Abstract

The evolution of Smart Grids enabled the deployment of intelligent and decentralized energy management solutions at the residential level. This work presents a comprehensive Smart Home architecture that integrates real-time energy monitoring, appliance-level consumption analysis, and environmental data acquisition using smart metering technologies and distributed IoT sensors. All collected data are structured into a scalable infrastructure that supports advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI) methods, including Large Language Models (LLMs) and machine learning, enabling predictive analysis, personalized energy recommendations, and natural language interaction. Proposed architecture is experimentally validated through a case study on a domestic refrigerator. Two series of tests were conducted. In the first phase, extreme usage scenarios were evaluated: one with intensive usage and another with highly restricted usage. In the second phase, normal usage scenarios were tested without AI feedback and with AI recommendations following them whenever possible. Under the extreme scenarios, AI-assisted interaction resulted in a reduction in daily energy consumption of about 81.4%. In the normal usage scenarios, AI assistance resulted in a reduction of around 13.6%. These results confirm that integrating AI-driven behavioral optimization within Smart Home environments significantly improves energy efficiency, reduces electrical stress, and promotes more sustainable energy usage.

1. Introduction

Smart Homes represent a significant advancement in the way individuals interact with their domestic environments, using modern technologies to enhance comfort, security, energy efficiency, and overall quality of life [1,2,3]. The integration of Internet-connected devices, commonly referred to as the Internet of Things, enables remote and automated control of household systems such as lighting [4], climate regulation, security, and entertainment. However, despite substantial progress in automation, user interaction within many existing Smart Home solutions remains limited to predefined commands or rigid interfaces, which often reduces intuitiveness and adaptability.

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence has considerably expanded the capabilities of Smart Home systems by allowing them to learn behavioral patterns, predict user needs, and optimize resource management in real time. Even so, most electric current solutions still face limitations in human-machine communication because they often lack contextual understanding and natural dialogue capabilities. This limitation prevents residents from making fully informed decisions and restricts the potential for dynamic energy management and sustainable operation.

The use of conversational agents in Smart Home ecosystems has the potential to greatly enhance both user interaction and overall system intelligence [5,6]. By using data collected through Internet of Things devices, these agents can provide context-aware responses, anticipate user needs, and support seamless control of home appliances and energy-related systems. This approach not only improves usability, allowing residents to operate complex home technologies through natural language, but also enables personalized recommendations based on real-time environmental conditions and historical usage patterns [7,8]. As a result, interaction between the user and the Smart Home becomes more intuitive, efficient, and adaptive, contributing to optimized energy consumption and a more comfortable living environment [9].

To address these challenges, this work proposes an innovative approach that integrates a chatbot powered by a Large Language Model into a Smart Home ecosystem. This integration enables natural, dynamic, and context-aware interaction between residents and the intelligent home system. Through this conversational interface, users can request information about overall home status, specific device status, energy consumption, or unusual activity and receive intelligent feedback in real time. Additionally, the system provides personalized recommendations to improve energy efficiency and comfort, encouraging greater user engagement and awareness [10].

The proposed architecture includes processing real-time data collected from electric current sensors embedded in household appliances. By analyzing these data streams, the system identifies consumption patterns, detects inefficiencies, and suggests improvements that users can apply directly. It also supports autonomous or semi-autonomous decision-making, allowing both the user and the system to act proactively based on learned behaviors and contextual insights. The integration of Internet of Things technologies, Artificial Intelligence, and interaction based on Large Language Models transforms the Smart Home into a responsive, adaptive, and sustainable environment, aligning technological innovation with ecological responsibility.

To achieve this goal, Smart Home architecture was designed to define the essential components required for data acquisition, data processing, and intelligent interaction. This architecture forms a foundation for understanding how AI-driven reasoning and natural language interfaces can be combined to enhance Smart Home autonomy and improve the user experience.

The main objective of this research is to develop an intelligent, automated, and user-friendly home energy management system that brings together real-time data collection, AI-based analytics, and conversational interaction with a Large Language Model. This work addresses the existing research gap, which is the lack of a holistic Smart Home energy management solution that integrates continuous monitoring, contextual reasoning, and natural dialogue in a single system that supports both automation and user empowerment. The study contributes by presenting a unified architecture based on Internet of Things sensing and intelligent decision-making, by incorporating a Large Language Model to enable natural and context-aware interaction with home and its appliances, and by implementing and experimentally validating a prototype capable of identifying energy consumption patterns and offering actionable recommendations [11]. Together, these contributions demonstrate how advanced intelligent systems can improve sustainability, energy efficiency and the overall quality of interaction in modern Smart Homes [12].

2. Smart Home Fundamentals and Integration with Artificial Intelligence

2.1. Definition of Smart Homes with AI

Smart Homes are residential environments equipped with internet-connected devices [13] that rely on the Internet of Things (IoT) to enable remote management, automation and customization of a wide range of domestic functions. These devices—including smart thermostats, security cameras, lighting systems, environmental sensors and virtual assistants, among others communicate with each other through Wi-Fi networks [14,15,16,17,18]. Beyond convenience, Smart Homes play a central role in promoting energy efficiency [19,20] and sustainability, which are fundamental pillars of the green economy. By collecting and analyzing operational data, it becomes possible to optimize energy consumption, reduce waste and adapt the operation of household equipment to user needs. For example, motion sensors can automatically switch lighting on or off, and intelligent systems can recommend the most appropriate times to perform certain activities, such as opening the refrigerator or operating the washing machine, based on consumption patterns and energy availability [21,22].

The integration of intuitive interfaces, such as interactive dashboards and chatbots powered by Large Language Models (LLMs), enables direct communication between users and the system, allowing them to personalize their environment in a simple and effective manner [23]. This modular and user-centered approach enhances not only the functionality of connected Smart Homes but also improves user control, accessibility and adaptability [24], supporting more intelligent energy management aligned with the objectives of the green economy. Furthermore, Green Internet of Things technologies contribute to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and can play a meaningful role in mitigating the greenhouse effect [25,26,27].

2.1.1. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Smart Homes, Energy Optimization and Sustainability

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become increasingly central to the development and operation of Smart Homes, playing a key role in improving energy efficiency, intelligent automation and environmental sustainability [28,29]. By integrating machine learning algorithms, neural networks and natural language processing techniques, Smart Home systems can learn from user habits, predict consumption patterns and make optimized decisions in real time regarding energy distribution [30,31].

AI encompasses systems that replicate human cognitive functions, including the acquisition of knowledge, logical reasoning, problem solving and data driven decision-making. In the context of Smart Homes, AI is applied to enhance automation and improve user interaction by enabling personalized management of daily activities. Through advanced algorithms, AI analyses the data generated by IoT devices, predicts user behavior and automatically adjusts environmental parameters according to individual preferences [32].

A fundamental application of AI in Smart Homes lies in intelligent energy management. By continuously analyzing data from sensors and connected devices, AI based systems can identify opportunities for reducing energy consumption, automatically regulate heating and cooling, control lighting, manage appliance usage and encourage more sustainable user behavior [33]. For example, these systems can switch off devices left in standby mode, optimize electricity use based on dynamic pricing or predict consumption peaks to prevent grid overload.

AI also enables deep personalization of the user experience by proactively adapting the home environment to individual needs. Through the integration of virtual assistants and conversational interfaces, users can interact naturally with the system and receive energy saving recommendations, alerts regarding abnormal consumption and detailed environmental performance reports. This type of implementation leverages IoT technologies to support higher levels of energy efficiency [34].

Another significant aspect is the predictive capability of AI, which allows the system to anticipate energy demands based on historical climate conditions and behavioral patterns. This capability is essential for the efficient integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, whose availability is inherently variable [35].

Finally, AI enhances the resilience and security of Smart Homes by detecting system failures, preventing electrical hazards and ensuring the continuity of essential services [36]. When combined with modular and interoperable platforms, AI enables decentralized and scalable energy management across the home, supporting the principles of the green economy and contributing to sustainable development [37,38].

2.1.2. Technological Solutions Implemented in AI Smart Homes

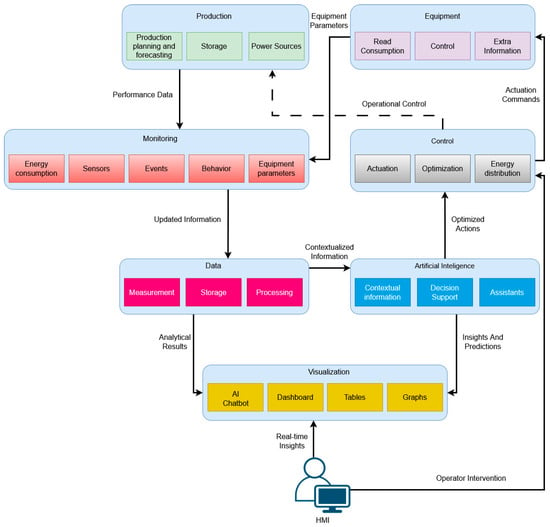

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into smart home environments relies on a set of interconnected technologies that collectively enable automation, efficiency and personalization. As illustrated in Figure 1, the conversational AI interface functions as the central element of this architecture, linking smart sensors, neural networks and machine learning algorithms. Through this integrated framework, devices are capable of continuously monitoring environmental variables, interacting with users through natural language and adapting their behavior over time based on learned usage patterns. This dynamic interaction fosters a more intelligent, energy efficient and responsive home ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Solution smart energy management with decision support.

Several key technologies underpin the effective incorporation of AI within smart homes. These include smart sensors, which measure and monitor environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, electric current, voltage and motion [39,40,41,42]. Conversational AI interfaces, such as Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant and Apple Siri, rely on AI driven natural language processing to support seamless human machine interaction. Neural networks provide the computational foundation that enables the system to learn and adapt to user behaviors through continuous pattern recognition and data analysis [43,44,45]. Machine learning algorithms further enhance the system by optimizing energy efficiency, forecasting consumption patterns and improving the overall performance of home automation in real time.

The combination of these technologies supports the development of intelligent, adaptive and energy conscious living environments that align with the objectives of sustainable and user centered smart home design.

2.2. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Smart Homes

- Energy Resource Management and Energy Efficiency

Energy management is one of the primary domains where artificial intelligence (AI) has been applied in smart homes [46,47]. AI systems can analyze patterns of energy consumption and optimize the operation of household devices by automatically adjusting lighting, temperature, and other appliances to minimize energy waste [48]. Such intelligent control contributes to enhanced energy efficiency and sustainability within residential environments.

- Home Security

Home security represents another critical area in which AI technologies are increasingly employed. AI-enabled security cameras can recognize faces and detect suspicious activities, thereby alerting residents or authorities in real time. These systems can monitor entry and exit events, identify behavioral patterns, and issue alerts when anomalies are detected. When integrated with other Internet of Things (IoT) devices—such as motion sensors, smart locks, and connected alarms-AI provides an additional layer of protection for homeowners [49,50].

- User Assistance and Comfort

AI technologies also enhance user assistance and overall comfort in smart homes. Intelligent virtual assistants, such as Amazon Alexa or Google Assistant, can manage daily household tasks, control lighting and electronic devices, schedule appointments, make online purchases, and respond to natural language queries [51,52,53]. Moreover, AI systems can learn residents’ habits and preferences over time, enabling the home environment to adapt proactively. Examples include scheduling appliance operations, preparing coffee at a preferred time, or adjusting indoor temperature prior to the resident’s arrival. By automating routine activities and anticipating user needs, AI enhances the overall living experience while improving resource efficiency and saving time.

2.3. Challenges in Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Smart Homes

- Information Privacy and Protection

One of the primary issues with the implementation of AI in Smart Homes is privacy. Internet-connected devices collect large amounts of data about users’ habits, preferences, and movements. This raises security concerns, such as whether the stored and processed data is protected against cyberattacks [54,55,56,57]. Furthermore, cybersecurity is a constant concern, since the vulnerability of connected devices can be exploited by criminals. The more connected devices there are, the more this vulnerability increases [58,59,60].

- Device Interoperability

Interoperability between different IoT devices from different brands and manufacturers can be a problem. Often, devices cannot communicate effectively with each other, which can compromise the efficiency of the system. Standard protocols and integration platforms are necessary to ensure that all devices work correctly [61,62].

- Accessibility and Cost

Although Smart Home technology is gaining popularity, it is inaccessible to many people due to the cost of smart devices. This creates a disparity in access to the benefits of home automation. Furthermore, accessibility can be a challenge for people with special needs, such as the elderly or people with disabilities, who may have difficulty using AI-based control interfaces [63,64].

3. Architecture and Prototype Proposal

Efficient energy management in Smart Homes and microgrids is becoming increasingly essential as the number of connected devices and energy sources grows. Figure 1 presents the architecture of a complex and intelligent system for energy management in a Smart Home or microgrid. In the following sections, each module and their interconnections are described, including the information data flow explanation.

3.1. Architecture Modules and Information Flow

The process begins with Energy Production, which includes planning, forecasting, storage, and the use of energy sources. Subsequently, equipment and sensors perform real-time consumption reading, control actions, and the collection of additional operational information.

The captured information feeds the Monitoring module, which records energy consumption, equipment behavior, events, and operational parameters. These updated data are forwarded to the Data layer, responsible for measurement, storage, and processing of large volumes of information.

After processing, the information is contextualized and sent to the Artificial Intelligence module, where it is analyzed and transformed into predictions, recommendations, and decision support. The system also includes an AI-based chatbot, which acts as an intelligent assistant, providing alerts and guidance in an interactive and user-friendly manner. However, despite the automation, the user always retains the final decision: any critical action or operational change can be manually executed through the HMI interface.

Based on the predictions and insights generated by the AI, optimized actions are transmitted to the Control module, which performs actuation, optimizes processes, and manages energy distribution. When necessary, commands are sent back to the equipment, closing the operational loop.

Analytical results are also presented in the Visualization layer through dashboards, tables, graphs, and reports, enabling the user to understand the overall state of the installation. This information ecosystem is designed to provide users with a clear perception of their environment, supporting more efficient and conscious decision-making.

In addition to improving comfort and automation, this architecture contributes to reducing ecological footprint. By optimizing energy consumption, identifying waste, suggesting sustainable behaviors, and encouraging rational use of resources, the system promotes environmentally responsible energy management.

In summary, this global architecture enables any appliance or connected device within a Smart Home to operate intelligently, efficiently, and autonomously, while still granting the user full control, transparent information access, and continuous decision-making support.

This architecture is highly adaptable and can be applied to a wide range of appliances, as illustrated in Figure 1. For initial testing, the system was implemented on a refrigerator, one of the most energy-intensive devices in a household. By framing each appliance within the functional blocks, the system ensures a holistic and scalable approach to energy management. The system is divided into seven main blocks, which interact with each other, creating a cycle of operation, monitoring, analysis, and decision. Each block and its general flow are explained in detail below.

In alignment with the challenges identified in Section 1, the presented architecture directly addresses the electric current limitations of Smart Home systems in terms of interactivity, contextual intelligence, and sustainable energy management. First, the integration of a chatbot powered by a Large Language Model (LLM) overcomes the constraints of fixed commands and rigid interfaces by enabling natural, context-aware communication between users and the system. This ‘conversational’ layer ensures intuitive access to system status, performance indicators, and operational recommendations, significantly improving usability and user engagement. Second, the combination of real-time data acquisition, historical storage, and AI-driven analytics enhances contextual understanding, allowing the system to learn consumption patterns, recognize anomalies, and predict optimal operating conditions. As a result, decision-making becomes proactive rather than reactive, and residents receive personalized, explainable recommendations supported by transparent information. Third, the closed operational loop—spanning measurement, forecasting, optimization, actuation, and human supervision—creates a foundation for intelligent energy management. By coordinating distributed energy resources, storage elements, and controllable loads, the system can reduce peak demand, minimizing operational cost and improving overall efficiency. Consequently, the proposed architecture not only increases autonomy and comfort but also supports environmentally responsible behavior through data-driven recommendations, waste reduction, and sustainable operation. Together, these mechanisms demonstrate how the proposed approach effectively addresses the deficiencies of existing Smart Home solutions, transforming the domestic environment into an adaptive and energy-aware ecosystem.

Figure 1 presents the functional architecture of the proposed Smart Home energy management system, organized into a closed operational loop composed of seven interconnected blocks. The process begins at the Equipment layer, where sensors and actuators acquire real-time electrical and operational variables while executing physical control actions. These measurements are transmitted to the Monitoring block, which aggregates consumption data, events, behavior, and equipment parameters to ensure continuous situational awareness.

Updated information is forwarded to the Data layer, responsible for storage, validation, and processing of time-series records. The resulting contextualized data supports the Artificial Intelligence module, which integrates predictive models, decision-support algorithms, and a natural-language assistant. By combining real-time system status with contextual information—such as weather forecasts, tariffs, and usage patterns, the AI module generates optimized actions, anomaly detection, and personalized recommendations.

These recommendations are executed by the Control block, which manages load scheduling, production and storage assets, and energy distribution while ensuring operational safety. The Production layer supplies information on renewable generation, grid interaction, and storage status, enabling strategies such as self-consumption maximization, peak-demand reduction, and battery optimization.

Finally, analytical results are delivered to the user through the Visualization block, which provides dashboards, graphs, tables, and chatbot interaction. Although the system can operate autonomously, the HMI allows the operator to intervene, approve, or modify decisions at any time.

Overall, Figure 1 demonstrates the complete data and control flow—from acquisition, analysis, and optimization to physical actuation and user interaction—highlighting how the proposed architecture enables intelligent, transparent, and sustainable Smart Home energy management.

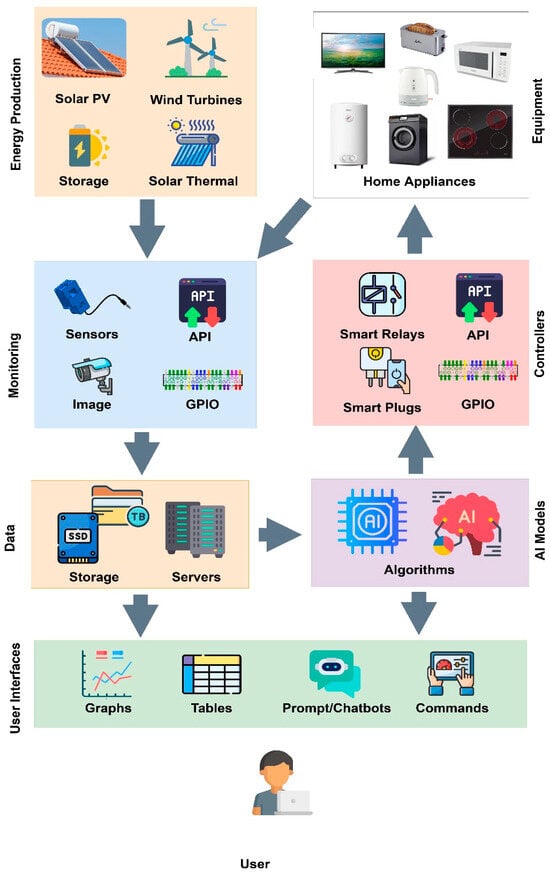

There are several types of electrical equipment to which this project may be applied, as shown in Figure 2. Initial validation of the project was performed on a household appliance—specifically the refrigerator—because it is one of the devices that consumes the most electricity in a home.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of the smart home energy monitoring and control framework.

An energy monitoring system is designed to control and monitor electrical energy efficiently, safely, and reliably. It combines sensors, control units, and user interfaces to ensure that monitoring aids problem-solving and decision-making.

3.2. Representation of the Implemented Architecture’s Equipment and Functional Modules

Figure 2 presents the physical implementation of the logical architecture defined in Figure 1. The devices are organized according to the same functional groups, such as energy production, monitoring, data management, control and user interaction, which allows each logical block to be directly associated with the equipment that performs that function.

Therefore, to further analyze Figure 2, the following blocks should be highlighted:

- (1)

- Energy Production

The Energy Production component encompasses all on-site technologies responsible for generating or storing energy. Typical residential deployments include photovoltaic (PV) panels for electricity generation, wind microturbines, and solar-thermal collectors for domestic hot water production. Storage units—either electrical batteries or thermal accumulators—enable surplus energy to be retained and dispatched when needed. This improves the self-consumption rate, reduces reliance on the grid, and mitigates intermittency associated with renewable resources.

- (2)

- Equipment (Energy Consumption)

This block comprises all domestic appliances that consume electrical energy, such as refrigerators, induction hobs, washing machines, dishwashers, televisions, kettles, microwaves, and water heaters. Each appliance can be monitored individually, enabling the system to record consumption profiles, identify operational patterns, and calculate their contribution to total household demand. These data are transmitted to the management platform for analytical processing.

- (3)

- Monitoring

The Monitoring layer is responsible for real-time acquisition of system data. Sensors, smart meters, communication APIs, image-based metering, and GPIO interfaces capture variables such as power, voltage, electric current, temperature, or equipment status. Continuous monitoring guarantees visibility over consumption and production flows, enabling anomaly detection, fault identification, and accurate system diagnostics.

- (4)

- Controllers

The Controllers block comprises actuation devices capable of modifying the operational state of household loads or energy sources. Smart relays, smart plugs, and GPIO-based actuators allow devices to be switched on/off, operated under specific schedules, or controlled according to external signals (e.g., price tariffs or renewable availability). Through these mechanisms, loads can be shifted to periods of higher energy availability or lower cost, improving global system efficiency.

- (5)

- Data (Storage and Processing)

All collected information is stored and processed within a centralized infrastructure, which may include local servers, cloud computing systems, and dedicated databases. This dataset supports key functionalities such as consumption analysis, historical tracking, anomaly detection, and performance optimization. Moreover, processed data are essential for training predictive models and generating reliable decision-making outputs.

- (6)

- AI Models

Artificial intelligence constitutes the decision-making layer of the system. Machine learning and optimization algorithms are employed to forecast PV generation, estimate future consumption, detect abnormal behavior, schedule flexible loads, and propose optimal control actions. By converting raw sensor data into informed decisions, AI enhances automation, energy efficiency, and user comfort while reducing operating costs.

- (7)

- User Interfaces

User interfaces present processed information in a structured and intuitive manner. Dashboards, visual analytics, tables, and chatbot-based interactions allow users to visualize energy flows, assess system performance, and modify operating configurations. These interfaces facilitate transparency and promote informed decision-making.

- (8)

- User

The end-user interacts with the system through mobile or desktop devices. Users can monitor real-time energy flows, receive recommendations generated by the AI, override automatic controls, or enable predefined operating strategies. Ultimately, architecture empowers consumers to actively participate in household energy management, contributing to improved efficiency, sustainability, and cost reduction.

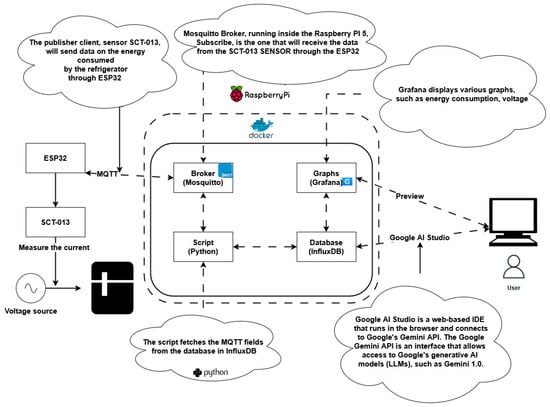

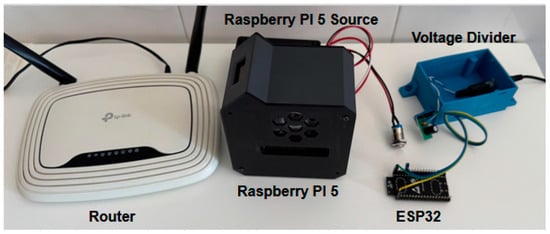

4. Logical Architecture

To better understand the interaction among components within the architecture, the solution is structured into three main layers, i.e., user section, software section and physical section. Figure 3 shows a more comprehensive overview of these layers.

Figure 3.

Raspberry PI 5 an architectural example that illustrates a use case.

Once the problems were identified and corresponding solutions defined, the next step involved determining the most suitable architectural implementation strategy, which culminated in the approach presented in Figure 3. Multiple architectural alternatives were evaluated, with emphasis on modularity, scalability, interoperability, and reproducibility. The final configuration accommodates heterogeneous applications while maintaining a low degree of implementation complexity. To achieve this, the system components were organized into the logical framework described earlier, providing a clearer conceptual representation of each phase of the workflow and enabling traceability across data processing stages.

Figure 3 illustrates the complete end-to-end architecture and serves as a practical use case demonstrating the operational behavior of the Raspberry Pi 5 when a user interacts with the Google AI Studio prompt. In this scenario, the figure exposes the complete interaction pipeline, beginning with user input and ending with processed data visualization and decision support.

Logical Layers of the Architecture

- User Section—this upper layer represents direct user interaction. It comprises the accessible endpoints, graphical interfaces, and the chatbot prompt. All communication here is restricted to high-level data exchange; low-level system logic, databases, and physical hardware are intentionally abstracted. This ensures usability, data privacy, and security by preventing uncontrolled access to critical resources.

- Software Section—this layer represents the computational core and is fully deployed on the Raspberry Pi. It contains the services and processes responsible for system execution, including:

- -

- Docker Engine, responsible for container orchestration and dependency isolation.

- -

- Python version 3.13.7, scripts for data acquisition and preprocessing.

- -

- The MQTT client, which subscribes to sensor topics and retrieves periodic measurements.

- -

- The chatbot service, which interprets user requests, fetches data from the database, and returns coherent responses.

All operations, from sensor polling to real-time monitoring and user interaction, are handled within this layer. Containerization ensures that each service runs independently, improving reliability, portability, and maintainability.

- Physical Section—the bottom layer consists of the physical hardware used to collect real-time measurements and communicate through MQTT. This includes:

- -

- SCT-013 non-invasive electric current transformer sensor, which measures the electric current consumed by the target appliance.

- -

- Signal conditioning circuitry, responsible for scaling and filtering analog output.

- -

- Analog-to-digital conversion, enabling acquisition on the Raspberry Pi.

- -

- MQTT broker and communication modules, ensuring lightweight, low-latency data publishing.

End-to-End Workflow

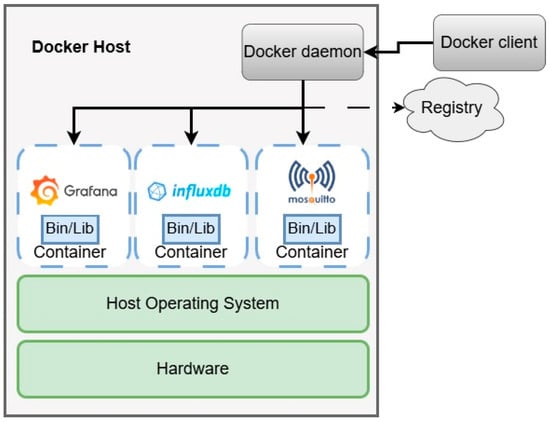

System execution begins with Docker initialization, which automatically deploys all required containers. Running the application inside containers ensures deterministic execution, simplified updates, and reproducibility across devices.

Once initiated, the SCT-013 sensor acquires electric current measurements at one-minute intervals. The resulting values are transmitted via MQTT to a broker, which decouples the producer (sensor) from consumer processes. A dedicated Python service subscribes to these topics, extracts the transmitted data, and persistently stores it in InfluxDB, enabling efficient time-series handling and historical querying.

The chatbot interface enables natural-language interaction. When the user submits a query—such as consumption status, historical usage, or alerts—the chatbot processes the prompt, retrieves the corresponding data from InfluxDB, and returns a structured response. This introduces a layer of intelligence and accessibility that is absent in traditional monitoring dashboards.

Contribution to Energy Monitoring

The primary advantage of the proposed architecture is its ability to monitor individual appliances within a household electrical network, demonstrated here using a refrigerator. By collecting periodic consumption data, the system can identify anomalous usage patterns, inefficiencies, or signs of equipment failure. Real-time analytics also support demand-response strategies and user-awareness interventions.

Appliances with higher power ratings (W) inherently produce larger energy consumption footprints and therefore benefit from fine-grained monitoring to support cost-reduction strategies. Many devices include energy-efficiency classifications, where ratings approaching A++ indicate lower consumption and environmentally favorable operation. The proposed system strengthens this decision-making process by notifying users—via automated smartphone alerts—when consumption deviates significantly from the expected operational profile, which may indicate malfunction, poor efficiency, or unusual load behavior.

4.1. Prototype Architecture with Detail

Figure 3 presents a practical use case that demonstrates how the proposed architecture can be applied to a domestic environment. In this example, the objective is to monitor the energy consumption of a refrigerator in real time and provide visualization and intelligent analysis of the collected data. The SCT-013 electric current sensor measures the electrical load of the appliance, and the readings are transmitted to an ESP32 microcontroller. The ESP32 publishes the data using the MQTT protocol.

All core services operate on a Raspberry Pi 5, which runs Docker containers to ensure modularity and ease of deployment. O Mosquitto broker receives the MQTT messages, while a Python script processes the measurements and stores the results in an InfluxDB time-series database. Grafana is used to retrieve the stored values and present interactive dashboards to the user through a web interface.

The system also incorporates an optional artificial intelligence component through Google AI Studio. The stored consumption data can be accessed by a Large Language Model, enabling predictive analysis, anomaly detection, and natural-language summaries of energy usage. This workflow demonstrates a complete and extensible energy monitoring solution, spanning data acquisition, storage, visualization, and intelligent optimization.

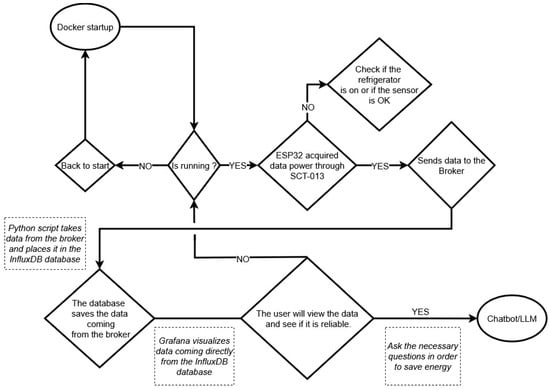

4.2. Process Flowchart

Figure 4 depicts the software flowchart of the monitoring system. After the Docker services are initialized, the system verifies that all components are running correctly. The ESP32 then acquires electric current measurements from the SCT-013 sensor. If no readings are detected, the system checks the refrigerator connection and sensor status before restarting the monitoring cycle.

Figure 4.

Software flowchart of the energy monitoring system.

Once measurements are successfully captured, the ESP32 publishes them to the MQTT broker. A Python script consumes the messages, processes the values, and inserts them into the InfluxDB database. Grafana connects directly to the database and displays the stored information in dashboards that allow the user to confirm data reliability.

If the data are considered consistent, the system enables an optional optimization stage through a chatbot supported by a Large Language Model. The user may request summaries, ask for recommendations, or query specific consumption patterns. Based on the stored measurements, the model can provide insights such as optimal usage periods, anomaly alerts or potential energy-saving actions. This final step converts raw sensor data into meaningful guidance for efficient operation of the appliance.

4.3. Voltage Divider

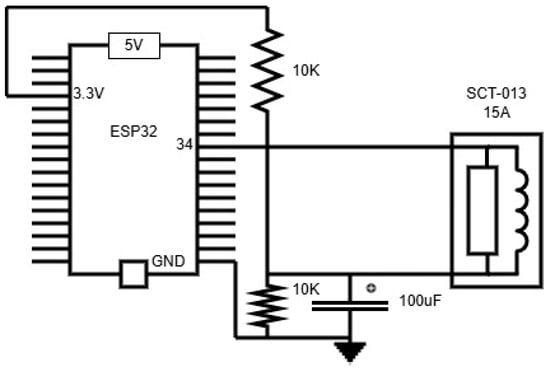

Figure 5 presents the schematic of the ESP32 with SCT-013 15A with voltage divider. The voltage divider is explained in next section.

Figure 5.

ESP32 with SCT-013 15A with voltage divider.

A voltage divider is a basic electrical circuit used to reduce voltage, with two resistors in series that reduces a higher voltage to a lower voltage, so that it is safe for an electronic component. This serves to adapt voltage levels, ensuring that a device does not receive a voltage above what it supports. The SCT-013 is an electric current sensor, which generates a voltage proportional to the electric current that passes through the monitored wire, this voltage can be higher than the ESP32’s analog input limit (typically 3.3 V). To protect the ESP32, a voltage divider is used to reduce this output of the SCT-013 to the value of 3.3 V. This way, the ESP32 can read the electric current safely using its ADC (Analog-to-Digital Converter). This converts an analog signal, with a continuous voltage that varies smoothly, for example, from 0 to 3.3 V, to a digital number that can be read by a microcontroller, such as the ESP32.

5. Test Scenario and Experiments

This section presents the experimental framework used to evaluate the impact of AI-assisted user interaction on the energy consumption and operational behavior of a domestic refrigerator–freezer system.

The experimental methodology was structured into three sequential phases: data acquisition, AI-based analysis and recommendation, and user-driven validation through controlled interaction.

In the first phase, an IoT-based monitoring system was deployed to continuously measure the electric current drawn by the appliance. The system consists of an ESP32 microcontroller and a non-invasive SCT-013 current transformer clamped around the live conductor supplying the refrigerator. This configuration enables real-time current measurement without requiring modifications to the electrical installation. The collected data were transmitted to a Docker-based infrastructure, where they were stored and organized for subsequent time-series analysis and energy estimation.

In the second phase, the acquired electric current data were processed using a cloud-hosted Large Language Model (LLM). The LLM was not used as a direct control entity, but rather as an intelligent analytical assistant. Through structured prompts, the model analyzed the time-series data to identify operating states (e.g., compressor ON/OFF cycles, start-up peaks, standby periods, and door-opening events) and to extract meaningful consumption patterns. Based on this analysis, the LLM generated energy-efficiency recommendations focused on user interaction, such as optimal time windows for refrigerator access and guidelines for introducing thermal loads (e.g., placing warm food inside the appliance).

In the third phase, these AI-generated recommendations were applied by the user during appliance operation. The user modified their interaction behavior according to the system’s suggestions, including scheduling door-opening events, optimizing the timing of food placement, and minimizing unnecessary thermal disturbances. The impact of this AI-assisted behavioral adaptation was then assessed by repeating the same measurement procedure under comparable conditions and directly comparing the resulting electric current profiles and cumulative energy consumption.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, two experimental scenarios were defined:

- (1)

- An Extreme Scenario, in which additional thermal loads and frequent interactions were deliberately introduced to stress the system.

- (2)

- A Normal Scenario, reflecting typical household usage patterns.

For each scenario, two operating modes were considered: conventional user behavior (without AI assistance) and AI-assisted user behavior. This experimental design enabled a direct quantitative comparison of energy consumption, compressor activity, and operational stability between both approaches.

In this study, the experimental setup utilizes a domestic refrigerator–freezer intended for a four-person household, with a rated electrical power of 175 W. The appliance offers a net storage capacity of 246 L in the fresh-food compartment and 63 L in the freezer compartment. Both compartments are equipped with an independently operable super-freezing function. According to the manufacturer’s nameplate specifications, activation of the super-freezing mode results in an average current draw of approximately 1.6 A. All experiments were performed under controlled ambient conditions at 20 °C.

The following subsections detail the data collection architecture, the interaction between the monitoring system and the LLM, the AI-assisted user strategy, and the results obtained under both experimental scenarios.

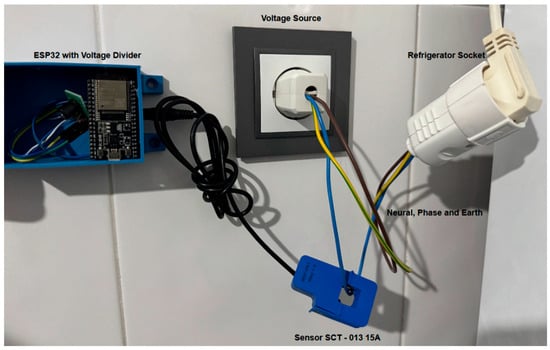

5.1. Physical Prototype

Figure 6 illustrates the equipment used throughout the project. It presents a system designed to measure electrical energy using an ESP32 microcontroller. The ESP32 board is housed within a blue enclosure and connected to a voltage divider circuit composed of resistors, which allows for safe measurement of the electrical signal. The voltage source (wall outlet) serves both as the power supply and as the reference point for energy consumption measurements. The refrigerator outlet represents the monitored load, as the refrigerator’s power consumption is the primary variable of interest. The system wiring includes neutral, live, and ground conductors, corresponding to the blue, brown, and yellow/green wires, respectively. A SCT-013 Electric Current Sensor (15 A), a electric current transformer clamped around the live wire, is employed to measure the electric current flow. Overall, Figure 7 depicts an IoT-based monitoring system that highlights each essential component used in this study.

Figure 6.

ESP32 microcontroller panel with SCT-013 electric current sensor used to measure household appliance energy consumption.

Figure 7.

Materials used in architecture.

Figure 7 represents an overview of the hardware components integrated into the IoT-based energy monitoring architecture, including the ESP32 microcontroller, voltage divider circuitry, and SCT-013 electric current sensor, which together enable accurate real-time measurement of electrical parameters for household energy analysis. The Raspberry PI is used as a local server to host the database and management services and the MQTT broker responsible for receiving messages from the current sensor, while the wireless router provides the network interconnection between the monitoring nodes and the data storage, and processing infrastructure.

5.2. Data Collection and Storage Services

This section introduces the services running on a Docker-based infrastructure, which ensures modularity, scalability, and simplified deployment for smart home applications. Among the containerized services is a module responsible for reading data from an SCT-013 electric current sensor, used to monitor the energy consumption of a refrigerator. This sensor provides real-time electric current measurements, which are processed locally and made available for further analysis.

To enhance intelligence and contextual understanding, the system integrates with a Large Language Model (LLM) hosted in the cloud. This model receives structured data from the sensor and can reason over it, identifying patterns, detecting anomalies, and generating insights based on historical usage and user behavior. The cloud-based nature of the LLM allows for scalable processing and access to advanced AI capabilities without requiring local computational resources.

Complementing this setup is a chatbot interface, which enables users to interact with the system using natural language. Through the chatbot, users can ask questions about their energy consumption, receive personalized suggestions, or even control devices. The chatbot acts as a bridge between the user and the intelligent backend, making the system more intuitive and accessible.

Together, these components demonstrate how containerized services, sensor data, and cloud-based AI can work in synergy to create a responsive and intelligent energy management environment.

All Docker services run in isolated containers, making the system easier to maintain and deploy; the services can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Services running in Docker.

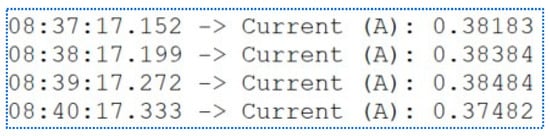

Figure 9 presents a sequence of electric current measurements recorded from the refrigerator over a period of several minutes. Each time-stamped entry reports the instantaneous electric current consumption in amperes. Overall, the data illustrates the refrigerator operating in a stable regime with slight variations in electric current. These measurements were consistently applied at all data collection points throughout this section, and the values shown here represent only a short excerpt of the recorded dataset. The LLM leverages the data presented in Figure 9 as a reference to process and interpret information regarding the refrigerator’s electric current consumption.

Figure 9.

Extract of time-series data of the refrigerator electric current consumption.

5.3. Analyze Consumption Pattern—Prompt 1

To understand the energy behavior of a domestic refrigerator, a large volume of data was collected, relating to electric current over time. To extract relevant patterns and automate the analysis, a large-scale language model (LLM) was applied, capable of interpreting time series and identifying operational states based on consumption variations.

The LLM was able to distinguish four main operating states: Start-up peak, compressor running, standby mode, and events where the refrigerator door was opened. The data was segmented into complete refrigeration cycles. This approach enabled efficient and contextualized analysis, revealing not only periods of compressor activity but also transitions between states with high precision.

The LLM was prompted to generate a comprehensive summary grounded in the data it possessed. The following are the responses produced by the LLM.

Prompt: “Analyze the global data”

LLM answer:

Overall Summary

On State (Compressor Running): The electric current draw is generally between 0.40 and 0.80 A. This corresponds to a power consumption of approximately 75 to 150 W.

Off State (Standby): The consumption is very low, typically between 0.03 and 0.07 A. This represents the appliance’s electronics and perhaps an LED, consuming about 5 to 10 W.

Startup Peak (Inrush Current): When the refrigerator was first measured, the compressor motor generated a very high current spike, which in your case reached 5.25 A. This is normal and lasts only a fraction of a second.

Door Opening: Opening the door causes an immediate increase in consumption, as the internal light turns on and, more importantly, the compressor is activated to compensate for the inflow of warm air.

Detailed Event Analysis

The log can be broken down into key parts to clarify what occurred.

Measurement Start and First Cycle (20:53–21:19)

20:53–20:58: Immediately after connecting the sensor, the current values are high and unstable (3.243.24 A, 3.523.52 A, 5.255.25 A, 1.051.05 A). This is the startup peak of the compressor. The motor needs a lot of energy to start running.

20:59–21:18: The consumption stabilizes around 0.40 A. This is the normal operating mode of the compressor, maintaining the cold temperature.

21:19: The current drops drastically to 0.07 A. The compressor turned off because the refrigerator reached the desired temperature.

Cooling cycle duration: Approximately 25 min.

Standby Period (21:19–21:50)

During this period, the current remains very low, mostly around 0.04 A. The refrigerator is in standby mode, just monitoring the temperature.

Standby period duration: Approximately 31 min.

Second Cooling Cycle (21:51–22:16)

21:51: The current rises to 0.67 A. The compressor turned on again to start a new cooling cycle.

21:51–22:15: Consumption remains stable around 0.65 A.

22:16: The current drops back to 0.03 A, indicating the compressor turned off.

Cooling cycle duration: 25 min.

Previous standby period duration: 32 min.

The pattern repeats throughout the night: The refrigerator alternates between cooling cycles (ON) of about 25–30 min and standby periods (OFF) of about 30–40 min.

Key Event: Opening the Door (08:47–09:10)

08:46: The refrigerator was in standby (0.03 A).

08:47: You noted “abri o frigorífico” (I opened the fridge), and the current immediately rises to 0.68 A.

Analysis: This increase is not just from the internal light bulb (which would consume about 0.1 A). The inflow of warm air caused the thermostat to immediately activate the compressor to compensate for the cold loss.

08:47–09:09: Consumption remains high (between 0.63 A and 0.81 A) while the door is open. The compressor is working continuously to combat the incoming warm air.

09:10: The current drops to 0.05 A. This indicates the door was closed, and the cooling cycle finished shortly after.

5.4. Energy and Cost Estimate—Prompt 2

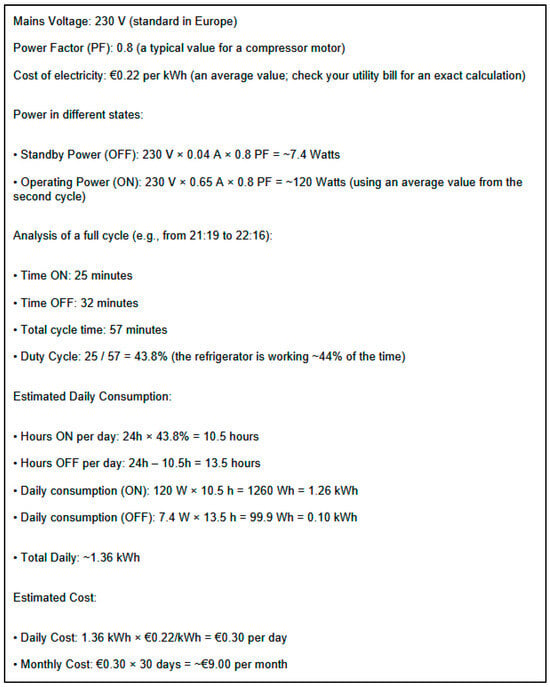

To better understand the energy consumption of a domestic refrigerator, a detailed electric current monitoring process was performed. Using the collected data, key operating states were identified and analyzed, including standby, active cooling, start-up peaks, and door-opening events. Based on this analysis, it was possible to estimate the refrigerator’s energy consumption and associated costs, posing the prompt “An estimate of consumption was requested based on the data”. The corresponding answer is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

LLM output: estimated daily consumption.

Output generated by the LLM (Google AI Studio) computing the refrigerator estimated energy usage. Based on measured current, and duty cycle, the model predicts an average daily consumption of approximately 1.36 kWh, corresponding to a cost of about €0.30 per day.

Applying standard electrical assumptions, such as a voltage of 230 V, a power factor of 0.8, and an average electricity cost of €0.22 per kWh in Portugal, the energy consumption in each state was calculated. It was found that the refrigerator operates at a duty cycle of approximately 44%, which is typical for this type of appliance.

This data-driven approach allowed for the estimation of daily, monthly around 9€, and annual energy consumption and costs, providing valuable insights into the device’s efficiency and the impact of user behavior, such as frequent door opening and its duration time.

5.5. Impact of User Behavior on Energy Efficiency—Prompt 3

This section presents key insights derived from real-time electric current measurements of a refrigerator, highlighting user behavior, which directly impacts energy consumption. The data reveals that the refrigerator reacts immediately and intensely to temperature changes, especially when warm air or hot food is introduced.

Three main conclusions were drawn:

Instantaneous Heat Response—the compressor activates immediately upon detecting a temperature increase when the door is opened or hot food is placed inside.

High Cost of Long Cooling Cycles—prolonged compressor activity, especially after storing large quantities of hot food, leads to significantly higher energy consumption.

Time Matters—activating cooling cycles during off-peak hours can reduce costs without compromising performance.

These findings support a data-driven strategy to minimize energy consumption by dividing hot food into shallow containers and storing it during off-peak hours. This approach reduces both the duration and the cost of energy-intensive cooling cycles.

A question was asked to the Google AI Studio chatbot, which is LLM Gemini.

The question was “What is the best time to put food in the refrigerator?”

LLM answer:

The refrigerator reacts instantly and energetically to heat.

This is the most important piece of information revealed by your data.

The evidence:

At 12:46 AM, the refrigerator was idle, consuming only 0.03 A. The moment the door was opened at 12:47 AM, introducing warm air, the compressor immediately activated, and the electric current peaked at 0.68 A—an increase of more than 20 times.

What this means:

The refrigerator has no delays. It is designed to counteract any temperature rise. Placing hot food inside will trigger a long, energy-intensive cooling cycle. You can’t prevent this energy spike; you can only control when it happens and how long it lasts.

A long cooling cycle is expensive. Their data shows two distinct states: a very low-power standby mode (<0.04 A) and a high-power operating mode (≈0.40 A to 0.80 A).

The Evidence:

The compressor operating at 0.7 A consumes about 15 to 20 times more energy than in standby mode. A large pot of hot food represents a significant thermal load, forcing the compressor to remain in high-power mode for an extended period.

What this means:

Reducing the duration of this high-power cycle is crucial to saving energy and money. A single deep pot keeps the compressor running for hours. Dividing food into shallow containers increases surface area, allowing it to cool more quickly and significantly shortening the high-power cycle.

Time is of the essence for cost.

The refrigerator runs just as hard at 8 PM as it does at 11 PM, but the cost of this work can vary dramatically.

The Evidence:

In typical time-of-use pricing plans, running the compressor during peak hours results in higher costs.

What this means:

Since all energy spikes are inevitable, the smartest financial strategy is to run them during off-peak hours (typically after 10 p.m.). You’ll pay much less for the same amount of energy.

The “Best Time” Strategy is proven by collected data

Here’s a perfect, data-driven plan for storing food:

Action (Immediately after cooking):

Divide hot food into smaller, shallow containers.

Data-Based Reason:

To minimize the length of energy-intensive cooling cycles. Less runtime means fewer total kWh used.

5.6. Refrigerator Consumption—Extreme Scenarios

The aim of this comparison is to assess how user interaction with a domestic refrigerator–freezer affects its electrical consumption profile. The extreme scenarios correspond, on one hand, to a careless and unregulated use (without AI). On the other hand, to a usage that users strictly follow AI recommendations adheres to all established rules (with AI).

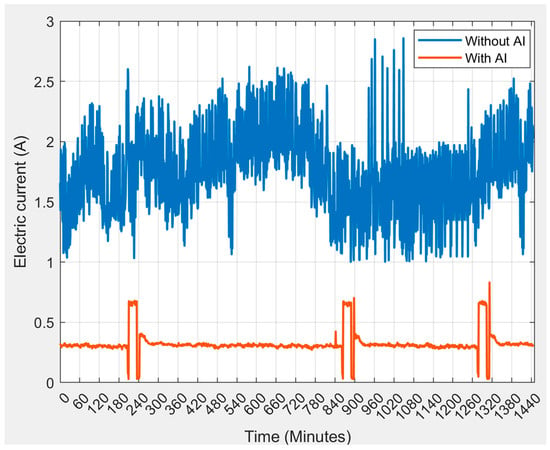

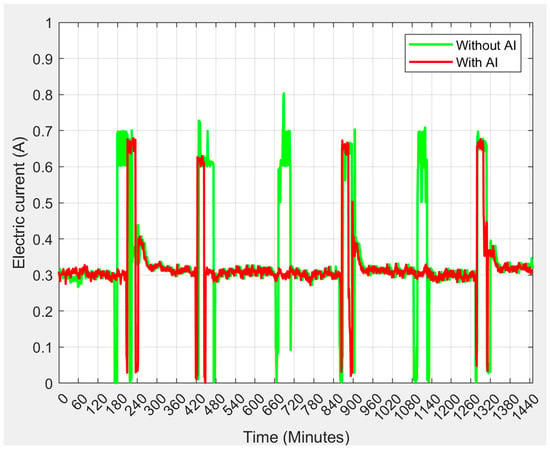

Figure 11 shows the 24 h electric current measurements for two experimental scenario conditions, referred to as without AI-assistance and with AI-assistance.

Figure 11.

Comparative measurement outcomes obtained with and without AI-assistance.

The horizontal axis represents time in minutes over a complete 24 h period, where minute 0 corresponds to 00:00 at the beginning of the experiment and minute 1440 corresponds to 00:00 of the following day. The vertical axis indicates the measured electric current drawn by the refrigeration system in amperes.

During the experiments, both the refrigerator and the freezer compartments were in operation. The refrigerator was subjected to a fully loaded condition, caused by the introduction of additional food load, in order to evaluate the system behavior under more demanding and realistic operating conditions. Moreover, the super-freezing mode of the freezer was manually activated, increasing compressor activity and electrical demand to accelerate the freezing process and further intensify the operating conditions.

On the day without AI, the appliance was used following typical household behavior, with door openings occurring at arbitrary times and without any energy-efficiency considerations. This behavior is reflected in the blue trace, which exhibits pronounced and frequent fluctuations, typically ranging between 1.2 A and 2.6 A. These peaks correspond to compressor activations triggered by door openings, combined with the effects of thermal disturbances, the additional thermal load, and the activated super-freeze mode. The resulting current profile indicates repeated disruptions to the thermal balance, forcing the compressor to operate more frequently and at higher intensity.

In contrast, on the day with AI, a controlled interaction protocol was implemented. Door-opening events were scheduled based on recommendations provided by a chatbot-based advisory system, which identified optimal time intervals for refrigerator access and for placing additional products (e.g., meat) into the freezer for rapid cooling. As a result, the orange trace remains significantly lower and more stable, mostly within the range of 0.3–0.4 A, with only a small number of short-duration peaks associated with the scheduled interactions.

The comparison demonstrates that, even under dual-compartment operation, fully loaded, and super-freezing conditions, optimized user interaction significantly reduces compressor workload and electric current demand. Specifically, the AI-assisted scenario achieved a reduction of approximately 82.7% in average current and more than 80% in standard deviation, indicating improved operational stability. Furthermore, the number of high-current peaks was reduced by approximately 95%, confirming the ability of the proposed AI-based advisory framework to mitigate transient electrical stress and enhance overall energy efficiency without compromising refrigeration functionality.

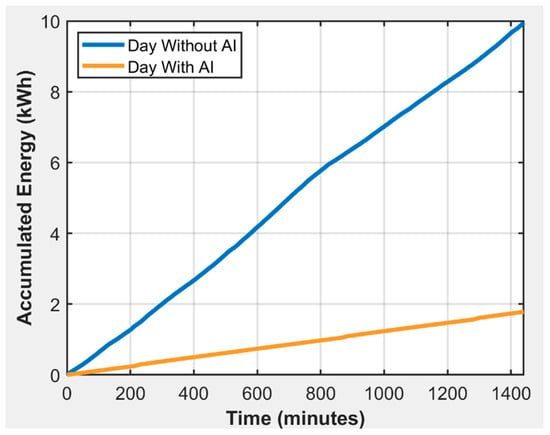

Impact of AI Assitance on Energy Consumption Under Extreme Operating Conditions

Figure 12 compares energy consumption over a full 24 h period under an extreme operating scenario, with and without AI-assistance. The blue curve represents the baseline case (day without AI), showing a steady and steep increase in cumulative energy demand, reaching nearly 10 kWh by the end of the day. In contrast, the orange curve corresponds to the AI-assisted scenario, where intelligent energy management significantly reduces overall demand, limiting the total energy consumption to approximately 1.79 kWh. The results clearly demonstrate the strong potential of AI-driven optimization strategies in mitigating energy usage under extreme conditions, leading to substantial improvements in system efficiency and energy savings.

Figure 12.

Extreme scenario: accumulated energy consumption with and without AI-assistance.

5.7. Refrigerator Consumption—Normal Scenarios

To complement the analysis of the extreme operating scenarios, this section focuses on the evaluation of typical daily usage. In the scenario without AI-assistance, the user follows a normal usage of the refrigerator. On the other hand, when employing AI, we follow the prescribed rules whenever feasible, without compromising the practical demands of everyday life. The objective is to assess whether the benefits observed under stressed conditions are also maintained in a realistic daily environment, where user behavior follows typical domestic routines and thermal disturbances occur in a more natural and less intensive manner.

By comparing the electric current profiles of the refrigerator operating with and without AI-assistance user guidance during a standard working day, this section aims to quantify the influence of behavioral optimization on both energy consumption and system stability. This comparison provides a more representative assessment of the applicability and effectiveness of the proposed approach in real-world residential contexts (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Electric current collected in a normal day with and without AI-assistance.

The horizontal axis represents time in minutes over a complete 24 h period, ranging from minute 0 (00:00) to minute 1440 (00:00 of the following day). The vertical axis shows the measured electric current in amperes. The figure compares the electrical behavior of the refrigeration system during a normal operating day without AI assistance and a day under AI-assisted control.

During the day without AI, the refrigerator was used according to typical household behavior, with door openings occurring at arbitrary times without any consideration for energy efficiency. This operating mode is represented by the green curve. Although the baseline current remains relatively low (around 0.3–0.4 A), several pronounced current peaks are observed, reaching values close to 0.7–0.8 A. These peaks are associated with compressor activation triggered by thermal disturbances caused by door openings and changes in internal thermal load. The irregularity and frequency of these current surges indicate repeated disruptions of the thermal equilibrium, forcing the refrigeration system to operate more frequently in order to recover its target conditions.

In contrast, during the AI-assisted day (red curve), the refrigerator usage followed a controlled interaction schedule. Door openings were planned according to recommendations provided by an AI chatbot, which suggested optimal times for accessing the refrigerator and for placing food items, such as meat, into the freezer to optimize their cooling process. As a result, the current profile exhibits a significantly smoother and more stable behavior, remaining close to 0.3–0.35 A for most of the day. Only a limited number of short-duration peaks are visible, corresponding to the scheduled interaction events.

These results demonstrate that reducing the frequency and randomness of door openings leads to fewer thermal disturbances and, consequently, a decrease in compressor cycling activity. The AI-assisted strategy therefore contributes to a more stable electrical profile and a reduction in transient current peaks.

Overall, the comparison highlights the potential of intelligent advisory systems to actively influence user behavior and promote more energy-efficient operation of domestic refrigeration appliances. In addition to lowering the average current demand, the AI-based approach significantly reduces current variability and the occurrence of transient peaks, contributing to improved energy efficiency and reduced electrical stress on the system components.

Impact of AI Assistance on Energy Consumption

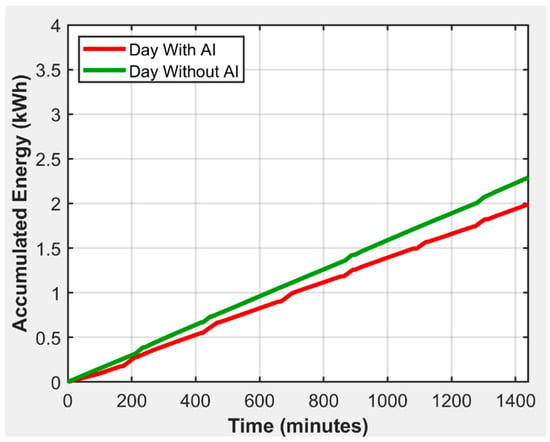

Figure 14 illustrates the time evolution of the accumulated electrical energy consumption of the refrigeration system under conventional utilization (without AI) and AI-assisted utilization (with AI). The accumulated energy profiles were obtained through the cumulative integration of the measured electrical power signals recorded during the experimental tests.

Figure 14.

Electrical energy consumption of the refrigeration system over 24 h under conventional and AI-assistance.

As observed in the figure, both operating modes exhibit a gradual increase in accumulated energy over time. However, the conventional utilization strategy presents a consistently higher energy accumulation rate, as indicated by the steeper slope of the green curve. This behavior reflects a higher and more continuous power demand of the refrigeration system when operated without AI assistance.

In contrast, the AI-assisted utilization demonstrates a lower accumulated energy trajectory throughout the entire operating period. The red curve shows a smoother and less steep profile, indicating a reduced energy consumption rate under AI supervision. This difference suggests that the AI-assistance optimizes the compressor operation, reducing either its duty cycle or its power demand while maintaining stable system performance.

Overall, the results shown in Figure 14 confirm that the proposed AI-assistance strategy leads to a reduction in electrical energy consumption compared to the conventional approach, without compromising the operational stability of the refrigeration system.

5.8. Results and Discussion

This section presents a consolidated quantitative evaluation of the experimental results obtained throughout the study, with a particular focus on the Extreme Scenario, which was designed to represent a worst-case operating condition with intensified thermal disturbances and user interactions. The objective is to summarize, in a comparative and structured manner, the impact of AI-assisted user behavior on the electrical performance and energy consumption of the refrigeration system under these stressed conditions.

Key performance indicators were extracted from the measured current signals and analyzed for both operating modes (without AI and with AI control) over a full 24 h period. The selected metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of energy efficiency, compressor activity, and electrical stability, allowing the effectiveness of the proposed AI-based user guidance strategy to be quantitatively evaluated under maximum operational stress.

Table 1 presents a quantitative comparison between the refrigeration system operating under conventional and AI-assisted utilization over a 24 h period, based on real current measurements sampled at 1 min intervals.

Table 1.

Impact of AI utilization on the energy consumption and operational behavior of the refrigeration system (extreme and normal scenarios).

The results indicate a substantial improvement in both energy consumption and operational behavior when AI-based guidance is applied. The total daily electrical energy consumption decreased from 9.64 kWh in the conventional operating mode to 1.79 kWh under AI assisted utilization, corresponding to a reduction of 81.4%, in case of extreme scenarios. On the other hand, in the case of normal scenarios the total daily electrical energy consumption decreased from approximately 2.28 kWh under conventional operation to 1.97 kWh with AI assistance, corresponding to a reduction of 13.6%. The cumulative compressor-related activity time, defined as the total duration for which the measured current exceeded the compressor activity threshold (I > 0.4 A), was reduced from approximately 24 h to 1.28 h, representing a reduction of 94.7%, in case of extreme scenarios This reflects a strong decrease in the compressor duty cycle while maintaining the required operational performance. In the case of normal scenarios, a reduction of 47.9% was observed (the value decreased from approximately 4.8 h to 2.5 h).

Furthermore, in the extreme scenarios, the number of compressor cycles decreased from approximately 120 cycles under conventional utilization to only 3 cycles with AI assistance, corresponding to a reduction of 97.5%. On the other hand, in the case of normal scenarios the number of compressor cycles decreased from approximately 6 cycles under conventional utilization to only 4 cycles with AI assistance, corresponding to a reduction of 33.3%. This reduction is expected to decrease mechanical wear, potentially extending compressor lifetime and improving overall system reliability.

Finally, the maximum measured current peak decreased from 2.86 A to 0.83 A (−70.9%) for the extreme scenarios and reduced from 0.81 A to 0.67 A representing a decrease of 17.3% in the case of normal scenarios, indicating smoother and more stable electrical behavior under AI, which is beneficial from both power quality and component protection perspectives.

Additionally, the standard deviation of the measured current signal was significantly lower under AI assistance, reflecting reduced electrical variability and a more stable operating regime.

6. Conclusions

Despite significant technological advancements, current Smart Home solutions frequently suffer from critical limitations: user interaction remains confined to rigid commands and predefined interfaces. This restricts contextual intelligence, adaptability, and effective energy management. This work addresses this gap by proposing a novel architecture that integrates Internet of Things (IoT) sensing, Artificial Intelligence (AI) analytics, and a conversational interface powered by a Large Language Model (LLM). The primary objective was to transform Smart Homes into responsive ecosystems where residents actively participate in energy optimization through natural, context-aware interactions.

The proposed system was experimentally validated on a domestic refrigerator-freezer. The results demonstrated the system’s capability to identify operational inefficiencies and guide user behavior effectively. In comparison to unassisted operation, the AI-guided approach yielded energy consumption reductions of approximately 13.6% (from 2.28 kWh to 1.97 kWh) in normal usage scenarios and up to 81.4% under extreme stress scenarios, from 9.64 kWh to 1.79 kWh. These efficiency gains were underpinned by a drastic optimization of the compressor’s duty cycle. In extreme conditions, cumulative compressor activity time decreased by 94.7% (dropping from ~24 h to 1.28 h), while normal conditions saw a 47.9% reduction (4.8 h to 2.5 h), maintaining required thermal performance with significantly less resource usage.

Analysis of the electric current profiles revealed distinct operational differences between the baseline and the AI-assisted scenarios. In the absence of assistance, frequent thermal disturbances caused by unregulated door openings triggered intense and frequent compressor cycles. The AI-guided interaction minimized compressor stress, reducing the number of cycles from approximately 120 to just 3 (−97.5%) in extreme cases, and from 6 to 4 (−33.3%) in normal scenarios. Conversely, the AI-assisted scenario resulted in a significantly more stable current profile. The analysis of electrical signatures confirmed a smoother operational profile: maximum current peaks were mitigated by 70.9% (2.86 A to 0.83 A) in extreme scenarios and by 17.3% (0.81 A to 0.67 A) in normal use.

By mitigating thermal intrusions through proactive user guidance, the system not only reduced immediate energy demand but also minimized high-amplitude transient events. This reduction in current variability suggests a potential benefit regarding lower mechanical wear and increased compressor lifespan, highlighting that intelligent guidance impacts both energy efficiency and long-term equipment reliability.

Beyond measurable energy savings, architecture enhances system transparency and user empowerment. By providing actionable insights through dashboards and a conversational chatbot, residents retain control while benefiting from proactive, explainable recommendations. This balance between automation and human oversight fosters a more resilient and ecologically responsible domestic environment.

In conclusion, this research successfully bridges the gap between static automation and dynamic user empowerment. Future work will focus on extending this validation to multi-appliance environments, exploring interoperability across heterogeneous platforms, and evaluating the long-term impacts on aggregate household energy savings and user satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., J.R. and P.C.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, J.R., M.G. and P.C.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, J.R. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., J.R., M.G. and P.C.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, J.R. and P.C.; project administration, P.C.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sharma, N.; Shamkuwar, M.; Singh, I. The History, Present and Future with IoT. In Internet of Things and Big Data Analytics for Smart Generation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Colmenares-Quintero, R.F.; Maestre-Gongora, G.; Valderrama-Riveros, O.C.; Baquero-Almazo, M.; Stansfield, K.E. A Data-Driven Architecture for Smart Renewable Energy Microgrids in Non-Interconnected Zones: A Colombian Case Study. Energies 2023, 16, 7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Khan, S.U.; Zaheer, R.; Khan, S. Future internet: The internet of things architecture, possible applications and key challenges. In Proceedings of the 2012 10th International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, 17–19 December 2012; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A.; Lee, K.-T.; Kim, D.-H. Energy Prediction and Optimization for Smart Homes with Weather Metric-Weight Coefficients. Sensors 2023, 23, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotti, L.; Guizzardi, D.; Barricelli, B.R.; Fogli, D. Enabling End-User Development in Smart Homes: A Machine Learning-Powered Digital Twin for Energy Efficient Management. Future Internet 2024, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, L.L.; Ferreira, L.C.B.C.; Cabral, T.W.; Lemes, D.A.M.; Cardoso, G.d.S.; Borchardt, A.; Cardieri, P.; Fraidenraich, G.; de Lima, E.R.; Neto, F.B.; et al. General Overview and Proof of Concept of a Smart Home Energy Management System Architecture. Electronics 2023, 12, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Yu, X. A hybrid forecasting approach for China’s national carbon emission allowance prices with balanced accuracy and interpretability. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Ma, M.; Zhou, N.; Feng, W.; Xiang, X.; Mao, C. Towards COP27: Decarbonization patterns of residential building in China and India. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSalvo, C.; Sengers, P.; Brynjarsdóttir, H. Mapping the landscape of sustainable HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 1975–1984. [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa, R.; Azizpour, H.; Leite, I.; Balaam, M.; Dignum, V.; Domisch, S.; Felländer, A.; Langhans, S.D.; Tegmark, M.; Fuso Nerini, F. The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, L.Å.E.J.; Cerratto Pargman, T.; Pargman, D.S. A Decade of Sustainable HCI: Connecting SHCI to the Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, D.-Y.; Yang, B. Smart home research. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics, Shanghai, China, 26–29 August 2004; pp. 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Erol-Kantarci, M.; Mouftah, H.T. Wireless sensor networks for cost-efficient residential energy management in the smart grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-M.; Lim, J.-H. Smart home energy management system using IEEE 802.15.4 and ZigBee. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2010, 56, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanchery, S.; Rakesh, N. Smart power socket using internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 26–28 February 2020; pp. 1060–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-B.; Huang, C.-M.; Chen, L.-K.; Sung, G.-N.; Yang, C.-C. Morsocket: An expandable IoT-based smart socket system. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 53123–53132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskon, M.T.; Hasry, M.A.H.; Rosle, M.S.; Danial, A.; Hidayah, A. IoT-enabled electric socket test bed utilizing IFTTT and Node-RED. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Knowl. 2019, 9, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Saver U.S. Department of Energy’s Consumer Resource on Saving Energy. 2018. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/save-electricity-and-fuel/appliances-and-electronics/estimating-appliance-and-home (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Hoak, D.E.; Parker, D.S.; Hermelink, A.H.; Florida Solar Energy Center. How Energy Efficient Are Modern Dishwashers; Florida Solar Energy Center: Cocoa, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio, A.; Pimpinella, L.; Quaresima, A.; Curti, S. An event driven smart home controller enabling cost effective use of electric energy and automated demand sidemanagement. In Proceedings of the 19th Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation (MED), Corfu, Greece, 20–23 June 2011; pp. 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrasa, M.A.A.; Spooner, T.D.; MacGill, I.F. Coordinated scheduling of residential distributed energy resources to optimize smart home energy services. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2010, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Large language models (LLMs): Survey, technical frameworks, and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; de Freitas Rocha Loures, E.; Deschamps, F. Industrial Internet of Things: A Systematic Literature Review and Insights. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4515–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Zahoor, S.; Shah, M.A.; Wahid, A.; Yu, H. Green IoT: An Investigation on Energy Saving Practices for 2020 and Beyond. IEEE Access 2025, 5, 15667–15681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albreem, M.A.; Sheikh, A.M.; Alsharif, M.H.; Jusoh, M.; Mohd Yasin, M.N. Green Internet of Things (GIoT): Applications, Practices, Awareness, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2025, 9, 38833–38858. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Leung, V.C.M.; Shu, L.; Ngai, E.C.-H. Green Internet of Things for Smart World. IEEE Access 2025, 3, 2151–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, B.; Ben Slama, S. PV-EV integrated home energy management using vehicle-to-home (V2H) technology and household occupant behaviors. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 44, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]