Abstract

Thermal energy storage using latent heat storage materials represents a promising solution for stabilizing low-temperature energy systems; however, its effectiveness is limited by the low thermal conductivity of phase change materials (PCM), particularly salt hydrates such as sodium acetate trihydrate (SAT). The objective of this work is to analyze to what extent vertical gradation of a metallic gyroid structure can enhance heat transfer and temperature homogeneity in the PCM during charging. Time-dependent numerical simulations of conjugate heat transfer were performed for three gyroid variants differing in the orientation of pore gradation, modeling heat transfer between the flowing water, the aluminum gyroid structure, and the solid phase of SAT until the PCM reached a temperature of 58 °C. The results showed that the orientation of the gradation significantly affects both the heating dynamics and the quality of the temperature field. The variant with enlarged pores in the region of contact with the fluid and gradually decreasing pores toward the PCM achieved the shortest time to complete heating, the lowest temperature amplitude, and the highest degree of temperature homogeneity. This variant also exhibited the highest energetic efficiency, expressed as the ratio of transferred heat to pressure drop. The study demonstrates that deliberately designed gyroid gradation can substantially improve the performance of PCM composites without increasing the amount of material and represents a promising pathway for the development of advanced thermal storage systems.

1. Introduction

Thermal energy storage represents one of the key technologies in 21st-century energy systems. With ongoing decarbonization, the increasing share of renewable energy sources (RES), and significant daily or seasonal fluctuations in heat demand, the ability to temporarily store and subsequently reuse thermal energy has become essential for the stability and efficiency of many modern thermal systems [1,2,3]. Heating networks, solar thermal collectors, waste-heat recovery technologies, and low-temperature industrial applications all experience a mismatch between instantaneous thermal production and time-shifted consumption [4]. Thermal storage units mitigate this imbalance by accumulating excess heat during periods of surplus and releasing it during demand peaks, which increases RES utilization [5], reduces system losses [6], and improves energy flexibility. Among the available storage methods, latent heat storage offers substantially higher volumetric energy density than sensible heat storage, since energy is absorbed or released during the phase transition of the material [7,8].

Phase change materials (PCMs) suitable for low-temperature applications include paraffins, fatty acids, inorganic salts, and salt hydrates. Sodium acetate trihydrate (SAT) is one of the most promising representatives of this group due to its melting temperature of approximately 58 °C and latent heat of about 260 kJ·kg−1 [9,10]. Despite these advantages, SAT exhibits very low thermal conductivity in the solid state—typically 0.4–0.6 W·m−1·K−1—which severely limits its charging speed and causes pronounced thermal stratification [11]. Consequently, extensive research has been devoted to enhancing the effective thermal conductivity of PCMs. Strategies include nanoparticles or graphite additives, extended surfaces, or metallic fins, but increasingly focus on introducing three-dimensional porous metallic structures such as metal foams, graphite foams, or architected lattices. Numerous experimental and numerical studies confirm the benefits of these structures.

Shi et al. (2023) [12] published a comprehensive review analyzing various configurations of metal foam structures embedded in PCM composites. Their findings showed that metal foams substantially reduce charging time and improve the homogeneity of the temperature field, with the magnitude of the effect strongly dependent on the porosity and specific surface area of the metallic matrix. Ghahremannezhad et al. (2020) [13] conducted a numerical study of PCM embedded in non-homogeneous metal foam, in which they varied the local porosity and anisotropy of the metallic skeleton. Their results indicate that directional gradation of porosity can lead to optimization of local thermal pathways and to simultaneous improvement of both thermal and hydraulic performance. Experimental studies confirm the effectiveness of these structures under real operating conditions. Baccega et al. (2025) [14] investigated paraffin impregnated in metal foam with different pores per inch values and observed an increase in effective thermal conductivity by several tens of percent compared to pure PCM. Similar experiments were conducted by Falcone et al. (2022) [15], who used a copper metal foam with a porosity of approximately 95%. Their measurements showed that the integration of the foam significantly accelerated the PCM melting process and reduced thermal stratification within the composite. Kotb et al. (2022) [16] focused on thermal regulation of PCM using metal foams and confirmed that the metallic matrix acts as a stabilizing element, suppressing overheating and promoting a more uniform temperature profile during charging cycles. Observations from literature are further supported by modeling studies. Naldi et al. (2022) [17] evaluated the effective thermal conductivity of metal foam–PCM composites using homogenization methods. They demonstrated that composite conductivity exhibits a nonlinear dependence on porosity, with the optimal balance between metal volume fraction and thermal gains determined by operating temperature levels. Chen et al. (2019) [18] developed a detailed numerical model of a thermal energy storage tank containing metal foam integrated around both the heat-transfer fluid and the PCM, showing a substantial acceleration of the charging process, particularly under low temperature gradients. At the microscale, valuable insights were provided by the study of Wang et al. (2018) [19], who investigated PCM melting in metal foam using a pore-scale CFD model. The authors demonstrated that heat propagation within the PCM is not homogeneous but occurs preferentially along the metallic skeleton, confirming the importance of a continuous three-dimensional thermally conductive matrix. Khan et al. (2025) [20] experimentally tested PCM–metal foam composites with different pores per inch values and confirmed that structures with higher pore density exhibit a faster melting process, albeit at the cost of increased pressure losses during fluid flow. Grosu et al. (2020) [21] examined macro-nanoporous metallic structures impregnated with PCM.

Despite these advances, most published PCM–metal-matrix studies use homogeneous foams or uniform porous structures. Much less attention has been given to controlled spatial gradation of porosity—particularly in architected geometries such as triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS). Among TPMS, the gyroid is especially attractive due to its high specific surface area, smooth curvature, continuous three-dimensional skeleton, and excellent hydraulic behavior [22]. Its periodicity allows precise adjustment of pore size and wall thickness, enabling the design of thermally conductive inserts with tailored heat-transfer characteristics. Furthermore, modern additive manufacturing techniques such as selective laser melting (SLM) and direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) now allow reliable fabrication of complex gyroid structures, including graded variants, which were difficult or impossible to manufacture in the past [23,24,25,26,27]. However, the influence of vertically graded gyroid structures on heat transport in low-conductivity PCMs such as SAT remains unexplored.

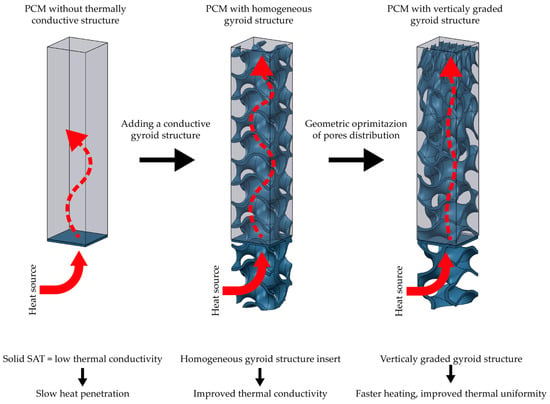

The presented study addresses this gap by numerically analyzing a thermal energy storage concept in which the SAT volume is complemented with a vertically graded gyroid structure. Three configurations were evaluated: a homogeneous reference gyroid and two graded variants with opposite pore-size distributions. Using transient simulations, the study quantifies heat penetration, thermal homogenization, and charging behavior up to the critical temperature of 58 °C. To clarify motivation and problem definition, Figure 1 provides an introductory schematic illustrating the low thermal conductivity of solid SAT and the role of a conductive TPMS structure in accelerating heat transport. The results of the presented study offer new insight into how geometrical gradation within a TPMS structure influences the thermo-physical response of PCM systems, contributing to the development of more efficient and manufacturable thermal storage units.

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration of the problem addressed in this study (left) slow heat penetration in solid SAT due to low thermal conductivity; (center) partial improvement with homogeneous gyroid structure; (right) proposed concept of vertically graded gyroid for enhanced thermal conduction and accelerated PCM heating.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometry and Boundary Conditions of the Numerical Analysis

The study was carried out using numerical simulations of heat transfer and fluid flow inside a composite thermal storage unit consisting of a channel with flowing liquid and a PCM block filled with a metallic gyroid structure. The simulation model was designed to enable comparison of three different geometric variants of the gyroid, while the fundamental dimensions of the computational domain, material properties, and boundary conditions were kept identical for all cases. The primary objective was to evaluate the influence of pore gradation within the gyroid structure on heat transfer into the PCM, the homogeneity of the temperature field, and the hydraulic behavior of the fluid flowing through the channel.

The basis of all the structures investigated was the ideal gyroid surface. In its dimensionless form, it can be expressed by the implicit Equation (1) [28].

where x, y, and z are spatial coordinates normalized to the gyroid period, and C is the selected isosurface constant. For C = 0, the surface represents an ideal minimal surface with zero mean curvature, which, when appropriately scaled, forms a continuous three-dimensional skeleton. In the numerical model, this base shape was implemented as a level-set surface that was subsequently transformed into physical coordinates x, y, z with the required period in the z-direction. From the resulting surface, a volumetric model of the gyroid was created by symmetrically offsetting the surface by a constant wall thickness of 0.5 mm, thereby generating a continuous metallic structure capable of conducting heat. The thus-defined base gyroid was trimmed using a bounding envelope with a footprint of 10 × 10 mm and a height of 45 mm to ensure direct integration into the PCM domain.

sin(x)cos(y) + sin(y)cos(z) + sin(z)cos(x) = C,

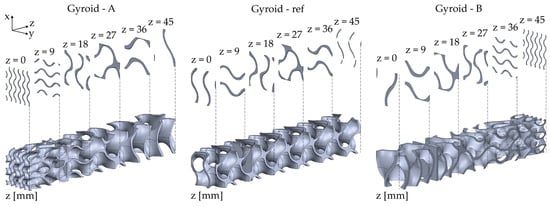

Geometric modifications were then applied to this base shape to introduce a gradual change in local porosity along the z-axis. The reference structure (Gyroid-ref) was preserved in a uniform state, i.e., with a constant period scaling throughout the entire volume, resulting in cross-sections at different heights that exhibit nearly identical topology and pore size.

The Gyroid-A variant was designed such that, near the wetted interface with the flowing liquid (plane z = 0 mm), the gyroid exhibits the smallest openness and the smallest pores, while toward the upper part of the PCM (plane z = 45 mm) the local scale of the structure gradually increases, resulting in larger pores and a less dense metallic skeleton. The Gyroid-B variant represents the opposite gradation: the lower region at the fluid interface is the least compact and contains larger pores, whereas in the upper PCM region the pores become smaller and the structure more compact. In practice, the gradation was achieved by modifying the gyroid surface parameter along the height so that the x–y cross-sections at discrete z-values change systematically while maintaining the overall external dimensions of 10 × 10 × 45 mm.

The principle of these modifications is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows detailed cross-sections of all three structures at regular intervals along the z-axis. For each variant, cross-sections are presented at z = 0, 9, 18, 27, 36, and 45 mm, accompanied by a corresponding three-dimensional visualization of the complete structure. This geometric model makes it possible to investigate the effect of porosity gradation while preserving the same outer shape and overall dimensions of the gyroid. The geometric parameters, including specific surface area, volume, and related quantities, are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional views and 3D visualization of the three gyroid variants (Gyroid-A, reference gyroid, Gyroid-B) at discrete heights along the z-axis.

Table 1.

Geometrical characteristics of the three gyroid variants, including pore diameter (Dp), volume and surface area in the channel and PCM regions.

All three variants have identical height and footprint dimensions and are integrated into the PCM block with same dimensions, with the only differences arising from the distribution of metallic material and the variation in pore size along the z-axis. This ensures that differences in thermo-hydraulic behavior can be attributed solely to geometric effects rather than to variations in PCM layer thickness or contact area at the channel interface.

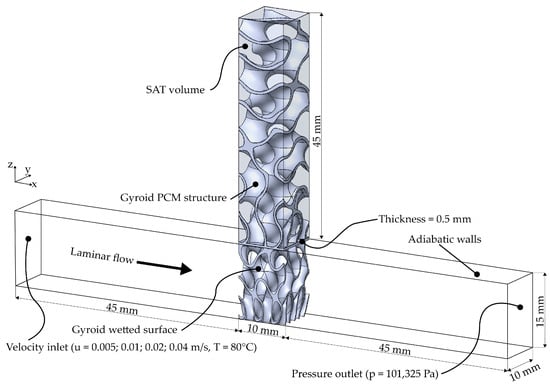

The geometry of the computational model consisted of two interconnected domains: a horizontally oriented channel with flowing liquid and a vertical storage module filled with PCM and the metallic gyroid structure. The layout of the model, including the main dimensions, boundary conditions, and spatial orientation of the coordinate axes, is shown in Figure 3. This configuration was designed to allow accurate analysis of heat transfer from the flowing fluid into the metallic structure and subsequently into the sodium acetate trihydrate, with the gyroid functioning as a thermally conductive bridge transporting energy into the PCM volume.

Figure 3.

Geometry of the computational domain including the flow channel, gyroid structure, and PCM block with boundary conditions.

The horizontal channel had a total length of 90 mm, with a 10 mm central section in contact with the gyroid structure, serving as the wetted surface for heat exchange. The remaining portions of the channel—45 mm at the inlet and 45 mm at the outlet—provided flow development and minimized end effects. The channel cross-section measured 15 × 10 mm, and all side walls were modeled as adiabatic. A velocity inlet boundary condition was applied on the left side of the channel, where the flow velocity was set to 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, or 0.04 m·s−1 at a fluid temperature of 80 °C. A pressure outlet of 101,325 Pa was specified on the right side. The flow in the channel was assumed to be laminar, which was confirmed by Reynolds number values calculated for each geometric variant.

The selected velocity range (0.005–0.04 m·s−1) reflects the operating conditions of compact PCM-based thermal storage units, where laminar flow is preferred to reduce pumping power and ensure sufficient thermal contact time. This does not imply that the concept is limited to low flow rates. Owing to the smooth curvature of the gyroid TPMS structure, higher velocities can be accommodated without requiring an increase in the cross-sectional area, as pressure losses scale predictably and without abrupt flow separation. If applied in industrial systems with larger volumetric flow rates, the device can therefore operate at higher inlet velocities or be scaled geometrically using standard engineering approaches without altering the underlying thermal behavior of the PCM.

A PCM module with a height of 45 mm was placed directly above the central section of the channel. This volume was filled with SAT, which was modeled in the simulation as a homogeneous solid phase including the temperature dependence of density, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity according to [11,29]. Throughout the entire evaluated process, the PCM temperature remained below 58 °C, i.e., below the melting point of SAT, meaning that the PCM operated in the sensible-heat regime. In all directions, the PCM was in perfect thermal contact with the gyroid structure, while the top and lateral surfaces of the PCM were thermally insulated.

The gyroid structure was integrated as a solid body with plan dimensions of 10 × 10 mm and a height of 45 mm, with its bottom surface forming the wetted interface with the flowing liquid in the channel. The metallic skeleton was modeled as a structurally continuous TPMS gyroid positioned precisely along the axis of the PCM module. The material of the gyroid structure was chosen as the aluminum alloy Al 6061, which is a typical choice for additive manufacturing and provides high thermal conductivity, low density, and good mechanical stability. The thermal conductivity of the alloy was taken as 167 W·m−1·K−1, the density as 2700 kg·m−3, and the specific heat capacity as 896 J·kg−1·K−1 [30], making it an effective thermal conductor capable of transferring heat from the liquid into the PCM volume. The working fluid used in the channel was water.

2.2. Numerical Simulation

The overall configuration of the computational model ensured stable and controlled conditions for comparing the different variants of the gyroid structure. The gyroid was in contact with the fluid only at its bottom part, which enabled analysis of the structure’s ability to conduct heat upward and subsequently deliver it into the PCM. The SAT was thermally insulated from the surroundings, eliminating boundary heat fluxes and ensuring that all transferred heat originated solely from the wetted surface of the gyroid. This methodology enabled accurate evaluation of the influence of local variations in gyroid porosity on the PCM temperature field and on the overall heat-transfer effectiveness.

The numerical simulation was performed using SolidWorks Flow Simulation 2024, which solves fluid flow and heat transfer based on the finite-volume method on a Cartesian computational mesh. The physical model [31] is based on the system of continuity, momentum, and energy equations for incompressible flow. The continuity equation ensures the conservation of mass in the form:

where is the velocity vector. The motion of the fluid is described by the Navier–Stokes equation in the form:

where ρ is the density, p is the pressure, μ is the dynamic viscosity, and represents possible body forces (neglected in this model). Heat transfer in both the fluid and solid regions is described by the energy equation:

where cp is the specific heat capacity, k the thermal conductivity, and possible volumetric heat source. In the PCM and in the metallic structure, the term is equal to zero because these are stationary solid phases, and heat transfer is therefore governed purely by conduction. The simulation thus represents a fully coupled conjugate heat-transfer problem in which the energy equations are solved simultaneously in the fluid, the gyroid structure, and the PCM, with continuous temperatures and heat fluxes enforced at their interfaces.

Due to the small dimensions of the channel and the low flow velocities, the Reynolds number remained well within the laminar regime for all simulated cases. For this reason, a laminar-flow model was employed, which simplifies the solution procedure while accurately reflecting the physical conditions. The solution was carried out in transient mode; the simulation began from a steady initial state with the PCM at an initial temperature of 20 °C and terminated once the minimum temperature within the PCM first reached 58 °C. This moment corresponds to the temperature threshold immediately preceding the onset of phase change in SAT and was used as the natural end point of the charging phase. Temperature fields, heat fluxes, and pressure losses were evaluated at defined time steps, with the time-step size chosen to ensure numerical stability and sufficient temporal resolution of the PCM temperature evolution.

The conversion of the geometric model into the computational mesh employs a Cartesian coordinate system in which individual elements are defined as rectangular control volumes, and the complex shapes of solid bodies are represented using so-called partial cells. In these cells, the exact boundaries of the geometry are captured through porosity and effective surface-area parameters. This approach enables mesh generation even for highly complex gyroid structures without the need to generate a body-fitted mesh on the metallic skeleton itself. The mesh density is controlled by global settings and local refinement zones; in this model, refinement was applied primarily around the gyroid walls, within the channel, and at the metal–PCM interface to capture steep temperature and velocity gradients.

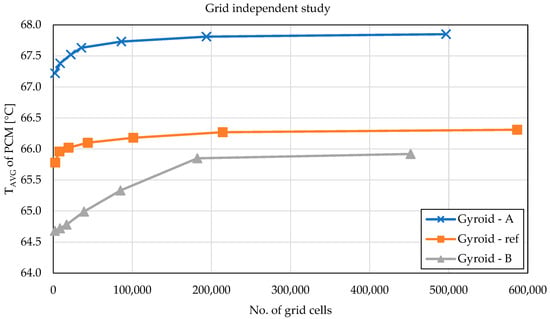

The reliability of the numerical solution was verified through a grid-independence study. For all three gyroid variants (A, reference, and B), several simulations were carried out with progressively refined meshes; the evaluated metric was the average PCM temperature at a defined charging time. The graph in Figure 4 shows the dependence of the average PCM temperature on the total number of mesh cells. It is evident that at low cell counts the solution still changes noticeably with mesh refinement; however, after exceeding approximately 1–2 × 105 cells, the curves for all three geometries flatten significantly. The difference between the penultimate and the finest mesh was less than about 0.2 °C in the average PCM temperature, corresponding to a relative deviation below one percent. Based on these results, a medium refinement level was selected, providing sufficient accuracy at a reasonable computational cost. The grid-independence study thus confirmed that the chosen mesh is adequate for the problem, and that further refinement would lead only to negligible changes in the results while substantially increasing computational time.

Figure 4.

Grid independence study showing the average PCM temperature as a function of the number of computational cells for all three gyroid variants.

Due to the geometric complexity of the gyroid TPMS structure and the use of an immersed-body meshing approach, a visual mesh representation would not provide a clear or informative depiction of mesh quality. For this reason, mesh adequacy is demonstrated through the grid independence study shown in Figure 4, which captures the convergence behavior of the solution and represents a more transparent and quantitative indicator of discretization reliability than a visual mesh snapshot.

Although the study is based on numerical modelling, an assessment of numerical uncertainties was performed to ensure robustness of the obtained results. Three sources of uncertainty were considered:

- Discretization uncertainty—A grid independence study was carried out using three mesh densities. The variation in key output parameters (minimum PCM temperature and pressure drop) between the two finest grids remained below 0.1%, indicating that discretization effects do not influence the comparative conclusions.

- Convergence uncertainty—Each simulation was run until residuals dropped by at least three orders of magnitude and all monitored variables (outlet temperature, heat flux, pressure drop) reached a steady evolution pattern. No oscillatory behavior or divergence was observed, confirming stable numerical convergence.

- Model-form uncertainty—To minimize modelling uncertainty, identical physical models, material properties, turbulence settings (laminar regime), and boundary conditions were applied to all geometries. The comparative nature of the study ensures that any systematic model bias affects all variants equally, allowing meaningful relative evaluation.

These procedures collectively ensure that the observed differences between gyroid configurations arise from physical behavior encoded in the model rather than numerical artefacts.

2.3. Evaluated Hydrodynamic and Thermo-Technical Parameters

Within numerical simulations, several parameters were evaluated to characterize both the hydrodynamic behavior of the flowing medium in contact with the gyroid structure and the intensity of heat transfer from the fluid to the PCM, as well as the internal thermal behavior of the PCM during the charging phase. The set of evaluated quantities was selected to capture the influence of geometric gradation of the gyroid structure on the PCM heating dynamics, heat-transfer efficiency, and hydraulic penalty. The following subsections summarize the mathematical definitions of each parameter and the justification for their inclusion in the analysis.

A key dynamic parameter of the simulation was the time required for the PCM to reach 58 °C, denoted as t58. This moment corresponds to the point at which the minimum temperature within the PCM first reaches 58 °C; i.e., this temperature represents the interface between the solid and liquid phases. In addition to t58, the maximum PCM temperature at this moment was also monitored, providing information about thermal non-uniformity and the degree of stratification present in the PCM when the threshold temperature is reached. The hydrodynamic behavior of the flowing liquid was characterized using the Reynolds number (Equation (5)) [32,33].

where ρ is the fluid density, u the flow velocity, Dp the hydraulic diameter of the gyroid pore, and μ the dynamic viscosity. In Equation (5), the velocity term represents the local instantaneous flow velocity obtained directly from the CFD solution. The inlet boundary condition was specified using the prescribed inlet velocity (four operating velocities used in the study), and the complete velocity field is calculated by solving the Navier–Stokes equations at each time step. The convective term in the equation therefore uses the actual cell-wise velocity values arising from the momentum solution. The hydraulic diameter of the gyroid structure was evaluated using the porosity–surface-area relation commonly applied to porous and TPMS geometries:

where ε denotes the porosity (void fraction) of the gyroid and SS represents its specific internal surface area per unit volume. Both parameters were obtained from the CAD-based geometric analysis. This definition provides a representative characteristic length for momentum transport in structures composed of interconnected pores and enables consistent evaluation of the Reynolds number and hydraulic behavior across all investigated variants. The Darcy friction factor was calculated using (Equation (7)) [34]:

where Δp represents the pressure drop over the length L, u is the mean flow velocity, ρ is the density of water, and Dp is the hydraulic diameter of the TPMS pore. This parameter makes it possible to identify the influence of geometric variation of the gyroid on flow resistance. By comparing the relationship f = f(Re) between the individual geometries, it is possible to assess what portion of the hydraulic penalty is caused by changes in porosity at the base of the gyroid. The intensity of heat transfer from the liquid to the metallic structure was evaluated using the Nusselt number [35]:

where h is the average heat transfer coefficient determined from the relation:

where q″ is the integral heat flux on the wetted surface of the gyroid, Tbulk is the fluid temperature, and Tsurf is the temperature of the metallic surface. The Nusselt number enables comparison of heat transfer at the wetted surface for different velocities and geometries independently of the physical properties of the fluid. Given the geometrically complex shape of the gyroid, the local pressure-loss coefficient was also evaluated according to Equation (9):

which expresses the overall flow resistance of the gyroid structure normalized by the dynamic pressure. The parameter ξ is essential when comparing different geometric variants, as it makes it possible to separate the effect of the gyroid design from the effect of flow velocity.

The Colburn j-factor represents a combined heat-transfer and flow-performance criterion. The value of the j-factor makes it possible to assess the extent to which heat transfer enhancement is caused by geometric modification, while providing a comparable quantity across different flow velocities. The Colburn j-factor [36] was defined as:

where Pr is the Prandtl number, evaluated separately as it represents a key dimensionless parameter linking momentum and heat transport in the fluid. It was calculated from the relation:

where μ is the dynamic viscosity of water, cp its specific heat capacity, and kf the thermal conductivity of the fluid at the film temperature. The film temperature was defined as the arithmetic mean of the bulk temperature of the flowing water and the temperature of the wetted surface of the gyroid. The Prandtl number enters both the definition of the Colburn j-factor and the comparison with correlations from the literature, which are often expressed in the form Nu = f(Re, Pr). Since the Prandtl number of water remains within a relatively narrow interval in the considered temperature range, its explicit determination ensures consistency in evaluating the Nusselt number and in interpreting the heat-transfer characteristics of the individual geometric variants.

The thermo-hydraulic performance of the gyroid structure was assessed using the Performance Evaluation Criteria—PECNu–f [37], defined by the relation:

where “ref” denotes the values obtained for the uniform gyroid. This criterion makes it possible to determine whether the enhancement of heat transfer in the graded geometries was achieved without incurring an excessive increase in pressure losses. The second performance criterion combined the PCM charging time with the normalized pressure loss, and its formulation was constructed following the approach in [38]:

This parameter reflects the practical applicability of the geometry under dynamic charging conditions. Higher values indicate faster PCM heating at an acceptable hydraulic penalty. The temperature non-uniformity within the PCM was expressed as the difference:

Lower values of ΔT indicate a more uniform distribution of heat within the PCM, which is desirable in thermal storage systems because it reduces the risk of underutilizing parts of the PCM volume. To allow comparison across different temperature levels, a dimensionless homogeneity index was introduced:

where Tavg is the average PCM temperature at the evaluated moment. This index provides an objective measure for comparing the ability of different geometries to homogenize the temperature field. Energetic efficiency was also evaluated using the parameter R:

where is the instantaneous heat flux transferred from the metallic gyroid into the PCM. The parameter R provides a simple yet physically meaningful measure of how much thermal energy the system can transfer per unit of pressure loss. In practice, it expresses the trade-off between thermal benefit and hydraulic penalty.

Finally, a visual analysis of the temporal evolution of the isothermal surface T = 58 °C in the PCM was also performed. This isosurface represents the leading edge of the thermal front, and its position at defined time intervals makes it possible to directly observe how rapidly each geometry distributes heat into the PCM volume. This method complements the numerical parameters and provides an intuitive representation of the practical effectiveness of pore gradation.

3. Results

This section presents the results of numerical simulations and discusses the influence of the three gyroid structure variants on hydraulic behavior, heat transfer, and the PCM heating dynamics. The individual subsections follow the evaluated parameters described in the methodology.

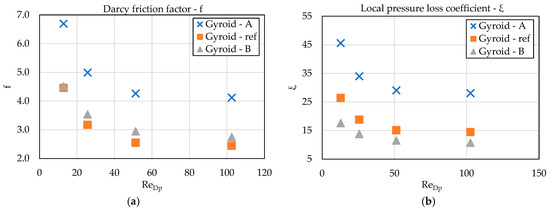

The hydraulic conditions in the channel were assessed using the Darcy friction factor and the local pressure-loss coefficient. As shown in the Darcy friction factor graph in Figure 5a, Gyroid-A exhibits the highest flow resistance at all simulated velocities, which is a consequence of the dense metallic skeleton with the smallest pores located at the base of the structure.

Figure 5.

(a) Darcy friction factor versus Reynolds number for the three gyroid variants; (b) Local pressure loss coefficient ξ versus Reynolds number.

In this region, the most pronounced narrowing of the flow channels occurs, which leads to increased shear stresses and a higher-pressure gradient. In contrast, Gyroid-B exhibits the lowest friction-factor values because its largest pores are located directly at the fluid interface, allowing smoother flow with reduced obstruction. The reference gyroid shows intermediate values, which is expected given its homogeneous periodic structure. The same trend is observed for the local pressure-loss coefficient ξ at Figure 5b, where Gyroid-A again represents the variant with the highest losses and Gyroid-B the one with the lowest.

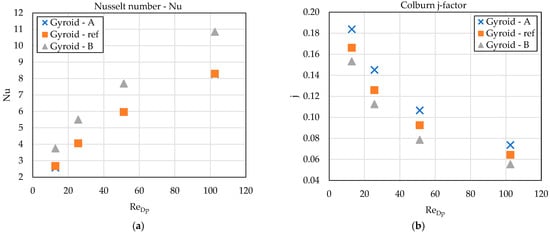

Heat transfer at the wetted surface of the gyroid was evaluated using the dependence of the Nusselt number on the Reynolds number, as shown in Figure 6a. The results indicate that Gyroid-B achieves the highest heat-transfer intensity, whereas Gyroid-A exhibits the lowest Nusselt numbers. The elevated Nu values for geometry B arise from a combined dual effect: the large pores at the base ensure effective flushing of the metallic structure by the flowing water, while the structure becomes denser in the direction of the PCM, forming an efficient three-dimensional thermal conductor that transfers heat from the metallic skeleton into the PCM volume. The reference gyroid lies consistently between the two graded variants, reflecting balanced but non-optimized heat transfer. Although the Colburn j-factor shown in Figure 6b exhibits higher values for geometry A, the j-factor does not account for pressure losses. Therefore, the dimensionless Performance evaluation criterion (PEC) criteria presented in Figure 7a,b provide a more relevant measure for evaluating the overall thermal–hydraulic efficiency.

Figure 6.

(a) Nusselt number versus Reynolds number; (b) Colburn j-factor versus Reynolds number for the three gyroid geometries.

Figure 7.

(a) Performance evaluation criterion PECNu–f; (b) Dynamic performance criterion PECt–ξ as a function of Reynolds number.

The overall thermo-hydraulic effectiveness of the individual geometries is captured by two PEC criteria. The first, PECNu–f, which compares the increase in heat transfer with the increase in hydraulic resistance, shows that Gyroid-B reaches values significantly above 1 across the entire Reynolds-number range. This indicates that its enhanced heat-transfer performance is achieved without a disproportionate rise in pressure drop. The Gyroid-A yields value below 1, confirming that the heat-transfer enhancement in variant A is insufficient to compensate for its high losses.

The second criterion, PECt–ξ, evaluates the PCM heating dynamics while accounting for hydraulic penalization. Here as well, Gyroid-B performs most favorably, whereas Gyroid-A represents the weakest configuration, in comparison with the reference geometry.

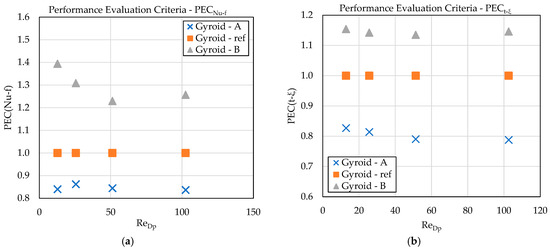

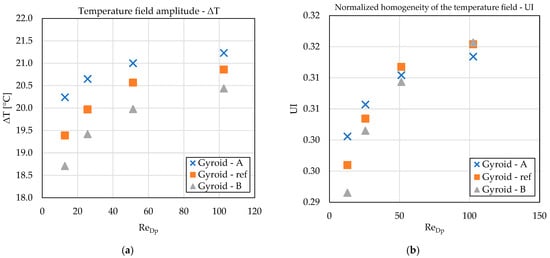

The homogeneity of the temperature field within the PCM is a key criterion for practical use. The temperature-amplitude ΔT shown in Figure 8a demonstrates that Gyroid-B provides the most uniform temperature distribution in the PCM, exhibiting the lowest ΔT values across all flow velocities. Geometry A, conversely, shows the highest temperature gradients, resulting from concentrated heat conduction in the dense lower part of the structure. The normalized homogeneity index UI depicted in Figure 8b, confirms this outcome: Gyroid-B achieves the lowest UI values, and thus the best homogenization, while Gyroid-A exhibits the poorest.

Figure 8.

(a) Temperature amplitude ΔT in PCM at t58; (b) Normalized temperature uniformity index UI at t58 for each gyroid variant.

This distinction is critical for assessing the usable PCM volume, since temperature homogeneity determines how large a portion of the PCM effectively participates in heat storage during the charging cycle.

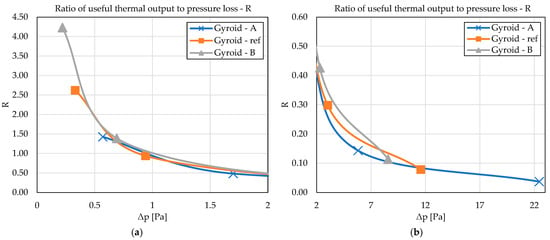

The energetic efficiency of the system was evaluated using the parameter R, defined as the ratio of the useful thermal power delivered to the PCM to the corresponding pressure loss. The parameter R represents a pragmatic evaluation criterion that captures how much thermal energy is transferred into the PCM “per unit of hydraulic cost,” and is therefore well suited for assessing real thermal-storage systems in which pressure loss directly influences the electrical consumption of the circulation pump.

The graph in Figure 9a shows that the parameter R is strongly nonlinear and reaches its highest values at the lowest pressure drops, that is, in the region of the lowest flow velocities. At very small values of Δp (around 0.3–0.5 Pa), Gyroid-B exhibits the highest values, reaching R ≈ 4.2, while the reference variant is around 2.6 and Gyroid-A approximately 1.4. This pronounced difference arises from the combination of two factors: Gyroid-B provides a highly useful heat flux while maintaining very low hydraulic resistance, whereas Gyroid-A, although transferring more heat than the reference variant, experiences such large pressure losses that its resulting R parameter remains low.

Figure 9.

Energetic efficiency parameter as a function of pressure drop for all gyroid geometries, (a) visualization for the region with pressure loss up to 2 Pa, (b) visualization for the region with pressure loss from 2 to 23 Pa.

As the pressure drop increases, the R value decreases rapidly for all geometries; however, the trend remains consistent: Gyroid-B achieves the highest R values across the entire Δp range, while Gyroid-A shows the lowest. The reference gyroid consistently falls between the two. At higher pressures, where Δp exceeds 5–10 Pa, the R values of all geometries begin to converge toward low values close to zero, reflecting the fact that although increasing the flow velocity enhances heat flux, the hydraulic losses rise much more rapidly and outweigh the heat-transfer benefit.

The most significant finding is that Gyroid-B provides the most advantageous compromise from the perspective of energetic efficiency. Its high R values at low pressure drops are particularly relevant for solar thermal systems, waste-heat recovery units, and low-temperature thermal storage, where operation commonly occurs at low flow velocities and where minimization of pump electrical consumption is highly desirable. In contrast, Gyroid-A is the least energy-efficient configuration because its high-pressure losses significantly reduce its thermal benefit relative to its hydraulic penalty.

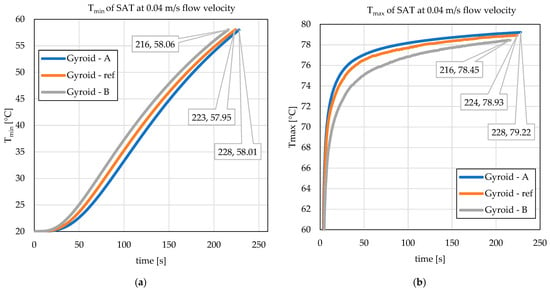

The thermal response of the PCM was analyzed using the time evolution of the minimum and maximum temperatures within the SAT volume. These data make it possible to evaluate both the rate at which heat penetrates the coldest regions of the PCM and the level of thermal non-uniformity just before phase transition.

As shown in the table and in the Tmin graph for a flow velocity of 0.04 m/s in Figure 10a, Gyroid-B reaches the threshold temperature of 58 °C first, specifically at approximately 216 s. The reference gyroid reaches the same threshold slightly later (224 s), while Gyroid-A is the slowest (228 s). This trend is observed at all flow rates in Table 2, indicating that the gradation orientation with the largest pores at the base (variant B) leads to faster heat transfer into the coldest regions of the PCM and thus to faster overall heating of the volume to the melting threshold. The Tmax graph for a flow velocity of 0.04 m/s in Figure 10b provides a complementary perspective: Gyroid-A exhibits the highest values of maximum PCM temperature throughout the entire heating process, indicating concentrated heat conduction through the dense lower part of the structure, but also greater non-uniformity. The reference gyroid exhibits slightly lower Tmax values, while Gyroid-B shows the lowest Tmax at time t58. Specifically, at 0.04 m/s, Tmax(t58) is 79.23 °C for A, 78.93 °C for the reference, and only 78.47 °C for B.

Figure 10.

Time course of minimum (a) and maximum (b) PCM temperature for case with flow velocity 0.04 m/s.

Table 2.

Thermal response of PCM at t58 for all gyroid variants, including charging time, maximum temperature and average temperature at different flow velocities.

This difference becomes even more pronounced when comparing the average PCM temperature at time t58. Gyroid-A reaches the highest average temperature (67.74 °C), the reference gyroid an intermediate value (66.14 °C), while Gyroid-B shows the lowest average temperature (64.75 °C). A lower average PCM temperature in geometry B indicates that heat is distributed more smoothly within the PCM and penetrates deeper without forming localized hot regions.

These results suggest two important insights. First, Gyroid-B exhibits the fastest rate of heat penetration into the PCM, which is consistent with its shortest t58. Second, Gyroid-B simultaneously minimizes local overheating and ensures the most uniform temperature profile, which is essential for the long-term cyclic stability of PCM. Although Gyroid-A reaches higher Tmax and Tavg values, this rapid heating is locally concentrated and leads to steep temperature gradients that may become problematic over extended operating cycles.

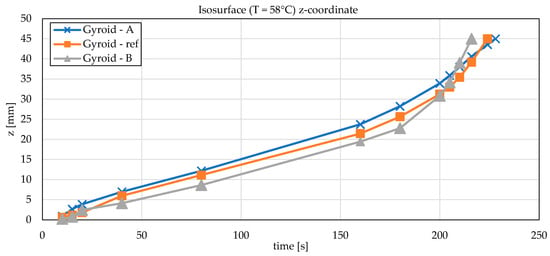

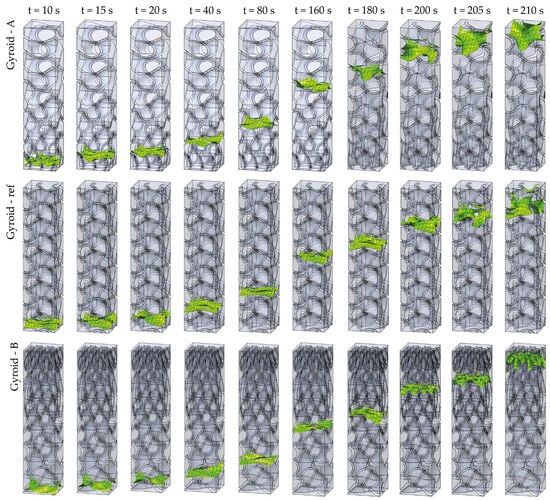

The propagation of the thermal front within the PCM was analyzed using two complementary approaches: tracking the z-coordinate of the isotherm T = 58 °C over time and spatial visualization of the isothermal surface at selected time points. Both methods provide valuable insight into how quickly and in what manner heat is distributed throughout the PCM volume, and thus how effectively the metallic structure transfers energy from the wetted surface to the upper regions of the storage module.

The time evolution of the z-coordinate of the isotherm, shown in Figure 11, reveals that during the early stages of heating (t < 100 s) all three geometries behave rather similarly, and the thermal front advances upward at nearly the same rate. The differences begin to intensify only during the later stage of the heating process. The fastest upward movement of the isotherm toward the top of the PCM is observed for Gyroid-A, which is linked to concentrated heat conduction through the dense lower portion of its structure. The reference gyroid exhibits a slightly slower progression. Interestingly, Gyroid-B behaves differently: in the initial stages it shows the slowest advance of the isotherm, but its curve rises more steeply later, and at several time points it catches up with or slightly surpasses the reference geometry. This behavior suggests that although Gyroid-B is highly open in its lower region—resulting in a more spatially distributed heat-transfer zone on the wetted surface, its progressively densifying upper region enables efficient upward redistribution of heat once the PCM becomes more uniformly warmed.

Figure 11.

Temporal evolution of the z-coordinate of the 58 °C isotherm in PCM for the three gyroid geometries.

A noticeable difference between the two graded configurations appears in the final interval of the charging process, where Gyroid B exhibits a relatively steep increase in the monitored temperature. This effect results from the remaining cold SAT region becoming very small, allowing its rapid thermal collapse once the adjacent gyroid ligaments are fully heated. The observed behavior is therefore a consequence of the vertical pore gradation: Gyroid B features large pores near the heat-transfer-medium interface, which lowers the local thermal resistance and accelerates heat penetration into the PCM during the early and mid-stages of charging. As a result, the final residual low-temperature zone disappears more abruptly, producing the steep slope in the temperature curve. When comparing all performance indicators—total time to reach 58 °C, temperature homogenization, and average heating rate—Gyroid B demonstrates superior performance to Gyroid A, despite the sharper end-stage behavior.

The spatial visualization of the isothermal surface in Figure 12 provides a complementary and far more detailed picture. For Gyroid-A, the T = 58 °C surface spreads very unevenly from the beginning. Distinct local maxima emerge in confined areas, following the axes of the most massive metallic connections. The isosurface is highly fragmented and occupies a narrow horizontal region in the early phase, leading to low temperature homogeneity and a high temperature amplitude.

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional visualization of the T = 58 °C isosurface propagation in PCM for Gyroid-A, reference gyroid and Gyroid-B at selected time steps.

For the reference gyroid, the isothermal surface is more compact and exhibits a more regular shape. The advance of the thermal front is smoother and less sensitive to local variations caused by differences in the density of the metallic structure. The most uniform progression and the most homogeneous shape of the isotherm are observed for Gyroid-B. In the early stages, the isothermal surface is the lowest among the three geometries, yet it has the widest and most regular shape. As time proceeds, the isosurface moves upward smoothly while maintaining high compactness and reasonable symmetry. This behavior closely corresponds to the results of the temperature amplitude ΔT and the homogeneity index UI, for which Gyroid-B achieves the best values. The densifying upper region of this geometry acts as a three-dimensional thermal distributor that smooths temperature differences within the PCM and enables heat to propagate more uniformly and less channel-like than in geometry A.

These observations show that the shape of the isotherm within the PCM is determined not only by the intensity of heat transfer at the wetted surface, but, more importantly, by how the metallic structure is distributed in space and how it conducts heat into the PCM volume. Gyroid-A naturally leads to rapid heat penetration, but it does so in a highly concentrated manner, generating pronounced local gradients. In contrast, Gyroid-B produces the most uniform thermal front because its geometric gradation ensures smoother heat conduction throughout the entire volume.

As shown in Figure 12, the cold region within PCM shrinks progressively over the course of the charging process. The disappearance of this region reflects the increasing portion of the SAT volume that reaches the target temperature of 58 °C. Combined with the evolution of the minimum temperature, which identifies the moment when the entire domain exceeds this threshold—the presented results provide a comprehensive description of both the temporal and spatial progression of the heating process.

Taken together, these results confirm that the quality and shape of the thermal front in the PCM is just as important an indicator as the t58 time itself. Fast but non-uniform heat propagation can lead to long-term degradation of the PCM and inefficient utilization of its volume, whereas uniform heat distribution, as provided by the B-type gradation, ensures more stable operation and better use of the storage material.

The study demonstrates that vertical gradation of a gyroid TPMS structure can significantly enhance the thermal performance of SAT-based latent heat-storage units. The configuration with large pores near the HTF interface and progressive densification toward the PCM accelerated the heating of the entire SAT volume to 58 °C by 3.6% compared to the homogeneous reference gyroid and by 5.3% compared to the oppositely graded variant. Moreover, this geometry achieved the lowest temperature amplitude (by 18–25%) and the most favorable uniformity index across all tested Reynolds numbers, confirming improved thermal homogenization. In terms of thermo-hydraulic behavior, the graded gyroid reached a peak energetic efficiency indicator R of 4.2, representing a 62% improvement over the reference structure and a 200% improvement over the opposite gradation. These quantitative findings confirm that vertically graded gyroid structures provide a measurable and robust enhancement of conductive heat transfer in low-conductivity PCM composites.

Although the present work is based on numerical modelling, several validation-oriented steps were included to ensure robustness of the findings. The grid-independence analysis confirmed that further mesh refinement changed the minimum PCM temperature and pressure-drop values by less than 0.1%, indicating negligible discretization uncertainty. Convergence stability was verified through residual monitoring and the steady evolution of integral quantities such as outlet temperature and pressure drop.

To provide a clearer comparison of the evaluated geometries, quantitative indicators were added to the Section 3. The graded gyroid (Gyroid B) reduced the time required for the entire PCM volume to reach 58 °C by 3.6% compared to the homogeneous reference and by 5.3% relative to the opposite gradation. Improvements in temperature-field uniformity ranged from 18–25%, while the energetic indicator R increased by 62% compared to the reference structure. These measurable results demonstrate that the orientation of pore gradation significantly affects the conductive heating of SAT.

The general trends observed in this study—faster heat penetration and reduced thermal stratification due to the presence of a conductive 3D scaffold—align with experimentally validated findings reported for PCM–metal-foam composites in previous literature. While numerical values cannot be directly compared across different materials and geometries, this consistency provides additional support for the physical validity of the results.

4. Discussion

The results of the numerical simulation clearly confirm that the geometric gradation of the gyroid structure has a significant impact on both the thermal and hydraulic behavior of the PCM composite. Although all three variants contain the same volume of metal, have the same heat-transfer path length, and offer comparable wetted surface area, the differences in their topology lead to pronounced changes in heating dynamics, in the shape of the propagating isotherm, and in the overall energetic performance of the system. This demonstrates that neither the mass nor the surface area of the metal alone determines the thermal response of a PCM composite. The decisive parameter is the topology—namely the direction and character of the spatial distribution of the metallic skeleton.

The most prominent influence of gradation becomes evident when evaluating the t58 time, defined as the time required to heat the PCM to 58 °C throughout its entire volume. Among all variants, Gyroid-B achieves the shortest t58, and this trend is consistent across all flow velocities analyzed. The open lower region of the structure enables uniform and hydraulically favourable heat transfer into the metal, while the densifying upper part accelerates the propagation of heat into the PCM volume. The result is rapid yet uniform heating, which is reflected in the temperature fields. Gyroid-A, by contrast, exhibits the longest t58, despite conducting heat very quickly along several dominant thermal pathways. However, this behavior leads to localized hotspots rather than uniform heating of the PCM as a whole.

The same trend is reflected in the maximum and average PCM temperatures at t58. Gyroid-B reaches the lowest values of Tmax and Tavg, indicating that heat is distributed uniformly and without significant local gradients. From the perspective of long-term PCM stability, this is a crucial advantage: reducing temperature extremes and homogenizing the temperature field limit internal stresses within the PCM, thereby extending its operational lifetime. Gyroid-A, in contrast, produces the highest Tmax and Tavg values, confirming a less favourable heat distribution and a strong tendency toward local thermal peaks.

Analysis of the propagation of the T = 58 °C isotherm provides further insight into the differences between the geometric variants. In Gyroid-A, the isosurface advances in the form of narrow thermal channels aligned with the thickest metallic connections. This channel-like behavior explains the rapid local heating but also the pronounced temperature non-uniformity. The reference gyroid yields a more stable but still not fully uniform thermal front. Gyroid-B, however, produces the most compact and uniform isothermal surface, which progresses upward smoothly and without noticeable asymmetries or local protrusions. This observation is consistent with the lowest temperature amplitude ΔT and the highest homogeneity index UI among all variants, confirming the synergistic effect of its gradation.

This result carries essential implications for practical applications. In latent-heat storage systems—especially in solar thermal installations and waste-heat recovery units—operation often occurs at very low flow rates and pressure drops. Under such conditions, the B-type geometry can substantially reduce the electrical power consumption of circulation pumps, thereby improving overall operational efficiency. At the same time, a more uniform temperature field slows PCM degradation, extending the lifetime of the storage system and reducing maintenance or replacement requirements.

From the perspective of long-term development of PCM storage technologies, the results indicate that topological optimization of metallic structures may be as effective, or even more effective, than chemical modification of PCM or increasing the volume of metallic filler. The B-type gradation combines the advantages of low hydraulic resistance and high effective thermal conductivity without the negative side effects associated with nano-additives or micro-fillers. In the context of rapidly advancing metal additive manufacturing, which provides precise control over TPMS topology, these findings suggest that the future of PCM composites will likely be shaped by geometric rather than material optimization.

The observed acceleration of heat penetration and reduction in thermal stratification agree with trends reported in earlier studies employing metallic foams or homogeneous porous inserts [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These works consistently demonstrate that introducing a three-dimensional conductive network into PCM enhances effective thermal conductivity and shortens the charging period. The present results follow the same qualitative behavior; however, the proposed vertically graded gyroid extends this concept by modifying the local pore size along the heat-flow direction. To the authors’ knowledge, such directional tailoring of a TPMS structure has not been examined in previous PCM studies, and the observed differences between the graded variants highlight the additional degree of control that can be achieved compared to conventional, uniformly porous structures.

Compared to traditional PCM enhancement methods such as heat pipes or finned structures, which provide predominantly one-dimensional conductive pathways, the gyroid TPMS structure operates as a spatially continuous three-dimensional conductive network. This geometric characteristic enables heat to be distributed simultaneously in all directions, thereby reducing thermal stratification and improving temperature-field homogeneity in the solid PCM. While heat pipes can offer very high effective conductivity along their axial direction, their performance depends on working-fluid selection and orientation, and they do not provide volumetric heat distribution within the PCM. The gyroid structure therefore represents a qualitatively different enhancement approach, offering isotropic conductive pathways and enabling directional optimization through pore-size gradation, as demonstrated in this study.

Overall, among the tested variants, Gyroid-B provides the most balanced combination of heat transfer, hydraulic resistance, temperature homogeneity, and energetic efficiency. Its physical behavior confirms that an appropriately chosen direction of gradation can fundamentally improve the performance of PCM storage systems without increasing material costs or modifying the PCM itself. This conclusion has broad relevance for the design of modern thermal-storage technologies and aligns well with current trends in energy efficiency and sustainability.

5. Conclusions

The results of this work demonstrate that a vertically graded gyroid structure can significantly influence heat transfer, charging rate, and thermal homogeneity in latent heat-storage systems using sodium acetate trihydrate. The comparison of the three geometric variants shows that the direction of gradation is the decisive parameter. The configuration featuring large pores at the fluid interface and progressive densification toward the PCM (Gyroid B) achieved the best overall performance. At a flow velocity of 0.04 m/s, the entire PCM volume in this configuration was heated to 58 °C within 216 s, which represents an improvement of 3.6% compared to the homogeneous reference gyroid (224 s) and 5.3% compared to the oppositely graded geometry A (228 s). In addition, this variant reached the lowest maximum PCM temperature (78.47 °C) and the lowest average temperature (64.75 °C) at the moment of full heating, confirming the highest degree of thermal homogeneity. Both the temperature amplitude and the uniformity index UI remained consistently lowest for this geometry across the entire Reynolds-number range.

In terms of thermo-hydraulic efficiency, the same gradation achieved the highest values of PECNu−f and PECt−ξ, confirming that the improvement in heat transfer is not offset by hydraulic penalization. The energetic indicator R reached a peak value of approximately 4.2, which corresponds to a 62% improvement over the reference structure (2.6) and almost a 200% improvement compared to the opposite gradation (1.4). These results demonstrate that the large-to-small pore arrangement provides the most favorable compromise between heat-transfer performance, temperature-field uniformity, and flow-related energy consumption.

Based on the logical structure of the investigation, the key findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

- The introduction of a gyroid-based thermally conductive scaffold substantially accelerates heat penetration into solid SAT due to the formation of a continuous three-dimensional conductive network, which reduces diffusive thermal resistance and suppresses thermal stratification during charging.

- The direction of vertical gradation strongly affects transport phenomena: locating larger pores near the heat-transfer-fluid interface (Gyroid B) enhances early-stage conduction, accelerates the disappearance of low-temperature regions, and improves thermal homogenization compared with the oppositely oriented gradation.

- Among all tested configurations, the large-to-small pore orientation exhibits the most favorable combination of heat-transfer intensity, temperature-field uniformity, and thermo-hydraulic effectiveness, indicating that controlled gradation of TPMS structures is a highly effective design strategy for low-conductivity PCMs such as sodium acetate trihydrate.

Beyond these core findings, the practical implications are noteworthy. A vertically graded gyroid can be integrated into compact PCM modules used in low-temperature solar thermal systems, heat-pump buffers, and industrial waste-heat recovery units. Its ability to shorten charging time, improve temperature distribution, and maintain low pressure losses offers tangible benefits for applications where conduction-dominated heat transfer limits overall system efficiency. The directional pore architecture also provides a tunable design parameter for customizing thermal performance to specific operating conditions.

The robustness of the conclusions is supported by numerical-uncertainty considerations: the grid-independence study showed that variations between the two finest meshes remained below 0.1%, and convergence stability was confirmed by residual reduction and monotonic temperature evolution. These factors indicate that the observed performance differences stem from physical effects of the gyroid geometry rather than numerical artefacts.

Future work will extend the present study by incorporating a full phase-change model to investigate melting dynamics, buoyancy-driven convection, and mushy-zone behavior in SAT. Experimental validation of vertically graded TPMS structures is also planned to verify their real-world applicability and to establish design guidelines for energy-efficient latent-heat storage units.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and R.R.; methodology, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, R.R.; funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic KEGA: 056TUKE-4/2024 A platform for the effective creation, evaluation, and transfer of innovations, and the efficient management of university research outputs with a practical orientation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AVG | Average |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DMLS | Direct Metal Laser Sintering |

| MAX | Maximum |

| MIN | Minimum |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| SAT | Sodium Acetate Trihydrate |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| TPMS | Triply Periodic Minimal Surface |

| Symbols | |

| Dp | Hydraulic diameter of porous structure [mm] |

| cp | Specific heat capacity [J·kg−1·K−1] |

| f | Darcy friction factor [-] |

| h | Heat transfer coefficient [W·m−2·K−1] |

| j | Colburn j-factor [-] |

| k | Thermal conductivity [W·m−1·K−1] |

| kf | Thermal conductivity of fluid [W·m−1·K−1] |

| L | Length [mm] |

| Nu | Nusselt number [-] |

| p | Pressure [Pa] |

| PEC | Performance Evaluation Criteria [-] |

| Pr | Prandtl number [-] |

| q″ | Integral heat flux on the wetted surface [W·m−2] |

| Volumetric heat source [W] | |

| Heat flux transferred from the metallic gyroid into the PCM [W·m−2] | |

| R | Energetic efficiency indicator [-] |

| Re | Reynolds number [-] |

| SS | Specific surface area [-] |

| t | Time [s] |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| u | Velocity [m·s−1] |

| UI | Homogeneity index [-] |

| x | Coordinate in the x-axis direction [mm] |

| y | Coordinate in the y-axis direction [mm] |

| z | Coordinate in the z-axis direction [mm] |

| ε | Porosity [-] |

| ξ | Local pressure-loss coefficient [-] |

| μ | Dynamic Viscosity [Pa·s] |

| ρ | Density [kg·m−3] |

References

- Farid, M.M.; Khudhair, A.M.; Razack, S.A.K.; Al-Hallaj, S. A review on phase change energy storage: Materials and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 1597–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalba, B.; Marín, J.M.; Cabeza, L.F.; Mehling, H. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change: Materials, heat transfer analysis and applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2003, 23, 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Castell, A.; Barreneche, C.; de Gracia, A.; Fernández, A.I. Materials used as PCM in thermal energy storage in buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1675–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, W.; Kramer, G.J.; Sun, Q. Seasonal thermal energy storage: A techno-economic literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteconi, A.; Hewitt, N.J.; Polonara, F. State of the art of thermal storage for demand-side management. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Energy Storage. Sustainability 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Rosen, M.A. Thermal Energy Storage: Systems and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Tyagi, V.V.; Chen, C.R.; Buddhi, D. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change materials and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, C.V.; Kartsonakis, I.A.; Charitidis, C.A. Towards Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage: Classification, Improvements and Applications in the Building Sector. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Lu, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, G. Towards Passive Building Thermal Regulation: A State-of-the-Art Review on Recent Progress of PCM-Integrated Building Envelopes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenisarin, M.; Mahkamov, K. Salt hydrates as latent heat storage materials: Thermophysical properties and costs. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 145, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Du, H.; Chen, Z.; Lei, S. Review of phase change heat transfer enhancement by metal foam. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremannezhad, A.; Xu, H.; Salimpour, M.R.; Wang, P.; Vafai, K. Thermal performance analysis of phase change materials (PCMs) embedded in gradient porous metal foams. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 179, 115731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccega, E.; Vallese, L.; Bottarelli, M. Enhancement of thermal conductivity of paraffin PCM with metal foams. Int. J. Thermophys. 2025, 46, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Rehman, D.; Dongellini, M.; Naldi, C.; Pulvirenti, B.; Morini, G.L. Experimental Investigation on Latent Thermal Energy Storages (LTESs) Based on Pure and Copper-Foam-Loaded PCMs. Energies 2022, 15, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, A.M.; Wang, S. Effect of metal foam integration on the thermal regulation performance of salt hydrate-based heat sink. In Proceedings of the International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 11–14 July 2022. Paper 2454. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, C.; Dongellini, M.; Morini, G.L. The evaluation of the effective thermal conductivity of metal-foam loaded phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Sun, C.; Liu, R. Thermal Performance of a PCM-Based Thermal Energy Storage with Metal Foam Enhancement. Energies 2019, 12, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wei, G.; Xu, C.; Ju, X.; Yang, Y.; Du, X. Numerical simulation of effective thermal conductivity and pore-scale melting process of PCMs in foam metals. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 147, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.S.H.; Diani, A. Study of Heat Transfer Characteristics of PCMs Melting Inside Aluminum Foams. Materials 2025, 18, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Giacomello, A.; Meloni, S.; Dauvergne, J.-L.; Nikulin, A.; Palomo, E.; Ding, Y.; Faik, A. Hierarchical macro-nanoporous metals for leakage-free high-thermal conductivity shape-stabilized phase change materials. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskery, I.; Sturm, L.; Aremu, A.O.; Panesar, A.; Williams, C.B.; Tuck, C.J.; Wildman, R.D.; Ashcroft, I.A.; Hague, R.J.M. Insights into the mechanical properties of several triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures made by polymer additive manufacturing. Polymer 2018, 152, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Hao, L.; Hussein, A.; Young, P.; Raymont, D. Advanced lightweight 316L stainless steel cellular lattice structures fabricated via selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Carter, W.B. Architected cellular materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskery, I.; Aremu, A.O.; Parry, L.; Wildman, R.D.; Tuck, C.J.; Ashcroft, I.A. Effective design and simulation of surface-based lattice structures featuring volume fraction and cell type grading. Mater. Des. 2018, 155, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M.Y.; Feih, S. Hierarchical sheet triply periodic minimal surface lattices: Design, geometric and mechanical performance. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Mertens, R.; Ferrucci, M.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y.; Yang, S. Continuous graded Gyroid cellular structures fabricated by selective laser melting: Design, manufacturing and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2019, 162, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, A.H. Infinite Periodic Minimal Surfaces without Self-Intersections; NASA Technical Note TN D-5541; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Güémez, J.; Fiolhais, C.; Fiolhais, M. Quantitative experiments on supersaturated solutions for the undergraduate thermodynamics laboratory. Eur. J. Phys. 2005, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASM International. ASM Handbook, Volume 2: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dassault Systèmes. SolidWorks Flow Simulation Technical Reference; Dassault Systèmes: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Padrão, D.; Hancock, D.; Paterson, J.; Schoofs, F.; Tuck, C.; Maskery, I. New structure-performance relationships for surface-based lattice heat sinks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.W.; Fee, C.J.; Morison, K.R.; Holland, D.J. Characterisation of Heat Transfer within 3D Printed TPMS Heat Exchangers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 212, 124264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Zeng, M.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Z. Investigation on flow and heat transfer in various channels based on triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS). Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knödler, P.; Dreissigacker, V. Fluid Dynamic Assessment and Development of Nusselt Correlations for Fischer Koch S Structures. Energies 2024, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, L.A.; Koppius, A.M.; Nieuwvelt, C. An experimental determination of the turbulent prandtl number in the inner boundary layer for air flow over a flat plate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1983, 26, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwary, A.; Miskdjian, I.; Gamea, O.; Abohadima, S. Numerical analysis of heat transfer and turbulent flow friction in a tube equipped with perforated double conical rings. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2025, 72, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.L.; Kim, N.H. Principles of Enhanced Heat Transfer; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).