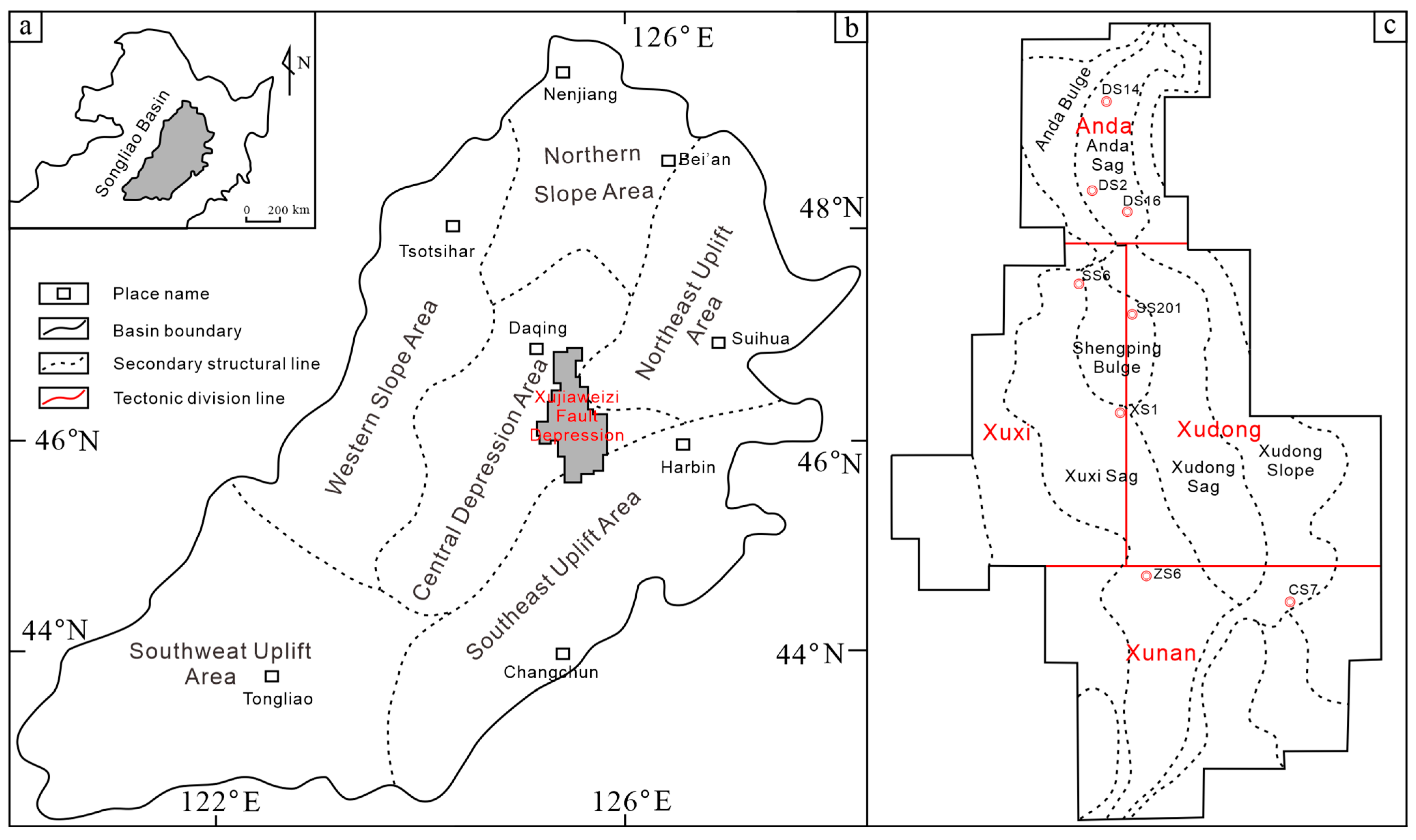

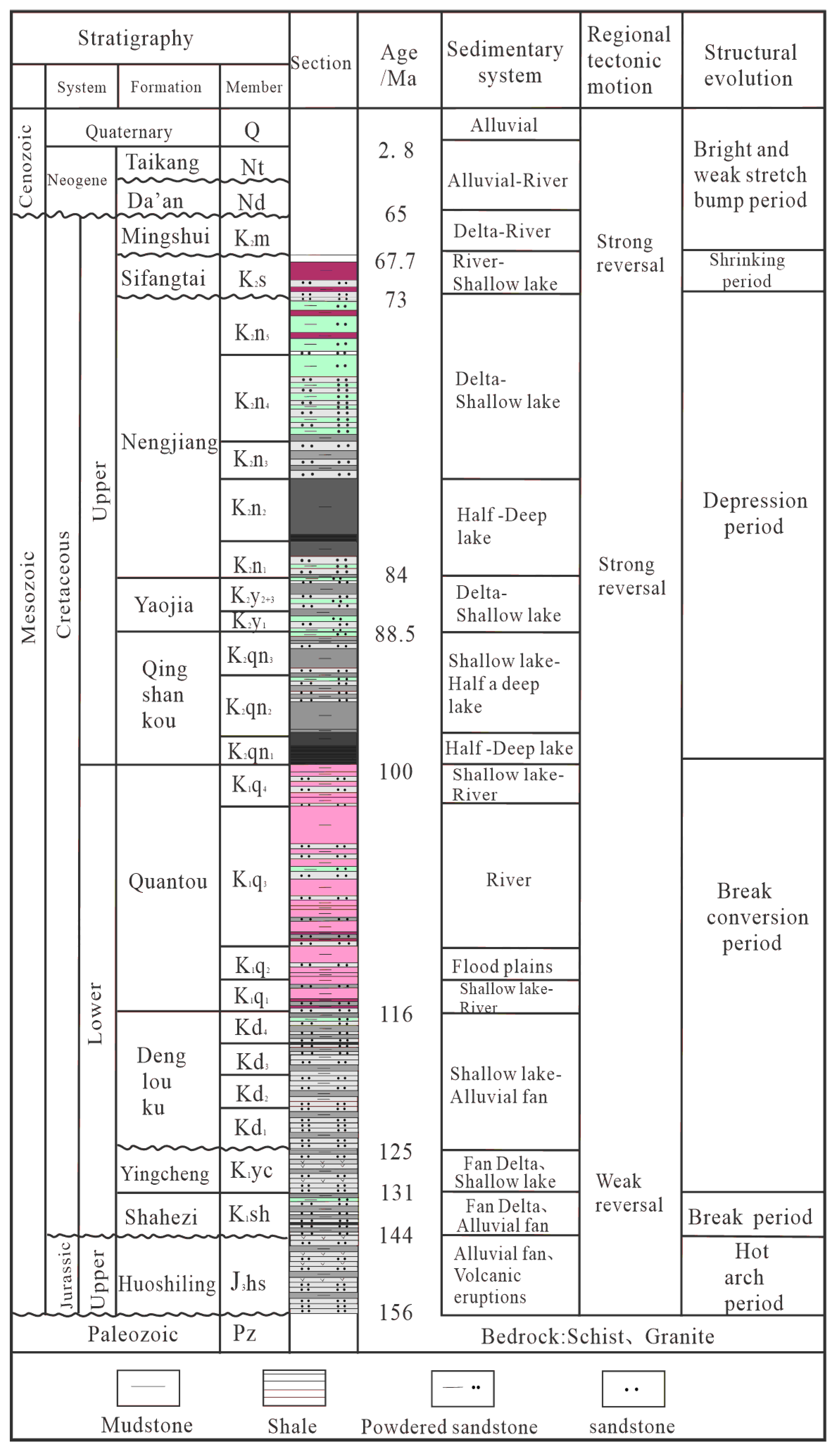

2. Geological Background

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Simulation Experiment of Thermal Hydrocarbon Generation

3.2. Microthermometry of Fluid Inclusions

3.3. Basin Modeling

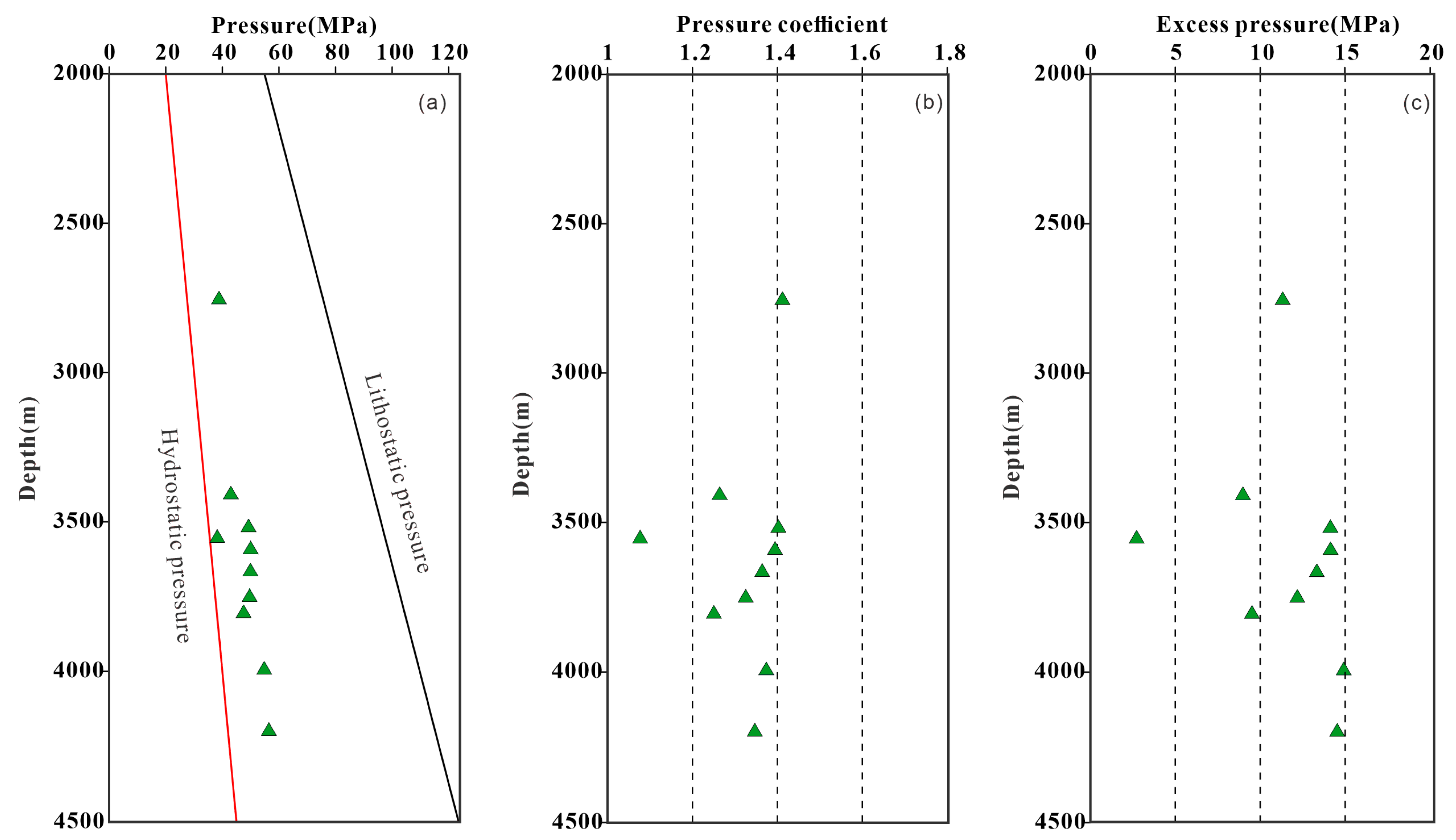

4. Current Pressure System and Causes of Abnormal Pressure

4.1. The Present Pressure System

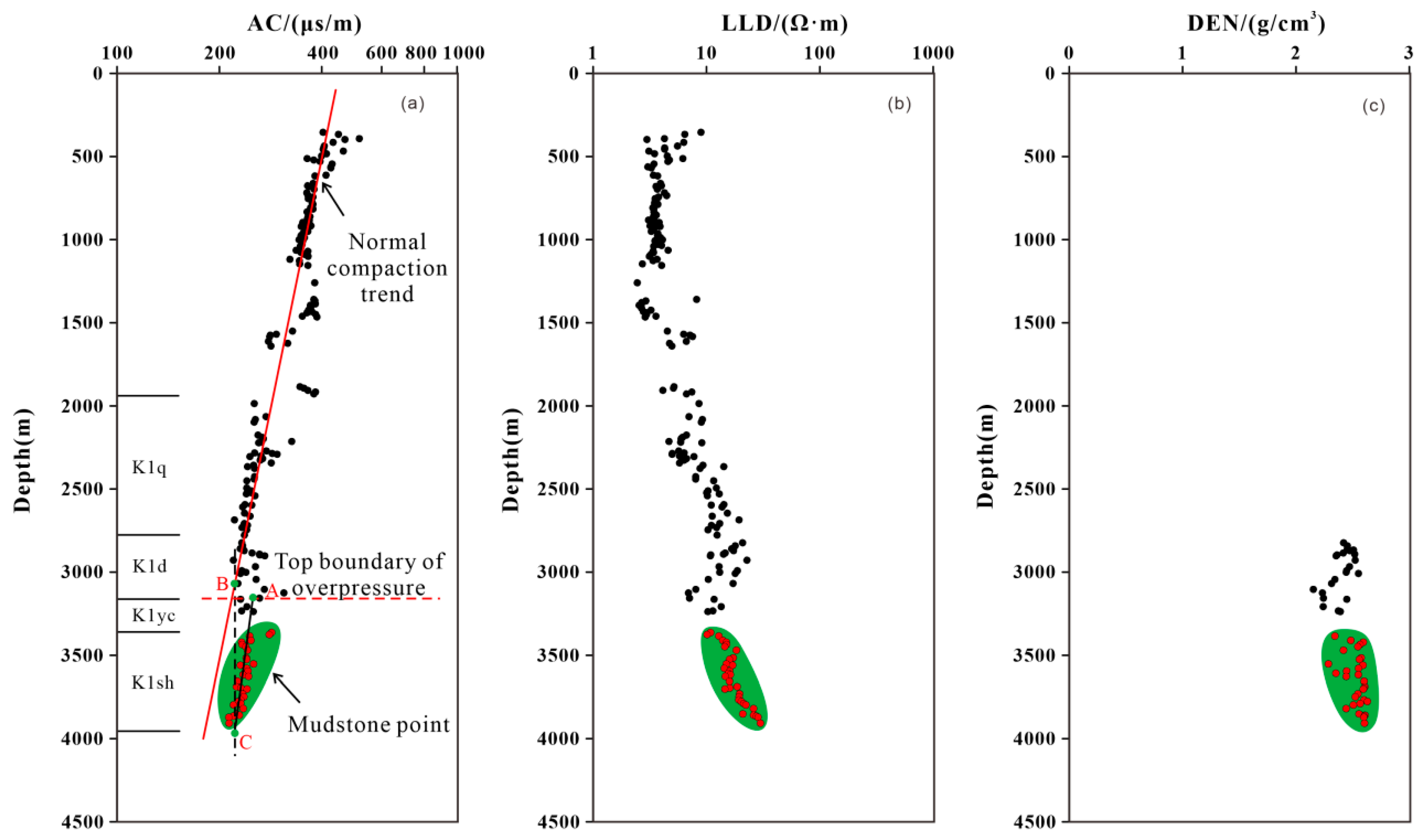

4.2. Causes of Abnormal Pressure

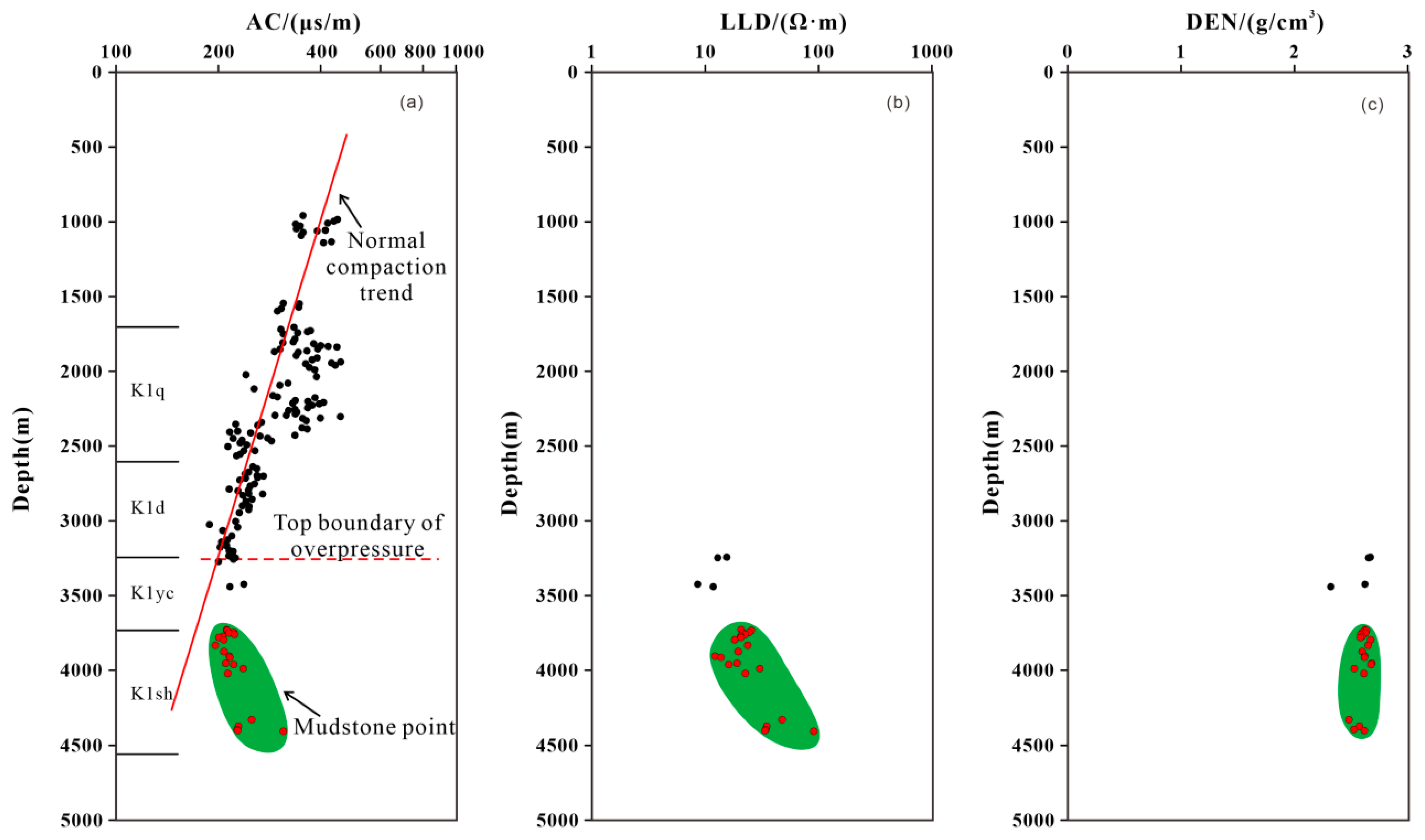

4.2.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Logging Curves

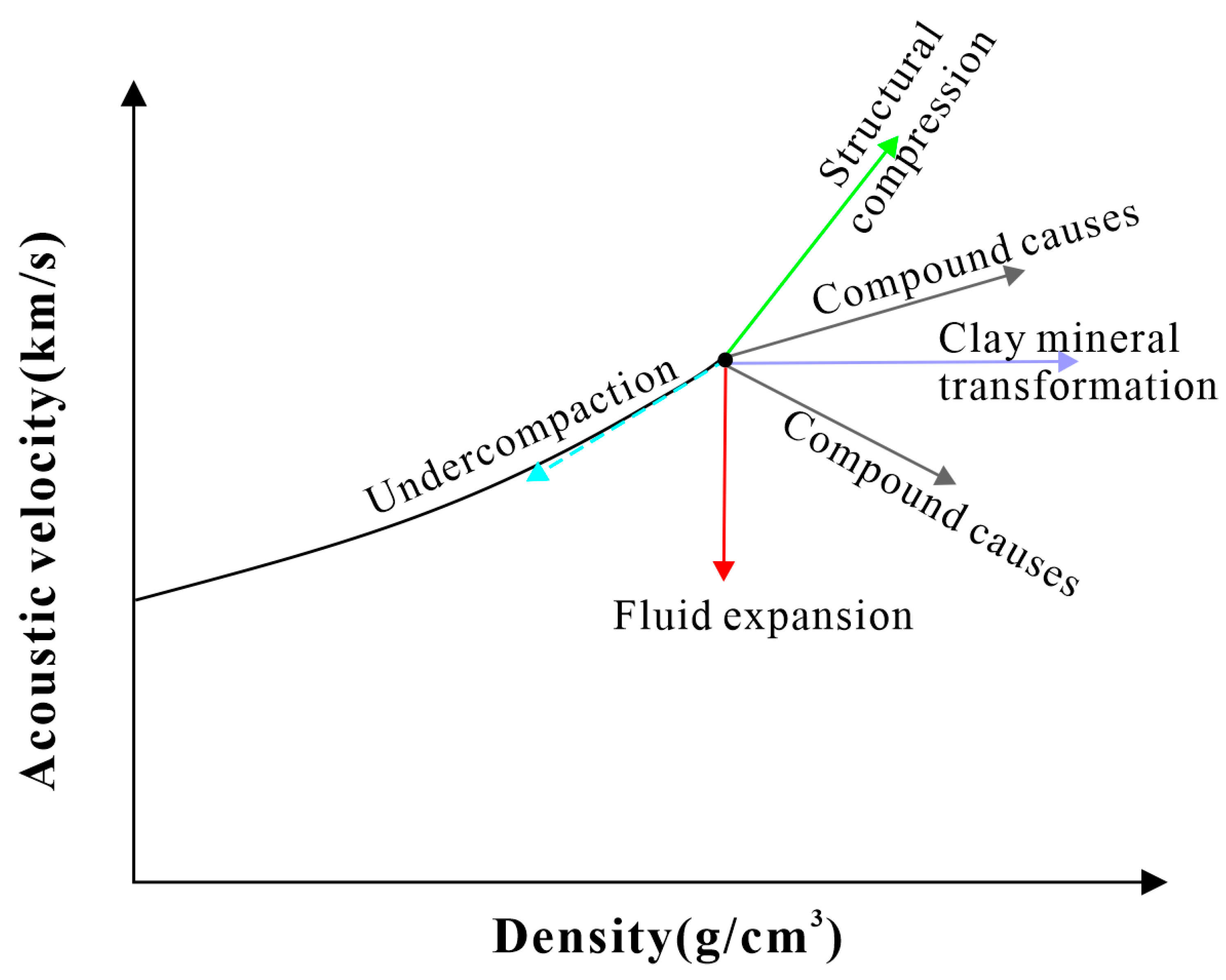

4.2.2. Intersection Graph Method of Acoustic Velocity and Density

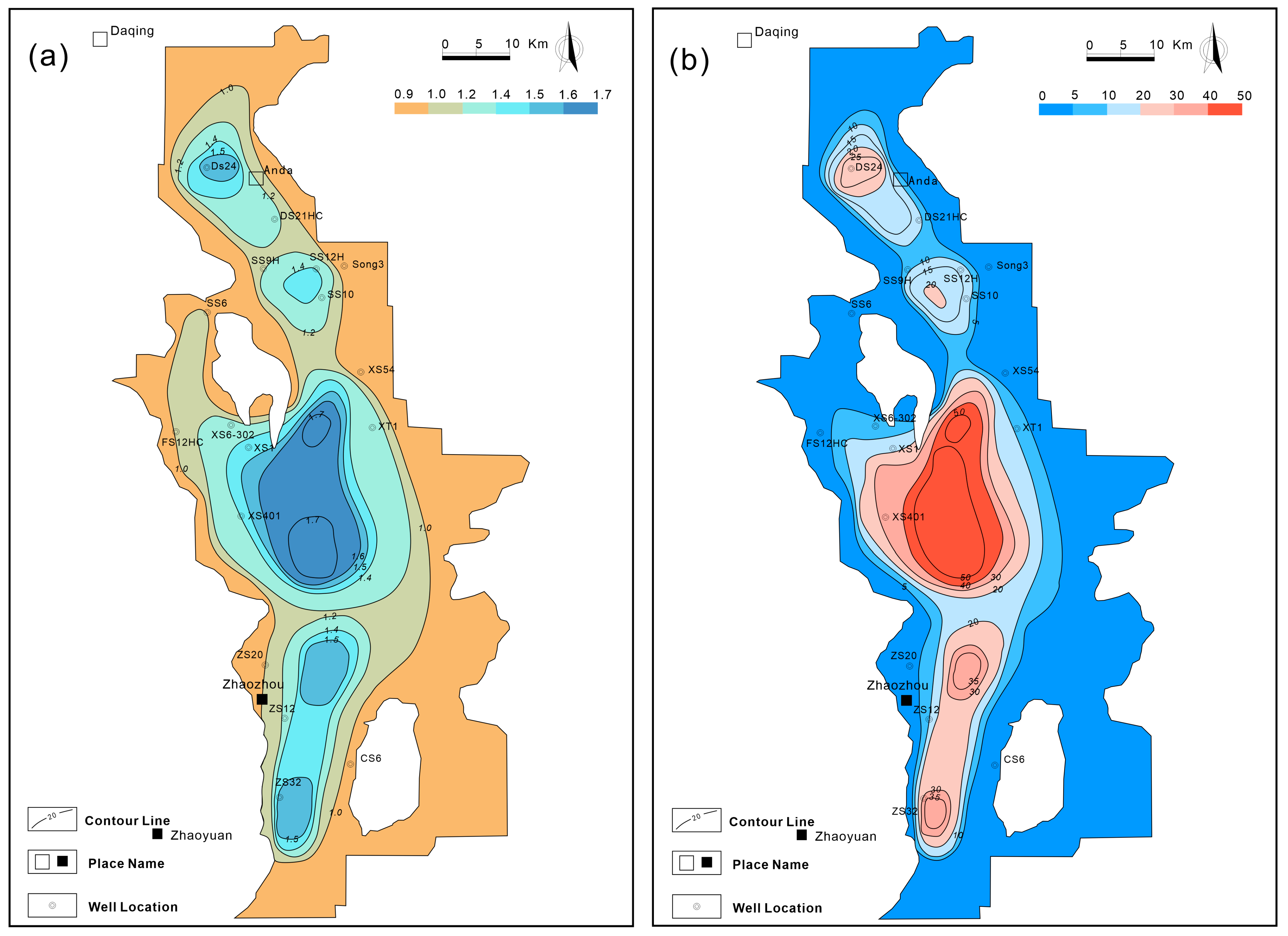

4.3. Current Formation Pressure Prediction of the Shahezi Formation

5. Paleo-Pressure Evolution of the Shahezi Formation in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression

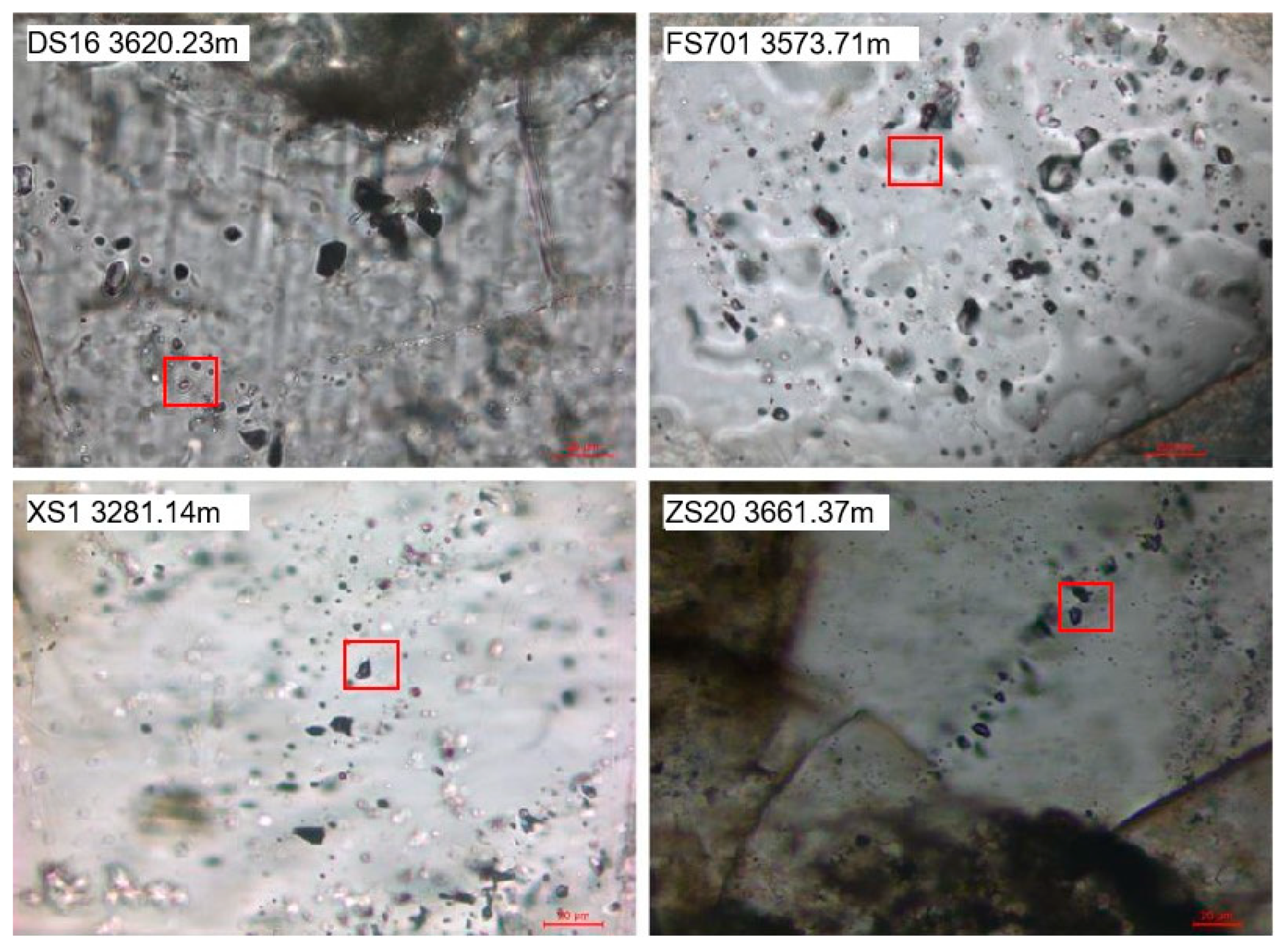

5.1. Pore Pressure of Typical Samples

5.2. Pressure Evolution of Typical Wells

- (1)

- Hydrostatic stage (135–104 Ma): In this stage, sedimentation rates were relatively low, burial depths remained shallow, and the sediments were loosely compacted with good pore connectivity. No abnormal pressure system was developed.

- (2)

- Rapid pressure increase stage (104–78 Ma): This stage involves the onset of rapid deposition in the Shahezi Formation. With increasing burial depth, porosity declined sharply, and the formation became progressively compacted, creating the necessary sealing conditions for overpressure development. Concurrently, the rapid maturation of organic matter and intense hydrocarbon generation led to the formation of a pronounced overpressure system.

- (3)

- Continuous pressure buildup stage (78–65 Ma): By the end of the Cretaceous, the Xujiaweizi Depression underwent tectonic inversion, accompanied by uplift and erosion. Although sedimentation rates decreased and burial depth increase slowed, overpressure continued to accumulate, reaching a peak of around 65 Ma.

- (4)

- Pressure dissipation stage (65–0 Ma): Entering the Cenozoic, the formation experienced significant uplift and erosion, leading to the adjustment of and a gradual decline in the pressure in the system.

6. The Influence of Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Shahezi Formation in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression of the Songliao Basin currently belongs to a high-pressure–ultra-high-pressure system. The overpressure of the source rocks is mainly due to hydrocarbon generation and undercompaction.

- (2)

- The evolution of the pore pressure could be divided into four stages. Prior to the end of the Early Cretaceous (~104 Ma), the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression was in a normal pressure state. In the early Late Cretaceous (104–78 Ma), the source rocks experienced overpressure due to undercompaction and hydrocarbon generation, which was a stage of rapid pressure increase. The Late Cretaceous period (78–65 Ma) was a stage of continuous increase in pressure. During this stage, a large amount of gas was produced from source rocks, and the pressure reached its maximum value. From the Early Paleogene to the present (65–0 Ma), it was a stage of slow pressure decrease. The strata underwent slow uplift, and the pressure gradually decreased.

- (3)

- High pressure can promote the transformation of heavy hydrocarbon gases in the C1–C5 components to methane, but the promoting effect is limited. In contrast, high pressure has a certain effect on the preservation of liquid hydrocarbon components, and this preservation effect may be caused by the transformation of unstable saturated hydrocarbons to aromatics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Jia, C.; Li, J.; Meng, Q.; Jiang, L.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, X. Whole petroleum system and hydrocarbon accumulation model in shallow and medium strata in northern Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 784–797. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Li, P.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, J.; Chen, X. Effective source rock selection and oil–source correlation in the western slope of the northern songliao basin, China. Pet. Sci. 2021, 18, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, W.; Fu, L.; Xue, T.; Bao, L. Accumulation and exploration of petroleum reservoirs in West slope of northern Songliao Basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 236–246. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Meng, Q.; Lin, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Sun, G. Evolution features of in-situ permeability of low-maturity shale with the increasing temperature, cretaceous nenjiang formation, Northern Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 453–464. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shan, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, P.; He, W.; Xiao, M.; Liu, C.; Ma, X. Tight gas accumulation in middle to deep successions of fault depression slopes: Northern slope of the Lishu Depression, Songliao Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 174, 107302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xiang, C.; Du, X.; Xie, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, C. Geochemistry and origins of hydrogen-containing natural gases in deep Songliao Basin, China: Insights from continental scientific drilling. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Lu, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, G. Depositional and diagenetic controls over reservoir quality of tight sandstone and conglomerate in the lower Cretaceous Shahezi formation, Xujiaweizi fault depression, Songliao basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 155, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, G. Gas accumulation conditions and exploration orientation of coal measure gas in Shahezi Formation in Xujiaweizi Fault Depression. China Pet. Explor. 2024, 29, 71–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, C. Accumulation conditions and resource potential of tight glutenite gas in fault depression basins: A case study on Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation in Xujiaweizi fault depression, Songliao Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2016, 21, 53–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, B. Tight gas explo ration and the next research direction for Shahezi Formation in North Songliao Basin. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2019, 38, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Liu, G. Overpressure-generating mechanism and its evolution characteristics of Cretaceous Shahezi Formation in Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin. Lithol. Reserv. 2025, 37, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Comprehensive sweet point evaluation and exploration results of tight glutenite reservoir in fault basin: A case study of the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation in Xujiaweizi fault depression in the north ern Songliao Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2022, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.M. Generation and migration of petroleum from abnormally pressured fluid compartments. AAPG Bull. 1990, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Zou, Y.; Carr, A. Study of the influence of pressure on enhanced gaseous hydrocarbon yield under high pressure–high temperature coal pyrolysis. Fuel 2010, 89, 3590–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, R.; Landais, P.; Philp, R.; PTorkelson, B.E. Effects of Pressure on Organic Matter Maturation during Confined Pyrolysis of Woodford Kerogen. Energy Fuels 1994, 8, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.; Wenger, L. The influence of pressure on petroleum generation and maturation as suggested by aqueous pyrolysis. Org. Geochem. 1992, 19, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Gu, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, D. Hydrocar bon accumulation stages and type division of Shahezi Fm tight glutenite gas reservoirs in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2017, 37, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Research on the Source-Reservoir-Cap Conditions and Tight Gas Accumulation Rule in Shahezi Group of Xujiaweizi Fault Depression; Northeast Petroleum University: Daqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Feng, Z.; Liu, W.; Song, Y.; Shu, P. Research on reservoir forming time of deep natural gas in Xujiaweizi faulted depression in Songliao Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2006, 27 (Suppl. 1), 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, S.; Cheng, H.; Dai, C.; Li, D. Sedimentary facies types and evolution models of the Shahezi For mation in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2024, 42, 1460–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.; Hu, M.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Sedimentary characteristics and development model of fan delta in small faulted basin: A case of Shahezi Formation in northern Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, NE China. Lithol. Reserv. 2018, 30, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Z.; Ma, J. Experimental development and application of source rock thermal simulation for hydrocarbon generation and expulsion. Pet. Geol. Expe. 2021, 43, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19144-2010; Isolation Method for Kerogen from Sedimentary Rock. China National Standardization Administration Committee: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Aplin, A.C.; Larter, S.R.; Bigge, M.A.; Macleod, G.; Swarbrick, R.E.; Grunberger, D. PVTX history of the North Sea’s Judy oilfield. J. Geochem. Explor. 2000, 69–70, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, A.C.; Macleod, G.; Larter, S.R.; Pedersen, K.S.; Sorensen, H.; Booth, T. Combined use of Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopyand PVT simulation for esti mating the composition and physical properties of petroleum in fluid inclusions. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1999, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Xiao, X.; Liu, D.; Shen, J. Simulation and calculation of paleopressure in natural gas reservoir formation using the PVT characteristics of reservoir fluid inclusions: A Case study of the Upper Paleogenic deep basin gas reservoir in the Ordos Basin. Sci. China 2003, 33, 679–685. [Google Scholar]

- Kauerauf, A.I.; Hantschel, T. Fundamentals of Basin and Petroleum Systemsmodeling; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ruan, X. Systematic Restoration of Eroded Thickness by Unconformity in Cretaceous of Xujiaweizi in the North of Songliao Basin. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2012, 37 (Suppl. 2), 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.J.; Burnham, A.K. Evaluation of a simple model of vitrinite reflectance based on chemical kinetics. AAPG Bull. 1990, 74, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, H. Rebuilding of Palaeohydrodynamic Field in Sedimentary Basin: Principle and Means. J. Northwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1997, 27, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; He, S.; Liu, K.; Dong, T. A quantitative esti mation model for the overpressure caused by natural gas gen eration and its influential factors. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2013, 38, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Numerical simulations of the burial & thermal his tories for Daqing placanticline in north Songliao Basin. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. 2015, 34, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B. Numerical simu lation of geohistory of the Qijia area in the Songliao Basin and geological significance. Geol. Explor. 2019, 55, 661–672. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z. Characteristics of tectono-thermal evolution of Carboniferous-Permian in Songliao Basin. Master’s Thesis, Northwestern University, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, S.; Sun, D.; Chai, W.; Zheng, J. Prediction of pore-fluid pressure in deep strata of the Songliao Basin. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2000, 25, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tingay Mark, R.P.; Hillis Richard, R.; Swarbrick Richard, E.; Morley Chris, K.; Damit Abdul, R. Origin of overpressure and pore-pressure prediction in the Baram province, Brunei. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingay Mark, R.P.; Morley Chris, K.; Laird Andrew Limpornpipat, O.; Krisadasima, K.; Pabchanda, S.; Macintyre Hamish, R. Evidence for overpressure generation by kerogen-to-gas maturation in the northern Malay Basin. AAPG Bull. 2013, 97, 639–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M.; Swarbrick, R. Mechanisms for generating overpressure in sedimentary basins: A reevaluation. AAPG Bull. 1997, 81, 1023–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, J. Recognition Model and Contribution Evaluation of Main Over pressure Formation Mechanisms in Sedimentary Basins. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2013, 24, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Xu, Z. Advances in the origin of overpressure in Sedimentary Basins. ACTA Pet. Sin. 2017, 38, 973–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Deng, K.; Zhang, J. Overpressure characteristics and classification of tight gas reservoirs in Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation in the middle section of the West Sichuan Depression, China. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2010, 17, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.J.; Tang, Y.; Kaplan, I. The Influence of Pressure on the Thermal Cracking of Oil. Energy Fuels 1996, 10, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q. Overpressure retardation of organic-matter maturation and petroleum generation; a case study from the Yinggehai and Qiongdongnan basins, South China Sea. AAPG Bull. 1995, 79, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Depth (m) | Strata | Lithology | Ro | TOC | Kerogen Type | Tmax (°C) | S1 (mg/g) | S2 (mg/g) | HI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC1 | 1122.58 | K1sh | Mudstone | 0.48 | 4.07 | II2 | 444.00 | 0.36 | 5.85 | 143.69 |

| Kerogen | 0.48 | 68.82 | II2 | 419 | 2.77 | 105.57 | 153.4 |

| Formation or Event Name | Type | Start Age (Ma) | Top Depth (m) | Present Thickness (m) | Eroded Thickness (m) | Heat Flow (mW/m2) | Exponential Compaction Factor (1/km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | Formation | 1.8 | 0 | 40 | - | 82 | 0.51 |

| K2m-Erosion | Erosion | 65 | - | - | −150 | 104 | - |

| K2m | Formation | 68.5 | 40 | 240.93 | - | 102 | 0.46 |

| K2S | Formation | 78 | 280.93 | 193.07 | - | 99 | 0.48 |

| K2n-Erosion | Erosion | 80 | - | - | −40 | - | - |

| K2n | Formation | 86 | 474 | 953.02 | - | 98 | 0.49 |

| K2y | Formation | 87 | 1427.02 | 176.98 | - | 96 | 0.49 |

| K2qn | Formation | 93 | 1604 | 351.04 | - | 95 | 0.51 |

| K1q | Formation | 100 | 1955.04 | 936.42 | - | 94 | 0.48 |

| K1d | Formation | 104 | 2891.46 | 360.38 | - | 93 | 0.42 |

| K1yc | Formation | 117 | 3251.84 | 453.66 | - | 87 | 0.15 |

| K1sh | Formation | 135 | 3705.5 | 842.5 | - | 82 | 0.40 |

| Pressure Coefficient | <0.90 | 0.90~0.98 | 0.98~1.02 | 1.02~1.12 | >1.12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure classification | Ultra-low pressure | Low pressure | Normal pressure | High Pressure | Ultra-high Pressure |

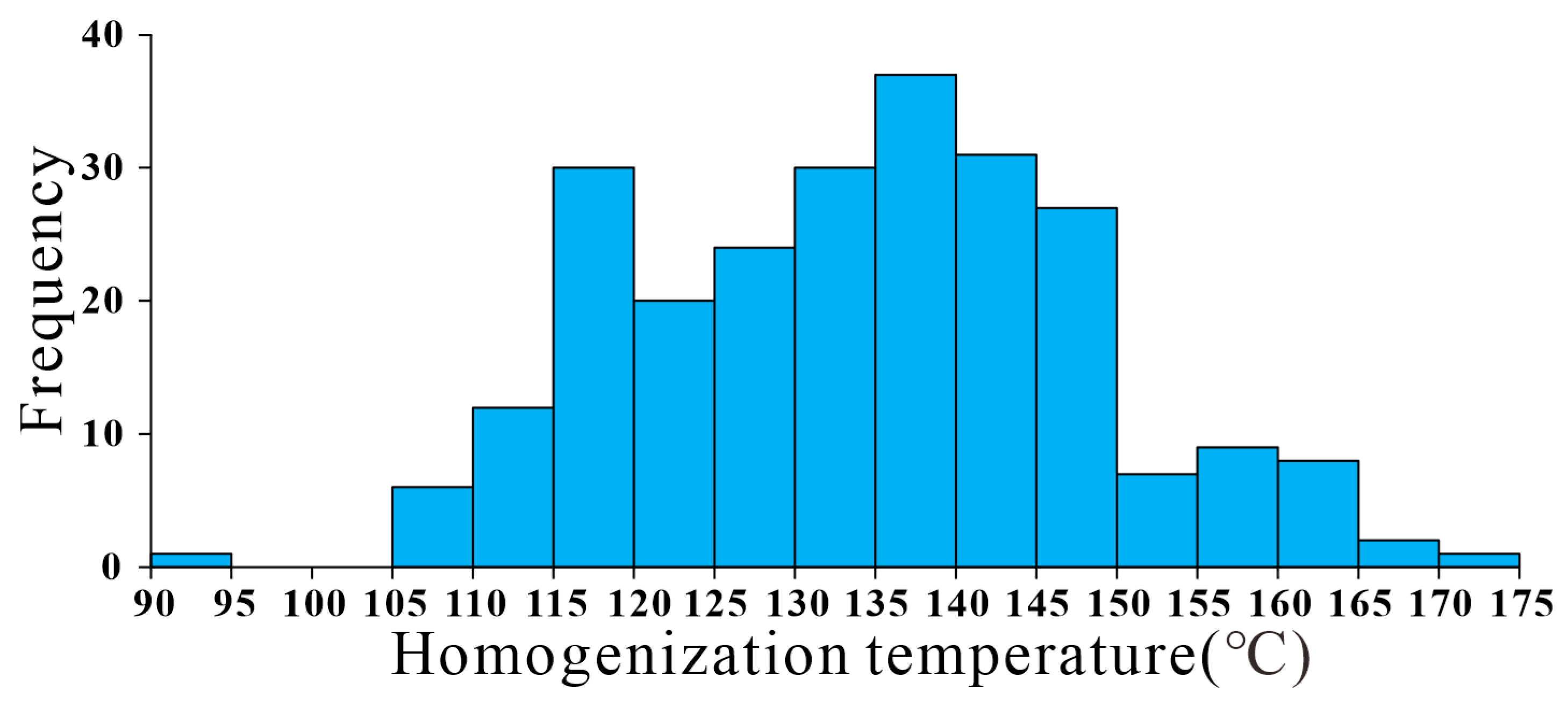

| Well | Depth (m) | Homogenization Temperature (°C) | Salinity (%) | Capture Temperature (°C) | Capture Pressure (MPa) | Capture Time (Ma) | Paleo-Depth (km) | Excess Pressure (MPa) | Pressure Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS2 | 3862.34 | 146.50 | 9.865 | 161.5 | 35.63 | 87 | 2900.12 | 6.63 | 1.22 |

| DS16 | 3620.23 | 135.27 | / | 150.27 | 36.61 | 87 | 2781.81 | 8.79 | 1.31 |

| XS1 | 3924.43 | 141.77 | / | 156.77 | 35.78 | 93 | 2643.30 | 9.347 | 1.35 |

| SS6 | 3580.02 | 143.67 | / | 158.67 | 34.67 | 90 | 2650.21 | 8.16 | 1.31 |

| SS201 | 3426.80 | 136.89 | / | 151.89 | 36.46 | 85 | 2650.33 | 9.95 | 1.37 |

| ZS6 | 3965.00 | 146.18 | / | 161.18 | 35.66 | 87 | 2855.23 | 7.10 | 1.25 |

| CZ7 | 3822.91 | 150.88 | / | 165.88 | 35.25 | 95 | 2870.56 | 6.55 | 1.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, J.; Yang, X.; Sun, L.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y.; Yu, M. The Evolution and Influence of Pore-Fluid Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter in the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation, Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Energies 2025, 18, 6400. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246400

Fu J, Yang X, Sun L, Yuan H, Liu Y, Zhang P, Guo Y, Yu M. The Evolution and Influence of Pore-Fluid Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter in the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation, Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6400. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246400

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Jian, Xin Yang, Lidong Sun, Hongqi Yuan, Yuchen Liu, Pengyi Zhang, Yajun Guo, and Miao Yu. 2025. "The Evolution and Influence of Pore-Fluid Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter in the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation, Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China" Energies 18, no. 24: 6400. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246400

APA StyleFu, J., Yang, X., Sun, L., Yuan, H., Liu, Y., Zhang, P., Guo, Y., & Yu, M. (2025). The Evolution and Influence of Pore-Fluid Pressure on Hydrocarbon Generation of Organic Matter in the Lower Cretaceous Shahezi Formation, Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Energies, 18(24), 6400. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246400